- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The wow heard round the orchestra

Noelle Swan

Noelle Swan

Welcome to your Daily. Today’s stories explore the rapidly escalating impeachment standoff, the roots of unrest in Iraq, a shift toward far-right politics in Poland, the emergence of states’ rights as a liberal cause, and an effort to hold onto a bastion of French culture.

First, let’s talk about the power of “wow.”

In May, 9-year-old Ronan Mattin defied convention at a concert at Boston Symphony Hall. In a moment of profound silence at the end of Mozart’s “Masonic Funeral Music,” he exclaimed, “Wow!”

Ronan might have been hushed or scolded for violating the rules of decorum in a sacred sanctuary of music. Instead, laughter, then applause broke out for the wonderfully succinct expression of what many of the 2,500 in attendance were feeling.

The Handel and Haydn Society was so charmed by the simple utterance of awe that it made a public call to find the “wow child” and thank him. Last week, Ronan, who’s been diagnosed on the autistic spectrum and is relatively nonverbal, met the conductor, Harry Christophers, and other members of the orchestra during a rehearsal at Symphony Hall.

“I think a lot of times people go to the symphony, and they try to contain themselves and sit still, like maybe the way you felt when you were a kid and you were told to be seen and not heard,” Toby Oft, principal trombonist for the Boston Symphony Orchestra, told WGBH. “The idea that you would go to a concert and participate is something that we need to make space for.”

Here’s to making space for unbridled joy and spontaneous expressions of amazement.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Is US in a constitutional crisis? That may not be most important question.

Whether you call it a constitutional crisis or a partisan impasse, the current deadlock between the White House and Congress is not something envisioned by the Founders. And it may only be resolved at the ballot box.

-

Jessica Mendoza Staff writer

President Donald Trump’s pledge of noncooperation with the impeachment inquiry of the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives may or may not be a “constitutional crisis.” But it is a stark new test of the nation’s founding legal document – perhaps the most important such trial since Richard Nixon declined to turn over the White House tapes. How it’s resolved could reset the balance of power between the executive and legislative branches of government in our polarized political age.

Many experts believe the current standoff between President Trump and the House isn’t something the Constitution per se will be able to resolve.

The Founding Fathers gave Congress what they felt was a powerful means to prevail in a competition between the branches of government – the ability of the House to impeach presidents and the Senate to vote to remove them. But they did not envision a U.S. where the political fault lines would be party versus party, not legislative versus executive. The result: the current mess of inaction and conflicting claims.

“To me the right term is constitutional failure,” says Chris Edelson, an assistant professor of government in the School of Public Affairs at American University. “The system is not working in the way it was intended and designed to work.”

Is US in a constitutional crisis? That may not be most important question.

President Donald Trump’s pledge of non-cooperation with the impeachment inquiry of the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives may or may not be a “constitutional crisis.” But it is a stark new test of the nation’s founding legal document – perhaps the most important such trial since Richard Nixon declined to turn over the White House tapes. How it’s resolved could reset the balance of power between the executive and legislative branches of government in our polarized political age.

This test is only partly a legal matter. It’s also political – an appeal for the support of the “jury” of American voters. President Trump’s combative letter to the House on Tuesday seemed as much directed toward his rally-going base as a serious attempt to argue legal issues with Democratic leaders. If he maintains his popularity among GOP voters, it’s highly unlikely the impeachment process will result in his removal from office.

“Trump has never been the type of president who has tried to appear above the fray, ever. You can make the argument that part of what’s made him successful with Republicans is his willingness to be competitive,” says James Curry, a political science professor at the University of Utah.

Experts who believe the country is in a constitutional crisis argue that the current standoff between Mr. Trump and the House isn’t something the Constitution per se will be able to resolve.

The dispute stems from the fact the president is refusing to provide documents or witness testimony subpoenaed by the House. In his fiery letter to Speaker Nancy Pelosi this week, White House counsel Pat Cipollone argued that the House impeachment inquiry was “illegitimate,” in part because the House had not authorized it with a full vote, presidential attorneys would not be able to question witnesses, and other irregularities.

But House subpoena power is well-established in law. And the Constitution gives the House the power to impeach, and says nothing else on the subject – allowing House leadership to conduct impeachment inquiries under whatever procedures and inquiries they choose.

It’s true they have yet to hold a full vote authorizing an impeachment inquiry, as was conducted prior to investigations of Presidents Nixon and Bill Clinton. But nothing in the law requires them to do so.

Meanwhile, the House is struggling to enforce its constitutional prerogatives. Civil suits intended to force compliance with past subpoenas are wending their way – slowly – through the courts. Any legal action dealing with impeachment subpoenas might not be completed until after the 2020 election.

The Founding Fathers gave Congress what they felt was a powerful means to prevail in a competition between the branches of government – the ability of the House to impeach presidents and the Senate to vote to remove them. But they did not envision a U.S. where the political fault lines would be party versus party, not legislative versus executive. The result: the current mess of inaction and conflicting claims.

“To me the right term is constitutional failure,” says Chris Edelson, an assistant professor of government in the School of Public Affairs at American University. “The reason I say that is because the system is not working in the way it was intended and designed to work. It was designed as a system of checks and balances, where when one branch goes too far, another reins it in.”

The Constitution is not self-executing, adds William Galston, a senior fellow in governance at the Brookings Institution in Washington. Its effectiveness depends on men and women being willing to defend the governmental institutions they belong to, including Congress.

“We’re in a situation now unfortunately where hyperpartisanship leads a lot of people who should be defending Congress to defend the president instead, whatever he does. And this is a real problem for our constitutional order,” Dr. Galston says.

Realistically, the ultimate answer to the current standoff is voting. The American people will have to choose and resolve the issues involved at the ballot box, he says. “I don’t think constitutional mechanisms are enough,” Dr. Galston says.

In the end the nomenclature may not be the most important thing. Calling today’s situation in the U.S. a constitutional “crisis,” or “stress test,” or “normal struggle,” does not tell us anything we don’t already know.

“Nothing as a practical matter changes if we say it is, or is not, a ‘crisis,’” says Marty Lederman, a law professor at Georgetown University Law Center, in an email.

