- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- In Illinois, Democrats face a test of ‘big tent’ values

- For heartland farmers, Trump support gets snagged on trade, tariffs

- Putin won his mandate. Can he deliver on promise of restored glory?

- How treating gun violence as public-health issue could help children

- An Irish fiddler in five days? How ‘musical extreme sports’ connects.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for March 19, 2018

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

This weekend, the war over good governance took the form of a volley of 280-character grenades.

When the Trump administration fired a Federal Bureau of Investigation official, the president tweeted that the agency was “in tatters” and the firing was a “great day for democracy.” A former head of the Central Intelligence Agency begged to differ, telling the president, “[Y]ou will not destroy America...America will triumph over you.”

It was an extraordinary bit of social media brinkmanship even for this unique time in political history. President Trump’s tweets came increasingly near the core tension of his administration: With his voters’ blessing, Mr. Trump dearly wants to be America’s CEO.

The problem is, that’s not what the Founding Fathers envisioned.

There is a genius to democratic government. It is the means by which societies solve problems. When the gears are jammed, it’s probably because society’s gears are jammed – and unjamming them with a CEO’s penstroke generally means running roughshod over someone’s liberties.

Small government? Big government? One fascinating study suggests that’s irrelevant. Good government is what matters. And in that project, the Founders might suggest, we are the CEOs.

Here are our five stories for the day, looking at whether trade has to create winners and losers, what greatness means to President Vladimir Putin, and how some communities are taking a different approach to gun violence.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

In Illinois, Democrats face a test of ‘big tent’ values

An antiabortion Democrat? In Chicago – and across the United States – Democrats are in the beginning stages of defining their identity in the age of President Trump.

This district in the southwest Chicago suburbs, home to Midway Airport, was once heavily populated with working-class Irish Catholics and Poles. Now it’s got hipster enclaves and is 30 percent Hispanic. It’s also home to Rep. Dan Lipinski of Illinois, who is something of an endangered species: He's one of the last Democrats in the House of Representatives who consistently vote against abortion rights. And he is facing extinction, in the form of a primary challenge from a pro-abortion-rights political neophyte, Marie Newman, in the Illinois primary on Tuesday. It’s not the only battle between Democrats this primary season. In suburban House districts from Boston to Houston, to the US Senate race in California, progressives newly energized in the era of President Trump are challenging establishment Democrats from the left. The efforts are testing the poles and guylines that hold up the supposedly “big tent” party. They also underscore a fundamental tension for Democrats heading into the midterm elections: Is the party better off focusing on its activist base and driving up enthusiasm? Or should it be tacking to the center in an effort to win back some Trump supporters? “Some of the civil war that the Republicans have been going through for nine years is in the beginning stages within the Democratic Party,” says Nathan Gonzales, editor of Inside Elections.

In Illinois, Democrats face a test of ‘big tent’ values

In recent days, dozens of anti-abortion activists, mostly college students giving up their spring break, have descended on the Chicago suburbs to canvass for votes – for a Democrat.

Rep. Dan Lipinski of Illinois is something of an endangered species: one of the last Democrats in the House of Representatives who consistently votes against abortion rights. And he is facing extinction, in the form of a serious primary challenge from an abortion-rights political neophyte, Marie Newman, in the Illinois primary on Tuesday.

It’s not the only battle between Democrats this primary season. In suburban House districts from Boston to Houston, to the US Senate race in California, progressives newly energized in the era of President Trump are challenging establishment Democrats from the left. The efforts are testing the poles and guylines that hold up the supposedly “big tent” party. They also underscore a fundamental tension for Democrats heading into the midterm election season: Is the party better off focusing on its activist base and driving up enthusiasm? Or should it be tacking to the center, in an effort to win back some Trump supporters?

Ms. Newman labels her opponent a “Trump Democrat,” while her supporters send out fundraising emails to help her oust this “DINO” (Democrat in name only) who “inherited” his seat from his father. A March poll conducted for the abortion rights group NARAL, which backs Newman, had the race at a statistical tie, with Congressman Lipinski slightly edging out his opponent, 43 percent to 41 percent.

To Newman, the conservative Lipinski no longer fits with this district in the southwest Chicago suburbs. An area that is home to Midway Airport, it was once heavily populated with working-class Irish Catholics and Poles. Now it’s got hipster enclaves and is 30 percent Hispanic.

For his part, Lipiniski likens the insurgencies of progressives like Newman to the “tea party of the left.” A seven-term congressman, whose father held the seat for six terms before him, he co-chairs the Bipartisan Congressional Pro-Life Caucus in the House, as well as the shrinking caucus of moderate Blue Dog Democrats. He voted against the Affordable Care Act, the Dream Act to protect young, unauthorized immigrants, and had opposed marriage equality.

But as his district changed, so have some of his positions. He voted against the GOP effort to repeal Obamacare, and now says he supports marriage equality and would vote for the Dream Act.

He’s still anti-abortion, however – and this has become a focal point in the campaign. While Democratic leaders such as House minority leader Nancy Pelosi and New Mexico Rep. Ben Ray Luján, who heads up the House Democratic campaign arm, maintain that there is no “litmus test” over the issue, progressives see it differently.

