- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Of statues, democracy, and a way forward

I’ve lived in Washington, D.C., 32 years, but don’t ask me to identify most of the city’s statues. Sure, I have my favorites, starting with Joan of Arc leading the charge from Meridian Hill Park. Some, like Andrew Jackson in Lafayette Park, can be appreciated as art, but have become flashpoints. President Jackson forcibly moved Indigenous people from their land and enslaved people.

Earlier this week, protesters vandalized and tried to topple the Jackson statue, but were thwarted by police. Now it’s protected by a chain-link fence, awaiting its fate.

A radio interview Thursday with former New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu spoke to ways of dealing with controversial statues that involve a full spectrum of voices and force the whole community to wrestle with the past. Several years ago, during planning for the city’s tricentennial, renowned Black musician Wynton Marsalis suggested that the city’s Confederate statues be removed.

Mayor Landrieu agreed, and thus was launched a process: months of debate, a public hearing, a city council vote (6-1), a vote in the legislature, and court challenges. Finally, under cover of darkness to protect the workers, the statues came down.

Later, Mr. Landrieu used the experience as the frame for his memoir, “In the Shadow of Statues: A White Southerner Confronts History.”

“Here is what I have learned about race,” he wrote in an essay for Time. “You can’t go over it. You can’t go under it. You can’t go around it. You have to go through it.”

By doing that – and having a truly inclusive conversation guided by democratic processes – the public landscape changed.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Navigating uncertainty

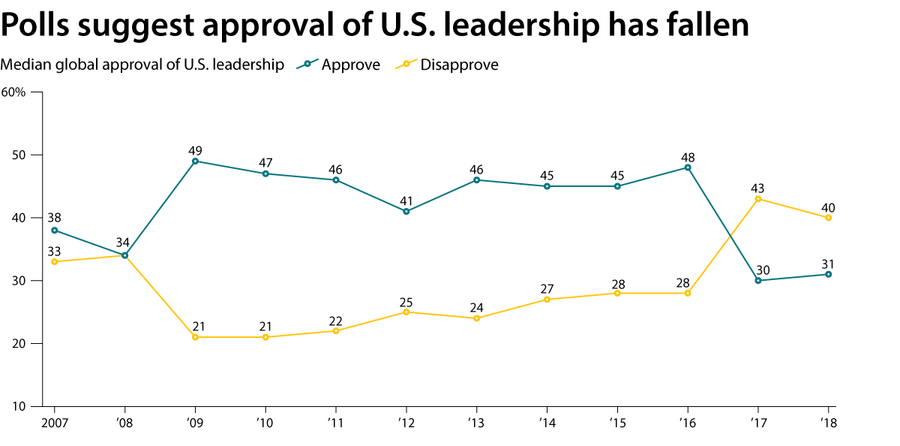

Power shift: How America’s retreat is reshaping global affairs

The U.S., which has led much of the world since the end of World War II, is pulling away from global institutions. Yet many believe U.S. leadership is needed to drive the world forward on problems that require big-power cooperation. Part 11 in our global series “Navigating Uncertainty.”

The United States has been limiting its global ambitions for some time now. But it has been nearly 100 years since the country has been led by a president who so deliberately turns his back on the rest of the world.

President Donald Trump believes America is stronger alone than in alliances. So he has withdrawn the U.S. from all sorts of international engagements – arms control treaties with Russia, the Paris climate accord, the deal to curb Iran’s nuclear program, a trans-Pacific trade deal, membership in the World Health Organization, and several others.

This has left America’s traditional allies nonplussed. Washington is still powerful enough, economically and militarily, to impose its will when it wants to. And it can stymie other nations’ efforts to solve problems – as with Iran, or climate change. At the same time, neither China nor the European Union – the other two global powers – is willing or able to step into the shoes Washington has filled for the last 70 years.

“When the U.S. opts out,” says Nicholas Burns, a former top American diplomat, “it makes it very difficult for the rest of the world to be effective.”

Power shift: How America’s retreat is reshaping global affairs

It has been nearly eight decades since President Franklin D. Roosevelt put an end to America’s era of isolationism, and stamped its irresistible influence upon the world.

And the world, while grumbling about it – often angrily – grew accustomed to that influence. U.S. leadership of the “free world,” and then virtually the entire globe after the collapse of the Soviet Union, was taken for granted.

But in three short years, President Donald Trump has thrown out all such expectations. He has turned his back on many of the international institutions that make the world run, most recently showing no interest in leading any global response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Long before the outbreak, Mr. Trump had repeatedly shown his distaste for joining multilateral initiatives – on trade, on climate change, and on Iran’s nuclear program, for example.

The rest of the planet, knocked off balance by this unfamiliar scenario, is still finding its bearings. Most countries did – in a sense – follow America’s lead on the pandemic, by pursuing an “every man for himself” approach. They closed their borders, competed with each other for scarce medical equipment, and, in China’s case, bickered over who was to blame for the origin of the virus.

“It’s been a shock to the system,” says Nicholas Burns, a former U.S. undersecretary of state. “COVID is a very apt example of what happens if a country the size of the United States refuses to lead.”

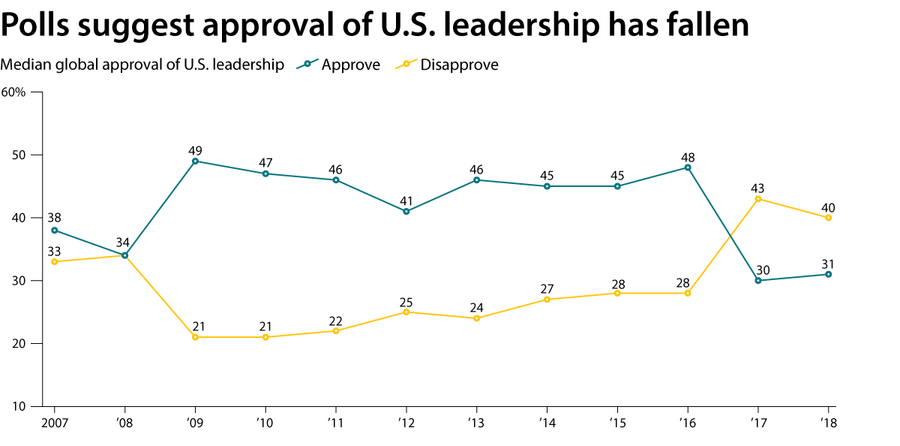

Gallup

The rest of the world has mostly patched together workarounds so as to manage the disruption caused by Washington’s abdication of its traditionally dominant role in world affairs, but how long can they last? And there is no avoiding the fact that in a world where no other power is ready or willing to fill America’s outsize economic and military shoes, the U.S. federal government’s failure to cope effectively with the COVID-19 outbreak at home has sparked grave misgivings abroad.

“Even if you disliked the United States, you had to respect it as the preeminent world power able to get things done,” says Yascha Mounk, who teaches international politics at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “But COVID has made people take the U.S. less seriously. If people look at you with pity, that’s not a great qualification for heading up the free world.”

