- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Our best defense against coronavirus? Each other.

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Today’s issue looks at coronavirus and the global order, Trump supporters’ views of the crisis, a volunteer spirit in France’s poorest areas, the Arab world’s dreamy “Dr. Fauci,” and museums turning kids into curators.

Here is a fact about the coronavirus pandemic: It follows a pattern of pandemics becoming rarer and causing fewer deaths.

Since the emergence of COVID-19 in China, much has been written about how it has traced the lines of commerce, using globalization to spread. But it is equally true that our global interconnection is also perhaps the most potent weapon we have against viruses.

“This is because the best defense humans have against pathogens is not isolation – it is information,” writes author Yuval Noah Harari in Time.

Centuries ago, the bubonic plague and smallpox killed a quarter of the populations of Europe and Central America, respectively. Even in 1918, the flu killed as many as 50 million people. Since then, however, outbreaks have been defeated by cooperation and global solidarity. Our Ned Temko writes about the stresses on those connections in today’s issue.

In that way, the coronavirus is bringing something deeper to the surface. “Today humanity faces an acute crisis not only due to the coronavirus, but also due to the lack of trust between humans,” writes Mr. Harari.

Ironically, the best defense we have against the coronavirus is one another and the knowledge we share.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Coronavirus tests global sense of who wins: ‘me’ or ‘us’

So what are the challenges to global solidarity? Ned Temko looks at how the virus is testing the architecture of alliances and partnerships from Europe to China.

It’s an age-old choice: between “me” and “us.” And so far on the global stage, nationalism – “me” – is winning.

The European Union’s COVID-19 reckoning is especially telling, because the EU should have been singularly well placed to mount a transnational response. When the pandemic struck Italy, Spain, and France hard, however, several member states tightened or closed borders. Some briefly banned exports to the worst-hit areas.

Then there’s the huge economic cost of all the shutdowns. Last week strained the EU to the breaking point as Italy and Spain argued for borrowing as a single bloc, taking advantage of northern states’ more solid credit rating, and rebuilding as a single bloc. Northern states demurred. The issue was finessed by a $550 billion package of EU support payments.

The COVID-19 crisis has seen “me” triumph over “us” elsewhere as well. Countries have competed for supplies and restricted related exports, while efforts to coordinate an international response have foundered. The main test may lie ahead, as countries decide how to reengage internationally as they rebuild their economies. One issue may determine how they move forward: relations with China.

Coronavirus tests global sense of who wins: ‘me’ or ‘us’

This past week, the 27-nation European Union came close to a breaking point. And while it managed to stave off the danger for now, its crisis has dramatically highlighted a key challenge from COVID-19 for national governments around the world.

It is forcing them to make an age-old human choice: between “me” and “us.”

For individuals, that means balancing personal needs with those of other people in the communities, societies, countries, and world of which we’re all a part. For governments, not just in Europe but elsewhere, the spread of COVID-19 has meant choosing between their national interests and a broader international engagement to confront a virus that holds no passport and recognizes no borders.

So far at least, nationalism – “me” – is winning.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

And one major question, when the crisis has finally passed, will be whether the increasingly fragile architecture of existing international relationships – political alliances, trade partnerships, and the global economic system as a whole – can or will be built back to anything like its former self. That’s likely to take on even greater importance with recent signs that China, the initial source of the coronavirus, does have a coherent and assertive international strategy for a post-pandemic world.

The EU’s COVID-19 reckoning is especially telling, because the EU should have been singularly well placed to mount a transnational response when the pandemic started hitting member states early this year.

The EU began life as a trading partnership. Yet in recent decades, it has become a fully fledged single market, with a shared passport, a shared currency, and an explicitly stated aim of achieving a similar level of political integration. The official phrase is “ever-closer union,” implying a kind of United States of Europe.

COVID-19 has put that vision to an unprecedented test.

The immediate response in February and early March as the pandemic struck with particular force in three member states – Italy, Spain, and France – was hardly an example of ever-closer union. A number of states tightened or closed their borders. With pressure to ensure adequate supplies of equipment, some EU states also briefly banned exports to the worst-hit areas in Italy or Spain.

Some of this was simply a gut public-health reaction to the sudden spread of the virus. But the real fault line inside the EU – and the cause of last week’s crisis – involves what might be called the second pandemic: the huge economic cost of the shutdowns being used to stem the spread of COVID-19. It essentially pits Germany and other wealthy, fiscally conservative states in northern Europe against more heavily indebted countries of the south.

The aftermath is going to require similarly huge government expenditure, and ultimately borrowing. Since two of the countries most severely hit, Italy and Spain, are already heavily indebted, the argument they’ve been making is for the EU truly to act like a union: to use the northern states’ more solid credit rating as ballast, and to borrow as a single bloc to rebuild as a single bloc, by issuing so called EU coronabonds.

But Germany, Austria, The Netherlands, Finland, and other northern states wanted no part of an arrangement linking their finances to what they view as a fiscally imprudent south. The issue was finally finessed by a $550 billion package of EU support payments. But the coronabond issue remains on the table, to be considered by the heads of government against the background of a warning from Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte that it represented a “challenge to the existence” of the EU.

Beyond Europe

The COVID-19 crisis has seen “me” triumph over “us” elsewhere in the world as well.

Not only have borders been closed and transport links severed. Just as within the EU, countries large and small have been scouring worldwide for supplies of ventilators and other items while seeking to restrict the export of such equipment available domestically.

So far at least, efforts to coordinate a concerted international response have foundered.