Both NARAL and Emily’s List, which supports abortion-rights female candidates, are backing Newman, as is Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D) of Illinois, a member of the House Progressive Caucus.

“I assure you that this district is overwhelmingly pro-choice,” Congresswoman Schakowsky said at a press conference last month, where her Democratic colleague Rep. Luis Gutierrez, also of Illinois, backed Newman. He faults Lipinski for his views on immigration. “He would be all right in Congress in 1996,” Congressman Gutierrez said.

The two lawmakers have split from the Democratic congressional leadership, which traditionally backs incumbents and is supporting Lipinski, along with the AFL-CIO and the local Democratic political machine.

“I support Dan Lipinski in this particular race. We are a big-tent party,” said Rep. Joseph Crowley (D) of New York, at a press conference last week. Mr. Crowley chairs the Democratic caucus in the House.

Regardless of who wins on Tuesday, this is a safe Democratic seat – as is the case in several other high-profile Democratic primary battles. In the Boston area, Rep. Michael Capuano, who is much more liberal than Lipinski, is trying to fend off a primary bid from Ayanna Pressley, the first African-American woman elected to the Boston City Council. In California, veteran Sen. Dianne Feinstein is being challenged by the progressive state Senate leader Kevin de León. She is the only Democratic senator facing a primary challenge – and is expected to win.

That’s a point that independent political observer Nathan Gonzales, editor of Inside Elections, wants to bring home.

“We’re not seeing a large number of challenges to incumbents,” he says. “At the same time, I think we are seeing an anti-establishment left forming.” In some instances it’s being driven by ideology, while in others it may be as much a desire to throw out the old guard in favor of some fresh faces. Senator Feinstein, for instance, is an octogenarian; leader Pelosi, a septuagenarian.

“Some of the civil war that the Republicans have been going through for nine years is in the beginning stages within the Democratic Party,” Mr. Gonzales says, pointing to the rise of the Bernie Sanders wing of the party. (Senator Sanders of Vermont is himself an Independent.)

Should Democrats retake the House, it’s hard to say what the tension between the left and center wings of the party would mean in terms of governing.

Bill Schneider, former senior political analyst for CNN, now at the University of California at Los Angeles, points out that the liberal constituency has always been there – but feels its “time has come” now that Hillary Clinton, seen as the establishment, has been defeated.

“If Democrats win a majority in the House, it will be a matter of weeks before a bill of impeachment is filed [against Trump], and that will be the main story thereafter.”

Others don’t see it that way. In order to flip the House, Democrats will have to win many GOP swing districts and make inroads into rural ones, with candidates who “fit” with those constituents. It was a more conservative Democrat, for instance, who won the special election in Pennsylvania’s 18th district last week.

“Impeachment is in the Constitution and must remain a last resort, not the first thing you turn to when you don’t like who’s in charge,” says Rep. Gerry Connolly (D) of Virginia. “If we win, we have to be perceived as fair, and not in a rush to judgment. We can’t look like a bunch of Salem witch judges.”

Congressman Connolly warns against ideological purity and orthodoxy, and says he has personally felt ostracized by more progressive members on one of his issues, free trade. “I didn’t always feel that my party was going to protect me for daring to represent my district,” he says. “As an individual member, I didn’t feel my party had my back.”

Share this article

Link copied.

For heartland farmers, Trump support gets snagged on trade, tariffs

From the vantage point of Midwestern farmers, President Trump's steel tariff looks as if he's choosing manufacturing over agriculture. But it might not need to be an either/or choice.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

President Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs, set to take effect March 23, pack a one-two punch in the heartland. They drive up the cost of farming equipment and risk retaliation from other countries that would affect US agriculture, which is already facing historically low prices. “For the most part, we’ve been really pleased with Trump’s policies…. But we are really concerned about trade,” says Glenn Brunkow, a fifth-generation farmer and board member of the Kansas Farm Bureau, who is in Washington this week meeting with his state representatives. Part of the solution, says Darci Vetter, who grew up on a Nebraska farm and served as America’s chief agricultural negotiator from 2014 to 2017, could be changing the trade conversation from its current focus on winners and losers. “We haven’t put our energies into saying what would make our economy more productive,” she says, “what would make our job situation more stable, especially in those communities that have found that they’ve not been on the winning end of global competition.”

For heartland farmers, Trump support gets snagged on trade, tariffs

Glenn Brunkow eases his pickup past the land his great-great-great-grandfather homesteaded in the 1860s, pointing out the rich soil where he’ll grow soybeans this year, and then turns into a cow pasture.

It’s calving season, his favorite time of year in Kansas.

“This is kind of like Christmas, coming out here every morning,” says Mr. Brunkow on a brisk March day, stopping to wait for a calf in his path as it takes a long, deep draught from its mother’s udder. “I like coming and finding a new calf nursing.”

But farmers here in Trump country recently got a far less welcome present from Washington: tariffs on steel and aluminum. It’s a 1-2 punch that hits hard in the Heartland. Not only are the soon-to-be implemented tariffs already driving up the cost of farm equipment, but other countries are threatening to retaliate by targeting US agricultural exports.

