- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- After six months and a siege, Hong Kong’s front line takes stock

- Where suburban women might matter more than the president

- Tunisia as a hub for LGBTQ rights? Democracy is making it happen.

- Why you should talk about climate change – even if you disagree

- Buddy Holly’s back ... as a touring hologram. But is it ‘live’ music?

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Behind the hot mic headlines, a more harmonious NATO summit

Howard LaFranchi

Howard LaFranchi

For today’s five hand-picked stories: a protester’s-eye view of Hong Kong unrest, the importance of Georgia’s shifting politics, why LGBTQ rights are coming to the surface in Tunisia, the need for difficult conversations on climate change, and how holograms are redefining live music.

You might think, given the brouhaha over the hot mic that caught Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau commiserating with a few European leaders about working with a disrupter U.S. president named Donald Trump, that this week’s NATO leaders meeting in London was every bit as divisive and cacophonous as earlier alliance summits of the Trump era.

But in fact the meeting, meant to mark NATO’s 70th anniversary, was comparatively harmonious and forward-looking – especially given the sense of foreboding that permeated most transatlantic experts’ expectations. “It was a little like spring,” says Alexander Vershbow, a NATO deputy secretary-general during the Obama presidency. “In like a lion, out like a lamb.”

Yes, President Trump abruptly departed London after scrapping a press conference. Still, Mr. Vershbow says the meeting “ended on a very positive note” with “leaders determined to project unity ... and avoid drama.” Very different from last year’s summit in Brussels, he adds, which “ended on a tense note.”

To say the least. I was at the Brussels summit, and I recall the hand-wringing of European officials who worried right up until Air Force One was “wheels up” that President Trump just might pull the United States out of an alliance whose members he lambasted as freeloaders.

This year, he had mostly praise to offer his NATO counterparts for stepped-up defense spending (crediting himself for an upswing that began in 2014). He signed a final declaration that for the first time cites China as a NATO concern and names space as an “operational domain.”

OK, so maybe the political side of the alliance showed some fissures. But that’s hardly new. As seasoned NATO hands like to say, when you’re dealing with 29 democracies, it comes with the territory.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

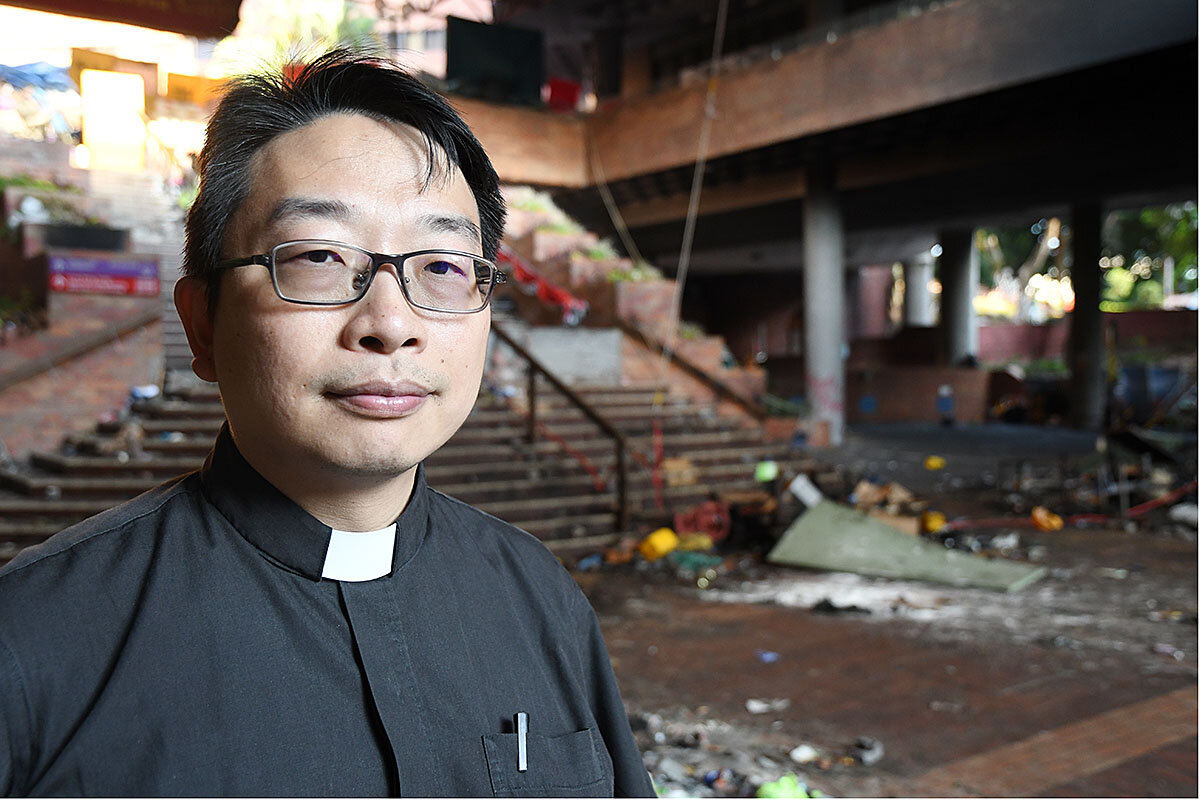

After six months and a siege, Hong Kong’s front line takes stock

What do the Hong Kong protests look like from inside the resistance? Our Ann Scott Tyson went to Hong Kong to burrow into the life of a protester.

What to make of November in Hong Kong? The pro-democracy protests, now six months in, may have faced their toughest moment, with demonstrators facing off against police in a two-week campus siege. Yet the movement also received significant shows of support, from overwhelming wins in local elections, to U.S. legislation aimed at supporting rights in Hong Kong.

Protesters are taking stock – especially the young people who spent time trapped at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, fearful of being arrested and charged with rioting, which could carry a 10-year jail term. Last month brought two challenges, they say: a spike in violence and tactical setbacks that led to internal dissent, and the elections, which some analysts believed could take the wind out of the protests. But so far, crowds have continued to take to the streets.

“We have fantasies about building a new Hong Kong ... where everyone has a deeply rooted faith in their rights and democracy,” says one frontline protester, who escaped campus but says he has survivor’s guilt over peers who were arrested – more than 1,000.

Many feel traumatized, as well. “Every night, I get nightmares,” says one young woman. “Although I escaped from there, I feel like I cannot get away.”

After six months and a siege, Hong Kong’s front line takes stock

With an impish smile and mop-top haircut, the college sophomore pulls up a chair at a backstreet cafe, his boyish looks and mild manners belying his identity as a frontline Hong Kong protester.