Stronger alone

Mr. Trump is the first U.S. president since World War II to believe that America is stronger alone than as a member of alliances taking international cooperative action.Yet his neo-isolationist approach is in line with American public opinion. Nearly 6 in 10 Americans want the U.S. “to deal with its own problems and let other countries deal with their own problems as best they can,” a Pew survey found in 2016. Some 41% of respondents said Washington does too much, rather than too little (27%), to solve world problems. Nor did his policies spring from nowhere. They were foreshadowed in the reluctance of his predecessor, Barack Obama, to wield U.S. power as vigorously or as often as had once been common.

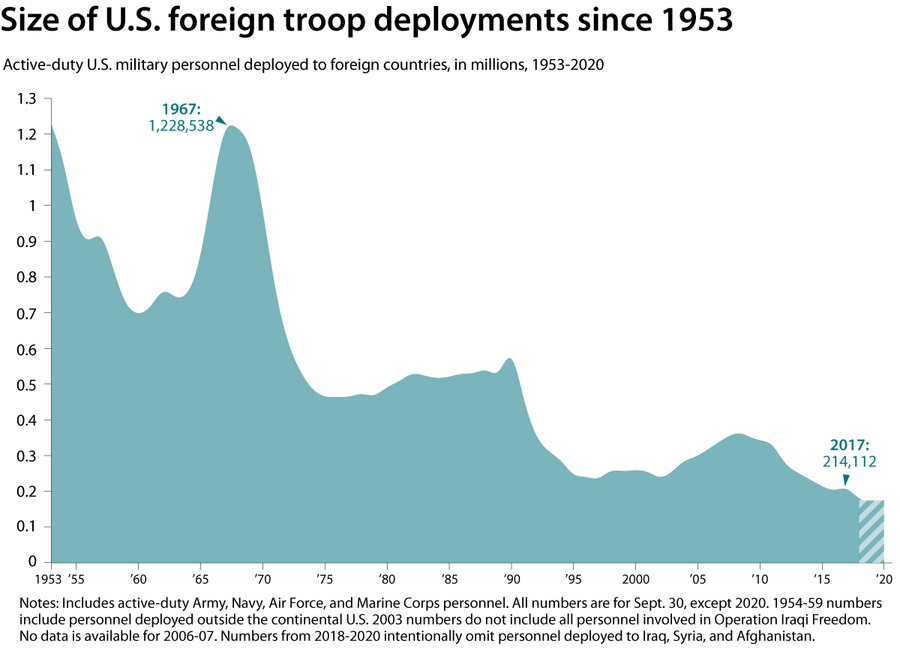

Long gone are the days of the early 1950s, when the U.S. was committed to defend 42 nations, and stationed more than 1 million soldiers at more than 800 bases in 100 countries.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, U.S. foreign policy has been marked by two costly and largely unsuccessful military adventures in Afghanistan and Iraq. Those setbacks for the brand of aggressive internationalism espoused by President George W. Bush led Mr. Obama to rein in American ambitions; he refused to take the decisive stand in Syria that might have saved the uprising against Bashar al-Assad and his Russian backers, and he took a back seat in the British and French-led campaign to oust Muammar Qaddafi in Libya.

His approach became known as “leading from behind.” It reflected Mr. Obama’s sense that U.S. power was declining relative to nations such as China, and it allowed more space for allies to act. But they have proved unable to fill the vacuum.

Now President Trump is taking the U.S. pullback from the world much further – and doing it in a way that is more disruptive and whose outcome is less predictable.

A weaker equation

The most recent international door that Mr. Trump has slammed is at the World Health Organization (WHO). The U.S. president said in May that Washington would be “terminating our relationship” with the United Nations health agency because China enjoyed too much influence there.

But on his first working day in the Oval Office in January 2017, Mr. Trump was already displaying similar instincts, pulling Washington out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a 12-nation free trade pact linking Asia with the Americas.

Everyone thought that without the U.S. the deal would collapse. Some participants feared U.S. retaliation if they went ahead. But other nations pursued their project regardless, and a new version of the pact came into force two years later.

The TPP would have included nations that make up 40% of the world economy; the new agreement encompasses only half that. “When you take the world’s largest economy out of the equation, the numbers don’t look as good,” says Deborah Elms, who heads the Asian Trade Centre, an advocacy group in Singapore.

“It would be much better for everybody if the U.S. was still in,” Dr. Elms adds. The trade deal works and offers “substantial benefits” to its members, she says. But without Washington as a driving force, “it hasn’t had quite the traction it should have done.”

Another international trade body that has no traction at all at the moment because of a U.S. boycott: the appellate body of the World Trade Organization, the ultimate arbiter of global trade disputes. But other WTO members are trying to kick-start an alternative system.

Washington has long been calling for reform of the WTO. In characteristic style, Mr. Trump backed his preference for bilateral trade deals over multilateral affairs with a threat – to veto all nominations to the seven-judge appellate body and thus disarm it. The U.S. has indeed vetoed all appointments to the WTO’s supreme panel since 2017.

As judges have retired without being replaced, the body has been heading into a wall: It needs three judges to make rulings, but since last December it has had only one sitting member. That means that any appeal pushes a case into limbo.

“The U.S. has driven this organization in the past,” says one official familiar with WTO activities but who is not authorized to speak publicly. “To have the founding member suddenly do a 180-degree turn has shocked a lot of people.”

But not shocked them into silence. Led by the European Union, 20 WTO members have employed a rarely used rule to set up a parallel appeals procedure, a “multiparty interim appeal arbitration arrangement,” that went into operation at the end of April. Including major trading nations such as China and Brazil, the group is responsible for about half of all trade disputes brought to the WTO since its founding 25 years ago.

“This arrangement is a stopgap solution that will be used only until a reformed appellate body is again fully functional,” insists EU Trade Commissioner Phil Hogan.

Paolo Garzotti, an EU trade negotiator in Geneva, echoes this point. “The interim arrangement is like an intensive care unit while we wait for a vaccine, which would be a solution to the appellate body issue,” he says.

In the longer term, if the U.S. cannot be tempted back into the organization, the WTO’s future as the rule-setter for world trade is uncertain. Given Beijing’s protectionist tendencies and other policies, “there is not a huge demand to have China become a leader of the organization,” says the official who was not authorized to speak publicly. “And the EU has difficulty getting its act together.

“It’s a vacuum here,” he laments.

