- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- French pension-reform strikes hide deeper issue – distrust of politics

- Is the Iran nuclear deal effectively dead? Three questions.

- 800 million animals, 26 million acres. Australia’s tragedy in numbers.

- Anti-Semitism in the schoolyard: A new front in Germany’s struggle

- California dreamin’: Just how tough is it to buy a home here, anyway?

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The CIA analyst who foresaw democracy’s troubled decade

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Today’s five hand-picked stories touch on what new French strikes say about trust in government, the future of the Iran nuclear deal, the stunning scope of the Australian wildfires, a crucial step in rooting out German anti-Semitism, and a firsthand glimpse of homebuying in California.

In all likelihood, you’ve never heard of Martin Gurri. I hadn’t until I read a recent interview in Vox. Mr. Gurri is a former CIA analyst who predicted the current state of political turmoil in his 2014 book, “Revolt of the Republic.”

His insights are fascinating. The very abridged summary is: Democracy worked better in the recent past because governments could largely control narratives. Essentially, governments could tell voters what was right and wrong, and voters would mostly go along.

Well, that’s clearly out the window in this new era of information, and so voters are unifying only around what they reject: elites, “the system,” the “status quo.” Unifying around these vague negations – rather than a positive vision – is not ideal, Mr. Gurri says.

Yet turn back the clock 500 years, and there’s a useful comparison. Much has been written recently about how profoundly Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press disrupted religion, politics, and society, spawning the Reformation and, centuries later, the Enlightenment and modern democracy.

Today, you could argue we’re going through Gutenberg 2.0. And it’s perhaps less important to try to guess where all this is going than to recognize that, for all the bad and good brought by the first information revolution, the balance clearly tips toward the latter.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

French pension-reform strikes hide deeper issue – distrust of politics

Surely in big-government France, people must have faith in their politicians, right? The protests racking the country offer a clear “no.” Few trust the government to reform the generous pension system.

With hundreds of thousands of protesters taking to the streets of France today, the government has an immediate problem on its hands: how to persuade a skeptical public that its pension reform plans are not only necessary but equitable.

The authorities face a deeper difficulty, though. Behind the strong public support for transport workers who are striking to block the reform lies a widespread sense of mistrust for politicians and all their works.

Suspicious of elites, voters in many countries have elected fresh faces recently, from Donald Trump to Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil. But the levels of distrust in France are startling: only 9% of the French have any faith in their political parties and 73% have little or no trust in their elected representatives.

Sick and tired of the establishment, many French voters are simply throwing up their hands in disgust and saying no to anything that any politician proposes.

Says Pascal Perrineau, a prominent political analyst, “We are reaching a point where the level of distrust is making it very difficult for the government to govern.”

French pension-reform strikes hide deeper issue – distrust of politics

As hundreds of thousands of striking workers and their supporters took to the streets of France Thursday, demonstrating against government plans to reform the pension system, the authorities faced an even deeper problem.

Behind the protests lies a wholesale disgust with politics and politicians that bodes ill for French democracy.

Railway workers nationwide and public transport workers in the capital, Paris, have been on strike for five weeks to block President Emmanuel Macron’s pension reform plans. The longest such strike in 50 years has made life a misery for commuters and travelers, and polls have found three quarters of the population agreeing that France’s complex and deficit-ridden pension system needs reforming.

Yet public support for the strikers’ battle to defend one of the most generous pension systems in the world remains strong. According to a poll published Sunday, 44% support or sympathize with the strike, outweighing the 37% who are opposed or hostile to it.

“Support for the strikes is astonishingly high, considering the inconvenience they are causing,” says Bruno Cautrès, who directs the annual Political Trust Barometer published by Cevipof, a Paris-based think tank. “That’s because there is a high level of social anxiety in the country that Macron has not calmed.”

The government has in fact fed that anxiety, some observers say, by failing to set out clearly how different citizens’ pensions would be affected by the proposed reform.

“Mistrust is at the heart of this movement,” says Pascal Perrineau, a leading political analyst. “People are saying ‘no’ to everything. We are reaching a point where the level of distrust is making it very difficult for the government to govern.”

A system in under strain

Pensions in France are high by international standards. The government devotes 14.3% of GDP to pension payouts, more than any other developed country aside from Italy and Greece and twice as much as in the United States.

A recent independent report, however, predicted that the system could be running an annual deficit of $19 billion by 2025 because demographic changes mean fewer workers are paying contributions and more retirees are drawing benefits.

The system is also complicated, incorporating 42 different pension funds with widely differing rules for different professions and a number of “special regimes” for particular categories of work regarded as especially hard. Railway engine drivers, for example, can retire at 52 with a pension worth 75% of their last salary, although the official retirement age is 62.

The government is planning to introduce a single state-run system, which it says would be fairer, and to encourage people to work a year or two longer so as to balance the books. President Macron vowed to “carry the reform through to the end” in his New Year address to the nation.