A recent conference-call meeting of the Group of Seven, the world’s leading economies, failed even to issue a joint statement, due to objections over a U.S. insistence that it include a reference to COVID-19 as the “Wuhan virus.” U.S. President Donald Trump has also retreated from past administrations’ leadership role in containing international health crises, disregarding calls for the creation of an international task force. This week, he announced plans for the U.S., the principal donor to the World Health Organization, to suspend its funding.

There does seem to be a growing recognition among other G-7 members – the major European states, Canada, and Japan – of the potentially enormous threat the pandemic still poses to less developed nations and refugee populations. Britain, for instance, has announced additional funding for international relief organizations and for WHO.

Still, the main me-versus-us test may lie ahead, as countries decide whether, or to what degree, to reengage internationally as they cope with the inevitable challenge of rebuilding their domestic economies.

Both politically and economically, there have been signs that one issue above all may determine which way they move: relations with China.

Economically, the scramble for equipment to deal with COVID-19 has underscored the degree to which China has become an indispensable part of the global supply chain, not just for consumer products or manufacturing components but countless other products – including critical ventilators and protective equipment.

Politically, that’s become part of China’s own strategy to burnish its image and maximize its influence as the pandemic spreads more widely. In recent weeks, it has made high-profile deliveries to a number of areas in need of supplies, including Italy, Canada, Britain, and New York state in the U.S.

At the same time, it has been reframing the narrative around COVID-19 – a virus whose existence it at first hid from view, and whose origins and extent it has so far chosen not to share in full detail. Instead, Beijing is now trumpeting its success in containing the spread within China, in clear contrast to the response of badly stretched health systems in Western democracies like the U.S. and a number of EU member states.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

In crisis, Trump’s most ardent fans find they love him more

Starkly partisan views of President Donald Trump persist during the coronavirus crisis, with his supporters seeing a man they can literally trust with their lives.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

To many on the left, President Donald Trump has been a manifest disaster in guiding America through COVID-19.

But as the United States navigates a spring season like no other, with much of its population at home and the economy frozen, President Trump’s core supporters remain staunchly behind the man they believe was Making America Great Again before the pandemic unexpectedly upset his plans.

According to a recent YouGov poll, 27% of Americans “strongly approve” of the president’s performance. That may be a rough measure for Mr. Trump’s true base, voters who will not abandon him under almost any foreseeable circumstance.

These supporters say the president is exhibiting strong leadership – and is rightly attuned to the need to get the economy moving again, despite warnings from public health experts that reopening workplaces too soon could lead to another spike in fatalities.

“The man is not a magician, but he’s doing everything he can,” says Maria Romero, who lost her job at a car dealership outside Chicago two weeks ago because of COVID-19.

She tunes into President Trump’s briefings every evening, saying they make her feel reassured and hopeful.

“Things were wonderful [before COVID-19],” she says. “He did it once, he’ll do it again. I trust him.”

In crisis, Trump’s most ardent fans find they love him more

To many on the left, President Donald Trump has been a manifest disaster in guiding America through the current pandemic.

But Maria Romero most definitely would beg to differ.

“The man is not a magician, but he’s doing everything he can. … He believes in America and he believes in Americans,” says Ms. Romero, who lost her job at a car dealership outside of Chicago two weeks ago because of COVID-19.

She tunes into President Trump’s coronavirus briefings every evening, saying they make her feel reassured and hopeful.

“I could be bitter, I could say, ‘This is President Trump’s fault’ – but it’s not,” she says. “Things were wonderful [before COVID-19]. He did it once, he’ll do it again. I trust him.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

As the United States navigates a spring season like no other, with much of its population sheltering at home and the economy frozen, President Trump’s core supporters – call them “superfans” – remain staunchly behind a chief executive they believe was Making America Great Again before a pandemic unexpectedly upset his plans.

Democrats may maintain that the president initially downplayed the threat from the novel coronavirus. The media may report that the White House failed to prepare for the pandemic by making sure the U.S. had adequate testing and medical supplies.

But these superfans, while they agree the crisis has been devastating, believe that President Trump has responded with strong leadership. They think the president is rightly attuned to the need to get the economy moving again as soon as possible, despite warnings from public health experts that broadly reopening workplaces before a vaccine or treatments are available could lead to another spike in fatalities.

This unshaken faith in Mr. Trump’s leadership is not necessarily because his supporters have been less impacted by the virus – although so far it has hit hardest in urban areas like New York and Detroit, which tend to be predominantly Democratic. Still, plenty of the president’s supporters have lost loved ones to COVID-19. Recently, the Front Row Joes – a self-named group of Trump superfans who travel the country going to MAGA rallies – lost one of their own: Benjamin Hirschmann, a young political science student from Fraser, Michigan, known for his smile and MAGA cape.

In response, however, Mr. Trump’s fans are more convinced than ever that he’s the right man for the job. In interviews, more than a dozen Trump voters tell the Monitor they believe Mr. Trump’s unique talents are needed now more than ever.

“Everything he is doing is for the good of the country,” says Cindy Hoffman, who owns an industrial tool sharpening business with her husband in Independence, Iowa. “It feels like he’s my father. He’s going to protect me.”

As polarized as ever

In a world in which everything has suddenly been upended, it’s perhaps revealing that views of Mr. Trump have remained as polarized as ever.

Typically, support for the president goes up in a crisis, as Americans “rally round the flag.” Former President George W. Bush’s approval rating, for example, hit a record 90% after the terrorist attacks of 9/11. And in early to mid-March, Mr. Trump’s overall approval rating did rise modestly, from 44% to 53%, according to a Morning Consult poll.

But that proved to be short lived. By the beginning of April, Mr. Trump’s approval rating had fallen back to 49%, with the gap between Democrats and Republicans even wider than before. In the latest Morning Consult poll, it stands at 43% – about where it was at the end of February.

