- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- ‘Our last, best chance’ to heal Senate, says key Biden ally

- ‘We have been re-written into history’: Tribes cheer Interior secretary pick

- Why India’s protesting farmers aren’t going home

- ‘Good morning, sweet girl’: A day in the life of an online teacher

- From ‘American Utopia’ to ‘Ma Rainey,’ the 10 best films of 2020

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

For 2021: Moving past blame, honoring perspectives

After today, sunlight starts to linger longer in the Northern Hemisphere.

It may be hard to find solace in more light. New threats flare around global public health, the U.S. political transition, cybersecurity. There’s blame and broken discourse.

It can be tempting to assemble facts and just keep slinging them.

“But facts aren’t reliably corrective in and of themselves,” writes Whitney Phillips, who teaches media and culture at Syracuse University, “especially when believers occupy a totally different ideological paradigm as the debunker.”

Addressing journalists for the media-watcher Nieman Lab, Dr. Phillips calls for coming to terms through listening, not just outputting. It’s a constructive formula for shifting thought.

“We develop our beliefs through our feelings, not our brains,” writes Amanda Abrams in Yes! magazine. “And that’s how we’re changed as well: by connecting with others and having an emotional experience.” Ways to get there include wider contact, earned trust, and storytelling.

Can this thinking trickle down? Politico’s Tim Alberta got 20 Americans to describe their thinking about the election. This isn’t dish-and-dash vox pop. Built from recurring chats, his story is an exploration of complexity over caricature. It may even help show a way out of the darkness.

“We just need leaders with the courage to honestly listen to all sides and try to lead a unified country, rather than push an agenda supported by less than half the country,” a California man told Mr. Alberta. “I do have confidence that we can work it out.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Q&A

‘Our last, best chance’ to heal Senate, says key Biden ally

President-elect Joe Biden has made cross-aisle outreach a core competency. Our writer spoke with the senator and fellow Democrat most often hailed as his special liaison in that work.

As Congress moves forward on a $900 billion stimulus deal, announced Sunday night, some see glimmers of hope for bipartisanship in the coming term. President-elect Joe Biden lays great worth on his relationships with members of both parties on the Hill, and hopes that will help pave the way to agreements. Will his ties and experience make a difference?

The Monitor recently talked about all this with Sen. Chris Coons, the Democrat from Delaware who holds President-elect Biden’s former seat. The two men are close, and Senator Coons has already emerged as one of the incoming president’s key point people in Congress – a conduit between the White House and the Senate, and a potential emissary to GOP lawmakers.

The senator, who sits on the Judiciary and Foreign Relations committees and is often in the thick of cross-party negotiations, says he’s optimistic about a better tone and more bipartisanship in Washington.

“Frankly, we don’t have a choice,” he says. “This may be our last, best chance to show that we can make the Senate work.”

What follows is an edited, condensed transcript of the interview.

‘Our last, best chance’ to heal Senate, says key Biden ally

The last president to enter the Oval Office with the congressional credentials of Joe Biden was Democrat Lyndon Baines Johnson – though Mr. Biden, who spent 36 years in the Senate, has him beat by more than a decade on the Hill. The two men did not overlap, but they experienced the same kind of Senate, one built on personal relationships, with wheeling and dealing across the aisle.

Today’s Senate is very different, and in many ways that’s a good thing (for instance, the growing presence of female lawmakers). But senators are now divided by a hard, partisan line, with Republicans and Democrats mostly firing at each other from their bunkers.

Yet as Congress finally moves forward on a $900 billion pandemic relief bill, announced Sunday night, some see glimmers of hope for the next term. The president-elect lays great worth on his relationships with members of both parties on the Hill, and hopes that will help pave the way to bipartisan agreements. Will his ties and experience make a difference?

The Monitor recently talked about all this with Sen. Chris Coons, the Democrat from Delaware who holds President-elect Biden’s former seat. The two men are close, and Senator Coons has already emerged as one of the incoming president’s key point people in Congress – a conduit between the White House and the Senate, and an emissary to GOP lawmakers.

The senator, who sits on the Judiciary and Foreign Relations committees and is often in the thick of cross-party negotiations, says he’s hopeful about a better tone and more bipartisanship in Washington.

“Frankly, we don’t have a choice,” he says. “This may be our last, best chance to show that we can make the Senate work.”

What follows is an edited, condensed transcript of the interview.

Q: To what extent do personal relationships still matter in Washington?

This isn’t the Senate that Joe left – and it’s certainly not the Senate of 20 or 30 years ago, where senators mostly moved their families here, and socialized and readily worked across the aisle. Throughout the entire presidential campaign, lots of media commentators dismissed Joe Biden’s message of decency and civility and his hope for bipartisanship, and said that just couldn’t work anymore.

But in the real world, that’s what people want from their government – that we would respect each other, hear each other, compromise, and solve problems.

What I hear from my colleagues, both Republicans and Democrats, is they all believe he is a decent and caring man. That stands out, particularly in a place where there are so few chances to build and sustain real relationships. Now he’s going to have a chance to prove that you actually can do it.

Q: President-elect Biden told you he needed you in the Senate, rather than as secretary of state. What do you think your contribution can be for him in the Senate?

I’ll give you an example. I’ve had a series of conversations with John Cornyn. You know, John is a very capable partisan warrior from Texas. He has recently taken to somewhat jokingly calling me his “Ambassador of Quan” [from the movie Jerry Maguire]. He sort of pokes me in the ribs and points other Republicans to me and says, “he’s your Ambassador of Quan – he’s the guy who’s going to help us figure out how to work together.”

Cornyn is someone who is probably going to chair the immigration subcommittee. He’s been a pretty tough hard-liner on immigration.

[But] he had a really good, positive opening call with the president-elect and I’m optimistic that I can help weave together a constructive and positive relationship, and that Dick Durbin [Democrat of Illinois] and John Cornyn can end up making progress on an issue like Dreamers that really has eluded us.

I’m not saying that we’re all going to suddenly be standing arm in arm, singing “Kumbaya” on the floor of the Senate. But if you listen to your colleagues and figure out what they most care about, it is possible to find good partners and get things done.

Q: How did you first come to know Joe Biden? You’ve mentioned him as a mentor. What has he taught you?

I was a law-student intern on the Senate Judiciary Committee 30 years ago. I got to know Joe Biden just a little bit, mostly by watching him during hearings. It’s when I ran for New Castle County council that we first started talking most regularly. He was a New Castle County councilman, and the only other person in Delaware history to go from county government straight to the U.S. Senate.

Most people who run for office for the first time are all excited about their policy platforms. He said, first, you have to listen more than you talk. You have to actually recognize that the people you’re running to represent, they’ve got their policy platform. And it’s probably very direct things like “fix the pothole.” So don’t overthink it. Listen.

But second, you need to know what you’re willing to lose [an election] over.

Here’s his other piece of advice, often repeated: You can always question a Senate colleague’s policy conclusions, but don’t question their motives. When you go to the floor and denounce a colleague as being bought and sold by big tobacco or something, you prevent them from ever being able or willing to compromise with you or work with you, once you’ve questioned their integrity.

Now, having watched today’s remarkable exchange at the Homeland Security Committee hearing about electoral fraud, where Senator [Ron] Johnson of Wisconsin, was yelling at Senator [Gary] Peters that he’s a liar over and over, it’s striking to reflect that Joe could say to me that as of 2000, he wasn’t aware of any time when any of his colleagues had questioned each other’s motives or integrity on the floor of the Senate.

