- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The utility of beauty

April Austin

April Austin

Sometimes an old building is worth preserving for its own sake, because it is beautiful, not just for the history it represents.

For years, I would walk past the former Coca-Cola bottling plant in downtown Indianapolis and admire its streamlined 1920s art deco design. I would touch the cream-colored tile that covered the exterior of the building and whisper a prayer that someone would see its beauty and restore it, rather than tear it down, as so often happens.

On a recent visit to my hometown, I made a pilgrimage to the new Bottleworks District, a mixed-use $260 million redevelopment of that old soft drink factory. The buildings have been lovingly and thoughtfully restored to pristine condition. The tile sparkles, the doors gleam. Inside, the reclaimed lobby now serves luxury hotel guests instead of soft drink executives. It boasts floor-to-ceiling mosaics along with grillwork in the shape of a flowing fountain – a nod to the effervescence of the carbonated drink.

Few companies today would go to the trouble to create a total work of art, from bottom to top, for a mere factory complex, the way the original owners of the Coca-Cola plant did. By doing so, they made a statement about artistry, elegance, and the utility of beauty.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Cities grapple with homelessness, as tent clusters proliferate

The pandemic drove more homeless people into tents, and emergency public health measures allowed many to remain undisturbed. Now, localities are trying to find better housing and care solutions.

The workers gather in a Venice Beach parking lot, then set out in small teams, backpacks filled with sandwiches, fruit, and bottled water. Their goal: to peacefully clear an encampment of homeless people by convincing them, over the course of many weeks, to leave their tents for more substantial housing.

It’s an exercise in patience, as cities all around the country grapple with homeless encampments, which have grown in size and number. The COVID-19 pandemic forced shelters to reduce occupancy, and while thousands of unhoused people were moved into hotels and motels, many others were simply displaced. To prevent viral spread, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended against breaking up the tent clusters.

Now, the increasing visibility of the tents has put growing pressure on local politicians to “do something.” But the complexities of helping people with different needs and conditions are visible right here on the beach.

Rob Nelson, who lost his house and came to Venice about 18 months ago, was raking the sand around his “office” – a tarp-covered structure. He said he had no intention of accepting services or an alternative place to live. “I need to be an outdoor person at the moment.”

Cities grapple with homelessness, as tent clusters proliferate

It is nearly noon, and a Los Angeles sanitation crew is wrapping up dismantling the home of Jack Rivers.

A yellow-vested worker rakes the narrow strip of dirt where the veteran’s tarp-covered dwelling once stood – part of a highly controversial homeless encampment of about 200 people jammed along the iconic boardwalk at Venice Beach.

All morning, Mr. Rivers has been sorting his mounds of belongings, his head wrapped in a T-shirt to protect him from the sun. With a small crowd looking on, he flings a sweatshirt, pants, rolls of toilet paper, and a flurry of blue face masks toward a shopping cart. He rolls a round tabletop out of his way and heaves a bicycle frame.

The sanitation workers have already tossed carpets, a nylon awning, and boards into the maw of a nearby garbage truck. They use grabbers to pick up hazardous waste such as needles. From time to time, a mouse or rat makes a quick getaway as items are moved.

This is a voluntary clearing – an exercise in patience that some describe as a more humane approach than a one-time sweep by law enforcement.

Clearing the entire encampment was slated to be done over six weeks, finishing by the end of July. It has taken hours to tackle just this one site, as outreach workers allow Mr. Rivers to decide which of his possessions to keep for up to 90 days in storage. And it has taken months of visits to persuade the native Angeleno, who cited his battles with illness and substance abuse, to move to temporary housing under Project Roomkey, a state and local effort to secure hotel and motel rooms for homeless people during the pandemic.

“I feel very blessed to be there,” he says of his room at the Cadillac Hotel, a pink oceanfront property just half a block down the boardwalk.

There’s no hard data, but experts and advocates agree that encampments like this one have grown in size and number in cities across the United States. The COVID-19 pandemic forced shelters to reduce occupancy, and while thousands of unhoused people were moved into hotels and motels, many others lost homes and were simply displaced.

To prevent viral spread, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended against breaking up the tent clusters. The pandemic also exacerbated mental health and drug and alcohol issues, while treatment stopped.

The growth of urban encampments has led to clashes over the use of public spaces like parks and sidewalks. In Washington, D.C., where tents have mushroomed over the last 18 months, controversy erupted over a plan to replace a minicamp at trendy Dupont Circle with cafe tables and chairs. The city decided to do a cleaning, not a clearing.

In Seattle, where the city all but halted tent removals during the pandemic, the number of tents has increased by more than 50% in its urban core since before the pandemic, and greatly expanded in areas where they’d previously had little presence. Several jurors have refused to serve in the county superior court because of violence, including a fatal stabbing, at the encampment next door in City Hall Park. A county councilman is trying to force a change in jurisdiction of the park in order to relocate tent dwellers to transitional or permanent housing.

