- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Can Biden deliver on ‘unity’? Does America want it?

- Who should judge what is true? Tackling social media’s global impact.

- An ocean apart, similar stories: US protests hit home in South Africa

- Horrified by strife in my America, finding hope in my Mideast

- Why coronavirus modeling is so hard to pin down

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Can weeks of protests make a difference this time?

In the two weeks since the killing of George Floyd, a yearning for social justice has overpowered calls for social distancing.

Some marchers stress that the pandemic’s toll has been just another indicator of inequity. Most have applied nonviolent tactics, including in places far from liberal enclaves.

The betterment of policing is a halting process. Some see small acts of police outreach as performative, and counter with new video evidence of brutality. Some view police unions as blind protectors of officers who overstep.

Still, Minneapolis police have banned chokeholds (and the city council seeks to restructure the department). Seattle has temporarily halted the use of tear gas. Talk of ending “qualified immunity,” which makes it nearly impossible to successfully sue law enforcement officers, has revived. So has talk of training standards for the nation’s 18,000-plus police forces.

The head of the NFL, which censured a star for kneeling in protest in 2016, apologized for having ignored the concerns of black players and now supports players’ right to peaceful protest. The energy of persistent protest may be lifting voter registration.

Now, calls are rising for service worthy of gratitude.

“We need police ... in our communities,” Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms told CNN Friday. “We all call upon them at one time or another.” A day before she had thanked protesters for honoring Mr. Floyd and others. “There’s something better on the other side of this for us,” she said, “and there’s something better on the other side for our children’s children.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Can Biden deliver on ‘unity’? Does America want it?

Joe Biden, who has clinched his party’s nomination, may find his campaign’s “unity” message appropriate to underscore at George Floyd’s funeral. But unity on racial justice will take compromise, and that remains in short supply.

From the start, Joe Biden has framed his candidacy around the concept of unity. “The country is sick of the division. They’re sick of the fighting,” the former vice president said at his campaign kickoff in Philadelphia last year.

But after a stretch of tumultuous events nearly unprecedented in modern U.S. history, the task of unifying the nation has never seemed more daunting.

The pandemic has taken more than 100,000 American lives and sent the economy into a tailspin that has left millions unemployed. Over the past two weeks, the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police has sparked massive protests for racial justice across the country.

For Mr. Biden, the volatile landscape is presenting an increasingly challenging balancing act. He is under renewed pressure to shore up support among progressives, without alienating swing voters who had been moving in his direction. Above all, he must somehow convince a fractured and exhausted nation that the problems it faces are fixable – and that finding consensus is both possible and desirable.

“Biden is calming at a time when people are hearing nothing but nasty noise, and that juxtaposition is to his advantage,” says Jeff Link, an Iowa-based Democratic consultant.

Can Biden deliver on ‘unity’? Does America want it?

From the start, Joe Biden has framed his candidacy around the concept of unity. In his campaign kickoff speech last year, he accused President Donald Trump of fanning, rather than working to bridge, partisan and racial divides – evoking a nation that, in his view, was yearning to come together.

“The country is sick of the division. They’re sick of the fighting,” the former vice president said in Philadelphia.

“Our Constitution doesn’t begin with the phrase ‘We the Democrats,’ ‘We the Republicans,’” he said. “We are all in this together. We need to remember that today, I think more than any time in my career.”

Mr. Biden’s decisive primary victories earlier this spring seemed to affirm that view. But as the campaign now moves into the general election phase – after a stretch of tumultuous events nearly unprecedented in modern U.S. history – the task of unifying the nation has never seemed more daunting.

The past three months have upended politics as usual, with the pandemic taking more than 100,000 American lives and sending the economy into a tailspin that has left millions unemployed. Over the past two weeks, the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police has sparked massive protests for racial justice across the country.

For Mr. Biden, the volatile landscape is presenting an increasingly challenging balancing act. He is under renewed pressure to shore up support among progressives who have been less enthusiastic about his candidacy, without alienating the swing voters who had been moving in his direction. Above all, he must somehow convince a fractured and exhausted nation that the problems it faces are fixable – and that finding consensus on those challenges is both possible and desirable.

“He’s being challenged to balance all these things, because Trump has so utterly failed to balance them,” says Democratic Sen. Chris Coons of Delaware. “This is a moment that demands leadership from someone who understands how to respond to a pandemic and bring us together. ... I think [Mr. Biden] is exactly the right man for the moment.”

A healer in chief?

Mr. Biden has seized multiple opportunities in recent weeks to try to cast himself as a healer in chief.

On the same day U.S. Park Police in Washington cleared a group of peaceful protesters from Lafayette Square with tear gas and rubber bullets so that Mr. Trump could pose for a photograph outside historic St. John’s Church, Mr. Biden was sitting in a black church in Wilmington, Delaware, listening to community leaders from 6 feet away.

Less than 24 hours later, Mr. Biden gave a speech in Philadelphia to a country he described as “crying out for leadership.” He called on Congress to enact a law banning police chokeholds and to create “a model use-of-force standard.” He also promised to create a national police oversight commission.

On Monday, Mr. Biden was scheduled to meet privately with the Floyd family, and he is expected to attend Mr. Floyd’s funeral in Houston on Tuesday.

“Biden is calming at a time when people are hearing nothing but nasty noise, and that juxtaposition is to his advantage,” says Jeff Link, an Iowa-based political consultant who has advised several Democratic presidential candidates. “Biden doesn’t have to outshout Trump, but he has to show how he’s different.”

Mr. Biden has deep reservoirs of affection in the African American community, among whom he built enduring relationships during the Obama years. It was black voters who carried him to a resounding win in South Carolina, reviving a candidacy that had appeared to be on its last legs, and ultimately helping make him the Democratic nominee. He officially secured the 1,991 delegates needed to claim the nomination this weekend.

But he is viewed less favorably by a younger, more left-wing generation, which sees him as too moderate to bring about needed change. Mr. Biden does not support calls to “defund the police,” which has become a rallying cry on the left in recent days. While he favors increased spending on other social programs, his campaign said Monday, he wants to increase, not decrease, police budgets for things like body cameras and training.

Mr. Biden has long-standing ties to union groups, including cops and firefighters, some of which have been trending more conservative in recent election cycles, and which Democrats were hoping to win back this year. In recent days, some law enforcement groups have expressed unhappiness with what they see as Mr. Biden’s failure to demonstrate sufficient support for their side, showing just how difficult it may be for him – or anyone – to bridge those divides.

In a poll released last week by Monmouth University, 89% of Democrats said they had “no confidence at all” in Mr. Trump’s ability to handle race relations. But only 32% of Democrats had a “great deal” of confidence in Mr. Biden on the matter. Among Republicans, 58% had a great deal of confidence in Mr. Trump, while 58% had no confidence at all in Mr. Biden.

Protesters gathering around a graffitied Robert E. Lee statue in Richmond, Virginia, last week said recent events had heightened their expectations of Mr. Biden from just two weeks ago.

