- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Why stories of personal resilience are worth hearing

How can we credibly maintain hope in these times?

Consider the alarming narratives, both long-running and new: “cracks in the global order” and climate catastrophe, not to mention market woes and moon wobble. (Those are all from weekend headlines.)

Problems need to be exposed and confronted. But there’s inspiration in personal stories of adaptation and pushback. It’s real and worth reaching for. It fortifies and adds perspective.

Our new podcast, “Stronger,” resumes today with another profile in persistence. By the end of this week, it will have featured a half-dozen women who live and work at an epicenter of the economic upheaval wrought by a pandemic from which much of the world is only now kicking clear.

A colleague wrote last week about the openness and trust you can feel in this podcast – both in the empathetic approach to its reporting and from the women whose stories it tells. But there’s something else about our audio series, something intentional: It advances a counternarrative.

In covering the very real economic setbacks dealt to women, in particular, many outlets have gone in for full, bleak accounting. One major U.S. outlet burrowed into the “loss of self-determination, of self-reliance.” Another focused on lifetime costs of $600,000 to the “typical American woman.”

Losses and costs are not the whole story, though. There’s power and hope to be found in reinvention, in resourcefulness, in reaching out to help others. “Stronger” shows what resilience can mean.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

When a Nobel Peace Prize winner wages war, who loses?

What does a Nobel Peace Prize really represent – and how do you define “peace” in the first place? We look at why those questions have an especially sharp edge at the moment.

The Nobel Peace Prize may bestow winners with a saintlike aura, but it’s no stranger to controversy. Henry Kissinger’s win was so hotly debated that two members of the Nobel committee resigned. Barack Obama’s selection in 2009, after just one year in office, attracted criticism. 1991 laureate Aung San Suu Kyi has defended Myanmar against charges of genocide. And now, the war in Ethiopia’s Tigray region has intensified criticism of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who won the prestigious prize just two years ago.

The Tigray conflict has resurfaced long-standing questions that have long haunted the Nobel. How do you define peacemaking? Who deserves a prize for it? And what happens when the award is given to someone who goes on to wage war?

“There’s an inherent problem in the idea of giving a peace prize for starters because the bar is so high for successfully negotiating, agreeing to, and implementing peace,” says Leslie Vinjamuri, an expert on human rights and U.S. foreign relations at Chatham House in London. “Frequently in the toughest conflicts we see setbacks, returns to violence, returns to instability before you finally settle on stability. … We have to recognize that complex reality that peace is dynamic.”

When a Nobel Peace Prize winner wages war, who loses?

When Mulugeta Gebregziabher heard in October 2019 that the Nobel Peace Prize had been awarded to Abiy Ahmed, the new reformist prime minister of Ethiopia, his reaction was immediate dread.

“I thought, this is going to give this guy the legitimacy internationally to do whatever he wants,” says the Ethiopian professor of biostatistics, who now lives in the United States.

For Yonatan Fessha, an Ethiopian legal scholar at the University of the Western Cape in South Africa, the choice betrayed a startling lack of research.

“Someone closely familiar with the political dynamics of that region wouldn’t have given this award to Abiy,” he remembers thinking.

Nearly two years later, the chorus condemning the decision to give Mr. Abiy the award has swollen. Since November 2020, the prime minister – hailed by the Nobel Prize committee for giving Ethiopians “hope for a better life and a brighter future” – has been waging war on one of his own provinces, Tigray. There have been multiple documented massacres of civilians and the region is experiencing widespread starvation, much of it as a result of troops blocking humanitarian aid. Earlier this month, Mr. Abiy’s party was declared the winner of an election boycotted by two major opposition parties, and in which about a fifth of the country’s regions haven’t yet voted, poising him for a second five-year term.

The war and disputed election have resurfaced long-standing conversations about the decision to give Mr. Abiy the world’s most prestigious prize for peacemaking. And more generally, they have again raised questions that have long haunted the Nobel. How do you define peacemaking? Who deserves a prize for it? And what happens when the award is given to someone who goes on to wage war?

Nobel’s vision

“Any Nobel Peace Prize given to an individual bestows on that individual a very high legitimacy in the world – it’s one of the most prestigious prizes a person can win,” says Kjetil Tronvoll, a peace and conflict researcher at Bjørknes University College in Norway, who studies Ethiopia.

Yet the criteria for winning one are remarkably fuzzy, says Fredrik Heffermehl, a Norwegian peace activist and the author of “Fame or Shame? Norway and the Nobel Peace Prize.” Sometimes it goes to political leaders brokering an end to conflict and oppression at home: like Nelson Mandela and F.W. de Klerk, for ending apartheid and ushering in democracy in South Africa; or to Yasser Arafat, Shimon Peres, and Yitzhak Rabin, for “their efforts to create peace in the Middle East.” Other times, it’s given to humanitarians like Agnes Bojaxhiu, better known as Mother Teresa, a Roman Catholic nun who ministered to poor and dying people in Kolkata, India; or to activists like Malala Yousafzai, a Pakistani advocate for women’s education.

But Alfred Nobel, a Swedish inventor best known for creating dynamite, actually had a very clear vision of what he wanted his peace prize to reward, Mr. Heffermehl says. And it was neither local peace accords nor human rights activism.

In his will, Mr. Nobel wrote that the prize should go each year “to the person who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations, for the abolition or reduction of standing armies and for the holding and promotion of peace congresses.”

“It is not a do-good prize,” Mr. Heffermehl says. “It is not a prize for international friendship and understanding. It is specifically a prize for avoiding future wars through global cooperation and disarmament.”

Even those criteria, however, can be far from clear-cut.

“There’s an inherent problem in the idea of giving a peace prize for starters because the bar is so high for successfully negotiating, agreeing to, and implementing peace,” says Leslie Vinjamuri, an expert on human rights and U.S. foreign relations at Chatham House in London. “Frequently in the toughest conflicts we see setbacks, returns to violence, returns to instability before you finally settle on stability. … We have to recognize that complex reality that peace is dynamic.”