But the ham-fisted job the government has made of explaining the reform has fed fears of subterfuge and accusations that its hidden purpose is simply to make people work longer for a smaller pension.

“All the polls show that the French have very deep questions and worries about this reform,” says Dr. Cautrès.

And their worries are broader, suggests Professor Perrineau, one of five public figures invited by President Macron to oversee a “great debate” last year designed to let citizens express their frustrations and their opinions. As President Macron has sought to modernize the country’s economy, “people see what reforms take away from them, but not what they might bring,” Professor Perrineau says.

Some of that attitude is revealed in explanations given for strike funds launched by unions and private citizens. At Christmas, a group of actors, writers, and intellectuals called for contributions to support strikers “defending one of our common goods, a pension system ... that is the fruit of our elders’ struggles.” Such drives are reported to have garnered nearly $2 million.

At the same time, Professor Perrineau adds, “The French make it clear what they reject – the technocratic style of an arrogant administration. But it’s hard to see what they propose as an alternative. It is the politicization of the negative.”

A gap in trust

Underlying that attitude is a deep mistrust of the establishment, revealed in the annual Political Trust Barometer. Last year’s survey found that 73% of the French had little or no trust in their elected representatives in parliament, and that 70% do not believe French democracy is working well.

Only 27% put any faith in trade unions, and a paltry 9% trust the country’s political parties. Those kinds of numbers explain why the Economist Intelligence Unit last year ranked the quality of democracy in France only 16th among 20 Western European nations.

This year’s barometer, due to be published later this month, will find trust levels falling even further, predicts Dr. Cautrès. “I see nothing that would change the trend.”

The weakness of such intermediary bodies as trade unions (only 11% of French workers are unionized, scarcely more than in the United States) dates back to the French revolution, whose ban on guilds and professional associations remains “subconsciously in the French mind” even though it was lifted in the late 19th century, and unions flourished after World War II, says Professor Perrineau.

Political parties have fallen in the public estimation more recently, he says. Having elected a right-wing president in Nicolas Sarkozy, a left-wing one in François Hollande and a “neither-left-nor-right” candidate at the head of a brand new party in Emmanuel Macron, “voters have not seen their situation improve,” says Professor Perrineau. “So they are angry, and they just reject everything.”

On a continent where dissatisfaction with traditional elites is widespread, France could be the canary in the coal mine, he warns. “Unless our political leaders can make sense of the changes that globalization has brought,” he says, “they are going to be in very deep trouble.”

The Explainer

Is the Iran nuclear deal effectively dead? Three questions.

Escalating tensions between the U.S. and Iran have put renewed focus on what remains of the Iran nuclear deal – and what, if anything, might ultimately replace it.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

The Iran nuclear agreement, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), took effect in January 2016. Negotiated between Iran and the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council – China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States – plus Germany, the deal imposed restrictions on Iran’s civilian nuclear enrichment program in return for relief from nuclear-related economic sanctions.

Now the agreement appears to be falling apart. President Donald Trump withdrew the U.S. from the JCPOA in May 2018, saying that, among other things, it did not deal with Iran’s role in regional conflicts or the Iranian ballistic missile program. On Jan. 5, Iran all but abandoned the deal itself.

“Iran’s nuclear program will have no limitations in production, including enrichment capacity,” said the Iranian government in a statement.

On Wednesday, President Trump called on the relevant parties to “break away from the remnants of the Iran deal,” and “all work together toward making a deal with Iran that makes the world a safer and more peaceful place.” Here are three questions about the deal and what might happen next.

Is the Iran nuclear deal effectively dead? Three questions.

The Iran nuclear agreement, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), took effect in January 2016. Negotiated between Iran and the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council – China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States – plus Germany, the deal imposed restrictions on Iran’s civilian nuclear enrichment program in return for relief from nuclear-related economic sanctions.

Now the agreement appears to be falling apart. President Donald Trump withdrew the U.S. from the JCPOA in May 2018, saying that among other things it did not deal with Iran’s role in regional conflicts or the Iranian ballistic missile program. On Jan. 5, Iran all but abandoned the deal itself.

“Iran’s nuclear program will have no limitations in production, including enrichment capacity,” said the Iranian government in a statement.

On Wednesday, President Trump called on the relevant parties to “break away from the remnants of the Iran deal,” and “all work together toward making a deal with Iran that makes the world a safer and more peaceful place.” Here are three questions about the deal and what might happen next.

What was the Iran deal supposed to do?

In negotiating the agreement, the administration of President Barack Obama said its aim was to increase Iran’s “breakout time” to one year. That means that if the Iranians decided to race and produce enough fissile material to build a nuclear weapon, it would take them a year, up from just a few weeks.

To accomplish that, the deal imposed limits on enriched uranium stockpiles and enrichment activities at Iran’s Fordow and Natanz sites. Specifically, it limited the number and type of centrifuges the Iranians can operate. Centrifuges are tall, thin metal tubes that spin at fantastic rates of speed, creating G-forces that separate isotopes of uranium gas and allow concentration of the U-235 isotope.