Before mass pro-democracy marches began in Hong Kong in June, the student was immersed in social science classes and campus clubs. Today, he is one of the yongmo – Cantonese for “brave militia” – the hardcore protest element that risks the most in head-on clashes with police, battling with Molotov cocktails, bricks, and umbrellas.

“It’s like a war,” he says, using the pseudonym Steve to protect his identity. Toughened by the conflict, Steve and hundreds of others have been wounded physically – and mentally – in their fight for greater democracy and autonomy from China. Consuming most of his time and energy, it’s become a sometimes surreal struggle that is defining him even as it transforms his home city.

Six months into Hong Kong’s pro-democracy campaign, Steve and other activists offer an inside-the-resistance perspective, taking stock of its wins, losses, strengths, and weaknesses after the protests’ tensest chapter yet: a 12-day police siege of a university campus, with demonstrators barricaded inside. Overall, a tumultuous November saw two different challenges, they say: a spike in violence and a tactical setback that led to internal dissent, and a citywide election that some analysts believed could take the wind out of the protests. But so far, sizable numbers of Hong Kongers have continued to take to the streets. Convinced of their cause, Steve and others say the movement has resilience, broad public support, and unity – and won’t let up.

“We cannot lose, and we have nothing to lose” but everything to gain, says Steve. “We have fantasies about building a new Hong Kong … where everyone has a deeply rooted faith in their rights and democracy” and so will defend them against government encroachment, he says.

“Never seemed to stop”

Last month, the leaderless, nimble movement with the mantra “be water” made a costly, if inadvertent, misstep, Steve says. After calling for a general strike, protesters decided to block two main roads to give workers an excuse to stay home. They set up continuous roadblocks on the highway linking the New Territories bordering mainland China to the Kowloon Peninsula, and the cross-harbor tunnel connecting Kowloon and Hong Kong island – each located near a different university. But when protesters used the universities as staging bases, they lost their critical mobility, giving police an opportunity to encircle their fixed position and strike them hard.

Steve was one of hundreds of protesters waging an all-day battle against police from inside The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU) on Nov. 17. Protesters had a steady flow of supplies, both from inside the school and from thousands of ordinary people who brought them food, clothing, tools, and fuel for making Molotov cocktails.

The next day, Nov. 18, Steve says, he joined three attempts to break out of the police blockade – only to be pushed back each time. “They shot so much tear gas, it was so condensed you could basically see nothing,” he says.

Steve was already weak and in significant pain, having been shot twice in the leg with rubber bullets days before, as he took part in a roadblock to divert police from another campus, The Chinese University of Hong Kong – a strategy protesters call hoi faa, or “blooming flower.”

“The friend next to me only had a simple surgical mask,” he says. “He was unable to breathe” and barely made it onto the campus.

“The guy next to him didn’t make it and fell down the stairs,” and was caught by police, he adds.

In all police fired more than 1,000 cans of tear gas and rubber bullets in the battle that day, saying they “used minimum necessary force to disperse protestors.” Protesters hurled bricks and firebombs and shot arrows at the police.

“The gunshots never seemed to stop,” says another protester, part of a scout team, who gave her name as Ms. Z. “I was so panicked and afraid.”

Later that day, Steve found a secret route out through a side building and scrambled up a hillside to a highway. There he was picked up by a “parent car,” one of a fleet of private vehicles driven by supporters who circulate around hot spots and help protesters escape. “Police were already shooting tear gas at the car. I believe I’m one of the last few people to get out that way,” he says.

Police maintained the siege of the university for nearly two weeks, a low point in the movement for Steve. “PolyU was hell,” he says. “I’m the lucky one who got out,” he says, saying he’s haunted by survivor’s guilt over those who were arrested. “We lost many frontline protesters.”

More than 1,000 suspected protesters were detained at the university, raising the total arrested in connection with the demonstrations since June to more than 5,800. Police designated everyone inside the school as suspected rioters – meaning they could face charges that carry a 10-year jail term.

Two battlefronts

Protesters trapped inside – even those who escaped – say they were traumatized by the ordeal. Many felt they were defending their school against police. “Every night, I get nightmares about the experiences in PolyU,” says Ms. Z. “Although I escaped from there, I feel like I cannot get away from the siege. ... I will never forget how desperate it was.”

The police siege was unjustified and “has already resulted in very traumatic psychological problems,” says the Rev. Common Chan of Sen Lok Christian Church, who searched for protesters hiding on campus. His church is offering counseling to the protesters, who were left isolated, he says, after police detained dozens of medics.

Steve says the tactical defeat at PolyU caused some discord within the movement, but fueled even more anger at the police. “People were depressed due to the PolyU failure, but we still didn’t lose the battle, because the government is doing things that can’t be forgiven,” he says.

After the setback at PolyU, protesters strategically stood down, for the first weekend in months, to allow Hong Kong’s local elections to unfold peacefully on Nov. 24. The election produced a landslide victory for pro-democracy candidates, as the “silent majority” claimed by the pro-Beijing establishment weighed in instead on the side of the protesters. The activists received a major boost of international support on Nov. 27 when the United States enacted a law supporting democracy and human rights in Hong Kong.

Some analysts believed the local elections could redirect the movement toward institutions and away from street protests. But despite a huge win for the pro-democracy camp, Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam has not budged on the key remaining protester demands: an independent investigation of police conduct; amnesty for protesters, and dropping their designation as “rioters”; and universal suffrage to elect Hong Kong’s chief executive and all its legislators. Mrs. Lam did meet a major demand in October, by withdrawing the proposed China extradition bill that sparked Hong Kong’s protests last spring.

Instead, Steve says the protesters and the elected pro-democracy officials will push a shared agenda through different channels. “We have divided into two sections, the battle inside the institutions, and the battle outside the institutions,” Steve says. “Both sections support each other and are not in conflict.”

With large and small protests being staged in Hong Kong almost every day, Steve and the other “brave militia” are turning out in force. “I am actually not brave at all,” he says. “But … if I do nothing, who will? If we don’t sacrifice, then what about the people who died?” he asks. “This helps us keep going, toward the winning day.”

Where suburban women might matter more than the president

Ahead of the 2020 election, Georgia shows that suburbs are trending blue, even in the Deep Red South.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

When GOP Gov. Brian Kemp on Wednesday tapped Kelly Loeffler for Georgia’s soon-to-be vacant U.S. Senate seat, it seemed a notable act of rebellion. President Donald Trump and many of his allies had lobbied for the appointment of conservative Rep. Doug Collins, one of the president’s staunchest defenders on impeachment.

Ms. Loeffler, a wealthy businesswoman and prominent GOP fundraiser who hails from the Atlanta suburbs, is a political novice who’d donated a sizable sum to try to elect Mitt Romney to the White House in 2012. Many ardent Trump supporters who helped Governor Kemp beat Lt. Gov. Casey Cagle in the Republican primary last year viewed the pick as a slap in the face.

