- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Pandemic left many children without parents. Can nations boost support?

- ‘The signs are there.’ Is US democracy on a dangerous trajectory?

- How your cloud data ended up in one Virginia county

- Croatia needs tourists, but are tourists ready to return to Croatia?

- Women on a mission: Life-changing adventures by horse and bicycle

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How one psychologist opens a door for patients’ spiritual concerns

When David Rosmarin was just starting out as a psychologist, a number of patients asked him, “Can I talk to you about God?” His perplexed response? “Well, not really,” he says with a laugh. “I’m here to be a behavior therapist.”

But Dr. Rosmarin started wondering whether spirituality could be incorporated into mental health treatment. Last week, he published an article in Scientific American about a program he pioneered at McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts. The goal is not to guide people’s religious views, but to open the door for patients’ spiritual concerns to be discussed during treatment, if they wish.

“A lot of patients say that it’s a resource,” says Dr. Rosmarin, an Orthodox Jew. “Spirituality helps them feel a sense of solace. They feel a sense of identity, purpose, and meaning in life.”

Since 2017, more than 5,000 patients have enrolled in SPIRIT (Spiritual Psychotherapy for Inpatient, Residential, and Intensive Treatment). Clinical trials found that 90% of patients said the sessions had helped them. At a time when church attendance is falling and many Americans describe themselves as “spiritual but not religious,” SPIRIT caters to patients of all backgrounds. SPIRIT’s resources range from readings from various faiths to handouts about prayer and forgiveness.

For people who have found that religious communities aren't meeting their needs, “it speaks to an innate spiritual need,” says Dr. Rosmarin, who is also an associate professor at Harvard Medical School. “We are working at this point on how to get SPIRIT out to other hospitals and other areas. That’s the next challenge in front of me.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Global report

Pandemic left many children without parents. Can nations boost support?

As a consequence of the pandemic, a large number of children have been orphaned. Will it prompt reforms in children’s welfare that family advocates say are long overdue?

-

Whitney Eulich Special correspondent

-

Sarita Santoshini Correspondent

An estimated 40,000 children in the United States have lost a parent or caregiver to COVID-19, and hundreds of thousands more have around the world. Children’s needs are mounting amid the pandemic – and government support that is hard to access in the best of times barely matches the magnitude.

But children’s rights have come to the fore, too, with the overwhelming need prompting systems to rethink how they deliver care. “Without a doubt, this is a crisis that’s also an opportunity,” says Matilde Luna, director of the Latin America Foster Care Network.

In the U.S., children’s advocates have generated calls for more support. In India and Mexico, meanwhile, the pandemic has forced governments to continue reforming their child welfare systems away from institutionalization, in line with best practices that children’s advocates have been recommending for years.

“The pandemic is speeding up this plan to help kids, to eradicate institutionalization, and have more kids live their right to be with their families,” says Lizzeth Navarro, who until recently was executive director of the Office of the Attorney for the Protection of the Rights of Girls, Boys, and Adolescents in Mexico City.

Pandemic left many children without parents. Can nations boost support?

Charlee Roos loved the “buddyship days” she shared with her father when she was a kid. He would take her out for Mickey Mouse pancakes, attend all her soccer games, and go to her dance recitals, “even though he didn’t really get dance competitions.”

He was her best friend, Ms. Roos says.

Two days before Christmas, Kyle Roos died of COVID-19. In the last days, when he couldn’t speak and asked family to be his voice, she peppered nurses and doctors with terminology most high school sophomores barely grasp – knowledge her father, a well-loved pharmacist in their hometown in Minnesota, imparted to her growing up.

Now, she continues to be his voice – to her little sister, Layla. That means showing up at the hockey rink, where Ms. Roos’ father and sister shared a love of the ice. “I’ve tried to go to every single one of her hockey games and support her that way,” she says.

And she aims to be his steady presence, in all the ways her 10-year-old sister needs.

“My mom and I have really tried to encourage her to talk about my dad. We’ll go through pictures of him and show her pictures when he was younger and tell her stories about him,” she says. “I think she feels a little alone in all of this.”

The girls are among an estimated 40,000 children in the United States who have lost a parent or caregiver to COVID-19, according to modeling published in April in JAMA Pediatrics. In a preliminary study published as a pre-print by The Lancet ahead of peer review, researchers estimate that over 1 million children lost caregivers through December, with the U.S., Mexico, and Brazil among the worst affected.

Globally, children’s needs are mounting – and government support that is hard to access in the best of times barely matches the magnitude of the problem. “Kids have been made invisible in this pandemic,” says Dora Giusti, head of child protection at UNICEF Mexico.

But children’s rights have come to the fore, too, with the overwhelming need prompting systems to rethink how they deliver care. In the U.S., JAMA Pediatrics’ estimate generated calls for more support for children, including benefits they are entitled to but often don’t receive. And in India and Mexico, the pandemic has forced governments to continue reforming their child welfare systems away from institutionalization, in line with best practices that children’s advocates have been recommending for years.

“Without a doubt, this is a crisis that’s also an opportunity,” says Matilde Luna, director of the Latin America Foster Care Network (RELAF).

Coming forward for kids

In the small Indian town of Pilani, in the western state of Rajasthan, Nikhil Bansal’s aunt and uncle died within days of each other in April – leaving his cousins, twin boys aged 16 and a 22-year-old woman, alone. Mr. Bansal’s family (not their real name, to protect their privacy) lives next door, and immediately rallied around the children.

“One of our aunts spends the night at their place. During the day, they come and study alongside me. We try to make sure they aren’t alone,” says Mr. Bansal. Every morning, he hears the oldest sibling replaying videos of her father that he had posted on Facebook.

Since March 2020, more than 3,600 Indian children have been orphaned, and 26,000 have lost one parent, according to government figures. At the height of India’s second wave, social media was flooded with adoption requests, prompting officials to step in to prevent child trafficking and create awareness about the legal process for adoption. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government has offered financial and educational assistance to children who have been orphaned, and some state governments have offered help as well.

Prabhat Kumar, head of child protection at Save the Children India, says subsidies are tied up in red tape and too many children fall through the cracks. (Mr. Bansal’s cousins, for example, don’t qualify for government programs because their mother’s death certificate does not list COVID-19 as the cause of death.) But he’s encouraged by efforts to keep children in their homes and communities, rather than sending them to institutions.

Nearly half of such institutions do not have adequate measures in place to prevent sexual and physical abuse, according to the country’s first-ever national audit last year, and their adoption rates are paltry. “The silver lining is that we are seeing many community members come forward,” Mr. Kumar says.

One of them is Vidhya Kamble, a community health worker in a tiny village in Sangli district in Maharashtra – about 1,000 miles south of Mr. Bansal’s home. She’s been caring for two boys next door, aged 7 and 10, sent to their ancestral village by their overwhelmed father after his wife died of COVID-19. For three weeks the children had lived alone while their father cared for their mother in the hospital.

