- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- US public wants gun laws. A Senate tradition is one big hurdle.

- To fight pandemic, people gave up liberties. Will they get them back?

- ‘The status quo is not working’: Mountain town reckons with homelessness

- Millennials bore COVID’s economic brunt. Will boomers help them out?

- Beyond the Underground Railroad: Reckoning with Canada’s slavery history

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

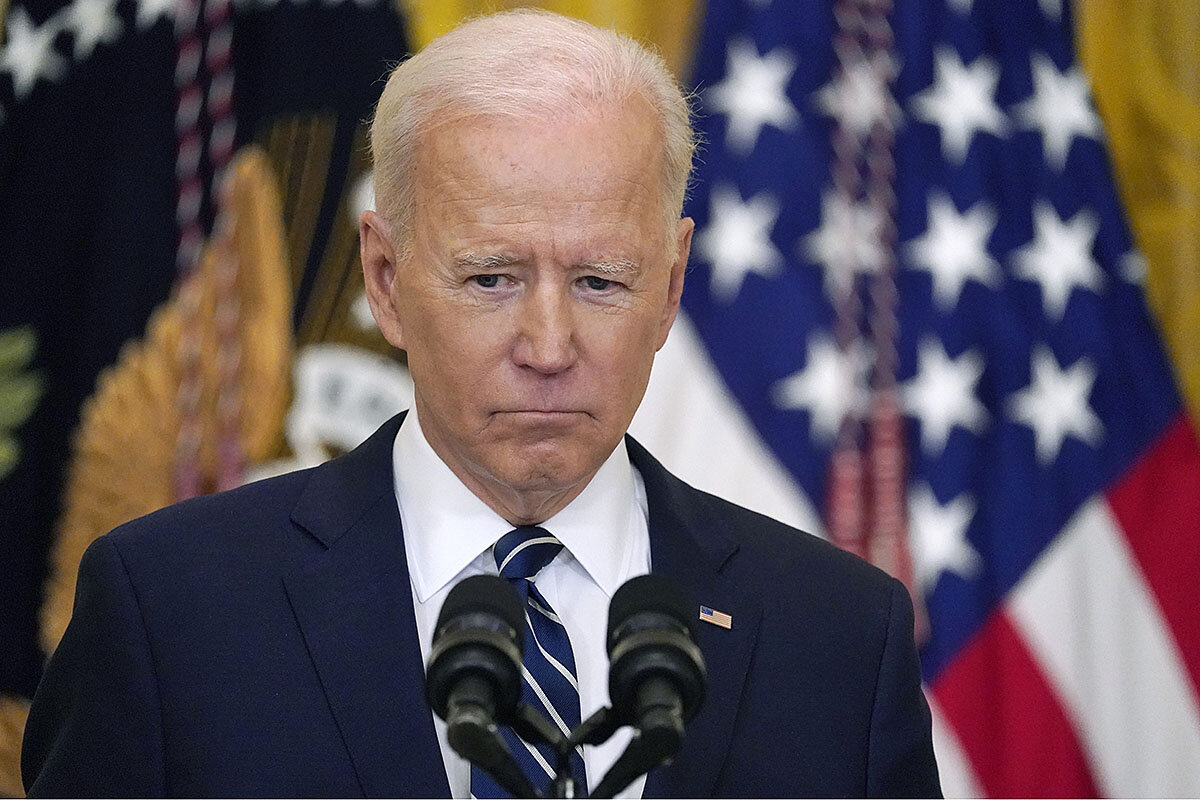

Takeaways from Biden’s first press conference

President Joe Biden made plenty of news at his first press conference since taking office. He said he expects to run for reelection in 2024. He made clear that his next legislative priority is infrastructure. And he offered a blunt assessment of a key global adversary, Chinese leader Xi Jinping: “He doesn’t have a democratic bone in his body ... but he’s a smart, smart guy.”

There were some snarky asides about former President Donald Trump and the GOP. “No idea” if the party will even exist by 2024, President Biden said.

But the focus was on today’s most pressing issues. Mr. Biden set a new goal of 200 million COVID-19 vaccination shots in his first 100 days, up from 100 million, in keeping with a time-honored political strategy: underpromise and overdeliver.

He decried the filibuster, a Senate procedure that effectively requires a 60-vote supermajority on most legislation – and could block much of Mr. Biden’s agenda going forward, as today’s lead article explains. He emoted about the unaccompanied children arriving by the hundreds daily at the U.S.-Mexico border, promising “hope is on the way.”

Why Mr. Biden waited so long to “meet the press” in a formal setting – longer than any new president in a century – is open to conjecture. By delaying, analysts say, he raised the stakes needlessly and opened himself up to questions about transparency.

But chances are, White House reporters care more about this issue than do average Americans, who are busy with work and family.

And now that Mr. Biden’s first press conference is over, about an hour without any gaffes to speak of, perhaps he won’t wait so long for the second.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

US public wants gun laws. A Senate tradition is one big hurdle.

The filibuster effectively requires 60% support to get bills through the Senate. Does that make it an enforcer of broad consensus or an obstacle to basic lawmaking?

Should a Senate procedure not enshrined in the Constitution be allowed to block the will of the majority? That’s the question at the heart of Democrats’ push to end the filibuster, which threatens their sweeping agenda on everything from voting rights to gun safety.

With Vice President Kamala Harris’s tie-breaking vote, Senate Democrats hold a 51-50 majority. But in most cases, they would need at least 10 Republicans’ cooperation to pass legislation, since the filibuster provision allows debate on a bill unless or until 60 senators move to end it.

Democrats, who dismiss the filibuster as a Jim Crow relic, argue that America’s challenges are too urgent to wait for elusive bipartisan consensus. But Republicans argue that ending the long-standing tradition would destroy the Senate’s unique role.

“We urgently need to protect and strengthen, not weaken and destroy, the norms that force us to come together and cooperate,” said GOP Sen. Ben Sasse on the Senate floor March 23, warning against a trend in both parties toward winner-takes-all politics. “The Senate’s job is to enlarge and refine the House’s judgments and to try to build consensus that can last, so that the majority’s will can be advanced while the minority’s rights are also protected.”

US public wants gun laws. A Senate tradition is one big hurdle.

The only thing preventing Democrats from enacting their sweeping agenda on everything from gun safety to voting rights is a long-standing Senate procedure: the filibuster.

Amid a pandemic, crumbling infrastructure, racial injustice, two recent mass shootings, and one of the most contentious presidential elections in modern times, Democrats in Congress argue that America’s challenges are too urgent to wait for the elusive bipartisan consensus needed to overcome a GOP filibuster.