“He thinks he’s automatically got the black vote because he was the right-hand man to a black president,” says Chenae Kirkland. “But he’s got to have a hand in these police departments, show us what he’d do,” adds her friend Leshayne Vialet, both bank employees.

Making promises is better than a photo op, they say – but it’s not enough.

Some express concerns about Mr. Biden’s own track record during his 36-year career in the Senate. In the 1970s, he was a vocal opponent of school busing, and he helped write the 1994 crime bill, which many believe was a key contributor to mass incarceration that has disproportionately affected black men.

“I felt like he was involved with all the stuff that’s led to where we are now,” says Andre Lynch, an Uber driver, gesturing to the dozens of activists climbing up the Lee statue. He adds, “When he ends up running this country, he’ll have a chance to redeem himself, especially after watching all of this unfold.”

“It’s not about him”

Of course, to have that opportunity, Mr. Biden needs to win the election. Recent polls have shown him gaining ground against the president. According to a Fox News survey, Mr. Biden is now ahead in Wisconsin, Ohio, and Arizona – all battleground states the president won in 2016, while the Monmouth poll has Mr. Biden with an 11-point lead over Mr. Trump overall. But these polls are mostly about Mr. Trump, says Patrick Murray, director of the Monmouth University Polling Institute.

“More so than any prior incumbent election, this is a referendum,” Mr. Murray says. But Mr. Biden still has to “get out there” and prove himself to Democratic voters.

And Mr. Biden faces unique challenges when it comes to unifying his party, not least because of COVID-19, says Robert Shrum, a longtime Democratic strategist and director of the University of Southern California’s Center for the Political Future. For three months, all campaign rallies have been canceled or turned into awkward “virtual” events, making it difficult for a candidate who thrives on rope lines and personal connections to reach voters.

The nominee’s acceptance speech at the party convention is typically an important moment, notes Mr. Shrum. “Just look at Al Gore in 2000,” he says. “He gained 15 to 18 points in 47 minutes.” But this year’s Democratic convention is increasingly looking like it will be held online, diminishing Mr. Biden’s ability to generate a big bounce.

It’s also unclear if televised debates between the candidates will happen. In a debate, Mr. Biden would have an opportunity to try to blunt Mr. Trump’s charges that the former vice president is “senile” and “sleepy,” just as John F. Kennedy countered Richard Nixon’s claims that he was too young and inexperienced to assume the presidency in 1960.

In the potential absence of these traditional events, Mr. Biden will need to be creative in how he engages voters, says Mr. Shrum. And his vice presidential pick will likely carry even more weight – not only because of Mr. Biden’s age, but also because of the absence of other high-profile campaign moments.

Above all, say several strategists, Mr. Biden needs to try to stay in the public eye as he has over the past week, and propose policies that follow through on his promise to bring unity.

“Part of [Mr. Trump’s] strategy will be to undermine voters’ confidence in Joe Biden,” says Monmouth’s Mr. Murray. “That’s why Biden has to be out there – so he can change people’s minds from ‘I think he can do a good job’ to ‘I know he can do a good job.’”

At the same time, Mr. Biden has made a point throughout the campaign of keeping the focus less on himself and more on the country.

In 2019, Mr. Biden’s campaign announcement video was centered on Charlottesville, Virginia, where two years earlier white supremacists had shocked the nation as they marched with tiki torches. In the video, Mr. Biden referenced Mr. Trump’s response to the event as a key moment that pushed him to run for president.

“We are in a battle for the soul of this nation,” he said. “We can’t forget what happened in Charlottesville. Even more important, we have to remember who we are.”

“I see Joe responding in a way that reflects who he’s always been,” says Senator Coons. “It’s not about him. It’s about us.”

Note: An earlier version of this story referred to “Washington police” as having cleared protesters from Lafayette Square. The story has been updated to make clear it was U.S. Park Police in Washington.

Navigating uncertainty

Who should judge what is true? Tackling social media’s global impact.

Social media can spread positive vibes or dangerous lies. But who should be trusted to judge which is which? Governments? Mark Zuckerberg? The work mostly lies with individual news consumers. Our global series “Navigating Uncertainty” continues.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

Social media. It enlightens, it entertains, it informs. And it obfuscates, inflames, and misleads as well. Facebook and YouTube have created and connected communities, but they have also propagated echo chambers of falsehoods that spread around the globe at the tap of a finger.

In the online world, there is always more than one version of the truth. Anyone can publish anything. But with no quality checks, it is easy for people to get confused.

The tidal wave of false information online about COVID-19 illustrates the problem. The ease with which far-right political parties such as the AfD in Germany can manipulate voters with misinformation has shocked mainstream parties, and the Chinese government has spread fake news on social media to smear pro-democracy demonstrators in Hong Kong.

Do we need gatekeepers to counter untruths? If so, do we trust governments to be arbiters? Do we trust the people who run Facebook and Twitter?

More and more organizations are springing up to promote media literacy, or to offer nonpartisan information sources. But in the end, say most social media experts, it is up to each one of us to think harder, and more critically, about the news we consume.

Who should judge what is true? Tackling social media’s global impact.

“Truth” Take 1: In 2019, a peaceful pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong stunned the world; at its peak nearly 2 million Hong Kongers gathered in the streets to oppose a move they felt would erode their beloved city’s autonomy.

“Truth” Take 2: In 2019, violent pro-democracy protesters smashed windows, stormed Hong Kong’s legislative chamber, and stockpiled petrol bombs. Aided by anti-China foreign forces, the rioters were a radical fringe element who drew fewer than 350,000 at the movement’s height.

The continuing struggle for Hong Kong’s future is being fought not only between police and demonstrators for control of the streets, but also online in the digital sphere, as Beijing and protesters vie for control of the political narrative. And, in the digital world, there is always more than one version of the “truth.”

“Anyone can publish anything,” says Johannes Hillje, a Berlin-based expert on social media and author of “Propaganda 4.0,” a book on German populism. “We still have no quality checks on this phenomenon.”

The result? Widespread confusion, just as social media networks command ever-greater shares of the global attention span. Last year, more than half the world’s population read something online that they believed to be true, before realizing it was false, according to Statista, an online business data portal.

This matters – because informed citizens are essential to the fight against ills such as climate change and poverty, and ultimately, to flourishing democracies. There are signs, say experts, that we are growing more discerning and warier of misinformation as we go online. A growing number of organizations are promoting media literacy and the importance of nonpartisan information sources, while social media platforms are under increasing public pressure to scrub misinformation.

Social media companies such as Facebook and Youtube have created and connected communities on a scale barely imagined a decade ago. Yet they have also propagated echo chambers of falsehoods that spread around the globe at the tap of a finger; the COVID-19 pandemic, the Hong Kong pro-democracy protests, and the rise of the far-right in Germany offer vivid illustrations.

