- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

For economists, a new calculation: the value of humanity

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

It might just be that economics is getting a heart. In recent years, we’ve seen dramatically what can happen when economics ignores the heart. We’ve seen the world remade by the promises of globalization, which to economics looks like a gigantic win: more wealth generated, fewer people in poverty, greater interconnection.

Yet while all those things are unequivocally true and positive, they also skate over the disruption to human lives: jobs lost to big cities or other countries, downtown storefronts shuttered, rural communities weakened.

Did any of that matter? Not really, economists said. The net benefits outweighed the cost. The calculus wasn’t even close, truth be told. So we went headlong into globalization. But the explosion of political upheaval in the West – not to mention rising inequality in many nations worldwide – is now forcing a rethink. Perhaps overlooked in the economic calculus was the value of humanity itself.

In his new book, “The Third Pillar,” economist Raghuram Rajan argues that communities matter. Along with the state and markets, they undergird society, and when community is weakened, society falters even if the overall economic picture is improving. Without the essential variable of human warmth, it seems, even the most compelling economic calculations end up incomplete.

Now on to our five stories today. We look at why Russia loves Putin the Great Builder, what a Maine town tells us about the future of food, and how an unusual tradition tells a deeper story about the people of the Persian Gulf.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Mosul: Does slow reconstruction risk a return of ISIS?

Terrorism isn’t born just of religious fanaticism. It breeds in lack of opportunity and despair. That is why we visited Mosul, Iraq. Residents say that, nearly two years after the city’s liberation from ISIS, they need fresh reasons to hope.

When ISIS was forced from the Iraqi city of Mosul, polls in “liberated” Sunni-dominated regions found 75 percent support for the idea Iraq was going in the right direction. But nearly two years later, much of Iraq’s second city is still in rubble, with few services and little rebuilding. In October, according to polling by the Washington-based National Democratic Institute (NDI), support had fallen to only 24 percent.

“Why is this happening? Because military gains have not been met by political reform, by economic reform, by services, by creating jobs,” says Ancuta Hansen, the NDI’s Iraq resident director, speaking at a security conference in Sulaymaniyah, Iraq. “And as ISIS has been defeated, people start thinking back to those everyday issues and see that their lives … are not changing.”

Today there is growing concern among Iraqis and Western officials that the lack of palpable progress risks rekindling the anti-government, pro-ISIS ideology. “The people of Mosul cannot wait any longer,” says Ramon Blecua, the European Union ambassador to Iraq, at the conference. “People need to see some real success stories on the ground and have hope that things are going to change.”

Mosul: Does slow reconstruction risk a return of ISIS?

Nearly two years after the liberation of Mosul from Islamic State militants, what hasn’t changed is that much of Iraq’s second city remains rubble, with limited services and little rebuilding.

What has changed is that the high expectations from that July 2017 liberation – of a post-ISIS renaissance in Mosul bolstered by an infusion of Western and Iraqi government cash and goodwill – are receding as frustration sets in.

Instead of hope, in fact, there is growing concern among Iraqis, Western officials, and aid groups alike that the lack of palpable progress in Mosul and in several Sunni-dominated provinces risks rekindling the anti-government, pro-ISIS ideology.

Soon after capturing Mosul in June 2014, ISIS made it the capital of its self-declared Islamic caliphate. Starting more than two years later and backed by U.S. air power, the rebuilt Iraqi security forces took nine months to recapture Mosul. The battle killed thousands of civilians and leveled portions of the city.

Today Mosul needs $2 billion for reconstruction, the Iraqi government estimates, including a reported $50 million project to rebuild the historic Great Mosque of al-Nuri, funded by the United Arab Emirates.

But the effort has been slowed by bureaucracy, by corruption, by political infighting after elections last year that have required many months to form a new government, and by security threats from remaining ISIS cells in Sunni areas of Iraq.

“We are two years after Mosul was liberated, and we see a steep increase in pessimism,” says Ancuta Hansen, the Iraq resident director of the National Democratic Institute (NDI), a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit that promotes democracy around the world. She cites multiple polls since 2017 that she says amount to an “alarm signal.”

Back when ISIS was forced from Mosul, 75 percent of Iraqi respondents in “liberated” Sunni-dominated regions said the country was going in the right direction, according to NDI polling. By April last year that figure had fallen to 50 percent. And by October only 24 percent said Iraq was still on the right path.

“Why is this happening? Because military gains have not been met by political reform, by economic reform, by services, by creating jobs,” says Ms. Hansen, speaking at a roundtable discussion last week at the Sulaimani Forum, an annual regional security conference convened by the American University of Iraq, Sulaimani.

“And as ISIS has been defeated, people start thinking back to those everyday issues and see that their lives, although their expectations are high, are not changing now that ISIS is not around,” she says.

Detainees in camps

At the roundtable, Ali Al-Baroodi, a photographer, activist, and former professor at the University of Mosul, points to another problem that may have even more profound and long-term consequences: the presence of at least 100,000 Iraqis affiliated with ISIS, kept at remote camps, among the 1.8 million Iraqis still displaced by the conflict with the jihadists, according to U.N. figures.

“Do you know the first caliphate ever founded in Iraq? It was in Bucca,” says Mr. Baroodi, referring to the U.S. military’s Camp Bucca detention center in southern Iraq. There, in the mid-2000s, jihadist and ex-Baathist inmates met, exchanged expertise and ideology, and formed the eventual core of ISIS.

“Now the same thing is being repeated in the isolation camps in [mostly Sunni provinces of] Saladin and Nineveh,” says Mr. Baroodi. “If you don’t want the same vacuum to happen again, if you don’t want another Yazidi genocide, if you don’t want [thousands] of people’s names put on the walls of the morgue…. You need to do more [for] the people on the ground.”

The U.N. estimates that at the peak of the jihadists’ control of one-third of Iraq, some 6 million Iraqis – 15 percent of the entire population – were displaced. So far 4.2 million have returned home, though 2.5 million still face hardship, according to Bradley Mellicker, the coordinator of the Return and Recovery Unit in northern Iraq of the U.N.’s International Organization for Migration (IOM).

Of the 1.8 million Iraqis still displaced, 600,000 remain in camps, 600,000 have a house “completely destroyed,” and most face “severe social cohesion issues,” says Mr. Mellicker, speaking at the Forum.

In addition to the problems posed by multiple armed militia groups and a patchwork of ethno-religious minorities, some 100,000 Iraqis or more “have perceived affiliations to ISIS, whether that means actual … or a more distant affiliation, perhaps the widow of a fighter or relative of a fighter,” he says. “The returns of some of these people have, up to now, not been allowed.”