“[Republican Minority Leader] Mitch McConnell cannot have a veto over everything that Congress does. But that’s what the filibuster gives him,” says Sen. Elizabeth Warren, a Massachusetts Democrat. “He exercises that veto to stand in the way of core reforms that our nation needs – protect voting, fight climate change, put basic gun safety regulations in place.”

The Democrat-controlled House of Representatives just passed a pair of gun-safety bills, which have taken on more urgency after gunmen killed 18 people in Atlanta and Boulder, Colorado. It also pushed through two pieces of legislation to provide a path to legal status for unauthorized immigrants, and a sweeping voting rights bill. More legislation is in the works on infrastructure, climate change, and a federal minimum wage hike.

Even on issues like guns – where proposed steps are backed by a strong majority of U.S. voters – these bills have little hope of passage in the evenly divided Senate. Although Vice President Kamala Harris can cast a tie-breaking vote to give Democrats a 51-50 edge, on non-budget legislation they would need at least 10 Republicans’ cooperation, since the filibuster procedure allows debate on a bill unless or until 60 senators move to end it.

Most Democrats say that a Senate procedure not enshrined in the Constitution and used historically to thwart civil rights legislation should no longer be allowed to block the will of the majority, however small that majority may be. Republicans, whose leadership resisted pressure to end the filibuster when they held the majority, argue that scrapping the long-standing provision would destroy a key guardrail in the American republic. The effect would be permanent, they argue, ending the Senate’s unique role as an arena for consensus-building in an increasingly polarized country.

“We already have an institution that is instantly responsive to majorities. ... The House [of Representatives] was designed to reflect the energy of the people,” said GOP Sen. Ben Sasse in a March 23 speech on the Senate floor, warning against a trend in both parties toward winner-takes-all politics that would send the country “pinballing” from one policy agenda to another depending on who was in power. “The Senate’s job is to enlarge and refine the House’s judgments and to try to build consensus that can last, so that the majority’s will can be advanced while the minority’s rights are also protected.”

Debate over principle of minority rights

The filibuster tends to be more of a thorn in the side of Democrats, who favor a more expansive role for government and feel a moral imperative to address national issues through federally funded initiatives. Republicans, by contrast, prefer a more limited role for the federal government and see it as the right and responsibility of states to address challenges within their borders.

The recent shootings in Atlanta and Boulder add urgency to Democrats’ calls to find ways around partisan gridlock, including ending the filibuster or restoring the “talking filibuster” popularized in Hollywood’s “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington,” in which a single senator would hold forth for as long as 24 hours – dissecting bills, reading the Constitution, or even reciting his favorite recipes for fried oysters.

“Two massacres in two weeks, as well as the heightened level of violence throughout our society especially over the last year, demonstrates that we have an undeniable gun violence crisis,” says Georgia Sen. Jon Ossoff, who says he is open to considering rule changes if they open the way for enacting legislation in the public interest. “I came to the Senate to legislate, not to be mired in gridlock.”

But it’s the issue of voting rights that most immediately and directly challenges the principle of the filibuster, since both issues are predicated on a need to protect minority rights.

“It is a contradiction to say that we must protect minority rights in the Senate while refusing to protect them in society,” says Sen. Raphael Warnock, whose win in Georgia’s January runoff election – together with Senator Ossoff’s – gave Democrats control of the Senate.

“Voting rights is not just another issue, alongside other issues. It is foundational.”

A source of gridlock

Last summer, at the funeral of John Lewis, the civil rights icon and longtime congressman, former President Barack Obama called for honoring his memory by passing more robust voting rights legislation – even if it took ending the filibuster, which he dubbed a “Jim Crow relic.”

President Joe Biden, in his first press conference since taking office, said Thursday he agreed with Mr. Obama’s phrase and voiced support for taking steps to “deal with the abuse” of the filibuster.

Although the filibuster debuted long before the Jim Crow era, and has been deployed against a wide variety of issues, it was used repeatedly to block civil rights legislation. In particular, Southern Democrats mounted a two-month filibuster over the 1964 Civil Rights Act, ending with West Virginia Sen. Robert Byrd holding forth for 14 hours and 13 minutes. In the end, some Republicans joined their Democratic colleagues to reach the two-thirds majority needed to invoke cloture, or an end to debate – marking the first time that the Senate had ever successfully done so on a civil rights bill.

Now, Democrats say it’s vital to again strengthen voting rights as GOP legislatures across the country move to enact more stringent voting laws that they say are necessary to protect election integrity in the wake of a massive spike in mail-in voting.

Earlier this month, the House passed the For the People Act, which seeks to expand ballot access with steps like requiring states to allow online voter registration, requiring states to finish purging ineligible voters from their lists at least six months before an election, and prohibiting states from requiring IDs, notarization, or witness signatures to obtain an absentee ballot. The bill passed 220-210, with no Republican support.

If Democrats scrapped the filibuster to clear the way for its passage, Minority Leader McConnell – invoking Thomas Jefferson’s warning that “innovation should not be forced on slender majorities” – vowed to use a series of other procedural moves to bring the Senate to a grinding halt and prevent Democrats from disregarding the will of tens of millions of voters.

“This chaos would not open up an express lane for liberal change,” he said in a March 16 speech. “The Senate would be more like a 100-car pileup. Nothing moving.”

“What you sow, you reap”

Since the 1964 filibuster of the Civil Rights Act, the threshold for invoking cloture has been lowered to 60 votes. But that’s still an extraordinary hurdle for the Senate’s 50 Democrats in today’s climate of party-line votes. Hence, the pressure on Democrats to get rid of the filibuster, which was first made possible in 1806 due to the deletion of a Senate rule. Used sparingly at first but with increasing frequency in the 20th century, it is today the main tool in Republicans’ pocket to block President Biden’s agenda.

Two Senate Democrats, Arizona’s Kyrsten Sinema and West Virginia’s Joe Manchin, have staunchly vowed to uphold it in at least some form, depriving Democrats of the 51 votes they would need to overturn it. Now filibuster “reform” has become a litmus test in some key 2022 battlegrounds, where Democratic candidates are already vowing to scrap the procedure if they’re elected.

But it’s not so long ago that Democrats themselves used the tool they now deem a Jim Crow relic. Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina, a Black Republican whose police reform bill was blocked by a Democratic filibuster last year after they deemed it “weak tea,” pushes back against the idea that the procedure has racist undertones.

“I think they are using it when they want to in ways that they want to, and it’s inconsistent with anything that has to do with any history of race,” he says.

