- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Amid warnings of Idlib massacre, a last try at diplomacy in Syria

- Beyond Alex Jones: Twitter and Facebook face heat over alleged bias

- Despite signs of trouble, GOP says it has road map for November wins

- Supreme Court hearings are broken, both parties say. How they can be fixed.

- For West, Myanmar leader’s fall from grace muddies response to a crisis

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Climate change as a tipper of global elections

For decades the forces of green have shown up in democratic nations’ elections, advancing environmental causes from the fringe and nudging mainstream party agendas with varied degrees of success.

Today, in tight races, major parties’ stances on confronting climate change may increasingly decide elections.

This Sunday, Swedes march to the polls in what some are calling the first European national election in which climate is a key voter issue. Yes, immigration feels most immediate, but the Arctic has been scorching hot. A party dismissing that as “one summer” of hot weather – as one party is – risks its broader credibility with a growing slice of the electorate.

A climate-tipped poll wouldn’t be a global first. In Australia’s election in 2007, held amid prolonged drought, a Labor government rode to power at least partly on the strength of its pledge to sign onto the 10-year-old Kyoto Protocol.

It will almost certainly not be the last. In the United States, one major poll shows 62 percent of Americans think that Washington is doing too little to protect the environment (a 12-year high). A climate-opinion map from Yale University depicts remarkably strong feelings about the issue.

“Bubbling beneath the battle for control of Congress during this year’s election cycle,” writes Amy Harder in Axios, “is a series of consequential energy and climate fights.”

Now to our five stories for your Friday, including a close look at some high-stakes diplomacy on Syria, at charges of political bias in the realm of social media, and at a better way of running Supreme Court confirmation hearings.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Amid warnings of Idlib massacre, a last try at diplomacy in Syria

Throughout Syria's civil war, outside powers have tried and failed to prevent horrific violence. With Syria poised to take Idlib province, likely at great cost, diplomats are meeting again. Is it too late?

-

Scott Peterson Staff writer

For the past 18 months, as resurgent Russia- and Iran-backed regime forces swept across Syria, defeated and disarmed rebels in stronghold after stronghold were allowed to flee to northwestern Idlib province. They took their families and many of their anti-Assad sympathizers, and Idlib’s population swelled from 1.5 million to 3 million. Now a final military reckoning seems imminent for Syria’s seven-year civil war, with forces loyal to President Bashar al-Assad poised to attack Idlib. The Russian and Syrian air forces have already begun to bomb. On Friday, at United Nations headquarters in New York, and in a Turkey-Iran-Russia summit in Tehran, warnings of a looming massacre were sounded. But it may be too late for diplomacy, which has routinely failed to prevent atrocities throughout the war. “The dangers are profound that any battle for Idlib could be, would be a horrific and bloody battle,” warned UN Syria mediator Staffan de Mistura. “Either we are trying to find a political way to end this war and move to a postwar political scenario, or we will see this war reach new levels of horrors.”

Amid warnings of Idlib massacre, a last try at diplomacy in Syria

The possibility that Syria's Idlib province would provide the setting for a tragic coda to the humanitarian catastrophe of the country’s seven-year civil war seemed enhanced Friday after a last-ditch summit meeting in Tehran of the main outside powers.

Even as Turkey, long a bitter foe of President Bashar al-Assad, urged a cease-fire in the northwestern Syrian province and warned of a massacre, Russia and Iran, Mr. Assad’s two main backers, pressed for government forces to begin their assault on the last refuge of rebel forces in the country.

Fresh Russian and Syrian airstrikes on Idlib were reported Friday morning. The widely anticipated offensive has drawn international concern.

At United Nations headquarters in New York, the Security Council met to discuss Idlib Friday at the request of the United States. UN Syria mediator Staffan de Mistura said there were “all the ingredients for a perfect storm,” Reuters reported.

“The dangers are profound that any battle for Idlib could be, would be, a horrific and bloody battle,” Mr. de Mistura said. “Either we are trying to find a political way to end this war and move to a postwar political scenario, or we will see this war reach new levels of horrors,” the Associated Press quoted him as saying.

Idlib’s fall to the Assad regime would effectively signal the end of a civil war that has already killed nearly half a million people, devastated the country, and forced half its population to flee their homes.

The humanitarian impact has been staggering. Millions have fled to neighboring countries and hundreds of thousands to Europe and beyond, feeding an epic refugee crisis that has strained humanitarian agencies to the breaking point.

How Idlib became a target

Over the past 18 months, backed by the manpower and firepower of Russia and Iran, the regime has had a string of battlefield successes, seizing the northern city of Aleppo, Deir ez Zour in the east, the Eastern Ghouta region east of Damascus, and most recently, Deraa and Quneitra provinces in the south.

In each battle, the regime offered rebels the option of surrendering their heavy weapons and relocating to Idlib province, where Turkish troops man observation posts as part of a now-collapsed de-escalation zone deal. The influx of defeated fighters and their families to the Idlib dumping ground saw the local population nearly double from 1.5 million to almost 3 million.

The dilemma facing the rebels and Sunni jihadist militants is that there are few places left to flee to should the Assad regime attack.

While Russia has condemned Idlib as a “nest of terrorists” that needs to be cleansed and brought back under central government control, Turkey has been calling for “terrorists” – a reference mainly to the Al Qaeda-linked Harakat Tahrir ash-Shams (HTS) – to be separated from civilians, in order to avoid an all-out onslaught.

“The [Syrian-Russian-Iranian] plan was clear from the start. These [rebel] groups would go there and then the regime would attack to capture it,” Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu told reporters this week. “How many of them will come to Turkey? Maybe 2 million [civilians]? Maybe more. Where will these terrorists go? They might come to Turkey or go back to their own countries. Foreign terrorist fighters can also go to other countries, to Europe or even beyond.”

Turkish media estimate that 60,000 Sunni jihadists are in Idlib, some 15,000 of them non-Arab foreign fighters. They remain “the biggest number of [Islamic State] and Al Qaeda-affiliated terrorists in Syria,” wrote columnist Murat Yetkın in the Hürriyet Daily News on Wednesday.

