- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- With departure of swing vote, a pivotal moment for Supreme Court

- In Ocasio-Cortez victory, hints of the Democrats’ future

- Why these young Republicans see hope in climate action

- Into dark cycle of Mideast revenge, this group tries to bring light

- For men of color, a place at the front of the classroom

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for June 28, 2018

Kim Campbell

Kim Campbell

Schools may be on break, but the effort to make progress on keeping students safe is not.

The Secure Schools Roundtable met on Capitol Hill today, sponsored in part by the two-year-old bipartisan Congressional School Safety Caucus. Key groups – including educators and students, lawmakers and law enforcement – were invited to discuss safety and security in K-12 schools.

Student activists are also working to keep the topic in the public eye. Teens from Parkland, Fla. – where Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School was the site of a mass shooting in February – and other students are on a national tour that kicked off on June 15 in Chicago and was headed for Bismarck, N.D., today. A separate local tour is also happening in Florida, where yesterday officials in Broward County, which includes Parkland, voted to allow armed, non-law-enforcement guards in schools that don’t already have school resource officers.

One of the goals of the tours is to register more young people to vote. The students see that as a way to move forward on solutions to gun violence. We are keeping an eye on the momentum of youth activism, which is also addressed in several of our stories today. The movement is in a position to influence not only school safety, but also, it seems, elections.

Now to today's five stories.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

With departure of swing vote, a pivotal moment for Supreme Court

There is a growing perception on the part of voters that Supreme Court decisions are increasingly about setting policy, as opposed to interpreting the law. Will the replacement for Justice Anthony Kennedy boost that perception?

-

Henry Gass Staff writer

Anthony Kennedy was perhaps the least predictable of US Supreme Court justices since President Ronald Reagan nominated him for the high court 30 years ago. “[I]t’s not easy to stuff him in any specific ideological box, whether that’s liberal, conservative, or libertarian, though he had tendencies on certain issues that could be put in one camp or another,” says Ilya Somin, a law professor and former co-editor of the Supreme Court Economic Review. But “predictable” is what President Trump promised to provide conservatives with his nominee. He has vowed to choose potential justices only from a list compiled by White House Counsel Don McGahn, with input from the Federalist Society. The Trump list contains generally young, right-leaning jurists who almost certainly would point the court in a more conservative direction. Any might provide a crucial fifth vote to curtail or overturn Roe v. Wade, the abortion rights case long under attack by social conservatives. Voter approval of the Supreme Court has been slumping for years. What happens if the justices, in the public mind, morph into pure politicians, Democrats or Republicans who happen to be wearing robes? “My concern is that is where we are,” says Charles Gardner Geyh, author of “Courting Peril.” “The court is at risk of being perceived as naked political actors.”

With departure of swing vote, a pivotal moment for Supreme Court

The retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy is a seismic event in American law and government, a shakeup that could orient the US Supreme Court in a different ideological direction and topple long-settled legal precedents – while raising the noise of partisanship in Senate judicial confirmations to unprecedented heights.

Meanwhile, for President Trump, Justice Kennedy’s departure represents an opportunity. With this, his second Supreme Court appointment, Mr. Trump can leave a legacy that will affect America long after he leaves the Oval Office. It would help him fulfill the promise he made to conservatives prior to the 2016 election: Support me and I’ll appoint reliable right-leaning jurists to the federal bench.

But will any (or all) of this affect how the public views the court and its purpose? Voter approval of the Supreme Court has been slumping for years, in step with the decline in trust of virtually all United States institutions. What happens if the members of the court, in the public mind, morph into pure politicians, predictable Democrats or Republicans who happen to be wearing robes?

“My concern is that is where we are. The court is at risk of being perceived as naked political actors,” says Charles Gardner Geyh, a professor at Indiana University’s Maurer School of Law and author of “Courting Peril: The Political Transformation of the American Judiciary.”

Anthony Kennedy, for his part, was perhaps the least predictable of US justices since President Ronald Reagan nominated him for the high court 30 years ago.

“Least predictable,” in this context, is not the same thing as jaw-dropping surprising. Kennedy was a reliable conservative vote on many issues. He wrote the opinion on Citizens United, the 2010 case that allowed corporations the right to make unlimited campaign contributions. He generally supported gun rights. In 2000, he voted in the majority in Bush v. Gore, the voting case that made George W. Bush president.

But legal experts said Kennedy often gave them the feeling that he was genuinely concerned whether he considered both sides of a case.

He sided with more liberal justices to swing the majority in key abortion rights cases, and cases dealing with the legal rights of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people. In Obergefell v. Hodges, he wrote the majority opinion that effectively legalized same-sex marriage in the US. That may go down in history as his most-remembered Supreme Court moment.

“The bottom line is I think it’s not easy to stuff him in any specific ideological box, whether that’s liberal, conservative, or libertarian, though he had tendencies on certain issues that could be put in one camp or another,” says Ilya Somin, a law professor at George Mason University and former co-editor of the Supreme Court Economic Review.

But “predictable” is what Mr. Trump promised to provide with his nominee, or nominees, for the Supreme Court. He has vowed to choose potential justices only from a list compiled by his White House Counsel Don McGahn, with input from the Federalist Society and other conservative legal organizations. (President Hillary Clinton would presumably have been focused on predictability in a nominee from a Democratic perspective, if she were in Trump’s place.)

The Trump list contains generally young, right-leaning jurists who almost certainly would point the court in a more conservative direction. Any might provide a crucial fifth vote to curtail or overturn Roe v. Wade, the abortion rights case long under attack by social conservatives.

Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973 and has the status of settled law. Chief Justice John Roberts has appeared reluctant to overturn precedents – indeed, the stare decisis doctrine of following precedents holds that such action should occur only under unusual circumstances.

But they do happen. On Thursday, by a 5-to-4 vote, the Supreme Court overturned a 1977 precedent under which public sector unions could compel workers to pay “agency fees” for representing them in collective bargaining.

Critics of the public sector union decision worry that it presages more to come.

“If the court is willing to overturn a decades-long precedent that’s so well-rooted in our economy and public sector employment, I think that there will be, with Kennedy’s departure, quite conceivably a five-justice majority to revisit decades-old cases that are similarly well-rooted in our jurisprudence and in our society,” says Steven Schwinn, an associate professor at the John Marshall Law School.

One problem with such whipsawing might be a growing perception on the part of voters that Supreme Court decisions are increasingly about setting policy, as opposed to interpreting the law. In other words, judges picked by Republican and Democratic presidents are in effect extensions of the party caucus.

They’re making decisions that reflect political more than legal priorities.

According to polls, partisan perceptions of the court have widened. Overall approval has dropped steadily in recent years, from about 62 percent positive job approval rating in 2000, to 49 percent last fall, according to the latest Gallup figures.

