- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

NBA players wrestle with how to fight racial injustice

As the National Basketball Association solidified plans to resume play in Orlando, Florida, next month, the league figured that pandemic safety concerns would keep some players at home. Now something else may stop their participation: their moral compass.

NBA players are facing a dilemma: What’s the most effective way to help end racial injustice, to play or boycott?

Last Friday, injured Brooklyn Nets star Kyrie Irving hosted a Zoom meeting with more than 80 players. He urged them to cancel the NBA 2020 season, saying, “I’m willing to give up everything I have [for social justice],” reported The Athletic.

Los Angeles Lakers center Dwight Howard released a statement Saturday that reads in part, “Basketball, or entertainment period, isn’t needed at this moment, and will only be a distraction.”

The quest for racial equality is bigger than sports. And these NBA players want to seize what’s seen as historic momentum. Others, including LeBron James, argue that a televised NBA game offers a bigger advocacy platform – and a more diverse audience – than a Twitter following.

“We can do both. We can play and we can help change the way Black lives are lived,” Houston Rockets guard Austin Rivers wrote on Instagram.

As some fans observe, to work – or not – is a multimillionaire’s dilemma. But the fact that these wealthy athletes are having a public debate over how to best push for lasting justice is a kind of progress too.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Why Gorsuch upheld civil rights for LGBTQ Americans

Some may be surprised by the U.S. Supreme Court’s landmark ruling that protects sexual orientation and gender identity. Our reporter looks at why this decision makes sense to conservative justices.

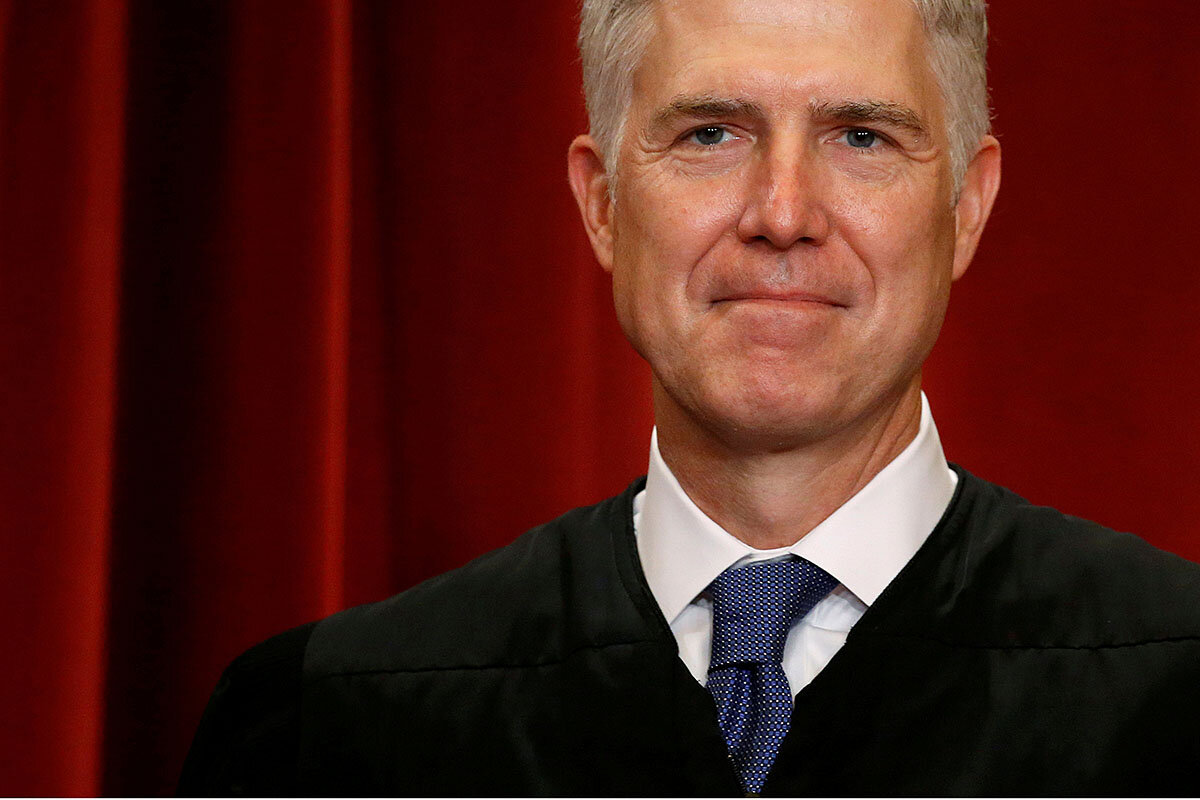

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote the 6-3 majority opinion enshrining civil rights for LGBTQ Americans. In his view, Monday’s historic ruling was a straightforward one.

The 172 pages of opinions tell a more complicated story – one of debate between the court’s conservative justices over how best to interpret laws based on the “ordinary meaning” of the text.

Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibits employment discrimination based on “race, color, religion, sex and national origin.” The majority held that “sex” covers “gay or transgender” people.

“Those who adopted the Civil Rights Act might not have anticipated their work would lead to this particular result,” wrote Justice Gorsuch. “But the limits of the drafters’ imagination supply no reason to ignore the law’s demands.”

While questions of religious liberty remain to be addressed, the ruling is a momentous one. Title VII is a “super statute,” says Yale law professor William Eskridge. For individual rights, “It has more ramifications for most Americans than the Constitution.”

“What is important to us? It’s the same things that are important to other Americans,” he adds. “That’s to not be [criminalized]; to have our families recognized; and to have jobs and not to be discriminated against.”

Why Gorsuch upheld civil rights for LGBTQ Americans

In a landmark, and unexpected, decision yesterday, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that firing an employee because of their sexual orientation or gender identity violates federal law.

In what could be a month of blockbuster decisions from the high court, the ruling immediately ranks among the most consequential civil rights rulings in the court’s history, experts say. The fact it came from a court with a small but deeply conservative majority – and that so many people tried to access the opinion online it crashed the court’s website – only heightened the drama.

