- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- As more citizens reach for the web, more leaders reach for the ‘off’ switch

- Can Democrats prevent shutdowns by refusing to ‘reward’ the tactic?

- Marijuana revenue benefits schools – but its impact is limited

- Negro Mountain? Why offensive place names are still on US maps.

- A life as art: How this painter helps others see differently

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Two things we know about the Covington viral video

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

There are a few things we can say pretty clearly about the National Mall protest videos that have turned America’s umbrage meter to 11.

The first is that what you see is likely determined by who you are. Is a group of possibly racist Catholic high school students in “Make America Great Again” hats intimidating Native American protesters? Or are liberal sensitivities running amok, turning every perceived slight into a social media emergency?

The answer, as one story in the Atlantic argues, largely depends on “where you live, who you voted for in 2016, and your general take on a list of other issues.” This is what polarization looks like. When the country is so neatly sorted into two camps, everything is fuel for culture wars.

That leads to a second takeaway. All this makes us easier to manipulate. CNN is reporting that Twitter shut down the account that pushed the video viral. But even if a foreign troll isn’t responsible, there’s a warning. Videos do not establish fact. They convey the viewpoint of the person behind the lens. In an age when smartphones make us all videographers, that’s an important warning. “Above all,” the Atlantic author writes, “I’ll try to take the advice I give my kids daily: Put the phone down and go do something productive.”

Stay tuned to our coverage in coming days. Staff writer Christa Case Bryant is headed to Covington, Ky., the hometown of the boys in the protest, to see how the story looks from there.

Now, here are our five stories, which range from how “principle” is playing out in Congress to why racist place names can hang around for so long. We also look at how states are spending their windfall from legal pot. Is it doing what was promised?

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

As more citizens reach for the web, more leaders reach for the ‘off’ switch

The more the internet becomes entwined with personal agency and freedom, the more African leaders are looking to shut it off in times of crisis. That can have unintended consequences.

-

By Wendy Muperi Contributor

-

Ryan Lenora Brown Staff writer

One month into 2019, and three governments in Africa have already shut off the internet. It's an increasingly popular tool for leaders cracking down amid contentious elections or protests. Last week Zimbabwe, where security forces have been accused of torture and at least a dozen people have been killed in demonstrations, became the latest to experience blocked-off websites and apps. A decade ago, only 4 percent of sub-Saharan Africans were connected to the web. Today, one-quarter of them are, the fastest growth in the world. “The rising number of users is posing an ever bigger threat to governments,” says Juliet Nanfuka, a researcher in Uganda. In many countries in Africa, the rise of mobile phones and internet usage has facilitated the rapid spread of mobile money. In Zimbabwe, for example, more than 95 percent of financial transactions are now electronic – meaning the internet restrictions’ effect is felt quickly by those who oppose and those who support the administration alike. “You value your rights more once you see that they can be taken away from you,” says Ms. Nanfuka. “So the silver lining here is we’re seeing more people become involved and appreciating their right to free expression and communication.”

As more citizens reach for the web, more leaders reach for the ‘off’ switch

Collecting the money should have been easy. Alice Ndlovu had done it a million times before. But when she got to the front of the queue at the bank in her hometown of Rusape in eastern Zimbabwe last Friday, the teller shook her head.

Sorry, she said. No service today.

Ms. Ndlovu, a teacher who asked that a pseudonym be used for fear of government reprisal, desperately needed that cash, which her son sent her from Britain to cover the cost of her diabetes medications. So she reluctantly handed over a few crumpled bills and boarded a bus for the nearest town with a bank, more than an hour away.

There, she walked from bank to bank, but every time the answer was the same. Sorry. You can’t pick up your money today.

Finally, a sympathetic teller saw the panic on her face and offered an explanation. Amid widespread protests across the country over a massive hike in the price of fuel, the government had decided to completely shut off the internet. That meant money transfers were down, too.

The intent of the shutdown, analysts say, had been to disrupt the protests and prevent information about them from getting to the world beyond Zimbabwe’s borders. But in a country in the midst of a severe cash crisis, where more than 95 percent of financial transactions are electronic, turning off the internet had another knock-on effect: It cut many Zimbabweans off from their only source of money.

“I started panicking and felt helpless at the same time,” Ndlovu says. No one could tell her when the internet would be back or how long she might have to live without the medications prescribed to keep her alive.

Internet shutdowns are a blunt instrument of repression, but as access to the web mushrooms across Africa, they’re also becoming a more popular one. In the first month of 2019, governments have also shut off the internet in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, and Sudan. In Chad, meanwhile, social media has been blocked for nearly a year and counting. And those shutdowns are part of a broader trend. In 2018, the internet advocacy group Access Now recorded 21 full or partial internet shutdowns in Africa, up from 13 the year before, according to the Associated Press.

The shutdowns are, in part, a reaction to the web’s growing reach in a continent that, even until a decade ago, was largely offline. Today, the internet is an increasingly essential part of the economies of many African countries, from mobile payments for daily groceries to e-commerce. But with that growth, it is also becoming a tool for social change, prompting governments to take increasingly bold moves to muzzle it – with sometimes unforeseen consequences.

