- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- In Mueller investigation, one big question: ‘Why are so many people lying?’

- In Iran, a hardline hunt for ‘infiltrators’ has political target, too

- To take Spain left, prime minister digs up civil war’s legacy

- ‘Feels like home’: Israeli school for migrant kids wins by bridging worlds

- Bauhaus to your house: How designers tap a rich legacy of creativity

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The gift of Facebook

Noelle Swan

Noelle Swan

This week the social media giant everyone loves to hate turned 15. And like many adolescents, Facebook has a complicated relationship with trust.

Polls show that public trust in the platform has been lagging since the 2016 election. There’s a pervading sense that “In Facebook’s maw, each of us became a new kind of surveilled and manipulated commodity,” as MIT’s Sherry Turkle told Vox.

And yet, despite a solid year of revelations highlighting just how much the platform has been eavesdropping on users and profiting from their data, Facebook reported continued growth in its Q4 earnings call last week, boasting more than 171 million active users in the United States alone.

There are many reasons people decide to stick it out with Facebook even when they have misgivings about the company’s actions, as Monitor writers Eoin O’Carroll and Noble Ingram explored in December.

But one reason that Facebook continues to grow is that, for all of the company’s misdeeds, the platform offers people something they crave: the promise of better connections to each other.

Perhaps Facebook’s biggest benefit to society these past 15 years was not connecting the world, but helping the world to see just how much it yearns to be connected.

Now onto our five stories for your Wednesday.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

In Mueller investigation, one big question: ‘Why are so many people lying?’

The stream of indictments flowing out of the Mueller investigation all hinge on one prosecutorial tool: the False Statements Act. The measure can offer an avenue to prosecute otherwise elusive crimes. But it can also be misused.

If there is one unifying feature of the Trump-Russia investigation so far, it is the significant number of President Trump’s associates who have been charged with lying to federal agents or to Congress.

Trump allies argue that the mounting number of cases of lying by Trump associates do not add up to a conspiracy with Russia to fix an American election. “There should never have been a special counsel,” says appellate lawyer Sidney Powell. “[Mueller] created these crimes with his investigation.”

Other analysts see the deception in a completely different light: as a road map revealing the outlines of a Trump-Russia conspiracy. “It is one of the critical themes of this investigation, that there is so much prevarication – that so many people are lying across the board,” says Bennett Gershman, a professor at Pace Law School in New York. “Why are so many people lying and typically lying about contacts between the campaign and Russia?”

In Mueller investigation, one big question: ‘Why are so many people lying?’

If there is one unifying feature of the Trump-Russia investigation so far, it is the significant number of President Trump’s associates who have been charged with lying to federal agents or to Congress.

- Former Trump national security adviser Michael Flynn lied about his contacts with Russia’s ambassador to the United States.

- Former Trump foreign policy adviser George Papadopoulos lied about the date on which a professor in London told him that Russia possessed “dirt” on Hillary Clinton.

- Mr. Trump’s former personal lawyer, Michael Cohen, falsely told Congress that negotiations over a proposed Trump Tower project in Moscow had ended in January of 2016, when the negotiations in fact continued at least until June of 2016.

- Former Trump campaign chair Paul Manafort and his associate Rick Gates lied on Justice Department forms to conceal the true nature of a 2013 lobbying trip to Washington on behalf of Ukrainian government officials, to try to avoid having to register as agents of a foreign government.

- Mr. Manafort has also been accused of violating his cooperation agreement with special counsel Robert Mueller by lying about his contacts with a former associate in Ukraine with alleged ties to Russian intelligence. The deception reportedly included whether Manafort had shared election polling data with the former associate.

- Most recently, longtime Trump ally and Republican political operative Roger Stone was indicted on charges of lying to Congress about his attempts to discover the full scope of WikiLeaks’ 2016 campaign to publicize emails allegedly hacked from the Democratic National Committee by Russian intelligence officers.

With reports that Mr. Mueller’s investigation may wrap up soon, the big, looming question is whether Mueller has evidence that Trump and members of his campaign conspired with Russians to undercut Mrs. Clinton’s candidacy during the 2016 election.

The president has denounced the investigation as a “witch hunt.” And Trump allies argue that the mounting number of cases of lying by Trump associates do not add up to a conspiracy with Russia to fix an American election.

Other analysts see the deception in a completely different light: as a road map revealing the outlines of a Trump-Russia conspiracy.

“It is one of the critical themes of this investigation, that there is so much prevarication – that so many people are lying across the board,” says Bennett Gershman, a professor at Pace Law School in New York. “Why are so many people lying and typically lying about contacts between the campaign and Russia?”

False Statements Act

At the center of each of these charges of deception is a statute that makes it a crime to lie to a federal official or to Congress, called the False Statements Act. It provides that anyone who knowingly and willfully makes a false statement to a federal official has committed a felony punishable by up to five years in prison.

Combined with the perjury statute, the laws provide investigators and prosecutors with a powerful tool to gain leverage over individuals suspected of participating in criminal wrongdoing.

These laws can be critical in defeating an attempted coverup of an underlying crime or conspiracy. But prosecutors also have discretion to use them as a fallback method of meting out punishment when they are unable to prove a more serious crime.

Martha Stewart was famously accused of insider trading and securities fraud. But the crime that actually sent her to prison for five months was that she lied to investigators while being questioned.

Moreover, the lie does not have to involve underlying criminal activity. Any false statement that might throw investigators off track can be prosecuted.

For example, it was not illegal for Mr. Papadopoulos to engage in gossip in 2016 with a professor in a London bar about Russia’s supposed possession of “dirt” on Clinton. But it was illegal for him to lie to the FBI about it in 2017.

It was not illegal for Mr. Cohen to engage in confidential business negotiations in 2016, at the height of the presidential campaign, over a potential Trump Tower construction project in Moscow. But it was illegal for him to lie to Congress about it a year later.

And it was not illegal for Mr. Stone in 2016 to try to learn how much damaging information WikiLeaks might have on Clinton. But lying to Congress a year later about his efforts in that regard would be a crime.

Stone’s case is ongoing, but the rest of these crimes took place in 2017 and were committed as a result of questions posed by the special counsel’s office.

And while there is no doubt that lies were told and that those lies complicated the investigation, it is not yet clear whether these cases of individual dishonesty will ultimately prove the existence of a Trump-Russia conspiracy.

Presumably, the special counsel’s office knows the answer. It could be that the most explosive allegations in the Trump-Russia investigation have yet to be revealed. Or the long list of lies by Trump associates could just be individual cases of deception, for their own reasons, unrelated to any effort to cover up a conspiracy with Russia or other crimes committed during the 2016 election.

Smear campaign or ‘meat and potatoes’ investigation?

Critics of the Mueller investigation say that the special counsel’s office has been using the False Statements Act to mount a smear campaign against the Trump presidency.

“There should never have been a special counsel,” says appellate lawyer Sidney Powell. “[Mueller] created these crimes with his investigation.”

Ms. Powell, a former federal prosecutor and author of the book “Licensed to Lie: Exposing Corruption in the Department of Justice,” contrasts the special counsel’s tactics with the 2015-2016 investigation into Clinton’s use of a private email server.

