- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

In Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Turning up the heat on cold cases

When a group of high school students recently faced an urgent deadline, they had an inspiration: Remember your audience. They drew as well on what they’d learned from three years of hard work: Never. Give. Up.

The deadline was the culmination of a project started by earlier members of a Hightstown, N.J., Advanced Placement government class. They’d been struck by how many cases remained unsolved from the civil rights era – how much justice had been denied, how many families had never gotten answers. So the students dug in. Their bill got the backing of Sen. Doug Jones (D) of Alabama and Sen. Ted Cruz (R) of Texas. It overwhelmingly passed both houses. They just needed one more thing to prevent it from dying as a new Congress started in January: President Trump’s signature.

So they started tweeting – at the president and anyone they could think of who might have his ear. And their message got through.

Their work is now law: the Civil Rights Cold Case Records Collection Act, which creates a national archive of related records. Tahj Linton, a senior, told The Associated Press he hopes it’s a harbinger of things to come. “If we can start to solve some of the racial problems that were never really closed in the past decades … maybe we can start to work on the ones that are happening today and make a difference about it.”

The act is particularly timely. Just check out Patrik Jonsson’s in-depth report today on the rising number of cold cases in the United States. Some 250,000 have piled up since 1980, once again disproportionately affecting people of color. But some cities are stepping up – making progress that could help to ease decades of distrust.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A murky scandal threatens Trudeau’s – and Canada’s – good names

You may not know it from abroad, but Canada is riveted by a scandal that could erode Justin Trudeau’s standing on rule of law, and even gender and indigenous rights. Could Canada be like everywhere else?

When Justin Trudeau was propelled to Canada’s highest office in 2015, it was his brand as a fresh and youthful face, positive politics, and a new and more transparent way of governance that drew the electorate to him. But now, as prime minister, he is caught up in a scandal that threatens to bring his government’s high aspirations back down to earth.

The scandal began after The Globe and Mail published a report earlier this month that alleged that the prime minister’s office put pressure on Jody Wilson-Raybould when she was justice minister to help a Quebec firm avoid criminal prosecution for its dealings in Libya. According to the newspaper, she resisted. She was demoted to veterans affairs minister in January and has since resigned.

Ms. Wilson-Raybould is a powerful symbol of Mr. Trudeau’s branding. She personified both his pledge to build a new relationship with indigenous people in Canada and his commitment to gender equality. That highlights the scandal’s contrast with everything that Trudeau stands for: a respite to the pressures squeezing the rule of law, human rights, and liberal values in the rest of the world.

A murky scandal threatens Trudeau’s – and Canada’s – good names

This week Canadians could start to piece together a political saga that, until now, has left the country with more questions than answers even as it threatens to undermine the leadership of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

The scandal, over whether the prime minister’s office pressured its justice ministry to help a Quebec firm facing fraud charges, has consumed the nation for the past two weeks. Each detail that has dripped into the public domain has generated multiple opinion columns and dominated airwaves.

Part of that scrutiny owes to the federal electoral season – with the opposition seizing on any whiff of Mr. Trudeau tainting the rule of law as the nation heads to the polls this fall. But it’s also captured public attention because it seems to stand in opposition to everything that Trudeau, and the Canada he represents, stands for: a respite to the pressures squeezing the rule of law, human rights, and liberal values in the rest of the world.

When Trudeau was propelled into power, it was his brand as a fresh and youthful face, positive politics, and a new and more transparent way of governance that drew the electorate to him. While more than three years of decisionmaking at the top have necessarily damaged his “real change” brand, he remains a beacon for many middle-power countries in the world, especially as the United States under President Trump has put into question the American commitment to a rules-based, international order.

Now Trudeau faces charges that his government is, essentially, just like everybody else’s.

A woman born to noble people

The scandal began after The Globe and Mail published a report earlier this month that alleged that the prime minister’s office put pressure on Jody Wilson-Raybould when she was justice minister to help SNC-Lavalin avoid criminal prosecution for its dealings in Libya. According to the newspaper, she resisted. She was demoted to veterans affairs minister in January and has since resigned – without revealing anything about why, citing solicitor-client privilege.

Ms. Wilson-Raybould is a powerful symbol of Trudeau’s branding. She both personified his pledge to build a new relationship with indigenous people in Canada as a historic reconciliation and his commitment to gender equality.

And while the main issue that could damage Trudeau concerns the rule of law, Alex Marland, author of “Brand Command: Canadian Politics and Democracy in the Age of Message Control,” says that gender and race add to the scandal at a sensitive moment.

“If the attorney general happened to be a white guy, to what extent would the story be an issue? It would still be an issue,” he says. “It’s just that because it happens to be an indigenous woman and this particular prime minister – and not even just the prime minister, it’s just the nature of society at the moment. It’s really a sensitive thing to have a white man and a prime minister demote an indigenous woman, especially in Canada where we’re going through this period of reconciliation.”

When the scandal broke, Trudeau immediately said he did not “direct” Wilson-Raybould to reach an out-of-court settlement with SNC-Lavalin, which faces charges of fraud and corruption. The firm employs 9,000 people in Quebec, a province that will be crucial for the Liberals in the election. But Trudeau’s carefully constructed statement only led to speculation that he was engaging in a semantics game because the government had something to hide. He tried to stifle it by saying her continued presence in his cabinet spoke for itself. The next day she stepped down, signing her resignation “Puglaas,” her name in her native Kwak’wala language, which means “a woman born to noble people.”

Days later Gerald Butts, Trudeau’s longtime friend and influential principal secretary, resigned. In his letter he said there was no untoward pressure placed on Wilson-Raybould, but his resignation only turned up the speculation.

It was only in testimony in the House of Commons justice committee last week that Michael Wernick, the clerk of the Privy Council of Canada, shed some light on a basic timeline of meetings that have taken place. He essentially admitted a degree of pressure placed on the justice minister but said that it wasn’t inappropriate.

This week Wilson-Raybould is expected to testify in front of that same committee, sharing her side of the story – and answers about the government’s alleged pressure. Canadians eagerly await her version, about which she has only said she hopes to “have the opportunity to speak my truth.”

Souring on Trudeau?

Pollster Nik Nanos of Nanos Research says Wilson-Raybould’s silence has been “devastating.” “It has allowed the opposition parties to project the worst possible interpretation of what happened.” Her testimony could reveal a major, minor, or even no problem for Trudeau, says Mr. Nanos. But it’s a risky moment nonetheless.

“First of all it includes the courts,” he says. “Second of all there’s a gender dimension. Third of all there’s an indigenous dimension. And finally and most importantly it involves the prime minister directly.”

A poll conducted by the firm Leger for The Canadian Press in the midst of the scandal this month showed 41 percent of respondents saying that they believe the prime minister did something wrong regarding the engineering company and the justice minister, while 12 percent believed he hadn’t. Another 41 percent were unsure.

Trudeau, while remaining popular abroad, has suffered in image at home similar to the way that former President Barack Obama did, says Mireille Lalancette, a professor in political communication at the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières. “Trudeau’s brand is not a blank canvas anymore. When he was elected, as was the case for Obama, they were all about the positive, so people could project anything on them. The fact that they need to make decisions and sometimes hard ones, this modifies the brand.”

The political damage is compounded by this being an election year, with opposition on the right and left seizing the moment to attack him. The case feeds into some of the older themes in Canadian politics, like favoritism played to Quebec.