“The rising number of users is posing an ever bigger threat to governments,” says Juliet Nanfuka, a researcher at the Collaboration on International ICT Policy in East and Southern Africa, an internet think tank and advocacy organization based in Kampala, Uganda. "Some governments are making good strides in their efforts aimed at getting more users online. However, alongside this is an increasingly vocal citizenry who demand rights, transparency, and accountability. In response, we see the very same states interfering with access.”

Transformative growth

Indeed, internet access is growing more quickly in sub-Saharan Africa than anywhere else in the world, according to data from the International Telecommunication Union, a United Nations agency. In 2018, a quarter of Africans accessed the internet. That’s far lower than the global estimate of 51.2 percent, but a staggering rise from a decade ago, when only 4 percent of Africans were online.

That revolution has been facilitated by the rise of another technology, cheap smartphones, which have allowed Africans to leapfrog the lack of landlines and other connectivity issues that previously put the internet out of reach of most people. The percentage of Africans with smartphones has doubled since 2014, according to a study by the Pew Research Center. And another 300 million Africans are expected to come online in the next seven years, most of them via their phones, according to the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSMA), an industry advocacy and research group.

And that access comes with massive economic benefits. In 2017, mobile technologies were responsible for 7.1 percent of GDP in sub-Saharan Africa, for a total dollar value of around $110 billion, according to GSMA calculations. In many countries, including Zimbabwe, the rise in mobile phone and internet usage has facilitated the rapid spread of mobile money, sidestepping the logistical hurdles of accessing brick-and-mortar banks to bring millions of Africans into the formal financial system for the first time.

But for governments, the rising number of internet users also means that information travels with alarming rapidity, often undermining their control. As rumors about the results of Congo’s hotly contested presidential election began to circulate in early January, for instance, the government there cut off internet and text messaging services, arguing that the spread of “false numbers” could cause a “popular uprising.”

Globally, elections are among the most common triggers for internet restrictions, according to a recent report on global internet freedom by the American think tank Freedom House.

Disrupting protests is another common target. Social media went black in Sudan in late December as an unprecedented protest movement began to rattle the 30-year rule of President Omar al-Bashir. It was the presumed reason that the internet in Gabon went down during an attempted coup in early January and for 136 days straight in 2017 and 2018 in Anglophone Cameroon, where a powerful separatist movement is active.

Often, internet blackouts during protests are veiled in the language of public safety and the protection of law and order.

"The internet was a tool that was used to coordinate the violence," explained Zimbabwean government spokesman George Charamba Saturday, defending his government’s decision to shut off the internet during a week of protests. At least a dozen people have been killed and hundreds arbitrarily arrested in the ongoing protests. The country’s Human Rights Commission has accused security forces of “systematic torture” against protesters.

"Naturally, when you are reacting to a conspiracy of that nature, you ensure that society is protected,” Mr. Charamba said. “There is no way that you expect us to sacrifice a national good for the sake of the internet."

In many ways, Ms. Nanfuka says, that’s just an old argument dressed up in a new technology.

“In the past, these same governments might have threatened newspapers or shut down radio stations to keep information from getting out,” she says. “This is the modern way of doing the same thing.”

‘You value your rights more’

But shutting off the internet can have unintended consequences, as Ndlovu’s experience trying to get her medication in Zimbabwe shows. Web shutdowns affect a regime’s sympathizers as well as its detractors, says Piers Pigou, a senior consultant for southern Africa with the International Crisis Group and an expert in Zimbabwean politics. Those who went hungry when they couldn’t access their mobile money last week, in other words, weren’t only demonstrators.

“The possible ramifications from constituencies who didn’t even participate in protests to begin with is something the government will have to take into consideration” going forward, he says.

And with so much economic activity happening on the internet, shutdowns can also leach money from economies that desperately need it. An internet blackout, for instance, costs Zimbabwe about $5.7 million a day, according to the advocacy group NetBlocks, which uses a calculation of the scope of a country’s digital economy to arrive at its figure.

On Monday, Zimbabwe’s High Court ruled that the shutdown of the internet had been illegal because it had not been directly ordered by the country’s president, Emmerson Mnangagwa, and ordered access to be restored. That mirrors a wider continental trend of challenging shutdowns through African court systems, with nonprofits filing lawsuits in Cameroon and Uganda.

But courts often move slowly, and the internet can be restricted suddenly and by only a few key individuals, making courts an imperfect tool for stopping shutdowns.

Still, Nanfuka says, resistance to internet blackouts on the continent is growing, too.

“You value your rights more once you see that they can be taken away from you,” she says. “So the silver lining here is we’re seeing more people become involved and appreciating their right to free expression and communication.”

Can Democrats prevent shutdowns by refusing to ‘reward’ the tactic?

Democrats say they are taking a stand on principle, though they themselves forced a shutdown a year ago. Whether either party tries a shutdown again will likely depend on the political fallout from this one.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

From Day One of the longest government shutdown in history, Democrats have stuck to their guns: First, open the government. Then negotiate over border security. Their unwavering message has been that shutdowns must not be rewarded as a political tool. On Thursday, Democrats will put this reasoning to a test in the Senate, where lawmakers will vote on reopening the government for the first time since the partial shutdown began more than a month ago. Senators will vote on dueling measures: President Trump’s plan, which would fund the government through September and includes $5.7 billion for a wall; and the Democrats’ plan, which would fund the government through Feb. 8 and has no wall money. Both seem destined to fail. But even if Democrats prevail, it’s far from clear that this stand would deter future shutdowns. Government closures have become weaponized, observers say, and that’s not likely to change. Indeed, just one year ago, Democrats themselves forced a shutdown, though brief, over immigration. “There are ways to fix this,” says G. William Hoagland, senior vice president of the Bipartisan Policy Center. “But given the current partisan politics, I don’t think it’s going away.”