“Look at the difference in the way the Hillary Clinton group was treated,” Powell says. “They were all given immunity. There were no prosecutions [for false statements] or even suggestions of prosecutions of any of them.”

She adds, “Yet everybody who’s had anything to do with Trump has just been put under the microscope. The False Statement statute has been a key tool of Mueller’s in prosecuting people and squeezing them.”

But Professor Gershman, a former prosecutor and expert in prosecutorial misconduct, says he sees nothing improper in the special counsel’s use of the False Statements Act, calling it “the meat and potatoes of prosecutorial investigations.”

When he was a prosecutor investigating organized crime, Gershman says he often relied on false statements as a way to bring a legitimate charge – and then use that charge as leverage to get the person to cooperate and provide information supporting substantive charges against other people. “That is exactly what Mueller is doing.”

Gershman also disagrees with Trump allies about the thrust and eventual outcome of the Trump-Russia investigation.

“I see conspiracy all over the place,” he says. “I see it throughout the different indictments. If you put them all together, you say there has got to be some kind of conspiracy between people in the campaign and people who are running WikiLeaks and Russian operatives.”

Lying to a federal investigator can also legitimately obstruct an investigation by diverting attention and resources away from the real focus.

The recent Stone indictment says in part: “By falsely claiming that he had no emails or text messages in his possession that referred to the head of [WikiLeaks], Stone avoided providing a basis for [House Intelligence Committee investigators] to subpoena records in his possession that could have shown that other aspects of his testimony were false and misleading.” Stone has pleaded not guilty to the charges.

Lisa Kern Griffin is a professor at Duke Law School. She says that the special counsel’s efforts to prosecute witnesses for lying is critical to vindicate the integrity of the broader Trump-Russia investigation.

Perjury and false statements laws are essential tools for prosecutors, Professor Griffin says. “Sometimes that will mean that defendants face process-type charges in cases where the underlying criminality might not merit charges,” she says.

“But that is not this case,” she adds. “This is a case where the underlying criminality may be the most significant ever to be investigated.”

The Enron example

Powell’s criticism of the special counsel’s investigation is based in part on interactions 15 years ago between one of her clients and Andrew Weissmann, who is today Mueller’s chief prosecutor.

In 2004, Mr. Weissmann was deputy director of the Enron Task Force, set up to investigate what was being called the largest corporate fraud in US history. As part of that effort, Weissmann obtained the conviction of four executives at Merrill Lynch for their involvement in a deal to purchase a $7 million stake in an Enron power-generation project on barges in Nigeria. The deal was a year-end accounting maneuver by Enron.

Weissmann argued that the transaction was a sham because documents he’d obtained suggested that Enron had secretly promised it would buy back Merrill Lynch’s stake in the project within six months.

The case fell apart on appeal. All four convictions on fraud and conspiracy charges were overturned.

Nonetheless, the appeals court, in a split decision, let stand the perjury and obstruction of justice conviction against Powell’s client, James A. Brown.

In an interview with the Monitor, Mr. Brown said he told the truth to the grand jury but that his testimony didn’t fit with Weissmann’s theory of the crime.

According to a transcript of his grand jury testimony, Brown repeatedly insisted that there was no buy-back guarantee. There had been negotiations over one, Brown testified, but in the end, the agreement signed by both parties did not include any such guarantee.

Brown says his lawyers identified a number of witnesses who were directly involved in negotiating the Enron deal and who agreed with his testimony. In response, he says, prosecutors named “everybody who had any kind of contact that would be helpful” to the defense as unindicted co-conspirators. “And they warned them if they testified on our behalf they would be indicted.”

Weissmann also negotiated a cooperation agreement with Merrill Lynch, promising that the company itself would not be prosecuted as long as no Merrill Lynch official made any public statement, in sworn testimony or elsewhere, that might contradict the government’s position in its prosecution of Brown and the other three executives.

This was no idle threat. A year earlier, the Enron Task Force had indicted the accounting firm Arthur Andersen after officials at the company had shredded key Enron audit documents. After the company was convicted of obstruction charges, it collapsed, leaving tens of thousands of employees (most of whom had nothing to do with the Enron matter) out of work. The US Supreme Court later overturned the conviction, but by that time it was too late to the save the company.

A spokesman for the special counsel’s office declined to comment.

In a dissenting opinion in Brown’s case, Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Harold DeMoss noted that the final agreement that both sides signed did not include a guarantee that Enron would buy back the investment. He said the government relied on testimony and documents reflecting early-stage negotiations and that in his view Brown’s testimony was truthful.

Judge DeMoss noted that some of the government’s own evidence supported Brown’s testimony.

“A reasonable jury could not convict Brown of perjury where the government speaks out of both sides of its mouth with respect to the allegedly perjurious testimony,” he wrote.

Ultimately, Brown spent a year in prison after his conviction on perjury and obstruction charges. The legal ordeal extended for nearly a decade and generated legal fees of more than $11 million, he says.

“I would say that nobody should talk to Weissmann, or any federal agent, about anything without an attorney with him and a transcript being created,” he says.

After a pause, he adds: “There is no way I would ever talk to the government again, believe me.”

In Iran, a hardline hunt for ‘infiltrators’ has political target, too

Iranian hardliners’ fear of Western cultural influence has morphed into anxiety over an “infiltration project” by the US, Israel, and others, spurring arrests of alleged enemies, including even government officials.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

For years there’s been a widening crackdown inside Iran against alleged enemies of the Islamic Republic. Environmentalists, women’s rights activists, and lawyers have increasingly been targeted. Even a member of Iran’s nuclear negotiating team is now behind bars.

The bulk of security arrests are made by the Intelligence Organization of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Its ideologues – echoing Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei – have been stepping up warnings of enemy infiltrators, going so far as to claim that all levels of the regime have been penetrated and must be “fundamentally cleansed.” But that all-powerful IRGC arm is often in competition with the Ministry of Intelligence, controlled by the relatively moderate President Hassan Rouhani, with the rivalry sometimes boiling down to disputes as basic as who is and who is not a spy.

An Iranian analyst who asked not to be named says there is a “clear element of partisanship” in the crackdown, directed against Mr. Rouhani. “They want to beat up on Rouhani because they feel he is on the ropes now, the [nuclear deal] has almost collapsed, and ‘we can go in for the strike and cut him off at the knees,’ ” says the analyst.

In Iran, a hardline hunt for ‘infiltrators’ has political target, too

She once won Iran’s Book of the Year prize for a scholarly examination of fertility rates. But the Iranian-born academic was arrested last November, accused of “infiltration” and “espionage” – part of a widening crackdown inside Iran against alleged enemies of the Islamic Republic.

Dr. Meimanat Hosseini-Chavoshi, a research fellow at the Australian National University and citizen of both Iran and Australia, was released from prison in late January.

But her incarceration is just one of dozens that signify a new round of “securitization” in Iran, a clampdown marked by the heightened activity of the intelligence and security apparatus. Environmentalists, women’s rights activists, and lawyers have increasingly been targeted. Even a member of Iran’s nuclear negotiating team is now behind bars.