How do we collectively tackle this problem? Who should judge what is true, and whether those who lie have the same right as anyone else to express themselves online? Is the idea that governments should police online content any more acceptable than the idea that for-profit companies such as Facebook or Twitter should fill that role?

“Now gatekeeping has to be done by every individual,” Mr. Hillje says. “We haven’t learned this as a society. That takes much more time than it does to introduce new technologies.”

The COVID-19 dimension

Digital citizens have been given a crash course by COVID-19, as misinformation about the coronavirus has spread widely.

Every aspect of the pandemic has been subject to online falsehoods, from where it originated to how infectious it is (deliberately released by a Chinese scientist? Secretly brought to China by a U.S. soldier?).

“Pandemics are fertile ground for people being vulnerable to conspiracy theories, because there’s a lot of uncertainty and fear,” says John Cook, a researcher at George Mason University in Virginia who studies media narratives around climate change. “But misinformation can kill.”

President Donald Trump himself has been a source of misinformation, tweeting approval of unproven methods of combating COVID-19. But he was angered when Twitter took the unprecedented step of cautioning users against the president’s “unsubstantiated” claims about the reliability of mail-in votes, and flagged another of his tweets as “glorifying violence.”

Building a party on misinformation

In Germany, it is the far-right Alternativ für Deutschland political party that has mounted the most successful social media strategy – and political misinformation campaign – in recent history. Standing on an anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant platform, the AfD has doubled its membership over the past seven years, largely on the back of online campaigns that spread inaccuracies, play on voters’ emotions, and highlight scandals that polarize and provoke.

That’s exactly the type of content that platforms’ algorithms tend to promote. Research has shown that tweaks to Facebook and YouTube algorithms over the years – designed to increase “engagement” – have also boosted divisive posts that provoke outrage. In 2019, the most-shared posts on Facebook had to do with child trafficking and abortion, according to the social media tracking company NewsWhip.

Few issues in Germany have been as politically divisive as migration, which the AfD has used to its advantage. The party’s social media posts have overstated the number of migrants seeking asylum in Germany by up to a million. Its leaders have falsely claimed that foreigners commit more crimes than Germans, and cautioned that Europe was becoming “Eurabia” with an advertisement depicting a white woman surrounded by Muslim men.

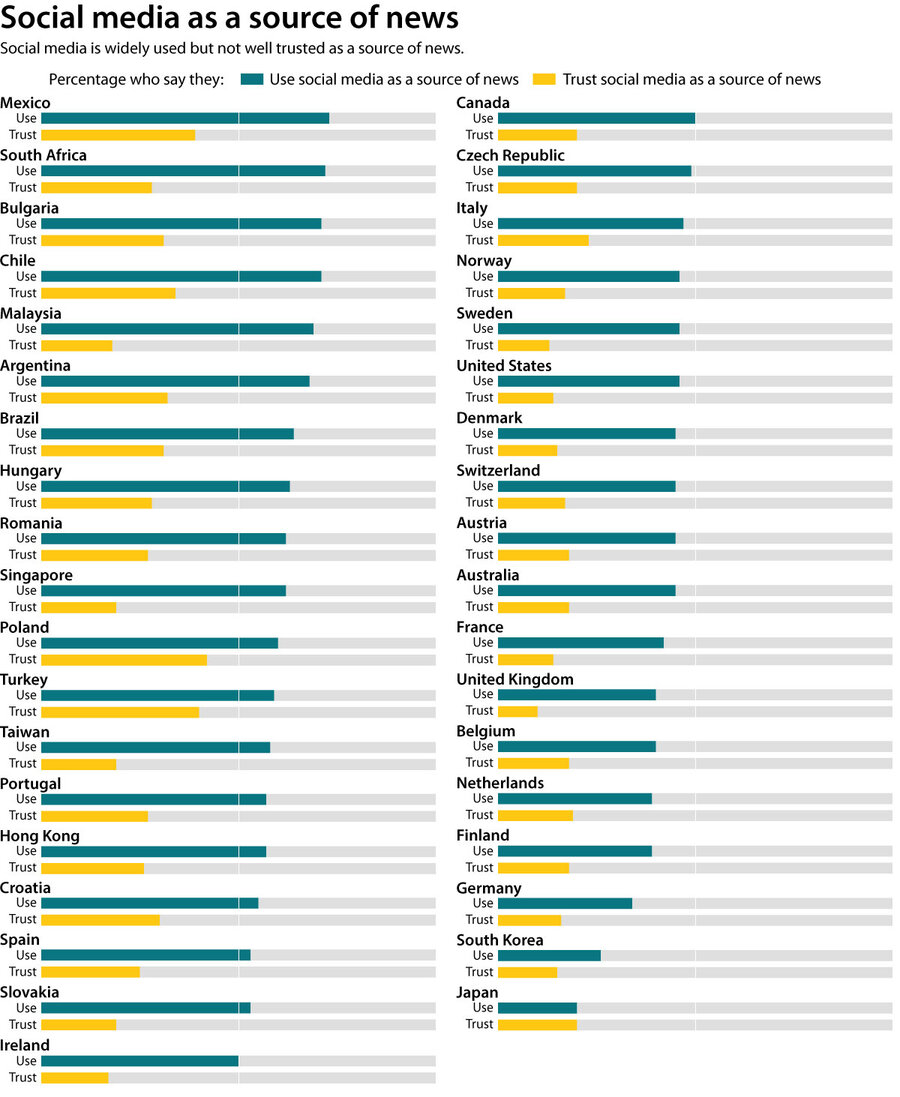

Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism

The party has created an “alternative media universe,” says Mr. Hillje. “They delegitimize mainstream media, and try to create a collective identity among their followers and their audience.” AfD Facebook posts are shared five times more often than posts by traditional parties, and the majority of political retweets relate to the AfD.

The AfD, however, says social media allows it to bypass mainstream media that “are heavily against and unfair to the AfD,” complains Ronald Glaser, the party’s lead Berlin spokesperson. “For our competitors, it’s not so important,” he says. “If they want to get the message out they call television.”

The AfD is now the third largest party in the German parliament, with the power to shape the mainstream political narrative.

Lies and video tape

Nearly a year after pro-democracy protests began in Hong Kong, the Chinese government moved last month to impose a new national security law that would further erode the former British colony’s political and cultural autonomy. That has given the protests new urgency.

Since the demonstrations began, pro-Beijing forces have mounted a potent misinformation campaign that sought to paint protesters as violent rioters aided by foreign agents. The goal was to turn mainland Chinese citizens and world public opinion against the movement.

Spreading “lies” was one part of a “three-pronged approach of censorship, surveillance, and misinformation,” says Lokman Tsui, a tech analyst and Google’s former head of free expression in Asia. The strategy is “sophisticated and weaponized to be on the offensive,” he says.

Chinese state media websites have misrepresented events, for example, by reporting a demonstrator’s police-inflicted eye injury as the work of a fellow protester, or falsely tweeting that 2 million Hong Kongers had signed a petition that Beijing be granted more power.