No stranger to the siblings thanks to their previous visits, Ms. Kamble often video-called the boys – who had both tested positive for COVID-19 – to keep their spirits up. Now that they’re next door, her own children keep them company. But much of the village did not take kindly to the brothers’ presence, fearful of infection. “I kept telling them what the facts were and that there was nothing to worry. Now they understand,” she says.

Speeding up reform

In Mexico, children’s welfare has long been considered a family matter, with even relatives sometimes hesitant to get involved, says Lizzeth Navarro, until recently the executive director of the Office of the Attorney for the Protection of the Rights of Girls, Boys, and Adolescents (DIF) in Mexico City. But when the pandemic forced shelters to reduce their services, the office tapped its network of child care workers to become temporary foster parents – fortifying existing efforts to build a foster system.

“The pandemic is speeding up this plan to help kids, to eradicate institutionalization, and have more kids live their right to be with their families,” she says.

Government goals to shutter homes for children in favor of foster care or keeping children within the nuclear family, where appropriate, hadn’t seen notable progress until the pandemic arrived, says Ms. Luna of RELAF. Since then, a handful of states and Mexico City have closed government-backed children’s homes, or significantly decreased their populations.

“A central consequence of COVID-19 is that families are more fragile,” she says. But she also sees the pandemic accelerating changes that experts have long known are needed. Internationally, there’s a growing recognition that children taken from their families and placed in orphanages or children’s homes risk long-term consequences, from developmental delays to an increased likelihood of falling victim to violence.

In Mexico, the pandemic’s effects on many families have increased the need for financial support. Globally it’s been far more common for children to lose one parent, not two. In Mexico, over 80,000 children are estimated to have lost a parent – mostly fathers, who are often the breadwinner.

Last winter, as Mexico tallied among the highest death tolls in the world, Alejandra Haydee Cardenas Olmos and her husband, José Ángel Sánchez Cabrera, hunkered down at home in Guanajuato, taking precious time off as a taxi dispatcher and driver. As debts began to pile up, Mr. Sánchez Cabrera returned to work to keep the family afloat, and died soon after.

Colleagues pooled money to help pay funeral costs, and relatives knocked on the door with a few thousand pesos or food. Even so, economic challenges overshadow much of their family’s life. Ms. Cardenas Olmos shudders to imagine a scenario where she and her three children might have lost their home or even been separated. “I need my children more than ever,” she says. “I can’t do [this] alone.”

The federal government has made children whose parents died of COVID-19 eligible for small cash grants, to help keep them in school, and local authorities have also provided a little help. But the couple’s eldest, Fernanda Lisabet Sánchez Cardenas, who is in her early 20s, was overwhelmed by the bureaucracy. “The government supposedly has these programs to help, but they put up so many obstacles; it’s like the [policies] are designed so that no one can access the help,” she says.

“She’s not the only one”

Rachel Kidman, a social epidemiologist at Stony Brook University in New York who co-authored the JAMA Pediatrics report, has done most of her research on orphans of the AIDS and HIV epidemic. She says the best outcomes result from “cash plus care” programs that offer both financial and emotional assistance, and often when they focus on the entire family.

“Even though you’re trying to help the child, the best focus may not be the child but the family. Because if the family can be that rock for the child, the child has better outcomes,” she says. “I do think a lesson for the U.S., for Mexico, for India is this idea of strengthening the family.”

She and co-authors have called on the U.S. government to task an institution – like the Department of Health and Human Services – to collect names of children who have lost caregivers to COVID-19 and make sure they receive benefits, such as Social Security, to which they are entitled. They also believe a federal point person for bereaved children could help lobby for financial and psychological support.

So far, for many American families, coping has been ad hoc.

Diana Ordoñez, in New Jersey, is one young widow who has relied on support from her church and found her way to the “Young Widows and Widowers of Covid-19” support page on Facebook. A year after her husband’s death, her 6-year-old daughter, Mia, relies on a collection of keepsakes – a tear bottle, a dream catcher, and the wedding photos of her parents she put on her dresser – to help her find the courage to fall asleep each night. “She’s just afraid that things will happen that she has no control over, that her whole world could change overnight,” Ms. Ordoñez says.

Recently the grief has felt heavier as life returns to normal in the U.S. – without Juan at their side.

“It’s been really lonely, this feeling like, ‘This wasn’t supposed to happen to us,’” she says. “I think for Mia, it will be helpful to her one day, hopefully, to know she’s not the only one, that she can talk to another kid that loved their dad and lost their dad too. I think that feeling that you’re less alone makes a big difference.”

Democracy under strain

‘The signs are there.’ Is US democracy on a dangerous trajectory?

In the first in a series of conversations about how to preserve democratic institutions, the Monitor interviewed the organizer of an open letter signed by some 200 scholars warning of threats to U.S. democracy. We asked his opinion about what makes for free and fair elections, and how to bolster the system going forward.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Today the Monitor begins a periodic series of conversations with thinkers and workers in the field of democracy – looking at what’s wrong with it, what’s right, and what we can do in the United States to strengthen it.

Lee Drutman is a senior fellow in the Political Reform program at New America, a Washington think tank. This spring he was one of the main organizers of a letter signed by nearly 200 democracy scholars calling for greater federal protection of voting rights. The impetus for the effort was the Republican push in many states to pass new voting bills, including restrictions on voting methods preferred by Democratic-leaning constituents, the granting of new authority to partisan poll watchers, increased legislative control over local election officials, and fines for poll workers who make mistakes or overstep their authority.

These changes are “transforming several states into political systems that no longer meet the minimum conditions for free and fair elections,” the letter states. “Hence, our entire democracy is now at risk.”

In his book, “Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop,” Mr. Drutman proposes increasing the number of major political parties in the U.S. The two-party system “turns politics from a forum where we resolve disagreements into a battlefield where we must win and they must lose,” he writes.

‘The signs are there.’ Is US democracy on a dangerous trajectory?

Today the Monitor begins a periodic series of conversations with thinkers and workers in the field of democracy – looking at what’s wrong with it, what’s right, and what we can do in the United States to strengthen it.

Lee Drutman is a senior fellow in the Political Reform program at New America, a Washington think tank founded in 1999. This spring he was one of the main organizers of a letter signed by nearly 200 democracy scholars calling for greater federal protection of voting rights. The impetus for the effort was the Republican push in many states to pass new voting bills, whose provisions include some restrictions on voting methods preferred by Democratic-leaning constituents, the granting of new authority to partisan poll watchers, increased legislative control over local election officials, and fines for poll workers who make mistakes or overstep their authority.

GOP-led electoral changes in battleground states are, among other things, “transforming several states into political systems that no longer meet the minimum conditions for free and fair elections,” the letter states. “Hence, our entire democracy is now at risk.”