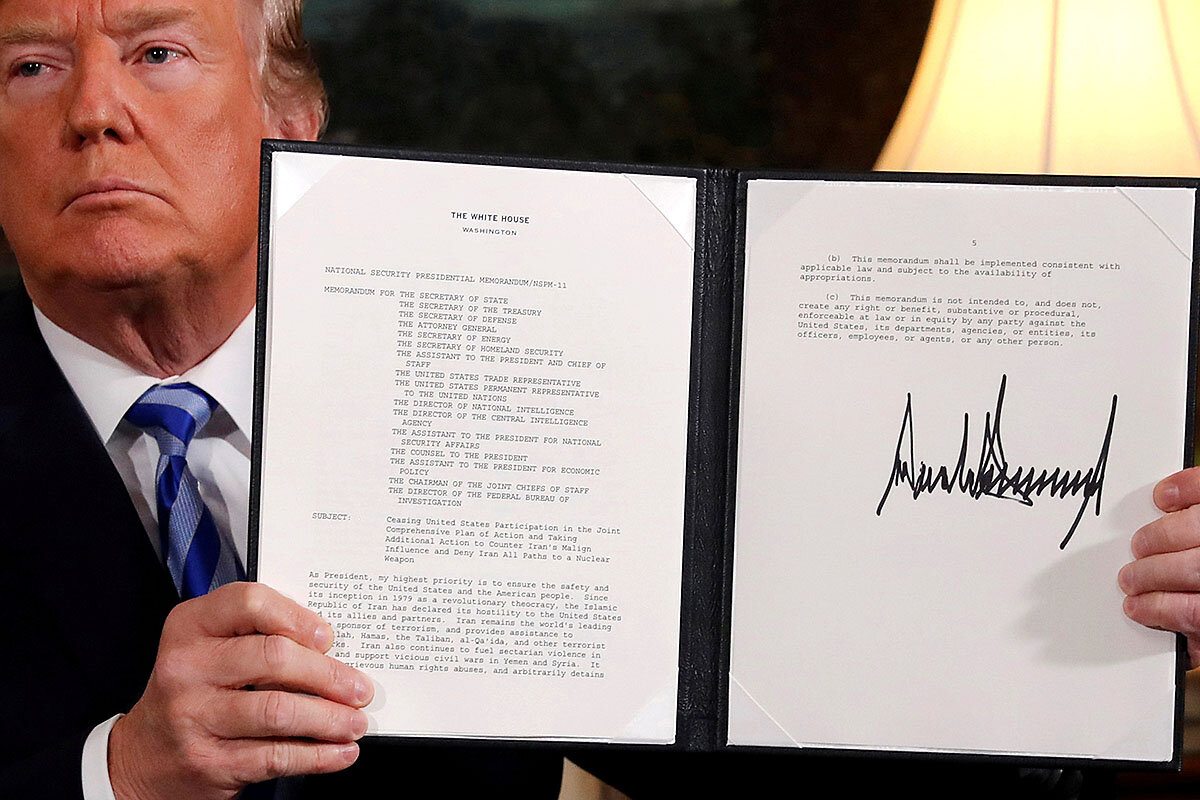

The Iran nuclear deal

One of the most prominent issues on which President Trump has abandoned America’s partners, leaving them to see what they could salvage, is the 2015 deal under which Iran agreed to severely restrict its nuclear program in return for an easing of international economic sanctions.

Branding it “the worst deal ever,” Mr. Trump pulled the U.S. out of the agreement in 2018, arguing that it only postponed Iran’s nuclear ambitions, did not prevent it from building ballistic missiles, and allowed Tehran to fund Washington’s enemies in the Middle East. The U.S. has since imposed a series of new sanctions on Iran.

The sanctions are so harsh – banning oil sales and prohibiting Iran from purchasing U.S. dollars, among other measures that Washington calls a policy of “maximum pressure” – that some observers think they are designed to provoke Tehran into withdrawing from the accord. That is an outcome the other international signatories to the deal – China, Russia, France, the United Kingdom, Germany, and the EU – are anxious to avoid. But they are unable to offer Iran much relief from the unilateral U.S. sanctions.

That’s because Washington has also imposed extraterritorial secondary sanctions on any government or company that trades with Iran. That means the U.S. government could not only ban anyone trading with Iran from doing business in the U.S.; it could also seize their assets there and cut off their access to financial markets.

Washington “has bullied other countries into capitulating” because American domination of financial markets and control of the U.S. dollar puts it in the driver’s seat, says Ellie Geranmayeh, an Iran expert with the European Council on Foreign Relations in London.

“The U.S. financial hold is so strong ... that no company in Europe will dare engage in any activity sanctionable under U.S. law,” Ms. Geranmayeh adds.

The EU has tried to make an end run around the U.S. sanctions by setting up a special barter-based trading system with Iran, called Instex, that shields European companies from prosecution in the U.S. But it has effected only one deal so far and is limited to food and medicine, which are already not subject to sanctions.

Yet Instex has been important politically: The goodwill gesture gives Iran a reason to stay in the deal, even if Tehran says it no longer feels bound by the nuclear agreement’s terms.

“We have a very messy deal on life support,” says Ms. Geranmayeh. “Instex is a Band-Aid to prevent the deal from falling apart. ... Everyone is waiting to see if there is any change after November,” when the U.S. presidential election is held.

“It’s a deal in name only,” she adds. “It is in play, but neither Iran nor the international community are getting what they wanted.”

The climate factor

There is probably no global threat that demands united action as much as climate change. So when Mr. Trump announced in 2018 that he was pulling the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement to combat global warming, it was an especially heavy blow.

“No matter what the rest of the world does,” warns Meenakshi Raman, an activist with the Third World Network, a Malaysia-based think tank, “if the U.S. refuses to play ball it will be very difficult to reach the target” set in Paris of limiting global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius.

In one sense, the fact that the U.S. government is no longer bound by its Paris Agreement commitments to lower greenhouse gas emissions is unimportant.

“The U.S. has withdrawn from the agreement but it has not withdrawn from reality,” points out Pascal Canfin, chair of the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety Committee of the European Parliament. “Its companies have not withdrawn from the energy market or the race for clean energy sources.”

Climate change, Mr. Canfin adds, is a matter of insulation in buildings, transport exhaust, and energy generation. “The main battle is industrial,” he says, “and if U.S. companies are not incentivized or forced to move, other countries will have the technology and the patents and set the standards.”

At the same time, the U.S. federal government is not America. Thousands of American cities, states, and businesses have signed on to the “We’re still in” campaign, pledging to meet the commitments Washington made in Paris in 2016. Together, they account for two-thirds of U.S. gross domestic product, two-thirds of its population, and more than half of its carbon emissions, says Kevin Kennedy, a senior fellow at the World Resources Institute, a Washington-based think tank.

But there is only so much they can do, cautions Mr. Kennedy. “If we are really aiming for net-zero carbon emissions by midcentury,” he says, “the federal government will be critical.”

As the world’s second largest carbon emitter, the U.S. is also critical to the diplomatic process, built on the Paris deal, to encourage governments to set more ambitious targets for lowering greenhouse gas emissions. Around the edges, the countries remaining in the Paris Agreement (none have followed the U.S. out the door) can make up for Washington’s absence. Last year, for example, when it came time to replenish the Green Climate Fund, which helps developing countries mitigate the effects of climate change, a number of European countries doubled their contributions to compensate for the lack of U.S. support.

But no government is willingly going to set carbon emissions targets that will inevitably increase its companies’ costs of production unless other governments pledge to do so as well. “You need a global framework so as to go beyond the low-hanging fruit and take action that reduces your competitiveness,” argues Emmanuel Guérin, a former French diplomat who led the team that drafted the Paris Agreement.

At the heart of that framework will have to be the world’s two largest carbon emitters, China and the U.S. “To move climate negotiations forward, you first need the basic foundation of a deal between China and the U.S.,” says Mr. Canfin.

If that proves impossible, Europeans are themselves looking to China. “If the EU and China really set the direction in a very clear way, agree to strengthen climate targets, and cooperate, that would send a very strong signal to the world,” suggests Mr. Guérin.

For the time being, though, all eyes are on November. Explains Mr. Canfin, “We need to keep all our options alive, waiting for Mr. Trump not to be reelected.”

Who is indispensable?

