- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

100 million years and still kicking. Scientists awaken buried microbes.

“Life finds a way,” Jeff Goldblum famously said as Dr. Ian Malcolm in the 1993 film “Jurassic Park.” Indeed, that has been proved by science again and again. And yet again this week.

On Tuesday, researchers reported that they had discovered microbes that had been buried beneath the sea floor for more than 100 million years, and they were still alive.

Researchers had found life in deep sea sediments before, but, with few nutrients, that environment is not particularly friendly to biology.

To probe the boundaries of where life might survive, the international team of researchers led by geomicrobiologist Yuki Morono drilled into sediments east of Australia nearly 19,000 feet below sea level. Back in the laboratory, the team doused the clay samples they’d extracted with nutrients to see if they could “wake up” any dormant microbial life that might be contained there. Indeed, from within the ancient sediments, a plethora of bacteria awoke.

The scientists aren’t sure what the microbes have been doing all that time.

Regardless, “Maintaining full physiological capability for 100 million years in starving isolation is an impressive feat,” University of Rhode Island oceanographer Steven D’Hondt told Reuters. Dr. D’Hondt is also a co-author on the new study. “The most exciting part of this study,” he said, “is that it basically shows that there is no limit to life in the old sediments of Earth’s oceans.”

In other words, life finds a way.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Signs of hope for troubled Afghanistan peace talks?

Afghanistan’s years of fighting have made peace a tough sell. Yet cause for optimism can be found, including with one hardened Taliban fighter the Monitor has tracked.

Is Afghanistan witnessing a change in thinking that could finally yield progress toward peace? Analysts point to a new coalescing of calculations focused by renewed U.S. pressure and leavened by the recognition there may be a limit to leverage gained by violence.

After five months of delay and continued killing, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani announced Tuesday that the government would soon complete a mass prisoner release and that direct talks with the Taliban would start in a week. The Taliban stated Thursday it would complete its own release of prisoners before starting a three-day cease-fire to mark the Eid holiday, which begins Friday.

To be sure, skepticism abounds. The Taliban are highlighting the cease-fire “as the greatest favor they can give to people,” says Orzala Nemat, a Kabul-based analyst. What the United States has gained so far is more exit strategy than real peace, she says. “It’s nothing close to peace, because where is the sign of peace?” she asks.

Yet a virtual stop to U.S. airstrikes against Taliban targets since March 1 has led Rahmatullah, a veteran Taliban fighter, to reconsider his earlier commitment to permanent war. “If we think logically, we really need peace,” he says. “Now I am thinking about my kids’ future; we should do something for them.”

Signs of hope for troubled Afghanistan peace talks?

Afghanistan’s need for peace is a realization that has been dawning on one diehard Taliban fighter ever since the United States and Taliban leaders signed a withdrawal deal Feb. 29.

The stocky, bearded Rahmatullah has done his part to keep up the pressure on government forces. Just last Friday, he says, he led an attempt to destroy his local Afghan National Army base, southwest of Kabul.

That attack failed, leaving one jihadist dead and three wounded.

Yet while that battle in Taliban-controlled Wardak Province adds one more datapoint of violence nationwide, it comes amid broader changes – in the thinking of some frontline fighters, like Rahmatullah, as well as among top leadership on both sides – that could finally yield progress toward peace.

For reasons for cautious optimism, analysts point to a new coalescing of political calculations that are focused by renewed U.S. pressure and leavened by the recognition that there may be a limit to leverage gained by protracted violence.

After five months of delay and waffling – marred by the killing of more than 4,300 Afghan soldiers and civilians alone – President Ashraf Ghani announced Tuesday that the government would soon complete a mass release of 5,000 prisoners, and that direct talks would start in a week. The Taliban stated Thursday it would complete its own release of 1,000 prisoners before starting a three-day cease-fire to mark the Muslim Eid holiday, which begins Friday.

In keeping with steps laid out by the U.S.-Taliban deal, such releases pave the way for direct intra-Afghan talks, which were meant to begin in March, lead to a more durable cease-fire, and eventually a peace agreement.

U.S. envoy Zalmay Khalilzad has been in Kabul and Doha, Qatar, as part of a five-nation tour to pressure all players to move quickly. He is reported to have suggested extending the cease-fire.

“Positive changes”

For its part, the U.S. had by mid-June already withdrawn several thousand troops, bringing forces levels down to 8,600, as specified in the deal, with further reductions dependent on lower levels of violence and the Afghan talks.

That has meant a virtual stop to U.S. airstrikes against Taliban targets since March 1 – removing a threat that has made Rahmatullah reconsider his earlier commitment to permanent war.

“If we think logically, we really need peace,” says the veteran Taliban fighter, whose nom de guerre of Mullah Sarbakhod means one who rushes forward wildly, helter-skelter.

Before the U.S.-Taliban deal, “our life was like an animal’s life, we didn’t have a specific address, didn’t have enough food for us and our children,” says Rahmatullah, interviewed in the Wardak provincial capital of Maydan Shahr. Now he “feels good positive changes” and that he can “achieve my goals” because he can move freely and work on his land. He is digging a well in his garden – a task impossible before the easing of U.S. air strikes, he says.

“In these five months, we feel we should work for our community and stop war, because war will never bring prosperity,” says Rahmatullah. “Now I am thinking about my kids’ future; we should do something for them.”

The Taliban fighter’s talk of peace today is far from the hard-line position he articulated in late February, on the eve of the U.S.-Taliban deal. At the time he told The Christian Science Monitor he rejected peace attempts as “useless, because our Prophet, our fathers, our grandfathers ... were always in jihad, so that’s our only way, to continue jihad.”

Even today Rahmatullah says he will keep fighting as long as American forces are in Afghanistan. “I am still against that [U.S.-Taliban] deal, but I will agree and be optimistic when intra-Afghan dialogue becomes successful.”