Pro-Beijing forces have also used fake social media accounts to post content, purchased ads on social media platforms, and encouraged Chinese officials and supporters abroad to tweet.

They are also seeking to sow division within private pro-democracy messaging groups.

“It’s really hard for people to realize what the Communist Party is doing,” says Isaac Cheng of the pro-democracy political group Demosisto. “Their aim is to demoralize the entire movement.”

On the flip side, protesters have posted thousands of videos and images to bring their story directly to the public. Their narrative has sometimes penetrated: U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi referred to “2 million protesters” as she urged Congress to support the “impressive … young people speaking out for democratic freedoms in Hong Kong.”

The true size of the protest marches last year? Around 800,000 at their peak, according to independent parties who relied on artificial intelligence and crowd-density measurements.

As a new round of protests gears up, the battle for global public opinion continues online, as fiercely as it does on the streets.

Who decides?

Who should be responsible for monitoring the content that fills our screens every day? “Who gets to decide what is an information operation or what is impulsive manipulation?” asks Evelyn Douek, an attorney and media rights researcher at Harvard University.

In the Hong Kong case, Twitter announced last August that it would no longer allow “state-controlled news media entities” to purchase advertising. Facebook and Google have also taken down some posts, fake accounts, and links, but offered little transparency about what they were doing, says Ms. Douek.

This patchwork approach illustrates a real challenge. Currently, policing content requires “private, for-profit companies to decide people’s speech rights all around the world,” Ms. Douek says. “This is untenable and unacceptable.”

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg does not seem keen on taking that responsibility. “I don’t think that Facebook or internet platforms in general should be arbiters of truth,” he told CNBC in an interview last month.

Facebook and YouTube have hired thousands of independent monitors to view content that’s flagged for review, and to remove inappropriate posts. But Mr. Zuckerberg acknowledged in his CNBC interview that the fact-checkers’ job is only to “catch the worst of the worst stuff.” He is now facing an open revolt among employees who want Facebook to do more.

On the other hand, inviting governments to get too involved in regulating speech amounts to “walking on ice,” says Stephan Mundges, a digital communications researcher at Dortmund Technical University. “If we don’t have robust democratic institutions, any way of trying to regulate disinformation means that freedom of speech is in danger,” he warns.

Take the example of South Africa, where the government has made it a crime to post COVID-19 misinformation, and also to criticize government, says Mr. Cook, the climate communications researcher. “It’s a very slippery slope.”

How the Germans do it … and the Americans

Trying to keep its footing on that slope is Germany. In the widest-ranging action by a Western democracy to date, the government two years ago compelled media platforms to identify and remove any content defined by the law as “illegal.” There are 21 categories, and platforms can be fined up to 5 million euros for failing to remove within 24 hours such content after it is flagged.

Human Rights Watch has declared the law vague and overly broad, and policymakers are currently considering changes including allowing users to appeal decisions. The effectiveness of the law is unclear; six months after it was passed, only a small percentage of reported content had been removed; Facebook had taken down only 20% of the 1,700 posts reported, and Twitter had removed just 10% of items reported as illegal by users.

The United States, as the world’s largest economy and headquarters for the globe’s most popular social media companies, is arguably the most important place in which to get the balance between digital freedom and responsibility right.

Being home base “gives regulators a certain degree of power over platforms that other jurisdictions don’t have,” says Ms. Douek. Yet the Communications Decency Act, which President Trump has sought to amend by executive order, essentially shields companies from legal liability for the content posted on its platforms. To date, any action must be largely prompted from within the company.

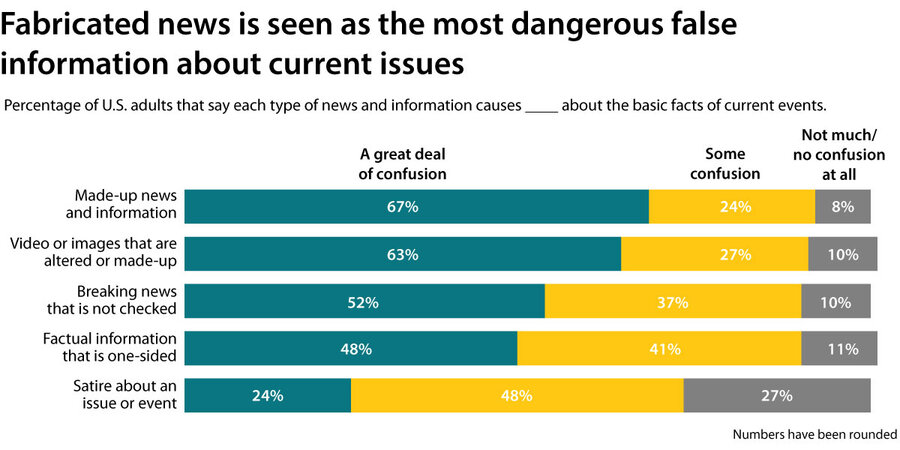

Pew Research Center

Michael Quinn contends that society should be thinking about ethics and responsibility even farther upstream – when systems are being designed. Dean of Science and Engineering at Seattle University, and author of the popular text “Ethics for the Information Age,” Dr. Quinn has made a mission of educating both computer science students and tech executives alike.

A significant challenge around artificial intelligence, he says, is the bias inherent in the data used to train these systems. “If the data is being collected from the racist past, you could be building a future in which automated systems are making racist decisions,” explains Dr. Quinn.

He points to a real-life example – a hospital monitoring system to recommend which patients should receive early interventions. Engineers found the AI system was recommending treatment more often for whites than for blacks, because historical data showed whites receiving more treatment.

But that was just because they had more money. “There need to be some guardrails,” Dr. Quinn warns.

The answer – think harder

Even if online gatekeeping institutions strike an acceptable balance, individual netizens will still tend to seek out information that supports their opinions. “Confirmation bias existed before social media,” says Mr. Hillje, the Berlin policy analyst. “This is a human phenomenon, not a digital phenomenon.”

John Gable, a former Silicon Valley insider who is now CEO of AllSides.com (which has a partnership with CSMonitor.com), intends to expose people to information from all political perspectives. “So people are empowered to decide for themselves,” Mr. Gable says.

AllSides.com places left-, center- and right-leaning news streams side-by-side, aiming to media “filter bubbles,” those echo chambers of information that build around single sources. Bursting these bubbles is easier than it may seem: Research has found 9 out of 10 students showed improved understanding after just one conversation with others across a spectrum of viewpoints.

Ultimately, the solution must include stronger critical thinking by individuals, argues Mr. Cook, the climate change communications researcher. People must constantly ask themselves, “What kind of filters do I use? What stereotypes do I have when I consume information? Where did this information come from?”

There are signs that people going online are doing this mental work. A Pew Research Center survey in 2018 showed 78% of Americans prefer news from sources without a partisan slant, up 14 points from five years ago. Last year, a Pew survey also found more Americans were concerned about made-up news than about climate change, racism, illegal immigration, and terrorism.

