- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How US-Russian citizens’ diplomacy caught fire

Anticipation is high – and expectations low – ahead of next Wednesday’s summit between Presidents Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin. Such mixed emotions also marked this week’s convening of the Dartmouth Conference, now in its seventh decade as the longest-running citizens’ dialogue between prominent Americans and Russians.

There was joy over the recent extension of New START, the last remaining U.S.-Russian arms control agreement. And delegates mourned the COVID-19-related passing of the beloved Orthodox priest in the Russian delegation, Metropolitan Feofan of Kazan. The pandemic also forced this week’s dialogue onto Zoom.

“This was a unique undertaking,” said Matthew Rojansky, director of the Kennan Institute and a conference organizer, in an email. “To come together and speak frankly and productively to one another, despite the long-distance virtual format and despite the acute tensions in the relationship today, was very powerful.”

The suite of crises in U.S.-Russian ties – from Ukraine and Belarus to cyberattacks and election interference – has only grown since this reporter joined the Dartmouth dialogues in 2015. Thankfully our discussions, led by veterans of diplomacy, avoided going down polemical rabbit holes.

Instead, the more fruitful areas of engagement remain in civil society, among librarians, physicians, religious leaders – and now a new working group, firefighters.

One can imagine common ground on the issue of wildfires, faced increasingly by both countries amid climate change. But J.P. Natkin, a battalion chief in New York’s Westchester County and leader of the U.S. Dartmouth “fire and emergency services” team, tells me the focus is much broader: to share ideas on training and techniques, and to build ongoing relationships.

“The fire service is like a giant, global fraternity and sorority,” Mr. Natkin says. “Whenever I travel, I always go to the firehouse. You go in, you have coffee, you talk. They are my brothers and sisters.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

How Iran’s crisis of confidence makes it less democratic

Iran’s conservative power brokers, fearing they could not win a fair election, are tipping the scales like never before, upsetting the balance between “Islamic” and “Republic” aspects of the regime.

Iran’s looming presidential election comes at a challenging time for the Islamic Republic. Economic hardship has prompted lethal protests; hopelessness about the future is pervasive, and apathy widespread; campaigns to boycott the election have taken root.

With the regime’s popular legitimacy appearing in the balance, the result has been a crisis of confidence among conservative power brokers and an unprecedented lurch away from democratic practices.

The first sign that this election would be like no other came when the powerful Guardian Council announced a shortlist of vetted candidates, rejecting well-known centrists, reformists, and most other conservatives, and ensuring that the hard-line judiciary chief who lost the last election will be virtually uncontested.

The second sign has been officialdom’s relative indifference to voter turnout – a metric portrayed in every election since the 1979 Islamic Revolution as proof of legitimacy. Little is being done to combat the boycott campaigns, as if that vote of confidence were no longer achievable.

Trending on Twitter is the hashtag in Persian: #NoWayIVote.

“The rational thing to do when things go wrong is try to open up, to get more public support,” says Ervand Abrahamian, a historian of modern Iran. “But if you narrow yourself down, it’s just alienating more people.”

How Iran’s crisis of confidence makes it less democratic

Iran’s presidential election next week comes at an especially challenging time for the Islamic Republic. Economic hardship has prompted lethal street protests; hopelessness about the future is pervasive, and voter apathy widespread; and campaigns to boycott the election have taken root.

Trending on Twitter is the hashtag in Persian: #NoWayIVote.

With the regime’s popular legitimacy appearing in the balance, the result has been a crisis of confidence among conservative power brokers and an unprecedented lurch away from democratic practices toward more autocratic methods.

Analysts warn these measures are likely only to further alienate voters across Iran’s political spectrum on election day, June 18.

The first sign that this election would be like no other came when the powerful Guardian Council announced the shortlist of vetted candidates.

Ensuring that the candidacy of hard-line judiciary chief Ebrahim Raisi – a midranking and uncharismatic cleric who lost the last election – will be virtually uncontested, the council rejected well-known centrists, reformists, and most other conservatives.

Even some hard-liners were shocked by this brazen attempt to engineer the result, which appeared to upend the tense balance that has prevailed for decades between “Islamic” theocratic rule and “Republic” democratic aspects of the state.

The Guardian Council, a 12-member body that oversees elections and can override decisions by parliament, has often been criticized for overzealous vetting, especially of reformist candidates. But this is the first time it has shaped an outcome so clearly.

“I have never found the Council’s decisions to be this unjustifiable,” lamented Sadegh Larijani, a veteran member of the council and former judiciary chief. Alluding to the intelligence arm of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), a key tool of hard-line power, he complained on Twitter of “growing interference by intelligence agencies” and their “intentional manipulation” of the late May decision to anoint Mr. Raisi.

Appalled, he said, “In the midst of these strange times, I seek refuge in God.”

The second extraordinary sign is officialdom’s relative indifference to voter turnout – a metric portrayed in every vote since the 1979 Islamic Revolution as crucial proof of enduring popular support.

Little is being done to combat the apathy and boycott campaigns, as if that public vote of confidence were no longer necessary – or achievable.

“The elections are going to drastically erode the regime’s legitimacy,” says Ervand Abrahamian, a preeminent historian of modern Iran and retired professor at the City University of New York.

“For the last four decades, the main form of legitimacy has been high participation of the people in elections, with sometimes 80% turnout,” says Professor Abrahamian. “Anything lower than 50% has been considered a vote of no confidence.”

Recent polls put likely turnout at less than 40% – possibly less.

Behind the choice of Raisi

Amid a sense of decline and deepening unpopularity, analysts say the choice of Mr. Raisi – and the way in which the Islamic Republic’s so-called deep state has made that choice – speaks volumes about the rising levels of anxiety among Iran’s leaders.

The stakes are especially high today with no clear successor to supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, now 82 years old.

Mr. Raisi may be seen as a trusted pair of hands, and is even tipped by some as a potential next supreme leader, though his religious credentials are weak. Among other senior positions, the current judiciary chief has served as custodian of the Imam Reza shrine apparatus in Mashhad.