Pressure is ramping up on local politicians to “do something,” while raising questions about the best approach. A first-of-its-kind study of encampments, published in January 2020, found that cities have a “weak knowledge base” of what to do about this issue.

Researchers looked at four cities – Chicago; Houston; San Jose, California; and Tacoma, Washington – and found that they coalesced around a general strategy of “clearance and closure with support.”

It’s an approach that appears to be gaining ground – but it’s expensive, with the cost per homeless person ranging from $1,672 in San Jose to $6,208 in Tacoma, the greatest cost being for outreach. None of the cities has the ability to shelter its entire homeless population, and a common problem with clearing encampments is that it can end up simply reshuffling people and tents and re-traumatizing those being moved.

In California, a growing problem

There are now more homeless people living outdoors in America than sheltered, and no state has more than California, which counts 113,660 people, or 70% of its homeless population, as unsheltered. The Golden State has struggled for years with homelessness, but the explosion in tent communities during the pandemic is forcing cities here to try different approaches.

San Francisco created “safe sleeping villages” during the pandemic, providing security, meals, running water, and trash pickup for tent communities – which cost the city $5,000 per camper per month. Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg is proposing a “right to housing” mandate that would force his city to provide choices of housing or shelter beds for homeless people, which they must take or face an undetermined civil penalty.

This month, the Los Angeles City Council voted overwhelmingly to enact rules prohibiting sitting, sleeping, or storing belongings near homeless shelters, schools, parks, and other types of public areas, or the person must pay a fine – which some consider an unfair punishment that most homeless people would be unable to pay anyway. It’s unclear how such an ordinance squares with a 2018 appeals court ruling, upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court, which struck down anti-camping laws as cruel and unusual punishment if shelter is not available.

Still, unquestionably the pressure is rising on politicians. California Gov. Gavin Newsom is facing a recall election in September in which homelessness is a major complaint. And here on Ocean Front Walk in Venice, where a man was killed in a tent last month and where drug and alcohol abuse is rampant, a petition drive is underway to recall a city councilmember, Mike Bonin, over homelessness and crime.

Notably, neighboring Santa Monica, which enforces its regulations about no overnighting on the beach, has no beach encampments.

“We have a real state of emergency here,” says Kayde McMullen, manager of the Venice Ale House. Tourism is down and repeat customers are staying away, says Mr. McMullen, who is harshly critical of Councilmember Bonin. The manager tells of one person who ran into the Ale House bathroom, locked the door, and started screaming; another was found shooting up in the bathroom. While Venice had homelessness before COVID-19, “the pandemic blew the cap off,” he says from behind a wooden counter.

In June, Mr. Bonin – himself once homeless – announced in a letter to constituents an “unprecedented” six-week program to “humanely” address the encampment crisis and offer interim housing and support services leading to permanent housing. It is a coordinated effort between neighbors, government agencies, and nonprofits, but – he pointedly said – “the effort will not be led by law enforcement, nor driven by threats of arrest or incarceration.” Law enforcement, however, has been involved in the clearing, mostly standing guard, but also rousting beach sleepers in the middle of the night.

In March, LA police cleared a large encampment at Echo Park Lake that turned into a confrontation as law enforcement arrested scores of people over two nights of protests. Most of the homeless people living there received interim housing, and most are still in it. The city restored the park’s lawns and facilities, and now it is surrounded by a temporary chain-link fence. Families tour the lake in swan paddle boats, while private security personnel regularly patrol in golf carts.

The importance of outreach

Fundamental to the clearing in Venice are outreach workers coordinated by the nonprofit St. Joseph Center and the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority, which last month put out a “best practices” guide for dealing with street encampments. At the top of the list are allowing ample time to engage with homeless people and helping them voluntarily accept care.

The workers gather for morning briefings in a beach parking lot, then set out in small teams, clipboards in hand and backpacks filled with sandwiches, fruit, and bottled water. They approach tent dwellers far in advance of the clearing start date, and talk with them multiple times – asking what kind of housing they might accept, what income they might have, what services they need. Some of the workers have experienced trauma themselves, and can relate as peers.

“People are recognizing it does take time to build trust. That’s very positive,” says Gary Painter, director of the Homelessness Policy Research Institute at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles.

Monica Peterson, an outreach worker with St. Joseph, says workers “hit the pavement as early as 7 and we end when we end.” They are now experimenting with late-night outreach. She recalls a case that took more than a year of repeated engagement – a woman who had set up on Venice Beach, selling her art as a vendor. She didn’t want to leave until just recently, and finally accepted a Project Roomkey placement, also at the Cadillac Hotel.