Mr. Drutman’s most recent book, “Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop: The Case for Multiparty Democracy in America,” argues that increasing the number of major political parties in the U.S. could diffuse the extreme partisanship that currently bedevils the country’s politics and produces legislative gridlock in Washington.

The two-party system with winner-take-all elections “leads us to see our fellow citizens not as political opponents to politely disagree with but as enemies to delegitimize and destroy,” he writes. “It turns politics from a forum where we resolve disagreements into a battlefield where we must win and they must lose.”

This conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

You were one of the primary organizers of the democracy scholars’ letter, warning of the deterioration of democracy in the U.S. How did that come about?

There is a real sense of anxiety among a broad community of scholars who have studied democracy for a long time, both domestically and around the world. And there are certain, pretty consistent patterns of democratic decline you can see if you study this stuff and understand what the basics of democracy are. What happens when one party stops believing in the idea that there’s a legitimate opposition?

There’s a real sense of urgency, I think. And we’re having a lot of debate about voting reform, and we felt it was important for folks to know the context that people who think about this for a living can provide. It seems like many people are thinking about democratic collapse something like the way we were thinking about COVID-19 in January of 2020 – the sense that it can’t happen here because we’ve never had something like that, or that it’s something that happens in other countries.

But you know, the signs are there.

There have been a lot of open letters from different professions and academic disciplines over the last year or so. Do you think this will lead to concrete change? And if not, what’s the purpose?

Maybe it’ll change votes; I don’t want to rule out that possibility. But I think the point is to communicate a sense of the stakes and to articulate something that a lot of people are feeling in an authoritative, potentially forceful way.

You write that several states are transforming their political systems to the point where they “no longer meet the minimum conditions for free and fair elections.” Which states are those?

We’re thinking about what’s happening in Georgia and in Texas – though the new voting law in Texas hasn’t yet passed.

What is the definition of a free and fair system? It’s a system in which all voters count equally regardless of which party they support, or their race or ethnicity, or any other characteristic. Where both parties have an equally fair chance of winning.

When you tilt the playing field decisively in one direction or another, and give power to partisan legislators to override and intimidate election administrators, that does not meet the conditions of a free and fair democracy. It’s not a hard and fast line. But the trends are all in the direction of making free and fair competition harder, putting thumbs on the scale, in Iowa, Arkansas, Montana, and so forth.

The letter focuses on statutory changes, election procedures, vote certification, and other rules. But the impetus for many of these changes was former President Donald Trump’s unfounded claim that the 2020 election was stolen. What’s the bigger danger to democracy – bad rules, or people operating in bad faith?

That’s a good question. It’s a little bit of both.

Democracy depends on both rules and norms. And you can have good rules, but if you have people who are intent on abusing those rules or changing them, there’s only so much the rules can do. On the other hand, the rules can also put some hard constraints on what people can get away with.

There’s an argument that if a party is truly intent on election subversion, there are limits to what the rules can accomplish if that party has power. And we see that time and again, in countries around the world. Plenty of powerful parties break and bend and rewrite the rules. So that is a fundamental challenge. But at the same time, you wouldn’t say we shouldn’t have any rules, right?

Your most recent book is titled “Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop.” Why do two major parties in a big country create a “doom loop?”

We have in the U.S., really for the first time in decades, two truly nationalized parties with no real overlap. For the first time, it’s a really genuine two-party system. And the fight is over national identity. It’s over the story of America. It’s over who we are. And that has created this incredibly high-stakes conflict in which we have closely fought elections. There’s an incredible amount of demonization and negative partisanship, which is creating a politics in which winning elections is more important than preserving fair rules of the game.

Democracy is a system that relies on parties being able to lose elections and a set of rules surrounding elections that all sides agree are fair and impartial. When you lose that, it just becomes a matter of competing force. Democracy is a way of resolving disputes without violence. But if you can’t agree on the rules, then violence becomes the way that you enforce things. And that’s the dangerous trajectory that we’re on.

What you propose is taking this political polarization and diffusing it among more political parties? Is that right?

Yeah. Exactly.

Essentially, the problem is that [right now] the way that parties win is by being the lesser of two evils, and by demonizing their political opponents, because that’s the unifying force in parties and it works. But you’ve never heard the phrase “lesser of three evils” for a reason.

If you look at multiparty elections, candidates and parties have to stand for policy. They can’t just get by on attacking the other side as extremist and dangerous.

In a multiparty system, parties form coalitions and work together on different issues. If you want to have a sustainable political system, you need to have constantly shifting allegiances – you can’t have permanent enemies. And there’s something about the binary condition that really triggers this kind of us-against-them, good versus evil, thinking.

There wouldn’t necessarily be less overall conflict in such a political system, right? It would just be spread around – say, between an ethnonationalist right-wing party and a conservative libertarian party, or between a progressive party and a center-left party?

Right, you have shifting conflict. Politics is about conflict, because the issues that we agree on are not political issues, and elections are not about the issues that we all agree on; they are about the issues that we disagree on.

With multiple parties, you can form different coalitions and you can have logrolls [the trading of favors], you can have positive sum deals. It changes the dynamic.

People might be more open to jumping between different parties – as happens in other multiparty democracies – and considering different ideas. And it’s not a threat to their identity. They might be more likely to encounter people from different parties in day-to-day life.

But there’s plenty of evidence that democracies with single-member legislative districts and winner-take-all voting inevitably tend toward a two-party system. Is there a way around that?

Proportional representation. [Note: This is an electoral system in which the number of seats held by a political group in a legislature is determined by the percentage of the popular vote it receives.]

If you have single-member districts as we do, you’re probably going to have two parties. But if you have larger districts, you can have proportionality, and you can have more parties. We can have multimember districts in the U.S. House; it’s totally constitutional.

Wouldn’t an anti-democratic ethnonationalist party remain a force under this system? That’s what we’ve seen in Europe.

They would be a powerful force, but they might break up into different groups, some of which are more anti-democratic than others. The dynamics would be different. You’d still have an ethnonationalist faction similar to the AfD in Germany. But the faction would be more isolated and it would be easier for the other groups to organize against it.

On their own, they would be a distinct minority. And they should be! You’ve got to give the pro-democracy supermajority in America a chance to organize.

How your cloud data ended up in one Virginia county

When you think of America’s tech capital, you probably envision Silicon Valley. But the home of data storage and cloud computing is actually in a bucolic town in Virginia that was once farmland. It’s an example of how the information economy can fundamentally transform a nonurban area.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

If you’ve ever wondered where “the cloud” is, that mythical-sounding repository for our collective mass of online data, you can stop your search here in the small Virginia city of Ashburn.

This town and surrounding Loudoun County are now home to the highest concentration of data centers anywhere in the United States. Computers in these box-shaped buildings here are likely storing chunks of your data – from text messages to photos and videos.

What’s known here as Data Center Alley is no rival to Silicon Valley, but it reflects how the area around Washington, D.C., has become a tech hub in its own right. The roots here date back to the early origins of the internet.