To hear Justice Neil Gorsuch – who wrote the 6-3 majority opinion – tell it, the landmark ruling was a straightforward one. The 172 pages of opinions tell a more complicated story – one of three-pronged debate between the court’s conservative justices over the best practices of textualism, a judicial method of interpreting laws based on the “ordinary meaning” of the text.

Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act prohibits employment discrimination based on “race, color, religion, sex and national origin.” In that statute, the majority held that “sex” covers people who are “gay or transgender.”

“Those who adopted the Civil Rights Act might not have anticipated their work would lead to this particular result,” wrote Justice Gorsuch. “But the limits of the drafters’ imagination supply no reason to ignore the law’s demands.”

“When the express terms of a statute give us one answer and extratextual considerations suggest another, it’s no contest,” he added. “Only the written word is the law, and all persons are entitled to its benefit.”

Required reading

The ground-level effects of the ruling are significant. In 25 states there are no explicit prohibitions against discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity. It also came days after the Trump administration – which had opposed the LGBTQ employees in the case – eliminated regulations prohibiting discrimination against transgender patients in health care.

“This is as important a ruling as Obergefell [v. Hodges],” the 2015 decision legalizing same-sex marriage, says Michael Boucai, a professor at the University at Buffalo School of Law, “simply because employment is such a basic human need.”

And when one of the high court’s staunchest defenders of LGBTQ rights, Justice Anthony Kennedy, retired in 2018, most court watchers expected those rights only to get rolled back.

“It’s a matter of great good luck that the arguments that could be made in this case are obviously going to appeal to someone like Gorsuch,” says Mary Anne Case, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School.

“It would have been hard for Gorsuch to cast a different vote without looking unprincipled,” she adds.

All nine justices would consider themselves textualists, to the extent they give the actual text of a statute significant weight when they interpret it. But Justice Gorsuch may be the strictest.

“The role of a judge is to say what the law is,” he said during his 2017 confirmation hearings. “Before I put a person in prison, before I deny someone of their liberty or property, I want to be very sure that I can look them square in the eye and say, ‘You should have known.’”

Yet he is also a conservative justice with a strong belief that the Supreme Court should not be driving social change. This case brought those two core principles to a head, and strict textualism won.

In a detailed, 32-page scrutiny of the “because of ... sex” phrase in Title VII, he makes the pivotal holding that while the law doesn’t explicitly reference LGBTQ employees, and while Congress in 1964 may not have intended it to cover them, it protects those employees nonetheless.

“When an employer fires an employee for being homosexual or transgender, it necessarily and intentionally discriminates against that individual in part because of sex,” he wrote.

Title VII “is a major piece of federal civil rights legislation. It is written in starkly broad terms. It has repeatedly produced unexpected applications,” he added. “The same judicial humility that requires us to refrain from adding to statutes requires us to refrain from diminishing them.”

Monday’s ruling also suggests that, if Congress were to pass clearly articulated legislation expanding protections for LGBTQ Americans, this court would uphold it. LGBTQ Americans are “still unprotected from discrimination in housing, and discrimination in public accommodations,” says Kimberly West-Faulcon, a constitutional law professor at Loyola Law School in Los Angeles.

Monday’s rationale for enshrining new civil rights for LGBTQ Americans differs markedly from Obergefell, the high court’s last major opinion in the area.

First, that case concerned a constitutional question instead of a statutory one. The Supreme Court is typically more reluctant to reinterpret the Constitution than a statute, but former Justice Kennedy was also plain in his opinion that while the 14th Amendment’s due process clause didn’t guarantee a right to same-sex marriage, it should.

“The nature of injustice is that we may not always see it in our own times,” he wrote. “When new insight reveals discord between the Constitution’s central protections and a received legal stricture, a claim to liberty must be addressed.”

“It applies to us”

Justice Kennedy was joined in that opinion by the court’s four liberal justices, and that judicial philosophy – that laws and the Constitution can and should evolve with the times – is traditionally popular on the left.

Textualism is traditionally popular on the right, but yesterday’s ruling showed that it can also contain multitudes.

As Justice Samuel Alito wrote in a dissent (joined by his conservative colleague Justice Clarence Thomas), the majority opinion is not textbook textualism, but a “pirate ship.”

“It sails under a textualist flag,” he wrote. But “there is only one word for what the Court has done today: legislation.”

“When textualism is properly understood, it calls for an examination of the social context in which a statute was enacted,” he added.

The social context 50 years ago, he argued (with 52 pages of appendices), included that sodomy was a crime in every state but Illinois, and that discrimination because of “sex” was understood “to refer to men and women.”

In his own dissent, Justice Brett Kavanaugh leveled a different textualist argument: that the majority doesn’t apply the “ordinary meaning” of the text of the law, and that it departs from how “sex” discrimination has been interpreted in federal law for 25 years.

The robust debate over how to interpret statutes by itself makes the case something of a landmark, says William Eskridge, a professor at Yale Law School and author of the forthcoming book “Marriage Equality: From Outlaws to In-Laws.” Both dissenters cited his research on statutory interpretation and the history of LGBTQ rights, but in his opinion, Justice Gorsuch won the debate.

“He accounts and relies on more text than the dissenters do. He explains more text, he is more thorough on the textual front,” adds Professor Eskridge, who also wrote an amicus brief supporting the LGBTQ employees in the case.

This kind of schism between the court’s five conservatives has not been unusual since President Donald Trump consolidated their majority with the appointments of Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh.

“This is a 5-4 majority, so if even one vote defects that majority isn’t there, and the conservative justices do have many disagreements among themselves,” says Ilya Somin, a professor at George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia Law School.

“It varies by the issue,” he adds. “Gorsuch has been more willing to subvert expectations than other conservatives.”

While this is a landmark ruling for LGBTQ civil rights, the majority acknowledged that some important questions remain unanswered. Notably, the degree to which this ruling might burden an employer’s free exercise of religion, and whether transgender people can use sex-segregated bathrooms or locker rooms in line with their gender identity.

