- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- A do-over? Calls mount for British to vote again on Brexit.

- Once again, hard times in US farm country coincide with a trade war

- Find parking? Check. Next, hire staff. Congress’s new members file in.

- Global progress on extreme poverty still goes unnoticed

- China sprints toward next sports goal: half a billion weekend warriors

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How chess matches all the world’s moves

An American is vying to be the world chess champion, and few in the United States know about it.

One reason may be the news coverage, which has been understandably sparse. Watching two guys stare at a chessboard for hours on end doesn’t exactly pack the punch of basketball – or curling.

Another reason is that the world has changed since 1972, the last time an American played for the chess championship. Back then, the victory of American challenger Bobby Fischer over Soviet champion Boris Spassky was as much about geopolitics as chess. Today, the US-Russian rivalry, while still important, doesn’t retain the same cold-war relevance.

And thanks to strides in artificial intelligence (AI), world chess champions are no longer regarded as incomparable geniuses. Anybody with a good chess program can beat them.

What’s telling is that chess hasn’t become irrelevant in the face of these political and technological changes. It has adapted. Chess champions now come from other places than Russia. The current champion, Magnus Carlsen, is Norwegian. His predecessor was from India. And instead of AI replacing human chess, top players use it to improve their game – a good example of how workers aren’t doomed to lose out to machines if they’re willing to change.

After eight games of their 12-game showdown in London, Mr. Carlsen and US challenger Fabiano Caruana are tied. Play resumes Wednesday.

Now, on to today’s winning stories.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A do-over? Calls mount for British to vote again on Brexit.

In a democracy, when have the people really decided? Disappointment with the British government's negotiated terms for withdrawal from the European Union is fueling a campaign for a second Brexit referendum.

When Britons voted by a narrow majority in 2016 to leave the European Union they knew what they were getting out of, but they didn’t know what they were getting into. Now, Prime Minister Theresa May has presented the final terms of the withdrawal agreement she has reached with the EU, and nobody is happy with them. “Remainers” say the deal cedes too many of the advantages of EU membership; “leavers” says it doesn’t offer enough of the advantages of getting out. That has strengthened a campaign in favor of a second Brexit referendum, now that the choices are clearer. Supporters of that idea argue that it is only fair that the British people should have the final say on their future. Opponents say they’ve had that say and that remainers are just trying to get a second bite of the cherry they missed last time. But if Parliament rejects Ms. May’s deal, as seems likely, a second referendum could be the only way to avoid Britain crashing out of the EU with no agreement at all, which everyone agrees would be an economic disaster.

A do-over? Calls mount for British to vote again on Brexit.

On a busy market square, Diane Holden stands by a whiteboard attached to a metal railing. “Brexitometer” it reads – a play on Brexit, the all-consuming national drama – above a row of columns.

Ms. Holden and her Brexitometer are part of a widening campaign to hold a second referendum on whether Britain should leave the European Union, which is what 52 percent of voters backed in a 2016 vote. Campaigners want another plebiscite on the Brexit deal, a do-over that could stop it in its tracks.

“How do you feel about the process?” she asks shoppers, competing with the throaty cries of fruit-and-vegetable sellers for their attention. “Do you think it’s going well?”

Those who stop to talk are invited to put colored dots in the whiteboard columns. Aylesbury, a prosperous rural market town 45 miles northwest of London, narrowly voted “Leave” in 2016, but many residents are unhappy with the way things have worked out since. Is Brexit going well? (Most chose No.) Will it be good for jobs? (No.) Should there be a new national vote on the final deal? (The clincher: Yes.)

What began as a quixotic and quarrelsome campaign, dismissed by Brexit backers as a fringe rearguard action, has in recent months moved into Britain’s political mainstream. Last month 700,000 people marched in London in favor of a “People’s Vote,” and support has built up among members of parliament from all parties.

Between ‘vassalage’ and ‘chaos’?

Last week Prime Minister Theresa May unveiled her draft agreement with the EU on the terms of Britain’s withdrawal. It sparked a storm of criticism within her ruling Conservative Party, largely because it would keep Britain in the EU customs union for several years at the cost of limiting national autonomy. Should parliament reject the deal, as seems likely, Britain would be on track to crash out of the EU in disorderly fashion, with no deal in place.

That stark prospect has begun to rattle politicians who had backed Ms. May’s Brexit strategy. Jo Johnson, whose brother Boris Johnson is a prominent Brexiter, quit earlier this month as her transport minister. What Britain was being offered, he complained, was a choice between “vassalage” (May’s deal) and “chaos” (no deal). He called for a second referendum.

In an editorial, the left-leaning Observer newspaper wrote on Sunday that “There is a watertight case for a referendum on the deal: we now know the terms of exit, there are huge unforeseen costs, and the public must have a say.”

Still, the political and legal paths to voting again on Brexit – and potentially reversing it – are tortuous. Both May and her opposition counterpart, Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, oppose the idea. There is little time left to dither: Britain is due to leave the EU on March 29 next year. For many voters who ticked the “Leave” box in 2016, another referendum would be a betrayal of what had been proclaimed a binding vote.