Even as the momentum grows for scrapping the filibuster, there’s a clear recognition of the danger of it backfiring politically – especially if Republicans retake control in 2022.

“If Democrats make the decision to blow up the Senate, and turn it into a partisan jackhammer, that will be an historic mistake,” GOP Sen. Ted Cruz told reporters, wagering that Democrats would come to regret the decision, just as they have Democratic Majority Leader Harry Reid’s decision to end the filibuster for judicial appointments and executive branch nominations in 2013, which later benefited Republicans.

“What you sow, you reap,” admits Sen. Bernie Sanders, the Vermont independent. “But I think that in this particular moment in American history, given the enormous crises that we face, we’ve got to act for the working families of this country.”

A deeper look

To fight pandemic, people gave up liberties. Will they get them back?

Worldwide, citizens have given up civil liberties in order to fight the pandemic. But is it possible to act collectively and maintain individual rights?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

From Australia to Zimbabwe, almost every nation in the world enacted restrictions during the pandemic. Freedom of movement was hemmed in by various rules for curfews, travel, and public and private assembly. Some countries cracked down on speech and press freedoms. Others bypassed privacy in favor of track-and-trace measures and digital surveillance of those under quarantine.

For many citizens, sacrificing civil liberties was a necessary and worthwhile trade-off in the bid to “flatten the curve.” Now, civil libertarians are assessing the short- and long-term ramifications of often unprecedented steps. At issue is whether governments bolstered a sense of partnership with their citizens or squandered trust. The balance between compulsion and cooperation may shape the response to future public emergencies.

“That tension is long-standing, liberty versus security. Are they complements or substitutes?” says Marcella Alsan, professor of public policy at Harvard Kennedy School. “What’s interesting about the current situation, and particularly prior to the development of the vaccines ... was basically, How willing were people to go along with these restrictions? What were they willing to sacrifice and what were they not willing to sacrifice?”

To fight pandemic, people gave up liberties. Will they get them back?

Zoe Buhler was scheduled for an ultrasound appointment on the September morning when Australian police entered her home. The pregnant mother, still in her pajamas, was handcuffed in front of her partner and two children. Her 4-year-old scurried to hide under a bed. Ms. Buhler’s offense? She’d posted a message on Facebook detailing an upcoming peaceful protest in Melbourne against stringent pandemic lockdowns.

“All social distancing measures are to be followed,” said her post, adding, “Please wear a mask.”

She and her partner immediately offered to take the post down. Police seized the computers and cellphones in her home. Authorities in the state of Victoria charged Ms. Buhler with “incitement” because, they say, protests are unsafe and undermine public health measures. In a court appearance tomorrow, Ms. Buhler faces a maximum penalty of 15 years in prison if found guilty.

“During the time of the pandemic, obviously the state can take certain measures to restrict civil liberties, but it’s very important that those measures are necessary, lawful, and proportionate,” says Elaine Pearson, the Australia director at Human Rights Watch, based in Sydney. “It was neither necessary nor proportionate to arrest her in that fashion.”

From Australia to Zimbabwe, almost every nation in the world enacted restrictions during the pandemic. The wide spectrum of measures varied from country to country – and often within different jurisdictions within nations. Freedom of movement was hemmed in by various rules for curfews, travel, and public and private assembly. Some countries cracked down on speech and press freedoms. Others bypassed privacy in favor of track-and-trace measures and digital surveillance of those under quarantine.

For many citizens, sacrificing civil liberties was a necessary and worthwhile trade-off in the bid to “flatten the curve.” Now, civil libertarians are assessing the short-term and long-term ramifications of often unprecedented steps. At issue is whether governments bolstered a sense of partnership with their citizens or squandered trust. The balance between compulsion and cooperation may shape the response to future public emergencies.

“That tension is long-standing, liberty versus security. Are they complements or substitutes?” says Marcella Alsan, professor of public policy at Harvard Kennedy School, who studies public health and infectious diseases. “What’s interesting about the current situation, and particularly prior to the development of the vaccines – when all countries basically have the very same rudimentary toolkit of these NPIs, these nonpharmaceutical interventions – was basically, How willing were people to go along with these restrictions? What were they willing to sacrifice and what were they not willing to sacrifice?”

Ms. Alsan co-authored a November study that surveyed over 400,000 people across 15 nations about their attitudes toward civil liberties during the pandemic. More than 80% were agreeable to giving up some freedoms during a crisis. A closer look at the results, however, reveals gradations between citizens of different nations. Those surveyed in the United States and Japan were far less willing to relax privacy protections, sacrifice the freedom of press, and endure economic losses than those in China. Citizens in European countries occupied a middle ground between those two poles. Respondents in India, Singapore, and South Korea were more willing to suspend democratic procedures for the sake of public health.

According to Human Rights Watch, 83 governments restricted free speech and free assembly in the name of pandemic protections. Enforcement of those measures could be harsh. Youths in the Philippines were locked in dog cages following curfew violations, says Ms. Pearson. In India, police physically assaulted 10 journalists who reported that a COVID-19 roadblock in the southeast was preventing villagers from reuniting with their families. South Africa enforced a ban on cigarettes and alcohol by setting up roadblocks to search cars for contraband.

“Freedom House has been tracking a decline in [global] democracy for the past 15 consecutive years, and what we found is that COVID-19 has really exacerbated that decline,” says Amy Slipowitz, research manager for Freedom House, a U.S.-based nonprofit that tracks civil liberties worldwide.

However, some countries, including Sweden and South Korea, placed a high value on maintaining a fairly open society. Taiwan did so by forging a state-society collaboration. Prior to becoming one of the world’s freest democracies, the small island nation had been subject to martial law and single-party rule from 1947 until the late 1980s. That relatively recent experience colored the Taiwanese response to the pandemic. Taiwan’s Centers for Disease Control had legal authority to implement stringent measures, but it didn’t declare a state of emergency. Schools and stores remained open. In those instances when Taiwan did curtail liberties – including a track-and-trace program that included strict border controls – it employed a humane touch. Individuals placed under mandatory 14-day home quarantine received meal deliveries and trash disposal services. A hotline was set up for their mental health. And in response to concerns that those penned inside a digital fence could be watched by Big Brother long after the pandemic, the state promised to erase that cellphone data.

“The government recognized that, because the people’s freedom of movement is temporarily suspended, it is the responsibility of the government to take care of those individuals who had to be isolated for the sake of the public,” says Tsung-Ling Lee, an assistant professor of law at Taipei Medical University. “The government is seeking broad-based social support in that a lot of our measures that have to be implemented in the epidemic are relational.”