“What the court has given here it can potentially take away with a vengeance” when it comes to religious employers, says Professor Case. “And if they do that it [could] not just be LGBT employees left with little to no protection, it [could] be every employee on every ground, with perhaps the exception of race.”

This move could begin as early as this month, with the justices deliberating over a case argued last month over the “ministerial exception” doctrine, which bars certain employees of churches or other religious institutions from suing their employers for employment discrimination.

But the ruling is still a momentous one. Title VII, as Professor Eskridge describes it, is a “super statute.”

“It has more ramifications for most Americans than the Constitution does, in terms of individual rights,” he says. “Discrimination based on sex – that’s a whopper. It’s a broad statute, and it applies to us.”

“What is important to us? It’s the same things that are important to other Americans,” he adds. “That’s to not be [criminalized]; to have our families recognized; and to have jobs and not to be discriminated against.”

Staff writer Story Hinckley contributed to this report.

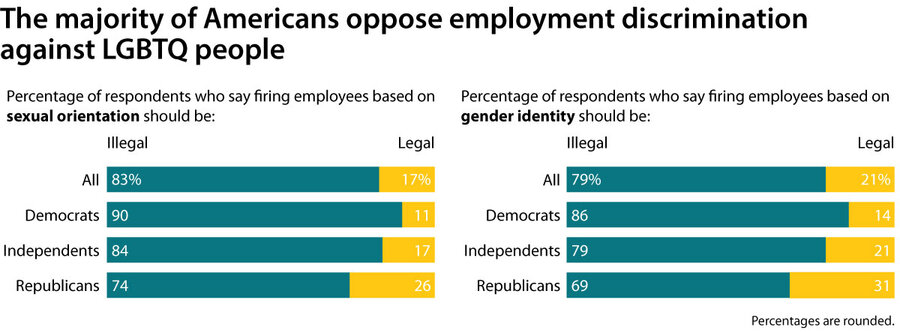

SCOTUSPoll

‘History in the making’? Seattle’s protest zone prompts rethink of policing.

Six blocks of Seattle – a so-called “autonomous zone” – jumped into the media spotlight last week, becoming a symbol of anarchy to some and reform to others. On the ground, our reporter found a more complicated picture.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

On the leafy streets of Capitol Hill in Seattle, six blocks have become an activist hub, attracting attention from Washington, D.C., and beyond. Last week, amid tense rallies against racism and police violence, officers abruptly vacated the local precinct, and the activists christened the area the “Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone.”

This weekend, they changed the name to CHOP. But what that stands for depends on whom you ask, a reflection of the movement’s evolving goals and leadership. Outside views of the area are even more complicated, with some supporters seeing it as a beacon of hope for their movement, and conservative critics as a danger.

But here in the zone – where a diverse community has set up open mics and a garden, and danced in the street – activists say CHOP’s main purpose is to imagine, debate, and experiment with a radically different relationship between police and community.

The night the zone was created, “lots of people who had had their voices silenced for generations had a chance to get up in front of the crowd. It was the people’s mic,” says a protester named John, an unemployed theater worker who lives a block away. “It was a remarkable turn of events. That felt like a victory to me.”

‘History in the making’? Seattle’s protest zone prompts rethink of policing.

As a police chopper circles overhead, a protester named John, wearing a Black power pin, stands watch at a barricade at the entrance to Seattle’s spontaneous new hub of activism – a six-block area that demonstrators initially dubbed the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ).

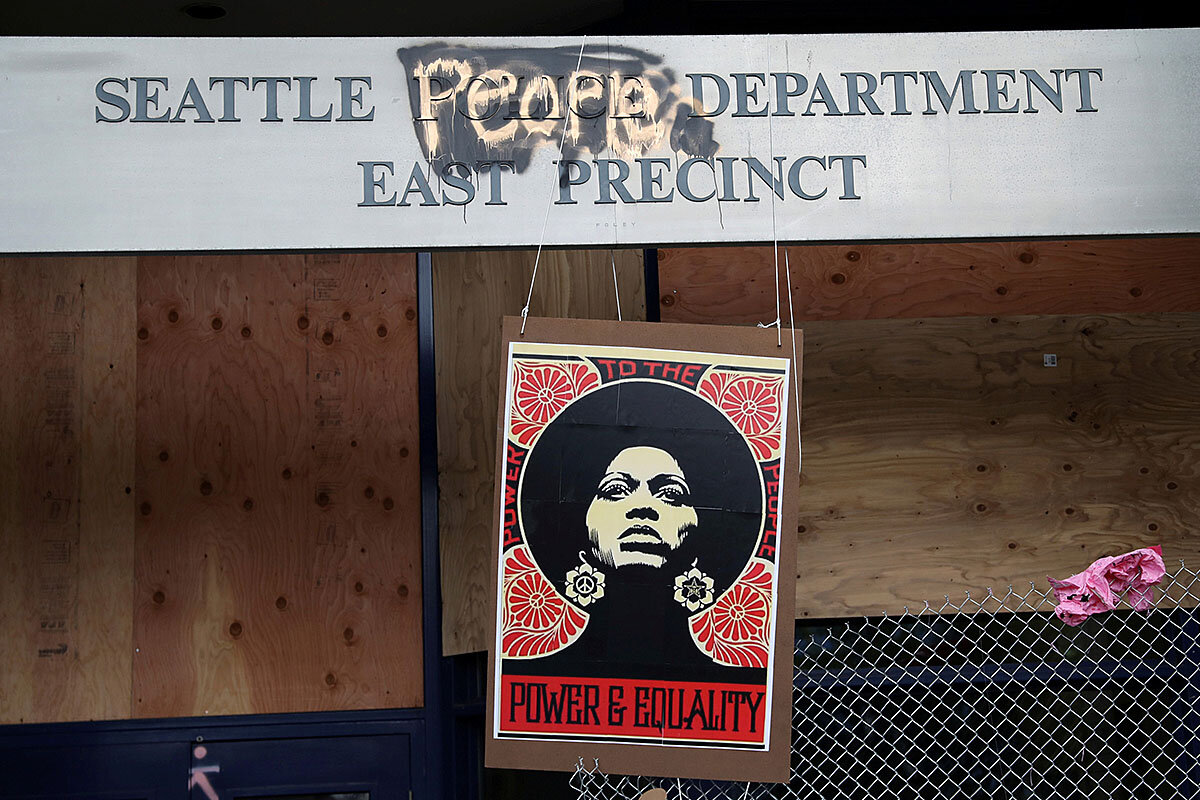

Orange barricades left behind by police, who abruptly vacated the Seattle Police Department’s East Precinct building last week amid rallies against racism and police brutality, are now plastered with posters calling to “Defund SPD” – a key demand of activists here who seek to shift half the police budget into community services.