Much will depend on whether Mr. Trump remains adamant about not cooperating with any House subpoena – particularly if courts rule against him.

That could produce something most everyone would recognize as a crisis point.

One possible, maybe even probable, course of action could run like this: The White House is really just trying to slow down the process to lessen its political bite. Meanwhile, Mr. Trump is engaging in his usual bluster. He’ll lose in the courts, and maybe even provide an obstruction count for impeachment in the House.

But at this point, it seems very likely that the president will be impeached. Perhaps he recognizes this. Obstructing the inquiry as he is could help him with the GOP base. And maintaining their support is the key.

“As long as the base stays with him, there will not be 17 GOP senators who will vote to remove – meaning he will survive,” writes David Barker, director of the Center for Congressional and Presidential Studies at American University, in an email.

In Iraq’s protests, a popular cry to reform a broken political system

On the surface, Iraq’s antigovernment protests are about unemployment and corruption. But they expose a much deeper challenge: the dearth of democratic institutions to translate that anger into meaningful reform.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

A week of deadly protests over corruption and unemployment has posed the biggest challenge to Iraq’s political elite since the Islamic State threat in 2017. And the violence is raising a fundamental question: Does Iraq have the leadership and democratic institutions to address citizens’ anger in a substantive way?

Young Iraqis in particular are disillusioned with a weak government and officials who still rule, 16 years after Saddam Hussein’s toppling, through ethnosectarian parties and militias even as they use state funds to satisfy patronage networks.

Iraq expert Renad Mansour notes that elections last year saw the lowest turnout since 2003. And while two-thirds of parliamentary seats changed hands, initial hopes of significant change have gone.

“This [protest] is the only way – they think – that they can have a voice,” he says.

In a recent analysis, Maria Fantappie of the International Crisis Group wrote that appointing technocrats to ministerial posts “marked an attempt to trigger a transition from a dysfunctional political system. Yet technocrats remain dependent on the old political figures. ...

“Iraq is at a crossroads. A sense of hope and a readiness for reform runs parallel to a stubborn belief that a broken system will continue to sputter along.”

In Iraq’s protests, a popular cry to reform a broken political system

The overwhelming display of anger in Iraq over the past week – and the unprecedented violence with which it was met – has shocked many Iraqis, even though its sources are familiar: unemployment, poverty, corruption.

And as Iraqi security forces end their high alert today and the nation begins to take stock, questions are being raised about whether the country has the leadership, willpower, and democratic institutions to translate this powerful expression of citizen anger into meaningful action.

The short answer is “not yet,” analysts say, even though Baghdad itself has experienced relative calm and a renewed sense of security and normalcy since the Islamic State (ISIS) militants were declared defeated in 2017.

But deep underlying problems have sparked the biggest challenge to Iraq’s political elite since then, with street violence leaving some 165 Iraqis dead, by one count, and more than 6,000 wounded.

Widespread anger at a persistent lack of hope in Iraq – fueled by weak government and years of failed, top-down reform – boiled over in Baghdad and Shiite heartland cities of southern Iraq.

The popular outrage was met with lethal live fire and tear gas, as Iraqis on the street, many of them young men who said they had “nothing to lose,” called for fundamental political change.

“People are shocked at what they are seeing and what they are hearing,” says an Iraqi analyst in Baghdad who asked not to be named for security reasons.

Internet blackout

Until an internet blackout, imposed to prevent further organizing and the spread of news and images of the protests, began to be lifted in recent days, “it was very difficult to tell what was going on unless you went there,” he says. “And if you went there, there was obviously a chance you wouldn’t come back. ... But now the images are starting to come out, videos are starting to come out, the numbers, quotes from hospital officials, and people are shocked.”

Roiling the protesters is not only disillusion with the ballot box, but anger at a political elite that still rules through powerful, ethnosectarian parties and militias – some of them backed by Iran – even as they use state funds to satisfy patronage networks.

Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi said there were “no magic solutions” when he offered protesters a 17-point proposal, including handouts for the poor, in his first public statement since the unrest began on Oct. 1. But it is the weakness of Mr. Abdul-Mahdi’s year-old government of technocrats, and its inability to grapple with Iraq’s entrenched issues, that has failed to narrow the gap between the people and the state.

More than 16 years after an American invasion toppled the dictator Saddam Hussein, Iraq is blessed with revenues from an underground ocean of oil. But it has also been bludgeoned by the U.S. occupation, an Al Qaeda-led insurgency, and finally an invasion by ISIS in 2014, all of which crippled institution-building that might have boosted faith in government and even job prospects.

“Nothing has changed,” says the Baghdad analyst. “It’s still the same kleptocracy that we’re in. The frontline services that people experience every day are still as bad as they were several years ago, in some places they’ve got worse.”

He blames inefficiency, corruption, a lack of will, and fiercely competing interests, such that coalition governments are “made up of rivals and enemies ... just empires and fiefdoms, and they’re constantly at each other’s necks, because they are trying to maximize their benefits,” he says. “So, nobody is thinking, ‘Well, how do we do something for the benefit of citizens and of the country?’”

Protesters, most of them drawn from Iraq’s majority Shiite population, have called for the collapse of the regime, which is Shiite dominated. Yet instrumental in protecting the system have been Shiite militias, a collection of mostly Shiite paramilitary units, known as the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), that grew to some 150,000 strong and consolidated their role during the anti-ISIS fight. They have now been largely absorbed into Iraq’s security and political structure.

Straining to be heard

Iraqi security forces apologized for the excessive use of force, and said commanders never ordered lethal tactics, and don’t know the identity of snipers who have played a key role in raising the death toll.

“I spoke to a doctor, and, on the snipers, these are precision shots, aimed precisely at hearts and heads,” says Renad Mansour, an Iraq expert at the Chatham House think tank in London, referring to the cramped and deprived Shiite enclave where one-third of Baghdad’s estimated 8 million residents live.

The prime minister and his aides have no control over security forces, and “no idea which armed groups are behind this, who is doing the killing,” says Mr. Mansour, who was in Baghdad until the eve of the protests.

