- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- After Helsinki, can US hope to quell Russian mischief?

- No more Hershey's? Canadians get behind 'patriot's guide' to shopping

- Overturning Roe may be simple; what comes after won't be

- A Sumatran fishing town's message to Rohingya: You are welcome

- From Russia with hashtags? How bots dilute online speech

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Monitor Daily Intro for July 18, 2018

Today’s issue includes a familiar byline: Sara Miller Llana. Her dateline over the past five years has typically been Paris. Or Berlin. Or Amsterdam, Athens, Bilbao, Budapest, Copenhagen, Kiev, Moscow, Reykjavik, Rome, Stockholm, Warsaw, or … you get the idea.

Today, it’s Halton Hills, Ontario, and she is filing as the Monitor’s new Canada bureau chief.

To all of us at the Monitor, it’s an exciting time. “On both sides of the Atlantic, people frequently tell me ‘we are in strange times,’ ” Sara says. “Toronto is the perfect place from which to plumb that sentiment, because Canada is adhering to the international order, while the United States, under the Trump administration, seems to be suggesting a new direction.”

While Sara is moving to a new geographical base, her focus will be less on physical location than on new ways of thinking about long-standing issues: a nation defining itself as a "post-nationalist state" based on “shared values”; what it means to be “us,” with implications across North America and Europe; land and energy issues; consensus-building amid immigration challenges and concerns about democratic institutions; and trade initiatives.

Sara served as Latin American bureau chief before reporting from Europe. Fluent in French and Spanish, she covers the news with rigor and heart. She and her husband and young daughter are liking the Toronto vibe so far. “I was on a crowded, hot streetcar that people were trying to exit. Instead of yelling at the driver who had shut the doors, it was a polite, 'Could you open the door? I'm trying to get out.’ It just set a tone that changed the mood for all.”

Now to our five stories, showing how the consequences of certain actions are hard to anticipate, and the power of generosity.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

After Helsinki, can US hope to quell Russian mischief?

President Trump's remarks in Helsinki created a political firestorm. But they also offered clues to the future of US-Russia relations.

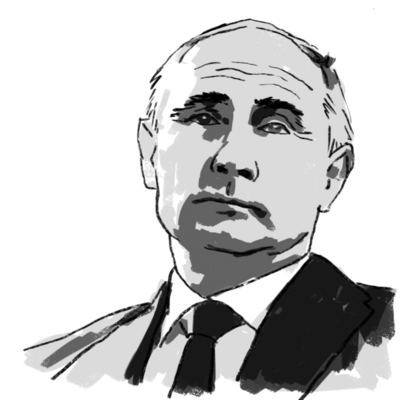

At their summit in Helsinki, Finland, Monday, President Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin displayed considerably more entente than discord. That, along with signals Mr. Trump sent previously at the NATO summit in Brussels, would seem to quell recent fears that a new cold war between the world powers was in the offing. But, say US-Russia experts, neither is a sudden golden era in bilateral relations, and the domestic storm over Trump’s remarks is a strong indication. Trump’s own top aides continue to speak of Russia in very different terms from those of the president – referring to Mr. Putin’s Russia as an “adversary” responsible for considerable “malign activity.” Nikolas Gvosdev at the US Naval War College says, “you have a US president who evidently is not interested in the things producing conflict with Russia.” The risk now, he says, is that Russia will feel emboldened to move further along its interventionist path. Trump’s record from his Europe trip “will suggest to … the Kremlin that being more aggressive pays off, and that they are in a position to realize some gains.”

After Helsinki, can US hope to quell Russian mischief?

Remember when a sudden burst of Russian intervention from Ukraine to Syria, efforts to undermine Western democracies, and above all, Moscow’s chosen role as chief global opponent of the US-led liberal international order, all spurred predictions of an impending second cold war?

You can forget about it.

After President Trump’s Helsinki summit with Russian President Vladimir Putin Monday – and especially given the displays at the two leaders’ extraordinary press conference of considerably more entente than discord – the heralds of an extended period of cold-war-like tensions and confrontation between the two powers have quieted.

No one is predicting a sudden golden era in US-Russia relations. Indeed quite the opposite is likely: The domestic reaction in the United States to Mr. Trump’s performance at the two leaders’ press conference suggests any Trump initiative to improve rock-bottom relations with Russia is a non-starter, US-Russia experts say.

That is true in part because in the US, Congress has a role to play in how the relationship evolves, particularly in determining the fate of US sanctions on Russia over its hybrid war in Ukraine. At the same time, Trump’s own top aides continue to speak of Russia in very different terms from those of the president – referring to Mr. Putin’s Russia as an “adversary” responsible for considerable “malign activity.”

But the signals Trump sent out over the past week – not just in Helsinki with Putin, but at the preceding summit with NATO alliance leaders in Brussels – suggest to a number of US-Russia experts that the “Cold War II” envisioned so widely beginning in 2014 won’t occur after all.

“A cold war requires by definition two sides to confront each other,” says Nikolas Gvosdev, a professor of national security affairs and US-Russia expert at the US Naval War College in Newport, R.I. “But if you have a US president who evidently is not interested in the things producing conflict with Russia – if the president is less interested in maintaining the Western alliances the US has built, in sustaining US leadership of a certain world order, or in the US position in the Middle East – that suggests something to the Russians about the confrontation and the determination of the other side to pursue it.”

An emboldened Russia

The risk Professor Gvosdev sees in a relationship he envisions remaining “stuck” in inactivity – with the US unable now to pursue initiatives with Russia that would serve its own interests – is that Russia will feel emboldened to move further along its interventionist path.

