- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How to keep calm in face of pandemic and fire, and carry on

Today we cover European countries looking at easing lockdowns, how to help teens cope with isolation, the pandemic “time warp,” a writer’s Wuhan diary, and exploring science with kids stuck at home.

First, some thoughts on renewal.

Last week my friend Marcy in Ann Arbor, Michigan, was preparing a Passover dinner when a spark from the stove lit up a nearby basket. Soon the kitchen was in flames. She called the fire department and fled with her two dogs. Her house, damaged by smoke and water, was left uninhabitable.

By that evening, Marcy already had an apartment and a bounty of food, provided by friends. Most remarkably, she proceeded with the virtual Seder she had planned for family and friends across the country. None of us were surprised she pulled this off, but it was still an impressive display of resilience – a multihour meal she conducted with good cheer. Let’s also applaud the firefighters who retrieved her laptop, phone, and purse before boarding up the house.

Marcy should be back in her house next year. Across the nation, too, Americans are looking ahead to a time of renewal, though the coronavirus emergency is far from over. Yesterday, President Donald Trump laid out guidelines for reopening the country. He didn’t address the shortage of testing and left decision-making to the states. Then today, he fanned anti-lockdown protests, tweeting out calls to “liberate” three Democratic-led states.

But politics aside, planning is surely a process that people can agree is necessary. Governors are also looking ahead – as are other nations, as highlighted in today’s first article.

Now, on to our five stories.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

How two European countries are trying to safely end lockdowns

While everyone wants their national coronavirus lockdown to be over, figuring out how to phase it out safely is a task fraught with problems. In Europe, Austria and Denmark are two of the first to tackle it.

-

Denise Hruby Contributor

Even as the coronavirus pandemic continues to paralyze much of Europe, some countries – primarily the smaller ones that responded quickly to the outbreak – are beginning to try to relaunch society in the hopes that they have turned a corner. Austria and Denmark in particular are leading the way in restarting businesses and reopening schools.

But plenty of concern remains, not just among business owners and customers, teachers and parents. Experts warn that reopening too quickly could set off a second wave of infections – meaning those nations will have to tread a careful path.

“The countries looking at easing restrictions are ones that can see that the death toll is now falling,” says Martin McKee, professor of European public health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “Of course, the unanswered question is whether this will continue as they do ease up, but only time will tell. Other countries will be watching closely.”

How two European countries are trying to safely end lockdowns

Claudia Pulfer was excited to be back at work in the Fellner Gardening and Florist shop in the Florisdorf district of Vienna Tuesday, as Austria began to roll back its anti-coronavirus lockdown.

It clearly wasn’t business as usual. Staff are on reduced work hours, and supply chains have been disrupted. The Dutch tulips are missing, but at least the orchids and roses are in. And while spring is in the air, the streets largely remain quiet.

“People are timid and still worried,” she said. “But we’re selling a lot of flowers for people’s balconies, a lot of spring plants that need to be planted in people’s gardens now, and I can tell some were looking forward to finally buy them.”

Even as the pandemic continues to paralyze much of Europe, some countries – primarily the smaller ones that responded quickly to the outbreak – are beginning to try to relaunch society in the hopes that they have turned a corner. Austria and Denmark in particular are leading the way in restarting businesses and reopening schools.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

But plenty of concern remains, not just among business owners and customers, teachers and parents. Experts warn that reopening too quickly could set off a second wave of infections – meaning those nations will have to tread a careful path.

“The countries looking at easing restrictions are ones that can see that the death toll is now falling,” says Martin McKee, professor of European public health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “Of course, the unanswered question is whether this will continue as they do ease up, but only time will tell. Other countries will be watching closely.”

Finding a path back

Countering the spread of the coronavirus has meant strict lockdowns within European nations and the reimposition of long-abandoned borders between them. The pandemic has claimed more than 136,000 lives across the aging continent and, in many cases, has taken a devastating toll on health systems and the economy.

But many countries are starting to consider how to bring an end to their respective lockdowns. While France and Belgium are holding back, Italy and Spain, the two worst hit, are inching forward. Italy, which suffered the highest fatalities in the pandemic, is allowing some shops to reopen, but some regions have boycotted that decision. Construction workers have gotten the green light to resume their activities in Spain, but the state of emergency there has been extended. Germany, which has managed to keep its per capita death toll relatively low, has also announced plans to begin allowing small businesses to reopen next week under tight restrictions.