He notes that elections last year saw the lowest turnout of any vote in Iraq since 2003. And despite the fact that two-thirds of the seats in parliament changed hands, and that a party of the populist cleric Moqtada al-Sadr made impressive gains, initial hopes of significant change have gone.

Iraqis “have given up faith in elections, in parliament, in technocrats, and this [protest] is the only way – they think – that they can have a voice,” says Mr. Mansour.

“And you can see how important this is, by the way that elites are reacting,” he adds. “They learned from Basra [protests] last year that those who want to protect the system, if they kill enough, if they intimidate enough, if they shut off the internet, they could stop the protests. So this equation is now being used, not just in Basra, but in Baghdad and elsewhere.”

The PMF chief Falih al-Fayyadh blamed the unrest on infiltrators working for foreign enemies. “Our response to those who want ill for the country will be clear and precise by the state and its instruments. ... There will be no chance for a coup or rebellion,” he said on Monday.

Actually engaging with citizens

Even as the street protests wind down, the fact that discontent grew to such an extent means it is already “too late” for a quick fix, and that a new cycle of protest is inevitable without strategic efforts at reform, says Maria Fantappie, an Iraq analyst for the International Crisis Group.

“Stop-gap measures will not do much,” Ms. Fantappie told Al Jazeera English. “There is a need for the government to actually engage with a section of what I call the ‘society of demonstrators.’ It is very important to [remember] that not all demonstrators are violent, [many] are well educated, who are usually engaged in civic activism, volunteering.”

She laid out the challenge for Iraq in an analysis published last March, after five months of research in Iraq. Appointing technocrats to ministerial posts, Ms. Fantappie wrote, “marked an attempt to trigger a transition from a dysfunctional political system. Yet technocrats remain dependent on the old political figures who have little interest in reforming a system that serves them.

“In that sense, Iraq is at a crossroads,” she wrote. “A sense of hope and a readiness for reform run parallel to a stubborn belief that a broken system will continue to sputter along.”

So many graduates, so few jobs

But how broken is that system in Iraq? A few numbers tell the story of discontent and explain why it is young Iraqi men manning the burning barricades. Each year, an estimated 700,000 Iraqis become employable in a country that, at most, is producing just 50,000 jobs.

“The majority of those [jobs] are just welfare, repackaged into the form of employment,” says the Baghdad analyst. “You have a factory that needs 200 people to run it, and you have 3,000 people on the payroll. You have security forces numbering 1.25 million, yet you still have a problem when you fight ISIS, because the vast majority of them are not showing up or are assigned desk jobs.”

“There is no denying that a significant proportion of the population is benefiting from the people in power,” says the analyst, referring to patronage networks. But institution-building has been hobbled, he says, first by Iraqi leaders coming from abroad, post-2003, installed by the U.S. and enriching themselves, then by Iraqis themselves: “Due to ignorance, [and] there are lots of tribal and religious hatreds.

“We have had Al Qaeda and ISIS, all of these elements, and it means we haven’t had any breathing space to say, ‘How can we improve our governance, and deal with our issues?’ without constantly looking at the geopolitics of it all,’” says the analyst.

When the right wing is still ‘too socialist’

The dominance of a non-center party changes the scope of what’s appropriate to say. In Poland, the ascent of right-wing Law and Justice is giving space on the country’s political stage to the far-right.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Monika Rębała Correspondent

For many outside observers of Poland’s ruling party, Law and Justice (PiS) seems like it must set the right-wing bounds of the country’s political spectrum. After all, it has overseen a nationalist, conservative shift since it took power in 2015. But a new coalition is hoping to challenge PiS in Poland’s Oct. 13 elections by going even further right – and is setting off alarm bells.

The leadership of the Konfederacja coalition view themselves as true conservatives and saviors of the Catholic Polish nation. They espouse traditional family values, oppose abortion, and reject migration, especially from the Muslim world. And they worry Germany will turn the European Union into a suprastate adhering to the values of liberal elites.

Critics, however, label them neo-Nazis and fascists. Leading figures in the coalition make remarks and adopt positions many consider sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, and anti-Semitic. And observers say their increasing prominence is a result of normalization by PiS.

“Things that would not be heard on television a few years ago are now part of the mainstream,” says Jacek Dzięgielewski, a researcher with the anti-racism Never Again Association. “They are just pushing those boundaries.”

When the right wing is still ‘too socialist’

When Poland goes to the polls this weekend in parliamentary elections, it is the ruling Law and Justice party that challengers will be gunning for. Over the past four years, Law and Justice (PiS) has moved the country rightward by pushing a populist, anti-immigrant, pro-Catholic agenda.

But as far as Poland’s far-right nationalist parties are concerned, PiS hasn’t gone far enough. And so they have formed a coalition –Konfederacja – in the hope of turning their popularity among young voters into parliamentary seats on Oct. 13 – and thus to become the first party to challenge PiS from the right.

“We are mostly nationalists, we remember the etnos [people with a common origin] in our ideas,” says Michał Urbaniak, as he sits in a kebab restaurant in the port city of Gdańsk. Mr. Urbaniak is a regional head of the National Movement party, which is part of Konfederacja. “We decided to be together and to be elected together because it is easier to take at least 5% of voters needed to be in the parliament.”

The leadership of Konfederacja view themselves as true conservatives and saviors of the Catholic Polish nation. They espouse traditional family values, oppose abortion, and reject migration, especially from the Muslim world. And they worry Germany will turn the European Union into a suprastate adhering to the values of liberal elites. While there are some differences of opinions on taxation, social benefits, and the role of women in society, members of the coalition broadly fit the bill of Euroskeptic Christian nationalists.

Critics, however, label them neo-Nazis and fascists. Leading figures in the coalition make remarks and adopt positions many consider sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, and anti-Semitic. And observers say their increasing prominence is a result of normalization of hate speech by PiS.

“Things that would not be heard on television a few years ago are now part of the mainstream,” says Jacek Dzięgielewski, a Gdańsk-based researcher with the anti-racism Never Again Association, pointing to an uptick in hate crimes since PiS came to power in 2015. “They are just pushing those boundaries.”