Trump’s stance in Europe over the past week – culminating in his “performance” alongside Putin at the Helsinki press conference and the firestorm it has caused at home – “will suggest to Russians in the Kremlin that being more aggressive pays off, and that they are in a position to realize some gains,” Gvosdev says. “The risk is they will say, ‘What else can we get out of this situation?’ and will be tempted to try for additional geopolitical payoffs, in Europe or the Middle East.”

Of course the big change since the widespread predictions of a second cold war is not in Putin, but in the White House arrival of Trump. The president’s positions on a list of issues that led to the back-to-the-future prognostications suggest no interest in confrontation.

On Syria, Trump shows every sign of deferring to Russia as it completes its project of reestablishing Bashar al-Assad’s hold over the country – even as he displays little appetite for pressuring Russia to “rein in Iranian activity in Syria,” Gvosdev says.

Although Trump has ultimately gone along with his own administration’s proposals on Ukraine and has ramped up measures to counter Russian incursions – for example providing some lethal weaponry to Ukraine’s military – he has also suggested an understanding of Russia’s actions in its western neighbor, particularly in Crimea.

And Trump has shown scant interest in countering Russian attacks on Western democracies, such as its disinformation campaigns and efforts to meddle in the 2016 US presidential election.

Trump did attempt Tuesday to backtrack on his Helsinki statements that suggested once again that he believes Putin’s “very strong” argument that there was no Russian project to influence the 2016 election. But after seeming Tuesday to accept the US intelligence consensus of Russian meddling, on Wednesday he asserted that such activities had stopped, again putting him at odds with his own top advisers (the White House press secretary subsequently tried to walk his latest remarks back). And the overall impression left by Trump’s week in Europe is that he sides more with a Russian authoritarian leader than with US allies in European democracies.

Supporters of the president’s foreign policy say Trump’s actions in Helsinki confirm his stance since he was a candidate that “Peace with Russia is a good thing, not a bad thing,” as former presidential candidate Pat Buchanan wrote on his website Monday. If the Trump-Putin press conference gave the traditional foreign-policy community palpitations, Mr. Buchanan added, it’s because Trump demonstrated that he is not going to allow Russian activities in Ukraine or Syria get in the way of the US pursuing common interests with Russia, such as in arms reductions.

“Looking back over the week, from Brussels to Britain to Helsinki, Trump’s message has been clear, consistent, and startling,” Buchanan said. “There will be no ‘Cold War II.’”

'Peculiar dualism' on Russia

That may be, but neither is Trump going to find an easy path to that “peace” with Russia – particularly after demonstrating so little ability or desire to stand up to Putin’s provocations, analysts say.

“When we look back on it, Helsinki will be seen as a major turning point for this president, and for US relations with the rest of the world,” Gvosdev says, adding that Trump lacked credibility and cemented perceptions of his relationship with Putin, “[killing] off any prospect of improving US-Russia relations.”

One high hurdle standing in the way of any presidential efforts to pursue better relations with Russia will be the wall of opposition constructed by Trump’s own senior national security advisers.

Highlighting what he calls a “peculiar dualism” in the Trump administration’s approach to Russia – the stark disconnect between the president’s and the rest of the administration’s positions – Anthony Cordesman of Washington’s Center for Strategic and International Studies says the dualism raises serious questions about the US strategy towards Russia.

The president’s own National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy are both much tougher toward Russia than the president’s rhetoric, Mr. Cordesman says. For example, the December 2017 National Security Strategy states that “Russia aims to weaken US influence in the world and divide us from our allies and partners.”

At the NATO summit, both Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and US NATO Ambassador Kay Bailey Hutchison insisted that Trump administration policy would focus on countering Russian “malign activity” in Europe, the Middle East, and across a broad swath of US allies globally.

Weakened global leadership

Analysts note that at the Helsinki press conference, Putin made a point of saying he did indeed want Trump to win the 2016 election. Whether done with this intention or not, they add, the Russian president’s public insertion of himself into US political affairs will be another factor in assuring that Russia remains a source of political turmoil in the US – and that US-Russia relations remain unproductive, perhaps as long as Trump is president.

“The issue is not whether the Russians interfered [in our political process] – they did,” says Matthew Rojansky, director of the Wilson Center’s Kennan Institute in Washington. “The issue is whether we are now capable of doing two things simultaneously, namely pushing back against future Russian meddling, and engaging effectively with Russia on a wide array of critical issues. Our current domestic politics still makes that kind of carefully calibrated diplomacy all but impossible.”

For Gvosdev, it’s not going too far to say that the long-term effect of Helsinki – and Trump’s week in Europe more broadly – will be to weaken US global leadership and to send US allies turning elsewhere for partnerships.

“The message not just the Europeans but the Japanese and Israelis and others will take from Trump’s whole trip – and from the uproar that’s followed here at home – is that it’s time to choose a new partner, and maybe Russia is the more stable of the two now,” Gvosdev says.

Noting that French President Emmanuel Macron met with Putin on the sidelines of the World Cup, and that Iranian leaders were recently in Russia seeing Putin – as was Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu earlier this month – Gvosdev says such meetings reflect enhanced Russian clout, and fading trust in US leadership.

“The postwar and cold war perspective that the American president speaks on behalf of US alliances around the world was already weakening,” he says, “but after the last week the sentiment will be even stronger that it’s no longer the case.”

•Staff writer Linda Feldmann contributed from Washington.

Share this article

Link copied.