“It really does take time for people who have had repeated disappointments, trauma, and losses,” explains Dr. Va Lecia Adams Kellum, president of St. Joseph. Outreach workers keep approaching unhoused people, she says, “because you never know when that moment is going to be where they go, ‘You know what, I think I do deserve to live a better life. I think I do deserve something better than this.’ And we’d want to be the ones to deliver on that.”

As of July 19, the workers brought 131 people from the Venice encampment into interim housing – more than halfway to their goal. They have connected more than 40 of them with permanent housing.

More resources, not enough housing

A big difference is that these workers currently have more resources to offer – federal reimbursement for Project Roomkey, and more federal rental voucher assistance and other help passed by Congress this year. Matthew Doherty, a former homelessness official with the Obama administration, calls it the greatest scale-up of federal support he’s ever seen addressing homelessness, though he adds that communities are “struggling to move those resources as quickly as they can.”

He also points to California’s budget surplus and the $12 billion slotted for homelessness, prevention, and affordable housing. “I’m really optimistic about the scale of resources in that budget.”

But Venice Beach is just one encampment in a city and county full of them. While more than 65,000 people have been brought into housing in the last several years, there still is not enough affordable housing. And the complexities of housing people with different histories and needs and conditions are visible right on the beach, where some experts estimate that 40% to 60% of homeless people are “service resistant.” Many just want the beach lifestyle.

One of them is Rob Nelson, who lost his house in Mount Shasta in the northern part of the state and came down to Venice about 18 months ago to escape the snow. On the day the clearing effort started, he was raking his little patch of sand on the northern end of the encampment, cleaning up around what he termed his “office” – a tarp-covered structure. He said he had no intention of accepting any offer for housing or services. He loves it on the beach. “I need to be an outdoor person at the moment.”

Two weeks later, he was still there, having whittled his things down to a suitcase, a backpack, and a sleeping pad. The outreach workers had been by many times – “yap, yap, yap.” He said he planned to head south to Ocean Beach in San Diego, but still had a few bulky items he was trying to get rid of.

“Do you have need of a five-gallon propane can?”

By yesterday, the area where Mr. Nelson slept was cleared. There was no sign of him, or his propane tank. Just people zipping along on bikes and skateboards, and a little bit beyond, about a dozen tents newly scattered over the bright, wide stretch of sand.

Staff writer Ann Scott Tyson contributed to this report.

A deeper look

First Flint, then Jackson. Is America ready to fix its water supply?

Yes, a winter storm this February was unusually severe for Mississippi. But the failure of the water system in the state’s capital city revealed larger challenges – with what you could call the basic plumbing of society. First in a series on water and justice.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Xander Peters Special correspondent

-

Stephanie Hanes Staff writer

This winter a deep freeze left 43,000 households in Jackson, Mississippi, without drinkable tap water for weeks. Beyond the severity of the storm, it signaled the depth of the city’s backlog in water-system investment and maintenance.

Jackson’s situation is extreme but far from unique. Across the country, American water systems are crumbling. Decades of disinvestment and neglect, experts say, have left this infrastructure in some cases violating federal standards – or vulnerable to shocks such as February’s freeze. Gaps in access and maintenance are straining a basic social contract in one of the world’s richest nations: namely, that when one turns on the faucet, clean water comes out.

Citizens and policymakers alike are increasingly focused on how to address the challenges. As Jackson’s experience shows, the issue is not just water but justice: inequities along lines of race and class that can deepen when a city’s tax base erodes.

“Nobody figured out how to maintain the system in the long run,” says Mukesh Kumar, an urban planning expert at Jackson State University. “When water systems start breaking down, that’s when you start losing the most important part – trust.”

First Flint, then Jackson. Is America ready to fix its water supply?

When an unusually severe freeze struck the Gulf Coast region in February, blanketing everything from Central Texas to Alabama in a coat of ice, the city of Jackson caught national attention, at least briefly.

Both water treatment plants in Mississippi’s capital city were hobbled by the frigid temperatures. Water pressure sagged, compromising drinkability. Jackson’s nearly 43,000 water customers were placed under alert to boil anything that came from their faucets before drinking it.

The crisis dragged into days, then weeks. It was only on March 17 – a month after it began – that the boil advisory lifted for most residents in this majority-Black city.

But if the situation shocked many, Felicia Brisco wasn’t surprised. Owner of a hair salon in the city, she has seen years of challenges – from water main breaks during a 2018 winter storm to boil-water advisories affecting pockets of the city as recently as June. The effects have trickled down from Ms. Brisco’s kitchen to her shampoo-reliant work.

“We have had to turn clients away for weeks at a time due to issues with the water here in Jackson,” she says. “It can be very discouraging for businesses that need water to operate.”