The confirmation of Justice Neil Gorsuch, President Trump’s first Supreme Court pick, had a dramatic effect on voters’ court views. Republican approval of the court soared from 26 percent to 62 percent, while Democratic approval dropped from 67 percent to 40.

Many Democrats charged that the seat was unfairly taken from Merrick Garland, President Barack Obama’s nominee, who was not even given a hearing by Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell in 2016 after Justice Antonin Scalia died.

But Senator McConnell’s power play was not entirely unprecedented. In reality the Supreme Court selection process has been political from the beginning, says Professor Geyh of the University of Indiana. Between 1844 and 1866 the Senate simply ignored three court nominees, as it did Judge Garland, the chief judge for the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, prior to the 2016 election.

A second wave of politicization, concerned with a judge’s perceived ideology, built in the last decades of the 20th century, according to Geyh. This peaked perhaps with the nomination of Robert Bork in 1987. A Democratic-controlled Senate rejected Bork. This cleared the way for the eventual nomination of Kennedy.

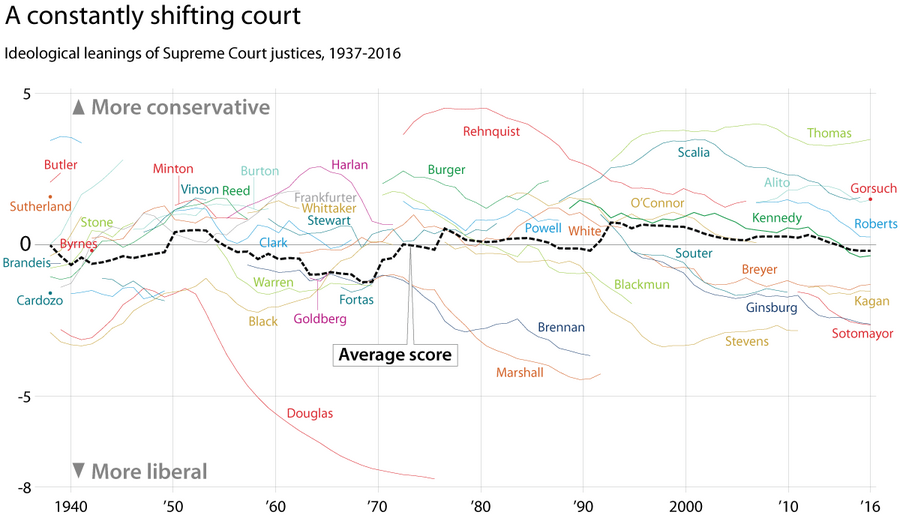

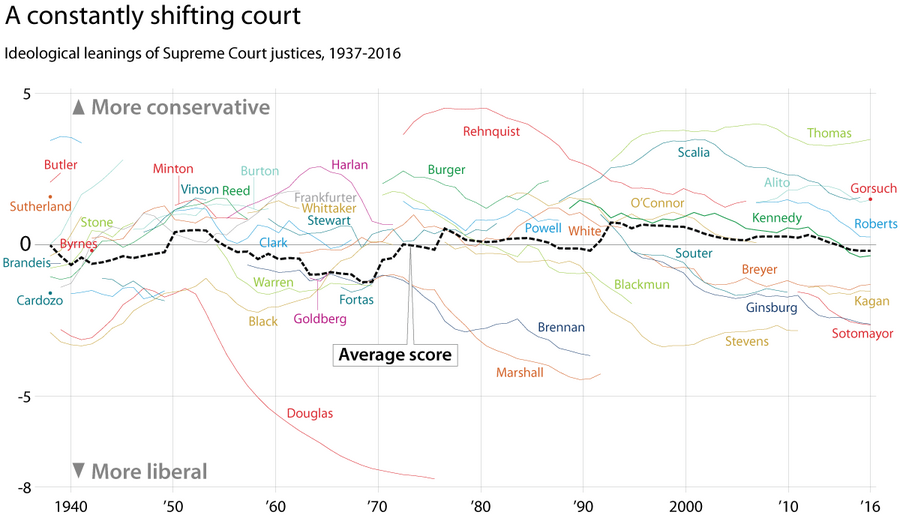

Andrew D. Martin and Kevin M. Quinn. 2002. "Dynamic Ideal Point Estimation via Markov Chain Monte Carlo for the U.S. Supreme Court, 1953-1999," based on the 2017 Release 01 release of the Supreme Court Database and the SCDB Legacy 03 version of the Legacy Supreme Court Database

Ideology remains front and center in Supreme Court picks. But what’s peaking now is what Geyh labels a third wave of polarization, focused on the use of procedural devices to kill judicial nominations. Former Democratic Senate majority leader Harry Reid eliminated filibusters for lower court nominees, for instance, in 2013. McConnell simply refused to consider Garland in an election year. The next year, he abolished the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees to clear the way for Justice Gorsuch to take the Scalia seat.

Such political war makes the prize seem more and more partisan to voters. In recent years the justices themselves have remained collegial – the liberal Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the late Justice Scalia, a rock-ribbed conservative, were great friends. But even that may be eroding as partisan pressures increase.

“What we are desperately in need of is finding common ground as a people,” says Geyh. “Right now things are just so polarized.”

Andrew D. Martin and Kevin M. Quinn. 2002. "Dynamic Ideal Point Estimation via Markov Chain Monte Carlo for the U.S. Supreme Court, 1953-1999," based on the 2017 Release 01 release of the Supreme Court Database and the SCDB Legacy 03 version of the Legacy Supreme Court Database

Share this article

Link copied.

In Ocasio-Cortez victory, hints of the Democrats’ future

Much like Republicans with the tea party, Democrats are being confronted by an energized left wing that could propel the party in upcoming elections – but also portend a growing internal divide.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Linda Feldmann Staff writer

For Democrats, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s primary defeat of Joe Crowley – a veteran congressman twice her age, who was once seen as a potential House speaker – raises profound questions. Is the party heading for a “nasty, tea party-style internal battle” or an “identity crisis,” as some are speculating? Or was Ms. Ocasio-Cortez’s stunning upset a one-off, particular to a changed New York district, as House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi suggests? After all, Mr. Crowley is the first Democratic incumbent to lose in the primary this cycle. The answer may be, a bit of all of the above. What is clear, political observers say, is that the Democratic Party is evolving – as all parties do over time – and its center of gravity is moving to the left in the wake of the Bernie Sanders “revolution.” It’s no accident that Ocasio-Cortez self-identifies as a democratic socialist, as does the Vermont senator, and that she worked as an organizer for his presidential campaign. “There’s no question we’re heading for greater polarization,” says former Rep. David Bonior (D) of Michigan, once the No. 2 Democrat in the House.

