- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- In Kenosha, Biden tries to thread the needle on protests and violence

- Biden or Trump? Rival policies on China keep world guessing

- Why US wants Saudis to follow UAE’s path to nuclear energy

- To the Russian manor born: Public gets a rare chance to walk historic halls

- Movies bring us together. But should we get used to viewing them apart?

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Backpacking in the Big Apple

This summer, Jessica McKenzie and her boyfriend set off on a backpacking trip with a different kind of scenery: New York City. Skyscrapers supplanted mountains, a gushing hotel shower replaced waterfalls, and a polluted federal Superfund site revealed some urban wildlife to the pair.

Facing travel restrictions due to the pandemic, adventures this year have been put on hold for many people. But some have found innovative ways to adapt.

“I wondered,” Ms. McKenzie, a journalist, writes for Backpacker.com, “what would happen if I took to heart the advice to recreate right in my backyard?”

The trek she designed traversed all five boroughs of New York entirely on foot, save for the ferry to Staten Island. During the couple’s nearly 40-mile, two-day hike, they met another backpacker stymied by the pandemic: a man who had been set to walk the famous Camino de Santiago in Spain. In place of his original plan, he was walking the streets of Queens with a backpack full of books. (I highly recommend reading Ms. McKenzie’s own account of her adventure on Backpacker.com.)

Not everyone’s city adventures have been so grand. Many city dwellers have been exploring new parks or discovering other nooks and crannies in their neighborhoods that they never knew existed. In general, we’re just slowing down and noticing little things more. As wanderlust has struck this year, it’s also drawn out a creativity in many backyard adventurers.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

In Kenosha, Biden tries to thread the needle on protests and violence

Joe Biden’s supporters express a range of concerns – from longtime Democrats frustrated by recurring violence to younger progressives more focused on root causes. Satisfying them all may not be easy.

-

Christa Case Bryant Staff writer

Former Vice President Joe Biden took a strong stance this week against protest-related violence in cities from Portland, Oregon, to Kenosha, Wisconsin – where he paid a visit Thursday, meeting with Jacob Blake’s family and other members of the community, two days after President Donald Trump came to survey the damage and express his support for law enforcement.

It remains to be seen whether Mr. Biden’s visit will reassure moderate voters who have been jarred by months of sporadic unrest, and who could ultimately tip the election in critical battleground states like Wisconsin.

Polls show Mr. Biden holds a seven-point lead on average nationwide. But the Biden campaign is clearly concerned about the potential for this issue to fracture the Democrat’s coalition of suburban moderates, minorities, and urban progressives. As President Trump casts himself as the “law and order” candidate, Mr. Biden is trying to thread a political needle by denouncing looting and violence without undermining his bona fides as a champion for racial justice and systemic change.

“Biden’s been forceful about rejecting violence in all forms – and that’s good, and it’s different from Trump,” says Rita Kirk, a professor and political communications expert at Southern Methodist University. “What he hasn’t done is distinguish his plan of action.”

In Kenosha, Biden tries to thread the needle on protests and violence

Former Vice President Joe Biden took a strong stance this week against protest-related violence in cities from Portland, Oregon, to Kenosha, Wisconsin – where he paid a visit Thursday, two days after President Donald Trump came to survey the damage and express his support for law enforcement.

Mr. Biden met with the family of Jacob Blake, who was shot in the back by a white police officer on August 23, sparking a spate of arson and destruction. He also spoke to members of the community, on issues ranging from racism to mental health and drug addiction.

It remains to be seen whether his visit will reassure moderate white voters who have been jarred by months of sporadic unrest, and who could ultimately tip the election in critical battleground states like Wisconsin.

Polls show Mr. Biden holds a seven-point lead on average nationwide, and also leads in most battleground states. A Fox News poll released Wednesday has Mr. Biden ahead in Wisconsin, 49% to 41%. Still, a national poll released this week by Selzer and Company shows that while voters see Mr. Biden in a slightly better light than Mr. Trump, the Democrat’s unfavorability rating ticked up from 42% in March to 48% in August.

And the Biden campaign is clearly concerned about the potential for this issue to fracture his party’s coalition of suburban moderates, minorities, and urban progressives. As President Trump casts himself as the “law and order” candidate, Mr. Biden is trying to thread a political needle by denouncing looting and violence without undermining his bona fides as a champion for racial justice and systemic change.

In Kenosha, where the community is still reeling from Mr. Blake’s shooting and the damage that followed, Mr. Biden’s own supporters offer a range of views. Some Democrats say they’ve been frustrated by the inability of certain mayors and other officials to tamp down the violence, and are relieved Mr. Biden has drawn a bright line. At the same time, some younger progressives say they don’t think he’s focusing enough on the root causes.

Many Black voters here say they are looking for a clearer sense of what Mr. Biden would actually do as president to address the issue.

“Before they even hit the White House, we want something on paper,” says Justin Blake, Jacob Blake’s uncle, at a gathering Tuesday on the street corner where Mr. Blake was shot. “Brother Biden, Sister Harris – take out a pen and show us where you stand.”

A tense scene at the courthouse

On Tuesday, President Trump toured Kenosha’s damaged buildings – blaming “domestic terror” for the “anti-American” violence – and held a roundtable discussion with Republican Sen. Ron Johnson and others at a local high school.