Can Democrats prevent shutdowns by refusing to ‘reward’ the tactic?

From Day One of the longest government shutdown in history, Democrats have stuck to their guns: First, open the government. Then negotiate over border security. Their unwavering message has been that the president must not be allowed to hold federal workers “hostage” to get what he wants. Shutdowns must not be rewarded as a political tool.

On Thursday, Democrats will have an opportunity to put this reasoning to a test in the Senate, where lawmakers will vote for the first time on reopening the government since the partial shutdown began more than a month ago. Senators will vote on dueling measures: President Trump’s plan, which would fund the government through September and includes $5.7 billion for a wall; and the Democrats’ plan, which would fund the government through Feb. 8, allowing time to negotiate border security. It has no wall money.

Both measures seem destined to fail in the polarized Senate. But even if Democrats prevail in their demand, it’s far from clear that this stand would deter future shutdowns. Government closures have become weaponized, observers say, and that’s not likely to change. Indeed, just one year ago, Democrats themselves forced a shutdown, though brief, over immigration.

The Democrats’ demand to open the government first is “just part of the game,” says Patrick Griffin, who was legislative director for President Bill Clinton during the previous record-holding shutdown of 21 days. “It works until it doesn’t work,” he says. “You use it when it serves your purpose.”

The message also has served to keep Democrats unified. Not all Democrats oppose more funding for physical barriers along the border even if they object to a concrete wall.

“It’s a good argument because it’s about a fundamental framing, as opposed to a component that people may agree or disagree on,” says Democratic pollster Celinda Lake. “Plus, people overwhelmingly agree the shutdown is Trump’s fault.”

In a speech on Saturday, Mr. Trump stepped back from demanding a $5.7 billion wall as “a 2,000-mile concrete structure from sea to sea” and instead called for barriers in select “high priority” locations, in exchange for three years of protected status for “Dreamers” and certain other immigrants.

Democrats have rejected the offer, pointing out that it also would place new restrictions on asylum seekers who are minors. Despite being presented by the president as a compromise, the proposal was not made in consultation with Democrats.

Still, a group of centrist House Democrats reportedly wants Speaker Nancy Pelosi to offer the president a vote on his border wall and other security measures by the end of February, while allowing amendments to protect Dreamers – after the government is opened up. And some Democrats could support steel slats, a description that the president has been using.

“I think in some places it might be appropriate, yes,” Rep. Jahana Hayes, a Democratic freshman from Connecticut told reporters last week, referring to slat fencing. “I want the border to be secure.”

Each shutdown has its own character – including, in this case, a dispute over whether the president will give his State of the Union address in the House on Jan. 29. The president insisted in a letter to Ms. Pelosi today that he would; she wrote back that the House will not consider it until the shutdown ends.

Each shutdown also has its own political pain, and that will determine its next use as a political tool for leverage, says Mr. Griffin.

He points to the three-week shutdown over the holidays in the winter of 1995-96, when then-Speaker Newt Gingrich (R) of Georgia went to the mat to balance the budget in seven years through dramatic cuts. Mr. Clinton offered a different plan: 10 years without those cuts. In the end, Republicans were forced to admit defeat, and Clinton won reelection.

It would be more than 17 years before congressional Republicans would again trigger a shutdown, this time over the Affordable Care Act. Their approval rating plummeted after that 16-day standoff in October 2013, instigated by the tea party caucus (one of its former members, Mick Mulvaney, is now the president’s acting chief of staff). But interestingly, that drop in approval did not last, and a year later, Republicans – still vowing to repeal Obamacare – took over the Senate.

“If this has an aftermath that leaves a really bad taste with the public, I think shutdown politics will be put on a shelf for a while,” says Griffin.

Still, Griffin does not see shutdowns as “inherently evil.” Congress has the right to use the power of the purse in a system of checks and balances, he argues.

G. William Hoagland, senior vice president of the Bipartisan Policy Center, agrees – within reason. Mr. Hoagland, the former director of the Senate Budget Committee under former Sen. Pete Domenici (R) of New Mexico, says shutdowns reflect a difference of opinion between the branches, and most shutdowns in American history have been brief. On the other hand, “ones that go on as long as this one border on being very evil.” He calls today’s standoff “a dangerous game” that’s putting life and property at risk, hurting workers and the economy.

To remedy this, lawmakers on both sides of the aisle are promoting bills that would prevent future shutdowns. The bills call for automatic extension of current funding if the budget process breaks down, with various penalties for not agreeing on a new budget.

Hoagland supports this idea, which seems to come up every year. It typically faces resistance because some members feel it would take away the incentive to pass budgets at all – though as Hoagland points out, Congress is not passing budgets now, so what is there to lose?

Like Griffin, Hoagland believes shutdown standoffs are here to stay. And it’s not just shutdowns, but also the clash over the debt ceiling, which is coming later this spring and summer.

“There are ways to fix this,” he says, “but given the current partisan politics, I don’t think it’s going away.”