Despite Mr. Nobel’s will, the committee has long interpreted its mandate more broadly, as a prize for people reducing violence in the world. Still, many critics say it has tarnished the prize’s name by awarding it to people who were already embroiled in war, or would go on to be. In 1973, for instance, the prize went in part to U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger for his efforts to bring peace to Vietnam – even as a bombing campaign Mr. Kissinger had orchestrated was still ongoing in Cambodia. (Mr. Kissinger’s selection was so controversial at the time that his co-awardee, North Vietnamese leader Le Duc Tho, refused the prize, and two members of the Nobel committee resigned in protest.)

The 2009 prize was awarded to U.S. President Barack Obama, then commander in chief of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. And in 2019, just a month after Mr. Abiy won the prize, Myanmar’s heralded opposition leader and 1991 peace prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi stood before the International Court of Justice in The Hague to argue that the slaughter of an estimated 24,000 Rohingya was not a genocide, but a military action against terrorists and insurgents.

Prize as encouragement

As Mr. Obama noted after winning the award, “Throughout history, the Nobel Peace Prize has not just been used to honor specific achievement; it’s also been used as a means to give momentum to a set of causes.”

In Ethiopia, according to the Nobel committee, that “set of causes” included peace between Ethiopia and Eritrea and democratic reforms for Ethiopians, who had lived the previous three decades under an authoritarian one-party regime.

Mr. Abiy became head of that regime, but from the moment he took office, in April 2018, he set about loosening his government’s grip on its people, releasing thousands of political prisoners, negotiating a peace agreement with neighboring Eritrea, and welcoming back high-profile opposition political leaders from exile.

But even in the earliest days, observers say, there were signs that his reforms were not as positive for the country as they seemed – particularly when it came to reorganizing Ethiopian politics.

For nearly three decades, since the end of a brutal civil war, the country had been ruled by the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, a coalition of ethnically based political parties dominated by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front. After Mr. Abiy’s ascension, many Tigrayan leaders were sidelined, and the TPLF accused the government of unfairly targeting its leaders in corruption purges and leadership changes. When Mr. Abiy announced in late 2019 that he was forming a new party, the Prosperity Party, to succeed the EPRDF, the TPLF refused to join.

“The Nobel Prize emboldened Abiy to reform the internal political structure, which was the single most significant trigger for the war today,” Dr. Tronvoll says. “High-level party insiders have told me that in those negotiations he used the prize to basically say, ‘I have an international mandate to rule as I see fit.’”

Dr. Tronvoll recalls asking foreign diplomats why they did not comment as domestic reform started to backslide. He says he was told that Mr. Abiy was “untouchable.” That reluctance to criticize Ethiopia, he adds, endured well after the fighting began in Tigray.

Even as it gave Mr. Abiy the prize in 2019, the Nobel committee appeared to acknowledge doubts about his award.

“No doubt some people will think this year’s prize is being awarded too early,” the group wrote in a press release announcing his win. “The Norwegian Nobel Committee believes it is now that Abiy Ahmed’s efforts deserve recognition and need encouragement.”

Ultimately, it’s five individuals wrestling with “a really complex calculation that they clearly struggle with and reassess time and time again,” Dr. Vinjamuri says: when to award a peacemaking prize you can’t take back. “But I like that the prize is usually pretty bold,” she adds. “It’s sort of trying to be part of something, rather than just being purely a seal of approval for past deeds done.”

For Mr. Abiy, the peace prize may in the end be both a blessing and a curse. It “was an asset at the beginning; it won him many friends,” says Mr. Fessha. But in November 2020, after the Tigrayan government held local elections in defiance of a national postponement due to the coronavirus pandemic, fighting broke out, and quickly escalated. Since then, thousands (tens of thousands, according to Tigray’s opposition) have died, and more than 1 million people have fled their homes.

“Now he has become the Nobel Peace Prize winner who refuses to give peace a chance,” Mr. Fessha says. “And that label could be a liability.”

From Bezos to satellites, does new space era need new rules?

As billionaires boldly go spaceward, heralding more privatized off-world travel, new “principles” and ethics are being discussed and adopted. Does space also need more enforceable rules?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The excitement this month is palpable as doors open for more people to experience space travel. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos is set to launch tomorrow on the Blue Origin rocket with his brother as well as the oldest and youngest people ever to enter space. That follows a trip by fellow billionaire Richard Branson to the edge of space on July 11.

Yet with widening opportunities come ethical and practical concerns. How do you keep safe as human traffic increases along with more satellites, scientific experimentation, debris, and potential military activity?

In May, the uncontrolled reentry of a Chinese rocket caught the world’s attention about the challenges posed by space junk, including litter that remains in permanent orbit and can put spacecraft at risk. And in September 2019 a near collision between a SpaceX satellite and European Space Agency satellite in low-Earth orbit showed the lack of international guidelines on how to handle collision avoidance, according to a report by the research organization Rand Corp.

“There are very clear indications that space law, writ large, or space governance, if you want to use that term, is underdeveloped,” says retired Brig. Gen. Bruce McClintock of the U.S. Air Force, an author of the recent report.

From Bezos to satellites, does new space era need new rules?

“Roads? Where we’re going, we don’t need roads.”

The closing line from “Back to the Future” fits the moment as human spaceflight expands with a pair of billionaires blasting beyond Earth’s atmosphere – Richard Branson on July 11 and Jeff Bezos scheduled for tomorrow. But behind the high-profile commercial launches, a question looms: Are more rules of the road needed, metaphorically, for a trackless domain that is seeing a rapid increase in activity?

The excitement this month is palpable as doors open for more people to experience space travel. Amazon founder Mr. Bezos is set to launch on the Blue Origin rocket tomorrow morning with his brother as well as the oldest and youngest people ever to enter space.