But views are mixed on the police role and future of the station. Many signs and graffiti are hostile to cops. Yet John, an unemployed theater worker who lives a block away and withheld his last name for privacy, says “autonomous zone” is a misnomer, and stresses that police can return to the station “whenever they want.” City officials, including police, Fire Chief Harold Scoggins, and Mayor Jenny Durkan, have freely entered the “zone” in recent days, along with flocks of visitors.

“There is no reason peaceful protest can’t coexist with police presence,” John says of the CHAZ, which over the weekend was renamed the CHOP. What that stands for, however, depends on whom you ask – a reflection of the movement’s evolving goals and leadership. An entry sign calls it the Capitol Hill Occupied Protest; some say the O now stands for “Organized.” John and others say they sought freedom to protest, but never asked police to leave.

Ensconced in Capitol Hill, a nightlife and entertainment district long a center of the city’s LGBTQ and counterculture communities, the protest zone has been largely peaceful since police left, although tensions have flared with counterdemonstrators. People speak at open mics, cook, paint protest art, light candles at a memorial to those killed by police, garden, watch documentaries and dance in the streets.

The main purpose of CHOP, activists here say, is to occupy the space in order to imagine, debate, and experiment with a radically different relationship between police and community.

“It’s showing the world that having police breathing down your neck all the time is not necessary,” says Black Lives Matter organizer Mark Henry Jr., standing in front of the boarded-up precinct building, its sign altered with gold spray paint to read: Seattle People’s Department. “This place will be a monument to social justice, and a beacon of hope to the world that police reform is not only possible, it is necessary.”

In the limelight

Seattle’s protest zone has grabbed the national and international spotlight, with sharp attacks from conservative critics including President Trump. On Sunday, Mr. Trump depicted it as a “takeover of Seattle” by “far-left militant groups.” On Monday, he repeated threats to crack down on the zone if Mayor Durkan and Washington State Gov. Jay Inslee do not.

Ms. Durkan, a former U.S. attorney, has called the president’s description untruthful and his threats illegal.

The zone “is not a lawless wasteland of anarchist insurrection – it is a peaceful expression of our community’s collective grief and their desire to build a better world,” she tweeted.

Last week, Seattle Police Chief Carmen Best told officers their departure from the precinct in Capitol Hill was “not my decision,” saying she was concerned about arson, but the city “relented to severe public pressure.” But both she and Mayor Durkan have initiated policing reforms in consultation with the community.

“This is a pivotal moment in history,” Chief Best, the first black woman to hold SPD’s top post, said Sunday in an appearance on Face the Nation. “We are going to move in a different direction and policing will never be the same,” she said, after participating in a Black Lives Matter march of 60,000 people in Seattle on Saturday that she said brought her an “epiphany.”

Seattle has moved rapidly to meet some protester demands – temporarily banning the use of tear gas except in life-threatening situations, requiring police to display name tags and wear body cameras at protests, and withdrawing the National Guard.

Experts in criminal justice reform say that too often, police are called because social workers or other professionals are not available, which Mayor Durkan says must change. More broadly, the United States needs to expand investment in low-income housing and mental health and addiction services, which have been underfunded for decades, says Katherine Beckett, a professor of law, societies, and justice at the University of Washington.

“The U.S. now spends twice as much on social control as on social welfare,” says Dr. Beckett.

What next?

On the leafy streets of Capitol Hill, the multiracial community of protesters ranges from professionals with remote day jobs to laid-off workers and homeless people. Activists have set up tents for shelter and started a community garden in Cal Anderson Park. Donated food and medical supplies, including gloves, masks, and hand-sanitizer to fend off the coronavirus, are distributed from sidewalk stalls. Everyone pitches in to pick up trash.

“It seems to be a good place to live. I’m not going to be bothered by the cops,” says Ada, an out-of-work computer programmer who moved here from Dallas several weeks ago and has been living out of her car. “It’s history in the making. It’s cool,” she says, cooking a pan of beans and rice over a camping stove set up in a red wagon, “but also complicated.”

One complication, protesters say, involves threats from white extremist groups, such as Proud Boys; several men wearing “Proud Boys” shirts showed up Monday. Protesters have kept police barricades in place, which they say is primarily to keep drivers from harming crowds, as happened last Sunday when a gunman drove toward protesters, shooting one in the arm who tried to stop him. They have also formed a night watch from 1 a.m. to 5 a.m. “I help out where I can with the watch,” says Ada, who declined to give her last name.

Over the weekend, occupiers grouped in circles at the CHOP main intersection discussed goals, and then formed teams to handle different duties ranging from security to technology and communications. “Our long-term goal is to … make a community center so we have a place we feel safe to come to,” says Anthony Barr, a laid-off Applebee’s server and front-line protester.

At the same time, protester representatives are making headway in regular talks with Seattle officials led by Fire Chief Scoggins, who they say has won their trust. This week, they reached initial consensus on an option to ease access for residents, businesses, and emergency vehicles, while preserving space for demonstrations and improving safety.

Sam Zimbabwe, director of the Seattle Department of Transportation, told citizen journalist Omari Salisbury the alterations are designed so “the neighborhood can get back to co-existing with the protests… this is Seattle values….we are all really trying to find space together.”

