- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Resiliency rising

Where some see only rising waters, others see rising resilience.

From Mozambique to the U.S. Midwest, storms have wreaked havoc and hardship. Cyclone Idai tore across southern Africa leaving an estimated 1,000 dead. In Nebraska, record flooding has forced evacuations in dozens of towns. Some 200 miles of levees have been breached in four states, and 14 bridges have been washed out.

But the devastation is being met by a surplus of goodwill. “We’ve had more volunteers than what we need, and I mean people are willing to do anything to help out,” said Craig Risor, a coordinator at one of four shelters in Norfolk, Nebraska.

Across the Midwest, generosity and grit are native qualities. Most people don’t have to ponder whether or not to open their wallets, their homes, or their hearts.

Nebraska’s Fremont Municipal Airport is “a scene of human generosity,” wrote one columnist. As donations of diapers, toiletries, and blankets arrived on planes from Iowa, flights left full of evacuees. The president of Silverhawk Aviation said his firm provided about 20 free flights for about 150 people.

Three people have reportedly died in the flooding, including James Wilke. The Nebraska farmer jumped on his John Deere to assist a trapped motorist. As Wilke drove over a bridge, it collapsed into a swollen creek.

“He was always the first to go help somebody,” his cousin told the Omaha-World Herald. “He was a person who wouldn’t just talk about making things better. He would do it.”

Now to our five selected stories, including how some countries are countering autocracy, Venezuela’s road to stability, and the best biographies of March.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Global report

After Christchurch, Muslims ask: Are we safe in the West?

Our reporters asked how the New Zealand mosque shooting is perceived by other Muslims. The global responses range from fear to hope in Western values.

-

By Peter Ford Staff writer

-

Sara Miller Llana Staff writer

-

Ann Scott Tyson Staff writer

For Amira Elghawaby, it was the carpet. Ms. Elghawaby lives in Ottawa. But when she watched video of Friday’s Christchurch mosque massacre, she was struck by the green prayer carpet on which the victims lay. It was just like the carpets at so many of the mosques where she has prayed.

The New Zealand attack, which left 50 worshipers dead, has shaken Muslim communities across the globe. It has also steeled them against the possibility of more such atrocities. As anti-Muslim sentiment rises, a similar assault could happen anywhere, worries Raja Iqbal, CEO of an artificial intelligence start-up, leaving his mosque in Redmond, Washington, last Friday. “There’s a growing nationalism around the world, a growing xenophobia,” he says.

And it is that mood, felt globally, that set the scene for the savagery in Christchurch, some observers say. Hostile rhetoric is becoming more commonplace, and so too are hate crimes against Muslims. Especially worrying, says Fiyaz Mughal, a monitor of anti-Muslim activity in Britain, “most incidents used to be online; now they are predominantly street events. Things are flipping into the real world quite substantively.”

After Christchurch, Muslims ask: Are we safe in the West?

For Amira Elghawaby, it was the carpet.

Ms. Elghawaby lives in Ottawa. But when she watched video of Friday’s Christchurch mosque massacre, she was struck by the green prayer carpet on which the victims lay, which was just like the carpets at so many of the mosques where she has prayed.

“It just felt so close,” she says.

The New Zealand attack, which left 50 worshipers dead, has shaken Muslim communities across the globe. It has also steeled them against the possibility of more such atrocities.

As anti-Muslim sentiment rises, a similar assault could happen anywhere, worries Raja Iqbal, CEO of an artificial intelligence start-up, leaving his mosque in Redmond, Washington, last Friday. “I don’t think it’s purely Islamophobia,” he says. “There’s a growing nationalism around the world, a growing xenophobia.”

And it is that mood, felt in the United States and Canada as well as in Europe and further afield, that set the scene for the savagery of last Friday’s events in Christchurch, some observers say. Hostile rhetoric – voiced and fed by politicians, the media, and social networks – is becoming more commonplace, and so too are hate crimes against Muslims.

“The ground for violent actions is laid by violent discourse,” says Rachid Benzine, a noted French-Moroccan scholar of Islam. “Words can kill.”

Especially worrying, says Fiyaz Mughal, an award-winning monitor of anti-Muslim activity in Britain, “most incidents used to be online; now they are predominantly street events. Things are flipping into the real world quite substantively.”

‘Always in the back of my mind’

The immediate priority at the Redmond mosque on Friday was physical security. Police stepped up their presence, and “we are considering any and all security measures,” says Amelia Neighbors, a member of the mosque’s board.

Worshipers also appeared to appreciate signs of support from a small group of well-wishers from other faiths who gathered in front of the mosque. But they are aware of a hardening mood in the United States.

Hate crimes have been rising year after year, according to FBI figures, and attacks on Muslims and their places of prayer hit an all-time high in 2016 before falling back slightly in 2017, the last year for which statistics are available.

North of the border, Canada has stood out for its embrace of multiculturalism and the welcome it has offered to Syrian refugees, yet a similar trend has emerged. Hate crimes jumped by 47 percent in 2017 from the year before, according to government figures, and crimes targeting Muslims rose by 151 percent. Incidents against Muslims in Quebec peaked in March 2017, the month after a gunman killed six worshipers at the Islamic Cultural Center in Quebec City.

Ms. Elghawaby, whose Egyptian parents brought her to Canada when she was a baby, says she is not frightened (though someone once drove a pickup truck straight at her before swerving away as passengers yelled at her to take her headscarf off). “But it’s always in the back of my mind.”

At Toronto’s Jami mosque, the oldest in the city, administrator Amjed Syed says he will not be cowed by the Christchurch attack. “We are not paranoid,” he says. “Our doors are open all the time.”

Continental attitudes

In the heavily Muslim suburb of Pantin, north of Paris, mosque president M’hammed Henniche is more circumspect. Though he turned down a government offer of an armed police guard, he is keeping his doors locked between prayers for safety’s sake.