Not everyone appreciates the data centers. “They’re destroying what was really nice about Loudoun County,” says local resident Susan Louis.

Still, their presence has meant 12,000 jobs and billions in tax revenue. “Twenty years ago, this was farmland; this was like driving to the moon,” says John Day, vice president of sales and leasing at Sabey Data Center. “Right now, it’s one of the wealthiest ZIP codes and wealthiest counties in the entire United States.”

How your cloud data ended up in one Virginia county

If you’ve ever wondered where “the cloud” is, that mythical-sounding repository for our collective mass of online data, you can stop your search here in the small Virginia city of Ashburn.

This town and the surrounding former farm fields of Loudoun County are now home to the highest concentration of data centers anywhere in the United States. Computers in these box-shaped buildings here are likely storing chunks of your data – from text messages to photos and videos.

The internet is everywhere, but its data is here in Loudoun County (first syllable rhymes with “cloud,” second syllable with “done”). It’s no rival to Silicon Valley as a hub of innovation, but what’s known here as Data Center Alley symbolizes how, even for the widely dispersed global internet, businesses tend to locate in clusters. One data center begets another. In this case more than 100 in all, with roots dating back to the nearly forgotten firm Netscape, one of the internet’s early linchpins.

With the pandemic spurring online activity, the cloud computing industry raked in $270 billion globally last year, with predicted growth of 23% this year, according to the research firm Gartner.

Being a tech hub can place a symbolic target on this region’s back. A supporter of a Texas-based militia group recently pleaded guilty to plotting to blow up an Amazon data center in Ashburn. And even when the warehoused computers are just chugging smoothly along, not everyone living in this county appreciates the changes brought on by Big Tech. Still, the spread of data centers has meant 12,000 jobs, billions in local tax revenue, and a boost for local income growth.

“Twenty years ago, this was farmland; this was like driving to the moon,” says John Day, vice president of sales and leasing at Sabey Data Center, during an interview in the company’s gated data center. “Right now, it’s one of the wealthiest ZIP codes and wealthiest counties in the entire United States.”

With per capita income surging past $55,000 in recent years, Loudoun County has been outpacing the state of Virginia and the nation economically. It retains its share of bucolic scenery, vineyards, and the farms that once were a “breadbasket of the Revolution” for the region’s role in feeding George Washington’s Continental Army. But its growth as part of the D.C. metro area has coincided with the rise of big data centers run by the likes of Amazon, Microsoft, and Google.

“They’re destroying what was really nice about Loudoun County,” says Susan Louis, a local resident for nearly 30 years, of the data centers, as she walks with her husband near a pond and vegetable garden next to Loudoun’s Farm Heritage Museum.

Why Loudoun County?

To understand the transformation, a brief primer on internet history is needed.

The idea behind the World Wide Web traces its roots to U.S. Department of Defense funding, and a key internet traffic “exchange point” called Metropolitan Area Exchange-East, which was located in northern Virginia.

In 1995, Netscape went public as a company that pioneered the concept of web “browsing” in the early days of the commercial internet. By the late 1990s, both the MAE-East infrastructure and America Online (acquirer of Netscape) were based in Loudoun County.

The exchange point coupled with available electric power, water, and fiber-optic connections made the Ashburn area an ideal location for data centers.

Mr. Day of Sabey Data Center calls the cloud simply “somebody else’s computer.” He explains a process in which information, such as a YouTube video, is stored in multiple locations around the world. A request for that information will procure the closest copy of that information from the cloud.

Behind the gates of the Sabey Data Center are gated racks of computer servers where information is held. No one here can access the information on the servers. The center just maintains the computers and the massive power supply and cooling mechanisms that they need. Multiple companies house their servers at Sabey.

The three major players in the U.S. cloud computing industry today – Amazon, Microsoft, and Google – have each invested billions in Loudoun. Amazon Web Services leads the way with about 65% of the U.S. market, according to a 2019 estimate by the research firm Gartner.

“They were here first and they’ve grown fast,” says Buddy Rizer, executive director of Loudoun County Economic Development since 2007.

Federal agencies are not required to report their cloud service provider, but Mr. Rizer calls the federal government the “world’s largest customer,” a major factor driving the industry’s growth.

There has not been a single day without data center construction in Loudoun County in over 13 years, the county’s development office says.

The dollar benefits are clear. Data centers have financed roads and other needs, while reducing the tax rate for a growing population. They’ll account for an estimated $500 million in local tax revenue this year alone.

Yet the companies here are also vying fiercely for marketplace power, not so coincidentally in the backyard of the federal government.

The cloud, in the fluffy imagery of its name, “obscures the fact that this is a hard-nosed business run primarily by a few giant tech companies,” wrote several cyber experts in an article on the national security blog Lawfare last year. Amazon Web Services, for instance, has been involved in a multiyear lawsuit disputing a $10 billion cloud computing contract the Defense Department awarded to Microsoft in 2019.

Big money and residual effects

Even as the companies have competed and brought money and jobs to Loudoun, area residents have not all been on board with the multiplying data centers.

“From the economic point of view, [data centers] may help Loudoun County,” says Patricia Larsen, “but they’re simply ugly and they keep popping up everywhere.”

Ms. Larsen, interviewed in Loudoun’s Claude Moore Park while she held her motorcycle helmet, lived in Loudoun County before moving to adjacent Fairfax County a few years ago.

“Any regular person, when they’re driving by, it’s like commercial after commercial after commercial building, and it’s just not appealing,” says Ms. Larsen, who noted one blue and yellow data center that looks like an Ikea store.

For Edwin Santamaria, a Loudoun County resident for about 24 years, it’s been “life as usual” with the increase of data centers in the county.

Not so for Chris and Susan Louis, both in real estate, who have had enough of the data centers. Loudoun residents for nearly 30 years, the couple are planning to move.

“We’re literally surrounded,” says Mrs. Louis, who attributed a low cicada-like hum to the data centers. She acknowledges the tax advantages for the county, but is disappointed that there are so many of the centers.

Mr. Rizer, seated in an office that overlooks a data center campus, says overseeing the development has been a “tremendous ride.”

“If the industry itself is in the second or third inning of growth, we, in Loudon County, are probably in the bottom of the eighth or top of the ninth,” says the former collegiate baseball player.

This county’s story is instructive. Mr. Rizer fields inquiries from other municipalities about how to become the next Data Center Alley. He predicts the industry is “going to continue to grow exponentially, nationally and internationally” with data centers being more dispersed geographically. He acknowledges the critiques about the look of some of Loudoun's early data centers, and says the county has “zero interest” in putting data centers in its more rural western section.

"It's really a new industry," he says, "so we're learning as we go along.”

Croatia needs tourists, but are tourists ready to return to Croatia?

