- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Can friendship be bipartisan? Ask the Janets.

- Republicans have dominated redistricting. Here’s why that could change.

- Online misinformation is rampant. Four tips on stopping it.

- Corporations pledge to fight racial inequality. Will it work?

- Outsiders turned icons, South Africa’s jacarandas spring into bloom

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Hope for our ‘more perfect Union’

The first time I covered a president running for reelection was in 1996, when I joined the Clintons and Gores as part of the traveling press corps on a heartland tour.

What seemed normal then – the candidates and their spouses diving into crowds, shaking hands – feels alien today. Also remarkable were the Republican voters in the crowd who had no intention of voting for President Bill Clinton but came anyway, camcorder in hand, kids in tow. “I wanted my children to see the president,” Lee Elliott, a Kentucky physician, told me.

Today, America seems unable to find common ground on anything, from the trivial – buy a sandwich at Chick-fil-A, yes or no? – to the profoundly important, such as how to behave during a pandemic. Large majorities say declining trust in the federal government, and in each other, is making it harder to solve the nation’s problems, according to the Pew Research Center.

How can we as individuals be part of the solution? For starters, we can do our part to keep a fraying civil society from getting worse.

One answer may be as simple as maintaining old friendships, even when opinions diverge sharply. As a political reporter, I have the privilege of talking to people with sincerely held views from across the political spectrum, and can honestly say that most Americans love their country and want the best for it and its people.

When this campaign is over, the nation will have an opportunity. We can take a deep breath, be grateful for what we have, and then set about making our “more perfect Union” even better.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Can friendship be bipartisan? Ask the Janets.

As the nation goes to the polls during one of the most fractious moments in U.S. history, two longtime friends who are ideological opposites show how a country can disagree with civility and respect.

How will we ever be able to discuss politics with those who voted on the opposite side today? Ask the Janets.

Since joining the same sorority at the University of Southern California in the 1960s, they have navigated more than half a century of friendship as their careers, life experiences, and ZIP codes have caused their political viewpoints to evolve in different directions.

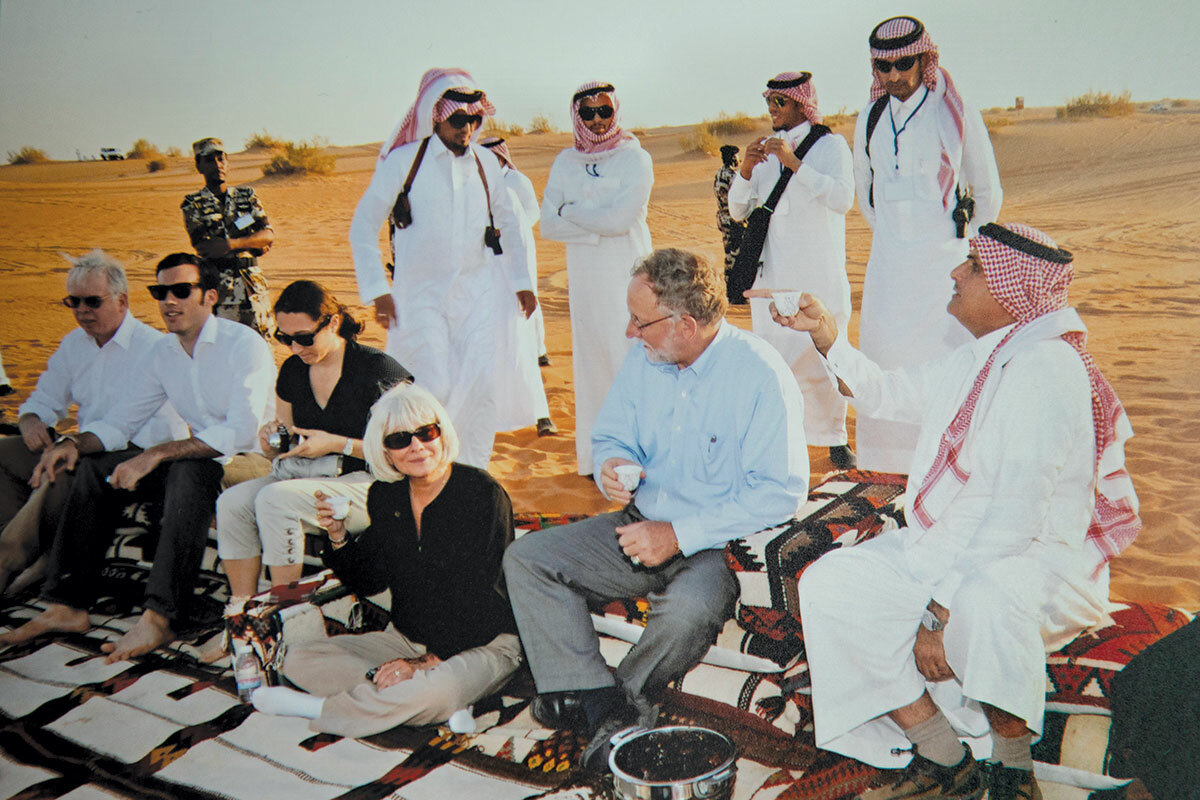

Janet Nelson, an independent voter and business owner, admires how President Donald Trump stands up for America internationally and bucks political conventions at home. Janet Breslin, a Democrat who lived through the 1973 coup in Chile and joined her husband when he served as President Barack Obama’s ambassador to Saudi Arabia, worries that Mr. Trump exhibits strongman tendencies.

Yet through their ongoing discussions, they illustrate how two people can withstand the centrifugal pull of partisanship, gaining a deeper understanding of each other’s political views – even as they still wrestle with key issues and the man up for reelection today.

“Jan and I are some of the few people who kind of keep working this. A lot of people are like – forget it,” says Dr. Breslin, who chairs her local Democratic committee in New Hampshire. “We keep trying to convince each other.”

Can friendship be bipartisan? Ask the Janets.

“I am prepared to give Trump the benefit of many doubts.”

It was Thanksgiving weekend 2016, and amid visiting with grandchildren at her lakeside New Hampshire home, Janet Breslin had just found a few quiet moments to reflect on the recent election in an email to Janet Nelson, one of her sorority sisters, in sun-christened California.

The two had met at the University of Southern California in the 1960s when some guys from a nearby town had recently launched the Beach Boys, “The Endless Summer” felt like a neighborhood documentary, and everything was looking up in the Golden State.

One an international relations major, the other studying art, they bonded over building a papier-mâché volcano for sorority pledge week. It was the beginning of a lifelong friendship that would buoy them through personal crisis and political upheaval. They shared similar backgrounds: Each had roots in the Midwest, devout Christian parents, and similar arcs as young mothers. Yet their outlooks diverged dramatically as they settled on separate coasts.

So when the U.S. political scene erupted with the election of Donald Trump as president, the two Janets had much to discuss – and disagree about. Dr. Breslin, a Democrat who had lived through the 1973 military coup in Chile, taught at the National War College, and represented the United States alongside her husband when he was appointed ambassador to Saudi Arabia under President Barack Obama, was not immediately dismissive.