Public opinion remains sharply divided on Brexit, though polls now show an edge for “Remain,” says John Curtice, a professor of politics at Strathclyde University who closely tracks polling data. That edge, however, is largely down to the views of young people, who turned out in lower numbers than their elders in 2016, and of those who abstained.

Even if Britain were headed for a cliff-edge, crash-out exit, “do not expect Leave voters to change their minds” in a second vote, says Professor Curtice.

A narrow majority also supports a second referendum, widely seen as a bid by Remainers to have a second bite at the cherry they missed last time.

A threat to democracy?

In the wintry sunshine of Aylesbury there is plenty of grumbling at the government’s handling of Brexit and trepidation at what will follow. But there is little sign of opinion shifting at this defining political moment for Britain.

Lorraine Bail, whose husband works in Belgium, voted Remain in 2016. But she’s not sure that holding another referendum is the answer to a political impasse. “We voted, and even though I disagree with the vote, we’re in a democracy and the majority has to have their say,” she says.

“It seems to be taking so long,” says Bob Dormer, a driver who abstained in 2016. At the garage where he works, Leave was a popular choice. He puts this down to the promise of more money for public health services, which has since been debunked, and says he would like to see another referendum.

“A lot of people voted to go out and now realize what a waste of money it’s been,” he says.

Holden was one of half a dozen activists on Saturday at the Brexitometer, handing out stickers and leaflets to passersby. They did not impress Philip Skola, a retiree, who stopped to berate one of the volunteers. “If you respect democracy, we voted to come out and that’s how it should be,” he said.

Asked whether it would not be fairer to give people a say on the final terms of the deal, Mr. Skola’s face darkened. “If we lost this then I’d never vote again. Democracy is dead,” he snorted.

Analysts have warned of civil unrest if the results of the first referendum are overturned and some say a second campaign would be more divisive than the last one. It’s not clear what question would be on the ballot; a three-way choice between the terms of May’s deal, crashing out with no deal, or simply remaining in the EU, might yield no decisive outcome.

Bad math in Parliament

For the time being, the question is moot; Parliament must vote first. But the math there looks bad for May, and “if the government loses the vote in the House of Commons, all bets are off,” Curtice says.

If Britons are indeed asked again to make up their minds on EU membership, the future is unclear. It would not take much of a shift to change the last referendum’s outcome, and while most voters have stuck to their 2016 views, some have changed their mind.

Emma Jiao-Knuckey is one of them. She lives in Southend-on-Sea, a strongly Leave constituency, and she voted with the majority in 2016, persuaded by the prospect of more money for health and social spending. Her two sons are both diagnosed as autistic.

Leavers based much of their appeal on a promise that if London was no longer paying in to the EU budget the government would have $450 million a week to spend on its creaking National Health Service. This was untrue.

Now Ms. Jiao-Knuckey is a volunteer for the People’s Vote campaign and joined its recent march in London. The 2016 referendum result does not constitute informed consent, she says, and it would be better if voters had a say on the final terms of the withdrawal deal.

However the vote turned out, she says, “at least I’d have the peace of mind of knowing that we were informed. We’ve got to live with this for a very long time.”

Once again, hard times in US farm country coincide with a trade war

Farmers are resourceful by necessity. But many face a test as a US-China rift undercuts their exports – a challenge familiar to those who weathered the US wheat embargo against the Soviet Union.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

When President Trump imposed tariffs on China, Beijing's response included an embargo against US soybeans. Grain prices plunged amid fears of a trade war and bumper world crops. Now the US farm belt faces its toughest slump in a generation. “I understand the uncertainties of weather,” says Richard Schlosser, a farmer in North Dakota. “We live with the uncertainty.” But he calls the tariffs “so frustrating – just no rhyme or reason for us to get whacked with this.” Federal relief aimed at affected farmers doesn’t fully offset the damage. Some face tough adjustments as their debts stack up against a likely decline in land values. This isn’t the first time that a farm slump has coincided with rising trade barriers. And the changes can be lasting. In the 1980s, a US ban on wheat exports to the Soviet Union gave other nations an opening to grow more. The US share of the world's total wheat exports has declined. Referring to that experience, Mr. Schlosser says, “My farming career has been bookended by an embargo.”

Once again, hard times in US farm country coincide with a trade war

Roger Zetocha is ready to harvest soybeans that nobody wants.

It’s not the quality of the brown plants in the field, which is so good it’s expected to produce a record crop nationwide. It’s not the rain that fell overnight, making the black earth still sticky this particular morning.

The trouble is China. In retaliation for US tariffs on many of their goods, the Chinese are no longer buying US soybeans. As a result, crop prices have plunged, squeezing farmers’ already shrinking income, especially here in North Dakota. Given the ominous clouds that are already gathering over agriculture, the soybean embargo has producers worried, especially older ones who remember earlier crop embargoes that turned out badly.

“I’m afraid that we’re seeing the same scenario set up again,” says Mr. Zetocha, near the town of Stirum. “[President] Trump is talking about putting more tariffs on China,” unless a bilateral deal is reached. “Even if they agree tomorrow, it’s going to take a long time to get things back.”