Jackson’s situation is extreme but far from unique. Across the country, American water systems are crumbling. Decades of disinvestment and neglect, experts say, have left this infrastructure in some cases violating federal standards – or vulnerable to shocks such as February’s freeze. And while crises such as the 2014 lead contamination in Flint, Michigan, bring periodic attention to the problem, long-standing gaps in safety, access, and maintenance are straining a basic social contract in one of the world’s richest nations: namely, that when one turns on the faucet, clean water comes out.

“Nobody figured out how to maintain the system in the long run. ... That’s what you’re seeing not only in Jackson, but in many cities across the country,” says Mukesh Kumar, an urban planning expert at Jackson State University. “When water systems start breaking down, that’s when you start losing the most important part – trust.”

But that, advocates say, is just what has been happening. While the disrepair is far from universal, it’s visible in communities big and small, rural and urban, coastal and landlocked. Problems with lead or other contamination are significant in major cities from Chicago and Cleveland to Baltimore and Newark in New Jersey.

It is no coincidence, advocates say, that those locations, like Jackson, are home to majority-Black and other nonwhite populations. Drinking water systems that constantly violated federal safety standards were 40% more likely to occur in places with higher percentages of residents of color, according to a 2019 report from the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Meanwhile, the federal government has reduced its support dramatically – from providing 63% of all U.S. water infrastructure investment in 1977 to 9% in 2017. Experts say that shift, tracked by The Value of Water advocacy group, disproportionately affected lower-income communities that could not make up the difference.

A NAACP report from 2019 describes how the intersecting forces of housing segregation, poverty, and rising cost of water have left Black communities across the country with reduced access to clean drinking water. In this sense, the emergency is one not only of infrastructure but also of justice.

Yet in the face of all this, something hopeful is taking place – and a trend that’s being explored in this and other Monitor articles in a series on water and justice.

For years, advocates say, water infrastructure was an “out of sight, out of mind” problem, a looming crisis literally hidden underground. Now, from small towns and urban neighborhoods to the corridors of Capitol Hill, a growing group of neighbors, activists, local officials, and lawmakers are talking about water access, and are joining together to come up with solutions. Support in the U.S. Senate and House for $35 billion or more in spending on water infrastructure signals rising bipartisan national attention to the issue.

“People are waking up to this fundamental truth that in a country with as many financial and technological resources as we have ... it should be a basic human right that everyone has access to clean, safe drinking water,” says Maureo Fernández y Mora, the associate state director for Massachusetts for the advocacy group Clean Water Action. “That is not currently something that has been delivered upon for a number of communities across the United States, and that really does need to change.”

That’s what people such as Ms. Brisco are increasingly demanding in Jackson.

“We know it’s not going to happen overnight, because the failure didn’t happen overnight,” Ms. Brisco says of how she and other residents are calling for changes. But “clean water is a necessity that all citizens should have access to.”

“Without water or sewer, you don’t have a city”

The path toward answers involves grasping how the problems emerged in the first place. Funding shortfalls, not just federal but local, have played a key role. And behind that lies a story of demographic change. In 1960, Jackson’s population of 148,000 was roughly 64% white and 36% Black. But as in other metro areas nationwide, school integration led to white flight, and in later decades other factors including rising crime rates fueled a further exodus to the suburbs among Jackson’s white and Black middle class alike.

With them, too, went a large portion of a tax base that Mississippi’s largest city has historically depended upon. Today, roughly 1 in 4 of Jackson’s more than 166,000 residents earn below the federal poverty line. About 16% of the city’s population today is white; 82%, Black.

Mississippi state Rep. De’Keither Stamps says the infrastructure inequalities are drawn along income lines, even as the effects fall disproportionately on Black residents.

“Jackson’s been led by Black leadership for 30 years. This is a class issue more so than a race issue. This is a this-side-of-town versus that-side-of-town sort of issue,” says Representative Stamps, a former Jackson city councilman. “West and south Jackson have been disinvested when it comes to infrastructure for a long time.”

In March, Jackson Mayor Chokwe Lumumba, a Democrat, conservatively estimated that the city’s overall infrastructure upgrades could require up to $2 billion in funding – a massive tally for a city with an annual budget of about $300 million – with at least half of the upgrades destined for investment in the sewer system alone.

More than many cities, Jackson is a sprawling metro area with more than 1,500 miles of water mains running underneath its streets. It was also designed with a larger modern population in mind, yet its population has declined by about 20% since peaking at 200,000 in 1980, according to U.S. census data.

“At the heart of the problem is that lack of planning for operations and maintenance in the 1970s,” an era when cities were reaping federal grants from the 1972 Clean Water Act, says Dr. Kumar at Jackson State. “The way I see it right now is that without federal assistance, this is going to be a tall order. I don’t see how many American cities actually come out of this water crisis on top.”