But reopening holds risks, even for those countries who have so far contained the coronavirus. Singapore, which was widely praised for its handling of the pandemic, is now fighting to flatten the curve again. The European Union on Wednesday warned its 27 members to tread carefully as they craft their national exit strategies.

“A lack of coordination in lifting restrictive measures risks having negative effects for all member states and creating political friction,” noted a roadmap document cited by The Associated Press.

Austria was one of the first European countries after Italy to impose strict lockdown measures, including the closure of restaurants, bars, theaters, schools, and nonessential businesses. Now the Alpine nation, which has so far reported about 14,300 cases and nearly 400 deaths, has allowed garden centers, DIY stores, and small shops to reopen as part of its first step toward normalcy.

Vienna’s largest shopping street, Mariahilfer Strasse, was quiet Tuesday morning, with just a few pedestrians roaming the streets and venturing in to shops. Most shoppers and customers sported surgical masks, which are widely available at pharmacies and grocery stores. Others donned homemade fabric ones with checkered or polka dot designs.

Only a handful of small businesses opened their doors on day one.

“People are still very scared. But I think very slowly they’ll get accustomed to this new reality and they’ll start going out and shopping again – at least that’s my hope,” says Adrian Alfaro, owner of the INTI ethnic clothes and jewelry store by the Westbahnhof train station. He had five employees before the lockdown started March 16. He kept three on shortened work hours and let go of the other two but hopes to rehire them once business goes back to normal.

“Honestly, I had very mixed feelings about opening again,” says Mr. Alfaro, who wears a light blue surgical mask and makes a point of regularly washing his hands and maintaining social distance. “I was looking forward to get back to work, after a month at home. But I knew it’s not going to be easy. … The economic loss is very, very big.”

At Fellner’s flower shop, Ms. Pulfer turns away an elderly woman who walks in without a mask, for her own safety.

“I’m not afraid of getting sick. I swap the gloves I’m wearing and I have several face masks,” says Ms. Pulfer. “I’m just happy to be here, back at work, and that the company I work for still exists. That’s important for me, that this company won’t go, that it will survive this crisis.”

“Usually we trust in the authorities”

Denmark, another frontrunner in reopening, is taking a different approach. The government decided to reopen kindergartens and schools for the youngest children. It proved a controversial decision that has left many parents and educators worried. Their concerns have been aired on a Facebook group, and an online petition urging authorities to allow parents to keep their children home has garnered nearly 18,000 signatures.

Steen Hansen, a cereal grower and cattle farmer living near the third-largest Danish city of Odense, considers it an outright terrible idea. After five weeks of staying put on the farm with his family and shifting all the shopping online, he wants to be sure that sending his little ones back to school is safe.

“We are shocked that the government wants to restart society this way, with the most innocent citizens, the ones who have a hard time to understand all the precautions that are necessary,” says Mr. Hansen. “It is hard to explain to the youngest children to stay apart from other kids and other grown-ups, to wash and disinfect your hands all the time, and not to play in bigger groups. … It is not their own choice but they will bring the disease to their parents and not all parents are young.”

He and his wife decided not to send three of their kids back to school for fear of contracting or spreading the disease. Taking care of a large family and juggling the farm requires optimal health, especially since grandparents cannot be leaned on at this time. It is unclear what that decision might cost them. School absences are typically penalized and could eventually put child subsidies at risk.

“The consequences will all be financial, and that is bad enough, but it is nothing compared to the well-being of our children and the well-being of our family,” says Mr. Hansen. “Many parents in Denmark don’t like this situation, but most of them will do it because they have to start their jobs and the government wants it. Usually we believe and trust in the authorities here in Denmark, but in this case it makes no sense. They can restart the society in many other ways.”

Some Danish schools have delayed their reopening to Monday to have more time to prepare and be able to adhere to government guidelines on hygiene and conduct. These include marking pathways to and from classrooms, seating children two yards apart, washing hands every hour, and playing in smaller groups.

“It is of course quite difficult to follow this guideline considering the group of age,” says Dorte Lange, vice president of The Danish Union of Teachers. “But the authorities say that they have calculated the risk.”

Given the different epidemiological dynamics across and within the nations of Europe, Professor McKee sees a unified exit strategy as unlikely. While methods will differ, the shared goal is to reduce transmission. The pandemic will “fizzle out” when “every person who is infected is transmitting it to fewer than one other person.”

