- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Brexit: new wrinkles, and a vanishing margin of error

Arthur Bright

Arthur Bright

For months, Prime Minister Theresa May has followed a simple plan for getting her Brexit deal passed by Parliament: keep bringing it back for a vote as the March 29 deadline draws closer and closer. Eventually, fear of the United Kingdom crashing out of the European Union without a deal, something widely viewed as a potential economic catastrophe, would stir enough MPs to back her plan.

Ms. May’s first two attempts went poorly, but she gave every indication of sticking to her plan. Then on Monday, Speaker of the House of Commons John Bercow announced that the deal had been dealt with and no new votes would be held on it unless it substantially changed. That derailed her strategy – and increased the likelihood of a no-deal Brexit. So Ms. May wrote to the EU asking for an extension to Britain’s departure date.

Today, European Council President Donald Tusk responded to Ms. May’s request. Yes, the EU would grant an extension – if Parliament voted for Ms. May’s deal. That doesn’t necessarily create a Catch-22. While Mr. Bercow did block revotes on Ms. May’s deal, the change in circumstance that Mr. Tusk’s ultimatum makes may reopen the door to a vote. But the ultimatum does increase the likelihood of parliamentary brinkmanship – and the risk of accidental no-deal.

Ms. May continues to promote her deal, hoping enough will support it to keep Britain from going over the Brexit cliff. Hard-liners in her party, meanwhile, race willingly toward the edge. Labour, though afraid of the chasm, thinks that the EU is waiting to catch Britain with an extension and may be willing to make a leap of faith. And Brussels has to decide whether to keep its nets out to save Britain.

With so many running at the cliff’s edge, the margin for error is vanishingly small.

Now for our five stories of the day.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

How small donors may transform the political landscape

Democrats are eschewing corporate PAC money and riding a massive wave of small-dollar donations. Reform advocates say the trend could give average voters more power to shape the political conversation.

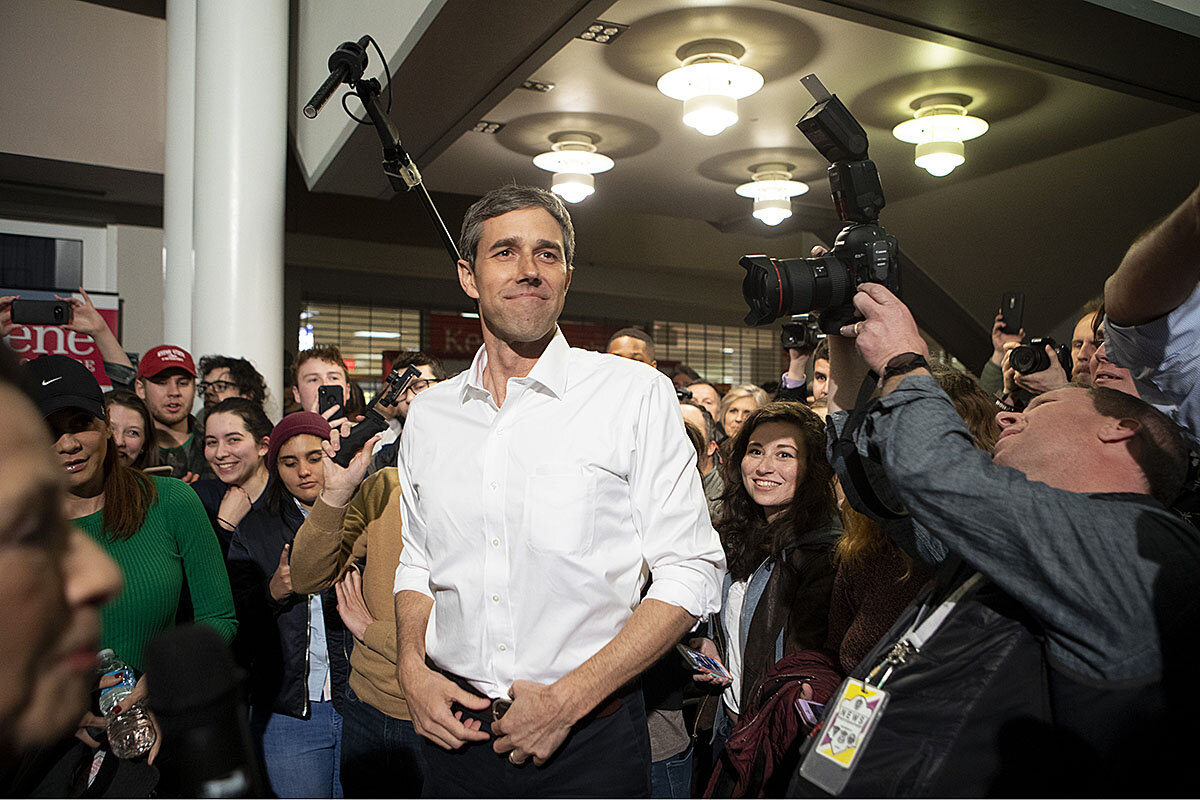

Former Texas Rep. Beto O’Rourke told reporters in New Hampshire Wednesday that 128,000 people gave his campaign an average of $47 on his first day in the 2020 race. That follows Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders reporting last month that 223,000 people donated an average of $27 in the 24 hours after he announced his candidacy.

Both men are riding a surge in grassroots giving that is transforming the entire landscape of money in American politics. For the first time since a 2010 Supreme Court decision opened the way for corporations and wealthy individuals to make unlimited donations anonymously, grassroots donations of $200 or less eclipsed such “dark money” in the 2018 elections.

Now, the 2020 Democratic field is emphasizing small-dollar donations as a sign of credibility and accountability, with most candidates rejecting corporate PAC money. Advocates of campaign finance reform say the shift has the potential to generate a more inclusive style of governance. “This is clearly a new era in many ways,” says Michael Beckel of the nonprofit Issue One. “It means more people will be participating; more people will have skin in the game; more and more people will be shaping the conversations.”

How small donors may transform the political landscape

Beto O’Rourke and Bernie Sanders raked in so much cash within 24 hours of announcing their presidential bids that they made Barack Obama look like a kid with a lemonade stand.

Their massive fundraising – $6.1 million in a day for former Texas Congressman O’Rourke and $5.9 million for Vermont’s Senator Sanders, roughly a quarter of what Mr. Obama raised during the entire first quarter of 2007 – is not just about them or their rock-star status. Both men are riding a surge in grassroots giving that is transforming the entire landscape of money in American politics.

Mr. O’Rourke told reporters in New Hampshire today that his average donation during that period was about $47; for Mr. Sanders it was $27.