But she had a number of concerns that she laid out for Mrs. Nelson. “I can debate his policy positions ... but the chants and his own style and use of his wealth worry me,” she wrote in an email.

Mrs. Nelson, for her part, supported Mr. Trump in 2016 and still does today. An independent voter and business owner, she admires how Mr. Trump stands up for America internationally and bucks political conventions at home. She also likes that he’s not a career politician like Joe Biden.

“When Trump says he wants to clean up the swamp – I do, too,” she says, though she dislikes the way the president talks and wishes he would be a better role model.

On the eve of arguably one of the most consequential elections in U.S. history, the two Janets tell a story of America in a divided age.

Many people across the country who hold opposing views have found it difficult to preserve their relationships with friends, family, and even spouses. Some have cut off ties with acquaintances altogether. Others have unfriended people on Facebook or reached an uneasy peace by tacitly agreeing not to discuss politics. Forget about holding a thoughtful conversation about issues convulsing the republic.

A 2019 study revealed that fully 20% of Americans have experienced damage to a friendship as a result of political differences – and that’s based on data collected only a few months into President Trump’s administration.

The Janets, however, have navigated more than half a century of friendship as their careers, life experiences, and ZIP codes have caused their political viewpoints to evolve in different directions.

Over that time, the U.S. has seen a dramatic increase in polarization – more than many other major democracies. One 2020 study from Brown University attributes this to partisan cable news outlets and a political realignment over the past 50 years along racial and religious lines, which have resulted not only in greater differences between Democrats and Republicans ideologically but also in terms of identity.

Yet Dr. Breslin and Mrs. Nelson illustrate how two people can withstand the centrifugal pull of politics. Over more than half a dozen lengthy conversations with the Monitor, they offer insight into how they’ve preserved their friendship – and gained a deeper understanding of each other’s political views – even as they still wrestle with key issues and the man up for reelection on Nov. 3. While political disagreements, at times heated, have contributed to Dr. Breslin falling out of touch with other sorority sisters, she and Mrs. Nelson have maintained a strong bond.

“I don’t ever remember Jan and I ever being mad at each other about our different political views,” says Mrs. Nelson.

As the nation goes to the polls during one of the most fractious moments in history, the two Janets offer a template for how a country can disagree civilly.

“A good time to be alive”

Going to the University of Southern California was “like going to Mars” for Mrs. Nelson. Her parents came from Nebraska, where her grandfather was known to wrestle bears when the circus was in town to make an extra $50. In the hardscrabble farming community of Naponee, only one of his children made it past eighth grade – Mrs. Nelson’s father.

Her other grandfather had a stack of National Geographic magazines in his closet and a mind full of poems, which he would recite to little Janet as she followed him around the farm on extended visits. She and her cousins would jump into bins of cool corn kernels on hot days or play in the nearby stockyards and pretend to auction off the littlest kids and herd them into chutes.

Her parents settled in California and started a mobile home business. Their hard work paid off: Mrs. Nelson’s father went on to become one of the biggest West Coast dealers of mobile homes and would come back to visit Naponee in a shiny new Cadillac. But otherwise their life was modest, revolving around their Lutheran community, made up of bedrock people – plumbers, car salesmen, and insurance agents. By the time Mrs. Nelson entered USC, she didn’t know anybody who had been to college but her doctor, her pastor, and teachers in her Lutheran high school.

“I didn’t apply to college; my dad did,” says Mrs. Nelson. “He said, ‘You’re going to go to the best school I can afford.’”

At USC, she would meet another Janet with roots in the Midwest. Dr. Breslin was born in St. Louis, the oldest grandchild of Main Street Republicans. Her mother’s father was a civic booster who, apart from his beloved Oldsmobiles, put his money into supporting local projects like building a baseball field.

Her father’s mother went by the name Honey Bunch. Widowed as a young mother during the Depression, she started a boarding house after her husband died, bringing in enough income to support her four children.

In seventh grade, Dr. Breslin’s parents moved to Gardena, in Southern California, where her parents were active in their local Christian Science church. Her mother worked as a high school math teacher, and her father managed a savings and loan. He was a stalwart Republican. When President Richard Nixon was impeached and forced to resign over Watergate, he went to the airport to welcome him back to California.

She grew up thinking of Democrats as union people – and different from her. Then John F. Kennedy burst onto the national stage. He was “handsome as could be,” and in her eyes represented youth and the future.

“If I could vote, I would vote for Kennedy,” Dr. Breslin recalls telling her mother while watching the Democratic convention in the summer of 1960.

“I felt like we were on a roll,” she says. “We were going to go to the moon. It was a good time to be alive.”

A powerful bond

Dr. Breslin liked Mrs. Nelson the first time they met. She was fun but also sensible. She was creative – something Dr. Breslin admired because she wasn’t particularly creative herself. They quickly bonded and found in each other the sister neither of them had ever had.

After graduating from college, the two took different paths. Mrs. Nelson moved to Colorado to complete her student teaching, and her sorority sister went on to get a Ph.D. in political science at the University of California, Los Angeles. Dr. Breslin then moved to Chile for a year with her husband. They lived through the 1973 military coup orchestrated by Augusto Pinochet that led to the torture, disappearance, and execution of thousands of Chileans over 17 years.

“Rule of law went away. Congress went away. Newspapers closed. The government implemented the use of torture,” says Dr. Breslin, who came away from the experience with an acute sense that liberty is fragile. “Without the constraints of law, the depths of action are almost unlimited.”

Dr. Breslin had a hard time conveying the brutality of what she saw in Chile to people in carefree California when she returned home.

“I felt the same way when I came back from Austria,” says Mrs. Nelson, referring to a University of Vienna program she participated in, during which she lived with an Austrian woman who had been forced to share her one-bedroom home with a Russian military family after World War II. “To have her describe what it was like to be on the other side of the Iron Curtain ... how do you explain that to somebody who is in college in California with the Beach Boys?”

Dr. Breslin decided to get a job on Capitol Hill to help keep America’s democratic system strong. She worked for a series of Democratic senators, focusing in part on a rising issue at the time – immigration.

Back in California, Mrs. Nelson was dealing with the same issue in a different way. She was on the front lines of Hispanic immigration in public schools. On Dr. Breslin’s visits to California, she would ask who would work in the agricultural fields if not immigrants.

But Mrs. Nelson, who taught art and then went on to work in special education after getting a master’s degree, told her friend that many of her low-income students couldn’t get jobs. The entry-level positions were being taken by immigrants who had crossed the border illegally. And families from Mexico and Central America who had gone through the legalization process were adamantly opposed to the surge in illegal immigration.

“In California, we’ve had a huge problem forever, which Jan didn’t really understand. She still thought of California as being like when she was growing up here,” says Mrs. Nelson, who taught at a high school in Westminster where students spoke 27 languages. “But it had started to change. She just didn’t have a clear picture of what we were going through.”