Uranium used in power plants is enriched to 5% U-235. Medical and research applications use 20% enriched material. Nuclear weapons require 90% enrichment.

The agreement also required Iran to render the core of its heavy water reactor at Arak inoperable. This type of reactor produces a plutonium byproduct that can be reprocessed into weapons-grade material.

In return for these actions, the U.S., European Union, and United Nations pledged in the agreement to lift all economic sanctions imposed on Iran as punishment for its previous nuclear activities.

Why is the deal in trouble?

Candidate Donald Trump proclaimed the Iran agreement a “terrible deal” during his run for the presidency. He objected that it placed no curbs on Iran’s wider military activities, and that it was time-limited, as its major restrictions expired after 15 years. President Trump unilaterally pulled the U.S. out of the agreement in 2018, and reimposed economic sanctions meant to isolate Iran from financial markets and end its oil exports.

Iran said the withdrawal amounted to the U.S. reneging on its agreements. Some countries continued to import Iranian oil under waivers granted by the Trump administration, but the U.S. ended the waiver program in 2019. France, Germany, and the U.K., eager to keep Iran in the nuclear deal, began a barter system to allow transactions with Iran outside the American banking system, but it dealt only with essentials such as food and medicine.

Under this pressure, Iran said it would no longer be bound by the JCPOA. In July 2019, Iran exceeded limits set on its low-enriched uranium stocks. Since then, it has started to enrich some uranium to medical research levels and installed a small number of advanced centrifuge models, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

In this context, Iran’s Jan. 5 announcement simply affirmed what was already clear. Iran said that, as far as it was concerned, it no longer faced any “operational restrictions” and that future actions would depend solely on Iran’s “technical needs.”

What happens now?

Iran has not yet completely withdrawn from the JCPOA. Notably, Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif said Iran would continue to cooperate with inspectors from the IAEA, the U.N. arm charged with on-site verification of the nuclear deal.

That means the world will continue to periodically receive IAEA reports of Iran’s overt nuclear enrichment activities, including measures of enrichment levels and stockpile growth.

Whether the U.S., Iran, and other partners will resume nuclear negotiations, aiming for a broader deal that settles the Trump administration’s stated concerns about missile development and regional meddling, is much less certain. To this point, the U.S. policy of so-called maximum pressure has not brought Tehran back to the table, even though Iran’s economy contracted by 9.5% in 2019, unemployment has spiked, and protests have roiled Iranian cities.

Meanwhile, uncertainty as to Iran’s nuclear intentions will grow. In November, the IAEA reported that Iran now has 372 kilograms of uranium enriched to 5% U-235. If the country begins to produce five kilograms of such material each day – a production level Iranian nuclear officials say is possible – it could reach 1,050 kilograms in about four months. That amount of 5% enriched uranium when enriched to 90% is enough for a nuclear weapon, according to the Arms Control Association.

Iran has not said whether it plans to begin enriching to the 20% level, inching upward in enrichment escalation. But the U.S. may soon face a situation where it is unsure whether the Iranian “breakout time” to becoming a nuclear power is measured in months, rather than the year envisioned in the JCPOA.

To read the rest of the Monitor’s coverage of the U.S.-Iran clash, please click here.