So, I do think the institution is under genuine strain. The last four years have been particularly hard on that front, in terms of a commitment to respect and civility and truthfulness.

Q: You mentioned how the media discounted Biden’s message. Do you think they’re underestimating the desire for normalcy in politics on the Hill?

Absolutely. I have had conversations with a dozen Republicans of all levels of seniority, from the brand new to the seasoned, saying that they’re just relieved – that the last four years have been exhausting. And whether you love him and support him, or you loathe him and find him appalling, one thing Donald Trump was, was a master at holding the attention of our nation and changing it to a new crisis, a new issue, a new challenge every single week, often every day, sometimes within the same day. It was a wild ride.

Lots of members of the Senate of both parties have confided in me that they are looking forward to a little more normal, civil, traditional dialogue between the Senate and the White House. And that, as much as people will have small comments or complaints or concerns about nominees, the one clear thing about the cabinet that Joe Biden is assembling now is this is a very seasoned and experienced group. And that’s going to make for less sudden, unexpected, abrupt changes in direction and policy.

Q: After the caustic Supreme Court nomination hearings for Brett Kavanaugh, you said you were going to redouble your efforts at getting to know your Republican colleagues. Did you follow up on that?

Yes. There are literally a dozen Republicans who will tell you that I have redoubled my efforts. It’s been hard because Bob Corker, Jeff Flake, Johnny Isakson, and John McCain were wonderful partners [who have retired or, in Senator McCain’s case, died]. I got a lot done with them.

It’s been challenging to have to start anew with a bunch of other colleagues. But the best example I can give you is Mike Braun [Republican of Indiana]. Mike’s in his first two years and is literally one of the most conservative people I’ve ever met. Yet he and I have founded and are leading the Climate Solutions Caucus together.

We talk regularly. There are 14 members, seven Republicans, seven Democrats. Even in the midst of a pandemic, we did events every single month, often two a month. Think about it. You got seven Republicans who are publicly saying climate change is real, people cause it, and we urgently need to do something about it.

A part of it is we’re in the prayer breakfast together. And a part of it is I made the effort to go meet with [Senator Braun] and sit down and listen and ask him what he cared about and what he wanted to work on.

When my friend Joe Donnelly was running against Mike Braun, I never in a million years would have guessed I’d be having a productive working relationship with that guy. And yet, here we are.

‘We have been re-written into history’: Tribes cheer Interior secretary pick

Native Americans have famously struggled to find respect from the federal government, even around issues that affect them most. We look at what Cabinet-level representation could mean.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The announcement of Rep. Deb Haaland’s nomination last week to become secretary of the Interior uncorked waves of emotion from the Great Lakes to California’s Redwood forests to the Oklahoma plains.

A sign of growing political power and organization in Indian Country, Representative Haaland taking lead of the sprawling Department of the Interior would put Native Americans at the forefront of the Biden administration’s efforts to take sweeping action on climate change.

And it would represent an unprecedented shift in U.S.-tribal relations, giving tribes an access to power they haven’t enjoyed since they began signing treaties in 1778.

“The excitement is palpable in Indian Country,” says Traci Morris, executive director of the American Indian Policy Institute. “It makes us part of the present, not just part of the history.”

And after a year marked by natural disaster and pandemic, adds Dr. Morris, it’s the perfect time for a Native woman to take control of the agency that “manages the physical manifestation of America.”

“It’s who we are to take care of these places, to be the best stewards we can for future generations,” she continues. “Those are our American lands. It’s our American water. ... Indigenous issues are American issues.”

‘We have been re-written into history’: Tribes cheer Interior secretary pick

Nature is not something you inherit from your ancestors but something you steward for your descendants. At least that’s the Indigenous view.

In recent centuries, that view hasn’t carried much weight beyond tribal boundaries. Over the history of tribes’ government-to-government relationship with Washington – formalized after centuries of exploitation and bloodshed – there has been a lot more take than give from Uncle Sam.

That could soon change.

Following weeks of grassroots campaigning, Democratic Rep. Deb Haaland of New Mexico, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna tribe, has been nominated for Secretary of the Interior by President-elect Joe Biden. If confirmed she would become the first Native American Cabinet secretary in U.S. history.

A victory for progressives, and a sign of growing political power and organization in Indian Country, Representative Haaland taking lead of the sprawling Department of the Interior (DOI) would put Native Americans at the forefront of the Biden administration’s efforts to take sweeping action on climate change.

But her appointment would represent much more than policy shifts. Especially for Native Americans, it would mark an unprecedented shift in U.S.-tribal relations, giving tribes an access to power they haven’t enjoyed since they began signing treaties in 1778.

“The excitement is palpable in Indian Country,” says Traci Morris, executive director of the American Indian Policy Institute at Arizona State University. “It makes us part of the present, not just part of the history.”

And after a year marked by natural disasters and pandemic-induced quarantines, adds Dr. Morris, it’s the perfect time for a Native woman to be taking control of the agency that “manages the physical manifestation of America.”

“It’s who we are to take care of these places, to be the best stewards we can for future generations,” she continues. “Those are our American lands. It’s our American water. ... Indigenous issues are American issues.”

Beyond box-checking

The Interior Department has been the principal point of contact between the federal government and tribal communities – from managing lands and resources, to education and economic development – since it was formed in the mid-19th century. That relationship has typically been sour, if not outright hostile.

From allotment policies in the 19th century that saw millions of acres of land taken from tribes, to forcibly sending their children to residential schools designed to assimilate them into white culture, even to the modern era of self-determination where tribes have had more control of their own affairs, Native Americans say the DOI has more often been seen as an adversary than a co-equal government partner.

Native Americans have had prominent positions in the agency, including leading the Bureau of Indian Affairs, but having a Native woman in the top position would be a quantum leap. Not just progress, but a wholesale rebalancing of the relationship.

“It’s resetting the relationship with the first peoples of this land,” says Crystal Echo Hawk, founder and CEO of IllumiNatives, a nonprofit advocacy group.

“We know Deb, we trust Deb, and that’s never been had before.”

The announcement of Representative Haaland’s nomination last week uncorked waves of emotion from the Great Lakes to California’s Redwood forests to the Oklahoma plains.

After a year in which Native communities have been ravaged by the COVID-19 pandemic and by unprecedented, climate change-fueled wildfires across the western U.S., they voted in droves to help Mr. Biden win key states like Arizona and Wisconsin. Once that had been achieved, they turned their attention to campaigning for Representative Haaland’s nomination for Interior secretary.

Ms. Echo Hawk, a member of the Cherokee Nation, cried after she heard. So did her daughter, her nieces, and her friend, who broke the news to her.

“This is more than just checking a box for diversity in the Cabinet,” she says.

“Native people have been made to think we’re less than human, that things aren’t possible for us, and [Representative Haaland] once again shattered that glass ceiling.”

A lonely path

This isn’t the first trail the New Mexico politician has blazed. Two years ago she became one of the first two Native women to be elected to Congress.

But in that capacity she had the companionship of Rep. Sharice Davids of Kansas, a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation. If she is confirmed by the Senate next year she will be taking on a much more challenging – and lonely – position.

If anyone has an idea of what she’s in for, it’s Judge Abby Abinanti, the first Native woman to pass the California bar and be a state judge.

“This is going to take and take and take from her,” says Judge Abinanti, who has spoken occasionally with Representative Haaland.

“You just have to realize, and she will, it’s not about me, it’s about what our role is,” she adds. “You just reach back into yourself. She was raised with that strength, and she can do this.”