The president’s critics say his “rally round” bump evaporated because his leadership through the pandemic has been poor. Mr. Trump’s initial dismissal of the threat from the novel coronavirus as “contained” – and the critical time his administration wasted once the threat was known, when it should have been ramping up testing and the production of medical supplies – has almost certainly cost lives, they say.

The president’s hard-core supporters, however, disagree. According to a recent YouGov poll, 27% of those surveyed “strongly approve” of President Trump’s current job performance. That may be a rough measure for Mr. Trump’s true base, the voters who will not abandon him under almost any foreseeable circumstance.

The daily press briefings the president has been holding may be one way he’s continuing to keep his most committed fans behind him, says Jason Mollica, a lecturer at American University’s School of Communication.

While Mr. Trump has always had a knack for grabbing the spotlight, he has been more visible than ever in recent weeks. In some ways, the briefings have taken the place of MAGA rallies, providing a forum for the president to promote himself and attack the news media, impart valuable information, and make assertions that are not always backed by facts.

“Every day he has a chance to reach his people,” says Mr. Mollica. “He tells his supporters he is doing everything he can to support us Americans. … To everyone else, he might not make any sense, but [his fans] believe he is making America great again, even as the numbers [of coronavirus deaths] climb.”

Indeed, many Trump supporters believe that the crisis would be far worse with anyone else in the White House.

When Mr. Trump moved to restrict flights from China back in January, he was called a racist, notes Tommy Dugo, a moderator for a pro-Trump Facebook group. “But that probably saved a lot of lives,” says Mr. Dugo.

And if the president snaps at reporters during his daily briefings, it’s only because they refuse to acknowledge anything positive, says Randal Thom, a dog breeder and painter from Lakefield, Minnesota, and a founder of the Front Row Joes. “You see the reporters there giving him snarky comments and ‘gotcha’ type of questions,” says Mr. Thom.

Mr. Trump has been criticized by many for suggesting he may want to reopen America before health officials deem advisable, saying: “We cannot let the cure be worse than the problem itself.”

The president’s supporters often repeat this sentiment, with some adding that the COVID-19 models predicting high mortality rates seem like part of a Democratic conspiracy to keep the markets down and hurt Mr. Trump’s chances of reelection.

According to a YouGov poll from late March more than half of Mr. Trump’s voters believe it will be safe to end social distancing by May 1, whereas the majority of those who voted for Hillary Clinton believe that move should come later. Likewise, while almost 65% of Clinton voters say Americans are still not taking the risks of coronavirus seriously enough, some 60% of Trump voters say Americans are either behaving appropriately or overreacting.

Some of the president’s supporters, including Mr. Thom, recently created the group “ReOpen America” to try to show lawmakers that many voters agree with the president.

“We are doing this to counter the left’s strategy,” says Mr. Thom. “Their narrative is to keep America shut down.”

Shared experiences

Of course, not all of Mr. Trump’s voters are thrilled with his handling of COVID-19. Katy Ritter, a stay-at-home mom in Louisville, Kentucky, voted for Mr. Trump in 2016, but she’s had some buyer’s remorse watching the president’s recent press conferences, and is not sure she’ll vote for him again in November.

“We need to be led by a more compassionate person,” says Ms. Ritter, pointing to Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear as an example. “We’re all in this together, and I want [Trump] to give us some of that unity that Andy is giving us.”

And there are some issues where Trump supporters and critics widely agree – such as support for the $2 trillion CARES Act, the largest emergency aid package in US history. According to the YouGov poll, a majority of both Trump and Clinton voters “strongly approve” of the coronavirus relief legislation’s payments to Americans making less than $99,000, extended unemployment eligibility, and its $117 billion for hospitals.

“Usually I’m not a fan of doling out money. I think people should make their own way,” says Ms. Romero, who recently got two part-time jobs: one at Home Depot, and one at a local grocery store. “But the stimulus is a necessity right now. This is uncharted territory.”

The isolation of quarantine is also a shared experience across party lines. Like many Americans, the Front Row Joes – who often would wait in line together for days in advance of Mr. Trump’s rallies – have been looking for ways to connect in this unprecedented time.

Last week a dozen of them from across the country logged into Zoom for a “virtual flag drop,” reciting the Pledge of Allegiance together from their pixelated squares, some posing in front of Trump posters, others wearing red hats.

The Joes have also been connecting on Facebook to share memories of Mr. Hirschmann. They’ve been sharing news articles about the 500 cars that partook in a drive-by vigil in front of the Hirschmanns’ home in Michigan, and photos of Taco Bell chalupas, Mr. Hirschmann’s favorite.

When Ms. Hoffman first heard the news about Mr. Hirschmann’s death from COVID-19, she immediately called his cell phone – praying it wasn’t true. But Mr. Hirschmann’s mother answered, and confirmed that her son had passed away.

“He was a mixture between my brother and my son,” says Ms. Hoffman, her voice wavering. “He would worry about me and I’d worry about him.”

Still, Ms. Hoffman doesn’t blame Mr. Trump in any way for what happened – and she doesn’t believe Mr. Hirschmann would, either.

“I trust [Trump] with my life. … And Ben said that actual phrase to me: ‘I trust Trump with my life,’” she recalls. If he were here, he would tell people “to trust Trump,” she says. “I know that’s what he would say.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Coronavirus lockdown stirs can-do spirit in France’s poor suburbs

France’s pandemic lockdown is hitting its poor suburbs hard, compounding their problems. But they are also showing a communal, volunteer spirit that is helping them through.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Life was not easy in France's poorest suburbs, or banlieues, before the coronavirus pandemic. But the ensuing lockdown has magnified the inequalities for their inhabitants.