No more Hershey's? Canadians get behind 'patriot's guide' to shopping

Amid the consternation over US tariffs in Europe and Asia, Americans may be missing what's happening just north of their border. Canadians are protesting with their wallets.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

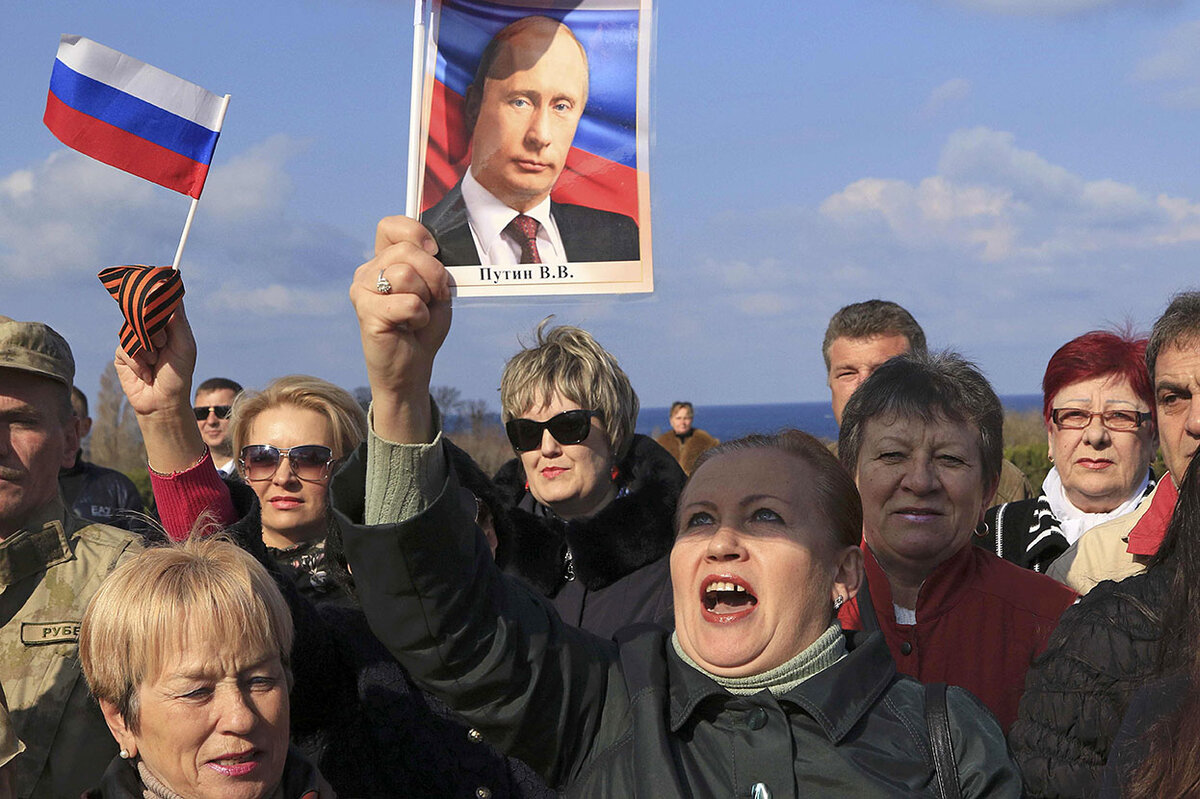

Canada and the United States are arguably the two closest countries in the world, and their relationship has thrived because it is based on local connections and the work at hand. The practical work and trade gets done because politics and personalities don’t get in the way. But amid a trade spat and threats of tariffs on automobiles, peppered with a slew of perceived affronts from President Trump, suddenly Canadians feel they are getting picked on. A #BuyCanadian movement has become their pushback. One Canadian publication published “A Patriot’s Guide to Shopping During a Canada-US Trade War,” with such suggestions as forgoing Hershey factory products and opting for Canadian chocolate brand Laura Secord. The union Unifor launched its own boycott campaign. Canadians have shared stories about canceling vacations in New York in favor of visits to Prince Edward Island. And relations have soured enough that some aren't sure when they might rebound. “Things have just gone so sideways,” says Rick Bonnette, mayor of Halton Hills, Ontario. “I hope at the end of the day that common sense prevails, that we go back to being the good trading partners we always were.”

No more Hershey's? Canadians get behind 'patriot's guide' to shopping

Mayor Rick Bonnette boasts that his municipality outside Toronto is the most patriotic in all of Canada: on the country’s 150th birthday last year, a population of 61,000 raised approximately 57,000 Canadian flags.

So when President Trump slapped aluminum and steel tariffs on his country – on the grounds of national security, no less – Mr. Bonnette helped draw up a resolution that passed unanimously by the town council. It encourages Halton Hills residents to “become knowledgeable” about what they buy and consider “avoiding the purchase of US products” when possible.

“We don’t want to escalate this,” Bonnette says in his sleepy town hall office of the local boycott. “But we are not going to be pushed. This has gotten insulting.”

It is a rare flare-up of passions north of the border that is born not just of antipathy towards American foreign policy, which itself would be nothing new, but something altogether more personal. Amid a trade spat and threats of tariffs on automobiles, peppered by a slew of affronts by President Trump, suddenly Canadians who might have seen the United States as a bully elsewhere in the world now feel they are the kid getting picked on. A #BuyCanadian movement has become their pushback.

Canadians are certainly not alone, as Trump has lambasted allies in recent weeks from Germany to Britain, while seeming to cozy up to America’s traditional foes as he did in Helsinki with Russia’s Vladimir Putin this week. But a growing rift threatens the relationship between arguably the two closest countries in the world. And that relationship has worked precisely because it has long been based on local connections and the task at hand – politics and personalities don’t get in the way.

“A lot of the cooperation that goes on between Canada and the United States is functional,” says Robert Wolfe, professor emeritus at Queen’s University. “It is not because we love each other. It is because we share a continent.”

“Can that survive a sustained period of political turbulence at the top? I don’t know. We’ve never had sustained turbulence at the top, so we don’t know what would happen.”

A significant wedge

Canada and the US have taken divergent paths as far back as the American Revolution. In the modern era, disputes over softwood lumber or lobsters, over the Vietnam and Iraq Wars, have strained the relationship. But differences have always been managed quietly, and kept narrow, in favor of constructive cooperation.