Violent attacks on mosques are rare in France, but the atmosphere often feels hostile to Muslims, Mr. Henniche says. “We are more visible nowadays, less ashamed of our religion than our parents were, and that makes a lot of ordinary French people afraid that their country is being taken over,” he explains.

“In general society there is a fear of Islam,” adds Mr. Benzine. “Sometimes it looks like mass hysteria,” he says, pointing to the media and political firestorm that erupted recently when a sportswear chain introduced a moisture-wicking Islamic headscarf for joggers. The retailer was forced to withdraw the item in the face of charges it was contributing to the isolation of Muslim women.

Prevalent attitudes in France toward Muslims are also manifest in hiring practices. A study last year found that a religious Muslim man had four times fewer chances of being called to a job interview than a religious Christian with exactly the same CV.

Such discrimination “frustrates Muslims and makes them turn inward toward their own community,” says Mr. Henniche. “And that spurs more French racism against them.”

Politicians can make things worse. Then-Interior Minister Gérard Collomb said last year he found it “shocking” that the head of a student union at the Sorbonne University – a Muslim convert – should wear a headscarf. He said it was “a sign … she is different from French society.”

Nor do Muslims feel very welcome in courtrooms in Bavaria, in southern Germany. The state’s constitutional court last week upheld a ban on judges and prosecutors wearing headscarves on the grounds that they should be neutral in matters of religion. A Christian cross, meanwhile, hangs in every Bavarian courtroom.

German Interior Minister Horst Seehofer, a senior member of the ruling Christian Social Union party, sparked controversy last year when he declared that “Islam is not part of Germany.”

“When politicians say all day long that Muslims are different, that they don’t belong, is it surprising when you see an increase in Islamophobic violence?” wonders Nadim Houry, head of the terrorism program at Human Rights Watch. “It definitely creates an enabling environment.”

The first nine months of 2017 saw 97 attacks on mosques in Germany, a 25 percent jump from the same period a year earlier, according to the Turkish Islamic Union for Religious Affairs, which runs most of the mosques in the country.

‘The perfect storm’

In Britain, the number of anti-Muslim incidents continues to rise, hitting new records in 2017 according to TellMAMA, an organization that measures anti-Muslim attacks. There has been a recent surge in the number of reported incidents and in their level of aggression, says Mr. Mughal, TellMAMA’s founder.

Mr. Mughal blames social media companies, especially Twitter, for being slow to take down posts by right-wing extremists and to block the accounts on which they appear. He also points a finger at inflammatory newspaper headlines.

A 2012 study of the U.K. press over three months by scholars at Leeds University found that 70 percent of stories about Muslims were hostile and that 80 percent of them included no Muslim sources. “Press coverage representing Muslims is largely hostile and … Muslim voices remain marginal,” the researchers found.

Other factors behind the rise in violent Islamophobia, Mr. Mughal suggests, include Islamist terror attacks, the economic downturn and the financial strains it has imposed, routine discrimination against Muslims, and the far right’s effective use of the internet.

“A combination of all these elements has created the perfect storm,” Mr. Mughal says. “It creates an environment where hate is normalized, an environment of dehumanization without any sense of empathy or care” in which outrages such as the Christchurch massacre become possible.

“Sadly, I think it is only a matter of time before there is another one like that,” Mr. Mughal says.

The view from the Middle East

What impact is all this having on the overwhelmingly Muslim Middle East, where millions of families have relatives living in Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand?

Western foreign policies and the wars they have fostered mean that the United States and Europe are widely unpopular in the Middle East. But the Christchurch massacre has brought to the surface uglier allegations.

“The U.S. bans Muslims. Muslims are killed in the mosque as easily as they are killed in wars here,” says Abu Mohammed, a young Jordanian engineer. “They don’t just want our economic resources or our lands; they truly hate Islam and Muslims.”

The attack has also stirred fears about living in the West. “It is not safe being an Arab or a Muslim in the West,” said Awra Ali, a Jordanian nurse whose sister lives in Michigan. “No matter if they talk about human rights or inclusivity, you will always be different; you will always be the other; you will always be a target.”

Some would-be emigrants even say they are rethinking their plans to escape the region’s deadening unemployment rates. “I have been dreaming of the West, thinking of it as heaven on Earth, the answer to all my problems,” says Mohammed Tamimi, an Amman taxi driver who has been applying for scholarships in Australia and Canada.

“But it looks like the Arab world is much better for me. At least here I can pray without fear.”

But very few people blame any particular religion for the inflammatory rhetoric and Islamophobic attacks in Western countries that they hear about.

“We can’t let one isolated incident by one sick person color our perception of an entire people, country, or religion,” insisted Ahmed Awreikat, a cousin of one of the men who died in Christchurch, at the victim’s funeral. “In the West, they have democratic institutions, transparency, and inalienable rights,” he pointed out. “That should be enough to protect Arabs and Muslims.”

Across the world in Ottawa, Amira Elghawaby is also putting her trust in such “Western values” and hoping that the authorities will uphold them.

“I know that Canadians are by and large extremely welcoming and supportive, and … I do feel that I belong here,” she says. “But at the same time I’m really looking to all levels of government, everyone, to really do more to try to root out this type of hatred.”

Taylor Luck in Amman, Jordan, and Clifford Coonan in Berlin contributed reporting to this article.

Trapped in tariffs, a lobster-linked industry seeks a way out

Rising trade barriers since 2017 haven't shown much effect on the overall U.S. economy. But tariffs do have consequences. We dived into the chilly trade waters of the makers of lobster traps and crab pots to learn more.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

Clarence Leong Staff

Perhaps more than any other U.S. sector, the lobster industry has been buffeted by tariffs. Over the past two years, lobster dealers have been undercut: first when the European Union dropped tariffs on Canadian live lobsters but not on U.S. ones, and then last June when dealers got hit by Chinese duties, part of Beijing’s retaliation for Trump administration tariffs against China.