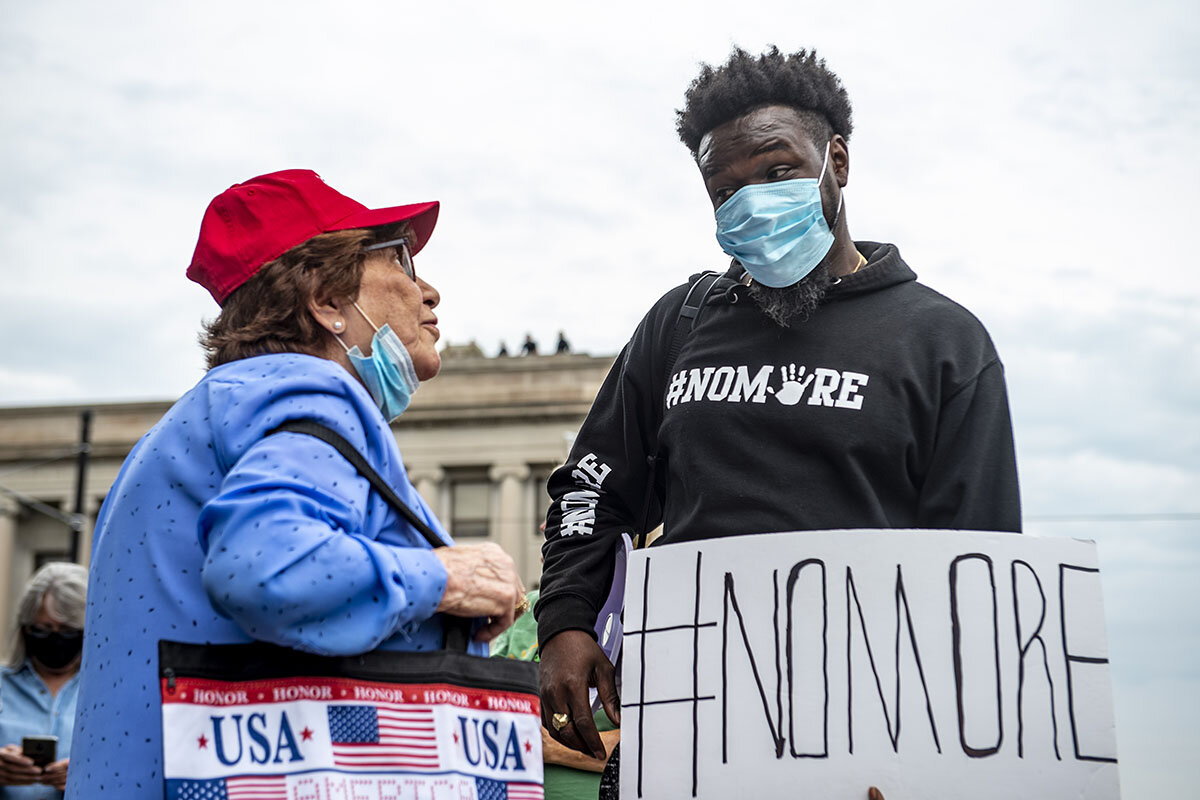

In anticipation of the president’s arrival, hundreds of Trump supporters lined the streets, some waiting in lawn chairs, others surveying the local damage themselves. The scene was tense in front of the Kenosha County Courthouse, where Trump supporters and Black Lives Matter activists yelled at each other in the street, sometimes just inches apart.

After confronting a woman in a red “Keep America Great” hat chanting “All Lives Matter,” Angela Whitfield walks away shaking her head. Ms. Whitfield, who lives in Chicago and has family in Kenosha, says she will “hold her nose” and vote for Mr. Biden in November because she dislikes Mr. Trump so much. But she wishes Mr. Biden would simply say what he thinks, instead of trying to satisfy all sides.

“He should just come out for what he believes in and let the chips fall where they may,” says Ms. Whitfield, a charter bus driver who is now unemployed due to COVID-19. “At least Trump does that.”

Other Biden supporters – primarily white voters – argue the former vice president has made his position clear. They point approvingly to Mr. Biden’s speech in Pittsburgh on Monday, where he disavowed rioting and looting as “lawlessness, plain and simple.” They also note that Mr. Trump has not denounced violence perpetrated by right-wing agitators.

Wendy, who declines to give her last name, holds a sign that simply reads: “Biden denounced all violence.” “That’s really all you have to know about it,” she says. “He’s the only candidate in this race who has done that.”

Farther down Sheridan Road, past dozens of charred cars, Mark Stevens sits atop a three-wheeled bike with a T-shirt that says, “Don’t blame me, I voted for Clinton.” Just a few yards away is a makeshift memorial to Anthony Huber, one of two protesters whom authorities charge were fatally shot by Kyle Rittenhouse, a 17-year old from Illinois, during a skirmish.

On the night of the worst violence, Mr. Stevens recounts, his son used an orange plastic bucket filled with water to try to douse cars that had been set on fire until the police told him to go inside. He says he’s glad Mr. Biden has taken a strong stance.

“I think he’s come out very forcefully. Whether you’re on the right side, the left side, liberal or conservative, all this has to stop,” says Mr. Stevens. “He said very strongly, this is wrong.”

Still, Marilyn Gunderson, a lifelong Democrat who couldn’t understand why some of her relatives were voting for “that nut” Donald Trump in 2016, now says she won’t be voting for Mr. Biden in the fall. She criticizes local and state Democrats in Wisconsin as well as nearby Chicago for being unable or unwilling to tamp down the unrest.

“They should have got help here right away, and that boy wouldn’t have shot those people,” she says, referring to Mr. Rittenhouse.

At the same time, Arcadia Schmidt wishes Mr. Biden wouldn’t condemn the violence at all. The Milwaukee college student, who’s been in Kenosha for much of the past week, says violence isn’t just limited to protests. It’s also a form of violence to not invest in marginalized communities, she says, adding that property isn’t worth more than human lives – a point that was echoed in a weekend rally in Kenosha.

Ms. Schmidt, who identifies herself as affiliated with the Democratic Socialists of America, says it seems like Mr. Biden is not “in full support of the protests.”

“I don’t think it’s his place to say [violence is] wrong or not – and I think if he does it’s just going to alienate people,” she says. “People don’t have any other options. If you’ve taken away everything, what else can they do?”

“Just stand on the truth”

Some Kenoshans say Mr. Biden actually faces less of a balancing act than it seems – because the majority of his supporters, outside the extremes, share the same basic goals: They want progress on racial justice, and they are opposed to violence.

“Just stand on the truth,” says state Sen. Lena Taylor, who has represented Wisconsin’s 4th district since 2005. “And then you can stand firmly.”

Mr. Biden won the crowded Democratic primary in large part because of resounding support from Black voters in South Carolina, many of whom viewed Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, a Democratic Socialist, as too far to the left. He has resisted calls to defund the police – a rallying cry of progressive activists – although he has suggested withholding federal dollars from police departments who violate new national standards. He also says he would provide $300 million for departments to invest in body cameras and recruit more diverse officers.

The Biden campaign is directing $45 million into a new TV ad campaign that features excerpts of Mr. Biden’s Pittsburgh speech calling for the prosecution of rioters and looters, and hitting back at Mr. Trump. “His failure to call on his own supporters to stop acting as an armed militia in this country shows how weak he is,” the former vice president says.

“Biden’s been forceful about rejecting violence in all forms – and that’s good, and it’s different from Trump,” says Rita Kirk, a professor and political communications expert at Southern Methodist University. “What he hasn’t done is distinguish his plan of action.”

Indeed, while Mr. Biden has proposed various reforms on policing and to combat systemic racism, his plans haven’t seemed to reach many young voters in Kenosha.

“I have not even seen Biden’s response, but a response is not what we need,” says Gabi Taylor. “Change the laws.”

Her friend Vaun Mayes, a community activist with the group ComForce MKE in Milwaukee, watched Mr. Biden’s speech on Monday and said it disappointed him – particularly when Mr. Biden referenced his past record as a reason to trust him.