Ron Amundson, a local property owner, said some businesses are afraid to open, and voiced concern about fire and safety, as did some residents who no longer sleep in the zone at night. He urged the group to decide quickly on a way forward. “We can all work together here and turn this into something good,” he said. Police Chief Best has said that while response times are increased, officers would respond to important emergency calls in the zone.

Some businesses are thriving as people crowd the area. “Honestly I do feel safer” since the police left, says Kohl Travis, host at Momiji, a Japanese restaurant across the street from the abandoned precinct building. “It’s definitely a less hostile environment.”

Surveying the scene from the “No Cop Co-op” on East Pine Street – where “Black Lives Matter” is written in huge, colorful letters – Brian, a health care worker who asked not to give his last name, is moved by the crowd and sidewalks spray painted with Black and white fists side by side. “You have people of all races coming in and helping,” he says, as he hands out donated Clif Bars. “Some people don’t have much money … maybe they only have two water bottles, they just want to give something, anything to the cause. It’s a beautiful thing.”

Back on the barricade, John recalls his feeling the night the police left, after more than a week of tension. “They hopped on their bikes and rode up the street and disappeared,” he says. “I never thought the police would do that.” The next night, “we finally had the square and set up the PA, and lots of people who had had their voices silenced for generations had a chance to get up in front of the crowd. It was the people’s mic,” he says. “It was a remarkable turn of events. That felt like a victory to me.”

Patterns

Resetting the Russia relationship: A China play, too?

President Trump has long wanted closer relations with Moscow. Now he has a new motivation, writes our columnist, and it has bipartisan support: a desire to constrain China.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

U.S. President Donald Trump appears to be making overtures to Moscow in a new bid to improve ties that he has long wanted to strengthen. But this time, the international context is different, and President Trump has a new motivation for wanting to make nice with Russian President Vladimir Putin: China.

Recent signs of a possibly warmer relationship include arms control talks next week between U.S. and Russian officials, and President Trump’s suggestion that he would invite President Putin to a summit of the Group of Seven, even though Russia has been suspended from the group of economically advanced democracies.

They may come to nothing; members of Congress on both sides of the aisle are warier of President Putin than the U.S. president is. But as China spreads its influence and ambitions, growing numbers of lawmakers are coming to share President Trump’s hostility toward Beijing.

Fifty years ago, Richard Nixon made a surprise visit to Beijing and restored diplomatic relations with China as a means to circumscribe the Soviet Union. Could President Trump be attempting a reverse Nixon gambit, using Russia as a counterweight to China?

Resetting the Russia relationship: A China play, too?

Relations between the U.S. and Russia, which have been in a deep freeze since the Kremlin’s intervention in Ukraine and its annexation of Crimea six years ago, may be showing the first small signs of a thaw. And that’s in part because of the Trump administration’s hardening stance toward its main superpower rival, China.

The most significant indication of a possible reset came last week, with the announcement the United States had agreed to meet Russian negotiators in Vienna later this month to discuss the future of the decade-old New START agreement on nuclear arms control.

That’s important in itself. New START, which limits the number of nuclear warheads Washington and Moscow can have, was negotiated by the Obama administration and is due to expire early next year. President Donald Trump has already pulled Washington out of a number of other arms treaties. If New START were allowed to lapse, the world would be without any formal arms control arrangements for the first time in almost half a century.

The mere fact that the Vienna meeting is taking place does not guarantee a deal will be struck. First, there are the complex technical issues involved in any arms control deal. President Trump’s White House has devoted far less attention or preparatory work to structured diplomatic encounters than have past administrations.

Political and strategic considerations on both sides could also slow progress. Russia may not think it’s worth seeking an early deal as November’s U.S. presidential election approaches. The Trump administration, for its part, has been arguing that New START and other arms control accords are worth little unless they include China, too.

Not so bad, after all?

But in the wake of mixed signals, the decision to enter negotiations on New START does suggest reluctance in Washington to see these last arms control limits simply expire.

That’s not the only sign President Trump is interested in some form of reengagement with Russia at a time when he is adopting an increasingly hostile tone toward China over the COVID-19 pandemic.

Last month, the White House arranged the dispatch of dozens of ventilators to help Russia deal with COVID-19. Interestingly, that came a month after Russia flew a planeload of medical supplies to New York – pointedly organized by two Russian companies subject to the U.S. economic sanctions imposed after Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea.

President Trump also said this month that he plans to invite Russian President Vladimir Putin to the next meeting of the Group of Seven economically advanced democracies, due to take place in the U.S. – despite Russia’s suspension from the G-7 since Moscow’s intervention in Ukraine.

As with the New START talks, an invitation in itself would not necessarily mean any early move toward a thaw in relations. Again, there are likely to be obstacles, both practical and political: European G-7 members are less keen on a rapprochement with Russia, especially if it is aimed against China, and many members of the U.S. Congress on both sides of the aisle are skeptical as well.

They have not forgotten Russia’s interference in the 2016 presidential election – something that President Trump has downplayed or dismissed but which was confirmed not only by U.S. intelligence agencies but by a bipartisan majority on the Senate intelligence committee. That’s one reason the president has been frustrated in his long and openly stated desire to engage with the Russian leader and get a “fresh start” on ties with Moscow.

But again as with New START, the underlying message of the president’s statement on the G-7 is important. It highlights the relevance of the administration’s growing tensions with China.

President Trump didn’t just mention adding President Putin to the guest list. He criticized the existing G-7 structure – grouping the U.S., Britain, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, and Japan – as outdated. And he proposed inviting the leaders of a trio of democracies in China’s own neighborhood: India, Australia, and South Korea.

We’ve been here before, in reverse

Whatever pushback he might get from the current G-7 to a formal expansion of the group, the broader strategic and geopolitical aim – paying much warier attention to China’s growing power – could well gather momentum. It could also outlast the Trump administration.