Reaching that point will be the test of the upcoming three-day cease-fire – the third official cessation of hostilities since June 2018 – and what comes after. It is not clear how many Taliban fighters may have recently shifted their thinking about peace, much less accepted the view that their “victory” over the U.S., NATO, and Afghan security forces may yield, at the negotiating table, only a power-sharing deal with a Kabul government they deem as “un-Islamic.”

U.S. exit strategy?

“The Taliban are building a huge PR out of the cease-fire, by highlighting it as the greatest favor they can give to people, that they won’t kill civilians and target Afghans, again,” says Orzala Nemat, the Kabul-based director of the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit, a think tank.

“What is more important here is to see any serious step toward kicking off the intra-Afghan dialogue,” says Ms. Nemat. “Any single day that we delay this process is making anyone in charge responsible for losses of human beings on either side. The Taliban and the government, they become the owner of any life we lose because of violence.”

And that price is high. President Ghani said this week that 3,560 members of the Afghan security forces and 775 civilians had been killed since signing the U.S.-Taliban deal. Afghans “are increasingly seeing the continuation of carnage instead of a peace dividend,” he said.

First Vice President Amrullah Saleh berated the Taliban’s Eid message, saying on Twitter that the jihadist cease-fire meant “no killing” for three days only, then required Afghans to “surrender to a medieval way of life or face bloodshed.”

What the United States has gained so far is more exit strategy than real peace, Ms. Nemat says. “It’s nothing close to peace, because where is the sign of peace?” she asks. “Releasing killers and suicide bombers is not peace, it’s a deal.”

The Taliban have nevertheless been making adjustments – such as the recent inclusion of four arch-conservative members in their negotiating team in Doha, Qatar – that appear designed to ease concerns among lower level commanders and fighters that their interests may be sold out by leaders they accuse of preferring luxury over the trenches.

At the same time, the Taliban are “giving a longer leash to the most aggressive Taliban commanders to keep fighting,” says a Western official based in Kabul, who asked not to be further identified. One young fighter in eastern Afghanistan told the Washington Post earlier this month, for example, that the Taliban would “only accept 100 percent of power” in the country. His commander claimed the goal of talks was “complete destruction” of the government.

“Victory for all Afghans”

The Taliban are used to simultaneously talking and fighting, but this time are carefully calibrating the scale of violence by mounting constant attacks while taking little new territory.

The result is they are keeping up pressure, “but not putting so much pressure that things might break,” says the official. “Right now, if they wanted to, they could overrun several districts, but they have held back.”

Those conducting such attacks include a Taliban deputy district chief, Suleiman Roostami, who a week ago led strikes against a string of small bases in Wardak Province, killing nine Afghan police and detaining seven others.

He told the Monitor last February how tired he was of the war, and how constant fighting often had little result.

“There are not changes in our life ... every day fighting, every day conflict, the only change is before we targeted U.S. forces, but now we target only Afghans,” the young-faced militant and father of four says now. He notes that Taliban fighters have become “very strong” during the past five months of training without the fear of U.S. airstrikes.

An American departure would be a “big victory” for the Taliban and worthy of celebration, he says. But he also hopes for national reconciliation.

“Personally, I want peace because I am really tired of this bad condition,” says Mr. Roostami. “If peace comes that will be a big victory for all Afghans, not only the Taliban, because all Afghans need peace, and we will enjoy our life.”

Reporting for this story was contributed by Hidayatullah Noorzai in Maydan Shahr, Afghanistan.

How Portland protests became a campaign stage for Trump

In politics, the reasoning behind decisions is rarely straightforward. Portland has been ground zero for a battle of perspectives, from the need for “law and order” to signs of election-year calculations at work.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The presence of federal law enforcement officials in Portland, Oregon, is centered on protecting the federal courthouse there. But amid a pandemic and an economy in deep distress, President Donald Trump’s reelection prospects have been thrown into serious doubt – and some observers suggest that the federal intervention is in part a bid to deflect attention from the larger, national crises.

Amid nightly clashes between Portland protesters and law enforcement, the president is presenting himself as a “law and order president” – an echo of Richard Nixon’s successful presidential campaign in 1968. But Mr. Nixon wasn’t the incumbent. Mr. Trump is, and fairly or not, he risks blame for some of the upheaval.

Democrats still run the risk of a backlash, to the extent that the protests are associated with destruction and violence. For now, however, observers say the scale of the mayhem isn’t big enough to help Mr. Trump much, especially at a time when the coronavirus remains the overwhelming issue for the country.

“This is not 1968, where the violence and the demonstrations were the story, not a sideshow,” says William Galston, a top domestic policy aide in the Clinton White House. “They’re not the story this year.”

How Portland protests became a campaign stage for Trump

Nightly images of mayhem out of Portland, Oregon, gave way to hope Wednesday after federal and state officials announced a conditional withdrawal of federal forces from the embattled northwestern city.

But by Thursday, the promise of a quick end to the stalemate seemed to unravel, following another night of clashes between protesters and federal officers. And with each passing day, as the Nov. 3 elections approach, the politics grow more fraught.

The federal law enforcement effort in Portland is centered on protecting the federal courthouse there. But amid a pandemic and an economy in deep distress, President Donald Trump’s reelection prospects have been thrown into serious doubt – and some observers have suggested that the federal intervention is also, at least in part, a bid to deflect attention from the larger, national crises.

President Trump is presenting himself as a “law and order president,” an echo of Richard Nixon’s successful presidential campaign in 1968. But there’s a big difference: Mr. Nixon wasn’t the incumbent. Mr. Trump is – and fairly or not, he risks blame for some of the upheaval.

Democrats and their presidential candidate, Joe Biden, still run the risk of a backlash, to the extent that those on the side of the protesters are associated with destruction and violence. Some Black activists have recently suggested that the original focus of the protests – demands for police reform and racial justice after the May 25 killing of George Floyd in police custody in Minneapolis – is being obscured.