“I was like, ‘Really, Biden?’” says Mr. Mayes, noting Mr. Biden’s role in passing the 1994 crime bill, which is seen as a key contributor to mass incarceration of Black Americans. “You have to be careful when you reference your history as some sort of badge.”

Nevertheless, Mr. Mayes says he’ll vote for Mr. Biden in November, because the current president “has got to go.”

Likewise, Yvonne, who lives across the street from where Mr. Blake was shot and watched at the window with the person who filmed the viral video of the incident, was unimpressed with Mr. Biden’s comments in Pittsburgh.

“It’s nothing to make us trip over each other on our ways to polls,” says Yvonne, who declines to give her last name. “But I’ll vote for him,” she adds, throwing up her hands, “cause I’m a Democrat.”

Patterns

Biden or Trump? Rival policies on China keep world guessing

Foreign policy is not grabbing the U.S. presidential election headlines, but the next administration’s China policy will have major repercussions – economic and political – for the rest of the world.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Foreign policy may not be at the front of most American voters’ minds, but a lot is at stake for the rest of the world in the U.S. presidential election.

Key is how Washington will meet the challenge posed by an increasingly powerful, autocratic and assertive China. A lot of other countries, especially U.S. allies, will take their cue from the next president.

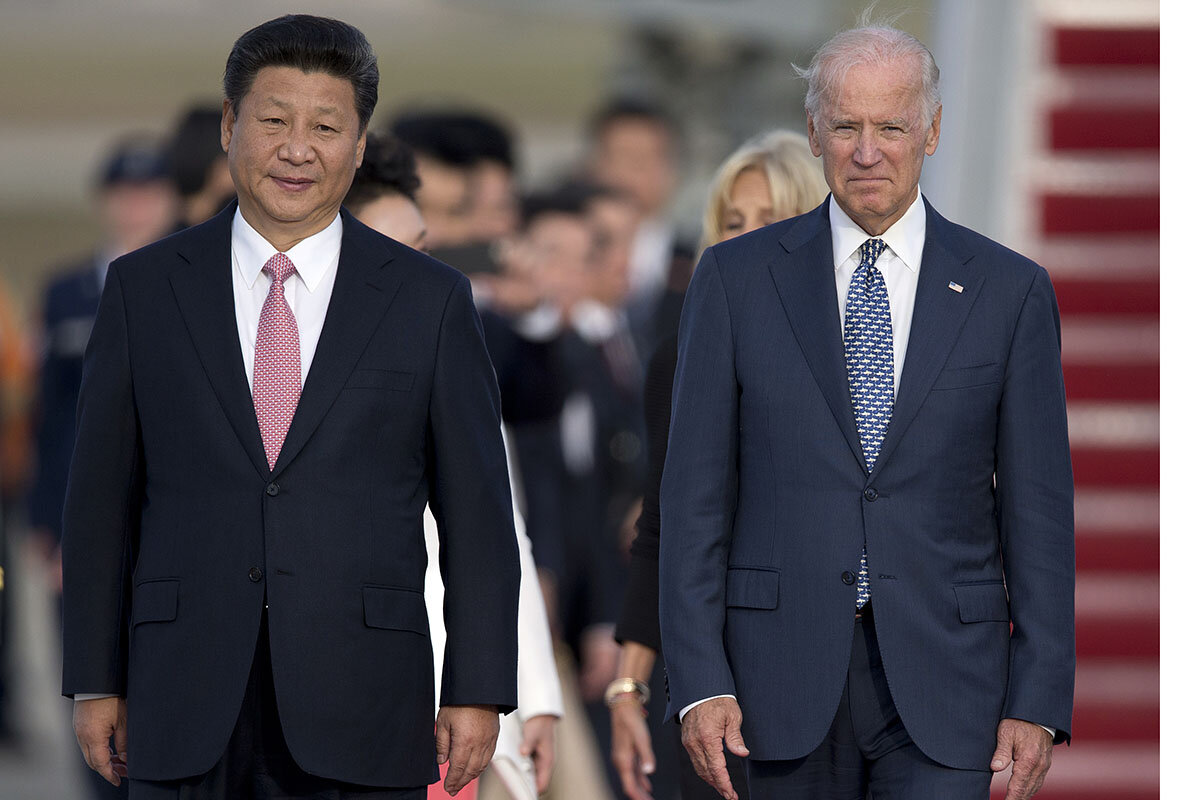

President Donald Trump would likely maintain his bilateral mano a mano with Chinese leader Xi Jinping, trying to squeeze more concessions out of him. Joe Biden would be more likely to take a multilateral approach in the belief that Washington can exert more pressure in concert with international partners.

Managing the rivalry with Beijing will be dauntingly difficult, given China’s increasing economic clout and Mr. Xi’s disregard for Western concerns over human rights or the future of Hong Kong.

Which of the two candidates’ policies would be more successful is still a matter of partisan debate. The rest of the world will be watching the outcome.

Biden or Trump? Rival policies on China keep world guessing

It may get lost amid the sound and fury of the most bitterly contested U.S. presidential campaign in decades, but American voters will be deciding more than just their own country’s future during the homestretch weeks until Election Day.

Foreign policy – above all, America’s intensifying rivalry with an increasingly powerful, autocratic and assertive China – is also on the ballot.

The choice could determine the future of the world economy and the course of globalization. More immediately, Washington’s approach will impact how other countries around the world, especially traditional U.S. allies, deal with the Chinese – one reason that they’ll be following the election returns in November with a particularly close eye.

No matter who wins, the chances of an early thaw with Beijing are remote. In a dramatic political shift from just a few years ago, neither of America’s two main political parties, and neither of the presidential candidates, appears in a mood for that.

Judging by President Donald Trump’s first term in office, his approach would be bilateral, a kind of mano-a-mano contest with Chinese leader Xi Jinping, deploying the full range of economic and political pressure tools to prize concessions from Beijing. His Democratic Party challenger, Joe Biden, has long favored a multilateral approach, rooted in the view that the U.S. can exert more influence and pressure in concert with international partners.

Navigating the U.S. rivalry with China, the world’s second-largest economy, will be a dauntingly difficult task for either of them. Over the past two decades Beijing has become a major player in world trade, investment, and financial markets. It has also been pouring enormous resources into high-technology research and development.

Not that long ago, America’s foreign-policy establishment (including Joe Biden) was encouraging China’s economic rise, hoping that a China integrated into the world economy would become less authoritarian and more open to international cooperation.

But even before Mr. Trump’s election in 2016, doubts were hardening. Barack Obama and then-Vice President Biden had become increasingly concerned by China’s intellectual property theft, restraints on market access, and anti-competitive state subsidies – as well as its military expansion in the South China Sea.