"Russia’s message is clear,” argues Mr. Yetkın. "President Vladimir Putin does not want to lose time letting terrorist elements in Idlib embed with the civilian population, spread violence elsewhere, and use civilians as human shelters against possible attacks, while also not caring much about the possible collateral damage.”

No good options for Turkey

The stance of Turkey, which mans 12 observation posts on the edges of the Idlib enclave, is critical to determining its fate, analysts say.

“At one extreme, Turkey can choose to defend Idlib militarily, directly and/or through its proxies,” says Faysal Itani, resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East. “If they do so, the regime cannot take the area at an acceptable cost, and Idlib becomes a de-facto Turkish zone.”

At the other extreme, Mr. Itani says, Turkey could abandon its observation posts in Idlib, effectively ceding the region to the Syrian government, though he says some rebels would likely withdraw to other Turkish-held territory, while the jihadists “may well choose to stand and fight.”

So much was at stake Friday afternoon when Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, Russian President Vladimir Putin, and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan gathered in Tehran.

Aslı Aydıntaşbaş, a Turkey expert at the European Council on Foreign Relations, warned that the three leaders, despite handshakes and smiles, would “neither have the same vision for Syria nor be on the same page about the impending battle of Idlib.”

Mr. Erdoğan has long viewed Assad as illegitimate, wrote Ms. Aydıntaşbaş, in an ECFR analysis published Thursday, so “despite a begrudging acceptance of the regime’s wartime gains over the past two years, Ankara is in no mood to facilitate Assad’s victory in Idlib.”

None of Turkey’s options look good, adds Aydıntaşbaş, as it faces both a humanitarian “catastrophe” and a result that could “forever alter the dynamics of the Syrian war – in favor of the regime.”

Itani says he had trouble imagining what a cease-fire would look like.

“Russian contacts and persons close to the [Syrian] regime tell me that the difficulty of taking Idlib is exaggerated. They only real disincentive is a military conflict with Turkey, but even that may not be enough.”

Should US expand warning?

The United States, meanwhile, has remained on the sidelines of the impending assault on Idlib, although the White House has warned that the US and its allies would respond “swiftly and vigorously” if the regime uses chemical weapons.

The US has some 2,000 special forces troops deployed mainly in eastern Syria alongside the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces, and is primarily focused on ensuring the defeat of the ruthless Islamic State group and the full withdrawal of all Iranian and Iranian-led forces from Syria.

“I am very sure that we have very, very good grounds to be making these warnings,” Jim Jeffrey, the Trump administration’s newly appointed adviser on Syria, told reporters Thursday. “There is lots of evidence that chemical weapons are being prepared.”

In April last year, the US struck a Syrian air base with cruise missiles in response to a chemical attack three days earlier, attributed to the Assad regime, on Khan Shaykhun. At least 74 people died.

“If the regime uses CW [chemical weapons] – which it has throughout the war – then the US will likely strike Assad regime targets,” says Andrew Tabler, a Syria expert at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

However, some analysts maintain that Washington’s warnings to Assad over the use of chemical weapons against civilians should extend to conventional arms as well.

“My fear is that past will be prologue with the Trump administration,” says Frederic C. Hof, diplomat in residence at Bard College in New York and State Department special adviser on Syria during the Obama administration. “By issuing a very public warning to Assad to avoid chemical warfare, the administration signals – intentionally or not – that mass civilian homicide by more conventional means will likely draw no US response.”

Mr. Hof says the only way to counter the “thoroughly unintended consequences” of such public messaging would be to warn Russia privately that “Assad’s business as usual – state terror – could draw a kinetic American response irrespective of the murder weapons.”

“I am not aware of such a message being passed,” he adds.

Beyond Alex Jones: Twitter and Facebook face heat over alleged bias

Conservative complaints of biased social media giants have reached a crescendo. That made us ask: Are Twitter and Facebook faltering on the task of balancing free speech with transparent standards of responsible discourse?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When radio host Alex Jones was permanently banned from Twitter Thursday, the news generated headlines. But the "InfoWars" host, a conservative provocateur who once called the Newtown, Conn., school shooting a hoax, is just one topic in a broader debate that has escalated in recent days. President Trump said Google’s algorithm is biased against conservatives. In congressional hearings Wednesday, Republican lawmakers raised similar allegations that Facebook or Twitter have suppressed political speech, including from commentators far less incendiary than Mr. Jones. Many scholars who study the industry say they don’t see overt political bias. Rather, they say the companies face a learning curve, in balancing free speech with some oversight in an era of cyberbullying, misinformation campaigns, and offensive diatribes. One big problem is that the companies are relying heavily on technology to make human judgments about context and appropriateness. Another problem is lack of transparency. Communications expert Victor Pickard says, “How these algorithms are designed and operated by social media platforms remains largely hidden from the public.”

Beyond Alex Jones: Twitter and Facebook face heat over alleged bias

Two weeks ago, conservative commentator David Harris Jr. took a video of himself posting to Facebook. Why video something so common? Because he had a hunch what would happen.

Sure enough, his post went through, but a photo of a letter that accompanied the post mysteriously vanished and did not show up in his feed until days later – proof, he said, that the sharing service was biased against conservatives.

At a Wednesday House committee meeting, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey was barraged with examples from Republican congressmen of how conservative voices were being suppressed on its service. On the same day, the US Department of Justice announced that Attorney General Jeff Sessions would meet with state attorneys general to discuss concerns tech companies "may be hurting competition and intentionally stifling the free exchange of ideas on their platforms."

All that didn’t stop Twitter, on Thursday, from permanently banning conspiracy-monger Alex Jones – following curbs on him by other social-media networks, and after Mr. Jones sought to confront Mr. Dorsey and others outside the Capitol Hill hearing.

In a remarkable turnaround from two years ago, when conservatives hailed social media as a key factor in President Trump’s election victory, many now claim that Twitter, Facebook, Google, and others are shutting them out. On the left, lawmakers are worried about the cyberbullying of private individuals on social media – a concern echoed by first lady Melania Trump.