That result is the culmination of a transformation among hard-line elements in Iran, from a stated fear of a Western “cultural invasion,” above all, to apparent anxiety about an “infiltration project” by the United States, Israel, and other enemies, analysts say.

The clampdown began during the Obama years, with such high-profile cases as the 544-day imprisonment of Washington Post correspondent Jason Rezaian, who was accused of being the CIA “station chief” in Tehran. But the current escalation has coincided with President Trump’s expressed determination to impose “maximum pressure” against Iran.

The bulk of security arrests are made by the Intelligence Organization of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which reports directly to Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Its ideologues – echoing Mr. Khamenei – have been stepping up warnings of enemy infiltrators, going so far as to claim that all levels of the regime have been penetrated and must be “fundamentally cleansed.”

But that all-powerful IRGC arm is often in competition with the Ministry of Intelligence, controlled by the relatively moderate President Hassan Rouhani, with the rivalry sometimes boiling down to disputes as basic as who is, and who is not, a spy.

Caught in the middle have been Iranians with dual US, UK, or Canadian citizenship, environmentalists working to protect Iran’s endangered Asian cheetah population, women’s activists determined to change mandatory hijab laws, lawyers who have sought to defend them, and many others.

“Once Mr. Khamenei changed his language from ‘cultural invasion’ to the notion of specific infiltration, he opened the way for all these arrests,” says Farideh Farhi, a veteran Iran expert at the University of Hawaii.

“Cultural invasion was a broad concept of McDonald’s coming, of cultural changes,” says Ms. Farhi. “Infiltration is infiltration inside the government, and that completely changed the game. It shows a sense of insecurity. It has had consequences that we see.”

Amnesty sees ‘repression’

Amnesty International estimates that at least 63 environmental activists and researchers were detained in 2018, among some 7,000 Iranians that the human rights group calculates were arrested, most during antigovernment protests, in what it calls a “shameless campaign of repression.”

This week, Iran’s top judge asserted that Iran held no “political prisoners,” and said 50,000 inmates would be pardoned or have their sentences shortened to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

But those are not likely to include long-standing “security” cases, such as those of US-Iranian businessman Siamak Namazi, held since October 2015, or his father, Baquer Namazi, 82, also a dual citizen and former UNICEF diplomat. Both were convicted of “collaborating” with an enemy power. They are among several other US and US dual citizens imprisoned in Iran.

As the Islamic Republic marks its four-decade birthday, it faces multiple challenges. Among them: an economy crippled by renewed US sanctions, corruption, and mismanagement; a society deeply divided by the rigors of that revolution; and a political space that is gridlocked, pitting hard-line factions staunchly against Mr. Rouhani.

They vilify the president for reaching out to the West, and for believing that the 2015 nuclear deal he agreed to with the US and other world powers would remove all sanctions and jump-start the economy, in exchange for restricting Iran’s nuclear program.

It was while that nuclear deal was being finalized that Khamenei’s warnings of “infiltration” took on greater urgency, expanding into a catch-all action framework – and license to arrest – for Iran’s hard-line IRGC intelligence arm.

Weeks after the July 2015 deal was agreed, for example, Khamenei stated that the nuclear talks were “just their [US] tool for infiltration and imposing their will.” Addressing IRGC commanders on Sept. 16 that year, Khamenei used the term “infiltration” 34 times in a single speech, warning that the enemy’s aim was “weakening … our revolutionary and religious beliefs.”

The pace of warnings has barely eased, and their scope has widened. In late 2017, Khamenei said: “Our officials must beware the presence of enemy-assigned infiltrators in decision-making institutions [and] must find out what the enemy is up to.”

Likewise last spring, after IRGC intelligence had stepped up arrests, and Iran was reeling from periodic labor and economic protests nationwide, Khamenei described a multitude of enemy tactics on a “tough battlefront … in this war,” which ranged from “manipulating decision-making processes” to “causing economic and financial turmoil.”

Caught in the net, beside the Americans, has been Canadian-Iranian Abdolrasoul Dorri-Esfahani, a central bank adviser and member of Iran’s nuclear negotiating team. He was arrested in mid-2016 and sentenced in October 2017 to five years in prison, despite protests of his innocence by Rouhani officials.

Taking direct aim at the president and his allies, the IRGC intelligence arm last September produced a 21-minute propaganda film broadcast on state-run TV. It cast him as a spy and said one aim of Western nations “was to put an infiltrating agent inside our negotiating team.”

Also snared have been dual UK-Iranian citizens such as Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, a charity worker held since April 2016 on spying charges she denies, and Abbas Edalat, a computer science professor at Imperial College London held for eight months last year. Ironically, he had founded an organization called the Campaign Against Sanctions and Military Intervention in Iran (CASMII).

After Mr. Edalat’s release in late December, CASMII said that such a “misunderstanding” by Iran’s security apparatus should be seen in the context of “multi-pronged attacks and open threats of the US, Israel, and their allies to destabilize the Islamic Republic of Iran – including massive spending on economic warfare, espionage, and psychological operations against Iranians.”

Was environmentalist a spy?

But the case that perhaps tells most about the prevailing ideology of the “infiltration project” and the political divisions between Iran’s intelligence branches is the arrest of nine environmentalists a year ago who worked for the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation.

Two weeks after their arrest, Kavous Seyyed-Emami, a renowned Iranian-Canadian professor who founded the wildlife body, mysteriously died in prison in what authorities called a suicide – a conclusion rejected by Mr. Seyyed-Emami’s family.

The Tehran prosecutor asserted that the wildlife foundation had been set up as a cover to collect data about sensitive defense and missile bases, and to “infiltrate” Iran’s scientific community “under the guidance” of operatives of the CIA and Israel’s Mossad.

Four of the researchers have reportedly been charged with “corruption on earth,” a crime which can carry the death penalty, and others with spying. Human rights monitors allege that detainees were subjected to months in solitary confinement, death threats, and physical abuse to force confessions.

Throughout, advisers to the president and the Ministry of Intelligence have repeatedly dismissed the IRGC claims against the environmentalists. One reformist lawmaker tweeted last May that ministry experts, based on “indisputable evidence and documents,” had found “no proof” of espionage.

Amid the intelligence tug of war, Rouhani reportedly set up a committee of his security ministers to press for their release.

Then last month, an extraordinary story appeared about the “victim of infighting” between intelligence services. Citing unnamed sources – which some believe may have been from inside the president’s office – the Zeitoon website reported that Israeli operatives had long ago contacted Seyyed-Emami, asking for his collaboration.

According to Zeitoon, Seyyed-Emami then informed the Ministry of Intelligence, which asked in turn if he would take part in a counter-espionage effort, by providing the Israelis with incorrect information. Seyyed-Emami allegedly agreed.

“For quite some time then, he delivered wrong map data and false numerical facts to the Israelis under the supervision of the Ministry of Intelligence,” Zeitoon wrote. It was this activity, monitored by IRGC intelligence and unknown to Seyyed-Emami’s colleagues, which led to the arrests, the website reported.

“If this narrative is correct, then it suggests that [IRGC intelligence chief Hossein Taeb’s] enmity, his partisanship [against Rouhani] is to the extent that he would sabotage an ongoing disinformation campaign,” says an Iranian analyst outside the country, who asked not to be named and is familiar with such cases.