“It will be absolutely essential for any country thinking of lifting restrictions to have in place a robust system of testing and contact tracing,” he says. “There will inevitably be further outbreaks but it is crucial that they are nipped in the bud.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Isolated from peers, teens find new paths to community

The pandemic lockdown is depriving teenagers of their social groups and casting a shadow over their college and job futures. How can parents help teens cope with the isolation and uncertainty?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The coronavirus pandemic and the lockdown to fight it are happening at the same time teenagers are seeking autonomy and trying to create their own identity.

Many middle-class teens and their parents express gratitude for their relative positions; they know some peers are in much more precarious situations. But, as time grinds on and the shock and novelty of lockdown wears off, they are also mourning what they’ve had to give up, from sports to dance to the daily eye rolls and jabs that are the nonverbal social fabric of adolescent years.

But Jeff Temple of the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston says that teens are also finding new ways to be themselves and adapt, even if in isolation, and that parents play a central role in helping them navigate the uncertainty.

Key to that is shifting the dominating narrative about screen time and that it’s ruining peer-to-peer relationships. In fact, argues Dr. Temple, it’s the reverse. “They know how to Snapchat with their friends, and FaceTime and text, and that’s real,” he says. “And so that might be what saves them from the loneliness during this pandemic.”

Isolated from peers, teens find new paths to community

Isabella Flood Wallin, a sophomore in the suburbs of Seattle, misses her freedom.

She’d take a bus to school and use it to move freely around the city, going with her friends to the International District after school for boba tea or wherever else she needed to be. But with physical distancing in place to fight the coronavirus pandemic, she’s sometimes felt like a “prisoner” inside her house – just at the time when “feeling parented is the most annoying feeling ever for me,” she says.

It’s affected her sleep. It’s heightened her anxiety – she remembers one night when her father, a surgeon, came home late and she convinced herself he was going to die. It’s aggravated her relationship with a younger sibling. Some of her friendships, all moved online, have flourished, but others have foundered without face-to-face contact.

“I feel it’s really elevated whatever emotions I was already having, especially anxiety,” she says. “You’d think with the more time you spent with your family that you would feel more connected. And I think it just hasn’t been true.”

Teens’ worlds have been turned upside down at the exact time that they are seeking autonomy and creating their own identity away from the centrality of their family lives.

Many middle-class teens and their parents express gratitude for their relative positions; they know some peers are in much more precarious situations. But, as time grinds on and the shock and novelty of lockdown wears off, they are also mourning what they’ve had to give up, from sports to dance to the daily eye rolls and jabs that are the nonverbal social fabric of adolescent years.

“Not only are they experiencing all the things that we’re experiencing, but we’re taking them away from this very developmentally critical time point in their lives where they’re supposed to be out of the house and developing these relationships and forming their own identity without their parents,” says Jeff Temple, professor and psychologist at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

He says that teens are also finding new ways to be themselves and adapt, even if in isolation, and that parents play a central role in helping them navigate the uncertainty.

Key to that is shifting the dominating narrative about screen time and that it’s ruining peer-to-peer relationships. In fact, argues Dr. Temple, it’s the reverse. “They know how to Snapchat with their friends, and FaceTime and text, and that’s real. And it’s something that they have been doing their entire lives,” he says. “And so that might be what saves them from the loneliness during this pandemic.”

Going online

Brenna Coughlin is the mother of two adolescent girls, Falon Doyle, age 12, and Morgen Doyle, nearly 17, in Topsham, Maine. And she’s helping to guide them by following their lead – something she has at times beheld with a sense of awe when it comes to their tech savvy. “They are so creative with their virtual world together,” she says – over FaceTime with her girls.

For seventh grader Falon, she misses having a steady stream of friends over, including her best friend, with whom she’d play outside for hours. But now they’ve shifted playdates to devices, doing riddles and personality quizzes. Sometimes they clean their rooms together online. For Morgen, a gymnast who recently got her driver’s license and the freedoms that entails, she misses the camaraderie of her team, but she and her friends now do their homework or make TikTok videos together.

This may have garnered a collective adult eye roll before lockdowns that have kept 1.3 billion students out of school around the world, but experts say that’s been misdirected. Strong online friendships more often predict stronger friendships generally. In a 2018 Pew Research Center poll, 81% of teen respondents say social media helps them feel more connected, not less, to their friends.