The immediate result is increasing and bipartisan pressure for social media platforms to be more transparent about their algorithms and how they block certain content. Longer-term, the threat is more regulation of the platforms, something that even free-market conservatives are reluctantly talking about doing if social media doesn’t clean up its act.

Are social media companies politically biased? They say they’re not. And many scholars who study them agree.

“It’s a false narrative that conservatives are bearing the brunt of some kind of campaign against them,” Ari Waldman, director of the Innovation Center for Law and Technology at New York Law School, writes in an email. “Platforms also mistakenly ban pictures of women breastfeeding. They also ban civil rights activists who post photos in order to protest police brutality. They also ban drag queens…. Content moderation is simply a difficult business.”

Lack of transparency?

One big problem is that the companies are relying heavily on technology to make human judgments about context and appropriateness. Another complicating factor is that social media’s clampdown on fake news and accounts used by Russia to meddle with US elections has caused the companies to more strictly enforce their standards on domestic users as well. A third problem is that the companies have done a poor job of making clear what’s acceptable and not acceptable on their sites.

“How these algorithms are designed and operated by social media platforms remains largely hidden from the public,” Victor Pickard, a communications professor at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, writes in an email. “Within the vacuum of this lack of transparency, any number of conspiracy theories can emerge with a degree of plausibility.”

Nevertheless, the grievances of conservatives keep piling up, even among those who are far less controversial than Mr. Jones of Infowars. Last fall, US Rep. Marsha Blackburn (R) of Tennessee wanted to run an ad for her Senate bid that said she opposed “the sale of baby body parts” (fetal-tissue research). Twitter deemed that “inflammatory” and “likely to evoke a strong negative reaction,” so wouldn’t run the content as a paid ad. She was able to tweet out the ad, however.

Last month, Twitter and Facebook initially rejected an ad from California House candidate Elizabeth Heng, which showed footage of the Cambodian genocide her parents escaped. Both services reversed that decision a few days later.

In July, liberal-leaning digital site and media broadcaster Vice News found that three conservative House members – Mark Meadows of North Carolina, Jim Jordan of Ohio, and Matt Gaetz of Florida – were among prominent Republicans not showing up in the drop-down menus in Twitter searches. Although they could still be found in full search results, the lack of drop-down mentions meant it would be slower and less convenient to find them, a practice known as “shadow banning” that liberal Democrats were not experiencing. The day after the story appeared, the problem stopped, the news site reported.

It’s not just public figures who face shadow-banning. Two months ago, Maine motel owner Miles Ranger started noticing changes with his Facebook political account, Maine for Trump 2020. Posts and shares from his conservative friends dropped precipitously. Some of his posts and shares were deleted immediately without explanation, as were pictures. Followers saw some of his posts only five to six days later.

The people who post conservative material are not monolithic, he says in an e-mail. There are “bots” – computer programs that automatically post material. “More significant though are the disguised FB [Facebook] pages with real people behind them but they don’t use their real name or real personal pics of themselves,” he writes. “They are nasty, provocative, mostly ignorant and mostly FALSE. These people are on both the right and the left.”

There are others posting who are real and caught up in conspiracy theories. And then there are conservatives like him, Mr. Ranger says. “I have real friend and family – but I’ve learned to not talk politics at class reunions or family reunions – so these things are minimized” on his personal Facebook site. “The political posts stay on political groups,” such as his Maine for Trump site, he adds.

'Why does she only get the liberal suggestions?’

At a Senate Intelligence committee hearing Wednesday morning, Twitter’s Dorsey and Facebook’s chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg repeatedly denied that their companies were trying to tip the scales for or against any party or political ideology. But the pileup of anecdotal evidence clearly has exasperated conservative lawmakers.

In a separate hearing Wednesday, of the House Energy and Commerce Committee, Rep. Jeff Duncan (R) of South Carolina told Dorsey of a test Twitter account a twenty-something conservative staffer set up, identifying herself only with an email address and a phone number with a 202 area code. She received suggestions to follow Democratic politicians, pundits, former officials, and journalists Jim Acosta of CNN and Chuck Todd of NBC. “It’s one thing not to promote conservatives, even though Donald Trump is truly the most successful Twitter user…. Why does she only get the liberal suggestions?” he asked Dorsey. “That shows bias, sir.”

“We do have a lot more work to do,” Dorsey acknowledged.

Another area of concern for conservatives is the lack of visibility of these sites in the news feeds from Google News. President Trump last week warned in a tweet that “Google & others are suppressing voices of Conservatives and hiding information and news that is good.”

Studies of Google News have found that liberals and conservatives get almost exactly the same stories in their news feeds. But those are mainly articles from traditional media, such as The New York Times, the Washington Post, and others that many conservatives call left-leaning and biased. Google’s rationale for using them is that they are reputable, large, and well-established, says Efrat Nechushtai, a PhD candidate at Columbia University and lead author of a study on Google News, via email. [Editor's note: The description of Ms. Nechushtai was altered to clarify her status and role as lead author of the study.]

“It is defensible for Google News to offer a news landscape that is based on professional and reputable sources,” she says. Still, she notes that Google News could highlight local organizations or small organizations that present alternative viewpoints from both left and right.

Monitor Breakfast

Despite signs of trouble, GOP says it has road map for November wins

In this next piece, a discussion with the House Republican in charge of keeping his party in control reveals the GOP’s strategy for holding on to the majority. Spoiler: More than ever, it comes down to turning out the base.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Political observers say the path to a Republican victory in the House in the fall midterm elections is narrow, though not impossible. It may be an uphill battle, but Rep. Steve Stivers (R) of Ohio feels “pretty good” about his party’s ability to hold the majority, he told reporters at a Monitor Breakfast on Friday. As chair of the National Republican Congressional Committee, he’s charged with winning the House for the GOP. And as a brigadier general for the Ohio Army National Guard, of course he’s got a battle plan – one aimed at overcoming significant political hurdles. Working against Republicans are the president’s lackluster approval ratings, a “generic” House ballot that favors Democrats, a surge of Republican retirements, and a historic trend of losses for the president’s party in midterm elections. “We’re not denying Democrats are excited,” said Congressman Stivers. “But it’s not my job to cover the spread. This isn’t Las Vegas. My job is to win.” And if the best Republicans could do in a blue wave is to secure the bare minimum of 218 seats, that’s still a win. “That’s how I define success as a majority.”