The appointment comes at a time when the president has been urging Republican unity against the Democratic impeachment push in the House. But it underscores a pressing political reality for Republicans in Georgia and other parts of the South: the need to win back suburban voters – particularly women – who have been moving into the Democratic column, giving certain once-red states a decidedly purple hue.

“Georgia is more competitive than Ohio was in 2016,” says University of Georgia political scientist Charles Bullock III.

Where suburban women might matter more than the president

When Georgia GOP Gov. Brian Kemp began looking for a replacement for Republican Sen. Johnny Isakson, who is resigning for health reasons at the end of the year, Trump allies quickly made their wishes known.

Conservatives such as Fox News’ Sean Hannity and Donald Trump Jr. lobbied openly for the appointment of Rep. Doug Collins, one of the president’s staunchest defenders on impeachment. President Donald Trump himself made the case for Congressman Collins, who represents a rural Republican district in the northeastern part of the state, in a White House meeting with the governor.

So it seemed a notable act of rebellion when Governor Kemp on Wednesday tapped Kelly Loeffler, a wealthy businesswoman and prominent GOP fundraiser who hails from the Atlanta suburbs, for the seat.

The move has come at a time when the president has been urging Republican unity against the Democratic impeachment push in the House. But it underscores a pressing political reality for Republicans in Georgia and other parts of the South: the need to win back suburban voters – particularly women – who have been moving into the Democratic column, giving certain once-red states a decidedly purple hue.

“Georgia is more competitive than Ohio was in 2016,” says University of Georgia political scientist Charles Bullock III. Suburban women “are a group that is in play, and you have to look pretty long and hard to find women in leadership positions in the Republican Party, in elected statewide offices. So this would be a very, very high-profile position being held by a woman.”

The scene of recent Democratic heartbreak, Georgia is likely to be the only state with two U.S. Senate races on the ballot in 2020. The 7th Congressional District, spanning the north Atlanta suburbs, is in play after Rep. Rob Woodall announced his retirement only months after squeaking by with fewer than 1,000 votes. And recent polls suggest that Mr. Trump could face greater head winds in Georgia, a state he won by 5 points in 2016.

“It will be competitive here,” says Emory University political scientist Alan Abramowitz.

Central to Georgia’s purpling are its booming suburbs, from Chatham County on the coast to Gwinnett County northeast of Atlanta. A once-solid Republican enclave, Gwinnett has gone from a clear white majority in the 1980s to majority-minority status today, with white voters now making up 37% of the population.

As the suburbs have diversified, their politics have shifted accordingly. The 6th Congressional District, northwest of Atlanta, was comfortably Republican until 2017, when a special election there became the most expensive House race in history. Last year, the district’s GOP incumbent was defeated by Democrat Lucy McBath, an African American gun-control activist whose son was killed after a dispute over loud music.

“If you look at the compositional change in the South, it’s overwhelmingly favorable to minorities, younger voters, and in-migrants, which is horrible for the GOP,” says Texas Tech political scientist Seth McKee, author of “Republican Ascendancy in Southern U.S. House Elections.”

Last year’s gubernatorial race between Mr. Kemp and Stacey Abrams, an African American lawyer who served as minority leader of Georgia’s House of Representatives, was the closest the state had seen in more than half a century. Ms. Abrams lost by 55,000 votes – but 300,000 new voters have registered since then.

And most of those new voters don’t hail from the country, polling experts point out.

“There’s this big debate about how Democrats don’t win that many counties because they tend to self-sort themselves into urban areas,” says J. Miles Coleman, an associate at Sabato’s Crystal Ball at the University of Virginia, in Charlottesville. “It’s kind of reversed in Georgia and Texas: The Republicans have basically maxed out their share in the rural areas.”

Mr. Kemp appears to be taking those demographic changes seriously.

As a candidate, he ran a Trump-like campaign, posing in ads with a truck and a rifle, and promising to personally deport “criminal illegals.” Directly after taking office, he signed a controversial abortion bill that threatened the state’s booming film industry. (That bill is currently blocked in the courts from taking effect.)

But in the past few months, he has surprised some observers by appointing a number of minorities and women, including three people from the LGBTQ community, to key state positions.

His latest nod to the suburbs comes only weeks after Virginia Democrats took full control of the state legislature there for the first time in more than two decades, while Kentucky voters sent a Democrat to the governor’s mansion, and Louisiana voters returned Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards to Baton Rouge.

Mr. Coleman grew up in New Orleans’ Lakeview neighborhood, the heart of Louisiana’s Republican Party. In 2003, GOP Gov. Bobby Jindal won the neighborhood by a 3-to-1 margin. Last month, Mr. Edwards, a centrist Democrat who opposes abortion rights, carried 58% of the Lakeview vote.

“It’s crazy to me, growing up with these people, that the most Republican parts of [key Southern states] are basically swing regions now,” says Mr. Coleman.

Encouraging for Republicans, a recent Atlanta Journal-Constitution poll found that Mr. Trump has continued to consolidate his base, with 87% of Georgia Republicans feeling favorably toward the president.

But the same poll also found that 60% of right-leaning independents disapprove of Mr. Trump’s job performance.

Ms. Loeffler, a chief executive with the Intercontinental Exchange, which runs the New York Stock Exchange, and co-owner of the Atlanta Dream women’s basketball team, is a political novice but has expressed interest in elected office before. Some Georgia conservatives have worried, given a $750,000 donation to Mitt Romney’s 2012 PAC, that her politics leaned more toward the center than the right.

At a news conference at the state capitol, Mr. Kemp compared her to Ivanka Trump, the president’s daughter, saying both were “smart, accomplished, and savvy.” Both he and Ms. Loeffler underscored their support for Mr. Trump, with Ms. Loeffler pointedly describing herself as “pro-Second Amendment, pro-military, pro-Trump, and pro-wall.”

She also said she plans to spend $20 million of her own money to win next year’s special election for the seat.

Still, for many ardent Trump supporters who helped Mr. Kemp beat Lt. Gov. Casey Cagle in the Republican primary, the Loeffler pick is a slap in the face.

“Kemp is betraying us,” says Debbie Dooley, president of the Atlanta Tea Party, who lives in Gwinnett County. “This is a different time from where we sucked it up and voted for the lesser of two evils. And if you betray and ignore the people who got you elected and think they’ll still be there and vote with you, you are making a tremendous mistake.”

Depending on how deeply such views are held, it could presage a growing divide within the Republican Party throughout the state, one that could have electoral consequences.