“The public intolerance for misinformation, and the danger of it, is so much stronger now than before,” says Mr. Cook. “The pandemic is a terrible situation, but there’s potentially the opportunity to build a new public resilience” on the foundations of new public awareness.

Society is building toward an inflection point after years of watching institutions upended by “fake news,” says AllSides.com’s Mr. Gable.

“There are thousands of organizations now trying to bridge the divide and have people talk to each other, both for our own health and to make governments more functional,” he adds. “We are scaling up our efforts.”

Pew Research Center

An ocean apart, similar stories: US protests hit home in South Africa

Global solidarity around protests for equal treatment has underscored our common humanity. Perspectives can vary. This report from South Africa finds a society reflecting on its own complicated, continuing history of police violence.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

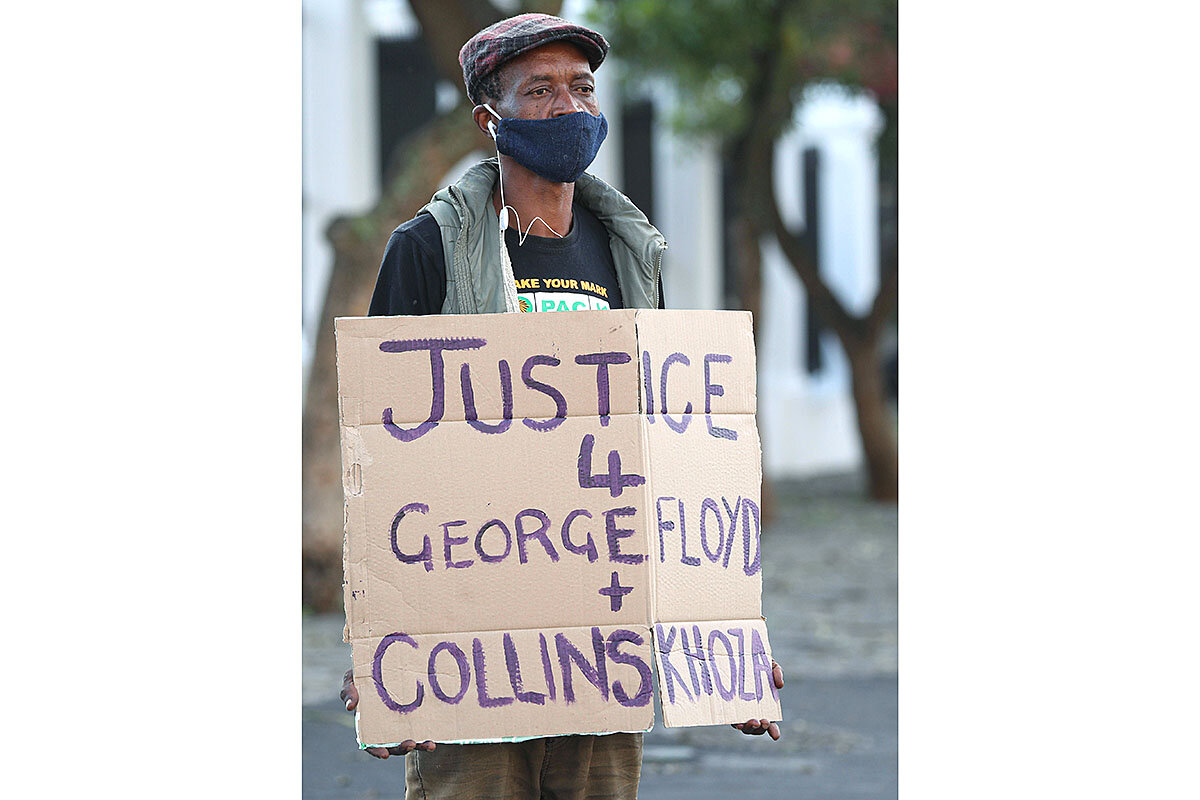

U.S. protests over the killing of George Floyd and other black Americans, like EMT Breonna Taylor, have inspired a cascading global reaction. And here in South Africa, with its own history of policing used to maintain white supremacy, there has been an outpouring of solidarity – but also, sharp calls to look inward.

A generation after the end of apartheid, violent policing of poor black South Africans remains common. The killing of Mr. Floyd has put renewed attention, for example, on the April death of Collins Khosa, whose family says he was beaten and choked by soldiers enforcing the country’s strict lockdown.

As in the United States, law enforcement here are rarely prosecuted for deaths or other acts of violence. There were more than 42,000 criminal complaints against the police here between 2012 and 2019, according to the country’s police watchdog. But just 531 resulted in successful criminal convictions, according to an analysis by South African investigative journalism outlet Viewfinder.

“The power of these institutions is the same across oceans,” says the organizer of a solidarity vigil in Cape Town last week. “We all live in a world where to be black and to be alive is to risk your own life.”

An ocean apart, similar stories: US protests hit home in South Africa

His family says they watched as he was held down and choked inside his own house here, slammed against a concrete wall and beaten with fists and the butt of a gun. Collins Khosa’s partner Nomsa Montsha screamed for the officers to stop, but they beat her too. Three hours later, as he lay on their bed holding her hand, she watched her husband die of what a postmortem would later clinically label a “blunt force head injury.”

It was a similar scene that has caused hundreds of American cities and towns to erupt in anguish and rage over the past week. Much like in the killing of George Floyd, Mr. Khosa, who died on April 10, was also a black man alleged to have committed a minor crime. Like in the United States, his attackers were law enforcement.

U.S. protests over the killing of Mr. Floyd and other black Americans, like EMT Breonna Taylor, have inspired a cascading global reaction. And it feels particularly familiar here in South Africa, where, as in the U.S., policing was historically used to maintain white supremacy. There has been both an outpouring of solidarity, and sharp calls to turn inward, to consider why violent policing of poor black South Africans remains common a generation after the end of apartheid.

“The experience of police brutality is something extremely common to the black South African experience,” says Solomzi Henry Moleketi, who stood outside the U.S. Consulate in Johannesburg Thursday with a group of friends holding signs that read “Africans Stand With Black Lives Matter.” “When we talk about the killing of George Floyd and Collins Khosa, we’re speaking of a common struggle.”

The video of Mr. Floyd dying under the knee of police officer Derek Chauvin, he added, “ripped my soul.”

History’s shadow

In many ways, Mr. Floyd and Mr. Khosa came from similar worlds: societies with deeply seated racism, where being black meant being far more prone to die young, go to prison, and live in poverty. Mr. Floyd died in a commercial borderland between many of Minneapolis’ more affluent, mostly white neighborhoods and its poorer mostly black ones. Mr. Khosa, meanwhile, was killed in his home in Alexandra, a crowded, mostly poor black neighborhood in Johannesburg that brushes up against Sandton, the skyscraper suburb known as “Africa’s richest square mile.” Both men lived, and died, with their country’s gaping inequalities on full display.