Despite signs of trouble, GOP says it has road map for November wins

As Election Day nears, it’s looking better and better for Democrats to take over the House. Independent political analysts keep shifting their election rankings for competitive House seats toward Democrats. The FiveThirtyEight blog now gives Democrats a 7 in 9 chance of taking control.

It may be an uphill battle for Republicans, but Rep. Steve Stivers (R) of Ohio feels “pretty good” about his party’s ability to hold the majority, he told reporters at a Monitor Breakfast on Friday. As chair of the National Republican Congressional Committee, he’s charged with winning the House for the GOP. And as a brigadier general for the Ohio Army National Guard, of course he’s got a battle plan.

It’s not very complicated: A positive message of “peace and prosperity” under Republicans, contrasted with a dark future of “poverty and insecurity” if Democrats win, and a full-bore effort to bring out the base – including using President Trump as a motivator.

“We’re not denying Democrats are excited,” said Congressman Stivers. “But it’s not my job to cover the spread. This isn’t Las Vegas. My job is to win.” And if the best Republicans could do in a blue wave is to secure the bare minimum of 218 seats, that’s still a win. “That’s how I define success as a majority.”

Despite a string of negative indicators for Republicans this year, Stivers and House Republicans could still pull it off – though the path to victory is narrow, say political observers. Working against them are the president’s lackluster approval ratings, an average 41.6 percent according to Real Clear Politics; a “generic” House ballot that favors Democrats by an average of more than 8 percentage points (Republicans say that anything over 7 points spells serious trouble); a surge of Republican retirements; and a historic trend of losses for the president’s party in midterm elections.

And then there’s that Democratic enthusiasm, gunning to secure the 23 seats needed for a takeover.

“We don't take anything for granted in the election, but there is a good chance we'll have the gavel on the Democratic side and we will be ready,” minority leader Nancy Pelosi told reporters at the end of House members’ first week back from a five-week recess. “We have come out of August very strong.”

Playing to the base

Quentin Kidd, a political scientist and pollster at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Va., sounds a cautionary note. History may not apply in this midterm.

People are looking at 2018 as if it were the tea party wave of 2010 – but this time favoring Democrats, he says. Eight years ago, Republicans gained 63 seats, flipping the House as swing voters moved against President Obama in a “shellacking” just two years after he took office.

“Everyone thinks this might be 2010 on steroids, but what if it’s not? What if we’ve become so polarized...[that] there is no middle to swing?” Mr. Kidd poses. The swing vote, which he defines as college-educated women with children, is disappearing, moving away from Republicans because of objections to Mr. Trump.

“If this one little swing vote that’s left out there isn’t excited to vote for any individual Democratic candidate, I think that’s the path that Republicans could walk to retain a slim control of the House – or lose the House by a really slim two, or three, or four seats.”

The disappearing swing vote means that more than ever, the 2018 midterms are about turning out the base. And Republicans do that by following the brigadier general’s basic plan, observers say.

The road to Republican control of the House is “not very complex,” says Terry Madonna, a political scientist and pollster at Franklin & Marshall College, in Lancaster, Pa. The challenge for Republicans is to motivate their voters when Trump is not on the ballot. “They’ve got to go to the biggest positive of the administration in an election that’s a referendum on the president,” he says. “If you’re a Republican, that’s the economy, the economy, the economy.”

Indeed, Stivers rattles off the economic highlights: strong economic growth, a jobless rate below 4 percent, wages starting to grow, high consumer confidence. “The economy is undoubtedly roaring.”

The flip side to the positive message is a virulent attack on Democrats.

“They’ve got to completely destroy the credibility of the Democratic candidates that are running against them, or their members,” says Nathan Gonzales, editor and publisher of Inside Elections, which provides nonpartisan analysis of campaigns. That will gin up GOP turnout, and, some analysts believe, perhaps discourage more Democrat-leaning voters who get so turned off by negative advertising that they don’t vote. If a tepid Trump supporter may be considering change, the idea is to get them to think twice about that.

This week, the Republican National Committee released a video ad, titled “Crazytown?” It turns the tables on Bob Woodward’s new book, “Fear: Trump in the White House,” in which Chief of Staff John Kelly is quoted as saying of the president, “He’s gone off the rails. We’re in Crazytown,” according to The Washington Post.

The RNC ad portrays leading Democrats – including Sen. Cory Booker and Rep. Maxine Waters, as well as Representative Pelosi, the minority leader – as encouraging confrontation and uprising, then finishes with what appears to be a clip from street rioting during the president’s inauguration. The last line is: “The Left is Crazytown.”

The role of the president

In an interview with the Monitor, moderate Rep. Tom MacArthur (R) of New Jersey echoes the GOP strategy as he describes his efforts to keep his seat, rated “toss-up” by the independent Cook Political Report. In a swing district where Trump is both vilified and lauded, he says he’s running on GOP results and his own local achievements.

As for the election being a referendum on the president, he says: “If we lose the House, I think what you get is dysfunctional government. The Democrats have made it crystal clear that the fights they want to have are over shutting down ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement], impeaching the president, doing things that will grind any sort of progress to a halt.”

Pelosi has said repeatedly she’s not pushing impeachment, yet at the breakfast, Stivers said the impeachment threat plays well among Republicans.

“Every time [Democratic billionaire] Tom Steyer runs an ad about impeachment he gets a few Democrats excited, but he gets a few Republicans excited too.”

Stivers pushed against the idea that Trump is best used to motivate voters in competitive, red-state Senate races rather than the slew of tight House races that Democrats could win.

“He is part of getting the base out and we will use him,” Stivers said – though not necessarily at big rallies. It might mean robo-calls in some districts, or even direct mail.

Even as Stivers acknowledges the challenges this fall – among them, raising enough money to fund all the candidates he would like to – he says Republicans have learned how to turn out their base by winning eight special elections. Democrats also turned out, but they did not win, he says.