Yet the imperative is clear. From the aqueducts of Rome to the canal and reservoir systems of Cambodia’s ancient Khmer civilization, public water systems have long been a foundation for societies to flourish.

“Community water systems cannot be allowed to collapse,” Dr. Kumar says. “Either you have to replace it, or otherwise, without water or sewer, you don’t have a city.”

Years of work ahead

Charles Williams, Jackson’s public works director, feels that pressure directly.

“My biggest fear during all this was that somebody was going to drive up to my office and basically say, ‘All right, you’re out, pack your bag – we’re going to take you to the outskirts of Jackson and leave you there,’” Dr. Williams says of his concern for eroding trust between community managers like himself and Jackson residents. “We understand the frustration.”

Dr. Williams speaks candidly of daunting work to come.

In all likelihood, Jackson is facing a 10- to 20-year project that will call for the replacement of old pipes and upgrading treatment plants. The city initially made a request to the state for $47 million for water and sewer upgrades. Mississippi lawmakers allocated $3 million, with the hope that federal dollars from President Joe Biden’s American Rescue Plan – more than $46 million of which is reserved for the city – will help in covering the difference.

In March, U.S. Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith, a Mississippi Republican, introduced a bill that would double the direct allocation to Jackson by authorizing the Army Corps of Engineers to spend $47 million for “environmental infrastructure projects.”

“The overall recovery of Jackson is going to take time,” Dr. Williams says. “This will go beyond my tenure here at the city, and the mayor’s.”

Meanwhile, the concept of maintaining patience with the city has begun to wear on some of its longtime residents, even as they push for action on water among other local issues.

Civil rights movement activist Euvester Simpson and her husband, Les Range, the former executive director of the Mississippi Department of Employment Security, understand the constraints facing current city leaders.

“I think the neglect occurred before the current leadership came into place,” Mr. Range says. “West Jackson, south Jackson, they experienced neglect. And then, as happens all over the place when African Americans take control, they inherit a mess. It’s hard to put resources together to fix it.”

Yet they find themselves questioning whether current city leaders are working effectively together – and earning public trust.

“I’m very much concerned about the direction that we’re going in, if we’re going to survive without the city just absolutely crumbling and falling apart,” Ms. Simpson says. “I don’t know what we’re going to do, but I know that I believe we need some new leadership.”

She adds, “We’re not going to give up on Jackson – yet.”

Stephanie Hanes reported for this article from Northampton, Massachusetts.

Editor's note: The comment by Maureo Fernández y Mora, associate state director for Massachusetts for the advocacy group Clean Water Action, has been clarified.

Patterns

Where slogans wear thin, citizens grow weary

Once, leaders like Fidel Castro and Nelson Mandela could command loyalty through their rhetoric. The unrest in Cuba and South Africa shows that their successors must offer more concrete sustenance.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

They were sudden eruptions of unrest, on a scale not seen for decades, on opposite sides of the world. But last week’s demonstrations and riots in Cuba and South Africa carried a similar message, and targeted regimes that share a pedigree as well.

Those regimes are the heirs of two iconic political figures: Fidel Castro and Nelson Mandela. And the message was that the old rhetorical flourishes and lofty promises have lost their resonance. Put more bluntly, slogans cannot feed us, nor house us, nor give us jobs and hope for the future.

It’s a message that could have implications elsewhere in the world, where other self-styled heirs of revolution or long-ruling leaders are already under pressure, such as Nicaragua’s veteran President Daniel Ortega in Latin America, and post-independence African leaders like Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni and King Mswati III in Eswatini, the former British protectorate of Swaziland.

Two key catalysts for the Cuban and South African turmoil were the economic shock waves from the pandemic and the widening influence of social media in knitting together young people. These factors aren’t unique to those countries and they aren’t likely to fade anytime soon.

Where slogans wear thin, citizens grow weary

They were sudden eruptions of unrest, on a scale not seen for decades, on opposite sides of the world. But last week’s events in Cuba and South Africa carried a similar message, and targeted regimes that share a pedigree as well.

Those regimes are the heirs of two iconic political figures: Fidel Castro and Nelson Mandela. And the message, amid festering economic hardships and growing inequalities, was that the old rhetorical flourishes and lofty promises have lost their resonance, especially among young people. Or put more bluntly: Slogans cannot feed us, nor house us, nor give us jobs and hope for the future.

And while the focus now will be on how the leaders of Cuba and South Africa respond, that message could have longer-term implications for other self-styled heirs of revolution or long-ruling leaders already under pressure elsewhere in the world, from Nicaragua’s veteran Sandinista leader Daniel Ortega in Latin America, to post-independence African leaders like Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni and King Mswati III in Eswatini, the former British protectorate of Swaziland.