Wanted: A plan from Baghdad

Crucial to improving the dynamic is leadership from Baghdad, which has still not produced a strategic plan for Mosul and other liberated areas, says Ramon Blecua, the European Union ambassador to Iraq.

Western donors “have been slow to respond,” says Mr. Blecua, speaking at the roundtable. Yet the EU has projects ready for Mosul and beyond, which include job creation, reconstruction, and political dialogue, he says, “but we need the government to take the lead with a proper action plan, with clear priorities.”

Mr. Blecua says the symbolic value of Mosul has not been highlighted enough and that on a previous visit soon after liberation he saw how the militants ruled with a surprising degree of effectiveness despite their brutality and inhumanity.

He says he was especially struck by a defense industry that ISIS created in a year and a half to manufacture weapons and explosive devices. It included a quality-control system in which every item had an ISIS stamp on it.

“In contrast, after the liberation, the question of reconstruction, and the question of how to revive Mosul as the hub of Sunni areas of Iraq, has been lacking in determination and effectiveness,” says Mr. Blecua of lackluster government efforts. “So that creates frustration.”

So far EU money has gone to the IOM and the U.N.’s stabilization fund, “but the real investment, the real international contribution, has not yet arrived,” says Mr. Blecua.

“The people of Mosul cannot wait any longer,” he says. “People need to see some real success stories on the ground and have hope that things are going to change.”

A big player in becoming a US citizen? Your ZIP code.

Over the past two years, there’s been a surge of immigrants applying for U.S. citizenship, exacerbating a backlog. One reason, according to an immigration lawyer: signs more barriers are coming.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

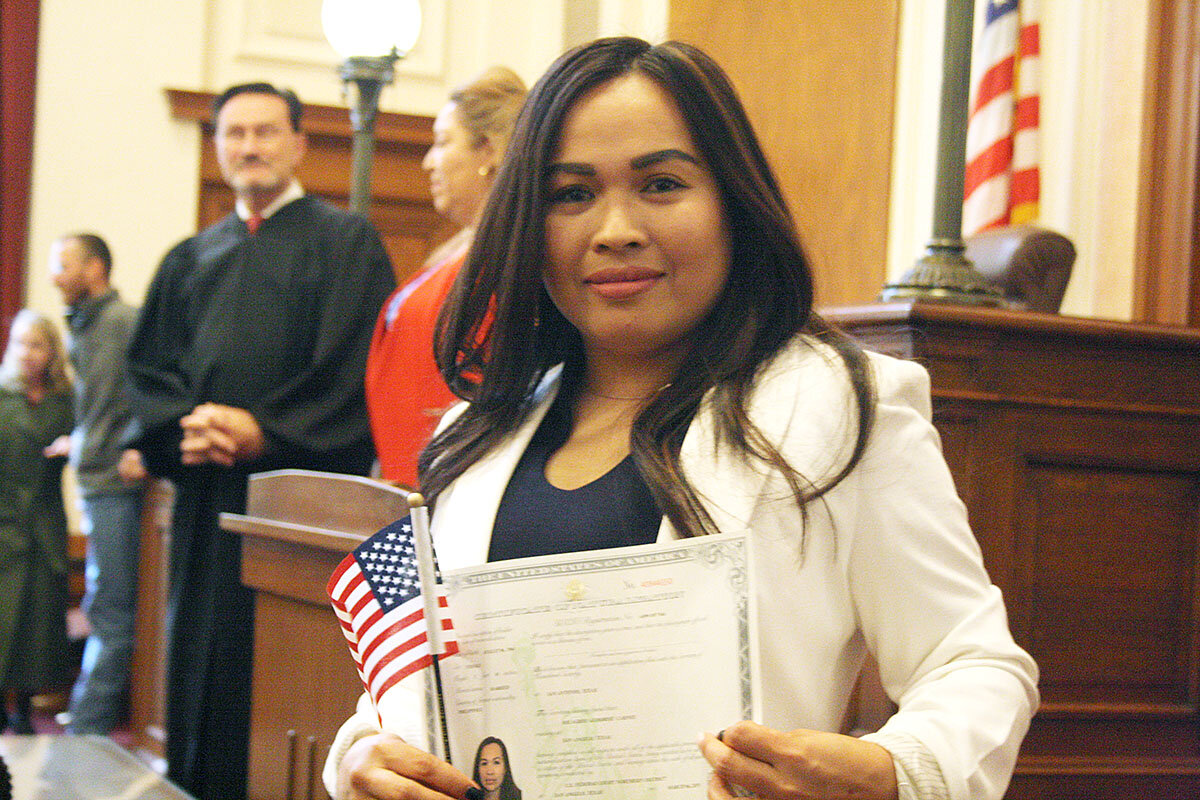

It’s a long drive from San Angelo to San Antonio – 220 miles. But for 33 newly minted American citizens, all the round trips over the past year ended in celebration last week.

“It’s a hard and long process, but it’s worth it,” says Alejandro Fraire, who has an American wife and three American children.