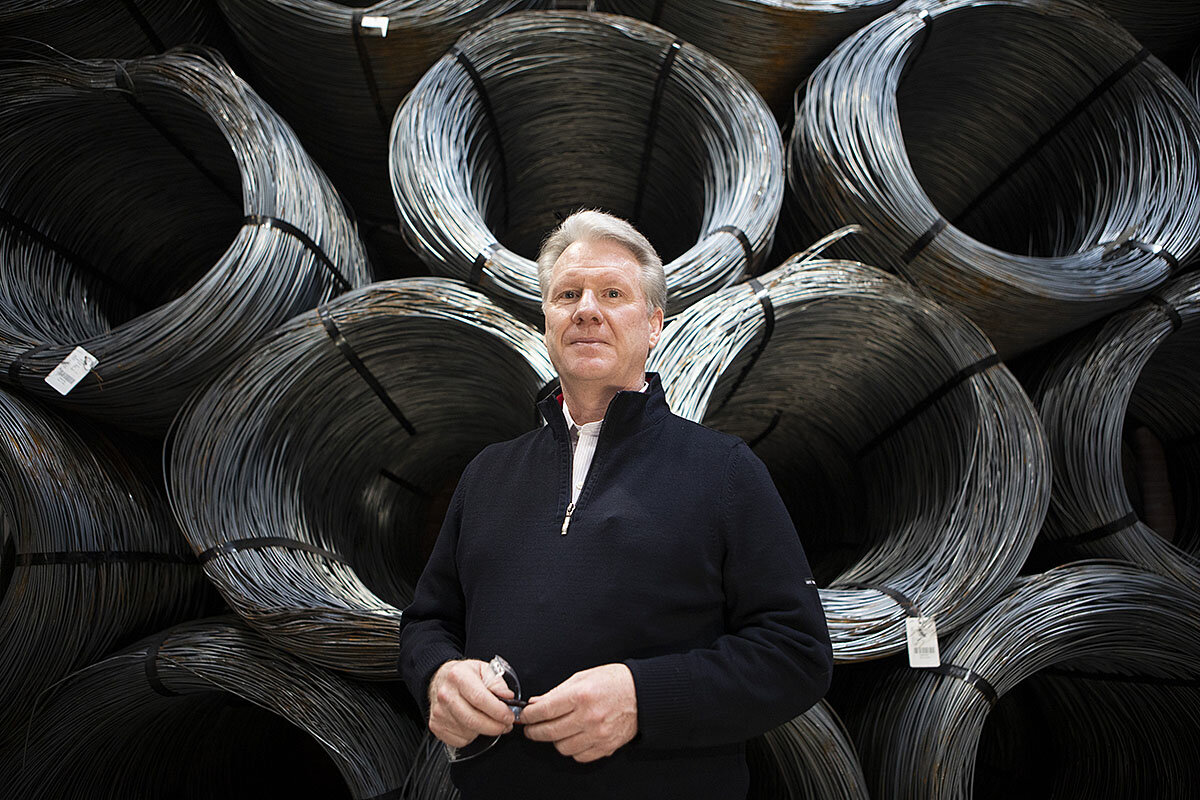

In the meantime, Trump tariffs on steel imports have squeezed Riverdale Mills, the nation’s biggest producer of lobster traps. James Knott, Riverdale’s CEO, has reduced his workforce, raised some prices, and seen longtime clients hedge their bets, splitting their orders between his company and EU competitors.

So what happens if tariffs, instead of being a short-lived negotiating tool, become a permanent part of a U.S.-China trade agreement, ready to be reinvoked if the U.S. believes China is misbehaving? As the lobster industry shows, they’ll create new winners and losers based on nationality rather than competitiveness. Says Mr. Knott: “There’s a lot of uncertainty.”

Trapped in tariffs, a lobster-linked industry seeks a way out

A gritty gray mist rises from the ground floor of Riverdale Mills interrupted by explosions of color: yellow, reds, and blues – as if someone had tried to merge this Northbridge, Massachusetts, steel-mesh maker with pieces of a Crayola factory.

This is America’s biggest producer of lobster traps and crab pots, with their colorful PVC coatings to protect them from the seawater, but CEO James Knott Jr. has seen his profit margins and his employee base dwindle over the past nine months because of U.S. steel tariffs.

“My main competitors are out of China and the EU and they don’t have any tariffs,” he says. “We get out of line with the world market and we are in trouble.”

Tariffs are key to President Donald Trump’s trade strategy. The administration has used them to help out domestic producers of everything from steel to washing machines and solar panels. And it has used tariffs on all manner of Chinese goods to prod Beijing to the negotiation table. But it’s now becoming clear that tariffs represent more than a negotiating tool for the administration. Reports suggest the U.S. wants to use them as a permanent enforcement mechanism in any China trade deal, under which Washington could reimpose them if it judged that Beijing was not living up to its end of the bargain and Beijing would not be able to retaliate.

The lobster industry, which has experienced a rare triple whammy of tariff hits, is a peek at how this new world might work.

For all the hoopla by Trump trade supporters and detractors, the impact of tariffs on a large and domestically based economy like the United States is more whimper than bang. Even as the effect is very sizable for some industries and firms, it’s not very visible as a factor in the overall economy.

“It’s not large,” says Patrick Kennedy, co-author of a March study on the effects of tariffs on the U.S. economy.

The benefits are small. For example, the U.S. steel industry has begun to reopen plants and add workers since President Trump announced a heavy 25 percent tariff on imported steel a year ago and extended those tariffs to Canada, Mexico, and the European Union (EU) in June. But the extra 7,000 jobs – a little less than 2 percent of the industry’s workforce – hardly represent a renaissance.