Hopes of liberalization have faded. Mr. Xi has tightened his hold on power and clamped down on dissent; earlier this year he effectively tore up the “one nation, two systems” agreement under which Britain returned Hong Kong to Chinese rule, launching a security crackdown on pro-democracy activists there.

And then came the COVID-19 pandemic, originating in China and initially hidden from the outside world. China’s international reputation plummeted, especially once it had turned back the virus at home and launched a propaganda offensive criticizing Western nations’ response.

But an even more profound impact of the pandemic on U.S. politics was that it drove home America’s growing economic interdependence with the Chinese: a wide range of urgently needed protective equipment could be found only in China.

Over the past few months, Mr. Trump has ratcheted up pressure on Beijing, significantly tightening U.S. sanctions, due to take effect this month, on the giant Chinese technology company Huawei. Unless waivers are granted, the move to deprive the company of essential microchips could have an enormous impact on its production capacity.

The case of Huawei – which, with the help of state loans, has become the world’s leading supplier of telecommunications network infrastructure – explains why the U.S. election, and Washington’s future approach to relations with China, are of such keen interest worldwide.

Washington has been leaning on other countries, especially traditional allies in Europe, to follow its lead and exclude the Chinese company from any involvement in their new 5G telecoms networks. And Mr. Trump’s sanctions might mean that Huawei would not even have the hardware it needs to build European 5G networks.

A Biden administration would be unlikely to change Washington’s view of Huawei, if only because of a broad consensus in the American security community that the company could use a 5G role to steal information.

But Mr. Biden has stressed that if the U.S. is to reduce its dependence on Chinese suppliers in key sectors, the country will have to invest in its own domestic research, innovation and production. With signs that European nations are also keen to build up capacity in firms nearer to home, like the Swedish firm Ericsson and Finland’s Nokia, a Biden administration would likely seek a coordinated approach among U.S. allies.

On trade, Mr. Biden seems increasingly to share Mr. Trump’s view of the need to take a tougher line against Chinese practices. Yet the likely shift would be away from using tariffs as a unilateral tool, in favor of a joint strategy with allies, both in Europe and Asia.

Which approach would better manage and recalibrate ties with China remains a matter of intense partisan debate as polling day approaches. But as both parties frame the election as a critical choice for America’s future, the question of future U.S. policy toward Beijing is a major reason why the rest of the world is watching too.

Why US wants Saudis to follow UAE’s path to nuclear energy

Learn from example. In its global competition with China, the rules-heavy U.S. often finds itself at a competitive disadvantage. Which explains, as it woos the Saudis, the value of the UAE's by-the-book nuclear power plant.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

With its first civilian nuclear power plant coming online last month, the United Arab Emirates has become the first in a line of fossil fuel-rich Arab states scrambling to go nuclear. The UAE says nuclear energy is critical to lowering its dependency on gas and oil, and its nuclear cooperation agreement with the United States has been hailed as the “gold standard.”

Yet concerns remain over nuclear proliferation and the potential for an arms race in a region wracked by divisions. Perhaps of most concern to the U.S. is its opaque ally, Saudi Arabia, which says it plans to build 16 nuclear reactors across the country by 2040. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has vowed to pursue a nuclear weapon should Iran do the same.

The country insists it has a sovereign right to mine its own uranium, and China, which is helping it do so, is wooing Riyadh with low-cost nuclear technology and few nonproliferation strings attached.

“We are keenly aware of the fact that other governments, specifically the Russians and Chinese, use their lower nonproliferation standards as an economic advantage,” says a State Department official. “The message we are providing ... is: Who do you want to be partners with?”

Why US wants Saudis to follow UAE’s path to nuclear energy

Home to the fifth-largest natural gas reserves and sixth-largest oil deposits in the world with a population the size of New York City, at first glance the United Arab Emirates does not seem an obvious candidate to spend billions to split the atom for energy.

With its Barakah nuclear power plant coming online last month, the UAE has become the first Arab country to successfully pursue civilian nuclear power – and the first in a line of fossil fuel-rich Arab states scrambling to go nuclear.

The UAE and its neighbors say civilian nuclear energy is critical to lowering their dependency on gas and oil, and the UAE’s 2009 nuclear cooperation agreement with the United States has been hailed in Washington as a “gold standard” for pursuing civilian nuclear power.

Yet concerns remain over nuclear proliferation and the potential for an arms race in a region wracked by political divisions and little transparency. That leaves the U.S. to play a pivotal role to ensure its Arab allies’ pursuits remain peaceful – and within its ability to influence.

Of the countries in the region, perhaps the one of most concern to the U.S. is its longtime yet opaque ally, Saudi Arabia, which is determined to follow the UAE and become the second Arab state with nuclear power.

With China and Russia making overtures to Saudi Arabia, Washington is trying to win over and convince Riyadh to follow the Emirates’ peaceful path at a time Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has vowed to pursue a nuclear weapon should Iran do the same.

The U.S. is embroiled in talks with the kingdom to enter a nuclear cooperation agreement that would allow it to benefit from U.S. technology and expertise.

Saudi Arabia says its intentions to build 16 nuclear reactors across the country by 2040 are meant to free up its domestic oil production for exports abroad – to China, India, and others.

Ambiguity ... and clarity

Yet the Saudi energy program is shrouded in ambiguity, even confusion. Saudi rulers have shuffled the program between various government and royal agencies as it has stumbled to get off the ground, with few technical advancements.

Concerned observers and veteran diplomats point to statements made by the crown prince during his visit to the U.S. in March 2018 that left no room for similar ambiguity over Saudi intentions should Iran pursue a nuclear weapon.

“Without a doubt, if Iran ever developed a nuclear bomb, we would follow suit as soon as possible,” Crown Prince Mohammed told CBS in an interview.

“Given Mohammed bin Salman’s statements and [Saudi Arabia’s] refusal to sign protocols on uranium enrichment, we cannot rule out the program being used for military reasons,” says Antonino Occhiuto, analyst at the U.S.-based Gulf States Analytics.

“Saudi Arabia has substantial quantities of uranium in their soil, which would allow them to develop a noncivil nuclear program if they choose to.”

Given these sentiments, China’s courting of Saudi Arabia and the ongoing uranium exploration and mining activities of a state-owned Chinese company in southwest Saudi Arabia, one of several extraction “collaborations,” have triggered alarm in Washington.

A Wall Street Journal report last month called the Chinese uranium exploration in the southwest part of a project for a yellowcake mill.

In response, members of Congress petitioned the State Department for “information regarding the People’s Republic of China’s reported transfers of nuclear and missile technology to Saudi Arabia.”

Multiple bills introduced this year require regular reports on Saudi nuclear efforts.

“On the surface, this is not a nefarious enterprise, and the alarm is inappropriate,” says Mark Hibbs, senior fellow at Carnegie’s Nuclear Policy Program.