“What this also tells us is that these groups are being targeted,” says the analyst.

Targeting Rouhani

Because Rouhani has criticized the IRGC in the past, there is a “clear element of partisanship, that they want to beat up on Rouhani because they feel he is on the ropes now, the [nuclear deal] has almost collapsed, and ‘we can go in for the strike and cut him off at the knees,’” says the analyst.

As that power struggle continues, the need to root out infiltrators has not faded from the to-do list of Iran’s most strident revolutionaries.

A lengthy speech last August by Alireza Pourmasoud, a hard-line researcher and ideologue connected to the IRGC, traces the “roots of infiltration” back to pre-revolutionary times in the 1960s and 1970s.

Mr. Pourmasoud argues that the CIA, MI6, and Mossad planted agents inside SAVAK – the intelligence service of the pro-West Shah, a close ally of the US and Israel – who then seamlessly embedded themselves in the security structure of the Islamic Republic, where they and their recruits continue to secretly wreak havoc to this day.

“This network has to be unmasked, we need to know who is doing what,” Pourmasoud says in a shortened version of the speech made more concise for easier circulation, which emerged in recent weeks.

“Today the ones who are harming the revolution … are hidden as religious people who act pretty well, they say their prayers in such a committed way that provoke your jealousy,” says Pourmasoud.

“It’s all about some fundamental cleansing that has to be done in our country,” he concludes. “They do infiltrate our establishment from the top, places that you cannot even believe.”

To take Spain left, prime minister digs up civil war’s legacy

Sometimes moving forward requires taking a hard look at the past. In Spain, the prime minister is hoping that his push to confront the nation’s fascist past will buy him credibility to lead its future.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

For people like nonagenarian Felipe Gallardo, Spain’s new prime minister brings hope for settling their family history. Last summer, Pedro Sánchez ordered former dictator Francisco Franco’s exhumation from a state-funded memorial. Mr. Sánchez also promised to locate thousands buried in unmarked graves after the 1936-39 civil war, of which Mr. Gallardo’s father is one.

That has yet to happen. But Sánchez’s bold move breaks the status quo on which Spain’s democracy was built, a consensus to leave the past behind.

Next week, Sánchez will be tested on two fronts: His budget will be voted on, and the Supreme Court is set to begin the trials of pro-secession, jailed Catalonian leaders. “Sánchez heads a very frail government right now, so he can’t pass groundbreaking policies in the social or economic realm,” says political scientist José Manuel Ruano. “He’s hoping that the symbolic measures help change the public opinion’s perception of the Socialist Party in hopes that will benefit him during the next elections.” Gallardo’s daughter, Purificación, agrees on a wait-and-see approach. But she says the Franco plan “means there’s no turning back. The real transition to democracy starts now.”

To take Spain left, prime minister digs up civil war’s legacy

As symbolic gestures go, Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez went all out.

Shortly after his surprise elevation to high office in early June, Mr. Sánchez ordered the exhumation of Gen. Francisco Franco’s remains, with the intent to separate the former dictator from the more than 33,000 others buried at the national monument holding Spain’s civil war dead.

That has yet to happen. But Sánchez’s bold move was one sign that he is willing to go further than the left-wing governments before him to win over voters.

As the vulnerabilities of the smallest governing majority in Spain’s modern history emerge, analysts question the scope of Spain’s transformation under Sánchez and how much the young prime minister will accomplish. Some on the right see the Franco decision as digging up the past for revenge. But for those on the left, it is raising hope for the introduction of a thorough socialist agenda – and for a reckoning with the unresolved legacy of the Franco era.

Valley of the Fallen

For people like Felipe Gallardo and his daughter, Purificación, such a reckoning would be entwined with family history. Mr. Gallardo, who is in his nineties, left Spain with his young family and returned only after Franco’s death. His father was executed after the civil war and is believed to be buried in a mass grave, like tens of thousands of others. With Spanish government after government, Gallardo postponed his need for closure and didn’t press the issue of locating missing relatives.

“The years went by, and I realized the Socialists had no intention of addressing the subject. I lost all my faith in them,” he says.

That changed last summer when Sánchez ordered Franco’s removal from the Valley of the Fallen, the state-funded monument, basilica, and memorial that was built by the former dictator as an apparent attempt at reconciliation after the civil war. The 1936-39 conflict divided the country between leftist democratic Republicans and Franco's Nationalists.

This site of pilgrimage, 40 miles outside Madrid, is not neutral. It was built by Republican political prisoners, and besides Franco, tens of thousands of people, both Republicans and Nationalists, were moved from mass graves across Spain and buried anonymously there.

The country “cannot afford symbols that separate Spaniards,” Sánchez said in August.

Sánchez’s plan to open Franco’s tomb breaks the status quo on which Spain’s democracy was built. After Franco’s death in 1975, the transition to democracy relied on a consensus to leave the past behind. A 1977 amnesty law forbade the prosecution of war criminals and Franco officials.

“Despite the Socialist governments we had since Franco’s death, the right wing has been controlling Spain,” says Purificación. In 2010, she found her grandfather’s name in a book about the civil war and started the family’s search for him. “Now something seems to be changing,” she says.

Sánchez won a parliamentary vote of no confidence on May 31 against former Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, who is implicated in an ongoing corruption scandal. Sánchez’s Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) has just one-quarter of the seats in Parliament, relying on a fragile alliance with Pablo Iglesias’s far-left party Podemos (“We Can”) and Catalan and Basque nationalists. Sánchez has been hailed by some for his progressive policies, an exception in Europe where right-wing populism has soared.

A more progressive Spain?

In June, the new prime minister unveiled a government that had more women than men, with women heading 11 of the 17 ministries, and announced that his team was “a government for an equal society, open to the world but anchored in the European Union.”

Shortly after, Sánchez offered a safe port for the Aquarius migrant rescue ship, which had been drifting in international waters with 630 people on board after being rejected by Italy and Malta. “It is our duty to help avoid a humanitarian catastrophe and offer a safe port to these people, to comply with our human rights obligations,” Sánchez said when welcoming the ship in Valencia.

All these moves granted him the nickname of Spain’s Trudeau, an allusion to the Canadan prime minister’s style of politics, and raised hopes for boosting Spain’s center-left PSOE.

When the new prime minister hit the 100 days in office mark in September, the PSOE had reached a 30.5 percent approval rate, with the conservatives lagging behind at 20.8 percent. This peak in popularity happened at the same time Sánchez became the latest politician to deal with allegations around his academic degree and the resignations of two cabinet ministers. In December, Socialists’ support had dropped to 21.3 percent of Spaniards, while only 14.1 percent would choose the center-right People’s Party.

According to Esteban Hernández, a journalist for the online newspaper El Confidencial, Sánchez’s vulnerability lies precisely in his attempt to follow Trudeau’s template instead of pushing for a “Roosevelt-like turn” on the left.