For the first time since a 2010 Supreme Court decision opened the way for corporations and wealthy individuals to make unlimited donations anonymously, grassroots donations of $200 or less eclipsed such “dark money” in the 2018 elections.

Now, the 2020 Democratic field is encouraging this trend, emphasizing small-dollar donations as a sign of credibility and accountability, with most candidates rejecting corporate PAC money. Advocates of campaign finance reform say this shift toward grassroots fundraising has the potential to generate a more inclusive style of governance, improving American democracy.

“This is clearly a new era in many ways,” says Michael Beckel, research manager at the political reform nonprofit Issue One in Washington, D.C. “It means more people will be participating; more people will have skin in the game; more and more people will be shaping the conversations” – and the issues that politicians decide to prioritize.

Grassroots fundraising eclipses ‘dark money’

Individual donations of $200 or less more than doubled from 2014 to 2018, to nearly half a billion dollars. During the same time period, the proportion of dark money to small-dollar donations went from 90 to 100 percent to about one-third, according to a Christian Science Monitor analysis of data from the Federal Election Commission (FEC) and the Center for Responsive Politics in Washington.

“I think it’s returning power in our democracy back to where it belongs, which is with the people,” says Patrick Burgwinkle, communications director of End Citizens United, an organization advocating campaign finance reform. "It is making it so the size of your wallet is not what determines the size of your voice in government, because [government] is really supposed to work for everyone.”

In the 2010 Citizens United case, the Supreme Court overturned decades of legal precedent by determining that political spending is a form of free speech protected by the First Amendment. Most conservatives support the decision and oppose campaign finance regulation on those grounds. They also are wary of efforts to push dark money groups to disclose the names of donors, citing privacy concerns after conservatives were targeted by the IRS and others for their political donations.

Liberals, on the other hand, tend to support the idea that just as citizens should have equal weight in voting – that is, one vote per person, regardless of background – they should likewise have equal weight when it comes to spending, so as not to unduly influence politicians in favor of wealthy special interests.

That philosophical difference about campaign finance was reflected in an asymmetrical rise in small-dollar donations on the Democratic side in the 2018 midterms, but Republicans are hoping to adjust the balance.

How ActBlue transformed giving

To a certain degree, the surge in grassroots fundraising is driven by technology, particularly on the left. ActBlue, an online platform for Democratic fundraising, helped liberal groups raise $1.7 billion in the 2018 cycle – nearly half the total amount spent in the election. The average donation was $39.

“There’s no question it’s easier to do now than 15 years ago. But I don’t think it’s just the ease with which people can donate, because the internet works for both parties,” says Mr. Burgwinkle of End Citizens United. “Democrats have really done a good job of cultivating these small-dollar donations.”

That proved crucial in the “blue wave” that enabled Democrats to win back control of the U.S. House of Representatives. In competitive 2018 House races, Democratic challengers raised more than their incumbent opponents, who traditionally have a significant fundraising advantage.

“That is extremely unusual. It’s a first,” says Michael Malbin, executive director of the Campaign Finance Institute. “This has never happened before, and it was fueled in significant part by small donors and even a bigger part by ActBlue.”

Republicans raised less than a third as much as Democrats in small-dollar donations in 2018, due in part to the lack of a platform like ActBlue. In January they announced their answer to the fundraising platform, called Patriot Pass, which they hope will boost grassroots fundraising on the Republican side.

So far the only fundraising numbers for 2020 candidates are those released by the campaigns themselves. The public’s first glimpse into total donations and spending will come April 15, after the FEC releases first-quarter data. Mr. Sanders and Mr. O’Rourke are likely to have among the highest totals of grassroots fundraising.

That shift has been driven in no small part by Mr. Sanders, who proved in 2016 that it was possible to run a viable presidential campaign largely on grassroots donations.

“Bernie Sanders was able to raise an astonishing amount of money and be competitive against the Hillary Clinton money machine because of the power of small donations,” says Mr. Beckel.

Of all the sitting U.S. senators, Mr. Sanders commanded the highest percentage of small-dollar donations in his latest election, and his supporters appear ready to continue the trend. After he announced his 2020 candidacy last month, the Sanders campaign reported that 223,000 people donated an average of $27 each within 24 hours.

Mr. O’Rourke, dressed casually in a white collared shirt with a v-neck sweater and slacks, arrived 20 minutes late to an event Wednesday at an inn in Claremont, New Hampshire, packed with dozens of voters eager to hear what the Texan had to say. None interviewed by the Monitor had committed to supporting him.

He told reporters his campaign saw 128,000 people give an average of $47 on his first day – which confirmed Mr. Sanders’ earlier assertion that the Vermont senator likely had a broader base of donors (though of course Mr. Sanders had the distinct advantage of having already run a national campaign).

The Sanders campaign has portrayed the number of grassroots donors as a key indicator in determining which of the many Democratic candidates could best defeat President Donald Trump.

“The first FEC report is going to send a message about who is the best candidate to beat Trump,” his campaign wrote to supporters, asking for a $3 donation. “Each one matters. A lot. So please chip in today.”

‘Fake news’ in Russia: state censorship elicits an outcry

In any society, how big a problem is “fake news,” and what should be done about it, and by whom? In Russia, the protests over new state censorship moves signed by Putin invoke universal principles.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

A package of new laws meant to crack down on “fake news” and signed this week by Vladimir Putin is stirring an outcry in Russia. Civil society activists, the Kremlin’s own rights council, and a rare street protest have all expressed deep alarm at the prospect of bureaucrats being empowered to shut down any online content that rubs them the wrong way.

The Duma’s fake news law imposes huge fines for publishing any “untrue” report that creates a threat to life, health, public order, and almost any public institution. A second law enables officials to shut down any content that “shows obvious disrespect for society, the state, and official symbols of Russia, the Russian Constitution, or other agencies.”

Analysts say the laws passed by the Duma are only the latest of many attempts to regulate online speech in Russia, most of which have failed to produce much impact in the past. “Like most Russian laws, they are not really meant to be used,” says Alexei Simonov, head of a press freedom watchdog. “They are warning signs. They draw the lines which people should not cross. It’s not clear how these new laws will change the situation.”

‘Fake news’ in Russia: state censorship elicits an outcry

In Russia, the internet has been a freewheeling space for information flow and open debate since its inception.

But the cacophony of conflicting social media voices and the power of internet platforms to facilitate political organization – as well as enable extremists to communicate and multiply their messages – has prompted strong impulses among officials to censor what they see as “fake news,” to crack down in the name of truth.