“I’m happy to congratulate [Democrats] on their moral victories,” he said. “But the last time I checked, moral victories don’t get a vote on the House floor.”

Supreme Court hearings are broken, both parties say. How they can be fixed.

Senators of both parties complain that Supreme Court hearings today yield little useful information, with nominees wary of saying anything that might look like prejudging a case. But experts cite past examples that could foster greater insight – and greater civility.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

How nominees answer (or don’t answer) questions in United States Supreme Court confirmation hearings is both a symptom and a cause of larger institutional problems, experts say. Those problems can be addressed, they add, and confirmations could return to the more civil days of old. One important first step: nominees answering questions in more detail. Some scholars think nominees would be able to speak in more detail if senators asked more general questions about a nominee’s judicial philosophy. Others believe the political branches could ease tensions by returning to more bipartisan consultation in selecting a nominee, as happened in the 1990s. The current process “doesn’t really generate much information about what the nominee thinks about important legal issues, and I think everybody knows that,” says John Harrison, a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law. “The court is a powerful institution,” he adds. “This is an important political process, and I think it’s bad for the country that less information is available.”

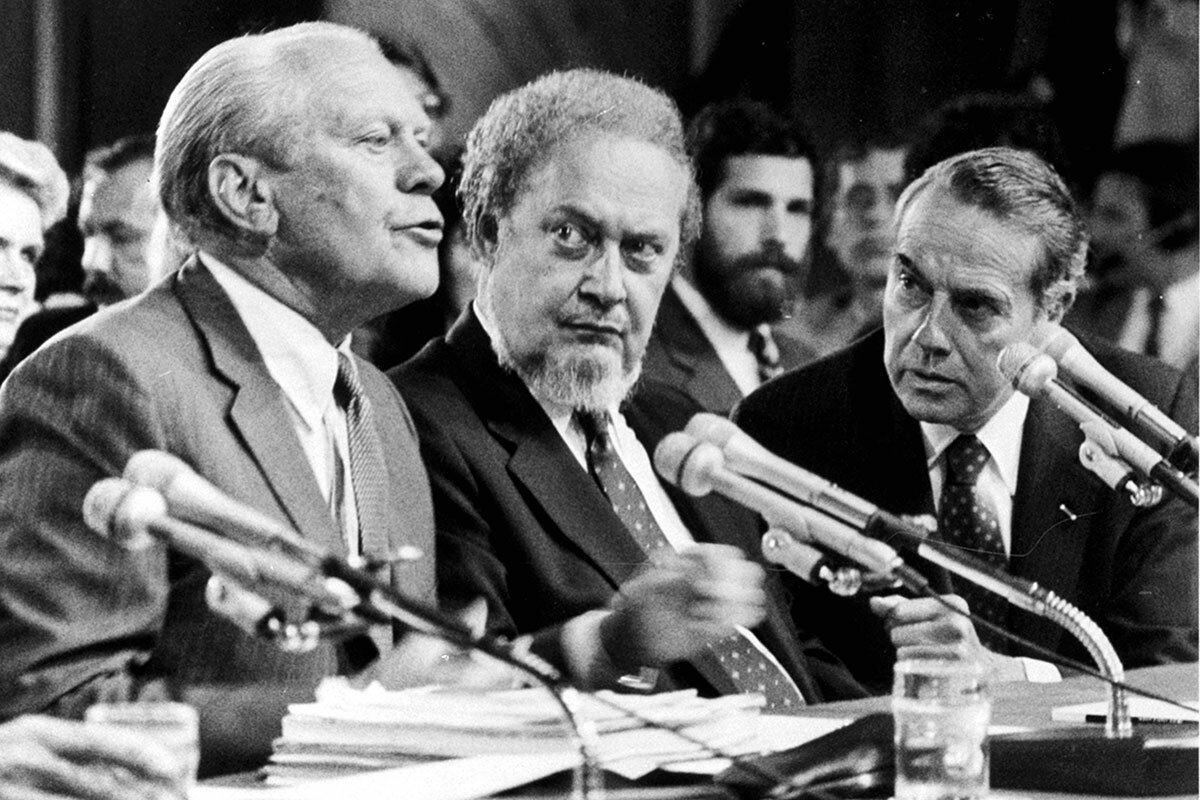

Supreme Court hearings are broken, both parties say. How they can be fixed.

One hundred years ago, they didn’t hold confirmation hearings for the United States Supreme Court.

Backlash to Louis Brandeis’ nomination – fueled in part by his Jewish faith, scholars say – led the Senate to hold its first ever public confirmation hearing for a high court nominee in 1916. Justice Brandeis himself wasn’t required to speak, but the precedent had been set.

Hearings became routine. In 1939, Felix Frankfurter became the first nominee to testify at his own confirmation hearing. In those hearings, Justice Frankfurter declined to answer many questions, saying his public record spoke for itself.

In many ways we have returned to those times, experts say, if we ever left them at all. In recent decades, members of the Senate Judiciary Committee have pressed nominees to discern their views on how they would rule on hot-button issues – with little to no success.

This approach has become so common that Judge Brett Kavanaugh, the nominee to replace retired Justice Anthony Kennedy, said in his own hearings this week that it established a precedent for nominees that “is now in my view part of the independence of the judiciary.”

Judge Kavanaugh said on Wednesday he studied the hearings for Justices Thurgood Marshall and William Brennan, as well as the eight current justices. They almost unanimously declined to discuss past high court decisions beyond saying they are “settled law” – and sometimes not even saying that. They claimed that to do so would amount to prejudging cases they might later hear.

“Why have eight justices, of widely ranging views, done this? The reason is judicial independence,” he added.

As a result, scholars say Supreme Court confirmation hearings in recent years have yielded little useful information. Senators of both parties accuse the other of being either too soft or too tough. Both agree the process has become broken. These issues are compounded by increased partisanship on the court, some say, with Republican- and Democrat-appointed justices often voting as blocs on hot-button issues.