For now, however, observers say the scale of the upheaval in Portland isn’t big enough to hurt Democrats or help Mr. Trump much, at a time when the coronavirus remains the overwhelming issue for the country.

“This is not 1968, where the violence and the demonstrations were the story, not a sideshow,” says William Galston, a top domestic policy aide in the Clinton White House. “They’re not the story this year.”

A political distraction?

Even when the focus is on Portland, the issue favors Democrats. So far, suburban voters, who could swing the presidential race, are not giving Mr. Trump high marks for the Portland deployment.

“I don’t necessarily see [the Portland clashes] helping him,” says Karlyn Bowman, an expert on polling at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington.

A new Morning Consult/Politico survey found that some 47% of suburbanites said they disapproved of the staging of Department of Homeland Security officers in Portland, versus 42% who said they approved, the poll found. In addition, 49% of suburbanites said the federal presence in Portland had done more to increase unrest rather than quell it.

Analysts note that American suburbs have become increasingly diverse, making it more difficult for politicians seeking suburban votes to use race as a wedge issue.

“[Mr. Trump’s] trying to distract from the central failure on coronavirus,” says Democratic strategist Jared Leopold. “It’s not a persuasive argument for the suburbs.”

And polls show voters trust Mr. Biden to do a better job on race relations than Mr. Trump by a wide margin – 21 points, according to a recent Fox News poll.

Still, the violence in Portland is not without risks for Democrats and Mr. Biden. The former vice president has already rejected the left’s rallying cry of “defund the police.” And in remarks in early June, he distinguished between “legitimate peaceful protest” and “opportunistic violent destruction.”

But he probably needs to speak up again, says Mr. Galston. “Someone who’s been in politics as long as he has knows that saying something once is not enough.”

As of today, polls show Mr. Trump in serious danger of losing the election, and if he’s going to use Portland to his advantage, he needs to get the messaging just right, says Scott Jennings, a former political adviser to President George W. Bush.

“The public wants [Mr. Trump] to respect the need for some kind of police reform, but I don’t think they approve of anarchists hijacking the situation,” Mr. Jennings says.

The public sees the president responding to the lawlessness but isn’t aware of his efforts on police reform, he adds.

Trump defenders point to two such efforts: On June 16, Mr. Trump issued an executive order aimed at incentivizing police reforms. He also backed reform legislation in the Senate – led by the only Black Republican in that chamber, Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina – which the Democrats blocked.

The Democrats, who control the House, passed their own bill, which won’t go anywhere in the Republican-controlled Senate. Thus the matter is deadlocked – the typical fate of most election-year legislation.

But on the ground in Portland, there’s no waiting, as the nightly rhythm of protests, police action, and violence has continued.

Especially with the pandemic, in which many Americans’ lives and livelihoods are at stake across the country, protecting public safety has to be paramount, say Trump defenders. To small business owners whose establishments have been threatened or damaged, protection by law enforcement is key.

“Politics should not have anything to do with saving lives,” says Bruce LeVell, a Black business owner in Atlanta and executive director of the National Diversity Coalition for Trump. “No sitting mayor, Republican or Democrat, should ever deny any law enforcement assistance to people in need.”

Differing interpretations

But the multitiered law enforcement dynamic in Portland is especially fraught. After federal, state, and local officials all announced that federal agents would begin leaving Portland, it soon became clear they had differing interpretations of when the federal forces’ departure would take place.

Acting Homeland Security Secretary Chad Wolf said that the federal law enforcement presence would remain “until we are assured that the courthouse and other federal facilities will no longer be attacked nightly.”

Oregon Gov. Kate Brown, a Democrat, said the federal withdrawal would begin Thursday, and that state police would take over protection of the federal courthouse in Portland.

Portland Mayor Tom Wheeler, a Democrat, told reporters on a conference call that he welcomed the agreement for “the imminent withdrawal” of federal agents, but vowed to “continue to fight this occupation until these forces are gone from every city.”

On that call, organized by the U.S. Conference of Mayors, other mayors reinforced Mayor Wheeler’s message, that the deployments of federal officers were not just unwelcome but also harmful, unconstitutional, and a political ploy.

Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan said the arrival of federal agents in Portland as well as Seattle had produced spillover unrest and an escalation of violence in her city. She confirmed that the agents have since withdrawn from Seattle after pressure from local and state authorities. And she raised a concern echoed by some Democrats: that the federal deployments seem “very much like … a dry run for martial law.”

Mr. Trump himself raised the specter of extraordinary measures to address the challenge of holding an election amid a pandemic. “Delay the Election until people can properly, securely and safely vote???” he suggested in a tweet Thursday.

Republican lawmakers, however, were quick to dismiss the prospect. “Never in the history of federal elections have we ever not held an election, and we should go forward with our election,” House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy told reporters.

The politics that seem to lurk at every turn in this season of unrest are hard to avoid. On Thursday, the Department of Justice announced that another federal law enforcement initiative in American cities, Operation Legend, would expand to include Cleveland, Detroit, and Milwaukee. Operation Legend is billed as an effort to help state and local law enforcement fight violent crime, and is different from the deployment in Portland, which aims to protect federal property.

All three cities are located in battleground states – Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

Staff writer Ann Scott Tyson contributed to this report from Seattle.

More than a month: The push to change how Black history is taught

What is the best way to teach Black history? With new attention on race in the U.S., some advocates wonder if the time is right to give the subject more than one month out of the school year.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Stephanie Hanes Correspondent

Rann Miller, an educator and writer, says that for too long, it has been up to individual teachers to counteract gaps about Black history taught in schools. Many teachers are unaware of their own blind spots, he adds. Nearly 80% of public school teachers are white, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, even though more than half of the country’s students are of other races and ethnicities.