If history is any guide, things may never go back exactly to what they were. In nearly 50 years of food embargoes by and against the United States, American farmers have lost their preeminent role in export markets. While it’s not clear that embargoes trigger the periodic financial squeezes that plague the farm sector – the evidence is mixed – they often occur around the same time.

“My farming career has been bookended by an embargo,” says Richard Schlosser, a farmer in Edgeley, N.D., an hour west of Stirum. “I farmed in the ’80s through the wheat embargo [against the Soviet Union]. And that market never did come back.”

That embargo allowed other countries to compete for global market share with the US. Now, preparing to hand the reins to his son, Mr. Schlosser fears a similar fallout this time. “I understand the uncertainties of weather,” he says. “We live with the uncertainty. But to have the unilateral imposition of tariffs is just so frustrating – just no rhyme or reason for us to get whacked with this.”

Farm income down 40 percent

China’s whack has hit North Dakota farmers especially hard. They have spent the past two decades moving from wheat to soybeans to feed the Chinese market. Trains whisked away their crop to Pacific ports so they could be shipped to Asia. With that outlet closed since the summer, local soybean prices have crashed.

At a grain elevator in Forman, N.D., soybean prices are fetching less than $7 a bushel, down from $9.50 earlier this year. If prices stay low, few farmers will be able to turn a profit with soybeans. Many will switch to wheat, corn, or other types of beans, but the markets have already anticipated that switch. Corn and wheat prices are down everywhere.

“People are nervous about 2019,” says Nathan Kauffman, an agricultural economist at the Omaha branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. “There’s a lot of downside risks there.”

Farmers are used to the occasional down year. But four years of declining farm income, which last year fell 40 percent below the heady highs of 2013, have economists worried. Many farmers who didn’t used to have to borrow to put in a crop are now taking out loans of over $1 million, Mr. Kauffman points out. Also, some operators are selling off land or other assets to pay down debt and stay in business – or they’re getting out of farming altogether.

For grain farmers, the next hurdle comes early next year when they’ll sit down with their bankers to figure out what loans they’ll need to plant in the spring.

Here in southeastern North Dakota, yields have been so good that Jeff Anderson, branch manager of the Sargent County Bank in Forman, is cautious rather than gloomy. Aside from one farmer’s retirement, he doesn’t anticipate any of his customers leaving farming. “We are not in a critical situation, but we are one event away from it,” he says.

Nationally, the picture is more varied. Some 4 percent of farmers have lost money over each of the past four years, says Allen Featherstone, an agricultural economist at Kansas State University in Manhattan. “Those farms are going to be making some major adjustments.” At the same time, a third of farmers made money in each of the past four years.

For younger farmers, new lessons

One differentiating factor is age. Young farmers just starting out have to rent or buy land and machinery, so they often have to borrow from a bank. And if they haven’t been in farming for a decade or two, they’ve only known good times in agriculture, unlike older producers who survived the 1980s.

“These guys that are 25, 30, 40 years old, holy buckets, they haven’t had any crisis problems or been around them,” says Bob Schaefer, a former credit counselor for the US Department of Agriculture for North and South Dakota. “And somebody gives them a line of credit, and a million might be a conservative number for operating, and nobody to check on how he spends it…. They think they’re millionaires.”

Some bought new machinery – a John Deere combine now costs $600,000 before any attachments for harvesting corn or soybeans – or built $500,000 to $1 million homes.

The challenge is that now the trends are all pointing the wrong way: falling income, rising debt, and the prospect of falling land prices. The Trump administration is targeting $12 billion in new farm aid to help mostly soybean and hog farmers as the groups most affected by the Chinese embargo. But even with those payments, farm income is still likely to fall again slightly this year and next, according to the Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute at the University of Missouri at Columbia. FAPRI also forecasts farmland prices will fall 3 percent over the next three years.

The risks of falling land prices

The last time agriculture encountered that toxic brew was in the 1980s. And, in something akin to the housing crisis of 10 years ago when homeowners had high debts on homes that were losing value, thousands of farmers lost their farms because their debts were too high once farmland values plunged.

The financial stress on the farm is already spreading outward. Many farmers are buying less.

“People have pulled back the throttle a little bit,” says Darin Karlgaard, store manager for a John Deere equipment dealership in Lisbon, N.D.

The stress on farm families is often less visible, but its effects can be wrenching, even deadly. Between 1999 and 2016, North Dakota saw its suicide rate surge 58 percent, the largest among the states and more than double the national increase, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Through September, this year’s suicide-related calls have already surpassed the total for all of last year, according to Cindy Miller, executive director of FirstLink, which runs North Dakota’s 211 helpline as well as helping to man the national suicide crisis line.

How many suicides are related to farm financial stress is not known. Half the calls are from rural areas, Ms. Miller says. “We’re seeing a significant increase in males over the ages of 60, 65, which is significant.”

The extension service of North Dakota State University, which works with farmers, has begun offering suicide-awareness training to all its local agents.

It’s still unclear how much the present strains will end up echoing the 1980s. Agriculture is such a volatile industry that a crop failure anywhere in the world could send crop prices soaring again. And interest rates, while rising, are nowhere near the double-digit levels of the early 1980s.

Also, during the farm crisis of the 1980s, a whole generation of young farmers learned how to operate their farms with less debt and lower risk. Now, as they pass on their operations to their sons and daughters, they’re bringing those hard-won lessons to the table.