In Ocasio-Cortez victory, hints of the Democrats’ future

In hindsight, it makes perfect sense that Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez beat Joe Crowley – a veteran, leading Democratic congressman twice her age – in the primary.

Ms. Ocasio-Cortez’s youth, energy, family story, and left-wing populist message fit the working-class, Latino-majority New York district in a way that Congressman Crowley couldn’t counter. And so the No. 4 House Democrat, once seen as a possible future House speaker, joins the history books as a political giant felled by a grassroots insurgency.

“This campaign sent a national message to all the United States that you have to work for the community,” says Ramón Ramirez, founding president of the United Dominican Coalition, standing in Ocasio-Cortez’s campaign headquarters in Queens. “It’s simple. You have be close to the people. Crowley, he wasn’t very close to the people.”

For Democrats, Crowley’s defeat raises profound questions. Is the party heading for a “nasty, tea party-style internal battle” or an “identity crisis,” as some analyses say? Or was Ocasio-Cortez’s stunning upset a one-off, particular to a changed district, as House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi suggests? After all, Crowley is the first Democratic incumbent to lose in the primary this cycle.

The answer may be, a bit of all of the above. What’s clear, political observers say, is that the Democratic Party is evolving – as all parties do over time – and its center of gravity is moving to the left, in the wake of the Bernie Sanders “revolution.” It’s no accident that Ocasio-Cortez self-identifies as a democratic socialist, as does the Vermont senator, and that she worked as an organizer for his presidential campaign.

“There’s no question we’re heading for greater polarization,” says former Rep. David Bonior (D) of Michigan, once the No. 2 Democrat in the House.

‘Not all Democrats are the same’

To political activists in New York’s 14th Congressional District, it didn’t seem to matter that Crowley had leadership clout in Washington. The same held true in 2014, when No. 2 House Republican Eric Cantor lost his primary to a tea partier, and in 1994, when Democrat Tom Foley became the first House speaker to lose reelection to his congressional seat since 1862.

Mr. Ramírez of the United Dominican Coalition, a political club, focuses on Crowley’s role as the powerful head of the Queens Democratic Party.

“The situation in this community is, the machine decides,” Ramirez says. “You are to be a candidate for the senate. You are to be the candidate for city council. You are to be the candidate for this office, that office. This is the situation, and people are very tired about that.”

In fact, Ramirez used to support Crowley; his club had hosted campaign events during the congressman’s nearly 20 years in office. But Crowley and some of his hand-picked candidates had been paying less and less attention to their constituents, Ramirez says, as Crowley pursued his ambitions in Washington.

It was a message Ocasio-Cortez – until just a few months ago a bartender at a popular Union Square restaurant in Manhattan, and a first-time candidate – hammered home during the campaign.

“It’s time we acknowledge that not all Democrats are the same,” Ocasio-Cortez said in an online campaign video. “That a Democrat that takes corporate money, profits off foreclosure, doesn’t live here, doesn’t send his kids to our school, doesn’t drink our water or breathe our air, cannot possibly represent us.”

As a former Sanders organizer, Ocasio-Cortez sounded many of the same themes as Sanders: Medicare for all, free higher education for all, curbing the “gambling” of Wall Street.

And even as she and her supporters worked tirelessly over the past few weeks – including dozens of young volunteers who came in from all over the country, campaign officials say – Crowley only reinforced the perception that he was more focused on being a Washington insider: he skipped two debates, sending a hand-picked Latina surrogate and former councilwoman to represent him at a debate in the Bronx.

“In a bizarre twist, Rep. Crowley sent a woman with slight resemblance to me as his official surrogate to last night’s debate,” tweeted Ocasio-Cortez, a Bronx native born to a Puerto Rican mother.

The New York Times followed with a scathing editorial about the incumbent’s no shows. “His seat is not his entitlement,” the board wrote. “He’d better hope that voters don’t react to his snubs by sending someone else to do the job.”

United in opposition

They did, resoundingly. Ocasio-Cortez won in a landslide, with nearly 58 percent of the vote. Low turnout – 12 percent – helped her effort, she admits.

It was “actually an incredible opportunity for a grassroots organizer – because when only 3 percent of your electorate turns out, you really just need to inspire a couple thousand people and it can totally change the game,” Ocasio-Cortez said on MSNBC the morning after her victory.

At age 28, running in a solidly Democratic district, she stands to become the youngest woman ever elected to Congress. Ocasio-Cortez never let age or gender deter her, amid a boom of female empowerment in politics. Still, her backers don’t deny the challenges ahead.

“It’s very complicated to be an elected official in this community now, I can tell you, because you have to work with so many different groups, working in different places, just to understand the community,” says Ramírez, rattling off the different ethnic communities of this district: Dominicans, Asians, Russians, Ecuadoreans.

If the divisions within the Democratic Party were put on full display in Crowley’s defeat, then President Trump presents a counter-force that will help unite the party heading into the November midterms.

The retirement of Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, and the prospect of a quick confirmation of a new, conservative justice of Mr. Trump’s choosing, will also unite Democrats.

“I don’t see a looming showdown,” says William Schneider, a visiting professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. “It will be a good year for Democrats, because everything will be about Trump.”

Jesse Ferguson, a spokesman for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign, also plays down the notion of Democratic divisions, even following Crowley’s defeat.

“Nationwide, the Democratic caucus is looking more and more like the Democratic electorate,” Mr. Ferguson says, noting the party’s strength among women, minorities, and young voters.

Ferguson prefaces his remarks by stressing how much he likes Crowley – a point echoed by many leading Democrats in the wake of the party leader’s loss. But, like Crowley himself, they are quick to embrace the new.

In his gracious concession speech, Crowley picked up his guitar and played “Born to Run” – dedicating the song to Ocasio-Cortez.

‘What we’re doing isn’t working’

Campaign manager Virginia “Vigie” Ramos Rios – like Ocasio-Cortez – is a political newcomer inspired by the Sanders campaign.

Surrounded by magic marker-drawn campaign posters in an office overlooking the rusting elevated subway tracks along Roosevelt Ave., Ms. Rios is on the phone with other campaign workers discussing the candidate’s furious lineup of media interviews Wednesday afternoon.

Rios came to New York in 2000 and worked in banking until the financial crisis in 2009. It shaped her profoundly, she says, and in 2016 she went to a meeting hosted by the Sanders campaign.

“I started talking about my own journey towards recognizing the fact that what we’re doing in this country isn’t working.” Organizers recruited her to be a delegate for Sanders at the Democratic National Convention, and she began to learn the art of campaigning.