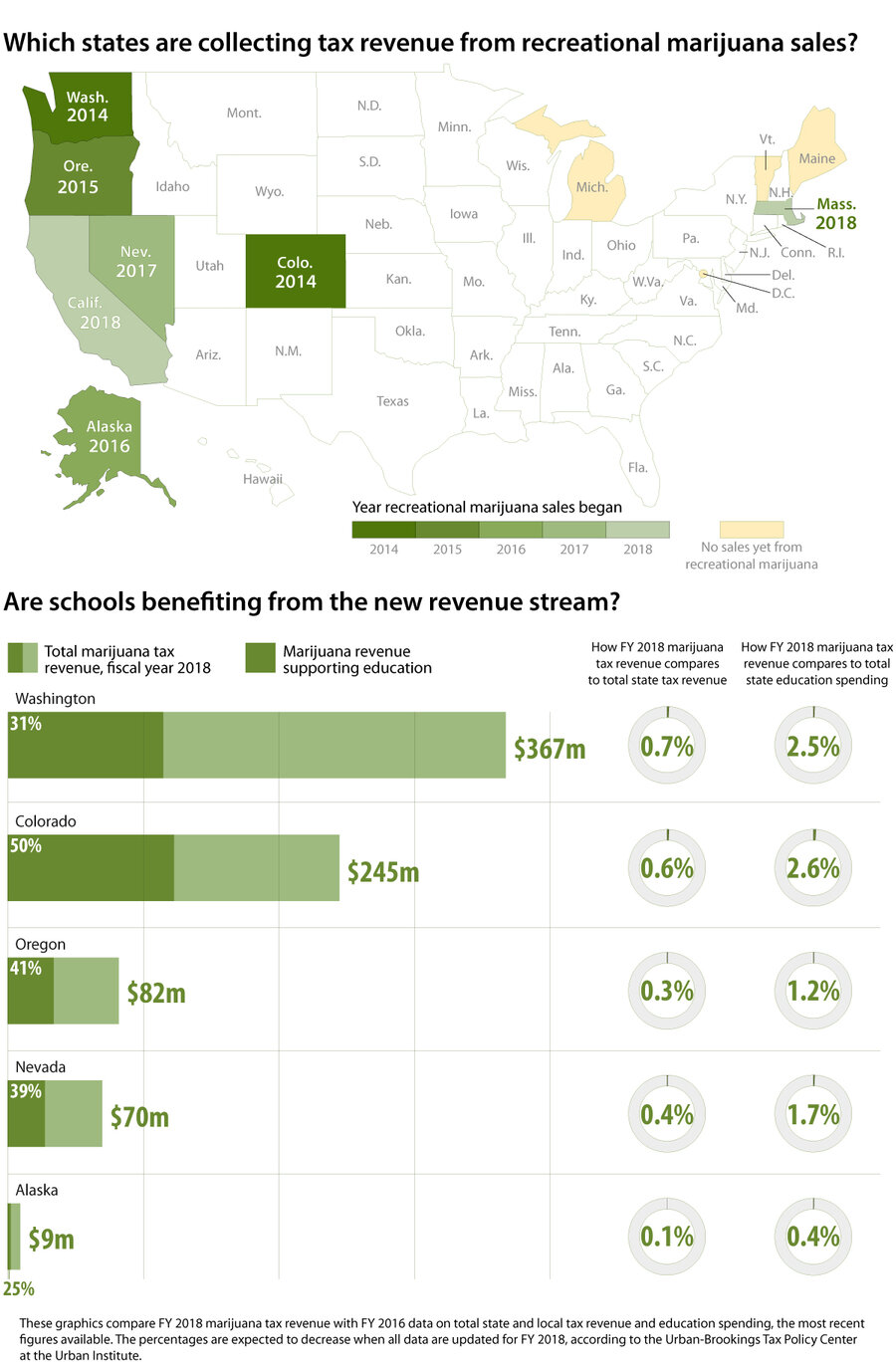

Marijuana revenue benefits schools – but its impact is limited

Legalized marijuana gives states a monetary boost. But so far, claims that it can make a big difference to school budgets have not proven true.

Legal recreational marijuana is slowly spreading across the United States, and so is discussion on how to spend the tax revenue it brings in. One frequent beneficiary: schools. Colorado, a first adopter in 2012, now reserves $40 million in marijuana revenue for the Building Excellent Schools Today Fund. In 2018, that was out of nearly $250 million collected. The money has helped replace crumbling roofs and dilapidated gyms, among other school maintenance projects in many rural districts. But from a wider budgeting perspective, says Lucy Dadayan, senior research associate with the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center at the Urban Institute, the situation is a bit more complex. Even for states with established industries, marijuana revenue makes up a tiny fraction of education spending. “The numbers speak for themselves,” Dr. Dadayan says. “[Marijuana revenue dollars] are not the budget solvers.” Instead, she argues states should save most marijuana money for financial emergencies, something Nevada already does. Observers expect local pot revenue to level off as more states legalize the drug and demand becomes less concentrated. Even so, advocates in states that have legalized recreational pot and those that haven’t, including Massachusetts, New York, and Illinois, still see marijuana revenue as one answer to funding woes in public schools. – Noble Ingram

Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center at the Urban Institute, Alaska Office of Management and Budget, Colorado Department of Revenue, Nevada Department of Taxation, Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board, Oregon Department of Revenue

Negro Mountain? Why offensive place names are still on US maps.