It was President Trump’s predecessor, President Barack Obama, who launched a diplomatic and military “pivot to Asia” to take account of Beijing’s growing international influence and ambitions. And since the outbreak of COVID-19, which Chinese officials initially kept under political wraps, attitudes toward Beijing have been hardening among both Republicans and Democrats in the U.S. Congress.

While there’s far less bipartisan appetite for easing sanctions or warming ties with Russia, the China factor could, over time, change that calculation.

In superpower diplomatic history, there is what might be called a mirror-image precedent for just such a diplomatic recalibration: President Richard Nixon’s surprise 1972 visit to China. That move, establishing diplomatic ties after decades of shunning Beijing’s Communist regime, was in part designed to strengthen America’s diplomatic hand against its main rival, the Soviet Union.

On the chess board of international strategy, could President Trump now be attempting a reverse Nixon gambit?

The Explainer

What does ‘defund the police’ really mean? Three questions.

On its face, “defund the police” sounds sweeping and radical. But the phrase, and the movement behind it, involves a lot of careful thought about how to improve safety through community policing.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

In the wake of nationwide protests following the suffocation of George Floyd under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer, the idea of defunding police departments has gained momentum in the national conversation about law enforcement and race. But the term “defund” has led to pushback from those who worry it means eliminating police entirely.

Police officers have become the go-to first responders for a host of social problems. They themselves often say they are asked to function as social workers, family counselors, or crisis managers.

“When we talk about defunding the police ... it suggests you take the huge amounts of funds that you’re sending over to highly armed police forces and invest instead in education and health services and infrastructure, especially within the most marginalized and underrepresented communities,” says Tyler Parry, a professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

“There’s this growing feeling that reform is just no longer enough,” says Sekou Franklin, a professor at Middle Tennessee State University. “You’ve had body cameras, for example, you’ve had implicit bias training, you’ve had deescalation training. But you could have all of these reforms, but even still, racial disparities never seem to change.”

What does ‘defund the police’ really mean? Three questions.

In the wake of nationwide protests following the suffocation of George Floyd under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer, the idea of defunding police departments has gained momentum in the national conversation about law enforcement and race. But the term “defund” has led to confusion and pushback from those who worry it means eliminating police entirely.

What does “defund the police” really mean?

Many advocates say the idea is premised on a simple question: What role should police be playing in society, even as their departments are taking up enormous chunks of cash-strapped municipal budgets?

Police officers have become the go-to first responders for a host of social problems that might be better left to other professionals, many argue. Police officers themselves often say they are asked to function as social workers, family counselors, or crisis managers.

“When we talk about defunding the police, it’s different from reform movements in that it suggests you take the huge amounts of funds that you’re sending over to highly armed police forces and invest instead in education and health services and infrastructure, especially within the most marginalized and underrepresented communities,” says Tyler Parry, professor of African American and African diaspora studies at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

More controversially, however, other advocates argue that American policing is critically broken, its history is steeped in structural racism and overt racial violence, and that defunding police departments is the first step toward revamping a justice system that is focused on people of color in overwhelming and outsize numbers.

Are the ideas behind defunding the police new?

No. Many scholars make a distinction among three efforts to revamp America’s criminal justice systems over the past few decades: abolish, defund, or reform. In the 1970s, advocates began to call for the abolition of America’s emerging prison industrial complex, the largest in the world by far. Scholars began to study the “systemic racism” within the nation’s criminal justice system, including the so-called war on drugs that has been waged on Black and other nonwhite Americans, even though over 60% of illegal substances such as cocaine and marijuana continue to be consumed by white Americans.

Much of the defund movement today stems from the early ideas of the more radical abolition movement, scholars say. “There’s this growing feeling that reform is just no longer enough,” says Sekou Franklin, professor of political science at Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro. “You’ve had body cameras, for example, you’ve had implicit bias training, you’ve had deescalation training. But you could have all of these reforms, but even still, racial disparities never seem to change.”

Have any U.S. cities begun to defund their police departments?

Minneapolis, the city where George Floyd was killed by police, is poised to redirect police funds to affordable housing, solutions for the opioid epidemic, and other mental health resources. In Los Angeles, city officials said police funding would be cut by $150 million and then redistributed in communities of color “so we can invest in jobs, in health, in education and in healing.” New York City officials announced they would begin to divert funds from the NYPD toward social services. On June 15, city officials also announced that they are disbanding the special unit of 600 plainclothes cops, which has been involved in the city’s most notorious police shootings.

Yet some alternatives predate the Floyd killing. Seven years ago, Camden, New Jersey, abolished its police department and replaced it with a revamped and far less aggressive police force. Last year in Austin, Texas, 911 operators were instructed to ask whether the caller needs police, fire, or mental health services. And in Eugene, Oregon, city officials formed a team called CAHOOTS – Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets – which deploys crisis workers and medics with mental health training to respond to emergency calls.

“Even though the crime rate has declined dramatically over the last 30 years, we still warehouse more than 2.3 million people in prison – and more than half the people in there have substance or alcohol abuse issues, many of them have mental health issues, and almost all of them are poor and have had problems within the educational system or from the lack of jobs in their communities,” says Stephanie Lake, director of the criminal justice program at Adelphi University in New York. “So the big push today is that our society needs to reimagine not just policing, but the role and mission of policing.”

Books

Anti-racism reading list: 10 books to get started

To understand this moment in America’s fraught history of race, we asked essayist Andrea King Collier for her recommendations. These books speak to the ways that Black people have been denied their humanity, and offer pathways toward equity, justice, and empathy.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Andrea King Collier Correspondent

If you want to know what Black people are thinking and feeling, you have to go to the books with their voices and their lived experiences. And I can’t help but think about how it was against the law during slavery for Blacks to read or write. I hadn’t really read Black voices until I was in my early 30s, when I read Maya Angelou's memoir, “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.”

If the only victim you can name is George Floyd, dig into Wesley Lowery’s “They Can’t Kill Us All: Ferguson, Baltimore, and a New Era in America’s Racial Justice Movement,” which is a deep dive into the quest for justice in the deaths due to police violence of Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, and Freddie Gray.