“I’m still truly a novice in these ways,” Rios says, recounting how she had to collect names for her petition to be a delegate. “But then when I went out and started doing it, I realized, no one’s collecting names, nobody’s organizing us. How do we come together, and work together? So I just started doing that.”

After organizing for a time in California, she returned to New York, where a candidate for a Brooklyn city council seat asked her to be his campaign manager.

And she started developing a strategy, she says, to target non-voters and those registered to vote but who typically don’t. “Everybody kept saying, these groups don’t vote, that group won’t come out, and you can’t talk to all those people,” Rios says.

“But those are the people we need to be talking to, and we kept saying, if we don’t give them something to vote for, what is the point of them voting?” she continues, noting how she continued to target such voters managing the Ocasio-Cortez campaign. “They’re working 10, 12 hours a day, and you want them to take time from their day to go vote? But you’re not offering them anything that they care about.”

“I finally got the elated feeling about two hours ago, maybe,” says Rios, as her phone keeps ringing nonstop. “This morning we were talking, hey, it was great that we won, but there was such a small percentage that voted. What we want to see is a more participatory democracy.”

Why these young Republicans see hope in climate action

Climate change is often painted as a starkly partisan issue. But within the Republican Party, a generational divide has emerged, as some Millennials tug the GOP toward climate action.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

For a segment of young Republicans, climate action is as important an issue as border enforcement, Second Amendment rights, and limiting big government. While climate change remains a starkly partisan topic, some polls show an emerging generation gap when it comes to how younger Republicans view the topic. A Pew Research Center poll released in May found that 36 percent of Millennial Republicans (those born between 1981 and 1996) said they believe Earth is warming mostly because of human activity – double the number of baby boomers in the GOP who say the same. These young Republicans argue that environmental sustainability can be achieved in a way that is compatible with conservative free-market principles. “Student movements historically have often laid claim to the counterculture,” says Alexander Posner, a rising senior at Yale University and president of Students for Carbon Dividends. “The dominant culture today is tribalism and bitter partisanship. By working together … we’re hoping to reorient the tone and tenor of our politics.”

Why these young Republicans see hope in climate action

Emily Collins, a rising junior at Texas Christian University and an executive board member of the TCU College Republicans, cares deeply about many typical conservative issues: limited government, border enforcement, Second Amendment rights, low taxes, increased military spending.

Another topic she’s passionate about: climate change.

“We’re having some sort of negative impact on the environment, and I believe it’s our responsibility to alleviate any negative impacts we’re having, and to be proactive while we can rather than reactive when it’s too late,” says Ms. Collins, a political science major who is spending the summer working for Students for Carbon Dividends (S4CD), a coalition that includes 23 college Republican groups along with a handful of campus Democratic and environmental groups. “I think that younger people care about it more, because we are seeing the effects it’s having.

“It’s more of a pressing issue for us,” she continues, “We see it as an opportunity to take action and make sure the Earth can be safe for generations to come.”

While climate change remains a starkly partisan topic, some polls show an emerging generation gap when it comes to how younger Republicans view the issue. They’re more likely to accept the scientific consensus around climate change and more likely to push for clean energy development. And groups like S4CD and Young Conservatives for Energy Reform are working within that gap to build a grassroots coalition that allows young voters to advocate for climate action without leaving behind their conservative principles.

“Young people are more likely to have studied climate science in school, and to have a high regard for science,” says Alexander Posner, a rising senior at Yale University and president of S4CD. “As young people with generations ahead we have the most to gain or lose from the issue.” Posner adds that he sees a natural role for college campuses and the younger generation to take the lead on bridging the partisan divide.

“Student movements historically have often laid claim to the counterculture,” he says. “The dominant culture today is tribalism and bitter partisanship. By working together … we’re hoping to reorient the tone and tenor of our politics.”

An emerging shift

In a Pew Research Center poll released in May, 36 percent of Millennial Republicans (those born between 1981 and 1996) said they believe the Earth is warming mostly due to human activity – double the number of baby boomers in the GOP who say the same. Millennial Republicans are also more likely than baby boomers to say they are seeing effects of climate change where they live and that the federal government isn’t doing enough to protect the environment. They’re less likely than their elders to support expansions of fossil fuel energy sources like coal mining, fracking, and offshore drilling.

That’s not to say a big partisan divide doesn’t still exist: Young Republicans may be twice as likely as older conservatives to believe human activity is causing the Earth to warm, but the number pales in comparison to Democrats across all generations, where 75 percent hold that belief (and where few generational differences exist). And across generations, Republicans in the poll tended to be in agreement that policies aimed at reducing the effect of climate change either made no difference for the environment or did more harm than good.

“I would see it as an emerging change,” says Cary Funk, director of science and society research at Pew. “We were struck by the differences between Millennial Republicans and older Republicans, particularly on energy issues.… It’s certainly something to keep watching.”

Pew Research Center

That hesitation about climate policies among conservatives is some of what Mr. Posner was hoping to address when he launched S4CD earlier this year. When he talks to other conservatives, he emphasizes mitigation strategies that are underpinned by free-market principles, such as carbon pricing and dividends schemes. He also tries to allow for a range of beliefs on climate science – where even climate-change skeptics might support it as a sort of “insurance policy based around the free market.”

Michele Combs, the chairman and founder of Young Conservatives for Energy Reform (YC4ER), also says she focuses conversations on natural points of agreement – and often avoids mentioning climate change at all, while working to promote renewable, clean energy across the United States, often at the state level.

“Climate change is not a litmus test for us,” she says. “I say this is a marathon, not a sprint, and how we get there isn’t important. We use different avenues to get to the end result.”

Ms. Combs originally came to the topic when she learned about health dangers from coal-fired power plants while pregnant with her first child. “I was a conservative, pro-family Republican all my life, and I thought, ‘I can’t believe we’re not involved in this.’ ”

Young Republicans, she says, get the issue: They grew up with science education, they grew up recycling, and they aren’t as hampered by entrenched views. A poll that YC4ER commissioned more than a year ago of young conservative voters found overwhelming support for renewable energy, and a clear majority who accept that the climate is changing due to human activity.

Finding the ‘right messengers’

Part of the problem with gaining traction among policymakers and voters, Combs says, has been having liberals always being the ones advocating pushing the issue, making it more partisan than it needs to be.

The issue “needs the right messengers,” says Combs.

Could the younger generation really be the leading edge of a movement to shift thinking on climate policy more broadly within the GOP, the way, say, that generational shifts in opinion helped change the policy landscape on gay marriage?

Some experts are skeptical, pointing to the deep rifts that still exist.

“Either it’s a real cohort effect, and you’re seeing one generation that’s more liberal on the issue, or it’s just a phase, and it will pass as these voters age and become more conservative,” says Dan Kahan, a Yale professor of law and psychology who studies the roots of partisanship.