This is just the latest trade move that could have serious ramifications for farmers – a key part of President Trump’s political base. Mr. Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal has cut off beef producers from some of the world’s fastest-growing markets. And overhauling the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) could jeopardize relations with two of American agriculture’s best trading partners – Mexico and Canada.

“For the most part, we’ve been really pleased with Trump’s policies…. But we are really concerned about trade,” says Brunkow, a board member of the Kansas Farm Bureau who is in Washington this week meeting with his state representatives. “I don’t think that Trump understands the yin and yang of trade.”

Many Midwestern Republicans in Congress have also criticized the tariffs.

“Every time you do this, you get a retaliation,” Sen. Pat Roberts (R) of Kansas, who chairs the Senate agriculture committee, recently told reporters. “And agriculture is the No. 1 target. I think this is terribly counterproductive for the ag economy, and I’m not very happy.”

Invoking national security

In an unusual move, the president justified the tariffs, which are set to take effect on March 23, by invoking a rarely used section of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. The White House argued that steel and aluminum are crucial to producing certain military hardware. It also said that the low prices of imports have weakened the US steel and aluminum industries, which have lost nearly 100,000 US jobs since 2000.

The new tariffs – 25 percent for imported steel and 10 percent for aluminum – were welcomed by Trump supporters and even some Democrats in the Rust Belt.

But they couldn’t have come at a worse time for farmers, who are facing historically low prices for crops and drastically eroded purchasing power.

Kevin Cooksley of Nebraska describes his current situation by offering an anecdote: In 1948, his grandfather could sell a yearling bull and use the money to buy a new pickup truck. Today, Mr. Cooksley says, he would have to sell around 15 bulls to afford such a purchase.

Some have criticized Trump for playing one part of his base off another, choosing manufacturing over agriculture. “It is dismaying that the voices of farmers and many other industries were ignored in favor of an industry that is already among the most protected in the country,” said the US Wheat Associates and the National Association of Wheat Growers in a joint statement.

Part of the solution may lie in shifting the trade conversation from its current focus on winners and losers, says Darci Vetter, who grew up on a Nebraska farm and served as America’s chief agricultural negotiator from 2014-17, including on the TPP.

“Instead of using those who feel really left behind by the global economy as a sort of rallying point, why haven’t we used them as a consensus-building point?” she asks in an interview. “We haven’t put our energies into saying what would make our economy more productive, what would make our job situation more stable, especially in those communities that have found that they’ve not been on the winning end of global competition.”

Trade under attack

While there has long been a consensus in America about the importance of trade, that has changed in recent years, according to Brian Kuehl, executive director for Farmers for Free Trade, a bipartisan lobbying group that was formed in response to the 2016 election, in which all the candidates targeted trade.

“I think from our perspective, alarmingly, [that consensus] has eroded within agriculture – which is a little bit of a head-scratcher, because if there’s one industry in the United States that benefits unambiguously from trade, it’s US agriculture,” said Mr. Kuehl, speaking at a March 13 symposium at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln.

The US agricultural economy exported $135 billion worth of products in 2016, including roughly half of all rice, wheat, and soybeans produced in the US. Nebraska is one of the most prolific exporters – No. 1 in beef, and among the top five in corn and soybeans.

“It’s very short-sighted to have tariffs,” says Roger Wehrbein, a former legislator and beef producer from eastern Nebraska who has been studying tariffs in the early 1800s. “They have never worked in history.”

The White House has singled out China, but it ranks 4th in US aluminum imports – and 11th in steel, well below Canada and Mexico, though those two countries will be granted temporary exemptions.

Some speculate that Trump is using the tariffs as leverage in NAFTA negotiations. But the danger is that other countries could start relying more on non-US suppliers during this time of uncertainty, and US ag producers will then be hard-put to reenter those markets.

That’s also a concern with TPP, says Don Hutchens, who worked for 28 years with Nebraska Corn Board to open new markets.

“That discussion is going on [between] 11 countries without us,” he says. “Unfortunately, if you’re not at the table, you don’t have a voice…. And if you don’t have a voice for very long, people kind of forget who you are. And once they realize they can get commodities from other countries at comparable prices and quality, then we’ve really shot ourselves in the foot.”

Take, for example, China’s imported soybean market, where US market share is already slipping. Brazil has increased its soy exports to China 270 percent just in the past year. If China retaliates with tariffs against US soybeans, Brazil could expand its production to fill that void, says Steve Wellman, director of Agriculture for Nebraska.

“I don’t think it would be easy to recuperate from,” says Mr. Wellman, a farmer and former president of the American Soy Association.

For Brunkow, the fifth-generation Kansas farmer, it's not just about preserving his family’s farm business, but America’s.

“That’s one of the things that’s always made the US so strong, is we’ve had a great ag foundation,” he says, as he rolls back up his driveway, where lambs are tottering around a paddock with their shaggy moms. “And we need to keep that.”

Patterns

Putin won his mandate. Can he deliver on promise of restored glory?