Yet Mr. Raisi is bedeviled by his role on a four-man, inquisition-style “death commission” in Tehran that oversaw the execution of thousands of prisoners in 1988 – a “medieval background” that Professor Abrahamian says “would further erode the regime’s legitimacy” were he to be elected president.

Mr. Raisi was handily beaten in 2017 by incumbent President Hassan Rouhani, a centrist whose plans to reach out to the West, improve the economy, and increase social freedoms engendered hope – and a high turnout – in the two elections he won.

Iranians’ hopes surged with the 2015 landmark nuclear deal with world powers, but collapsed in 2018 when the United States withdrew from the deal and imposed “maximum pressure” sanctions.

Narrowing the choice to Mr. Raisi “is so self-destructive,” says Professor Abrahamian. “If you can no longer give someone like Rouhani to run against the conservatives, then who’s going to really vote, except for the true believers in Raisi?”

Redefining democracy?

The shift toward a noncompetitive race heralds an effort by some hard-liners to redefine “democracy” in Iran, since multiple victories for reformists, starting with the 1997 election of Mohammad Khatami, clearly show their popularity.

“We have a problem that began with the Khatami presidency,” the archconservative strategist Hassan Abbasi told Iranian media. “We embraced the Western democratic model for the election process. ... That was a mistake.

“The United Arab Emirates does not hold any election; aren’t the people living with less headaches?” he said of that Persian Gulf monarchy. “There is no election in Oman. ... None in Turkmenistan. ... All those people are living with less headaches, aren’t they?”

That argument has been taking hold among pro-regime elements fearful that they will lose power for good if a non-hardliner wins again, says a well-connected Iranian analyst who travels often to Iran and requested anonymity.

“I would use the headline that, ‘This is the deep state’s attempt to take over,’” says the analyst, who defines the deep state as including certain figures in the supreme leader’s office, key hard-line clerics and lawmakers, parts of the judiciary and state media, and IRGC intelligence.

The lesson of 2017

The turning point for them was the 2017 election, when hard-line and moderate conservative forces – and all their media – backed Mr. Raisi, yet he still lost by 8 million votes.

The loss “was the ultimate lesson that ... they won’t win in a truly competitive election,” says the analyst. “So if they want to turn things in their favor, they will have to tighten the political space up to a degree that brings their own guy out of the ballot box.”

“For them, Syria-type elections, Russia-type elections, they like that,” says the analyst. “They still really think, ‘We need some sort of popular backing,’ but to them it’s enough if there is a clear result in the end,” such as 70% for Mr. Raisi – even if that 70% is just 11 million votes, out of 59 million eligible voters.

Indeed, a low turnout would indicate a desire to “punish the Islamic Republic,” Iranian journalist Fereshteh Sadeghi in Tehran told a Johns Hopkins University webinar Tuesday. “It doesn’t necessarily mean that we want to topple you. ... We just want to say, ‘OK, you don’t care about us; we don’t care about you.’”

The attempt to shrink the democratic space has also prompted debate among conservative factions weaned on the dual Islamic and Republic aspects introduced by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who stressed that people “are the lords of the ruling elite.”

Many hard-line camps “were really angry and have continued to be angry at this restricted choice because ... they do believe in the republican nature of the system and that requires votes and elections,” says Narges Bajoghli, an expert at Johns Hopkins University who closely follows conservative discourse in Iran.

“They are trying their hardest to keep the reformists from coming to power, but they don’t want to do that through the process that’s been coming about these past few weeks, because that takes away all claims of legitimacy,” says Ms. Bajoghli, author of "Iran Reframed: Anxieties of Power in the Islamic Republic."

Internal versus external

She notes the irony that Iran’s external strategies are succeeding in countering American and Israeli influence, through an Iran-led “axis of resistance” from Gaza and Syria to Iraq and Yemen. Yet at home the forces that orchestrate and support those “victories” struggle to win a free election.

“Regionally they are very strong. Internally, they’re very unpopular across much of the population,” says Ms. Bajoghli.

That has prompted a potentially dangerous miscalculation, says Professor Abrahamian.

“The rational thing to do when things go wrong is try to open up, to get more public support. But if you narrow yourself down, it’s just alienating more people,” he says.

“I think the most important thing is the question of legitimacy, and if they don’t have that legitimacy, all they are going to have is a raw power of terror [that] puts the balance of power much more in the hands of the Revolutionary Guard,” he adds.

And in that push away from democratic mechanisms, Iran has many examples.

“We’ve seen, not just across the region, but across the globe, states are willing to completely militarize the streets in an attempt to silence or at least push back protest movements, and Iran is part of that trend,” says Ms. Bajoghli. “I think their calculation is, ‘It’s worked in all these places. It’ll work for us.’”

Reporter’s notebook: How Biden’s 5 predecessors fared on NATO stage

The performances of the last five presidents at NATO summits have molded and influenced how Europe views the alliance’s leader – and the United States. Our reporter witnessed them all.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In 1989, after a meeting of NATO heads of state, when British reporters asked the NATO staffer at President George H.W. Bush’s press conference if there would be “a translation for Bush speak,” it was indeed amusing.

But for me, covering my first meeting of NATO leaders, the snickering also risked obscuring the really big accomplishment Mr. Bush sensed was in reach: a peaceful end to the Cold War and a reunited Germany.

Now, 30-plus years and a long line of summits later, I’m back in Brussels for the debut of President Joe Biden. And that has had me thinking back over the NATO meetings I attended featuring Mr. Biden’s five predecessors: the first Bush, then Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump.

Every event has been an opportunity to witness how each president was playing in Europe – and moreover to gauge their impact on European public opinion’s assessment of the United States.

If a new Pew Research Center poll released this week is any indication, Mr. Biden is already off to a good start. Still, he might follow in the footsteps of some past presidents and do something to keep the good vibes going.