Hope, glimmering on the plains

“One thing I learned from the ’80s – and maybe not a good thing – I became very cautious,” says Schlosser. Like farmers everywhere, he’s expanded the operation he inherited from his father, but as he prepares to pass on the farm to his son, the farm carries far less debt. And his son has a job in town, a diversification of income off the farm – similar to what his wife did in the 1980s when, despite six kids being at home, she went back to work as a nurse.

Most farmers still have time to make similar kinds of adjustments. One of the most visible changes in this part of North Dakota is all the new grain bins that farmers have put up. Rather than selling their crops at fire-sale prices, producers are storing them in anticipation of a higher return. The steel bins are so shiny and new that when the sun comes out, the glimmer can be seen for miles.

It’s a gamble. If prices don’t recover, it means thousands of dollars down the drain. But farmers tend to be an optimistic lot.

“If we get some of our trade issues figured out and then we stop producing such great crops every year, we could see prices rebound and that would help farmers quite a bit,” says Scott Gerlt of FAPRI. “There is nothing preordained about the crisis.”

Find parking? Check. Next, hire staff. Congress’s new members file in.

This incoming class in Congress may be the most diverse in US history – including the first Muslim and Native American women. Here’s a look at some of the new faces on Capitol Hill.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

As the dust settles from this year’s tumultuous midterm elections, the incoming class of new lawmakers are now stepping up to their next challenge: setting up shop. The task includes everything from hiring staff to securing offices to figuring out where the bathrooms are. It’s a blunt reminder that serving in Congress, for all its heady glory, is also a real job. Locking down logistics in the first few weeks assures a better chance of a smooth transition after the swearing in on Jan. 3, and could mean the difference between an effective first term in office and a fruitless one. That means, above all, putting together a strong staff early on. “I always tell new members, ‘This group has more influence in your success than any other group of Americans,’ ” says Brad Fitch, chief executive of the nonpartisan Congressional Management Foundation. “This is a marathon, not a sprint.” Week two of orientation begins the Tuesday after the Thanksgiving holiday. In the meantime, read on to meet some of the new House members of the 116th Congress.

Find parking? Check. Next, hire staff. Congress’s new members file in.

They file into the auditorium in twos and threes, talking in hushed voices, settling into the plush navy seats that face the stage. Outside, in the marble hall, staff redirect anyone who wanders into the wrong door or hallway – and plenty of them do.

A sign on an easel declares, “New Member Orientation.”

It could be the first day on any college campus across the United States. Except this happens to be Capitol Hill, and these freshmen are the newly-elected members of the 116th Congress.

As the dust settles from this year’s tumultuous midterm election, this class of lawmakers – heralded as the most diverse in US history – are now stepping up to their next challenge: setting up shop. The task includes everything from hiring staff to securing offices to figuring out where the bathrooms are across the 540 rooms that populate the Capitol building.

It’s a blunt reminder that serving in Congress, for all its heady glory, is also a real job. Picture a small business owner wrestling with all the usual details of starting a company – but with the rules, regulations, and limitations that apply to a member of the House of Representatives (or the Senate). Member-elect Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D) of New York captured the feeling in an instantly viral video, posted the day before orientation was set to start, that shows her sliding quarters into a washing machine.

“The thing that most people don’t tell you about running for Congress is that your clothes are stinky all the time, because you never have time to do laundry. So this is what I’m up to this morning,” the youngest woman to ever win a seat in Congress tells her 700,000 Instagram followers. “Congressional life getting off to a glamorous start.”

Locking down logistics in the first few weeks – signing up for health care, setting up official websites and email addresses, and attending workplace training sessions – assures a better chance of a smooth transition after the swearing-in on Jan. 3, and could mean the difference between an effective first term in office and a fruitless one. That means, above all, putting together a strong staff early on, with a good mix of experienced Washington hands and people from the district.

“I always tell new members, ‘This group has more influence in your success than any other group of Americans,’ ” says Brad Fitch, president and chief executive of the nonprofit and nonpartisan Congressional Management Foundation, which has been training new members and staff since 1977. “This is a marathon, not a sprint.”

Still, there is also a kind of magic to the office. Ilhan Omar of Minnesota, who will be one of the first two Muslim women to serve in Congress, says she was taken aback when she saw civil rights icon Rep. John Lewis (D) of Georgia at one of the many dinners hosted for the members-elect.

“I was almost in tears,” Congresswoman-elect Omar (D) says. She doubts the sense of wonder will fade anytime soon. “I’m constantly walking around recognizing how beautiful it is for us to be here with so many historical firsts, and to serve with a lot of historical firsts as well.”

Week two of orientation begins the Tuesday after the Thanksgiving holiday. Members-elect will once more check into the Courtyard Marriott-Navy Yard here in Washington, where they stayed during the first week. On the Hill, they’ll break into smaller groups for briefings, show up for photo ops, and on Nov. 30, join in the lottery for their assigned office spaces.