Now a package of new laws, signed this week by Vladimir Putin, is stirring an outcry in Russia over allowing anyone in authority to decide what constitutes fake news and to determine what to do about it.

Russian civil society activists, the Kremlin’s own Presidential Council for Development of Civil Society and Human Rights, and even a rare street demonstration this month by thousands of internet freedom advocates have all expressed deep alarm at the prospect of bureaucrats being handed the power to summarily shut down any online content that rubs them the wrong way.

Ignoring a request from the Kremlin’s rights council to withdraw the original draft laws and subject them to major revisions, the Russian State Duma went ahead with its blanket fake news law, which imposes huge fines for publishing any “untrue” report that creates a threat to life, health, public order, security, infrastructure, and almost any public institution.

For good measure, the Duma passed a second law enabling officials to shut down any content containing “information expressed in an indecent form which insults human dignity and public morality and shows obvious disrespect for society, the state, and official symbols of Russia, the Russian Constitution, or other agencies that administer government power in Russia.”

Russian analysts say the laws passed by the Duma are only the latest in a long line of attempts to regulate online speech in Russia, most of which have failed to produce much impact in the past. If nothing else, some say, the new laws clarify the battle lines over free speech in ways that might prove productive in the long run.

Let the people decide

“These laws basically give officials a free hand” to determine what is publishable and what is not, says Dmitry Fomintsev, editor of Tochka News, a news portal in the Urals city of Yekaterinburg.

“The day after Duma deputies passed the bill on fake news, we decided to do an experiment,” says Mr. Fomintsev. “We sent an official request to the Duma speaker, Vyacheslav Volodin, asking whether the phrase ‘Christ has risen’ could be regarded as fake news or not? His office responded, saying that’s not a question for the Duma to decide. But, in fact, under this new law, it really is.

“They will try to apply it, as they do everything, in a selective manner to put pressure on the media,” he says.

Before the Duma’s vote and Mr. Putin’s signature, the human rights council sought on its website this month to frame an answer to the dilemma of how to deal with fake news that might serve well in almost any place where people are wrestling with the challenge: Let people decide for themselves.

“[The law’s] provisions for punishing the dissemination of false information … appear to be redundant,” it said. “They also provide a basis for the arbitrary prosecution of citizens and organizations. Practice shows that the best way to counter the spread of false information (the so-called ‘fake news’) on socially important topics is for the authorities to promptly provide the public with the most complete information, as well as permitting a range of independent expert opinions….

“The Council believes that Russian civil society currently demonstrates a sufficiently high level of information competence and the ability to understand the arguments in an open and free discussion. Making management decisions without proper public discussion will only increase social instability in society,” it said.

‘Warning signs’

The new Russian laws supplement previous ones that allowed the government communications watchdog Roskomnadzor to blacklist obscene or extremist websites, as well as legislation that tried to force big internet companies to keep their Russian data on Russia-based servers in the name of “digital sovereignty.” That led to the banning of LinkedIn in Russia, after it refused to comply with the new rules, but the Russian government has so far declined to go after other big companies like Facebook, Twitter, or Google, presumably out of fear of a public backlash.

“There is nothing new happening with these laws,” says Alexei Simonov, head of the Glasnost Defense Foundation, a press freedom watchdog. “Our state has already assembled a wide array of instruments with which to censor, with the goal of protecting power. But, like most Russian laws, they are not really meant to be used. They are warning signs. They draw the lines which people should not cross. It’s not clear how these new laws will change the situation.”

Russian attempts to control the domestic internet date from 2011, when tens of thousands of people took to the streets to protest alleged election fraud. Russian security services noted the widespread use of social media to organize and coordinate the rallies.

“The Kremlin is not so interested in curbing peoples’ access to information. The main concern is the internet’s role in political organization,” says Masha Lipman, editor of Counterpoint, a journal of Russian political opinion published by George Washington University.

“There is no apparent urge among masses of Russians to take to the streets right now, though opinion polls show presidential approval ratings down and economic discontent rising,” she says. “But the Kremlin is interested in sending a strong message to anyone who might be thinking of organizing protests: Be careful what you say or post on the web.”

Isolate the internet

Perhaps more alarmingly, the Kremlin is taking another set of measures that would enable authorities to cut the Russian internet off from the rest of the world or isolate the internet of particular Russian regions in the event of an emergency. This is being presented as a defensive measure to protect Russia in the event of cyberattack from outside, but it would also make it possible to prevent unrest from spreading from any locality where it might break out.

“The new law will require special equipment to be installed in internet exchange points, so that traffic could be redirected and regional internets shut down,” says Andrei Soldatov, author of The Red Web, a history of the Russian internet. “There is a series of drills underway. It’s basically a work in progress.”

Russian analysts say the most worrisome aspect of the new measures is that the determination of what is permissible online is being increasingly taken from the courts and placed into the hands of officials.

“If the procedure for deciding what is fake news becomes more bureaucratic, that makes it faster and more efficient from the government’s point of view,” says Ms. Lipman. “The new law specifies that objectionable content should be blocked ‘immediately.’ That suggests that some official will decide that people should not see something, and it will be blocked at once. That’s the way things are going.”

Legal pot: Why minorities say they’re being left out of the money

The story of marijuana and racial equity has mostly been about crime and punishment. Is that changing in an age of legality and commerce?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Legal cannabis is expected to be a $30 billion North American market by 2022. Minority entrepreneurs make up about 5 percent of ownership – a vivid example of how tightly race remains entangled in laws surrounding marijuana.

Fed up, black lawmakers from New York to Georgia are threatening to scuttle legalization bills unless there are guaranteed concessions for neighborhoods scarred by drug wars. To some, such revolts are a sign of turmoil inside the legalization movement. But for others, it is a fundamentally moral fight: a reckoning for an eight-decade government drug war.

In Georgia, cannabis advocates have pushed back against demands from black legislators.

“My opinion is, let’s get something on the books and then work with it,’ ” says Tom McCain, director of Peach State NORML. “I don’t think [social justice] is a reason to kill a bill.”

Some black lawmakers and their supporters disagree.

“There is a great sense of distrust based on the historical precedent, the classical bait and switch where minority communities are used as political fodder to get an agenda passed, and then afterward there’s a great sense of amnesia about the promises and commitments made,” says the Rev. Reginald Bachus. “We can’t be the first to jail and the last ones to the bank.”

Legal pot: Why minorities say they’re being left out of the money

The day is coming. Chris Butler can feel it.