And as I shaped my list of books, others were shaping theirs. For the first time in the history of bestseller lists, the recent Top 20 books all dealt with race, privilege, and inequity.

But I caution that reading about race is not a beach read. None of these books is going to be made into a Hallmark movie. Each of them will get under your skin and linger a while, as they should.

Anti-racism reading list: 10 books to get started

As a Black woman, my email and social media have been flooded recently with expressions of deep and sincere concern over race. I was horrified but not surprised by the killing of a Black man, George Floyd, by a white police officer in Minneapolis. There have been too many of these deaths for me to be shocked. I say to everyone who asks, “Saddle up and stay awhile, because there is no quick fix.”

But it is time for some context, which can be found by reading a good book.

The gap in American history, which this tragedy exposes, can only be filled with knowledge. Read, watch, learn, and then talk a lot. As I write this, I have at least 30 books on the floor of my office, and I’m pondering which ones would provide the right first experiences. I don’t want to throw people into the deep end of the social justice pool right away. It’s hard – the truths of being Black in America. I have narrowed it down to 10 that can serve as a way of sticking your toes in the water. Ten is a hard list.

I called Gayatri Patnaik, associate director and editorial director at Beacon Press, which has a long and storied history of publishing books that speak to racial discourse and social justice. Ms. Patnaik suggested “White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism,” by Robin DiAngelo, a white woman, which Ms. Patnaik says is “useful for white people to read so they can grapple with their privilege.” She also recommended “Gather at the Table: The Healing Journey of a Daughter of Slavery and a Son of the Slave Trade” by Thomas Norman DeWolf and Sharon Leslie Morgan. He is a white descendant of a family that profited from the slave trade and she is a Black woman who is descended from slaves.

I curate my beginners’ list carefully because guilt and shame are not the goal. I need you to understand why I feel an undercurrent of rage at white people who weaponize their institutionalized privilege. When a white person like Amy Cooper can call the police on a Black man who is merely bird watching in Central Park, we see evidence of privilege with too few consequences.

I also put on my list the very powerful “Breathe: A Letter to My Sons,” by Imani Perry, because it is written to her Black sons about growing up in America. As the mother of a Black son and the grandmother of two little Black boys, I found that she spoke to my fears and prayers. Ms. Perry’s book holds up next to the award-winning “Between the World and Me,” by Ta-Nehisi Coates, written for his son.

Ms. Patnaik also recommended Crystal Fleming’s “How to be Less Stupid About Race: On Racism, White Supremacy, and the Racial Divide.” “Don’t let the light-sounding title fool you,” she says, “it’s very smart and sharp.” She’s right. It is a good primer on how race gets covered in the media and plays out in politics, culture, and in the classroom.

I went back to one of my white friends to ask her what she had read on the lives of Black folks before now. She replied, “The Help” and “The Secret Life of Bees.” I didn’t have the heart to tell her that they weren’t about the Black experience, but they were books with Black folks in them.

If you want to know what Black people are thinking and feeling, you have to go to the books with their voices and their lived experiences. And I can’t help but think about how it was against the law during slavery for Blacks to read or write. My true confession is that I hadn’t really read Black voices until I was in my early 30s. The first book I read was Maya Angelou’s memoir, “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.” It blew my head back and changed my life as a writer. On its 50th anniversary, it still tugs at the truths of being Black in America. Then I read James Baldwin’s “The Fire Next Time,” a book that may have felt militant when it was published more than 40 years ago, but now it reads like it was ripped from the headlines.

And as I shaped my little list, others were shaping theirs. For the first time in the history of bestseller lists, the recent Top 20 books all dealt with race, privilege, and inequity. One book on almost everybody’s list is scholar Ibram X. Kendi’s “How to Be an Antiracist.”

And if the only victim you can name right now is George Floyd, dig into Wesley Lowery’s “They Can’t Kill Us All: Ferguson, Baltimore, and a New Era in America’s Racial Justice Movement,” which is a deep dive into the quest for justice in the deaths due to police violence of Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, and Freddie Gray.

My favorite book on the list was written for children, but it speaks to the little Black girl who still lives in me. “The Watsons Go to Birmingham – 1963” written by Christopher Paul Curtis. I lived through this time that Curtis frames. I read it once a year and it touches my soul each time.

But I caution anybody that reading about race, even if it is seen through the eyes of a child, is not a beach read. None of these books is going to be made into a Hallmark movie. Each of them will get under your skin and linger a while, as they should. Any reader would want to look away or at least put it down for a minute.

To understand how we got here, I also suggest “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness,” by Michelle Alexander. One needs to understand the legal context behind the inequity in our incarceration system. I recently reread it.

I am a Black woman who has loved books, and the secrets they hold, all my life. I am a descendant of slaves and of Jim Crow. My book bag is heavy. But I persist. Yet in the end, when I need to be anchored, I go back to the writings of Martin Luther King Jr., who speaks with a sense of urgency that holds up in 2020 as much as it did in the 1960s.

What should happen when white and Black people read the voices of Black men and women who are telling you about the America they know? I don’t look for it to heal us or wipe away the hurt and the pain. But it is a start. It is one piece of the puzzle.

This is not by any means a comprehensive list. It isn’t even my complete list. There is so much enlightening reading out there. Mine is a list that will get you started and hopefully make you want to read more.

Andrea King Collier is a multimedia journalist and author based in Lansing, Michigan. She specializes in writing about health and health policy issues.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Seattle’s other lesson in safety

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Protesters in Seattle have turned the city’s Capitol Hill neighborhood into a “cop-free zone,” a novel attempt to redefine security for a community. Eventually the city will sort out a new role for its police, and protesters will end their “watch patrols.” But one aspect of the experiment should not end.

Citizens in the zone are realizing that safety also lies in providing for others. They have set up shelters and a community garden. They are picking up trash. Most of all they are donating food, water, and health supplies. This burst of neighborly generosity in the name of social justice fits a new poll that finds young people have nearly doubled their charitable donations to address racial inequality, discrimination, or social injustice.