President Vladimir Putin's reelection probably won't change the fact that Russia remains light-years behind the West economically. But he will at least make sure Russia is heard and respected.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Ned Temko Correspondent

Restoring Russia’s prestige has been at the core of President Vladimir Putin’s 18 years in power. But since 2014, when he unilaterally annexed Crimea, he has displayed a new assertiveness in achieving that aim. So far, Russia-watchers have assumed that Mr. Putin has pushed the limits internationally largely because he could. In Syria, Russia moved militarily only when the United States and Western Europe showed their aversion to major involvement. Yet the nerve-agent attack in Salisbury, England, likely surprised Putin with the Western unity it provoked. There is no doubt, however, about his commitment to “making Russia great again” by turning back the clock to a time of Soviet empire. Part of it is geopolitics; NATO is on his doorstep. But the deeper roots come from a historical insecurity. The problem is that Russia retains key areas of Soviet-era vulnerability. The competitive parts of the economy are mainly related, as in Soviet times, to military or intelligence services. Otherwise, the economy rises and falls along with oil, gas, and other resources. It’s not clear the West’s protests will yield stronger action. But in any tug of war, Putin will be aware he’s not the only one with leverage.

Putin won his mandate. Can he deliver on promise of restored glory?

The only missing touch from Vladimir Putin’s predictable march to another six years in power on Sunday was a new Kremlin Twitter handle: #MRGA.

“Make Russia Great Again.”

But MRGA was not just central to Mr. Putin’s election campaign. It has defined his first 18 years in power. What has changed, since Russia’s unilateral annexation of Crimea from Ukraine in 2014, is the assertiveness, and range of weapons, he has been ready to use in hopes of achieving that aim.

With air power, he has helped Syria’s Bashar al-Assad besiege and bomb urban areas with tens of thousands of helpless civilians trapped inside. Russia has used cyber weaponry to muddy the political waters, and even try to tip the electoral scales, in Western Europe and the United States. Just two weeks ago, a Soviet-era nerve agent was used against a former Russian double agent and his daughter in the quiet cathedral town of Salisbury in southern England.

The question now is the degree to which a reelected Putin will continue on this path – especially since he knows that, at least economically, Russia has come nowhere near to erasing fundamental weaknesses from the Soviet era.

So far, the assumption of Russia-watchers has been that Putin has been pushing the limits internationally largely because he can. A concerted Western response to Crimea did seem at least to prevent full-scale military intervention in Ukraine. In Syria, Russia moved in militarily only when the US and Western Europe had made clear their reluctance to risk major involvement, even after President Assad used chemical weapons. The nerve-agent attack in Salisbury came at a time when – with policy toward Moscow uncertain in Washington, and Britain’s ties with European allies strained by Brexit – Putin would have not expected the degree of Western unity, and anger, it has provoked.

There can be no doubt, however, about his continuing commitment to MRGA. Born a few months before the death of Josef Stalin, Putin grew up during Nikita Khruschev’s truncated rule, then lived under the long period of what the former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev would later call zastoi – stagnation – when Leonid Brezhnev was in power. In the mid-1970s, Putin joined the KGB. He served in the foreign intelligence organization for more than 15 years, until after the fall of the Berlin Wall, when he was stationed in the former East Germany.

With its client regimes toppled in Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union itself was dissolved in December 1991. Putin himself has described this as the defining tragedy of his and his country’s life. Turning back the clock – not to Communism, but to a time of Soviet empire – is what MRGA means for him.

Part of it is geopolitics. Shorn not just of the old satellite states in East Europe but of former Soviet republics, Putin has seen Russia’s area of political and military control cut back dramatically. NATO is, essentially, on his doorstep. But the deeper roots are psychological. They come from Russia’s historical sense of being not quite a full member of the wider world. Not quite respected.

Before the election, Putin delivered a major security address. The part that grabbed world headlines was a show-and-tell presentation of purportedly new nuclear arms capable of breaching US defenses. But the words he chose to make his point were more telling. By the time the USSR collapsed, he said, Russia’s military might was weakening. “Nobody wanted to listen to us.”

Then came the kicker line: “So, listen now.”

This mix of resentment and truculence strikes a chord with many Russians. That’s one reason Putin’s message has been so successful domestically. It helps explain why he would surely have won this latest election – even without his moves to crush any real opposition, any credible political rival, any attempt by journalists to hold his regime to account.

The problem is that for all the shows of assertiveness, even aggression, Russia retains key areas of Soviet-era vulnerability. It is true that in cities like Moscow and St. Petersburg, Russians who can afford them have access to consumer products unimaginable in Soviet times. For the hundred-or-so top oligarchs in Putin’s orbit, there are levels of personal wealth dizzyingly greater than he could have imagined as a young man growing up in what was then Leningrad.

But in place of centrally run state socialism, Putin’s Russia has state capitalism, with a thin slice of oligarchical riches on top. Some parts of the economy are on a par with the world’s advanced countries. Yet they’re mainly the ones related, as in Soviet times, to the military or intelligence services. Otherwise, the economy rises and falls on the market for oil, gas, and other resources it can extract from the ground.

The collapse of world oil prices that drove Russia – and Putin’s own opinion poll numbers – into recession a few years ago has eased. Through an understanding with the Saudis to restrain world production, oil prices have recovered and stabilized. Russia’s economy is growing again, if not as quickly as before.

But the price can still fall. The Saudis are more natural allies of Washington than Moscow. Major financial centers like London also have levers through which they could crack down on billions of pounds of assets held there by Russian oligarchs.