The Atlanta businessman – a churchgoing, middle-aged black man – says he will be ready if cannabis legalization comes to this corner of the South. He claims he already has a devoted clientele, a stash of seeds, and a “sweet plan” for a grow room with a “hydroponic brain.”

Yes, this is stop-sign-red Georgia, which along with Texas and New Jersey leads the nation in marijuana arrests – some 27,000 last year.

But Atlanta and Savannah have decriminalized possession of an ounce or less, which has led to a 70 percent drop in arrest rates. A convenience store in Atlanta’s upscale Candler Park advertises “CBD oil here,” referring to a medicinal marijuana product approved by the Republican-led legislature.

And Coca-Cola Co., the iconic Atlanta soda-maker, is quietly developing a cannabis product.

Yet Mr. Butler also understands a fundamental fact: Given his race, past arrests for nonviolent offenses, and lack of wealth he may never be able to join an emerging pot shop trade.

“You’ve got a country where a guy who is selling weed in one state goes to prison and the guy rolling joints in the next state over gets rich!” says Mr. Butler, who asked that his real name not be used so that he could talk freely. “It’s not fair, it never was fair, and it might never be fair.”

‘Vertical integration of exclusion’

According to the Rev. Reginald Bachus of Abyssinian Baptist Church in New York’s Harlem neighborhood, Mr. Butler and his cohorts are being shoved aside by what Mr. Bachus calls “vertical integration of exclusion” as Big Cannabis speeds toward a $30 billion North American market by 2022.

Minority pot dealers “are the ones who helped design the business model, so how can they not participate when it’s legalized and when others who once frowned upon [cannabis] now see an opportunity?” he asks.

The relative absence of African-American entrepreneurs, who make up only about 5 percent of the legal industry’s total ownership stake, is a vivid example of how tightly race remains entangled in laws surrounding marijuana.

Fed up, African-American lawmakers from New York to Georgia are threatening to scuttle legalization bills unless there are guaranteed concessions, if not reparations, for neighborhoods scarred by drug wars. Ohio, California, and Washington states are also addressing a host of post-prohibition questions, including whether to expunge marijuana convictions, the bulk of which are faced by black Americans like Mr. Butler.

The U.S. has now “begun to recognize the third generation of legalization,” says Steven Bender, a law professor at Seattle University and author of “The Colors of Cannabis,” a law review article. “The first generation was medical, the second was recreational, and the third is race consciousness.”

To some, such revolts in New York, New Jersey, and elsewhere are a sign of turmoil inside the legalization movement. But for many, it is a fundamentally moral fight: a much-needed reckoning for an eight-decade government drug war in which critics say the U.S. has yet to fully address “how to repair the harm caused,” as Union Theological Seminary visiting professor Michelle Alexander has put it.

At the very least, it may infuse marijuana policy with, as Mr. Butler hopes, “some actual honesty about what is going on.”

“Social equity is becoming a bigger issue in this industry as more states consider legalization,” says Chris Walsh, founding editor of Marijuana Business Daily, a Denver-based trade magazine.

To be sure, marijuana possession is still illegal under federal law – with producers, in theory, facing a federal death penalty if caught growing 60,000 plants or more. (No one has been executed for marijuana offenses, though people have been sentenced to life in prison.)

Yet the federal government in recent years has taken a mostly hands-off approach to state experimentation. Ten states plus Washington, D.C., have legalized recreational marijuana, and more than half the country allows limited medical use – including Arkansas, Georgia, and Florida.

But promises from cannabis advocates that the end of prohibition would not just protect, but lift, minority communities so far have amounted to a “pump-fake,” says Mr. Bachus.

Black Americans remain 3.7 times as likely to be arrested for marijuana possession as white Americans, according to the American Civil Liberties Union, even though usage rates are the same on average. Marijuana has been legal for adults in Colorado since 2014. Today, more than three-quarters of those arrested for underage or public use, or driving while high, are black residents, who make up just 5 percent of all Coloradans.

Historians tie these racial disparities back to the 1930s when Federal Bureau of Narcotics Commissioner Harry Anslinger used racist tropes to target marijuana users as crazed minorities bent on hypnotizing white women into vice – a condition popularized as “reefer madness.”

“The war against cannabis has always been a racist war,” says Barney Warf, a social geographer at the University of Kansas in Lawrence.

Yet as some black leaders, including presidential candidate Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., call for reparations for the war on drugs, another narrative should be considered, argues University of Dayton historian Adam Rathge.

For one, rural white Americans have been targeted for drug prosecutions at similarly disproportionate rates as urban African-Americans.

And while it is true that much of prohibition was laced with anti-Latino and anti-black political fervor, some early opposition to cannabis came from northern states with small minority populations. In those cases, the concern may have been safety rather than morality.

In that way, at least part of criminalization “may have been more progressive regulatory zeal than racism or xenophobia,” says Mr. Rathge. “One way to frame this is that these laws – from criminalization to decriminalization – are passed to protect white children, but what they end up doing is harming minority communities, even though that wasn’t the full impetus for passing them in the first place.”

The message of a $250,000 dispensary permit

Whatever the cause, the effect on minority communities has been inarguable.

The idea of legalization more broadly “really has been, let’s take it from dealers of color who are operating in this violent underground and bring it aboveground through reputable businesses,” says Professor Bender. “So really what voters were deciding was between the shady drug dealer of color and their local friendly storefront, with monies now going to the government. That’s a slam dunk.”

That has added suspicion among black lawmakers about where the legal market is going – and who will ultimately benefit.

Already, mom-and-pop growers and dispensaries are being pushed aside, and with them hopes for a more diverse marijuana shopkeeper class. Last week, the MedMen corporate dispensary was disavowed by The New York Medical Cannabis Industry Association after a lawsuit emerged alleging that the founders engaged in racist speech.

Moreover, criminal justice policies have left African-Americans’ records disproportionately marred, squeezing their entry into a heavily regulated market. And then there’s the wealth gap: The proposed cost of entry in New York legislation would include a $250,000 dispensary permit.

“For a lot of those communities, [benefiting from legalization] is almost a mountain that cannot be surpassed unless there is some help on that point,” says California attorney Thomas Moran, author of “Just A Little Bit of History Repeating Itself,” an article that ran in the Washington and Lee Journal of Civil Rights and Social Justice.

Holding up legalization

Last week, New York lawmakers said they would hold up legalization if they can’t get guarantees that substantial pieces of new tax revenues would go to disadvantaged communities hurt by prohibition enforcement. New Jersey lawmakers, too, are demanding guarantees that legalization will look exceedingly diverse.