Young people are shaking up old patterns of giving. And given the events of 2020, giving may never be quite the same. The U.S. in particular is coping with a pandemic, a recession, and now a mass movement for social justice.

In Seattle, the new dynamics of generosity are playing out in one neighborhood. In the end, giving is about providing a safe and secure life for each other.

Seattle’s other lesson in safety

Protesters in Seattle have turned the city’s Capitol Hill neighborhood into a “cop-free zone,” forcing police officers to vacate their East Precinct building. After the recent killing of two black men by police in the United States, this is a novel attempt to redefine security for a community. Eventually the city will sort out a new role for its police, and protesters will end their “watch patrols.” But one aspect of the experiment should not end.

Citizens in the zone, dubbed Capitol Hill Occupy Protest, are realizing that safety also lies in providing for others. They have set up shelters and a community garden. They are picking up trash. Most of all they are donating food, water, and health supplies, especially face masks.

“You have people of all races coming in and helping,” one health care worker told the Monitor. “They just want to give something, anything to the cause. It’s a beautiful thing.”

This burst of neighborly generosity in the name of social justice fits a new nationwide poll. A survey by the group Cause and Social Influence found 20% of 18- to 30-year-olds have made a donation to address racial inequality, discrimination, or social injustice. The poll was taken soon after the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. That level of giving is nearly double found in other surveys in recent years. The giving was also the same across racial groups.

Young people are shaking up old patterns of giving in the U.S. They define giving broadly to include volunteering and peer-to-peer advocacy, says Laura MacDonald, vice chair of the Giving USA Foundation. They are less loyal to nonprofit institutions and more loyal to a cause.

The shift is not only among young people. Since the pandemic began, those wealthy Americans who have parked money in nonprofit financial institutions called donor-assisted funds have increased giving by 30% to 50%, according to Bloomberg News. The money is helping people such as health care providers and laid-off workers dependent on food banks.

Given the events of 2020, giving may never be quite the same. The U.S. in particular is coping with a pandemic, a recession, and now a mass movement for social justice. The good news is that charities entered the year after receiving in 2019 the second highest level of donations on record. Adjusted for inflation, the amount was $449.64 billion, according to Giving USA.

The giving environment is very dynamic right now, says Ms. MacDonald. Indeed in Seattle, the new dynamics of generosity are playing out in one neighborhood. In the end, giving is about providing a safe and secure life for each other.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Sincerity that brings healing light

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Dilshad Khambatta Eames

All too often, health, hope, and joy may seem vulnerable. But a sincere desire to feel God’s grace and to reflect it toward others opens the door to more healing and harmony in our lives.

Sincerity that brings healing light

Sometimes we may feel pulled into what I’ve heard called “me, me, me syndrome” – a self-centered view that it’s all about us. This kind of perspective stems from a materially based lens, which would indicate that there are limits to the supply of good, of health, of joy.

But what if we expand our thought to a spiritual perspective and consider the biblical view of God as infinite Spirit and Love, and of man and woman as the pure expression of divine Spirit? Christian Science explains that God’s goodness is a divine law, forever in operation, unrestricted by time, space, or matter. The eternal Christ, or the divine Truth that Jesus lived, uplifts heavy, burdened thought with the healing touch of divine comfort.

As we humbly and wholeheartedly lean on God – sincerely acknowledging the presence of divine goodness and striving to live, even in small ways, the virtues of divine Love – we experience greater freedom and healing in our lives.

Years ago, while working abroad, I studied voice performance as a hobby. I was a fairly new student of Christian Science, and a church friend and I were invited to sing with several local musicians at a popular concert venue. The night before the concert, I became fearful and wondered whether I was good enough to sing in this setting. To top it off, in my enthusiasm to give my best, I had rehearsed excessively and strained my voice, which reminded me of past vocal disappointments. “Not again,” I thought to myself.

I decided to call my church friend. Our conversation was comforting, and she shared a quote from a letter written by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, which struck a chord and perked me up. It was this: “A deep sincerity is sure of success, for God takes care of it” (“The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” p. 203).

I considered what this meant for me and my situation. A sincere motive to express joy and to give to others could not be confined. Divine Soul, or God, expresses vitality, strength, and beauty in each one of us in infinite individual ways that bless all. I could not be left out. It wasn’t about me as a mortal susceptible to strain and fear. It was about God, expressing Herself in all of Her children, including me.

As I considered these ideas, the mental burden of comparing myself with others melted away, and the next day I was able to sing freely, without discomfort or anxiety.

This is a modest example, but it does show me how every one of us can sincerely listen for and discern the gentle, active presence and power of Christ – and share it in ways that help heal, as evidenced in that sweet, awakening conversation with my friend.

And what if we’ve been insincere about certain things in the past? The good news is all of us have the innate qualities of sincerity, honesty, and love. Motives can change for the better in an instant when we’re humble enough to put aside a sense of personal ego and allow the gift of Christ to change and redeem us. “The admission to one’s self that man is God’s own likeness sets man free to master the infinite idea,” writes Mrs. Eddy in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” (p. 90).

Another passage in Science and Health speaks to the potential of true freedom through the transforming activity of the Christ: “Eternal Truth is changing the universe. As mortals drop off their mental swaddling-clothes, thought expands into expression. ‘Let there be light,’ is the perpetual demand of Truth and Love, changing chaos into order and discord into the music of the spheres” (p. 255).

“A deep sincerity” is native to us all. It is a moral power that lifts us up to witness the redeeming, impartial grace of God, where limitations on health, hope, and joy fade away, and God’s harmony is seen in tangible, healing ways.

A message of love

Máscara

A look ahead

Come back tomorrow. We’re working on a story about how Washington’s response to the George Floyd protests may be undermining U.S. moral authority abroad.

If you're a member of the reddit social media community, our Supreme Court reporter Henry Gass will be doing an Ask Me Anything (AMA) event about the limits of U.S. presidential power under the law at 1 p.m. E.T. Wednesday, at the politics subreddit community.