- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Biden’s no-win situation on the border

- On Tigray, Senator Coons’ mission signals Biden’s Africa challenges

- ‘Somebody cares’: How schools are helping with student well-being

- Bias against darker skin: Colorism gnaws in Britain’s minority communities

- Mideastern trio hopes that peace is in the air (and water)

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Can Black reparations be made practical? A first step by one city.

The headlines proclaimed Evanston, Illinois, the “first US city to make reparations to Black residents.”

Well, yes, and no.

The term “reparations” is often used to mean paying money to the descendants of enslaved people in the United States. But in this case, it’s about making amends for systemic racism in housing, also known as redlining.

Evanston officials voted Monday to distribute $10 million over the next 10 years to Black residents who suffered housing discrimination. They must either have lived in – or been a direct descendant of a Black person who lived in – Evanston from 1919 to 1969. Each qualifying household will receive up to $25,000 for home repairs, mortgage assistance, or a down payment on a mortgage. Distribution of funds will begin in the next few months.

The money will come mostly from taxes collected from sales of recreational marijuana and some private donations.

“It is the start,” Robin Rue Simmons, an Evanston alderman, told The New York Times. “It is the reckoning. We’re really proud as a city to be leading the nation toward repair and justice.”

Several other U.S. cities are considering similar steps, including Amherst, Massachusetts; Providence, Rhode Island; and Asheville, North Carolina.

Progress is often incremental. But once one runner breaks the 4-minute mile, the impossible becomes attainable (and more than 1,550 others have now done it). If one community can find a way to make amends for racial injustice, can others be far behind?

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Biden’s no-win situation on the border

The migrant crisis on the U.S.-Mexico border has emerged as an early test of the Biden administration’s leadership. So far, it appears unprepared.

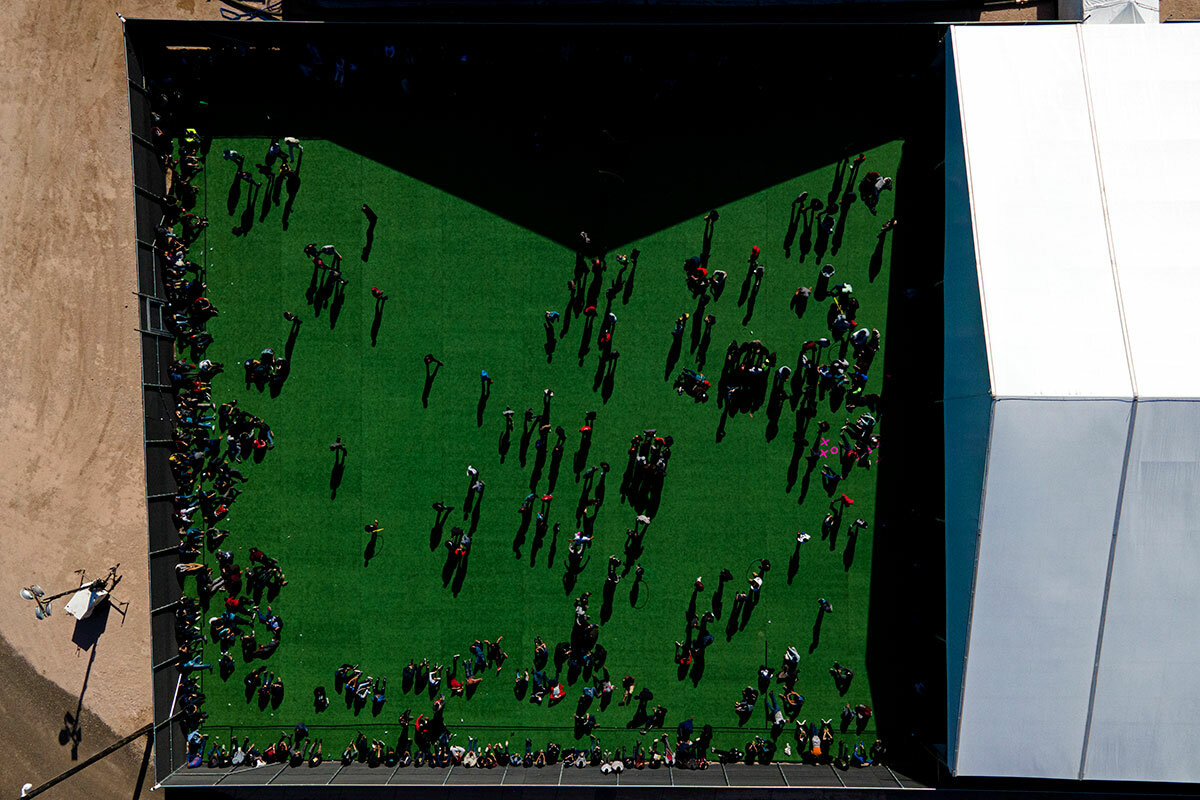

The images are arresting. Young migrants, most appearing to be teenagers, crowd into makeshift Border Patrol facilities in the town of Donna, Texas, not far from Mexico. Many are lying on floor mats under foil blankets.

On Tuesday, the day after Democratic Rep. Henry Cuellar of Texas released the photos, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection agency put out its own pictures depicting scenes of young migrants at cramped processing facilities near the U.S.-Mexico border.

It was a stark example of a new administration – one that promised “transparency” on Day One – responding to pressure to be more forthcoming about a bad, burgeoning situation. Congressional delegations from both parties have visited the border. President Joe Biden says he’ll visit soon. And his administration, under fire for limiting press access to the border – citing privacy and public health concerns – has promised more access. Details were still being finalized, White House press secretary Jen Psaki said Monday.

For now, the Biden team is working the problem from multiple angles: stabilize the situation on the border and with relevant governments in the region. And on Wednesday Mr. Biden announced that Vice President Kamala Harris will lead the administration efforts with Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras – in helping them stem migration at the southern border.

Biden’s no-win situation on the border

The images are arresting. Young migrants, most appearing to be teenagers, crowd into makeshift Border Patrol facilities in the town of Donna, Texas, not far from Mexico. Many are lying on floor mats under foil blankets.

On Tuesday, the day after Democratic Rep. Henry Cuellar of Texas released the photos, the U.S. Customs and Border Protection agency put out its own pictures depicting scenes of young migrants at cramped processing facilities near the U.S.-Mexico border.

It was a stark example of a new administration – one that promised “transparency” on Day One – responding to pressure to be more forthcoming about a bad, burgeoning situation. Congressional delegations from both parties have visited the border. President Joe Biden says he’ll visit soon. And his administration – under fire for limiting press access to the border, citing privacy and public health concerns – has promised more access. Details were still being finalized, White House press secretary Jen Psaki said Monday.

Two months into his presidency, President Biden retains majority job approval by the American public, after gaining passage of his popular $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief package. Yet the border issue has emerged as a major policy and public relations challenge. The Biden team is trying a range of steps, including diplomatic visits this week, to seek short- and long-term solutions. Yet, after years when his own party has billed itself as ready to address this issue with a blend of compassion and wisdom, it’s a challenge for which the new administration has seemed surprisingly flat-footed in its early efforts.

“That the campaign, then the transition team, and now the White House did not prepare significantly for this is quite shocking,” says John Hudak of the Center for Effective Public Management at the Brookings Institution.

The high political stakes are already becoming clear. Support for a key element of his immigration reform bill – a pathway to citizenship for the nation’s 11 million unauthorized immigrants – has plummeted, according to a Politico/Morning Consult poll. Some 43% of voters favor the provision, down 14 percentage points since January. More broadly, fully half of U.S. registered voters call the border situation a “crisis.”