In Georgia, where negotiations over legalization as well as a new hemp bill are already complex, cannabis advocates have pushed back against demands from black legislators.

“We’ve had folks trying to block these bills because there is no social equity written into ... them, but my opinion is, let’s get something on the books and then work with it,’” says Tom McCain, director of Peach State NORML, which lobbies for legalization. “I don’t think [social justice] is a reason to kill a [legalization] bill.”

Some black lawmakers and their supporters disagree.

“There is a great sense of distrust based on the historical precedent, the classical bait and switch where minority communities are used as political fodder to get an agenda passed, and then afterward there’s a great sense of amnesia about the promises and commitments made,” says Mr. Bachus. “We can’t be the first to jail and the last ones to the bank.”

Marijuana Business Daily August 2017 reader survey

Restoring Indonesia’s peatlands to their natural soggy glory

One-size-fits-all agriculture has robbed Indonesia’s peatlands of their moisture. Now the country is working to restore these historic swamps by embracing rather than fighting their boggy nature.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

-

By Daniel Grossman Contributor

Peatlands aren’t supposed to catch fire; they are soggy bogs, after all. But over the past 20 years, Indonesia’s peatlands have become tinderboxes as corporate plantation growers drained these historic swamps to grow oil palm and acacia.

When severe drought hit in 1997, thousands of years’ worth of undecayed plant matter burst into flames. The whole country seemed to burn, releasing as much as 10 billion tons of CO₂ in several months – almost twice as much as the entire United States produces in a year. Conflagrations now recur nearly every dry season.

The fires have served as a wake-up call for the government, which in 2016 promised to dam and fill in canals across nearly 8,000 square miles of peatland by 2020. Slowly, dryland crops are giving way to swamp-faring flora such as the sago palm. Today, locals in Sumatra view the sago with reverence. “This is like villagers’ savings,” says Abdul Manan, motioning to his 12-acre stand of sago, “to pay for the children to go to school, to middle school, to university.”

Restoring Indonesia’s peatlands to their natural soggy glory

A picket fence encloses a single sago palm in Sungai Tohor, a village of 1,300 on the coast of Sumatra. A billboard to the right gives title to the bushy tree: the Jokowi Sago Monument. Jokowi is the nickname of Indonesia’s president, Joko Widodo. The tree was planted in his honor when he visited in 2014.

Abdul Manan, the farmer and entrepreneur who drives me to the sago shrine on the back of his beat-up motorcycle, says it’s no surprise that villagers are proud of this palm. Sago is the most important crop in this part of Indonesia.

“This is like villagers’ savings,” he says, “to pay for the children to go to school, to middle school, to university.”

Mr. Manan himself owns a 12-acre stand of sago and a mill for grinding up its pulp, an edible starch. He produces packets of coconut-flavored balls of roasted sago and bags of sago pasta.

Just before President Widodo’s visit, wildfires had swept through Sungai Tohor and other parts of the province of Riau. Fires have devastated Borneo – an island that Indonesia shares with Malaysia and Brunei – and Sumatra for decades. The incessant blazes reduce oil palm and acacia plantations to ashes and incinerate dwindling patches of natural forest, home to orangutans and pygmy rhinos. Fires have exposed millions of Indonesians, Singaporeans, and Malaysians to toxic air pollution.

Indonesia’s wildfires also release vast amounts of carbon dioxide (CO₂), contributing to global warming, embarrassing the Indonesian government, and impeding international efforts to slow climate change. Further conversion of forest to fire-prone industrial plantations “must be stopped,” President Widodo declared to an entourage of Indonesian journalists during his stay at Sungai Tohor. Give the land to family farmers instead, the president said, “so they can use it to plant sago.” Mr. Manan, the sort of small-time grower he was talking about, listened at the edge of the crowd.

President Widodo’s pronouncements may have helped to create a recent surge in sago production. It certainly raised the visibility of the cultivation of swamp-adapted trees, a fire-resistant form of farming dubbed paludiculture. If widely adopted, paludiculture could make Indonesia’s land less prone to fires, protecting the health of residents and cutting off a globally significant source of CO₂ emissions. It would also protect the long-term viability of farming on Indonesia’s coastal plains, where fires have been a persistent problem.

The dryland illusion

Hans Joosten, an ecology professor at Germany’s University of Greifswald, says Indonesia’s fire troubles can be traced, literally, to the dawn of Western civilization.

“The Western way of agriculture has as its cradle the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East,” he says, an arid region with infrequent rainfall.

The ancestral agriculturalists of European civilization domesticated plants and animals and developed tools and techniques for dry conditions. Europeans later adopted the “dryland philosophy,” spreading it, along with the empires, around the world. After conquests, they favored adopting dryland crops – potatoes and corn, for example – even where farmers also grew wetland plants.

Professor Joosten says this history led to “the illusion that productive land has to be dry,” even though “wetlands belong to the most productive areas in the world.”

Even rice – a seeming exception, farmed in flooded fields – requires dry soil for part of the year. It won’t grow in perpetually soggy ground.

Wetlands are common around the world, yet they’re seldom farmed before being drained. Most farms in the Netherlands, where Professor Joosten grew up, were natural wetlands before settlers “reclaimed” the land by drying it with its legendary network of dikes and canals.

Until the past several decades, waterlogged peatland covered in dense jungle completely rimmed Sumatra and Kalimantan – Indonesia’s portion of Borneo – a Florida-size area. Peatlands are wetlands in which dead trees’ roots rot exceedingly slowly. The undecayed plant matter builds up year after year, creating deep, spongy deposits.

Only indigenous tribes – who hunted monkeys and indigenous pigs there – paid much attention to Indonesia’s peatlands. The soggy jungle floor defied mechanized equipment, blocking industrial logging. None of Indonesia’s major crops tolerate their perpetually high water.

Peatlands store huge amounts of carbon – up to 100 times as much as the wood in trunks and branches of the trees that grow on them. Indonesia’s peatlands, which have accumulated for 15,000 years, are 60 feet deep in places.

In contrast to other wetlands, peatlands become highly flammable when drained. In Ireland and other parts of the world, dried peat heats homes and fuels power plants. Because of their immense volume, Indonesia’s peatlands generate huge amounts of CO₂ and continental-scale clouds of toxic pollution when they catch fire.

But the virgin peatlands rarely burned. Peatland jungles are quite fireproof. Mr. Manan, the sago farmer, shows me why.

“Roll up your pants,” he says, tucking his into the cuffs of rubber boots. Springy soil squishes noisily underfoot.