Yet that Wilson-Raybould is an indigenous woman makes the scandal potentially far more damaging. Sources leaked to national media that Wilson-Raybould was “difficult.” One cartoon that was widely circulated showed Wilson-Raybould gagged and bound in the corner of a boxing ring. It drew widespread criticism for its apparent references of abuse both to women and indigenous people. Trudeau apologized for not condemning sooner such attacks.

Regardless of what happened, Wilson-Raybould’s removal from the justice ministry is widely perceived as a demotion – fueling criticism that Trudeau is not truly committed to the government’s relationship with First Nations, Inuit, and Metis peoples in Canada despite his rhetoric. In a June 2017 statement Trudeau declared that “no relationship is more important to Canada than the relationship with Indigenous Peoples.”

Nanos says that the case is disappointing for those who care about gender and indigenous issues. But he says Trudeau remains a strong advocate. “I think the reality is that for people who are interested in gender equality or indigenous issues, I’m not sure how they’re going to get any other prime minister that is more into and supportive of both of those.”

A deeper look

How cities are turning up the heat on cold cases

Unsolved murders are piling up in police departments, leaving killers on the streets and eroding public confidence. That’s pushing some urban areas to put more resources toward solving stubborn cases.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 12 Min. )

Across the country, unsolved murders are piling up on detectives’ hard drives. Driven by the changing nature of crime, a lack of staffing in police departments, and burgeoning caseloads, unsolved murders are rising inexorably in many American cities. More than 250,000 cold cases have accumulated since 1980. In 1965, US detectives routinely cleared nearly 90 percent of murder cases. Today, 40 percent of homicides go unsolved, according to the FBI Uniform Crime Report.

The rising cold case rate carries major implications. It leaves a growing number of killers out on the streets, undermines safety, and erodes confidence in the criminal justice system.

A growing number of cities, including New Orleans, are putting more resources into solving past and present cases, and independent groups are springing up that are hiring retired gumshoes to help police detectives solve stubborn murders.

In New Orleans, a year after men with semiautomatic weapons left Jamar Robinson slumped in the back seat of a red Altima, there’s a major development that might bring a modicum of closure to his family.

During a recent visit to her son’s grave, Judy Robinson turns on the video camera on her cellphone as she begins a conversation with Jamar. The headstone glimmers in the sun. Before the screen flickers out, she makes her son a promise.

“I will find you justice.”

How cities are turning up the heat on cold cases

Shortly after a Mardi Gras parade a year ago, a group of local residents decided to extend their revelry and congregate in the Lower Ninth Ward here outside the Robinsons’ house. As their activities wound down around 8 p.m., two young black men approached in a car. They rounded the corner onto St. Claude Avenue dressed in “matching” red, white, and black athletic wear, according to court documents.

Then came the horror: Police say the men opened fire with semiautomatic rifles. Children screamed, ran into the house, and hid in closets. Janice Robinson was standing in her doorway, watching bullets tear into a red Altima parked out front. More than 100 rounds were fired in all. It was too dark to see the shooters’ faces. They vanished quickly into the night. Amid the mayhem, the Altima pulled away from the curb, rolling slowly into a nearby gas station. When it was safe, Ms. Robinson raced over to the car with her niece. At first they saw their friend Byron Jackson in the front seat, shot in the head, but alive. Three other young men in the car had been wounded as well.

Then she discovered her beloved nephew, Jamar Robinson, slumped over in the backseat. Mr. Robinson, who had been a stand-out football player in high school, was unresponsive. Janice patted his face. “There was not a drop of blood on him, which was so strange,” she says. “There was some confusion about whether he had a pulse. But he was gone.”

Police combed the area the next few days, but no one immediately came forward to identify the shooters. As the first anniversary of that dark weekend approached, the Robinson family worried that Jamar’s killing was heading toward becoming one more example of a disturbing trend in the United States: the growth in the number of cold cases. “I just hope they can find who did it,” says Elisa Young, Jamar’s sister.

Across the country, unsolved murders are piling up on detectives’ hard drives. Driven by the changing nature of crime, a lack of staffing in police departments, and burgeoning caseloads, unsolved murders are rising inexorably in many American cities. More than 250,000 cold cases have accumulated since 1980. In 1965, US detectives routinely cleared nearly 90 percent of murder cases. Today, on average, 40 percent of homicides go unsolved, according to the FBI Uniform Crime Report.

The rising cold case rate carries major implications. It leaves a growing number of killers out on the streets, undermines safety in urban neighborhoods, and erodes confidence in the criminal justice system.

Yet the trend hasn’t gone unnoticed. A growing number of cities – including New Orleans – are putting more resources into solving past and present cases, and independent groups are springing up that are hiring retired gumshoes to help police detectives solve stubborn murders. There’s even been a major development in the Robinson case, which, if it pans out, might bring a modicum of closure to the family.

“Nobody in our entire family has ever been touched by this kind of violence,” says Judy Robinson, Jamar’s mother. “I wouldn’t wish this on any other mother.”

***

The first 48 hours of a murder investigation are critical. An investigative team sweeps in and establishes a framework that can be filled in with forensics and intelligence. In those first few days, witness recollections are fresh, the offender or offenders are scared and more prone to making a mistake. But as time grinds on, witnesses drop out or disappear. Memories fade. Clues become less concrete, and new cases demand detectives’ attention.

If hard evidence – fingerprints on a shell casing, for example – is lacking, witnesses become even more important when trying to build a case. The problem is that in many urban neighborhoods residents are hesitant to come forward, fearing retaliation or retribution. A cocoon of silence often envelopes the street.

“People clear out,” says former New Orleans homicide chief Jimmy Keen. “Nobody ever sticks around to talk.”

This is nothing new, of course. John Skaggs, a retired Los Angeles Police Department detective, points out that witnesses keeping quiet either out of fear or antipathy toward police is woven into the annals of US law enforcement going back to the Whiskey Rebellion in the 1790s.

But crimes and policing are changing today in ways that are exacerbating the problem. In decades past, neighborhood residents would notify police if there was a shooting or they thought there was going to be violence. Today, especially in many urban neighborhoods, gang members and others have become their own enforcers.

“Now a lot of times people are handling their own business on the street, and we only get called when there’s a dead body,” says Major Michael O’Connor, chief of Atlanta’s major crimes section. “Without witnesses, you have to backtrack to figure it out. Cases are more difficult by their nature today than they were before.”

A growing distrust between police and local residents often hampers investigations, too. Not long ago, Louisiana State University criminologist Peter Scharf was in a neighborhood testing a listening device that allows police to detect when gunshots are fired. “A guy walks up and says, ‘You guys really don’t like black people. That’s why you have all that technology. You don’t want to hang out with us.’ There was some truth to that,” Mr. Scharf says.

Others see the problems running far deeper than residents’ estrangement from police. In his work, Mr. Skaggs has consulted with more than 50 US police departments. What he’s found generally is a downward spiral of sometimes shoddy and lazy police work, societal indifference toward gang-on-gang crimes, and waves of violence traced to “street justice” – the chain of retributive killings common to murder zones.

“A big problem is that these homicide detectives aren’t spending enough time on the street,” says Skaggs. “They’re looking at their computer, at social media, everything except going to look for that live witness.”