During one memorable lunch, one of their other sorority sisters told Dr. Breslin she was prepared to defend her beach town against the influx of immigrants.

“She sounded like a Bosnian, talking about it. I’m speaking lightly of it, but that’s a powerful feeling,” says Dr. Breslin, who says her time in Saudi Arabia gave her a greater understanding of how powerful culture can be, especially when people feel it’s being invaded. “I stand in respect for how powerful those feelings are. And I didn’t respect it at the time, because I didn’t understand it.”

But even as the two Janets’ political views were moving in different directions, when personal crises struck, they turned to each other. At one point, Dr. Breslin confided in her sorority sister about the dissolution of her marriage, which left her with a baby, a 4-year-old, and a demanding job in a fast-paced and at times unforgiving Washington, D.C.

Mrs. Nelson could relate to her ordeal. Her husband, who had been her high school sweetheart, had come home one day and, as she recalls it, announced, “I don’t want to be a father, and I don’t want to be married, and I don’t want to be here.” He packed a suitcase and left. She says she was totally blindsided.

“So that’s a powerful thing to share with each other,” says Dr. Breslin.

Decades later, their devotion to each other remains strong. “If I have a personal problem, Jan is going to be the first person I’m going to talk to,” says Mrs. Nelson.

Tough conversations

The closest their relationship ever got to a breaking point was over a series of chain letters. Mrs. Nelson would frequently forward to Dr. Breslin emails she got that included false information and breathless assertions in all-caps, setting off a flurry of frank exchanges.

Bill Clinton wants to take away all your guns, claimed one. “I would dutifully do research and go, ‘Janet, President Clinton does not want to take away your guns,’” says Dr. Breslin. “Whatever the rumor was, I would do all this research.”

Another chain message, with the subject line “Good Info,” asked whether a series of statistics were about the NBA or the NFL:

14 have been arrested on drug-related charges; 8 have been arrested for shoplifting; 21 currently are defendants in lawsuits. And 84 have been arrested for drunken driving in the last year. “Can you guess which organization this is?” it asked. “Give up yet? Neither, it’s the 535 members of the United States Congress. The same group of Idiots that crank out hundreds of new laws each year designed to keep the rest of us in line.”

Dr. Breslin’s reply was brief this time. “No no no.” She saw in the emails a troubling pattern of undermining trust in America’s democratic institutions.

Then came the emails claiming that Mr. Obama’s birth certificate from a hospital in Hawaii was inauthentic – a topic Mrs. Nelson took particular interest in since she, too, had been born in Hawaii. Her father had helped recover the bodies of American soldiers after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

“It made me really sad that Jan would believe that,” says Dr. Breslin, who continued to refute such emails. “Jan is a reasonable, thoughtful, smart woman. But whatever I did had no impact. None.”

Mrs. Nelson disagrees, emphasizing how much she valued her friend as a sounding board. “One of the reasons I sent you the chain mails that I was getting,” says Mrs. Nelson in a joint interview, “is because I respect hugely your political knowledge and also to have you see what’s happening with our friendships and the things we’re dealing with on our end of the world.” Mrs. Nelson would sometimes share Dr. Breslin’s responses with mutual friends who had forwarded her the emails.

Indeed, as frustrating as such exchanges have been at times, they have pushed both women to better understand the other’s point of view.

“What I thought about and I’m still thinking about ... is what are those things that were touching something deep in [you], either your experience by teaching in the LA city schools or that you saw culturally happening in Los Angeles that I needed to be more attentive to?” asks Dr. Breslin.

She was gaining a better appreciation for why some people in California were so resentful of the latest surge in immigration. She wasn’t surprised when Mr. Trump made it such a central part of his campaign in 2016. “He has great political instincts,” Dr. Breslin admits.

His tough stance on immigration is one of the things that first resonated with Mrs. Nelson. “When I look at our president and the things that he does – it irritates the heck out of me, but at the same time, I appreciate him being firm in ways that other presidents were lax,” says Mrs. Nelson, who runs an oral hygiene education company, Toothfairy Island, whose materials are used in schools across the U.S. as well as in a number of other countries. “I think we need more firmness.”

At Dr. Breslin’s urging, Mrs. Nelson researched more than two dozen Democratic candidates running for president early in the 2020 campaign to see if she could support any of them. But she found that none was willing to put what she considered meaningful boundaries on abortion, which was a deal breaker for her. As someone who lost two children to miscarriages, she says she would never want any other mother to hurt the way she did, ending up without that child.

“You don’t want anyone else to go through that pain and regret,” says Mrs. Nelson. “Especially when they’re young and they make decisions, they don’t really understand the impact it has on them.”

For Dr. Breslin, who now attends a Lutheran church and chairs her local Democratic committee, the challenges of the Trump era go beyond personality to an erosion of founding principles and shared values. She worries he could destroy the delicate balance of power designed by the framers to prevent tyranny.

“It’s not just President Trump. It’s what he has touched in people that made them abandon the values I thought we were all raised with,” says Dr. Breslin, who describes deep anger and a gradual toughening – on both sides of the aisle. “I think we’re both addicted to it, or stuck. We’re in a rut. A dangerous rut.”

Across the nation, that polarization is not only affecting personal relationships, but also dividing communities and professions, says Dr. Breslin. And she feels that President Trump is exacerbating those divisions by caricaturing people like her.

“He’s telling people ... [Janet] hates this, and she’s against this, and she’s a lefty, and all these things – and I feel like saying, ‘No I’m not,’” says Dr. Breslin. “I don’t hate [Mr. Trump] at all, but I really, truly believe he feels it’s useful to hate me.”

Mrs. Nelson, for her part, has refused to play into such rhetoric. “What keeps me going and being hopeful always is I believe that God is in charge,” she says.

Even so, neither of them plans to stop sending missives about policies and politicians they see differently.

“Jan and I are some of the few people who kind of keep working this. A lot of people are like – forget it,” says Dr. Breslin. “We keep trying to convince each other.”

Republicans have dominated redistricting. Here’s why that could change.

State politics matter a lot to voters’ lives, from new laws to changed political districts. While “down-ballot” races tend to get little attention, this year could see a significant rebalancing of power.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Al Hagan knows that despite “a real shift in who lives here,” coastal Georgia remains fundamentally a conservative region. “So you may find it curious that I’m an African American and a Democrat running for sheriff.”

Yet times are changing. A competitive race here in Richmond Hill for a Georgia House seat (and in the sheriff’s race) signals a possible realignment that has raised Democrats’ hopes of winning control of a legislative chamber in today’s election. While it may be a long shot in Georgia, party control of state legislative chambers could flip toward Democrats in a number of states, from Arizona and Texas to Michigan and Pennsylvania.

The result may be more states under split political control, exerting a tug toward middle ground on both state policymaking and redistricting. Back in 2010, by contrast, Republicans won state-level races that allowed them to dominate the once-in-a-decade process of redrawing political maps based on census data.