“Worst case for Republicans is if Doug Collins or multiple male Republicans also decide to run [against Ms. Loeffler] in the special election next November, and then those who supported the losing Republican ... don’t come back to vote in the general election,” says Mr. Bullock of the University of Georgia. “If you look at history, the point at which Republicans were first making gains in Georgia was because Democrats were so busy fighting among themselves that they allowed the Republicans to slip by. That could happen again with a scenario like this.”

A deeper look

Tunisia as a hub for LGBTQ rights? Democracy is making it happen.

The expansion of freedom in Tunisia after the Arab Spring has created space for the country’s LGBTQ community to feel safer. Now, they’re openly seeking their own freedoms.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Taylor Luck Correspondent

Less than a decade after its popular revolution transformed Tunisia from a closed dictatorship to a hub of democracy and political activism, the country is emerging as a center for LGBTQ rights advocacy in the region. The first openly gay presidential candidate in the Arab world vied for votes here this fall.

Yet the country’s arcane legal code and police tactics make it fall short of an actual haven. After all, same-sex relations are still illegal in Tunisia.

LGBTQ advocates pin their hopes on a central strategy: vigorous activism. There are now five licensed organizations specifically advocating for LGBTQ rights, lobbying politicians, and partnering with other NGOs, lawyers, and the media to raise awareness of the community’s cause.

The face of the new generation of LGBTQ Tunisians who came of age during the 2011 revolution can be seen in Mawjoudin. Arabic for “We Exist,” the organization was built from a Facebook group of fellow LGBTQ-identifying Tunisians sharing their experiences. Its bare office in downtown Tunis is made up of 20-somethings who are bubbling with energy and ideas.

Hana Jemly, a Mawjoudin community manager, says, “We have safe spaces, but now we want the laws to feel safe anywhere.”

Tunisia as a hub for LGBTQ rights? Democracy is making it happen.

An openly gay man running for president. An annual “We Exist” queer film festival. LGBTQ-friendly certification for restaurants and bars. Rights organizations that lobby politicians and advocate in the media.

This isn’t the United States. It’s Tunisia.

Less than a decade after its popular revolution transformed Tunisia from a closed dictatorship to a hub of democracy and political activism, the country is emerging as a center for LGBTQ rights activism in North Africa and the Arab world.

Yet as remarkable as it is to see public LGBTQ activism in this socially conservative region, the country’s arcane legal code and police tactics make it fall short of an actual haven.

Same-sex relations are still illegal in Tunisia, and members of the LGBTQ community who are utilizing Tunisians’ hard-fought freedoms of association, speech, and assembly to abolish these laws still risk arrest.

With Tunisia’s modern, liberal constitution at odds with entrenched conservative social norms and century-old laws, the country’s LGBTQ advocates are pinning their hopes on a central strategy: vigorous activism.

“These LGBT associations have crafted for themselves a space for action, raising awareness, and advocacy in Tunisia, which is very important,” says Amna Guellali, senior Tunisia researcher at Human Rights Watch.

“They have created a vibrant space for the discussion of these issues and [to] normalize the existence of the LGBT community in the country.”

Article 230

During the dictatorship of Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, LGBTQ persons in Tunisia faced a line in the 1913 Penal Code – Article 230 – criminalizing same-sex relations and providing for prison terms of up to three years.

That article is still on the books today, but then, with no nongovernmental organizations or free speech, the LGBTQ community was underground, unseen, and unheard.

“In those days, we had no voice; people had to hide their identities,” says Mounir Baatour, a leading LGBTQ activist who as a lawyer defended Tunisians charged with same-sex relations during the Ben Ali era in the early 2000s.

With the fall of Mr. Ben Ali and his one-party rule in 2011, a burgeoning civil society emerged with organizations representing all causes; LGBTQ rights was no exception.

There are now five licensed organizations specifically advocating for LGBTQ rights, lobbying politicians, and partnering with other NGOs, lawyers, and members of the media to raise awareness of the community’s cause.

Mr. Baatour’s organization, Shams, publishes a monthly magazine and runs an online radio station; a youth-oriented group, Mawjoudin, educates lawmakers and provides community outreach.

Activists hold public protests and organize boycotts of companies and public figures who make homophobic comments or voice support for discrimination.

More visibility, more arrests

Paradoxically, as LGBTQ civil society and public awareness grows, so too have arrests.

In 2018, Tunisian courts handed down 128 convictions of same-sex relations, a 60% increase from the year before and double the average during the Ben Ali era, according to Shams.

Worse still, police and judges – many of whom served under Mr. Ben Ali – confiscate mobile phones for “proof” of homosexual acts. Courts continue to order men to undergo invasive physical exams that have been discredited by forensic experts and denounced by rights advocates and politicians here as “torture.”

These acts and the 1913 laws are in violation of Tunisia’s progressive constitution, but with politicians divided and the constitutional court yet to be established, the policies have so far gone unchallenged legally.

Tunisian NGOs are carrying on the fight.

“We are not like activists in the West; we are not demanding the right to marry or adopt children – we just don’t want to live under the threat of being sent to prison,” Mr. Baatour says.

“We are only defending ourselves, and in terms of human rights, that is the least we can do; to push back.”

Prized image of tolerance

And push back, they have.

With each arrest, LGBTQ rights groups and their partners have alerted the foreign press and lobbied European and North American rights organizations – pressuring a government that prizes Tunisia’s tolerant image and tourism-driven economy.

Activists have put the issue of the penal code and invasive police tactics front and center, making it a litmus test of whether politicians will uphold the constitution and its articles against discrimination, torture, and enshrining the right to privacy.

Article 230 became a talking point on the campaign trail in this year’s presidential elections. And Mr. Baatour threw his own hat in the ring, becoming the first openly gay presidential candidate in the Arab world.

Although ultimately unsuccessful, the veteran lawyer claims victory.

“As the first openly gay presidential candidate in the Arab world, there were over 650 articles written across the world on my candidacy, the LGBT community in Tunisia, and Tunisians being jailed for their sexual identity,” Mr. Baatour says at his office in a leafy Tunis suburb.

“I will run again and again if it means I can bring our cause to the world’s attention,” he says with a sly smile, “and embarrass the government into action.”

Recently elected President Kais Saied, who referred to homosexuals as “deviants” on the campaign trail while courting conservative voters, has since met with LGBTQ organizations to offer them reassurances.

“We exist”

The face of the new generation of LGBTQ Tunisians who came of age during the revolution can be seen in Mawjoudin.

The organization based in a bare office in downtown Tunis is made up of 20-somethings who are bubbling with energy and ideas and have none of the baggage of their predecessors, who lived in fear for decades.

More than just rights, they are pushing for their needs as a healthy and vibrant community.

Arabic for “We Exist,” Mawjoudin was built from a Facebook group of fellow LGBTQ-identifying Tunisians sharing their experiences.