A single mom who has lived off food stamps and still had student debt from law school when she entered Congress in 2018, Representative Haaland has developed a reputation as a productive and progressive lawmaker capable of working across the aisle.

Bipartisanship and pragmatism have been common traits among the few Native lawmakers who’ve worked on Capitol Hill. They’ve frequently been members of both parties, and tribal issues themselves have historically been nonpartisan. Whichever party is in power, tribes have had to work with them.

“Tribes will find friends where they can find friends,” says Keith Harper, a member of Cherokee Nation and the first Native American to represent the U.S. on the U.N. Human Rights Council.

Representative Haaland “has a deep commitment to certain values, but she also knows how to work with others,” he adds. “It’s an inspired and visionary choice tailor-made for this precise moment.”

From Republicans to progressive Democrats – including Republican Rep. Tom Cole of Oklahoma and Democratic Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York – many in Congress agree. And she is now poised to take control of an agency with a portfolio that reaches far beyond Indian Country.

“We need to engage”

With 70,000 employees and a budget of about $12 billion, Representative Haaland would take charge of not only the Bureau of Indian Education but also the U.S. Geological Survey and the Office of Small and Disadvantaged Business Utilization. The DOI manages not just federal lands, water, and wildlife but also natural resources. That balance between Native issues, conservation, and energy and economic development is a challenging balance for any Interior secretary to strike.

What Indian Country expects is that Representative Haaland would strike that balance in a way no other Interior secretary has before.

“She understands the balance between energy needs and jobs and a decent life for all people, including ours,” says Judith Le Blanc, director of the Native Organizers Alliance and a member of the Caddo Tribe of Oklahoma.

“No doubt it will be a very tough road,” she adds. But “she will be able to balance the needs of Mother Earth and of people.”

Representative Haaland’s work would make Indian Country “feel that we have been re-written into history.”

“I’m feeling a little emotional,” she continues. “For democracy to be full and complete and meet the expectations people have for democracy, we need more Debs.”

Indeed, Indigenous approaches and philosophies have been marginalized for so long in the U.S. that they represent an untapped well of solutions for the country, says Judge Abinanti.

The Yurok tribe live in a secluded corner of the Northern California coast, and this year she has watched her community grapple with wildfires and a bad salmon run. River and forest management are two areas where the Yurok – and tribes across the country – have seen their generations of expertise go unheeded by Washington.

“We have said forever, ‘Do controlled burns.’ Now people are saying, ‘We should do controlled burns,’” says Judge Abinanti. “It just makes you want to hit yourself in the head with a rock.”

But tribes have also, historically, not engaged enough with the world, Native activists say. This is in part due to a focus on tribal government and preserving cultures brought near the brink of extinction, but with the political activism of 2020 that era of insularity seems to be ending. Representative Haaland is leading it.

“They need to know things that we know, and we ... need to implement them,” says Judge Abinanti, “or everybody’s going to go down on this ship.”

“We were never the kind of people who ran and hid. ... We did that to survive,” she adds. “Now we’re [realizing] that’s not how this place is going to survive. We need to engage.”

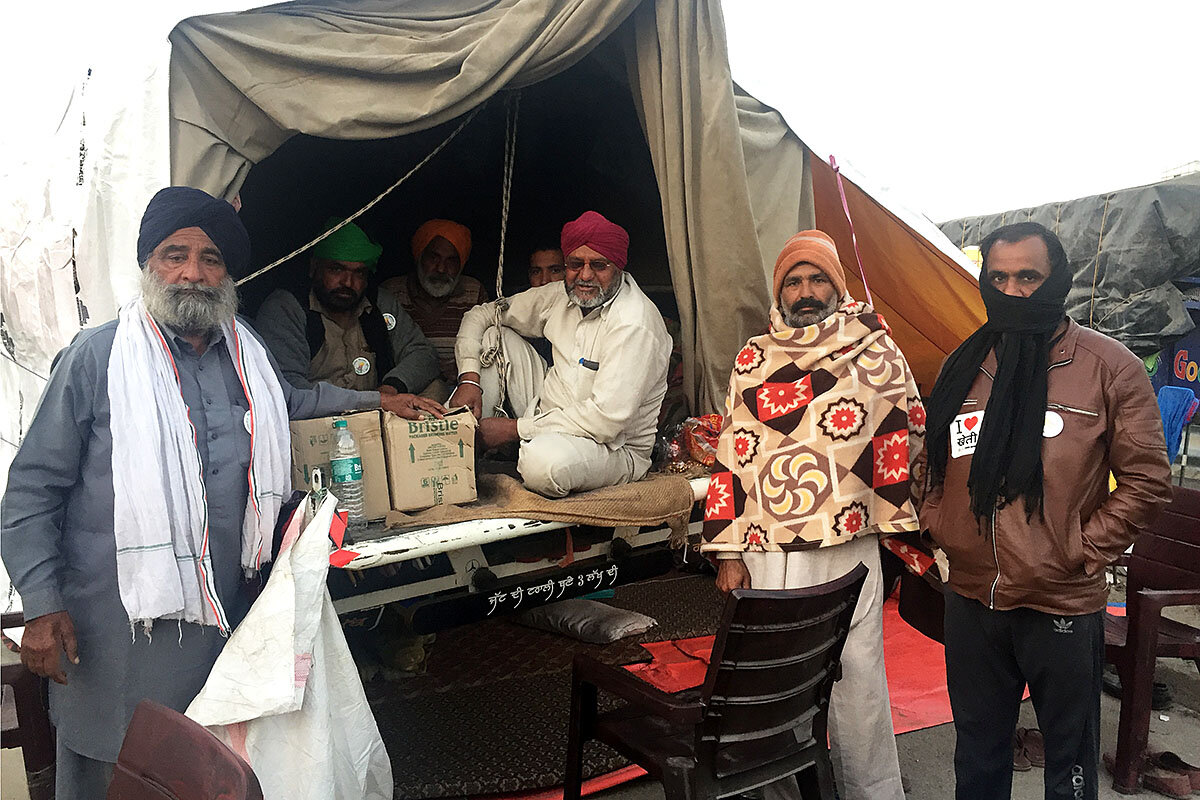

Why India’s protesting farmers aren’t going home

India’s big-scale farmer protests are about more than changes to agricultural laws. They also tap into concern over shrinking space for consultation, debate, and dissent.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Sarita Santoshini Correspondent

For three weeks, mile after mile of trucks and tractor-trailers have been piled up just north of New Delhi. The farmers who drove them here are protesting agricultural laws they worry will hurt their earnings and benefit tycoons. And there is no sign of a retreat. Trucks hand out oranges, and stalls distribute hot tea and pudding to passersby. Temporary salons have sprung up. For now, these roads and trailers are their home, despite the cold.

“More farmers are joining us next week,” says farmer Ram Singh, who traveled 140 miles to join. “Most of our wives and children are back home for now, but they’ll join us, too, if needed.”

As Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s administration veers right, fellow Hindu nationalists have often dismissed critics as “anti-national.” But agriculture employs half of India’s workforce, making the farmers’ protests one of the most serious challenges yet to his populist image. And the demonstrations have come to symbolize a wider kind of discontent, about democratic ideals and room for dissent in India today.

“Farmers have a powerful symbolic place in Indian society,” says Irfan Nooruddin, director of the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center, “and cannot be as easily dismissed as ‘elites’ who are out of touch with the general national mood.”