Reporter’s notebook: How Biden’s 5 predecessors fared on NATO stage

The group of British journalists having a little fun at the expense of the American president – George H.W. Bush – had a point.

The year was 1989, and the world was fast becoming aware of what Americans already knew: Mr. Bush didn’t always have a smooth way with words.

So, after a meeting of NATO heads of state, when the Brits asked the NATO staffer handing out headsets for translations of the American president’s press conference if there would be “a translation for Bush speak,” it was indeed amusing.

But for me, an American journalist attending my first meeting of NATO leaders, the snickering over a maladroit president also risked obscuring the really big accomplishment Mr. Bush and his foreign policy team sensed was in reach: a peaceful end to the Cold War and a reunited Germany.

Now, 30-plus years and a long line of summits and other gatherings later, I find myself back in Brussels for another NATO summit – this time the debut of President Joe Biden. And being here in the city of the North Atlantic Alliance’s headquarters has had me thinking back over the NATO meetings I attended featuring the five presidents preceding Mr. Biden: the first Bush, then Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Donald Trump.

Three decades and five presidents that spanned the crumbling of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War (NATO’s original raison d’etre), the 9/11 attacks and NATO partners’ solidarity with the United States – and on to a world where Europe increasingly plays second fiddle to Asia in America’s National Strategic Orchestra.

Every event has been an opportunity to witness how each president was playing in Europe – and moreover to gauge their impact on European public opinion’s assessment of the U.S.

Viewed from that perspective, what stands out? A young, smooth-talking Bill Clinton with a saxophone; a George W. Bush charm offensive that fell flat; an aloof Barack Obama ensconced behind the tinted bullet-proof windows of his “Beast” limousine; and a NATO-disdaining Donald Trump declaring himself “a very stable genius” at the 2018 summit’s press conference.

Europeans were grateful to the first President Bush, garbled speech and all. But they were smitten by a young Bill Clinton, who came across as charming, smart, seductive, and a little bold – qualities that reinforced Old Continent notions of what America should be.

Belgium was charmed when Mr. Clinton accepted a specially engraved saxophone from the mayor of Dinant, the city where the American president’s favorite musical instrument was born. But Brussels fairly swooned when a waving Bill strolled across the city’s famed Grand-Place, and later dropped in unannounced at the Au Vieux Saint Martin restaurant, spending about a half-hour chatting up stunned diners.

Mr. Clinton “wanted to know the reaction of us Bruxellois to Americans; he wanted to see if we were still friends,” the Saint Martin’s owner later recalled.

And the answer was, they were. Of course there was some disappointment when Bill neglected to play his new saxophone for the people who presented it to him. That would only happen later in the trip, when Mr. Clinton gobsmacked a Prague pub with a rendition of “My Funny Valentine.”

A decade later, the second President Bush would make a NATO summit one port of call of what the White House dubbed a “conversation with Europe” tour – in the wake of an Iraq War that among Europeans was deeply unpopular.

In Brussels, Mr. Bush captured the front page of newspapers by stopping in to make a purchase at a famed chocolate shop. The newspaper photos showed the shop’s employees smiling broadly as the American president made his selections.

But when I stopped by the shop days later, the smiles were gone. It was nice that Mr. Bush stopped in, one shop attendant told me, but it hadn’t changed her view of him. “Personally, I’m against wars, especially unnecessary ones,” she said.

The response was only tepid when the president, from the stage of a Brussels concert hall, laid out his vision of transforming the world’s trouble spots by spreading democracy.

And it may have been that kind of cold reception in “Old Europe” that explained why Mr. Bush would choose Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia – part of what the president’s defense secretary, Don Rumsfeld, famously called “New Europe” – to deliver an open-air speech to a more receptive public.

A half-decade later, Europe would once again find itself enthralled with an American president – at least initially. Barack Obama took Europe by storm, filling Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate early on and even winning a Nobel Peace Prize before completing his first year in office.

But by the time Mr. Obama attended the 2010 NATO summit in Lisbon, Portugal (not all NATO summits are at headquarters in Brussels), Europeans were starting to understand why the American president was also known as “cool Obama.”

Mr. Obama’s aloofness and mild disregard for European leaders he privately dubbed “freeloaders” for not paying more of Europe’s defense bill seemed to be on full display in the contrasting modes of transportation that NATO’s leaders used at the summit.

European leaders held a press conference to highlight the cute, zero-emissions electric vehicles they’d be tootling around in between summit events. But it was Mr. Obama who captured the front pages of Lisbon’s and other European newspapers with detailed descriptions of “the Beast,” the president’s hulking, bomb-shelteresque – and gas-guzzling – limousine.

Yet whatever disappointment Europeans experienced with Mr. Obama, nothing prepared them for the shock of Donald Trump.

Who was this American president who called Brussels a “hellhole” and who was captured at the 2017 NATO summit’s traditional “family photo” pushing his way through shorter and thinner leaders to plant himself at the front of the class?

Then came Mr. Trump’s “very stable genius” self-evaluation at his 2018 post-summit press conference. After the event, a group of Afghan journalist friends came running up to my press center station, desperation in their eyes.

“Our editors want to know why President Trump calls himself ‘stable genius,’ and we don’t know what to say,” one said. “Can you explain?”

I recall responding that I could only make a guess, that some people in the U.S. questioned his mental stability. “But also, remember that Trump was a television personality before becoming president,” I said. “He likes the idea of putting on a show.”

Now Brussels prepares to welcome Joe Biden – a much more traditional president, nothing like the showman Trump – who will be here Monday and Tuesday for NATO and European Union summits.

And if a new Pew Research Center poll released this week is any indication, Mr. Biden is already off to a good start in boosting world opinion of the United States.

This year’s Pew poll gauging America’s global image in 16 countries found a whopping 75% favorability rating for Mr. Biden – compared with the 17% rating Mr. Trump achieved last year.

Overall, U.S. favorability rose from 34% in 2020 to 62% this year, Pew reported.