“What Trudeau and Sánchez are doing is to preserve an order that can no longer be preserved. Social democracy is in crisis, and it’s being attacked by a very strong right wing represented by [Matteo] Salvini in Italy and Trump in the US,” Mr. Hernández says. “What the left needs to do to be a viable option against those leaders is to take a sharp and solid Rooseveltian turn, the type that [Bernie] Sanders and [Jeremy] Corbyn proclaim. But there’s no such leader in Spain,” he adds. A new leader on the left needs a transformative approach, not just a refurbishing of neoliberal politics, disguised to look progressive on the surface but failing to really change the system, he says.

Hernández believes Sánchez is not a viable leftist option because his focus on women’s and immigrant’s rights, while addressing historical divisions, doesn’t alter the “power structure,” he says. Furthermore, he believes that Spain’s relative immunity to far-right nationalism will eventually give way. “We have a delay regarding what’s happening in Europe because our democracy is fairly recent. But we might catch up,” Hernández adds.

José Manuel Ruano, a political scientist at Complutense University in Madrid agrees that the majority of Sánchez policies have been symbolic, but he sees that as part of a strategy to build a progressive platform that gathers momentum for the next elections.

“Sánchez heads a very frail government right now, so he can’t pass groundbreaking policies in the social or economic realm. He’s hoping that the symbolic measures help change the public opinion’s perception of the Socialist Party in hopes that will benefit him during the next elections,” Professor Ruano says.

The government attempted a less than symbolic measure when it signed an anti-austerity budget deal with the far-left Podemos. The text – which includes significant raises in taxes and pensions as well as an increase in the minimum wage from €736 ($837) a month to €900 ($1024) – also states the need to “reverse the scars of austerity, reduce inequality, precariousness and property,” blaming former Prime Minister Rajoy for “seven years of cutbacks and suffocation.”

Next week, Sánchez will be tested on multiple fronts. His budget plan will be up for a vote, and two pro-Catalan parties are threatening to withhold support for the budget. Sánchez said in November that if the budget is not approved, the government may hold early elections. Also, the Supreme Court is set to begin the trials of the pro-secession Catalonian leaders. And several opposition parties are calling for protests against Sánchez this coming weekend for announcing that a “rapporteur” would be included in talks regarding Catalonia. Although the government downplayed the role as a note-taking coordinator, opponents of Catalan independence say that such a representative elevates the status of the region, which has been asking for a mediator.

Dealing with the past

With the budget still in question, most analysts agree that the plan to remove Franco from the Valley of the Fallen is the most significant decision symbolically, given the right and left divisions still present in Spain today. Franco’s family has pledged to use all legal means to stop the exhumation of the dictator.

“There’s nothing truly progressive about Sánchez’s government when it comes to foreign politics or economics,” says António Costa Pinto, a political scientist at the University of Lisbon.

“But this announcement is the strongest weapon … the Socialists have against the center-right, which has always remained ambiguous about the legacy of the dictatorship.... Spain remains a singular case regarding other European democracies that condemn their fascist pasts. Even in Latin America, where there was also a pact of silence regarding the dictatorships of the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, there were trials of political leaders or those who carried out torture and murder. In Spain, not a single person was tried for human rights violations.”

The Gallardo family stopped voting for PSOE years ago and is still distrustful of the Socialists’ progressive agenda. “We still have to wait and see what social and economic measures they will approve, but regarding Franco and the civil war, this announcement means there’s no turning back. The real transition to democracy starts now,” Purificación says.

‘Feels like home’: Israeli school for migrant kids wins by bridging worlds

How to provide for the children caught up in the uncertainty and often trauma of migration is an increasingly pressing question for many societies. A school in Tel Aviv offers a model that is succeeding.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Dina Kraft Correspondent

Israeli government plans last year for a mass deportation of African asylum-seekers created a public outcry and remain on hold. But migrant families and their children live in a painful state of uncertainty. Yet in an impoverished neighborhood in Tel Aviv is a school dedicated to helping migrant children thrive educationally and emotionally, teaching students about Israeli society while honoring their home cultures. Officials say the school can serve as a model for others around the world.

The Bialik-Rogozin school is one of the top performing schools in the country. “I have friends from Nigeria, Malta, Sudan, Eritrea, and Turkey.… It feels like home here, and for now Israel is home,” says Ariella, who was born here to Filipino parents.

“We don’t know if they will stay here or one day return to home countries, and either way they need to know their mother tongue,” says Eli Nechama, the principal, who defends the decision to educate migrant children in separate schools, rejecting the notion it is racist. “The choice here is of a school that takes on the underdog and turns them into a star, with all doors open to them…. Look at the results: We are succeeding.”

‘Feels like home’: Israeli school for migrant kids wins by bridging worlds

The second-graders have their pencil cases out and their notebooks open as they write down the words to a classic Hebrew song made famous by an icon of Israeli music.

Most of the children were born in Israel. But their mothers and fathers came here as asylum-seekers or foreign workers.

A visitor asks what countries their parents came from. “Eritrea!” shouts out one girl. “The Philippines,” chimes in another. “Nigeria,” answers a smiling boy in a bright red jacket.

On the walls are letters of the Hebrew alphabet, cardboard cupcakes connoting students’ birthdays coming up, and drawings the children made of trees to mark the recent holiday of Tu BiShvat, the Jewish version of Arbor Day.

The children are students at the Bialik-Rogozin School, which was opened by the city of Tel Aviv 15 years ago with the goal of helping migrant children, most of them undocumented and economically disadvantaged, thrive educationally and emotionally. It is supported by donations.

“Here we have kids from so many different places. I have friends from Nigeria, Malta, Sudan, Eritrea, and Turkey.… It feels like home here, and for now Israel is home,” says Ariella, 12, who was born here to Filipino parents. “When we have troubles, we have teachers we can go to for help.”

Ariella’s mother works as a live-in nanny for a family outside of Tel Aviv, and she sees her on her days off. Ariella, who lives with a family friend, plays basketball and soccer through the school and recently started playing guitar in an all-girl band directed by a young Israeli woman volunteer.

School officials say their model of teaching students about Israeli society while honoring students’ home cultures can serve as a model for other schools around the world with large migrant student populations. The school, which offers long school days, seeks to pinpoint and cultivate individual students’ strengths, provides emotional support, and taps into a network of volunteers to lead extracurricular courses and engage in private tutoring. Its approach has achieved great success.

Mayors of several major European cities are among the many that have come to visit the school, which first drew international attention when a short documentary about its innovative approach, Strangers No More, won an Oscar in 2011.

In the ensuing years, Israel has absorbed what has become an unprecedented surge of foreign workers and asylum-seekers. The country was founded as a safe haven for Jews around the world just three years after the last of 6 million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust, but the puzzle of what to do with these non-Jewish newcomers and the children many of them arrive with or have once in the country remains unsolved.

About half of Bialik-Rogozin’s students are the children of African asylum-seekers, who today number some 38,000 people. Government plans early last year for a mass deportation were met with a public outcry and legal obstacles and remain on hold. But asylum-seeker families have been left in a painful and economically costly state of uncertainty, as a portion of their income is withheld to encourage them to leave voluntarily.

Community support

In the wake of the government’s announced plans, the school redoubled its mission to help children and their families emotionally and practically. Eli Nechama, the principal, says the school was heartened by the outpouring of public support for its work and for the asylum-seeker community in general.