Mr. Hudak notes that Democrats and immigration advocates had long complained about Trump administration actions on the border, including construction of the wall and the family separation policy. And a surge in immigrants at the border should not have come as a surprise. Take Mr. Biden’s election, his friendlier posture toward immigrants, and a reviving U.S. economy as the vaccination program rolls out: All of that, Mr. Hudak says, suggests that there would be an increase in the flows of immigrants.

Effects of a truncated transition

Theresa Cardinal Brown, managing director of immigration and cross-border policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center, cautions against judging too harshly. The Biden team had a truncated transition from the Trump administration, and is still getting its people in place in relevant agencies, relying for now on career employees in key leadership positions before nominees are confirmed.

But she agrees that the Biden transition team had to have thought a border surge might happen. And, she adds, working toward long-term solutions can take place in the context of addressing the short-term problem.

Using the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, to find facilities for short-term housing of migrants “is great in the short term, then you need to invest long term in facilities that you keep even if the numbers go down,” she says.

The real issue, Ms. Brown notes, isn’t the number of people showing up at the border; it’s who’s showing up. The trend toward more families and unaccompanied children is relatively new. The system at the border was built when most of the arrivals were adult Mexican men seeking work, not asylum.

“Remember, we have reduced capacity in the system,” Ms. Brown says. That’s because of COVID and because the Trump administration had reduced the number of facilities after implementing other asylum prevention mechanisms.

A year ago, when the pandemic started, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention invoked a provision known as Title 42, which allows the government to reject asylum-seekers at the border. The Biden administration has kept Title 42 active, but is allowing unaccompanied minors to remain in the U.S. on humanitarian grounds.

That exception has sent a signal to would-be migrants that making the trek north may be worth the risk.

For President Biden, it’s a no-win situation. His more welcoming posture toward migrants – particularly minors – is in keeping with his own philosophy as well as the leftward shift of the Democratic Party since his time as vice president, when then-President Barack Obama was dubbed “deporter in chief.”

But Mr. Biden has also made himself politically vulnerable ahead of both the 2022 midterms, when Democratic control of Congress is at stake, and even potentially the 2024 presidential election. Immigration was the founding issue of Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign, and either Mr. Trump himself or his successor, if he doesn’t run, could well exploit Mr. Biden’s handling of the border if the problem isn’t stabilized.

“It’s the issue that can usher any opponent of this administration into office,” says James Carafano, vice president of national security and foreign policy studies at the Heritage Foundation.

For now, the Biden team is working the problem from multiple angles: stabilize the situation on the border and with relevant governments in the region. Roberta Jacobson, special assistant to the president and coordinator for the southwest border, and Juan Gonzalez, special assistant to the president and senior director for the Western Hemisphere, traveled to Mexico this week for meetings with government officials. Mr. Gonzalez then headed on to Guatemala.

The meetings were aimed at addressing ways to stop migrants from heading north, plus strategies for addressing the root causes of migration in the home countries, such as violence and poor economic prospects.

Vice president’s new role

In Washington, Mr. Biden announced Wednesday that Vice President Kamala Harris will lead the administration efforts with Mexico and the so-called Northern Triangle countries – El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras – in helping them stem migration at the southern border. He made the statement at a meeting with his Homeland Security and Health secretaries and other immigration advisers. It’s Mr. Biden’s first specific assignment for Vice President Harris, a signal of its importance.

Mr. Biden and his team have stated repeatedly in recent days that now is not the time to head for the United States. The U.S. has also worked to get the message out through social media, TV, and radio throughout Central America and Brazil. But it’s not clear how effective such messages can be.

“You have people facing really tragic situations in their home countries,” says Mr. Hudak, “if you’re facing a regime that’s committing political violence, or you’re facing starvation, or criminal enterprises that are dominating cities.”

“Joe Biden saying, ‘Don’t come,’ is important,” he says, “but the administration has to be realistic about whether that message is actually going to carry weight – and frankly, whether the individuals who are considering immigration are even going to hear that message.”

On Tigray, Senator Coons’ mission signals Biden’s Africa challenges

We look at why Delaware Sen. Chris Coons may be uniquely positioned to build trust and bring U.S. influence to bear in a complex Ethiopian conflict.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In recent years, Ethiopia had emerged as a bright spot in an advancing Africa. The prime minister was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 for committing to build a democracy through dialogue. But since November, that image of progress has been shattered by the conflict in the country’s Tigray region. In February, the U.S. concluded that the Ethiopian government was carrying out a campaign of ethnic cleansing there.

Over the weekend, Sen. Chris Coons, a close friend of President Joe Biden’s with a decadeslong interest in Africa, met with Ethiopia’s senior leaders to deliver a message: The United States won’t simply ignore democratic backsliding and human rights abuses among African partners.

Many experts say they are heartened by the message the Coons mission delivers about renewed U.S. attention to Africa. But a sense of relief is attenuated, some say, by the reality that the U.S. has a lot of ground to make up.

Michael Rubin, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, says, “Biden is doing the right thing being proactive on this issue so quickly, and I think the prestige Coons brings into it as someone who has the president’s ear can only be helpful, but we’re still late to the game.”

On Tigray, Senator Coons’ mission signals Biden’s Africa challenges

When Chris Coons met with Ethiopia’s senior leaders in Addis Ababa over the weekend at the behest of the Biden administration, the Delaware senator wasn’t there just because he’s a close friend of the president’s. In Africa discussing complex issues – from democratic governance and minority rights to regional powder kegs – Senator Coons was in his element.

His assignment in Ethiopia: to convey the administration’s deepening concerns about what it describes as “ethnic cleansing” in the Horn of Africa country’s Tigray region.

As a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and former occupant of then President-elect Joe Biden’s A-list of secretary of state candidates, Senator Coons already had enough going for him right there to be tapped for the Ethiopia mission.

Those qualifications alone made him a good candidate for the broader task of signaling that a new team in Washington intends to raise attention to African issues from the low level they’d fallen to over the past decade, especially under the Trump administration.

Among the senator’s messages: The United States won’t simply ignore democratic backsliding and human rights abuses among African partners.

Moreover Ethiopia, with its particularly high level of Chinese investment, seems a natural focal point for President Biden’s and Senator Coons’ shared concerns over aspects of China’s aggressive and self-interested international development model.

Long interest in Africa

But what made Mr. Coons even more of a natural is a decadeslong interest in African issues broadly, and in matters of democratization and human rights particularly, in the rich but challenging context of the continent’s ethnic, tribal, and religious diversity – complex issues at play to varying degrees in the Tigray conflict.

As a college student in the 1980s, Mr. Coons spent a semester at the University of Nairobi in Kenya, immersing himself in Africans’ struggles for freedom and democracy. After graduation, he returned to Africa to work with Anglican Bishop Desmond Tutu and the South African Council of Churches in the anti-apartheid movement.

It was during that experience that Nelson Mandela became one of his heroes.

Back in Delaware in the 1990s, the lawyer and Yale Divinity School graduate gave sermons in Presbyterian churches on the evils of the apartheid system.

And then as a U.S. senator – elected in 2010 to fill the seat vacated by Mr. Biden when he became vice president – Mr. Coons made African issues one of his areas of focus.

“Senator Coons has been very active in the Senate on Africa issues and Africa policy, perhaps the most active of all the senators,” says Tom Sheehy, a former staff director for the House Committee on Foreign Affairs.