Still, Mr. Biden might follow in the footsteps of some past presidents and do something to keep the good vibes going.

So here are a couple of suggestions from a longtime observer of presidents at NATO: As an avid biker, Mr. Biden could don his helmet and join the parade on any one of Brussels’ many bike paths.

Or what about fries with mayonnaise? The president would surely win a city’s heart by stopping in most anywhere and ordering (being careful not to call them “French” fries) a combo that is a national favorite.

Vaccine passports: Why Europe loves them and the US loathes them

Coronavirus passes could become the new normal in Europe, even as the U.S. balks at the idea. The difference comes down to circumstances and values – and will shape post-pandemic global mobility.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Sara Miller Llana Staff writer

-

Lenora Chu Special correspondent

-

Yannis-Orestis Papadimitriou Correspondent

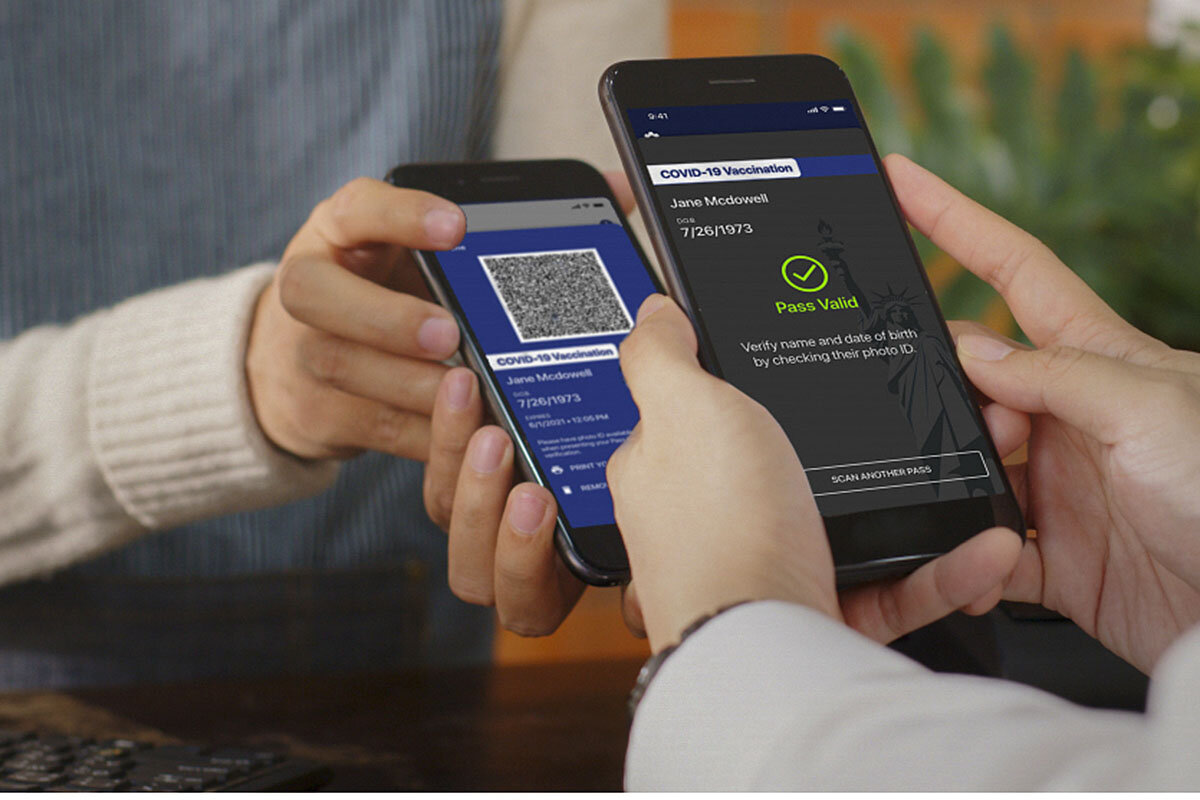

Starting July 1, all European Union member states will accept the EU Digital COVID Certificate, also known as the “green passport,” as proof of vaccination against COVID-19, of a recent negative test, or of recovery from the disease. The plan got a resounding yes at the European Parliament on June 9.

But across the Atlantic, the idea faces strong head winds, whether for travel or domestic use. The Biden administration has ruled out introducing vaccination passports, and some states even ban them.

Prioritizing freedom and fears of government overreach underpin the rejection of vaccine certificates in the U.S., while European societies have grappled more with issues of privacy and fairness. And so as Western countries savor a return to the old, this phase of post-pandemic mobility is being shaped by cultural attitudes and the initial responses to the pandemic.

“Alabama never closed the border to Mississippi in the way Finland closed the border to Sweden,” points out Anders Herlitz, a researcher at Sweden’s Institute for Futures Studies. “Here in the EU, the vaccine passports are seen as a necessary evil to get rid of other, much more extensive, limitations to people’s freedom, whereas in the U.S., they would not help getting rid of other limitations, but only cause new limitations.”

Vaccine passports: Why Europe loves them and the US loathes them

Back in 1992, Yiannis Klouvas converted an old cinema into the Blue Lagoon restaurant, which garnered a strong reputation for live music. There is no music now. The business, like so many others on the Greek island of Rhodes, is struggling due to the pandemic’s restrictions on travel.

“If we see a tourist on the street these days,” he says, “we take a photo to remember them.”

Mr. Klouvas is now banking on the EU Digital COVID Certificate, also known as the “green passport,” to save the summer. Starting July 1, all EU member states will accept the certificates as proof of COVID-19 vaccination, a recent negative test, or recovery from the disease. The plan got a resounding yes at the European Parliament on June 9. All EU member states, Liechtenstein, and Norway will implement the passport.

But across the Atlantic, the idea faces strong head winds, whether for travel or domestic use. The Biden administration has ruled out introducing vaccination passports, and some states even ban them. Fox News talk show host Tucker Carlson likened the use of them to segregation. “Medical Jim Crow has come to America,” he said.