“But in a situation in the Mideast where we have all these ambiguities, a legacy of clandestine nuclear activity, coupled with provocative statements by the Saudi Arabian government, it is only natural for people to ask whether these investments and projects have a nefarious intent.”

Who do you want to partner with?

As a consequence, the U.S. Department of Energy, Congress, and the State Department are all pushing Saudi Arabia to follow the example of the UAE, which surrendered its right to extract, enrich, or process uranium as part of its cooperation agreement.

The UAE has met all the stringent requirements, which observers call “the highest nonproliferation standards in the industry.” Its South Korean-built 1,400-megawatt Barakah reactor is the first of four reactors that are planned to provide 25% of the electricity needs of a tiny country that has seen its demand for electricity increase 150% over the past decade.

The UAE says its nuclear energy is to power its desalination and complement its growing solar energy sector.

U.S. officials say they are “comfortable and confident” that the Emiratis' abidance by the strict nonproliferation safeguards will prevent the military use of nuclear materials and technology.

But the Saudis have been resistant to follow suit, and talks have stalled for years, even under a Trump administration close to the crown prince and eager to strike a deal that would allow American companies to take part in the Saudi nuclear project.

Saudi sources close to decision-makers say Riyadh insists it has a “natural sovereign right” to extract and process uranium from its own soil to fuel its peaceful nuclear energy program and sell abroad.

China, meanwhile, has attempted to win over Riyadh with low-cost nuclear technology with few strings attached.

With lower nonproliferation standards and transparency, Chinese-Saudi cooperation would allow Saudi Arabia to pursue nuclear energy without the safeguards desired in Washington.

“We are keenly aware of the fact that other governments, specifically the Russians and Chinese, use their lower nonproliferation standards as an economic advantage,” says a State Department official with knowledge of the nuclear file.

In response, while insisting on its nonproliferation standards, the U.S. is highlighting to any Arab state considering pacts with Beijing or Moscow that the development of nuclear energy “is not just an economic relationship, [but] a strategic and political relationship.”

“The message we are providing to these governments is: Who do you want to be partners with over the next quarter-century to half-century?” the official says. “Our hope is that these governments will recognize that in the long run their security and political interests are much better served to partner with Washington.”

Regional hazards

The mere presence of nuclear reactors in a Gulf region wracked with tensions, divisions, and asymmetrical warfare could be a security threat.

The UAE will be shipping enriched uranium fuel and radioactive waste through the waters of the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz, narrow shipping lanes between Gulf states and Iran that have recently witnessed acts of sabotage and are a flashpoint of U.S.-Iran tensions.

And just last year, a series of crude drones struck at the heart of Saudi Arabia’s ARAMCO oil processing facilities, causing immense damage and bringing Saudi oil production offline.

Missiles from neighboring Yemen fall onto Saudi territory on a regular basis, even striking the capital, Riyadh. Iran-backed proxies across Yemen and even Iraq have entrenched ballistic missiles pointed at Gulf cities and sites as a defensive line should Tehran feel threatened.

Already in 2017, Houthi rebels claimed to have fired a missile at the then-under-construction Barakah nuclear power plant, a claim the Emiratis have denied, insisting their air defense system is “capable of dealing with any threat of any type or kind,” says Paul Dorfman, senior research fellow at the University College London Energy Institute and former adviser to the British government on nuclear plant decommissioning.

“Recent military strikes on Saudi infer that the region is still very volatile. There really is no parallel elsewhere in the world,” he says. “The idea of Iran sending missiles into Saudi or Emirati nuclear facilities – what would happen then?”

To the Russian manor born: Public gets a rare chance to walk historic halls

The concept of opening up restored old mansions to the public is familiar in the West, but in Russia, it is a new idea. One Russian banker is running with it, and giving Russians a chance to experience history.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Before investment banker Sergei Vasiliev bought it, the Kurakin palace was just one of the thousands of abandoned aristocratic estates decaying in Russia. Though the 32,000-square-foot palace had served as a psychiatric institution during the Soviet era, it was a far cry from its former 19th-century glory.

Mr. Vasiliev decided to fix that. Working from archival materials like letters and diaries of people who attended parties at the palace in its heyday – and making a lot of educated guesses – he has restored dozens of rooms, corridors, and the grand staircase to their former appearance. Moreover, he has opened it up to the Russian public, thousands of whom have been coming during the past couple of years, mainly in day trips from Moscow, some 100 miles to the east.

“You can’t just call this a ‘restored estate,’” says Vadim Razumov, a blogger and photographer who documents pre-Revolutionary noble estates in Russia. “He didn’t build a fence around it, but opened it for people to come and experience a piece of history. ... In Europe there are places like this, old castles and estates that have found a new public purpose, but this is a whole new thing in Russia.”

To the Russian manor born: Public gets a rare chance to walk historic halls

A huge, glittering aristocratic palace, surrounded by rambling gardens, quiet forests, and well-stocked fishing ponds was once a fairly common sight in the Russian countryside, at least in czarist times. Always nearby would be the impoverished villages of peasants who toiled on the land, provided servants for the great house, and soldiers for the czar’s army.

But a century ago, amid revolution and civil war, the owners of these extravagant estates fled, leaving their lavish homes to be burned, swallowed up by the forests, or used as stables or storehouses for collective farms.

One of those was the estate of the Kurakin family, who lived in a lavish, sprawling palace at Stepanovskoye-Volosovo for almost 200 years before that last members of the clan were evicted by the Bolsheviks in 1918. The main building was used as a mental health facility for much of the Soviet period, gradually decaying until its main wing burned down in 2005.

But then a very wealthy Russian investment banker, Sergei Vasiliev, took an unusual interest.

He spent years navigating the murky legal environment with the aim of purchasing the ruined estate and, once he acquired title, began pouring in millions of dollars of his own money to restore the palace and its grounds to its former 19th-century glory. Today, though he and his family often live there, he has opened it up to the Russian public, thousands of whom have been coming over the past couple of years, mainly in day trips from Moscow. Notes in the visitors’ book express appreciation, wonder, curiosity, and none of the old Soviet-era hostility to the idea of a magnificent, privately owned palace that’s stuffed with valuable art works.

“You can’t just call this a ‘restored estate,’” says Vadim Razumov, a blogger and photographer who documents the condition of some 80,000 pre-Revolutionary noble estates in Russia.

“What Sergei Vasiliev did was to restore it as a living estate that produces its own food and generates a way of life. He didn’t build a fence around it, but opened it for people to come and experience a piece of history. ... In Europe there are places like this, old castles and estates that have found a new public purpose, but this is a whole new thing in Russia.”