Signals at hearing

Recalling how the Delaware senator organized his questioning of Antony Blinken at his confirmation hearing for secretary of state in January, Mr. Sheehy says Mr. Coons revealed a lot about his priorities when he zeroed in on Ethiopia.

“Senators are very aware that they need to make good use of their limited time at high-profile hearings like that,” says Mr. Sheehy, now a distinguished fellow focusing on conflict resolution in Africa at the U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP) in Washington. “Coons could have asked him about a hundred other conflicts, but when he focused on Ethiopia, it was a clear indication of his interests.”

Ethiopia had emerged over recent years as a particular bright spot in an advancing Africa, with a booming economy and expanding middle class. The country’s leader since 2018, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 for returning peace to a country on the brink of ethnic warfare and for committing to build a democracy through dialogue.

But that image of progress and reconciliation has been shattered by the conflict in the country’s Tigray region. Since November, government forces and affiliated militias have been battling forces of the regional ruling party, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front – the political power that ruled Ethiopia for three decades before Mr. Abiy rose to power.

In February, the U.S. concluded that the Ethiopian government was carrying out a campaign of ethnic cleansing in Tigray, destroying entire villages and displacing thousands of ethnic Tigrayans. Many of the displaced have fled into neighboring Eritrea, where hundreds have been massacred, according to human rights organizations; or to Sudan, sparking tensions with the Sudanese government.

Ground to make up

Many Africa specialists in the U.S. say they are heartened by the message the Coons mission to Ethiopia delivers about renewed U.S. attention to Africa. But a sense of relief is attenuated, some say, by the reality that the U.S. has a lot of ground to make up, particularly in Ethiopia.

“Biden is doing the right thing being proactive on this issue so quickly, and I think the prestige Coons brings into it as someone who has the president’s ear can only be helpful, but we’re still late to the game,” says Michael Rubin, a resident scholar specializing in the Middle East and the Horn of Africa at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) in Washington.

Noting the dangers the Ethiopian government’s Tigray campaign risks igniting in a country organized by ethnicity-based regions, Mr. Rubin adds, “I’m afraid the Pandora’s box has already been opened.”

Add to the mix the tensions Ethiopia has sown with its neighbors, including Sudan, with its enormous hydropower project, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, and some experts see the makings of a broader regional conflict in the Horn of Africa.

Mr. Sheehy of USIP says that as encouraging as the Coons mission was in his eyes, “the key to progress in Ethiopia is going to be the follow-up.” Adding that the U.S. “needs to keep a dialogue going,” he says he’s encouraged by rumblings suggesting Mr. Biden will soon appoint an envoy for the Horn of Africa.

Indeed, speculation is already centered on seasoned diplomat and recent senior U.N. political adviser Jeffrey Feltman for the new post.

A bipartisan Africa policy

Both Mr. Sheehy and AEI’s Mr. Rubin say another encouraging feature in the Coons mission is that it suggests President Biden’s interest in working with Congress and building a bipartisan foreign policy. Mr. Coons is known for his efforts to work across the aisle with Republican colleagues.

For Mr. Rubin, that means the U.S. could again have the makings of a bipartisan Africa policy akin to the one developed by President George W. Bush. With bipartisan backing, he says, President Bush helped resolve the Darfur conflict in Sudan with his naming of retired Sen. John Danforth as his Darfur envoy, and he launched the hugely successful President’s Emergency Program for AIDS Relief, or PEPFAR, which was instrumental in helping Africa manage the AIDS crisis.

But what worries Mr. Rubin is that the Biden team may be about to discover, in Ethiopia and elsewhere, that a reengaged America may no longer have the influence and dominance that U.S. diplomacy once did.

Indeed, local reporting following Senator Coons’ Addis Ababa meetings suggested government officials matched the American delegation’s firmness. Foreign Ministry spokesperson Dina Mufi said the conversation helped “the friendly United States government ... better understand” what the Ethiopian government considers a “law enforcement operation” in Tigray.

“Domestic matters are Ethiopian matters and sovereign matters,” Mr. Dina said.

Mr. Rubin notes, for example, that China financed Addis Ababa’s new metro system and scores of other recent developments. He says Prime Minister Abiy “could say, ‘We’re not going to pay attention to you because you’re not that important to us anymore.’”

And that, he says, is “a wake-up call Biden is going to get all over the world, waking up ... to the realization we don’t have the power and leverage we once did.”

A deeper look

‘Somebody cares’: How schools are helping with student well-being

We looked at how teachers are helping students returning to classrooms to “stress bust,” to erase pandemic-related anxiety and depression that can undermine learning.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

As elementary students have returned to classrooms in St. Paul, Minnesota, in recent weeks, staff have noticed changes: lagging social skills, decreased academic stamina, and problems staying in chairs.

“We can’t just bring them back to school and pour in math problems without giving them time and space to process what’s going on,” says Susan Arvidson, who trains school counselors for St. Paul Public Schools.

A year after buildings shuttered in response to the coronavirus pandemic, educators are increasingly vocal about mental health challenges and meeting student wellness needs. More schools are incorporating discussions about well-being into the school day – whether in person or virtual – and are training staff and students to recognize distress and how to get help. Schools are also allowing students to take the lead in delivering support and instruction. Educators hope the efforts will offer lifelong support.

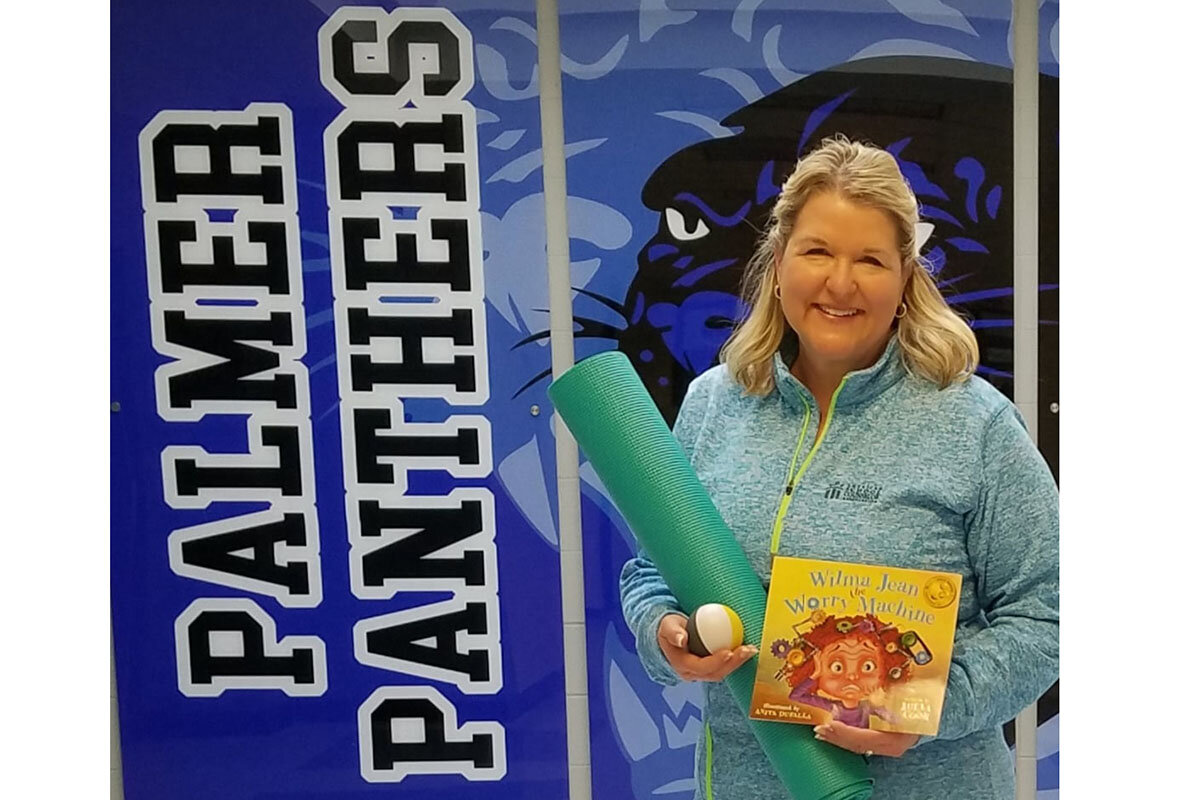

“Whatever resonates with them and helps them decompress after a long day of remote learning or school, that’s what we really encourage,” says Barbara Truluck, a counselor at Palmer Middle School in Kennesaw, Georgia. “It’s helping them now, but also in life down the road.”