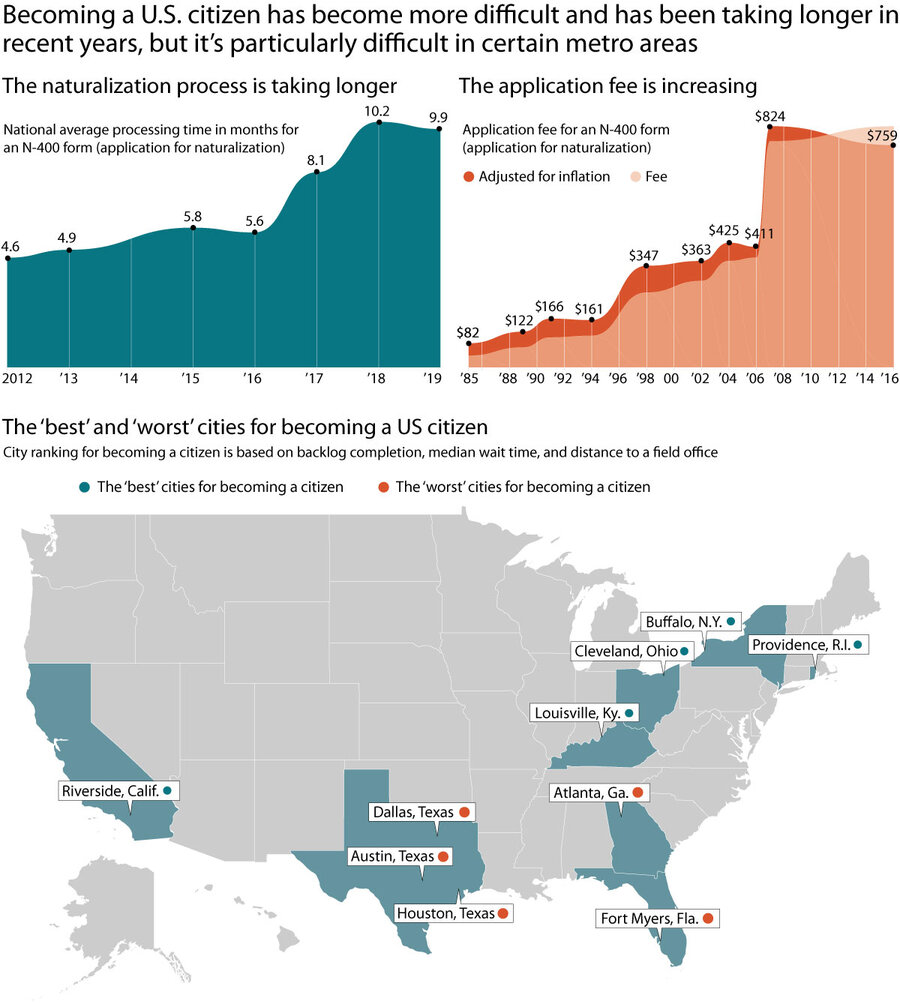

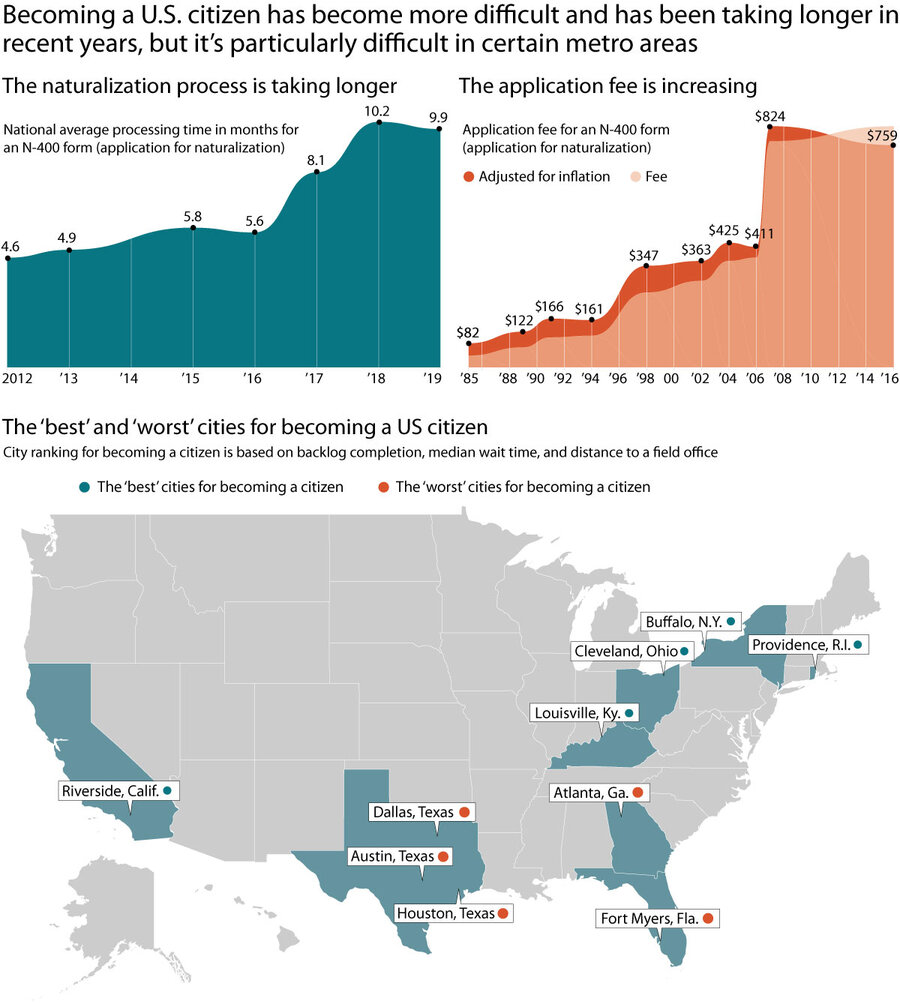

Barriers to becoming a U.S. citizen can vary significantly depending on where in the country a person lives, according to a recent report.

The report doesn’t explore why these geographic disparities may exist, and it includes some red herrings, according to experts. Austin, Texas, for example, is ranked as the hardest city in large part because applicants have to report to a USCIS office in Houston, three hours away. But the report does note broader trends in how barriers to American citizenship have gotten steeper over time.

Different field offices can also vary on discretionary aspects, such as an officer determining if someone is of “good moral character.”

“I think all the offices follow the law,” says Marisol Perez, an immigration attorney in San Antonio. “It’s case by case and officer by officer with regard to [who they say] deserves favorable discretion.”

A big player in becoming a US citizen? Your ZIP code.

This article has been updated to include a statement from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

The ties are straightened, hair combed, and jewelry gleaming here, and the line to get into the federal courthouse is spilling outside into a chilly morning.

Get here 30 minutes early, someone says; they weren’t kidding. Two U.S. airmen from nearby Goodfellow Air Force Base, here to sing patriotic songs, joke about being late for their own gig.

It’s a long drive from here to San Antonio – 220 miles, about the same as from New York to Washington. But for the 33 newly minted American citizens, all the round trips over the past year feel more than worth it.

Milagros Carnes, from the Philippines, says her American daughter worried she (Milagros) would be deported if she didn’t become a citizen. Alejandro Fraire has an American wife and three American children, and his green card was close to expiring. For both of them, naturalizing just made sense.

“It’s a hard and long process, but it’s worth it,” says Mr. Fraire, a Mexican national who has lived in the United States for two decades.

Barriers to becoming a U.S. citizen can vary significantly depending on where in the country a person lives, according to a recent report from Boundless, a Seattle-based startup that helps families navigate the immigration system.

Analyzing data from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), the report used processing times, backlog numbers, and distances to agency field offices to rank the best and worst metro areas for becoming a citizen.