So are the costs, by some measures. Mr. Kennedy and his co-authors of the National Bureau of Economic Research study found that the net impact of the Trump tariffs – the better sales and profits for domestic producers and increased government revenue minus the higher costs for steel users and other consumers – represents a very small drag on the economy: $7.8 billion. That is a minuscule 0.04 percent of the U.S. economy as measured by gross domestic product. A February survey of business economists found that if tariffs persist in 2019, more than half the economists believed the drag would be larger, lopping a quarter or half a percentage point from GDP growth.

What’s changed are the winners and losers, which are based increasingly on nationality rather than efficiency or business savvy.

As a steel buyer, Mr. Knott is clearly on the wrong side of the divide. Riverdale produces a wide range of products from birdcages to farm barriers to high-security fencing. When the president extended his steel tariffs to include Canada (as well as Mexico and the EU) in June, Mr. Knott saw steel prices rise across the board. His shipping costs soared, too, since steel mills in Canada are closer to him than ones in Texas or North Carolina.

Since then, prices have moderated, but he remains cautious. He’s experimented with raising prices in selective markets, and through attrition has reduced his workforce from 200 to 150. Since the tariffs, he’s also seen longtime clients hedge their bets, splitting their orders between his company and EU competitors. “There’s a lot of uncertainty,” he says.

So what happens if the threat of tariffs becomes a permanent part of a U.S.-China trade agreement? Will that cause ongoing uncertainty among Chinese buyers of U.S. products?

As it happens, the other end of the lobster business has also been hit by two waves of tariffs. The U.S. industry has been on a tear in the past decade, with both the size and value of the catch nearly doubling since 2008. But in the fall of 2017, Canada and the EU provisionally implemented the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), which immediately eliminated the EU’s 8 percent tariff on Canadian live lobster, while the tariff remains for U.S. lobster.

To compensate, the Americans, who so far have gotten nowhere with the EU, worked hard to expand markets in Singapore, South Korea, and especially China. Exports to China more than doubled in the first half of 2018 compared with the same period a year earlier. Then on June 15, the industry learned that in response to Mr. Trump’s tariffs on China, China would retaliate with a 25 percent tariff on various seafood, including lobster.

“I’ve had one company say that they lost – I mean overnight lost – like 100 percent of their exports to China,” says Annie Tselikis, executive director of the Maine Lobster Dealers’ Association. “Others lost 80 to 90 percent. It’s just it’s been a really, really challenging time for these businesses.”

And outside of working to develop new markets, there’s little the suppliers can do. “Being caught in the crosshairs of a dispute around intellectual property when you’re a food business ... it seems nonsensical,” says Ms. Tselikis.

Ironically, the tariffs have not hurt U.S. lobstermen so far. They’re struggling with environmental challenges this year, but demand is so strong that they should be able to sell all that they catch, no matter who eventually packs, processes, or ships their product. The clear winners of the lobster tariff wars are the Canadian dealers.

“Right now, everything is as good as it can be,” says Leo Muise, executive director of the Nova Scotia Seafood Alliance, which represents over 80 seafood suppliers in Canada’s eastern province. “If the U.S. and China get rid of the tariffs, it’ll have an impact, but I don’t expect the effect to be big.”

Mr. Knott, the lobster-trap maker, is a clear loser. And so are Chinese consumers.

After Chinese countertariffs went into effect last year, imports from the the U.S. dried up and the price of Canadian live lobsters almost doubled, says Liu Gang, a Chinese buyer for the Shanghai Yifeng Food Co., who was attending the Seafood Expo North America in Boston on Monday. Last year, all but one Chinese importer of live lobsters recorded a loss in revenue, he adds.

If you’ve followed the trail to here, then you know tariffs rearrange the competitive landscape. They can give domestic producers some help. But consumers of the countries that impose tariffs often see higher prices, whether they’re buying U.S.-made steel or a North American seafood delicacy in a restaurant in Shanghai.

Points of Progress

In an age of authoritarianism, the world sees glimmers of hope

Globally, we’re seeing rising threats to democracy. But we’re also seeing the demand for accountability and civil rights gaining momentum, challenging autocracy.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Globally, the rise of populist, anti-establishment politicians is indicative of a wider discontent with the current political system, analysts say. But in the past year, citizens of Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic, and Ethiopia have taken to the streets to demand accountability from their governments, while voters in Malaysia and the Maldives ousted corrupt governments at the ballot box. Countries with a strong civil society or decent-sized middle class continue to push back against autocrats, even though the headlines are more often about the threats to democracy.