Madeleine Albright, former President Bill Clinton’s secretary of state, used to refer to the U.S. as the “indispensable nation.”

Nothing could be further from President Trump’s conception of U.S. responsibilities to the world, where he sees Washington’s role as limited to defending U.S. citizens and promoting their interests.

“We are not the policemen of the world, but let our enemies be on notice,” he told graduates of the U.S. Military Academy in West Point, New York, in June, “if our people are threatened we will never ever hesitate to act.”

The “job of an American soldier is not to rebuild foreign nations,” he added, “but to defend ... our nation from foreign enemies.”

The U.S. economy is still the largest in the world, however, and Mr. Trump commands the world’s most powerful military. Nor is he shy about using those strengths when it suits him, such as to impose secondary sanctions on companies dealing with Iran, or dispatching a drone in January to assassinate Qassem Soleimani, a top Iranian general.

In June, he imposed economic sanctions and visa restrictions on officials of the International Criminal Court involved in investigating allegations of war crimes in Afghanistan, including those made against U.S. soldiers.

What has changed since Ms. Albright’s day, says Mr. Burns, who was her spokesman, is that the U.S. is no longer alone in being indispensable: It has been joined by the EU and China.

The trouble with that, points out Mr. Mounk at Harvard University, is that “China does not want to, and Europe is not able to” play the role that the U.S. has played for more than 70 years.

The Chinese government has certainly sought to profit from American discomfiture over COVID-19, trumpeting its own record in confronting the pandemic. But Chinese officials also covered up early signs of the disease, allowing it to spread.

Beijing has shown no signs of seeking, let alone exercising, global leadership in the fight against COVID-19, besides ensuring that every delivery of Chinese medical equipment abroad attracted maximum publicity.

In the U.N. Security Council, China and the U.S. even blocked the passage of a resolution calling for greater international cooperation in the fight against COVID-19 and for cease-fires in ongoing conflicts because they disagreed about a reference to the WHO.

On the broader stage, the U.S. has traditionally bolstered its international appeal by standing, albeit sometimes on feet of clay, for democracy and human rights. China’s model of governance, founded on political repression, appeals to few except the autocratic rulers who share its values.

Defense Manpower Data Center

The other candidate to fill U.S. shoes, the EU, is mightily divided – between East and West politically, and North and South economically. That lack of unity undermines the sense of common purpose the EU would need to impose itself comprehensively on the world stage.

There have been some bright spots during the COVID-19 crisis. Central bankers around the world have worked together to hold the global economy together; scientists are collaborating in the search for a vaccine; an EU-sponsored pledging conference in May had no difficulty in raising $8 billion to help fund that search, even though Washington stayed away.

On the diplomatic front, the Group of 20 agreed in March to pump $5 trillion into the world economy. And at the WHO, the EU managed to bridge the widening gulf between China and the U.S. to broker an agreement about an independent inquiry into the origins and handling of the first COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China.

But the general landscape of international cooperation and action in Washington’s absence is bleak. Beijing and Washington have preferred to score points off each other rather than work together; EU members each chose their own response to the pandemic, and are struggling now to unite around a recovery plan; Africa, Latin America, and Asia have been left to fend for themselves.

“When the U.S. opts out,” says Mr. Burns, “it makes it very difficult for the rest of the world to be effective.”

Gallup

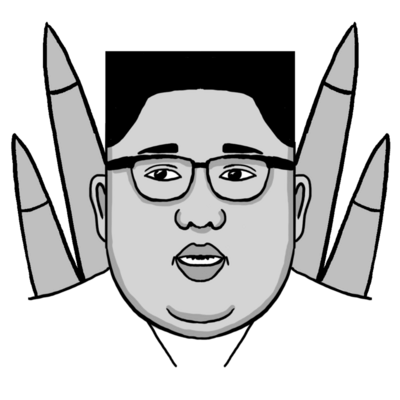

North Korea and US: Is it back to square one, only worse?

President Trump’s outside-the-box approach to North Korea earned praise for temporarily lowering tensions. But has it materially changed the national security challenge confronting the United States?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

After the collapse last year of the second summit between President Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un, North Korea retreated to the background of the world stage. The North ultimately balked at the U.S. demand for full denuclearization before economic sanctions relief.

But North Korea “does not like to be ignored,” notes Bruce Klingner, a Heritage Foundation research fellow and former CIA analyst, especially when it wants something very much, such as relief from punishing U.S. and international economic sanctions. And so, in recent weeks, Pyongyang has launched a series of provocations aimed at alarming and punishing both South Korea and the United States.

When President Trump took office, North Korea was what his predecessor, Barack Obama, characterized as America’s gravest national security challenge. Has that changed?

“Whoever is in the Oval Office next January, where North Korea figures on the list of national security threats will largely depend on whether North Korea is acting up and forcing some kind of response,” says Mr. Klingner. “But it won’t exactly be back to where we were,” he adds, “because both [the North’s] nuclear and missile capabilities are higher – in both quality and quantity – than they were in 2017.”

North Korea and US: Is it back to square one, only worse?

On Inauguration Day 2017, when Barack Obama ushered Donald Trump into the Oval Office, the outgoing president had a blunt warning for his successor concerning North Korea.

The volatile and unpredictable dictatorship with a nascent nuclear arsenal and an intercontinental missile program nearing an ability to reach the continental United States would be the new president’s gravest national security challenge, Mr. Obama cautioned.

Now 3 1/2 years later, and as the 2020 presidential election gears up, many Northeast Asian experts say the same warning Mr. Obama offered President Trump is very likely to apply for whoever occupies the Oval Office on Inauguration Day 2021 – whether it’s Mr. Trump settling into a second term, or former Vice President Joe Biden moving up to the top job.

Indeed, after Mr. Trump’s unorthodox diplomatic approach to the North Korea of Kim Jong Un, which temporarily lowered tensions but failed to move the country toward denuclearization, it’s essentially back to square one with Pyongyang, some experts say.

That is, with one big catch.

“We are basically back to square one – only in some cases it’s worse,” says Frank Aum, a former Pentagon senior adviser on North Korea who is now senior expert on North Korea at the U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP) in Washington. He notes the North Koreans are quietly amassing more fissile material every year – enough to build seven to 12 nuclear bombs annually, experts estimate – and are steadily improving their intercontinental ballistic missile capabilities.

“So they have all that,” he adds, “but we don’t have anything to show for the last 3 1/2 years in terms of denuclearization.”

Others bluntly deem the “back where we started” characterization inaccurate and even dangerous, because it fails to take into account the North’s significant nuclear and missile progress – and fails to recognize that four more years of Pyongyang as a de facto nuclear power is not likely to make the North any more likely to negotiate away its nuclear status.

“Whoever is in the Oval Office next January, where North Korea figures on the list of national security threats will largely depend on whether North Korea is acting up and forcing some kind of response,” says Bruce Klingner, a former CIA Korea analyst who is now a senior research fellow for Northeast Asia at the Heritage Foundation in Washington.

“But it won’t exactly be back to where we were,” he adds, “because both [the North’s] nuclear and missile capabilities are higher – in both quality and quantity – than they were in 2017.”