Last week, a friend sent me a surprising photo: His 3-year-old daughter was sitting on an iron throne. The pic was taken at a set in Croatia where “Game of Thrones” was filmed. The TV series spurred tourism to the European nation. Then the pandemic hit. Now Croatia is hoping that more “Game of Thrones” fans like my friend will revive its tourism-dependent economy.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The pandemic made 2020 a brutal year for most countries economically. But it was particularly tough for Croatia, where tourism accounts for 20% of the gross domestic product of a country that rebuilt itself after a devastating civil war.

Croatia saw its best tourism year yet in 2019, capping a decadelong boom in which it joined the European Union, only to see revenues plummet during the pandemic. Now, the West is beginning to get back to some sense of normalcy, and the summer tourist season can’t come a moment too soon for Croatia.

At his Italian restaurant in Split, Roberto Popowicz is also ready for tourists. Opening hours were cut 80% to 90% during the pandemic and he was forced to let go some staffers, even after borrowing money to keep Trattoria Tinel open.

“It was very, very stressful,” says Mr. Popowicz, surveying the indoor and shaded outdoor patio tables that typically serve up grilled squid and fish. But he’s hopeful for 2021.

“Croatia is first of all a tourist country, and many other industries are connected directly and indirectly with Croatian tourism,” says Kristjan Staničić of the Croatian National Tourist Board. “I think we can do even better in the future. I think that the comeback kid could be in 2023.”

Croatia needs tourists, but are tourists ready to return to Croatia?

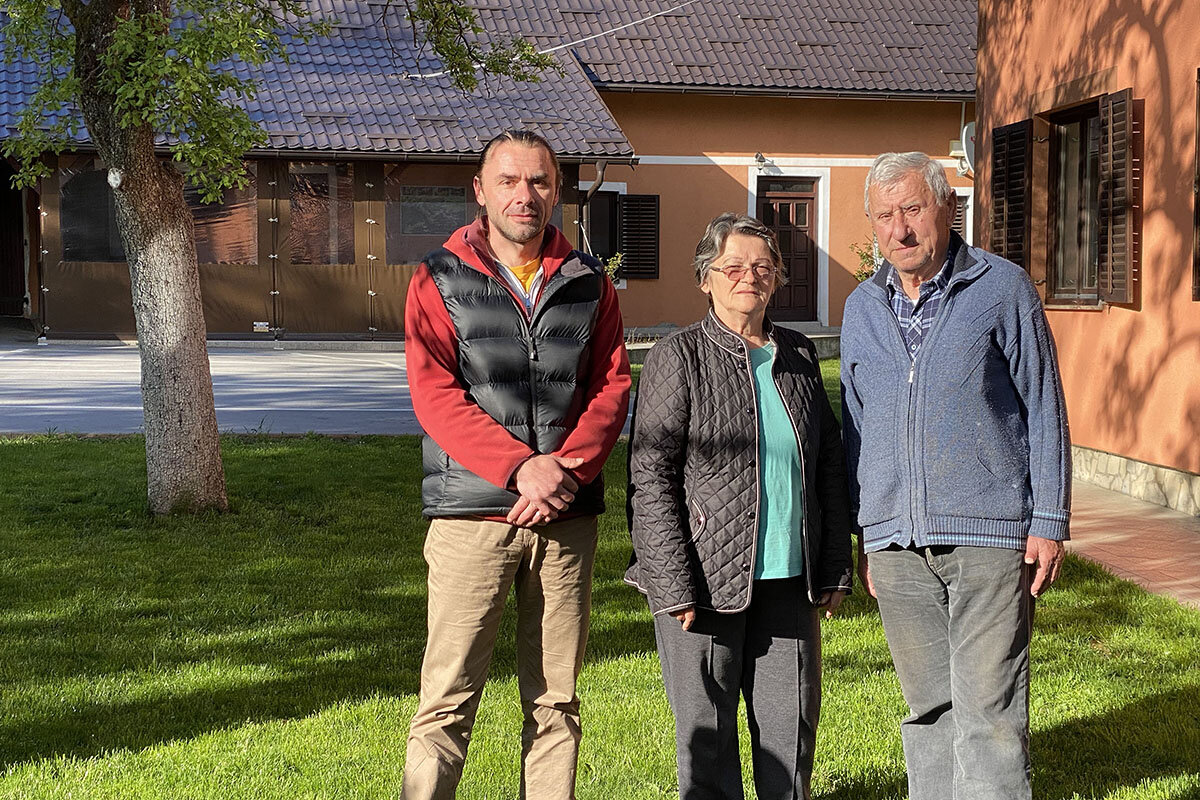

Dusko Glumac’s personal history tracks Croatia’s route on the global tourism scene.

A teenager when the Yugoslav civil war broke out in 1991, Mr. Glumac was sent from this northern Croatian village to Belgrade, in Serbia, to finish school. His father – who’d worked as a server at ex-Yugoslavian leader Tito’s nearby lakeside villa – and his mother stayed behind to tend to the family’s bed-and-breakfast.

Soon enough, his parents left too, and regiments of the Croatian army took shelter in their property at the height of the war. Years later, the Glumac family trickled back home to find a land mine in their dining room and their belongings looted.

“We had to rebuild everything bigger and better,” says Mr. Glumac of the boutique hotel business his grandfather started in the 1960s at this crossroads to Eastern Europe. Rebuild, the Glumac family did, restoring walls and windows, and over time upgrading the three-story main house with the addition of playgrounds and a gazebo. Over the past two decades, travelers from all over the world have visited their small property situated in the UNESCO-designated Plitvice Lakes region. KAL launched direct flights from Seoul, South Korea, to the nearby capital, Zagreb. Mr. Glumac met and married a Taiwanese woman.

Then the pandemic struck, challenging not only the family business but also Croatia’s newfound identity in the tourism world. The European country most dependent on tourism, Croatia had seen its best year ever in 2019, capping a decadelong boom in which it joined the European Union. Last year, tourism revenues plummeted by 90%.

Now, as the U.S. and Europe return to some sense of normalcy, the new tourist season can’t come a moment too soon for Croatia. With United and Delta opening direct routes in July from New York and Newark, New Jersey, to Croatia, and Europeans also on the move again, summer could bring back the tourists that the country is counting on to fuel a much-needed rebound.

“Croatia is first of all a tourist country, and many other industries are connected directly and indirectly with Croatian tourism,” says Kristjan Staničić, director of the Croatian National Tourist Board. “Most important in the moment right now is to focus, to improve the [pandemic] situation in Croatia” so more people will come, he adds. “I think we can do even better in the future. I think that the comeback kid could be in 2023.”

Croatia’s geographical advantages leap out from a glance at a map.

The country occupies almost the entire length of Adriatic Sea coastline opposite Italy. Between the medieval walled city of Dubrovnik in the south and capital city of Zagreb in the north stretch world-class scenery, rambling mountain ranges, lake regions replete with hiking, vineyards and olive groves, local cuisine, and historical depth to rival the rest of Europe.