Yet with widening opportunities come ethical and practical concerns. How do you stay safe as human traffic increases along with more satellites, scientific experimentation, debris, and potential military activity?

In May, the uncontrolled reentry of a Chinese rocket caught the world’s attention about the challenges posed by space junk, including litter that remains in permanent orbit and can put spacecraft at risk. And in September 2019 a near collision between a SpaceX satellite and European Space Agency satellite in low-earth orbit showed the lack of international guidelines on how to handle collision avoidance, according to a report by the research organization Rand.

“There are very clear indications that space law, writ large, or space governance, if you want to use that term, is underdeveloped,” says retired Brig. Gen. Bruce McClintock of the U.S. Air Force, who leads Rand's space enterprise initiative and is an author of the recent report.

From principles toward more rules?

Although principles for space have been discussed internationally for years – including an Outer Space Treaty dating back to 1967 that 110 nations have signed – existing protocols are often vague or growing outdated in an era of expanding space activity. The Rand report notes the risk of a “tragedy of the commons,” a term used when parties fail to care for a place because lines of responsibility aren’t clear.

Article VI of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty requires countries to “bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space” whether they be government-run or commercially operated.

Frans von der Dunk, a professor of space law at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, says the treaty dates back to when only nations explored space, primarily the U.S. and Soviet Union.

“The idea of commercial space flight, which is of course what Bezos is all about, was nowhere on the horizon [and] has not been dealt with in any detail,” says Dr. von der Dunk, speaking from the Netherlands, where he operates a space law consultancy company.

And while the U.S. adopted the Artemis Accords last October, with space principles such as peaceful exploration and transparency, the 18-page document is not legally binding.

When Mr. Bezos, who stepped down as Amazon’s CEO this month, boards his vehicle on Tuesday morning in West Texas for his suborbital flight, the United States will be held responsible for the activity under international law. His company, Blue Origin, is now one of many in the domain, including Mr. Branson’s Virgin Galactic and Elon Musk’s SpaceX, which launched astronauts for NASA earlier this year and operates hundreds of satellites.

“What they are doing is definitely hazardous,” says Scott Pace, who served as executive secretary for the National Space Council, a White House organization overseeing space activity that was reestablished in 2017 during the Trump administration.

It is up to would-be space tourists to realize that. “We have a very light regulatory regime where the major focus is making sure you don’t hurt anybody else outside the launch,” says Dr. Pace, now the director of the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University. For now he sees the need for “only modest evolution” in domestic law to account for increasing space tourism.

At a congressional hearing earlier this year about rules in space, Democratic Rep. Jim Cooper of Tennessee cited space traffic management, banning debris, and the size of safety zones as areas that potentially call for new international agreement.

He bridled at the testimony of State Department experts who, in his view, were “settling for suggestions-based space” instead of “a law-abiding rules-based space.”

“Perhaps that is the best we can do, but I think we should try harder for better,” said Representative Cooper, who chairs the House Armed Services Subcommittee, which oversees the space activity of the Department of Defense and the nascent Space Force. “There must be a consensus somewhere on Earth for the sensible.”

Can diverse nations agree?

Republican Rep. Michael McCaul of Texas says the Chinese Communist Party is defining space as another warfighting domain. “If left unchecked, the CCP will continue to use its influence in international organizations and over other countries to achieve dominance without regard to the security and sustainability of outer space,” says Mr. McCaul, in an email to the Monitor.

And while right now the tourism attention is on U.S.-based billionaires like Mr. Bezos, Dr. Pace says China has billionaires too. It is unlikely the commercial space market will remain so U.S.-dominated in the future.

He notes that the U.S. and China seem to “have a lot of common ground in things like space resources and coordinating with each other.” For those in the space business, he says it’s possible to see a cooperative arrangement.

Notably, however, while just last month Brazil became the 12th country to join the Artemis Accords, China and Russia are not signatories. Those two nations teamed up earlier this year to announce plans to jointly construct a lunar space station.

“How we operate in space does reflect our values,” says Dr. Pace, the executive secretary for the National Space Council when the Artemis Accords were adopted. And those operations have shifted.

The Artemis program, a NASA-led international effort to send the first woman and next man to the surface of the Moon in 2024, is a change of strategy from the Apollo program of the 20th century, Dr. Pace says.

“Leadership today is very different,” he says, “In the ’60s, it was all about what we can do by ourselves. Today, it’s who can we get to come with us.”

At Fellowship church, faith knows no creed or color

Shared beliefs can bind a community. A shared humanity that elevates acceptance of different beliefs can too. We look at a long-running “Christian experiment in democracy.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Maisie Sparks Correspondent

In the 1940s, it was anything but acceptable to have people of diverse races shoulder to shoulder in America’s church pews. But that didn’t sit right with Alfred Fisk, a Presbyterian clergyman, and Howard Thurman, the dean of the chapel at Howard University. Working with others, they formed The Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples in 1944 to see if spiritual unity and fellowship could trump the prejudices upholding the nation’s racial divide.

It did, and it still is.

“We don’t have a herd mentality; we have a shared humanity,” says the Rev. Dr. Kathryn Benton, co-pastor of Fellowship church.

Sunday services typically include familiar aspects of Protestant faith gatherings such as music and preaching. But the music might be an African drummer, and a Muslim imam may call the congregation to worship.

Fellowship church identifies itself as Christian, but since it is independent, the church can depart from denominational norms, including a single “right” set of beliefs. Members focus instead on having right behaviors toward all people. And they are welcome to belong to churches of other denominations as well.

For Fellowship church, in place of creed, denomination, or even a shared understanding of God is unity – with one another and with God.