For Isabella, social media hasn’t always generated positivity, but it’s been key to coping now. She joined an Instagram movement called Girls of Isolation, founded by her favorite poet. It’s a collection of self-portraits in quarantine to empower girls. Isabella’s portrait was posted. “I think it’s been really powerful for me to see this is a worldwide thing, and that people everywhere are experiencing it, so this isn’t loneliness that is just felt by one person,” she says.

Peter Swanson, who knows teens well from his job as the former chair of the science department at Quincy High School outside Boston, says opportunities are everywhere now that structure is gone. An avid gardener, he is partial to earth-based projects. But whether it’s physical fitness or academic pursuits, it’s a unique time when students can define their own goals and interests without the pressures of achievement. “Here’s an opportunity for them to take responsibility for themselves,” he says.

Missing their peer groups

That’s not to say this is easy on teens, he says, especially those in at-risk social and economic environments.

A weekly poll in April by DoSomething.org revealed that young people said they feel frustrated (62.7%), sad (53.8%), and nervous (50.9%). Parents have watched changes in their teens that have been disconcerting.

Kathy Tonery, a special ed teacher in Pittsburgh and mother of three active boys, has watched her middle child, a 16-year-old social butterfly, close in on himself. “He generally is sleeping, sleeping, sleeping, and then he’s up all night. And I can tell he really misses that socialization. He doesn’t talk a lot, is very grumpy,” she says. “I try to let it go. You want to try and control everything and make everything better.”

But she knows she can’t, and experts agree parents are best off following their children’s leads and validating their feelings, however hard that might be. They should do it in their own moments of strength, not when they themselves are struggling.

For Julie Brazzell, another Pittsburgh-area parent, it’s what her boys have missed that hits the hardest in their home. Her eighth-grade twins missed their “graduation year” from middle school, packing up one day without realizing they’d not be back before the kids filter off to various high schools. Her junior is missing baseball season, a key year when he hoped to get some recognition that could translate into college scholarship money. “That was a gut punch,” she says.

She says she tries to refocus their attention on what they have: health, financial stability, and a new sense of togetherness. “Before, dinner was shoving stuff in a crock pot, and whoever comes in eats something real quick before we have to run somewhere else,” she says. Now there are family meals and game nights.

In the end, it’s teen optimism and open-mindedness that might be their best buffer in this extraordinary time period. Some might even realize that the academic environment is, actually, not so bad.

Seventh grader Falon, for one, can’t wait to get back: “I am most excited to go back to school. I honestly don’t care what class, as long as I get to see my friends, and my teachers too.”

Listen

What day is it? Why the pandemic warps your sense of time.

As the global coronavirus pandemic wears on, are the days and weeks blurring together for you? If so, you’re not alone.

The coronavirus pandemic and the social distancing it requires is affecting everyone differently. Some people have found themselves with far more time on their hands than they know what to do with. Others – including health care professionals, those caring for sick family members, and parents of young children – are overwhelmed by the day’s demands.

But if there’s one universal element to our experience, it’s that it is distorting our sense of the passage of time. February feels as though it happened a decade ago. Days blur together, and the hours alternatively fly by and slow to a crawl, depending on how anxious or bored we’re feeling and how many new memories we are generating.

What’s going on? Niels van de Ven, a psychologist at Tilburg University in the Netherlands, explains that these shifts in temporal perception happen when we lose the normal reference points that anchor our days and weeks. Listen to the full audio story. – Rebecca Asoulin, engagement editor, and Eoin O'Carroll, staff writer

Note: This audio story was designed to be heard. We strongly encourage you to experience it with your ears, but we understand that is not an option for everybody. For those who are unable to listen, we have provided a transcript of the story.

LISTEN: What day is it? Why the pandemic warps your sense of time

Essay

From Wuhan to quarantine: a writer looks back

Amid the pandemic, people around the world are experiencing the kinds of confusion and courage that Wuhan lived with for months. A writer looks back at the early days – and why it’s important to remember those sacrifices.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By a contributor

In some ways, January 23 was a normal winter morning in Wuhan: a little humid, sky still dark; the streets were wet, after a shower. Street lights were on, but there was no one on the street – just a few cars passing by.

Friends and colleagues kept sending me messages: Can you get out?

It was the early days of the coronavirus crisis. A few hours before, I woke up to the news that Wuhan had announced a lockdown from 10 a.m. Visitors, like me, were racing to leave. I kept thinking of the overcrowded fever wards where I’d been reporting and what it might mean to be stuck here: no hospital beds, scarce supplies, no friends.