Many continue to take public transportation to get to work, raising health risks, or find themselves confined to tiny apartments with numerous people. In homes where internet connections are shoddy or parents are uneducated, home schooling is next to impossible. Local media reports continue to portray banlieues as hotspots for incivility and infection.

But the banlieues are also where those like Piroo, a resident of the Paris suburb of Sartrouville, are making a difference. “I realized that [the nightly tradition of] clapping for health care staff wasn’t enough,” he says. “We needed to do something concrete for them.” So he organized numerous local businesses – as well as neighbors stuck at home – to collect and donate food and prepared meals to local hospitals.

Such banlieue-based nonprofits demonstrate a unique solidarity that is guiding local communities out of their darkest days. “The volunteer sector is very strong in many working-class neighborhoods,” says Sylvie Tissot, a sociologist and professor of political science at the University of Paris 8. “Often times, people are united by shared hardship, poverty, and shortages.”

Coronavirus lockdown stirs can-do spirit in France’s poor suburbs

France’s poorest suburbs, or banlieues, have long struggled with notoriety as places where drug dealing, delinquency, and unemployment abound. Now, amid the country’s lockdown to contain the coronavirus pandemic, that reputation has only gotten worse. Local media reports continue to portray banlieues as hotspots for incivility and the propagation of the coronavirus.

It speaks to a discrimination felt twice over by those living with limited means, where many must continue working menial jobs during confinement or already lack adequate housing and resources.

It's also shortsighted, for the banlieues are where those like Piroo, a 20-something resident of the Paris suburb of Sartrouville, are making a difference. “Faced with this epidemic, I realized that [the nightly tradition of] clapping for health care staff wasn’t enough,” says Piroo, who uses an assumed name in his charity work to protect his privacy. “We needed to do something concrete for them.”

So via his local organization, Les Grands Frères & Soeurs De Sartrouville, he organized Sartrouville residents to donate time, food, and acts of goodwill to help those in need, particularly the country’s overtaxed health professionals. Through his efforts, numerous local businesses – as well as neighbors stuck at home – have donated food and prepared meals for local hospitals. And jumping off from a neighborhood cleanup program he was involved with last summer, he launched the #CleanTonHall initiative, calling on young people living in public housing to clean their buildings, in order to take the pressure off cleaning staff.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

As France’s lockdown continues into its fourth week, banlieue-based nonprofits are working to highlight the inequalities experienced by those living in the country’s poorest neighborhoods and reverse the negative image surrounding them. They also intend to show that a unique solidarity exists there that is guiding local communities out of their darkest days and setting an example for the rest of the country.

“The volunteer sector is very strong in many working-class neighborhoods,” says Sylvie Tissot, a sociologist and professor of political science at the University of Paris 8, whose research focuses on public housing and gentrification. “Often times, people are united by shared hardship, poverty, and shortages. This creates solidarity between people and the desire to help one another.”

Banlieue-bashing

Even if France has made strides in recent years to improve misconceptions around banlieues, their negative reputation has been hard to shake. Since France's lockdown began, people from impoverished communities have been photographed congregating outside in groups, having run-ins with police, or robbing shuttered stores.

Métropop, a nonprofit that aims to stop “banlieue-bashing,” says France’s working class are neither irresponsible nor blind to the risks of the coronavirus, and that France’s suburbs have suffered stigma for 40 years.

“There has been a media portrayal pointing the finger at people from certain working-class neighborhoods, that they’re not respecting the lockdown, even if we can see the same behaviors in other well-to-do areas,” says Virginie Lions, director of a community involvement branch of Métropop.

In addition, these same communities face double discrimination. Not only must they battle their negative representation, but they are the populations making the most personal sacrifices during the lockdown. While hordes of wealthy French set off for the countryside ahead of the lockdown or are comfortably working from home, the confinement has magnified the inequalities for those less fortunate.

Many continue to take public transportation to get to work, raising health risks, or find themselves confined to tiny apartments with numerous people. In homes where internet connections are shoddy or parents are uneducated, home schooling is next to impossible.

Medical deserts – communities suffering from a lack of health care professionals – are also deteriorating as the pandemic continues. Seine-Saint-Denis, the poorest department in the Paris region, has one of the highest death rates due to the virus, counting more than 500 as of early April and a 63% jump in mortalities during the last half of March.

“Being confined in the banlieue is different from anywhere else: no backyard, no balcony,” says Madeleine, a young woman from Saint Denis who told her story to Métropop. “When I open my window, all I see is other buildings. Everyday I turn in circles, looking for something to occupy my time.”

Others recount a constant police presence and undue violence toward its youth population. In early April, several videos circulated online of young people being thrown to the ground by groups of police after they were asked for the official form that French people must carry when venturing outside during the lockdown.

“The populations that are struggling the most are the ones who are the least protected,” says Marie-Hélène Bacqué, a professor of urban studies at the University of Paris-Nanterre. “They’re the ones who must continue working – as cleaners, delivery people, or supermarket cashiers. They’re fundamental in ensuring that our daily lives continue and yet they’re the least protected in terms of public health.”

“Diversity and solidarity”

The shared discrimination and lack of resources that many in Paris’s banlieues face has acted as the glue that unites communities together. Living in close proximity to one another, often fighting the same fights, translates to a natural desire to reach out to one another.

“There is a form of solidarity that already exists here, people very easily organize volunteer missions,” says Ms. Bacqué. “In studies I’ve conducted, when people are asked what characterizes their neighborhood, they say ‘diversity and solidarity.’”

Many groups in Paris’ banlieues have worked to change the negative image of their hometowns through community action – and they haven’t stopped their activities simply because of the coronavirus lockdown. If anything, it has made the push for volunteerism even stronger, such that the country has seen a big enough spike in volunteerism that many nonprofits are having to turn people away.