Prioritizing freedom and fears of government overreach underpin the rejection of vaccine certificates in the U.S., while European societies have grappled more with issues of privacy and fairness. And so as Western countries savor a return to the old, this phase of post-pandemic mobility is being shaped by cultural attitudes – like Europeans’ tendency to make the most of having entirely different cultures within a few hours’ drive – and the initial responses to the pandemic.

“Alabama never closed the border to Mississippi in the way Finland closed the border to Sweden,” points out Anders Herlitz, a researcher at Sweden’s Institute for Futures Studies. “Here in the EU, the vaccine passports are seen as a necessary evil to get rid of other, much more extensive, limitations to people’s freedom, whereas in the U.S., they would not help getting rid of other limitations, but only cause new limitations.”

Jen Kates, director of global health and HIV policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation in Washington, says previous pandemic plans didn’t account for cultural variations and responses.

“One thing we know from how COVID has played out globally is that culture matters,” she says. “Politics, culture, all the differences that we know that structure people’s lives have to be taken into account, both for getting back to normal and for preparing for the next pandemic.”

Europe’s green passport

Nine European countries, including Greece and Germany, are already using the EU COVID-19 passport. When the Greek government unveiled the passport, Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis trumpeted the opening of a “fast lane” to facilitate travel. Everyone realizes two years without tourists would be an economic disaster for the Mediterranean nation.

“Greece is very strongly pro-vaccine passport, especially as far as foreigners are concerned,” says Paris Kyriacopolous, chairman of Motodynamics and Lion Rental, which operates Sixt Rent a Car in Greece.

Ipsos polling data suggests the dominant attitude toward COVID-19 vaccine passports across Europe is equally positive. When it comes to using them domestically, citizens are more concerned by questions of fairness than by privacy issues, and pockets of society are ambivalent about or opposed to vaccines. But when it comes to travel, the view is clearly pro.

Even Germany, which had more rigorous ethical debates on the issues and boasts stringent data privacy laws, got behind the idea of digital health certificates. More than 60% of Germans now support implementing them, according to a recent YouGov poll, even though less than half the population has had a first jab.

Malcolm Jorgensen, an academic who is providing administrative assistance at one of Berlin’s six vaccination centers, is fully vaccinated as of this week. His vaccination card has allowed him to shop at markets and visit the gym without flashing a coronavirus test result. He says the move from a paper card to a digital passport isn’t much of a leap.

“There’s already informal digitization,” says Dr. Jorgensen. “At the gym I can just show a photograph of my vaccination booklet, rather than the booklet itself. Digitization is inevitable.”

In Germany, debates over the passports have had less to do with privacy concerns than with equity of access for people who choose not to or cannot be vaccinated. Analysts note that medical insurance companies already have individuals’ health details.

“It’s an ethical question,” says Olga Stepanova, a data protection attorney with WINHELLER Law. “Each government needs to decide what kinds of access limitations may be imposed to protect others, while not limiting freedoms of non-vaccinated people in an inappropriate way.”

Concern about privacy

The freedom debate has been particularly fierce in the U.S. Much like other issues throughout the pandemic, the vaccine certificate has become deeply polarizing.

The divisions fall along partisan lines – just as they did with stay-at-home orders and mask mandates – and so different states have moved toward normalcy in distinct ways. New York was the first to introduce its Excelsior Pass, which allows residents to prove their vaccination status to gain access to certain social venues. But several states, including Florida and Texas, ban such passes outright.

The state of Michigan has been one of the most closely watched during the last year, ever since former President Donald Trump notoriously tweeted “Liberate Michigan” last spring in regard to tough anti-lockdown measures implemented by Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer. This spring, as the state coped with one of the worst spikes of COVID-19, a bitter debate over vaccine passports broke out.

This month the Michigan House approved legislation to ban so-called vaccine passports in the state – even though the governor has repeatedly said she has no intention of introducing them. “The threat of government controlling one’s daily life through identification of whether one is immunized or not is frightening,” said Rep. Sue Allor, who proposed the bill.

Like the rest of the country, the state is divided. The University of Michigan has mandated that students living in dormitories must prove vaccination. Since Michigan is a border state, some Democrats have pushed for passes as a way to travel more easily to Canada and avoid quarantines.

Dave Boucher, a government and politics reporter with the Detroit Free Press, says opposition centers around freedom of choice. It’s about “the government ‘telling me what I can and can’t do,’” he says. “And there’s always the slippery slope argument where if the government is endorsing vaccine passports now, then they’re going to get vital information about you and track that information and use it in unknown, nefarious ways.”

Rich Studley, president and CEO of the Michigan Chamber of Commerce, says the vast majority of his members are committed to a safe reopening and return to normal, but don’t see passports as a way to do it.

“There is no groundswell of support that would be in favor of mandatory vaccines and vaccine passports,” he says. “If there is one thing businesses have learned over the past year in Michigan, other than how to survive, it is how to operate their business safely to protect employees and customers.”

In general, Americans – much like Europeans – are more accepting of passports to travel than they are for domestic use, according to polls. Some analysts believe they are an inevitable part of post-pandemic mobility.

“Digital health certificates are already available in the EU, and my guess is that they will be widely used, even without being adopted by the U.S.,” says Chris Dye, a professor of epidemiology at Oxford University in Britain.

As other parts of the world move forward with passes, the U.S. might find itself playing catch-up. “It’ll be really interesting to look ahead three to six months and see as other parts of the world are going forward and using these kinds of mechanisms, if there will be a change,” says Dr. Kates.

Dominique Soguel reported from Basel, Switzerland.

Inheritance, fairness, and the billionaire class

Asking the rich to pay more in taxes has long been broadly popular in the U.S., in the name of fairness. President Biden and a bombshell IRS leak kindle new debate over how to do it.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Sympathy for small-business owners often goes hand in hand with distrust of government and the taxation that pays for it. But polling shows that while Americans celebrate wealth creation, they believe the rich pay too little in taxes.