The organization now acts as a support network, lobbying arm, and meeting point for LGBTQ persons to discuss their concerns, share their interests, explore their identities, and provide legal help.

“It has changed a lot since the revolution,” says Hana Jemly, a Mawjoudin community manager. “Having licensed organizations allows us to seek support and partner with lawyers, other NGOs, politicians, the media, and international organizations.”

Mawjoudin is looking to push further.

“We have safe spaces, but now we want the laws to feel safe anywhere,” says Ms. Jemly.

In addition to trainings for politicians, this year Mawjoudin began providing certificates to “LGBTQ-friendly” bars, restaurants, and cafes in the capital, a certification that is given after sensitivity training for staff and that can be revoked.

Last year, Mawjoudin launched an annual Mawjoudin Queer Film Festival celebrating non-Western LGBTQ identities, featuring more than 30 films and documentaries from Tunisia, Kenya, Pakistan, China, and Latin America.

It is the first queer film festival in North Africa and the only one in the Arab world.

Regional epicenter

Civil society has also allowed Tunisia to become a focal point for LGBTQ activism and community outreach in North Africa and the Arab world. International organizations go through Tunisia to access individuals and launch initiatives in the wider region.

And the safe space created by Tunisia’s constitution and licensed organizations has attracted LGBTQ refugees and migrants from across the continent and around the region, including those from Morocco, Algeria, Libya, Egypt, sub-Saharan Africa, and even the Levant, many of whom are fleeing less tolerant societies and threats of violence at home.

People such as Ahmed.

The 30-year-old from Libya came to Tunisia three years ago after he received death threats from a militia because, he believes, of his sexual identity.

“Here you have a support network and a community,” says Ahmed, who declined to use his real name or home town in order to protect his family from reprisals. He says others from North Africa have come to settle in Tunis to live and work, and in some cases, apply for asylum in the West through Tunisian organizations.

“When we have the chance to stand together, not only do you realize that you are not alone, but that we are stronger than we believe.”

Progress

Tunisia’s LGBTQ activists have made significant progress in less than nine years.

No speech or homophobic comment in public goes unchallenged.

In 2018, a government-appointed Individual Freedoms and Equality Committee – tasked by the president to ensure that laws were in line with the post-revolution constitution and its guarantees of equality and personal freedoms – issued recommendations calling for the abolishment of Article 230.

In addition, the committee called for ending century-old laws criminalizing “public indecency” and “public offense to morals” that also have been used to target the LGBTQ community. And it urged a ban on court-ordered physical tests.

A draft law to abolish these laws sits in parliament, and LGBTQ organizations are pressuring the recently elected lawmakers to follow through on the committee’s recommendations.

“We are alert, and we will make sure the world’s eyes are on you,” says Mr. Baatour.

Why you should talk about climate change – even if you disagree

We asked readers how they commit to climate change action. A few surprised us by saying they quit talking to “deniers.” Must the conversation stop when we start butting heads?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

There’s a green elephant in American living rooms. Nearly three-quarters of Americans accept humanity’s role in climate change, but only a third of U.S. residents are talking about it.

This “climate silence,” observers say, is hampering our ability to take the steps needed to keep global warming in check. But across the country, academics, climate advocates, and community leaders are finding ways to keep conversations afloat by harnessing hope, trust, and shared values.

“It has to be a two-way conversation,” says Tina Johnson, former policy director at U.S. Climate Action Network. “If we can’t hear from each other, we’re never going to trust each other enough to believe what [the other is] saying.”

One way to establish trust is to explore shared values. For some, that means reframing the discussion in terms of human health and well-being. For others it means focusing the promise of American innovation.

While Ms. Johnson urges action, she sees hope in difficult discussions: “Being comfortable – and being uncomfortable – in those conversations I think will get us a lot further than just throwing up our hands.”

Why you should talk about climate change – even if you disagree

The majority of Americans accept human-caused climate change as reality. National surveys report 70% of the country thinks this way. The catch: Only 3 in 10 Americans actually talk about climate change.

This “climate silence,” observers say, is hampering our ability to take the steps needed to keep global warming in check at a time when calls from scientists are becoming increasingly urgent. The latest United Nations Emissions Gap Report recommends drastic global action: Cut greenhouse gas emissions by 7.6% every year for the next decade.

This global challenge requires creative thinking and collaboration from as many people as possible, climate experts say. Across the country, academics, climate advocates, and community leaders are finding ways to keep conversations afloat by harnessing hope, trust, and shared values.

Conspiring to convince skeptical friends and family about climate change isn’t the right attitude, says Ed Maibach, director of George Mason University’s Center for Climate Change Communication.

“I don’t try to change their opinion,” he says. Instead, he shares his own concerns about what climate change will mean for communities and the planet.

“A way of approaching these conversations is simply to share what we know and what we feel and why we care,” he says.

Intending to sway minds through these discussions can cause people to become defensive or disengage, says Tina Johnson, former policy director at U.S. Climate Action Network.

“It has to be a two-way conversation,” she says. “If we can’t hear from each other, we’re never going to trust each other enough to believe what [the other is] saying.”

Starting on common ground

One way to establish trust is to explore shared values.

Climate change initially gained traction with environmentalists because it was framed as an environmental challenge. Reframing the discussion in terms of human health and well-being can open the door for people who aren’t inherently interested in the plight of “plants, penguins, and polar bears,” says Dr. Maibach, who partners with Yale University’s Program on Climate Change Communication.

Karin Kirk, a geologist who writes for Yale Climate Connections, inserts another value into climate conversations: patriotism. “There’s a lot of common ground to talk about American innovation, and I think that’s a really easy point to be proud of,” she says, citing a new “hydro battery” energy storage system planned for her home state of Montana.

The conservative American Conservation Coalition also prizes innovation, favoring market-based solutions to the environment and climate change with limited government. While Democrats are most known for supporting climate change action, the organization seeks to engage young conservatives – a group that increasingly supports climate action. Pew Research found young conservatives more prone than older party members to say the government isn’t doing enough to protect the climate – 52% of millennials or younger, compared with 31% of boomers and older.

Quill Robinson, government affairs director for the American Conservation Coalition, works to unearth values that are hard to disagree with.

“Everybody can agree that they want clean air and clean water,” says Mr. Robinson. For years, Republicans thought environmentalists had to sport “Birkenstocks, a tie-dye shirt, and patchouli,” he says, but that image is eroding.

“Some of our biggest allies in Congress are the younger members who represent coastal districts, who are already feeling the impact of climate change,” he says.

“Among young people, it’s less a debate over if climate change is a thing. It’s more and more what do we do about it,” says Mr. Robinson, a millennial himself. “We’ve grown up with the science.”

A range of perspectives

Climate communicators take inspiration from an old marketing adage: Know your audience.