Series of provocations

With the world preoccupied with the coronavirus pandemic, North Korea had receded to the background of the global stage, an ignominious spot it retreated to after the collapse of the second Trump-Kim summit in Hanoi, Vietnam, last year. The North ultimately balked at the U.S. demand for full denuclearization before economic sanctions relief.

That summit appeared to end the “love” Mr. Trump had said existed between the two leaders.

But as Mr. Klingner notes, the North “does not like to be ignored,” especially when there is something – in this case relief from punishing U.S. and international economic sanctions – it wants very much. And so, in recent weeks, Pyongyang has launched a series of provocations aimed at alarming and punishing both South Korea and the U.S.

Last week Pyongyang rattled Northeast Asia – and Korea watchers in the U.S. – by blowing up the inter-Korean liaison office in the border town of Kaesong. The North closed off all communication lines with the South, and threatened to send troops into border cooperation zones and remilitarize the Demilitarized Zone between the two Koreas.

On Tuesday Pyongyang did an abrupt about-face and announced suspension of its military plans against the South – a move analysts summed up as typical “keep them guessing” behavior.

But it did not signal a significant rhetorical softening toward Seoul and Washington.

On Thursday, Pyongyang chose the 70th anniversary of the start of the Korean War to attack “hostile policy” from the U.S., saying it has had no choice but to counter “nuclear with nuclear” and make that a cornerstone of its national security policy.

Sister act

The recent harsh pronouncements have coincided with the emergence and expanding public profile of Mr. Kim’s sister, Kim Yo Jong, as a hard-liner with strengthening links to the military.

Ms. Kim was trumpeted as the Ivanka Trump of the Kim regime when she appeared – impeccably dressed and with expensive designer bag in hand – to lead the North’s delegation to the Seoul Olympics in 2018. But her transformation from fashion plate to tough-talking leader in her own right may be a kind of insurance policy for the Kim regime’s survival, given Mr. Kim’s suspected precarious health, some experts say.

It may also be a message both to North Koreans and to the world that the family-based regime is here to stay – and still has the wherewithal to unsettle neighbors and superpowers alike.

Signs have grown recently that a jilted Mr. Kim intends to remind Mr. Trump that the two countries have unfinished business – and that Pyongyang has tricks up its sleeve to influence the U.S. election if it chooses to use them.

Earlier this month the North’s foreign minister, Ri Son Gwon, issued a blistering critique of Mr. Trump’s summit diplomacy, calling it “nothing but a foolish trick hatched to keep [Pyongyang] bound to dialogue” and to skew “the political situation and election in the U.S.”

“Never again,” he added, “will we provide the U.S. chief executive with another package to be used for achievements without receiving any returns.”

To the extent that foreign policy emerges as a major factor in the presidential campaign, Mr. Trump will be able to claim the U.S. benefited from his outside-the-box approach to North Korea, some analysts say. After the initial “fire and fury” stage of his engagement with the North, the spectacle of the 2018 Singapore summit did lead to reduced tensions, a hiatus in weapons and missile testing, and Mr. Trump’s assurance to Americans that they could “sleep well at night.”

Even some big names in national security issues have recently come out in support of the president’s effort to do something different. In his new book, “Exercise of Power,” former Defense Secretary Robert Gates says he supported Mr. Trump’s summit diplomacy because “every other effort to limit the North Korean nuclear capability over the last 25 years” had failed.

October surprise?

Still, Pyongyang may have no intention of sitting passively in the plus column of the president’s foreign policy achievements.

Heritage’s Mr. Klingner says he has never seen such direct and repeated referencing of U.S. elections by the North, a development he believes could mean the North is considering a splashy move – perhaps around October? – to try to act as a spoiler in the presidential election.

Mr. Aum of USIP differs with that assessment, noting that while he believes the North could continue with minor provocations in the coming months to let the world know it can still cause a ruckus, he does not expect any crossing of “red lines” – like a nuclear test or an intercontinental missile launch – that could lead the world to impose even more sanctions.

Whoever ends up in the Oval Office next January, Mr. Aum says the lesson of the last four years will not be that trying something new with North Korea was a mistake, but rather that a combination of “superficial” summits with all-or-nothing U.S. policies was a recipe for failure.

“We shouldn’t fault the president’s outside-the-box approach to North Korea for why we got nowhere,” he says, “but we should be critical of the way that out-of-the-box diplomacy was carried out.”

The combination of “reality-TV diplomacy based on personalities” and “the maximalist demands that [the North] give up all of its nuclear program before getting any sanctions relief” was not a productive match, Mr. Aum says. “That was never going to work.”

For migrant farmworkers, coronavirus adds new burdens

The United States relies on 2.4 million farmworkers to harvest everything from blueberries to lettuce. This year they’re confronting extra risks tied to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Lee A. Dean Correspondent

In western Michigan’s Oceana County and beyond, the coronavirus is complicating the lives of the workers who pick America’s fresh produce. For Yesenia Madrigal and her family, it means she has been unable to work because she’s caring for young children who haven’t been able to attend school or day care.

That comes alongside all the other variables for the permanent U.S. residents, as well as a rising number of guest workers, who do this work. In Michigan an early May freeze postponed the asparagus harvest, which in turn caused an income gap for the labor crews.

The combination of the late harvest, the pandemic, and a delay in unemployment benefits wrecked the Madrigal family’s careful financial plans. After their savings were eroded, they were forced to sell one of their vehicles.

Their story reveals the heightened economic challenges, as well as health risks, that farmworkers face this year. “I give my boys jobs and things to do throughout the week,” Ms. Madrigal says. “But it’s not the same” as when school or day care are open.

For migrant farmworkers, coronavirus adds new burdens

When Yesenia Madrigal and her family planned their annual trip from Florida to Oceana County, Michigan, they thought their travels as a seasonal farmworker family would proceed as in years past. They would arrive in time for the May asparagus harvest, take a short break, and then plunge into the tree fruit season before returning to Florida. Their children would be able to go to schools and Head Start programs while she, her husband Lazaro, and 22-year-old son Hector Vasquez were earning money.

Not so in 2020. COVID-19 and the resulting stay-at-home orders provided a one-two punch of setbacks to the Madrigal family and added extra pressure to the migrant farm labor system for workers and employers alike.

“When I first heard about [COVID-19], I thought, ‘OK, the kids won’t be in school and that’s a big deal.’ I have a 2-year-old and he couldn’t go to day care. So I would have to stay home and that means I wouldn’t be able to go to work,” Ms. Madrigal says.

There are an estimated 2.4 million seasonal farmworkers in the United States, including permanent residents, “follow the crop” workers such as the Madrigal family, and workers who come to the U.S. from other countries. Those workers come from Mexico, Central America, Jamaica, and as far away as South Africa.

In the current pandemic, even as food-industry workers such as grocery clerks have gained public attention for providing “essential” services, seasonal farmworkers remain largely out of the limelight. They’re tasked with picking much of America’s food, while facing heightened challenges and health risks due to the coronavirus.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

And they are doing this difficult work for low pay. Average pay for farmworkers in 2019 was $13.99 per hour – 60% of what U.S. production and nonsupervisory workers outside of agriculture averaged, according to analysis by the Economic Policy Institute. For the rising share who come to the U.S. on a guest-worker basis, the federally set minimum ranges by state from $11.71 to $15.83 an hour, after a proposed reduction was averted this spring.