This story was supported by a grant from the Solutions Journalism Network.

‘Somebody cares’: How schools are helping with student well-being

When middle school counselor Barbara Truluck started a small grief-support group last school year, she had no idea that a global pandemic was imminent and that some of her students would lose family members.

Now she’s grateful the Healing Hearts Grief Group was already established. She is offering more sessions this year, based on demand, with the close-knit students meeting in person and remotely to share memories of their loved ones and process their feelings.

“This program has helped me open up,” wrote an eighth grade student to the Monitor. “It released any pain & anger that I held against anyone. Yes, I still hurt from time to time. BUT it’s what happens.”

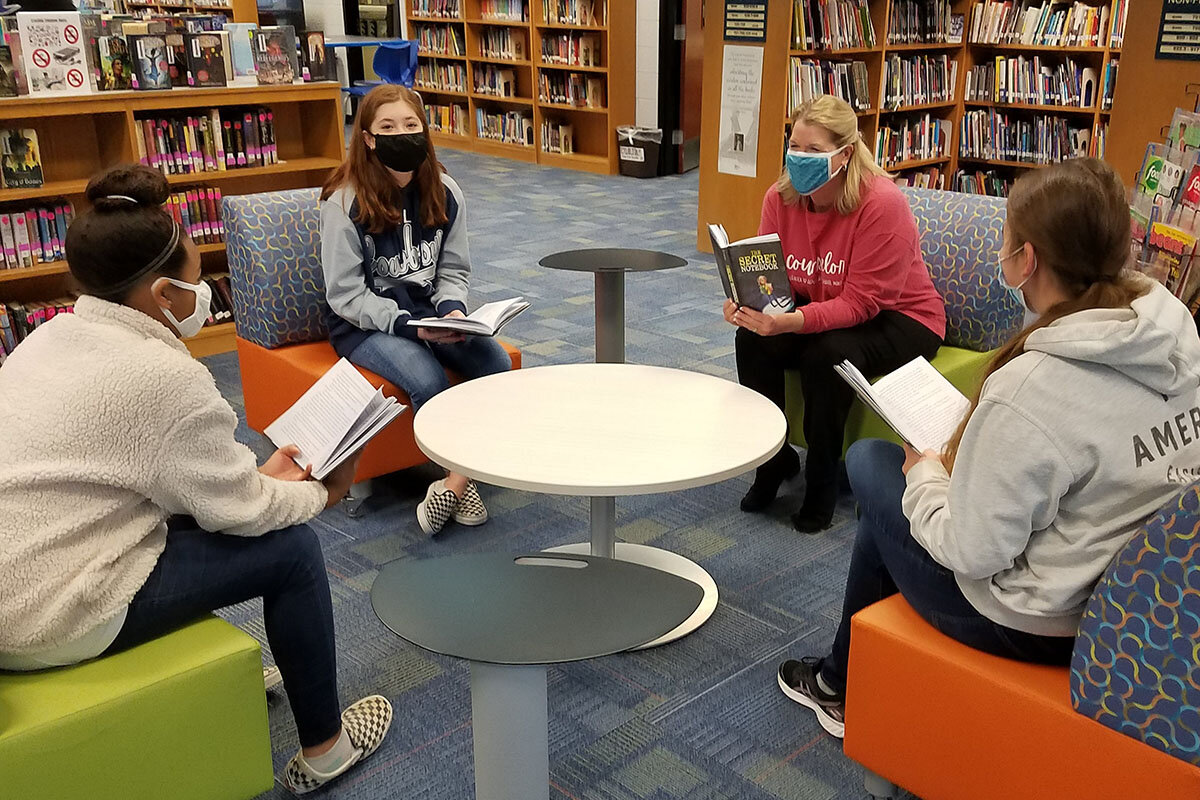

The group is one way that Ms. Truluck, a counselor at Palmer Middle School in Kennesaw, Georgia, reaches out to students experiencing heightened loneliness or other mental health concerns stemming from changes to their lives in the past year. She and her colleagues also run a popular stress busters group, host a book club, and run virtual lunch sessions featuring games and music.

“Anything that facilitates connections with students” is critical this year, says Ms. Truluck, who was selected as the 2019 Georgia school counselor of the year.

A year after schools shuttered in response to the coronavirus pandemic, educators are increasingly vocal about mental health challenges and meeting student wellness needs. More schools are incorporating discussions about well-being into the school day and are training staff and students to recognize distress and how to get help. Leaders are making tough choices, like giving up buying new furniture in order to hire more social workers. Schools are also offering students some agency – allowing them to take the lead in delivering support and instruction. Educators hope the efforts will offer lifelong support.

“I think there will be a resiliency out of this generation of students who have lived through this,” says Susan Arvidson, a lead school counselor for St. Paul Public Schools in Minnesota. “That will be their strength, to lead us in the next generation because they’ve been through something so difficult.”

Ongoing research reflects how students are faring. A survey released in January by YouthTruth, a nonprofit, found that older elementary and secondary students identified depression, anxiety, and stress as their top obstacles to learning. Students identifying as Black or African American, or as Hispanic or Latinx, reported more obstacles to learning. Last week, a survey from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that nearly a quarter of parents whose children (ages 5 to 12) are learning remotely or through hybrid instruction report their children are experiencing worsened mental or emotional health since the pandemic began. Just over 15% of parents with students in school full time reported their children had worse mental health.

Before the pandemic, momentum existed in some places to address student mental health needs, with calls from politicians and educators growing now. State legislatures in Texas and Michigan are considering bills aimed at student wellness – requiring mental health classes and increasing the number of counselors, respectively. And Chicago Public Schools announced on Monday it will spend $24 million over the next three years on an initiative that will bring a behavioral health team to each school to address student, staff, and family wellness.

Federal funds for education in the three COVID-19 stimulus relief packages passed in the past year stipulate that the money can be used by K-12 districts for student mental health support. The most recent American Rescue Plan provides $122 billion for public K-12 education, with state and local school districts given flexibility on how much they choose to spend on mental health.

Hiring more staff to help with everything from leading small groups to finding missing students is often a priority for districts. The average school counselor in the United States is responsible for 450 students – well above the American School Counselor Association (ASCA) recommendation of 1 to 250.

Some districts and individual schools have been addressing shortages throughout the pandemic: Dallas Independent School District hired more school mental health professionals this past year and College Achieve Asbury, a charter school in New Jersey, sacrificed new furniture in order to hire more social workers.