What’s in a name? When that name is Runaway Negro Creek, a lot of mythology, and racism, masquerading as history. How a no-brainer got complicated, and how some communities are seeking change.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Strewn alongside more widely known geographical place names like Hoover Dam and Mount Rainier are names that may come as a shock to many: Runaway Negro Creek, Squaw Humper Dam, Negro Mountain. What’s more shocking, while some have been renamed, many have not – and efforts to change some names, like Runaway Negro Creek, in Georgia, have been met with resistance. The challenge shows how what seems like a simple process can become mired in red tape and politics. Names like “Negro” and “squaw” reveal a nation struggling to reconcile the nomenclature of the past with the sensibilities of a polyglot future. Certainly, efforts to cleanse America’s geographical lexicon have erased hundreds of pejorative waypoints. There are 215 uses of “Negro” currently on maps across the US, down from more than 750 in 2011. But many crude names remain. As Karen Blanar, who works in the Pennsylvania state legislature says, “I could talk about [renaming places] for over a day, easily, without even blinking, and I would barely scratch the surface of how complicated it is, which is funny, because at first look it seems a no-brainer.”

Negro Mountain? Why offensive place names are still on US maps.

For decades, Runaway Negro Creek was nothing more than a local high-tide cut-through to avoid the “no wake” zone along the yacht docks at historic Isle of Hope.

In antebellum times, however, the oyster-specked backwater was, according to island lore, an escape route for African slaves from the nearby Modena rice plantation. Others say it may have been named for escaped chain gang convicts in the Jim Crow era.

Either way, it seems a total no-brainer to turn what Savannah, Ga., resident Mack Richards, a white 20-something, calls “a tasteless name” on its head and instead call it “Freedom Creek,” as the Republican-led Georgia legislature voted wholeheartedly to do last March. Nixing the name Runaway Negro Creek “is just common sense, which of course isn’t always common,” says Mr. Richards’s friend, Jason Burns, who is black and also in his 20s.

“Intentional or not,” Senate Resolution 685 reads, “the current name of such creek serves to cast, edify and perpetuate a posture of criminality upon the men and women who pursued the inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Yet nearly a year later, Runaway Negro Creek remains on federal maps.

The bid shows how what seems like a simple process can become mired in red tape, politics, and the tangle of myth versus fact. Names like “Negro” and “squaw” on bogs and peaks reveals a nation struggling to reconcile the nomenclature of the past with the sensibilities of a polyglot future.

“Most of us don’t know American history; we know American mythology, and we pass that mythology on and people take it and run with it,” says Amir Jamal Touré, a history professor at Savannah State University. “But when folks say we’re revising history, we are not; we are correcting history. And in doing so we abolish the mythology.”

‘Times have changed’

Certainly, a broader effort to cleanse America’s geographical lexicon has erased hundreds of pejorative waypoints, including Negroedge Canyon and Squaw Humper Dam.

Georgia’s landscape once was pocked with N-word references. Today, while the N-word has disappeared from names, Georgia still has eight place names with Negro in them, including Negro Head Branch, according to the federal Geographic Names Information System.

There are 215 other uses currently on maps across the US, according to some estimates, down from more than 750 in 2011. Most of the stragglers are in the Mountain West, its remoteness and relatively white demographics leaving fewer eyebrows to be raised.

Currently, the United States Geological Survey’s Board on Geographic Names – made up of representatives from all 50 states – meets quarterly to make final decisions on changing geographical place names on official federal maps, leaning heavily on local stakeholder groups for guidance.

The struggle here in Georgia’s marshes involves determining what really happened, why it happened, and how to sanitize the stains of white supremacy without erasing what many say are the hard elbows of history.

“This has been happening all across the US,” says Steven Engerrand, Georgia’s just-retired deputy state archivist. “People used to name all sorts of things that looked like this or looked like that, and the names [remain] on the land regardless of the fact that times have changed.”

Renaming gets political

Places nearest to the heavens, it turns out, may be the toughest to rename.

In 2015, President Barack Obama changed Alaska’s Mount McKinley, the highest point in North American, to Denali, finalizing a century-long campaign to officially change it back to its ancestral name. Calling the decision a great insult to Ohio – the birthplace of William McKinley and a key swing sate – President Trump vowed to change it back. He has so far not delivered on that vow. In a 2017 meeting, Alaska’s two Republican senators urged the president not to re-re-rename it, arguing that native Athabascans have referred to the 20,310-foot peak as Denali for 10 millennia.

In 2016, South Dakota’s own Board of Geographic Names successfully lobbied to rename the tallest peak in the state Black Elk Peak, relegating Harney Peak to the history books. Black Elk was a well-known Lakota medicine man; Gen. William Harney’s troops killed Brulé Sioux women and children during the Battle of Blue Water Creek in Nebraska. The change was so controversial that angry lawmakers nearly disbanded the board.

But even patently offensive names can be surprisingly difficult to dislodge.

Pennsylvania and Maryland remain locked in a nomenclature battle with Allegheny area residents over Negro Mountain, a shoulder of quartzite that straddles state lines.

Negro Mountain is named for a hero. But legislation to rename it Mount Nemesis for an African-American scout who reportedly died while bravely defending a party of settlers against a Native American attack has failed again and again since 2013 – a victim of “our current politics,” argues one legislative aide.