That’s because two key catalysts for the Cuban and South African unrest aren’t unique to those countries and aren’t likely to fade anytime soon: the economic shock waves from the pandemic, and the widening influence of social media in knitting together young people, who are the worst affected.

Cuba and South Africa, of course, are different. Cuba is an authoritarian Communist state. South Africa is a democracy, with one of the most progressive constitutions in the world. Mr. Castro came to power in a revolution more than six decades ago. Mr. Mandela’s ascent to the presidency, and the final chapter of apartheid, occurred through a negotiated surrender by the country’s white-minority rulers.

Last week’s eruptions were different, too. In Cuba – to chants of “libertad” and “si, se puede,” an echo of Barack Obama’s “yes, we can!” – thousands poured onto the streets in a peaceful show of their accumulated frustrations over food shortages, job shortages, and electricity outages.

In South Africa, the language was violence, in what initially seemed an organized uprising by supporters of former President Jacob Zuma, imprisoned for contempt of court and facing corruption investigations. But it spiraled into break-ins and looting at shops and shopping malls, in a country where nearly half of young people are jobless.

Yet both countries are in effect one-party states: Mr. Mandela’s African National Congress (ANC) has been in power since the end of apartheid in 1994. And both regimes have anchored their rule, shaped their political lexicon, and staked their legitimacy largely on the reflected early triumphs of the now-departed Nelson Mandela and Fidel Castro.

The problem, suddenly thrust into the open, is that times have changed.

Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel – who succeeded Mr. Castro’s younger brother, Raul, two years ago – initially fell back on the old political playbook. He summoned supporters to take back the streets from “counter-revolutionaries” and “delinquents,” who he said were part of a U.S. plot. They duly turned out and, alongside police, assaulted, arrested, or dispersed the protesters.

Still, even the president seemed to acknowledge the economic grievances, saying it was “legitimate to feel dissatisfaction.” And a few days later, he made at least one small concession, meeting the demonstrators’ demand to waive duties on food and other necessities brought into the country by overseas visitors.

And he cannot have missed one signal, at least, of how the ruling party’s Castro-era hold on the islanders has been eroding.

The last such public demonstration came in 1994, when Cuba’s economy was suffering the aftereffects of the collapse of its key international ally, the Soviet Union, and thousands gathered along Havana’s famed Malecón coastal promenade. A visit by Mr. Castro himself to the waterfront helped calm the situation.

This time, President Díaz and senior aides rushed to San Antonio de los Baños, the town about 15 miles outside the capital where the first demonstration erupted – only to find that the protests had already spread to other towns and into Havana itself.

In South Africa, the violence amounted to an exclamation point to years of post-Mandela government marked more by power struggles inside the ANC – and, during Mr. Zuma’s nine years in power, by cronyism and corruption – than by a focus on the country’s problems.

President Cyril Ramaphosa’s reaction was forceful, denouncing what he called an attempted insurrection by Mr. Zuma’s supporters, who retain considerable influence inside the ANC, and vowing to bring the perpetrators to justice.

But the question now is what he’ll do next. Mr. Ramaphosa, a former union leader who was close to Mr. Mandela, took office three years ago pledging to clean up the ANC, reform government, and address the country’s economic and social problems.

So far, he has proved reluctant, or unable, to confront Mr. Zuma’s ANC supporters head-on.

Still, with signs that the most serious violence since the end of apartheid has shocked many South Africans, Mr. Ramaphosa may now feel he has a political window finally to make good on his promises and focus the government’s energy on the country’s problems.

Listen

The pandemic pushed her to the limit. But this teacher carries on.

Teaching has become a difficult relationship for Leslie Stevenson, made only tougher by the pandemic. Can she find a way to do what she feels called to do without burning out? Episode 5 of our podcast “Stronger.”

Leslie Stevenson thought it would be corny to follow in her mom’s footsteps and become a teacher. But one stint as a substitute was all it took for her to fall in love with the field.

“It felt like this is where I belong,” Ms. Stevenson says. “I get to see my fingerprints on [my students’] lives.”

But even pre-pandemic, teaching could be grueling. It often meant dealing with blurred boundaries, after-hours demands, and a lack of community support. The pivot to remote and hybrid learning only made things worse, for her and many others. Educators are facing burnout and disillusionment. And some, like Ms. Stevenson, are wondering whether or not to stay in the field – despite how much they love the job.

“In the past three years, particularly the last year, all the noise, the static, the extra stuff to prove my worth to people?” she says. “That is what’s making me question: What am I doing?” – Jessica Mendoza and Samantha Laine Perfas

This story was designed to be heard. We strongly encourage you to experience it with your ears (audio player below), but we understand that is not an option for everybody. A transcript is available here.