“Essential farm workers continue putting food on our tables, but too often can’t feed their own families,” United Farm Workers President Teresa Romero said in a statement released early this month. “We will keep pushing for urgently needed remedies,” she said, such as paid sick leave regardless of the size of an employer.

Here in west Michigan’s Oceana County, an early May freeze added an extra layer of distress to both growers and farmworkers. The freeze forced asparagus growers to cut off and discard the damaged spears and then wait for them to grow again to the height required for sale to the fresh market. The delay in turn caused an income gap for the labor crews.

Eroded savings and added duties

The combination of the late start of harvest, the pandemic, and a delay in the arrival of unemployment benefits – which had still not arrived as of June 10 – wrecked the careful financial plans put in place by the Madrigal family that normally guide the transition as they head north. After their savings were eroded, they were forced to sell one of their vehicles.

From there, it has been a waiting game until an overburdened state of Michigan unemployment system could provide benefits. Until children could return to schools and day-care facilities, Ms. Madrigal, a U.S. citizen, had to care for her sons who are too young to work in the fields and keep them occupied while fending off boredom.

“Thank God they’re good kids,” she says. “I keep them busy. My 2-year-old is having a hard time with speech, but with me being home, I have been helping him with that. I give my boys jobs and things to do throughout the week. But it’s not the same as being in school.”

As harvest season ramps up nationwide in a time of pandemic, worker safety becomes an even more pressing concern. Because of food safety regulations, some workers were already required to wear personal protective equipment (PPE), including masks and gowns, before COVID-19. Social distancing is easier to achieve during outdoor work, depending on row spacing and the distance between fruit trees and bushes. Social distancing becomes more challenging indoors, where areas such as packing and inspection lines traditionally have people working in close proximity.

For seasonal farmworker service provider organizations, 2020 has meant finding new ways to help clients. Telamon, a nonprofit that provides educational services to farmworker families, has not yet gained governmental approval to open its 13 Head Start centers.

Donald Kuchnicki, workforce and career services director for Telamon in Michigan, said the organization has been getting ready for the day the centers can reopen. Staff have been busy ordering supplies, cleaning and sanitizing, and establishing best practices to monitor for the virus.

“We’ve been reaching out to the farmworker families as they return to the area. It’s really been a struggle with the families that want the centers to be open, but we have to be measured in our approach,” Mr. Kuchnicki says.

The virus has introduced a stark risk assessment into the lives of workers and their families, as they balance the need for income against the risk of a serious illness that has hit some farmworker communities hard.

“If you’re feeling sick, are you going to let someone know or are you going to keep that to yourself? If you test positive, the last thing you want to do is bring attention to yourself,” Mr. Kuchnicki says.

Farm businesses such as the Scaroni Family of Companies, which operates farms in the western United States, say they are following Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines on social distancing and PPE. The farms instruct their workers on how to use masks and gloves and on proper sanitation procedures in the fields and in housing. In-field leafy green harvesting and packing machines now include plastic barriers between workers.

Uncertainty for farmers

The industry is grappling with uncertainty on many fronts, from shifting demand (as restaurants curtailed operations) to an already tight supply of agricultural workers. In some cases, workers have been unable to come to the U.S. due to problems obtaining visas and restricted air travel. Some farmers, meanwhile, have adjusted their crop mix this year to be less labor-intensive.

“For the most part, it seems that as long as they can get workers, they’re going to try and harvest the crops they’ve historically produced,” says Michael Marsh, executive director of the National Council of Agricultural Employers. “Farmers are very innovative in finding solutions. They’ve rolled with this and done as well with it as they can.”

The workers and their allies are also trying to cope, day by day.

“We want to open up the Head Start centers when appropriate, but we want to make sure it’s in the best interests of the families,” Mr. Kuchnicki says, noting that services will probably be offered in smaller classroom groups. “There are so many moving pieces that it makes the situation challenging.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Tourist treks helped save gorillas. What happens in lockdown?

Wildlife tourism has come to seem like an all-around win: for animals, surrounding communities, and visitors. Its history isn’t so simple, though, and COVID-19 has exposed more challenges – but also calls for change.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

Ryan Lenora Brown Staff writer

In recent years, a quarter of new jobs have been in tourism. And in Africa, more than a third of travel jobs are in wildlife tourism – helping to support threatened animals and the human communities that surround them.

Now, the sudden crash of the travel sector amid COVID-19 has led to a moment of reckoning. Funds for mountain gorilla conservation, for example, come in large part from the pricey tickets visitors buy for “gorilla treks” in Uganda, Rwanda, and Congo. And while conservation has a troubled history here, ecotourism has also benefited local residents with new jobs and revenue-sharing agreements. Today, with parks shuttered, money has evaporated for thousands of guides, hotel workers, cooks, cleaners, and souvenir saleswomen.

So as tourism dries up, experts have begun to call for policies to make future crises less catastrophic.

“Tourism has transformed conservation in Africa, but we see now that tourism is not a silver bullet,” says Alice Ruhweza of the World Wildlife Fund. For the continent’s wildlife and the people who depend on it, she says, conservationists will have to find new and more diverse sources of funding to protect them.

Tourist treks helped save gorillas. What happens in lockdown?

It’s hard to imagine a wildlife encounter more intimate than what tourists experience in Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable Forest. Families of mountain gorillas saunter past visitors on their oversized knuckles, seemingly unconcerned by their human observers. Baby gorillas climb and tumble over their parents in the grass. Adults recline in the thick brush like men sprawled out for Sunday football on a La-Z-Boy recliner.

For visitors, gorilla treks are often a bucket list highlight, a once-in-a-lifetime chance to get up close and personal with one of humanity’s closest relatives, with whom we share 98% of our genetic material. But the biggest value of tourism is to the gorillas themselves. Since treks began in Rwanda in the late 1970s, they have become a crucial part of saving mountain gorillas from their poaching-driven slide toward extinction. Today, they are the only great apes whose population is growing. And while conservation has a troubled history here, in recent years ecotourism has often benefited local residents too, creating jobs and providing cash in revenue-sharing agreements to poor communities near national parks.

But now, both the gorillas and their human neighbors face a new threat: the sudden decline of tourism in the wake of the coronavirus. Since the disease began to spread in east Africa in March, the parks where tourists can visit gorillas in Uganda, Rwanda, and Congo have been shuttered. Funds for gorilla conservation have evaporated, along with the cash that helped thousands of guides, hotel workers, cooks, cleaners, and souvenir saleswomen keep their families afloat. Early this month, a gorilla named Rafiki was killed in Bwindi by men who say they stabbed the animal in self-defense while illegally subsistence hunting – the first such killing in nearly a decade.

Travel and tourism account for more than 10% of the world’s gross domestic product, and in recent years, one in four new jobs on our planet was in tourism. Across the world, wildlife tourism supports nearly 22 million jobs, and in Africa, more than a third of all travel jobs are in wildlife tourism.

So here, more than perhaps anywhere else in the world, the sudden crash of the tourism sector has led to a moment of reckoning. “Tourism has transformed conservation in Africa, but we see now that tourism is not a silver bullet,” says Alice Ruhweza, the Africa regional director for the World Wildlife Fund. For both the continent’s wildlife and the people who depend on them, she says, conservationists will have to find new and more diverse sources of funding to protect them.