Public opinion on climate change doesn’t split neatly between “believers” and “deniers.” Such stark labels can be divisive by forcing people into artificial categories.

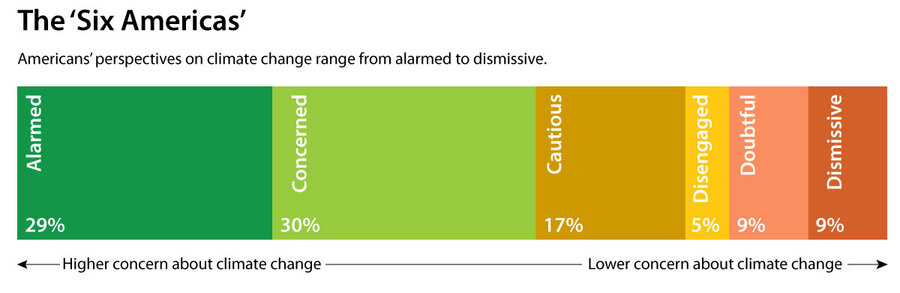

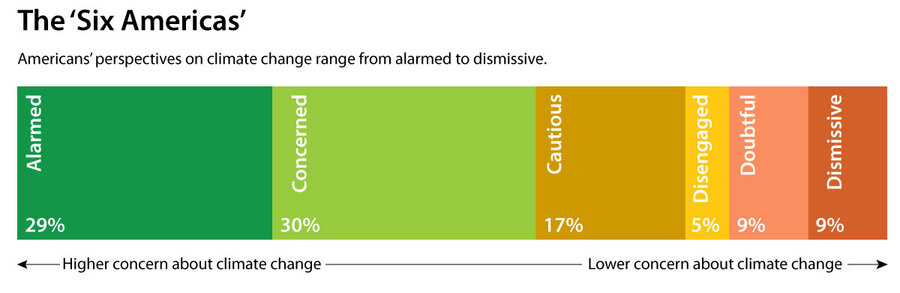

Researchers from Yale and George Mason instead break down the spectrum of U.S. perspectives on humanity’s role in climate change into “Six Americas” – ranging from dismissive (9%) to alarmed (29%, an all-time high). The largest share of the public – 3 out of 10 – are concerned. They see climate change as a serious but distant threat, unlikely to affect them.

Dec. 2018 survey data from Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication

Fostering constructive dialogue across perspectives can be difficult if the two parties don’t already share an established sense of trust. That’s why people who discuss global warming with friends and family – trusted sources – are more prone to learn key facts, like the scientific consensus on climate change, according to Dr. Maibach’s research.

The Rev. Dr. Ambrose Carroll, pastor at The Church by the Side of the Road in Berkeley, California, sees faith leaders as prime facilitators for such discussions since they can be trusted influencers in their communities. The Baptist minister founded the Green The Church movement in 2010 to reclaim environmental justice and sustainability as projects of African American churches.

“We have not seen ourselves as a part of the environmental movement,” he says, “because the history of the movement says that the fauna and the flora ... to some degree, has seemed more important than the lives of African people and people of color.”

His network engages communities of color while recognizing they face other challenges beyond just a changing climate. Through efforts like energy audits and recycling, the campaign links “green theology” with sustainable practices and advocates for political and economic empowerment.

Hope over fear

As observed changes and scientific projections for rising seas and soaring temperatures grow more dire, a sense of empowerment can feel elusive. As a policy consultant, Ms. Johnson has learned that “we have to show where progress is being made, and why it’s being made.”

If you’re talking about renewable technologies like solar panels or wind farms, she says, these ideas must be relatable to your audience.

“Does it save us money? Does it lower our bills? How are we communicating the benefits of this to communities ... so they can start thinking, ‘Oh, I want to be a part of that’?” she says. When Dr. Carroll’s church began recycling, it shaved $4,000 off its yearly refuse bill.

Conversation is also seen as a path toward political action. Dr. Maibach says the most important thing for concerned citizens to do is urge politicians to become climate hawks if they want votes.

“The more that voters make that clear to elected officials,” he says, “the better our chances are of actually making a difference on this problem.”

While Ms. Johnson urges action, she sees hope in difficult discussions: “Being comfortable – and being uncomfortable – in those conversations I think will get us a lot further than just throwing up our hands.”

And being civil doesn’t hurt.

“No angry words,” says Ms. Kirk. “We’ve got 150 years of amazing science on our side.”

Dec. 2018 survey data from Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication

Buddy Holly’s back ... as a touring hologram. But is it ‘live’ music?

Fans want authentic experiences, and artists hope their work survives them. But as technology is now replicating performers, the results push the boundaries of what constitutes live music.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Attendees at a recent Roy Orbison and Buddy Holly concert in Boston happily applaud after each song. Following a rendition of “You Got It,” one person yells out, “I love you, Roy!”