How nominees answer (or don’t answer) questions in confirmation hearings is both a symptom and a cause of larger institutional problems, experts say. But experts say there are examples from the past that could foster greater insight – and greater civility. One important first step: Nominees answering questions in more detail. Some scholars think nominees would be able to speak more freely if senators asked more general questions, such as about a nominee’s judicial philosophy. Others believe the political branches could ease tensions by returning to more bipartisan consultation in picking a nominee, as happened in the 1990s.

The current process “doesn’t really generate much information about what the nominee thinks about important legal issues, and I think everybody knows that,” says John Harrison, a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law.

“The court is a powerful institution,” he adds. “This is an important political process, and I think it’s bad for the country that less information is available.”

Robert Bork’s nomination

Today's Supreme Court confirmation process can be traced back to the failed nomination of Judge Robert Bork in 1987, most scholars say.

Judge Bork, a judge on the D.C. Circuit with a record of controversial legal opinions disputing Supreme Court decisions on issues such as gender equality and workplace desegregation, explained in detail his philosophy that the Constitution should be interpreted only as its writers intended. After the Senate voted 58-to-42 against his confirmation, he said he was “glad the debate took place.”

“Since [then] I don’t think we’ve seen people be that direct and that straightforward.... We’ve gotten into a pattern of more general answers,” says Kimberly West-Faulcon, a professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles.

Senate Republicans this week said that Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg specifically established the pattern of evasive answers seen in high court confirmation hearings, saying in 1993 she would offer “no hints, no forecasts, no previews” on how she would rule on cases that could come before her.

Since then, nominees have taken a similar line, adding that they respect Supreme Court precedent and stare decisis, a principle that the justices should follow high court precedent except in exceptional circumstances.

“The American people don’t want their judges to pick sides before they hear a case.… This is the reason why all Supreme Court nominees since Ginsburg have declined to offer their personal opinions on the correctness of precedent,” Sen. Chuck Grassley, (R) of Iowa, said in his opening statement.

Senate Democrats have complained this week that, while recent nominees have voiced their respect for settled law, once they get to the court they have voted to overturn or severely narrow precedents. In an interview with NPR on Wednesday, Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, (D) of Rhode Island, cited rulings on campaign finance, voting rights, and public union fees as examples of “big decisions completely unsupported under precedent.”

The Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Roberts has overturned 1.38 cases per term – a lower rate than three prior courts dating back to World War II, according to a recent analysis by Jonathan Adler, a professor at Case Western Reserve University School of Law. Other research has found that the Roberts court has narrowed past rulings, including on issues such as abortion and juvenile life without parole, though not significantly more than other courts.

Justice Kennedy provided the deciding vote in several Roberts court cases overturning precedent, including the 2015 Obergefell v. Hodges decision legalizing same-sex marriage and June’s Janus v. AFSCME decision finding public union fees unconstitutional. Expecting a nominee more ideologically conservative than Kennedy (which Kavanaugh is, according to most experts and statistical analyses), Professor Adler predicted that “the Roberts Court is not likely to overturn precedents at a more rapid clip going forward.” Where it does, though, he added, “it may tend to do so in a more conservative direction.”

Settled law ... or correct law?

One precedent has been brought up repeatedly at this week’s hearings: Roe v. Wade, which legalized abortion in 1973. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, (D) of California, asked Wednesday if Kavanaugh thought Roe is “correct law.” And she asked again Thursday, citing a 2003 email, leaked to The New York Times, where he said it was not settled law because three justices at the time would have overruled it.

“Roe v. Wade is an important precedent of the Supreme Court, it’s been reaffirmed many times,” he answered. “That precedent on precedent is quite important as you think about stare decisis in this context.”

“You believe it’s correctly settled. But is it correct law in your view?” Senator Feinstein asked.

Kavanaugh replied: “I have to follow what the nominees who have been in this seat before have done.”

There were many yes-or-no questions like Feinstein’s from Democrats. Some scholars think nominees would be able to speak in more detail if senators asked more general questions about a nominee’s judicial philosophy.

The Constitution “gives substantial discretion [to judges] over how its ambiguous portions are interpreted,” says Professor West-Faulcon. “It would help a senator to know … what their judicial philosophy [on giving] meaning to ambiguous portions of the Constitution is.”

Of course, explaining his judicial philosophy is part of what cost Bork his confirmation. So some experts say the political branches could ease tensions by doing more bipartisan consultation in picking a nominee.

President Bill Clinton’s work with Sen. Orrin Hatch (R) of Utah on confirming Justices Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer is an oft-cited example. Senator Hatch recommended both, writing in his biography that “while liberal, they were highly honest and capable jurists [and] likely better than the other likely candidates from a liberal Democrat administration.”

Both Ginsburg and Justice Breyer were confirmed comfortably.

“There was some meeting of minds and some deference,” says Carl Tobias, a professor at the University of Richmond School of Law and an expert in judicial selections. “That sounds a little old-fashioned these days.”

For West, Myanmar leader’s fall from grace muddies response to a crisis

Admirers of Aung San Suu Kyi’s work as democracy activist have been bewildered by her silence on the Rohingya crisis and on the sentencing of two journalists who covered it. Now that confusion is complicating the world’s response.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Western policy toward Myanmar has long viewed Aung San Suu Kyi, the longtime pro-democracy activist, as a symbol of defiance against the military. Three years ago, when the Nobel Peace Prize winner swept elections, many took it for a new dawn in Myanmar, after half a century of military dictatorship. Today, some of those hopes seem dashed. Last week, a United Nations mission investigating the army operation that has forced nearly 700,000 Muslim Rohingya to flee called for military leaders to be prosecuted for genocide, among other crimes. This week, two Reuters journalists who reported on army atrocities were sentenced to seven years in jail. And throughout it, Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi has stayed relatively silent, as the international community debates how to respond. Many emphasize that her power is sharply limited by the military’s continued grip. But others are still pinning their hopes on her leadership, says Brad Adams, Asia director for Human Rights Watch. “Western countries have been punching below their weight,” he argues, “because they wanted to believe the myth that Aung San Suu Kyi is a divinely inspired leader who just has a few political problems to sort out before she leads her country on the path to reform.”