The report doesn’t explore why these geographic disparities may exist, and it includes some red herrings, according to experts. Austin, Texas, for example, is ranked as the hardest city in which to become a citizen in large part because applicants have to report to a USCIS office in Houston, three hours away. But the report also notes broader trends in how barriers to American citizenship have gotten steeper over time.

The volume of citizenship applications fluctuates from year to year, but the past two years have seen a surge in applications. There hasn’t been a corresponding increase in the processing rate, experts say, exacerbating a backlog that had already doubled during the Obama administration. The success of field offices in clearing this backlog differs. In Providence, Rhode Island, 81 percent of those who applied in the past year or had applications pending have been processed, while in Miami and Dallas the number is only 30 percent, Boundless found.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

"Despite a record and unprecedented application surge workload, USCIS is completing more citizenship applications, more efficiently and effectively—outperforming itself as an agency. USCIS strives to adjudicate all applications, petitions, and requests as effectively and efficiently as possible in accordance with all applicable laws, policies, and regulations," said USCIS spokesperson Jessica Collins in a statement.

Staffing levels and office cultures and personalities might affect approval rates and backlog sizes at particular offices. Different field offices can also vary on discretionary aspects of the naturalization process, such as an officer determining if someone is of “good moral character” or if the person's ability with English is good enough. Having a criminal history, tax debts, or a spotty record of making child support payments are some indications of character issues that can be interpreted differently depending on the USCIS office or officer.

“The only time I’ve seen variation is when there is discretion on an issue of character,” says Marisol Perez, an immigration attorney in San Antonio.

“I think all the offices follow the law,” she adds. “It’s case by case and officer by officer with regard to [who they say] deserves favorable discretion.”

As part of its efforts to continue eliminating the backlog, Ms. Collins added, "USCIS is in the process of realigning our regional, district and field offices to streamline our management structures, balance resources, and improve overall mission performance and service delivery."

The realignment, effective October 2019, will realign the 88 existing field offices under 16 district offices (instead of the current 24) in order to evenly distribute workloads and provide more consistent processing times. The last such realignment occurred in 2006.

The Trump administration has increased the burden on USCIS offices. In 2017 the administration moved to expand in-person interview requirements for certain permanent residency applications and a year later expanded the interview requirement for married couples applying for a green card. While these changes didn’t affect the naturalization process directly, they have had an indirect impact by increasing the workload on USCIS officers, experts say.

“Placing a lot of emphasis on national security is applying more scrutiny to applications, is increasing their workload in looking at applications,” says Julia Gelatt, a senior policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute, “and there are proposed changes that could increase that further.”

The administration is considering other changes for this year, including a wholesale fee review and more expansive questions and travel records for citizenship applications. The administration is also reportedly considering shuttering all 21 international USCIS offices, which could slow the processing of family visa applications, with The Washington Post reporting that officials are preparing to do it.

Perhaps the biggest effect the administration has had on the naturalization process has been through its consistent anti-immigrant tone, however.

The USCIS field office in San Antonio saw a 40 percent increase in citizenship applications last year, according to Ms. Perez. The agency changed its mission statement last year – removing the words “nation of immigrants” and adding “protecting Americans, securing the homeland” – causing clients to come to her seeking naturalization.

“They fear their status is at risk because of the tone of this administration,” she says. “These are folks who should have no reason to be worried but are worried.”

“I have faith in the system, and I have faith in USCIS,” she adds. “We have good relationships with USCIS, but that’s the tone we have out there.”

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

To make Russia great again, Putin is building roads and bridges

Infrastructure is hardly the most riveting political issue. But Russian President Vladimir Putin is showing the power that building things can have on a nation’s sense of wellbeing.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

When Russian President Vladimir Putin gave his State of the Nation speech in February, the press coverage in the West focused on what he said about missiles and relations with the U.S. But that accounted for only a brief portion of his talk. The lion’s share was spent on domestic issues, key among them the rejuvenation and expansion of Russia’s infrastructure.

Those projects range from a massive road-, bridge-, and airport-building program, renewal of urban housing stock, and new gas and oil pipelines to big investments in the “Northern Passage” sea route between the Far East and Europe over the top of Russia. Experts are divided on whether the infrastructure effort will provide the long-term benefit to Russia that has been promised or whether it’s even to public benefit at all. But the Russian people seem to appreciate it.

“Such big projects, requiring so much financing, always have a variety of reasons behind them, including political, economic, and social ones,” says Olga Kryshtanovskaya, a political sociologist. “But sure, our authorities want people to have better jobs, improved surroundings, and better quality of life, if only to keep them quiet.”

To make Russia great again, Putin is building roads and bridges

Until last year, two remote villages in Russia’s poorest republic – Tuva, near the Mongolian border in distant Siberia – spent four months out of 12 cut off from direct access to civilization.

During those months, when spring thaws and the slow autumn freeze made it impossible to cross the broad Yenisei River by ferry or ice bridge, the 2,000 or so people living there sometimes went hungry. If there was a medical emergency, the only option was evacuation by helicopter.

But last year, a Ministry of Defense construction brigade built them a solid bridge, according to Russian reports, ending the community’s historic isolation and enabling residents to drive into the regional center of Kyzyl in about half an hour at any time of year. Reached by telephone, Chechek Targan, deputy chair of the formerly cutoff Kara-Khaak settlement, said that local people were over the moon about their new bridge.

“This was our dream. We used to have trouble getting food deliveries in off-season; now we eat fresh bread every day,” he said. “Life is definitely better.”

This story is one of many of its type to be found in Russian media lately. There seems little doubt that the vast infrastructure renewal program championed by Vladimir Putin is beginning to spread far beyond tourist showplaces like Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Some economists criticize the plans as throwing money – which Russia has plenty of these days – at problems without a coherent, long-term economic strategy. Others warn that it smacks of Soviet-style central planning and risks the dysfunctional outcomes that system often produced. Still others say that, as ambitious as they sound, the plans are just a drop in the bucket, given Russia’s immense expanse and crushing infrastructure needs.

But few deny that changes are actually happening and opening up new possibilities across the country, from that new bridge in Siberia to the restoration of train service in Torzhok, a neglected industrial town just a couple hundred miles from Moscow.

“There are a dozen big projects outlined by presidential decrees of May 2018” after Mr. Putin’s reelection, says Vladimir Klimanov, an economist with the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration (RANEPA). “Infrastructure is the key to Russia’s future economic development. We need to develop connecting links between regions. Without that, regional economic development is hardly possible.”