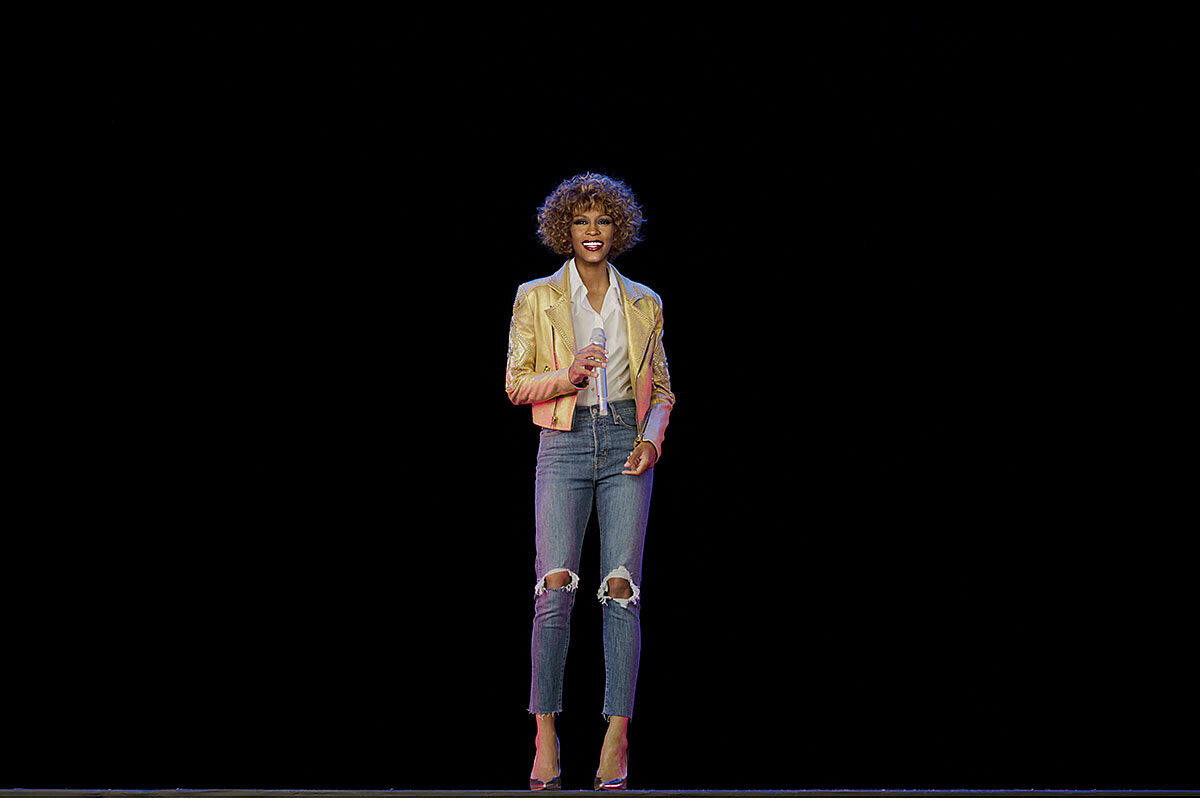

This past year, the phrase “long live rock ’n’ roll” has taken on new meaning as musicians from across genres have been resurrected as touring holograms. A virtual Whitney Houston will join a live band and dancers for arena shows in Europe in 2020. Even ABBA, whose members are still alive, is planning a tour using “Abbatars.”

Amid debate over the ethics of using dead performers’ likenesses without their consent, fans are snapping up tickets to hologram concerts to see if these digital Lazaruses capture the essence of the original artists. Such nostalgia-driven audiences already support veteran bands touring with non-original members and they also feed a booming tribute band business. But this latest offering suggests a growing willingness to support the merge of technology and personhood to re-create a genuine concert experience.

Beth and Gary Thompson, visiting from Halifax, Nova Scotia, looked at each other in surprise when the Boston show first started. “I said, ‘Is it really a person there?’” recalls Ms. Thompson. “It’s so real!”

Buddy Holly’s back ... as a touring hologram. But is it ‘live’ music?

As soon as Donna Kemp heard about a joint comeback tour by Roy Orbison and Buddy Holly, she snapped up tickets at Boston’s Shubert Theatre. The last time she saw Roy Orbison in concert was in 1987. So when the sunglasses-clad crooner appeared in front of a live band on a recent Saturday night, his rendition of “In Dreams” made her tear up – just as it always has.

It didn’t matter that the singers onstage were hologram projections of the two long-deceased artists.

“I was a little apprehensive,” admits Ms. Kemp. “But it’s good.”

Her companion, Larry Donahue, was less convinced by the three-dimensional illusion.

“If there was a person up there dressed up like Roy Orbison and moving around and even lip-syncing, it might be a little more effective,” he says.

This past year, the phrase “long live rock ’n’ roll” has taken on new meaning as artists such as Frank Zappa and Ronnie James Dio have been resurrected as touring holograms. A virtual Whitney Houston will join a live band and dancers for arena shows in Europe in 2020. ABBA, whose members are still alive, is creating a tour consisting of “Abbatars.”

Amid debate over the ethics of using dead performers’ likenesses without their consent, fans are snapping up tickets to hologram concerts to see if these digital Lazaruses capture the essence of the original artists. Such nostalgia-driven audiences already support veteran bands touring with non-original members and they also feed a booming tribute band business. But this latest offering suggests a growing willingness to support the merge of technology and personhood to re-create a genuine concert experience.

“What people are really seeking is as authentic an experience as they could hope for,” says Jem Aswad, senior music editor at Variety. “But also, I think they’re seeking a sense of community, because that’s what you really get from a concert.”

Jockeying to get the tech first

Ever since a surprise hologram of Tupac Shakur made a splash at the 2012 Coachella festival in California, companies such as Eyellusion, Hologram USA, and Base Hologram have spent millions of dollars in a race to develop live-show 3D technology. They believe it’s a growth industry, as a whole generation of classic rock artists won’t be touring for much longer.

“There are artists who I have spoken to who are concerned that they may be forgotten one day and they would like us to preserve them on hologram because it lasts forever,” says Gary Shoefield, executive vice president of content development at Base Hologram, the company behind virtual tours by Roy Orbison and Buddy Holly, Whitney Houston, and opera star Maria Callas.

For the estates of bygone artists, a touring hologram is an effective means to protect artists’ logos under U.S. law because if you don’t use a trademark, you lose it, says Ken Abdo, music lawyer and law partner at Fox Rothschild in Minneapolis. If artists haven’t left specific directions about using their likenesses after they die, he adds, heirs have control over the decision. “Without a directive, then that representative, that heir, is free to do what they want,” he says.

That has left room for the emerging hologram market, which capitalizes on the curiosity of fans. “The commercial success is actually based on the fact that the audience is aware that figure is not real but virtual,” writes Ke Shi, author of “Embodiment and Disembodiment in Live Art: From Grotowski to Hologram,” in an email. “This virtual-ness is the commodity here.”

Mr. Shoefield, from Base Hologram, argues that most people, after a few minutes into a show, “forget it’s a hologram and just enjoy it for what it is.”

Emotional reaction

Holograms can evoke strong emotional reactions among those willing to suspend disbelief. One example: During the 2014 Billboard Music Awards, many audience members were moved to tears by the performance of a Michael Jackson avatar.

“On a deeper level, it is an ancient urge coded in our collective subconsciousness to bring the dead back, a symbolic and theatrical move to defeat death,” says Mr. Shi.

Many touring avatars aren’t pure representations of the performers. Buddy Holly and Roy Orbison were re-created by filming body doubles who mimicked the style of movements of the musicians. The holograms are then projected onto a translucent curtain in front of a live band.

In contrast to the stock-still Roy Orbison, Buddy Holly bops around like an inflatable tube man. Both men dissipate into a puff of smoke at the end – a playful acknowledgment that the whole presentation is just an elaborate illusion.

But can they talk with the audience?

In the future, artificial intelligence technology may offer more interactivity between avatars and concertgoers. But at present the digital representations – which are accompanied by recordings of their voices, either live or studio performances – can only feign interplay by waving at the audience or glancing in the direction of the live band. (Base Hologram is also collaborating with paleontologist Jack Horner on an exhibition of hologram dinosaurs that, mercifully, will feature more bytes than bites.)

The industry is watching to see how hologram tours perform. In Europe, the Whitney Houston tour has been booked for arenas. Ticket sales for the Roy Orbison and Buddy Holly U.S. theater tour, with tickets ranging from $55 to $100, have been solid.