A few steps into the woods, he brushes away a tangle of palm fronds, revealing a PVC pipe sticking a few inches above the ground. He pulls out a long, straight dowel that, like a car’s dipstick, measures the position of the forest’s water table. Reddish droplets – tannin and other decay products in peat-color groundwater – drip off the end, showing that the water table is only a couple feet below the surface. Even during Sumatra’s dry season, Mr. Manan says, the combination of groundwater below and rainwater above keeps the soil sopping wet.

A fiery ‘wake-up call’

The tranquil preindustrial state of the peatlands ended in the 1990s. Timber companies began running out of easy-to-harvest upland trees and turned their attention to the less-accessible swamps. Between 1990 and 2015, woodcutters harvested nearly three-quarters of the peatland forests on Sumatra and Kalimantan, an area half the size of the United Kingdom. The cleared ground was too soggy for dryland crops. But companies with government concessions excavated thousands of miles of canals, dehydrating the soil. Then they planted oil palm, to satisfy the exploding global demand for biofuels and alternatives to hydrogenated oil, and fast-growing acacia trees, a source of paper pulp. Family farmers, with little capital and no relevant expertise, rarely made use of these cleared swamps. They’d always carved their garden plots from dryland parcels layered with fertile mineral sediments on riverbanks.

The corporate plantation growers sowed the saplings of their own destruction, however. For years experts warned that the plantations’ drained peat was dangerously flammable. They also said that the desiccated wetlands would subside. In its natural state, peat is up to 95 percent water. Once dehydrated, it compacts and slumps year after year. Eventually the surface sinks below sea level. Unless protected by dikes and continuously pumped – methods employed in the Netherlands but impossibly expensive in Indonesia – the land becomes inundated with salt water and infertile.

In late 1997 Indonesia suffered a scorching drought. As predicted, the peatlands burst into flames. The whole country seemed to burn. One estimate suggests that between 7 and 34 percent of Indonesia’s peatlands ignited. Scientists piecing together what happened later calculated that the fires released 3 to 10 billion tons CO₂ in several months, possibly as much as the entire United States and all of Europe produce in a year.

The fires were “a wake-up call,” says Wim Giesen, a Dutch consultant with Euroconsult Mott MacDonald, who has advised the Indonesian government how to respond. Still, Indonesia continued draining peatlands carelessly for two more decades.

Conflagrations now recur nearly every dry season, turning Indonesia into the third-highest source of climate-warming CO₂.

In 2015, the smoke was so thick “you couldn’t see the house across the street,” recalls Laura Graham, a biologist at the Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation. Dr. Graham works in Palangkaraya, a city carved from peatlands in Kalimantan, where she monitors efforts to restore damaged forest. Pollution from 2015’s fires killed 100,000 people in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. The World Bank has concluded that it cost Indonesia $16 billion in economic damage.

“The good thing about the 2015 fires,” says Dr. Graham, “was that people finally stood up and said ‘We can’t keep doing this.’ ”

Nurturing a paradigm shift

In January 2016, President Widodo created the Peatland Restoration Agency, an arm of the government for coordinating efforts to rewet desiccated swamps. The goal is to dam and fill in canals across 2 million hectares (nearly 8,000 square miles) of peatland by 2020.

What’s needed is “a paradigm shift in thinking, going from crops that require drainage to crops that require rewetting,” says Marcel Silvius, the Indonesia representative of the Global Green Growth Institute, an environmental group operated by 30 member countries. Many peatland experts want the government to raise water tables to natural conditions, where water bubbled up above the surface of some land during the wet season and dropped to just below otherwise. But this would end oil palm and acacia production on a territory larger than Belgium. The government has split the difference, requiring that water tables be raised slightly but not so high as to endanger industrial plantations. Still, a shift from dryland agriculture to paludiculture has begun.

After touring Sungai Tohor’s sago groves and pulping mills, Mr. Manan drives home, showers, and changes into a fresh sarong, a traditional batik shirt, and a black velvet peci, the fez-like hat Indonesian men wear on formal occasions. Seated on the floor of his modest wood-frame house, he serves a dinner of hot tea and fresh sago pasta smothered in greens and peanut sauce.

“Delicious,” he says in English.

Later that evening, a small cargo ship pulls up to a nearby dock. A crew of roustabouts loads it with 15 tons of sago paste from Mr. Manan’s mill for dealers in Singapore, 70 miles across the Malacca Strait.

Sago, a staple for centuries in New Guinea and Borneo, is by far Indonesia’s most important paludiculture crop. Farmers – mostly small-timers such as Mr. Manan – produce about 50,000 tons of it a year, an amount that has tripled since 2013. In addition to being used to make sago pasta, it’s used in baked goods such as cookies and cakes.

“There’s potentially a huge market for it,” says Mr. Giesen, the Dutch consultant. He says that for paludiculture to gain widespread acceptance, more wetlands crops with proven markets must be demonstrated.

“You don’t want people too dependent on one or two products,” he says.

Five years ago, Mr. Giesen, a botanist by training, compiled a list of 1,500 plants with known uses that grow in Indonesia’s peatland forests. He winnowed this down to 80 plants that have or have had “major economic importance.” The short list includes the trees jelutong, a source of natural rubber; galam, which produces a medicinal oil in its leaves, flowers favored by honeybees, and sturdy construction timber; and tengkawang, which produces quantities of nuts containing cocoa-butter-like fat.

Any of these plants have potential to replace swaths of existing plantations of oil palm and acacia. But in most cases the existing market for their products is limited or nonexistent.

They’ll “need nurturing,” says Mr. Giesen.

For instance, food and cosmetic manufacturers already satisfied with cocoa butter would have to be induced to consider tengkawang nut butter. Natural chewing gum makers would have to be persuaded to replace Mexican chicle for jelutong's rubbery sap.

Moreover, Mr. Giesen’s plants haven’t undergone domestication that could increase their economic potential. Professor Joosten, who coined the term paludiculture in 1998, points out that the productivity of dryland crops such as corn has multiplied a thousandfold over the native species from which they emerged. Tractor combines, pesticides, storage containers, and shipping equipment have been engineered for decades or longer to lower the cost of bringing today’s top crops to market.

“The entire value chain has been optimized,” he says. In contrast, “We’re in the early Neolithic of paludiculture.”

On the front lines of the battle to rewet Indonesia’s peatlands is Hesti Tata, a forester who promotes paludiculture for the Ministry of Environment and Forestry. Like Ray Kinsella, who turns a corn field into a baseball diamond in “Field of Dreams,” it’s her job to tell family farmers that the if they plant wetland trees such as jelutong, demand will come.