Amid the flux here in Georgia, Mr. Hagan sees hope. Residents’ “values aren’t really that different,” he says. “This is a great community, but we can make it even better together, and I want to be part of that.”

Republicans have dominated redistricting. Here’s why that could change.

Georgia residents Larry and Helene Hunt – an African American couple who vote straight-ticket Democrat – have figured out over the years that “change comes slow here in the South,” as Ms. Hunt says.

Their 14-year tenure in Richmond Hill, a suburb of Savannah, exactly matches the years that Republicans have had a lock-tight grip on state politics. One result has been the gerrymandering of their state legislative district into a solid GOP stronghold.

Such partisan mapmaking has left thousands of Coastal Empire residents feeling little reason to vote or otherwise participate in democracy, Ms. Hunt says.

But that map is fraying. Demographics have changed as new people move to Georgia, drawn in part by a strong economy and good schools. And now, as a pandemic and political tumult drive huge numbers of voters to the polls, she says her feeling of democratic detachment “is disappearing with this election.”

Today, a political neophyte named Marcus Thompson – a 40-something Black salesman – is running neck and neck with Ron Stephens, a white Republican who is a pharmacist and seven-term incumbent.

The fraying of this Republican-drawn district on the Ogeechee River hints at the possibility of a tectonic shift in this year’s election: Party control of state legislative chambers could flip in a number of states, from Arizona and Texas to Michigan and Pennsylvania.

In many cases, inroads by Democrats could leave more states under split political control, exerting a tug toward middle ground on both state policymaking and redistricting – the once-in-a-decade redrawing of political maps using updated census data. Knocking Republicans out of power in Georgia’s House looks difficult, but it’s a possibility this year, when Democrats have high hopes of cracking Republican dominance in state-level politics.

“What was safe in 2010 looks a lot different in so many of these states now,” says Joshua Zingher, an Old Dominion University political scientist who studies the nationalization of state politics.

Though little noticed beneath the drama of contests for the presidency and Congress, state-level shifts could influence national politics for years to come. The post-census redistricting could also provide a lens for Americans to see how their differences and similarities shape a nation, some experts say.

“A tremendous amount [of this election] hinges on redistricting, which becomes a great window into the sociological, political, and cultural dynamics in different parts of the country,” says Rick Pildes, author of “The Law of Democracy.” “You may see class differences that emerge in different communities even though they somehow are largely the same when you see how they vote. You learn things like where are white voters more or less willing to support minority candidates.”

A shifting battleground

With more than two-thirds of state legislative seats across the U.S. in play, and polls suggesting the possibility of a “blue wave” outcome, Democrats could crack at least some of the 22 Republican trifectas. (Democrats have full control of the governorships and legislatures in 15 states, while the rest have split control.)

Both of Georgia’s chambers are such battlegrounds.

To be sure, the Georgia political landscape is littered with the shattered hopes of Democrats. Though 10% of Georgians are foreign-born, 32% are Black, and 60% live in cities, statewide offices are all held by white, often rural Republicans, all but one male. The party has largely moderated its policy agenda, with prescriptions on such traditionally liberal issues as early childhood education, state-funded college scholarships, and criminal justice reform.

Bill Benson, a prison guard, says that too many Georgians believe that Democrats at the national level “have gone crazy” for candidates like Mr. Thompson to prevail. “History tells you that their values just don’t work for voters here,” says Mr. Benson, who is white.

But like other states, Georgia is changing. Its economy has turned from heavy on trade and agriculture toward service industries like filmmaking.

And when Georgia last supported a Democrat for president – Bill Clinton in 1992 – about 77% of voters were white. By the time of a closely contested governor’s race in 2018, that number had dwindled to 60%. That’s when a state representative with a liberal streak, a Black lawyer named Stacey Abrams, came within 55,000 votes of beating Brian Kemp, who as then-secretary of state oversaw his own election.

Here in Richmond Hill, a Democratic statehouse candidate got only 40% of the vote in 2012. Two cycles went by when the party didn’t bother putting up a candidate. But then in 2018, the party’s candidate notched 48%.

With Georgia’s electoral votes and down-ballot contests at stake, Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden spoke last week in Warm Springs, the Georgia community that Franklin Delano Roosevelt used as a “Little White House” retreat.

“For the most part, state legislative races are still about national political winds, and obviously the political winds are bad for the Republicans at the moment,” says Matt Grossman, author of “Red State Blues: How the Conservative Revolution Stalled in the States.”

One dynamic may be salient in this pandemic year, he says: “People want small government until they see what that entails. They don’t like less health care, less education, less social welfare policy. They don’t want less environmental regulation.”

Remaking the map

While some states now have frameworks designed to prevent partisan gerrymandering, 35 states let their legislatures draw districting maps.

After sweeping into control of multiple legislative chambers in the 2010 midterm election, Republicans drew on technology to divide up voters with surgical precision, such as by packing Black – and presumably Democratic – voters together.

In 2011, Republicans drew 55% of congressional districts, compared to the Democrats’ 10%. (The rest were drawn with split control of the process or by bipartisan commissions.)

But even as a landslide election win can benefit one party, it can also underscore the pitfalls of gerrymandering.

“One thing to keep in mind with the gerrymander, what you’re trying to do, you want to win a large number of seats by a relatively narrow margin of votes,” says Mr. Zingher. “You want to spread your support around in a way that’s efficient by packing Democrats into majority-minority districts in the urban core and win everything else. ... [But] if you get a wave direction cutting against you then these districts you were winning by narrow margins, you may lose all of them.”

It remains far from certain that a blue wave will crest in Georgia’s local elections this year. Al Hagan knows that despite “a real shift in who lives here,” coastal Georgia remains fundamentally a conservative region, cemented by church and Republican politics. “So you may find it curious that I’m an African American and a Democrat running for sheriff.”

The owner of a successful polygraph testing firm, Mr. Hagan is running on a simple message of professionalism and leading the Bryan County department through much-needed changes, including adding equipment – like computers. “They’re still using paper and pen down there,” he says.

But that he and Mr. Thompson are running competitively here suggests to him a realignment that could alter not just election maps but also the shape and feel of communities.

Among residents in this area, “our values aren’t really that different,” Mr. Hagan says. “I love God and a strong economy. I haven’t even asked what the sheriff makes, because it doesn’t matter. This is a great community, but we can make it even better together, and I want to be part of that. You can’t go wrong doing what’s right.”

Online misinformation is rampant. Four tips on stopping it.

Nobody likes being wrong. But what if corrections came from someone you trust? Experts urge Americans to fight misinformation as a shared responsibility.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

If there’s anything that everyone across the political spectrum can agree on, it’s that misinformation is widespread. It’s easy to feel powerless, but there are ways that ordinary people can play a role in the solution.