Yet police practices alone aren’t to blame. Resources are lagging, too. In many cities, including Washington, there are a third fewer cops per resident on the force today than there were 10 years ago. And even when departments do get money, they are torn between spending scarce resources on beefing up neighborhood patrols or hiring more detectives to clear yesterday’s case files.

“We were asked by one mayor, ‘Why should I spend resources to solve homicides?’ ” says former Washington, D.C., Detective Eric Witzig. “That was a very good question.”

All this has led to expanding caseloads, even though violent crime is down in many US cities. In 2016, New Orleans cleared only 3 out of 10 murders. Detroit’s clearance rate was 15 percent. Skaggs says that within cities, in some of the “baddest neighborhoods,” departments might solve only 10 percent of the homicides.

The rise in caseloads is taking a toll on police morale. Often detectives get assigned a murder on Friday and another one on Monday, on top of having to investigate other kinds of deaths and officer-involved shootings.

As a result, being a detective is not always the coveted job on the police force it once was. In 1970s New Orleans, local cops say, detectives used to hang out in their nattiest attire in some of the trendiest restaurants in the French Quarter – they were the kings of Bourbon Street. Today, US detectives in murder-heavy cities such as Chicago, Memphis, and New Orleans are more apt to be desk jockeys who spend their days poring through ever-growing files of unsolved murders.

“I had a real tough guy who decided to quit,” says Mr. Keen, the former New Orleans homicide chief. “He told me, ‘The bodies keep following me around.’ ”

***

The Calliope housing projects in New Orleans got flooded in hurricane Katrina, so today suburban-style townhouses dot this part of town, which is also dominated by bodegas selling a local staple – catfish po’boys. Yet the tranquil scene on the streets masks something much more insidious underneath.

The Calliope, in fact, remains one of America’s most violent urban areas, a nexus of the heroin and fentanyl trade. Organized street gangs such as the Goon Squad and Birdman Gang compete for heroin-dealing territory. The Central City neighborhood, of which the Calliope is a part, represents a microcosm of the murder and silence-of-the-street mentality at the root of the “clearance crisis.” In the beginning of December, a body lay in one of the streets. On Christmas Day, the man who police believe killed him was found dead himself just around the corner. No one reported seeing anything, in either slaying.

Living in such neighborhoods “teaches you to fear,” says New Orleans scrap dealer Al Smith, who grew up in the Calliope, before, as he puts it, the AR-15 assault rifle replaced the “Saturday night special” as the local weapon of choice.

Recently, Ameer Baraka, the 30-something actor and producer, was walking down a street in the neighborhood when an older man on a bicycle called out to him: “Hey, Millie, how ya doin’?”

Millie is Mr. Baraka’s old nickname and, today, a dark alter ego. “Yeah, I was one of these guys,” says Baraka, a star of the TV series “American Horror Story.” Baraka killed a 14-year-old rival back when he was young, landing him in prison for several years for manslaughter.

Today he still comes back to the Calliope, in part to save it. He works with children’s after-school programs in a gym with a Muhammad Ali mural on the wall. He runs a foundation that tries to address the root causes of urban despair and acts as a mentor at local prisons.

The author of “The Life I Chose” says the cycle of violence can be stopped by solving one case at a time. The work of detectives is crucial to doing that, he believes, even though he was once on the opposite side of the law from them. “It is easy to beat a charge,” he says. “That is why [people] kill.”

He recalls one particular local drug don – “great guy until you crossed him” – who was seen committing murder in broad daylight. The witness, a barber, talked to the police. A few days later, the barber lay dead with 19 bullet wounds.

But the kingpin is now at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, the state’s maximum security prison nicknamed “Angola.” A white bicyclist happened to pass by and volunteered his account to the police. It was enough to win a conviction.

“It took a white guy to put this guy in prison,” says Baraka. “And he doesn’t have to worry. None of these guys know where he lives. We’re talking literally about two separate worlds.”

After the Christmas Day slaying, Lionel Piper, who introduces himself as a local clergyman, nailed homemade signs all over his Central City neighborhood, urging people to reject drugs and the murder that too often comes in their wake. The next morning the signs were all ripped down. Another church put up signs saying “Thou shall not kill,” using heavy-duty roofing nails. So far, they remain.

Mr. Piper takes time from meditating on his stoop to talk about the violence in his neighborhood. He says police can only do so much to curb the problem, though he believes clearing cold cases is worth the effort. To actually stop the killing cycle, he says, squinting into the sun, requires something deeper and more individually redemptive – “a harder look at God.”

***

Until that happens, cities will have to rely heavily on the efforts of law enforcement authorities. Public outcry over deaths such as Robinson’s is forcing police departments to recognize the importance of justice for all – even for young black men killed unceremoniously in the streets, and for their families. As part of that shift, police are seeing increasing value in the importance of solving cold cases.

Cities such as Savannah, Ga.; Memphis, Tenn.; and Charlotte, N.C., have all formed special cold case squads, bringing in older detectives to reexamine unsolved murders. Skaggs serves on one such group in Inglewood, Calif., that recently cleared several dormant cases solely by digging up old witnesses who suddenly had something new to say.

The Murder Accountability Project, a nonprofit that maintains the largest archive of homicides in the US, is pushing for reforms that could help police departments solve current and past murder cases. It is trying to convince “city mothers and fathers to provide the necessary resources to cops,” says Mr. Witzig, the former Washington detective, who is MAP’s vice chairman.

Chicago Police Superintendent Eddie Johnson announced in December he is adding 50 sergeants to oversee the homicide division “to ensure proper case management and provide supervision and mentorship to detectives.” That move came partly in response to a three-day span last August when 70 people either died or were wounded in 40 separate shootings, with police making arrests in only three of the cases.

In Boston, proliferating street cameras have proved useful to solving tricky gangland murders, helping the city increase its homicide clearance rate, while in Atlanta police have formed a “hat squad” of detectives. Named after the fedora-wearing sleuths of yesteryear, the group is using old-fashioned techniques to solve modern crimes.

“The main thing is, these cases don’t get solved behind people’s desks,” says Mr. O’Connor of the Atlanta Police Department. “People will tell you what happened, but you have to be out there to give them the opportunity to do so. They’re not going to come into headquarters and tell you.”

***

Halfway through 2018, New Orleans experienced a sudden slowing in the number of murders being committed on its streets. It gave the city’s detectives some breathing room to solve more cases. The Robinsons hope the investigation into their son’s death will be one of them.

On Jan. 22, a federal grand jury did indict two people in connection with the killing of Robinson and Mr. Jackson, the man in the front seat who initially survived the shooting but later died. It charged Kendall Barnes and Derrick Groves with two counts each of second-degree murder in the quintuple shooting outside the Robinsons’ home. That indictment joins another one containing multiple counts of felony drug trafficking and weapons charges against the two men.

Mr. Barnes’s lawyer says he has footage showing his client in the French Quarter just minutes before the shooting, making his presence in the Lower Ninth Ward all but impossible given the traffic on Fat Tuesday. Both men have pleaded not guilty to the charges.

The indictment details an extensive heroin and fentanyl ring, reinforcing what former New Orleans Police Superintendent Michael Harrison had earlier said when he called the case a murder “linked to vicious gang violence between people who know each other.”

That statement did not sit well with the Robinson family. Neither Robinson nor Jackson had criminal records. The family instead portrays Jamar Robinson as a gentle person who was a star safety in high school and played football in college as well. He had recently been approved for a mortgage and bought his first house. He had also gotten a special license that allowed him to transport hospital patients. He was, his family says, a good dad to his 2-year-old son.