“Educators need to educate themselves,” Mr. Miller says. “Quite frankly, you have a lot of white people who are unaware of the history of our nation. You may also have a lot of Black people who are unaware of the history of our nation.”

A growing number of voices are demanding a new approach to teaching Black history in the nation’s K-12 institutions, where the subject is often only focused on during Black History Month in February. The New York Legislature, for instance, is considering a mandatory full-year Black history curriculum; over the past months a petition supporting that law grew from 10,000 signatures to more than 110,000.

“We don’t want cultural awareness once a year for 28 days,” says Anthony Beckford, a community organizer in New York City who spearheaded the petition. “It should be a year-in, year-out endeavor.”

More than a month: The push to change how Black history is taught

Rasheeda Harris sees a difference in her daughter in February. That’s when 10-year-old Afiya seems more excited about school, more willing to talk about what she learned. It’s when she gushes about the people her teachers have introduced in history class: Rosa Parks. Ella Baker. Michelle Obama.

“She blossoms during that time,” Ms. Harris says. “We see the energy when she sees herself reflected.”

So Ms. Harris picks up the phone and calls her school administrators. This, she tells them, is what students need. And she asks them – as she has again and again, throughout her work as a parent activist with the New York-based Alliance for Quality Education – to teach Black history throughout the year, not just during Black History Month.

“When you deny children the opportunity to see themselves reflected in the curriculum and in the textbooks and in the worksheets, you deny them the ability to fully engage in the curriculum,” says Ms. Harris. “It’s important that our schools start to hone in on that fact.”

The Alliance for Quality Education, a grassroots group that works against what it sees as systemic racism in New York public schools, is just one of a growing number of voices demanding a new approach to teaching Black history in the nation’s K-12 educational institutions. The New York Legislature, for instance, is considering a mandatory full-year Black history curriculum; over the past months a petition supporting that law grew from 10,000 signatures to more than 110,000.

“We don’t want cultural awareness once a year for 28 days,” says Anthony Beckford, a community organizer in New York City who spearheaded the petition. “It should be a year-in, year-out endeavor.”

Educators from across the country have joined the Black Lives Matter at School organization calling for an increase in Black history and ethnic studies instruction. And organizations such as New America have released reports showing the importance of “culturally responsive” teaching for students’ educational outcomes.

“Black history shouldn’t be – and it doesn’t need to be – taught in a vacuum,” says Steve Becton, chief officer for equity and inclusion at Facing History and Ourselves, an organization that offers classroom and professional resources for educators with the goal of using history to help students’ ethical development. “It can be taught around the larger questions about democracy and what it means to be part of this country.”

Seeking information

Since May, when the killing of George Floyd, a Black man, by a white police officer sparked nationwide protests, traffic to Facing History’s website has increased 90%, with more than 40,000 views of its page dedicated to resources for teaching about Mr. Floyd’s death and police violence. The group’s “Understanding #TakeAKnee” page, with classroom resources exploring the history of athletes and activism, as well as critical patriotism, has received more than 10,000 views since May 28. Last week the group held an online summit for teaching equity and justice. It sold out the first week it was advertised.

The increase in traffic reflects how more people are talking about questions of privilege, and about historic structural racism, Mr. Becton says. “To understand what’s happening in this moment in time, one must really understand the central and profound questions of how we got here,” he says.

Rann Miller, an educator and writer who runs teacher professional development workshops on cultural competency, says this concept is at the foundation of why there needs to be a new, widespread focus on Black history. But for efforts to be effective, he says, there needs to be districtwide support. For too long, he adds, it has been up to individual teachers to counteract gaps in curriculum. But many teachers are unaware of their own blind spots, says Mr. Miller, a former high school history teacher who oversees an after school program in New Jersey. Nearly 80% of public school teachers are white, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, even though more than half of the country’s students are of other races and ethnicities.

“Educators need to educate themselves,” Mr. Miller says. “Quite frankly, you have a lot of white people who are unaware of the history of our nation. You may also have a lot of Black people who are unaware of the history of our nation.”

And traditional textbooks, whose content is ultimately determined by state officials and curriculum standards, may not be of much help. Just the other day, Mr. Miller says, he picked up a history textbook at a school in New Jersey to see what it said about Juneteenth, the holiday celebrating the end of slavery in the U.S. The day had become the focus of national conversation after President Donald Trump scheduled a campaign rally to be held on June 19 in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the site of one of the worst massacres of Black people in U.S. history.

But the textbook did not mention it at all, he says.

“Black scholars and practitioners have been talking about this for years,” he says. “There’s been an acknowledgment that history isn’t being taught correctly, that textbooks are whitewashing U.S. history. You are starting now to hear those voices being amplified.”

Indeed, recent analyses of textbooks nationwide show a significant disparity in the way they approach race and Black history. The New York Times published an investigation earlier this year that found the same social studies textbook, with the same title from the same publisher, treated issues of race differently in its Texas version than it did in its California edition. In California, for instance, a section about 1950s suburbanization included information on housing discrimination against Black people; the Texas book did not mention racism, but explained that residents fled cities to escape crime.

“So many racial disparities”

The trickiness of history as a subject features in current debates about the past. The New York Times’ 1619 Project (now also a school curriculum) has won praise for its deep exploration of slavery in the U.S., but also criticism for alleged inaccuracies and what some conservatives call a “revisionist” take on history. In many ways, says Lisa Covington, an educator in Iowa City who is on the national committee for Black Lives Matter at School, the push for revamped Black history instruction is part of a wider effort to address broad and long-standing discrimination against Black students.

“There are so many racial disparities in school,” she says.

Studies show that Black students are more likely to attend a school with less funding and fewer resources, and also more likely to encounter harsher discipline than white students for the same behavior. In 2018, the influential book “Teaching for Black Lives” argued that “Black students’ minds and bodies are under attack,” and pointed to curricular materials across the country that erase Black experiences, such as a Texas history textbook that described the Atlantic slave trade as bringing “workers from Africa” to help on plantations.