At Fellowship church, faith knows no creed or color

For many in America, Sunday at 11 a.m. is the most segregated hour of the week. But that’s never been the case at The Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples in San Francisco. For the past 77 years, that sacred hour has been an interracial, interfaith, and intercultural experience meant to foster faithful community and find ways to affirm all people as children of God. Indeed, racial and religious openness were the very reasons for its founding.

“When I look out into the congregation, I see Black folks and white folks ... Latinx folks ... folks of various Asian heritages ... Jewish folks, and Buddhist,” says the Rev. Dr. Dorsey Blake, Fellowship church’s presiding pastor for the past 27 years. “Who’s in the pews – or over the past year, who’s checking in online – is just accepted and celebrated.”

But when Alfred Fisk, a Presbyterian clergyman, and Howard Thurman, the dean of the chapel at Howard University, started this experiment in the 1940s, it was anything but acceptable to have people of diverse races shoulder to shoulder in America’s church pews. Baptists had split in 1845 over the issue of slavery, and another break would come in 1880 when Black congregants formed the National Baptist Convention to gain a voice and the dignity that comes with it. And Baptists weren’t the only ones forming and reforming along racial lines. In the 1920s, the Pentecostal movement, originally formed as an integrated community in Los Angeles, succumbed to the forces of a segregated society and has remained so.

But in Fellowship church’s inaugural service in October 1944, Drs. Fisk and Thurman imagined a different reality. “The movement of the Spirit of God in the hearts of people often calls them to act against the spirit of their time or causes them to anticipate a spirit which is yet in the making,” wrote Dr. Thurman in “Footprints of a Dream,” which chronicles the church’s founding.

Following that calling, the two men joined with leaders from Presbyterian, Baptist, Methodist, Episcopalian, and Congregational faiths – and with individuals from white, Black, Asian, and Jewish heritages – to see if spiritual unity and fellowship could trump the prejudices upholding the nation’s racial divide.

How is this “Christian experiment in democracy” holding up today? It depends on how you define a community of faith – whether you prioritize a diverse community or a particular belief.

“Often people think of community as joining together like-minded people, but I think it’s just the opposite here,” says the Rev. Dr. Kathryn Benton, co-pastor of Fellowship church. “We don’t have a herd mentality; we have a shared humanity. We honor the sacredness of the personality and the need for community. The word that comes to mind for me when thinking about our church is acceptance.”

Independence grounded in inclusivity

Sunday mornings under Fellowship church’s distinctive bell tower include typical aspects of Protestant faith gatherings such as music and preaching. But the music might be an African drummer instead of a choir, and a Muslim imam may call the congregation to worship rather than a minister. Liturgical dance is not out of place in a morning service, neither are extended periods of silent meditation. After the Sunday service, members carry on a long-standing tradition of gathering for a meal and talking for hours because there is a lot to learn about each other.

Since it is independent, Fellowship church has the freedom to depart from denominational norms, including a single “right” set of beliefs. Members focus instead on having right behaviors toward people of every race and creed.

“People here grew up in various denominations and traditions,” says Dr. Benton, who is white and has been a member since 2000. At Fellowship church, they needn’t give those up in order to belong. “Most don’t come from a tradition with this much flexibility,” she adds.

“I was allowed into the circle,” says Jojo Gabuya, a Filipino whose roots were in Catholicism. Jojo Gabuya, who has been part of Fellowship church since 2017, is also a member of the United Church of Christ. Since its earliest days, Fellowship church has pioneered dual and long-distance memberships to honor spiritual heritages and allow those outside the area to participate.

“Fellowship church looks for what we have in common,” says Jojo Gabuya, who works for Wesley Foundation Merced, which is affiliated with the United Methodist Church of Merced. “It’s a boundary crosser. ... You can go outside the fence and make relationships with people who don’t belong to your religious interest.”

Fellowship with all

Fellowship church has an impressive legacy among religious icons. Dr. Thurman’s mentoring of civil rights leaders strengthened the spiritual foundation of Martin Luther King Jr., a Baptist minister, among others.

People talk about Dr. Thurman not being involved in the civil rights movement, but that’s not true,” says Dr. Blake, who is Black. “The church’s existence was a statement for civil rights and challenged society’s racial and religious norms.”

More recently, church leaders and members have participated in marches for prison reform and collaborated with organizations and individuals on issues of social and environmental justice and ethics in technology.

“We are not at every protest march, but we offer spiritual refreshment and perspective to those who are,” says Dr. Blake.

While multiracial congregations are no longer an anomaly, embracing diverse racial and religious affiliations and beliefs in the sanctuary is not the experience of most American churchgoers. For Fellowship church, that is its mainstay and the reason many traditional denominations question whether it falls inside their definition of a Christian church.

The church’s declaration statement, which members agree to, places Fellowship church squarely in the Christian tradition, yet “Dr. Thurman … made a distinction between Christianity and what he called the religion of Jesus,” explains Dr. Blake.

Few traditional Christian denominations would express their faith in the way Fellowship church does with words like these from Dr. Thurman: “Experiences of unity between people are more compelling than all the prejudices that divide us[,] and if we can multiply these experiences over a long enough period of time, we can undermine and destroy any barrier that separates us from each other.”

For Fellowship church, that includes undermining and destroying the barriers of creed, denomination, or even the need for a shared understanding of God. In their place is unity – with one another and with God.

“The genius of Drs. Fisk and Thurman,” says Dr. Blake, “was that they moved forward because they could imagine church not as an end in itself, but as a pathway to helping us all to recognize our connection to the Divine and with each other.”