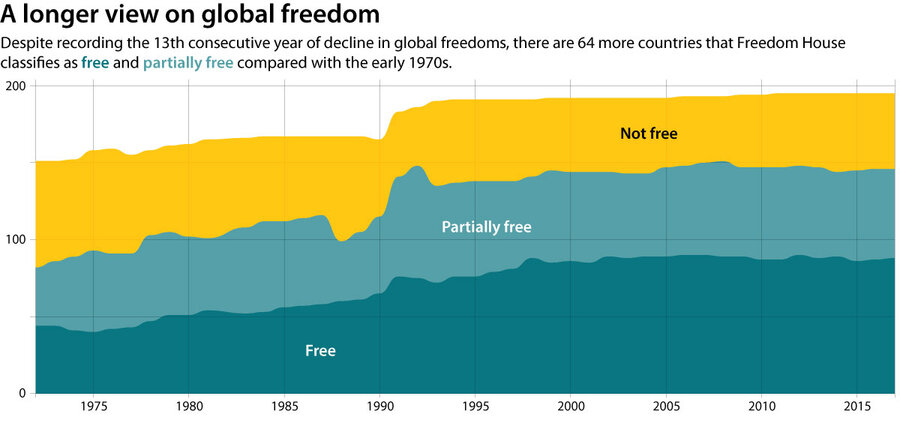

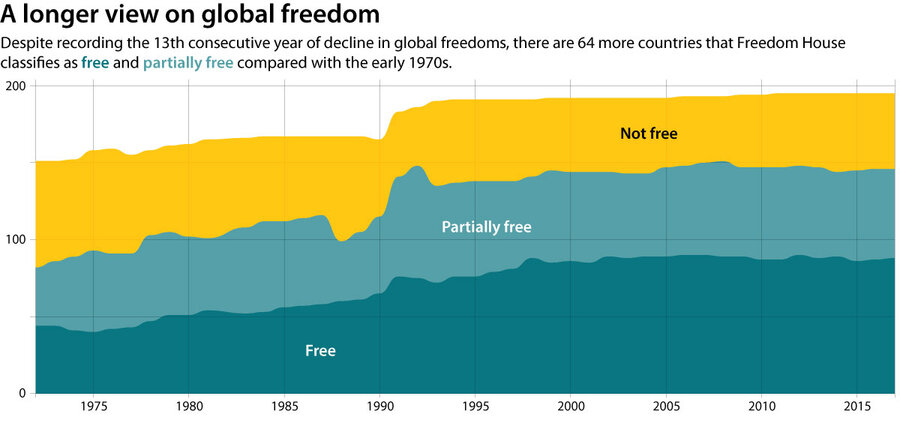

Global freedom, which is composed of political rights and civil liberties, has been in decline for the 13th year in a row, according to a new report from Freedom House. But the same report also notes significant improvement in accountability for corruption in Angola, Armenia, and other nations.

Political participation in most parts of the world has seen a continuous upward trend, reports The Economist. And while autocrats threaten democracies, they are also “fueling a powerful counterattack,” Human Rights Watch notes.

“Those who are bemoaning this authoritarian turn in the world were overstating the case,” says Steven Levitsky, a political scientist at Harvard and co-author of “How Democracies Die.”

In an age of authoritarianism, the world sees glimmers of hope

In the past year, citizens of Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic, and Ethiopia have taken to the streets to demand accountability from their governments, while voters in Malaysia and the Maldives ousted corrupt governments at the ballot box. Countries with a strong civil society or decent-sized middle class continue to push back against autocrats, even though the headlines are more often about the threats to democracy.

That’s not to say democracy has nothing to worry about. A new paper published this month found that the world has been in “a wave of autocratization” since 1994, and as many as 75 democracies have seen a reversal to autocracy. Modern-day autocrats know better than to blatantly shore up power, but do so gradually and under a legal facade, making it harder to detect, researchers say. Autocrats pit authoritarianism against democracy, promoting it as a more efficient form of governance and spreading the technology that strengthens control. Social media amplifies the spread of misinformation, clouding voters’ judgment.

Global freedom, which is composed of political rights and civil liberties, has been in decline for the 13th year in a row, according to a new report from Freedom House. But the same report also notes significant improvement in accountability for corruption in Angola, Armenia, and other nations. Political participation in most parts of the world has seen a continuous upward trend, reports The Economist. And while autocrats threaten democracies, they are also “fueling a powerful counterattack,” Human Rights Watch notes in its latest annual report.

“Those who are bemoaning this authoritarian turn in the world were overstating the case,” says Steven Levitsky, a political scientist at Harvard and co-author of “How Democracies Die.” The euphoric expansion of democracy in the 1990s led to the over-optimistic belief that authoritarianism was a thing of the past, and now that expectation has been dashed, he says. But “there’s yet to emerge a real, viable, truly legitimate alternative to democracy in the world.”

Freedom House

That doesn’t discount the fact that people are disillusioned with traditional political parties and losing confidence in democracy. But rather than disengaging from it, that dissatisfaction is driving citizens to participate in political processes, according to The Economist. Voter turnout and membership of political parties rose, reversing a downward trend. A larger proportion of the world’s population is now willing to engage in lawful demonstrations. The Economist also notes a particularly striking area of progress coming from female participation in politics.

“Women have become much more active, not just in [the] U.S. but around the world,” says Steven Leslie, lead analyst at The Economist Intelligence Unit. “There is an ongoing surge of female participation in politics and in activities that are essential to democracy.” Barriers like discriminatory laws and socioeconomic obstacles are gradually being removed. In Rwanda and Ethiopia, half of the cabinet ministers are women. New legislation in Japan encourages gender parity in parliament. In the United States, the voters in the November midterms elected the highest number of women to Congress in history – though they still make up only 23.7 percent.

Still, the international atmosphere has become less favorable to the expansion of democracy. Not only is the totalitarian state of China spreading its influence, but cracks are appearing in decades-old alliances such as the European Union and NATO. In the EU, both Italy and Turkey saw their rankings in The Economist’s democracy index fall by at least 10 places. Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic, the U.S. is becoming more isolationist, analysts say.

“America’s commitment to the global progress of democracy in its foreign policy has been seriously compromised,” says Sarah Repucci, senior director for research and analysis at Freedom House.

In one example, when the U.S. withdrew from the council on human rights at the United Nations, it left “a huge vacuum of power,” says Rosa Freedman, a professor of law, conflict, and global development at the University of Reading in England and author of several books on the U.N.

Despite the downward trends, however, countries are forming new alliances to put pressure on repressive regimes, reports Human Rights Watch. It points to the example of the EU and a group of Muslim-majority countries working together to create a mechanism at the U.N. to collect evidence on the ethnic cleansing of Rohingyas, which could be used in future trials of the Myanmar government. A group of Latin American countries led a resolution in the Human Rights Council to condemn the severe persecution of Venezuelans under President Nicolás Maduro.

Other human rights mechanisms have sprung up in unexpected places, adds Joseph Saunders, deputy program director at Human Rights Watch. For example, the organizing bodies of big sports tournaments, such as the World Cup and the Olympics, will scrutinize the bidders and hosts’ human rights records.

“These are obviously dark times,” says Mr. Saunders. “But [you] miss a large part of the picture if you don’t see the pushback that is also happening.”

Freedom House

Three million Venezuelans have fled. Now, who will rebuild?