The Teacher

Difference-maker

How Book Dash nurtures South Africa’s young readers

How do children become readers? Simple as it sounds, they need books – lots of them, to explore and enjoy whenever they want. This nonprofit aims to turn that into a reality for every South African child.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

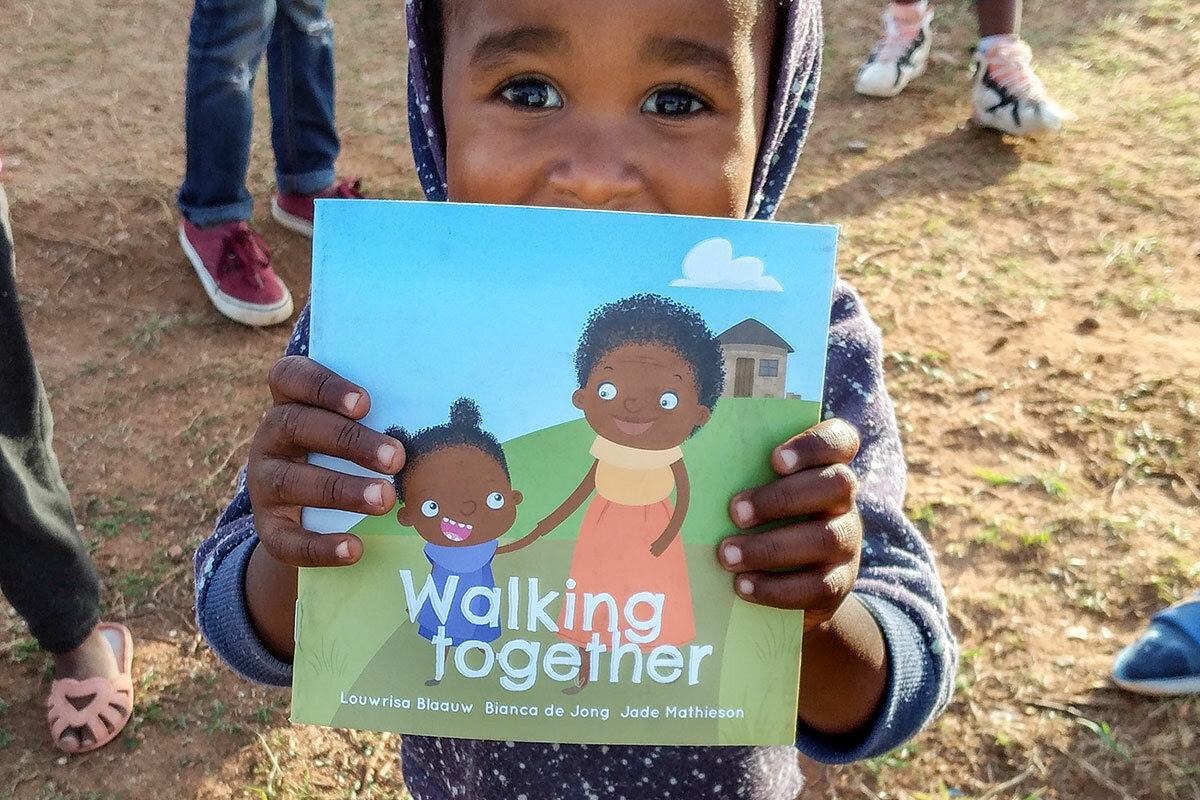

At Book Dash, a South African nonprofit organization, the answer to helping children become readers takes just 12 hours – a “dash” indeed. Volunteer writers, illustrators, and editors collaborate in a daylong creative marathon, pumping out children’s books that range from the quirky (a runaway pig, for example) to the profound: the circle of life, the importance of diversity.

It’s more than a creative challenge. It’s about social justice. Having a large collection of books at home has been shown to be a significant factor shaping children’s success at school. But in South Africa, where around 6 in 10 children live in poverty, many families are priced out of glossy picture books.

“We were devastated by the idea that having a book was a luxury good,” says director Dorette Louw.

Book Dash’s model leapfrogs many traditional costs of publishing, so it can distribute books to partnering literacy and education charities on a shoestring budget. PDFs are freely available on the website, and print copies sell for less than $3 each.

Janet Duma works at Thanda, an organization that distributes the books. “We have a library, but we noticed kids were often reluctant to give the books back,” she says. “Now anytime they want to read, they can grab a book from their shelf.”

How Book Dash nurtures South Africa’s young readers

When Thokozani Mkhize was growing up in South Africa in the 1990s, she devoured storybooks from all over the world. She read Chinese myths and Greek legends. There were Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales and “Goosebumps” novels.

The one thing she never read though were South African stories.