President Joe Biden has proposed a boost in the capital gains tax on investments, coupled with removing a special tax break on inheritance for the wealthy. Currently, when someone sells an inherited asset, the original value is “stepped up” to the date of inheritance, not its original cost. The Biden plan eliminates the step up.

ProPublica reported Tuesday that the richest 25 Americans paid little or no income tax from 2014 to 2018, thanks to a tax code that rewards capital income, according to leaked IRS data.

The vast majority of Americans would be unaffected by Mr. Biden’s proposed changes, since they inherit too little wealth to be taxed.

“People like the idea that someday all this will be yours,” says Ray Madoff, a law professor at Boston College who studies estate planning and tax policy. But the big tax debate “is about the super-wealthy of America who are subject today to minimal tax liability.”

Inheritance, fairness, and the billionaire class

Morris Pearl isn’t a billionaire. But by the time he retired in his mid-50s in 2014 as managing director of Blackrock Inc., the world’s biggest asset management firm, he was a rich man.

“I’ve been fortunate. I have enough income from my investments so I don’t need to work anymore,” he says.

What’s more, under long-standing American tax law taxpayers like Mr. Pearl have long enjoyed advantages when it comes to passing wealth from one generation to the next.

Often, America’s relatively low taxes on wealth are justified as an incentive for job creation by capitalist investors. But a recent tax reform proposal by President Joe Biden is putting the spotlight on an often overlooked facet of the tax code: Wealth is taxed more lightly when it's inherited, which creates a disincentive for the wealthy to sell assets and reinvest their capital during their lifetimes.

President Biden’s proposal to tax inherited wealth more aggressively sits at the intersection of populism and practicality. Forcing the rich to pay more in taxes has long been broadly popular, including among Republicans whose elected representatives tend to push in the opposite direction. Frustration over rising wealth inequality has taken center stage in the politics of the United States and other rich democracies.

ProPublica reported Tuesday that the richest 25 Americans paid little or no income tax from 2014 to 2018, thanks to a tax code that rewards capital and penalizes labor income, according to leaked Internal Revenue Service data. The revelation of the paltry tax liabilities of billionaires like Elon Musk and Michael Bloomberg could draw further attention to Mr. Biden’s reform proposals. His administration said it was investigating the leak of confidential tax records.

But while ending tax breaks for millionaires is popular, it can be tricky to craft tax policy that hits the intended targets. For Mr. Biden and Democrats, it could also be politically risky to incur a backlash over higher levels of taxation that fall on small-business owners.

“The challenge is to be sure that the tax consequences for continuing businesses and being able to provide for these businesses to grow [are] thought through carefully. That’s where our primary concern is,” says Pete Sepp, president of the National Taxpayers Union, a lobbying group on fiscal policy.

The tax break that Mr. Biden wants to eliminate – and lobbyists like Mr. Sepp are defending – is the “step-up in basis” rule, which allows heirs to avoid taxation for capital gains on the past appreciation of assets like real estate and stocks. If and when they do sell, the original value is stepped up to the date of inheritance. Consider Amazon founder Jeff Bezos. His heirs would inherit his Amazon stock valued at its market close, not its value when he was building the company.

Instead, the Biden administration proposes to realize and tax inherited assets at death, while also raising the top rate of capital gains taxes for high earners from 23.8% to 43.4%. Taken together, these changes could potentially net as much as $400 billion over 10 years. (By comparison, raising the top bracket of income tax from 37% to 39.6%, as Mr. Biden has proposed, could be worth $100 billion over the same period.)

The proposed change is part of a larger Biden plan to fund his ambitious domestic spending program, while keeping his pledge not to raise taxes on middle-class households.

Even as the proposal rattles tax attorneys and estate planners – and kicks up dust in Congress – not all rich Americans reflexively oppose the idea.

Mr. Pearl, who lives in New York City, chairs the Patriotic Millionaires, a group of wealthy progressives who advocate for higher taxes and a livable minimum wage. He supports Mr. Biden’s proposal to raise capital gains rates and eliminate the step-up for heirs, despite the implications for his two adult sons who stand to inherit his fortune.

“I don’t think there’s any reason why if they inherit my stocks they shouldn’t pay tax on those gains,” he says.

Why this particular loophole is in the tax code is no mystery, he adds. “The rules were written for the convenience of rich people, and rich people prefer not paying taxes.”

Billionaires versus family farms

The vast majority of Americans would be unaffected by the changes, since they inherit too little wealth to tax. The Biden plan includes a $1 million per-person exemption for capital gains on inherited assets; principal residences are already excluded up to $250,000 per person. So the burden would fall mostly on upper-income families who own multiple houses and stocks, bonds, and other financial assets.

Since capital is taxed more lightly than income, such families already enjoy tax advantages, even before wealth is transferred between generations, says Ray Madoff, a law professor at Boston College who studies estate planning and tax policy.

“This is about the super-wealthy of America who are subject today to minimal tax liability,” she says.

But forcing the realization of capital gains at death could unsettle family-owned businesses that face a hefty tax bill. This includes rural business owners whose representatives have sounded the alarm over the Biden tax plan: Last month 13 Democratic representatives from rural districts wrote to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi to call for exemptions for family farms.

“Farms, ranches, and some family businesses require strong protections from this tax change to ensure they are not forced to be liquidated or sold off for parts, and that need is even stronger for those farms that have been held for generations,” the members wrote.

The White House has said certain family-owned firms could defer paying capital gains tax to avoid liquidations, provided the business remains in family hands.

Sympathy for small-business owners often goes hand in hand with distrust of government and the taxation that pays for it. This is especially potent when it comes to the estate tax, a separate levy on the total wealth of a person that Republicans branded a “death tax.” Under President Donald Trump, its exemption more than doubled to $11.7 million, meaning even fewer have to pay it.