Taiwan’s government also favored persuasion over coercion. Case in point: its handling of one of the world’s three largest religious ceremonies, the Dajia Mazu Pilgrimage. Every April, tens of thousands join in a nine-day parade that originates at the Zhenlan temple and proceeds through a large swath of the island. Taiwan’s Centers for Disease Control has broad legal leeway to institute emergency measures such as prohibiting large public gatherings. Instead, the minister of health and welfare approached the temple’s chairman, a former opposition party member of the country’s legislature. The minister persuaded the temple to change its plans and delay the parade by several months. The temple went even further – it donated its parade budget to the Central Epidemic Command Center. In turn, the minister later appeared at a temple ceremony as a gesture of grateful appreciation to the worshippers.

“It’s better to foster a bottom-up approach toward where the boundaries should be versus having a top-down authoritarian approach of where the boundary should be,” says Ming-Cheng Lo, a professor of sociology and East Asian studies at the University of California, Davis, in a phone call from Taiwan.

Yet Ms. Lo observes that many Western publications – including The Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic, and National Review – have mused that China’s onerous clampdown on its citizenry might be the most effective response to COVID-19. Professor Neil Ferguson, a controversial former adviser to 10 Downing St. in its response to the pandemic, told the British newspaper The Times that he initially didn’t think it would be possible to follow the Chinese model of a stringent lockdown: “It’s a communist one-party state, we said. We couldn’t get away with it in Europe, we thought. ... And then Italy did it. And we realized we could.”

Britain stands out in West

Britain has overseen one of the strictest lockdowns of any Western democracy. On Thursday, Parliament voted to extend the Coronavirus Act for another six months. A new restriction would fine English travelers £5,000 ($6,850) for nonessential travel. More contentious still is the government’s pandemic ban on outdoor gatherings of two or more people. Earlier this month, a nurse in Manchester was fined £10,000 for organizing a 40-person protest over pay for health care workers.

Now, a newly proposed bill would give police leeway to ban any protest if it creates a vaguely specified noise disruption. The British government has already set new precedents over the past year. Until now, the British police have traditionally had independent discretion over how to enforce “soft laws,” or government guidance. Yet during the pandemic the secretary of state for the Home Department breached that wall by briefing police on such matters. The new bill would give the home secretary power to define prosecutable behaviors.

“The historic policing norm in the U.K. has been what we call policing by consent,” explains David Mead, a professor of U.K. human rights law at the University of East Anglia. “Police are drawn from us. They are not agents of the government. They are just citizens in uniform with very few extra powers. ... We have arm’s-length police control from governments so the home secretary can’t direct the police, even a junior officer, how to enforce the law.”

Mr. Mead is concerned that the proposed measures will lead to a real crisis in some state institutions, particularly the relationship between the police and the people.

In the state of Victoria in Australia, stringent enforcement of lockdown rules by police was one of the reasons for anti-lockdown protests such as the one that Ms. Buhler was arrested for promoting. Protesters were galvanized by scenes such as police surrounding a public housing building in Melbourne last July to enforce lockdown of its 3,000 low-income residents.

“The police in Victoria, had a very, very high degree of esteem and trust from the public prior to the coronavirus,” says Gideon Rozner, director of policy at the Institute of Public Affairs, a free-market think tank in Melbourne. “Of course police get up every day and put their lives on the line and serve the community. But I think that they were very let down by the government, who had them enforcing such absurdly punitive laws. ... That’s very, very sad because we don’t want to have a situation in which there is mistrust of the police force. It’s not healthy for an orderly, civilized society.”

As is the case in so many countries – as well as states within the U.S. – Victoria has been sharply divided between those who feel that the government overreached and others who have favored strict measures. Mr. Rozner says some Australians believe that Ms. Buhler’s prosecution is justified for the greater good of maintaining public health. It’s a fraught issue for those on both sides.

Taiwan’s example

Years from now, with the benefit of hindsight and some emotional distance, many countries may take account of their responses to the pandemic. After all, they’ll need to prepare for future public emergencies. Taiwan has already been through a similar process. The nation’s experience with the SARS outbreak in 2003 was characterized by infighting inside the government, political polarization, and cynicism among citizens that led to selfish actions such as keeping infected patients out of their communities.

For the most part, Taiwan hasn’t witnessed a replay of that behavior this time around. A Taiwanese society riven between those seeking reunification with China and those favoring continued independence found harmonious common cause. The two main rival newspapers emphasized the importance of societal collaboration and compassion. Ms. Lo, the Taiwanese sociologist, says that shared desire never to repeat that “traumatic” experience of the SARS outbreak ultimately led to the healing of civil society. It encouraged the Taiwanese to fundamentally reassess the boundaries between personal choice and civic duty during this emergency.

“To have that consensus, then eliminates the need, or at least minimized the need, of having to send police to patrol the streets to see if people who are under quarantine are actually breaking the rules,” says Ms. Lo. “Citizens deliberated among themselves and said, ‘This is a sacrifice that we should all make in order to protect the greater good of all of us.’”

Correction: This article has been updated to the correct the following quote by Prof. Marcella Alsan: “That tension is long-standing, liberty versus security. Are they complements or substitutes?”

‘The status quo is not working’: Mountain town reckons with homelessness

Changing attitudes is critical to solving complex problems, like homelessness. As hard as that can be, Alamosa, Colorado, is seeing some progress – among officials, at least.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Grant Stringer Correspondent

Following a national surge in homelessness during the pandemic, towns in the Rocky Mountain region can no longer ignore the issue. In Alamosa, Colorado, county officials and social service providers are starting to work together, with a focus on overcoming residents’ resentments about unsheltered people.

Last May, the city set up a sanctioned site far away from neighborhoods where homeless people could pitch their tents. Chris Sandoval and Eileen Sandoval, the only ones still at the site, give the place mixed reviews. It’s a long walk to the Safeway where they panhandle. And arguments there were common, as were fires. Three tents went up in flames, although no one was burned.

There is talk of improvements to the campsite, including a full-time social worker living there and some “tiny homes” designed by a local artist. But that would be costly.

Meanwhile, homelessness persists in Alamosa, and Heather Brooks, the city manager, doubts that community attitudes have changed much.

Chris would agree. Three men beat him up recently while he was panhandling.

Since then, he has started work at a local Taco Bell and is eager to save money for a place for himself and Eileen. They plan to stay in Alamosa. They see their future there.

‘The status quo is not working’: Mountain town reckons with homelessness

Last winter, Ricky Plunkett and Christi Buchanan woke up to find their tent completely frozen inside.