Patriotism, Catholic values, and low taxes

That same day at Konfederacja’s electoral convention at a hotel in Gdańsk, a procession of men sporting polished shoes and pristine suits took to the podium to vie to be the main face of the new coalition. Their speeches were peppered with praise for the Roman Catholic Church and scathing criticism toward Poland’s ruling party – particularly its generous social spending. Anti-migrant and anti-LGBTQ views were par for the course.

There is still a range of opinion within Konfederacja, says far-right libertarian politician Janusz Korwin-Mikke, who served in the European Parliament from 2014 to 2018. He claims it is not unlike the U.S. Republican Party, bringing together a mix of conservatives, neo-conservatives, paleoconservatives, and libertarians. “Everyone hates everyone but they form a party” brought together by an even greater hatred of socialism, he says. “It is much better for a country to be ruled by a monkey than by socialists.”

Robert Winnicki, the 34-year-old leader of the National Movement, has no more love for PiS. “Today, the current government is more dependent on the United States than the previous one was on Berlin. But not only that, it also falls on the face in front of Tel Aviv and it is a real threat to Polish interests, Polish property, and our money!”

Mr. Winnicki acknowledges the presence of neo-Nazi elements in some Polish nationalist events like the annual celebrations of Poland’s Independence Day marches, but distances himself from their ideology. He says that what separates Polish nationalist groups from both neo-Nazis and the EU is belief in God.

“Why did [mass executions] happen in the Soviet Union? Why did it happen in Nazi Germany?” he asks. “Those were the systems that threw out God and threw out Christian values. Because if the national values go with Christianity, nobody will murder a group because you have different skin color, because you are a different nation. ... That’s the line.”

As Konfederacja leaders presented their views in Gdańsk, dozens of young men fresh out of school and at the start of their careers listened. Their politics didn’t always align with those being advocated by the speakers. While many expressed antipathy for the LGBTQ movement, others disavowed conservative views on the roles of men and women. Patriotism, Catholic values, and the coalition’s promises of low taxes were the primary reasons given for their support.

“Young men will not think about their families as long as the taxes are high,” says first-time voter Mateusz Michalski, who opposes gender quotas in the workplace but has no problem with the gay community. “This is what young people care about – about their work after they graduate and about family.”

“Young people are our base,” says Mr. Winnicki, whose assistants have been drawn from the All-Polish Youth movement and Pride and Modernity, a now outlawed far-right group that was embroiled in the mock celebration of Hitler’s birthday. “They are our foundations. But not everyone who likes something on the internet goes to the elections, that is our problem.”

The All-Polish Youth movement – which has about 1,000 members spread across Poland – is part of the effort to get the vote out for Konfederacja among younger voters. At one of their branches in Warsaw, campaign posters filled several boxes. Spokesman Mateusz Marzoch says the group is trying to “professionalize” its work.

Direct recruitment efforts focus on high schools and universities at the start of the academic year, as well as young men attending patriotic events and marches. Social media is also central to the recruitment drive – although their radical views have gotten them kicked off Facebook twice.

Mr. Marzoch credits the group’s uninterrupted presence on Facebook since 2017 to the appointment of Adam Andruszkiewicz, a former All-Polish Youth leader, as digital deputy affairs minister, and a stronger defense of “freedom of expression” by the government. The group now claims an informal support base of 5,000 people who can be counted on to show up at “happenings” it organizes.

“The more extreme a group is,” warns Mr. Dzięgielewski, the anti-racism researcher, “the more they try to camouflage.”

A creeping threat?

The new prominence of the Polish far-right has worried many that their language and agenda is becoming normalized, at least in part due to PiS’s own rhetoric.

Calls for a mono-ethnic Poland, for example, have replaced outright racists slurs. Equating adherence to the Muslim faith with a risk of terrorist behavior is another hallmark of the Polish far-right world view. Language such as the “Holocaust Corporation” – the notion that the contemporary Jewish community tries to profit from the 20th-century mass killings – betrays anti-Semitic sentiment in the ranks of PiS, Konfederacja, and the All-Polish Youth.

In January, Gdańsk Mayor Paweł Adamowicz, a defender of migrants and the LGBTQ community, was murdered. While the attacker’s motives appeared to be personal rather than ideological, many saw the killing of Mr. Adamowicz as a byproduct of hate speech. Notably, the All-Polish Youth movement had issued a fake “political death certificate” for the pro-European politician, listing the “cause of death” as “liberalism, multiculturalism, and stupidity.”

The Polish far-right is also viewed with alarm by international organizations. The United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination in August called upon Poland to ban many of its existing far-right groups and parties as its constitution requires. And an October 2018 European Parliament resolution on the rise of neo-fascist violence noted a demonstration by the Polish National Radical Camp movement in the southern city of Katowice, where they strung pictures of six members of European Parliament from makeshift gallows. It also objected to the use of fascist symbols and xenophobic banners at demonstrations.

“The far-right is becoming more popular,” says Mr. Dzięgielewski. “We don’t see swastikas but we see the Celtic cross. They try to show themselves as patriots and they are becoming more bold.”

How states’ rights became a liberal environmentalist cause

At the heart of the ongoing feud between California and the Trump administration lies a familiar tug of war over the role of states’ rights. But this time around, the players seem to have switched teams.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Martin Kuz Special correspondent

California, it seems, is at war with the Trump administration.