“For a country that was part of a devastating Balkans war, to turn itself around to become a real hot spot for international travelers is quite a feat,” says Lloyd Figgins, a Britain-based travel risk consultant. “Croatia benefited from a real willingness to shake off the shackles of being associated with a terrible European war, a willingness of the people to really tell the world what they’ve got.”

And the world came. Made famous as the setting for “Westeros” in the smash-hit HBO series “Game of Thrones,” Dubrovnik began docking hundreds of cruise ships a year, and unleashing tens of thousands of passengers a day into the tiny town of 40,000. Countrywide, Croatia logged more than 400 million overnight stays in 2019; a handful of restaurants earned Michelin stars.

Then, 2020 brought only a tenth of the previous year’s business, a brutal blow to a country where tourism makes up nearly 20% of gross domestic product. While hotel chains and tour operators waited, some took the time to regroup.

“Before the crisis we were complaining about mass tourism,” says Ružica Herceg, managing partner of Zagreb-based Hotel & Destination Consulting. “And, maybe we should lift it to more higher quality supply. We need more investment and infrastructure and higher-quality projects.”

Some operators took the time to develop areas that lagged behind Croatia’s competitors, such as “experiential” packages that focus on aspects of local culture, or involve activities like kayaking and cycling. Sustainability is also a growing focus for a country hoping to minimize environmental impacts of having so many tourists, and the government is especially keen to draw tourists to inland lakes and mountain areas, away from the highly trafficked beach destinations.

If tourists can drag themselves away from the beach, they “can capitalize on a great opportunity to see a beautiful country, perhaps without the crowds,” says Mr. Figgins.

The waiting game

A ferry ride away from the beach town of Split, Marko Franulic sits on the island of Brac. He is waiting for tourists.

In 2019, almost 3,000 guests graced his stone patio, tasting his family’s olive oil and wines. He used to sell 90% of the family’s annual production, bottle by bottle, to visitors. This year, he had hosted only two groups of tourists by mid-May.

Mr. Franulic has vats of olives and crates of wine with nowhere to go. But he’s optimistic. This year he sees lots of grapes on the vine, and he hopes pandemic restrictions will be lifted in time to invite friends from the mainland to help with the annual harvest.

“If we have more friends we finish by 4 p.m. If not so many friends we finish at 7 p.m.,” says Mr. Franulic. “Then we eat.”

Back on the mainland, at his Italian restaurant in Split, Roberto Popowicz is also ready for tourists. He slashed opening hours by 80% to 90% during the pandemic and was forced to let some staffers go, even after borrowing money to keep Trattoria Tinel open. “It was very, very stressful,” says Mr. Popowicz, surveying the shaded outdoor patio tables where he typically serves up grilled squid and fish. But he’s hopeful for 2021.

And in Jezerce, Mr. Glumac waits too. As a boy, before the civil war, his world was confined to a small village school. Today his life is full of cultures brought together from all over the world. He and his Taiwanese wife are expecting their first child together. Tourists are starting to book again.

Mr. Glumac has put his property expansions plans on hold, but hopes to eventually build a home for his young family. In the meantime, while he can, he’s enjoying the natural beauty of the surrounding lakes, without the tourists.

“For an enjoyable time, I spend time in silence,” says Mr. Glumac. “I hear the birds; I walk along streams and look for river shrimp; I search for mushrooms. I just listen to the silence.”

Books

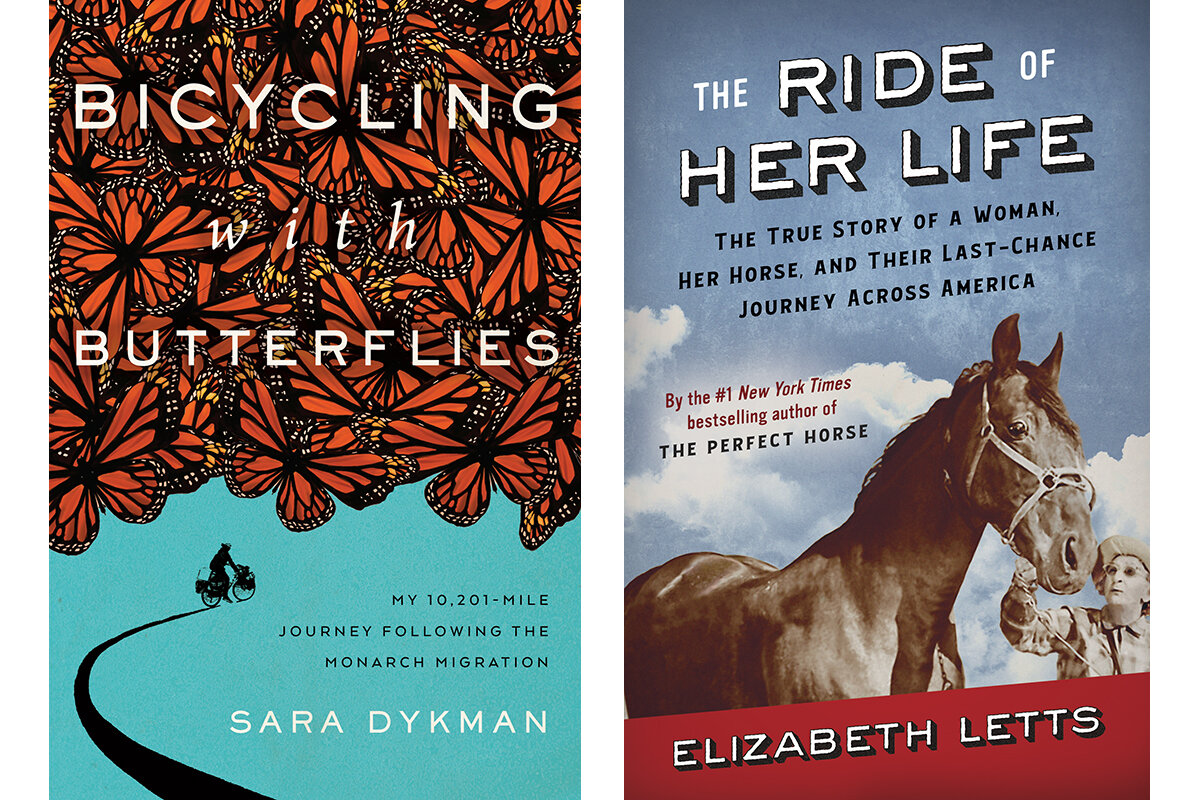

Women on a mission: Life-changing adventures by horse and bicycle

What kind of courage does it take to strike out on an epic cross-country trek alone – and without a car? Two new nonfiction books describe unusual journeys by two women, whose stories take place 50 years apart. They’re stories of resilience and self-discovery.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Olive Fellows Correspondent

In the not-so-distant past, an American woman traveling alone was viewed as suspect. She was judged for having loose morals or castigated for attracting undue attention from men.