Yes, he dressed with impressive street bling. But days before the shooting, he had mysteriously begun to give all his fashion items away, shocking his mother. After his death, the family found nothing left of his to clean out.

“This is bigger than the [New Orleans Police Department],” says his sister, Eugencia Green. “This is the justice system, the courts, the juries, our society. This is much bigger than Jamar’s death.”

Detective Maggie Darling with the New Orleans Police Department has been the main person handling the case, though the FBI has been heavily involved because of the use of an AR-15 and alleged links to an organized drug trade. She has not given the family much detail, but press reports suggest that someone came forward by mid-May of last year, identifying Barnes out of a six-person line-up – an exception to the no-snitch culture that may have led to fresh leads.

To Skaggs, such acts of civic duty underscore that “85 percent of the people in these neighborhoods are law-abiding people, who like and respect the police.”

The family plans to be in court when the trial gets under way, to show their faces to the jury, wearing pins with photos of Jamar.

During a recent visit to his grave, Judy Robinson turns on the video camera on her cellphone as she begins a conversation with Jamar. The headstone glimmers in the sun. Before the screen flickers out, she makes her son a promise.

“I will find you justice.”

Afghan women on alert: What would peace with Taliban mean for them?

As the US negotiates an Afghanistan withdrawal, many women are, unsurprisingly, worried that their hard-won gains are at risk. But our correspondent found a spirit of determined optimism too.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

The Taliban imposed strict rules when they controlled Afghanistan in the late 1990s, and the severe restrictions upon women are perhaps the most widely remembered. So the status of women is a key issue as US-orchestrated peace talks with the Taliban aim to end America’s longest war and involve the Islamist group in government again. American officials, who are meeting Taliban chiefs Monday, have said any peace deal must include protecting gains for women and civil society.

In Kabul and other Afghan regions, some women cite years of progress for women as a cause for hope. Online journalist Freshta Farhang says that after a cease-fire last year, “the Taliban comprehended that women have active participation everywhere, in education, in the economy.” She says people on both sides have “seen each other, that they are all Afghans, that they are all humans, all Muslims.”

But uncertainties persist about what comes next. Shogofa Sediqi of Zan TV says call-in programs reveal concerns about opportunities for women if there is peace with the Taliban. Women in rural areas, she says, “want changes.”

Afghan women on alert: What would peace with Taliban mean for them?

The Taliban imposed strict rules when they controlled Afghanistan in the late 1990s: Attending Friday prayers in the mosque was mandatory, for example, enforced with beatings at the end of a whip.

And music and images of people were forbidden, so Taliban checkpoints were marked by shimmering clouds of magnetic tape, which was pulled from music and videocassettes confiscated from passing motorists.

But it was the severe restrictions inflicted upon women two decades ago that are most widely remembered: The Taliban forced women to be chaperoned and wear the all-enveloping burqa in public, and barred them from working or getting an education.

Those memories are creating widespread concern among many Afghan women, especially, as US-orchestrated peace talks with the Taliban advance. Zalmay Khalilzad, the US special representative for Afghanistan reconciliation, resumed meetings today with the highest Taliban delegation yet, led by Taliban co-founder Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar.

US negotiators are seeking an end to America's longest war, and the Islamist Taliban a return to government. American officials say any peace deal must include protecting gains for women and civil society.

The fear of a Taliban return to power in some form, and the risk of renewed harsh social restrictions on women, is encapsulated by a leaflet seen in Kabul.

It shows a Taliban man in the street beating women wearing blue burqas years ago, and reads: “Afghanistan will not go back!”

But even as some fear a return to medieval Taliban attitudes toward women, other Afghans say that such a retreat is unlikely: Afghanistan has moved on from late 2001, when the US military engineered the toppling of the Taliban, and women have since enhanced their role.

“Can the Taliban take us back? No, it’s almost impossible,” says Farkhunda Ehssan, who works at Zan TV, which aims to empower Afghan women with a constant diet of shows highlighting women’s issues and progress.

“Women’s TV” is one front line against a retrenchment of Taliban ideas, with its female directors and journalists, and mostly women staff, who are tangible proof of forward movement.

“The Taliban will face a completely different Afghanistan.... They will face women with much more power in the economy, in society, and in media especially,” says Ms. Ehssan. “Now is not the time they should impose something on us.”

Promises, with caveats

Taliban leaders – negotiating sporadically with US diplomats in Doha, Qatar, and Afghan opposition figures in Moscow – suggest that some gains for women will be preserved. But they also say that “rights” granted to women are subject to opaque standards of “Islamic rule” and “Afghan culture.”

“Yes, I’m telling you that [women] can go to school. They can go to universities. They can work,” Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai, the Taliban political chief, told the BBC earlier this month in Moscow.

The sincerity of that apparent change of heart is a key topic of debate among Afghan women, who make up half of the 65 percent of the population too young to directly remember Taliban rule.

“There are lots of changes in the last 17 or 18 years in our country. People have changed, minds changed. So these changes also had a positive affect on [changing] Taliban minds,” says Freshta Farhang, 21, a reporter with the Kabul online newspaper Khabarnama.net.

“There is a lot of difference between the old Taliban and the new Taliban,” says Ms. Farhang, who was born in Ghazni Province, southwest of Kabul. A key moment came last June, during a three-day cease-fire when Taliban militants and Afghan security forces alike put down their weapons and many people crossed the front lines.

“After the cease-fire, the Taliban comprehended that women have active participation everywhere, in education, in the economy,” says Farhang. Now people on both sides “are ready – they’ve seen each other, that they are all Afghans, that they are all humans, all Muslims.”

Many Afghan women “will never accept the Taliban again. But what we should focus on is peace,” says Farhang. “It’s the violent conflict that has a negative effect on education and every kind of development.”

Violence toward civilians and women

Not all Afghans are convinced of Taliban 2.0’s credibility. But it’s also not just in the 12 percent of Afghan territory the Taliban control, and the 34 percent they contest – according to US military figures published Jan. 31 – where issues of misogyny, child brides, and honor killings persist.

The United Nations released a report Sunday that tabulates a record number of civilian casualties in 2018, underscoring the need for peace, even as all sides ramped up offensive operations last year to gain leverage in the talks. The UN reported 3,804 civilian deaths last year, an 11 percent rise over 2017. Of those, US forces killed 674 Afghan civilians, the UN noted, nearly all in the Pentagon's ramped-up air campaign.

The UN noted that Taliban attacks on civilians nearly doubled in 2018 compared with 2017. The result is that – during a Taliban insurgency over the years against forces of the US, NATO, and the Western-backed government – the toll by militants has also included thousands of civilian lives.

For women, the poisoning of food and wells at schools for girls, to dissuade them from going to school, has been one sign of unchanged attitudes. Still, the Taliban have sometimes tailored their rules according to local concerns – allowing schooling for girls to continue in places that have come under their control.

“The fear is widespread, among the Afghan young generation particularly,” says Orzala Nemat, director of the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit, a think tank in Kabul. They “have no direct memory of how the Taliban rule, but remember very well how the Taliban treated them as students at school, and their fathers, uncles, and brothers in the [Afghan] National Army.”

She recalls working clandestinely during Taliban rule in the late 1990s, running secret home-based literacy classes for women and girls. It was risky but possible, whereas the experience of Afghan youth is of a Taliban “who have used terrorism as a weapon to terrify the people, who have bombed schools, mosques, public spaces, and killed civilians,” says Ms. Nemat.