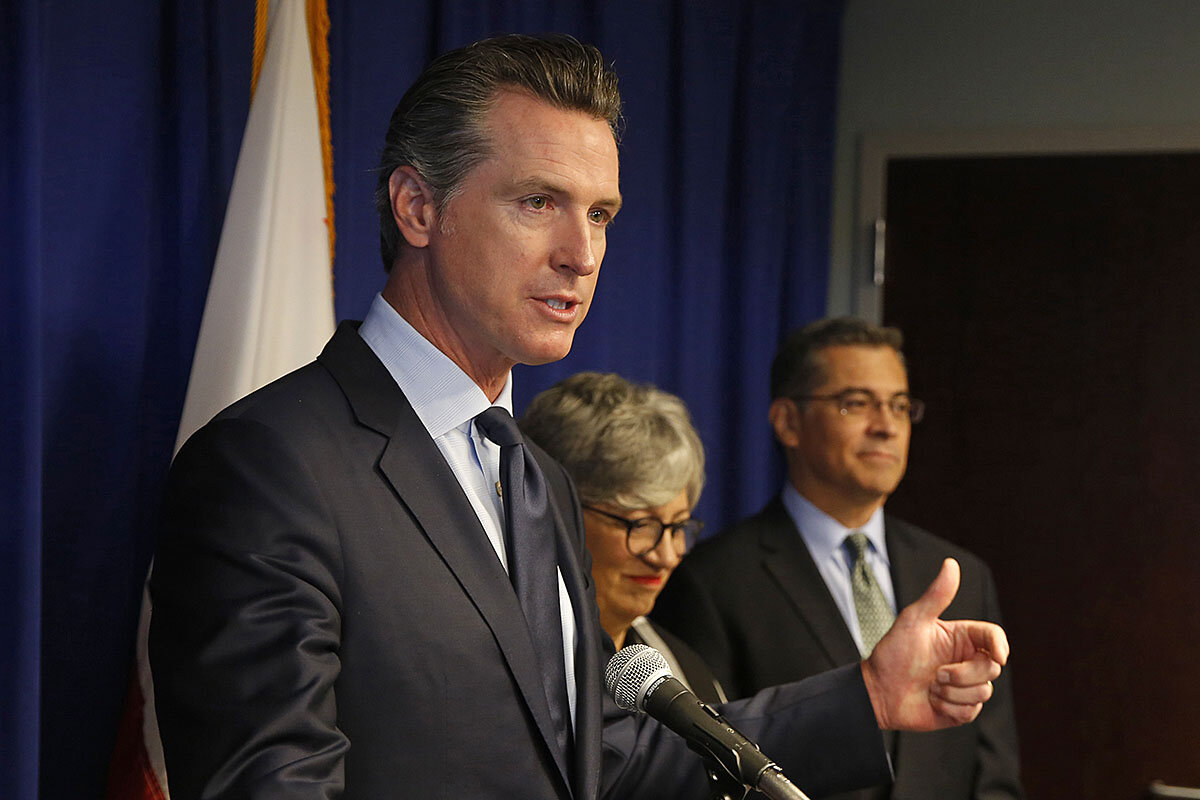

What began as a battle over California’s right to impose fuel emissions regulations has escalated to include accusations that the state has failed to clean up its air and water and threats to withhold federal funds as a result. The latest blow came Friday when the Trump administration announced it was opening up 720,000 acres of federal land in California for oil and gas development. Anticipating that decision, state lawmakers had already crafted legislation to ban development of infrastructure that would be used for oil and gas extraction on protected federal lands. Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom has yet to sign that bill.

Beneath the tit for tat lies a familiar struggle in American politics over the role of states’ rights that many associate with particular partisan battle lines. But both liberals and conservatives have touted federalism when it suits them on some issues, and not on others.

Public policy professor Barry Rabe refers to it as “selective federalism.” “For the party out of power there’s often a kind of discovery of federalism because it gives a greater chance of getting what you want,” he says.

How states’ rights became a liberal environmentalist cause

States’ rights are sacred for many conservatives in the United States.

So how did liberal California become a poster child for states’ rights in its escalating battle with the Trump administration on environmental regulation?

From fuel emissions to oil and gas drilling permits, California is at war with the Trump administration. And at the heart of the feud is the state’s desire to set its own environmental regulations – an issue of states’ rights, and also a continuation of the “cooperative federalist” model that has long been a backbone of American environmental policy. But in this case, as well as in environmental battles being fought in other states, it’s the Republican administration arguing for the supremacy of federal rule.

“They’re exercising what the Western Governors’ Association executive director has called ‘fair-weather federalism,’” says David Hayes, executive director of the State Energy & Environmental Impact Center at New York University School of Law and deputy interior secretary under President Barack Obama. “As long as states do what they want them to do, it’s fine. If they exercise their rights in a way that the feds don’t like because it’s not consistent with their policy, then they’re against it.”

In California, as in some other liberal-leaning states, states’ rights has become a rallying cry. “To those who claim to support states’ rights – don’t trample on ours,” proclaimed California Attorney General Xavier Becerra last month, after the Trump administration revoked the state’s long-standing waiver that allowed it to set its own vehicle emissions.

The idea of states’ rights as a conservative principle is somewhat more nuanced: For decades, both liberals and conservatives have touted federalism when it suits them on some issues, and not on others.

“I often talk about selective federalism,” says Barry Rabe, a public policy professor at the University of Michigan. “For the party out of power there’s often a kind of discovery of federalism because it gives a greater chance of getting what you want.”

But, he notes, in the absence of significant environmental legislation from Congress in the past 30 years, creative engagement between state, federal, and sometimes local authorities has allowed real advances to be made in cleaning up the nation’s air and water. What’s happening now, he says, seems to be dismantling that, and points to a starker division that’s emerged on climate, in particular.

When President Obama issued the Clean Power Plan, 24 state attorneys general immediately filed suit. When the Trump administration removed the Clean Power Plan, 22 states went to court to protest that move. “There is a pattern here, and it shows a real deep divide,” Professor Rabe says. This is “the next step in a process that’s been intensifying for some period of time.”

And the lack of federal action on climate, says Mr. Hayes, has meant that some states have tried to step into the void.

“Traditionally, states’ rights are considered a conservative principle, but it’s the more progressive states now that are showing the way to environmental protection in the climate area in particular, so it’s kind of flipped the script a little bit,” says Mr. Hayes.

Battle over tailpipe emissions

In California, the biggest shot across the bow came last month when the Trump administration announced it was revoking California’s waiver that allows it to set its own auto emissions standards. The state has held this waiver since 1967, when Congress made the exception in recognition of the unusual pollution challenges that California faces. Since 2009, California’s waiver has expanded to include greenhouse gases in its list of pollutants, affecting Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards. That was a more unusual move (and was denied by the Bush administration when the state first made the request in 2007), but several automakers voluntarily joined with California, pledging to raise CAFE standards to nearly 50 mpg by 2026. And 13 other states have joined with California’s stricter tailpipe emissions.