It’s not always an easy sell. Farmers are not used to working soggy fields, and they fear there will be no buyer when the saplings she offers them mature. Sometimes Ms. Tata worries that her advice might lead them astray. The government might have to ban dryland farming on peatlands for paludiculture to take off, she says. Otherwise, “there will be no significant increase in Indonesia.” With so much of Indonesia’s peat going up in smoke each year and adding to global warming, we might all be worse off for it.

This story was produced with support from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, the Frank B. Mazer Foundation, and the Energy Foundation.

Restoring Indonesia's peatlands

For Italy’s homeless, salvation in selling newspapers

A recession and punitive populist policies are exacerbating homelessness in Italy. One publication is offering purpose and income by putting homeless people to work as newspaper vendors.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Dominique Soguel Correspondent

Some 5 million out of 60 million Italians are living in poverty, according to the Italian National Institute of Statistics. Along with Rome, Milan has the highest concentration of homeless people in Italy, at least 3,000 by most counts. Vito Anzaldi, a former maintenance worker, used to be one of them.

When he became unemployed, things went downhill so much he found himself sleeping on park benches. A turning point arrived when he became a street vendor for the Italian publication Scarp de’ tenis (“Tennis Shoes”). Founded in 1994, Scarp de’ tenis employs some 130 vendors across about a dozen Italian cities, roughly half of them in Milan. The publication is partially funded by the Catholic charity Caritas.

As Italy copes with an economic recession and a populist government whose policies may harm more than help its homeless population, the role of organizations like Scarp de’ tenis may become even more important. Mr. Anzaldi now lives in municipal housing and has found purpose as well as a steady if modest income with the publication. He says, “The act of selling this newspaper saved my life.”

For Italy’s homeless, salvation in selling newspapers

Vito Anzaldi, a stocky Sicilian who made a living doing maintenance and an array of jobs for a multinational in Milan, melted into homelessness slowly. Things went downhill in the late 1980s after he became unemployed.

Initially he had enough savings to survive a few years. He owned four apartments in and around Milan. That became two apartments, one to live in with his family, the other to rent for income. Financial pressure widened the cracks in his marriage.

“When the money goes down, the fighting goes up,” Mr. Anzaldi explains over coffee. “One regular day of our usual quarrels and craziness, I lost my mind. I took the car and left home. I had €300 ($340) in my pocket.”

Unable to find work, Mr. Anzaldi began sleeping on park benches or in his car, reserving €50 so he could afford gas to get to work if a job came up. “For three years I became invisible,” he says.

His turning point arrived when he became one of dozens of street newspaper vendors who turned their lives around selling the Italian publication Scarp de’ tenis (“Tennis Shoes”). “The act of selling this newspaper saved my life,” he says after a weekend of sales outside churches in February.

Along with Rome, Milan has the highest concentration of homeless people in Italy, at least 3,000 by most counts. Some 5 million out of 60 million Italians are living in absolute poverty, according to The Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT).

“Homelessness is on the rise because the situations that create homelessness are on the rise,” says Roberto Guaglianone, who coordinates street sales at Scarp de’ tenis. Italy slipped into an economic recession at the end of 2018.

The number of working poor, he notes, is likewise growing. “They are going to the [charity-run] food tables to eat. They might just be able to pay rent, but they don’t have enough to cover food.”

Founded in 1994, Scarp de’ tenis employs some 130 vendors across about a dozen Italian cities, roughly half of them in Milan. The publication — which derives its name from a song by Enzo Jannacci, one of the founders of Italian post-war rock and roll — is partially funded by the Catholic charity Caritas.

Scarp de’ tenis carefully selects its vendors, drawing on recommendations from Caritas and the municipality. They privilege those who have found some kind of shelter and avoid those who engage in substance abuse.

Most vendors are Italians like Mr. Anzaldi or Anna di Toma, a 62-year-old from the southern Italian city of Apulia who plunged into poverty after divorcing and discovering that she was considered too old to enter the workforce.

Each copy sells for €3.5, of which the vendor keeps €1. The rest is reinvested in production. “Salvation,” stresses the editorial team, comes from the “dignity of work.” Journalists provide content pro bono, and vendors can also share their own personal stories under their own byline.

“The goal is to have a social impact not only on the lives of the vendor, but also in the heads and the hearts of people around them,” says Mr. Guaglianone.

Populist policies: boon or bane?

Italy never fully recovered from the 2008 global economic crisis and is now in recession, which set the stage for the rise of the right-wing League Party and the anti-establishment Five Star Movement. Together they govern Europe’s third-largest economy.

Charity workers fear that populist policies will make the battle against homelessness harder. They point to the Decree-Law on Immigration and Security, championed by far-right League leader and interior minister Matteo Salvini, which abolished humanitarian protection for migrants ineligible for refugee status. This is leading to the closure of shelters and putting more people on the streets.

“We have estimated that in the next few months, as a result of the Salvini decree, about 800 migrants will become newly homeless and end up on the streets of Milan,” says Pierfrancesco Majorino, alderman of social policies in Milan.

The Five Star Movement is offering a “citizenship income,” a monthly benefit of up to €780 euros ($885) that aims to bring folks into the labor market by requiring some training and active job-seeking. It will be offered to Italian nationals, EU citizens, and longtime residents who are living below the poverty line.

Skeptics worry this measure may not be effective in bringing people into the labor market and instead stress the importance of widespread job creation. Critics also warn it leaves out the most vulnerable, the homeless, by including a 10-year minimum residency requirement.

“The new law wanted to exclude the foreigners,” explains Stefano Lampertico, head of Scarp de’ tenis. “When you end up on the streets, you lose residency. And when you lose residency, you lose all your rights. As a result, many come to charities like Caritas, which offers anagraphic residency,” adds Mr. Lampertico, referring to symbolic rather than physical residency.

‘It is difficult for anybody.’

Of course, homelessness is a multifaceted problem demanding diverse solutions. Lack of documentation is a major problem for foreigners. For Italian nationals, it’s economic and personal challenges, like broken marriages, addictions, and health issues.

Milan plans to open four assistance centers where individuals can apply for residency to allow a larger share of the homeless to get basic benefits such as identity documents and health cards.

Roman Gianpiera and Walter Scarabella, a couple who met outside Milan’s central station and spent years sleeping in stationed train cars, say they are among those who would be left out in the welfare system overhaul.

They live in a village of prefabricated housing but are itching to get out. “If they don’t find a solution for us soon, you will read about it in the newspapers,” says Mr. Scarabella, who had a stroke last year.