For David Brooks, senior director of the live and touring beat at Billboard magazine, this type of programmed performance “breaks down the whole notion of what makes live music and live entertainment special.”

It’s not just about sharing a moment with a living performer but also about experiencing the element of uncertainty, he says, such as wondering if the musician will be able to hit a high note.

Attendees at the Roy Orbison and Buddy Holly double bill seem less concerned about that, happily applauding after each song. Following a rendition of “You Got It,” one person yells out, “I love you, Roy!”

When the show first started, Beth and Gary Thompson, visiting Boston from Halifax, Nova Scotia, looked at each other in surprise.

“I said, ‘Is it really a person there?’” recalls Ms. Thompson. “It’s so real!”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Where women led in 2019

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

One of the remarkable stories of 2019 has been a string of protests in Muslim countries. Yet just as remarkable was that women not only participated in unprecedented numbers; they often led the crowds.

In Sudan, it was a young student who inspired thousands while singing a popular protest song atop a vehicle. In Lebanon, women led peace marches that changed the character of the protests. In Algeria, a retired judge was one of many women who led months of protests. In Iran, a state-run news publication admitted that the organizing role of women during the protests was “impressive.”

Even if these protests ultimately fail in their political goals, these women have shattered a mental ceiling, not only for themselves but perhaps for others who have been marginalized in their largely Muslim societies.

Where women led in 2019

One of the remarkable stories of 2019 has been a string of protests in Muslim countries. In Iraq, Lebanon, Sudan, and Algeria, the top leaders have had to resign. In Iran, the ruling mullahs had to kill hundreds of demonstrators just to stay in power. None of these countries has yet to achieve most of the reforms demanded by the protesters. Yet the uprisings did bring one breakthrough: In all the protests, women not only participated in unprecedented numbers; they often led the crowds.

In Sudan, it was a young student, Alaa Salah, who inspired thousands while singing a popular protest song atop a vehicle. In Lebanon, women led peace marches that changed the character of the protests and helped curb the violence. In Algeria, a retired judge and civic activist, Zoubida Assoul, was one of many women who led months of protests. In Iran, a state-run news publication admitted that the organizing role of women during the protests was “impressive.”

In many cases, these women had to break social taboos. For some, it was mixing in public with men. For others, it was throwing off a head covering or ignoring the warnings of danger from their families. By being leaders themselves, these women no longer deferred to men. They definitely rejected the notion of being second-class citizens.

“We have traditions, unfortunately, that slightly held people back,” one protester in Iraq told The National newspaper. “But now, women in all the provinces have gone out. Even if a woman doesn’t go out, you see her standing at her door carrying the Iraqi flag. This is the first time that has happened.”

Even if these protests ultimately fail in their political goals, these women have shattered a mental ceiling, not only for themselves but perhaps for others who have been marginalized in their largely Muslim societies.

By being on the front lines, women shaped the nature and direction of the protests. More people felt comfortable to join them, especially by seeing female leadership on social media. Security forces were perhaps less reluctant to resort to violence. And because of the courage of the women and their numbers, top leaders may have felt more pressure to resign.

In Islamic countries outside the Middle East and North Africa, women have been elected as national leaders (Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh). In the Arab world as well as in Iran, perhaps a window has opened in 2019 that could lead to women being democratic leaders.

For the women leading the protests and the ones following them, that equality already exists. They first had to find it within themselves.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Keep your head above the fog

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Kevin Graunke

Even when a problem seems so consuming we can’t see past it, the healing, guiding light of God is always present to lift us out of the fog.

Keep your head above the fog

The brilliant reds and golds of the fall trees shimmered on the lake’s deep blue surface – a perfect morning for fishing! Dad and I happily climbed into the boat and pushed off, but as we headed to our favorite spot the wind shifted. In less than five minutes we were cloaked in fog as thick as the proverbial pea soup. Now the only color all around was gray.

As the dense shroud settled in, we knew that when the wind shifted again and the sun rose higher, the fog would lift. Eventually. But for now, the temporary disorientation of a misty morning on a fishing lake provided a vivid metaphor for contemplating how we respond during those times when a mental shroud of confusion, panic, pain, or grief may roll over us. It can seem as if we just can’t see anything but that “cloud.”

There’s a passage in the Bible that describes this, in a way: “But there went up a mist from the earth, and watered the whole face of the ground” (Genesis 2:6). From there, the book of Genesis goes on to describe a muddled view of creation in which man is described as being made from dust, easily tempted, and ultimately cursed – seemingly trapped forever in the haze of a mortal perspective.

However, the first chapter of Genesis paints a very different picture: Man is clearly defined in relation to God as God’s likeness. The Bible also says that God is Spirit, so all of us as the creation of the Divine must be spiritual, not material. In an explanation of Genesis, Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, wrote: “Immortal and divine Mind presents the idea of God: first, in light; second, in reflection; third, in spiritual and immortal forms of beauty and goodness. But this Mind creates no element nor symbol of discord and decay” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 503).

To me, trying to define from a mortal basis what’s spiritually true is a lot like attempting to navigate a boat in a fog. A misty, mortal view of life obscures what’s really true. It would insist that evil can cause us to run aground at some point.

However, I find in Christ Jesus’ teachings a beacon for steering through mental fog of any kind. He always stood firm, never underestimating the power of divine light to guide and heal. He said, “When he, the Spirit of truth, is come, he will guide you into all truth:… and he will shew you things to come” (John 16:13). His unparalleled healing ministry and example endure today as proofs of the practicality of that guiding divine Spirit – which is still available to all of us, at all times.

Viewing the total “beauty and goodness” of God’s creation in the clear, spiritual light of Christ – the divine perspective of being that Jesus clearly saw and expressed – we discover that whatever would muddle or obscure is not the spiritual reality. Our true nature is always whole and pure. We can stand for beauty, goodness, and light with confidence and fearlessness. And as we come to realize this is our reality, we experience more of those qualities in our lives.

That morning on the water, thinking about some of these ideas, I literally stood up in the boat. As I did, my head emerged above the fog, and I could see everything around us clearly, including the landmarks on the opposite shore near our fishing spot. We turned the boat around, headed over, and enjoyed the morning as the fog lifted and sunlight flooded over us.

We never need to accept some clouded picture of anger, disease, or frustration as legitimate or permanent. These have never been part of God’s universe or our individual place within it. And when we embrace the healing, guiding light of God, divine Love, that reveals what we truly are as God’s children, those clouds begin to dissolve – just like the fog.

A message of love

Nationwide strike

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when our Christa Case Bryant and Patrik Jonsson investigate new evidence of Russia’s attempt to influence American elections. It appears Russia disproportionately targeted African Americans with disinformation in the run-up to 2016 – and is doing so again.