Even with the depth of anger over the nerve-agent attack, it’s not yet clear whether the West’s diplomatic protests will give way to stronger action. But in any tug-of-war, Putin will be aware that he’s not the only one with leverage.

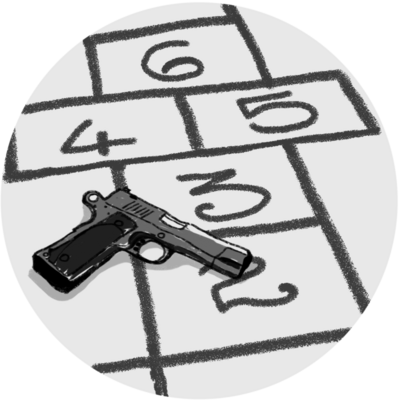

How treating gun violence as public-health issue could help children

Shootings are just one part of how gun violence affects the lives of young people in America. Helping them, many experts say, begins with addressing the fear the bullets leave behind.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Whether they’re shouting from capitol rotundas or speaking volumes through 17 minutes of mass silence, young people are forcing the United States to hear new facets of the gun control debate. More and more, adults who research violence and work to prevent it are listening – and bringing youth voices to the center as they try to better understand the role firearms play in young people’s lives. They are part of a growing movement to treat gun violence as a public-health problem. “Children … are really begging for adults to help them feel safe,” says Joel Fein, an emergency room physician and co-director of the Violence Prevention Initiative at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “What they know innately is when a child doesn’t feel safe, they cannot develop … in terms of the social, emotional, and intellectual growth that they need to become healthy adults.” In Philadelphia, homicide is the leading cause of death for teens and young adults, and 1 in 8 high-schoolers carries a weapon to school in a given month, CHOP reports. After young people spend three to six months in the hospital's violence prevention program, some become peer educators. “They are so resilient and take what has happened to them and turn it around to make sure it doesn’t happen to someone else,” Dr. Fein says.

How treating gun violence as public-health issue could help children

When he visits his grandmother in West Philadelphia, 16-year-old Horace Ryans III sometimes hears gunshots. It’s scary. But the gunshot that affects him the most happened before he was born. It killed his uncle, sitting defenseless in a car in the neighborhood.

“A picture [of him] hangs on my grandmother’s wall, and every time I walk into her house I see him,” Horace says. “If I one day get put into a terrible situation where I am a victim of gun violence, that could be me on my grandmother’s wall.”

Horace, a sophomore at Science Leadership Academy, participated in the walkouts on March 14, conducting interviews on gun violence and registering students to vote. As a member of the Philadelphia Youth Commission, he’s helping with a March 22 youth-voices forum on the topic, and he plans to attend Saturday’s March for Our Lives in Washington.

Whether they’re shouting from capitol rotundas or speaking volumes through 17 minutes of mass silence, young people like Horace are determined to make the country hear facets of the gun control debate. From their perspective, narrow proposals to boost school security, while necessary, don’t satisfy.

More and more, adults who research violence and work to prevent it are listening – and bringing youth voices to the center as they try to better understand the role firearms play in young people’s lives.

“Children … are really begging for adults to help them feel safe,” says Joel Fein, an emergency room physician and co-director of the Violence Prevention Initiative at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). “What they know innately is when a child doesn’t feel safe, they cannot develop … in terms of the social, emotional, and intellectual growth that they need to become healthy adults.”

An estimated 19 children a day die from or are treated for gunshot wounds in the United States. Among all high-income countries, the US accounts for 91 percent of firearms deaths for children up to age 14, a new Pediatrics article reports.

Yet being shot – intentionally or accidentally – isn't the only form of harm young people face, experts say. What about the child who sees her mother threatened with a gun by a boyfriend? Or the teen robbed at gunpoint on the way to school?

Despite two decades in which it’s been difficult to get federal funding for gun research, a number of projects are taking stock of the effects of firearms on children – and also the factors that may boost their resiliency. They are part of a growing movement to treat gun violence as a public-health problem.

Listening to young people about guns

Kimberly Mitchell and her colleagues at the University of New Hampshire’s Crimes against Children Research Center have been listening extensively to young people talk about the role of guns in their lives.

In an Appalachian community in Tennessee, in Boston, and in Philadelphia, they've asked older children (and parents, on behalf of young ones) about hearing and seeing gunshots and being threatened with firearms. They've asked how upset or scared each incident made them feel and whether it made them hide or change their route to school.

These are among many questions being tested as they develop Youth-FiRST, a pioneering assessment tool that will cover firearm exposure, access, and safety practices.

“I’m a big believer in self-report data, because so much of [what we’re asking about] does not even reach the attention of officials,” says Dr. Mitchell, a psychology research professor.

Mitchell estimated in a 2015 study that 1 in 33 children nationally have been directly or indirectly victimized by a highly lethal weapon such as a knife or gun at least once during their lifetime.

Her current work is funded by the National Institutes of Health. Mitchell hopes to have data analyzed within a few months and to eventually develop a national assessment.

Gun safety practices are another element her survey covers.

Twenty-six years ago, the American Academy of Pediatrics noted that households without firearms were safest for children, but that risk could be reduced if guns were stored locked and unloaded.