Yet in the 1950s, a woman in her 60s named Annie Wilkins defied this narrow view and launched a purposefully meandering, 16-month journey by horseback across the United States, making friends wherever she went.

In 2017, another intrepid woman, Sara Dykman, followed migrating monarch butterflies on her bicycle, lodging with and befriending people along the way.

During her trek, Dykman highlighted the monarchs’ plight, giving presentations at schools and explaining her mission to curious bystanders.

Women on a mission: Life-changing adventures by horse and bicycle

The spark of an idea morphs into a mission. The open road calls and a cross-country road trip is born. Two new books tell true stories of long-distance travelers – women who were determined and moving with purpose – who wouldn’t let obstacles stand in their way.

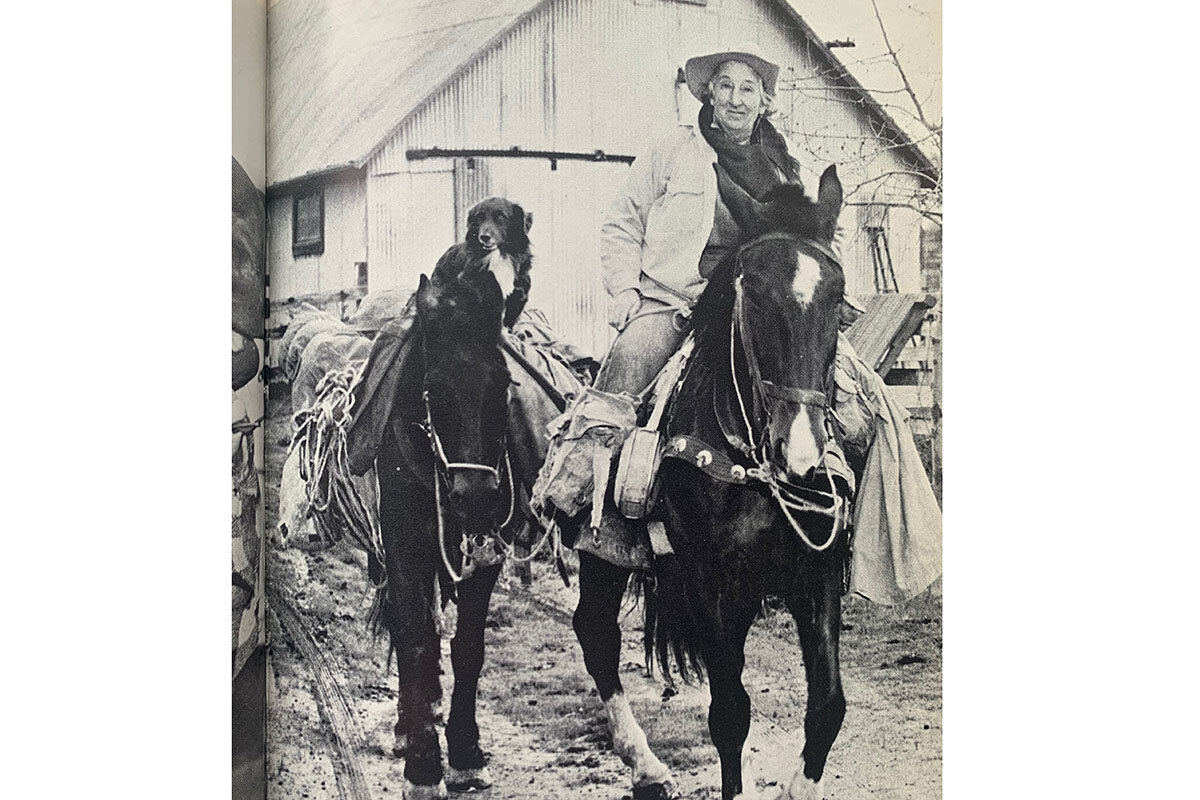

In November 1954, Annie Wilkins, who was in her 60s, embarked on a solo journey – on horseback – from her hometown of Minot, Maine, to California. Her cross-country trip is the subject of “The Ride of Her Life: The True Story of a Woman, Her Horse, and Their Last-Chance Journey Across America,” by Elizabeth Letts, author of “The Eighty-Dollar Champion” and “The Perfect Horse.”

With barely any money and her family’s farm all but lost, Wilkins also faced a diagnosis of a terminal illness. Proud woman that she was, she couldn’t bear to be a burden. Her plan was to gather her remaining cash and spend two years on the road, heading toward the shores of California where she dreamed of living out her final days.

Her travel companions included a strapping horse named Tarzan and her dog, a mutt named Depeche Toi (French for “hurry up”). Total strangers along her route – which Wilkins figured out as she went along – were eager to offer food and shelter to the woman the press dubbed the “Widow Wilkins.” In rural areas, she sometimes slept in a barn with the animals. In other locations, authorities helped her find a stable.

Her health problems lingered throughout the trip, but she soldiered on. She faced poor weather conditions in the two winters she was on horseback, and she also had close encounters with newly ascendant automobiles. There were other setbacks, including accidents and tragedies of the equine variety that almost ended her trip.

While chronicling each leg of Wilkins’ journey, Letts provides ample, if occasionally distracting historical context, bringing the people she met and the places she visited to life on the page. A longtime equestrian herself, Letts touchingly communicates the connection between Wilkins and her horses over the nearly 16-month-long odyssey. “The Ride of Her Life” also serves up a hearty helping of Americana: Readers will enjoy a glimpse of the country at midcentury.

Following the monarch migration

A different, more modern trek shows that the public still rallies behind a person with a mission. Through most of 2017, wildlife biologist Sara Dykman followed migrating monarch butterflies on her bicycle, lodging with and befriending people along the way. She pedaled from Mexico north to the United States and up into Canada, and then back south again. Dykman tells the story of her journey in her new memoir, “Bicycling With Butterflies: My 10,201-Mile Journey Following the Monarch Migration.”

Monarch butterflies wait out dangerously cold and wet winter conditions in Mexico until the spring, when they begin to move north in search of their sole food source, milkweed.

The famously orange-and-black insects also lay their eggs on milkweed plants so that their offspring have a ready food source. The annual migration ensures that monarch numbers are replenished after the winter, predators, and other dangers have taken their toll.

Climate change and habitat loss have left their mark. While monarchs have found homes across the globe and are at a low risk of extinction, their numbers are falling.

During her trek, the author highlighted the monarchs’ plight, giving presentations at schools and explaining her mission to curious bystanders. Her book is a passionate celebration of the glory of the monarchs, with tips on what people can do to ensure their survival. She also writes about the challenges she faced – problems all too common for an experienced long-distance cyclist: bad weather, flat tires, questioning by authorities, and, in the case of this trip, one uncomfortable human encounter.