The couple, who are homeless, were camping near the Rio Grande on the outskirts of Alamosa. The temperature had plunged to -26 F, and they could hear the fabric of their shelter crackle as it froze.

“We woke up, and on the inside of the tent, it looked like someone just sprayed glass,” Mr. Plunkett says.

They’re from Texas – a warmer climate. But the duo takes pride in weathering sub-zero winters on the floor of North America’s largest high-altitude desert, the San Luis Valley, high in the Rocky Mountains. Alamosa is the biggest community in the vast, remote valley, with about 10,000 residents.

Despite the brutal cold, the couple trekked to Alamosa two years ago to live in a temporary homeless shelter. They’ve since settled into a life spent mostly in a secluded spot near the Rio Grande that’s popular with other homeless campers. Both say they’re stuck in bureaucratic red tape trying to get IDs required for public housing.

Mr. Plunkett and Ms. Buchanan are a chipper couple who mostly want to be left alone. But this month, they found themselves at the center of Alamosa’s reckoning with homelessness.

Amid a national surge in homelessness during the pandemic, many towns in the Rocky Mountain region have faced their own crunch: Shelters have had to limit capacity at the same time as more people have become homeless. The result has been a spread of street encampments, stirring unease and anger among some residents.

“COVID has really opened people’s eyes that the status quo is not working,” says Kathleen Van Voorhis, director of housing justice at the Interfaith Alliance of Colorado.

An important shift

On a recent Friday, more than two dozen local officials picked their way through the cottonwoods around the area where Mr. Plunkett, Ms. Buchanan, and others have been living. Alamosa County Sheriff Robert Jackson, county commissioners, the county public health director, and the local chief of police wanted to see the camps for themselves – and see how they’ll move the campers off the land, which is owned by ConocoPhillips and other companies.

County officials weren’t the only outsiders present. Staff from the local homeless services organization, La Puente (“The Bridge” in Spanish), sat with the couple to calm them during the unnerving experience.

Opinions ranged widely. County Administrator Gigi Dennis said the camps and surrounding refuse were “pretty shameful and disgusting.” Shanae Diaz, La Puente’s street outreach director and volunteer coordinator, wondered where the people would go if the county pushed them out.

Despite the differing perspectives, the scene reflected the start of an important shift in Alamosa’s approach to its housing and homelessness crises. After years of historically thorny relations – or outright silence – between county officials and social service providers, they’re starting to work together.

So far, much of the energy has focused on overcoming long-simmering resentments about unsheltered people and the network that serves them.

Residents say they’ve long noticed more homeless people like Mr. Plunkett and Ms. Buchanan arriving in town. They search for sustenance or a bed at La Puente’s transitional shelter and occasionally cause trouble. Some residents themselves fall into homelessness because of the town’s slim housing stock or due to mental health struggles, addiction, poverty, and more.

It’s a small enough community that locals quickly notice outsiders and assume they’re from somewhere else. Heather Brooks, the city manager, even hears people complain that La Puente buses impoverished people to town.

But Ms. Brooks is quick to note that 85% of La Puente’s clients come from within the San Luis Valley, which is about the size of Connecticut. She’s trying to push that message out to property owners who are hostile to La Puente and the people they serve.

Kent Ruark summed up the feeling on his daily walk with his dog Rodney. He has sympathy for local homeless people, although many other Alamosans think the average La Puente client is “a thief” or just worthless, he says.

“But you’re just a human who’s down on their luck,” Mr. Ruark believes.

Complaints swell during pandemic

La Puente typically accepts between 600 and 800 people into its transitional shelter each year. Suddenly last spring, with COVID-19 capacity restrictions, only 30 people could stay in the shelter at one time.

Homeless people quickly erected more illegal encampments than ever in the residential neighborhoods around town. By May, some property owners were furious.

Driven by a more ambitious perspective at City Hall, Ms. Brooks and the City Council proposed a plan: a “sanctioned” campsite for homeless residents with some amenities, including port-a-potties, Wi-Fi, and a water spigot. It’s a popular option in communities from Las Cruces, New Mexico, to Portland, Oregon.

When the City Council allowed the public to comment on the plan, dozens of residents phoned into a virtual meeting in early May.

“I feel like this homeless population is taking over our city,” Alamosa resident Karrie Kooiman said. One caller, Roberta Taylor-Hill, said “murderers” and “rapists” might be among the people living in the sanctioned camp.

After the meeting, the city established the encampment on a brush-filled parcel far away from any residences – and from La Puente’s popular grab-and-go meals.

Winter returned to the valley, and most homeless people fled the frigid weather. But not Chris Sandoval and Eileen Sandoval.

Earlier in the year, when the pandemic hit, the couple had been homeless in Colorado Springs, the state’s second-largest city. They trekked to Alamosa, where Chris was born, after a homeless shelter required that they live separately because they’re not legally married yet.

Ten months after the sanctioned camp opened, they’re the last of its residents, their campsite tucked into the deepest corner of the dusty site. They give the place mixed reviews. It’s a long walk across town to the Safeway where they panhandle. And arguments there were common, as were fires.

Ms. Diaz, La Puente’s street outreach chief, has built deep rapport with many chronically homeless Alamosans. She said one man detested a bully in the camp and torched his tent before leaving town. Eileen said she heard screaming in the night this winter and then the woosh of two other tents bursting into flames, although no one was burned.

The couple says they’ve been unable to get into the shelter at La Puente, which, a year after COVID-19 appeared, is still at its capacity under the virus restrictions. Although those may ease during the vaccine rollout, Alamosa usually sees an uptick in homeless residents during the spring and summer, so it’s likely that shelter beds will soon be in even higher demand.

And as the weather warms, La Puente staff expect more homeless people to return to illegal camps like the one where Mr. Plunkett and Ms. Buchanan live. It’s unclear whether county officials will move to break up these informal sites. If so, that could create another crisis, Ms. Diaz says.

Friends, family, and a future

City officials and La Puente staff are in talks about investing in the sanctioned campsite to make it more attractive. On the table: a full-time social worker living at the site to help with grievances and perhaps some permanent “tiny homes” designed by a local artist.

But that would be costly, and in Alamosa scarce resources guide every plan.

“When you have high poverty … [it] begets hunger, homelessness, and other crises that destabilize families. And then that same poverty strangles you from the resources that would naturally be available to fight that,” says Lance Cheslock, La Puente’s executive director.

Not only are homelessness and hunger far from resolved in Alamosa and other communities in the region, but it’s unclear whether the more humane perspective now championed by some local officials has spread among regular Alamosans. Ms. Brooks, the city manager, says community attitudes probably haven’t changed that much.