Why India’s protesting farmers aren’t going home

At a certain point at the northern edge of India’s capital, New Delhi, the highway abruptly gives way to police barricades. Usually busy with vehicles making their way to the neighboring state of Haryana, traffic now comes to a dead stop. Stretching for miles after that are trucks and tractor-trailers that thousands of farmers used to get here, now parked to block the so-called Singhu border between states in protest.

Huddled with a few others in the rear of one of these tractor-trailers on a chilly December evening is Ram Singh, a wheat and rice farmer from Bhodi village in Haryana. He traveled about 140 miles to join this weekslong protest, demanding that the government rescind three hastily enacted agricultural laws. Like others gathered here, he believes that the laws will reduce his earnings while benefiting large corporations.

The legislation effectively deregulates the marketing of produce, limiting the role of government-run markets and price support systems. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has hailed this as a landmark reform that will remove middlemen and allow farmers to sell directly to large institutional buyers and retailers. Critics argue that farmers will not have the negotiating power to do so, and could be at the mercy of two billionaires who own large conglomerates. Additionally, one of the laws restrains citizens from taking disputes under it to regular courts.

“There will be hoarding. What is 10 rupees a kilo today they [corporates] will sell for 100 rupees a kilo tomorrow with their profits in mind. Along with farmers, this will affect laborers, shopkeepers, even city residents who’ll have to pay a hefty price,” Mr. Singh says. “This is everyone’s loss – marginal farmers, landowners, laborers. We are all in this together.”

Since Prime Minister Modi took office in 2014, his administration has veered to the right, prompting complaints about shrinking space for dissent and diversity – criticism that Hindu nationalists in his Bharatiya Janata Party often dismiss as “anti-national.” But agriculture employs half of India’s workforce, making the farmers’ protests one of the most serious challenges yet to Mr. Modi’s populist image.

Farmers at the Singhu border have been here for over 20 days, and there is no sign of a retreat. Support has been pouring in from different parts of the country. “More farmers are joining us next week,” Mr. Singh adds. “Most of our wives and children are back home for now, but they’ll join us, too, if needed.” At least 25 protesters have died, many of them due to the cold.

A large stage has been set up for speeches, and open-air kitchens serve meals throughout the day. There are trucks handing out oranges, and stalls distributing hot cups of tea and bowls of kheer, an Indian pudding. Temporary salons have sprung up, as have several shaded areas lined with cushions where farmers can rest. In one of them, young Sikh men carefully wrap turbans around the heads of fellow protesters. Medical students and doctors offer free checkups and medicines. A few waterproof tents offer some protection from the cold. For now, these roads and trailers are their home.

Rising public distrust

While the agricultural laws served as an immediate trigger, experts say it’s important to not look at them in a vacuum. The agricultural sector faces a deepening crisis, with a large percentage of farmers carrying mounting debts. Over 10,000 farmers died by suicide in 2019. As Indians reel amid the ongoing pandemic, its economic consequences have also fed frustration.

“There is a lot of simmering discontent among migrant and other workers, and this will grow because the economic conditions continue to deteriorate and people are losing livelihoods and lakhs [hundreds of thousands] of small enterprises are going under,” says Jayati Ghosh, a development economist. “Also, the idea that these laws were passed to benefit cronies has taken root.”

In the face of erratic weather patterns, water scarcity, rising debts, and insufficient government support, farmers from across the country have taken to the streets numerous times in the past few years. This time, however, their anger is directed at Modi’s government and its business allies. Across the country, farmers’ groups echo similar sentiments: They cannot trust the government.

Parliament passed the trio of laws in September over vehement protest by opposition parties. Outside, farmers in Punjab and Haryana states had already begun to demonstrate, arguing that the laws did not serve their interests and they had not been sufficiently consulted.

“This government has developed a reputation for making big decisions with little to no consultation with other stakeholders,” says Irfan Nooruddin, director of the South Asia Center at the Atlantic Council in Washington, D.C. From demonitization of Indian bank notes in 2016, to revoking Kashmir’s statehood last year, or the Citizenship Amendment Act last winter, major decisions have been “dropped on the Indian public in surprise.”

Each time, the government has justified these decisions as beneficial policies on major issues that have been lingering for a long time and needed tough, decisive actions.

“The consequence is that affected groups feel little recourse to influence the government other than by protests and demonstrations after the fact since the government shows little appetite for consensus-building,” Mr. Nooruddin says.

Long road ahead

Posters at the Singhu border declare, “We are farmers. We are not terrorists.” It’s a reference to how the government responded to those marching toward Delhi last month: barbed-wire fences, tear gas, and water cannons. Pro-government media have accused the farmers of being “brainwashed” by misinformation about the bill.

In such turbulent times, the farmers’ protest has become a symbol of a larger kind of dissent, reflecting concerns about democratic ideals and human rights. At Tikri border, another protest site, farmers raised pictures of human rights activists and intellectuals detained under an anti-terror law and called for their release.

The images of the protests create a public relations dilemma for the government, Mr. Nooruddin says. “Farmers have a powerful symbolic place in Indian society and cannot be as easily dismissed as ‘elites’ who are out of touch with the general national mood.”

During India’s last mass protests, against the citizenship law for refugees that excluded Muslims, the government portrayed protesters as unpatriotic radicals. But this time, officials are willing to talk. Six rounds of discussions with farm union leaders, however, have failed to bear any results. Farmers are adamant that the laws be revoked, not amended.

In Singhu border, Sher Singh, a farmer from Punjab, is helping to unload vegetables and takes a minute to step aside and talk. “Those in power, they dream of a Hindu nation,” he says, referring to the ruling party’s Hindu nationalist agenda. “What nation? When ordinary citizens like us are hurting so much, what is the point of all this nation-building?”