Both, too, came of age in worlds where police violence against black people was part of the fabric of society. Mr. Floyd grew up in the 1980s, when victims of police violence had to prove that force was not applied in a “good faith effort” to stop a crime. (Today, courts require an officer’s use of force to be “objectively reasonable” in the situation he or she is in.) Mr. Khosa also grew up in the ‘80s, the dying years of apartheid, when police and soldiers patrolled black neighborhoods in armored vehicles. Dozens of activists were killed by police, and thousands, including many children and peaceful protesters, were killed by security forces.

But the years that followed, as apartheid ended and Nelson Mandela’s South Africa came to be seen as the global poster child for racial reconciliation, the country’s police force began to change too. The percentage of white cops fell, and top leadership flipped from white to black. Yet the government wrestled with how to transform a police service designed to maintain white rule, often violently, into one that served its entire population.

For the first decade of democracy, the police worked to “demilitarize,” says Kelly Gillespie, a South African anthropologist focused on criminal justice. But as violent crime continued to plague the country, more aggressive tactics returned.

Some black South Africans welcomed the hard-line stance, hoping it would reduce the violent crime that stalked many neighborhoods. But it was no coincidence that the targets of this new wave of police brutality were largely the same they had been under apartheid, Dr. Gillespie says, because the communities most aggressively targeted were poor areas, which are still almost exclusively black.

“Since apartheid, there’s been a continuity in the violence experienced by poor black people at the hands of the police,” she says. “Police brutality is an ongoing story.”

And like in the United States, police officers in South Africa are rarely prosecuted for deaths or other acts of violence. There were more than 42,000 criminal complaints against the police here between 2012 and 2019, according to the Independent Police Investigative Directorate, the country’s police watchdog, including thousands of deaths, rapes, and assault cases. But just 531 resulted in successful criminal convictions, according to an analysis by South African investigative journalism outlet Viewfinder.

“The same across oceans”

For many black South Africans, then, what happened to George Floyd and other black Americans felt like an extension of their own experience.

“The power of these institutions is the same across oceans,” says the organizer of a solidarity vigil for Black Lives Matter in Cape Town last week, who asked to remain anonymous because she is a refugee who worries her activism could threaten her legal status. “We all live in a world where to be black and to be alive is to risk your own life.”

According to court filings by Mr. Khosa’s family, the 40-year-old father was at home with his family the Friday before Easter when soldiers enforcing South Africa’s coronavirus lockdown entered his property, alleging that he had violated the lockdown’s rules by drinking a beer in his yard. (Lockdown regulations prohibited the sale of alcohol, but not drinking at home.) Ms. Montsha and other witnesses have said the soldiers poured beer over his head before choking and beating him.

When the soldiers had gone, Mr. Khosa became increasingly incoherent, vomiting and struggling to speak, according to court papers filed by the family. He lay down, and died three hours later, as they waited for paramedics to arrive.

The South African National Defense Force has denied allegations that soldiers’ actions led to Mr. Khosa’s death. On May 27, its internal investigation cleared the soldiers who allegedly attacked him of responsibility for his death, writing that the “injuries on the body of Mr. Khosa cannot be linked with the cause of death,” and blaming him for “undermining” female soldiers. A police investigation is still underway.

“No one will fill that space,” Ms. Montsha said of Mr. Khosa, speaking to local TV news station eNCA last month.

For his family, he was “the man with the biggest heart in Alexandra,” says Wikus Steyl, the family’s lawyer. (The Khosa family, via Mr. Steyl, declined to comment for this story.) He stretched his own small paycheck to pay for the education expenses of kids in his neighborhood, and had instructed his family to take the lockdown seriously “to keep everyone safe,” Mr. Steyl says.

Harsh lockdown

His death quickly became a symbol for the brutal way South African police officers and soldiers have enforced the country’s coronavirus lockdown. By late May, some 230,000 people had been arrested for lockdown-related offenses. At least 11 South Africans were allegedly killed by police or soldiers in the same period, and another, sex worker Elma Robyn Motsumi, died in police custody, allegedly by suicide, under murky circumstances. To date, no soldier or police officer has been prosecuted. But public outrage is growing, in part because heavy-handed lockdown policing has been directed – albeit in a far less deadly way – at the rich as well as the poor, Dr. Gillespie says.

In mid-May, Mr. Khosa’s family won a court ruling that ordered, among other things, the creation of a simple way for citizens to report allegations of brutality, and of a strict code of conduct for lockdown policing.

But the killing of George Floyd on May 25, and the protests that rippled out from it, further amplified the urgency of finding justice for those killed in South Africa too, says Tumi Moloto. The recent South African graduate of Mt. Holyoke College in Massachusetts, who uses the pronoun they, says they related to what happened in the U.S. because they have experienced the realities of being policed as a black person in both countries.

“We can and we should be outraged for both the United States and for ourselves,” they say. “It’s not either/or. We can hold both those things in our conscience.”

For many, though, justice still feels a long way off. Mr. Steyl says the Khosa family will challenge the defense forces’ findings in court. Activists, meanwhile, say they hope they can sustain the new attention on the case of Mr. Khosa – as well as the other killings and a series of violent evictions during lockdown.

On Monday, demonstrators led by the Economic Freedom Fighters, a leftist opposition party in South Africa, marched to the U.S. Consulate in Johannesburg, where they sang a traditional anti-apartheid folk song called “Senzeni Na?” or “What Have I Done?”

What have we done?

Our sin is that we are black?

Our sin is the truth.

They are killing us.

Essay

Horrified by strife in my America, finding hope in my Mideast

Here’s another perspective piece: For the Monitor’s Chicago-born Arab world correspondent, the view homeward of roiling strife and demands for justice has been both disorienting and familiar. His experience has taught him to hope.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Chants for social justice fill the air, as does the faint bitter-sour smell of tear gas. My calves twitch, ready to move. Police rush in from every direction. The clubs rain down. This isn’t Minneapolis. This is Cairo. This is Amman.

I covered dozens of such protests across the region. Now I see these images replay in my hometown of Chicago. It’s as if my memories have been jumbled and reassembled, like a puzzle gone wrong.

During the 2011 Arab Spring, the American government was a voice of restraint. But what happens when that voice is silent? What happens when the chaos comes home? Separated by thousands of miles and COVID-19 restrictions, I can only witness. My solace is I have also lived the aftermath. And there is good to be found.

Across the Middle East, a new generation infused with the culture of protests and speaking truth to power has come of age. While paranoid strongmen build up their arsenals, young Arabs have been armed with the knowledge that true power is people power.

I hold these lessons close: People band together. Social rifts heal. Divisions can’t destroy decency. Kindness cannot be killed.

Horrified by strife in my America, finding hope in my Mideast

I still feel every second. Visored, armor-clad police form a wall, riot shields up, clubs in hand, their faces barely visible. The faint bitter-sour smell of tear gas hangs in the air.

My calves twitch, ready to move in either direction, not knowing where the battle lines lie, how close is too close. The police move a few steps forward; the crowd rushes back a few strides, before boldly inching back to hold its ground.