Much of that has been achieved by delegating responsibilities to commissions and creating pacts, whether on water quality of the Great Lakes or airspace control under the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), says Christopher Sands, director of the Center for Canadian Studies at Johns Hopkins University in Washington.

“When Trump leaves the scene, the relationship will need some healing,” he says. “We’ll have to have a decision about whether we want to continue to use institutions to take politics out of the relationship on a day-to-day basis, or whether the answer is going to be reinforcing our national sovereignties.”

A divergence under Trump was to be expected. One survey ahead of the American election in 2016 showed 80 percent of Canadians saying they would vote for Hillary Clinton if they could.

But the frontal attacks coming from Washington on trade have driven a significant wedge. Then Trump abandoned the niceties that have long marked the public relationship between both nations’ leaders after he called Prime Minister Justin Trudeau “weak” and “dishonest” leaving the Group of Seven Summit in Charlevoix, Quebec, last month. The spat comes as the US, Canada, and Mexico are in talks to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

Canadian leadership always has to strike a careful balance, between not caving to American interests but maintaining privileged access to Washington. But even in a polarized country with 2019 elections looming, Canadians across the spectrum rallied around $12.6 billion in retaliatory tariffs, announced by Trudeau’s government, giving the Liberal leader a welcome bump in the polls. According to a survey by Abacus Data in June, only 19 percent of Canadians oppose counter-tariffs.

One Canadian publication published “A Patriot’s Guide to Shopping During a Canada-US Trade War,” with such suggestions as forgoing Hershey factory products and opting for Canadian chocolate brand Laura Secord, named after a heroine of the War of 1812 who warned British troops of an impending American attack. The union Unifor launched its own boycott campaign. Canadians have shared stories about canceling vacations in New York or the American West for Prince Edward Island or the Canadian Rockies.

'This is not a game'

At a Metro supermarket in Halton Hills, Maureen Sowden says she no longer will buy toilet paper made in the US and has done her research about where her products come from – or at least as much as possible in such an integrated market. She says this “locally sourced” movement is a good consciousness-raising exercise, even if it’s hardly an economic threat to the US.

“We are so close, it is as if everything just becomes part of the Americas, but we are distinct,” she says, “and we are becoming more and more distinct.”

That is a sentiment that has increasingly come to the fore.

The economic trade between the countries totaled $673.9 billion last year, with a US surplus of $8.4 billion. Canada is much more dependent on what it sells to the US than vice versa. Diversification, whether with China or the European Union, is shaped by that reality. “It is impossible to see a world for Canada in which the United States is not the predominant relationship,” says Drew Fagan, a professor of public policy at the University of Toronto.

Yet he notes a growing divide between the US and Canada since 9/11, both physically on the border and in terms of a values gap, after decades of a trend towards deeper integration.

Mayor Bonnette has felt the divide too. He first took a public stand in 2009, criticizing “Buy American” policies implemented under former President Barack Obama.

But the Trump era has changed basic assumptions that could threaten the long-term relationship, Bonnette says. “Things have just gone so sideways,” he says. “There’s a lot of theories that the president has ramped this up for the midterms, and if that’s the case I hope at the end of the day that common sense prevails, that we go back to being the good trading partners we always were.”

“But this is not a game. And anyone who lost a job over this is going to feel resentful for a long time.”

Overturning Roe may be simple; what comes after won't be

The possibility of overturning Roe v. Wade is real. But the consequences of that may not be as obvious as many think.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

If the Supreme Court gains another conservative justice this fall, analysts expect it may overturn – or substantially weaken – the landmark Roe v. Wade decision, sending abortion policy back to the states to hash out. Reproductive rights advocates are already preparing for that outcome. Even with Roe in place, more than 400 abortion restrictions have been passed at the state level, and many states would likely see an uptick in those restrictions. But legislating – particularly on a controversial issue like abortion – is rarely a straightforward process. While four states have “trigger laws” in place that would automatically ban abortion as soon as Roe is overturned, most would need lawmakers to introduce and vote on new bills. Some analysts say, when push comes to shove, legislators may not relish codifying their rhetorical positions into concrete laws. Previously, “state legislatures could duck this controversial social issue and say … ‘The Supreme Court has taken it out of my hands,’ ” says Dwight Duncan, a law professor at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. “If Roe v. Wade was undone, the issue is back in their ballpark and they no longer have that excuse.”

Overturning Roe may be simple; what comes after won't be

With the US Supreme Court poised to slide further to the political right if President Trump’s nominee is confirmed, the end of the Roe v. Wade era suddenly seems a very real possibility.

Roe, the 1973 ruling that legalized abortion in the US, has been at the heart of a heated culture war that’s split the nation largely along partisan lines. Almost as soon as the decision was made, antiabortion activists began working toward a high court roster that would reverse the ruling. Judge Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation, if it goes through in the fall, would give them their most conservative – and most promising – lineup in decades.

But if Roe is overturned, what then? Would America be flung back into an age of back alleys – or forward into a “Handmaid’s Tale” dystopia – as some abortion-rights advocates fear?

If the Supreme Court does overturn Roe – or substantially weakens it, which is what many experts are predicting will happen – it would send abortion policy back to state legislatures to hash out. Already, even with Roe in place, more than 400 abortion restrictions have been passed at the state level over the past half-decade. Without Roe, some states would likely see an uptick in those restrictions, resulting in a wider gap between states in terms of access to safe, legal abortions, policy experts say. Reproductive rights advocates are already calling for “all hands on deck” in preparing for the worst.

But legislating – particularly when it comes to a controversial issue like abortion – is rarely a straightforward or simple process. While four states have “trigger laws” in place that would automatically ban abortion as soon as Roe is overturned, many others would need lawmakers to introduce and vote on new abortion bills and update their existing statutes. Some legal analysts say that when push comes to shove, legislators, especially in swing states or in states with divided government, may not relish having to codify their rhetorical positions into concrete laws and regulations.