As tech companies and researchers continue working to thwart a range of “information disorder,” experts say that ordinary citizens can also play important roles in combating online untruths. Consider it a cyber civic duty.

First, it’s important to make sure that you have your own facts straight. Second, act fast. Research suggests that we’re more prone to believe information – even if false – that we’ve encountered more than once. Third, think about the impacts of reaching out publicly versus privately.

When countering misinformation, it helps to offer credible sources, says Kathleen Carley, director of the Center for Informed Democracy & Social Cybersecurity at Carnegie Mellon University. “As opposed to just pointing out that something is wrong, provide an alternative,” she says.

Finally, remember our social media posts are tied to our identities. That means attacking someone’s content can be perceived as a personal attack, says media scholar Claire Wardle.

It’s not about saying “you’re wrong,” she says. “It’s about having empathy for why somebody might believe something.”

Online misinformation is rampant. Four tips on stopping it.

This spring, Amber pored over Facebook posts as a self-appointed fact checker. She’d seen how the president’s remarks at an April news briefing became mangled through memes.

No, Donald Trump didn’t urge Americans to ward off the coronavirus by drinking bleach. (Fact-checks here.) But confusion over his speech spiraled out of context across websites, social media, and late-night comedy.

Amber, a human resources specialist from Crystal River, Florida, says she calmly commented on friends’ posts with a link to a video of the event for reference.

“I find that helps me not create an enemy with them,” says Amber, who asked to omit her last name because of her employer’s restrictions on speaking to the press. If she insults someone’s intelligence, she adds, “they’re just going to discount everything I said and also try to insult me back.”

About two-thirds of U.S. adults got their news from social media in 2018. Americans are more likely to share misinformation (inaccurate content shared unknowingly), rather than disinformation (inaccurate content shared to deceive), experts say. Both can deepen divisions in an already polarized society, and – at worst – inspire violence.

As tech companies and researchers continue working to thwart a range of “information disorder,” experts say citizens like Amber can also play important roles in combating misinformation – not just as critically minded consumers, but as concerned family and friends. Consider it a cyber civic duty.

“They can act as trusted messengers,” says Emma Margolin, senior research analyst at Data & Society.

Postelection, media scholar Claire Wardle hopes to see more emphasis on society-based strategies.

“Fundamentally, if none of us shared any of this stuff, then we wouldn’t have a problem,” says Dr. Wardle, co-founder and U.S. director of First Draft News. She notes that disinformation actors are powerless without us sharing their content: “We have to be part of the solution. We just haven’t had these conversations enough.”

PEN America, a nonprofit that advocates for writers and human rights, is among a growing group of organizations offering media literacy training. Its tip sheet on how to talk to acquaintances constructively about misinformation came in response to participants’ demand, says Nora Benavidez, director of PEN America’s U.S. Free Expression Programs.

“People are so hungry for permission to be empathetic,” says Ms. Benavidez, who wrote the tip sheet.

Of course, correcting your leftist ex or right-wing uncle can be awkward at best, and not every attempt will be a win. Here are some suggestions to start.

Fact-check first.

Is the post about that candidate actually false? Or does flattering coverage of them simply make your blood boil? Before confronting others, make sure your facts are straight – no matter your social media savvy.

“We need to [debunk] the myth that experts are never going to be victims, or believe in false or misleading content, because I absolutely have,” says Ms. Benavidez at PEN America. “That’s how insidious and potent disinformation is.”

Beware of partisan websites posing as unbiased news sources, as well as misleading headlines. Beyond sleuthing out the source, see if reputable fact-check websites have already verified the claim, like the Poynter Institute’s PolitiFact, The Washington Post Fact Checker, Snopes, or FactCheck.org. A simple reverse image search on Google may help verify images by determining their online origins.

Alert the platform early.

Correct misinformation and disinformation as early as possible. Experts encourage users to flag troubling posts on social media sites, which may remove the content. Again, the earlier the better – before the masses have been exposed to it, says Ms. Margolin at Data & Society.

If a platform removes flagged content after it goes viral, the act of removal could backfire as it “becomes its own story,” she adds. Users may accuse the platform of bias, or censorship of certain worldviews.

The “illusory truth effect” underscores the need to act fast: We’re more prone to believe information – even if false – that we’ve encountered more than once.

The effect holds true even when prior knowledge contradicts what we’re reading, psychologist Lisa Fazio’s research suggests. This impacts our experience online, where content proliferates.

“We’re seeing [misinformation] multiple times, and if we don’t do anything to stop it, that repetition will likely increase our belief,” says Dr. Fazio, assistant professor of psychology at Vanderbilt University.

Public or private outreach? Consider context.

Whether to confront your doom-scrolling Facebook friend publicly or privately about his problematic post requires some thought. Research suggests that observing others’ public correction can reduce misperceptions.

Yet due to the way social media algorithms work, publicly engaging with a post can actually amplify its false or misleading content. Public call-outs may also be seen as shaming. As PEN America’s tip sheet notes: “If something was just posted, you might try sending a private note politely pointing out that it’s incorrect.”

If you’re craving technique, consider the “truth sandwich” from linguist George Lakoff. Lead with the truth, point out the lie, then conclude with the truth, so that correct information is most memorable.

It also helps to offer credible sources, says Kathleen Carley, director of the Center for Informed Democracy & Social Cybersecurity at Carnegie Mellon University. “As opposed to just pointing out that something is wrong, provide an alternative,” she says.

Lead with empathy.

Our social media posts are tied to our identities. That means attacking someone’s content can be perceived as a personal attack, says Dr. Wardle of First Draft News. That could make them double down.

“It’s about having empathy for why somebody might believe something … rather than saying ‘you’re wrong,’” says Dr. Wardle.

In lieu of lecturing, empathetic outreach could focus on a user’s online actions or behaviors rather than their content. Dr. Wardle suggests invoking a shared commitment to a healthier democracy, such as, “I’m worried that maybe this is a deliberate tactic to try and make us angry, or to divide us, or to confuse us.”

Correcting false content online is nonpartisan action. It requires everyone’s vigilance, as we can all fall prey to our emotions, confirmation bias, and other mental shortcuts. As Dr. Fazio says, “It’s not a Republican problem, it’s not a Democrat problem ... it affects all of us.”

Hone your verification skills with resources from First Draft News, MediaWise, the Shorenstein Center, and PEN America’s online training.

Corporations pledge to fight racial inequality. Will it work?

In the wake of protests against racial injustice, many businesses are setting ambitious diversity goals in hiring and investment. The hope of progress is real, even if it’s at best a partial solution.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

From big banks to Starbucks, American corporations are rolling out initiatives to address racial inequality. JPMorgan Chase has a new $30 billion five-year plan to fund things like affordable housing. IBM has announced a quantum computing outreach to historically Black colleges and universities.

Advocates for greater equity welcome the attention, while waiting to see the results. One telltale sign, they say, is how companies address the racial gaps when it comes to their own workforce and contracting. One study finds Black and Latino Americans together hold only 7% of mid-level management positions in the financial industry, even though they make up 13% and 18% of the population, respectively.