Chants for social justice fill the air, but in the back of all our minds are questions: Who will stand down, who will flinch, who will cross the line, who will get hit? Who will not return home tonight?

Suddenly tear gas is fired. The police rush in through the smoke from every direction. Chants turn to screams. It is now a scramble to get out in one piece. Journalists hold up press cards – yell “media!” – but the clubs rain down.

This isn’t Minneapolis, Atlanta, or Detroit. This is Cairo, this is Amman. Nearly a decade ago and for a different cause, millions of young people protested for justice and freedoms across the Arab world, going up against a militarized police force with lives at stake.

I covered dozens of such protests in cities and villages across the region. Some were peaceful, some turned violent, but all featured the same potent mix of hope, anger, and uncertainty about how it would all end.

Now I see these images replay in my hometown of Chicago: clashes in the Loop, State Street scuffles, pandemonium on the North Side. Armored vehicles like those used to clear out Cairo’s Tahrir Square rolling down Michigan Avenue and the Eisenhower.

It is as if my life’s memories have been jumbled and reassembled, replacing the backdrops of the Mideast capitals I lived in with the streets where I am from. Like a puzzle gone wrong.

During the 2011 Arab Spring, the American government was a voice of restraint, championing the right to peaceful protest for justice and democracy. Warnings from the U.S. president himself against the use of force against protesters stopped many Arab leaders from escalating violence further and transforming their cities into “battle spaces.”

There was a cause and effect to our work as journalists; the abuses by police forces that we documented led to condemnations from Western governments, rattling Arab regimes that rely on Western aid.

Sure, I took my lumps: a club to the back of the neck, a rock to the head, an errant machete grazing my leg. I still bear a mark on my shoulder from when an entire barbecue grill was thrown at me. But we could count on America’s voice to pull us back from the brink.

But what happens when that voice – the United States government’s – is either silent or, instead, fanning the flames?

What happens when America’s democratic norms shatter, divisions deepen, and age-old racial inequalities and racist impulses intensify? What happens when the chaos comes home?

Separated by thousands of miles of ocean, COVID-19 restrictions, and shuttered airports, I cannot be with my hometown community. I cannot support my grieving and enraged homeland the way I have done in foreign lands. All I can do is witness.

If I am stuck reliving times of turmoil, perhaps my solace is that I have also lived the aftermath. And it’s not all bad. In fact, there is good to be found.

Years before “silence is compliance” became a protest chant, the U.S. government fell silent on injustices in this part of the world.

As America diplomatically retreated from the Mideast, Arab strongmen gained the upper hand. Militarized police became even more militarized; protests were crushed with deadly force; leaders passed anti-terror laws marking anyone who dares to speak out or criticize their government a “terrorist.”

But something else happened, too. People banded together.

As authoritarians tightened their grip, polarization subsided; rifts among Islamists, secular citizens, and regional tribes healed. I watched people of different faiths and political stripes rally around one another for civil liberties, jobs, and a better future for their children.

Neighbors and strangers relied on each other because no government or political movement was coming to save them.

Activism lived on in acts of kindness. Less than a decade after the Arab Spring, a new generation infused with the culture of protests and speaking truth to power has come of age, rising up in Sudan, in Iraq, in Algeria, in Lebanon.

While paranoid strongmen build up arsenals of tanks and guns, an entire generation of young Arabs has been armed with the knowledge: True power is people power.

I hold these lessons close now: Divisions can’t destroy decency, good neighbors don’t stay divided, kindness cannot be killed. Even in darkness, communities find one another. And progress can be derailed, but not erased – no matter who or what stands in the way.

Comic Debrief

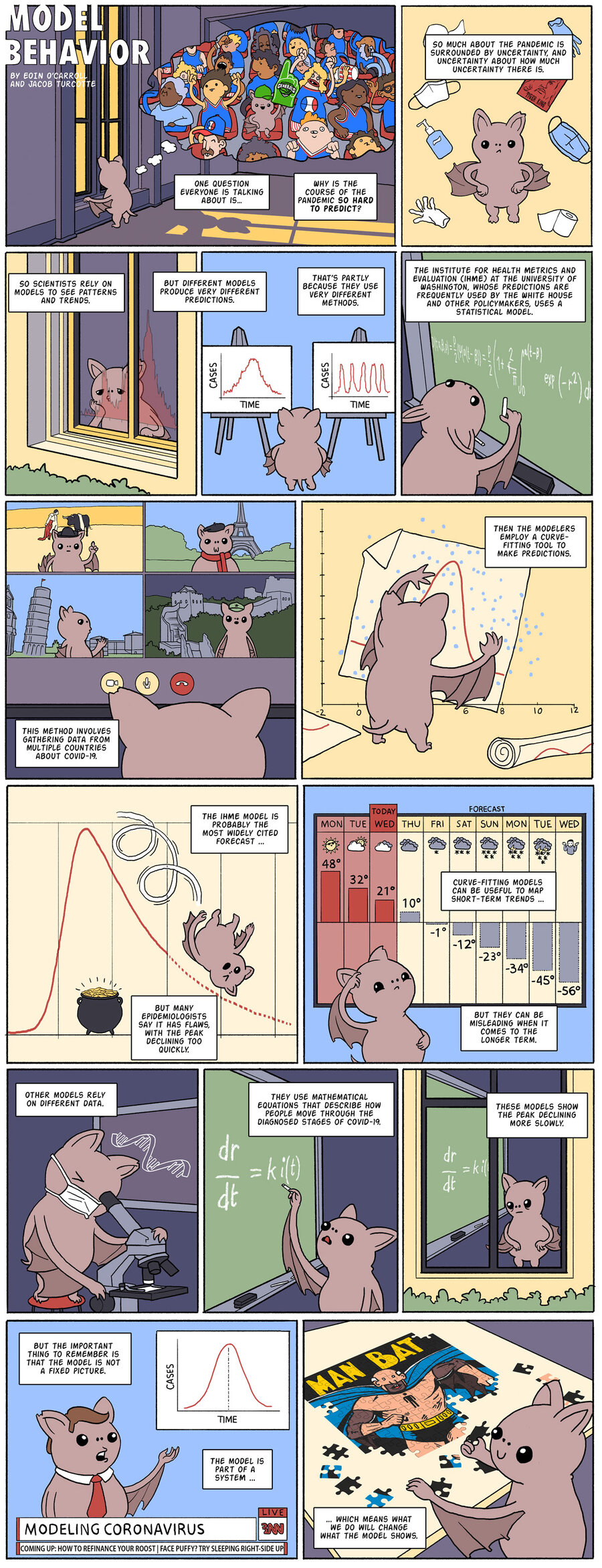

Why coronavirus modeling is so hard to pin down

Finally, however you feel about math, you might enjoy this. To look at how scientists use mathematical equations to offer some paths forward on the coronavirus, we reached for a storytelling tool with which we’ve been experimenting: illustrated panels.