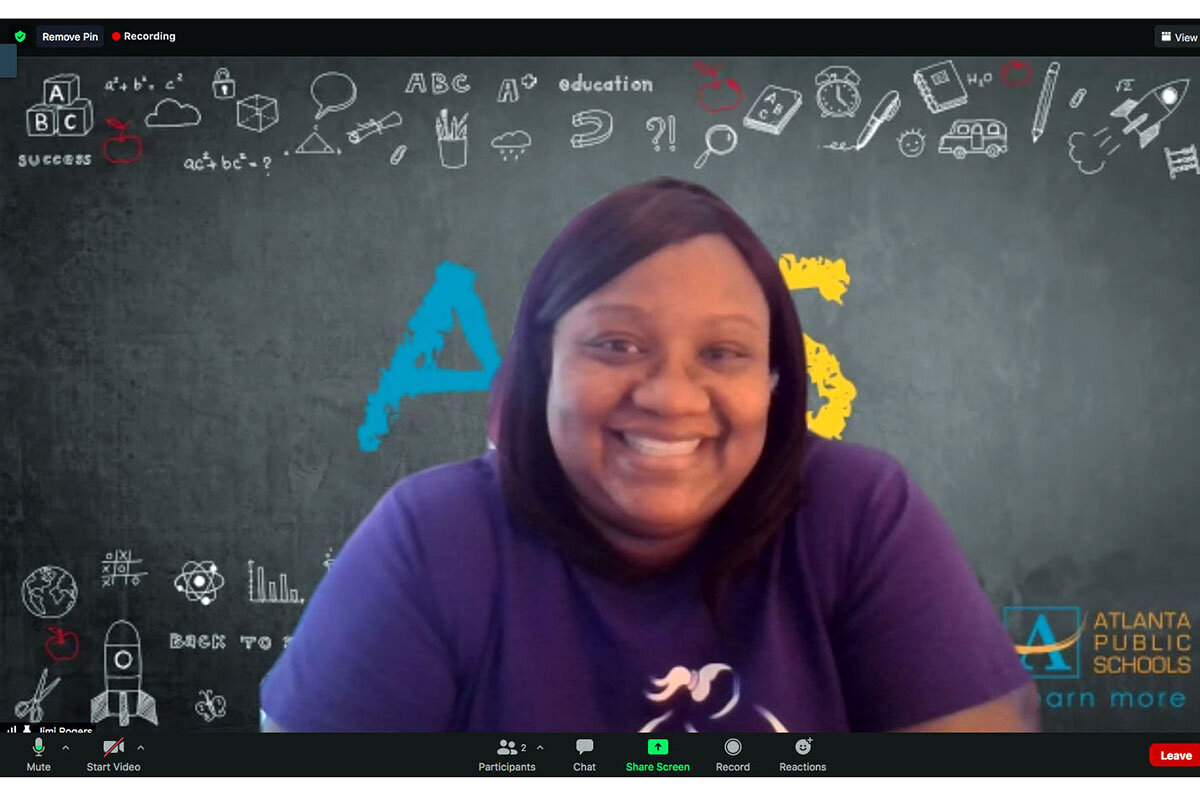

‘Good morning, sweet girl’: A day in the life of an online teacher

The world of education is changing. Meet one of many teachers who still want their students to change the world. Our writer sat in via Zoom, and found determination and grace.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Faulty browsers, sibling cameos, the occasional frantic dog tail in the corner of a screen: These are a few of the daily surprises that scatter focus and make remote teachers like Jimi’ Rogers into air traffic controllers of virtual space.

A day in the life of Ms. Rogers, a third grade teacher at L.O. Kimberly Elementary School in Atlanta, is a window on how much of the learning environment of the pandemic seems out of her control. On a typical day, only three-fourths of her class shows up, and Ms. Rogers has only met four of her pupils in person through tutoring at the school and home visits.

And yet, it is also a hopeful view of the educational triage a veteran teacher can bring. Yes, she sees when heads tilt in frustration, but there are moments of mastery, too, and she focuses on what she can control: her own preparation and poise.

“You need to be on-point so that they can go out into the world and change the world, like your teachers did for you,” says the Georgia native, whose own third grade teacher sparked her love of reading.

‘Good morning, sweet girl’: A day in the life of an online teacher

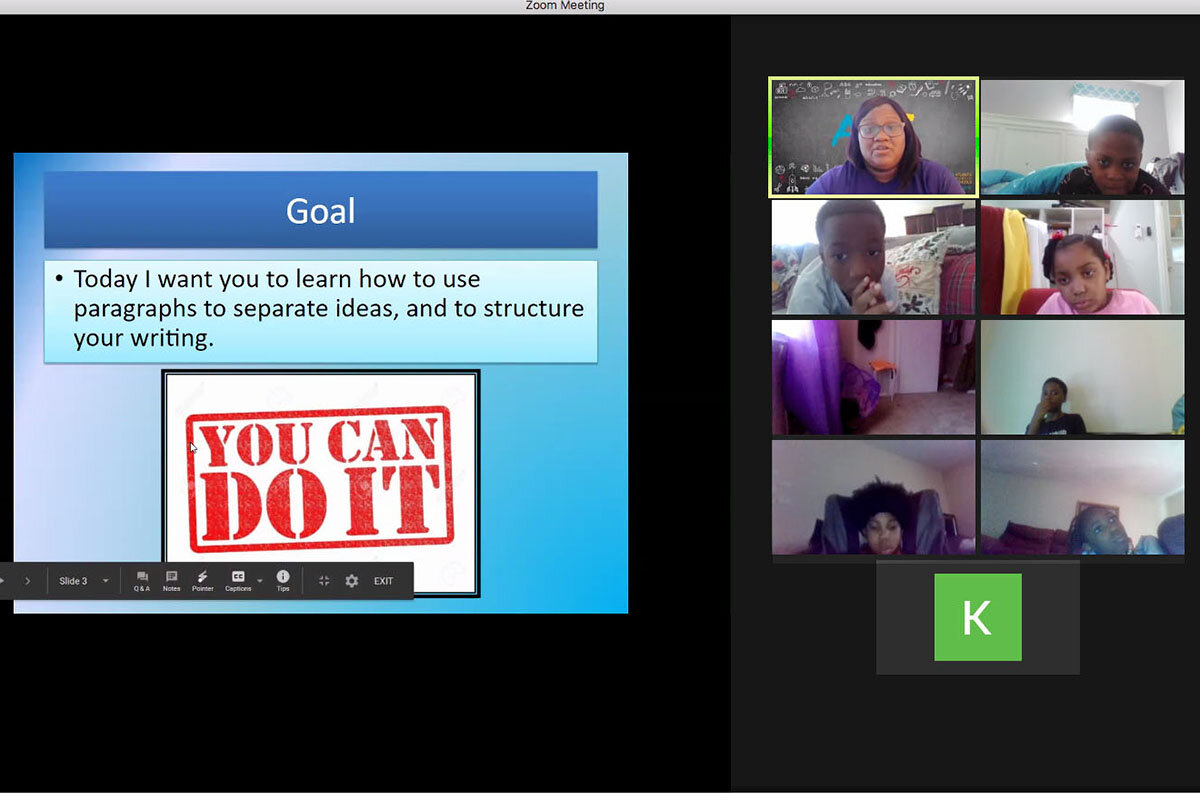

The third graders lean in to type, turning the Zoom classroom into a mosaic of mostly foreheads. Answering equations in an app monitored by their teacher, some L.O. Kimberly Elementary School scholars mouth along as their fingers find the keys.

A math test looms tomorrow and it’s time to review. Jimi’ Rogers knows the stakes: Of the dozen students in her virtual class, five are struggling to meet math benchmarks. Yet she stays calm and encouraging this Tuesday morning as she asks them to add 349 and 145 – and show how they arrived at the answer.

“I really appreciate the hard work,” Ms. Rogers tells them. Her home office is hidden by a Zoom background, a digital chalkboard with Atlanta Public Schools’ logo. “I’ll give you about four minutes to do this, OK?”

Before she utters “OK,” a student has typed in the chat: my dog step on my keyborad

Another girl unmutes herself to announce she has a notebook and pencil. “Very good,” Ms. Rogers patiently replies, as the girl dangles a metallic-gold pencil pouch for the camera.

The first student updates in the chat that the dog made a mess on the living room floor.

“I don’t need to know about that, honey,” the teacher intones. “Handle that, please.”

The pandemic has turned remote teachers like Ms. Rogers into air traffic controllers of virtual spaces – upended by technical snags and the randomness of home life. Teachers like her, who are working more hours than before, are keenly aware of potential learning loss and other fallout from unequal access to school.

A view into Ms. Rogers’ “classroom” reveals that keeping pupils on track means constantly adapting to an environment where so much is out of a teacher’s control. And yet, for every head that tilts in frustration, there are moments of mastery, too. Inspired by her students, Ms. Rogers focuses on what she can control: her own preparation and poise.

“We teachers are doing the best that we can,” she says.

School days for Ms. Rogers often start with a 4:45 a.m. wakeup. She drives to the gym for the treadmill, followed by a peppermint tea. She refreshes her devices next, resetting her router and restarting her computer to ward off digital glitches before she logs into her classroom at 8 a.m.