The stakes are high for the whole economy. Citibank calculates that if the U.S. could somehow close the racial economic gaps, the U.S. economy would add $5 trillion of economic activity.

“I was ecstatic when I saw the announcement from Chase,” says Gary Cunningham, who heads Prosperity Now, a nonprofit aiming to build wealth for low-income people. But he adds that government helped build the middle class, especially the white middle class, with programs like home loan guarantees and the GI Bill. “There has to be both a public and private approach,” he says.

Corporations pledge to fight racial inequality. Will it work?

The online announcement had the usual lineup. Mayors and educators spoke about the importance of career readiness grants for Black and Latino residents in their cities. What was unusual about Tuesday’s event was the host, which wasn’t a foundation or the federal government.

It was JPMorgan Chase, America’s largest bank.

For several minutes on-screen, CEO Jamie Dimon talked about the need to address the nation’s long-term racial inequality through better career-prep in schools. The bank’s philanthropic arm is committing $35 million to a five-city, five-year effort to improve career readiness in underserved communities, part of a much larger corporate effort to tackle racial inequality. “To fix the problem, you’ve got to acknowledge it,” said Mr. Dimon, who is one of the many white Fortune 500 CEOs deploring America’s persistent racism.

Ever since May, when the death of George Floyd drew national attention to violence by police, corporate America has been talking about narrowing racial inequality. Now, spurred also perhaps by evidence that the pandemic has hit Black and Latino Americans especially hard, they’re doing something about it.

In the past two months alone:

•JPMorgan Chase announced a wide-ranging $30 billion five-year plan that spans from building affordable housing and improving access to loans to funding community development groups. Rival Bank of America has issued a $2 billion “equality progress sustainability bond” – the first of its kind – aimed at advancing racial equality, economic opportunity, and environmental sustainability. Citi has announced its own $1 billion investment to combat racial inequality.

•Coffee chain Starbucks announced steps – including a mentorship program for senior executives – aimed at achieving 30% people of color at all corporate levels by 2025.

•IBM announced a research initiative to create a diverse workforce in quantum computing by offering access to its superfast computers to Howard University and a dozen other historically Black colleges and universities.

Even the Federal Reserve has launched a series of online events this month on structural racism and inequality. In the wake of Fed research showing that few Black homeowners had refinanced their mortgages to lower rates, the Fed has resolved it needs to get the word out to all communities.

Citibank calculates that if the U.S. could somehow close the racial gaps in wages, housing, higher education access, and business investment, the economy would add $5 trillion of economic activity and a third of a percentage point to annual growth over the next five years.

While it’s far too early to assess whether these initiatives can achieve that, their size and the fact that corporate chieftains are saying, sometimes for the first time, that racism in America is systemic are seen by many as a step forward.

“I was ecstatic when I saw the announcement from Chase,” says Gary Cunningham, president and CEO of Prosperity Now, a nonprofit aiming to build wealth for low-income people that received funding from Chase.

But big efforts that helped build the middle class, especially the white middle class, such as federal guaranteed home loans during the Great Depression and the GI Bill after World War II, were government efforts, he points out. “There has to be both a public and private approach.”

What will success look like?

JPMorgan Chase “stands out to me in being a little ahead of the game,” compared with other firms, says Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, chief of race, wealth, and community at the National Community Reinvestment Coalition in Washington. But the proof will come when corporations begin to reflect the nation’s diversity in their own workforces and contracts to minority-owned firms.

“It would be a serious step forward if major corporations start having procurement contracts with Black businesses – getting away from [a token] 1%, 2% to 10%” of business to outside contractors, Mr. Asante-Muhammad says.

Best Buy has committed to find and nurture Black- and minority-owned manufacturers of products that it would sell. In June, General Motors CEO Mary Barra created a financial inclusion board of company officials and outsiders with the goal, she said, of “making GM the most inclusive company in the world.”

Another encouraging sign is that many of these companies are building on diversity initiatives already underway. In June, AT&T announced it was nearly 90% toward its commitment to spend $3 billion with U.S. Black-owned suppliers by the end of this year.

The flip side is that, for all the recent commitments, racial inequities in corporate hiring have been deep and persistent. The National Community Reinvestment Coalition and Beneficial State Foundation found that Black and Latino people together hold only 7% of mid-level management positions in the financial industry, even though they make up 13% and 18% of the population, respectively. At senior level positions, they hold only 3% and 4%, respectively.

In some areas, representation for employees of color has actually gone down. In the hotel and lodging industry, for example, white workers held 71% of the top management positions in 2007, according to an NAACP report last year. By 2015, that share had risen to 81%.

That was before the pandemic, which decimated the industry and has hit Black and Latino Americans particularly hard. Besides a COVID-19 fatality rate that’s twice as high for Black Americans as for white Americans, the economic downturn has shut down thousands of small businesses and caused unemployment to soar. In February, the Black unemployment rate stood less than 3 percentage points above the rate for white Americans; by September, the gap had grown to 5 percentage points.

The quest for effective solutions

The challenge is multifaceted in part because racial disparity is spread across the economic spectrum: from unemployment and wealth to housing and even venture capital. A report from Crunchbase this month found that Black- and Latino-owned firms got only 2.4% of venture funding even though they make up 32% of the population.

Not everyone is optimistic that the current rush of corporate activity will end well.

“There are a number of corporations as well as philanthropic entities that are facing enormous pressure to mobilize their resources” on behalf of Black Americans, says Ian Rowe, resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and cofounder of Vertex Partnership Academies, which will be opening new charter schools in the largely Black and Hispanic south Bronx in 2022.

Like many Black Americans, he says that racism does still create disadvantages for some people of color, even as many have made enormous progress by embracing the ideals of family, faith, hard work, and entrepreneurship. But as society tries to address those disadvantages, he says a vital step is to nurture the personal agency of Black Americans themselves through a success sequence that starts with education and job skills.

If corporations send a signal that there’s nothing a Black individual can do to improve his or her lot, they will undercut racial dignity and contradict the companies’ own values, such as merit-based success, Mr. Rowe says. He deplores as a double standard the way one small bicycle company briefly offered Black customers a discount that wasn’t available to other customers. (The firm is currently rethinking its approach to its “reparations” program.) By contrast, he applauds companies like Netflix, which is shifting as much as $100 million of its cash to Black-owned banks and community lending organizations, because those lenders will evaluate entrepreneurs on the strength of their business plan rather than the color of their skin

Corporate initiatives will work “only if it’s in line with their core values,” Mr. Rowe says. “Otherwise, they won’t endure.”

Indeed, efforts to help entrepreneurs of color hint at the complexity of solutions.

“Banks today generally want to make loans of $1 million or more and they generally want to lend to entrepreneurs that have three years of audited financials,” says Michael Schlein, president and CEO of Accion, a nonprofit that lends to small businesses in developing nations as well as in the United States. “Most small businesses don’t have three years of audited financials and don’t need $1 million. They need $40,000.”

