Justice may be seen as a concept that has no geopolitical boundaries. But today we have two stories on global justice, including this one that rejects putting limits on American safety and sovereignty.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

David Clark Scott

David Clark Scott

The outcome of Friday night’s Ocean Springs, Miss., high school football game rested entirely on the shoulders of the homecoming queen.

That’s right, Kaylee Foster was crowned at halftime and then kicked the extra point in overtime to lead the team to victory, 13-12.

Kaylee’s success isn’t unique. Tiaras and football pads are becoming a thing in America.

Last fall, North Carolina kicker Julia Knapp was crowned homecoming queen and the offensive player of the game. In Grand Blanc, Mich., last year linebacker Alicia Woollcott was the second high school football player in her state to be voted homecoming queen. In the past year, at least five states have celebrated these queens who wear football jerseys.

While fewer US teens are playing high school football, the number of girls donning cleats is rising. It’s still a small number. But kudos to the young women redefining gender stereotypes. "Don’t feel sorry for me and don’t help me up when I get knocked down, I know what I’m doing and I know why I’m here,” Alicia told her coach.

On a Friday night, with a few seconds left, the game hanging in the balance, every coach wants an athlete who’s poised, consistent, and fearless in the face of adversity. Those are qualities that have nothing to do with gender.

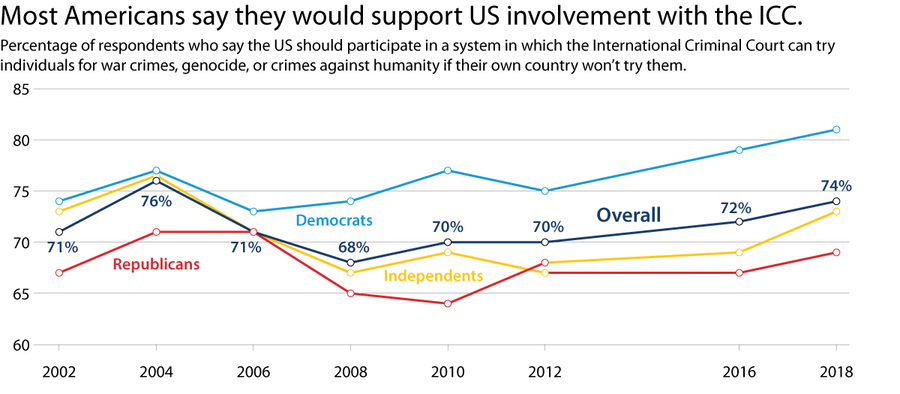

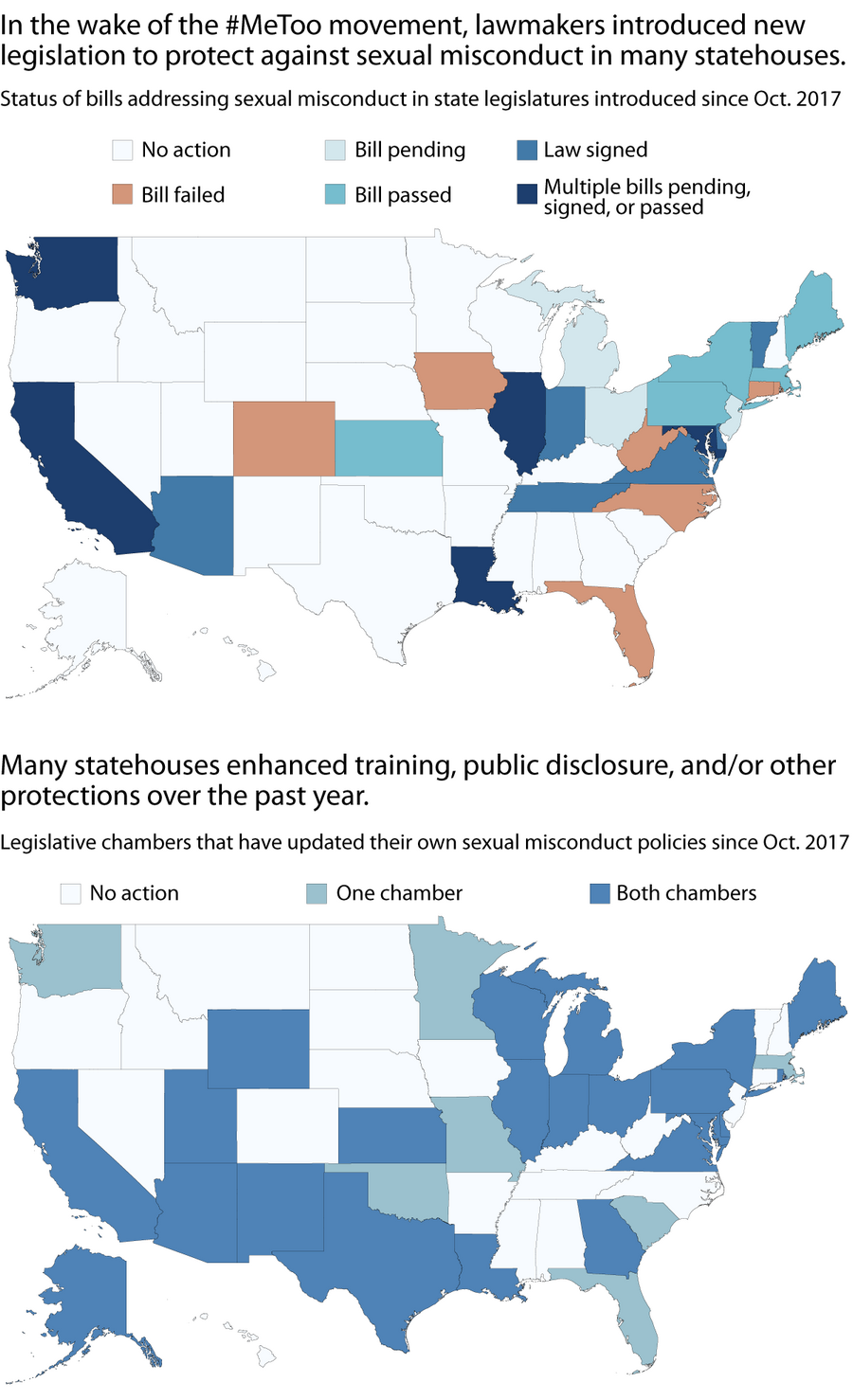

Now to our five selected stories, including a fresh look at international justice, progress on sexual harassment in the US, and inspiring reads for September.