“The government has been less than great, but the people have been wonderful,” he says, pointing out a framed soccer jersey hanging in his office. It is from one of Tel Aviv’s major soccer teams and was made last spring while the government was threatening deportations. Under the school’s name, a slogan reads “One of us.”

From its early days the school has looked to the larger community to help fulfill its vision. That has included drafting business leaders to help raise funds from individuals and companies to help cover the annual $500,000 cost of the “extras” it provides its students. A roster of 140 volunteers now provides the backbone of enrichment and extra support for the students, from teaching classes in painting and photography and drafting high-tech companies to donate classroom technology to serving as personal mentors and tutors.

With the help of Karen Tal, the school’s first principal, Bialik-Rogozin has already become a model for dozens of schools serving underprivileged students in Israel, including several in Arab villages and ultra-Orthodox Jewish neighborhoods. Ms. Tal formed a nonprofit organization called Tovanot B’Hinuch (Educational Insights) to help the other Israeli schools replicate its success.

At 7:30 every weekday morning, the first of Bialik-Rogozin’s 1,150 first-grade through 12th-grade students start arriving. Many will stay till 5:30 in the evening, kept busy long after the school day ends – and while their parents work – with classes in art, sports, music, cooking, and robotics.

Recently, as the reality of the threat of deportations has set in, lessons in the languages of their parents’ home countries have been added, including Tigrinya (spoken primarily in northern Ethiopia and Eritrea), Arabic, Spanish, and English.

In the evenings, the school hosts classes in Hebrew and parenting skills for the parents.

“We don’t know if they will stay here or one day return to home countries, and either way they need to know their mother tongue,” says Mr. Nechama. He is standing in the school’s lobby in front of a floor-to-ceiling portrait of the students under the school logo – “We are all the children of life,” taken from the lyrics of a song – written in Hebrew and several of the other languages spoken at the school, where 51 countries are represented. A few steps away in a courtyard hang the flags of each of those countries.

The school is located at the intersection of streets whose names, translated from Hebrew, mean Homeland Road and Immigrant Lane, a reminder that the modern state of Israel was founded on immigration.

But it was the immigration of Jews from around the world that the state was built around, not of East Africans fleeing wars and dictatorships or of host workers from Asia and South America whose children study at the school.

Top performance

Nechama, a successful theater actor who made the transition to teaching, defended the decision to educate migrant children in separate schools. Since Bialik-Rogozin’s founding, two other schools for migrant children have opened in Tel Aviv. Nechama said this should not be viewed as segregation. All of the schools are in south Tel Aviv, the poorest part of the city and where most migrants live.

“They have special needs,” he says of the children. “It’s not special education, but they do have particular needs because of the objective gaps they have and because it is not clear where they are going to be tomorrow.”

One of the new Tel Aviv schools, the Yarden School, is fundraising to build a therapeutic center within the school to assist children who have experienced trauma and need extra emotional support.

Nechama adds, “For those who say they think this looks racist, I say change how you are looking at this situation. The choice here is of a school that takes on the underdog and turns them into a star, with all doors open to them. This is better than the other options. And look at the results: We are succeeding.”

Bialik-Rogozin is among the top-performing schools in the country, with 96 percent of its students passing the matriculation exams that are a prerequisite for university entrance in Israel. Its boys basketball team has won national championships and represented Israel abroad, and students have won top prizes in national robotics contests.

In a music room decorated with the images of musical greats, including Bach and Bob Marley, Ariella’s all-girl band practices. The three fellow seventh-graders include a singer, a drummer, and a pianist. She’s on the guitar.

“I come here because it’s fun,” she says of the only school she has ever attended. “I’ve hardly missed even a day.”

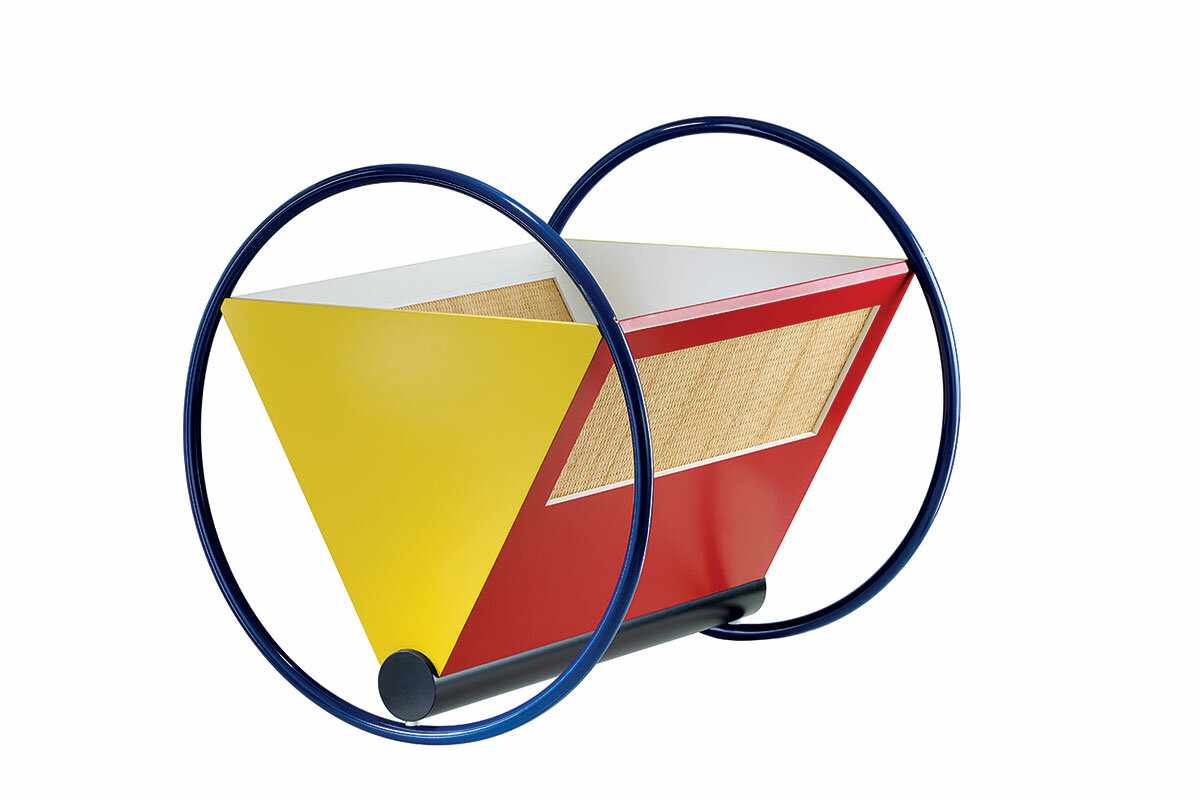

Bauhaus to your house: How designers tap a rich legacy of creativity

By definition, modern design is new and edgy. But to understand the prevailing aesthetic today, you need to look back 100 years to the Bauhaus.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Carol Strickland

As a revolutionary design school started in the German town of Weimar in 1919, the Bauhaus incited a movement that now lives on in the imaginations of artists and designers all over the world. Today’s designers work in “brainswarming” labs and create hands-on prototypes, fulfilling Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius’s call for a “new type of worker for craft and industry, who has an equal command of both technology and form.”