For West, Myanmar leader’s fall from grace muddies response to a crisis

Three years ago, the world cheered as Nobel Peace Prize winner and democracy icon Aung San Suu Kyi swept elections in Myanmar, promising a new dawn after half a century of military dictatorship.

The applause has quickly died, however, supplanted by dismay at signs that Western governments’ faith in the new regime was misplaced, and by uncertainty about how to treat the authorities in Myanmar, formerly known as Burma.

Last week, a United Nations mission investigating the army operation that forced nearly 700,000 minority Muslim Rohingya to flee the country over the past year called for Myanmar’s military leaders to be prosecuted for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes.

This week, a judge in Yangon sentenced two Reuters journalists to seven years in jail, convicting them of breaking the colonial-era Official Secrets Act by their reporting of army atrocities, and brushing aside evidence they had been framed by police.

Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi, the de facto head of the Myanmar government, spoke up neither for the Rohingya, nor for the journalists. Abandoning her previous opposition role as a human rights spokeswoman for the nation, she has “made a 180 degree turn from the Aung San Suu Kyi we thought we knew,” says Brad Adams, Asia director for Human Rights Watch.

That has pulled the rug out from under Western policy towards Myanmar, which has long been founded on support for her as a symbol of defiance against the military. It has left Western countries struggling to find an effective policy to help the Rohingya, nearly 1 million of whom are now refugees in Bangladesh.

Yet many are still pinning their hopes on Aung San Suu Kyi, Mr. Adams says. “Western countries have been punching below their weight,” he argues, “because they wanted to believe the myth that Aung San Suu Kyi is a divinely inspired leader who just has a few political problems to sort out before she leads her country on the path to reform.”

Military calling the shots

Observers familiar with Myanmar say Western hopes for a new democratic Burma were never realistic. Before the generals began to loosen their grip, they pushed through a constitution that “keeps the military in power perpetually,” says David Steinberg, the doyen of American Burma analysts, now a professor emeritus at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C.

“Aung San Suu Kyi doesn’t control society or the administration at all,” he adds. “Just parliament.” And even her majority there is not large enough to change the constitution.

The military, meanwhile, are not under civilian control: They name the ministers of defense, interior, and border affairs; they set their own budget; and they dominate the most important institution in Myanmar, the National Defense and Security Council. “They have all the levers of power,” says Mark Farmaner, head of the Burma Campaign UK, an advocacy group.

That limits Aung San Suu Kyi’s room for political maneuver. But even in fields where she does have authority, experts say, she has not used it in ways that might upset the army. Her government could have put a stop to the trial of the two journalists, for example, or it could have granted them amnesties.

Last year Aung San Suu Kyi “had enough moral capital to turn the tide” and combat the widespread bias against the Rohingya among the majority Bamar ethnic group, says Mr. Adams. “But she didn’t speak out.”

Looking for levers

For many Myanmar observers, the Reuters case is only the latest indication that Western governments cannot rely on Aung San Suu Kyi to strengthen pillars of democracy such as press freedom. Nor is she in a position to secure the return of Rohingya refugees, which she says she wants, because she has no authority over the military, and thus no power on the ground to protect returnees.

If that leaves Western governments few levers with which to reverse the deterioration of democracy and human rights in Myanmar, they seem reluctant to exert any real pressure on Yangon.

So far, in response to the army’s campaign of murder, rape, arson, and ethnic cleansing that has left tens of thousands of Rohingya missing and feared dead, the United States, Canada, and the European Union have imposed financial sanctions and travel bans on just a handful of generals involved in the operation.

“The military got the message that for the so-called greater good of reforms taking place, the international community considers the Rohingya expendable,” Mr. Farmaner says.

He and other rights activists are calling on governments to do much more, such as push for criminal investigations into allegations of crimes against humanity at the International Criminal Court. The court ruled Thursday that it does have jurisdiction.

Activists are also demanding that governments suspend economic aid until the Rohingya are re-settled in their homes under international protection, slap travel bans on all military personnel, or reimpose economic sanctions on Yangon.

Such sanctions were credited with playing at least a partial role in forcing the military government to launch its economic and political reform process seven years ago. But some analysts doubt whether they would be useful today.

Toward the end of the military dictatorship, the generals feared that Myanmar was coming to resemble a Chinese province because of Beijing's heavy economic influence. Opening up to investment from other countries, they hoped, would neutralize their dependency on China.

But Western investment has not poured in as expected. Foreign investment has fallen for the past two years, and a US law firm that opened an office in Yangon in 2013 as a ‘one-stop-shop’ for foreign investors closed its business last February. Meanwhile, China is rekindling relations that cooled during the first years of Myanmar’s reform process – which would help blunt the effects of any Western sanctions.

“If sanctions were imposed I don’t think the generals would be at all affected,” argues Michael Buehler, an expert on Southeast Asia at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. “It would not lead to a change in regime or in political trajectory.”

An added difficulty with sanctions would be deciding when to lift them, suggests Professor Steinberg, arguing “there is no chance in the foreseeable future” that Yangon would treat the Rohingya in a way the West would find acceptable, such as by granting them Myanmar citizenship. (Most are stateless, as Yangon considers them illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, despite many families’ generations-old roots in Myanmar.)

A less mentionable calculus may be driving Western policymakers, suggests Dr. Buehler, if they are drawing on their experience 20 years ago with Indonesia as it emerged from military rule. “The price the West had to pay for democracy in Indonesia was not addressing the army’s human rights violations,” he recalls. “We should consider that strategy, however awful it sounds.”

But pressure to take more concrete action is likely to rise with the upcoming publication of the UN fact-finding mission’s full report, supporting allegations of genocide by the military against the Rohingya. The US State Department is also due to release its own report shortly.