Rebuilding Russia

Those projects, outlined in a Russian government document, range from a massive road-, bridge-, and airport-building program, renewal of urban housing stock, and new gas and oil pipelines to big investments in the “Northern Passage” sea route between the Far East and Europe over the top of Russia, which climate change has made increasingly viable.

“There is money coming in from the state budget, so work will get done,” says Natalia Zubarevich, a social geographer at Moscow State University. “There is also an intention to attract investments from private business, something we should watch for. It’s possible the state will put pressure on businesses to get involved.... But the money is coming. Of course, the preference will be for big projects” with huge budgets and maximum publicity.

The use of high-profile showpiece events to drive local infrastructure development is not a new idea. Russia spent over $50 billion to stage the Sochi Olympics five years ago. Like many big Olympic spectacles, it produced a fair number of white elephants, like giant stadiums and overbuilt transport hubs, which Sochi still struggles to maintain and find uses for. But the city also received a much-needed makeover of its port, transport, sewage, and electrical infrastructure that transformed daily life for its citizens.

Last year’s FIFA World Cup, hosted by Russia, cost $14 billion but brought new hotels, transport facilities, and other improvements that continue to serve the inhabitants of the 11 Russian cities where it was held.

A lot of attention has been paid to the $3.7 billion, 12-mile Kerch Strait Bridge, a politically motivated project which opened for road traffic last year and will cement the annexed Crimean Peninsula firmly to Russia when its railroad span becomes operational later this year. It’s a prospect Mr. Putin made much of in his February State of the Nation address, saying that it will create “a powerful development driver for Crimea.” But the Kerch project is only one of more than 20 impressively long bridges that have been constructed in Russia during the Putin years.

Roads, often cited as Russia’s greatest misfortune, have seen major improvements in recent years, including a sixfold increase in expressways. The Russian government intends to invest about $100 billion to help the country’s far-flung regions modernize their road networks before Mr. Putin’s term of office ends in 2024.

‘There is no actual strategy’

As good as it may sound, many economists doubt that all these efforts will produce the national makeover that Mr. Putin has proclaimed as his program for the next five years.

Vladimir Kvint, one of Russia’s leading economic strategists, says the investments are necessary to overcome Russia’s legacy of decaying Soviet-era infrastructure. But he says they are not connected with a systematic assessment of the country’s needs and are unlikely to stimulate the economic dynamism that official statements promise.

“Of course these are useful projects, but infrastructure investment isn’t just about fixing past inadequacies. It should be about the future,” he says. “We don’t know how useful all this investment will be because there has been no systematic study. We need a strategy that identifies and prioritizes the needs of economic development, coordinates them with specific infrastructure projects, and allocates the needed resources to realize them. We have lots and lots of documents with the word ‘strategy’ in their titles, but there is no actual strategy.”

Others argue that the whole focus on infrastructure is a red herring. Daniil Grigoryev, an expert with the left-wing Institute for Globalization and Social Movements in Moscow, says Russia’s main economic problem is the Kremlin’s pursuit of neoliberal austerity measures aimed at taming inflation, reducing government debt, and balancing the state budget. That’s been successful, but it’s resulted in stagnating incomes, deteriorating social services, and a rollback of benefits the population once had, such as low retirement ages.

“The right way to drive our economy forward would be to strengthen consumer demand and improve public living standards,” Mr. Grigoryev says. “These infrastructure projects, more pipelines and transport corridors and such, are mostly intended to boost Russia’s export potential on behalf of big business. Russia is still a country that mainly exports raw materials, oil, and gas. This form of development will only reinforce those dependencies. The projects themselves are about channeling money to favored big construction firms. So it’s austerity for the majority, fresh infrastructure to promote the interests of the rich.”

Opinion polls do seem to show that infrastructure development is popular among Russians, and there is no mistaking the thumbs-up of the folks in Kara-Khaak for their new bridge.

Mr. Putin’s two decades in power have been an exercise in maintaining high public-approval ratings by delivering what Russians seem to want, from rapidly growing living standards in the last decade to strong pushback against Western sanctions and geopolitical pressure in recent years to an ambitious infrastructure program today, says Olga Kryshtanovskaya, one of Russia’s leading political sociologists.

“Such big projects, requiring so much financing, always have a variety of reasons behind them, including political, economic and social ones,” she says. “But sure, our authorities want people to have better jobs, improved surroundings, and better quality of life, if only to keep them quiet.”

Aquaculture wars: The perils and promise of Big Fish

Belfast, Maine, could be the future of food, with vibrant local farms and fisheries. But a big fish farm wants to bring industrial-scale food production to the town. Is that a step forward – or backward?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

When Lawrence Reichard first heard about plans to build a giant salmon farm in town, he was excited. “It sounded innovative,” he says. But the more he learned about Nordic Aquafarms’ plan for Belfast, Maine, “the more concerned I got.”

To proponents of aquaculture, fish farming offers real promise to feed the world’s growing population even as global fisheries decline. But to Mr. Reichard and many of his neighbors, the kind of scale being proposed – 66 million pounds of salmon annually – reeks of big agriculture and many of the environmental problems that come with it.

At the crux of the yearlong debate unfolding in Belfast is a larger question of what the future of United States food production should look like. Both sides see Belfast, a town of fewer than 7,000, as the best example of what could be.

“People say, ‘We want to keep Belfast the way it has always been. We need more small, organic businesses,’ ” says Marianne Naess, commercial director of Nordic Aquafarms. But, in her eyes, “To feed the world we have to do things differently.”

Aquaculture wars: The perils and promise of Big Fish

Elinor Daniels loves the view from her backyard. Patches of stubborn snow dot a field ringed by pine trees. But in the next few years, this quintessential Maine landscape could be replaced by a 54-acre salmon farm.

Ms. Daniels and her wife have spent the past year fighting Nordic Aquafarms, a Norwegian company that aims to site one of the world’s largest land-based salmon farms in Belfast, Maine. The couple has led dozens of neighbors in a small-town battle that could have international consequences.

In the eyes of proponents, aquaculture, as the farming of fish and other water-based species is known, has a real promise to feed the world’s growing population amid depleting fisheries. To supporters of the Nordic project, the proposed Belfast farm is a model for what high-tech, environmentally savvy aquafarming can offer. But to Ms. Daniels and many of her neighbors, the kind of scale being proposed – 66 million pounds of salmon annually – reeks of big agriculture and many of the environmental problems that come with it.

