- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Shaky COVID response lays bare a decadeslong crisis in government

- Young Saudis saw a future; then came a pandemic and an oil crash

- As lockdown lingers, a rural reckoning with domestic violence

- If a Black voice rises in a white neighborhood, does it make a sound?

- On stories of Black struggle, an iconic L.A. bookstore surges

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Why we’re capitalizing Black

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Those of you who opened Friday’s issue of The Christian Science Monitor Daily will have glimpsed Ken Makin’s column. From the 1870s to today, it charts the efforts of African American leaders to demand the word “Black” be capitalized.

There are a variety of arguments, but Ken focuses on the one that matters most: Language is not simply a collection of grammatical rules; it conveys how we see the world.

To many in white America, “black” might seem simply a modifier – a description of color. To many African Americans, the word “Black” is a declaration of defiance – an insistence on the humanity and value of a community that too often has been made to feel like strangers in their own country. “The capitalization of the ‘B’ in Black when it comes to race is a cultural, political, and spiritual act,” Ken writes. “It gives power to the idea of being Black in opposition to and defiance of white supremacy and a white-dominated society.”

The power of recent weeks has been the demand to listen humbly – the Monitor included. So after considering the decision from different perspectives, the Monitor is now capitalizing Black. The goal is not to value one race over another, but the opposite. In better cherishing the Black experience in America, we recognize its unique role and seek firmer footing for genuine equality and freedom.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Shaky COVID response lays bare a decadeslong crisis in government

A highly politicized system that encourages short-term thinking has hindered America's pandemic response. Outmoded technology, overlapping mandates, and low public trust have contributed, too.

Some of the early steps taken by the Trump administration to address the pandemic have been widely applauded, from the president’s decision to ban flights from China to his initial support for states’ shutdowns.

But other aspects of the response have met with harsh criticism. The U.S. government had been warned in early January about the virus, and should have been better prepared, many public health experts say. When it arrived on U.S. soil, a combination of conflicting messages and a lack of a clear leadership structure delayed the adoption of practices to contain the spread.

Now, as the nation’s economy slowly reopens, with cases beginning to pick up again in at least 20 states, a larger question hangs over the crisis: Is America’s system of government itself simply too outmoded – too partisan, and ill-equipped to keep up with the pace of global change – to capably handle a once-in-a-century pandemic?

“We have a legacy government that hasn’t kept up with the world around it,” says Max Stier, president and CEO of the nonpartisan Partnership for Public Service. “This is a long-standing problem, but it creates more impact when something really bad happens.”

Shaky COVID response lays bare a decadeslong crisis in government

Days before Donald Trump became president, Obama administration officials hosted a “tabletop exercise” for the incoming Trump team. One of the hypothetical challenges: dealing with a novel strain of influenza that was sweeping the globe.

Cases were appearing in California and Texas, according to the simulation. It could be the worst flu pandemic since 1918. There would be shortages of essential equipment like ventilators. A “whole of government” response would be needed.

Some 30 Trump appointees attended the meeting. Today, only eight still work for the president, according to a Brookings Institution tally.

In the rearview mirror, of course, everything can look crystal clear. As President Trump’s former spokesman, Sean Spicer, who attended that January 2017 tabletop exercise, said: “There’s no briefing that can prepare you for a worldwide pandemic.”

Some federal actions have been widely applauded. Mr. Trump’s decision in late January to ban flights from China is one. The president’s initial support for states’ economic shutdowns – and his signing of emergency legislation providing payments to individuals and businesses in an effort to prevent an economic collapse – wins praise even from some critics.

But other aspects of the Trump administration’s early pandemic response have met with harsh pushback. The U.S. government had been warned in early January of the deadly new virus in China, and should have been better prepared for its arrival on American soil, critics say. When it did arrive, a combination of conflicting messages and a lack of a clear leadership structure delayed the adoption of safe practices to contain the spread, they add.

Even allies of President Trump take issue with aspects of the federal government’s response. “There will be 600-page books on the mistakes that were made,” says conservative economist Stephen Moore, an informal adviser to the president.

Much has been made of the turnover and turmoil of the Trump presidency – including the 2018 closure of the White House office on global biothreats.

But as the nation’s economy slowly reopens, with cases beginning to pick up again in at least 20 states, and the U.S. death toll now over 115,000 and rising – the highest tally in the world – a larger question hangs over the crisis: Is America’s complex, multilayered system of government itself simply too outmoded – too cumbersome, overly partisan, ill-equipped to keep up with the pace of global change – to capably handle a once-in-a-century pandemic?

In other words, despite all the stumbles of the Trump team, would another administration necessarily have done all that much better?

“We have a legacy government that hasn’t kept up with the world around it,” says Max Stier, president and CEO of the nonpartisan Partnership for Public Service. “This is a long-standing problem, but it creates more impact when something really bad happens.”

History repeating itself

In the perpetual battle to protect the nation from biological threats, Kenneth Bernard has seen history repeat itself over and over.

Under former President Bill Clinton, Dr. Bernard ran the National Security Council’s office on global health threats, only to see it close when President George W. Bush took office. In late 2001, after anthrax-laced letters were sent to people in 17 states, Dr. Bernard was brought in to reopen the office.

President Barack Obama closed the office and then reopened it when Ebola struck. In 2018, President Trump’s new national security adviser, John Bolton, closed it again, though administration officials say its “medical health preparedness” functions were kept in other parts of the National Security Council.

A Washington Post fact-check article examining whether the 2018 closing of the NSC biothreats office hampered the Trump administration’s early response to the coronavirus came to no firm conclusion.

But the early days of the pandemic were obviously key. While American governance is by design decentralized, with many decisions left up to the states, the White House plays an essential coordinating role, says Dr. Bernard, an epidemiologist and retired rear admiral in the U.S. Public Health Service.

“A truly critical pandemic like this, where it affects everyone’s life in America, is by its very nature a federal national problem,” says Dr. Bernard. “What you’re looking for from the White House is leadership.”

The first head of the White House Coronavirus Task Force was the secretary of health and human services, Alex Azar. But that assignment was inappropriate, says Dr. Bernard, because the HHS secretary has no ability to coordinate departments like State, Treasury, and Defense.

By late February, Vice President Mike Pence was put in charge of the task force. But in the modern era, the vice president fulfills broad functions, and thus is ill-equipped to operate as a full-time “czar” on a major health emergency, Dr. Bernard says.

A more effective option, he adds, would have been for the president to appoint a special presidential assistant who focuses solely on the pandemic – someone who can coordinate all the necessary agencies as the anointed presidential representative, as Ron Klain did for President Obama during Ebola.

One of the most eye-opening aspects of the federal response to COVID-19 has been the apparent sidelining of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta. Its early test kits for COVID-19 didn’t work. The CDC director, a virologist named Robert Redfield, has not played a major role in public messaging. Technology problems hindered timely collection of data in the early days of the pandemic, as Americans streamed back into the United States from overseas.

Problems at the CDC predate Dr. Redfield. The agency, once looked to as a global leader on public health, has long been hampered by antiquated technology and a slow-moving bureaucracy that’s particularly ill-equipped to handle a fast-moving crisis.

“The CDC is the poster child for an undermined, under-engaged workforce,” says Paul Light, a professor of public service at New York University.