“There will be strong words,” predicts Adams. “But will they be driven through on the ground to actually affect the generals’ lives? Until that happens, I don’t think we’ll see any change.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The truth about South African ‘land seizures’

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor’s Editorial Board

South Africa is undertaking a difficult but needed debate on how to put more farmland into the hands of its black majority. The government in Pretoria seeks to deal with an unemployment rate that’s now at 27 percent and rising. The stability and prosperity of South Africa, whose economy provides an anchor for the African continent, are at stake. Under consideration: a change to the nation’s Constitution to allow the government to take private agricultural land in certain cases. No law has yet been passed nor decision made, and the situation is nuanced. The reason for pursuing reform is rooted in colonial times, when white immigrants took over vast areas of land. Today, white farmers own nearly three-quarters of the country’s private farmland, though whites make up less than 10 percent of the population. If carried out properly, land redistribution could be a boon for the country. South Africa must find a way forward that is fair and equitable to all.

The truth about South African ‘land seizures’

A respect for property rights is seen as a fundamental aspect of American society. So when word comes that an African country is seizing private land from its citizens alarms can be raised. But a closer look reveals a more nuanced situation.

The government of South Africa is dealing with a challenging problem: Its unemployment rate is at 27 percent (the United States unemployment rate is 3.9 percent) and rising. The stability and prosperity of that country, a democracy whose economy provides a vital anchor for Africa, a continent of 1.2 billion people, is at stake.

Cyril Ramaphosa, the president of South Africa (previously a successful businessman), is weighing the possibility of changing the nation’s Constitution to allow the government to take private agricultural land in certain cases. But no law has been passed or decision made.

The reason for such a dramatic move extends back to colonial times, when white immigrants took over and began to farm vast areas of land. Today white farmers own nearly three-quarters of the private farmland, though whites make up less than 10 percent of the population.

Mr. Ramaphosa has promised there will be “no land grab.” Issues of compensation and the details of how a program might work are under discussion. What is most likely to happen first is that undeveloped government-owned land will be offered to black farmers.

Several years ago a land seizure from white farmers in neighboring Zimbabwe did not go well. Although it did raise some rural blacks out of poverty, the scheme was part of a series of economic moves by President Robert Mugabe that, as a whole, failed miserably.

While white South African farmers have reason for concern as to how a government land redistribution program might affect them, many South Africans also know that more land ownership for black farmers, if carried out properly, could be a boon for the country.

“We need more black farmers on more black farms in an orderly and sustainable way,” Dan Kriek, head of Agri SA, which opposes land seizures, told the Financial Times.

“The debate needs to happen,” says a successful black South African farmer. “You cannot have six or seven guys with mega farms surrounded by black communities whose only contribution is their labour,” he said. “If we as agriculture don’t radically change … we’re in trouble. The other side of the fence is getting very impatient.”

South Africa needs to talk through its tricky land reform question and find a way forward that is fair and equitable to all.

What's happening is much more complex than a quick first look might suggest.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Divine care for all

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Deborah Huebsch

Inspired by the Joshua trees that thrive in the stark Mojave Desert, today’s contributor explores the idea that God furnishes all of us, His children, with what we need to not only survive, but blossom, wherever we may be.

(Editor’s note: An earlier version of today’s Daily repeated yesterday’s Perspective column.)

Divine care for all

Joshua trees grow only in the Mojave Desert, where the annual rainfall averages less than five inches and temperatures range from well below freezing to over 100 degrees Fahrenheit. These stately trees grow and thrive in what appears to be pure rock and sand.

With such a forbidding environment surrounding these forests, it is difficult to imagine anything growing there at all. But despite this harsh environment, the trees grow to a height of between 15 and 40 feet. They have spiky green leaves and beautiful waxy white flowers.

This sign of abundant life in the most austere surroundings has meant a lot to me. The ability of Joshua trees to flourish even in such a harsh setting symbolizes for me what I’ve learned in Christian Science about the nature of God as the divine Love that imparts goodness and peace to all. It is the nature of infinite Love to furnish us with what we need to not only survive, but blossom, even in tough conditions. The practical outcome of Love’s care for its creation is captured in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by the discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy. It says, “Divine Love always has met and always will meet every human need” (p. 494).

When we look at the world around us, this is not always evident. But I’ve found that prayer based on God’s limitless love helps us see things differently – to the point where what is spiritually true actually does become more evident in our lives.

At one time years ago, I had no money and was completely out of food. It was a pretty desperate situation. But I was learning to trust in God’s care for all creation, including me. As I prayerfully acknowledged God’s unfailing love, I began to feel that love so tangibly that I came to expect that my need would be met. It was, in a most surprising way.

Within hours of my prayers, a friend showed up at my door with two armfuls of groceries. She hadn’t known of my need but explained, “I was shopping and suddenly felt impelled to get you some groceries.” It turned out to be more than enough to tide me over until needed income came in.

While this example may be small compared to other things going on in the world, to me it was a proof that God’s care really is true for everyone. And that is a thought I have cherished for others in praying about situations in our world where there is great need. I have prayed recognizing that divine Love is universal and impartial, caring for all.

One issue that’s been close to my heart lately is the wrenching refugee problem in so many parts of the world. I’ve asked myself, How can I pray for those who have been forced to leave their home? Like the climate and terrain of the Mojave Desert, the new places these individuals find themselves in can be hostile and difficult, especially if refugees face pointed resistance in their new homeland.

As I’ve prayed, I’ve been reminded of what Christ Jesus taught about God’s care for all: “Consider the ravens, for they neither sow nor reap, which have neither storehouse nor barn; and God feeds them. Of how much more value are you than the birds?” (Luke 12:24, New King James Version). As God’s spiritual creation, we are each greatly valued. And with an openness to the spiritual truth that God loves us and provides for all needs, be they large or small, we’re better equipped to discern inspired ideas that come – sometimes out of the blue – about ways to help.

There’s no simple solution to the refugee crisis. But prayer can replace a sense of despair and hopelessness with confidence in the Divine to support the wisdom of those leading humanitarian efforts, bring creative ideas to those in government, and touch hearts near and far to feel a sense of hope and trust in God’s goodness.

A message of love

Serious business at the fair

A look ahead

Have a good weekend and catch us again on Monday. We’ll be looking at a coordinated prison strike in the US that aims to shed light on prisoner rights – and whether anyone is listening.