More push to teach directly

Along with adding staff, schools have also been considering how to build lessons that support well-being into the school day. Incorporating social and emotional learning in classrooms has been a trend for years, but educators appear to be turning to such practices more during the pandemic. In a fall 2020 ASCA survey, 63% of school counselors reported spending more time on social and emotional learning over the past year.

The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning – the organization that defined social and emotional learning more than 20 years ago – has received an increase in requests for support from districts and states since the pandemic began, says Karen VanAusdal, senior director of practice.

Social and emotional learning isn’t intended to take time away from academics, says Ms. VanAusdal, but is grounded in studies showing learning is more effective when students are self-aware, can regulate themselves, and have strong relationships with teachers and peers.

“If you just ... double down and spend more time on math and reading, it won’t accelerate the learning as it would if you were integrating social-emotional and academic learning together,” she says.

Some observers say schools need to be more focused on measuring and tracking student wellness. An analysis of 477 school districts in the fall of 2020 by the Center on Reinventing Public Education found that while 66% of the schools’ remote learning and reopening plans mentioned students’ social and emotional well-being, only 7% had a systemwide approach to collecting data on student well-being.

At Ridgeview Charter Middle School in Sandy Springs, Georgia, just north of Atlanta, administrators chose to add a formal social and emotional program this school year. Counselors work with teachers to deliver lessons on topics like perseverance and problem-solving.

“It’s our job to do everything we can to support that student so they are ready to learn,” says Kathleen McCaffrey, an assistant principal at the school.

In Minnesota, St. Paul Public Schools has been bringing students back to the classroom since February. Elementary students, the first to return, were excited to see their friends, says Ms. Arvidson, who works at the district level training school counselors. But staff are spotting students with lagging social skills, decreased academic stamina, and problems staying in chairs.

“We can’t just bring them back to school and pour in math problems without giving them time and space to process what’s going on,” she says.

“Somebody cares”

Ms. Truluck, the counselor at Palmer Middle School in Georgia, found student emotional health improved after school resumed in person five days a week last fall. But about 35% of students remain learning virtually and Ms. Truluck stays especially attuned to their needs, since many say they miss seeing friends and teachers in person. She arranges small group sessions with multiple computers and cameras so that the students in person and remotely can see each other well.

At the end of last school year, 90% of students who participated in the school’s stress busters group reported decreased stress levels from learning coping skills, according to Ms. Truluck – and their school attendance levels increased.

“Seeing my counselor and talking helps me relax and feel like somebody cares about what I feel like,” wrote one student about the stress busters group this year in a handwritten note.

Middle school populations can sometimes be more vulnerable, given where students are in their transition to adulthood. Some middle schools are letting them lead the conversations about mental health. In Jacksonville, Florida, students asked to make a short video after seeing other materials created by the district’s central office and realizing they might be able to better connect with their peers. In the recording, filmed and scripted by students at Mandarin Middle School, kids gaze into the camera and cheerfully offer their “top 10 stress busting tips.”

One student advises her peers to decrease negative self-talk: “‘My life will never get better’ could be transformed into ‘I may feel pressured now, but things can get better if I work at it and ask for help,’” she says.

The video, produced just prior to the pandemic, was shown at all middle schools throughout Duval County Public Schools last spring. It is part of a Wellness Wednesdays initiative started in 2019 – the year after the school shooting in Parkland, Florida – in which all middle and high school classes pause once a month for 30 minutes of mental health instruction. The video will be shown again to all sixth grade students this spring, with student conversations afterward.

The district has seen a slight increase in depression and anxiety diagnoses and a rise in reports of suicidal thoughts or attempts since the pandemic began, says Katrina Taylor, director of school behavioral health.

Duval County Public Schools has provided youth mental health first aid training to 4,000 out of 13,000 staff members so they can assess student risk of suicide, with plans to eventually expand the training to all employees. The district also plans to keep offering virtual mental health counseling sessions over the summer so school therapists can connect with students who travel.

“Now that we have the virtual tools, they can be at auntie’s house in Atlanta and we can still provide those services,” says Ms. Taylor.

Parents need help, too

Schools can’t help students without working with parents as partners, many educators say, and the pandemic has bound teachers and parents closer together than ever before.

Even before the pandemic, school staff often worked with parents to let them know that mental health struggles aren’t a poor reflection of their parenting, says Ms. Taylor. Her Florida district sent parents of elementary-aged children a book of calming techniques, like breathing exercises, that parents can do at home with their children.

Brad Glenn, a parent of a seventh grade student at Ridgeview Charter Middle School in Georgia and an elected member of the school’s governing council, says school administrators listened to parents and took student mental health into consideration when they changed their remote learning schedule earlier in the year to give students more time off their screens.

Now, he’s working with the school district to try and find a safe way to run intramural athletics to replace a canceled sports season. “Now more than ever it seems so important to get out, get a little physical exercise. You get that mental exercise and the social and emotional, too,” he says.

For Ms. Truluck, the counselor, this year has reinforced why she enjoys teaching coping skills to her students. She guides students to recognize their interests and discover what helps them feel calm, activities such as journaling, sports, art or music therapy, or spending time with family.

“Whatever resonates with them and helps them decompress after a long day of remote learning or school, that’s what we really encourage, so they can find what works for them,” she says. “It’s helping them now, but also in life down the road.”

This story was supported by a grant from the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to reporting about responses to social problems.

Bias against darker skin: Colorism gnaws in Britain’s minority communities

Oprah Winfrey’s interview with Meghan, the Duchess of Sussex, has reignited discussion about skin-color prejudice. We look at how British communities of color are revisiting their own concepts of beauty as well as perceptions of socioeconomic status based on skin color.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Shafi Musaddique Correspondent