In addition to Piroo’s Sartrouville initiatives, a host of nonprofits are reorienting their activities to help some of the most vulnerable populations, who are even more isolated during the confinement period.

Emergence 93, which normally works to reintegrate former juvenile prisoners back into the community, has helped its youth organize a campaign to get donations for Seine-Saint-Denis’ homeless population. And nonprofit Frères d’Espoir, a brother-sister team that operates out of Limeil Brévannes southeast of Paris, has continued its volunteer actions of handing out food, clothing, and hygiene kits to homeless people across Paris.

“People who live in the banlieues are normal. We have jobs. We’re not all druggies or throwing rocks at the cops,” says Piroo, from his home in Sartrouville. “There are some fantastic people that live here and there are really great things taking place.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Stepping Up

From healing hearts, to stealing hearts: Jordan’s ‘Dr. Fauci’

In the midst of a pandemic, what qualities do you want in a government health messenger? Someone who is gently reassuring? Authoritative yet kind? How about rock-star handsome, too?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Jordan has had early success containing the coronavirus, using a near-total shutdown that is more than flattening the curve. But within the first few days of the lockdown, a new epidemic emerged: Jaber-mania.

Heart surgeon Saad Jaber was thrust onto Jordan’s national stage by the COVID-19 crisis less than 10 months into his tenure as health minister. He has become the face of the government’s response – a face many find pleasing.

Each night at 8 p.m. sharp, Dr. Jaber stands in front of TV cameras, his wavy graying hair coiffed to one side. In a soothing velvety voice, he updates the nation on the latest coronavirus measures, urges people to follow guidelines, and says: “We can do this together.”

America’s Anthony Fauci may be on bumper stickers and bobbleheads, but Dr. Jaber is the subject of love ballads, poetry, and portraits. In WhatsApp groups and on Facebook, his legions of fans share their latest music videos and memes of Dr. Jaber, almost always with floating cartoon hearts and lines of poetry professing their – and a nation’s – love.

Then there are the songs. “There is something hidden and dangerous, who will help us endure?” sings one woman. “Saad Jaber!”

From healing hearts, to stealing hearts: Jordan’s ‘Dr. Fauci’

Each day, Jordanians under coronavirus lockdown turn to one man to get the facts – and swoon.

While Americans have Anthony Fauci, Jordanians have a “nation’s doctor” of their own: Health Minister Saad Jaber.

While Dr. Fauci is on bumper stickers and bobbleheads, this Jordanian physician is the subject of love ballads, poetry, and portraits.

Thrust onto the national stage amid the COVID-19 crisis less than 10 months into his tenure, the heart surgeon-turned-minister has become the face of the government’s response – a face many have found pleasing. Each night at 8 p.m. sharp, Dr. Jaber stands in front of TV cameras, his wavy graying hair coiffed to one side, and in the soothing velvety voice of a jazz DJ updates the nation on the latest coronavirus cases and government steps.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Using his gentle bedside manner, he kindly urges his fellow “brothers and sisters” and “my loves” to follow guidelines, telling them: “We can do this together.” Perhaps most shocking to Jordanians accustomed to stony-faced officials: He smiles. Often. He dons leather jackets, jeans, and polos more often than a suit. He is savvy at social media.

Within the first few days of lockdown, a new epidemic emerged in Jordan: Jaber-mania.

Even journalists and columnists routinely refer to him as “the handsome doctor,” and “Jordan’s George Clooney.” Others comb through his career in the army medical corps and in the operating theater for awe-inducing stories of inspiration.

But “Minister Clooney” is not winning over Jordan with a friendly smile and facts alone; Dr. Jaber has overseen Jordan’s early success in containing COVID-19, pushing for a near-total shutdown that is more than flattening the curve – it’s squashing it.

Jordan has seen a peak of 40 cases per day drop to zero to five new daily cases. There has been a total of 450 cases, 350 full recoveries, and eight deaths in a tiny kingdom where 90% of residents live on 5% of the land and every greeting comes with a kiss.

Dr. Jaber has earned a legion of fangirls. Mothers, grandmothers, professional women, and young girls across the country say they “melt” at his calm demeanor and smooth talk of social distancing and hand washing. Nor are men immune to his charms.

In WhatsApp groups and on Facebook, Jordanians share their latest music videos and memes of Dr. Jaber, almost always with floating cartoon hearts, heart-eyed smileys, and lines of poetry professing their – and a nation’s – love.

“There is a medical emergency: Your handsomeness is killing me!” writes one.

Then there are the songs. Jordanians have posted Bedouin love ballads reworded for Dr. Jaber, and even written songs and poems of their own.

“There is something hidden and dangerous, who will help us endure?” sings one Jordanian woman. “Saad Jaber!”

Jordan’s composer laureate, Omar Al-Abdallat, known for his chest-thumping nationalist songs about the king, army, and tribes, produced a toe-tapping ode to Dr. Jaber from self-isolation.

Dr. Jaber’s rock-star status is even more remarkable that it comes in Jordan, where citizens have low views of officials whose attempts to reach out to the public are seen as cringe-worthy or condescending.

Here government officials are tolerated, not beloved. But Dr. Jaber has broken the mold.

In a time of COVID-19 confusion and fear that has tasked Jordan’s military with patrolling the streets, his calm demeanor, fact-based briefings, and casual language have transformed the conversation in a panicked nation to a relaxed chat with a concerned uncle or a warm neighbor passing on sage advice.

But perhaps what is most refreshing is his honesty.