In the meantime, meet some of the new House members of the 116th Congress:

Lucy McBath (D), Georgia’s Sixth District

In 2012, Lucy McBath’s teenage son, Jordan Davis, was shot and killed in an SUV parked at a Florida gas station – the result of an argument with a white man over the volume of music playing out of Mr. Davis’s car. His death led Ms. McBath to become a national spokesperson for Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America, to testify in a Senate hearing against Stand Your Ground laws, and to take part in an HBO documentary about Davis’s murder.

But her bid for Congress was about more than just gun control.

Running on a broad platform that included addressing climate change, expanding Medicaid, and funding public education, McBath defeated GOP Rep. Karen Handel in one of the most closely watched races of the season. In doing so, she flipped a longtime Republican seat – the same one former Speaker Newt Gingrich held for 20 years – and helped strengthen Democrats’ incursion into GOP-held suburbs. She is also the first African-American to represent the district.

Sharice Davids (D), Kansas’s Third District

On the surface, Sharice Davids seems like a Democratic avatar for the 2018 campaign season. A former mixed martial arts fighter, she’s the first openly gay representative to serve from Kansas, and one of the two first Native American women elected to Congress. And there’s no doubt she rode a wave of anti-Trump sentiment that helped Democrats regain the majority in the House.

Yet Ms. Davids, who defeated GOP incumbent Kevin Yoder by nearly 10 points, is also among a number of Democrats who ran on a promise of pragmatism and bipartisanship to win in a swing district. Instead of focusing on potential investigations into President Trump’s administration, she highlighted her commitment to protecting health care, her mother’s Army service, and her ability to both fight for progress and build consensus.

“I … think it’s kind of irresponsible to say, before I even get through orientation, to say yes or no on any piece of legislation that might come up,” Davids told McClatchy DC after the election. “I feel like I’d really have to see what is on the table.”

Gil Cisneros (D), California’s 39th District

Another group to have made strides this cycle: Latinos. From Ms. Ocasio-Cortez and Antonio Delgado in New York to Veronica Escobar and Sylvia Garcia in Texas, Latino candidates have broken new ground, mostly as Democrats.

Gil Cisneros stands out as having run – and won – in one of the nation’s closest races and against another potential history-maker in Republican Young Kim, who would have been the first Korean American woman to serve in Congress. A former naval supply officer, Mr. Cisneros rose to prominence after winning the California state lottery in 2010. He and his wife used funds from the jackpot to develop higher-education opportunities for Latino students and families.

On Saturday, the Associated Press declared Cisneros, a first-time candidate, the winner against Ms. Kim, who lost her early lead as the votes trickled in. The victory completed what became a Republican drubbing in California, where Democrats took six of the seven GOP-held districts that went to Hillary Clinton in 2016. In the end Cisneros won by less than 3,500 votes.

Dan Crenshaw (R), Texas’s 2nd District

The last thing Dan Crenshaw expected was to become a viral sensation. The Republican candidate was running against Democrat Todd Litton in a district that went to Mr. Trump by nine points in 2016. Pollsters had Mr. Crenshaw comfortably ahead.

Then, the weekend before the election, “Saturday Night Live” comedian Pete Davidson mocked Crenshaw’s eye patch in a widely panned segment. Crenshaw wears the patch to cover his right eye, which was blinded in an IED explosion while he was serving in Afghanistan. The episode fanned outrage over the state of the nation’s political discourse and raised familiar questions about the line between comedy and incivility.

But it was Crenshaw’s response that won him public approval. Not only did he appear in a follow-up segment on “SNL,” which reached out with an apology and an invitation to reconcile on-air. He also wrote an op-ed in The Washington Post that called on Americans to agree on basic rules for civil discourse – like focusing political attacks on ideas instead of on people.

“When all else fails, try asking for forgiveness, or granting it,” he wrote.

Pete Stauber (R), Minnesota’s Eighth District

In a cycle dominated by Democrats flipping Republican seats, Pete Stauber stands apart for having done the opposite: turning a blue district red. (Only two others – Jim Hagedorn in Minnesota’s First District and Guy Reschenthaler in Pennsylvania’s 14th – managed to do the same.)

Mr. Stauber, a St. Louis County commissioner and retired police officer, defeated Democrat and former state legislator Joe Radinovich in a campaign that featured a lawsuit that forced St. Louis County to release emails from Stauber’s government account, and ads that criticized Mr. Radinovich’s past parking and traffic violations and teenage marijuana use.

Political analysts say it was Trump’s economic policies, and his support, that ultimately clinched the race for Stauber. Where manufacturers and farmers in other parts of the country have responded to the president’s trade policies with mixed feelings, the iron mining industry of northeastern Minnesota has embraced the tariffs as a sign that Trump is keeping his promises.

Stauber is the second Republican to win the district in 71 years.