What Professor Kahan sees as more critical is understanding how some conversations can be productive while others turn people away. Asking “whose side are you on?” instantly causes people to hunker into opposing camps, while focusing instead on solutions, and how we can continue to live the way we want to live, can lead to progress. He sees the biggest source of a potential push for climate action to be people – like those in southeast Florida – with a vested economic stake in the issue.

Similarly, Edward Maibach, director of George Mason University’s Center for Climate Change Communication, says that while he’s somewhat encouraged by the polls showing that conservative Millennials are more concerned about climate change than their parents’ or grandparents’ generation, he’s more encouraged that polls are showing an increase in moderate Republicans’ concern about the issue in the past year.

“I suspect this trend will continue, given that climate impacts in the United States are becoming more obvious all the time, and perhaps this trend will be led by conservative Millennials and Gen-Xers,” says Professor Maibach in an email.

[Editor's note: This article has been changed to correct Emily Collins's major, it is political science.]

Pew Research Center

Into dark cycle of Mideast revenge, this group tries to bring light

Social media can make activism as easy as the click of a mouse. Our reporter accompanied a group whose more demanding mission is to console the victims of Israeli-Palestinian violence in person.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Dina Kraft Correspondent

Gadi Gvaryahu’s group, Tag Meir, was established in 2011 in response to a spate of so-called price tag attacks. Such assaults, which have been on the rise, involve radical Jewish youth attacking Palestinians or their property as declared reprisals for acts against settlers or the settler movement. Today Tag Meir’s mission is to console victims of terrorism, be they Jews or Palestinians. This week members of the group visited Hussein Dawabshe, a Palestinian whose daughter, son-in-law, and grandson were killed in an arson attack in 2015. Days before their visit the grandfather was verbally accosted by Jewish extremists shouting horrific taunts about his dead grandson as he exited an Israeli courthouse. The Tag Meir members, including a rabbi, a settler, and three Arab Israelis were greeted by family members at the Dawabshe home. In an age of social media activism, the Israelis came in person to offer consolation and to take a stand against violence. “If [terrorists] do something bad we do its opposite; we do something that is good,” Mr. Gvaryahu says. “They make darkness. We bring light.”

Into dark cycle of Mideast revenge, this group tries to bring light

Packed into a black minibus heading from Jerusalem into the occupied West Bank, the group of Israelis is on a mission.

They’re on their way to the village of Duma to visit Hussein Dawabshe, a Palestinian whose daughter, son-in-law, and 18-month-old grandson, Ali Saad Dawabshe, were killed in a 2015 arson attack by extremist Jewish settlers. Ali’s older brother, Ahmed, 4 at the time, survived severe burns and is being raised by Hussein Dawabshe and his wife, Satira.

Days before the visit this week, as Mr. Dawabshe exited an Israeli district courthouse in the town of Lod where a hearing had just been held regarding the suspected killers, he was taunted by a group of Jewish extremists who praised his grandson’s murder.

“Where is Ali?” the group chanted. “Ali is dead. Ali is on the grill.”

Gadi Gvaryahu shakes his head, astonished by the cruelty of those words. He’s sitting in front as the minibus leaves Jerusalem’s evening rush-hour traffic and passes checkpoints into the West Bank, where roads are sliced between rocks and terraced hillsides.

Behind him are members of the group he leads, “Tag Meir.” They are doing what they have done hundreds of times before. They are visiting families who have lost loved ones to terrorism – whether the violence was perpetrated by Jews or Palestinians. They come to express their outrage and – in this case – shame at the actions of their fellow Jews.

In an age of social media activism, they come in person to offer their consolation and to take a stand against violence.

“If they do something bad we do its opposite – we do something that is good. They make darkness. We bring light,” Mr. Gvaryahu says.

The organization was established in 2011 in response to a spate of so-called price tag attacks, in which radical Jewish youth, often from settlements, attack Palestinians or their property as declared reprisals for acts against settlers or the settler movement.

Tag Meir is a play on words. “Price tag” in Hebrew is “tag mechir,” while tag meir literally means “light tag.”

“We wanted to give a Jewish Zionist response to the attacks going on,” says Gvaryahu, a Modern Orthodox Jew whose father survived the Holocaust and whose mother’s family settled in Jerusalem in the early 1800s.

Yossi Saidov, spokesman for Tag Meir, says that according to statistics collected by the Shin Bet, Israel’s internal security forces, the number of price tag attacks has soared in the last three months to twice the number in all of 2017.

At least two involved physical violence – two Arab bus drivers stabbed in the Jerusalem area – and there were dozens of attacks on property, he says, including a rise in “agricultural terrorism,” meaning attacks on vineyards and groves of olive and fruit trees. A mosque near Nablus was burned as a “price tag” for the murder of a Jewish Israeli in Jerusalem’s Old City.

A settler joins the group

Tag Meir quickly swelled from a coalition of 20 organizations to about 50 including the kibbutz movement, the Reform and Conservative movements of Judaism, and an Orthodox peace activist group called Oz V’Shalom, for Strength and Peace. Some Jewish settlers are in the group as well.

“So you see, we are not just left-wingers,” says Gvaryahu.

The idea is to respond quickly to an incident, with the group conducting three to four visits a month.

“There have been hundreds of visits,” Gvaryahu says. “It does not matter if they are Jewish or Arab. We go to them.”

On the way to Duma, the mini-bus climbs a steep hill to the nearby Jewish settlement of Shiloh, built near the archeological site that marks the biblical area town that served as the first capital of the Israelites.

Michal Froman, an architect who grew up in Shiloh and now lives in a settlement called Tekoa, climbs on. It was in Tekoa where, pregnant with her fifth child two years ago, she was stabbed by a 15-year-old Palestinian.

The stabbing prompted her activism. She hopes forging a personal connection with Palestinians will help prevent future attacks.

Ms. Froman was outraged by the verbal assault on Dawabshe and decided to join the visit to his home. She admits she has never been deep inside a Palestinian village before. She peers out the window and seems concerned when she hears there will be no army escort.

“How did they dare do that?” she asks of the youths that taunted Dawabshe. “I know some youths who are extreme, but I don’t think even they would dare say such things.”

When she was younger, she offers, she joined with other young settlers protesting Israeli government evacuation orders – both in Gaza and later at a hilltop West Bank settlement called Amona that became a flashpoint. She was even arrested and put in a police car once, she says. “But nothing like that ever came out of my mouth.”

The visit

The Tag Meir members, about 15 in number, including three Arab Israelis who have become active in the group, walk up the stairs of the Dawabshe home and are greeted by family members. A large banner hangs on a wall, emblazoned with the oversized images of the faces of the slain father, Saad, and son. A photo of Hussein Dawabshe’s slain daughter, Riham, holding her two sons is attached to the poster.