Ms. Covington says that while she would like to see Black history taught outside the silo of Black History Month, she also believes there should be professional guidance for schools to include the contributions of Black people in other subject areas.

“People are saying, ‘Yes, let’s teach Black history,’” she says. “But they have no plan how to be culturally proficient with any other curricular subjects.”

These are questions Mr. Becton says he is happy to see discussed.

“People in education are having more conversations about questions of equity,” he says. “And if you want to explore equity in a meaningful way, you have to have an understanding of historical inequity.”

With Perseverance, NASA launches new stage in Mars exploration

One of humanity’s most burning scientific questions is whether we are alone in the universe. Answering that question, say scientists, is an incremental process.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

At 10 minutes to 8 this morning, NASA’s newest Mars rover lifted off at Cape Canaveral atop an Atlas V-541 rocket.

The rover, named Perseverance, is more than just an upgraded version of Curiosity and the others that have roamed the Martian surface. Packed with upgraded instruments including a helicopter drone, an advanced camera, a microphone, and, most significantly, a tool that can collect and bag samples, Perseverance is designed to bring NASA’s search for life on the red planet into a new era.

Unlike past missions, which were aimed at determining if the Martian environment was ever capable of supporting life, this mission aims to seek out signatures of past life itself. The Mars Sample Return, a collaboration between NASA and the European Space Agency, is designed to seal rock cores in containers to be collected by future missions and flown back to Earth, where generations of future scientists can analyze them.

“I see Perseverance as being transformative,” said Jennifer Trosper, deputy project manager for the mission at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, during a press conference Monday. “This is transforming us to bringing samples back and eventually getting humans there.”

With Perseverance, NASA launches new stage in Mars exploration

Others have gone before. Sojourner, Spirit, Opportunity, and Curiosity have all roved the surface, beaming home tantalizing images. But now, a new envoy is en route to Mars – one that could fundamentally change how we see the red planet and our place in the universe.

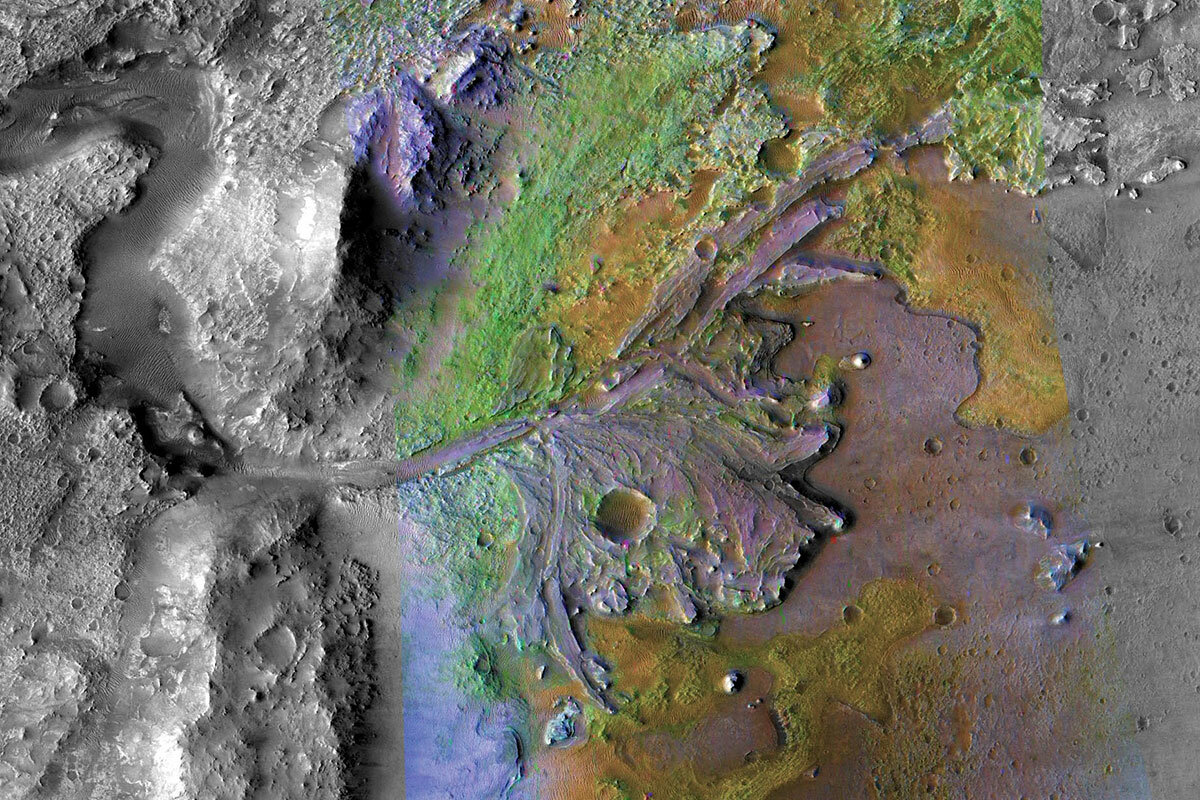

NASA’s latest Mars rover, Perseverance, launched from Cape Canaveral at 7:50 this morning atop an Atlas V-541 rocket. If all goes well, it is set to touch down in Jezero, a 28-mile-wide crater north of Mars’ equator, at about 3 p.m. Eastern time on February 18, 2021.

This isn’t just another rover going to another part of Mars. NASA’s Mars 2020 mission signals a shift in the agency’s approach to studying our planetary neighbor. No longer are the researchers asking if Mars was ever capable of supporting life. Perseverance is designed to seek out signatures of past life itself.