I made it out that day: first to quarantine, in a hotel hundreds of miles away; then to my parents’ house; and finally to yet another quarantine at home. Life has gradually gone back to normal, and even in Wuhan people began cautiously heading out last week.

But I keep thinking back to what I saw there, and the stories that emerged after I left. I’ve wondered if my decision to leave that morning was right. As China and the U.S. start a blame game, it’s important to remember the sacrifices each individual made.

From Wuhan to quarantine: a writer looks back

There are traffic jams in Wuhan.

Normally, that wouldn’t be news. But after a nearly 11-week lockdown that stilled the city, Wuhan is gradually going back to normal. Intersections are busy again. People are cautiously heading out, equipped with hats, gloves, and masks, though others are still at home, afraid. Residents must scan a personal code on their phone and take their temperature before entering or leaving their neighborhoods. Some are mourning their dead – and a newly revised death toll puts the city’s estimate 50% higher than previously thought, with 3,869 people having lost their lives.

Still, it seems so different from the Wuhan I visited in January – the Wuhan I barely left in time.

***

I woke up at 5 a.m. on January 23, looked at the pop-up message on my phone, and felt my mind go blank.

The government in Wuhan, the Chinese city of 11 million at the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak, had announced a lockdown from 10 a.m.

“What?” Unable to believe it, I opened up WeChat, a popular messaging app. Reporters were already fleeing after the announcement a few hours before.

The night before, it had been hard to fall asleep. I kept thinking of the overcrowded fever wards where I’d been reporting: hundreds of patients packed in the waiting hall, waiting five hours or even longer for consultation, and people with fevers commuting from home to the hospital every day, because of the shortage of beds.

It felt out of control, and I’d already planned to leave that morning. But could I?

I packed at top speed and rushed to the lobby, trying to call a taxi online. No answer.

It was a normal winter morning: a little humid, not chilly, sky still dark. The streets were wet, after a shower. The road was wide, with street lights on, but there was no one on the street – just a few cars passing by.

Friends and colleagues kept sending me messages: Can you get out?

One week before, my editor had called, asking if I wanted to go to Wuhan, where the first few deaths had been reported. Instinct guided me: Yes, I’ll go. It might be the biggest news of the year. As a reporter, I should be there.

I didn’t know there was a possibility I couldn’t leave.

By 7 a.m. I’d made it to the train station, packed with passengers in masks. Some 5 million people managed to leave Wuhan before the lockdown, the mayor later estimated. I’d seen so many scenes in the hospital, and knew what being caught here might mean – no hospital beds, scarce supplies, no friends.

The decision seemed so arbitrary. They said the lockdown started at 10 – but they could change it to 7, just like that. I wouldn’t know if I could really leave until the moment I climbed on the train.

But I made it on board and the train slipped away, speeding toward my small hometown. Outside raced by scenery like writer Peter Hessler describes in “Oracle Bones” – “patterned as wallpaper: a peasant, a field, a road, a village.” But that day, there were no peasants.

The further we got from Wuhan, the less cautious boarding passengers were. When I asked one man in his 60s why he didn’t wear a mask, he said he didn’t know why people should. He’d never heard about the outbreak.

Surgery masks were useless, my taxi driver said, when I finally got off the train to transfer to a bus. He wasn’t wearing one, either. “The one you wear is just for psychological comfort,” he said. “You should wear a gas mask.”

Not a single passenger was in the waiting hall of the station. The smell of disinfectants dominated the air. I boarded a bus to the small town where my parents live, and started quarantine: 14 days in a hotel.

Time flies fast during quarantine. I followed news from Wuhan and my anger reached new heights as I read about the chaos. Patients were asking for help online since they couldn’t find space in hospitals. Doctors and nurses were crying as they worked without full protective gear, and saw people die every day. Even going to hospitals became a problem for patients and doctors alike, as the city stopped public transportation. A photo went viral, and infuriated many, in which several doctors stood in front of a desk, celebrating the Chinese New Year with only instant noodles as their dinner.

It just seemed as though there had been no preparations before the lockdown, I told a friend. When SARS broke out in 2003, she remembered, we asked how much we’d have to sacrifice. Here we were, 17 years later, still asking the same question. In decision-makers’ eyes, it seemed, the fatalities were just numbers.

Traditionally, many people watch the government’s gala on New Year’s Eve, but I was in no mood to. I felt such disappointment that I could not fall asleep for hours.