It’s the impact those standards have on the rest of the country that acting Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Andrew Wheeler took issue with.

“To borrow from Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry, CAFE does not stand for California Assumes Federal Empowerment,” Mr. Wheeler said in a September speech to the National Automobile Dealers Association. “We embrace federalism and the role of the states, but federalism does not mean that one state can dictate standards for the nation.”

A week later, Mr. Wheeler sent letters to California officials charging that the state was failing to take enough action to clean up its air and water, and threatening to withhold some federal funds as a result.

And on Friday, the Trump administration announced it was opening up 720,000 acres of federal land in California for oil and gas development. There had previously been a five-year moratorium on leases in the state, following a court ruling that there was insufficient analysis of the environmental impacts of fracking.

Anticipating that decision, state lawmakers have been fighting back.

Assemblyman Al Muratsuchi, a Democrat who represents a Southern California district, authored legislation to ban building any new oil and gas infrastructure on state land that would be used to support oil and natural gas extraction on protected federal lands (which could impact some of the lands being opened for leasing). The bill passed last month, but has yet to be signed by Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom.

“If there’s anything that brings bipartisan outrage in California, it’s when people start messing with our beaches and oceans,” Mr. Muratsuchi says. Last year, he initiated a bill that prohibited the construction of new infrastructure in state coastal waters that would aid federal oil and gas development.

The legislator casts his latest bill as an extension of the state’s ongoing efforts to be a world leader on climate change and renewable energy – even if that means bucking the Trump administration. “We’re not looking for a fight,” Mr. Muratsuchi says. “But if we need to stand up to protect our state, our people, and our beautiful lands, we will.”

A consistent pattern

While California – and the emissions waiver, in particular – is a major example of the federal government breaking with tradition and revoking a state’s power, it’s only one of several, says Mr. Hayes. Also under attack, he says, have been states’ right to approve or disapprove projects based on their water-quality standards, to petition the EPA to take action against upwind states that negatively impact their air quality, and to determine what kind of energy they want, as fossil fuels claim they’re being unfairly pushed out by states that want clean energy.

It’s a consistent enough pattern that last month, the Environmental Council of the States, a nonpartisan association of state environmental agency leaders, sent a letter to Administrator Wheeler raising their concerns. The organization is “seriously concerned,” it stated, about unilateral actions “that run counter to the spirit of cooperative federalism and to the appropriate relationship between the federal government and the states who are delegated the authority to implement federal environmental statutes.”

In California, the threats to revoke federal funding over failing to meet clean air and water standards seemed to some critics like a declaration of war on the state.

“It strikes me as a really special kind of hypocrisy that [Administrator Wheeler] attacks California over its air quality and the problems it’s facing with air pollution a mere week before the administration opens three-quarters of a million acres for oil and gas drilling, which will invariably worsen the air pollution problems we have,” says Clare Lakewood, a senior attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity, one of the groups that sued to get a moratorium on drilling leases in 2013.

And other Californians worry, primarily, about the effect that the federal actions will have on the state.

Several studies in recent years have found that the agricultural region that stretches between San Francisco and Los Angeles has the country’s worst air quality, says Gustavo Aguirre Jr., a county director with the Central California Environmental Justice Network.

“We’re already dealing with bad air and bad water in our area,” he says. “With these policies, we risk making things even worse and undoing the small progress we’ve made in the last 20, 30, 40 years.”

Cafe culture: France fights to keep its fraternité

How important is it for people to have a place to congregate? In France, where the number of iconic cafes is on the decline, patrons and politicians are trying to hold onto a culture that promotes camaraderie.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

French cafes are places where keys get dropped off, issues get debated, and different social classes mingle. But changes to the cafe culture are jolting the country like a strong espresso.

The “Brooklynization” of cafes means more coffee being served in to-go cups, an abundance of co-working spaces popping up, and rural cafes shuttering. In the last half century, the number of iconic French cafes has dropped from approximately 200,000 to 40,000. French President Emmanuel Macron recently approved a 150-million euro ($165 million) rescue plan to save 1,000 cafes in France’s small towns.

Even so, French cafe culture is far from dead. Owners – and French and foreign patrons – desire to keep it alive, even if that means adapting to new ways of operating.

“French cafes are extremely important places to meet others, talk freely, and make connections,” says Josette Halégoi, a psycho-sociologist. “They’ve gone through a major transformation over the years, but still hold a very important place in our collective imagination.”

Cafe culture: France fights to keep its fraternité

Old movie posters, edges fraying, hang unceremoniously on the walls of Café Parisien. The colored tile floor is cracked in places and the bar needs revamping. The Wi-Fi is spotty. But owner Zehor Ouaaz doesn’t plan on renovating.

“There are things we could fix up – the floor, the bar – but we want to keep the spirit of the cafe, its antique feel,” says Mrs. Ouaaz, over a plate of quiche and salad. “It’s part of its charm.”

For 10 years, Mrs. Ouaaz and her husband Reda have owned the Café Parisien in the 19th arrondissement of Paris, in a neighborhood that has become increasingly gentrified. But while the clientele may have changed over the years, Mrs. Ouaaz wants her cafe to remain something consistent in the area.

“We’re a place where people can unwind, enjoy themselves and feel welcome,” says Mrs. Ouaaz. “All types of customers are welcome here … We’re a melting pot.”

French cafes like Café Parisien are more than just a place for a stiff espresso. Customers often use neighborhood cafes to leave their keys with trusted owners, have packages dropped off, or find the name of a local electrician. And in rural areas, the local cafe is often the only place outside work and home to meet and chat, play the lottery, or read the newspaper.

But increasingly, iconic French cafes are changing or dying off. The “Brooklynization” of cafes means more coffee being served in to-go cups, an abundance of co-working spaces popping up, and rural cafes shuttering. In the last half century, the number of cafes has dropped from approximately 200,000 to 40,000, according to France’s largest hospitality union, UMIH. French President Emmanuel Macron recently approved a €150 million euro ($165 million) rescue plan to save 1,000 cafes in France’s small towns.