He admits he doesn’t have all the answers – and won’t pretend that he does. He even apologized on national TV for saying that the shemagh, the checkered Arab headscarf, could help protect against the virus if worn like a bandana.

“I don’t know and nobody knows how long this virus will last,” Dr. Jaber reminds interviewers, “but I know we can defeat this pandemic together.”

When hundreds of citizens violated the national curfew on the first day, he was direct, rather than angry: “Breaking the curfew won’t look so manly when your son gets sick and there is no hospital bed for him, or your mother has to lie in a hospital corridor like we see in the West.”

Pre-COVID, Dr. Jaber chafed at his ministerial post, preferring to be in the field, and one day back in the operating room, saving lives.

But his sudden celebrity status has had a real impact: His nightly briefings have become must-watch TV in Jordan.

Jaber fans discuss how the virus spreads, the proper way to wear a face mask and stay 2 meters apart, how young people can get sick or carry coronavirus or be asymptomatic. His visits to hospitals with patients and health care workers are viral sensations.

“If the minister cannot cure coronavrius,” asks one fan on Facebook, “can he cure my longing heart?”

Editor’s note: The statistics about number of cases were updated April 28, 2020.

As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

What if curators were teens? Museums try it.

It’s perhaps no surprise that museums would be different if they were run by teens. A few cities are getting a taste of what that looks like – and what young people value.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

When a group of young people was asked to curate an exhibition about black artists at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, the group chose to focus on the plurality of black experiences.

Jadon Smith wanted viewers to “see the beauty in blackness,” but he also wanted to inspire young people to consider careers in the art world. He says if he could do it – with no art experience – then so can they. “I’m a city kid, just like them,” he says.

“Black Histories, Black Futures” is the museum’s first exhibition curated entirely by high school students. It is the culmination of a partnership with local youth empowerment organizations, and reflects a growing trend, one that has museums working to engage and represent a more diverse population within the field of fine art. (The MFA is currently closed, but a “Making of” video about the exhibition is available online.)

“This institution is 150 years old. And so what does that mean for young people? Where do young people belong in such an old institution?” says Layla Bermeo, an associate curator at the MFA. “This project really tried to argue that young people belong in the center.”

What if curators were teens? Museums try it.

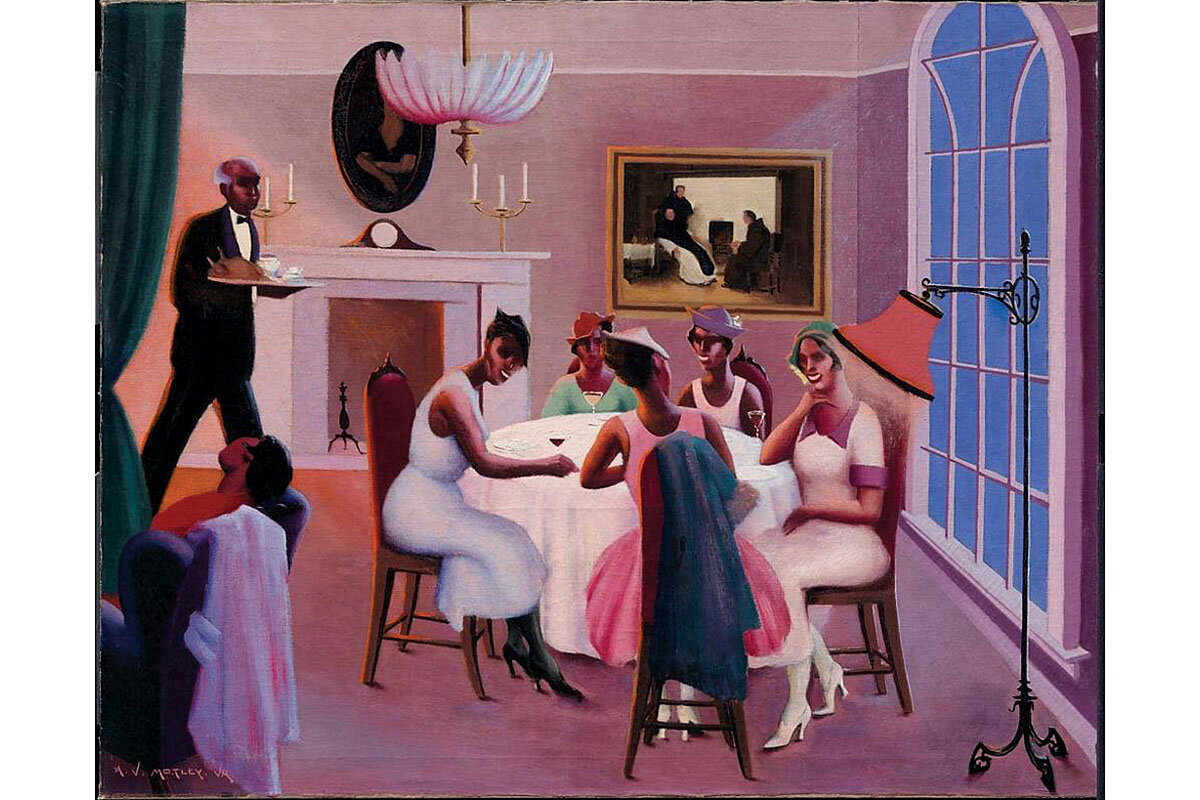

Jadon Smith steps closer to his favorite painting by Archibald Motley, carefully examining the details he’s looked at many times before, a smile from ear to ear. At the center of the piece, five elegant women dressed in their Sunday best sit in a restaurant. One woman, hidden in the background, catches his attention.

“Women are the centerpiece of the whole entire painting,” says Jadon, a junior at John D. O’Bryant School of Mathematics and Science, during a visit to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts in early March. “They’re supposed to be there to be seen. Don’t ignore them. Notice that they’re there, appreciate the fact that they’re there.”