Add to this picture an administration with conflicted views toward science and deep angst about the damage done to a once-vibrant economy.

“There are legitimate areas where you have to balance the economy and public health,” says James Curran, dean of the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University in Atlanta and a former longtime CDC official. “We just need to get all the public health facts out, interpreted by the very best minds we have, and if they don’t always do the job, the answer isn’t to shut out the agencies. The answer is to make them better.”

Some Trump allies now believe the economic shutdowns were a huge mistake.

“The economic costs and the costs of human suffering caused by this lockdown have been multiple times greater than any benefit,” says Mr. Moore.

Mr. Moore thinks “we could have been much smarter” – limiting lockdowns to the most at-risk areas and populations like nursing homes. He also faults both parties in Congress for making it more lucrative for unemployed people not to work than to work.

But he doesn’t blame Mr. Trump.

“There was just a sense of total crisis and fear,” he says. “I don’t think the president had any other choice.”

A highly politicized system

When crisis hits, conservatives say, the “mission creep” that besets bureaucracies is most evident. Multiple agencies with overlapping agendas can conflict with each other, such as the CDC, National Institutes of Health, and the Food and Drug Administration.

“It’s axiomatic that an overly bureaucratized government response to anything is going to be a challenge,” says Charmaine Yoest, co-executive director of the conservative Heritage Foundation’s National Coronavirus Recovery Commission.

But challenges to effective governance today are not just in the executive branch; they’re also in Congress and even the for-profit private sector. And they start with a system that is highly politicized and encourages short-term thinking.

One example: Cabinet departments and other federal agencies are topped by some 4,000 political appointees, and out of those, some 1,200 are Senate-confirmed.

“No other democracy has anything close to that level of political infiltration in the institution of the government,” Mr. Stier says.

That, in turn, results in a top echelon of leaders who don’t necessarily know what they’re doing, he says.

In Congress, hyper-partisanship has led to dysfunction in budget-setting, leading the government to run increasingly on a form of funding autopilot known as “continuing resolutions,” punctuated more and more by government shutdowns. Oversight can be ineffective or nonexistent; Senate confirmations slow.

Adding to the challenge is a half-century decline of public trust in the federal government, as charted by the Pew Research Center. For decades, presidential rhetoric and scandals have made Americans increasingly cynical about government and wary of its messages.

But few presidents over the years have been willing to invest the political capital needed to make major governmental reforms.

“We haven’t had a major reorganization of government in decades,” says Professor Light. “It just ain’t sexy.”

Through the decades, Mr. Light has watched history repeat itself many times. Between 2000 and 2015 alone, he counts 48 breakdowns in federal governance, including the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and the botched rollout of the “Obamacare” insurance website in 2013.

The details vary from crisis to crisis, but Mr. Light keeps coming to the same conclusion: We keep having breakdowns, because “we just don’t pay much attention to how organizations work.”

Early in his presidency, Mr. Trump assigned senior adviser and son-in-law Jared Kushner to overhaul the federal bureaucracy by applying business principles, but the initiative appears to have stalled.

Historically, significant government reorganizations are rare. Former President Herbert Hoover ran major commissions on reform in the 1940s and ’50s. Efforts by President Jimmy Carter in the 1970s had less impact. In the 1990s, President Clinton tasked his vice president, Al Gore, with “reinventing government,” an effort that reduced the size of the federal workforce by 300,000 people. The 9/11 attacks led to creation of the Department of Homeland Security.

The Clinton-Gore effort reflected a bipartisan consensus – now defunct – that “big government” was a problem. The technology revolution undergirded the reforms.

President Clinton felt that “if Democrats wanted to have an activist government, you had to first convince people that government could work efficiently and take care of their tax dollars,” says Elaine Kamarck, who managed the initiative.

Unique strengths and weaknesses

Dr. Curran of Emory University sees unique strengths and weaknesses in the U.S. as it faces down COVID-19.

“We’re the wealthiest country in the world, but we also have some of the greatest health disparities,” Dr. Curran says. “And we have the most disorganized health financing system of any major country.”

The U.S. doesn’t have a national health service, and the entire health community can’t be mobilized to do whatever the government wants. The American public health system is also poorly understood. Yet the U.S. is seen as having some of the best hospitals, specialists, and researchers in the world.

These paradoxes can be maddening, but they can also be sources of hope. There’s plenty to build on.

In a public health crisis, “assessment and surveillance are a key government responsibility, as is interpretation of the surveillance,” says Dr. Curran, referring to the painstaking collection of data about caseloads. “We’re starting to see more of that from the CDC than we did.”

Dr. Curran sees the current turmoil as an opportunity to think about how the functions of government can be improved to meet public needs.

“We’re not going to reform totally our federalist system, but we should think about that, too,” he says. “What are the national responsibilities versus the state responsibilities? And that’s not just about health; it’s related to everything else.”

Ms. Kamarck, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, has already mapped out three proposals for government reform, post-pandemic. All three, she says, are things the military already does routinely: (1) better scenario planning for potential crises; (2) building more “surge capacity” in personnel to deal with such crises; and (3) applying dual-use principles to health care technology.

“None of this will happen without competent leadership,” she adds.

It’s worth noting that despite all the breakdowns in governance, there are agencies and employees who make “miracles” happen every day, says Mr. Light.

Take Beth Ripley, a Veterans Health Administration radiologist in Seattle. When the coronavirus crisis first hit, Dr. Ripley swung into action. She had already developed a network throughout the VA that uses 3D printing to help surgeons. By late March, as the need for personal protective equipment soared, Dr. Ripley had pulled together three federal agencies – the VA, the Food and Drug Administration, and the National Institutes of Health – to rapidly boost stocks of PPE via 3D technology.

By mid-April, through a quickly organized public-private partnership, face shields and masks suitable for medical personnel had already been designed and were being tested.

It’s the kind of government success story – demonstrating ingenuity, collaboration, and speed – that could turn a cynic into a believer. Now she’s a finalist for a “Sammie,” the annual awards by the Partnership for Public Service honoring outstanding federal employees.

Mr. Stier, the partnership president, clearly relishes talking about the good news in government at a time of historic challenge. “There are many examples,” he says, “where people can creatively achieve impact in the government.”

Young Saudis saw a future; then came a pandemic and an oil crash

Saudi Arabia was moving toward a future of more freedoms and less reliance on oil. Then, the pandemic hit and the difficulty of making those shifts has become plainer.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman was just beginning to realize an ambitious vision to use oil revenues to create a post-oil economy in Saudi Arabia. It was a plan that promised young Saudis a bright future that included new freedoms and opportunities. Thousands were trained in hospitality and IT; innovation hubs were launched; airports and gleaming financial districts were built.

“We felt like we were helping Saudi Arabia to join and lead in the 21st century, we felt like we were making our home a better place,” says Amira, a Riyadh entrepreneur. “Suddenly our nationality meant allegiance to something bigger than ourselves.”

But oil prices crashed as the coronavirus spread. Financial districts are deserted, tourism development and promotions shelved. To weather the storm, a new austerity has been imposed, and more is being asked of young Saudis. Taxes have gone up, and subsidies have been slashed.