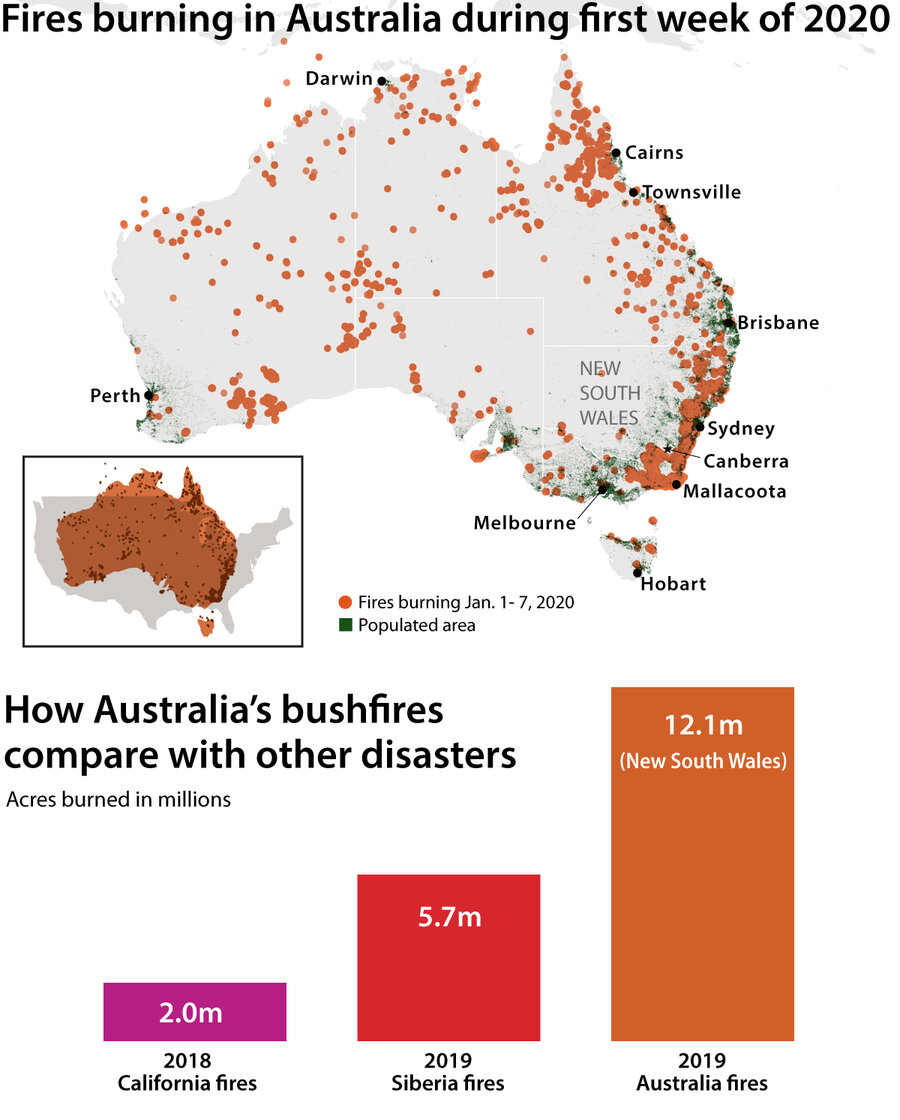

800 million animals, 26 million acres. Australia’s tragedy in numbers.

The scope of any disaster can be difficult to grasp from afar. But the numbers out of Australia are particularly jarring. Our graphics team helps bring them into focus.

The scale is almost too big to fathom.

More than 26 million acres of Australia have burned since the wildfire season began. That’s more than 10 times the size of the 2018 California fires. The human cost has been severe, with at least 27 lives lost and some 2,000 houses destroyed.

But experts say the level of ecological destruction underway is unprecedented. Grasslands and eucalyptus forests have burned, which is not uncommon, but so have some alpine areas and rainforests. And such huge tracts of habitat disappearing have many concerned for the rich wildlife in Australia, which has a high portion of animals found nowhere else in the world and already has the highest rate of extinction for any region.

Chris Dickman, an ecologist at the University of Sydney, estimates that more than 800 million mammals, reptiles, and birds have been killed directly or indirectly in New South Wales. The World Wide Fund for Nature estimates that up to 1.25 billion animals have been lost overall on the continent, including up to 30% of all koalas.

“The fires have been devastating for Australia’s wildlife and wild places, as massive areas of native bushland, forests and parks have been scorched,” says Stuart Blanch of WWF-Australia, in written comments. He’s concerned about the impact of habitat loss on already endangered species like the Kangaroo Island dunnart, the long-footed potoroo, and the regent honeyeater. “Some species may have tipped over the brink of extinction,” Dr. Blanch adds. “Until the fires subside, the full extent of damage will remain unknown.” – Amanda Paulson, Staff writer

NASA Earth Data - MODIS, The Guardian via Rural Fire service, CalFire, Australian Bureau of Statistics

Anti-Semitism in the schoolyard: A new front in Germany’s struggle

As anti-Semitic incidents increase across Germany, they have also been increasing in an area activists say is critically important to any progress: schools.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Lenora Chu Correspondent

Anti-Semitic incidents in Germany have been on the upswing in recent years. Activists say that to fight anti-Semitism, it must be rooted out at an early age. Schools in Berlin have seen an uptick in incidents, reporting 41 incidents in 2018, up one-third from the previous year. That means, activists say, that ground zero must be in schoolyards and classrooms.

But the struggle against anti-Semitism is an issue that’s “massively complex,” says Levi Salomon, lead spokesman for Jewish Forum for Democracy and Against Anti-Semitism. “Anti-Semitism is the oldest form of group-targeted hatred. ... Teachers are hesitant and unclear how to deal with that history.”

On top of that, teachers are overwhelmed and overworked in the face of a massive educator shortage, says Heinz-Peter Meidinger, president of Germany’s largest teachers association. Further, reporting an anti-Semitic incident is not universally required, and administrators’ instincts might be to keep the issues quiet. “For example, if a student does the Hitler greeting, school management is often afraid of reporting because they think, ‘If this reaches the outside world, we’re ruined,’” he says.

Sigmount Königsberg, the commissioner against anti-Semitism for the Jewish community in Berlin, thinks there’s reason to hope. “When I call the schools now, I get an appointment,” he says. “Last year, they ignored me.”

Anti-Semitism in the schoolyard: A new front in Germany’s struggle

The security at the New Synagogue, located in Berlin’s city center, is regrettably familiar in Germany.

The approach is well protected: A chain-link barrier keeps vehicles at a distance, two guards flank the main entrance, and a metal detector arcs over visitors’ heads. It takes about five minutes to get through.