“Up until now... state legislatures could duck this controversial social issue and say – to whomever they’re talking to, whether they’re pro-choice or pro-life – ‘I agree with you, but there’s nothing I can do about it because the Supreme Court has taken it out of my hands,’ ” says Dwight Duncan, a professor at the University of Massachusetts School of Law in Dartmouth. “If Roe v. Wade was undone, the issue is back in their ballpark and they no longer have that excuse.”

“The politics change,” he says.

Not only will state representatives be forced to tackle the myriad and complex details of abortion policy, but they’ll likely be doing it with advocates on both sides rallying voters around the issue.

Some say that’s a good thing. Policies set by the legislative branch, as opposed to the judiciary, tend to be perceived as more legitimate because they reflect the will of the people. “We’re a democratic republic, and ‘we the people’ ultimately should be the rulers. To the extent that it’s unelected people in robes deciding these questions, ‘we the people’ are essentially left out of this,” Professor Duncan says.

It could also scramble the nation’s political divide in unexpected ways. The fulfillment of such a long-held conservative goal – overturning Roe – could potentially deprive the Republican Party of what for decades has been a top motivating issue for many of its voters. “Anti-Roe sentiment is a combination of two things: a sincere hostility to abortion and sexual freedom... combined with the argument that this [ruling] is rammed down the public’s throats by unelected life-tenured lawyers,” says Eric J. Segall, a professor at Georgia State University College of Law in Atlanta who wrote a book on the Supreme Court. “The second [argument] goes away once Roe gets overturned.”

Others suspect that a reversal on Roe could spur a fierce reaction from liberals that would mirror the rise of Christian conservatives as a political powerhouse after 1973. “That could be the kind of energizing force needed to create a backlash on the left, thus energizing the Democratic Party,” says Mark Kende, director of the Drake Constitutional Law Center in Des Moines, Iowa.

Still, without the Supreme Court protecting a woman’s right to decide whether or not to have an abortion, reproductive rights activists worry that many states will reverse what they see as decades of progress – especially for women in poor and rural communities. Already, since 2011, 33 states have enacted a total of 420 policies restricting abortion, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive rights research group.

“What we’ve seen in the past eight years has been devastating to abortion rights,” says Elizabeth Nash, a policy analyst for the Washington-based nonprofit. “Without those [Supreme Court] protections, those restrictions will proliferate.”

Yet even then, analysts say, it’s unlikely America would see a reversion to the worst of the pre-Roe era in terms of a rise in unsafe alternatives. Medical abortions, which take the form of pills, offer an option beyond what was available to women in the ‘50s and ‘60s – though of course, no one wants to encourage women to resort to illegal means. “That’s a shabby use of law to say, ‘Well you can also get an illegal pill,’ ” says Carol Sanger, a professor at Columbia Law School in New York.

Women today also have more political power, which means that any abortion restrictions that surface after a reversal on Roe would likely face more challenges. (While certainly not all women are pro-abortion rights, they have been the main drivers of the reproductive rights movement.)

And whatever abortion restrictions may be passed after Roe is overturned “may not be the final word,” says Professor Sanger, who also wrote the book, “About Abortion: Terminating Pregnancy in Twenty-First-Century America.” Given enough opposition, laws can be lobbied against and repealed. “I can imagine someone introducing a bill saying, ‘This law doesn’t work. We haven’t thought it through enough,’ ” she says.

“We’re going to see some really interesting politics going on,” Sanger adds. “It’s much harder to take a right away than instill a new one.”

A Sumatran fishing town's message to Rohingya: You are welcome

The Rohingya’s plight has generated few lasting solutions. In a world where sanctuary for refugees is growing scarcer, it’s notable when host communities continue to welcome them in.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Michael Holtz Staff writer

Bireuen, Indonesia, isn’t the place Nur Hakim risked his life to reach. But it’s certainly better than what the 15-year-old left behind in Myanmar. Nur and his family are Rohingya, a Muslim minority in the majority-Buddhist country; last fall, the United Nations high commissioner for human rights condemned their persecution as “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing.” After soldiers burned Nur’s village, his family was forced into a camp for the displaced, leaving him unable to attend school or leave for work. Hundreds of thousands of Rohingya have fled for Bangladesh, but tens of thousands more, like Nur, set sail for Malaysia. Thai Navy ships intercepted his boat, however, and when the 79 men, women, and children were eventually guided ashore by fishermen, they were in Indonesia. More than 1,740 have landed in Aceh province, where some Indonesians say their faith prompts them to welcome the newcomers. But the refugees say this is a temporary respite as they wait for authorities to decide their fate. “The people here have beautiful hearts,” Nur says. “I’m not sure how much longer I’ll stay here, but at least for now I know that I’m safe.”

A Sumatran fishing town's message to Rohingya: You are welcome

The plan was to go to Malaysia. That’s where 15-year-old Nur Hakim had hoped to reunite with his older brother, who fled Myanmar years ago and has since found work in construction.

Nur might have made it there if it weren’t for the two Thai Navy ships that intercepted the wooden boat he shared with 78 fellow Rohingya refugees. Instead, the Navy escorted the boat toward the Indonesian island of Sumatra. On April 20, after nine days at sea, it was guided ashore by fishermen and docked at Bireuen, a small fishing town in Aceh province.

The town was quick to welcome the refugees. Those who needed medical care were taken to a nearby hospital, and a government training center was turned into a temporary shelter. Volunteers soon arrived to cook meals, give haircuts, and teach Indonesian. A local imam stopped by during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan to offer his prayers.