With the crown prince’s vision in doubt, some young Saudis are suddenly questioning their place in society. Mohammed, an IT specialist, left his job in London to work as a consultant in Riyadh. “I don’t know which Saudi I live in anymore,” he says.

Young Saudis saw a future; then came a pandemic and an oil crash

For Mohammed, like many Saudis, the “good old days” were only just beginning.

The nation’s de facto ruler, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, was promising – and delivering – almost anything a young Saudi could ask for: social freedoms, cultural events, tech hubs, women’s advancement, art galleries, free university, jobs.

Like many young Saudis, Mohammed – he requested that his full name not be used so that he may speak freely – was lured back home from abroad by the crown prince’s government to achieve a shared vision: transform Saudi Arabia from a kingdom reliant on oil to an open, modern, tech-savvy state.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

The 28-year-old IT specialist left his job at a London firm to work as a consultant in Riyadh, and soon started living a life not too dissimilar to the one he had abroad.

“This was a chance for us to build the society and lives we wanted at home rather than pursue it elsewhere,” Mohammed says.

But after the triple crises of the pandemic, the collapse of crude oil prices, and falling financial markets, young Saudis are awakening to yet another reality; one of austerity, rising taxes, slashed subsidies, and delayed and canceled projects.

It’s causing economic, and identity, whiplash. Will the crown prince’s promises, and a Saudi identity built on perks and privileges, stand up when the perks are no longer there and their jobs are more demanding?

“I don’t know which Saudi I live in anymore,” Mohammed says.

Austerity

Before the COVID-19 crisis, Crown Prince Mohammed (MBS) was just beginning to realize his ambitious Vision 2030 economic transformation plan, which entails using oil revenues to invest in projects and initiatives, from tourism to artificial intelligence, to create a post-oil economy.

Thousands of young Saudis were trained in tourism, hospitality, and IT; tech start-ups were encouraged; innovation hubs were launched. Brand-new airports and gleaming financial districts were built.

But for now, hotels sit empty, financial districts have been deserted, and tourism development and promotions shelved.

With the Vision in doubt, some young Saudis are suddenly questioning their place in society.

“We were told that if we worked hard and depended on ourselves, we would become Saudi Arabia’s new oil,” says Ali, a 24-year-old from Asir province who after two years as an unemployed engineer – the field suffers from a chronic oversupply of graduates – received free hospitality training by the government.

He was then employed at a Riyadh hotel before the COVID crisis in April put him on furlough.

“If the engines of the economy are being sold or turned off, what use is the oil?” he says.

Adding to the shock are the waves of austerity measures and tax hikes for a population accustomed to cradle-to-grave welfare and still reeling from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Even as many countries introduced bailout packages, Saudi Arabia moved in May to cut a $260 monthly stipend paid to government workers and tripled its value added tax on all goods from 5% to 15%.

Meanwhile, major projects have been frozen, “reprioritized,” or delayed indefinitely.

Finance Minister Mohammed al-Jadaan has billed the steps as a “reallocating” of spending, saying that cutting subsidies, raising taxes, and freezing projects will free up some $26 billion in funds to reinvest elsewhere to support citizens and keep the crown prince’s vision alive.

Officials are touting the new economic plan to weather a COVID-fueled collapse in oil prices. Prices that fell to the single digits have only inched up to $38 a barrel this week, below the $50 per barrel experts say Saudi Arabia needs to avoid running a larger deficit.

The Gulf power is on track for a $50 billion budget deficit; state-owned oil giant ARAMCO is posting a 25% drop in revenues; and the kingdom’s $470 billion in currency reserves have been dwindling at a rate of $20-25 billion a month since February.

Nationalism

Yet questions remain about how citizens will accept the austerity pivot when a key pillar of the Saudi social contract has been the state’s role as a provider.

Underpinning Crown Prince Mohammed’s post-oil vision was a Saudi transformation from a deliberate, slow-moving state that based its legitimacy on religion, tribal relations, and broad regional consensus with its allies across the Arab world.

Instead, MBS has pushed a “Saudi first” campaign, urging citizens to pledge allegiance to a nation that staked out its own path in diplomacy and the economy, inviting them to take part in shaping its future.

MBS’s offer was attractive to many Saudis, 60% of whom are under the age of 30, and hundreds of thousands of whom had studied abroad in the West and wished to see changes at their stuck-in-the-past homeland.

“When many of us began working on the Vision, we felt like we were helping Saudi Arabia to join and lead in the 21st century, we felt like we were making our home a better place,” says Amira, 32, a Riyadh entrepreneur who did not wish to use her full name.

“Suddenly our nationality meant allegiance to something bigger than ourselves.”

Before the pandemic, the palace pushed through minor economic changes, such as cutting fuel and energy subsidies, and reducing government bonuses, while introducing broad social reforms and opening up thousands of job opportunities in emerging fields and more remote parts of the kingdom.

If this new Saudi nationalism has been a two-way street, will Saudis still buy in to this national civic duty when there are no longer any perks to go around?

“We need to have jobs and reasonable prices first in order to be a strong Saudi,” says Amira. “And for some of us we suddenly have neither.”

More expected from citizens

Already, many have been grumbling over changes in a culture that expected more of citizens.

Employed Saudis have chafed at a recent ‘private sector’ approach in state ministries and agencies – the top employers in the kingdom – as CEOS and managers have been imported from the business world to shake up a Saudi work culture that put personal comfort over productivity.

“They want us to work overtime, to log extra hours. ... Our jobs are completely based on our performance every single day, and there is no room to make a mistake,” says Abdulrahman, who works for a government agency.

“They want us to work until we are tired, and these cinemas, concerts, and women in dresses aren’t putting food on the table.”

Even before the COVID-19 crisis, economic experts voiced skepticism over whether many of the crown prince’s Vision 2030 plans – such as a Saudi tech sector – would ever materialize.

Experts agree that the high expectations will be increasingly difficult to meet now that the oil revenues meant to cushion Saudis as the country made its radical transformation are no longer there.

“Many Saudis are poor, it is a young population to whom MBS has given a lot of hopes, and at some point they will want to cash in these checks the crown prince has given them in expectations,” says David Jalilvand, foreign policy analyst and director of Berlin-based Orient Matters.

“There will be a point where Saudi society grows increasingly frustrated with increased taxation, which complicates the ability of [the government] to make needed long-term structural reforms.”

The crisis appears to have cemented the crown prince’s conviction of the need for an economic transformation, but tough questions, and choices, lie ahead.

“When there is taxation without representation, there is a problem. This is political science 101,” says Oraib al-Rantawi, director of the Amman-based Al-Quds Centre for Political Studies.

“In time, citizens in Saudi Arabia will demand either a return back to subsidies, or greater say in political matters, but recent history shows that Saudi Arabia’s rulers will resist either.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

As lockdown lingers, a rural reckoning with domestic violence

Amid the pandemic, activists have been alert for increases in domestic violence, as abusers and their victims are forced into close quarters. The problem appears most acute in rural areas.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Moira Donovan Correspondent

The coronavirus pandemic has catapulted the consequences of isolation and silence toward domestic violence, often compounded in rural contexts, to the fore across North America.