The recent leadership struggle gives many Venezuelans – those who stayed and those who left – hope that change lies ahead. But any political transition would be just the first step on the country’s road to more stability.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

For 14 years, Carlos was a doctor and professor in his native Venezuela. As the country’s economic, humanitarian, and political crises spiraled, he felt a responsibility to stay. Even as shortages intensified, and his earnings dwindled, he hoped he could keep training new doctors, who might one day rebuild the country.

But when his youngest son was born, the crises touched him in new ways. “I knew – I saw it every day in my work – that I was putting my son at risk” by remaining in Venezuela, says Carlos, who now lives in Switzerland. He is one of an estimated 3 million Venezuelans who have left in recent years, accelerating a nearly two-decade trend. Professional fields – from doctors to teachers to lawyers – have been gutted, observers say.

In January, when National Assembly leader Juan Guaidó declared President Nicolás Maduro’s most recent election invalid and called for fresh elections, it sparked hope of change. But that possibility has also sparked tough discussions about how to rebuild a country that’s lost so much human capital. “This is more than brain drain,” says Francesca Ramos, a professor at Rosario University in neighboring Colombia.

Three million Venezuelans have fled. Now, who will rebuild?

Diana Feliú was studying for a master’s in business administration when she decided her future in Venezuela was reaching a dead end.

There weren’t opportunities at home, where inflation has hit more than 1 million percent – making professional salaries, if she could find a job, nearly worthless.

So, in 2014, she left: conducting her thesis abroad, presenting her dissertation via Skype, and asking her mother to walk in her graduation ceremony, receiving Ms. Feliú’s diploma on her behalf.

“In a way, I feel like Venezuela kicked me out. That’s a feeling a lot of my peers share,” says Ms. Feliú, who moved to Mexico in 2015 and found a job within three months. She’s since married, had a child, and gained Mexican citizenship.

“It’s not that I dreamed all my life to leave Venezuela: I had to leave more out of necessity than out of desire.”

Ms. Feliú is one of the estimated 3 million Venezuelans who have fled the country in recent years amid multilayered economic, humanitarian, and political crises, rapidly accelerating a nearly two-decade trend. Professional fields – from doctors to teachers to lawyers – have been gutted, observers say, with some 22,000 medical professionals reportedly leaving Venezuela over the past five years alone.

January brought the first signal of a possible transition of power, when National Assembly leader Juan Guaidó declared President Nicolás Maduro’s most recent election invalid and called for fresh elections, making himself acting president. He received overwhelming international support and sparked a glimmer of hope in many Venezuelans.

But the possibility of change has prompted tough discussions over how to rebuild a country that’s lost so many professionals. Many question how Venezuela can move ahead with such depleted human capital.

“This is more than brain drain. Generations of people effectively trained and contributing or ready to contribute to the country have been forced to leave,” says Francesca Ramos, director of the Observatory on Venezuela at Rosario University in neighboring Colombia. “It’s a huge loss, and it’s very possible that a really, really high number won’t return” home.

From immigration to emigration

For decades, Venezuela served as a beacon for higher education and high-skilled labor in the region.

“Venezuela was one of the first countries in Latin America to have an important number of doctors. It had the muscle of the oil state to encourage that kind of training,” says Dr. Ramos. She struggles to think of countries with similar experiences that could serve as a road map for Venezuela’s rebuilding, saying “it’s such a unique scenario.”

Carlos, who asked not to use his full name because he still has family in Venezuela, left with his wife and small child in 2017 after a 14-year career in medicine: serving as a department head in one of Venezuela’s largest public hospitals, teaching aspiring doctors at a national university, and practicing in a private clinic. Shortages were serious before President Hugo Chávez died in 2013, he remembers, but the situation got exponentially worse.

“I would see patients and just feel impotent,” he says by telephone from Switzerland, where he’s lived for the past 1 1/2 years. “I couldn’t even make a decision because the hospital had no money, patients had no money, there were no antibiotics, and I became this observer of death instead of a doctor. That’s not what I studied for.”

When his youngest son was born in 2014, the weight of what was happening in Venezuela touched him in new ways. “I couldn’t forgive myself for a future where my son had any kind of medical need and I couldn’t do anything. I knew – I saw it every day in my work – that I was putting my son at risk” by remaining in Venezuela.

That’s not to say leaving was an easy decision – or transition.

“I remember conversations with friends where I said I wouldn’t leave the country because we needed to keep training new doctors at the university so that once things improved we could reconstruct the country,” he recalls. “For many, many years, I felt an immense responsibility to stay.” But by the time he left, his 12- to 14-hour workdays were barely earning him $100 per month.

Among professionals who have stayed in Venezuela, lifestyles have changed so drastically over the past decade – and particularly in the past five years – that the middle class has been gutted, says Armando Gagliardi, an economist at the Caracas-based consulting firm Ecoanalítica.

“Their income has been devalued so much that almost 80 percent of what they earn is spent on food. That is traditionally the [spending pattern] of the lower class,” Mr. Gagliardi says.

Uncertain road to return

But as professionals flee, their emigration has consequences for Venezuela today – and likely tomorrow.

Anytime someone wants to visit a dentist or a doctor, the first question is “‘Are they still here?’ ” says David Smilde, a sociology professor at Tulane University, who splits his time between New Orleans and Caracas. “Usually you find that they aren’t. You can’t count on your normal network.”

“The fact that Venezuela is left without these professionals compromises the functioning of the country. Without them there is no health or education,” says Mr. Gagliardi. There are also fewer consumers, creating a damaging trickle-down effect for commerce or street vendors. And finding and retaining employees is increasingly difficult, as people continue to leave.

Their return is key for development, Dr. Smilde says. “There need to be programs to motivate people to come back.”

President Maduro’s “Return Home” initiative has sponsored repatriation for families unable to afford tickets home. The opposition is discussing the need for incentives for citizens to return as well.