Cafe closures and new client demands have altered the way cafe owners do business, with some moving toward acceptance of changing habits, and others remaining steadfast in their desire to hold onto the past. Even so, French cafe culture is far from dead. Owners – and French and foreign patrons – desire to keep it alive, even if that means seeing it in a new way.

“French cafes are extremely important places to meet others, talk freely, and make connections,” says Josette Halégoi, a psycho-sociologist and CEO of the Mimèsis International Research Institute in Paris. “They’ve gone through a major transformation over the years, but still hold a very important place in our collective imagination.”

“The life of the neighborhood”

Antoine Palerme sips an espresso as his giant Beauceron shepherd lies comfortably on the floor of Café Parisien. Mr. Palerme has been frequenting the cafe since he moved to the neighborhood in 1979. He used to visit for a night out when he was younger, but now he comes to chat with other regulars and compete with his neighbor on the daily crossword puzzle.

“This place isn’t just a cafe, it’s the life of the neighborhood,” says Mr. Palerme. “If the doors are closed, it means someone has died.”

Mr. Palerme says his choice of cafe is largely dependent on the ambiance here and especially owner Mrs. Ouaaz, who always serves with a smile. Owners play a vital role, serving not only drinks but acting as go-betweens for people in the community who may hail from different social classes, says Ms. Halégoi, the psycho-sociologist.

“Cafe owners speak with clients, put people in touch with others who might need a service, like a plumber,” says Ms. Halégoi. “But new chains, like Starbucks, have no visible owner. You go in, you sit down, and you never make any social connections.”

France has seen a rash of Starbucks-like chains and co-working cafes in recent years, especially in Paris, as the start-up and freelance culture takes hold here. Some spaces charge by the hour or month, offering desk space, coffee, and snacks. But they often come with a hefty price, one that can be prohibitive to freelancers. In Paris, an average daily rate for a co-working space is around €25 ($27), or €400 ($440) per month.

Many turn instead to their local cafes as a way to find community while working – or escape small apartments, or children at home – without breaking the bank. Though they need the business, proprietors have adapted in various ways to the change in culture.

To counter the effect of hours-long squatting, L’Estampe, a cafe facing the massive Buttes Chaumont park, asks customers to buy a drink every hour and leave at noon to make way for lunch-goers. Down the street, Le Pavillon des Canaux, which advertises itself as a “co-office,” allows computers to be opened, but only during certain hours, in order to preserve a convivial cafe ambiance.

Not everyone is happy about it. As one Facebook reviewer wrote, “Today you ask us to turn off our computers. Tomorrow, will you ask us to stop knitting? Using the phone? Reading? We’ve paid for our consumption and we should have the right to do what we want.”

A shift in the countryside, too

Beyond the cities, rural cafes are becoming a dying breed, as small towns battle against economic stagnation and urbanization. More than 25,000 rural communities are currently without a local cafe, reports UMIH.

French nonprofit Groupe SOS is hoping to reverse the trend with its “1,000 cafes” initiative, which since mid-September has called on local mayors of towns of less than 3,500 residents to apply to become one of 1,000 to receive financial aid in order to open, or re-open, their local cafe.

“Little by little, small towns are losing their cafes, along with their schools and other services,” says Jean-Marc Borello, president of Groupe SOS, which had already received 400 applications within the first two weeks of the program’s launch. “This initiative will allow towns to find their footing, to have a decent social life. Cafes are necessary to breathe life into small towns.”

In addition, building more cafes could help dissipate some of the anger and social unrest that stemmed from the Yellow Vest movement, which saw demonstrators protesting across France over regional and social disparities, tax hikes, and unfair wages. Mr. Borello suggests that providing spaces for locals to air their grievances with other members of the community could help prevent them taking to the streets.

“Cafes have always played a very important role in rural areas,” says Monique Eleb, a psychologist and sociologist at the Ecole d’Architecture Paris-Villemin, and author of “Paris, Société de Cafés.” “[Cafes in general] allow for discussion, the free flow of ideas, the mixing of social classes … and in small towns, if the local cafe is gone, it creates a major lack of camaraderie.”

Maintaining the “human quality”

As urban cafe owners attempt to move with the shift that is taking place across France, from the cozy neighborhood bistrot where everyone knows your name to a co-working culture, only a handful have been successful. One of those is Le Café Zephyr, a dimly-lit cafe with an Art Deco vibe, 10 minutes from the Buttes Chaumont park in Paris. While a number of customers studiously tap away at their computers, an equal amount sit with friends reading the newspaper or chatting with the server.

Along with a large swath of French people, some foreigners are also hoping for the survival of cafe culture. Frank Oteri, a New York-based composer and music journalist, says he often seeks out cafes like Zephyr as a meeting place for coworkers or friends. “I like places with character, a history ... places that contain the energies of all the people in them,” he says. “I also love strong coffee.”

Back at Café Parisien, Mrs. Ouaaz is setting out napkins and silverware for the lunch rush. The few people on their computers won’t be asked to leave, but she says she won't be installing more outlets to the wall or adding soy milk to the drinks menu.

“Everyone is welcome here ... but I don’t have the demand for that sort of thing,” she says. ”We really want to maintain the human quality of the cafe.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The borderless power of sports

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

On Thursday, in a Tehran stadium whose name means freedom in Farsi, thousands of Iranian women will get a taste of freedom they have long wished for. For the first time in 40 years, women will be able to attend a soccer match in Iran, the result of a stern demand by FIFA, the governing body of international soccer, on the country’s ruling clerics.

A similar impact of globalized sports is playing out in China after the general manager of the Houston Rockets basketball team tweeted his support of pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong.

China’s reaction was to limit the broadcasts of two preseason NBA games. The league’s commissioner, Adam Silver, at first sought to apologize for the effects of the tweet on many Chinese. But then, under pressure, he finally affirmed a core principle that comes with international sports. “We will protect our employees’ freedom of speech,” Mr. Silver said.