The next morning, on the first day of the New Year, my temperature was 37.3 C (99.1 F).

Once again, I was too worried to sleep. Scenes flooded back in my mind of doing interviews in Wuhan: those early patients’ symptoms, the risk of cross-infection, and how hopeless and frustrated they were.

Can I be cured in this small town, I wondered? Will I be infected in the hospital? Most importantly, what about my parents? I had to protect them.

As the morning sunshine gradually brightened up, I decided to go to the hospital, alone, if my temperature rose to 38 C (100.4 F). One day later, my temperature fell – and then again the next.

Locking myself in the room, I didn’t speak to anyone. Out my window was the bus station, now closed, though a dozen taxis waited day and night. I’ve never seen my hometown so deserted.

Eleven days later, I could leave for my parents’ house. By then the whole town was under lockdown, and all hotels and public spaces closed. Then I finally headed back to my flat in Beijing, to start another 14-day quarantine: the local government required all returnees to isolate themselves at home.

Besides, I had nowhere to go. Shops and restaurants were all closed in early February. To restrict strangers, we were all given a pass. At the entrance of the neighborhood, guards checked our passes, IDs, and temperatures.

Gradually, the city has gone back to normal. People started returning to their offices and hanging out on the weekend just as the rest of the world entered the kind of chaos Wuhan first experienced.

Yet life has been pretty bland, and ever since I’ve wondered if my decision to leave Wuhan that early morning was right. The question in my mind has only grown as I see now how many reporters decided to stay, and were able to share powerful stories.

Now that China and the U.S. have started a blame game, it’s important to remember the sacrifices each individual made. For many Chinese people, when they think about COVID-19, they will think about the lost lives, but also the freedom of speech.

I felt lucky when I got a chance to leave. But thinking on it now, I would feel lucky if I’d chosen to stay.

[Editor’s note: The Monitor is publishing this essay without a byline to protect the writer’s identity.]

Science at Home

At home with Galileo: Simple science for cooped-up kids

For people at home with kids, here’s an installment from our Science at Home series. In this experiment, kid scientists can test the idea that the heavier something is, the faster it falls.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

Why, on Earth, do feathers float and hammers drop? After all, a military parachute can weigh some 30 pounds, much heavier than a hammer, but it helps a paratrooper descend more slowly from a plane than a hammer would.

At home with Galileo: Simple science for cooped-up kids

On Aug. 2, 1971, NASA astronaut David Scott, while standing on the moon, paid homage to history’s most famous scientific experiment. In his left hand he held a falcon feather. In his right hand, a hammer. He stretched out his arms and released the two objects at the same time.

What do you think happened? If you were to try this on Earth, you would expect the hammer to land first and the feather to float gently down to the ground a second or two later. And maybe, after repeating this experiment a few times, you would come to the same conclusion that the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle arrived at: The heavier something is, the faster it falls.

It’s such a simple idea that it took one of the smartest people in history – a Renaissance-era Italian math professor named Galileo Galilei – to prove Aristotle wrong. Legend has it that Galileo dropped spheres of different masses from the Leaning Tower of Pisa, but we can re-create his experiment with two identical plastic water bottles.

Fill one bottle with water and screw the cap back on tightly. Now, fill the other one halfway with water and replace the cap. Now, you have two water bottles, one of which is about twice as heavy as the other.

Now, drop both bottles from the same height at the same time. If you like, you can use a smartphone or tablet to record the drop in slow motion.

Both bottles should hit the ground at exactly the same time. As you can see, the weight of the bottle has no effect on how fast it falls.

So why, on Earth, do feathers float and hammers drop? It’s not because they are lighter. After all, a military parachute can weigh some 30 pounds, much heavier than a hammer, but it helps a paratrooper descend more slowly from a plane than a hammer would. Feathers and parachutes fall slowly because they have a lot of surface area relative to their weight, allowing the air to push back on them as they fall.

But on the moon, there is no air to slow down falling objects, which is why, when Commander Scott dropped his feather and his hammer, they hit the ground at the same time.

“How about that!” said Commander Scott after dropping the hammer and the feather. “Mister Galileo was correct!”