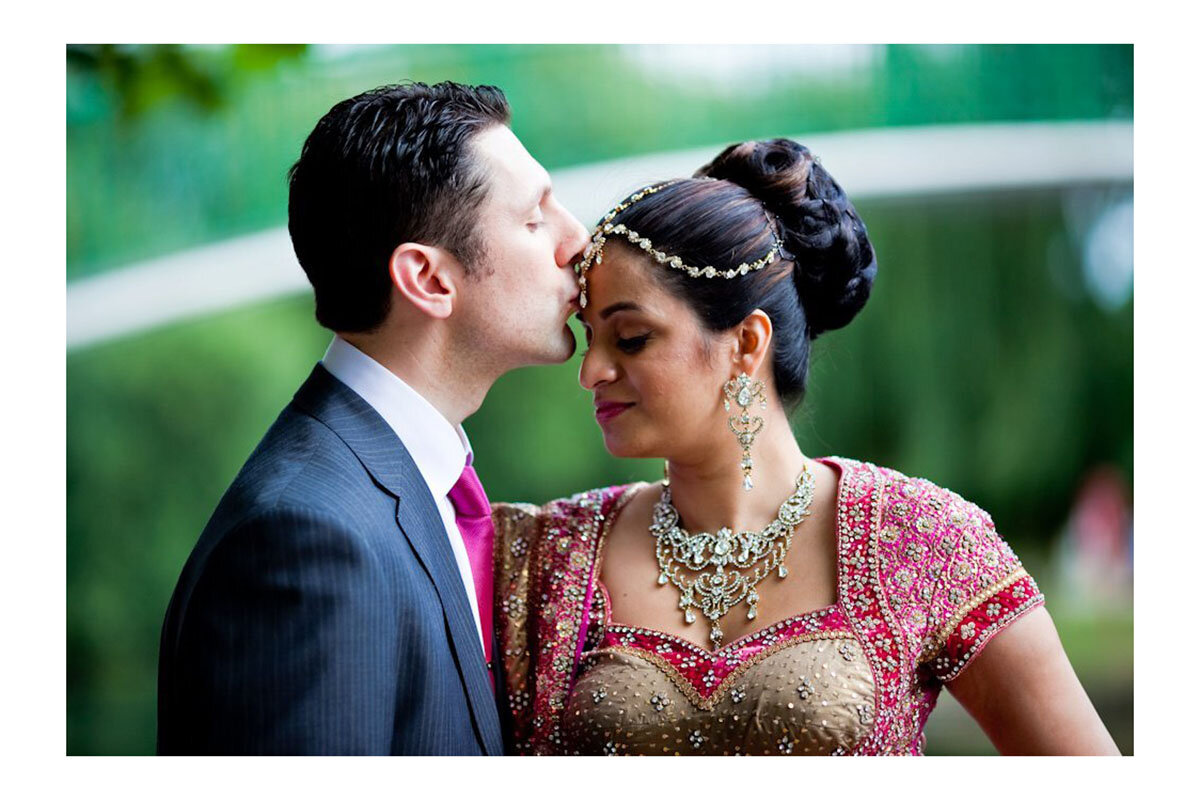

When Meghan, the Duchess of Sussex, told Oprah Winfrey that a member of the British monarchy expressed “concerns” about the skin color of their then-unborn son, Archie, it struck home for many Britons of Afro-Caribbean and South Asian descent. For even within those communities, there is a form of discrimination distinct from racism and specifically focused against darker skin tones: colorism.

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Alice Walker first coined the term “colorism,” describing it as “prejudicial or preferential treatment of same-race people based solely on their colour.” For many Black and Asian Britons, it is most commonly experienced at home through the phrase, “Don’t go in the sun.”

Preferences for “lighter” skin manifest in myriad pressures: from discriminatory practices by border officials at U.K. airports to damaging tropes that sometimes limit marriage prospects for women in particular. But activists are concentrating their efforts within their own communities, where they see the more pressing need.

“It’s something we need to deal with in non-white communities before it really becomes an issue that white communities can come to terms with,” says Anitha Mohanan, a writer and editor at Dark Hues Magazine. “Our families, without realizing, perpetuate colorism.”

Bias against darker skin: Colorism gnaws in Britain’s minority communities

Whenever Samantha Symonds went to visit extended family in Singapore, she was always called “the English one.” Her Singaporean mother would regularly praise her for having “lovely tofu skin.” What they had all really meant, as Ms. Symonds recalls, was that she was “the pale one” in the family, loved and overly cherished for her fair complexion.

That sort of societal pressure is colorism, a form of discrimination distinct from racism and specifically focused against darker skin tones. And unusually, it is often born from within communities of color, and perpetuated by wider societal norms and habits.

The debate around what colorism is, and how it is perpetuated, has opened up in Britain following claims by Prince Harry and Meghan, the Duchess of Sussex, in an interview with Oprah Winfrey watched by a record-breaking 11.4 million people in the U.K., that a member of the British monarchy expressed “concerns” about the skin color of their then-unborn son, Archie.

While some in Britain’s Afro-Caribbean and South Asian descent communities are wrestling with how to address colorism, the efforts are relatively new, and lag behind places like the United States, they say. While colorism can be found throughout society, they are concentrating their efforts within their own communities, where they see the more pressing need, before trying to branch out into broader activism.

“It’s something we need to deal with in non-white communities before it really becomes an issue that white communities can come to terms with,” says Anitha Mohanan, a writer and editor at Dark Hues Magazine, an online publication that aims to give greater representation and celebration of dark skin. “Our families, without realizing, perpetuate colorism.”

Colorism at home

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Alice Walker first coined the term “colorism,” describing it as “prejudicial or preferential treatment of same-race people based solely on their colour” in her 1982 essay, “In Search of Our Mothers’ Garden.” For many Black and Asian Britons, it is most commonly experienced at home through the phrase, “Don’t go in the sun.”

Ms. Symonds says she only became “acutely aware” of colorism some three years ago. Having relocated to the sunny coast of Thailand to train as a diving instructor, she had returned to the U.K. briefly for a cousin’s wedding – only to cause a stir among her family about her newfound tan.

“My mom was aghast; other family members asked, ‘What have you done to your skin?’” she says, now back home in Birmingham.

“‘Tofu skin’ stuck in my mind, and I thought, wow, this really is a big deal to you. My friends when they see me with a Thailand tan are jealous. I was quite proud of it, so it was a strange situation being in the middle of it.”

From her experiences in both Britain and Southeast Asia, Ms. Symonds eventually learned how her tan suggested a lower socioeconomic status; the idea being that darker skin meant association with working-class jobs traditionally done in the heat of the sun. Prejudices informed by caste systems and the deeply embedded influence of colonialism, particularly for South Asian countries formerly under British rule, continue to play a role in diaspora communities some two, or three, generations since mass migration into Britain.

Preferences for “lighter” skin manifest in myriad pressures: from discriminatory practices by border officials at U.K. airports to damaging tropes that sometimes limit marriage prospects for women in particular.

Sunita Thind, a British Punjabi author of published poetry exploring British Indian identity, found having darker skin limited her opportunities from a young age. As a model in her teenage years, modeling agencies had glanced over her application “saying they’ve got someone who looks like me, but is fairer.” The practice for favoring lighter-skin models, she says, continues to this day.

“I don’t think I knew the term colorism until only a few years ago,” says Ms. Mohanan of Dark Hues. “It’s not spoken about in wider society. It’s not talked about on the same level as racism.”

Racism, she says, is an issue that white people must actively take part in to end it. Colorism, on the other hand, “doesn’t really need the white community to be a part of that conversation in some ways.”

Eurocentric beauty standards

Still, the global beauty industry drives Eurocentric ideals that are rife among African and Asian diaspora communities. While the U.K. has banned skin-whitening creams domestically due to harmful ingredients such as mercury and steroids, they are still widely marketed in parts of India, Thailand, Malaysia, and East Africa.

Unilever renamed its popular skin-whitening cream “Fair and Lovely” to “Glow and Lovely” amid the Black Lives Matter protests last year, though British Indian psychologist Natasha Tiwari says she’s “unconvinced” that “token gestures” will improve mental health.

Film industries in India, China, and some parts of Africa perpetuate Eurocentric beauty standards with the overuse of light-skinned actors. But so too do Western film productions; critics point to hit Netflix show “Bridgerton” as a recent example. Despite depicting interracial relationships in a period drama, light-skinned, mixed-race characters play lead roles with no visibility for darker-skinned actors.

For Tina Gohil, a Londoner with an Indian mother born in Kenya, colorism only arose in her adult life in an interracial relationship. She says a shift in tone occurred when her partner expressed reservations about potentially having darker-skinned children.

“It was a genuine concern of his. ... He said ‘I don’t think we can have kids because if they’re brown, people will think they’re not mine.’” She adds that discussions on skin tone require a degree of nuance and understanding regarding their context, as they are not necessarily about prejudice. That is dependent on who is speaking, and what exactly is said.

Ms. Symonds also believes that, while colorism is “awful,” “we shouldn’t overly demonize people” without understanding the context of comments about skin color. “Discussions about skin whitening are progressive and good ... but we could view it in the same way as Brits wanting to tan. Isn’t it crazy that it’s fashionable to get skin cancer and go tan on sun beds? You have to see it from all angles.”