“Good morning, sweet girl,” she greets a student whose camera stays off for most of the day.

Ms. Rogers has only met four of her pupils in person through home visits and tutoring at the school. She laments: “I’m a hugger, and I can’t hug them right now.”

Fresh respect

Beyond classroom management, there’s the long-term worry of kids falling behind in new learning formats. Like thousands of her colleagues across the country, Ms. Rogers had little choice but to adapt to digital teaching.

“Being honest, there’s a lot more I could do if we were face-to-face,” she says.

In her eighth year of teaching and first at Kimberly Elementary, she says preparing virtual lessons – from creating slides to catching up kids who fall behind – takes 10 to 15 hours a week outside her normal school day. That’s more work than previous years, in part because she’s adjusting to a new school.

“You need to be on-point so that they can go out into the world and change the world, like your teachers did for you,” says the Georgia native, whose own third grade teacher sparked her love of reading through “The Chronicles of Narnia.”

The extra planning takes a personal toll. Ms. Rogers’ fiancé has watched her preparation eat into their weekends. Since online classes began, “I have a whole other level of respect for her,” he says.

Outside of class, Ms. Rogers regularly reaches out to students and parents to make sure they’re OK. She arrived at a student’s home with food from KFC this fall following a death in the child’s family.

Trying to bridge the digital distance can be frustrating, she says; three-fourths of her class typically shows up. Since Atlanta school buildings closed in March, 90% of Kimberly Elementary students have received Chromebooks or iPads, and the district has also chipped in hotspots. Still, tech issues linger.

Daily surprises scatter focus – faulty browsers, sibling cameos, the occasional frantic dog tail in the corner of a screen.

During a recent writing lesson, an adult’s shoulder hovers in one pupil’s screen. “Scholars, again, this is your own work,” Ms. Rogers says, then fires off a private message with her sleek red nails.

Her favorite virtual moment arrived during a November math class as she taught a rounding lesson. When she encouraged her students to unmute, the result was “exciting,” she says. Everyone wanted to participate.

“Finally, I feel like I’m getting through,” she recalls thinking. “These kids and I are now building this safe space where it’s OK for them to talk in a virtual environment.”

During language arts, she asks a quiet boy to read aloud a page from a French folktale that will test his group’s comprehension. Rontavius smiles, and Ms. Rogers returns the grin when he begins a couple decibels above a whisper.

“‘I see,’ said the snail. ‘And you have proof that the Earth is round?’” he reads smoothly.

The digital book font is small, so Ms. Rogers tries to zoom in. But her webpage turns blank as it buffers – computer purgatory. His voice continues undeterred, though his forehead will freeze in profile before class ends. Rontavius finishes the page and wipes his brow in apparent relief.

“All right, very good,” Ms. Rogers tells him. “Although I don’t know what just happened.”

She’s used to such glitches and moves on. Plus, Ms. Rogers says the students model her behavior: “If they know that I’m OK and I’m upbeat, they will do the same thing.”

Ms. Rogers strives for perfection, but pandemic demands have taught her to be gentler with herself. She says she’s learning to accept that teachers make mistakes.

“Before, I was like: You don’t have the room to make a mistake, because you’re teaching the future,” she says.

During a recent math class, Ms. Rogers admitted to the class she’d misread a multistep word problem. Then a student typed her a love note into the Zoom chat for all to see.

“That made me feel really good today,” Ms. Rogers says after class. She may not always have their attention, but she has their respect.

“Locus of control”

Ongoing research points to greater learning loss in math than reading. Test data from one study of 4.4 million U.S. students suggest that the pandemic pivot to online learning has meant a “moderate” drop in students’ math skills, though the sample underrepresents marginalized students. Principal Joseph L. Salley says some learning loss is likely during the pandemic at the majority-Black, 336-student school; but he tries to calm staff nerves.

For teachers, he says, “it’s all about focusing on what’s in your locus of control.”

While the school is still reviewing benchmark assessments to determine math and reading growth at the time of writing, the principal praises Ms. Rogers’ preparation and embrace of new technology. She uses breakout rooms and interactive slides on Google Jamboard, for instance, where students cut and paste units of measure to solve math problems. At the end of class, they submit virtual “exit tickets” that gauge their grasp of a lesson.

“Despite the pandemic, she hasn’t skipped a beat!” he says.

Schools with the highest shares of minority students and poverty have been less prone to offer in-person instruction during the pandemic, according to Rand Corp. research (75% of students are eligible for free or reduced lunch at Kimberly Elementary). The district has announced plans to phase into in-person classes after winter break, and Mr. Salley is preparing new safety protocols.

As much as Ms. Rogers supports her school leadership – and loves her “magnificent 12” – she says her feelings are mixed. With an underlying health condition, she’s wary of catching the virus; that’s why she heads to the gym at unpopular hours.

“I have to work … I’m going to pray about it,” says Ms. Rogers, a Baptist.

In the meantime, she takes one day at a time. During Tuesday afternoon’s introduction to the concept of the paragraph, she asks them to post what they know in the chat, reminding them there are no wrong answers.

Responses trickle in. She sees that only the girls have chimed in.

“I got nothing from my boys, and it breaks my heart!” she proclaims. The young ladies take turns typing out an intervention.

One writes: try your best boys its ok if you are wrong some times you make mistaks

It’s ultimately not enough to rouse their peers, but Ms. Rogers keeps the class moving. She’s generous with praise, even if their thinking is unconventional.

“Nyla, can I show yours to the class for a second?” she asks. Nyla nods in earnest, jangling her long black braids.

Ms. Rogers presents Nyla’s Google doc, a composition about frogs. The twist: The block of text is typed out in six rainbow colors – red through indigo – shifting hue with topics.

“This is an excellent way to spread out your ideas,” Ms. Rogers gushes. Nyla leans in.

Ms. Rogers starts her cursor at the top of the text and indents where the colors change. The rainbow cascades down the page as paragraphs appear.

It’s already 2 o’clock. In a moment, Ms. Rogers’ scholars will disappear with a click.

Their screens briefly blur as they wave.

Editor’s note: Ms. Rogers’ fiancé’s name has been removed due to security concerns.

Film

From ‘American Utopia’ to ‘Ma Rainey,’ the 10 best films of 2020

Moviegoers’ migration from cinema to couch and the travails of big-budget productions were big 2020 stories. Our film critic found gold in the more intimate movies that reveal new talent.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Peter Rainer Special correspondent

Do I miss seeing films in big theaters on a big screen with a big audience? You bet I do. But those days will return.

My initial concerns of a famished 2020 movie year were vastly exaggerated: After the pandemic began, a large backlog of small-scale, independent movies transitioned fairly smoothly to the home screen. The big studios had a rougher time of it: Many movies have been pushed well into next year.

Many imponderables remain, but relatively modest and inexpensive dramas may end up as the true beneficiaries of this era. The low-budget indie movie realm is often where fresh new talent – the lifeblood of a thriving art form – breaks through.

It’s no coincidence, then, that most of the films I value this year were the documentaries and the more intimate human dramas. My list ranges from adaptions of an August Wilson play and a Jane Austen novel, to documentaries on David Byrne’s Broadway show, meteorites, and an inspiring look at the empathy inside four hospitals this year in Wuhan, China.

From ‘American Utopia’ to ‘Ma Rainey,’ the 10 best films of 2020

For all of us who love the moviegoing experience, 2020 has been, to put it charitably, a trying year. For most of America, and in many parts of the world, going to indoor movie theaters remains largely out of bounds. And so we have adapted by watching films on smallish home screens via DVD, cable, and streaming services. Do I miss seeing films in big theaters on a big screen with a big audience? You bet I do.