“In the U.S. you can go into a synagogue without any kind of controls,” says Sigmount Königsberg, the commissioner against anti-Semitism for the Jewish community in Berlin. His office is housed within the synagogue. “In Germany, we hardly remember a time like this. Even when I was 10, growing up in the 1970s, there was always a police officer standing in front of the synagogue.”

Such security remains critically necessary, as anti-Semitic incidents in Germany are on the upswing. A shooting outside a synagogue in Halle captured global attention in October, but the gunman couldn’t foil security measures to enter. Metal detectors also stand at the entrance to Jewish kindergartens, primary and secondary schools, and homes for senior citizens.

But Mr. Königsberg and other activists warn that though such measures are still needed, to root out anti-Semitism it must be fought someplace where it cannot be physically blocked: in schoolyards and classrooms. To stop an anti-Semitic hate that seems at once more aggressive and also more subtle, they say, it needs to be addressed at an early age. And that means ground zero must be schools.

“Nine of 10 children are in public schools,” Mr. Königsberg says. “You can start there.” Yet efforts to date are underfunded and a bit random; more systemic action is needed, he says.

Anti-Semitism in the schoolyard

Society-wide, the numbers around anti-Semitism are stark. Six of 10 Jews in Germany have experienced anti-Semitic “hidden insinuations,” while 9 of 10 Jews in Germany feel “strongly burdened” by anti-Semitism directed at their family, according to a 2017 qualitative study out of Bielefeld University titled “Jewish Perspectives on Antisemitism in Germany.”

Schools in Berlin have seen an uptick in incidents, reporting 41 incidents in 2018, up one-third from the previous year, according to RIAS, a monitoring agency that tracks anti-Semitic incidents.

Recently, at one Berlin public school, Mr. Königsberg says, a teacher was instructing a unit on religion. One boy offered up that he was Jewish, only to hear a classmate mutter in response, “I’ve got to kill you.” The teacher heard the remark, but did nothing to intervene, says Mr. Königsberg.

Other school situations can be understated or offhand, and even perpetrated by teachers, he adds. Take the time a Berlin public school took a field trip to the city’s Holocaust memorial. A 14-year-old Jewish girl, emotional over what she was seeing, began to sob. Her German teacher told her, “Why are you crying? It was so long ago.”

“There is no typical story, no typical solution,” says Mr. Königsberg. “Sometimes I need a lawyer, and other times I need a psychologist.”

Other times, one might need the police. A Jewish woman whose child attends an elite Berlin public school says she volunteered to run the Israel booth at the school’s international fair. She says she immediately felt uncomfortable. First, a child of about 5 years passed by and told her, “Israel is bad.” Later, as students assessed the falafel offered at the booth, several offered that the food had “nothing to do with Israel.”

Toward the end of the fair, a teenager leaned over the table to get in her face, snarling, “I wish the falafel were grenades, and that they would explode in your face.” Another parent intervened and moved the teen away from the table.

The woman visited with police over the verbal assault, but ultimately decided not to file a report. “I didn’t feel a 15-year-old should have a criminal record,” she says.

When she reported the incident to the school principal, she came away disappointed. “The issue was never raised with the community,” says the woman, who wished to remain anonymous since her child is still enrolled in the school. “Eventually the principal left. Nothing was done.”

That incident brings up the question: Where is the anti-Semitism coming from? Reporting around incidents doesn’t often include the background of the perpetrator, so good data is unavailable, says Mr. Königsberg. Yet, while it’s clear that some problems stem from increasing immigration from the Middle East, a greater hostility originates inside Germany’s increasingly vocal far-right, exemplified by the Halle shooting. The far-right is hostile to both Muslims and Jews, says Mr. Königsberg, and it’s important to tackle both. “People need to learn to accept minorities.”

Teaching teachers how to respond

Doing nothing is easiest in the face of an issue that’s “massively complex,” says Levi Salomon, lead spokesman for a lobbying group called Jewish Forum for Democracy and Against Anti-Semitism. “Anti-Semitism is the oldest form of group-targeted hatred, and 2,000-year-old stereotypes are archived in European memory. Teachers are hesitant and unclear how to deal with that history.”

On top of that, teachers are overwhelmed and overworked in the face of a massive educator shortage, says Heinz-Peter Meidinger, president of Deutscher Lehrerverband, Germany’s largest teachers association. In other words, even if there were a nationalized curriculum for addressing the issue of prejudice, there’s little time to implement it.

There are also institutional problems: Reporting an anti-Semitic incident is not universally required. “Teachers should be required to report,” Mr. Meidinger says. “I also wish that every German state appointed an independent contact person in the school ministry to take reports.”

Administrators’ instincts also might be to keep the issues quiet. “For example, if a student does the Hitler greeting, school management is often afraid of reporting because they think, ‘If this reaches the outside world, we’re ruined,’” says Mr. Meidinger.

Other times, educators who are sensitive to the issue feel isolated or alone, found a 2017 survey of anti-Semitism in schools out of Frankfurt University of Applied Sciences.