At a time when the West is growing increasingly hostile to refugees, Bireuen residents have taken the opposite tack. Local officials and aid workers — with support from the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the United Nations refugee agency — have pledged to look after the new arrivals for as long as necessary.

“We know what they went through in Myanmar,” says Mr. Saburuddin, a worker with the Indonesian Red Cross Society, who like many Indonesians, uses only one name. “If not us, who else will take care of them?”

Nearly three months after their arrival, the 79 Rohingya men, women, and children are still waiting for Indonesian and international authorities to decide their fate. They are happy to have found refuge, but they know that the most Bireuen can offer is a temporary respite from the uncertainty of their lives as citizens of nowhere.

“The people here have beautiful hearts,” Nur says one morning after eating a breakfast of steamed white rice and fried noodles. “I’m not sure how much longer I’ll stay here, but at least for now I know that I’m safe.”

Search for someplace better

Nur is grateful for his new life in Bireuen, however short his stay may be. Although it isn’t the destination for which he risked death on the high seas, he readily admits it’s far better than the place he left behind.

The Rohingya, a Muslim minority, have faced intense persecution in Myanmar, a majority-Buddhist nation, for decades. Despite origins in the country’s Rakhine state, they’re considered outsiders and deprived of many civil rights and economic opportunities. The UN’s high commissioner for human rights condemned an especially violent period last year as “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing,” and possibly even genocide.

For the past six years, Nur and his family were forced to live in an internally displaced persons camp after Burmese soldiers burned their home village. His cousin was shot and killed during the attack. Nur was unable to attend school in the camp or go outside to find work. After tensions flared up again last August, his parents pushed him to leave.

“We have no freedom in Myanmar,” says Mohammad Rofik, the captain of the boat that carried Nur to Bireuen. “If we stayed there, we would die.”

The number of refugees from Myanmar — the majority of whom are Rohingya — more than doubled from less than half a million at the start of 2017 to 1.2 million by the end of the year, according to the UN refugee agency. Most of them now live in overcrowded camps in Bangladesh, but more than 100,000 have packed onto rickety vessels in attempts to cross the Bay of Bengal and Andaman Sea. Hundreds have died along the way.

Many boats set sail for Malaysia, where tens of thousands of Rohingya have found work as undocumented laborers. But to get there they must pass the isthmus of Thailand. Though once complicit in the region’s multimillion dollar smuggling trade, Thai officials started to crack down after mass graves that held the remains of Rohingya migrants were discovered in 2015. This year, three Rohingya boats were reportedly pushed away from the Thai coast.

In early April, Malaysia authorities intercepted the first boat and took ashore the 56 Rohingya on board. A few days later, off the coast of Aceh, Indonesian fishermen rescued five Rohingya left on the second boat. (Two people reportedly died during the 20-day journey, and eight others jumped overboard in search of land, according to the IOM.) Then came Mr. Rofik’s boat on April 20.

“We were expecting more this year,” says Mariam Khokhar, the head of the IOM office in Medan, a city 250 miles south of Bireuen. “We were worried about the perilous journey they would take, but so far we haven’t heard of anyone making it out again.”

'Brothers and sisters'

This year isn’t the first time Aceh has welcomed Rohingya refugees. The IOM reports that more than 1,740 have landed in the province over the past decade.

In 2015, a wooden boat crammed with nearly 800 Rohingya was towed to the city of Langsa. Fishermen also rescued a smaller boat carrying 47 others about 15 miles south of Langsa that year. Local authorities provided shelter for the refugees in two small warehouses.

The shelter in Bireuen consists of about a half dozen single-story concrete buildings and a small mosque. Two of the buildings are being used as separate dormitories for men and women. Another one serves as a logistics center. Inside are sacks of rice and stacks of boxes filled with everything from instant noodles and cooking oil to disposable diapers and toothpaste — much of it donated by local residents.

Several local volunteers point to their shared Muslim identity by way of explaining why they have been so hospitable. Aceh is the only province to have formally established sharia law in Indonesia, a Muslim-majority nation with a relatively secular government.

“They are our Muslim brothers and sisters,” says Muhammed Hussein, a volunteer cook at the camp. “It’s our duty to look after them.”

But Mr. Zulfikar, a local official in charge of the camp, maintains that religion has nothing to do with it. Sitting at a table inside the logistics center, he invokes the law of the seas that requires passing boats to try to save a vessel in distress.

“I don’t care if they’re Muslim or not,” he says. “When you see someone who needs help at sea, you don’t ask them about their background first. You just help them.”

Ms. Khokhar says Achenese authorities plan to soon move the refugees 150 miles south to a more permanent shelter in Langsa. Yet few want to stay in Indonesia. Of the five that arrived on April 6, four have already fled. Khokhar says that they likely crossed the Strait of Malacca to Malaysia, where they can more easily blend in with the Rohingya who live and work there.

Malaysia is still where Nur would like to go in the short term. In preparation, he’s been practicing Indonesian, which is closely related to Malay, with aid workers at the camp. He’s also been studying English in the hopes of fulfilling an even bigger dream.

“I want to go to America,” Nur says. “I heard from my uncle there that people in America are happy.”

From Russia with hashtags? How bots dilute online speech

Hashtags have become the digital scaffolding around which social movements coalesce. The emergence of “decoy” hashtags threatens to dilute this newest method of activist organization.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

“On the Internet,” reads a well-known New Yorker cartoon published in 1993, “nobody knows you’re a dog.” While this notion of anonymity may seem quaint in the age of surveillance capitalism, it’s not quite so easy these days to tell humans from autonomous software agents, some of which are programmed to sabotage our political discourse. A group that monitors the top 600 pro-Kremlin Twitter accounts – many of which are automated accounts that post nearly 24 hours a day – found that a version of the hashtag #FamiliesBelongTogether with a subtle typo was the third most-tweeted hashtag on a weekend when thousands took to the streets to march against President Trump’s immigration policies. By diverting attention and propagating “noise” around the “signal” of actual online conversations, the bots apparently aimed to Balkanize the discourse to prevent it from gaining traction. “This is becoming more like a mind game,” says Onur Varol, a postdoctoral researcher at Northeastern University’s Network Science Institute.