Even if Venezuela turns a new political or economic corner, though, many Venezuelan expatriates say the work that goes into setting up new careers and lives abroad means they wouldn’t run home.

Carlos, the doctor, says his family is privileged – his wife is Swiss, which allowed them to move abroad and work. But he can’t practice medicine again until he learns Swiss German and sits for required exams, which he expects to take at least another year.

“We’re asked all the time if we’ll go back. The idea obviously never leaves my mind or my heart,” he says, but doesn’t foresee it anytime soon. Aside from a new political direction, Venezuela will have to rebuild its institutions, he says. “The social deterioration won’t be resolved with a change in government.”

Alejandro Armas, a lawyer who specialized in public administrative law and left Venezuela in 2015, says maybe in the future he and his wife, now living in Buenos Aires, Argentina, could return home.

“If someone calls me to say, ‘Look, we need you in Venezuela to reestablish our administrative or tribunal law,’ I would go running. But my wife wouldn’t follow,” at least not anytime soon. Vacation seems like the most likely reason to return in the short to medium term, say several Venezuelans who fled.

But Dr. Smilde says that if Venezuela sees some kind of transition soon, he’d expect more than 50 percent of the exodus to return – especially older professionals, families, and people who can’t find work abroad “in what they were trained for,” he says, mentioning an architect friend in Miami who now does odd jobs in home repair. “Those are the people that would come back as soon as they could.”

The longer the crises drag on, the less likely rapid returns will be. But it may not be the end for Venezuela if citizens don’t immediately return home, Dr. Ramos says.

“In this global world, there are human flows that could provide a way to help Venezuela forward,” she says. “If it returns to democracy, Venezuela could become a country of opportunity” for other countries’ migrants and refugees.

Mariana Zuñiga contributed reporting from Caracas, Venezuela.

Books

The five best biographies of March

Reading about other lives often enriches our own. A Bill Belichick biography now sits on my bedside table. But my next read is likely to come from the best of this month, including biographies about U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, a female special effects artist in early Hollywood, a Soviet dissident, and the passionate woman who battled a puritanical U.S. president for the right to vote.

-

By Staff

The five best biographies of March

This varied group represents biographies that the Monitor's reviewers found most intriguing this month. It's time to meet a quintet of vital and newsworthy women and men.

1 The Lady from the Black Lagoon: Hollywood Monsters and the Lost Legacy of Milicent Patrick by Mallory O'Meara

Screenwriter and film producer Mallory O’Meara was a teenager when she learned that the iconic monster in 1954 horror movie "Creature from the Black Lagoon" was designed by a woman. Milicent Patrick (1915-1998) was a visionary who worked in an industry very much dominated by men. Her name, O’Meara discovered, had all but disappeared from the annals of Hollywood. "The Lady from the Black Lagoon" describes the author's personal search for Patrick and is equal parts Hollywood history and detective story – and it's thrilling on both counts.

2 First: Sandra Day O'Connor by Evan Thomas

From the opening pages, Evan Thomas shows what shaped the character of future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. Raised on a 250-square-mile ranch along the Arizona-New Mexico border in the 1930s and '40s, Sandra Day grew up in a house that lacked electricity, indoor plumbing, and running water. Her father taught her to shoot a rifle and drive a truck long before she was a teenager. She grew up in a man’s world, always persevering while building the determination and confidence that would lead her to shatter the glass ceiling, culminating with her nomination to the court in 1981 and remarkable 25-year tenure.

3 Monument Man: The Life and Art of Daniel Chester French by Harold Holzer

This is the first comprehensive biography of the prolific American sculptor of public monuments, including the statue of Abraham Lincoln installed in the Lincoln Memorial. Extensively researched, the book is enriched by Harold Holzer’s expertise as an award-winning historian of Lincoln and the Civil War and his broad knowledge of art. Drawing on correspondence, journals, and archival materials, the biography evokes Daniel Chester French’s life and career amid the cultural vibrancy of the Gilded Age. Find the full review here.

4 Vasily Grossman and the Soviet Century by Alexandra Popoff

Western readers who know the name Vasily Grossman (1905-1964) will connect it with his epic 1961 novel "Life and Fate." But the Jewish dissident writer's life was as vivid and gripping as anything he put into his novels, and Soviet expert Alexandra Popoff presents that life with a degree of detail and compassion not yet seen in any English-language publication. Her portrait provides not only the best look yet at this great author's working life but also a stirring study of one man's lifelong fight against totalitarian rule.

5 Mr. President, How Long Must We Wait?: Alice Paul, Woodrow Wilson, and the Fight for the Right to Vote by Tina Cassidy

A progressive, puritanical, and paradoxical president who's both ahead of his time and behind it. A bold, creative, and passionate young woman with nerves of steel. Author Tina Cassidy chronicles the amazing story of how these remarkable forces of nature collided over the battle for women's right to vote. Readers intrigued by historical heroines will thrill to Cassidy's discovery of this forgotten feud and the national battle over women's suffrage.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

After a tragedy, why leaders must be consolers-in-chief

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

This week, after floods that devastated more than half of Nebraska’s counties, Gov. Pete Ricketts toured the state to meet victims, volunteers, and first responders. His trip wasn’t just good politics. It was an empathy tour that proved a force for good. In Ethiopia, following the March 10 crash of a Boeing jet that killed 157, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed visited the site to support those searching for traces of their loved ones.

Yet perhaps the best example of a leader transformed into a consoler-in-chief is Jacinda Ardern, New Zealand’s prime minister. In the days since a white nationalist killed 50 people praying in two mosques, she has shown in actions and words how to embrace the very opposite of the hate the killer stood for.

In difficult times, politicians must be like clergy, full of sympathy, gratitude, and inspiration. When fear is writ large on a place, those fears should not be mirrored back. A leader must elevate feelings of pain by first understanding them. Then, out of such fellowship can come spiritual healing and moral progress.