It’s difficult to get a job in Italy even under the best circumstances, says Mario Furlan, founder of City Angels, an Italian charity that offers professional training. “The real challenge is to help those who can work to find a job,” says Mr. Furlan. “It is difficult for anybody.”

Mr. Anzaldi, who now lives in municipal housing, feels fortunate to have a steady if modest and variable income with Scarp de’ tenis. While he has developed the courage to tell his story to congregations and children, he has yet to share that painful chapter with his daughter who still blames him for his three-year absence.

“Shame kills,” he says.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The ethics of watching a massacre video

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Friday’s massacre in New Zealand was livestreamed on Facebook. A video of it was shared across the internet. The killer’s bid to exploit the digital universe for his murderous cause has led many social media users to close their accounts. Some hope to join a 50-hour boycott of Facebook this Friday, or one hour for every shooting victim.

Jacinda Ardern, New Zealand’s prime minister, has asked people not to use the killer’s name, as he has done enough to mythologize himself with a viral visual. Such responses hint at the desire to better choose what we watch and to insist that media facilitators like Facebook better filter content. Yet the need for internet users to develop instant discernment remains.

The first step is to avoid the temptation of voyeurism. Then users must learn why they should deprive a mass audience for those who would livestream a depraved act. If a killer is unable to amplify his or her actions online, the killer might not inspire copycats. The tech giants can do only so much. The ethics of seeing still lies mainly with the seers.

The ethics of watching a massacre video

In her famous writings on photography, the late pundit Susan Sontag worried about the “ethics of seeing,” or the choices we must all make about what images to allow into our sight. She may never have imagined the unprecedented case of a massacre being livestreamed on Facebook and then a video of it quickly shared across the internet, as happened during Friday’s mass killing in New Zealand.

For many, viewing the massacre was just one click away.

A debate over the ethics of watching or, more importantly, transmitting the video is more timely than ever. The killer’s intent to exploit the digital universe for his murderous cause has led many social media users to close their accounts. Some hope to join a 50-hour boycott of Facebook this Friday, or one hour for every shooting victim. Business associations in New Zealand plan to pull ads from the platform.

The country’s prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, has asked people not to use the killer’s name, as he has done enough to mythologize himself with a viral visual. “Speak the names of those who were lost, rather than the name of the man who took them,” she said.

Such responses hint at the desire to better choose what we watch and to insist that media facilitators like Facebook better filter content. For several years, tech giants have designed special algorithms to detect offensive material and, if that fails, they have armies of content checkers. Last Friday, both Facebook and Google’s YouTube moved quickly under public pressure to take down the massacre video.

Yet the need for internet users to develop instant discernment remains. The first step is to avoid the temptation of voyeurism. Then users must learn why they should deprive a mass audience for those who would livestream a depraved act. The reason: If a killer is unable to amplify his or her actions online, the killer might not inspire copycats.

The new norm is not to normalize images of violence or the hate behind it. “Deciding to turn away from hate and pursue its opposite is a daily decision and a daily act, one we must constantly recommit to as vigorously as possible, in spite of all the obstacles,” writes Sally Kohn, a CNN commentator, in a new book, “The Opposite of Hate.”

Another pundit who wrote about photography, Susie Linfield, says moving images are particularly alluring. They can cause viewers to abandon themselves. After watching a horrific video, however, they must reassert their autonomy and their “heightened presence of mind.”

People in New Zealand and around the world are now trying to recover that “heightened presence of mind” after the massacre. The tech giants can do only so much. The ethics of seeing still lies mainly with the seers.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Finding and living up to our true potential

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Hans-Martin von Tucher

What if your academic grades aren’t all that you would want them to be? Today’s contributor was told he wasn’t equipped to succeed at school. He shares spiritual ideas that changed his perception of his potential, enabling him to successfully complete a bachelor’s as well as a master’s degree.

Finding and living up to our true potential

For various reasons, including the closure of German schools after World War II until such time as teachers could be “de-Nazified” or replaced, growing up in post-war Germany I did not have any serious and systematic schooling until I was over 9 years of age. As a result, I received consistently poor grades throughout my schooling thereafter and had a major lack of self-confidence. An educational psychologist, by whom I was evaluated at the request of the headmaster of my English boarding school, concluded that any expectation of my gaining a university education was totally unrealistic; successful completion of my high school education was in fact seriously doubted.

I ended up meeting, at a Christian Science church service, an American university professor who was teaching in Germany on a Fulbright Fellowship. This professor wanted to help me. Despite my disastrous high school record, I ended up enrolling in the university where he taught in the United States.

My first-year university grades proved discouraging, but throughout my life my family had relied on Christian Science, despite the fact that it was forbidden by the Nazi regime, and we had experienced many instances of healing and needs being met through prayer. It was at this time, in university, that I gained a serious interest in understanding and relying on Christian Science myself rather than depending on the support of my parents.

Under the guidance of the professor – who was to become my Sunday school teacher – I began to see myself as more than a struggling student trying to master academics. Christian Science explains that each of us, created in God’s image, is wholly spiritual and expresses the infinite qualities of our ever-loving divine Father-Mother, God. So our true nature is the spiritual expression and manifestation of the limitless intelligence and wisdom of God, divine Mind.

As I increasingly gained this understanding of my true, spiritual nature, it was evidenced in my experience. I regularly made the dean’s list and received other academic awards. I also completed my bachelor’s degree requirements in less than the allotted four years, permitting me to start and complete a master’s degree in my chosen discipline.

The comprehensive examination for the master’s degree provided another opportunity to rely on the divine Mind’s guidance. I was dismayed to find that although the examination consisted of four questions, I was only prepared to answer the first one.

I focused on answering that question to the best of my ability. Not knowing what to write for the three additional questions, I silently affirmed the presence of the divine Mind and acknowledged that I, as an expression of this one Mind, reflected infinite dominion – in other words, that God provides us with the ideas and inspiration to do what we rightfully need to.

As I prayed, the ideas flowed, and I busily wrote them on the exam paper. To this day, I am not sure exactly what I wrote; however, weeks later when the exam results were published, I had passed with flying colors. In fact, the grades I received on the final three questions were better than the grade I received on the first question!

No one is a lost cause when it comes to living up to the God-given potential we all have. Day by day, each of us can strive to feel and express more fully the intelligence and wisdom of God, limitless Mind, in our lives.

Adapted from a testimony published in the Feb. 2019 issue of The Christian Science Journal.

A message of love

A feeling of justice, extended

A look ahead

Thank you for accompanying our exploration of the world today. Please come back tomorrow, when we will take a deeper look at our relationship to work. Has it become the new religion, as some have posited?