“We aren’t saying ‘no’ to aquaculture,” says Ms. Daniels, as she eats dinner with her wife, Donna Broderick, at Darby’s Restaurant in downtown Belfast. “But not at this scale.”

Belfast prides itself on its slow-food, farm-to-table culture. When Ms. Daniels looks around her town, she sees the Penobscot Bay teeming with wildlife; two year-round farmers markets; dozens of small, family-owned organic farms; and a co-op – Maine’s largest – that’s busy from dawn to dusk.

At the crux of the yearlong debate in Belfast is a larger question of what the future of United States food production should look like. Both sides see Belfast, a town of fewer than 7,000, as the best example of what could be.

“People say, ‘We want to keep Belfast the way it has always been. We need more small, organic businesses,’ ” says Marianne Naess, commercial director of Nordic Aquafarms. “To feed the world we have to do things differently.”

A ‘living laboratory’

Less than 150 years ago, the “king of fish” ran from Connecticut to northeastern Canada. In Maine’s Kennebec River alone, fishermen caught as much as 200,000 Atlantic salmon annually.

Today, fewer than 1,000 wild Atlantic salmon swim in U.S. waters, with all of them living in the Gulf of Maine. U.S. populations were declared endangered in 2000 due in part to overfishing, and populations throughout North America continue to drop. Similar stories have been playing out around the globe, as fishing pressures, pollution, and warming waters have driven fish populations down.

Despite the global decline in fisheries, demand continues to increase. On average, people today eat more than twice as much fish as they did in the 1960s. Salmon is particularly attractive because it is one of the most efficient sources of protein available to humans – a significant concern in a world where 1 in 9 people goes hungry.

“Here is an opportunity to produce high-quality protein,” says Deborah Bouchard, director of the University of Maine’s Aquaculture Research Institute in Orono. “Land-based aquaculture is a good approach to sustainable agriculture.”

Fish farming is gaining momentum globally. Between 2000 and 2016, aquaculture almost doubled its share of food fish production. By 2030, aquaculture is expected to produce 62 percent of all food fish.

International companies such as Nordic Aquafarms see opportunity in the United States, which imports virtually all of its seafood and has been slow to develop fish farming. Despite being the third largest market in the world for seafood, the U.S. is 15th in aquaculture production.

Such operations need access to cold waters, and with Washington state – the country’s other northernmost coast – passing legislation to phase out net-pen salmon farming, companies are increasingly looking to Maine. With miles of inlet and bays, Maine has the fourth largest coastline in the country and the necessary mix of freshwater and saltwater. Maine also has an employment base that has worked in fish production for generations (albeit on the high seas) and is easily accessible to the European fish market.

“This is a really exciting time.... Maine is like a living laboratory,” says Dr. Bouchard. “We see the expansion of aquaculture in tons of different directions.”

Mid-coast Maine in particular is becoming the U.S. epicenter for aquaculture, with two of the country’s three largest land-based salmon farms being developed less than 25 miles apart.

Maine-based startup Whole Oceans is building an slightly smaller farm in Bucksport. As a former paper mill town, residents have largely welcomed the industry. Combined, the Bucksport and Belfast farms aim to produce almost 20 percent of the country’s salmon.

Belfast, which used to be known as the chicken capital of Maine, has been on an economic odyssey of its own, ever since the poultry plants left in the 1980s. Nordic says the $500 million project will eventually bring about 100 jobs of various skill levels to Belfast, while supplying 7 percent of the U.S. salmon demand. But locals say the memory of the town’s agricultural past – when chicken feathers flew in the streets and chicken guts floated in the bay – has left them wary of Big Ag.

“It was a mess of a town,” says Ms. Daniels. “And now we’ve been seeing aquaculture as a magic bullet.”

Trade-offs

When Lawrence Reichard first heard about the salmon farm, he was excited.

“The idea of having Norwegians coming and floating around town, it sounded kind of fun. It sounded innovative,” says Mr. Reichard, a freelance journalist who lives in Belfast.

“I went to the first public information meeting. There were things at that meeting that didn't really add up so I started looking into it,” says Mr. Reichard. “And the more I looked into it, the more concerned I got.”

At that first public meeting in February 2018, residents quickly filled the 200 available seats and crowded the back of the room. The three subsequent informational meetings have drawn similar, if not bigger, crowds.

One of the most controversial topics at these meetings is wastewater. Opponents are concerned about the 7.7 million gallons of discharge that would flow into the Penobscot Bay daily, increasing outflows by 90 percent. Nordic has yet to receive a discharge permit from the state, an outcome opponents like Ms. Daniels are keen to prevent.

Proponents argue that the potential environmental effects of aquaculture are relatively minor when compared with those of other industries. A paper mill, for instance, would emit at least 2.5 times as much wastewater. Nordic says its discharge will undergo innovative treatment removing 99 and 85 percent of harmful, algae bloom-causing phosphorous and nitrogen, respectively.

But opponents counter that, even after filtration, discharge could significantly alter the nitrogen levels. One estimate found that the aquafarm would deposit water that is 48 to 135 times higher in nitrogen than the bay’s current level.

There’s also concern about how much water the farm will use. A recirculating aquaculture system, like the one Nordic plans to build in Belfast, requires a lot of clean water. After all, it allows fish to grow on land. Nordic plans to draw more than 400 million gallons of clean freshwater from underground aquifers per year to circulate through the farm’s 18 tanks (each one three times as large as an Olympic swimming pool).

“We don’t know how aquifers and watersheds will perform in the future with climate change,” says Mr. Reichard. “To use this much water on this scale, we’re really rolling the dice on Belfast’s water supply.”

Some locals support small-scale aquaculture, arguing that it has its own place in Belfast’s food economy.

But a recirculating system requires a big investment, says Ms. Naess, sitting at a long table in Nordic’s new Belfast office. To make it profitable, it has to be big.

“All aquaculture has its challenges,” says Ms. Naess, “but this one is the easiest to scale up around the world.”

Local concerns

On a January Sunday, at least two dozen Mainers in snow boots sit in a circle on fold-out chairs at the Belfast Public Library.

Attendees hail from Belfast and at least four other neighboring towns. Three people are new. State Rep. Janice Dodge holds up poster boards, teaching the attendees how to structure letters and emails to local legislators. Many people around the circle take vigorous notes.

If any good has come from the feud in Belfast, it would be a newfound interest in local government. Three Nordic opposers ran for city council seats in September, including Ms. Daniels, challenging seats that had sat unopposed for years. They have helped draft three bills for Maine’s House of Representatives to preserve the Penobscot Bay and change the permitting process for land-based aquaculture.