The guests have brought soccer-themed gifts for Ahmed in a nod to the World Cup – a soccer ball and a table-top soccer game. Scars from his burns mark the side of his face and the back of his head. He spent a year in an Israeli hospital recovering after the attack.

Now a rowdy and precocious seven-year-old, Ahmed moves like a blur, kicking his new soccer ball in the kitchen, down the hallway. A rabbi who heads a yeshiva and is a member of the group kicks the ball with Ahmed underneath the banner with his family’s faces.

Windows overlook the valley below and the sloping hills that lead toward Jordan. The visitors gather on a circle of couches and chairs and introduce themselves.

Some have met the family before and been in touch since the attack. Tag Meir members prayed with the family at the hospital.

'We are ashamed'

“We have come to visit you now because of what you went through at the courthouse. We are ashamed of those people,” Gvaryahu says.

Dawabshe looks around the room and says, “I say I don’t have hate. And what good would taking revenge do me anyway? But I did tell the court to take its revenge by sending the suspects to jail for the rest of their lives.”

A disagreement briefly breaks out among the guests. Some argue the Jewish settlers must aggressively condemn “price tag” attacks; others contend settlers are already speaking out.

They exchange personal stories. Froman talks about the trial of the teenager who stabbed her. She recounts how she told him she wanted him to move on with his life and not spend it in prison. But he insisted to her in court he did not regret his crime.

Dawabshe appears moved to see them in his home. “I am happy to see them here,” he says, “they are Jews and have come to support me, and that’s a good thing. I wish all Jews were like them.”

Gvaryahu acknowledges how brutally hard change is. But he insists these visits give him and others energy to do more, not less, to bring it about.

“I think if we were not here the situation would be even worse because we go to places where (aside from Israeli soldiers) we are the only Jews these Palestinian children have ever met.”

At dusk there are handshakes and hugs goodbye. And promises by Tag Meir to come to the courthouse for the next hearing to support the Dawabshe family. To shed some light on the darkness.

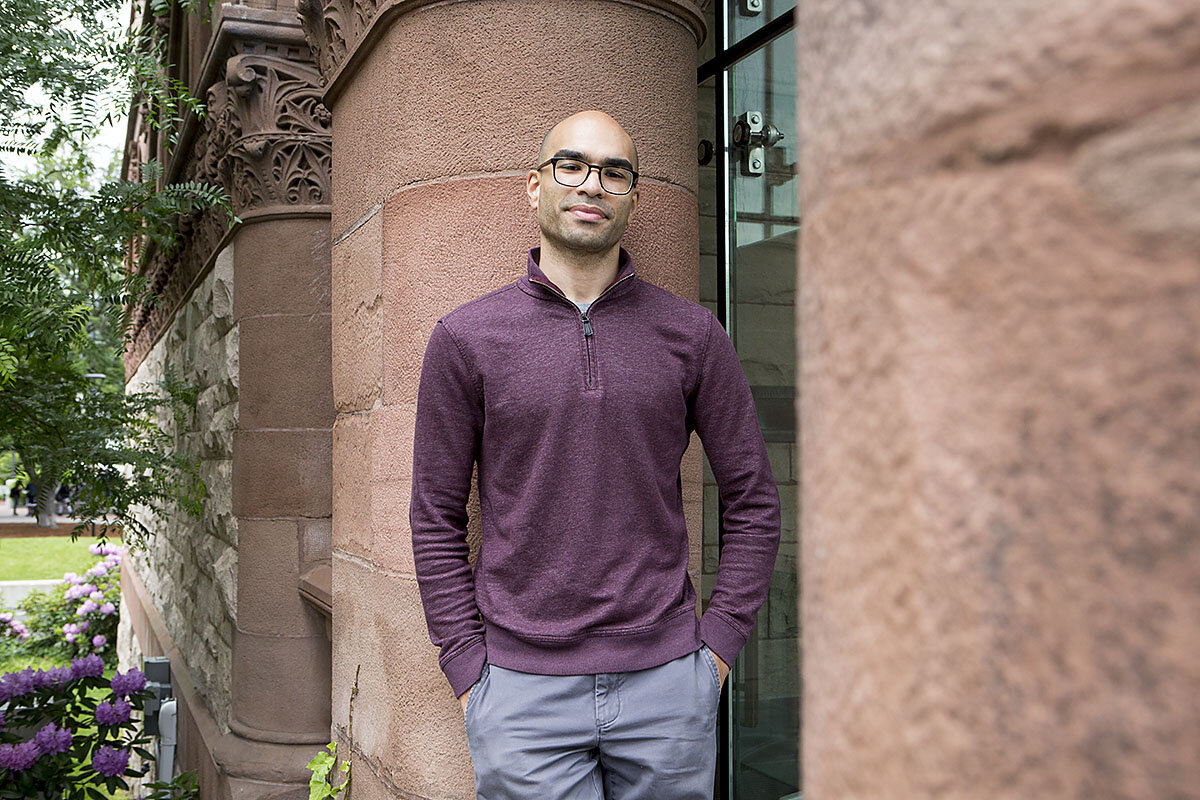

For men of color, a place at the front of the classroom

Role models, particularly those in schools, have a big impact on children. Persistent efforts to recruit and retain men of color are aimed at striking a real-world balance for school staff.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

In Cambridge, Mass., district officials have become more strategic about recruiting teachers of color. Besides looking for candidates outside the state, they are also being more conscious about implicit bias in the recruitment process. A national push for more diversity has been prompted by research conducted since 2015 showing the positive impact that relationships – between students, and teachers who look like them – can have. At a time of racial division in the United States, educators say it is increasingly important for all children to be exposed to role models of different races. More than 8 out of every 10 US teachers are white. And despite a growing population of minority students, the percentage of black teachers has declined over the past three decades. Black male teachers make up only 2 percent of teachers nationwide. In Cambridge, Superintendent Kenneth Salim aims to increase the district’s teachers of color to 30 percent by the fall of 2020. “[T]his is about making sure that our students are successful,” he says. “A diverse educator workforce is one important pillar of that effort.”

For men of color, a place at the front of the classroom

Principal Damon Smith remembers a time when his students at Cambridge Rindge and Latin School in Massachusetts had a black principal, black assistant principal, black mayor, black governor, and black president – all at the same time. But he sees a need for black men to push open the door to the next frontier: the kindergarten classroom.