The Kurakin estate

The Soviet regime turned a few czarist palaces into museums or art galleries, so that people could come and view the extreme luxury in which their former masters had lived and, at least symbolically, regard it as their own. It was not an unpopular aspect of Soviet life. But in the economic and political turmoil that followed the USSR’s collapse, almost no one gave much thought to the thousands of decaying manorial estates whose remains still dot the Russian countryside.

Only recently has it even occurred to anyone to try counting them. A recent effort by culture officials in Tver region, which lies between Moscow and St. Petersburg, found that of the 1,230 noble estates that had existed in the province in 1918, only 133 are still in any shape to be registered as worthy of state protection. Of those, just eight are in “satisfactory technical condition.” Officials in Tver say they have no funds for reviving any of these objects, and the only hope is to attract private investors. And the positive example they cite is the Kurakin estate.

The Kurakin family produced several leading diplomatic lights during the 18th and 19th centuries. But if the name sounds vaguely familiar even to those not well versed in Russian diplomatic history, it may be thanks to the great Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy, who was fond of fictionalizing the preeminent aristocratic families of his world by slightly altering their name. A notable character in War & Peace is the roguish Anatole Kuragin, who wreaks a great deal of mischief in Russian high society along with his sister, the beautiful but calculating Helena Kuragina. That’s a fun fact that actually draws visitors to the restored estate today.

Photos from a decade ago show the former palace a dilapidated and thoroughly-looted wreck, with fire-scarred walls, weeds growing from the floors, and an earthen ramp where the grand entrance had been. Mr. Vasiliev, working from archival materials like letters and diaries of people who attended parties at the palace in its heyday – and making a lot of educated guesses – has restored dozens of rooms, corridors, and the grand staircase to their former appearance.

“I have no aristocratic roots. I was a regular Soviet guy, who graduated in 1990 as an aeronautical engineer,” says Mr. Vasiliev. “I became a successful investment banker and there was a time, before the global crisis of 2008, when it seemed like you could put money into anything and it would grow. That’s when I got the idea to rebuild this place. But even after the crisis, when things were tougher, I didn’t put it on pause. A project like this lasts a lifetime. Once you begin, you can’t stop.”

He and his family have scoured antique shops and flea markets in Europe to find compatible furniture, knick-knacks, drapes, and carpets. The art works adorning the walls are copies of ones that might have hung there, including a complete set of lithographs painstakingly re-acquired from a 19th century list found an old archive. The grounds, including an apothecary garden, ponds, gazebos and quiet forest paths, have all been brought back and, on a summer weekend, are full of curious tourists.

The rebirth isn't confined to the estate grounds, says Mr. Razumov. “The surrounding villages are coming to life, because it provides jobs. Tourists are coming, and in future we might see hotels, restaurants and other services flourishing all around.”

Olga Murashova, from the neighboring village of Dorozhaeva, says many local people have found work in the restoration project, and she herself earns good money giving guided tours of the estate to visitors who wish it.

“You can’t believe what it was like around here before,” she says. “Mud, desolation, everything overgrown with weeds and brush. The only inhabitants were moles. There wasn’t much work to be found. So, are people happy about what Sergei Anatolyevich [Vasiliev] has done here? Of course we are.”

“Bigger than a piece of family property”

“I had originally thought of this as a country retreat for my family, but my ideas changed as the project developed,” says Mr. Vasiliev. “I learned the history of the place, and the family that had occupied it. And as I delved into that, I got drawn into the parade of Russian history that they were so closely connected with.

“The palace is huge – about 32,000 square feet – and it took years to restore. As I worked at it, I came to the realization that you just can’t close something like this off, it needs to be open to people,” he says. “It’s not that the state ordered me to do anything, I just knew that it’s something bigger than a piece of family property.”

That’s not a common attitude among Russia’s new rich, but it may be creeping up on them. In Russian cities, old gems of architecture have long since been restored, almost exclusively for commercial purposes, and that process has changed the outward appearance of even many smaller provincial towns over the past couple decades. But the fate of decaying pre-Revolutionary countryside manors is more troublesome: They tend to be bottomless money-pits, with minimal commercial potential.

“There are plenty of examples in Europe, where you can buy a ruin and take your time deciding how, or whether, to restore it,” says Dmitry Oynas, an adviser on property issues for Russia’s Ministry of Culture. “In Russia, the state still places too many conditions on new owners, and requires them to restore the property within 5 years. But not everyone is Sergei Vasiliev.”

Still, he says, in the past few years there has been a growing trend to purchase and renovate old houses, not just of the grand residences of the aristocracy but also homes of the merchant and rich farmer classes in czarist Russia.

“People are becoming aware of the tourist potential of these old structures, and the fact that they still have utility. When they’re fixed up, they still make great homes,” he says. “And the larger society doesn’t reject the idea of such property anymore. People have accepted the principle that an owner is someone who bears responsibility for these objects, even while the public regards them as its own general heritage.”

As for Mr. Vasiliev, he plans to carry on restoring the estate, to extend its farmlands and perhaps revitalize some of the craft industries that used to thrive here, such as linen, cheese, bricks, and beer that was sold as far away as Moscow.

“I am not interested in profit, but I’d like the estate to become self-sufficient,” he says. “I’ve looked at some European examples, so I know it’s possible. I don’t want the state to give me anything.

“But, well, they could improve the local infrastructure,” he adds. “The roads leading here are terrible, and the only bridge giving access to the estate was built by inmates of the mental hospital after World War II. Yes, I wish the government would fix the roads.”

Movies bring us together. But should we get used to viewing them apart?

Very little can replace the collective laugh or gasp in a theater as a movie unfolds. But how might that experience be evolving – with streaming splintering our attention and a pandemic closing cinema doors?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Theaters in the U.S. are hoping that “Tenet,” a science fiction thriller opening on Thursday, will remind viewers that a cinematic spectacle is best viewed on the largest screen possible.

The public’s drift away from theaters may last past the pandemic and its closure of gathering places, pop culture experts say. Now accustomed to Hollywood releasing films straight to streaming services and video on demand – think "Mulan," arriving Friday on Disney+ – audiences may encourage studios to sometimes bypass cinemas altogether.

While this feels like a further erosion of shared cultural experiences, experts say that, thanks to technology, physical proximity isn’t the only means of sharing communal experiences. They champion the variety and creativity sparked by multiple platforms.

“We have discovered that our creative possibilities as a nation, as a society, and the world are so vast that the future from that sense looks bright,” says Timothy Burke, a cultural historian at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania. “We are not going to run out of things worth seeing together and apart.”

Movies bring us together. But should we get used to viewing them apart?

For Duane Miller, seeing the blockbuster “Tenet” on Monday was a kind of homecoming.