Perception Gaps

Global progress on extreme poverty still goes unnoticed

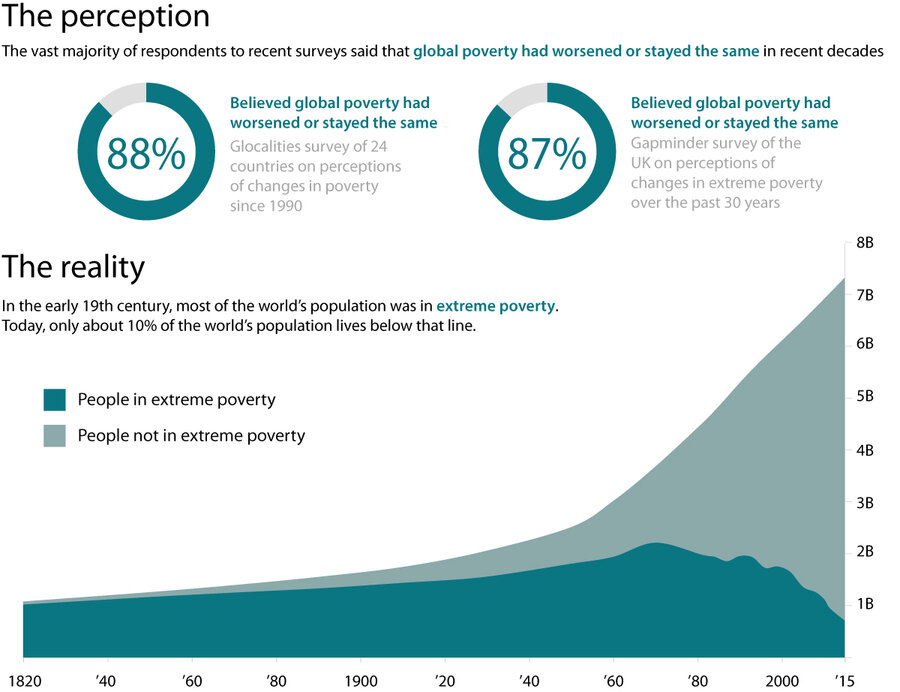

One of the most positive stories in the past 20 years has been the dramatic reduction in extreme poverty, especially in China and India. So why don't most people believe it happened? Here's the latest edition of our ongoing series: "Perception Gaps."

Around the world, tremendous progress has been made in reducing poverty. In fact, the number of cases of extreme poverty – people living on $2 or less per day – has been cut in half in the past 20 years. But surveys in 14 countries, including the United States, show 90 to 95 percent of people don’t believe it. The biggest driver of the progress in reducing poverty is the economic growth in Asia, especially China and India. The two countries, with the largest populations in the world, each had about 40 percent of their people living in extreme poverty 20 years ago. Today, India is at 12 percent, and China has less than 1 percent of its people living on $2 or less per day. Another big contributor, according to the World Bank: more investment in education and health care for girls and women. Why isn’t that progress more widely understood? “You could have a headline every day for the past decade or more saying, ‘Good news: 137,000 people have moved out of extreme poverty today.’ The problem with that is you don’t really get those sorts of headlines,” says Bobby Duffy, a social researcher and author of “The Perils of Perception: Why We’re Wrong About Nearly Everything.” For most media, “it’s much more about the tragedies,” he says, “rather than those stories of improvement.”

To listen to this episode, visit csmonitor.com/perceptiongaps.

Glocalities; Gapminder; Our World in Data, based on World Bank and Bourguignon and Morrisson

China sprints toward next sports goal: half a billion weekend warriors

During decades of intense economic growth, many Chinese feel wellness – both personal and environmental – was put on the back burner. Today, balance is actually being written into national goals.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Think about consumer culture in China, and you might picture luxury bags and watches. But what about running shoes and road bikes? Over the past decade, the country’s middle class has embarked on a fitness renaissance, with spending on sports apparel poised to surpass that on luxury goods by 2020. Meanwhile, the government is incentivizing investment and pumping up spending for athletic facilities and infrastructure. Related policies call for 20,000 soccer schools and a sports industry worth $720 billion. Yet ambition is sometimes boxed in by obstacles unique to the world’s fastest-growing major economy, such as pollution. There are basic limitations, too, like space and lack of coaches. “Balancing work, body, and mind was always part” of the Chinese consciousness, says Henry Shen, McCann Health’s chief strategy officer for Greater China. The Chinese elders dancing and performing tai chi in every park are proof, he says. “It just got lost during the fast development of the economy.” Even now, he remembers first walking by the yoga studio he now belongs to and being struck by its slogan: “Slow is the new fast.”

China sprints toward next sports goal: half a billion weekend warriors

Steeling herself against a light drizzle, Linda Liu corrals herself into Area E at the Shanghai Marathon starting line, mobile phone strapped to her upper arm.

Around the first bend, traditional tanggu drummers dressed in red and gold await the race start, their steady beats ready to echo the pitter-patter of the 25,000 runners who would flow past.

The start of the Shanghai Marathon is pure aspiration, like the majestic skyline of the Bund waterfront where it begins, home to city’s most iconic buildings and modern skyscrapers.

In the two decades since launch, the Shanghai Marathon has come to attract top athletes from overseas, alongside the thousands of Chinese who managed to draw a race number.

“I’m ready. I feel carefree,” Ms. Liu says. The property manager has no hope of placing, but something to prove to herself: “That I can run an entire marathon.”

Over the past decade, China’s middle class has embarked on a fitness renaissance, with spending on fitness apparel poised to surpass luxury goods by 2020. That’s a seismic shift in a country where urban consumers nursed a Prada obsession for years. Now, it’s running shoes and road bikes. About 75 percent of urban Chinese participate in sports and fitness, driven by newfound health awareness, social media, and the marketing reach of the behemoth $300-billion fitness industry.