Sudden collapse

In much of Africa, conservation has leaned heavily on tourism for decades. And that history has, at times, been a dark one. Indigenous communities were displaced in the creation of most of the world’s national parks, including tens of thousands of people in Africa. In the gorilla habitat that straddles Rwanda, Uganda, and Congo, communities of Batwa, a regional ethnic minority, have become so-called “conservation refugees,” violently removed from their ancestral lands to make way for parks to protect the gorillas and other animals. Today, the Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) gives communities neighboring its parks 20% of gate entry fees, plus $10 from every $700 permit purchased by tourists to trek with gorillas. This money has gone to building schools and health centers, among other community projects. But most Batwa in particular continue to live in dire poverty.

Still, the parks have become crucial in conservation efforts, drawing growing numbers of mostly international tourists willing to pay big money to have up-close encounters with gorillas. By 2018, mountain gorillas were downgraded from “critically endangered” to “endangered”: a result, in part, of the attention and money brought by tourism. Today, there are about 1,000 living in the wild – just under half of them, 459, in Bwindi, according to the 2019 census conducted by the Greater Virunga Transboundary Collaboration.

Between 2018 and 2019, those 459 gorillas received more than 37,000 visitors, according to the UWA, each paying $700 for the privilege of a one-hour trek with the primates. (Tourists in Rwanda pay $1,500 for the same experience, and the price is $400 across the border in Congo).

Those visitors also spent time in local lodges, frequented local restaurants, and bought carved wooden gorilla sculptures from local women.

Until suddenly this March, all that was gone.

One day, Ivan Batuma was prepping Rushaga Gorilla Camp, the rustic lodge clinging to the edge of a hillside near Bwindi that he manages, for another batch of visitors. The next, Mr. Batuma, who also sits on the board of the UWA, was laying off half his staff and scrambling for an alternate source of income.

“I don’t expect income from my hotel in the near future,” he says. “I am looking at having [international] guests [next] March at the earliest.”

“One way to think about tourism is this – when the center collapses, everything else collapses around it,” says Judy Kepher-Gona, the founder of Sustainable Travel and Tourism Agenda, a tourism consultancy based in Nairobi. “If you had 10,000 people relying indirectly on tourism for their incomes, then all at once you can have 10,00 people out of a job.”

New vision?

So as parks around the continent have closed, she says, tourism experts have begun to call for policies to be put in place to make future crises less catastrophic.

One way to do that, Ms. Kepher-Gona says, is to require that governments and private parks funnel tourism dollars not simply into aid projects for local communities, but also into helping them jumpstart industries unrelated to tourism – like farming or manufacturing.

“Ultimately it doesn’t serve anyone for local communities to be so dependent on foreign tourists,” she says. “Making the communities around you resilient is good business.”

Amid the pandemic, “there are even more pressing reasons to invest in communities that protect nature through wildlife tourism and conservation,” wrote Midori Paxton, head of ecosystems and biodiversity at the United Nations Development Program, in a recent piece on the UNDP website. “COVID-19 recovery packages must include this investment” to protect people’s economic and physical well-being, she argued.

For now though, communities around Bwindi are waiting for their source of income to return. In the park itself, rangers slip on face masks, squirt sanitizer onto their hands, and head out to visit the gorillas, so that they won’t become unaccustomed to human contact and migrate elsewhere. Because gorillas share so much DNA with humans, they are susceptible to human diseases like COVID-19 as well, and staff here are worried that it may be a long time before it’s safe for tourists to interact with them again.

For now, the rangers approach the gorillas like they would other people, keeping a distance of at least two meters – trying, in a difficult time, to continue being good neighbors.

On Film

Racial justice: Five eye-opening documentaries

Since the killing of George Floyd, there has been a concerted effort to better understand the Black experience – and documentaries can be crucial to that learning. In this column, Candace McDuffie identifies five films that chronicle injustice in the Black community, and whose messages are arguably more relevant than ever.

-

By Candace McDuffie Correspondent

Racial justice: Five eye-opening documentaries

As the United States continues to reel in the aftermath of George Floyd’s death, conversations about injustice in the Black community have permeated the zeitgeist. Close examinations of the role of white supremacy in every facet of American life, from the economy and politics to justice and education, are happening with more regularity.

In an effort to stand in solidarity with Black folks, there have been numerous calls to buy from Black businesses, read Black authors, and support Black art. As many look to media as a prominent vehicle for learning more about Black history, documentaries can be crucial in educating the public.

Over the last decade, there have been several that explore the political ramifications of anti-Blackness – and how Black people often pay with their lives. Below is a list of five powerful documentaries that bravely address the systems and institutions designed to oppress a vulnerable population.

“I Am Not Your Negro”

This critically acclaimed documentary, produced and directed by Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck, is about the life of novelist, poet, playwright, and activist James Baldwin. Actor Samuel L. Jackson narrates “I Am Not Your Negro,” which was inspired by Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript “Remember This House.”

Baldwin’s exploration of racial tension in America is eloquent yet brutal; he plainly expresses how the history of this country is rooted in anti-Black sentiment. Through various speeches and interview footage from television appearances, he explains the importance of Black liberation. Baldwin also shares how those who aimed to achieve it – like his contemporaries Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Medgar Evers – were murdered because of it. “The future of the Negro in this country is precisely as bright or as dark as the future of the country,” he states. (Rated PG-13; available on Amazon Prime Video, iTunes)

“13th”

Directed by Ava DuVernay, “13th” is a film that explores the epidemic of mass incarceration in America. Its title references the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude except as punishment for a crime. However, prisons are disproportionately occupied by people of color who are forced to work for the state under what many see as modern-day convict leasing – and as perpetuating slavery.

DuVernay also delves into how Black folks have been historically disenfranchised in this country, which includes everything from Jim Crow to the war on drugs targeting Black communities. This documentary focuses on a system that arguably demonizes minorities – and then uses their bodies for profit. (Rated TV-MA; available on Netflix)

“Whose Streets?”

This potent film chronicles the 2014 Ferguson, Missouri, uprising following the shooting death of Black teenager Michael Brown at the hands of a white police officer. Filmmakers Sabaah Folayan and Damon Davis went to Ferguson to speak directly to those protesting police brutality shortly after Brown’s death.

“Whose Streets” addresses how Black communities are subject to overpolicing and subsequent violence. It also zeroes in on the people at the epicenter of a revolution. Told by activists standing on the front lines, it is a must-watch documentary that covers the unrest in Ferguson with honesty, candor, and care. It also shows how the Black Lives Matter movement gained more momentum during this time. (Rated R; available on Amazon Prime Video, Hulu, iTunes)

“The Central Park Five”

“The Central Park Five,” directed by Ken Burns, Sarah Burns, and David McMahon, delves deep into the wrongful rape conviction of five Black and Latino teenagers from Harlem. The accused – Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Raymond Santana, Korey Wise, and Yusef Salaam – serve out their sentences in their entirety, ranging from six to 13 years, before another person confesses to the 1989 crime (DNA testing corroborated this admission).

The film examines how race and class – the victim was a white woman – publicly led to a guilty verdict long before the five were on trial. It is told from the perspective of the five men who describe how they were coerced into taking blame for a crime they didn’t commit. It also shows how the media, law enforcement, and social institutions went out of their way to persecute young boys of color.