“We know now that these environments were habitable, now let’s look for signs of life,” says Briony Horgan, an associate professor of planetary science at Purdue University and a co-investigator on Mars 2020. “We still have no idea how common life – at even the microbial level – is. Was Earth a fluke? Are we a fluke? Or is it really common in the universe? And the best way to look at that is to look in our own backyard.”

The Mars 2020 mission is also designed to sense the planet in new ways. For instance, Perseverance has a microphone to record the sound of Martian winds whipping across the landscape. The rover is also accompanied by a 4-pound helicopter, dubbed Ingenuity, built to make history’s first powered flight on another world.

Perseverance is also laying the groundwork for more sophisticated missions. It’s designed to collect and bag rocks to be eventually returned to Earth, and it carries a tool that will attempt to produce oxygen from the planet’s atmospheric carbon dioxide.

“I see Perseverance as being transformative,” said Jennifer Trosper, deputy project manager for Perseverance at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, during a press conference Monday. “This is transforming us to bringing samples back and eventually getting humans there.”

“A totally new kind of mission”

In the early days of NASA’s exploration of Mars, many researchers hoped to find microbes right off the bat. NASA’s Viking 1 and Viking 2 landers, which in 1976 became the first U.S. spacecraft to land on the surface of Mars, carried tools to search for signs of life in the soil.

One experiment did indeed turn up a possible positive detection of what could have been the metabolism of current life, stirring up excitement and controversy. But scientists couldn’t rule out explanations that were unrelated to biology, and that ambiguity prompted researchers to step back.

“I look at it as a cautionary tale of getting a little too ambitious too early,” says Erik Conway, a historian at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “Before you go looking for complicated things like living processes, you need to understand the environment.”

What followed was largely a search for signs of liquid water from Mars’ past, which is thought to be crucial for life as we know it. And, sure enough, they found it. In fact, Mars was once quite wet.

That’s actually why NASA selected Jezero Crater as the landing site. Images and data collected from spacecraft orbiting Mars reveal clear signs that liquid water once flowed there, and geologists say the only explanation for the shape of the crater is that, some 3.5 billion years ago, it was actually a lake.

“It had rain coming down, and rivers flowing, and lakes, and maybe oceans.” Dr. Horgan says. “It’s going to be a totally new kind of mission.”

But just going to a compelling location isn’t enough to detect life.

Previous rovers – particularly Curiosity – detected intriguing clues, but they revealed nothing that couldn’t be explained non-biologically. For example, Curiosity detected organic matter on Mars, but the rover lacks the tools to determine if those building blocks for life arose from ancient Martian biology or from abiotic Martian chemistry.

Compared with Curiosity, Perseverance boasts several upgraded instruments, including an advanced camera that could help researchers spot a stromatolite, a kind of rock formed only by microbes. But what’s most likely to answer the big question of whether Martians ever existed is the mission’s sample-return component.

To do that, the rover will drill into rocks, extract small cores, and seal them away in containers that it will leave on the surface for a future mission to collect and fly back to Earth for analysis. That endeavor, called Mars Sample Return, is a collaboration between NASA and the European Space Agency.

Being able to bring rocks back to Earthly laboratories could allow researchers to unlock many more secrets of Mars.

"You’re never going to have a spacecraft that can carry everything you want,” says Smithsonian Institution geologist John Grant, who served on the selection committee for Perseverance’s landing site. “If you bring samples back,” he says, “50 years later, when we’ve got techniques that are far more refined ... we can apply those.”

Pandemic pen pals: How Colombian libraries lift spirits

Locked down at home, we all feel isolated. Yet next door, or across town, most of us are wrestling with similar emotions. Libraries in the book-loving city of Medellín are helping readers connect – creatively.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Colombia has long been a country of books. Before the pandemic, it was common to see tourists searching out its storied libraries – riding cable cars, for instance, to the “library parks” in Medellín’s mountainside barrios. The country is home to world-famous book and poetry festivals, and the birthplace of Gabriel García Márquez, one of Latin America’s most famous novelists.

But the love of libraries is more than a love of reading. During 50 years of conflict, they often provided literal and figurative refuge. Today, libraries are even part of the peace process. And now, amid COVID-19, the libraries of Medellín are again giving readers a way to connect and escape.

“Love in the Time of Coronavirus,” they call it – a play on Mr. Márquez’s best-selling novel, “Love in the Time of Cholera.” Participants email letters written from the perspective of made-up characters, literary figures, or using pen names, which are passed along anonymously to another reader.

“I feel like the pandemic has generated so many feelings that I’ve never experienced before,” says letter-writer Alejandra Correa. “This opportunity to communicate so deeply with people you don’t know and to transmit words that might help others feel less alone; it’s a gift.”

Pandemic pen pals: How Colombian libraries lift spirits

When Alejandra Correa wrote her first letter under the pen name “Ale” in mid-July, she felt a huge sense of relief.

“I hope this [letter] allows you to feel all of the emotions that are hitting you: the rage, the anguish, but also the hope,” she typed, polishing off a one-page missive on floral, navy-blue stationary in less than 10 minutes. She doesn’t consider herself a writer, but says her words and pent-up emotions spilled onto the page.

Her letter wasn’t addressed to a dear friend or old flame. In fact, Ms. Correa, a human resources manager in Medellín, Colombia, has no idea who received her note. Just like she will never know who sent her the achingly romantic account about surviving COVID-19 in order to reunite with a soulmate.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

These letters are some of the more than 300 sent in an anonymous letter-writing campaign, organized by libraries, that emerged following Medellín’s initial COVID-19 lockdown last spring. Community members email library staff letters written from the perspective of made-up characters, literary figures, or personal reflections shielded by pen names, and the letter is passed along anonymously to other participants. For each letter you pen, you receive one in your inbox.

“I feel like the pandemic has generated so many feelings that I’ve never experienced before,” Ms. Correa says of why she joined the initiative – and plans to keep sending letters as long as the program is up and running. “This opportunity to communicate so deeply with people you don’t know and to transmit words that might help others feel less alone; it’s a gift.”