But polling shows that while Americans celebrate wealth creation, they believe the rich pay too little in taxes. Ordinary taxpayers may also be growing wary of inherited fortunes. In a January poll by Reuters/Ipsos that asked if “the very rich should be allowed to keep the money they have, even if that means increasing inequality,” 54% disagreed.

While the fate of family farms and factories can animate public debate, analysts say they represent only a fraction of the inherited assets that would be taxed under Mr. Biden’s plan.

"People like the idea that someday all this will be yours. That’s one piece. But that looks very different if someone is passing on the family farm or a centibillionaire is passing on his wealth,” says Professor Madoff.

Questions of revenue – and fairness

Still, the White House proposal to raise capital gains taxes for high earners is roundly opposed by Republicans in Congress, who say it will discourage investment and lead to lower productivity and wage growth.

On their own, higher rates on capital gains wouldn’t help President Biden’s agenda. Indeed, the Penn Wharton Budget Model (PWBM) at the University of Pennsylvania projected that the IRS would actually take in less revenue over the next decade because investors would hold assets longer, knowing they could transfer them to their descendants without realizing those gains.

Ending the step-up basis would reverse that trend: Tax receipts would go up, not down, since investors would no longer have discretion to realize gains, says John Ricco, policy director at PWBM. How much? Wharton’s model predicts $113 billion over 10 years, less than other estimates.

Mr. Ricco says these projections matter, but so does President Biden’s promise to tackle economic inequality. It’s “not just about raising revenue. It’s as much an attempt to shape the distribution of income in a way that a lot of Americans would think is more equitable.”

Film

Joy returns to theaters with ‘In the Heights’

Like many Americans, our culture writers have longed to get back into theaters. The new Lin-Manuel Miranda musical, “In the Heights,” offered a chance for two of them to compare notes on what film has to say about this moment. Tyler is a student of theater who’s seen “Hamilton” multiple times; Stephen has never seen it. Spoiler alert: They say the movie, directed by John M. Chu, offers a dazzling reminder of the purpose of art during times of darkness. It manages to be both larger than life and life-affirming.

-

Stephen Humphries Staff writer

Joy returns to theaters with ‘In the Heights’

Despite distanced seats and masked faces, my local theater this week was electrifying.

The latest musical to make the trip over to the big screen is “In the Heights.” The adaptation is the work of Lin-Manuel Miranda, who recruited his “Hamilton” breakout star Anthony Ramos to play a dreamer named Usnavi. While “In the Heights” was released on HBO Max June 10, for many Americans, the musical is a thrilling chance to return to movie theaters.

In the film, Usnavi sets his sights for his homeland, the Dominican Republic, insistent on fixing his late father’s bar, which was destroyed in a hurricane. However, he discovers that his current home still needs support.

Nina Rosario (Leslie Grace) returns home after being racially profiled in her first year at college. She finds her father (Jimmy Smits) struggling to pay her tuition and wrestling with the difficult decision of whether to sell his business as wealthy white business owners begin taking over the neighborhood.

Through vibrant song and dance, the film celebrates the Latin cultures prevalent in New York City’s Washington Heights neighborhood. The movie counts down to a power outage that threatens to exhaust a community already struggling to resist economic and social strains.

Around the film’s halfway point, in the song “Blackout,” Usnavi’s Abuela Claudia (Olga Merediz) belts, “We are powerless, we are powerless” – referring to their lack of electricity, but also, metaphorically, to the fragility of their realities. As the U.S. recovers from the pandemic, one that exposed Hispanic communities to disproportionate unemployment and mortality rates, “In the Heights” sheds more light on challenges facing vulnerable communities.

The film paints a magnificent portrait depicting overlooked realities for American immigrants. While “In the Heights” definitely shows the tragedies that often beset urban communities, it is not, by any means, a tragic tale.

As America slowly reopens art spaces and theaters across the country, “In the Heights” is a dazzling reminder about the purpose of art in times of darkness. During the film’s blackout, while many were scrambling to seek refuge, others used fireworks to light up the sky.

In a subsequent number, flags from the various cultures that embroider Washington Heights proudly decorate the scene as residents sing until their power is restored. In this way, joy becomes our country’s strongest illuminant.

At the end of the film, audience members rose to offer a standing ovation, clapping and cheering as if it really were a live performance. In a country struggling with economic and social blackout, “In the Heights” shines light. (4 out of 5 stars) – Tyler Bey, Staff writer

If you leave home, can you find belonging?

At one point during the musical “In the Heights,” a crowd in a public swimming pool spontaneously breaks into an aquatic song-and-dance number. It’s like the water ballet scene in Busby Berkeley’s “Footlight Parade” but with the scale of an Olympic Games opening ceremony.

The sequence exemplifies how movie musicals are, by nature, larger than life. The marvel of “In the Heights” is that it also feels true to life.

Set in New York City’s gentrifying neighborhood of Washington Heights, it’s a story about defining one’s identity during major life changes. Young bodega owner Usnavi (Anthony Ramos) dreams of returning to the Dominican Republic. His young helper, Sonny (Gregory Diaz IV), has ambitions of going to college, but doing so would risk exposing his status – or lack thereof – as an unauthorized immigrant. That’s weighing on Usnavi’s conscience. The bodega owner also wishes to woo Vanessa (Melissa Barrera), a hair-salon employee who wants to launch a fashion boutique downtown. Meanwhile, the two owners of the salon – the social hub for gossip on the block – have decided to relocate their business to the Bronx. They worry that their regular customers won’t follow them. All the characters in this immigrant community are torn about uprooting their lives so that they, or their loved ones, can branch out. If you leave your home, can you find belonging in the world?

“A dream isn’t some sparkly diamond,” says Usnavi. “There’s no shortcuts. Sometimes it’s rough.”