Anticipating his first big-screen outing in six months, the film buff says even the elevator ascent to the AMC South Bay Center 12 in Boston was exhilarating. The only thing missing was the smell of popcorn – state pandemic regulations still prohibit concessions – and a regular audience. Due to social distancing, the sold-out late afternoon show included just 25 masked viewers scattered about the 241-seat IMAX auditorium – and an eerily quiet lobby.

“It’s not the same feeling, you know, as when you see it the first time with a bunch of people,” says Mr. Miller, founder and host of the “Cinemania World” podcast. “A crowd environment makes the moment better because, like, when I saw ‘Avengers: Endgame’ for the first time, that crowd was crazy. I saw ‘Endgame’ in theaters eight times.”

Shared experiences at the movies may diminish in the wake of the pandemic, as Hollywood releases more films straight to streaming services and video on demand and people partake of debuts in a new way (consider “Mulan,” arriving on Disney+ tomorrow). The sidelining of big-screen entertainment comes at a time when music and sports venues remain shuttered to crowds, too. But some pop culture watchers say that thanks to technology, physical proximity isn’t the only way for people to share culture. By some accounts, pop culture has never been more diverse, dynamic, and available for people to connect with.

“The trend is towards fragmentation and towards a reduced number of universal experiences,” says Peter Suderman, a features editor and film reviewer at Reason magazine who just wrote an article titled “A Summer Without Summer Movies.” “There may be some downsides to that, but there is an upside as well. There’s so many more things out there for us to watch and look at and experience. And they are more likely to be individually tailored towards our particular interests and niches and desires.”

Movie theaters are hoping that Christopher Nolan’s “Tenet,” a science fiction story as nonlinear as an M.C. Escher illustration, will remind viewers that the communal setting of a big screen is still the optimal way to experience a high-octane blockbuster. Its car chase scene, in which vehicles drive in reverse on a busy highway, would make even Dale Earnhardt Jr. flinch.

That movie, which officially opens today, and the few other new releases could play for months on end given that there’s less in the pipeline from Hollywood. Even before the pandemic, multiplex fare was increasingly action-oriented and targeted at creating shared experiences mainly for the demographic most likely to go to the theater: men under the age of 25. Now, comedies, romances, and midbudget movies such as “The Old Guard” starring Charlize Theron, Tom Hanks’ “Greyhound,” and “Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga” with Will Ferrell are more likely to premiere on Netflix, Amazon, and Apple TV+.

Anne Thompson, who writes the blog “Thompson on Hollywood” for Indiewire, says that you can’t easily replace a theater experience, and the shared response and empathy you feel watching a movie. “That is how a movie like ‘12 Years a Slave’ can have an impact on a culture. ... Because that movie became an Oscar contender and ultimately an Oscar winner, everyone had to see it and then share that experience and understand what those characters went through.”

Due to the limited seating in theaters, it will be a while before they can fully meet the demand to view the current movies that are available. That’s reminiscent of an earlier era when the original “Star Wars” played in single-screen theaters for an entire year. And it echoes Steven Spielberg’s prediction in 2013 that movies may become like Broadway plays – just a couple of spectacular big-screen events playing on a screen for a whole season.

“It’s possible that Mr. Spielberg will be right in the long run, but I think that’s a long way off,” says Mark Gill, producer of the Russell Crowe thriller “Unhinged,” which was the first major new release to debut in reopened theaters. He says the pandemic has accelerated the trend toward Hollywood often bypassing the big screen for the small one. “What happens going forward,” he says, “is [studios] will still make some films for theaters, but less of them, and they probably will mostly be the bigger ones.”

For millennia, shared cultural experiences depended upon physical proximity. But the arrival of electronics introduced new forms of communal gatherings. Radio broadcasts created a sense of national cohesiveness and unity. Television kindled a new kind of family hearth. As people began talking about the shows they watched, it created a strong community outside the home, says Paul Levinson, a professor of communication and media studies at Fordham University in New York. With each new technological advancement, it’s the sharing of information that has created a sense of community.

“The World Wide Web has greatly expanded and accelerated this process,” says Mr. Levinson. “The watching of movies online in our COVID age is just another part of this evolution.”

One advantage of home-viewing: You don’t have to worry about kids in the back row pelting the audience with Jujubes. Another is the sheer variety of specialty options available on a proliferation of platforms. Mr. Suderman points to Starz, with its app and cable channel, as an example of a company that produces stories for minority viewers and women over age 25, audiences that bigger Hollywood studios don’t regularly serve. Meanwhile, fans of art house movies can access rich libraries available from companies such as the Criterion Channel and Grasshopper Film.

Some cultural observers suggest that the sense of community created during a two-hour movie is more fleeting than what can be experienced at home, where technology is capable of facilitating richer connections with strangers and acquaintances. When a community is online, it’s often easy to find out more information about others, discovering common interests and perspectives that help deepen relationships. But the decline of in-person communities doesn’t mean the end of them. Seeking out interpersonal contact is still a fundamental part of humanity.

For that reason, theaters aren’t going to completely disappear, says Mike S. Ryan, who has produced art house movies such as Amy Adams’s breakout movie “Junebug” and director Todd Solondz’s “Palindromes.” Some may become even more communal.

“I believe that we are going to eventually, soon return to the Cinema Club situation that we had in the ’60s, where people are able to gather together in small clubs to show films that do not exist on streaming and thus it will be like live music or a singular experience,” says Mr. Ryan, who now teaches at Emerson College in Boston. “I think that eventually that might go to a subscription model,” much like the season tickets people buy for some live theater companies, he says.

The sheer plenitude of options can often feel overwhelming to consumers. But unlike earlier decades, constrained by a narrow band of available media, there’s more opportunity now for the misfits, the outliers, and overlooked talent to find an outlet and create fresh communities. Case in point: the thousands of user-made viral videos on TikTok.

“We have discovered that our creative possibilities as a nation, as a society, and the world are so vast that the future from that sense looks bright,” says Timothy Burke, a cultural historian at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania. “We are not going to run out of things worth seeing together and apart.”

Editor’s note: As a public service, we have removed our paywall for all pandemic-related stories.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Tracking the pandemic on private phones

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Apple and Google plan to embed software in smartphones that would track the spread of COVID-19 from person to person. The basic approach is not new. Personal data collection has been key to containing the pandemic in a few places. Yet even as COVID-19 spurs the gathering of more personal data, it is running into a growing concern over privacy.

While phone users can choose to opt in to these new data collection programs, what happens to that data once the pandemic is over? Will governments or tech companies delete it? Or will it be stored and used either to monitor citizens or to monetize it for profit?