After a tragedy, why leaders must be consolers-in-chief

When a calamity strikes, leaders must often take on a different role than bold leadership. They must hug victims, console them, and ultimately inspire them with humility and grace to translate tragedy into triumph. This kind of servant-leadership rarely makes the news. But not in recent days.

In Nebraska this week, following floods that devastated more than half of the counties, Gov. Pete Ricketts toured the state to meet victims, volunteers, and first responders. By listening to them, he mirrored a common theme that he found: resilience. “We’ll get through it together and move on,” he said. His trip wasn’t just good politics. It was an empathy tour that proved a force for good.

In Ethiopia, following the March 10 crash of a Boeing jet that killed 157, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed visited the site to support those searching for traces of their loved ones. He expressed a “profound sadness” and sought to bring “healing to friends and families of the bereaved.” He turned their personal grief into a collective grief, thus signaling to the families a wider connection of love. In doing so, he ensured the memories of those lost would be shared by a nation.

Yet perhaps the best example of a leader suddenly transformed into a consoler in chief is Jacinda Ardern, New Zealand’s prime minister.

In the days since a terrorist killed 50 people praying in two mosques, she has shown in actions and words how to embrace the very opposite of the hate the killer stood for.

She donned a headscarf and mourned with the families and friends of the Muslim victims, bringing politicians of other parties with her. She listened more than talked. With genuine tears, she showed solidarity by saying the whole country was “united in grief.” She sent her foreign minister to the home countries of those killed to express sympathies.

She also assured minorities that New Zealand represents diversity, kindness, and compassion. “Those values will not and cannot be shaken by this attack,” she said. In a line now widely known, she said of the victims, “they are us.”

Not all leaders are able to become a voice of moral authority after a catastrophe, showing sincere grief and speaking comforting words. Yet they often are forced to try, reflecting back the mood of a public that seeks a compassionate leader. The desire for redemption and dignity following a crisis demands it.

In 2007, after visiting the tornado-hit town of Greensburg, Kansas, President George W. Bush said, “My mission is to lift people’s spirits as best as I possibly can and to hopefully touch somebody’s soul by representing our country, and to let people know that while there was a dark day in the past, there’s brighter days ahead.”

After the 2012 shooting at a school in Newtown, Connecticut, President Barack Obama said that community “needs us to be at our best as Americans.”

At such times, politicians must be like clergy, full of sympathy, gratitude, and inspiration. When fear is writ large on a place, those fears should not be mirrored. A leader must elevate feelings of pain by first understanding them. Then, out of such fellowship can come spiritual healing and moral progress.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Voting for humility

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Rosalie E. Dunbar

When it comes to politics, says today’s contributor, humility is key. But humility is not the monopoly of certain people or parties. It’s a quality we all can treasure, because it lies in letting God empower everything we say and do.

Voting for humility

Last year I volunteered in a campaign for someone running for office at the state level. As I worked with the other, more experienced volunteers, I was impressed by their humility in talking to voters – really wanting to hear what people felt. And although the candidate didn’t win the primary election, she was gracious in defeat.

To me, she was exhibiting strength in the face of disappointment after such hard work. But it also showed me how to cherish humility in terms of my own attitude toward the candidates who ultimately ran for office. Moving forward, I found myself listening less for speeches that emphasized personal will or personality and paying more attention to promises of a willingness to work with others and to learn how to do a good job – for us, the people.

As candidates begin to jockey for a place in the next presidential election in the United States, I’ve been thinking about the qualities that I would hope for in the individuals representing my community in local and national government. For me, humility is a key one.

Sometimes humility is thought of as being wimpy – just doing the least or letting others decide for you. But the Bible, a book I’ve studied for many years, presents a more spiritual view of true humility as actually strengthening us and as a quality that’s not the monopoly of any particular person or group, but open to all.

Consider Moses, who was just shepherding flocks one day when God commanded him to take on the formidable job of freeing the Israelites from slavery in Egypt and leading them to the Promised Land (see Exodus 3:1-12). Like any normal person, Moses asked, in effect, “Why me? The Egyptian Pharaoh is very important, and I am a nobody by comparison.”

Then God gave him the insight that opened the way for all the good that followed: “Certainly I will be with thee.”

Through my study of Christian Science, I’ve come to see that Moses’ journey wasn’t successful because of any personal power or prowess. It was Moses’ willingness to listen for and act on inspired thoughts from God that made the difference.

Moses was often tested as he struggled with the challenges that came his way from Pharaoh, from the Israelites – who could be ornery at times – and from the wilderness conditions they faced. But one thing that impresses me is that Moses didn’t say he was the one who would solve all the problems. No matter how exasperated he was, Moses turned to God for guidance, and there was consistently a solution.

That is something we can do also. Christian Science explains that we are always at one with God as His spiritual reflection or idea. Christ Jesus made this point very clear when he said, “I can of mine own self do nothing: as I hear, I judge: and my judgment is just; because I seek not mine own will, but the will of the Father which hath sent me” (John 5:30).

That spirit of humility – not my power, but God’s power – is true humility, and it is transforming, while its opposite hinders us, as Mary Baker Eddy, who discovered and founded Christian Science, pointed out. Her “Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896” notes: “Human pride is human weakness. Self-knowledge, humility, and love are divine strength” (p. 358).

In my own life, I’ve seen this to be so and time after time have found that turning to God for guidance, even in small things (and certainly nothing so great as parting the Red Sea, as Moses did!), has led to solutions that bless.

Whether we’re gearing up to run for office or simply going about our daily tasks, each of us can strive to accept God’s loving care, to let Him govern our lives, and to recognize in our own way what Moses and Jesus showed: that God does guide and protect all of us and leads us only to good. Striving to let God empower everything we say and do is a living vote for greater humility in our world.

A message of love

‘Yellow vests’ protests surge

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow. We’re working on a story about the homeless in Italy who are selling newspapers and restoring their dignity.