Ms. Tiwari recommends people voice their concerns openly. “Say that it hurts your feelings, or that it is upsetting to you because you know it is hurtful to others.”

Slow changes

Organized activism against colorism can feel fragmented. Chizoba Itabor, co-founder of Dark Hues Magazine, says activism has until now been “segmented” in silos between different ethnicities. Her publication has provided a solution, bringing “conversations of colorism within Dark Hues ... between dark-skin Black and South Asian people.” Organized activism, she adds, helped forge safe spaces online for discussions to take place.

Ms. Mohanan hopes that the online magazine sheds new light on, and gives representation to, darker-skinned people of mixed-race backgrounds in particular. “The first thing people think of when discussing mixed race is white plus another race. But you can be two ethnic minorities like Kamala Harris, with dark skin – and that’s something not talked about.”

While there’s no one solution to ending colorism, both Ms. Mohanan and Ms. Thind say change starts when, for example, a lighter-skin actor steps down to give an opportunity to underrepresented people with darker skin tones.

“It’s the gatekeepers who need to be willing to give up some of that power to people that aren’t represented,” says Ms. Thind. “It’s going to be slow changes, but having people like Kamala Harris in power gives us hope.”

Editor's note: The story has been updated to correct the spelling of Ms. Mohanan's surname.

Mideastern trio hopes that peace is in the air (and water)

Peace is a journey. For this Middle East group, the initial footsteps begin with helping rivals build trust by collaborating on solving common environmental problems, such as water scarcity.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

For the Israeli, Palestinian, and Jordanian directors of EcoPeace Middle East, which promotes peace through environmental collaboration, a guiding truth is that nature and the environment care not at all about human-made boundaries.

The group’s successes include rehabilitating the Jordan River, establishing educational “ecoparks” in the Jordan Valley and along the Dead Sea, and developing wastewater systems in Jordan and the West Bank.

A lot of the staff’s time is taken up explaining why EcoPeace’s approach can be a win-win for sides used to viewing one another as adversaries. “We are a civil society organization who cares about the people on the ground,” says Nada Majdalani, the Palestinian director. “And, for us, it is important also to show that there’s a grassroots [movement] of people on the other side who care.”

Undergirding EcoPeace Middle East is the understanding that climate change can and should play a role promoting unity in the region. A climate-centered approach, says Gidon Bromberg, EcoPeace’s founder and Israeli director, “creates ... a common opportunity that links not only Israelis and Palestinians but gives further credence to why we need greater regional cooperation with Jordan and also the Gulf states.”

Mideastern trio hopes that peace is in the air (and water)

When Israeli environmentalist Gidon Bromberg looks out at the shimmering blue of the Mediterranean, he sees more than its beauty.

Among the complicated mix of images that emerges for him are the thousands of years of culture and exploration that traversed its waves and shoreline, and the damage inflicted by pollution, overdevelopment, and now the climate crisis.

He also sees a resource, one whose scarcity in this parched region has been fueling tensions and conflict since biblical times.

For Mr. Bromberg – Israeli director of EcoPeace Middle East, which promotes peace through environmental collaboration – and for his Palestinian and Jordanian colleagues, the need to protect all the bodies of water these neighbors share is a prime motivator.

And a guiding truth for them is that nature and the environment care not at all about human-made boundaries.

When, for example, raw sewage overflows from the Gaza Strip (where there is a shortage of sewage treatment plants) into the Mediterranean, it travels northeast with the currents toward Israel. Much of it reaches the coastal town of Ashkelon, home to a major desalination plant that has had to shut down several times as a result.

Common threat

Undergirding EcoPeace Middle East is the understanding that climate change can and should play a role promoting unity in the region. Instead of seeing regional stability “through the traditional lens of the peace process, it’s through the lens of the climate crisis that we all face,” Mr. Bromberg says.

A climate-centered approach, he says, “creates a different conversation, a conversation of a common threat, but also a common opportunity that links not only Israelis and Palestinians but gives further credence to why we need greater regional cooperation with Jordan and also the Gulf states.”

At a recent conference, EcoPeace launched an ambitious regional master plan called a Green Blue Deal for the Middle East. It outlines how an all-hands-on-deck approach to climate change could not only ensure enough water for everyone in the region, but also serve as a catalyst for building trust after years of diplomatic deadlock on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

“We live in one integrated ecosystem, and if we don’t start to understand that, we will all pay a heavy price due to climate change,” Mr. Bromberg told the conference.

EcoPeace Middle East is run by a team of about 50 Palestinians, Israelis, and Jordanians. Mr. Bromberg heads the office in Tel Aviv; Palestinian Nada Majdalani heads the office in Ramallah, West Bank; and Jordanian Yana Abu Taleb, the office in Amman, Jordan. It’s a single organization with equal board representation for each nationality.

Successes include rehabilitating the Jordan River by increasing its flow; training Israeli, Palestinian, and Jordanian students as grassroots leaders on shared environmental issues; establishing educational “ecoparks” in the Jordan Valley and along the Dead Sea; and developing wastewater systems in Jordan and the West Bank.

EcoPeace will be among the Israeli-Palestinian “People to People” initiatives to benefit from a $250 million allocation for Israeli-Palestinian peace-building efforts passed by Congress in late December.

Together, facing hostility

After years struggling together to make a dent in mindsets and outcomes for their respective societies, while facing a public that can often be hostile, the bond between EcoPeace’s three directors is especially close.

“Gidon and Nada are always there to give advice, to think things through together; they make me feel like I’m not alone,” says Ms. Abu Taleb. “We are there all the time to comfort one another.”

Ms. Majdalani, the newest team member, says of Mr. Bromberg, “Gidon gives me this ability to be always energetic – the momentum, the stamina, the excitement [are] all the time bringing new concepts, new ideas. He’s pushing forward our agenda to the max.”

She credits Ms. Abu Taleb for keeping the team focused. She’s always asking, she says, “How do we move forward? How do we make an impact?”

The backlash the two women face at home for working with Mr. Bromberg can be fierce. They are often called traitors by an anti-normalization movement that maintains that any Israeli-Palestinian contact that does not advocate resistance to Israeli occupation of Gaza and the West Bank gives the false impression that Israelis and Palestinians are operating as equals.

“It’s easier for people to see each other as enemies – to put these sensitive issues that we do share to the side,” says Ms. Abu Taleb.

A lot of the staff’s time is taken up explaining why EcoPeace’s approach can be a win-win for sides used to viewing one another as adversaries. “We are here to basically do what we can to prevent [environmental] catastrophes from happening,” says Ms. Majdalani. “We are a civil society organization who cares about the people on the ground. And, for us, it is important also to show that there’s a grassroots [movement] of people on the other side who care.”

When Mr. Bromberg founded the organization in 1994 in the wake of the Oslo Accord, he assumed cross-border organizations like this would become the norm. More than 26 years later, it remains the only organization of its kind.

Trading sunshine for seawater

In Jordan, Ms. Abu Taleb is trying to win support for one of the group’s most ambitious projects to date. It envisions converting the 365 days of sunlight beating down on Jordan’s desert into renewable energy that would be transferred to Israel and Gaza in exchange for desalinated seawater.

“Jordan will need more water to meet its needs for water security, and this is the most logical and economical way to do it,” says Ms. Abu Taleb. “We really want to see renewable energy cross borders, but we need the political will.”

But getting the authorities in Jordan to approve, she says, is not easy, given popular resistance to the idea of working with Israel.