Jadon is one of six local teens selected to craft “Black Histories, Black Futures” – the museum’s first exhibition curated entirely by high school students. The MFA’s exhibition, the culmination of a partnership with local youth empowerment organizations, reflects a growing trend, one that has museums working to engage and represent a more diverse population within the field of fine art. Including young people in the curation process not only trains the next generation of curators, say museum staffers, but it also helps aging institutions display refreshing and inclusive exhibitions inspired by the young curators’ own experiences.

“This institution is 150 years old. And so what does that mean for young people? Where do young people belong in such an old institution?” says Layla Bermeo, an associate curator at the MFA. “This project really tried to argue that young people belong in the center.”

Engaging teens across the U.S.

Some museums are connecting directly with high schools to include students. The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, for example, partners with two high schools for its young curators program, according to Julie Charles, director of education at SFMOMA. The Teen Creative Agency program at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art has been so successful that the museum restructured its building to include a glass room at its center so the public can see how the students are being taught. (While the museum is currently closed, the teens have been using the MCA’s Instagram account to highlight local artists and designers.) The Cleveland Museum of Art has a teen curation team called Currently Under Curation that creates exhibits for both the museum and local libraries.

“I think at least the field is acknowledging it and understanding that we need to take action in order to really change things,” says Melissa Higgins-Linder, director of learning and engagement at the Cleveland Museum of Art. Calling the programs a first step, she says she hopes the field is “recognizing the real and true value of those perspectives and not just paying lip service to them.”

The current opportunities build on ongoing efforts. In 1993, the Getty Foundation in Los Angeles founded the Getty Marrow Undergraduate Internships initiative. Since then, the program has involved more than 3,000 interns from underrepresented communities. The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation in New York has funded undergraduate curatorial fellowship programs at a number of American art museums since 2013. In 2017, the Ford Foundation and the Walton Family Foundation also partnered to launch an initiative in which 20 museums across the country received grants to support the diversification of staff and leadership.

“For museum professionals that are supervising the interns, it provides them with new perspectives, another voice that can be represented at their institutions,” says Selene Preciado, program assistant at the Getty Foundation. Along with mentoring and guiding the students, the opportunity also helps in diversifying the field, she says. “It’s a slow process. But fortunately, because we’ve been around for such a long time, we are able to see the fruits of that.”

In Boston, “Black Histories, Black Futures” highlights works by well-known 20th-century artists of color, as well as local artists, some presented in the MFA for the first time. Besides the opportunity to offer something new for its 150th anniversary, the exhibit is a way for the MFA to fulfill a goal of being welcoming and inclusive – an aim that took a hit last spring when a group of minority students said they were harassed by security officers during their first visit to the museum.

Shared experiences

In creating “Black Histories, Black Futures” the student curators had a lot of freedom. The only prerequisite was to showcase black artists, says Ms. Bermeo. The interns decided to make sure they were portraying the plurality of black experiences.

Jadon, for example, wants viewers to “see the beauty in blackness,” but he also wants to inspire young people to consider careers in the art world. He says if he could do it – with no art experience – then so can they. “I’m a city kid, just like them,” he says.

All the pieces in “Black History, Black Future” focus on powerful images of black communities. “It’s a completely different kind of exhibition,” says Ms. Bermeo. “This one really centers the types of objects that this group of young people wanted to see here in the museum, works of art that reflected their experiences versus maybe a kind of more art historical one that would grow out of one of my projects or one of the other curators’ projects here at the museum.”

The works in the exhibit – which is expected to run through June 20, 2021, though the MFA is currently closed due to the coronavirus outbreak – are drawn largely from the MFA’s own collection, supplemented by loans from the Museum of the National Center for Afro-American Artists. (Some of the pieces can be seen in a “Making of” video on the museum’s website.) The exhibit is divided into four thematic sections: “Ubuntu: I Am Because You Are,” celebrating the black community; “Welcome to the City,” focusing on urban scenes; and “Normality Facing Adversity” and “Smile in the Dark” both focusing on images of dignified black families before and after the civil rights movement.

One of the great visual chroniclers of 20th-century America, Motley – who painted Jadon’s favorite, titled “Cocktails” – was known for depicting the blossoming of black social life and jazz culture in vibrant city scenes. “To me [“Cocktails”] was the embodiment of just Ubuntu itself, just community building, showing that there’s more to black culture than just the civil rights movements,” says Jadon. “That shouldn’t be the first thing to pop in your head.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Crossover lessons: Earth Day and the pandemic

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

It’s been a half-century since the first Earth Day on April 22, 1970. In a less unusual year, that 50th anniversary might have brought worldwide notice. But a pandemic has consumed public attention. Yet the issues that Earth Day highlights are as urgent as ever.

One issue is that humanity’s view of the natural world may be changing. COVID-19 is believed to have leaped to humans from another species. Will fear grow that other forms of life are to be avoided? Or will a commitment grow to live in harmony with the natural world?

Another issue posed by the virus: Will the need to reignite faltering economies result in less protection for the environment? That question poses a false choice. A healthy economy rests on a healthy environment.

Earth Day has always been a call for individual action. Just as the COVID-19 crisis is bringing forth solutions, new approaches are required on climate change. This year’s Earth Day, coming during a pandemic, is a reminder of the need to solve a problem involving the whole planet. If humanity is in harmony on that, it can find harmony with the natural world.

Crossover lessons: Earth Day and the pandemic

It’s been a half-century since the first Earth Day on April 22, 1970. In a less unusual year, that 50th anniversary might have brought worldwide notice. But a pandemic has consumed most public attention. Yet the environmental issues that Earth Day highlights are as urgent as ever. In many ways, they are woven with the coronavirus crisis.