Listen

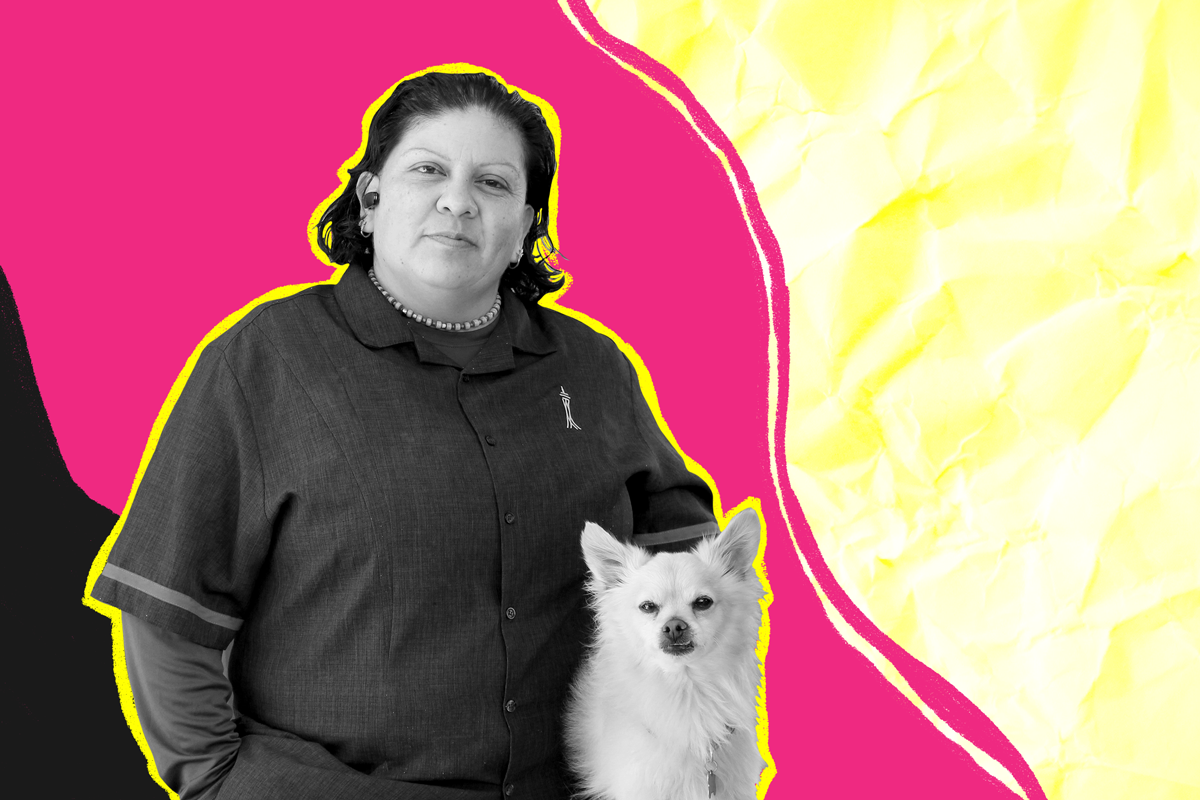

In year of tests, this hotel worker found community – and her voice

The pandemic had hotel service worker Mariza Rocha facing both joblessness and loneliness. Hear how she tapped the power of community support in Episode 4 of our podcast “Stronger.”

When Mariza Rocha lost her job as a utility porter at The STRAT Hotel here in March 2020, she turned to her union.

The Culinary Service Workers Union Local 226, part of the largest in Nevada, helped her get unemployment benefits and food assistance. In July, when Ms. Rocha was diagnosed with COVID-19 after going back to work, it fought to get compensation for workers like her.

And in the months that followed, Ms. Rocha became more active with the organization, volunteering regularly and even participating in political campaigning for the first time. The work helped her cope with her uncertain income – and created a sense of community during an incredibly difficult year.

Now Ms. Rocha is convinced she would never have survived the past year if it weren’t for the organization’s support. “It’s not that I put too much cream on the tacos about the union,” she says, “but … they were there for me all the time.”

In this episode of our podcast “Stronger,” we look at how a strong support network – no matter what form it takes – can make a difference during times of crisis. – Jessica Mendoza and Samantha Laine Perfas

This is Episode 4 of our podcast “Stronger,” which highlights what women have lost to this pandemic and how they’re winning it back. To learn more about the podcast and find other episodes, please visit our page.

This story was designed to be heard. We strongly encourage you to experience it with your ears (audio player below), but we understand that is not an option for everybody. A transcript is available here.

The Service Worker

New generation of cooks lifts lid on India’s diverse cuisine

Too often, “Indian food” is portrayed as one cuisine. Recent cookbooks chip away at this misperception, transmitting wisdom and nuance traditionally passed down in the kitchen.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Charukesi Ramadurai Correspondent

Indian food is as diverse as India itself. But at some point in the late 1980s, it began being represented both globally and nationally as one homogeneous mass, full of curries and chicken tikka masala – a dish most Indians have never heard of. Regional cuisines began to be relegated to the kitchens of more discerning home chefs, or were carried abroad by Indian students dreaming of their mother’s culinary creations.

Today, that’s changing. Regional Indian cuisine is being rediscovered and celebrated once again through trendy pop-up brunches and specialty restaurants. And a growing number of regional cookbook writers are publishing recipe collections that echo those of decades past, when modern life began to displace multiple generations of women sharing the kitchen and dispensing wisdom.

“We have begun looking inwards rather than taking our cues from the West on what to eat,” says food writer Rushina Munshaw Ghildiyal, referring to the recent Indian craze for kale and quinoa. “Now many of us are interested again in local ingredients, and are curious about how other people in our country eat.”

And like their predecessors, these books offer glimpses of hidden cultures – culinary and otherwise – to a larger audience.

New generation of cooks lifts lid on India’s diverse cuisine

When I got married a couple of decades ago in the south Indian city of Chennai, my aunt gave me a cookbook on traditional vegetarian Tamil cooking. “Samaithu Paar” (“Cook and See”) by Meenakshi Ammal, first published in 1951, was still considered a go-to guide for any young Indian bride. I found myself often opening the book to rustle up simple meals, including staple stews like lentil-based sambar and the tangy-spicy rasam.