The German government has implemented a number of measures against anti-Semitism broadly in society. For example, denial that Jews were murdered during the Holocaust is a crime, as is the display of a swastika. Golden Stolpersteine, concrete cubes with inscribed brass plates, are displayed at thresholds to commemorate victims of the Holocaust.

Regarding schools specifically, anti-Semitism has been introduced as a category of discrimination in the emergency response plans for schools in Berlin and two other states. This requires administrators to report any incidents to a government office starting the 2019-20 academic year. Politicians in other German states are considering following suit.

Yet the people working on this issue feel that much more awareness around anti-Semitism and structural change inside the education system is needed. “We’re hoping for a continuous conversation, rather than one-off approaches around single incidents,” says Marina Chernivsky, head of the Competence Center for Prevention and Empowerment. Her organization is focused on bringing change via outreach and providing educational workshops to teachers, families, and the public. “We can help educate and teach, but there needs to be a shift and systemic change.”

She’s working toward a time when a Jewish child won’t be asked to draw a family tree in class, without the teacher first thinking about the context and possible repercussions of such a request.

In that recent case, says Ms. Chernivsky’s colleague Romina Wiegemann, a child given such an assignment suddenly came home asking questions of a mother who wasn’t prepared to field questions about relatives lost to the Holocaust. When the mother raised the question with administrators, she found little support.

“We must think about the effect this has on children, and make sure schools engage with topics,” says Ms. Wiegemann.

Mr. Königsberg at the New Synagogue thinks that there’s reason to hope. “When I call the schools now, I get an appointment,” he says. “Last year, they ignored me.” But he sees the fight against anti-Semitism as a fight for democracy. “A true democracy doesn’t work with discrimination.”

A letter from

California dreamin’: Just how tough is it to buy a home here, anyway?

Home-buying in California is not for the faint of heart – or light of pocketbook. Our reporter’s experience offers a glimpse of why young people and families are moving out of state.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Ours is a house-hunting story with a happy ending. But every step along the way illustrates what people are up against if they are trying to buy a home in California.

More folks called it quits with California last year than moved here. The state’s population saw its lowest growth rate since 1900, according to estimates – meaning California is on track to lose its first congressional seat in history.

Basically, it’s way too expensive, with astronomical housing prices driving out young people who otherwise would be starting families, says demographer Dowell Myers.

“We’ve been talking about this for some time. This is it. This is the future,” says Professor Myers. “The baby boomers are retiring, and you have to get replacement workers, but the workers can’t afford to live here.”

During the holidays, my husband and I stopped to admire a neighbor’s Christmas display and met her mother, Arzella Valentine, who is in her 90s.

Arzella and I have something in common: a love of writing. She gave one of her poetry books to me and one to my husband, inscribing them both. Mine read, “Welcome to my new neighbors. You are going to be very happy here.”

I’m sure we will be. California’s challenge is to make sure many more people can afford that happiness.

California dreamin’: Just how tough is it to buy a home here, anyway?

Ours is a house-hunting story with a happy ending. But every step along the way illustrates what people are up against if they are trying to buy a home in California.

For the first time since 2010, more folks called it quits with California last year than moved here. The state’s population grew by a mere 0.35%, its lowest growth rate since 1900 (not a typo), according to new estimates from the state’s Department of Finance. The slow population growth means California is on track to lose its first congressional seat in history.

The sheen is off the Golden State, and that is a very big challenge for the world’s fifth-largest economy. Basically, it’s way too expensive, with astronomical housing prices driving out less-educated young people who otherwise would be starting families and becoming taxpayers, says demographer Dowell Myers of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. The number of young children in Los Angeles County – where we live – dropped 21% between 2000 and 2017.

“We’ve been talking about this for some time. This is it. This is the future,” says Professor Myers. “The baby boomers are retiring, and you have to get replacement workers, but the workers can’t afford to live here.”

The tepid population growth mirrors a national slow-growth trend. The U.S. Census Bureau attributes the trend to fewer births and more deaths. That’s true for California, too, along with slower immigration. But the biggest cause, according to the state, is more people packing up and moving to places like Texas, Arizona, Oregon, and Colorado.

According to Zillow, the median list price of a home in San Francisco was $1.35 million in November – the highest in the nation. Housing and high taxes are not the only factors driving people away. Take Victor Krummenacher, of the band Camper Van Beethoven. After 30 years in San Francisco, he cashed in his real estate and left in 2018. He now lives in his hometown of Riverside with his mom, touring and working as a graphic designer. He plans to move to Portland, Oregon, this summer.

Mr. Krummenacher says he left San Francisco because a long-term relationship failed, but so had the city’s quality of life. Artists used to be able to “throw it together” with part-time work and still focus on creativity, he says. With the tech boom, the city became “corporate” and unaffordable, clogged with traffic. Artists moved further out, or just plain out. Looking for a for-hire bass guitarist in a blues bar? Good luck.