Gropius and the other teachers at the Bauhaus, including Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Marcel Breuer, anticipated the design studios of the future with their emphasis on collaboration, flexibility, and cooperation with industry. Laura Muir, curator of the exhibition “The Bauhaus and Harvard” at Harvard Art Museums in Cambridge, Mass., describes their viewpoint as “starting from zero and not looking back at the past.”

“We should credit the Bauhaus with the awareness that simplicity and honesty of form are values that survive as design principles,” says Steven Eppinger, Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor of product development and innovation. “If we didn’t start with the Bauhaus, we would never have gotten where we are today.”

Bauhaus to your house: How designers tap a rich legacy of creativity

It’s no exaggeration to say the Bauhaus movement profoundly shaped our built environment and the products we use every day. From the midcentury modern chair you sit on, to the gooseneck lamp on your desk, to the graphic font used in the magazine you read, the Bauhaus is in your house. In fact, the name comes from the German words bauen (to build) and haus (house).

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Bauhaus, which was first a revolutionary design school and today lives on in the imaginations of artists and designers all over the world. Today’s designers work in “brainswarming” labs and create hands-on prototypes, fulfilling Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius’s call for a “new type of worker for craft and industry, who has an equal command of both technology and form.”

Linking craft and artful design to industrial production was a Bauhaus innovation with an egalitarian purpose. High-quality furnishings like Marcel Breuer’s tubular-steel chair – inspired by his bicycle’s handlebars – were, and still are, produced in large numbers. Mass production extended the benefits of good design not just to the elite but to the public in general.

To mark the centenary of this radical school of art, architecture, and design, exhibitions are happening not only across Germany where the Bauhaus was born but in Japan, China, Israel, Brazil, Russia, the Netherlands, and the United States. Inaugurated in the city of Weimar in 1919, the school lasted just 14 years – until the Nazis shut it down in 1933. But what the Bauhaus lacked in duration, it made up for in the durability of its ideas.

Since the Bauhaus school evolved in three locations (Weimar, Dessau, and Berlin) under three directors (Gropius, Hannes Meyer, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe), defining its essence is difficult. Laura Muir, curator of the exhibition “The Bauhaus and Harvard” (on display through July 28 at Harvard Art Museums in Cambridge, Mass.), describes the key viewpoint as “starting from zero and not looking back at the past.”

Jeffery Mau, adjunct faculty member at Chicago’s Institute of Design at the Illinois Institute of Technology, adds: “The idea was to bring together people from all backgrounds professionally and culturally to build the future.”

No distinction between art and craft

One revolutionary concept that still permeates art schools and design firms today is a multidisciplinary workshop approach. In devising the Bauhaus curriculum, Gropius erased the hierarchical distinction between fine and applied art so that even a student who wanted to study painting or sculpture first had to learn technical skills like carpentry and pottery. Before specializing, every student learned crafts like metalworking, theater design, and weaving.

Team teaching was another innovation, with both a master artisan and a master artist participating in each workshop. Talk about star power: The dream faculty included Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy, Lyonel Feininger, Josef Albers, and Breuer, all avant-garde artists whose work became synonymous with modernism. These Bauhaus teachers threw out traditional methods of art instruction like so many empty tubes of paint. No longer were aspiring artists forced to imitate Old Masters and historical models.

Bauhaus students and masters worked side by side. To discover properties and possibilities of materials like wood or metal, they assembled and transformed bits and pieces into original forms. As New York’s Museum of Modern Art curator of design Juliet Kinchin says, “They had a passionate and positive engagement with design in the workshops, which encouraged experimentation and open-ended thinking.”

This learning through hands-on experience “is still the foundation of how a studio is taught,” said Amale Andraos, dean of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation.

The stress on versatility anticipated a necessity of design today: flexibility. In a digital world of rapidly mutating technology, learning basic principles and then applying them in new contexts is mandatory. “There’s no manual,” says Michael Hendrix, partner in the global design firm Ideo. “You learn as you go.”

The focus on playing with materials is a crucial component, according to Mr. Hendrix.

“To be creative, you have to be happy,” he says. “Play is how we discover new things, and the Bauhaus actually adopted that.” The Bauhaus hosted rowdy parties, zany dances, and a house band. Today, table tennis and hoverboards abound on the campuses of high-tech companies.

Another Bauhaus contribution that remains relevant is the insistence that basic, functional form matters. “We should credit the Bauhaus with the awareness that simplicity and honesty of form are values that survive as design principles,” says Steven Eppinger, Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor of product development and innovation. “If we didn’t start with the Bauhaus, we would never have gotten where we are today.”

Another way Bauhaus ideals survive is the emphasis on cooperation with diverse partners. “Design is an intrinsically collaborative process,” Ms. Kinchin explains. “Designers work with imaginative manufacturers, retailers, and advertisers who all contribute to the final product.” Mr. Mau agrees: “The idea of a lone genius inventing something is fine, but it doesn’t scale.”

Better design = better world

Many designers and architects today echo the quasi-utopian ambitions of Hannes Meyer, the second director who took over in Dessau when Gropius stepped down in 1928. The left-leaning Meyer believed design could create a more equitable society, or, as Ms. Andraos says, “There was a sense that art could change people’s lives.” She adds, “That level of engagement and ambition is still inspiring. In architecture and design schools today, a new generation is trying to bring together aesthetic and social aspirations.” Today’s designers face both the opportunities and challenges of a world threatened by climate change, a complex problem that enlists their ability to visualize possibilities and imagine solutions.

Socially engaged design goes by various names: responsible design, design for social innovation, human-centered and even post-human design (referring to people’s needs conjoined to the plant and animal world). Many designers base their solutions on a moral imperative, advocated by Ulm Institute of Design, founded in West Germany in 1953 as the New Bauhaus. As Hendrix says, “Design is most powerful when it’s not fabricating desires but doing good, contributing to the lives of people and filling real needs.”

From Victorian frill to modern chill

In many ways, the Bauhaus was an incubator for progressive ideas, but its insistence on clean, functional form (so different from elaborate Victorian ornamentation and historical references) also drew criticism. Tom Wolfe, in his 1981 book, “From Bauhaus to Our House,” disparaged the unadorned lines as overly stark and sterile. “With distance,” Andraos says, “we can see both Bauhaus successes and failures.” Specifically, she cites, “The negation of history is not something we endorse today.”

The Bauhaus infatuation with basic geometric forms and primary colors was another shortcoming, according to Hendrix. “Where any movement goes wrong,” he says, “is if it becomes dogmatic in reacting against what they were fighting.” While the Bauhaus emphasis on purity of form led to the International Style invented by Bauhaus architects like Gropius and Mies, its proliferation spawned a monotonous cityscape. Adopted by copycat developers, the “less is more” mantra became a cliché, producing knockoffs like glass-and-steel towers with flat roofs from Detroit to Dubai.