“Cook and See” is just one of several community cookbooks from the decades when modern life began to displace multiple generations of women sharing the kitchen and dispensing wisdom as they prepared family meals. Through these books, the authors offered glimpses into their lives. For example, “Time & Talents Club Recipe Book” (1935) – packed with 2,000 recipes by a variety of contributors, sold as a fundraiser, and republished six times – is still held as the beacon for Parsi cooking, a meat-rich cuisine shaped by influences from Persia, where the community comes from, and from Gujarat, the Indian state they first called home in India. “Rasachandrika” (1943) by Ambabai Samsi featured recipes from the Saraswat Brahmin community on the western Konkan coast.

These cookbooks by homemakers for homemakers were compilations of not only recipes but also practical information – from essential cooking to festival rituals and home remedies for common ailments. Each community in India had, and still has, its own unique ingredients, techniques, recipes, and eating rituals, and these collections ensured this knowledge was passed down through the generations.

Somewhere in the late 1980s, however, Indian cuisine began to be seen and represented globally and nationally as one homogeneous curried red mass. Perhaps it was because the flavors of garlic naan and chicken tikka masala (a dish most Indians have never heard of) traveled well across continents and palates, or perhaps because the Punjabi people successfully managed to showcase their cuisine wherever they went. But the result was that representations of Indian food were cleaved into two neat south and north divisions as far as restaurant cooking was concerned. Regional cuisines and their cookbooks began to be relegated to the kitchens of more discerning home chefs or they were carried abroad by Indian students dreaming of their mother’s culinary creations.

But regional Indian cuisine is being rediscovered and celebrated once again through trendy pop-up brunches and specialty restaurants. More important, a growing number of regional cookbook writers are publishing new cookbooks, complete with easy but largely unknown recipes and glossy photographs highlighting regional spices, legumes, millets, oils, and grains.

“We have begun looking inwards rather than taking our cues from the West on what to eat,” says food writer Rushina Munshaw Ghildiyal, referring to the recent Indian craze for kale and quinoa. “Now many of us are interested again in local ingredients, and are curious about how other people in our country eat.” And like their predecessors, these books offer glimpses of hidden cultures – culinary and otherwise – to a larger audience.

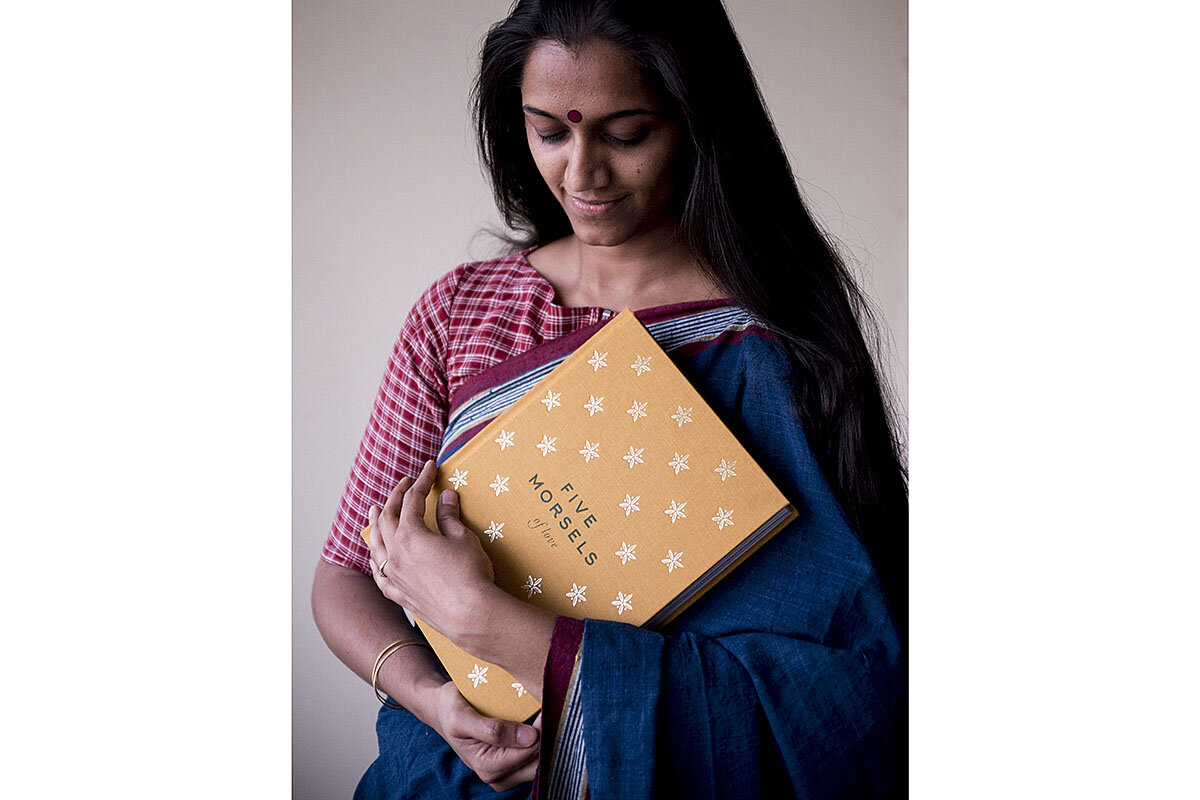

Take for instance, Lathika George’s book “The Suriani Kitchen” (2009). It is a rich repository of recipes from the small community of Syrian Christians in Kerala, whose cuisine is known for its extensive use of meat and seafood as well as coconut and local spices such as black pepper. It also serves as a cultural explainer – from typical community Christmas rituals to unique utensils, such as mann chatti (mud pots). Similarly, “Five Morsels of Love” by Archana Pidathala (2016) is a compilation of heirloom recipes from the southern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, known for its extensive use of fiery, red chili, and the plethora of dry chutneys and spice powders. The more recent “Pangat, a Feast: Food and Lore from Marathi Kitchens” (2019) by Saee Koranne-Khandekar documents the versatility of cuisine from the various communities within the state of Maharashtra.