In Canada, the need to act now has been thrown into particularly sharp relief. That is due in part to the aftermath of April’s deadly shooting in Nova Scotia, which left 23 people dead. A former neighbor of the gunman in Portapique recently told the media he had a history of domestic abuse. But it is also due to the realization that the pandemic has locked victimized women and girls worldwide into homes with their abusers.

Many factors increase risks of violence against women; in Canada, indigenous and Black women experience higher rates of domestic violence, for example. So do rural residents. In tightknit, traditional places, where the nearest police station might be a half an hour away, and the closest women’s shelter even farther, escaping abusive relationships can be particularly difficult. Myrna Dawson, a professor at the University of Guelph, in Ontario, says that beliefs such as those dictating more rigid gender roles, and norms around the importance of guns, as well as on-the-ground realities including lack of public transportation, increase the associated risks.

As lockdown lingers, a rural reckoning with domestic violence

Before he perpetrated the worst mass shooting in Canada’s history, the gunman had allegedly inflicted something lamentably more mundane: violence against his partner.

And if Nova Scotia was shocked by the 13-hour rampage through its rural hinterland that resulted in 23 deaths, including the gunman’s, in the middle of a global pandemic, it was less startled when a former neighbor of the gunman in Portapique told the media he had a history of domestic abuse.

That included one incident that she says she reported to police in 2013, in which he is alleged to have beaten and strangled his female partner before three male witnesses. It was not the first incident to be “whispered about” yet not confronted.

“I think sometimes in rural Nova Scotia, there is this culture of not speaking out, of minding your own business, not rocking the boat,” says Johannah Black, the bystander intervention program coordinator with the Antigonish Women’s Resource Centre, a women’s shelter serving two rural counties in Nova Scotia. “That is something that leads to isolation, to not having these discussions, to looking the other way.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

But now Nova Scotia, where blue and green tartan scarves are still fluttering from front porches and mailboxes in grief over the aftermath of the April mass shooting, is being forced to look at domestic violence that has too often been dismissed, or unconsciously accepted. The reckoning comes as the pandemic has catapulted the consequences of isolation and silence toward domestic violence, often compounded in rural contexts, to the fore across North America.

“I think our society is forever changed, I think we all recognize that. COVID has highlighted the complexity of domestic violence,” says Gloria Terry, the CEO of the Texas Council on Family Violence in Austin.

It’s also prompted a scramble, she says, to innovate new services that might help reach rural women from Portapique to the Texas Panhandle long after the last restrictions are lifted. “Three months ago no one thought about doing telehealth approaches, or giving support to survivors through virtual platforming,” Ms. Terry says. “Out of sheer necessity we have equipped ourselves with new tools that can be effective.”

“In a room full of people, and they all turned away”

In Canada, the need to act now has been thrown into particularly sharp relief – both due to the aftermath of the Nova Scotia shooting and the realization that the pandemic has locked victimized women and girls worldwide into homes with their abusers.

For Janet Rhodes, that has meant moving her organization, Domestic Abuse Survivor Help, which connects survivors with mentors who have also experienced violence, online.

With the possibility of in-person meetings in her home province of Saskatchewan off the table, and with the scarcity of services in rural parts of Canada and the United States in mind, Ms. Rhodes is now looking at offering support via Zoom. “We can connect with more people that way,” she says. “So they’re getting that validation that this is not just them, that this is happening to other people.”

It’s a lifeline Ms. Rhodes herself could have used the first time her partner abused her. Early in their relationship in the early 1990s, when seemingly out of nowhere he threw a frying pan at her, she barely had the words to process it.

Later in their relationship, they moved into a small community of Dundurn, Saskatchewan, a tiny grid of streets alongside the highway, in the middle of the vast Canadian prairie. As violence escalated, Ms. Rhodes eventually turned to the only resource available: a list of crisis phone numbers at the front of the phone book.

But she called one only to have a person on the other end of the line tell her she should buy her husband some flowers. “That kept me there for quite a few more years, because I thought, ‘Okay, I’m not doing a good enough job as a wife.’”

Many factors increase risks of violence against women; in Canada, indigenous and Black women experience higher rates of domestic violence, for example. So do rural residents. In tight-knit, traditional places, where the nearest police station might be a half an hour away, and the closest women’s shelter even farther, escaping abusive relationships can be particularly difficult. Myrna Dawson, a professor at the University of Guelph, in Ontario, and director of the Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and Accountability, says that beliefs such as those dictating more rigid gender roles and norms around the importance of guns, as well as on-the-ground realities including lack of public transportation, affordable housing, or support services, increase the associated risks.

Statistics Canada data shows rates of domestic violence are nearly twice as high in rural settings as in urban ones – and where women are more likely to be killed by an intimate partner, especially with a gun. A study in the U.S. showed similar results.

In Ms. Rhodes’s case, she didn’t seek help for years until the stakes were increasingly life-or-death. In 2010, when they moved to a bigger town with a police detachment down the street, she found an opportunity to load her infant son in his stroller and flee to the station. It was only after her husband’s arrest that she realized how many people already knew, or suspected, and had done nothing. “It felt like I was sitting in the middle of a room screaming my head off, in a room full of people, and they all turned away.”

Silence amid the pandemic

In the context of the pandemic, advocates are worried that they aren’t hearing from the most isolated women. In Texas, for example, Ms. Terry says that while many metropolitan domestic abuse hotlines have lit up, in some rural areas they have fallen silent.

Groups are mobilizing to reach victims who might feel that there is no help for them as some shelters have had to reduce capacity to adhere to social distancing. Heather Bellino, CEO of the Texas Advocacy Project (TAP), which provides free legal services for domestic abuse victims, says they are disseminating information about alternatives to help where they can, from urgent care centers to food banks.

“We’re working really hard to get the message to people in the rural communities that even if the number of beds is lowered, it doesn’t mean you should not reach out to your shelter, because many have now struck deals with hoteliers,” she says, “because we know the number of survivors or people that are being hurt has not decreased.”

In Nova Scotia, Ms. Black has focused on creating written resources to help bystanders intervene during the pandemic, with measures such as agreeing on a safe word that friends or family members can use over the phone to indicate if they’re in danger. “For me what’s hopeful is when I’m contacted by various survivors ... who are telling me that something like this would have made a difference for them in the past.”

But these measures alone won’t address the problem of domestic violence, she says, noting that deeper societal change is necessary. Ms. Black and others have called for a feminist inquiry into the massacre – set off after the gunman assaulted his long-term girlfriend and bound her up until she freed herself and ran into the woods. The case in Nova Scotia may be extreme, but it’s part of a culture and attitudes that normalized the gunman’s behaviors leading up to it, they say.

“These perpetrators represent the extreme end of a continuum of attitudes and beliefs held by the general public – particularly men – that facilitate and maintain violence against women and girls as normal and acceptable in some contexts,” Professor Dawson says.

“You can come and live with us, now”

Cary Ryan supports the feminist inquiry. As a survivor of intimate partner violence herself, she knows the fundamental role that society at large plays. She has been working with a research project with Nancy Ross, a professor in the School of Social Work at Dalhousie University in Halifax, on the effects of “pro-arrest” policies in Canada.

Under pro-arrest policies, police arrest suspected perpetrators of domestic violence, even if victims don’t want to proceed with charges. The intention of such an approach is to show zero tolerance for domestic violence.