‘We don’t want to go back to 2001’

One step to ease women’s concerns is being taken by President Ashraf Ghani, even though his government is not yet part of the US-led peace talks. The Taliban refuse to meet with what they call a Western puppet regime.

Mr. Ghani recently convened a daylong meeting to discuss key elements of a sustainable peace with women and other Afghan stakeholders.

“One thing common among the women was they said, ‘We don’t want to go back to 2001, under any circumstances. We don’t want to sacrifice our rights to have peace,’” says Razia Arefi, the country manager for the Belgian nongovernmental organization Mothers for Peace, who attended the meeting.

“Peace is not only to stop the firing and shooting and all these wars; peace is that we have the rights to education, to vote and to have our equality, which is mentioned in the Constitution,” says Ms. Arefi. She says if the Taliban “really believe in women’s rights” they should include a woman on their negotiating team.

That is unlikely, and the initial peace “framework” agreed with the Taliban makes no mention of civil society issues, but only a US military withdrawal in exchange for the Taliban preventing transnational terrorist attacks from Afghan soil.

The 50 percent of Afghan society who are women “must be heard and included” in peace talks, the US Ambassador to Afghanistan John Bass tweeted last week. “Afghanistan has made substantial progress on rights of women to live fully, participate in public life, and achieve their full potential.”

The urban/rural gap

What will happen in practice is far from clear, if peace with the Taliban is reached.

“There might be, even in provincial capitals, a temporary slump in women’s rights, media rights, and everything else. But in very rural Afghanistan right now, these are the conditions that are prevailing anyway,” says a Western official in Kabul who asked not to be named.

“In urban areas, of course, it will be a shock to the system. You can’t just make peace for people just in urban, progressive areas,” says the official. “If you are a woman in urban Mazar-e Sharif, you have different aspirations, ideas, and values than a woman in rural Helmand province. They might both be happy where they are, as long as they have been left alone.”

But leaving women alone is not what the Taliban are known for.

“Now the nation is against Taliban views,” says Shogofa Sediqi, the chief director for Zan TV, who told the Monitor last year that the channel’s purpose was to “work on people’s minds” to show “what women can do.”

Call-in programs register the same concerns, she says, about fewer chances for women if there is peace with the Taliban. “When I hear the views of women in rural areas, they are not happy with those conditions and they want changes,” says Ms. Sediqi.

And there is distrust in Kabul of a Taliban presence, says Najwa Alimi, a Zan TV correspondent from the remote northeastern Badakhshan province, who reports in Kabul on suicide attacks and military forces.

“I lost a relative in a suicide attack, and personally I will never forgive the Taliban.… I will never be at peace with them,” says Ms. Alimi, 24, who wears a headscarf with a peacock feather design, in camouflage colors.

She will be “the first person to take up weapons” against the Taliban, she says, if the government proves weak, is “unable to protect us,” or caves in to Taliban demands that don’t respect the rights of women and others.

“This is not only my voice,” says Alimi. “There is a huge group of the younger generation that have the same views.”

Points of Progress

More than just grass: US prairies make a comeback

Grasslands have long been underappreciated ecosystems. Yet the past three decades have seen progress in restoring them – giving a boost to numerous rare plants and animals.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

In the 1980s, the idea of prairie conservation started gaining serious momentum. And over the past three decades, a dedicated community of conservationists and land managers has worked to preserve American grasslands. Why bother?

“Prairies in particular have high amounts of biological diversity, and that diversity helps sustain life on Earth,” says Tom Kaye, executive director and senior ecologist at the Institute for Applied Ecology in Corvallis, Ore.

And people just plain enjoy exploring them. Reserve managers report that public interest increases as opportunities for interaction grow. A rough estimate for preserved prairies in the Great Plains area alone is around 207,000 square miles of tall-, mixed-, and shortgrass biomes.

“The most hopeful thing is that we have come a long way in our ability to restore prairie,” says Chris Helzer, director of science for The Nature Conservancy in Nebraska. “As climate continues to change and [agricultural] policies continue to change, there will be opportunities where it makes sense for society to put some of the land in farms back into prairie habitat – and when that happens, we’re ready to do it. We have the ability to do it.”

More than just grass: US prairies make a comeback

A vibrant sea of grasses once flowed across the North American continent: the great prairies that Laura Ingalls Wilder described as “spreading to the edge of the sky.” All but a fraction vanished during the 19th century as migrants from Europe advanced across the heart of America, plowing the land into farms and settlements. But not many people paid attention then.

Even many of today’s prairie conservationists agree that grasslands are underappreciated ecosystems. “Most people, I think, would drive past a prairie and just see a lot of boring grass,” says Chris Helzer, director of science for The Nature Conservancy in Nebraska and author of a popular prairie photography blog. “Prairies are not an ecosystem that smack you in the face with beauty if you’re not tuned into it.”

But in the 1980s, a prairie conservation movement that had been gradually growing since at least the 1950s started gaining serious momentum. Over the past three decades, a dedicated community of conservationists and land managers has worked to preserve American grasslands in all their manifold forms: the tallgrass, shortgrass, and mixed-grass prairies of the Midwest, as well as lesser-known varieties, such as the northwest prairies in Oregon and Washington, or the sandplain grasslands in Massachusetts. Since the ’80s, conservationists have made significant progress in their ability to reestablish and care for prairie ecosystems.

“The future of prairie restoration is headed in a good direction. We’ve learned some lessons,” says Tom Kaye, executive director and senior ecologist at the Institute for Applied Ecology in Corvallis, Ore. “We’ve been able to focus on ... the research that’s necessary to continue to improve.”

And that research has paid off. Advances in seeding technology have allowed land recovered from farming and other uses to be more fully restored with native plants. And reseeded plants have an increased rate of survival, thanks to efforts to understand plant establishment, says Dr. Kaye.

Prairie burns – an essential part of grassland management in some areas – have become grounded in community efforts. “Very few organizations have the resources to maintain a burn program on their own,” says Peter Dunwiddie, an ecological consultant and affiliate professor in the biology department at the University of Washington in Seattle; he studies prairies in the Pacific Northwest. “It’s hugely helpful to build these partnerships with a lot of different entities, so that everybody can work together.”

The exact acreage of prairie conservation efforts is somewhat difficult to track, since many are grass-roots endeavors. A rough estimate for preserved prairies in the Great Plains area alone is around 207,000 square miles of tall-, mixed-, and shortgrass biomes. But there are countless small preserves scattered across the United States, which can include areas as small as half an acre. And larger organizations, like the American Prairie Reserve, also tend to operate fairly independently. Conservationists are also used to finding land in unusual places.

“Military bases ... have become some of the last bastions for a lot of rare plants, rare animals, and rare communities. And in western Washington, prairies are a big one on Joint Base Lewis-McChord,” says Dr. Dunwiddie. He estimates that as much as 70 percent of the prairie reserves in Washington are on the base. Additionally, partnerships with private landowners and sometimes even ranchers play a big role in prairie conservation efforts.