“We need more practitioners of color, particularly black male teachers, in our classes K-12.” he explains in his office on a recent afternoon. “President Obama is just a step. It shows you what is possible,”

His school district has made teacher diversity a priority in recent years. Ahead of this past school year, Cambridge Public Schools had 89 job openings, 44 percent of which were filled by people of color. For the coming school year, more than 44 percent of new hires for the high school alone will be people of color, according to district officials.

A national push for more diversity among teachers has been prompted in part by research conducted since 2015 showing the positive impact that relationships – between students, and teachers who look like them – can have. At a time of racial division in the United States, educators say it is increasingly important for all children to be exposed to role models of different races.

“We know that teacher diversity has a positive impact not just on children of color, but on all children,” said Cassandra Herring, founder and chief executive officer of the Branch Alliance for Educator Diversity, speaking to reporters in Los Angeles during a recent panel discussion on the subject. “Early interactions with other people helps to dismantle racism… [Teacher diversity] is an academic imperative but it’s also a moral imperative.”

More than 8 out of every 10 US teachers are white and the percentage of black teachers has declined over the past three decades, despite a growing population of minority students. Black men make up only 2 percent of teachers nationwide.

To address this, a combination of grassroots and district-level programs have formed across the US in recent years to help recruit – and keep – black men in education.

In 2015, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio launched NYC Men Teach, aimed at helping 1,000 men of color to become classroom teachers within three years. NYC Men Teach has surpassed its goal, bringing 646 male teachers of color into the district and adding 759 to the “pipeline” of those poised to enter the profession within the next two years. This past school year, 11 percent of new teacher hires were men of color – an increase from 8 percent at the launch of the program.

The same year in Philadelphia, a group of black male teachers formed an organization called The Fellowship, which hopes to have 1,000 black male educators in Philadelphia schools by 2025. Co-founder and CEO Vincent Cobb says the group has already made “significant progress,” with 100 to 150 interested applicants showing up each year at a job fair sponsored by The Fellowship.

These join older efforts such as Clemson University’s Call Me MISTER program, which started in 2000 to encourage more black men to enter and stay in teaching by providing support groups and tuition assistance. Call Me MISTER has since spread to 21 colleges and universities in South Carolina and at least five other southern states.

A way to stem dropouts

Teacher diversity makes economic sense, says Nick Papageorge, an economist at John Hopkins University in Baltimore, Md. Having at least one black teacher in elementary school reduces a black student’s probability of dropping out by 29 percent, and among low-income black males, having at least one black teacher reduced their dropout rate by 39 percent, Dr. Papageorge found in research published last year.

“Having a bunch of high school dropouts because they didn't have a black teacher? That seems so wasteful,” says Papageorge. “Show me an economic model where wasted potential is better.”

Currently, only 12 percent of education majors are black. And once they enter the profession, minority teachers leave teaching at higher rates than their white peers.

Black teachers quit, observers say, because of discrimination by peers, isolation, and frustration with the US education system. Black and Hispanic teachers are disproportionately employed in low-income schools with a majority of students of color, a 2016 Department of Education study found.

Much of the recruitment struggle is circular, says Papageorge. To really change teaching’s demographics, almost every black person who graduates from college would need to enter education. This is unrealistic as well as undesirable – it would take black graduates away from other professions where diversity is also needed. The long-term solution, he says, is to have more black college graduates – but that means more black high school graduates, and a major barrier to higher graduation rates is the absence of black teachers.

Manuel Fernandez, the head of school at Cambridge Street Upper School, will be celebrating 40 years in education this fall. The absence of black teachers from his own education has fueled his life’s work, which Mr. Fernandez sees as an extension of what he wishes he had had as a child.

“If I don't see people who look like me, I get messages that say, ‘I'm not to be an educator. I am not going to be a physicist. Those are not for me,’ ” says Fernandez. “We have to open up the opportunities for children in very distinct ways… have people who look like them say, ‘You can do this, because I did it.’ ”

Needed: morale boosts

Principal Smith says he entered teaching because he wanted to support young men marginalized by the education system, but at the same time he resents expectations, both stated and unstated, that black male teachers’ can “control” black young men.

“There is an opportunity because of shared experience, histories, and neighborhoods…. But that doesn’t mean that by virtue of being ‘the black principal’ that all of the black boys will all suddenly fall in line,” says Smith. “That is too heavy of a responsibility and it releases everybody else from having to do the work that needs to be done.”

Black male teachers say talking about teaching together improves their morale. Christopher Godfrey is a teacher in the all-black, all-male math department at Cambridge’s Putnam Avenue Upper School. He says it has recharged him as a teacher.

“Being able to see myself reflected in my work... I can’t put into words what that has done for me,” says Mr. Godfrey. “It’s the coolest thing to be around.”

Congress and the US Supreme Court have gradually narrowed the tools available to improve teacher diversity, says Catherine Lhamon, chair of the US Commission on Civil Rights. Supreme Court decisions on affirmative action over the last five decades have weakened “the lawful use of race” to create any remedy, she notes. And education funding cuts by Congress and local governments often result in teacher layoffs, which typically cut the last teachers hired – many of them teachers of color.

“It’s an issue of equity,” says Ms. Lhamon. “We need to retain a focus on the issue and how much it matters for student learning.”

Forging ahead in Cambridge

In Cambridge, Superintendent Kenneth Salim aims to increase the district’s teachers of color to 30 percent by the fall of 2020.

“[T]his is about making sure that our students are successful,” he says. “A diverse educator workforce is one important pillar of that effort.”

At present in Cambridge Public Schools, 24 percent of teachers – compared to almost 60 percent of the student body – are people of color. It’s a dramatic mismatch, yet still enough to make the district second in the state for staff diversity and is six percentage points higher than the national average.

“Our goal of 30 percent feels challenging, particularly challenging given that we know that less than 30 percent of New England graduates from teacher training programs are teachers of color,” says Ramon De Jesus, CPS’ program manager for diversity development, who was hired this past October to help the district reach its hiring goal. “But we can’t hide behind that when our students are asking us, ‘Do more’ and we have not exhausted all the possibilities.”

Mr. De Jesus says the city has become more strategic by looking for candidates from outside Massachusetts. Dr. Salim and De Jesus also say they have taken a hard look at implicit bias in their recruitment process. Looking for preconceived notions of “rigor” and “good schools” on resumes may exclude qualified candidates of color – and job descriptions with long lists of requirements might dissuade them from applying in the first place.

Last month, a diverse group of educators met for the first time in Cambridge as part of the district’s new Employee Resource Groups. The gathering, meant to promote discussion about race among teachers, is one of the steps CPS is taking to help retain its teachers of color.

Smith, the principal, is optimistic about the district being a leader in teacher diversity moving forward.

“You come back here in four or five years,” he says with a nod. “It’s going to be a lovely thing.”