“I could talk about [renaming places] for over a day, easily, without even blinking, and I would barely scratch the surface of how complicated it is, which is funny, because at first look it seems a no-brainer,” says Karen Blanar, leadership executive director for Pennsylvania state Rep. Rosita Youngblood.

Here on the Isle of Hope – one of the wealthiest corners of Georgia – lifelong resident James Sickel is waging a campaign that is likely to snag the process even more. His research suggests that no escapee ever splashed down the creek. Instead, the name was likely a mean-spirited suggestion by white local officials for a 1906 dredging map.

The retired Murray State University biology professor and amateur historian has looked down on the mouth of the creek his entire life, embarrassed by the name. Dr. Sickel has suggested a “nonpolitical” replacement: Burnt Pot Creek, for nearby Burnt Pot Island.

“The Freedom Creek name, to me, is based on a narrative without evidence that any slaves actually escaped through that creek to freedom,” says Sickel. “So in my mind, that name perpetuates a narrative that’s not true or may not be true.”

And therein is the conflict the Board on Geographic Names will have to contend with when it reconvenes in March: Will the broader public’s desire to make a statement win over local desires?

Dr. Touré, of Savannah State, is confident that Freedom Creek will ultimately prevail. The new name, he says, conveys an idea larger than the little creek itself: that “Africans sit at the table of humanity as equals, not beggars.”

Difference-maker

A life as art: How this painter helps others see differently

Internationally acclaimed artist Paul Goodnight uses his paintbrush to help communities see their issues in a new light. And that, he says, can be uniting and healing.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

As a painter, Paul Goodnight strives to convey the beauty of the African diaspora. But his work is more than that: Describing himself as a “citizen first and then an artist,” he uses his paintbrush to tell the stories of communities and present their issues in a new light. After he was drafted into the Vietnam War, he returned so traumatized by the violence that he was rendered speechless. So to cope, he created a voice for himself through art. One of Goodnight’s first major public works was created in 1982, at Lincoln-Sudbury Regional High School, where racial tensions were simmering. Goodnight teamed with the black and white students to draw their learning experiences growing up. The result was a mural titled “Education in a Different Way.” And Goodnight has also focused on practicalities: the need for artists to develop business skills. During the early 1990s he and others founded Color Circle Art, which teaches young aspiring artists business skills. Goodnight’s calendar brims with projects. “You’re never done with anything you love,” Goodnight says. “Love continues to grow within you. How can you be done with anything like that?”

A life as art: How this painter helps others see differently

Inside Paul Goodnight’s art studio, hundreds of vibrant paintings fill the space from floor to ceiling. In each one, black bodies appear to move in intricate ways, and washes of color fill the canvases like spots of colored lights at a disco.

As a painter, Mr. Goodnight strives to convey the beauty of the African diaspora. But his work is more than that: Describing himself as a “citizen first and then an artist,” he uses his paintbrush to tell the stories of communities and present their issues in a new light.

Goodnight has gained recognition for his socially conscious work, which spans decades and continents. He has brought students together at a school that was struggling with racism, mentored young artists, and even aided Sierra Leone refugees in coping with trauma from war.

“I feel like images can help tell a story. And not only help tell a story, it can also benefit the community in a way that they had never thought of before,” says Goodnight as he sits in his Boston studio wearing his signature paint-splattered overalls and a do-rag tied over dreadlocks.

Goodnight grew up in the South End of Boston in a large African-American family. As a young boy, he developed a passion for painting and drawing. In fact, once when he was sent to his room for misbehaving, he was excited because it was a chance to draw.

But as he became an adult, his passion had to be put on hold because he was drafted into the Vietnam War. He says that when he returned, he was so traumatized by the violence he had witnessed that he was rendered speechless. So to cope, he created a voice for himself through art.

Over the years, Goodnight’s work has resonated with the African-American community, so much so that his paintings have found their way onto the sets of TV shows such as “Martin” and “Living Single” and into the private collections of celebrities including actor Wesley Snipes and basketball Hall of Famer Isiah Thomas. In the art world, his paintings have hung in the Smithsonian, the Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists (NCAAA), and the National Museum of Ghana, to name a few.

Goodnight has traveled to and lived in a variety of places, including Sierra Leone, Russia, China, Uganda, Senegal, and Brazil. Many of these locales have become home.

“[Goodnight’s art] has an international flavor to it, directed more specifically toward black culture,” says longtime colleague and Boston activist Sadiki Kambon, who worked with Goodnight to create a T-shirt design for the Boston contingent of the Million Man March in 1995. “It’s significant to me because it highlights the importance of our culture and particularly our family and our ancestors.” He adds, “You get a sense of pride when you see the work that Paul does. It makes you feel good about who you are as a black person.”

Community artist

One of Goodnight’s first major public works was created in the Boston area. In 1982, he had undertaken a three-month teaching residency at Lincoln-Sudbury Regional High School, where racial tensions were simmering between some black students and a predominantly white student body. Wanting to help, he stepped in with some buckets of paint.

Goodnight and the black and white students teamed up to draw their learning experiences growing up. The result was a mural titled “Education in a Different Way.”

“It was uniting because the black students and the white students were working together again, and they were working together on something positive and not negative,” Goodnight recalls.