This experiment is part of the Monitor’s occasional Science at Home series.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Debt forbearance as a tool to defeat the pandemic

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Much of the world is now in a spirit of generosity and forbearance toward debt – all in response to the unprecedented impact of the pandemic. On Wednesday, 20 of the world’s richest nations agreed to freeze the debt obligations of about a quarter of humanity that lives in the poorest 76 countries. The International Monetary Fund has announced an immediate standstill for debt owed by 25 developing countries. Within countries, both elected leaders and private lenders are stepping up to ease the financial obligations of such groups as small businesses, renters, or people saddled with student loans.

Because of the magnitude of the COVID-19 emergency, perhaps never before has the world had to come to grips with the nuanced difficulties of debt relief on such a large scale. By one estimate, 1 in 5 emerging market countries will default on debt obligations because of the financial damage from the coronavirus.

As commerce has become more global, so too has understanding of the need to sometimes go easy on debt enforcement while still ensuring repayment at some point. In a closely knit world, the benefit of debt relief flows both ways.

Debt forbearance as a tool to defeat the pandemic

Well shy of the winter holidays of charity and good cheer, much of the world is now in a spirit of generosity and forbearance toward debt – all in response to the unprecedented impact of the pandemic on vulnerable people and countries.

On Wednesday, 20 of the world’s richest nations agreed to freeze the debt obligations of about a quarter of humanity that live in the poorest 76 countries. The Group of 20 encouraged private creditors to also provide short-term relief.

A couple of days earlier, the International Monetary Fund announced an immediate standstill for debt owed by 25 developing countries. The IMF will rely on a special $500 million fund for “catastrophe containment and relief.”

Within countries, both elected leaders and private lenders are stepping up to ease the financial obligations of such groups as small businesses, renters, or people saddled with student loans.

In the United States, for example, many car companies are letting borrowers defer repayments on auto loans. Under a program from Freddie Mac, landlords with multifamily housing are allowed to defer loan payments for 90 days. And the federal CARES Act passed last month has forgiveness of new loans written into many provisions as well as forbearance toward existing loans.

Because of the magnitude of the COVID-19 emergency, perhaps never before has the world had to come to grips with the nuanced difficulties of debt relief on such a large scale. By one estimate, 1 in 5 emerging market countries will default on debt obligations because of the financial damage from the coronavirus.

“No region can win the battle against COVID-19 alone,” stated European countries in an appeal to provide debt relief for poor nations.

The necessity of mass debt relief is not new to global leaders. After World War II, Germany was granted generous relief on old debts which resulted in a strong economy today that is an anchor for Europe’s stability and prosperity. Starting in the 1980s, one debt crisis after another forced fresh thinking about the benefits and hazards of forgiving or deferring the debt of financially troubled countries. Will debt tolerance only encourage risky behavior in the future?

As commerce has become more global, so too has understanding of the need to sometimes go easy on debt enforcement while still ensuring repayment at some point. In a closely knit world, the benefit of debt relief flows both ways.

“Forgiveness is truly the grace by which we enable another person to get up, and get up with dignity, to begin anew,” says South Africa’s Archbishop Desmond Tutu. With those less well off in the world hit hard by the pandemic, debt relief is on the global agenda, demanding a renewed focus on patience and forbearance as necessary tools to defeat COVID-19.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Flu symptoms healed

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Russell Whittaker

When a man and his colleagues began to exhibit flu-like symptoms, he turned to God in prayer – and experienced how God’s limitless, healing love is present at every moment.

Flu symptoms healed

One day at work a few years ago, I noticed that some of my co-workers began to exhibit flu-like symptoms. A few days later, I began having similar symptoms.

At first I was angry that I had to deal with being sick, but then I remembered part of a sentence from “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science: “your remedy is at hand” (p. 385). This, along with prior healings I’d experienced in my life through prayer, reminded me that I could expectantly pray for healing.

I began by considering what Christian Science explains is everyone’s true identity: the child, or spiritual idea, of the divine Mind, God. The premise that we are mortal, subject to sickness, is an error about our real, spiritual nature. My prayers embraced my co-workers as well.

I went to bed feeling much better, but woke up feeling worse! This particularly troubled me because I wanted to have my full strength so I could do the tasks I needed to, which required constant and spirited moving about.

Every weekday, a “Daily Lift” email arrives in my inbox. These are brief, uplifting podcasts that can be found at www.christianscience.com/dailylift. I had the feeling that the message with that particular day’s “Lift” was the first email I should read, so I opened it up to see what was waiting for me.