Chris would agree. He was panhandling at the Safeway about a month ago when three men jumped out of a car and beat him up, he says. Ms. Diaz says he was beaten so badly that he couldn’t walk.

He has since started work at a local Taco Bell, eager to save money for a place for himself and Eileen. The couple has no plans to leave Alamosa.

Both are from the San Luis Valley. It’s where they have friends and family and a future together.

Patterns

Millennials bore COVID’s economic brunt. Will boomers help them out?

Older adults have suffered most from the physical effects of COVID-19; young people have borne the economic brunt. Will boomers help them rebuild their futures?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Left or right, rich or poor, East or West. Maybe none of these dividing lines will shape the post-pandemic world as much as old or young.

The generation gap is not new. But the pandemic has widened the gulf between millennials and Generation Z on the one hand, and baby boomers on the other. COVID-19 has affected them in dramatically different ways.

Older people have been more vulnerable to the physical effects of the virus. Young people have borne the brunt of its economic fallout.

Hundreds of millions of young people have lost their jobs as a result of pandemic shutdowns. Many of those jobs may never come back. Tens of millions more have seen their education interrupted.

The challenge facing governments worldwide is to help young people rekindle their aspirations and recover their opportunities. They must ensure that young people learn the skills they will need in the post-pandemic economy, and that the jobs are there for them when they have learned.

Massive pandemic recovery packages mean that for once the money is there to fund such efforts. Now it’s about governments’ priorities, about how much these things matter to them.

Millennials bore COVID’s economic brunt. Will boomers help them out?

What if the defining fissure in our post-pandemic world doesn’t prove to be between America and China, left and right, or rich and poor? What if it’s an older, deeper, and broader rift – the generation gap?

It’s looking ever more likely that the 2020s will be shaped by that familiar dividing line, now inescapably magnified by the pandemic. On one side are the so-called millennials and Generation Z, born since the 1980s. On the other, the post-World War II baby boomers who hold the lion’s share of economic and political power.

To borrow the jokey barb that’s gone viral among young leaders and activists, we may be entering the “OK, boomer” decade, when the postwar establishment will increasingly have to reckon with the influence, needs, and policy preferences of their children and grandchildren.

The change had been stirring before the pandemic. Young peoples’ life prospects were disproportionately set back by the 2008 world financial crash, and new generations of activists have taken the lead on a range of issues affecting their future. Exhibit A: the seismic effect of a Swedish teenager, Greta Thunberg, in driving climate change up the policy agenda.

But the pandemic has moved those generational issues to center stage, intensifying the pressure on governments to be more innovative as they navigate the road to economic recovery.

Reports from around the globe have drawn a clear picture of the dramatically different ways younger and older people have been affected by the pandemic. Older people have been more vulnerable to the physical effects of the virus. Young people have borne the brunt of its economic fallout.

Hundreds of millions of them worldwide, in both wealthy and developing countries, have lost their jobs. Especially if they worked in the informal or gig economies, or in service industries like travel or restaurants, they cannot know when such jobs will be available again. Some may not return at all.

Millions of other young people about to take their first step onto the employment ladder have seen their high school or college education disrupted, or even halted altogether.

The specifics differ from country to country, but the overall picture doesn’t.

In Britain, people under 25 have accounted for two-thirds of jobs lost during the pandemic. In the European Union, youth unemployment had just fallen to its pre-2008 level before the pandemic in most member states. Now it is rising again.

A survey of college-educated millennials late last year in India found nearly 1 in 5 had lost their jobs during the pandemic. In Saudi Arabia, unemployment has risen to an unprecedented 15%, and about two-thirds of the jobless are young people.

Over half of Nigerians between the ages of 15 and 24 are jobless, a far higher rate than among older workers. In Latin America, the latest survey from the International Labor Organization found nearly 1 in 4 young people out of work at the end of last year.

In the United States, unemployment now stands at about 6%. But for 20-to-24-year-olds, it’s nearly 10%; for teenagers leaving high school, nearly 15%. And the pandemic has upended many young lives in other ways. Over half of American 18-to-29-year-olds are now living in their parents’ homes, the highest level recorded, outstripping the Great Depression of nearly a century ago.

The looming challenge is how to respond: how to help young people recover, and rekindle their aspirations and opportunities. How to avoid what some experts are calling the prospect of a “lost generation” in which millions continue to be underemployed, unemployed, or not motivated to seek work at all – severely straining countries’ economic, social, and political fabric.

Youth advocates, economists, and other policy experts broadly agree on the overall imperative: post-pandemic programs specifically targeted at young people.

A range of specific ideas has been proposed. Some address urgent needs, like support for young people to stay in school, or to tide them over as they look for work once pandemic-hit economies get back on track. A senior fellow at the Brookings Institution think tank wants the government to subsidize companies to stage a “national hiring blitz” for young people.

Other proposals focus on a longer-term response: a joined-up assault on the obstacles to youth employment ensuring that young people learn the skills needed for the post-pandemic economy and that the jobs are there once they do so.

How policymakers choose to move forward seems sure to test relations across the generations as no other issue in recent years.

That’s partly because so many of the governments making the decisions remain in the hands of baby boomers – in some cases, leaders born even before the end of the last world war.

But there is another reason there will be such close policy scrutiny.

The economic upheaval caused by the pandemic has set the stage for historically large government finance and investment packages to put national economies back on their feet. For once, it’s not a question of finding the money to fund better schooling, more job creation, and broader social opportunities for young people.

This time, it’s about priorities; about how much these things matter.

Beyond the Underground Railroad: Reckoning with Canada’s slavery history

If you ask most Canadians about their history with slavery, they cite the Underground Railroad. A new institute hopes to bring to light Canadian slavery that existed before the British Empire abolished it.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Most of what Canadians know of slavery is about tropical plantations, through movies like “Django Unchained,” “12 Years a Slave,” or “Lincoln,” says Charmaine Nelson, Canada Research Chair in transatlantic Black diasporic art and community engagement at NSCAD University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. There is no film on Canadian slavery.

She says Canada has essentially erased the 200 years of slavery that came before 1833, when the British Empire abolished slavery across its territories. That’s the driving force behind the university’s new Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery, where she is founding director.

Dr. Nelson hopes that through the new institute's work, the world will begin to understand slavery of temperate climates – how enslaved people adorned themselves or how they lived, for example. That's why the institute is working out of an arts university, she says: so that the work they produce – both academic and artistic – might reach a bigger audience.

“We dichotomize ourselves with the U.S.,” she says. “We blame all colonial baggage of North America on Americans, or say, ‘Don’t import the racism of America.’ No, no, no, this is homegrown racism.”