But Professor Ross and Ms. Ryan’s work is showing that pro-arrest policies can have negative consequences for marginalized groups, including indigenous and non-white individuals, and can backfire in rural contexts. Research on similar policies in U.S. states has demonstrated comparable consequences. They say it is communities themselves that need to stop tolerating domestic violence.

A decade ago, Ms. Ryan was living in a rural part of British Columbia with a partner, who was also one of two police officers in town.

Ms. Ryan was socially isolated – they’d moved there for his job – and the relationship was abusive. When she finally decided she needed to leave, she reached out to the only person in town she knew. “They said, ‘You can come and live with us, now.’ These were complete strangers.”

The fact that the community rallied around her – and rejected her former partner – helped her heal. “I was able to hold my head high after all I’d been through in that small community.”

In Ms. Ryan’s case, the dynamics that can increase the risks of domestic violence in rural communities – the isolation and the smallness – may have saved her, as people came forward offering help and belonging. “I know that that wouldn’t have happened in an urban area,” she says. “People came and stood with me and believed me.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated to correct the photo caption.

For more information about how to get help with domestic abuse, please visit these websites:

Nova Scotia resources on intimate partner violence

Essay

If a Black voice rises in a white neighborhood, does it make a sound?

While many Black Americans struggle with hopelessness, columnist Natasha Lewin urges hope, because ”who wants to live in a world where change cannot be fathomed?”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Natasha Lewin Correspondent

I did not want to move here eight years ago. It was my parents, visiting me from Chicago, who fell in love with my quaint Los Angeles town with its walkable business district. Here, they saw a clean, safe, and, what we once thought, liberal neighborhood.

Shortly after my family settled in, LA’s homeless population skyrocketed. Seeing a lack of resolve, ingenuity, or respect for the issue, I decided to run for neighborhood council, and won.

My hopes of leading my Hollywood-adjacent community to make LA history by becoming the first “woke” neighborhood to build supportive housing for homeless families came crashing down in the face of NIMBY-ism. I did not seek reelection.

Fast forward not too many years later, and my community – and all of America – is at another impasse. Now I’m fighting new NIMBY-isms ranging from signs declaring “all lives matter” to annoyed smirks and disgusted body language during a peaceful Black Lives Matter protest.

I’ve thought about uprooting myself but I still believe change is possible. I can still hear the distant sounds of progress – even if so many don’t.

If a Black voice rises in a white neighborhood, does it make a sound?

In the vast landscape that is Greater Los Angeles, somewhere nestled between the former John Birch Society recruiting ground of Huntington Beach and the conservative cop-land of Simi Valley, lies my neighborhood. During the late 1930s, when most parts of Los Angeles were being redlined for Latino, Black, and Jewish Americans, my community was populated by legendary actors Frank Sinatra, Bob Hope, and Bing Crosby.

Ronald and Nancy Reagan hosted their wedding reception here. A man-made lake – inaccessible to the public – hides behind single-family homes big enough to fit two, sometimes three, families spaciously. A private golf course butts up against us. A local weatherman is our honorary mayor.

In 2008, the Los Angeles Times reported a 72%-plus white population in my community. Which, as they put it, was “high for the county.” Twelve years later, we are still an overwhelming majority-white town. But there are also many Black residents. I know, because I am one of them.

When I first moved to the neighborhood eight years ago, I did not want to live here. I craved the diversity and beaches of LA’s Westside. It was my parents, visiting from my hometown outside Chicago, who fell in love with this place and its quaint, walkable business district. At the time, this community was removed from the tent and makeshift-shelter population surrounding the Venice bungalow I wanted. Here, they saw a clean, safe, and, what we once thought, liberal neighborhood.

Shortly after I settled in, LA’s homeless population skyrocketed. As the numbers of homeless people rose, so did the population of Black folks on the street. In 2019, Skid Row, home to one of the largest homeless encampments in the nation, had the unintentional honor of becoming one of the top 10 Blackest neighborhoods in LA with a racial makeup of almost 60% African American.

Around this time, I received a newsletter from my neighborhood council advertising a town meeting regarding the hotly debated topic of homelessness. I was the only Black person in attendance – including those seated on the elected neighborhood council.

The public discussion quickly turned ugly. One neighbor demanded to know how Beverly Hills – a municipality separate from LA – was so successful in keeping homeless people out. Another inquired if our community could, too, hire private security companies or bus homeless individuals away. Seeing a lack of resolve, ingenuity, or respect for the issue from members of the community and its representatives I decided to run for election myself.

After I was seated on my neighborhood council, I hit the ground running. I became a homeless liaison to LA Mayor Eric Garcetti, campaigned for affordable housing, and advocated for Skid Row in their fight for neighborhood council status (they lost twice). To further highlight the disparity for my neighbors, I fought for our community to host our own Homeless Count. I hosted a town hall with LA activists, politicians, and policymakers on why supportive housing in our area was crucial.

The way I romanticized it, my Hollywood-adjacent community could make LA history by becoming the first “woke” neighborhood to build supportive housing for homeless families. Unfortunately, that all came crashing down when I learned one very hard lesson: Not only does NIMBY-ism exist, but “Hollywood adjacent” does not mean progressive – or inclusionary.

As of 2020, there are more than 66,000 displaced people living in Los Angeles County, and 21,509 of those people are Black. One third of those experiencing homelessness are Black in a county where only 8% of residents are Black. The data is soul crushing. Ninety years later and redlining is still coursing through LA veins. I did not seek reelection.

Fast forward not too many years later, and now my community – and all of America – is at another impasse, this time regarding Black lives specifically. Now I’m fighting a new NIMBY-ism as a beloved local business has erected a large, vague sign alluding to all lives mattering. Our newly seated neighborhood council newsletter has no mention of Black lives or our protests – even though some marches are only a few blocks away. The latest issue of our local magazine not only features no Black people in its roundup of neighbors adjusting to quarantine, but, as of today, its website’s homepage hosts more dog photos than it does Black faces.

While everyone from my car dealership to my gym and yoga studio have issued statements affirming the importance of Black lives, I’ve become a thorn in the side of those in charge, writing letters, demanding to be seen in my own community. In response to my neighbors’ silence, two weeks ago I put together a small march down our busy main drag to remind myself that not only do Black lives matter, but we live, work, and spend our money here, too.

It’s taken years of experience and my own light skin – as the biracial singer Halsey calls it, “white-passing privilege” – to teach me how to read people. During our peaceful protest, I could not help but notice the annoyed smirks, disgusted body language, and lack of eye contact from many of my white neighbors as they assessed our potential threat to their comfortable existence. Their fear felt like a mirror reflection of my own and my parents’, who were convinced I would be killed by an enraged white supremacist or angry LAPD officer upset with our nonviolent protest.

I was born to a Jewish Holocaust survivor and a Black descendant of one of the first farms settled by freed slaves in America. After fleeing Europe and serving in the U.S. Army, my father worked his way up the since-dissolved Immigration and Naturalization Service, helping, instead of imprisoning, immigrants and refugees, like he himself once was. My mother ran her own business plus her family farm. There is a reason I was created from these two people. I do not take my gifts of being both Black and Jewish in vain.