He was selected to design commemorative posters for the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta and the 1998 World Cup in France. His work won him a Sport Artist of the Year Award from the United States Sports Academy in 1996 and a 21st Century Award from the Urban League of Eastern Massachusetts, among others.

Edmund Barry Gaither, director and curator of the Museum of the NCAAA, says Goodnight is at the forefront of an important tradition in 20th-century African-American art. “What he does ... normalizes [the] black experience and its representation.... Paul, over his career and given the consistency with which he has been interested in this subject matter, really is the [newer] generation figure substantially moving forward,” Dr. Gaither says.

Art as a healing agent

Goodnight’s experience in the Vietnam War is also a big factor in his work. Namely, he uses art to heal the emotional scars of violence. When a friend suggested he participate in a service trip to Sierra Leone several years ago to help people who had endured amputations because of the civil war, he jumped at the chance.

With art serving as a form of therapy, the survivors drew their experiences. And Goodnight offered to paint their portraits, with one condition: They had to tell him their stories.

In his Boston studio, Goodnight pulls out a small stack of papers held together by a paper clip. It’s a makeshift journal written by a 13-year-old boy with detailed drawings of the civil war. On one page, a man holds a machete to a woman carrying her child.

The woman is the boy’s mother, who eventually lost her legs in the battle to save his life.

Tucked in the stack of papers is a photo of the mother sitting in a wheelchair with both of her legs amputated. She sits proudly next to her son, who is all grown up.

“He said, ‘I’m going to give you this picture of [my] mother ... and I know you’re the right person to give it to,’ ” Goodnight recalls.

Touched by the man’s trust in him, Goodnight painted a picture, which he says he donated to Hampton University in Virginia as part of an effort to raise money for the man’s siblings to come to the US for an education.

Over his career, Goodnight has also focused on something more mundane yet important: the need for artists to develop business skills. So during the early 1990s he and others founded Color Circle Art, which teaches young aspiring artists business skills like reading contracts and understanding commissions. The organization also funds scholarships and grants.

One of the first people Goodnight mentored is Iropa Keinkede, who took sketch classes with him. Goodnight quickly recognized his potential and funded him to take classes at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in Boston. Mr. Keinkede hopes to pursue comic book art and like Goodnight wants to create a dialogue around race.

“He’s a great teacher.... I like the way he draws: It just reminds me of comics drawings,” Keinkede says. “We need good imagery of African-American people ... and it’s good to see that. A lot of comics that I read are of white people.”

Goodnight’s calendar brims with projects, collaborations, and art classes. He is taking a sculpture class to continue learning new ways to tell stories, and along with another artist, he is working on a statue of social reformer Frederick Douglass that is to be placed on Boston’s Tremont Street.

“You’re never done with anything you love,” Goodnight says. “Love continues to grow within you. How can you be done with anything like that?”

• For more, visit goodnightart.biz.

Three groups with an arts component

UniversalGiving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations around the world. All the projects below are vetted by UniversalGiving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause.

• Shirley Ann Sullivan Educational Foundation improves the quality of life for children by providing education and lobbying for their protection from exploitation.

• Light and Leadership Initiative responds to the needs of women living in part of Lima, Peru. Take action: Donate money for a music initiative at this group’s teen center.

• Sanaga-Yong Chimpanzee Rescue provides sanctuary for orphaned chimpanzees in Cameroon while supporting habitat protection and other measures. Take action: Help pay for a five-day classroom program that focuses on environmental stewardship and includes interactive art.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Forgiveness as a peace tool in Venezuela

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Venezuelans took to the streets Wednesday to demand an end to the regime of Nicolás Maduro, who remains president in name only after rigging his own reelection last year, and who now relies on the military to stay in power. Yet the opposition knows protests are not enough. In past demonstrations, hundreds have been killed by the armed forces – kept loyal by economic favors from Mr. Maduro. Now the opposition has come up with a new and perhaps more powerful tool: It is offering forgiveness to members of the military who switch sides. The new leader of the National Assembly and of the opposition, Juan Guaidó, says he is not looking for a coup. The offer of mercy is based on individual soldiers simply ceasing to recognize Maduro’s legitimacy. Offers of mercy can be effective in countries torn by civil strife. Reconciliation relies on a process of contrition, forgiveness, and renewed affection. The bond that must be restored in Venezuela is mutual respect for constitutional order. The real protests in Venezuela may be happening in the hearts of currently silent soldiers.

Forgiveness as a peace tool in Venezuela

By the hundreds of thousands, Venezuelans took to the streets Wednesday to demand an end to the regime of Nicolás Maduro. He has become president in name only after rigging his own reelection last year and now relies more than ever on the military to stay in power. Yet the opposition knows protests are not enough. In past demonstrations, hundreds have been killed by the armed forces – kept loyal by economic favors from Mr. Maduro.

Now the opposition has come up with a new and perhaps more powerful tool. It is offering forgiveness to members of the military who switch sides.

On Jan. 15, Venezuela’s only legitimate political body, the duly elected National Assembly, approved a measure offering amnesty to soldiers who “contribute to the defense” of the Constitution.“We need to appeal to their conscience and create incentives for them,” said one opposition member, Juan Andrés Mejía.

The new leader of the National Assembly and of the opposition, Juan Guaidó, makes clear he is not looking for a coup or violence within the military. The offer of mercy is based on individual soldiers simply recognizing Maduro as no longer a legitimate leader.