Another species that benefits from restored grasslands is the bison. The Nature Conservancy alone manages over 113,000 acres of land with about 6,000 bison – including the Nachusa Grasslands near Chicago, which has almost 100 wild bison that have drawn significant public interest in the program. And ranches owned by media mogul and philanthropist Ted Turner have as many as 53,000 bison in managed herds. “It’s important from a bison conservation standpoint,” says Mr. Helzer. “But it’s also important because ... it gives more and more people a chance to see that sort of landscape with a big charismatic animal in it.”

It’s not all smooth sailing, though. “Temperate grasslands are one of the least-protected terrestrial biomes. They are traditionally the places that we have settled and plowed,” says Alison Fox, the chief executive officer of American Prairie Reserve. “The estimates are that less than 5 percent of prairies are in any form of long-term protection.”

Millions of acres of grassland have been lost in the Dakotas over the past few years as cropland expands. According to Dunwiddie, conservation laws that have helped fund and protect wilderness preserves, such as the Endangered Species Act of 1969, face ongoing legislative attacks.

Nevertheless, many conservationists are optimistic about the future, and they’re dug in for the long game. “I think the most hopeful thing is that we have come a long way in our ability to restore prairie,” says Helzer. “As climate continues to change, and [agricultural] policies continue to change, there will be opportunities where it makes sense for society to put some of the land in farms back into prairie habitat – and when that happens, we’re ready to do it. We have the ability to do it.”

From a practical point of view, prairies are good for the environment. “Prairies in particular have high amounts of biological diversity, and that diversity helps sustain life on Earth,” says Kaye. “Prairies also are huge carbon sinks.... Restoring prairie ties up a lot of carbon, so that it’s not in the atmosphere.”

And they are worth exploring, conservationists say. “We’ve certainly received increased interest as we’ve gone along, and I think [that’s happened] particularly as we’ve provided more opportunities for the public to come out and experience the landscape,” says Ms. Fox. Her organization, which is building one of the largest complete grassland ecosystems in the United States, depends almost entirely on private donations. It has found success in part by welcoming visits from the public.

Helzer, for his part, uses photography to draw attention to prairies. “Every time you go out to a prairie, you see different things, if you know what to look for,” he says. “There’s different flowers that are blooming, there’s different insects that are active.... If you can get people to go to any prairie – even a half-acre prairie across town – you can always see something new and different.”

And he believes that the experience of being in a prairie is something special all on its own. “[Prairies] are a really subtle system from an aesthetic standpoint. Standing out in the middle of a huge expanse of grassland, where you can’t see anything else except the waves of grass – it makes you feel a certain way,” he says. “It makes some people feel really small and scared, and it makes other people feel exhilarated. But either way, it brings out a strong emotion.”

Difference-maker

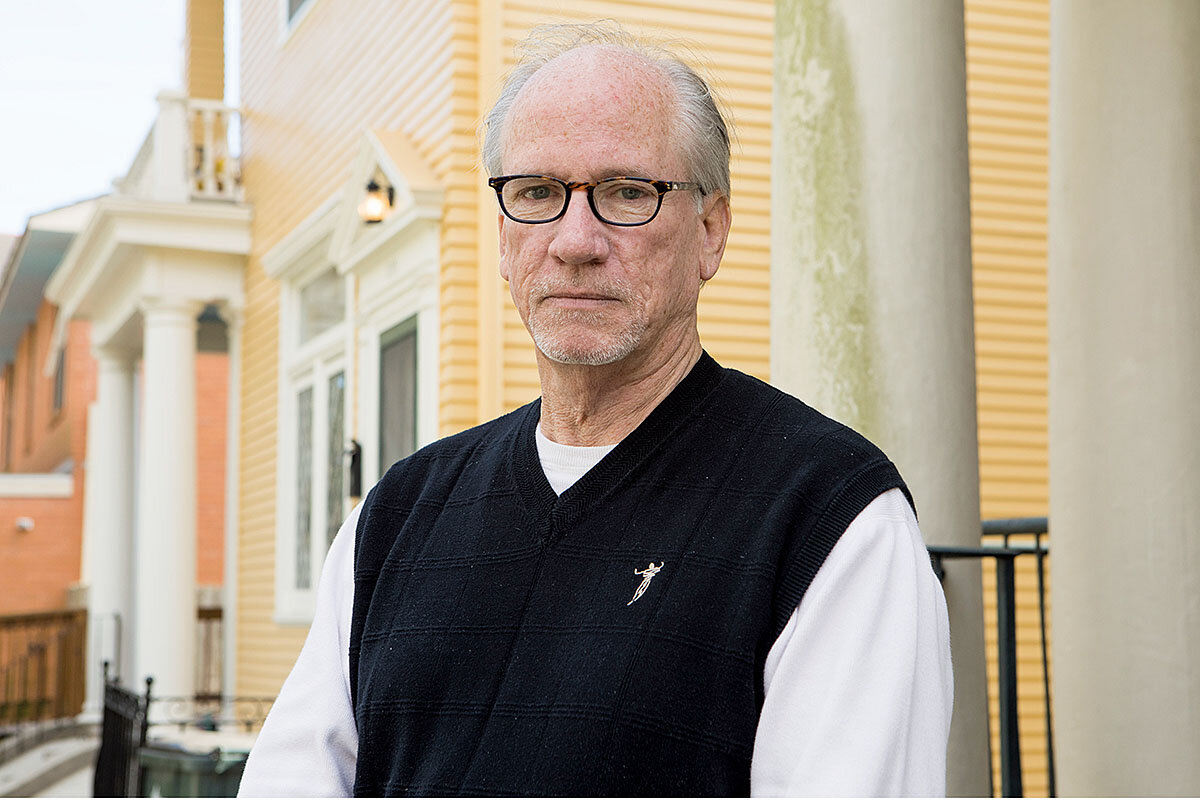

Block by block, a community activist builds a better Chicago

In African-American neighborhoods of the city’s South Side, Jahmal Cole works with young people and volunteers to improve lives and communities by changing the little things.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Richard Mertens Correspondent

People say Chicago is a city of neighborhoods. Jahmal Cole’s work begins at their humblest unit, the block.

“What could you make yourself do today that has a positive impact on your block?” Mr. Cole, founder of My Block My Hood My City (M3), asks his volunteers.

Lately Cole has turned his attention to block clubs. Block clubs have a long and distinguished history in Chicago’s African-American neighborhoods. Many formed during the Great Migration from the South and still have a strong presence, especially on the South Side. They foster community, bringing neighbors together for block parties, back-to-school fairs, and summer cookouts.

M3 grew out of Cole’s effort to connect young people with the world beyond their block. He discovered that few of them had ventured much outside their neighborhoods. He started what’s become a regular program of “explorations,” twice-a-week trips that take teenagers to different parts of the city, sometimes to learn about a business or profession, sometimes to visit an ethnic neighborhood and sample the food.

And Cole and his small staff organize days when volunteers come from different parts of the city to clean up a block. They pick up trash, mow vacant lots, and trim overgrown trees and bushes. “If you show somebody better, they’ll do better,” Cole says.

Block by block, a community activist builds a better Chicago

In the weeks before Christmas, volunteers descended on Chicago’s South Side to decorate Martin Luther King Jr. Drive. Block by block, they strung lights, hung wreaths, and unspooled yards of ribbon. They festooned houses, trimmed fences, and wrapped light poles in garland. At Washington Park, boys clambered up a crab-apple tree to hang ornaments from its branches. A man on a stepladder looped solar-powered lights over plastic cups stuck into a chain-link fence to read “Respect Life.”