Beyond the Underground Railroad: Reckoning with Canada’s slavery history

With charges of racism raining down on the British monarchy after Oprah Winfrey’s interview with Prince Harry and Meghan, the Duchess of Sussex, Canada’s relationship to the crown – and its own legacy of racism – swiftly came under the microscope, too.

In one Canadian television news segment wrestling with the implications for a Commonwealth country, a panelist fell back on one of the more common refrains when it comes to Canada’s history with slavery: its role as the destination of the Underground Railroad for enslaved people in the United States.

But that only tells the nice part of the story, says Charmaine Nelson, Canada Research Chair in transatlantic Black diasporic art and community engagement at NSCAD University in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

She says Canada has essentially erased the 200 years of slavery that came before 1834, when the British Empire abolished slavery across its territories. That’s the driving force behind the university’s new Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery, where she is founding director.

“We constantly teach the part of slavery that makes us look and feel good, that positions us as benevolent abolitionists,” says Dr. Nelson. But that deficit of knowledge has implications for the way race relations are understood, policy is penned, and justice protests are perceived. “It fits with this false narrative that we’re multicultural, we’re race-blind, we’re colorblind, we have no racism.”

It’s not that the history of slavery here is hidden; it just hasn’t been robustly told. Protests against streets or institutions bearing slave owners’ names have grown over the years, and after a long push by advocates, the House of Commons voted unanimously Wednesday to recognize Emancipation Day on Aug. 1.

“Canadian folklore”

But Erica Ifill, a columnist for Ottawa newspaper The Hill Times and podcaster in Canada, says mainstream society has preferred to reduce the topic to the 30-some years that Canada was a safe haven from the southern U.S. The inequities the pandemic has exposed between races, however, and the Black Lives Matter protests that a locked-down world watched last summer, have placed a limit on the tolerance for this kind of “Canadian folklore,” as she calls it.

Ms. Ifill was one of the guests on the CTV “Power Play” show addressing the revelations shared by Harry and Meghan that someone within the monarchy questioned how dark their yet-to-be-born son’s skin tone would be.

She was joined by David Onley, the former lieutenant governor of Ontario, who turned the discussion toward the “rich history” of Ontario, formerly Upper Canada, when it came to taking the first legislative steps to free enslaved individuals. “That’s why the people from the southern United States with the Underground Railroad, that’s why they moved to the north.”

Ms. Ifill called him out for “cherry picking” history, at a time when colonial powers were stealing land from Indigenous people and life was hardly easy for those of African descent here.

“You can’t pick and choose which parts you like,” she says.

Most of what Canadians – and the world – know of transatlantic slavery is about tropical plantations, through movies like “Django Unchained,” “12 Years a Slave,” or “Lincoln,” says Dr. Nelson. There is no film on Canadian slavery. Academics don’t even have an estimate of the size of the enslaved population brought to the French and English colonies that spanned from what is now Ontario to the eastern coast.

Dr. Nelson hopes that through the new institute’s work, the world will begin to understand slavery of temperate climates – how enslaved people adorned themselves or how they lived, for example. That’s why the institute is working out of NSCAD University (formerly Nova Scotia College of Art and Design), she says: so that the work they produce – academic research, and arts and popular visual culture – might reach a bigger audience.

The institute, whose construction has been delayed because of the pandemic, will include space for visiting scholars, a screening room where films will be discussed and conferences held, and a reference library. They hope to invite their first visiting fellows for the upcoming academic year, including two graduate students and two artists-in-residence. It’s touted as the first of its kind.

A more urban slavery

The site of Nova Scotia is key to understanding northern slavery, says Yvonne Brown, who works at Saint Mary’s University in the department of social justice and community studies. Maritime Canada was central to trading slave-produced commodities such as sugar, molasses, and rum in exchange for salted and canned fish, and lumber from the area enabled the shipbuilding and lumbering industry that facilitated enormous imperial international trade, she says.

In Canada, the number of enslaved people would have been much smaller because agriculture is not year-round. But that means they would have lived inside slave-owner homes, instead of distinct slave quarters, leading to less autonomy and more surveillance. Slavery here was more urban, and enslaved people stood out more. That slave numbers were smaller has fed into notions that slavery was gentler than in the U.S., Dr. Nelson says, a current that runs through U.S.-Canadian comparative history.

She says in nearly two decades teaching the visual culture of slavery, only one student of hers raised a hand when asked whether they knew that there was slavery in Canada. Plenty of them, however, are aware of America’s history of slavery and how that affects race relations in the U.S. through the present.

“We dichotomize ourselves with the U.S.; we blame all colonial baggage of North America on Americans, or say, ‘Don’t import the racism of America.’ No, no, no, this is homegrown racism,” she says. “For me, the reason this institute is so important is there’s almost no racial injustice that happens today that you can’t draw a line straight back to slavery.”

She connects the hyper-surveillance of enslaved people in Canadian households more than 200 years ago to the hyper-surveillance of Black Canadians by the police, to name one example.

And she says it’s time that more Canadians start making those same connections.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A nod for a different African future

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In 2014, five countries in Africa’s Sahel region joined in a military compact with France to counter Islamist militant groups with force. But instead of halting the threat, the military strategy has compounded the misery. Troops sent in to protect villages have themselves been accused of atrocities. Millions have been displaced and thousands killed.

Seven years later, the advance of extremism in parts of Africa has prompted a rethink of the military approach. There is a growing consensus, according to the U.S. Institute of Peace, that “militarized counterterrorism responses that have dominated in the post 9-11 era are failing, particularly in Africa.”

One of France’s Sahel partners, Niger, indicated March 22 what a shift in strategy might involve. Reeling from two deadly attacks by suspected jihadis in recent days, the government called for three days of national mourning and announced an investigation “to find the perpetrators of these cowardly and criminal acts and bring them before the courts.”

In Niger, the balance of guns and butter is getting a second look. A society is bound together far more by force of its ideals than by the force of arms.

A nod for a different African future

In 2014, five countries in Africa’s Sahel region joined in a military compact with France to counter Islamist militant groups with force. The local bands had become affiliated with Al Qaeda. Communities were repeatedly attacked; their children kidnapped to become wives or soldiers. But instead of halting the threat, the military strategy has compounded the misery. Troops sent in to protect villages have themselves been accused of atrocities against civilians. Millions have been displaced and tens of thousands killed.