Those days will return, but, in the meantime, I am happy to report that my initial concerns of a famished 2020 movie year were vastly exaggerated. A large backlog of small-scale, independent movies, originally poised for a theatrical release, transitioned fairly smoothly to the home screen. The movie studios had a rougher time of it: In many cases, their major movies, mostly completed before the pandemic and ranging from the latest James Bond escapade to Steven Spielberg’s “West Side Story,” have been pushed well into next year.

Many imponderables remain: What will theatrical moviegoing look like when it comes back? Will the theaters, especially the smaller specialty houses, be able to survive? Since film production was severely curtailed for much of 2020, will there be a dearth of new movies in 2021? And what will those new movies look like going forward?

It’s difficult to imagine, for example, any studio investing enormous sums for large-scale productions requiring a huge cast and multiple far-flung locations. Relatively modest and inexpensive dramas may end up as the true beneficiaries of this era. This would not, I think, be such a bad thing. The low-budget indie movie realm is often where fresh new talent breaks through. And fresh talent, in any era, is the lifeblood of a thriving art form.

It’s no coincidence, then, that most of the films I value this year were the documentaries and the more intimate human dramas. Even in better times, these run more to my taste. With this in mind, here, in no particular order, is my annual rundown of the year’s 10 best, plus a brief roster of runners-up. Certainly, in this crazy year, with all of its streaming platform rivulets and tributaries and byways, I cannot pretend to have extensively covered the cinematic waterfront. Also, some of the films I loved, like the documentaries “Gunda” and “The Truffle Hunters,” were given only very brief Oscar-qualifying runs before “opening” for real next year. For this reason, these, and some others, aren’t on my best list, but I look forward to reviewing them anon.

1. David Byrne’s American Utopia – Spike Lee’s documentary of David Byrne’s eponymous 2019 Broadway show, based on his 2018 album, is simply one of the best concert performance films ever made, almost up there with “Stop Making Sense” (featuring The Talking Heads, Byrne’s former group), “The Last Waltz” (The Band), and “Amazing Grace” (Aretha Franklin). Filmed before a live audience on a strikingly spare stage, Byrne and his multicultural troupe of 11 musicians and dancers from around the world, all barefoot in their gray wool suits, offer up a joyous paean to community and what brings us together. (HBO Max; rated TV-14)

2. A Regular Woman – The notorious 2005 “honor killing” of Hatun “Aynur” Sürücü, a 23-year-old Westernized Muslim woman in Germany, by one of her siblings, forms the basis for this extraordinary film directed by Sherry Hormann and starring Almila Bagriacik. Although it includes video footage of the real Sürücü, the film is a dramatic reenactment of her struggle, which she narrates for us both before and after her death. Her postmortem voice-over is more than an avant-garde gimmick. It serves to give the victim the voice against injustice that was denied her in life. The film has a wrenching, cumulative power. (Amazon Prime Video; not rated; in German with English subtitles)

3. City Hall – Fred Wiseman, at 90, is our greatest documentarian. His 45-film body of work eclipses that of all other living American directors. His latest film, running a captivating 4 1/2 hours, is about the inner and outer workings of Boston’s City Hall, focusing on the ministrations of Mayor Marty Walsh. As is true of so many of Wiseman’s films about institutions, the movie is ultimately a novelistic meditation on how people, in all their despair and joy and valor, attempt to live together. (Debuts on PBS on Dec. 22, or click here to see other options; not rated)

4. Emma – Jane Austen novels have so frequently been adapted for the screen that yet another entry, particularly of the oft-filmed “Emma,” might seem superfluous. Not so, in this case.

Anya Taylor-Joy (“The Queen’s Gambit”) plays that disastrously maladroit matchmaker Emma Woodhouse with a full complement of obliviousness, smarts, and guile. Autumn de Wilde directs, her feature debut, from an emotionally layered script by Booker Prize winner Eleanor Catton. (HBO Max; rated PG)

5. Fireball: Visitors From Darker Worlds – It’s one thing to make a documentary about meteorites that drop from the sky. It’s quite another to fashion a film that fully conveys the flat-out awesomeness of such events. Werner Herzog and his co-director, University of Cambridge scientist Clive Oppenheimer, travel the globe – visiting such far-flung locales as Western Australia; Mecca, Saudi Arabia; Norway; and a tiny island located in an archipelago between Australia and New Guinea – in order to show us how extraterrestrial rocks have shaped, both literally and figuratively, our planet and the culture and dreams of its inhabitants. (Apple TV+; rated TV-PG)

6. Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom – Let it be said of this adaptation of August Wilson’s 1984 play that you won’t see a finer pair of performances this year than Viola Davis as the voracious legendary blues singer Ma Rainey, and, in his last appearance, the late Chadwick Boseman as a cocky trumpeter with big ambitions.

In fact, under the direction of George C. Wolfe, the entire acting ensemble, which also includes Glynn Turman and Colman Domingo, is sterling. If we can’t attend live theater right now, this is the next best thing. (Netflix; rated R)

7. Miss Juneteenth – Writer-director Channing Godfrey Peoples’ debut features Nicole Beharie in one of the year’s finest performances as a struggling Fort Worth, Texas, single mom and former beauty queen, who wants a better life for her 15-year-old (Alexis Chikaeze). Few films have so poignantly portrayed the mother-daughter byplay. (Available on streaming platforms; not rated)

8. Never Rarely Sometimes Always – Newcomer Sidney Flanigan plays teenage Autumn, who travels from Pennsylvania to New York City with her devoted cousin, played by Talia Ryder, to secretly terminate her unwanted pregnancy. Both performances, like the film they figure in, are remarkably nuanced. Eliza Hittman has written and directed with the utmost delicacy and verity. She understands how silences can speak far louder than words, and she has the rare ability to film scripted scenes involving actors in a way that comes across as completely naturalistic. Her approach is entirely in keeping with how she handles the sensitivity of the material. This is a human drama we are watching, not a polemic. (HBO Max; rated PG-13)

9. 76 Days – This filmed-in-the-moment documentary, expertly directed by Hao Wu, Weixi Chen, and Anonymous, shows how the pandemic first hit four hospitals in Wuhan, China. It’s often tough to watch, but I think it will become an essential historical document. In showcasing the kindness, empathy, and courage of the medical personnel, it’s just about as inspiring a movie as I’ve ever seen. (Click here to find virtual showings; not rated)

10. The Vast of Night – Two small-town 1950s New Mexico teenagers, winningly played by Jake Horowitz and Sierra McCormick, attempt to decipher a mysterious thrumming noise in this playful microbudget sci-fi escapade. It’s directed by the astonishingly inventive first-timer Andrew Patterson. Rod Serling would, I think, be pleased. (Amazon Prime Video; rated PG-13)

Some runners-up: “Collective,” “Lovers Rock” (a “Small Axe” series segment), “Time,” “Buoyancy,” “Song Without a Name,” “About a Teacher,” “The Outpost,” “Wolfwalkers,” and “Nomadland.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Time to give, big or small

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The Danish term samfundssind has been catching on. It means to consider the needs of others above your own.

The year 2020 has seen the economic chasm between rich and poor widen under the stress of the pandemic. Since March the Dow Jones industrial average has shot up more than 60%, but the economic recovery has stalled. Those living paycheck to paycheck face a sobering picture.