The title – “Free from contagion” – caught my attention immediately, and I knew that it would be just what I needed. I listened intently to the ideas that the speaker was offering. She explained that we’re immune to harm because we are pure expressions of God. I liked that. Since I am the pure, spiritual expression of God’s goodness, there could be no impurity, no sickness in me.

The podcast continued with the idea that there is no fear in God, Love, and that divine Love fills all space. To me, this meant that there was no room in God’s universe for fear of sickness, or worry that I wouldn’t be able to do my job. The Bible assures us, “There is no fear in love; but perfect love casteth out fear” (I John 4:18).

Lastly, the speaker said, “We can feel this love and experience permanent peace, and health, now.”

On hearing this, I suddenly realized that every flu-like symptom I had previously felt was gone! I felt so clearly that divine Love, God – who includes only good, not sickness – fills all space.

I enjoyed the rest of the season without a recurrence of the condition. In addition, I noticed that fewer of my co-workers had symptoms of seasonal illness that year.

Each of us can turn to God in prayer and feel His limitless, healing love encompassing us.

Adapted from a testimony published in the Feb. 24, 2014, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

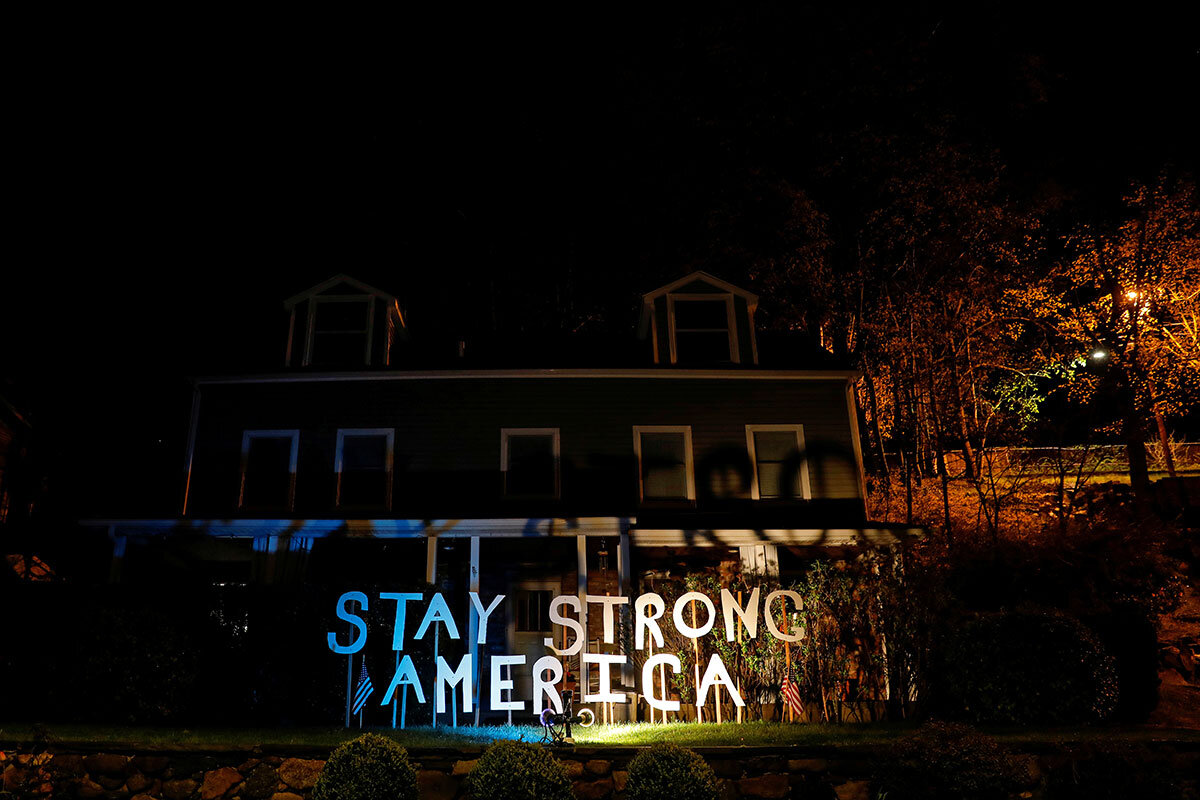

A message of love

Fighting spirit: America’s home front

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Please come back Monday for a different look at resilience after a fire. The Monitor’s Martin Kuz and contributor Wayne D’Orio visited Paradise, California, which burned in 2018 and is now drawing on communal strength amid the pandemic.