In “Bicycling With Butterflies,” Dykman honestly and with great self-awareness tells her story. Hers was a deeply emotional journey, providing her with new families in the human and natural worlds. Such an outcome might seem improbable for a mere bike trip, but, as Dykman wisely observes, just like with the monarchs, “we often overlook the grandness of small things.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Time for the NCAA to redefine sports

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

It’s back to the locker room for the NCAA. On Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the body that governs college sports must not limit education-related perks for its athletes. In essence, the high court said the organization’s definition of “amateur” – which the nine justices put in quotes – needs a rethink. For now, the ruling implies that the National Collegiate Athletic Association may no longer prevent compensation to players under the cloak that it is protecting sports.

It is also the latest challenge to sports officials worldwide to ensure the integrity of sports. The United States, for example, has joined Europe and Asia in allowing gambling on sports – and in trying to fend off the influence of criminal syndicates on players, coaches, and referees. Cheating scandals have rocked many sports.

While sports bodies keep setting more rules to protect a “level playing field” in competitive sports, some have taken a different approach. The World Anti-Doping Agency has tried to define “the spirit of sport” to help athletes make the right choices.

So, yes, the NCAA and other sports bodies need to prep for a better definition of what is purity in sports.

Time for the NCAA to redefine sports

It’s back to the locker room for the NCAA. On Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the body which governs college sports must not limit education-related perks, such as computers or cars, for its athletes. In essence, the high court said the organization’s definition of “amateur” – which the nine justices put in quotes – needs a rethink.

For now, the ruling implies that the National Collegiate Athletic Association may no longer prevent compensation to players under the cloak that it is protecting sports. “The NCAA couches its arguments for not paying student athletes in innocuous labels,” Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote in a concurring opinion. “But the labels cannot disguise the reality: The NCAA’s business model would be flatly illegal in almost any other industry in America.”

The ruling comes as at least six states are moving to allow college athletes to make money from their names, images, and likenesses. That trend adds to the burden of the NCAA to stop defining the amateur status of its athletes mainly by what they are not – paid professionals. The court found little evidence that fans care much about whether athletes are paid or not.

The ruling is only the latest challenge to sports officials worldwide to ensure the integrity of sports. The United States, for example, has joined Europe and Asia in allowing gambling on sports – and in trying to fend off the influence of criminal syndicates on players, coaches, and referees. Cheating scandals have rocked many sports, especially in the use of enhancement substances, or doping. Pro baseball is now contending with pitchers who doctor balls to make them spin better.

While sports bodies keep setting more rules to protect a “level playing field” in competitive sports, some have taken a different approach. After the International Olympic Committee created the World Anti-Doping Agency, that body tried to define “the spirit of sport” to help athletes make the right choices. A special panel defined the spirit of sport to be “fair play and honesty, health, excellence in performance, fun and joy, respect for self and other participants, and courage among others.”

That sports even have ideals, or a purity free of material interests, is wrapped up in phrases such as “the love of the game” or “sport for the sake of sport.” Michael Sandel, who teaches political philosophy at Harvard University, defines athletics as gifted “talents and powers [that] are not wholly our own doing, nor even fully ours, despite the efforts we expend to develop and to exercise them.”

Athletic competitions, he argues, must “fit with the excellences essential to the sport.” Rules for sport must make sure sports do not “fade into spectacle, a course of amusement rather than a subject of appreciation.”

So, yes, the NCAA and other sports bodies need to get out their chalkboards and prep for a better definition of what is purity in sports, one that ensures they remain free of profit motives, drugs, and gambling.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Love that leaves no one out

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Lisa Troseth

Maybe we’re feeling unloved or excluded – or treating others that way, unconsciously or otherwise. But recognizing that everyone is included in God’s love brings joy and healing to our hearts and to our interactions with others.

Love that leaves no one out

A couple of years ago, when I logged on to Facebook one day, a photo immediately caught my attention. It was of a six-year-old boy named Blake wearing an orange T-shirt with a message in green letters that said “I will be your friend.” The article accompanying it explained that Blake had asked his mom to make him this T-shirt, which he wore on the first day of school so anyone who needed a friend would know they had one already. His story even went viral, inspiring other kids and adults to wear T-shirts like it.

This spirit of loving inclusion is so needed in our world. Too often, things come up that make us feel unloved, excluded, or alienated – or, on the flip side, that pull us to think or act in a way that isn’t loving or inclusive of others.

What I’ve been finding through my study and practice of Christian Science is that there’s a powerful basis for addressing such issues. At any moment, in all kinds of situations, we can pray to really realize we are all included in the love of God, who is infinite Love itself. Then we feel more strongly the divine loving presence that is God, expressed throughout existence, filling every moment.

Praying in this way not only elevates how we think and act, but also goes out to touch the hearts and lives of others as well.

New Testament accounts of Christ Jesus reveal he embodied the all-inclusive nature of God’s love without limit. His healing ministry included those on the outskirts of society, those who were shunned, those no one else would touch, those whose lives seemed ruined, and even those who hated him. The consistent result was healed and transformed lives.

Jesus’ example of living in unity with divine Love can help us recognize our inseparable oneness with Love, too. As it says in the Bible’s book of First John, “If we love each other, God lives in us, and his love is brought to full expression in us” (4:12, New Living Translation).

An experience I had has helped me see this more. I was in tears because some folks had left me out in ways I felt they were unaware of. But I began to pray, asking God to speak to me in a way I could genuinely grasp.

Then a tender feeling of love flooded my heart as I realized these individuals were designed to express God’s all-inclusive love. And this feeling of love expanded even further as more people came to thought, from my community and around the world. I found myself cherishing them as inseparable from divine Love, too.

This was so uplifting and joyful! I felt full of love – so at one with divine Love – where just a short while before I’d felt sad and excluded. I felt a closeness to everyone as I mentally honored our inseparable relation to God. Nothing in the world can stop the love that flows freely and impartially from God, divine Love, to all of us.

The sadness lifted completely. And it was lovely, too, that in the coming months several of the individuals I’d felt excluded by reached out and expressed a more thoughtful awareness about the situation.

The textbook of Christian Science, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, shares this insight on divine Love’s all-inclusive nature: “Love is impartial and universal in its adaptation and bestowals. It is the open fount which cries, ‘Ho, every one that thirsteth, come ye to the waters’” (p. 13).

When we think there’s a limited amount of love to go around, we run into all sorts of blocks regarding how and when love can be felt and expressed, who is worthy of love or not, or who is included or excluded. But the more we realize, through prayer, how infinite divine Love is, the more we see that no one could ever be excluded from the boundlessness of God’s loving embrace – and the more consistently our own interactions toward others reflect that.

Looking for more timely inspiration like this? Explore other recent content from the Monitor's daily Christian Science Perspective column.

A message of love

Cleared for landing

A look ahead

Thanks for spending time with our package of stories today. Tomorrow, we’re taking a look at how some elite public schools are redefining merit by scrapping entrance exams. But will the moves reduce opportunities for immigrant students?