These newer cookbooks are odes to the older women of the community who ran their homes and kitchens with smiling efficiency, and innovated quietly with what was at hand, using up vegetable peels and leftover rice with ease. Ms. Pidathala says that her self-published cookbook, which includes translations from her grandmother Nirmala Reddy’s cookbook published in Telugu in 1974, was meant more as a loving tribute, and confesses to being surprised at its popularity among Indians everywhere. “Cuisine in India changes every few miles, and I guess we are now more inquisitive about what everyone else is eating,” she says.

In the past, such cookbooks were usually produced by and for elites (Brahmins and Parsis, for instance), but now marginalized voices are being heard. One good example is “Isn’t This Plate Indian? Dalit Histories and Memories of Food,” published in 2009 by the Krantijyoti Savitribai Phule Women’s Studies Center in Pune. It spotlights Dalit cuisine shaped by lack of access to expensive produce and the need to make do, giving rise to dishes such as rakti – goat blood cooked with onions and chiles.

A few other such books are “The East Indian Kitchen” by Michael Swamy (2011), on the cuisine of early Christian converts in and around the islands that are now Mumbai; “The Seven Sisters: Kitchen Tales from the North East” (2014), about food from a region little known to the rest of India, by Purabi Shridhar and Sanghita Singh; and “The Pondicherry Kitchen” (2012) by Lourdes Tirouvanziam-Louis, which explores the influence of French, British, and Portuguese colonizers on local Tamil flavors.

Ms. Munshaw Ghildiyal says these books act as windows to the past that the present generation is trying to peek into. I can vouch for this, given that soon after I received the first volume of “Samaithu Paar,” I bought the next two. All these years later, and now halfway around the globe from home and family, these guides from generations ago remain my most-trusted resources for festive cooking and casual brunches alike. My cooking has progressed, too, graduating from the simple stews of 20 years ago to payasam (milk pudding) and vadai (fritters) for Diwali.

Takkili pandu pachchadi

Slow-cooked tomato chutney

“While we use tomatoes extensively in our everyday cooking, this simple chutney focuses wholly on the wonderful flavour of organic tomatoes. Chunks of red, juicy tomatoes are slow cooked, intensifying their robust flavour after which they are seasoned with freshly made fenugreek powder and generous amounts of garlic. My mother would always pack a box of perugannamu (curd rice) and this stunning red relish for our mid-morning school snack during the blistering summer months.”

– Excerpted from “Five Morsels of Love” by Archana Pidathala

Editor’s note: Many of these ingredients – such as the grams, which are a kind of lentil – can be found at Indian food specialty stores or natural food stores. “Tempering” is a cooking technique that briefly pan-roasts spices to enhance their flavors.

Makes a little more than 1 cup

1/2 teaspoon fenugreek seeds

4 tablespoons vegetable oil

6-7 red, juicy tomatoes, quartered

1/4 teaspoon turmeric powder

Salt, to taste

1 teaspoon red chili powder

Tempering

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

1/2 teaspoon mustard seeds

1/2 teaspoon de-husked, split black gram

1/2 teaspoon de-husked, split Bengal gram

1/2 teaspoon cumin seeds

2 dried red chiles, broken in half

8-10 fresh curry leaves

10 garlic cloves, peeled

1-2 teaspoons jaggery or powdered sugar (optional)

Dry roast the fenugreek seeds in a small pan over medium heat till they turn a shade darker. Cool completely and pound to a fine powder in a mortar and pestle.

Heat 4 tablespoons of oil in a heavy-bottomed pan over high heat and add the tomatoes. Reduce the heat to medium and sauté for 1-2 minutes. Add the turmeric powder and salt; mix well. Cover and cook the tomatoes for 10-15 minutes, stirring occasionally. Now add the freshly ground fenugreek powder and red chili powder and cook for 1-2 minutes more. Turn off the heat.

To temper the spices, heat the oil in a heavy-bottomed pan over high heat until very hot. Add the mustard seeds. When they splutter, add the rest of the tempering ingredients in quick succession. Fry for about 20 seconds; add the tomatoes and cook on medium heat for 1-2 minutes. Taste the chutney; if you find it too tart, add the jaggery or powdered sugar and mix well. Serve with rice or any flat bread.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The other flood in Germany – generous volunteers

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Just before floods hit Northern Europe last week, a global survey announced that volunteering during the pandemic “remained relatively unaffected.” Nearly a fifth of adults worldwide were able to donate time to serve a community. A good example of this was the spontaneous outpouring of Germans to those in need of rescue and recovery in the flood zones.

“The civic engagement is extreme,” said one helper in a makeshift shelter for newly homeless people. For those who rushed to the devastated sites from all parts of Germany, the destruction was humbling. Many who offered boats, mops, generators, shovels, and other items had to be turned away – even before government workers showed up.

A country’s civic health can be measured by how many of its citizens volunteer for the public good. Responses to tragedies like those in Germany are a strong indicator of social affection and trust. “We’re seeing a lot of gratefulness and cooperation,” tweeted the fire department in Wuppertal on Friday as the floods hit. Given the generous response to this disaster, Germany has shown that even a pandemic cannot deter those compelled to give to others in need.

The other flood in Germany – generous volunteers

Just before record-breaking rains and catastrophic floods hit parts of Northern Europe last week, a global survey announced that volunteering during the pandemic “remained relatively unaffected.” According to the World Giving Index, nearly a fifth of adults worldwide were able to donate time to serve a community, with many seeing generosity as an antidote to fears of COVID-19. A good example of this was the spontaneous outpouring of Germans to those in need of rescue and recovery in the flood zones.