Why is the course of the COVID-19 pandemic so hard to predict? Public health modeling is complex, and there are many ways to go about it.

The most well-known model is built by the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). That model predicts that COVID-19 cases in the United States will steadily decline over the summer, approaching zero in August.

The IHME model uses a technique called “curve fitting” in which researchers try to find patterns from previous COVID-19 outbreaks in other countries and apply them to current ones. But many observers have called this model too optimistic.

Other models rely more heavily on epidemiological knowledge. They make predictions using mathematical equations that model how diseases are thought to spread through populations. These models predict that the peak will decline more slowly.

Part of the reason these kinds of predictions are so hard is that the model changes according to how we react to it. If a dire outlook prompts us to take stricter measures, then it might, in virtue of its own predictions, become less accurate. That’s because you are part of the system. – Eoin O'Carroll, staff writer

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Bring back youth sports better than before

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Since March, when the United States went into lockdown, youth sports have been in a big timeout. The pandemic forced organized leagues to shut down. While some are resuming, in much of the U.S. they’re not likely to reappear until late summer, if then. Can any good come from this lost time for team sports? It could.

The Aspen Institute’s Project Play suggests a number of ways organized sports could be extended to more disadvantaged youths. They include creating more local leagues that place fewer demands on families than travel teams. In Tacoma, Washington, for example, enrollment in the city’s youth soccer league rose from 256 children in 2015 to 1,400 this year, a 450% increase. The secret: The programs now take place at local elementary schools, most within walking distance for children. That means parents aren’t needed to drive kids to every game or practice.

The rewards of youth sports are too great to not seize this opportunity to improve them.

Bring back youth sports better than before

Since March, when the United States and other countries went into lockdown, youth sports have been in a big timeout. The pandemic forced organized leagues to shut down. While some are resuming, in much of the U.S. they’re not likely to reappear until late summer, if then.

Can any good come from this lost spring and summer for team sports? It could.

It starts with recognizing what happened in their absence: Children have played catch with their parents or created informal soccer fields in their backyards. Families rode bikes together.

Such less-organized activities, it turns out, can be just as good for kids beyond the sheer fun. But that is no surprise: Children always have the ability to play – and find outlets for it.

The hiatus for team sports also provides an opportunity to ask a question: How could they better serve children and teens? And how can their benefits reach more children?

So-called youth travel teams, which offer competition at an elite level and prepare youths to excel in a particular sport, such as baseball, are expected to be among the last to return. They involve transporting youths long distances, sometimes to other states, where they come into contact with a whole new group of other youths and related adults.

These teams can be great for young athletes who want to push themselves to the limit. But they also are expensive, in some cases costing families thousands of dollars in fees, equipment, and travel expenses each year. These high costs often limit who is able to participate.

In general, families spent an average of $693 annually per child for each organized sport they play, according to Utah State University’s Families in Sport Lab. And in many families, each child may play two or more sports each year.

More troubling is the income gap between families whose children play organized sports and those who don’t. It keeps widening.

In 2012, about 24% of families with incomes of less than $25,000 per year reported their children engaged in no sports activity at all, according to the Aspen Institute, which studies youth sports. By 2018, that percentage had risen to 33.4%.

In contrast, in 2012 only 14.4% of families with incomes over $100,000 reported their children engaged in no sports activity. By 2018, that figure had shrunk to 9.9%, further widening the gap.

The Aspen Institute’s Project Play suggests a number of ways organized sports could be extended to more youths. They include creating more local in-town leagues that place fewer demands on families than travel teams.

In Tacoma, Washington, for example, enrollment in the city’s youth soccer league rose from 256 children in 2015 to 1,400 this year, a 450% increase. The secret: The programs now take place at the 36 local elementary schools, most within walking distance for children. That means parents aren’t needed to drive kids to every game or practice.

The most important consideration, perhaps, is remembering that sports should be a source of joy.

“Children will be life-long lovers of sport if they are allowed to have fun,” says one parent in a recent Aspen Institute report on the state of youth sports.

Through sports children and teens break barriers of limitation. They gain self-confidence as they master new physical skills. They make new friends and learn the value of working as a team.

The rewards of youth sports are too great to not seize this opportunity to improve them.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Healed at the Annual Meeting of The Mother Church

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Maryann McKay

Each year The First Church of Christ, Scientist, has an Annual Meeting attended by members from around the world (this year’s was entirely virtual). Here’s a woman’s account of a meaningful healing she experienced during Annual Meeting activities some years ago.

Healed at the Annual Meeting of The Mother Church

I am so grateful for the many healings and demonstrations of God’s power I have seen and experienced through my study and practice of Christian Science. The healing I would like to share in this testimony was instantaneous and shows that individuals attending Christian Science services and meetings do experience healing.

For several years, I tolerated occasional bouts of nausea, which lasted only a few seconds. Because the episodes came and went so quickly, I would forget about them until the next bout. As a result, I didn’t specifically pray to be healed of this problem, although I knew it did not come from a loving God and had no divine law to support it.

One year I had the opportunity to attend the Annual Meeting of The Mother Church, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston, Massachusetts. At this event, members from around the world come together to listen to church reports and share healing ideas and progress. I felt very inspired and grateful for all that I heard over several days and for the genuine, universal love that was expressed. My thought was greatly uplifted by the sharing of so many spiritual truths.

As I was waiting quietly for an evening session to start, once again I felt the nausea. But this time was different. I heard in my thought a very loud, authoritative voice saying, “No!” The rebuke was so firm it startled me. It was reminiscent of a statement in the Christian Science textbook: “The inaudible voice of Truth is, to the human mind, ‘as when a lion roareth’ ” (Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 559).

That was the end of the chronic nausea, and that was decades ago.

This healing was an opportunity to witness the Christ, Truth, in action, rebuking the error of belief in a condition God never made or allowed. Once I had witnessed this, the condition could no longer continue to be manifested in my experience. A beloved verse from the “Christian Science Hymnal” describes this experience: “The Christ is here, all dreams of error breaking,/ Unloosing bonds of all captivity” (Rosa M. Turner, Hymn 412).

The error of belief in nausea simply could not stand before the presence of God and His healing Christ. Mrs. Eddy, the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science, writes in Science and Health, “Error is a coward before Truth” (p. 368). When the voice of Truth thundered, the cowardly error vanished.

We can and should expect healings at Sunday church services, Wednesday evening testimony meetings, Christian Science association meetings, Christian Science lectures, and especially the Annual Meeting of The Mother Church, where we go not only to learn more about God and His idea, man, but also to give immense gratitude for our beloved Leader, Mary Baker Eddy, and for the worldwide Christian Science movement.

A message of love

A nation mourns

A look ahead

Come back tomorrow. We’ll have a reflection on protests and riots from a man who was a college student during the Rodney King unrest and has intimate knowledge of what it’s like to face off with police.

Also, a reminder: You can now find some of the fast-moving stories that we’re watching right here.