Yet progress on this front has been slow. Among households with children at risk for self harm, 43 percent have guns, an article this month in Pediatrics reports. Of those households, 35 percent store the guns locked and unloaded, slightly more than the 32 percent of homes where the children have no history of risk factors.

When people receive safe-storage counseling from doctors, they tend to improve their practices, Fein says. He and colleagues from the University of Pennsylvania are researching better ways to get pediatricians to do more of that counseling.

Determining levels of risk

Emergency-department doctors have known for some time that youths seeking treatment for a violence-related injury are at greater risk for future gun violence – either as a victim or a perpetrator. But Jason Goldstick and colleagues at the University of Michigan have developed a scoring system to better sort out levels of risk even among those who come in for nonviolent injuries.

They analyzed data from a two-year study of 14- to 24-year-olds who had been treated by an emergency department in Flint, Mich.

The survey items that proved most practical and predictive, according to the researchers, were the frequency with which the person had been threatened with a gun, the frequency of hearing gunshots, how many of their friends carried weapons, and how many fights they’d had in the past six months.

Those items became a 10-point “SaFETy” score, published last year by the Annals of Internal Medicine. Among youths who scored 9 or 10 on the scale, 100 percent were involved in firearm violence within two years of their emergency department visit. For scores of 6 to 8, 81 percent; for scores of 0, only 18 percent.

The study only involved youths who reported substance use (mostly marijuana), but if further research externally validates it as a screening tool, the SaFETy score could be useful in urban emergency departments – “critical access points [for] … difficult-to-reach populations that you might not find in school,” Dr. Goldstick says.

Moving away from 'treat and street'

In Philadelphia, homicide is the leading cause of death for teens and young adults, and 1 in 8 high-schoolers carries a weapon to school in a given month, CHOP reports.

The hospital’s Violence Intervention Program (VIP) seeks to assist victims and their families break cycles of interpersonal violence. They provide counseling and help them navigate complex medical, municipal, and social support agencies. It’s part of CHOP’s larger Violence Prevention Initiative, which addresses everything from domestic violence to school bullying.

CHOP’s work is recognized as a model and is one of 32 members of a national network of such programs. These hospitals are shifting away from the traditional “treat and street” approach that many took when “it was thought there was nothing we could do” about cycles of violence, Fein says.

After young people in VIP spend three to six months learning about trauma and working on recovery goals, some become peer educators.

“They are so resilient and take what has happened to them and turn it around to make sure it doesn’t happen to someone else,” Fein says. That’s also what’s been so encouraging to him about the recent wave of youth activism in the wake of the Parkland, Fla., shooting. “We draw strength from the people that we are supposed to be taking care of.”

An Irish fiddler in five days? How ‘musical extreme sports’ connects.

If music is the universal language, it sure has a lot of dialects, and the violin speaks most. In this case, with an Irish lilt.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Dina Kraft Correspondent

In a documentary being aired on public television this week after St. Patrick’s Day, classically trained violinist Daniel Hoffman takes us to Ireland, where in less than a week he tries to learn the Irish fiddle. He explores not just the tempos and rhythms that make Irish fiddle playing unique, but the soul and history of Ireland itself. He interviews Irish musicians, including master fiddler James Kelly, steeped in the history and culture that inform what has become one of the most popular traditional music forms in the world today. “My thinking is that Irish music was like Irish storytelling and Irish poetry,” says a musician and composer who was one of Mr. Hoffman’s guides. Israeli-American Hoffman hopes the film will be the first in a series of documentaries about his learning to play a variety of styles, including the folk music of South India, Sweden, Greece, Romania, and West Virginia. That would add to his repertoire, which already includes Klezmer and Mediterranean styles. The beauty of the violin, Hoffman tells us, is that it has “the amazing ability to speak almost every musical language.”

An Irish fiddler in five days? How ‘musical extreme sports’ connects.

About 20 years ago, Daniel Hoffman, a classically trained violinist who had turned his bow to Klezmer, found himself on the back of a moped of a fellow violinist, weaving through the back streets of Marrakech’s Old City for what would be his first lessons in Andalusian music, the classical music of North Africa.

Mr. Hoffman and his teacher that week, a young musician he met playing in the town square, communicated in the little French they both knew, but their main common language was music.

“He played, and I copied him,” Hoffman recalls, sitting on a closed-balcony-turned-music-studio overlooking fuschia bougainvillea and neighboring boxy concrete buildings in Tel Aviv, where he now lives.

That experience gave birth to an idea: What would it be like to try to learn how to play different violin styles around the world? And in just one week? Oh yes, and at the end of that week, play a concert. He even has a name for the concept: “musical extreme sports.”

It took almost two decades and a friend introducing him to the wonders of Kickstarter, a funding platform for creative projects, to launch that dream, which has taken the form of a new documentary premiering on American public TV stations this week called, “Otherwise, It’s Just Firewood.”

In the documentary Hoffman travels to County Clare, Ireland, where he takes lessons with James Kelly, a master Irish fiddle player, for less than a week and then performs together with him in front of an audience, many of whom are fellow star Irish musicians.