Laura Forlano, associate professor at the Institute of Design in Chicago, notes another flaw of the early Bauhaus: sequestering female students in the weaving workshop. Even a brilliant artist like Anni Albers, who entered the school to study painting, was shunted off to textile design, where she transformed the medium. Gunta Stölzl, who taught weaving, was the only woman on the Bauhaus faculty. Other gifted female artists were treated as marginal players in the mythology that sprouted around the Bauhaus. Marianne Brandt designed elegant metal objects like light fixtures and tableware, and Lucia Moholy documented Bauhaus life in striking photographs. One goal of “The Bauhaus and Harvard” exhibition is “to underscore the role of women at the Bauhaus,” according to Ms. Muir, the curator.

The demise of the Bauhaus actually spread its influence. After Hitler slammed its doors shut – denouncing it as un-German,

degenerate, Bolshevik, too international, and too Jewish – teachers and students spread Bauhaus ideas everywhere. In the US, émigrés like Gropius and Breuer taught architecture at Harvard, Josef and Anni Albers taught at Black Mountain College in North Carolina and later at Yale, and Moholy-Nagy founded the New Bauhaus at the Institute of Design in Chicago, where Mies ended up leading the Illinois Institute of Technology.

The Bauhaus, which began as a tangible entity – a school – became an intangible but mighty movement. Bauhaus ideals took root wherever designers envisioned a better world. As Mies, its final director, said, “Only an idea has the power to spread so widely.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A contest of butter vs. guns in Venezuela

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The crisis over who rules Venezuela has come down to guns vs. butter. Crates of supplies from countries that regard Juan Guaidó as acting president are piling up at the Colombian border. Much of the West and Latin America want to help Venezuelans. They also want to boost the legitimacy of Mr. Guaidó, who would distribute the aid to show his ability to govern. Yet the aid is being blocked by forces loyal to Nicolás Maduro, whose legitimacy has faded and whose foreign backers are few. Will the military side with Guaidó by helping the aid to flow? To achieve a “soft coup” without violence will require that Guaidó and his backers ensure the aid continues to serve a humanitarian purpose and not be used as a weapon. One official from the Organization of American States has called this a “Gandhian” way of letting the people choose their leader by allowing a delivery of aid across the border. Venezuela has become a contest of ideas. The aid at the border is now there for the people – and the military – to show which side they are on.

A contest of butter vs. guns in Venezuela

In a clichéd sort of way, the tense crisis in Venezuela over who rules the country has come down to this: guns vs. butter. Almost literally.

Crates of food and other supplies from foreign countries that regard Juan Guaidó as the acting president are piling up at the border with Colombia, at his request. Millions of Venezuelans are desperate for humanitarian relief. Much of the West and Latin America want to help them. They also want to boost the legitimacy of Mr. Guaidó, who plans to distribute the aid as a display of his ability to govern.

Yet the aid is being blocked by military forces still controlled by Nicolás Maduro. His legitimacy as president has faded since last year’s bogus election. And his main foreign backers are now only Cuba, Russia, and China.

In a test of loyalty, any army officer who allows the aid to cross the border is, in effect, abandoning Mr. Maduro. If enough officers side with the majority of Venezuelans who are hungry and protesting, a mass defection of the military could follow. Already, one air force general has switched sides.

To achieve such a “soft coup” without violence, however, will require that Guaidó and his foreign backers, which include Canada and the United States, ensure the aid continues to serve a humanitarian purpose only. As Luis Almagro, secretary-general of the Organization of American States, puts it, “It is essential that [the aid] comes with solutions for the people. That is the best way to fight against hatred and repression.” Mr. Almagro calls this the “Gandhian” way of letting the people choose their leaders by allowing a delivery of aid across the border, whether with Colombia or Brazil.

The pro-democracy Guaidó is already regarded as the “right makes might” leader while the dictatorial Maduro relies on might to stay in power. Any use of force to block the aid should not be met with force by outside powers, such as the US.

Food must not be used as a weapon, as Maduro is doing in refusing aid so far even as millions of people go hungry. More than 3 million Venezuelans have already fled the country. The United Nations says another 2 million could leave this year.

Venezuela has become a contest of ideas – violent authoritarian socialism versus peaceful democracy. The aid arriving along the border is now there for the people – and the military – to show which side they are on. Butter can win over guns.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The power of honesty

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Karen Neff

When an employer’s payroll error left one woman’s family between a rock and a hard place, the idea that we all have a God-given ability to do what’s right brought courage and calm, and the situation was soon resolved fairly to everyone’s satisfaction.

The power of honesty

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing! My husband had just discovered that owing to a clerical error, his employer had been overpaying him for the past six months. He reported this right away and was told that until the money was repaid, his wages would be withheld. We were newly married, and this was a great hardship for us, since we had unknowingly spent the extra funds.

Someone advised us that in this situation we might have a legal right to keep the money, but in our hearts we knew this wasn’t what we wanted to do. We reasoned that if a friend had overpaid us, we wouldn’t take advantage of the friend’s mistake and attempt to profit from it. It seemed unethical and devoid of integrity to do so under these circumstances.

Nevertheless, feelings of injustice and indignity kept surfacing, since this mistake was not due to any deception on my husband’s part. And repaying the money would have wiped out our modest savings. We needed an answer, and soon!

We decided to address the issue in a way we had found helpful in challenges before: through prayer, which meant understanding the situation from a spiritual perspective. Through our study of Christian Science we understood that another name for God is Truth, and that each of us is actually God’s spiritual offspring, naturally reflecting His qualities.

To me, this means that the capacity to be upright and honest is inherent in everyone’s true identity. We have the ability to think and act with integrity because God expresses His nature and goodness in us.

I’ve found putting this into practice and expressing integrity in whatever I do is strengthening and empowering. The times I have been less than completely truthful have made me feel that I let myself down and abandoned my genuine sense of identity as God-created. As Mary Baker Eddy, the author of “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” says of the profound importance of honesty: “Honesty is spiritual power. Dishonesty is human weakness, which forfeits divine help” (p. 453).

As we prayed, we understood that we had an even higher mandate than just not trying to claim the money as legally ours. We saw that we were also being called to let go of any sense of blame for the clerical error that had been made, and these ideas about everyone’s natural ability to do what’s right gave us the courage to handle this situation from our own highest sense of right.

As we did, all feelings of injustice lifted. We saw the repayment of this money as an opportunity to be faithful to Truth. We also realized that God, Truth, could never cause us to be penalized for being honest and doing the right thing – reporting the error.

We repaid the money, yet shortly afterward our savings were replenished when we received an unexpected income tax refund that was within a few dollars of what we had paid out. While we were deeply grateful for the money, it couldn’t compare to the spiritual sense of strength and well-being we felt by being true to our spiritual selves as God’s children. That is a gift money can’t buy!

Each day is a new opportunity to demonstrate, through our actions, that God’s truth is a vital power operating in the world and blessing it. When we are striving to live up to our authentic being as God created us, up to our true potential, this blesses ourselves as well as those around us.

A message of love

Going up?

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow when Monitor education writer Stacy Teicher Khadaroo takes us to Concord, N.H., where the state attorney general is attempting to bring a new level of accountability to the handling of sexual assault at private schools.