My folks’ concern is more than irrational fear – it’s rooted in historical facts. And so I walked my sidewalks on edge, awaiting the worst possible scenario. An Asian friend asked why I don’t move to a Black neighborhood. (She, herself, lives in an “Asian” hood, walking the walk.) I’ve thought about uprooting myself, but my problem is, I still believe change is possible. So, for now, I write my letters and stake my roots. I can still hear the distant sounds of progress – even if so many don’t.

Natasha Lewin is a former LA elected official and homeless liaison to Mayor Eric Garcetti. She’s an award-winning playwright and screenwriter, and is an author and New York Times bestselling ghostwriter. Since she has no social media, you can only follow her down the street as she marches. She resides in Los Angeles.

On stories of Black struggle, an iconic L.A. bookstore surges

Books can change minds, and at one Los Angeles area bookstore, there are signs that is happening. There is “a multiracial attempt to understand the Black experience,” says a local professor.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

America, it seems, wants to educate itself about the Black experience.

“This is a huge moment for Black bookstores all over the country,” says James Fugate, co-owner of Eso Won Books in Los Angeles. He pops onto the website of a book distributor and reads off orders for “How To Be an Antiracist,” by Ibram X. Kendi: 10,000 in Oregon, 6,000 in Tennessee, 8,000 in Indiana, almost 9,000 in Pennsylvania. “That’s remarkable, incredible.”

The name Eso Won stems from the Egyptian city of Aswan, a gateway on the Nile River, and means “water over rocks.” The narrow store with the high ceiling is a gateway as well, located in Leimert Park, the epicenter of Black culture in Los Angeles.

Bestselling author Ta-Nehisi Coates calls it his favorite bookstore. It hosted an unknown Barack Obama in 1995 for a signing of “Dreams From My Father.”

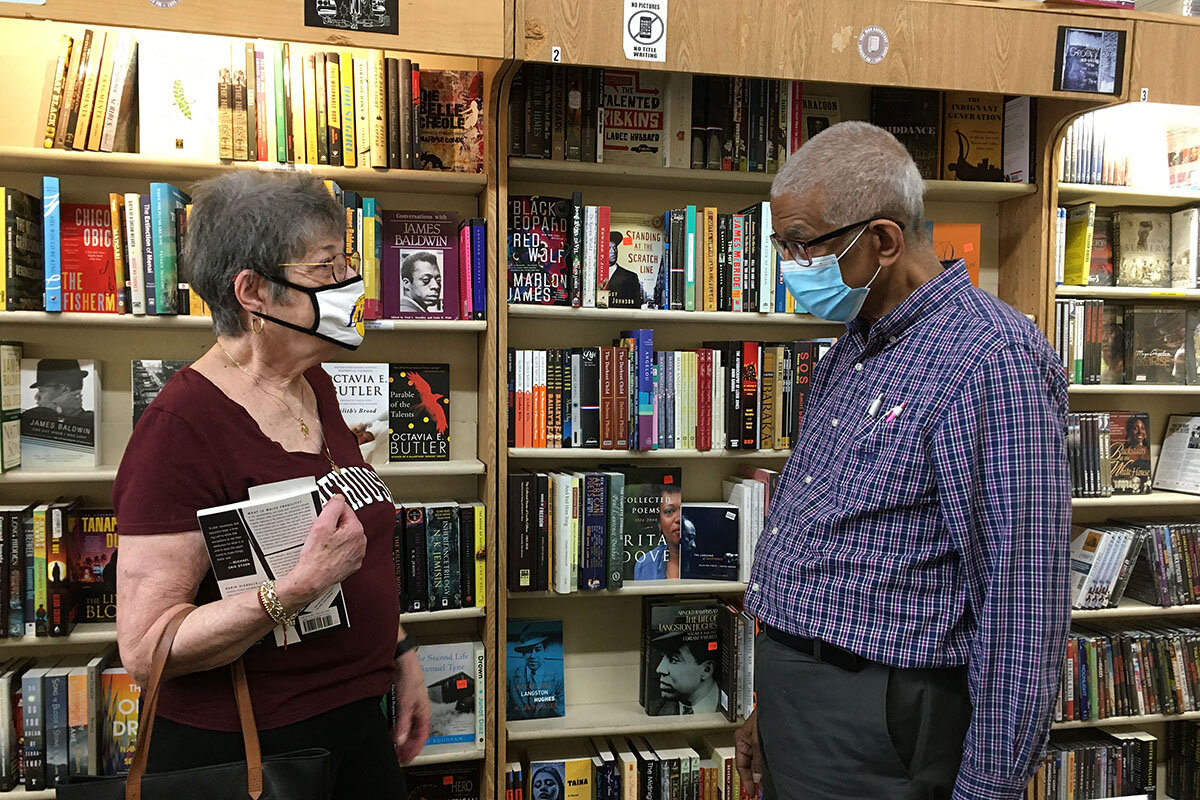

Mr. Fugate says that the store does have multiracial customers – thanks to its longtime presence at the Los Angeles Times book fair. Not a day goes by without a white, Latino, or Asian reader coming into the store. But on a recent Monday, African Americans were the minority among the mostly young visitors.

“We’re going to reach more audiences,” he says.

On stories of Black struggle, an iconic L.A. bookstore surges

Tom Hamilton is on the phone again. It has been ringing steadily since this Black-owned bookstore, Eso Won Books, opened at 10 a.m.

“No, we don’t have any right now,” he answers calmly. The caller is inquiring about “The Fire Next Time,” the powerful 1963 bestseller in which Black author James Baldwin writes his 14-year-old nephew about race in American history. “We should have it by the end of the week. We’re going to get 300 or 400 copies. Just call us.”

Mr. Hamilton and his business partner, James Fugate, are working morning, noon, and night to handle an explosion of demand for books on racism, African American history, and Black literature in the wake of nationwide protests over the killing of George Floyd. They’ve had to temporarily halt new orders on their website to catch up on back orders. One week of sales last week equaled March and April combined. On June 8, a stream of ethnically diverse customers browsed and bought at this landmark store in South Los Angeles.

America, it seems, wants to educate itself about the Black experience.

“This is a huge moment for Black bookstores all over the country,” says Mr. Fugate. He pops onto the website of one of their book distributors, Ingram Content Group, and reads off the orders for “How To Be an Antiracist,” by Ibram X. Kendi: 10,000 in Oregon, 6,000 in Tennessee, 8,000 in Indiana, almost 9,000 in Pennsylvania. “That’s remarkable, incredible.”

A gateway to Black culture

The name Eso Won stems from the southern Egyptian city of Aswan, a gateway on the Nile River, and means “water over rocks,” explains Mr. Fugate. The narrow store with the high ceiling is a gateway as well, located in Leimert Park, which is considered the epicenter of Black culture in Los Angeles. It’s in the same block as a jazz and blues museum.

Bestselling author Ta-Nehisi Coates calls it his favorite bookstore. It hosted an unknown Barack Obama in 1995 for a signing of “Dreams From My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance.” That event drew about 10 people, and Mr. Obama suggested they put their chairs in a circle and just talk. When his next book, “The Audacity of Hope,” came out, it was Eso Won that the rising politician wanted. He couldn’t remember the name of the little store, but that’s the only one he would consider in LA.