Decorating MLK Drive was Jahmal Cole’s idea. Mr. Cole is an author, motivational speaker, community activist, and founder of My Block My Hood My City, an organization devoted to finding small but meaningful ways to make life better in the poor and middle-class African-American neighborhoods of the South Side. When local block clubs asked for help putting up Christmas decorations, Cole figured he could decorate the whole drive.

“I thought, I’m going to do as much as I can,” he says.

People say Chicago is a city of neighborhoods. Cole’s work begins at their humblest unit, the block. “What could you make yourself do today that has a positive impact on your block?” he asks volunteers assembled on a frosty December afternoon. “I believe you should start with the small things first.”

My Block My Hood My City – M3 for short – grew out of Cole’s effort to connect young people with the world beyond their block. He got the idea while volunteering with juvenile offenders at the Cook County jail. He discovered that few of them had ventured much outside their neighborhoods. They had never gone downtown. They had never swum in Lake Michigan. He started what’s become a regular program of “explorations,” twice-a-week trips that take teenagers to different parts of the city, sometimes to learn about a business or profession, sometimes to visit an ethnic neighborhood and sample the food. Recently, Cole took them ice-skating.

“If you show somebody better, they’ll do better,” he says. “If they don’t know no better, they’re not going to do better.”

Timothy Johnson, a high school junior, has gone on more explorations than he can count, riding into the city after school in Cole’s big white passenger van. “He’s like a father figure,” says Timothy, who has come to help decorate the drive. “We always talk to him if we have problems at home or school. He’s always asking how our day was. He’s always protecting us and showing so much love for us.”

Chicago’s block clubs

Lately Cole has turned his attention to block clubs. Block clubs have a long and distinguished history in Chicago’s African-American neighborhoods. Many formed during the Great Migration from the South as a way of introducing rural blacks to the norms and customs of city life. They still have a strong presence, especially on the South Side, where they work to keep their small corner of the city clean and safe. They also foster community, bringing neighbors together for block parties, back-to-school fairs, and summer cookouts. “They are the building blocks for community organization,” says Dick Simpson, a former alderman who is now a political scientist at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Cole wants to breathe new life into them. One way is by helping them replace their signs. Block club signs, mounted prominently on wooden posts at the end of streets, have traditionally laid down the law: “No Washing Cars,” “No Loitering,” “No Drugs,” “No Loud Music.” They have struck Cole as a little too negative.

“I thought, I’m going to quit saying no,” he says. “I’m going to say yes.”

The new signs accentuate the positive. Created by teenagers in a University of Chicago arts incubator, they’re less stern and more welcoming: “Love Our Neighbors,” “Where Residents Love Cleanliness,” “We Believe Everybody Is Somebody.”

“There’s a deficit of hope,” Cole says. “Our block club signs are a beacon of hope.”

Cole and his small staff at M3 also organize days when volunteers come from different parts of the city to clean up a block. They pick up trash, mow vacant lots, and trim overgrown trees and bushes. James Drake Sr., president of a block club on South Hermitage Avenue, was making repairs in front of his house last summer when Cole showed up with a crew. “He must have had 40 people,” Mr. Drake says. “What he’s doing is great.”

In a city with deep problems – violence, poverty, and racial inequalities – residents say sprucing up a block is important work. “It sends a message that you care about the block,” Drake says. “It also sends a message to the criminal element that ... maybe we need to go somewhere else to do our drug dealing or other criminal activity.”

Cole himself grew up poor, most of the time living with his mother and two siblings in communities north of the city. For two years he was homeless with his father in Fort Worth, Texas, he says, sleeping in the back of trucks, on porches, and in “crack hotels.”

“Poverty was a blessing for me,” he says. “I didn’t have a poverty of imagination. Once you sleep in a crack hotel and hear the drug addicts come up the steps at night, you don’t fear anything.”

Cole attended an alternative high school, where he was not a model student. And yet he did what few of his friends did: go to college. On a whim, he enrolled in an unlikely school, Wayne State College in Nebraska.

He had two enthusiasms then: basketball and hip-hop. He recorded CDs and sold them in dorms and on the street. He tried out for the basketball team and made it, a walk-on at a college where most players had athletic scholarships. He was “a high-energy kind of guy,” says his coach, Rico Burkett. “He was a first-in-the-gym-last-out kind of guy.”

Still, Cole’s potential was not primarily on the court, and Mr. Burkett urged him to focus his energies on school. “A lot of conversations with him were around raising his expectations,” Burkett says. These conversations, plus scholarship money to buy books, helped make Cole an A student.

Back in Chicago, he stocked shelves at Target before getting a job as a network administrator for a computerized trading company. His old boss, William Hobert, is today head of M3’s board of directors.

“It’s an organization and it’s a person,” Mr. Hobert says. “We follow Jahmal. He’s got incredible insight and foresight and is somebody that people feel really good following.”

‘Jahmal is opening that door’

M3’s operations are financed by donations as well as sales of M3-branded clothing such as sweatshirts and caps. The organization is a reflection of Cole’s personality – intense, charismatic, undaunted. When he sees a need and calls for volunteers, they usually come. After a snowstorm last year, he asked for help clearing the sidewalks where older people live. More than 100 shovelers showed up.

“I think it’s in people to want to help,” Hobert says. “But so many of us don’t know how or where to go and what to do. Jahmal is opening that door.”

Cole also writes books, which begin in personal history and end in uplift. He wrote his first, “Athletes and Emcees: A Motivational Story,” “to inspire kids who use athletics and rap as a way out of the ghetto,” he says.

Decorating MLK Drive went on over two weekends. The volunteers were a diverse collection of Chicagoans: black and white, young and old, North Siders and South Siders, well-off and poor.

“The goal is to get people from all different neighborhoods to come and interact with each other on a human level,” Cole says.

Dressed in bluejeans, a knit cap, and a jacket not quite thick enough for winter, he moved around restlessly, thanking volunteers and posing for pictures – acting part organizer and part celebrity. “Gold ribbon?” he said, rummaging in a plastic bin of ornaments and old Christmas lights. “We’ve got some ribbon here.”

It was the last day. The decorating was almost over. The volunteers were finishing up, leaving behind a sprinkling of color and light for many blocks up and down the drive. Meanwhile, Cole’s thoughts were already turning to new projects, new blocks that needed a hand.

“Some people in Chatham want us to do a cleanup,” he says. “That’s what we’re going to do next.”

• For more, visit formyblock.org.

Other groups with community initiatives

UniversalGiving helps people give to and volunteer for top-performing charitable organizations around the world. All the projects below are vetted by UniversalGiving; 100 percent of each donation goes directly to the listed cause.

• i-Care Fund America, which has a focus on Pakistan, is a donor-advised fund, meaning participants can manage tax-deductible giving over time. Take action: Help buy clothes for children in low-income communities.

• Rural Communities Empowerment Center provides resources and services to improve levels of literacy in Ghana. Take action: Donate funds to build information and communication technology systems.

• Achungo Children’s Centre gives food, clothing, education, and medical aid to more than 200 orphans and other children in rural Kenya. Take action: Serve the needs of youths as a community health intern.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Hong Kong bars China’s notions of law

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In a speech last year, Chinese leader Xi Jinping reminded his country that rule of law really means “the law of governing by the Communist Party.” That is not the case in Hong Kong, which inherited the common law system from its time as a British colony. There, judicial independence remains one of its most-cherished assets.