Individual athletes aren’t the only ones with something to prove. As China launches onto the world stage, the next phase of its evolving quest encompasses sport: from high-profile international events to ambitious plans to produce legions of student-athletes. Yet those campaigns must overcome obstacles unique to the world’s fastest-growing major economy, such as pollution and an education culture that often prioritizes mind over body.

“Balancing work, body, and mind was always part” of the Chinese consciousness, says Henry Shen, McCann Health’s chief strategy officer for greater China. The Chinese elders dancing and performing tai chi, fixtures of every park in China, are proof, Mr. Shen says.

“It just got lost during the fast development of the economy,” he says. Shen himself is a member of yoga studio Y+. The club’s slogan immediately struck a chord as he walked by years ago, he says, wonder in his voice even today as he recalls it: “Slow is the new fast.”

Indeed, “fast” has been the norm for a country accustomed to double-digit growth. But as middle-class consumers have come into money, they’ve begun trading in luxury logos for a status symbol that calls for more than plunking down a bundle of renminbi notes.

“Twenty years ago, young Chinese were about making money and surviving, building up their lives and learning English,” says English ultramarathoner Harriet Gaywood, who notes that over her two decades living and training in China, she’s joined by more and more Chinese athletes. “Today it’s about becoming healthy.”

That desire for fitness is helped along by that disposable income, enabling sports and access in a powerful combination. As the Chinese spend money on fitness memberships, sports equipment, and private cars, new sports come within reach: swimming, Pilates, even trail running in the countryside.

Dropping the ball?

Meanwhile, the government is placing its heft behind fitness, incentivizing investment and pumping up spending for facilities and infrastructure.

In 2014, the State Council issued File No. 46, which boldly declared a plan to anoint China’s sports industry tops in the world. The Council tied the health of the people to development of the country and economy, and it also slapped a number on the goal: a sports industry that would be 5-trillion-renminbi strong ($720 billion), with half a billion participants by 2025.

Several dozen policies followed, including a vision for a national soccer team to compete at the highest levels by 2050, with a pipeline of 30 million young players and 20,000 soccer schools.

“China feels it needs to be on the world stage, and you need a plan to do that,” says Jeffrey Wilson, chair of the board at Active Kidz Shanghai, a community team sports organization.

Schools also play a role, with required physical education classes raising “the importance of fitness to the will of a nation,” said Kobe Li, a sports administrator at a Shanghai kindergarten.

Yet ambition is sometimes boxed in by the most basic of limitations: space. As developers erected Chinese cities skyward, planning officials neglected to devote open space and parks for sport. Where a precious patch of grass does exist, battles ensue over its usage. “Security guards always shoo the kids away when they play ball,” one Shanghai parent said of the tennis court-sized lawn shared by 1,000 residents in her complex.

“They say they want to protect the grass.”

Then there’s the problem of trainers. “Local schools are under pressure to provide more, but they often don’t have the venues or the coaches,” says Wilson of Active Kidz. China lacks the pipeline of volunteers to pick up the slack, but that’s slowly changing. Wilson is starting to find talent in unexpected places. “Fudan University has a baseball team, did you know?” he says, speaking of the Shanghai school that is one of China’s best. “We have had some parents who played baseball there, and now they want their kids to start earlier.”

Pollution also limits time spent outdoors — at least a few times a month, Ms. Liu cancels workouts after checking the air quality index — while an education-steeped culture prioritizes intellectual achievement. One runner said he can only take his daughter for a workout after he checks her homework load, which for Chinese students is double the global average at nearly three hours daily.

Chinese cultural beliefs can work against running fast or sweating hard, too. “Don’t go to public places too often. Exercise, but not too strenuously,” trumpeted a development guide used by Shanghai kindergarten teachers.

Sometimes, government officials foil the very sporting ambitions they aim to promote. Early this month, ticket sales to the national soccer championship game in Shanghai were shut down over security concerns. About half the 60,000 seats were left empty.

One step at a time

Yet China’s No. 1 sport doesn’t need equipment or even stadiums. Running, according to a 2017 Nielsen survey, is becoming a national pastime. The number of races held nationwide is expected to reach nearly 2,000 by 2020, a doubling in just three years, according to the Chinese Athletic Association.

For Ms. Liu, back at the Shanghai Marathon, her running aspirations had started small – piqued by WeChat, China’s ubiquitous messaging platform.

“A friend posted a snapshot of his stopwatch; he did 10 kilometers [6.2 miles] in 56 minutes,” she laughed, speaking to me at a teahouse in Shanghai a week before the race. “I thought I could do better. He runs on flats — I’ve been practicing on slopes.”

Ms. Liu was right. She immediately took to jogging in her pink Adidas, already broken in from 6 a.m. group workouts she started. Within a few months, she’d bested her friend. The Chinese might say her heritage was a competitive advantage; she hailed from Hunan province, known for its steep terrain and a history of producing some of China’s hardiest soldiers.