'Like Irish storytelling'

Amid scenery full of the requisite sheep grazing on green hillsides, and traveling down roads lined with squat stone walls, Hoffman explores not just the tempos and rhythms that make Irish fiddle playing unique, but the soul and history of Ireland itself. He interviews Irish musicians, Mr. Kelly included, steeped in the history and culture that inform what has become one of the most popular traditional music forms in the world today.

“My thinking is that Irish music was like Irish storytelling and Irish poetry,” says musician and composer Paedar Ó Riada, one of Hoffman’s guides into the soul of Irish music. “It told a story. And people knew the stories, and the structure of the stories, and knew what was going to happen. But it was in the telling of the story that the thrill was.”

The film is what Hoffman hopes will be the first of an eventual series of short documentaries where he learns how to play the violin in a variety of styles, including the folk music of South India, Sweden, Greece, Romania, and West Virginia. That would add to his extensive repertoire, which already includes Klezmer (his specialty), and Balkan, Middle Eastern, and Turkish styles.

The violin, Hoffman intones in the film, over the sounds of musicians playing in styles from around the world, was perfected in its current form 500 years ago in Italy and has “the amazing ability to speak almost every musical language.”

'A different way of thinking'

In the documentary, Hoffman sits with Kelly for five lessons, and we are along for the ride of his struggle – the awkwardness of learning a new style, of his bow going the “wrong way.”

“It feels like the rhythm is never flowing.… It certainly doesn’t sound Irish.… The feel just kind of eludes me,” Hoffman tells Kelly, a musician who is as talented on stage as he is a generous and warm-hearted teacher.

Kelly looks at him and says, “You’ve set yourself up physically to express yourself in another way. In different styles. And now I want you to reshape yourself for another expression. This is the hardest thing about learning another style.… It’s a different way of thinking.”

In between practicing and lessons, Hoffman visits musicians playing at an Irish pub and their homes, all the while trying to unlock what will help him transition – even briefly – into an Irish fiddle player.

“The big joke is what’s the difference between the fiddle and the violin? It’s the person who plays it,” says Niall Keegan, a traditional flute player and associate director at the Irish World Academy of Music and Dance, at the University of Limerick. “It’s the music you make on it which makes it Irish or English or French or classical or jazz or whatever else. It’s how we imagine it. And how we create through it that makes it, that gives it character.”

“Otherwise, it’s just firewood,” he says, words that become the film’s title.

In his Tel Aviv home music studio Hoffman, who was born and grew up in southern California, reaches for his violin and demonstrates the ornaments, the musical term for embellishments or flourishes that give any music its own particular style. Or as he puts it, “it’s the spice, what makes everything tasty.”

On the Irish fiddle that means intricate ornamentation that really drive the rhythm forward, not just to make it beautiful. It’s that rhythm with a punch on the beat, physically seen in the footwork of an Irish traditional dancer.

'Happy music out of tragedy'

Hoffman sees a link between Irish folk music and Klezmer, which first opened his ears up to non-classical music, in the sound and history of both peoples that travel in their notes and melodies.

“I feel something similar in Irish music in a way that there’s lots of this happy music coming out of a lot of tragedy,” he says.

By the end of Hoffman’s Irish sojourn we see him practicing in the car on the drive over to his concert with Kelly. On the small stage the two face each other, sitting in matching wooden chairs, and begin a pair of duets. The two lean into their instruments and as the music flows, Hoffman seems to have gotten the rhythm down, and he smiles in relief as they finish.

The rapt audience breaks into cheers.

“I was a little nervous, but I was having a good time because playing with James is like getting on this amazing train – he sort of carried me along,” he recalls at his home.

For a few minutes on stage, time seemed to stand still, bringing home Mr. Ó Riada’s musical wisdom, which appears true no matter the genre: “Life is not a return trip. It’s very short. If you knew exactly how many days, hours, and minutes you had left, you wouldn’t waste one second. The only time that life stands still is in the middle of a piece of music. That’s why we play it.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The light that Stephen Hawking leaves behind

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By The Monitor's Editorial Board

Tributes for Stephen Hawking keep showing up in remote parts of the globe. Dr. Hawking is being held up as an icon for humble and intense curiosity, not just for the truth about the physical universe but for universal truths. Why does that matter? In too many countries, leaders have “weaponized” false information to exert power, either at home or in other nations. This is creating a backlash in favor of truth-telling, a movement that needs heroes like Hawking who can inspire others to seek understanding. In countries with a free press, journalists have rallied to fact-check comments by politicians. Tech giants are being forced to install truth filters in their online platforms. Many nations have come to see honest information as a strategic asset. Giants of scientific discovery such as Hawking have long been role models for seeking truth beyond their profession. The tributes rolling in for the man are really tributes to a desire for light over darkness, for truth over all the “black holes” of fake news or misinformation campaigns.

The light that Stephen Hawking leaves behind

Nearly a week after his death, tributes for Stephen Hawking keep showing up in remote parts of the globe. The British scientist is praised for shedding light on black holes. He is admired for not allowing a physical disability to hinder his mental brilliance. Yet in a sign of the state of humanity, he is also being held up as an icon for humble and intense curiosity, not just for the truth about the physical universe but for universal truths.