“Our troops know that the chain of command is broken due to the usurpation of the presidency,” Mr. Guaidó wrote on Twitter. “We don’t want the security forces to split apart or clash, we want them to stand united on the side of the people, the Constitution and against the usurpation.” Under the Constitution, the Assembly considers Guaidó to be the interim president, as does the United States.

The steep decline of the Venezuelan economy and of Maduro’s authority has led to rumblings in the military rank and file. An estimated 200 soldiers are political prisoners. More than 4,000 low-ranking officers deserted last year, according to Reuters. Many soldiers know the hardship of their families in a country where 80 percent of the population has been reduced to poverty by Maduro’s mismanagement.

Offers of mercy can be effective in countries torn by civil strife. In neighboring Colombia, forgiveness of Marxist rebels by the government helped end a half-century of war two years ago. Amnesty was used to reconcile people in Rwanda after a genocide 25 years ago. In Indonesia, Islamic terrorists who surrender are offered leniency.

Reconciliation of any people relies on a process of contrition, forgiveness, and renewed affection. The bond that must be restored in Venezuela is mutual respect for constitutional order. In his message to the troops, Guaidó said: “Let democracy, that you once swore to protect, reign again over the political destiny of our country.” The real protests in Venezuela may be happening in the hearts of currently silent soldiers.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Resolving impasses: My way, or God’s way?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Kevin Graunke

Today’s contributor explores the power of God’s light and inspiration to resolve deadlock.

Resolving impasses: My way, or God’s way?

In a commencement address at Dartmouth College nearly 20 years ago, Fred Rogers compared our world to a magnificent jewel, adding that we are facets of that jewel. He said, “In the perspective of infinity, our differences are infinitesimal. We are intimately related. May we never even pretend that we are not.”

It struck me recently how relevant that thought is. I was feeling increasingly upset by the adamant, self-serving tone that marks so much of public debate on important issues – where both sides line up behind an all-or-nothing approach, the main focus being which side wins the argument, not what might actually be accomplished.

But then I began thinking of what my own experience has taught me: that the most significant progress is made when I pray to embrace and respect what God’s will is, and what will serve the greater good. Whenever I seek His way, my way becomes far less entrenched, far less self-important, opening the door to solutions that benefit all involved.

A prayerful, spiritual approach to conflict resolution rises above brainpower and negotiating skills: It starts and stays within the power of God’s all-inclusive, endless love. This divine Love changes hearts and moves hands to constructive action.

In 1905, Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy issued a series of notices relating to praying about the war then going on between Russia and Japan. The last of these, which first appeared in the Boston Herald, emphasized the need for “faith in God’s disposal of events” (“The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” p. 281). Mrs. Eddy added, “On this basis the brotherhood of all peoples is established; namely, one God, one Mind, and ‘Love thy neighbor as thyself’....” The one divine Mind communicates peaceful, intelligent ideas to all of us, God’s spiritual offspring.

How can we apply this idea of “one God, one Mind” to face down barriers that seem impossible to remove? We can let this loving Mind, rather than willfulness or stubbornness, inspire our interactions. I like to draw on the biblical narrative of the Israelites fleeing Egypt after their leader, Moses, freed them from slavery. At one point they were at a total impasse, with the Red Sea in front of them and Pharaoh’s army behind them. Fear gripped them as complaints, blame, and heated debate arose.

But Moses confidently said, “Fear ye not, stand still, and see the salvation of the Lord, which he will shew to you to-day” (Exodus 14:13). Then he stretched out his hand, the waters parted, and the Israelites moved forward safely.

The qualities that stand out to me here are the readiness to listen to someone else’s ideas and direction, and above all the humility to trust in God’s “disposal of events.” They’re qualities I needed a month or two ago when I found myself at a modest but frustrating impasse with a high-tech firm that had advised me to send them a broken computer audio control for repair. I did so, but after several weeks a cryptic email arrived stating that they did not repair small controls, and that I needed to send them the entire computer system.

“I’m not doing that!” I replied. It seemed a totally unreasonable request, and it seemed very clear (to me) that it was up to them to solve the problem they had caused.

But as I waited for an answer, I realized that my willfulness was not going to resolve a thing. Instead, I needed to “stand still” – to take a mental pause and let the intelligence and direction of the one divine Mind, God, open the way. In my prayers I affirmed that God’s powerful love knows no anger, confusion, or dead end – and therefore God’s children, the spiritual expressions of His love and intelligence, could not. Neither I nor anyone else could ever truly be stuck at odds.

As I prayed, my desire shifted from trying to bend other people to my will to yielding to the divine will – to witnessing God’s goodness at hand, whatever the solution might be.

Soon I learned that the company was planning to replace my audio control with a new one. It’s now installed and working perfectly.

Obviously, not every impasse is resolved quickly, especially when there’s more at stake than broken electronics. But no deadlock is so complex or entrenched that it can't be dissolved by the impartial warmth and penetrating light of God, divine Love. As we welcome in that light, we’ll find that what really heals isn’t just winning for ourselves, but actively assuring that everyone wins, furthering true progress for all.

A message of love

Ruff, and ready

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when staff writer Patrik Jonsson looks at the informal safety net springing up to support furloughed government workers across the United States. One result is a more nuanced and compassionate view of those who work in government.