Correction: This story has been updated to clarify the nature of the employee meetings provided by Cambridge Public Schools.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

How to use Justice Kennedy’s legacy in choosing his replacement

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

As it prepares to battle over Supreme Court nominees, Congress could take a lesson from the main judicial legacy of retiring Justice Anthony Kennedy: dignity. In many of the court’s biggest decisions, he was the swing vote. But he wanted to go beyond merely finding a middle ground. He sought to interpret the Constitution in ways that could ensure that the inner conscience of individuals and their outward responsibilities were not in conflict. Governance to him was not a zero-sum choice between the demands of the left and the right but rather a search to define what he called the “transcendent” attributes and the “spiritual imperatives” necessary for a complex world. He relied on the principles of liberty, privacy, and universal equality. He mixed all three to emphasize the intrinsic value of dignity. Such thinking was usually evident in his most important rulings, such as those on campaign finance, same-sex marriage, religious exercise, and the rights of detainees at Guantánamo Bay. Dignity was his lodestar. Perhaps it can also be the starting point for the coming national discussion over his replacement.

How to use Justice Kennedy’s legacy in choosing his replacement

One legacy that Justice Anthony Kennedy leaves as he retires after three decades on the US Supreme Court is some principled guidance on how to hold a dignified debate over choosing his successor. As members of the Senate arm themselves for a battle royal over President Trump’s nomination, they may want to build on, rather than ignore, his judicial legacy.

When he wrote the court’s official opinions, Justice Kennedy often sought a path for many of those who lost their legal case to see their views expressed in policy. This went far beyond his strong defense of free speech. Governance to him was not a zero-sum choice between the demands of the left and the right but rather a search to define what he called “transcendent” attributes and the “spiritual imperatives” necessary for a complex world.

Before Elena Kagan joined the high court as a justice, she described Kennedy as its most influential member because of his “independence, his integrity, his unique and evolving vision.” In many of the court’s biggest decisions, he was the swing vote, and for good reason. He sought to interpret the Constitution in ways that could ensure that the inner conscience of individuals and their outward responsibilities were not in conflict.

To achieve that, he relied heavily on the basic principles of liberty, privacy, and universal equality, then mixed all three to emphasize the intrinsic value of dignity.

In Kennedy’s focus on dignity – either to preserve it or bestow it – he saw the makings of social cohesion and healing. Or as he put it in a talk, “Most people know in their innermost being that they have dignity and that this imposes upon others the duty of respect.”

Such thinking was usually evident, if not always accepted, in his most important rulings, such as those on campaign finance, same-sex marriage, religious exercise, and the rights of detainees at Guantánamo Bay. In many cases, he saw the best course to ensure the continuance of dignity was to set boundaries on government power. In others, he saw such power as necessary to end any harm to dignity.

Dignity is not something defined from the outside. Each individual is endowed with it. Guarding it in the way Kennedy did can help engender respect for the dignity of others.

Dignity is not a source for division but, if recognized, can be the basis for what Kennedy calls the best interpretation of the “mandates and promises” of the Constitution. “I am searching, as I think many judges are, for the correct balance in constitutional interpretation,” Kennedy stated.

Dignity was his lodestar. And perhaps it can also be the starting point for the coming national discussion over his replacement.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The real scale of happiness

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Wendy Margolese

Today’s contributor found that seeking a more spiritual sense of her identity freed her from an unhealthy focus on her diet and weight.

The real scale of happiness

As a young teen, I did not think much about body image until my friend gifted me a diet book. Then I followed its advice, including notating everything I ate, as though it were sacred. However, this approach set me off on a roller coaster ride of happy and sad days, dictated by the bathroom scale.

This “scale of happiness” dogged my days for many years. One day, I realized I wished to be free of having my sense of happiness and self-worth dictated by my weight or food consumption. At this time, I was becoming a sincere student of Christian Science, so I turned to the Bible and the writings of Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, for inspiration to help improve the way I was thinking about food and my self-image.

One story in the Bible particularly resonated with me: that of Daniel, who was held captive by a Babylonian king, Nebuchadnezzar (see Daniel, chap. 1). The king wanted to specially feed and educate a few chosen captives so they might be fitted to serve him in his court.

Daniel, however, did not want to follow the decreed diet of wine and meat, perhaps thinking that the food had been consecrated to Babylonian gods. He asked for a very simple and somewhat sparse diet for himself and his companions, and this was granted provided they could prove, after ten days, that they looked as healthy as those who had been eating the king’s fare. According to the Bible story, at the end of the allotted time Daniel and his companions appeared “fairer and fatter in flesh than all the children which did eat the portion of the king’s meat” (1:15).

This story sparked a thought: Why didn’t the food seem to dictate the physical appearance of Daniel and his friends? I realized that Daniel was very close to God. He also acknowledged God as the source of wisdom and might (see Daniel 2:20). This inspired me to see that, like Daniel, my true identity and sense of self-worth came from a spiritual source: God. I began to see that it had nothing to do with what I ate or what I saw in the mirror. I saw that I needed a new conception of my being. Echoing an idea I had appreciated in Mrs. Eddy’s “Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” I realized I too could say, “I will gain a balance on the side of good, my true being” (p. 104).

I understood this true being to be the reflection of God, because the Bible’s first book, Genesis, says that God made man (each of us, male and female) in His “image” and “likeness.” The Bible also says that God is Spirit, and so the teachings of Christian Science conclude that each of us, as God’s image, is truly spiritual. Understanding this has a healing impact on our experiences.

As I considered these ideas, the impact of this understanding was enabling me to see that I was not subject to material forces and fads, and this lifted a great weight off my thought. I found that I no longer needed to stand on the scale each morning, as I had discovered that the real “scale of happiness” has nothing to do with a matter-based emotion. It comes from realizing the truth of our being as God’s deeply loved offspring and expressing spiritual qualities such as goodness and joy in our activities.

I began to lose the weighty thought that my worth had anything to do with how I looked physically. It wasn’t that I stopped caring about how I looked. Rather, the idea of the spiritual completeness, beauty, and joy of God’s creation, and my freedom to express such qualities, gained more weight in my thinking. As this mental shift took place, I found I was expressing more of those qualities in my life, and a sense of balance in my weight and food consumption came naturally. I became less focused on what I ate and one day realized another outcome had naturally resulted: I’d been opting for more appropriately sized portions.

Understanding more of our true nature as God’s beloved child, cared for in every way, lifts the burdensome sense that we are limited mortals subject to variables. Then we see and feel more of God’s love and goodness in our lives.

A message of love

Displaced by fighting

A look ahead

Join us tomorrow, when we'll have a report from Lexington, Va., home of the Red Hen restaurant, where locals talk about how the debate on civility has had a dramatic effect on their lives this week.