The super wealthy have been criticized for sometimes donating money erratically to causes that personally interest them, rather than might most benefit society.

MacKenzie Scott, the 18th richest person in the world, has taken a different approach. She recently announced she’d given more than $4 billion to at least 384 charities, upping her total giving for the year to about $6 billion. Her gifts come with no strings attached. She has concentrated on helping groups that have been overlooked in the past.

Less wealthy Americans are stepping up too. On Giving Tuesday, Dec. 1, the online event that follows Thanksgiving each year, charitable donations leapt 25% to $2.47 billion, from $1.97 billion in 2019.

For anyone, the joy of giving offers a powerful antidote to the sense of gloom that others may be struggling with this holiday season. Unselfishness shines a bright light for the whole community.

Time to give, big or small

The Danes have popularized two terms that describe how to cope in difficult times. Hygge translates as a sense of coziness, comfort, or contentment. The Danish word pyt means something akin to easing stress by letting go and moving on.

Now a third term, samfundssind, is catching on at just the right time. It means to consider the needs of others above your own. In English we might think of it as community spirit or civic-mindedness. Or maybe just Scrooge awaking from his dream and feeling the joy of helping others.

The year 2020 has seen the economic chasm between rich and poor widen under the stress of the pandemic. While since March the Dow Jones industrial average has shot up more than 60 percent, the economic recovery has stalled. Those with funds invested in markets, including through pension funds or IRAs, have seen their wealth soar. Others, living paycheck to paycheck, face a much grimmer picture.

This year prominent billionaires increased their wealth by a half-trillion dollars, the Business Insider recently calculated. That was at the same that millions were being put out of work as businesses failed or cut back on employees.

Some among the very wealthy have stepped up to help. Over the years the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has give away more than $55 billion, with an emphasis on improving public health, especially in developing countries. Recently the foundation has zeroed in on ways to defeat Covid-19.

The super wealthy have been criticized for sometimes donating money erratically to causes that personally interest them, rather than might most benefit society. But at least they recognize an obligation to give back.

MacKenzie Scott, the former wife of Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, is considered the 18th richest person in the world. She announced she’d recently give more than $4 billion to at least 384 charities, upping her total giving for the year to about $6 billion.

Her approach has gained favorable attention: Her gifts come with no strings attached, no requirement to put her name on anything. She has concentrated on helping groups that are sometimes overlooked in the past, including historically black colleges and community colleges, as well as groups such as food banks and stalwarts such as the YMCA, Meals on Wheels, and Goodwill Industries that directly serve the poor.

“This pandemic has been a wrecking ball in the lives of Americans already struggling,” she wrote in a blog. Economic losses and health challenges have been worse for women, for people of color, and those living in poverty, she said.

It’s gratifying to see that less wealthy Americans are stepping up too. Charitable giving was up 7.5 percent in the first half of 2020 compared with 2019. And on GivingTuesday, Dec. 1, the online event that follows Thanksgiving each year, charitable donations leapt 25 percent to $2.47 billion, from $1.97 billion in 2019. The estimated number of people participating jumped 29 percent, to 34.8 million.

“This groundswell of giving reaffirms that generosity is universal and powerful, and that it acts as an antidote to fear, division, and isolation,” said Asha Curran, the co-founder and CEO of GivingTuesday.

For anyone, of whatever means, the joy of giving offers a powerful antidote to the sense of gloom that others may be struggling with this holiday season. Unselfishness shines a bright light for the whole community.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

A different Christmas but the unchanging Christ

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Alison Jane Hughes

No matter how different our holiday plans end up this year, one thing remains the same – God’s eternal message of love for us.

A different Christmas but the unchanging Christ

This will be a different Christmas season for many this year, with celebrations looking a little unlike our usual festivities. Naturally we all hope to be able to visit more with family and friends again soon.

Some things don’t change, though. Christmas is always a special time to express great gratitude for the life of Christ Jesus. And one of the most encouraging promises we gather from Jesus’ teachings is that God’s great love for all of us, expressed through the Christ, is unchangeable. The Christ, the healing, saving power of divine Love, God – which appeared most clearly to human view in the life of Jesus – remains with us forever. Jesus explains the eternal nature of Christ in this arresting statement, “Before Abraham was, I am” (John 8:58), indicating that the Christ has always been present to guide us and has never been limited to the span of one human life.

Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, explains this clearly: “The advent of Jesus of Nazareth marked the first century of the Christian era, but the Christ is without beginning of years or end of days. Throughout all generations both before and after the Christian era, the Christ, as the spiritual idea, – the reflection of God, – has come with some measure of power and grace to all prepared to receive Christ, Truth” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 333).

When my mum passed away one spring, I’d been strongly comforted by the spiritual idea of God’s ceaseless love, enabling me to understand my unchanging relationship to my eternal Mother, God. It was so inspiring to see divine Love constantly being expressed in new ways by family and even strangers. And a full healing of grief came very quickly through prayer in Christian Science.

As Christmas that year approached, though, a number of friends warned me how difficult this first Christmas holiday would be without my mum. I understood their caring motives for mentioning this to me, but quietly affirmed that all the prayers of the previous months couldn’t be overturned for me or my family. The holiday time proved to be a happy, gentle one for us all.

However, a few days before Christmas I had fallen in a multistory parking garage and slid down a steep, concrete ramp, bouncing on the base of my spine. I got right up and went on my way praying to declare and understand my spiritual freedom from injury, rejoicing that I was able to carry on with the planned activity for that evening. There was no evidence of the fall.

However, a few days later I found myself in a great deal of pain whenever I stood up or sat down, and I was unable to walk far. It was a busy time of attending and hosting family parties, and I also had a large role in the services at my local Church of Christ, Scientist. I was praying for myself, but no physical progress was evident.

One night, as I turned in prayer to God, I asked for His Christ to show me the way. I was expecting to gain spiritual insights that would alert me to baseless mental suggestions, not coming from divine Mind, God, that lay behind the pain.

Suddenly, I remembered the comments of the well-meaning friends who’d expected me to be in mental anguish at this time, because of my mum’s absence. The action of Christ was uncovering a subtle underlying thought that I needed to refute. While I had genuinely been healed of the grief and anguish related to my mother’s passing, the expectancy that I would be in pain appeared to be trying to present itself in this different way.

Now knowing exactly what I needed to address, I prayerfully affirmed that I had already been healed of any association of “pain” with Christmas, and so I couldn’t possibly be bound by that expectation playing out, physically or mentally. I woke the next morning completely free from any pain or stiffness and have never suffered from this again.

It was a deep lesson for me that even when we face huge, seemingly turbulent changes, we can rely on the unchanging Christ to minister to us daily and remove from our thought and experience any ill effects from such changes.

If we are facing a lonely or difficult Christmas without our usual family celebrations, or with loved-ones missing this year, we can draw fresh inspiration from the ever present Christ, which Science and Health describes as ““God with us,” – a divine influence ever present in human consciousness” (p. xi). This divine influence brings healing to us through revealing God’s ever-present and unchanging love.

Some more great ideas! To hear a podcast exploring the universal nature of Christly love, please click through to the latest edition of Sentinel Watch on www.JSH-Online.com titled “Celebrating Christmas, cherishing the love of Christ.” There is no paywall for this podcast.

A message of love

A slowdown for safety

A look ahead

Thanks for starting the week with us. Check back tomorrow. We’ll have a story on what U.S. responses to current and future cyber intrusions could look like.

For updates on faster-moving stories, including the stimulus deal, jump over to our First Look page.