He applauds businesses that are putting money into minority-owned banks and community-based lenders who specialize in these small loans. Yet many times these loans aren’t profitable, Mr. Schlein adds.

Whereas Accion can lend sustainably to entrepreneurs with no credit scores in other nations, its U.S. arm struggles because potential clients walk in with bad credit scores, which muddies the outlook on the viability of their business.

“We work weeks or months to help entrepreneurs to separate personal and business” debt, he adds, which raises costs. He’s hopeful that by scaling up the business and using the latest financial technologies, Accion can eventually make such U.S. lending not only profitable but also attractive to commercial lenders.

Looking at the broader array of corporate efforts, Mr. Dimon of Chase is also upbeat: “You have 200 of the biggest companies in America pretty much devoted to this issue. ... [Then] if you get the local civic society, the community colleges, the governor, the mayor working together, we will win.”

Outsiders turned icons, South Africa’s jacarandas spring into bloom

With so many of us cooped up at home, this year can feel frozen in time. But South Africa’s iconic jacarandas are still blooming – a reminder that the world keeps turning

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

As the Southern Hemisphere’s spring withers into summer, South African students have a saying: If the jacaranda trees are already blooming and you haven’t started studying, sorry, but you’re not going to pass.

For a few weeks each October and November, the trees burst into a spectacular display. Their raucous purple blooms have been the backdrop to much more than university exams. In 2015, student protesters marched past them as they demanded a halt to rising tuition costs – a movement that turned into a national reckoning. In 1994, President Nelson Mandela invoked them in his first inauguration speech. And the trees’ own history speaks to the country’s colonial past, as well as its continued struggle with inequality.

But in 2020, for many, the jacarandas’ symbolism has also taken a new form. They’ve become a reminder that nature, in fact, trudges on, even if the human world often feels frozen in time.

“They show that everything has a season,” says Laurice Taitz-Buntman, the editor of Johannesburg In Your Pocket, a popular events guide that runs an annual jacaranda photo competition. “They were here in 2019, and they’ll be here again in 2021.”

Outsiders turned icons, South Africa’s jacarandas spring into bloom

One of the first years that I watched the jacarandas bloom in Johannesburg, their arrival coincided with a revolution.

It was October 2015, and as the lanky trees burst into a riot of lilac blooms, student demonstrators shut down the campus of the city’s major university, known as Wits, demanding a halt to the rapidly rising cost of tuition.

Within days, their movement had grown from the cause of a few thousand college students into a kind of national reckoning. It had been a generation since the end of apartheid, so why, the protesters and their supporters demanded to know, had South Africa only gotten more unequal?

A few days later, every major university in the country had been shut down. And on a 90-degree morning the next week, I followed thousands of young activists and their supporters as they wound their way through Pretoria’s wide, jacaranda-lined boulevards to the Union Buildings, the office of South Africa’s president. They were there to ask that he halt tuition increases nationwide. And he did.

Looking at my photographs, I couldn’t help but notice how many were set against a backdrop of raucous purples. A woman in round sunglasses in front a jacaranda tree at Wits holding a sign that said “WE WERE SOLD OUT.” Another young woman in Pretoria, the jacarandas in the distance smudged by dust and tear gas. “Sorry for the inconvenience,” her poster read. “We are trying to change the world.”

Jacarandas have always made for good symbolism. Their blooming is spectacular and brief. Their flowers last only a few weeks, as Southern Hemisphere spring withers into summer and the year speeds toward its end. In much of eastern and southern Africa, for this reason, they’re seared in the minds of students as a marker that exams are coming. As the urban legend in South Africa goes, if the jacarandas are blooming and you haven’t started studying, sorry, but you’re not going to pass.

In 2020, for many, the jacarandas’ symbolism has also taken a new form. They’ve become a reminder that in a year that often feels frozen in time, the natural world, in fact, trudges on. “They show that everything has a season,” says Laurice Taitz-Buntman, the editor of Johannesburg In Your Pocket, a popular events guide that runs an annual jacaranda photo competition. “They were here in 2019, and they’ll be here again in 2021.”

But like the British settlers who first planted them across their African colonial empire, jacaranda trees are also outsiders, and frankly, not always welcome ones. The bulk of South Africa’s jacarandas were imported from South America around the turn of the 20th century.

They are “reflective of a history of colonialism and apartheid,” when foreign trees – like foreign people – were considered superior here, says Adelaide Chokoe, an arboriculturist at Johannesburg City Parks and Zoo. In the early 2000s, the South African government banned the planting of new jacarandas in its cities altogether, warning that they were an invasive species that crowded out local flora.

And access to trees itself has long been a matter of social justice here. Johannesburg’s formerly white suburbs are so flush with greenery that the city has often dubbed itself the world’s “largest man-made urban forest.” (It’s a contestable distinction, experts say, but even still, the city is impressively verdant.) In October and November, the green canopies in those parts of town are lit up with shocks of purple as the jacarandas flower.

But travel to the Black townships that ring the city, and to which the majority of its population was once confined, and you will find few trees of any kind. Ms. Chokoe, for instance, grew up near Pretoria, a city with more than 50,000 jacaranda trees. But she rarely saw them, she says, because “in apartheid, tree planting was only prioritized in white suburbs.” When she became a scientist herself, that fact never left her.

“When you live with that difference, when you see who has parks and green space and access to trees, and who doesn’t, you say, ‘I want to be part of the process of changing this,’” she says.

In 2014, South Africa reversed its earlier stance on planting jacarandas. As far as foreign trees went, they were low maintenance and relatively benign (as long as you didn’t grow them too close to a body of water). In summer, their long branches provide shade; in winter, they let light filter through.

“I have no hesitation in saying that each one of us is intimately attached to the soil of this beautiful country as are the famous jacaranda trees,” Nelson Mandela said in his inauguration speech as South African president in 1994.

Never mind that he was technically talking about a tree from someplace else – it had already come, in its own way, to belong.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

An election that fits the American story

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Americans have just endured the longest presidential race in history and might welcome a pause to put this chapter of their story as a people into larger context. The American story, writes historian Walter McDougall, has always been “chock-full of cruelty and love, hypocrisy and faith, cowardice and courage, plus no small measure of tongue-in-cheek humor.” By nature, this society is restless, always reinventing and rejuvenating itself.

Much of the world has awaited this election and the change it might bring. Yet change has already come. One stirring in the 2020 election began seven years ago. On July 13, 2013, a self-appointed security guard who shot a Florida teenager named Trayvon Martin was acquitted. That prompted Alicia Garza, a community organizer, to tap out these words on Facebook: “Black people. I love you. I love us. Our lives matter.” Her post galvanized a movement that has broken through America’s long stalemate over racism.

For a nation conceived to set free the human spirit, the pursuit of new national narratives endures. The pursuit requires equanimity, dignity, and grace, which are the traits equally necessary for a restless people reimagining themselves.