Libraries in Colombia have a rich history of coming to the service of communities in crisis, and this project, created by a network of libraries known as Comfenalco, is just the latest iteration. Neighborhood-run libraries popped up in impoverished and overlooked areas during the nation’s 50-year armed conflict, serving as a unifying force. Libraries provided physical shelter from violence in the heyday of Pablo Escobar’s Medellín Cartel trafficking empire, and most recently have offered a mental escape from the pandemic-induced confinement.

“Reading and writing can unite us and can generate community,” says Bibiana Álvarez, who promotes reading and culture at Comfenalco libraries in and around Medellín. She was part of the team that came up with the idea for the letter-writing program, known as “Love in the Time of Coronavirus.” It’s a play on the title of the bestselling 1985 novel, “Love in the Time of Cholera,” by Colombia’s arguably most internationally-known author, Gabriel García Márquez. In the book, two young strangers begin exchanging letters, leading to a distanced love affair and years of correspondence.

“The idea of the letters – that really stuck with us,” she says. “This is a moment when you can’t touch or see other people ... With the arrival of a letter, you can see how you are valued.”

Beloved tradition

Medellín has long been a city of books and libraries: from receiving one of UNESCO’s three public library pilots in the 1950s, meant to serve as a model for cultural promotion in the developing world; to Catholic priests promoting grassroots community libraries following the famous 1968 Medellín conference of bishops; to hosting world-famous book and poetry festivals. For the past decade, Medellín has had public policies designed to promote reading, writing, and oral histories, with libraries playing a central role.

But librarians in Medellín have a favorite point of reference about the power of their work. In the 1980s and ’90s, drug-trafficking-related violence swept much of Colombia. Medellín was considered one of the most dangerous cities in the world. By 2002, a federal government operation meant to instill peace in one of the city’s poor, mountainside neighborhoods instead led to the deaths and arrests of scores of civilians, shuttering everything from corner stores to playgrounds for nearly two weeks. Everything except for the library, that is.

“This library was the oasis of protection for the community,” recalls Adriana Betancur, who has worked in Colombia’s public library system for more than two decades and has written on the role and history of libraries there. Although stepping foot outside put their lives at risk, “the kids kept coming to the library,” she says, and family programming continued. “It’s the protective space of the community, a space of liberation from the problems of the neighborhood. Here, libraries have played a really important role in constructing peace, but even more than that, creating community.”

There are more than 4,000 libraries nationwide, estimates Ms. Betancur, and pre-coronavirus it was common to see tourists, guidebooks in hand, seeking out these sacred spaces: from the Luis Ángel Arango Library in the historic center of Bogotá, to riding cable cars or outdoor escalators to “library parks” in Medellín’s mountainside barrios.

More recently, libraries became part of the country’s peace process, with the Ministry of Culture launching Mobile Libraries for Peace. The program works with demobilized guerrilla fighters to help them reintegrate into civilian life through a focus on literacy and digital skills.

“In some parts of the world people think of a library’s success in terms of literacy,” says Clara Chu, director of the Mortenson Center for International Library Programs at the University of Illinois. “Without literacy it’s hard to advance in terms of development, but once people understand that all these things work hand in hand, they realize it isn’t just about” reading, she says. Libraries have a key “social role,” no matter where they’re located in the world.

“We’re not alone”

Ms. Álvarez, from the letter-writing project, says pivoting to keep up the library’s important community role during a time when human interaction – and visiting enclosed public spaces – is so discouraged has been a unique challenge. Books themselves go into quarantine upon return, barred from checkout until they’ve been properly cleaned. Her team worked quickly to shift most of their programming online, from writing groups to children’s story hours. They’ve hosted a series of webinars on topics from illustrating stories to getting to know Medellín.

But “Love in the Time of Coronavirus” amazed even the most biblio-faithful among them.

“We were surprised,” says Ms. Álvarez, who recalls that one or two cards trickled in when they first launched the project, and then suddenly they’d receive 25 in one day. The library is archiving all of the letters, but hasn’t made them public yet.

Ms. Correa says “Love in the Time of Coronavirus” has allowed her to share emotions she can’t express with friends and family. “You don’t have to drown in these feelings or shoulder them on your own. There are so many sounds inside that we can’t express right now and [this program] is a really appropriate way to do it. Writing and reading is a really powerful tool,” she says.

In her second letter, written on July 25, Ms. Correa gets personal. She talks about missing her mother’s birthday and how her family’s tendency to express their love with actions, not words, has made being apart even harder.

“The written word allows us to understand other humans, and whether we’re reading a novel, a story, or a letter, it helps us understand we’re not alone,” Ms. Alvarez says.

Editor’s note: As a public service, all our coronavirus coverage is free. No paywall.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why old-style news is new again

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

From plagues to earthquakes, disasters often push people in wholly new directions. Will the current pandemic be the same? An inkling of a shift comes from a new study. It found more Americans have turned to mainstream news sites since the COVID-19 crisis began. They have shied away from what researchers call “iffy” sources on social media.

This “flight to quality,” as the study puts it, is more than a desire for truth about ways to avoid personal harm. People are also worried about the virus’s impact on the world. Others have had their beliefs about nature, God, or humanity challenged. Trained journalists in traditional media have provided access to practical advice as well as broad meaning.

In all aspects of life, truth became liberating. “It is only light and evidence that can work a change in men’s opinions; and that light can in no manner proceed from corporal sufferings, or any other outward penalties,” wrote 17th-century philosopher John Locke.

The pandemic has turned much of modern life upside down. But it has also unleashed a search for sustaining truths that can outlast the crisis.

Why old-style news is new again

From plagues to earthquakes, disasters often push people in wholly new directions. Will the current pandemic be the same? An inkling of a shift comes from a new study at the University of Michigan. It found more Americans have turned to mainstream news sites since the COVID-19 crisis began. They have shied away from what researchers call “iffy” sources on social media.