Much like Spike Lee’s seminal urban drama “Do the Right Thing,” the events take place during a heat wave. It’s sweltering from the get-go. The predominantly Latino denizens hang up laundry, turn fire hydrants into spigots, and pry limpets of chewing gum from the soles of their shoes. Director Jon M. Chu (“Crazy Rich Asians”) uses these naturalistic vignettes as a counterbalance to the choreographed musical sequences. His movie stays grounded even when the characters don’t – in one enchanting scene, a couple defies gravity by dancing on the vertical wall of a building.

“In the Heights” arrives with hyped expectations because its creator is Lin-Manuel Miranda. (Confession: I haven’t seen “Hamilton” because I didn’t want to take out a mortgage for the theater tickets. I’m banking on seeing it when it finally arrives on the high-school drama circuit, so probably sometime around 2041.) Miranda, who has a cameo appearance as a street merchant, showcases his renown for rap-influenced conversational lyrics as a proxy for dialogue. His hummable show tunes draw from everything from bossa nova to calypso music to hip-hop. The rhythms are Latin; the beats come from the heart. Miranda’s character-based story culminates with a twist that illustrates that home isn’t a locale, it’s a state of consciousness.

“In the Heights” is getting a simultaneous release on HBO Max. But I wouldn’t trade the communal experience of seeing this in a theater for convenience of staying at home. After a pandemic in which viewers have become so accustomed to the small screen, Chu’s inventive, energetic, and joyous motion picture is a timely reminder of what “cinematic” truly means.

“In the Heights” is not only larger than life, it’s also life-affirming. (5 out of 5 stars) – Stephen Humphries, Staff writer

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The world’s response to Ethiopian famine

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Seven months after a war broke out in Ethiopia, it remains unclear how many civilians have been killed. Estimates vary wildly. But something is known: Ethiopia’s military and its allies have burned stores of seeds, destroyed farm equipment, and killed oxen and even aid workers trying to deliver food. In other words, they have used starvation as a tool of war. And indeed, on June 10 the United Nations declared a famine exists for an estimated 350,000 people in Tigray.

The tactic of conflict-induced hunger is not new in the history of warfare. What is new for Ethiopia’s famine is that the global community has an additional tool to prevent the weaponization of food. Three years ago, the U.N. Security Council passed a resolution that, for the first time in the council’s history, condemned starvation as a form of warfare and declared it a war crime. More importantly, it empowered the U.N. to impose sanctions on individuals and entities that obstruct aid to hungry civilians in a war zone.

The war in Tigray represents another chance for the world to break the link between war and starvation. The increasing strength of humanitarian law can finally do it.

The world’s response to Ethiopian famine

Seven months after a war broke out in Ethiopia, it remains unclear how many civilians have been killed in Africa’s second most populous nation. Estimates vary wildly. But something is known: Ethiopia’s military and its allies have burned stores of seeds, destroyed farm equipment, and killed oxen and even aid workers trying to deliver food.

In other words, they have used starvation as a tool of war, hoping it will end a rebellion in the northern region of Tigray. And indeed, on June 10 the United Nations declared a famine exists for an estimated 350,000 people in Tigray, the worst war-induced famine in a decade. A further 400,000 people could be in famine conditions by September, perhaps replicating the historic Ethiopian famine of 1983-85.

The tactic of conflict-induced hunger is not new in the history of warfare. Seven decades ago, the United States considered blocking food supplies to Cuba to put pressure on the communist regime. In Yemen, South Sudan, and other current conflicts, fighters often deny access to humanitarian aid. What is new for Ethiopia’s famine is that the global community has an additional tool to prevent the weaponization of food.

Three years ago, the U.N. Security Council passed Resolution 2417, which, for the first time in the council’s history, condemned starvation as a form of warfare and declared it a war crime. More importantly, it empowered the U.N. to impose sanctions on individuals and entities that obstruct humanitarian aid to hungry civilians in a war zone. The measure adds to the rules of the Geneva Conventions that require parties in a conflict not to hinder the ability of individuals to obtain adequate food.

The Security Council has yet to address Ethiopia’s food crisis, a result of Russia and China preventing such action. But on Thursday, the U.S. and European Union held a “high-level roundtable” to draw the world’s attention to the humanitarian emergency in Ethiopia. The U.S. announced an additional $181 million in aid for the war’s victims. And it already has set restrictions on economic and security assistance with Ethiopia over human rights abuses in Tigray.

Sanctions are not the only response to such atrocities. Last year, the Nobel Peace Prize was given to the world’s largest humanitarian organization, the World Food Program, for its work in preventing “the use of hunger as a weapon of war and conflict.” The WFP has learned over the years how to position aid more effectively during a conflict and even prevent conflict by preventing hunger.

The war in Tigray represents another chance for the world to break the link between war and starvation. The increasing strength of international humanitarian law, combined with accountability for those who violate it, can finally do it.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Change of heart

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

Dissatisfaction, uncertainty, and misplaced hopes yield to joy, peace, and progress when we welcome divine Love into our heart, as this poem conveys.

Change of heart

My innermost thoughts

throb with contingent joys,

murky desires, skewed

motives – all out of sync

with the rhythm of Spirit,

God, so it seems.

Spirit, show me Your

rhythm, I pray, as the

“living, palpitating presence

of Christ, Truth”* streams

a message my listening heart

warms to: that divine Love’s

endless pulsating of pure

motive, unselfish desire, and

satisfied joy enlivens and

blesses us now.

Then the lifeless drumbeat

of useless thoughts not written

in the vital score of spiritual

reality recedes, and it dawns

on me: We as the children

of God, Love, walk to the lilt

of Love’s heartbeat.

*Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 351

Looking for more timely inspiration like this? Check out the “Related stories” below; explore other recent content from the Monitor’s daily Christian Science Perspective column; or sign up for the free weekly newsletters for this column or the Christian Science Sentinel, a sister publication of the Monitor.

A message of love

Olympic trials and smiles

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come again Monday, when the Monitor’s diplomatic correspondent, Howard LaFranchi, reports on the future of NATO from the summit in Brussels.