From Russia with hashtags? How bots dilute online speech

If you search Twitter for the hashtag #FamiliesBelongTogether, a tag created by activists opposing the forcible separation of migrant children from their parents, you might be in for a pop proofreading quiz.

That’s because, in some locations in the United States, the top trending term, the one that Twitter automatically predicts as you type it, contains a small typo, like #FamiliesBelongTogther.

The misspelled hashtag, and others like it, have enjoyed unusual popularity on the social platform. Tweeters who have unwittingly posted versions include two senators and one congresswoman, the American Civil Liberties Union, MoveOn, and the actress Rose McGowan.

This is not an accident, say data scientists, but the result of a deliberate, automated misinformation campaign. The misspelled hashtags are decoys, aimed at diffusing the reach of the original by breaking the conversation into smaller groups. These decoys can dilute certain voices and distort public perception of beliefs and values.

“This is becoming more like a mind game,” says Onur Varol, a postdoctoral researcher at Northeastern University’s Network Science Institute. “If they can reach a good amount of activity, they are changing the conversation from one hashtag to another.”

In the past decade, hashtags have played a central role in grassroots political communication. Many of the movements that have shifted public perceptions of how society operates – the Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street, Black Lives Matter, MeToo – gained early momentum via Twitter hashtags.

The #FamiliesBelongTogether decoys were likely propagated by automated accounts linked to Russia. As social media consultant Tim Chambers pointed out earlier this month, the Hamilton 68 dashboard, a tool that monitors the top 600 pro-Kremlin Twitter accounts, found that the decoy hashtag #FamilesBelongTogether was the third most-tweeted hashtag on June 30 and July 1, the weekend that thousands took to the streets to march against the president’s immigration policies.

By continually posting misspelled versions of the hashtag 24 hours a day, these automated accounts train Twitter’s search algorithms to see the misspelled versions as trending topics. The aim may be to create something of a spoiler effect, fragmenting the movement into subpopulations, each too small to gain traction.

By themselves, the decoy hashtags will do little to divide immigration activists, says Kris Shaffer, a researcher at New Knowledge, a cybersecurity firm that tracks how disinformation spreads online. “Sometimes what they’re doing is essentially digital reconnaissance,” he says, “like trying to figure out what techniques work and what the effects of the techniques are.”

Dr. Shaffer says that he has seen campaigns like this before. In 2014 following the arrests of several police and government officials for the kidnapping and murder of 43 Mexican college students, the hashtag #YaMeCanse or “I am tired” became an online hub for protests.

But it wasn’t long before top search results for #YaMeCanse on Twitter became populated with tweets including the hashtag but no other meaningful content. Pro-government accounts were flooding the channels with automated posts, drowning the signal with noise.

Digital Potemkins

In 1787, after Russia annexed Crimea for what would be the first of many times, Catherine the Great toured her newly acquired territory. According to legend, the region’s governor, Prince Grigory Potemkin, sought to make the peninsula appear more prosperous than it actually was by constructing portable facades of settlements, which were disassembled and reassembled along Catherine’s route.

In the modern era, Potemkin villages are built out of code. Social bots, accounts that automatically can post content, like posts, follow and unfollow users, and send direct messages, don’t just promote bad hashtags, they can also greatly distort our perceptions of what beliefs and values are and are not popular.

“People tend to believe content with large numbers of retweets and shares,” says Dr. Varol. “This is unconsciously happening.”

A 2017 study led by Varol found that between 9 percent and 15 percent of all accounts on Twitter, up to 48 million accounts, may be bots.

The social media giant stepped up its war against false bandwagons last week, when it purged tens of millions of automated or idle accounts from its platform, reducing the user bases’ collective follower count by about 6 percent.

“I believe the situation is much better right now,” says Varol. “Twitter is taking proactive behavior.”

Others are calling for more regulation of automated accounts. In the California Assembly, a version of Senate Bill 1001, which would make it illegal for bots to mislead humans as to who they really are, has left the Senate floor and is being taken up by the Committee on Appropriations. If passed, such a law could have ripple effects beyond California.

But until bots are required to identify themselves, or social platforms eradicate them, humans will have to remain on the lookout for their influence. ”Slow down. Think carefully. Don’t retweet from your bed,” says Shaffer. “That can help.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

South Africa revives a Mandela legacy

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

All this year, South Africa is using the centennial of Nelson Mandela’s birthday to take stock of his legacy. It may also be trying to restore some of that legacy. Under a new president, the government hinted it might reverse a controversial decision in 2016 to withdraw from the International Criminal Court, a body set up to seek justice for victims of the world’s mass atrocities. Such a move was in sharp contrast to Mandela’s declaration in 1994 – when he became South Africa’s first president elected in a multiracial election – that “human rights will be the light that guides our foreign policy.” He fully supported the creation of the ICC. The new mood in South Africa is reflected in its invitation for former President Barack Obama to deliver the main lecture during the Mandela centennial. “He came to embody the universal aspirations of dispossessed people all around the world, their hopes for a better life, the possibility of a moral transformation in the conduct of human affairs,” Mr. Obama said. In setting up the court, the United Nations affirmed the idea that individual lives have a higher value than national sovereignty and that all nations must be held accountable to rule of law. Its mere presence is a threat to dictators and a deterrent to state-led violence. What better way to honor Mandela than to stay true to his call to focus on human rights.