An election that fits the American story

Americans have just endured the longest presidential race in history. It began 1,386 days ago when President Donald Trump filed for reelection a few hours after taking the oath of office. He was later joined by three more Republicans and 28 Democrats – the largest and most diverse field of candidates ever. Then a pandemic disrupted the campaign and led to nearly 100 million voters casting early ballots. After all of that, Americans might welcome a pause to put this chapter of their story as a people into larger context.

The American story, writes historian Walter McDougall, has always been “chock-full of cruelty and love, hypocrisy and faith, cowardice and courage, plus no small measure of tongue-in-cheek humor.” By nature, this society is restless, always reinventing and rejuvenating itself.

Much of the world has awaited this election and the change it might bring. Yet change has already come. One stirring in the 2020 election began seven years ago. On July 13, 2013, a self-appointed security guard who shot a Florida teenager named Trayvon Martin was acquitted. That prompted Alicia Garza, a community organizer in Oakland, California, to tap out these words on Facebook: “Black people. I love you. I love us. Our lives matter.” Her post galvanized a movement that has broken through America’s long stalemate over racism.

Critics of Black Lives Matter see its desire for police reform as a call for anarchy. Philadelphia 76ers basketball coach Doc Rivers captured the mood of the Black-led movement differently: “It’s amazing why we keep loving this country, and this country does not love us back.”

Another reinvention happened in the South. For over a century, the region justified Confederate symbols as benign tributes to a tradition and culture. This year, that anodyne narrative collapsed in the face of sustained protests for racial equality. Statues fell. Mississippi came up with designs for a new flag celebrating unity over division.

Other ways to interpret this moment are in quieter places. Over the past decade, as the social justice movement gathered momentum, a new generation of classically trained musicians has been at work reclaiming the buried traditions of Black string-band music. That terrain is no less problematic. Minstrel music is the root of so much of American performative art, but it is also a deep reservoir of racism. White performers turned the music of enslaved people into a black-faced vaudeville of ridicule. Rescuing that music has been a project of both joy and pain.

As if to emphasize the common cause between the marches and the music, the Smithsonian re-released an album last month by Leyla McCalla. The young singer of Haitian descent has interpreted the poetry of Langston Hughes. With banjo in hand she sings, “My life ain’t nothin’ / But a lot o’ Gawd-knows what / Just one thing after ’nother / Added to de trouble that I got.” The music, she told Time, “is a chance to tell stories that have not been talked about enough.”

After the 2016 election, satirist Jon Stewart noted that the United States is still “the same country, with all its grace and flaws and volatility and insecurity and strength and resilience.” That is still true. For a nation conceived to set free the human spirit – not just born of revolution, Professor McDougall argues, but as a revolution in itself – the pursuit of new national narratives endures. The pursuit requires equanimity, dignity, and grace, which are the traits equally necessary for a restless people reimagining themselves.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

A path to postelection harmony

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Ingrid Peschke

In the U.S. presidential election, only one candidate wins, and there will always be people unhappy with the outcome. But letting Christly love light our path empowers us to feel the divine peace that frees us from fear and disdain.

A path to postelection harmony

The U.S. presidential election, which concludes today, has been described as one of the most contentious and crucial elections in the country’s modern history. Many voters on both sides feel that if their candidate doesn’t win, the country will be in grave trouble. Yet in the end only one candidate can be voted into office.

So how do we settle our thought, and know that regardless of the outcome of the election, we can move forward in a way that forwards peace and harmony?

I’ve found that prayer provides more help with this than anything else possibly can. One idea that’s inspired me recently is in the Bible, when the prophet Isaiah foretold the coming of the Christ. Isaiah uses the term “mine elect” in describing God’s Son, Jesus Christ: “Behold my servant, whom I uphold; mine elect, in whom my soul delighteth; I have put my spirit upon him” (Isaiah 42:1).

Jesus brought a new law, a new covenant, to the people. Paramount to that law is loving God and loving one’s neighbor without exception. The Apostle Paul would later write of being made free by “the law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus” (Romans 8:2).

This divine law that Paul speaks of offers the greatest freedom of all: the realization that there is nothing more powerful than God, divine Love itself. This includes freedom from giving in to fear or hateful thoughts about others.

At one point during the election campaign, a friend expressed her deep concern over the state of politics as well as her opinionated views about the candidates, which differed from mine. Oh, I wanted to “correct” her! So much so, that I found myself thinking that I might not even want to be her friend anymore after what she had shared. I was startled at this thought that came to me despite this friend’s many exemplary qualities. I could feel disdain for her brewing in my thought.

That wasn’t how I wanted to consider my neighbor, and certainly not over a polarized election! So I held my tongue and mentally reached out in prayer to find an idea that would give me peace.

What came to me, quite powerfully, was along these lines: This is about loving your neighbor in ways you never have before. This is about looking past differences to see more of the spiritual reality: your unchangeable unity as children of God. After all, if you love God, who is Love, you must love your neighbor. We’re all created to express God’s love and goodness.

This was just the impetus I needed to move forward with the higher purpose of serving God first. The disdain lifted, I felt at peace, and I’m so grateful that our friendship continues.

The inspiration I received from my prayers that day, from appealing to God as Love itself, wasn’t just instructive in that moment with my friend. It continues to help me now as we head into a postelection season. No matter which candidate we supported, and no matter what testing times might lie ahead, we can make it our goal to bear witness to the higher law of God in action, the law of goodness and peace that Jesus taught and demonstrated. I’ve experienced more than once how being willing to let the love of Christ impel our actions and words dissipates division and discord.

Responding to conflict among church members in Greece, Paul once wrote: “I appeal to you, brothers and sisters, in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that all of you agree with one another in what you say and that there be no divisions among you, but that you be perfectly united in mind and thought. ... One of you says, ‘I follow Paul’; another, ‘I follow Apollos’; another, ‘I follow Cephas’; still another, ‘I follow Christ.’ Is Christ divided?” (I Corinthians 1:10, 12, 13, New International Version).

If we feel our primary allegiance is to a particular person or political party, we will always be divided. Our task is to follow God and strive to emulate Christ Jesus’ model in our lives. You could say we’ve each been “elected” and specially appointed to love God and our neighbor more than our firmly held opinions. As we step up to fill that spiritual post, we do our part to contribute to a more righteous government and increased harmony in our country and our world.

As Jesus reassured us: “Peace I leave with you, my peace I give unto you: not as the world giveth, give I unto you. Let not your heart be troubled, neither let it be afraid” (John 14:27).

Some more great ideas! To read or share an article for teenagers on overcoming anxiety titled “A permanent healing of panic attacks,” please click through to the TeenConnect section of www.JSH-Online.com. There is no paywall for this content.

A message of love

We voted

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us. Please come back tomorrow for our postelection coverage, including a look at Americans’ trust in the process.

We’ll also have additional coverage of breaking news on our First Look page.