He craved an environment more conducive to creativity. Even if he had stayed, getting to a yoga class might take an hour, “and then you’re going to have to step over people shooting up on the street, right? The streets are filthy, and you know, your car is going to get broken into five times a year. I mean, these things are all things that happened to me.”

Mr. Krummenacher says he’s “sensitive” to all the negative talk about San Francisco. He knows some “miraculous musicians” who still live there. But it’s not as if the Bay Area will produce “the next challenging wave of music.” It’s not a go-to place for a musician.

It wasn’t a go-to place for us, either. Even though we once lived in the Bay Area, we set our sights on Los Angeles County, where the median price is about half as expensive ($695,000 in November).

We arrived last May and were provided two months of corporate housing. We needed every single week, as we tried to break into a tight market. Of course, we set a top price. Of course, we had to adjust it upward – by increments of $100,000.

It seemed not to matter whether these were California ranch houses, English Tudors, bungalows, or Spanish style; they all drew multiple offers – sometimes more than a dozen – including all-cash bids from foreign investors. We were encouraged to submit cover letters and a photo with our offers. It was never clear whether these love notes were meant to endear us to the seller, or just show that we were not “foreign investors.”

That’s code speak for mainland Chinese looking to park their money in a safe place overseas. They are perceived as a plus and a minus – cash sales for sellers, but with a reputation for replacing ranches with McMansions, never actually occupying properties, and driving up prices.

A brush with celebrity broke up our summer of discouragement. We were all set to bid on a ranch – complete with pool and view of Los Angeles – when a little Google digging revealed that the owners had undergone a messy, public divorce. The man was a famous martial arts film star in China, who announced on social media that he was divorcing his wife because she was having an affair with his agent. A court had yet to decide how their assets would be divided up. Our real estate agent raised this with the seller’s agent, who quietly took the house off the market.

After this my husband suggested we check out a nearby property, even though it was beyond our top-top-top price. The orange door opened and we loved it. A real indoor-outdoor California home, graced by stately oak trees. Private. Quiet. Unknown to us, the sellers that day had dropped the price by $100,000 – the market was moving into high summer, buyers were dwindling, and the owners faced a deadline.

Now we have a mountain view and the occasional coyote – at nearly three times our property taxes in D.C.

When people ask me what I like about LA, the first thing I mention is the culture. All those artists seeking to “make it” here mean high-quality performances at the smallest venues. Our church’s Christmas concert featured a string of soloists who sounded like they perform with professional opera houses and symphonies – because they do. We sometimes attend living room jazz concerts at the home of former Monitor reporters.

During the holidays, my husband and I stopped to admire a neighbor’s Christmas display. I called out my approval to the woman sitting in a chair on a little stone patio. We walked up the drive and saw that a caregiver was bringing her lunch, while another helper was working on the lawn.

Introductions all around revealed the seated woman, Arzella Valentine, to be in her 90s, and the mother of our neighbor. Arzella and I have something in common: a love of writing. A broad smile on her face, she told us she had published two books of poetry and essays about growing up in the tiny African American town of Mount Olive, Arkansas.

She gave one to me and one to my husband, inscribing them both. Mine read, “Welcome to my new neighbors. You are going to be very happy here.”

I’m sure we will be. California’s challenge is to make sure many more people can afford that happiness.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Congress can lead on both war and peace

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In a rare case of unity Wednesday, lawmakers on Capitol Hill welcomed President Donald Trump’s decision not to retaliate against Iran for its missile strikes on United States forces. On matters of peace, members of Congress find it easy to achieve consensus with shared reason and wisdom. On preventing or encouraging a president’s ability to take military action, however, those qualities of leadership are too often missing.

On Thursday, in yet another attempt to control the powers of the commander in chief, the House planned to vote to block military action against Iran unless Congress authorized it. In the Senate, a similar bill stands a chance of passing. Yet as in past years, both chambers probably lack a supermajority to override an expected presidential veto.

The bipartisan praise for Mr. Trump’s restraint on Iran should now be mirrored in giving him definitive direction on how and when to use force against Iran to counter its aggression in the Middle East. For the world’s sake, the prospects for peace in the Mideast depend on the quality of deliberation in Washington. To rephrase a British prime minister, jaw-jaw can prevent war-war.

Congress can lead on both war and peace

In a rare case of unity Wednesday, lawmakers on Capitol Hill welcomed President Donald Trump’s decision not to retaliate against Iran for its missile strikes on U.S. forces. Both Democrats and Republicans welcomed his restraint and the pause for peace after five tense days following the U.S. killing of Maj. Gen. Qassem Soleimani, the head of Iran’s elite Qods Force.

Lawmakers also welcomed Mr. Trump’s call for European allies to join in negotiating “a deal with Iran that makes the world a safer and more peaceful place.”

On matters of peace, members of Congress find it easy to achieve consensus with shared reason and wisdom.

On preventing or encouraging a president’s ability to take military action, however, those qualities of leadership are too often missing – no matter who is president.