One issue is that humanity’s view of the natural world may be changing. COVID-19 is believed to have leaped to humans from another species. Will fear grow that other forms of life are dangerous and to be avoided? Or will a commitment grow to more deeply understand and live in harmony with the natural world?

Another issue posed by the virus: Will the need to reignite faltering economies result in less protection for the environment? That question poses a false choice. The environment and economy are too interrelated to suppose each fits into separate boxes. “The economy is a wholly owned subsidiary of the environment,” pointed out Earth Day’s founder, Wisconsin Sen. Gaylord Nelson. “Not the other way around.” A healthy economy rests on a healthy environment.

The world’s economic system has experienced a great disruption. Governments are responding with unprecedented speed and massive spending. Old rules of the road are being abandoned. Will people now accept radical steps to curb climate change?

Each year lost in reducing carbon emissions will make the need for future steps to be more drastic. The National Geographic Society recently calculated how climate change might affect cities 50 years from now. Boston, for example, would have summer temperatures 8 degrees Fahrenheit hotter on average, along with 2 inches more rain.

The shutdown of businesses during the coronavirus outbreak has been a global experiment in the benefits of clean air. As of March 8, the forced shuttering of factories in Wuhan, China, and the resulting reduction in air pollution saved an estimated 51,000 to 73,000 lives, estimates Marshall Burke, an assistant professor of earth system science at Stanford University. That total is far more than the lives reportedly lost to the virus in the surrounding Hubei province.

Earth Day has always been a call for individual action, including lifestyle changes and investments in clean technologies. That grassroots momentum has led to “green” policies by most governments and to international climate agreements. Yet progress has been slow.

Just as the COVID-19 crisis is bringing forth innovative solutions to a complex and urgent issue, new approaches are required on climate change. This year’s Earth Day, coming during a pandemic, is a reminder of the need for global action to solve a problem involving the whole planet. If humanity is in harmony on that, it can find harmony with the natural world.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

No fear can stop humanity’s brotherhood and sisterhood

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By John Biggs

The Bible describes what removes fear: “perfect Love” (see I John 4:18). When we understand this divine Love – and our unity with Love, God – we’re able to rise above the heightened fear that surfaces during a time of contagion.

No fear can stop humanity’s brotherhood and sisterhood

I love to pray for the world, and I know I’m joined by brothers and sisters worldwide in these prayers at this time. The beauty of coming together in the face of something evil resonates deep within for many people.

So while we honor measures in place to physically distance ourselves from others when fears of contagion are running rampant, there’s a deeper unity that can never be lost. In the Lord’s Prayer, Christ Jesus instructed us to begin with a fundamental acceptance of our unity in God: “Our Father ...”

What a natural, normal, and healing implication of our spiritual origin as given in the opening chapter of the Bible, which says that man (meaning everyone, men and women) is made in God’s image and is seen by God as “very good” (Genesis 1:26, 31). The fears surrounding a harmful contagion, then, can never actually divide the forever established and harmonious spiritual family of man, under one Father-Mother, who is Love itself.

The writings of Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, bring out the great practicality of Jesus’ teachings, including the spiritual nature of true brotherhood and sisterhood that he proved. Her primary work, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” says, “With one Father, even God, the whole family of man would be brethren; and with one Mind and that God, or good, the brotherhood of man would consist of Love and Truth, and have unity of Principle and spiritual power which constitute divine Science” (pp. 469–470).

This spiritual brotherhood doesn’t require our physical proximity to be felt. A couple of years ago, I was praying for a friend who had contracted chickenpox. He had been put in quarantine at his college per state health board requirements, and was calling for Christian Science treatment. I got his call almost immediately after getting off a plane from a long weekend trip I’d been on. I almost didn’t answer the phone because I was feeling pretty beat. But a thought came very strongly that I should answer this call – that I had to be unselfish and be there for this brother in his moment of need.

Upon accepting my friend’s request that I pray for him, I shared a few ideas from the Bible and from the writings of Mary Baker Eddy, and began praying. I was initially tempted to feel that this illness was too big, too serious: Could prayer really help?

On the heels of that thought, however, I felt what I might describe as a wall of Love – another name for God – holding me up and reminding me of God’s love for this young man and me, and of my love for both God and my fellow man. In Bible language, this “perfect Love [cast] out fear” (I John 4:18), and I felt nothing but a deep sense of confidence in Love’s, God’s, power to keep this individual – and his whole college community – safe.

It was fitting that Love was so clearly the power I felt at work here; this particular illness often seems to inspire such fear of each other due to beliefs about contagion. This promise of the power of Love truly cast out those fears in my own thought.

I prayed with my friend every day, and we stayed in touch throughout the week. Every day we chatted, he told me he was feeling stronger and more like himself; lovely progress was being made. A Christian Science nurse who was on duty with him in his quarantine let me know that he had ceased to have any new chickenpox spots from the day he checked in, which was the first day he had been in touch with me.

He was released from quarantine soon thereafter (following state health requirements of when it was deemed safe for him to rejoin the community), and went on to enjoy a successful college semester.

How wonderful it was to feel the power of Love impelling this whole healing, calming all the fears surrounding the case. Worshiping one God, who is Love – not being overcome with fear – allows us to feel that inherent unity, the brother- and sisterhood of us all, wherein there is only Spirit’s precious creation.

A message of love

Let’s move!

A look ahead

Thanks for taking time to be with us today. Please come back tomorrow when we look at the Arab doctors, nurses, and pharmacists on the front lines of the coronavirus crisis in Israel and how attitudes toward them might be changing.