Ava DuVernay’s Netflix miniseries, “When They See Us,” premiered in 2019 and was based on their story. (“The Central Park Five” is unrated; available on Amazon Prime Video, iTunes)

“LA 92”

The most extraordinary trait of this documentary is that there is no narration – just archival footage and images of the infamous 1992 Los Angeles riots. Although the brutal beating of Rodney King at the hands of four Los Angeles Police Department officers (who were acquitted of all charges despite the attack being caught on video) was the main catalyst of the uprising, there were other contributing factors: the shooting death of 15-year-old Latasha Harlins by a convenience store owner (who served no jail time), an economic recession, the drought in California. This very much mirrors the political and social unrest of today.

Directors T.J. Martin and Daniel Lindsay let the scenes speak for themselves, tracing the events from before the King verdict to the aftermath of the violent protests. “LA 92” is now more relevant than ever. (Rated R; available on Amazon Prime Video, Hulu, iTunes, Netflix)

Candace McDuffie is a culture writer for the Monitor. Her work has appeared in outlets including Rolling Stone, MTV, NBC News, and Entertainment Weekly. You can follow her on Instagram @candace.mcduffie.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A safe landing for Hong Kong’s democracy refugees

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In coming days, China’s rulers are expected to give final approval to a draconian measure that will end Hong Kong’s autonomy and allow the arrest of any pro-democracy activist in the territory. By some estimates, as many as 100,000 Hong Kongers will emigrate soon after. Millions more could follow. Where will all these freedom-seekers go?

While Britain and Japan have made moves to welcome some of the likely political refugees, perhaps the best landing spot will be Taiwan, only 400 miles away. Last month Taiwan’s president, Tsai Ing-wen, said that if democracies allow autocrats to advance abroad, “we are neglecting our own democratic values.”

On June 18, Taiwan took initial steps toward assisting the hundreds of Hong Kong protesters who have already fled to the island to avoid persecution at home. The government plans to open an office July 1 that will help them resettle, find a job, or study in Taiwan. The move is seen as preparation for eventually absorbing more people from Hong Kong.

A safe landing for Hong Kong’s democracy refugees

In coming days, China’s rulers are expected to give final approval to a draconian measure that will end Hong Kong’s autonomy and allow the arrest of any pro-democracy activist in the territory. By some estimates, as many as 100,000 Hong Kongers will emigrate soon after. Millions more could follow. Where will all these freedom-seekers go?

While Britain and Japan have made moves to welcome some of the likely political refugees, perhaps the best landing spot will be Taiwan, only 400 miles away. The island nation of 24 million has proved that Chinese Confucian culture and democracy are compatible. It needs young talent. The cultural is similar.

Yet most of all, Taiwan has shown moral courage in standing up to Beijing’s bullying. The independent island is often harassed by China’s military, hackers, and propagandists for not wanting to join the mainland. Last month Taiwan’s president, Tsai Ing-wen, said that if democracies allow autocrats to advance abroad, “we are neglecting our own democratic values.”

On June 18, Taiwan took initial steps toward assisting the hundreds of Hong Kong protesters who have already fled to the island to avoid persecution at home. The government plans to open an office July 1 that will help them resettle, find a job, or study in Taiwan. The move is seen as preparation for eventually absorbing more people from Hong Kong.

China refers to pro-democracy defenders in Hong Kong as a “political virus,” which translates as a threat to the survival of the Chinese Communist Party. By comparison, Ms. Tsai was handily reelected in a popular election last January. She projects her country as a “force for good” in the world. A measure of that good is the welcome mat being put down for Hong Kong’s freedom lovers.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Caring for others? Let inspiration lead the way.

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Michelle Boccanfuso Nanouche

Feeling stumped during her preparations for a hands-on test during her training as a Christian Science nurse, a woman turned to God for help.

Caring for others? Let inspiration lead the way.

A course I took while training to be a Christian Science nurse required designing a care procedure for bandaging. We had to execute the procedure within a specific period of time, while demonstrating gentleness and poise.

I love caring for others and took on the preparation for the test with gusto – that is, until I hit a roadblock. While I knew technically what to do, executing it with the requisite gentle care took me twice as long as the allotted time. I stayed up night after night reworking the scenario. There had to be an answer!

But the night before the test, I still hadn’t come up with a viable solution. I’ve found that faced with a problem of any kind, focusing on the problem itself tends to enlarge fear, which can confuse and lead to mistakes. So I turned my thought to God instead.

Christian Science explains that God is infinite Mind, whose intelligence and good ideas are reflected in each of us. So whatever the unique circumstance may be, the right answer is present and discoverable. The discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, wrote: “Mortals may climb the smooth glaciers, leap the dark fissures, scale the treacherous ice, and stand on the summit of Mont Blanc; but they can never turn back what Deity knoweth, nor escape from identification with what dwelleth in the eternal Mind” (“Unity of Good,” p. 64).

The Bible illustrates the quick and transformative effect of turning to divine Mind to find workable solutions. One example involves two followers of Jesus, Paul and Silas, who had been stripped, beaten, and thrown in prison. That night, as they prayed and sang hymns of praise to God, an earthquake struck, and suddenly all the prisoners were unbound and the prison doors were opened (see Acts 16:22-36).

Seeing those open doors, and fearing the prisoners had fled, a waking guard was about to take his life when Paul saved him by calling out that all the prisoners were still inside. The situation made such an impression on the jailer that he became a believer in God and Christ Jesus.

To me this illustrates that not all challenges are what they seem. Sometimes they enable us to practice a living faith that helps others to experience freedom and light, too.

In another Bible account, the Apostle Peter, too, was put in prison. The church prayed for his liberation. Then in the night, an angel woke him, removed his chains, and guided him step by step to the exit, where the gate opened by itself. The angel then accompanied him some distance to be sure he was safely out of prison (see Acts 12).

Peter’s story shows that no matter how cornered we may feel by a problem, the angels (or inspiration) of divine Mind are present and accessible to take us all the way to complete freedom and solutions.

So that night, I prayed and listened for God’s angel to lead me to a solution. As I did, an uncomplicated but effective way to care gently and properly for the test case came to me. When I performed it for the teachers the next day, I did it in the allotted time.

When I finished, the teachers told me that I had, in fact, misunderstood the assignment, which had involved bandaging only one leg, not two, as I had done. At first it seemed as though my preparation and prayer had been unnecessary, but it soon became clear that wasn’t the case. A month later, my first case in my practical training presented exactly the scenario I had executed for the test – bandaging two legs. My earlier prayers had led me to an approach that provided the needed care in half the usual time – a great kindness to the patient.

A willingness to persist past fear and confusion, and to turn to God for guidance, empowers us to minister to those in need. “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mrs. Eddy’s primary work on Christian Science, says, “Divine Love always has met and always will meet every human need” (p. 494). The divine Love that is God is also the infinite Mind that gives us exactly what we need at every moment. Whatever the circumstance, we can trust this loving Mind to guide us, step by step, to solutions.

A message of love

People-driven change

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Please come back Monday, when we examine the great face mask question, as COVID-19 caseloads rise in 29 states. And remember, for the Monitor lens on breaking news, check out our First Look page.