Israel, a world leader in desalination technology, supplies most of its water needs for its homes and cities through its desalination plants. Gaza has one small desalination plant and plans to build a large-scale one.

Currently, water and energy dependence is a one-way street, with Jordan buying both water and natural gas from Israel.

“This is creating a backlash,” says Ms. Abu Taleb. “But our vision is that of healthy interdependencies which will definitely change things on the ground. It’s not easy ... but it’s the right way forward.”

Visit to the U.N.

In April 2019, the three EcoPeace directors traveled to New York to appear before the United Nations Security Council. They explained how new technologies provided a way to share water rather than fighting over it. They told stories of the human costs of not facing the common threat of water scarcity, including the death of a 5-year-old boy in Gaza after he came in contact with raw sewage that flowed into the sea.

When the directors finished giving their testimony, the Israeli and Palestinian ambassadors to the U.N., known for rarely agreeing on anything, praised their work and the example they were setting.

While he and his colleagues may still be dismissed as dreamers, Mr. Bromberg says, moments like this, and the headway they have made, make it feel like “we are seeing an adoption of that narrative we were told was impossible.”

To learn more about EcoPeace Middle East, visit www.ecopeaceme.org.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A police officer’s calmness in action

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Among the many heroes during the mass shooting in Boulder, Colorado, was Eric Talley, the first police officer to respond. With calmness and courage, he ran toward the danger inside King Soopers grocery store, taking action against a gunman to save the lives of others before being fatally shot himself. Officials praised him for different qualities that are essential during a volatile and violent crisis.

One insight on his character comes from a 2016 report describing an incident with a troubled young man during which the officer acted with patience and calm.

Police are trained to do many things, but perhaps one of the more necessary qualifications is staying calm. Calmness is so admired in police that the National Police Foundation conducted a study of it after the 2015 mass shooting in San Bernardino, California. The title said it all: “Bringing Calm to Chaos.”

Calmness is not the absence of fear but a very real antidote to fear. The best way to honor Officer Talley may lie beyond praising him. For anyone who wants to be prepared for a crisis, the best response lies in emulating the strength and affection behind his great calm.

A police officer’s calmness in action

Among the many heroes during the March 22 mass shooting in Boulder, Colorado, was Eric Talley, the first police officer to respond. With calmness and courage, he ran toward the danger inside King Soopers grocery store, taking action against a lone gunman to save the lives of others before being fatally shot himself, said Boulder Mayor Sam Weaver. Other officials praised Officer Talley for different qualities that are essential during a volatile and violent crisis.

“When the moment to act came, Officer Talley did not hesitate,” said President Joe Biden. Boulder police Chief Maris Herold described his possible motivations, saying the 10-year force veteran was “a very kind man” who loved his community. “He’s everything that policing deserves and needs,” she said.

One insight on Officer Talley’s character comes from a 2016 report describing an incident with a troubled young man. The man’s parents stated afterward, “[Our son] was combative when Officer Talley arrived. Officer Talley acted calmly and professionally and helped keep our son safe, despite our son’s aggressive behaviors.” They praised his understanding and patience in ridding their son of his immediate fears.

Police are trained to do many things, but perhaps one of the more necessary qualifications is staying calm. A community expects its officers to remain unruffled and stable whether they are facing an active shooter, standing in front of a riotous crowd, or deciding whether a suspect is holding a gun or a harmless object.

Calmness is so admired in police that the National Police Foundation, supported by the U.S. Justice Department, conducted a study of it after the 2015 mass shooting in San Bernardino, California.

The title said it all: “Bringing Calm to Chaos.”

The report details how police brought calm to victims during the incident, how they calmed the general public, and calmed each other, relying on trust, experience, training, and “a sincere concern for first responders and victims.”

Among the skills needed during a threatening situation are empathy, listening, and prudence. “The leadership necessary to manage even the smallest components of these events was critical not only to eliminating the threat but also to preventing additional casualties, informing the public, reducing fear in the community, and restoring calm,” the report stated.

Calmness is not the absence of fear but a very real antidote to fear. The best way to honor Officer Talley after the Boulder shooting may lie beyond praising him. For anyone who wants to be prepared for a crisis, the best response lies in emulating the strength and affection behind his great calm.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

While we wait

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

There isn’t anywhere that God-gifted grace, patience, and joy can’t be expressed – uplifting our outlook and experience even when it seems we’re in a waiting game for something good to happen.

While we wait

Whether you are at the DMV (Department of Motor Vehicles) or on hold about when the kids will be back in school, waiting can sometimes seem challenging. It suggests an absence or lack, because the thing you are waiting for doesn’t appear to be there or hasn’t happened yet. These days it seems there is a lot of waiting going on in many aspects of life.

Jazz icon Wynton Marsalis wrote and recorded “The Democracy! Suite” during the pandemic. Its first movement, which Mr. Marsalis said was inspired by frontline workers who have put their lives on the line during the pandemic, is titled “Be Present.” As Mr. Marsalis continues to perform onstage without an audience, he is clearly “being present” with perseverance and inspiration in creative ways. I find his example encouraging.

What if instead of getting caught up in what seems absent, we considered that even where that feeling of waiting is, nothing we truly need is missing? I’m not talking about visualizing a certain outcome or circumstance. What I mean is recognizing the unchanging presence of God, divine Love itself – tangibly feeling the limitless fullness of God’s present goodness as the reality, even when circumstances suggest we have to wait for something good to happen.

There’s a beautiful declaration in the Bible that I’ve found helpful in lessening anxious mental thumb-twiddling in such situations: “You reveal the path of life to me; in your presence is abundant joy; at your right hand are eternal pleasures” (Psalms 16:11, Christian Standard Bible). Through prayer, what appear to be waiting periods can actually be transformed into moments of openness to divine revelation.

Some time ago I felt I needed a refreshed sense of life, work, and relationships. You could call it a waiting period, because I sure felt as though I was waiting for a change.

As I had found helpful so many times before when faced with difficulty or uncertainty, I prayed – but not to ask God for a specific change in circumstance. I was praying to see the path forward that was already full of joy in God’s presence, and to be more aware of the permanent spiritual substance of everything in my life.

Christian Science, based on the Bible, teaches that God is Spirit and has created each of us spiritually. This means that qualities from God, good, such as purity, intelligence, and wisdom are the very substance of our real identity.

I looked for opportunities to express these qualities even in the simplest things I enjoyed in my life, such as bike riding and jazz. And I realized that the vitality and creativity of these simple enjoyments could be expressed even during challenges at work and within relationships. There isn’t anywhere that Spirit-gifted grace, patience, and joy can’t be expressed in order to glorify God.

Not only did these ideas help me feel near to God, but they showed me that spiritual qualities and their expression are my actual life, no matter what my circumstances look like. After about six months of this steady prayer and practice of the ideas that were awakening in me, I really felt them governing and directing my life. I no longer felt stuck in a waiting game. And soon my experience did take on an entirely new direction that included marriage, a new culture and country, and other new opportunities to express God-given qualities and abilities.

The discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, wrote a poem called “Mother’s Evening Prayer” that has also been set to music in the “Christian Science Hymnal.” The first two lines put in a nutshell the ideas that so changed my thought: “O gentle presence, peace and joy and power; / O Life divine, that owns each waiting hour...” (“Poems,” p. 4).

As we recognize the presence of God’s blessings and our inseparability from that divine goodness, our outlook can be uplifted instantly. So what are we waiting for?

A message of love

Repair in midair

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a story about what different nations can teach us about balancing civil liberties during a pandemic.