This “flight to quality,” as the study puts it, is more than a desire for truth about ways to avoid personal harm. People are also worried about the virus’s impact on the world. Others have had their beliefs about nature, God, or humanity challenged. Trained journalists in traditional media have provided access to practical advice as well as broad meaning.

The study’s conclusion: “It appears people turn to tried and true sources of information” to navigate through a life-and-death situation and all its uncertainties.” But, adds Paul Resnick, one of the researchers, “It will be interesting to see whether this ‘flight to quality’ is short-lived.”

A crisis like a pandemic can quickly restore people’s trust in their ability to know the truth – and to seek out trustworthy news. Traffic to traditional media outlets has surged since the pandemic began. And social media platforms like Facebook are culling disinformation about COVID-19 from their sites.

This truth-seeking is a frequent reaction after a disaster. When three earthquakes and a tsunami killed tens of thousands in Lisbon, Portugal, in 1755, the enormity of the devastation triggered a revolution among Europeans about the role of God in such events. People began to develop critical thinking skills and the tools for fact-checking. This gave them the information and the mental acuity to put disasters in context.

In all aspects of life, truth can be liberating. “It is only light and evidence that can work a change in men’s opinions; and that light can in no manner proceed from corporal sufferings, or any other outward penalties,” wrote 17th-century philosopher John Locke.

The pandemic has turned much of modern life upside down. But it has also unleashed a search for sustaining truths that can outlast the crisis. Old-fashioned journalism can’t uncover all the answers. Yet with more people seeking fact over fiction, the truth will win in many ways.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

‘When you pray, move your feet’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Trudy C. Palmer

In recognition of the lifework of John Lewis, including his commitment to loving “people in particular,” not just “people in general,” here’s an article from our archives that points to the spiritual basis for racial equality.

‘When you pray, move your feet’

“Walking With the Wind,” John Lewis’s 1999 memoir of the civil rights movement, details the efforts of pacifists, in the late 1950s and the 1960s, to integrate lunch counters, buses, and public restrooms, and to register Black people to vote. Every time they tried to claim the rights of full citizenship, these mostly young, freshly-scrubbed people put life and limb on the line, as did the white people who later joined their ranks.

Now, segregation no longer delineates with bold brushstrokes between Black and white. It draws thin lines with a pencil, subtly shading experience according to tradition, education, income, and opportunity. The effect? De facto segregation. Families live in areas where their neighbors are, for the most part, of their same race. Children attend schools where their peers are, for the most part, of their same race. People go to jobs where those with whom they work (though not necessarily those for whom they work) are, for the most part, of their same race. This is a far cry from the “Beloved Community” civil rights activists sought to establish.

Did their efforts fail? No. There can be little doubt that the struggles they waged and won have improved the lives of Black and white people alike. But victories in battle don’t necessarily signal the war’s end. As Mr. Lewis succinctly puts it, “Combating segregation is one thing. Dealing with racism is another.” Attitudes are harder to target than behaviors. That’s why racism is harder to outlaw than segregation. Ultimately, though, unless racist attitudes are annihilated, no amount of effort will permanently establish equal rights.

How, then, do we eradicate racism? Surely a first step in this effort is prayer. One launching point for that prayer is the First Commandment. Following this commandment would of necessity destroy the roots of racism, for honoring only the one God, who is all good, precludes believing that ignorance or hatred is more powerful than God or that some aspect of His creation might fail to express Him. Instead of justifying either superiority or inferiority, acknowledging the perfection of God, the divine Parent, requires us to admit that God’s children, made in His likeness, are perfect as well.

In her book on healing, Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, affirms the link between the First Commandment and brotherly love. She writes, “One infinite God, good, unifies men and nations; constitutes the brotherhood of man; ends wars; fulfils the Scripture, ‘Love thy neighbor as thyself’ ...” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 340). Reasoning from this basis, we arrive not only at each individual’s unbroken relation to God but also at the interconnectedness of all His children.

But how do we get from this spiritual understanding to the “Beloved Community,” to the “kingdom of God on earth”? The answer once again: prayer. Prayer as Mr. Lewis defines it with this African proverb: “‘When you pray, move your feet.’”

And Mr. Lewis did move his feet. Whether marching from Selma to Montgomery, plying the back roads of the Deep South in a voter registration drive, or striding the mile and a half to his own victory celebration following his election to the U.S. Congress, Mr. Lewis walked the walk. Shoulder to shoulder with people of various colors, classes, and creeds, he counts no one his enemy, not even his attackers. Far beyond advocating tolerance of others, even beyond urging respect, Mr. Lewis practiced “a love that recognizes the spark of the divine in each of us.”

Not surprisingly, Mr. Lewis couldn’t live this kind of love in isolation. Nor could he live it surrounded only by those of his own race or class. When it comes to eradicating racism, the prayer that makes you move your feet requires you to forsake the comfort of familiarity for life among a variety of people.

Toward the end of his memoir, Mr. Lewis observes: “Yes, all politicians love people in general. ... But many of them are very uncomfortable with people in particular ....” With a touch of humor, he reminds us here that “love” is an action, a verb. And he reminds me that if I am to help create the “Beloved Community,” I must do more than love God’s perfect child in general. I must also love people in particular – never forgetting their spiritual nature, ever appreciating their humanity.

Adapted from an article published in the February 2000 issue of The Christian Science Journal.

A message of love

Taking a dip

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’ll look at how Muslims have transformed their annual pilgrimage to Mecca during the pandemic, and how participants are finding faith and community in a way that transcends physical space.

Next week, we will be launching Season 2 of our hit podcast. “Perception Gaps: Locked up” will take you into the criminal justice system, exploring misperceptions about mass incarceration. You can listen to the introduction episode and sign up for the newsletter on the Season 2 landing page.