The day of the marathon, Linda felt unwell, while the race route itself was beset by rain. “There were puddles. I feel a little regretful — I was trying to finish in four hours,” Linda said later, of her finishing time that exceeded her goal by six minutes. “I’ll take two days off, and head back to [training].”

Shanghai entrepreneur Larry Yin sent messages after the race filled with happy-face emoticons. “I completed the marathon slowly and safely,” he said, in a “humblebrag” for his fastest time yet. While training over the past few years, Mr. Yin had lost 90 pounds, a remnant of his management consulting days, and he’s run five marathons now.

Yet he’s most proud to educate his 10 year-old daughter about the importance of fitness. “She sees her daddy get up every day and run, whether it’s winter, summer, fall, or spring,” Mr. Yin says. “That’s what I want to pass to her.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A Mexican plan to cut homicides by doing good

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Mexican President-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador, or AMLO, has a plan to cut the country’s high crime rate. It includes stronger enforcement. But AMLO also hopes to bring a wholly different approach. “Evil needs to be faced with good,” he says, “and the causes of violence must be addressed.” Many Mexicans voted for AMLO because he offered alternatives on both crime and corruption. Proposals range from creating jobs for young people to forgiving criminals who confess and make amends. There are significant concerns to work through. Yet with a country rife with criminal insurgencies and weak institutions, a multi-pronged approach is needed. The most novel idea: a new national guard that would carry out law enforcement duties as a “service” of the armed forces. (There are massive challenges to training military personnel for civilian law enforcement.) It behooves the United States to deepen its cooperation in this new struggle to curb crime in Mexico. Both countries may be ready to try new ideas. Both can win with an approach that deals with root causes.

A Mexican plan to cut homicides by doing good

Even before he takes office Dec. 1, Mexican President-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador, or AMLO, has presented a plan to cut the country’s high crime rate. Homicides in Mexico have hit new records in 2017 and are headed higher in 2018, while many other crimes have intensified across the country.

While the plan includes stronger enforcement, AMLO also hopes to bring a wholly different approach, or as he describes it: “Violence can’t be faced with violence; fire can’t be put out with fire, and you can’t confront evil with evil. Evil needs to be faced with good, and the causes of violence must be addressed.”

Mexico may have no alternative. For more than a decade, the federal government has been unable to devise an effective strategy to stop the spread of crime, More than 200,000 people have been murdered, according to official estimates.

Many Mexicans voted for AMLO because he offered alternatives on both crime and corruption. Under outgoing President Enrique Peña Nieto, criminality spread widely, going far beyond drug smuggling. The law enforcement and justice systems failed. The government’s inability to arrest and convict criminals effectively gave them impunity and encouraged more crime. Corruption was too rarely prosecuted.

AMLO’s proposals range from creating jobs for young people to legalizing some drugs to forgiving criminals who confess and make amends. Popular expectations for the plan are high. There are significant concerns to work through and to be debated. Yet with a country rife with criminal insurgencies and weak institutions, a multi-pronged approach is badly needed.

Some of his ideas are still too vague, such as promoting family values and civic culture. And it is not clear which drugs he would legalize or how cartels would be demobilized and reintegrated into society. Others are more obvious, such as improving the conditions and security at prisons.

The most novel idea is a new national guard, which would carry out law enforcement duties as a “service” of the armed forces. Staffed by Army, Navy, and federal police, the new service would initially total 50,000 members, but could grow to three times that size. The Constitution will need to be changed to permit the use of military personnel for local law enforcement. And there are massive challenges to train them for civilian law enforcement and to integrate them with a more effective justice system. Also in doubt is whether federal forces should intrude on the sovereignty of Mexico’s states.

AMLO would do well to make sure his approach is compatible with the demands of the United States to counter more effectively the massive flow of illegal drugs across the border. It also behooves the US to deepen its cooperation in this new struggle to curb crime in Mexico. Both countries may be ready to try new ideas. Both can win with an approach that deals with the root causes of the violence as well as providing better solutions for improving security and rule of law as quickly as possible.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

‘Give us this day our daily bread’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

While there’s still work to be done, in recent years much progress has been made in reducing poverty around the globe. Today’s column includes a poem and quotes that point to God’s unending supply of love and care for His children.

‘Give us this day our daily bread’

Come, Thou all-transforming Spirit,

Bless the sower and the seed;

Let each heart Thy grace inherit;

Raise the weak, the hungry feed;

From the Gospel, from the Gospel

Now supply Thy people’s need.O, may all enjoy the blessing

Which Thy holy word doth give;

Let us all, Thy love possessing,

Joyfully Thy truth receive;

And forever, and forever

To Thy praise and glory live.

– Jonathan Evans, “Christian Science Hymnal” (1932), No. 42

“Your Father knows the things you have need of before you ask Him.”

– Christ Jesus, Matthew 6:8, New King James Version

“God gives you His spiritual ideas, and in turn, they give you daily supplies.”

– Mary Baker Eddy, “Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 307

A message of love

Making his mark

A look ahead

That’s it for us today. We're keeping an eye on the stock market, which has now lost all its gains in 2018. Be sure to join us tomorrow when we take a look at how Congress, dissatisfied with events in Yemen and Saudi Arabia, seems poised to reassert its role in setting US foreign policy – and how far it might go.