The opposition in Belfast has been bigger than the Nordic team expected, and the company has had to push back its original plans to break ground this spring. The company is hoping to secure the permits and applications to break ground by the end of the summer. Without any further delays, the plant expects to see its first fish leave the farm in 2022. But a lawsuit filed in July by Ms. Daniels and Ms. Broderick could further disrupt those plans. The couple is arguing that the city failed to follow its own zoning procedures when reclassifying the field behind their house as industrial.

“When you have opposers, they are loud,” says Nordic Aquafarms president Erik Heim, who is married to Ms. Naess. “There will be some people who will never agree, and we have to accept that.”

But the dozens of Mainers gathered in the library don’t show any signs of backing down. A man with a long gray ponytail, Ron Huber, tells the group he feels like the little people in the novel “Gulliver’s Travels” by Jonathan Swift, who succeed in tying down a “giant” by covering his body with many small threads.

“You think it would be impossible,” says Mr. Huber. “But they just keep throwing those small ropes.”

[Editor's note: An earlier version of this report mischaracterized the size of the aquafarm being built in Bucksport. It is slightly smaller than the proposed project in Belfast.]

Flying first class? It’s good to be a falcon in Abu Dhabi.

In many cultures, traditions recall a triumph over adversity. So for our last story, we take you to the Persian Gulf, where the love of falconry is rooted in an identity born of the desert and the Bedouin family tent.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Taylor Luck Correspondent

They were the secret weapons of the Bedouin, the key to a good winter’s hunt. Falcons – trained to bring down rabbits, game birds, and even small gazelles – were long part of desert life. Family members would carry the falcons on a gloved arm for weeks to get the birds used to them.

Today, Emiratis tend to falcons for sport. The United Arab Emirates sponsors festivals and high-stakes races. Hundreds of Abu Dhabi residents rise early during the winter to drive out to the desert and train the birds. But the Emiratis do not forget the debt they owe them. The falcon is everywhere here: on government seals, bank notes, military uniforms. In the land of sheikhs and princes, the falcon is king. The exalted birds are even issued passports.

But there is perhaps no greater testament to Emiratis’ devotion than the Abu Dhabi Falcon Hospital, where owners sit in the waiting room like expectant fathers while their hooded falcons await appointments. “We are not taking care of birds,” says Dr. Margit Muller, the hospital’s director. “We are taking care of their children.”

Flying first class? It’s good to be a falcon in Abu Dhabi.

Long before natural gas and oil discoveries in the 1950s transformed the United Arab Emirates into an economic powerhouse of skyscrapers and tech firms, it was an eat-what-you-catch way of life for the region’s nomadic Bedouin inhabitants.

But the Bedouin had a secret weapon, equipped with basic desert tools and instincts, that could make or break a winter’s hunt: the falcon.

While the mostly arid desert had limited grazing lands, it did lie under the flight path of migrating birds moving south from Europe to Africa for the winter. The Bedouin would trap falcons stopping to rest at desert oases and then, after weeks of training, would deploy them to catch and kill rabbits, game birds, and even small gazelles.

Falconry became an integral part of the Bedouin’s way of life. Yet something else happened when the Emiratis’ ancestors trained their wild falcons.

Working in shifts, Bedouin family members would carry the falcon on a gloved arm around the clock for up to two weeks to get the bird used to their voice, commands, and touch. Sitting in their tents and even sharing their food, the falcons would soon be seen as part of the family.

“Because in the UAE falconry was [originally] never a sport, but an important tool for survival, the falcon was quickly integrated into the Bedouin family like a child,” says Dr. Margit Muller, an author and director of the Abu Dhabi Falcon Hospital.

Preserving the tradition

After centuries of people relying on these birds of prey for survival, the UAE is now one of the wealthiest countries in the world. The falcon is the UAE’s national symbol, and an estimated 10,000 Emiratis tend to falcons for sport and pedigree breeding.

To keep the falconry tradition alive, the UAE’s rulers sponsor several festivals and races across the Emirates during the winter, with prizes in the millions of dollars.

In hopes of snagging a prize or simply honing their falcons’ skills, hundreds of Abu Dhabi residents rise before dawn each day during the winter months, drive out to the desert, and train their pedigree falcons with decoys before the morning sun begins to blaze.

The royal-linked Mohamed bin Zayed Falconry and Desert Physiognomy School, meanwhile, teaches young Emirati students across the country the tradition of falconry to pass on their ancestral craft to the next generation.

The UAE is home to falconry clubs, falcon breeding and reintroduction programs, falcon boarding schools, and several associations devoted to promoting the care of falcons.

The Sheikh Zayed Al Nahyan Release Program has reintroduced more than 1,800 endangered peregrine and saker falcons into the wild in Pakistan and Uzbekistan.

The falcon hospital

The Emiratis do not forget the debt they owe to their adopted “children,” but there is perhaps no greater testament to Emiratis’ care for falcons than the Abu Dhabi Falcon Hospital.

The hospital, a sprawling center on the outskirts of Abu Dhabi with operating theaters, X-ray machines, and an in-house lab, is the largest falcon hospital in the world and one of the largest avian hospitals anywhere.

Anxious owners sit on plush, leather couches in the air-conditioned waiting room, sipping Arabic coffee and glancing at the clock like expectant fathers, while a half-dozen hooded falcons stand on a row of perches placed in the middle, waiting for their appointments.

Falcon owners from across the Gulf come to the hospital, which is open 24 hours and has a team of on-call staff and surgeons.

“We are not taking care of birds. We are taking care of their children, as this is how they see them,” Dr. Muller says.

The patients

Some emergency cases are victims of “crashes,” or mid-air collisions. For falcons, who fly at speeds of up to 300 km per hour, this is no laughing matter. Other common conditions include lung infections or illnesses picked up from diseased prey.

However, over 60 percent of the patients at the hospital are here for their regular, biannual checkup. But these checkups are not just parental handwringing. As birds of prey, falcons notoriously hide any sign of illness or injury, lest competing birds or predators see that they are lame and take them down. Often when owners finally notice the signs of an illness – a loss of appetite, sluggishness – the problem has been present for weeks, and it may already be too late.

At the hospital one day in February, veterinarians perform one of their more routine operations, a “feather transplant.”

A tiny gas mask is carefully attached to the falcon’s beak. After several seconds of anesthesia, the vet prepares a stent and inserts a spare feather in the wing, restoring its balance.