Seven years later the advance of extremism in parts of Africa – from the Sahel to Somalia to Mozambique – has prompted a rethink of the military approach. There is a growing consensus, according to a recent paper by the U.S. Institute of Peace, that “militarized counterterrorism responses that have dominated in the post 9-11 era are failing, particularly in Africa.” French President Emmanuel Macron recently conceded that point. In January he signaled his intention to withdraw the 5,000 French troops in the Sahel. A month later he ruled out such a departure.

One of France’s Sahel partners, Niger, indicated March 22 what a shift in strategy might involve. Reeling from two deadly attacks by suspected jihadis in recent days, the government called for three days of national mourning and announced an investigation “to find the perpetrators of these cowardly and criminal acts and bring them before the courts.” Those two actions point to what has been missing: an approach to security that extends the reach and influence of national governments as much through strong legal and social measures as through military force.

More often than not local communities have borne the burden of caring for victims of attacks and people fleeing violence, not governments. In Mozambique, for example, where more than 570 horrific attacks last year alone left nearly a million people facing severe hunger, residents in surrounding unaffected areas have “shown incredible solidarity and generosity with displaced persons,” states the United Nations.

Prioritizing military responses to extremism is understandable. Urgency lies with protecting civilians. But the real solutions involve building trust in local and national government. The 2014 Sahel compact itself includes a framework for balancing defense with improving daily life, such as education, health care, and access to safe drinking water. The United States and France had hoped that training African special forces to contain the threat of terrorism would create a space for governments to begin meeting those needs. That has not happened. Islamist militants are thriving in predominantly Muslim areas that are impoverished and remote.

Niger’s desire to use its justice system to hold militants accountable is acknowledgment that the slower work of improving standards of living and strengthening the rule of law is just as urgent as protecting lives. That requires redirecting some of the hundreds of millions of dollars already committed by Western and Gulf countries for security in the Sahel to things like power grids and classrooms.

It may also require drawing on Africa’s unique approach to justice. Nigeria has already shown that trying extremists in courts is not enough. The volume of accused individuals has overwhelmed its formal legal system and compromised fair standards of trial. That threatens the rule of law more than strengthening it. Traditional forms of restorative justice, such as those that helped Sierra Leone and Rwanda overcome mass hate and trauma, could help ease that burden and salve wounded communities.

The crisis of Islamist violence in Africa points to its solution. As the International Crisis Group stated last month, “The governance crisis that lies at the root of the Sahel’s problems is prompting growing hostility towards governments, whether expressed in rural insurgency or urban protest.” In Niger, the balance of guns and butter is getting a second look. A society is bound together far more by force of its ideals than by the force of arms.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Silencing ‘locker room talk’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Thomas Mitchinson

As God’s children, each of us is inherently capable of knowing what is right and acting accordingly, with compassion, dignity, and grace.

Silencing ‘locker room talk’

Years ago, I swam every day early in the morning. The gym was always very busy. One day, while getting dressed after my swim, I heard another man talking about women with degrading and obscene sexual language.

At that moment, one of his friends came over to me, introduced himself, and asked what I did for a living. I replied, “I am a Christian Science practitioner and devote my life to helping others through prayer.” He mentioned that his grandmother had been a Christian Scientist, adding that he had respect for what I did. At that point, the whole locker room became quiet. And as I was getting ready to leave, the first man came over to me, apologized for what he had said about women, and told me he wouldn’t speak that way again.

Something about my stand for Christianity and prayer must have touched him. I saw him in the locker room many times after that, and I never heard him use profane or derogatory language again. This has meant more to me in recent years, as the use of “locker room talk” – sexually based jokes and stories that often degrade women – has come under increased scrutiny. It is no longer tolerated as just a typical part of men’s conversations.

Contrast that with another experience, also years ago, that I have never forgotten. My wife and I were at a Chicago Bible Society dinner. One of the honorees was a prominent elected official. Upon receiving his award, he stood on the platform, and the first words he uttered were, “Let the words of my mouth, and the meditation of my heart, be acceptable in thy sight, O Lord, my strength, and my redeemer” (Psalms 19:14). It was a humble declaration by an extremely accomplished man, giving the reason why his advocating for freedom and dignity for all people was so effective.

Those words from Psalms are a great guide to live by, and our doing so can also make a difference for others, as the life of Christ Jesus showed. No one has ever lived those words better than he did, and his whole life brought healing and resolution to all sorts of situations.

Jesus also had potent words about watching our language. In answer to an accusation that his disciples were not observing the religious law of the time, he replied: “Not that which goeth into the mouth defileth a man; but that which cometh out of the mouth, this defileth a man” (Matthew 15:11). To defile means to spoil something – to pollute it.

Jesus always knew what to say to quiet his questioners, to tone down the rhetoric, and to bring morality and decency to the melodrama of the day. When confronted by a group determined to bring him into a discussion about whether or not to kill an adulterous woman, he simply said, “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her.” With those words, the woman’s accusers dispersed. He turned to the accused and said, “Neither do I condemn thee: go, and sin no more” (John 8:7, 11).

What is it that can silence a man in a locker room, give a politician the courage and integrity to base his life on pleasing God, and allow Jesus to bring healing to an ugly situation? It is the Christ – the healing activity of God, Truth, speaking to humanity. Jesus may no longer be present in human form, but the Christ he embodied speaks to the conscience of everyone, clearing away the pollution of obscenity, pornographic images, prejudice, racism, and all forms of hatred.

Christ does this by revealing that our true selfhood is spiritual, created by divine Love, Spirit, God. Our identity is composed of an infinite array of spiritual qualities, including goodness, purity, intelligence, strength, and love. The ability to know what is right and to act with compassion, dignity, and grace is inherent in all of us as children of God.

That was what Jesus ultimately saw in his encounter with the woman and her accusers. He understood so clearly that her true identity was spiritual and pure that it shamed and silenced her accusers and provided her the opportunity to have a radically different life.

We are not mortal, “testosteroned” or “estrogened” blobs of protoplasm that revel in decadence and conflict. We are the spiritual reflection of God, with a divine inheritance and makeup. That which contradicts our true selfhood – the speech or activity that would degrade or victimize – is cleaned out by the understanding of this God-created, God-ordained, and God-maintained true identity of each of us. It is this understanding, lived and demonstrated, that brings respect, opportunity, peace, purpose, and joy into our lives.

Adapted from an article published in the March 16, 2020, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Some more great ideas! To read or listen to an article on how God’s loving protection establishes safety and morality, please click through to a recent article on www.JSH-Online.com titled “‘Lo, I am with you alway.’” There is no paywall for this content.

A message of love

In a tight spot

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow, when staff writer Ann Scott Tyson explores Myanmar’s deeply religious society, and its role in challenging the nation’s military rulers.