In too many countries, leaders have “weaponized” false information to exert power, either at home or in other nations. This is creating a backlash in favor of truth-telling, a movement that needs heroes like Dr. Hawking who can inspire others to seek understanding.

Are more people demanding credible facts?

In 2017, a Texas-based data company called Global Language Monitor found “truth” to be the “word of the year” among English-speakers. A debate over the nature of truth “is currently quite the rage,” the company’s analysis found. (Two runner-up words were “narrative” and “post-truth.”)

And in a January report about “truth decay” in American civil discourse, the RAND Corp. found the erosion of trust in key institutions has left “people searching for new sources of credible and objective information.”

In countries with a free press, journalists have rallied to fact-check comments by politicians. Harvard University now offers a free one-hour online course to help people “better distinguish good information from bad” in hopes they will not “share the bad.” Tech giants such as Facebook are being forced to install truth filters in their online platforms. A report this month for the European Commission charges that the online sites “are becoming increasingly important as both enablers and gatekeepers of information.” They should reveal how their algorithms select news items, the report stated.

Many nations have come to see honest information as a strategic asset. “Truth matters,” says Mike Pompeo, director of the Central Intelligence Agency and nominee to be secretary of State. “Relying on Twitter feeds and news reports will prove wholly insufficient when policymakers have to make some of the most difficult decisions they face.”

Giants of scientific discovery such as Hawking have long been role models for seeking truth beyond their profession. “In recent years I realized that [Hawking] has become a symbol for mankind,” says physicist Bobby Acharya. “People looked to him for reason and truth.”

The tributes rolling in for the man are really tributes to a widespread desire for light over darkness, for truth over all the “black holes” of fake news or misinformation campaigns.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Thinking differently about politicians

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Rosalie E. Dunbar

Today’s contributor shares how cynicism about a local election lifted as she considered what it means to follow the Bible’s counsel to “love one another,” even in the face of a polarizing public figure.

Thinking differently about politicians

Many of us would agree these are partisan and polarizing times, whether it’s one government trying to influence another country’s citizens or various ways politicians try to get votes in their own country. I’ve always tried to avoid the fray of partisan politics but recently found myself getting drawn in, and I didn’t like it.

This came to light as I was thinking about a conversation I’d had with some friends about a certain politician running for reelection. I told them that my only criterion for her opponent was that the individual be “breathing,” such was my opposition to this candidate. At the time we all laughed, but when I thought about it later, I realized that this kind of mind-set only served to fuel a sense of polarization and frustration.

A Bible passage I’ve often found helpful came to mind so strongly that I could practically hear Christ Jesus’ words ringing in my ears: “A new commandment I give unto you, That ye love one another; as I have loved you, that ye also love one another. By this shall all men know that ye are my disciples, if ye have love one to another” (John 13:34, 35).

I noticed that Jesus didn’t say to love everyone except politicians or only “if he or she thinks the same way you do.” So I had to ask myself, What does it mean to love another, especially if that person is a public figure seeming to have a polarizing effect?

I realized that in the past I’d seen how helpful it had been when I had striven to see others in a more spiritual light instead of reaching a snap judgment. So I decided to take that approach.

I thought of how Jesus had to deal with all kinds of leaders, and he could be tough when he needed to be. But the crucial point was that he wasn’t seeing them as simply flawed human beings, outside of God’s love. To him, all were in reality God’s spiritual creation, each one useful and loved.

This helped me see that the particular politician I had been reacting to, and all people, are worthy of God’s love as the children of the one divine Mind. This is not to say that we must, or should, love all of everybody’s actions. It means distinguishing the material mentality that leads to selfish or self-serving actions from the spiritual qualities that represent the Mind that is God - such as intelligence, wisdom, foresight, and patience. We are all equally essential to God’s creation, but our importance stems from the spiritual nature we each have, which is not defined by measures such as education, wealth, contacts, and so on.

As I thought about these points in relation to my feelings about this particular politician, I realized that if my criterion for an effective politician was that he or she simply be breathing, then the candidate I was opposed to actually met my criterion: She was breathing!

At first I laughed at this insight. But I also felt deservedly rebuked at being so judgmental. I realized the responsibility each of us has to support integrity in government, and to have true compassion for those in public service. God’s presence and power are there for all, regardless of gender, political affiliation, or background. We’re all so much more than the positions we take on issues and the parties we choose to support.

Naturally, we do have to make choices in voting. But I’ve found that taking time to consider the spiritual nature of all involved can open my heart to productive discussion, and guide my individual decision as to which candidate I feel is best suited for a public leadership role.

As I’ve considered the upcoming election in my area from this more spiritual basis, I have found myself thinking differently about it. Instead of seeking to find things that were wrong with this individual, I’ve been listening to her statements, as well as to the comments by her opposing candidates. I’ve discovered that she has some worthy accomplishments, and I have gained in my respect for her.

I can’t project the outcome of the race as the pundits try to do. But I do know that the change in my thinking has enabled me to better evaluate the political issues that need to be addressed and to more objectively consider each of the candidates in the race – all of whom are, indeed, breathing and, more importantly, equally worthy children of God.

A message of love

Rocket train

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, staff writer Jessica Mendoza will take a look at the drive to make video games the spectator sport of the future. It’s NFL meets Xbox. Please come back and check it out.