In a week’s time, the falcon will be back to flying as normal.

Traveling in style

Amid their enthusiasm, Emirati falcon owners faced a dilemma. With the largely arid Emirates becoming increasingly developed, overhunting depleted local wildlife. The UAE government was forced to ban falcon hunting in the country in 1999.

Emiratis began taking their falcons to other countries – Jordan, Pakistan, Morocco, and even Iran – to hone their natural instincts in the wild and feel the unfettered wind beneath their wings.

Yet with some falcons classified as endangered or protected species, Emiratis would constantly face difficulties at customs when entering and leaving with their feathered family member.

In 2012, the UAE found a solution: falcon passports.

The UAE is now the only country in the world to issue full and legal passports for falcons indicating their gender, size, name, ID bracelet, and color. The Emirates have issued some 30,000 falcon passports.

Two of the UAE’s national carriers, Etihad and Emirates, allow passengers to take their falcons on as their carry-on luggage – if they are small enough to perch on their arm – or to fly as passengers.

It is common on Emirati airlines to see a falcon sitting on a chair in economy, business, and even first class on international flights – hooded so as to be put on manual ‘sleep mode’ throughout the flight.

Elsewhere, throughout the UAE, the falcon is everywhere: on government seals, the 100-dirham note, the uniform of the Emirati armed forces, and on the gates and doors of royal palaces and private homes.

More than family, here in the land of sheikhs and princes, the falcon is king.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

How to de-corrupt college admissions

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Federal charges this week related to fraud and bribery in the admissions process of several elite universities point a finger at two parties: wealthy parents who cheated to get their children in, and school workers who assisted them, especially athletic coaches. Yet while the institutions seem blameless, they do bear ultimate responsibility for the incentives that drove the scandal – and for the solutions to prevent a similar one.

Few universities today see themselves as a vehicle for learning virtues to live a full life. Most now aim to ensure a lucrative career for graduates and to signal social worth for them. Education has become a consumer commodity and less a guide to civic values and moral progress. The mere acceptance into a top-flight school has become an end in itself – followed by a diploma that bestows status.

The answer to the illegal or unethical manipulation of admissions is to make sure schools are a community of learners – including teachers – dedicated to character formation, not just intellectual achievements. The message must go out to all staff in higher education that values such as honesty and trust are part of the entire school experience.

How to de-corrupt college admissions

Schools of higher education in the United States are no doubt in a reflective mood about the meaning of institutional integrity. On Monday, the FBI announced 50 indictments related to fraud and bribery in the admissions process of several elite universities. More indictments are expected.

The federal charges point a finger at both wealthy parents who cheated to get their children into prestigious schools as well as school workers who assisted them, especially athletic coaches. Yet while the institutions seem blameless, they do bear ultimate responsibility for the incentives that drove the scandal – and the solutions to prevent a similar one.

Few universities today see themselves as a vehicle for learning virtues to live a full life. Most now aim to ensure a lucrative career for graduates and to signal social worth for them. Education has become more a consumer commodity and less a guide to civic values and moral progress. The mere acceptance into a top-flight school has become an end in itself followed by receiving a diploma that bestows status.

In 1966, The American Freshman Survey found 86 percent of entering students saw higher education a way to discover a meaningful approach to life. Less than half wanted to be “very well off financially.” By 2015, the survey found 82 percent preferred the aim of making money while only 45 percent sought meaning. No wonder so many parents try to rig the admissions process to give a child an unfair leg-up.

The competitive incentives to cheat on applications, testing, and other parts of the process are huge. In addition, many schools give preferences for admission not based on merit. In a 2015 survey by Kaplan Test Prep, a quarter of admission officers said they felt pressure from their schools to accept an applicant who didn’t meet the requirements.

The answer to the illegal or unethical manipulation of admissions is to make sure schools are a community of learners – including teachers – dedicated to character formation, not just intellectual achievements. The message must go out to all staff in higher education that values such as honesty and trust are part of the entire school experience. They are a public good that can be nurtured in the thinking of young people. Some colleges, such as Tulane University in New Orleans, promote the “core values” expected in campus life, including in the admissions process.

When schools provide constant models for integrity, they can inspire staff, students, and parents to see education as developing qualities of thought. The incentives to cut corners should go away.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The Love that lifts us from despair

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Sandy Sandberg

Even when it seems there’s no end to what’s wrong in the world, God’s limitless love is here, inspiring hope, wisdom, and strength to overcome the bad and to be and do good.

The Love that lifts us from despair

For a lot of us, life is pretty good. We’re healthy, engaged in fruitful work, enjoying good relationships, and looking expectantly toward the next adventure. But for many, life is a lot more challenging. Man-made tragedies, along with hurricanes and other weather disasters that have left thousands of people homeless, lend themselves to feelings of despair and hopelessness.

But even when it seems there’s no end to our troubles in sight, there is a way out of this morass of helplessness. It’s by turning our thoughts toward the one source of help and hope that is always available: God, divine Love. The Bible puts it beautifully: “The Lord upholdeth all that fall, and raiseth up all those that be bowed down” (Psalms 145:14).

Christian Science teaches that God made us for no other purpose than to be the very expression, or spiritual reflection, of His being. The qualities that constitute God are ours right now, by virtue of our being His reflection. For instance, the goodness, freedom, strength, and wisdom that constitute Love are freely and abundantly ours to express. They are infinite – and they never run out. In “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, writes, “God expresses in man the infinite idea forever developing itself, broadening and rising higher and higher from a boundless basis” (p. 258).

Even in the most desperate situations, nothing can ever change this wonderful fact. God’s children are not at the beck and call of evil forces lying in wait to destroy us. We are living, moving, and forever dwelling in divine Love. This spiritual reality motivates and empowers us to be and do good. In fact, because God is supreme, there is no other power anywhere that can disrupt this divine activity or prevent us from fulfilling our God-given purpose: to impart and express the very nature of limitless Love.

This is what brings relief and healing. This is the eternity for you and me and everyone. And right now, moment by moment, we can let Love lift us from despair to hope, and from fear to courage.

Adapted from the Nov. 8, 2018, Christian Science Daily Lift podcast.

A message of love

Ready to fly the colors

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when staff writer Stacy Teicher Khadaroo looks at the move to bring charges against school administrators in Parkland, Florida. Educators need to be held accountable for enforcing safety rules, many say. But is there an ethical dilemma in punishing those who also show great bravery and sacrifice during school shootings?