One emerging trend in both law and tech design gives people greater control over their data. It isn’t just about restraining how companies and governments use personal information. Privacy is also a condition of personal conduct. More than a decade after social media and smartphones enabled all of us to make our private lives public commodities, we may be learning that the best privacy protection – in the digital as well as mental and physical spaces wherein we reside – is each person’s capacity for self-governance.

Tracking the pandemic on private phones

In the largely hidden realm of high-tech, Apple and Google are introducing a helpful but potentially Orwellian twist. The tech giants plan to embed software in smartphones that would track the spread of COVID-19 from person to person. A public need would reach deep into private lives.

The basic approach is not new. Personal data collection has been key to containing the pandemic in a few places, such as Rhode Island and the Colombian city of Medellín. Both have developed tech tools to map the coronavirus among their populations. Nearly 90% of Medellín residents have signed up, apparently eager to trade privacy for a greater good. The data collected includes information about such personal matters as food and utility costs as well as whether a family member might have symptoms of the virus. In exchange for this data, sick and needy people have received food aid and money. As of June, in a metropolitan area of 3.7 million people, only three had died of the illness.

Even as COVID-19 spurs the gathering of more personal data, it is running into a growing concern over privacy and each person’s ability to control his or her digital life. The pandemic has shifted the balance toward the public interest. Yet while phone users can choose to opt in to these new data collection programs, what happens to that data once the pandemic is over? Will governments or tech companies delete it? Or will it be stored and used either to monitor citizens or to monetize it for profit?

More than 80% of Americans say they feel they have no control over the way private enterprises and public entities use their data, according to the Pew Research Center. Yet more than 6 in 10 say they do not think it is possible to go through daily life without the collection of data.

As of July, three U.S. states had enacted comprehensive privacy laws while 21 others have measures at various stages in the legislative process. These drafts – which in most cases were underway before the pandemic struck – include provisions giving people greater control over who has access to their information, how it is used, and if it should ever be deleted. The Senate has such a bill in committee. Unlike the European Union, the federal government does not grant a comprehensive right to privacy. That right is instead being established in a piecemeal way, either through Supreme Court rulings or laws on specific issues.

Apple and Google note that only six states have their own apps to track COVID-19. By embedding contact-tracing tools in their operating systems, the tech firms hope to make it easier for people to know when they have been in proximity to others known to have been infected. Twenty-five states and 20 other countries have expressed interest in the new tool.

A revised version of Rhode Island’s app, based on consumer feedback, shows an attempt to resolve some of the privacy concerns that may be preventing it from being more widely used. The new version provides individuals with updated information about the pandemic and testing sites and enables them to keep a detailed location diary. But it keeps all information on the user’s phone. No data is shared with app developers or the state government.

That conforms to an emerging trend in both law and tech design that gives people greater control over their data. It isn’t just about restraining how companies and governments use personal data for either selfish or social gains. Privacy is also a condition of personal conduct. More than a decade after social media and smartphones enabled all of us to make our private lives public commodities, we may be learning that the best privacy protection – in the digital as well as mental and physical spaces wherein we reside – is each person’s capacity for self-governance.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Can racism be healed?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Kwadjo Boaitey

Sometimes big issues, such as racism, can feel too intimidating to face in prayer. But we can each play a part by meeting every temptation to feel inferior or superior to someone else with the powerful recognition of everyone’s identity as a child of God.

Can racism be healed?

I prayed on the day George Floyd, a Black man, died at the hands of a white officer while in police custody. My prayer went something like this: “What, Lord? What do I think? What do I do?”

There was something especially unsettling about the nature of Mr. Floyd’s death. It was such a bold affront against humanity. Yet the broadcast of a death under similar circumstances, filmed on cell phones by witnesses, is something we have seen, heard, and read about many times before.

My prayer on that day led me to read through the weekly Bible Lesson found in the “Christian Science Quarterly” many times. It contained powerfully healing passages from the Bible and from “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, and I held close to them that whole week, praying to know that the Holy Spirit was with me and all.

Because of healings I have experienced over several decades in my practice of Christian Science, I know with conviction that God, Life itself, loves every one of us as His children. So, I continued to pray knowing that I would have a satisfying answer to my initial question: “What, Lord?”

My answer came when I read this statement in Science and Health: “Evil has no power, no intelligence, for God is good, and therefore good is infinite, is All” (pp. 398-399). I realized instantly that injustice is not just an affront against humanity, it is a bold affront against God, divine Love. With that realization my spiritual resolve was renewed. There is no power greater than, equal to, or other than God. The prophet Nahum in the Bible wrote: “The Lord is good, a strong hold in the day of trouble” (Nahum 1:7).

There has been promising evidence of a turn in the direction of rejecting evil. For instance, there has been a widespread outcry to heal racism.

In Science and Health, Mrs. Eddy speaks of being alert to the fact that, to those who are ill, “sickness is more than fancy; it is solid conviction.” This can be said of sin, too. As I pray about the sin of racism, I find this idea instructive because it says to me that racism needs to be taken seriously in our prayers, challenged, and healed. Science and Health shares how to handle a “solid conviction” and heal it. It is to be dealt with and destroyed “through right apprehension of the truth of being” (p. 460).

As I prayerfully consider the “right apprehension of the truth of being,” I think about my own identity as a Black man, and the identity of other Black men and women, and I am reminded of my favorite explanation of what we all truly are, which also appears in Science and Health: “Identity is the reflection of Spirit, the reflection in multifarious forms of the living Principle, Love” (p. 477).

We are each the reflection of Spirit, God; we reflect Spirit, God, now; what we are, and all that we truly are, is made of the spiritual substance of God, infinite Love; we are Love’s reflection; God is All; therefore, we are each God’s child, Spirit’s image.

There are many, many times in my life when an understanding of my own and others’ identity as a child of God has combated instances of racism. (For example, see “From racial profiling to ‘You are my brother,’ ” Christian Science Sentinel, March 7, 2011.)

I have also learned that meekness in the presence of Almighty God is not weakness, but strength. In the Bible there are numerous examples of people from humble beginnings who acknowledged and experienced God’s presence and power. And in the life and example of Jesus, the Son of God, his pure sense of God’s ever-presence and all-power healed and transformed lives and forever changed the world.

The accounts of Jesus’ healings show us we are each the reflection of the Almighty God, so none of us are inferior to anyone else, nor can we be made to feel inferior. There is none greater than God, whom we all reflect.

It’s true that every Black life matters, because each and every one of us is equally essential to God, made in God’s own image and likeness, spiritual and good. This spiritual reality removes the grip of any “solid conviction” to the contrary.

This is how I am taking steps to heal racism. Holding a correct, purely spiritual view of each of us as God’s loved creation protects and heals.

A message of love

Alpine trek

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow. We have a delightful tale of adventure amid the pandemic, via an RV named Maybell.