African American bookstores are an “oasis, a little safe space of intellectualism,” where Black people can go and talk about ideas, read about their history, and imagine alternative realities, says Alaina Morgan, an assistant professor of history at the University of Southern California. They are not places where other people typically go, says the specialist in the African diaspora.

“One of the amazing things that’s happening with Eso Won Books is this is a multiracial attempt to understand the Black experience,” she says. “Books can change people’s minds; they can change people’s lives.” She points to her students, who tell her that books like “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness” by Michelle Alexander have completely reshaped their thinking on race in America.

Mr. Fugate says that the store does have multiracial customers – thanks to its longtime presence at the Los Angeles Times book fair. Not a day goes by without a white, Latino, or Asian reader coming into the store. But last Monday, African Americans were the minority among the mostly young visitors. “We’re going to reach more audiences,” he says.

“I want to educate myself”

Phoebe Zerouni and Kaylee Elijah are working their way around the store as jazz piano music gently circulates with them. They are best friends from high school, where they read two novels by Toni Morrison. One was “The Bluest Eye,” Morrison’s first, and the other was “Beloved,” which won her the Nobel Prize in literature in 1993.

Now the friends are students at the University of California and are on the hunt for nonfiction.

“I came here to educate myself,” says Ms. Zerouni. “I grew up in a white family. I’ve absorbed unseen prejudices.” She says she wants to be a “better ally” to African Americans.

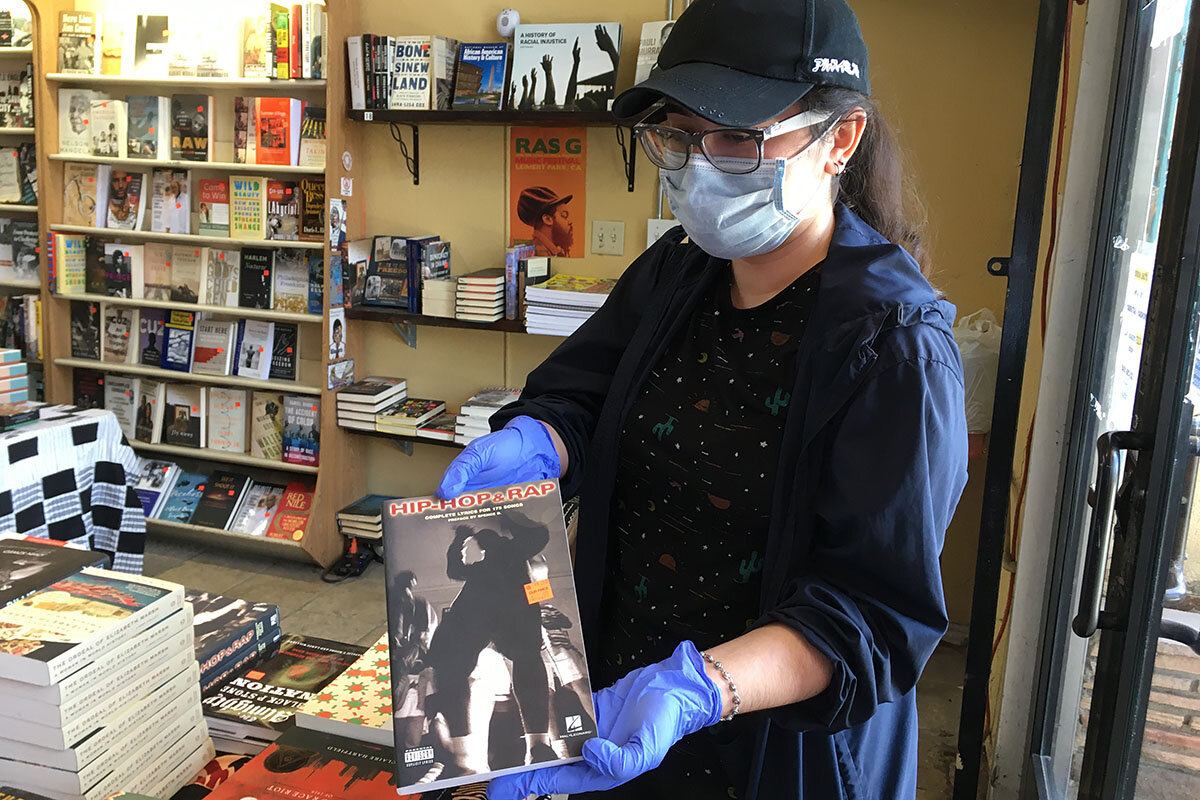

The two found out about the bookstore on a social media thread identifying local Black businesses to support. Ms. Elijah, who describes herself as Latina Indian, picks up the paperback “Hip-Hop & Rap.” She’s studying anthropology.

In the 1970s, Janet Chapman, a retired principal, was an anomaly as a white teacher in Black South-Central Los Angeles. “I’ve known about this bookstore forever,” she says, sporting a Morehouse T-shirt and Lakers mask. Still, this is her first visit – inspired by last week’s drop-in by California Gov. Gavin Newsom.

She buys a children’s board book about the Obama family – for her yoga instructor’s kids – and inquires about another popular title: “White Fragility: Why It’s so Hard for White People to Talk About Racism,” by Robin DiAngelo. Mr. Fugate reaches into a cardboard box of newly arrived books and pulls out a copy. Sold.

“I’ve been amazed at the people coming into the store, and just the pleasant conversations with everybody,” he says. He loves acting as a reference for good books, and did his best to help Shaina Sanchez in her quest to find a book that will help Asian Americans “struggling to understand how their experience parallels that of African Americans.” She is Filipino American.

He found himself at an impasse: His recommendation was “African Samurai: The True Story of Yasuke, a Legendary Black Warrior in Feudal Japan,” by Thomas Lockley and Geoffrey Girard, “but we don’t have it.”