Britain returned Hong Kong 22 years ago on the condition that it could keep its form of government under a “one country, two systems” arrangement until 2047. But with Mr. Xi’s rise to power, the party has steadily flexed its muscle in the territory.

The latest challenge to Hong Kong’s judicial autonomy comes in the form of a proposal to amend the extradition law. The change would allow fugitives wanted by China to be sent to the mainland at the discretion of Hong Kong’s chief executive, who is handpicked by Beijing.

If approved, Hong Kong’s reputation as a safe place for businesspeople and travelers to enjoy high standards of justice could be jeopardized. Liberty has been the lifeblood of this city of 7 million people.

Judges “are aware that faith in the judiciary once lost, can never be regained,” said retired judge Robert Tang in a farewell speech last December.

The resistance to the extradition proposal is a key test of how far the Communist Party will go to squelch the universal value of rule of law. When a society embraces the idea that certain principles must remain above politics, it flourishes. The rest of the world can only admire – and support – what the people in Hong Kong are demanding.

Hong Kong bars China’s notions of law

In a speech last year, Chinese leader Xi Jinping reminded his country that rule of law really means “the law of governing by the Communist Party.” In courts across the mainland, the Marxist party often wields the law merely as a tool to cling to power. That is not the case in Hong Kong, a small piece of China that inherited the common law system from the time it was a British colony. There judicial independence remains one of its most-cherished assets, ensuring equality before the law.

Britain returned Hong Kong 22 years ago on the condition that it could keep its form of government under a “one country, two systems” arrangement until 2047. But with Mr. Xi’s rise to power in 2012, the party has steadily flexed its muscle in the territory, putting the courts there under increasing strain. Nonetheless, Hong Kong still ranks 16th in a global index of rule of law by the World Justice Project. In contrast, China ranks 75th.

The latest challenge to Hong Kong’s judicial autonomy comes in the form of a proposal by its government to amend the extradition law. The change would allow fugitives wanted by China to be sent to the mainland on a case-by-case basis at the discretion of Hong Kong’s chief executive, who is handpicked by Beijing. Although the courts will review the arrest warrant, critics say Beijing could easily misuse it for political purposes.

One of the strongest criticisms comes from the well-respected chairman of Hong Kong’s Bar Association, Philip Dykes. He said the measure requires “anxious scrutiny.” In a column, he notes that though the territory has entered into fugitive surrender agreements with at least 19 countries, it may not have done so with China because of “perceived inadequacies” in the mainland’s criminal justice system.

If the proposal is approved, Hong Kong’s reputation as a safe place for business people and travelers to enjoy high standards of justice could be jeopardized. Liberty has been the lifeblood of this city of 7 million people, from avoiding the worst of the upheavals that embroiled China to enjoying an uncensored internet today.

The people of Hong Kong have a history of pushing back on Beijing’s attempt to curtail their freedoms. In 2003, for example, some 500,000 people took to the streets to protest a government-sponsored security bill, whose vague wordings stoked fears that it would be used to suppress dissent. The bill was later shelved.

In 2014, when China essentially denied universal suffrage in Hong Kong and called for its judges to be “patriotic” – a term used to mean loyal to the Communist Party – students led a monthslong protest known as the Umbrella Movement. Two years later, as many as 2,000 lawyers marched to protest Beijing’s interference in the ouster of two newly elected legislators who had expressed support for an independent Hong Kong.

The courts, of course, play a crucial role. Judges “are aware that faith in the judiciary once lost, can never be regained,” said retired judge Robert Tang in a well-received farewell speech last December.

The resistance to the extradition proposal is a key test of how far the Chinese Communist Party will go to squelch the universal value of rule of law. When a society embraces the idea that certain principles must remain above politics, it flourishes. The rest of the world can only admire – and support – what the people in Hong Kong are demanding.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

In the heart of our cities, an unshakable stronghold

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Joni Overton-Jung

Today’s contributor shares spiritual ideas that lifted her fear when she was traveling alone on a city bus in a troubled neighborhood – and buoyed her hope for the possibility of greater peace in urban settings and beyond.

In the heart of our cities, an unshakable stronghold

When people heard what neighborhood I lived in, they often asked about its safety, gang activity, crime. I usually had to pause before answering. Images of neighbors and gang members whose names I’d learned and sounds of gunshots and sirens flooded my thought.

It was a challenging, exhilarating time. Could I count the times I was mentally on my knees in prayer? Probably not, but neither could I count the ways I’d seen the hand of God tenderly at work – uniting, reassuring. I saw how God’s care comes in the form of intuitions that direct us and give us confidence. This inner voice is sometimes quiet, sometimes loud, but always it comes with the assurance, calm, and conviction of limitless divine Love.

I recall how one night I was taking public transportation home by myself and found myself filled with fear. I was the only woman on the bus, and I had a good five-block walk home once I got off.

As we rode along, I felt an urgency to pray and reached out to God with my whole heart. I thought about things I’d been learning in my study of Christian Science about the ever presence and power of God’s love.

Fear lost its hold on me in those moments as I pondered just how loved, precious, and mighty each one of God’s children is, as the very expression of God – of divine Love, Life, Truth. Certainly this expression includes no predisposition to fear or violence.

I thought of Christ Jesus’ example – with all that he faced, he showed how we too can face down fear and hatred with love, forgiveness, and compassion. At one point he said, “There shall be signs in the sun, and in the moon, and in the stars; and upon the earth distress of nations, with perplexity;... men’s hearts failing them for fear.... And when these things begin to come to pass, then look up, and lift up your heads; for your redemption draweth nigh” (Luke 21:25, 26, 28).

Even when things feel overwhelming or scary, right in those moments we can “look up” mentally, spiritually; we can open our hearts to God’s ever-present, constant power. There is always something so much deeper going on than what things look like on the surface – something invulnerable, indestructible, ready to be discovered: the integrity of our true being as God’s loving, safe, spiritual creation.

My walk home from the bus that night was peaceful. I didn’t hurry. I listened to the sound of snow crunching beneath my feet, watched for stars and airplanes. I felt a lightness grounded in knowing that God was “walking” me – and everyone, everywhere – home, right then and always. I felt more concretely than ever before that the understanding of God’s allness was more than ample to bring peace and security, no matter whom I came into contact with. It was a deeper safety than I had ever felt – a glimpse of the divine presence always at hand to meet every need. And I arrived home happy and safe.

That experience, along with many others, has given me such hope for greater peace in our cities and beyond. But healing our communities doesn’t take place with just one prayer. It takes a moment-by-moment willingness to let go of our own judgments and fears. In a poem titled “Satisfied,” Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, writes:

Aye, darkling sense, arise, go hence!

Our God is good.

False fears are foes – truth tatters those,

When understood.Love looseth thee, and lifteth me,

Ayont hate’s thrall:

There Life is light, and wisdom might,

And God is All.

(“Poems,” p. 79)

There is no place where we can be cut off from the power and presence of God. An earnest, understanding reliance on divine Love brings freedom from fear and danger. Beginning with our own hearts, each of us can contribute to combating fear, hatred, resentment, and prejudice in our cities, our families, and in the world.

Adapted from an article published in the Aug. 7, 1995, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Frozen history

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Here’s something to think about for tomorrow: If kids naturally ask existential questions, why don’t we teach them philosophy at a younger age? That’s what some educators in France are pushing for. I hope you’ll check out our story and see if you agree with them.