“The civic engagement is extreme,” said one helper in a makeshift shelter for newly homeless people in Bad Neuenahr-Ahrweiler. Local businesses, especially hotels, also joined the effort. The use of Facebook and other social media accelerated the response, which included online campaigns for donations.

For those who rushed to the devastated sites from all parts of Germany, the destruction was humbling. Many who offered boats, mops, generators, shovels and other items had to be turned away – even before government workers showed up.

Despite Germany’s reputation as a social welfare state, its global ranking in volunteering remains relatively high. “Everyone has to take responsibility in a democratic system and cannot leave everything to the state,” Katarina Peranić, head of the German Foundation for Commitment and Volunteering, told Finance Publishing last year. “Helping and supporting one another – that is the basis for social cohesion. Often you know much better yourself where grievances are locally and how they can be remedied.”

The last time Germany saw such a wellspring of civic giving was during an influx of more than a million refugees from the Middle East in 2015. About 14% of citizens ages 16 and older provided assistance to the refugees. The unprecedented surge in empathy led to a national reflection on the country’s “welcoming culture.”

In the past two decades, Germany has doubled its number of charity foundations. Last year, Berlin was given the honor of being the “European Capital of Volunteering” for 2021 by the European Volunteer Center in Brussels. Almost 1 in 3 Berliners volunteer in civic groups. Also last year the federal government set up the foundation on volunteering led by Ms. Peranić to promote volunteering in rural areas, where most Germans live.

A country’s civic health can be measured by how many of its citizens volunteer for the public good. Responses to tragedies like those in Germany are a strong indicator of social affection and trust. “We’re seeing a lot of gratefulness and cooperation,” tweeted the fire department in Wuppertal on Friday as the floods hit. Given the generous response to this disaster, Germany has shown that even a pandemic cannot deter those compelled to give to others in need.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Comfort, strength, and reconciliation

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Lyle Young

Recognizing everyone’s nature as God’s child offers a powerful basis for learning from mistakes, loving our neighbors of all backgrounds more freely, and moving forward together.

Comfort, strength, and reconciliation

The recent discoveries in Canada of hundreds of unmarked graves of children has left the country gasping for air. The graves are all in close proximity to former residential state-sponsored religious schools whose purpose was to assimilate First Nations children into Euro-Canadian culture. These discoveries have shocked most Canadians and confirmed what many First Nations people have spoken of for years. (See, for instance, “An Indigenous children’s grave unearths Canada’s grim history,” CSMonitor.com, June 4, 2021.)

How does a country that in so many ways celebrates diversity find the courage and honesty to face such a dark part of its history, a history that continues to have a marked effect on survivors and later generations today?

According to Perry Bellegarde, former national chief of the Assembly of First Nations, the country is progressing relative to reconciliation. And though First Nations stories are often heart-aching, many of those stories are being told with a spirit of joy and even humor, which has helped me and others feel our shared humanity and renew our empathy for each other.

While accurate history-telling is important to healing, my study and practice of Christian Science has helped me see that there are certain truths that exist beyond human history, which are invaluable to reconciliation. Jesus pointed to an underlying eternalness to existence when he said, “Before Abraham was, I am” (John 8:58). This statement certainly indicates the timeless nature of the Christ, the true idea of God, which Jesus brought to light through his unique life. It can also be understood as a profound statement about the identity of all of us as God’s children, which Jesus proved in his many healings. From this perspective we can begin to grasp that each of us has always coexisted with our common Father-Mother God and with each other: before the founding of Quebec City by Samuel de Champlain in 1608; before Jacques Cartier arrived in the 1500s and started calling what would become Canada by that name; even before Vikings came to what several indigenous groups call Turtle Island (North America).

“Before” in Jesus’ statement can be understood to mean not chronologically, but metaphysically, spiritually. Beyond the reach of human history itself, each of us exists, has existed, and always will exist as the spiritual offspring of our heavenly Father-Mother, who is infinite Love – in peace and harmony with each other.

This was the reality of identity that Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, found in the Scriptures – that fundamentally, everyone’s identity is purely spiritual and free as the expression of eternal Love. She wrote, “Entirely separate from the belief and dream of material living, is the Life divine, revealing spiritual understanding and the consciousness of man’s dominion over the whole earth” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 14).

Acknowledging this truth of our pure spirituality, and being conscious of the God-given dominion that the Bible attributes to one and all as God’s children, doesn’t mean ignoring human history. But it does provide a strong basis for not being controlled by that history. As children of God, Love, we’re all capable of expressing the humility to learn from our individual and collective experiences, the discernment to cherish what is good in that history, the strength to find freedom from the mistakes and suffering of the past, and the ability to love our neighbors more freely.

Recently while walking downtown on a bright summer morning, I felt led to reach out to an older Inuit woman who seemed to be needing a bit of support (many Inuit come from northern Canada to my home city, Ottawa, to access health and educational services). In those brief moments, a feeling of brotherly love and affection filled my heart. I felt moved to say, with deep conviction, “God loves you and you are precious.” The woman grabbed my thumb, held it tightly, and said, “Thank you.”

In that simple exchange it felt to me that, beyond race and different life experiences, we were receiving a spiritual gift, glimpsing the higher reality of our shared existence in God. Though that moment was brief, the spirit of that divinely impelled love has lingered in my thought like a lilting melody, inspiring me. I doubt I’ll ever pass that spot again without thinking of that sweet experience.

Truly, brotherly, sisterly love is the only way to bring about lasting reconciliation and equality. Only love gives us the strength to change ourselves, which ripples out in the way we relate to others and can even impact policies and institutions. Happily, our true nature as spiritual brothers and sisters – each of us cradled eternally in the universal family of God – gives us the power to express that love with increasing consistency.

A message of love

Riding low in his driver’s seat

A look ahead

Thanks for starting another week with us. Come back tomorrow to learn about a New York company that teaches adults – many of them women and immigrants – to overcome fear and embarrassment and learn to ride bikes, to work or with their kids.