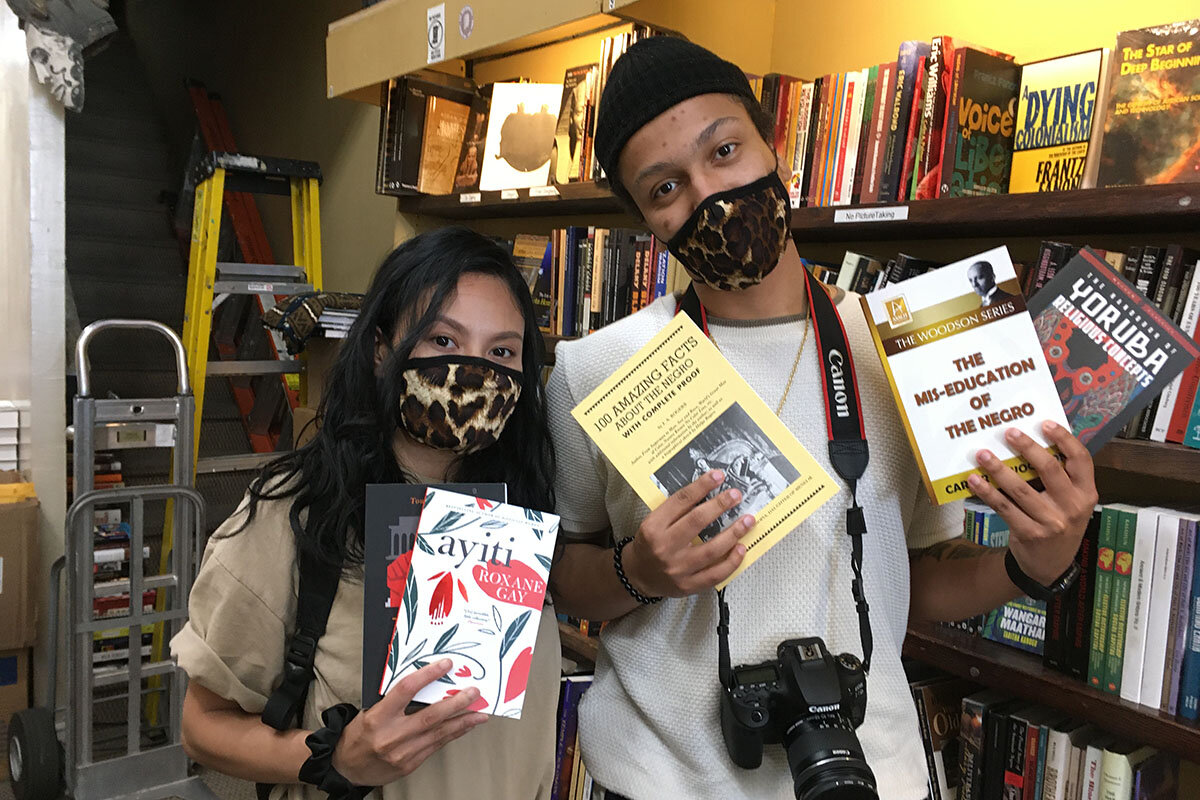

That didn’t stop Ms. Sanchez and her partner, Rodney Wright, from buying an armful of books. Mr. Wright, a musician who goes by the name “Vinci,” is promoting an Instagram campaign, #bobchallenge, to buy from Black-owned businesses for seven days straight. Growing up “in the hood” in New York, Mr. Wright – who is Black and Puerto Rican – says his knowledge of Black history was pretty much limited to Martin Luther King Jr., Malcom X, and the freeing of the slaves.

Which is exactly why Kelisa Lewis walked a mile to this bookstore. The 30-something transplant from the San Francisco Bay Area came away with a book on the philosophy of Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican activist and leader of the Pan-Africanism movement. Since she loves poetry, she also bought a collection by Langston Hughes.

“Some African Americans, we don’t know a lot about our past,” she says. “Let me do my part, and educate myself.” After all, “you want the backstory, so you have a better sense of self.”

James Fugate, co-owner of Eso Won Books, recommends:

“Chokehold: Policing Black Men,” by Paul Butler, a former federal prosecutor and professor at Georgetown University. Mr. Fugate likes that it has solutions.

“Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools,” by Monique W. Morris. As Mr. Fugate notes, “Kids are kids, but somehow Black girls end up more in detention that white females.”

Alaina Morgan, assistant professor of history at the University of Southern California, recommends:

“The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness,” by Margaret Alexander, about racial discrimination in America’s criminal justice system.

“The Case for Reparations,” by Ta-Nehisi Coates, published in The Atlantic, about America’s debt to African Americans.

Both selections “completely reshaped” the way her students thought about race, she says.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

What sustains social movements

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The death of George Floyd, a Black man killed last month in the custody of four Minneapolis police officers, has created swift momentum for real change, especially in police funding and procedures. When another Black man was fatally shot in an altercation with two Atlanta officers Friday, the police chief resigned and medical examiners ruled Rayshard Brooks’ death a homicide. Seldom has that degree of accountability followed such an encounter so swiftly.

Time will prove whether such responses reflect lasting change in the United States. Social movements often follow long trajectories to achieve structural reforms. Before they achieve visible results, however, they first require a quiet molding and chiseling of individual thought, the kind that goes beyond initial rage or short-lived empathy.

The social justice movement that has gathered momentum since the killing of Mr. Floyd reflects a new generation grappling with racism. Public rage may compel some reforms. But durable change happens only when enough people adopt a meekness, presence, and willingness to see and alleviate the adverse conditions of another human being’s daily experience. By all current signs, a great stirring of thought in that direction is underway in the U.S. and beyond.

What sustains social movements

The death of George Floyd, a Black man killed last month in the custody of four Minneapolis police officers, has created swift momentum for real change. New York and Los Angeles are reallocating portions of their police budgets to education and development in minority communities. The Boston Police Department has adopted reforms that would prohibit specific uses of force. Prominent Black activist groups have been so inundated with financial pledges that they are redirecting contributions elsewhere.

When another Black man was fatally shot in an altercation with two Atlanta officers Friday, the police chief resigned and medical examiners ruled Rayshard Brooks’ death a homicide. Seldom has that degree of accountability followed such an encounter so swiftly.

Time will prove whether such responses reflect lasting change in the United States. Nearly six years after protests erupted in Ferguson, Missouri, following the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown, few of the 47 police reforms recommended by a state-appointed commission have been achieved.

Social movements often follow long trajectories to achieve structural reforms. Before they achieve visible results, however, they first require a quiet molding and chiseling of individual thought, the kind that goes beyond initial rage or short-lived empathy.

There is no easy way to measure the extent of current changes in individual attitudes. A Washington Post-Schar School poll last week found 69% of Americans said police violence against African Americans reflected broader societal problems, up from 43% who held that view after the events in Ferguson. Civil rights leaders say the current protest marches are the largest and most diverse they have ever seen.

Yet those who have dedicated their lives to addressing racial and economic injustice say an increased awareness of social issues is only a first step. “There’s the intellectual step,” said one leader of a nonprofit group in an interview, “and then comes a question: What are you willing to give up as a beneficiary of the current system in order to change the system? It is hard to take that next step.”

When asked to describe their motives, many activists demurred. Their reasons are unique and deeply personal. Some are impelled out of having failed to make a difference in someone’s life when they were in a position to do so. Others were moved by what they knew themselves of how the criminal justice system treated poor and minority people caught up in even minor offenses.

All of them spoke of overcoming pride, fear, and personal comfort. One man turned his opposition to the Vietnam War into a lifetime of service to youth at risk of gang violence. “I found the most dangerous urban situation I could find,” he said. He is still there half a century later.

“It is important that we don’t get shy, that we dedicate ourselves to wonderful endeavors,” he said. “That kind of love is like an imprint on bare wood. It is unforgettable if it is real and if it is lived.”

The social justice movement that has gathered momentum since the killing of Mr. Floyd reflects a new generation grappling with racism. Public rage may compel some reforms. But durable change happens only when enough people adopt a meekness, presence, and willingness to see and alleviate the adverse conditions of another human being’s daily experience. By all current signs, a great stirring of thought in that direction is underway in the U.S. and beyond.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Healing prejudice

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Rita Smith

We hear all too often of troubling incidents stemming from racism. Here’s an audio clip in which a Black woman shares experiences of being confronted with racism and the key role prayer played in healing those situations.

Healing prejudice

To hear Rita’s story, click here.

Originally aired as a segment in a “Sentinel Radio” episode, March 26, 2000.

A message of love

A historic ruling

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when Henry Gass looks at today’s historic Supreme Court decision on LGBTQ rights.