Sports, with its demand for collaboration in the midst of competition, has a way of quietly entering through the back door in a world fraught with high-stakes tensions and risks of war.

The borderless power of sports

On Thursday, in a Tehran stadium whose name means freedom in Farsi, thousands of Iranian women will get a taste of freedom they have long wished for. For the first time in 40 years, women will be able to attend a soccer match in Iran, the result of a stern demand by FIFA, the governing body of international soccer, on the country’s ruling clerics.

Soon after FIFA’s order last month, tickets for women to attend this World Cup match between Iran and Cambodia were sold out. To be sure, the women in Azadi Stadium will be segregated from men. And they will be watched over by 150 female police. Yet the historic event is a good example of how the globalization of sports, from soccer to basketball, is helping people transcend conflicts over religion, race, or national interests. It fulfills a key goal of the Olympic charter: to create “respect for universal fundamental ethical principles.”

A similar impact of globalized sports is playing out in China after Daryl Morey, general manager of the Houston Rockets basketball team, tweeted his support of pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong.

China’s reaction was to limit the broadcasts of two preseason NBA games scheduled to be held in the country. The league’s commissioner, Adam Silver, at first sought to apologize for the effects of the tweet on many Chinese. But then, under pressure, he finally affirmed a core principle that comes with international sports. “We will protect our employees’ freedom of speech,” Mr. Silver said.

China’s cancellation of the broadcasts is unfortunate, he added, “but if that’s the consequences of us adhering to our values, we still feel it’s critically important we adhere to those values.” His confidence in the NBA’s future in China is probably based on the intense interest in basketball among the Chinese. An estimated 300 million Chinese play the sport, or almost the same as the U.S. population.

Sports, with its demand for collaboration in the midst of competition, has a way of quietly entering through the backdoor in a world fraught with high-stakes tensions and risks of war. By its nature, athletics helps nurture both teamwork and the worth of each individual in achieving excellence, regardless of the surrounding politics.

Sports help build bridges. And for women in Iran, that bridge is the right to enter “freedom” stadium and enjoy a game as equals to men.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Feeling God’s certainty in uncertain times

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Tony Lobl

Amid headlines on Brexit, trade wars, continuing Middle East strife, and extreme weather events, certainty can feel like a distant dream. But each of us can open our hearts to God’s unending goodness, which brings practical change for the better.

Feeling God’s certainty in uncertain times

The long-delayed news I’d been waiting for had finally arrived: I didn’t get the job I’d applied for.

I was overjoyed.

On the surface that made no sense. Those were uncertain times: I had nothing in my bank account and no home of my own, and I badly needed to be working and earning.

Beneath the surface, though, something else had been going on. I was finding a new way to think about certainty. I wasn’t enthused about the role I’d applied for, so I’d been praying to know whether I’d made the right decision by even seeking that employment.

That prayer was answered in a sweet sense of reassurance that came to me one evening: that the certainty is in God. To me, this meant I didn’t need to be humanly certain of what was right. I just needed to know that God was certain, and that I could trust that divine certainty.

That doesn’t mean God knows and organizes the details of our lives. Rather, the right solution comes to light as we become conscious of the love of God, our creator. As Deity’s spiritual offspring, expressing all that God, divine Love, is, we have no gaps in our experience of goodness.

Time and again I’d found that perceiving and accepting this spiritual fact brought needed solutions to difficulties. That’s what happened in this case. My joy at the rejection letter sprang from a sure sense that this wasn’t failure, but God’s certainty heralding a better opportunity ahead, which is what soon transpired. I was sought after and hired in a role I hadn’t applied for – one that used and developed skills I’ve loved employing ever since.

I’ve thought about this glimpse of a higher sense of certainty with Brexit, trade wars, continuing Middle East strife, and extreme weather events in the mix of headlines over the past year. Certainty – let alone the certainty of goodness – can feel like a distant dream.

But there’s a legitimacy to confidence in God’s goodness, which is illustrated in an inspiring story of spiritual poise in the face of disruptive change. It’s a Bible account of Gamaliel, a highly respected doctor of the Mosaic law. When members of a Jewish tribunal were bent on killing the early pioneers of Jesus’ teachings, a few words from Gamaliel calmed the sectarian fury and self-righteous certainty. He said: “Let them alone. If this program or this work is merely human, it will fall apart, but if it is of God, there is nothing you can do about it – and you better not be found fighting against God!” (Acts 5:38, 39, Eugene Peterson, “The Message”).

This spiritual sense of certainty is seen in Christian Science, which was discovered by Mary Baker Eddy almost two millennia later. It reveals that God is good, that this spiritual goodness isn’t subject to circumstances, and that Jesus’ record of healing evidenced how an inspired, spiritual discernment of divine goodness brings practical change for the better. As we yield to this spiritual understanding, our material sense of uncertainty gives place to the Christ – the spiritual idea of God’s ceaseless goodness, which impelled Jesus’ words and deeds – in tangible ways. Health displaces sickness; we’re freed from some sin; calm dispels crisis.

As our certainty in God’s goodness grows through such experiences, we lose confidence in flawed human forms of trust: a material rather than spiritual sense of self-reliance, blind faith in religious creeds, or unquestioning confidence in political philosophies. Our true nature exists forever beyond the ebb and flow of material thinking and action, in which fragility is believed to be inevitable, resulting in sickness and sorrow, vulnerability and lack. As God’s creation, we’re actually spiritual and environed solely in God’s spiritual reality.

Discerning the Science of life’s divine reality results “in the proof of healing, – in a sweet and certain sense that God is Love,” as Mrs. Eddy puts it in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” (p. 569). What a profoundly needed sense of certainty!

We’re all able to play a part in lifting the curtain on divine reality already present, already in operation. By accepting and evidencing the continuity of good found in God’s infinite and eternal control, we bring to light the divine security that belongs to all.

Adapted from an editorial published in the March 25, 2019, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Does this fur coat make me look fat?

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow when the Monitor’s Russia correspondent Fred Weir will explore some unexpected effects of a law banning online criticism of the Kremlin.