South Africa revives a Mandela legacy

All this year, South Africa is using the centennial of Nelson Mandela’s birthday to take stock of his legacy.

It may also be trying to restore some of it.

Under a new president, Cyril Ramaphosa, the government hinted earlier this month that it might reverse a controversial decision in 2016 to withdraw from the International Criminal Court, a body set up just 20 years ago to seek justice for victims of the world’s mass atrocities. In 2015, South Africa even defied the court by failing to arrest one of the ICC’s most wanted suspects, Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, during a visit.

Such moves were in sharp contrast to Mandela’s declaration in 1994, when he became South Africa’s president elected in is first multiracial election, that “human rights will be the light that guides our foreign policy.”

During his time in office, Mandela tried hard to end conflicts in Africa and boost democracy. He supported the the ICC on July 17, 1998. His successors, however, have often sided with dictators or ignored large-scale violence on the continent. President Ramaphosa, who came to power this year on an anti-corruption wave within the ruling African National Congress, appears to be focusing again on human rights.

A few other African nations had also threatened to leave the ICC, largely because most of the court’s early cases were focused on African leaders. Only Burundi has fully withdrawn. South Africa’s effort to exit was stymied by its own courts. Now the government intends to drop its objection to the ICC altogether.

The new mood in South Africa is reflected in its invitation for Barack Obama to deliver the main lecture during the Mandela centennial. In a talk July 18, the former US president noted how much Mandela’s values influenced his career as well as the lives of millions. “He came to embody the universal aspirations of dispossessed people all around the world, their hopes for a better life, the possibility of a moral transformation in the conduct of human affairs,” Mr. Obama said.

The creation of the ICC was based on a notion that when countries allow genocide or crimes against humanity within their borders, then an outside court must seek justice under the principle of universal jurisdiction. In setting up the court, the United Nations affirmed the idea that individual lives have a higher value than national sovereignty and that all nations must be held accountable to rule of law when mass atrocities occur.

The ICC enjoys wide support among Africans, according to one poll, even if it has achieved only a handful of convictions. Of the court’s 123 member states, 33 are African. Its mere presence is a threat to dictators and a deterrent to state-led violence.

That is why countries such as South Africa, which has an outsized influence in Africa, must continue to support the court. And what better way to honor Mandela than to stay true to his call for the country to focus on human rights.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Angels that keep us safe

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Joan Bernard Bradley

Today’s contributor shares how a new way of thinking about angels has brought her comfort and calm even during troubling situations.

Angels that keep us safe

For many years, traveling between countries was a big part of my life; I live on the North American mainland and my parents lived in the Caribbean, so I traveled frequently to visit them. When I was a new student of Christian Science, a member of the church I’d begun attending took an interest in my travels and often engaged me in conversations about them. At one point she lovingly asked me if preparations for my trips included prayers for safety. When I said they did not, she reminded me of the many examples in the Bible of people who relied successfully on God to keep them safe.

Deeply moved by this woman’s love and care for my welfare, I began to study some Bible stories with safety in mind. In particular, the story of Moses stood out. The great Hebrew leader defied a pharaoh’s powerful army by leading the people who had been enslaved in Egypt to freedom. He did this by relying entirely on God’s guidance and protecting care.

I especially loved this verse from later in the story, when the group was making its way through the wilderness: “Behold, I send an Angel before thee, to keep thee in the way, and to bring thee into the place which I have prepared” (Exodus 23:20). This message must have reassured Moses and conveyed the idea that God’s loving presence was a wise and intelligent force for good that he could rely on to help the Israelites on their journey.

This got me thinking about the idea of angels and soon I found an enlightening definition of angels in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” by Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy. It reads: “God’s thoughts passing to man; spiritual intuitions, pure and perfect; the inspiration of goodness, purity, and immortality, counteracting all evil, sensuality, and mortality” (p. 581).

For me, this radically different concept of angels was meaningful and practical. Christian Science explains that another name for God is Mind, and this divine Mind provides each one of us with inspiration that protects and heals us. When we are open to this inspiration, we are welcoming angel thoughts that guide and protect us; so I made the commitment to regularly listen for the spiritual intuitions God was imparting.

I had learned in the Bible that we are the image and likeness of God, who is divine Spirit, so I reasoned that we all have an equal ability to hear God’s thoughts. And I found that listening actively for those angels from God throughout my day enabled me to enjoy more of the peace and harmony that God’s loving presence brings.

One time I was visiting my parents in their home, which was located in a relatively undeveloped section of the community. Because of problems with burglary in the community, they had installed an alarm system. The system was designed to be triggered if there was any significant movement within two feet of the house. Occasionally a small animal would trigger the alarm, but one night it was being repeatedly triggered, which was very unusual. We understood that this was a technique sometimes used to lure people to come out of the house.

This was frightening, and we began to pray. My prayers acknowledged that inspiration from God was coming to each of us, bringing comfort and calm, and was even bringing to any potential intruder the desire to do what’s right. God’s, divine Love’s, influence is present for, and embracing, everyone; therefore we were all safe in Love’s care. Any invasion of our sense of peace or good is not from God, and therefore has no legitimate basis or power. These ideas helped us feel secure and cared for that night, even before the triggers finally stopped. We thanked God, and after that night there were no further incidents of that sort.

While we don’t actually know that the alarms represented real danger that night, the experience taught me that actively acknowledging God as ever-present good calms our thoughts and enables us to feel the assurance of God’s presence and help (see, for instance, Isaiah 41:10) – and that this can result in safety. This inspiration operates like a spiritual law of peace and harmony in consciousness, and we can listen for and experience it even in frightening or uncertain situations.

A message of love

Honoring sacrifice

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, we'll talk to veterans, a group that has served and sacrificed for their country, about their views on the Trump-Putin summit in Helsinki. I hope you'll join us.