On Thursday, in yet another attempt to control the powers of the commander in chief, the House planned to vote to block military action against Iran unless Congress authorized it. In the Senate, a similar bill stands a chance of passing. Yet as in past years, both chambers probably lack a supermajority to override an expected presidential veto.

For more than 70 years, Congress has steadily ceded war-making powers to the chief executive, partly because new types of weapons demand quick decisions and partly to avoid blame for a conflict that goes badly. Yet after the latest close encounter with Iran, it is time for Congress to finally set aside partisanship and assert its constitutional responsibility on issues of war. This requires leadership in order to achieve what James Madison called “the cool and deliberate sense of the community.”

The bipartisan praise for Mr. Trump’s restraint on Iran should now be mirrored in giving him definitive direction on how and when to use force against Iran to counter its aggression in the Middle East. For the world’s sake, the prospects for peace in the Mideast depend on the quality of deliberation in Washington. To rephrase a British prime minister, jaw-jaw can prevent war-war.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Prayers for the planet

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Beverly Goldsmith

In the face of extreme weather events in Australia, in Indonesia, and elsewhere, hope and solutions can seem elusive. But a willingness to seek God’s guidance opens the door for divine inspiration that enables us to act wisely and safely.

Prayers for the planet

Here in Australia, we’ve been experiencing severe drought, heat, and bushfires. Many are worried that this confirms their fears of human-caused climate change. As the BBC put it recently, “The science around climate change is complex – it’s not the cause of bushfires but scientists have long warned that a hotter, drier climate would contribute to Australia’s fires becoming more frequent and more intense.”

So I’ve been doing something I’ve found helpful time and again in alarming or overwhelming situations: praying. I’m praying with the future safety not just of my country, but of this planet, in mind.

In doing so, I’m encouraged by a remarkable Bible example of an inspired response to climate crisis. Through a series of events, a young man named Joseph was sold into slavery and taken to Egypt (see Genesis 37-45). One night, the Pharaoh had a disturbing vision. He couldn’t understand what it meant, and neither could his advisors. Joseph, who had correctly interpreted two other men’s dreams a couple of years earlier, was asked if he could explain Pharaoh’s vision.

Turning to God as the source of all intelligence and right ideas, Joseph received the insight he needed to interpret what the king had seen. He told him that there would be seven years of abundance, followed by seven years of famine. Immediately, Joseph was given the job of implementing a plan to conserve the food produced in the good years. As a result of his wisdom and foresight, the people of Egypt survived the ensuing years of famine. Egypt was even able to feed those in neighboring countries who sought aid.

Where did the constructive foresight Joseph displayed come from? “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, asserts: “The ancient prophets gained their foresight from a spiritual, incorporeal standpoint, not by foreshadowing evil and mistaking fact for fiction, – predicting the future from a groundwork of corporeality and human belief” (p. 84).

Christian Science explains that God, Spirit, is Mind, the infinite intelligence that sustains God’s entire creation – including each of us, His spiritual offspring. When we tune in to this divine Mind through prayer, we receive direction. And as the spiritual image of divine Mind, we have the ability to pay attention and be receptive.

In this regard I’ve particularly appreciated a thought-provoking statement in Science and Health: “It is the prerogative of the ever-present, divine Mind, and of thought which is in rapport with this Mind, to know the past, the present, and the future.

“Acquaintance with the Science of being enables us to commune more largely with the divine Mind, to foresee and foretell events which concern the universal welfare, to be divinely inspired, – yea, to reach the range of fetterless Mind” (p. 84).

It is possible for us to discern, right now, actions to help keep our planet and its inhabitants safe. This is true for those of us in Australia and everyone around the world. There is an urgent need for solutions. God is always present to guide each and every one’s thoughts and actions for the benefit of all, and as we listen for that guidance, practical answers will come.

Another example of this is that of Moses, ancient Israel’s great national leader (see Exodus 17). Moses secured the release of his countrymen, who’d been laboring as slaves in Egypt, the same nation that had earlier benefited from Joseph’s spiritual insight and leadership. As the Israelites journeyed on foot through the wilderness, at one point they reached a place with no water.

Moses wondered what could possibly be done, in a desert environment, to address the urgent need. Turning to God for help, he was guided to strike the rock in Horeb with his staff, and water gushed out, saving the lives of the people relying on him.

Today, too, each of us can listen for divine wisdom, the inspired ideas that we need to act wisely and safely. Though I’m not a great leader like Moses, I’ve experienced this in modest ways in my own life, bringing a conviction that answers from God are always present to meet the needs of the day. We just need to listen for and act on them. Prayer affirming God’s good government of His creation – and willingness to heed the ideas that result from that prayer – opens the door for divine inspiration that protects and guides.

Adapted from an article published in the April 16, 2007, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Seeking shelter

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us. Please come back tomorrow when our Sara Miller Llana looks at the Iranian Canadians lost in the Ukrainian airliner crash and how they symbolize the talent and innovation in Canada’s immigrant community.