“At the time I wasn’t really thinking, why do none of these characters look like me?” she says. “But as I grew up, I realized there was a gap.”

So when a friend told Ms. Mkhize, a graphic designer, about a nonprofit organization called Book Dash, which recruits volunteers to write and design South African children’s books, she jumped at the chance to make things different for the generation after her.

Book Dash also intrigued Ms. Mkhize because of its unusual model – it challenged volunteer writers, illustrators, and editors like herself to create a full children’s book, in a single 12-hour “dash.” That allowed the organization to leapfrog most of the traditional costs of publishing and distribute more than a million copies of its books to households on a shoestring budget.

For Book Dash, like Ms. Mkhize, getting books into the hands of more South Africans has always been a question of social justice. Elsewhere in the world, having a large collection of books at home has been shown to be just as significant as the parents’ education level for determining how far a child will go in school, according to a 20-year study from the University of Nevada, Reno. Other studies have shown that having books at home correlates to not only better reading skills, but better math and technology know-how as well.

But nearly 60% of South Africans don’t have a single book at home, according to a 2016 survey by the South African Book Development Council, and 78% of fourth graders in the country can’t read for meaning – to understand a story or argument in a text – according to a global study conducted that year. Of the 50 countries surveyed in that study, South Africa finished last. And like most inequalities in the country, literacy levels are highly racialized, due in part to a long history of separate and unequal schooling that funneled resources into white schools and deliberately withheld them from Black ones. Eighty-seven percent of students who took the literacy test in Zulu – an indigenous language spoken mostly by Black South Africans – failed, for instance, compared with 57% who took it in English.

One primary reason so few households have books, says Book Dash Director Dorette Louw, is that they simply can’t afford them. Around 6 in 10 South African children live in poverty. And the fact that so many families are priced out of the glossy picture books on store shelves in turn drives the cost up more, because printing is more expensive in smaller quantities.

“We were devastated by the idea that having a book was a luxury good in South Africa,” Ms. Louw says of the organization’s founding.

Quick creativity

Book Dash’s model is deceptively simple. The organization, started in 2014, recruits professional writers, illustrators, designers, and editors to volunteer for daylong marathon book-creation sessions.

Using only a rough idea developed ahead of time by the writer, teams of four – a writer, editor, illustrator, and designer – meet and spend 12 hours honing the story, writing and editing the text, drawing the characters, and laying out the book.

“There’s a lot of camaraderie that develops, sitting around a table bouncing ideas and helping each other work,” Ms. Mkhize says. She’s participated in four “dashes” since 2015 – including two virtual events during the COVID-19 pandemic – as a designer, responsible for laying out the text and illustrations. Her favorite work, she says, is a brightly colored book called “Unathi and the Dirty, Smelly Beast,” about a girl and her adventures with her dog.

To date, Book Dash has produced more than 100 different books, sprawling across topics ranging from the quirky – a runaway pig, a sloth searching for the perfect spot to nap – to the profound – the circle of life, the value of diversity. Although the majority were originally written in English, many have also been translated into other South African languages. The country’s publishing is heavily dominated by titles in English and Afrikaans, which account for nearly 90% of all book sales here. That means few children have access to books in their first language, says Ms. Louw.

The organization then distributes its books through literacy organizations and other educational charities. It also makes the PDFs of all its books freely available on its website, and sells print copies via an online bookstore for 40 rand ($2.80) each.

In the rural community of Mtwalume on South Africa’s east coast, a community organization called Thanda has long distributed Book Dash books to children to help encourage them to read at home.

“We have a library, but we noticed kids were often reluctant to give the books back,” says Janet Duma, who works on Thanda’s literacy programs. “Now anytime they want to read, they can grab a book from their shelf. They have books accessible to them at all times.”

Reading at home

That mission became especially urgent in March of last year, when South Africa’s schools abruptly shut down as the country went into a coronavirus lockdown. As was the case in countries around the world, parents suddenly became teachers, often without any of the online support systems available to families in wealthier communities.

“Online learning isn’t an option if you don’t have a way to get online,” says Kirstin Nash, the head of marketing, communications, and partnerships at Thanda. So Thanda, which once ran after-school reading programs for local kids, began designing at-home activities like puzzles, art projects, and treasure hunts themed around Book Dash books, and sending Ms. Duma and her colleagues to show families how to use them.

When South Africa’s second wave of COVID-19 infections crested in January 2021, Mtwalume was especially hard hit, Ms. Duma says. That month, Thanda distributed a Book Dash book called “Circles,” about a mother and son vulture pair who watch an old antelope die, and the new circle of life that begins as nature reclaims his body.

“It’s not just our bodies we leave behind when we die,” the mother explains. “We also leave our lessons and our love and our memories.”

“It was a way to help kids talk about their grieving process,” Ms. Duma says. “And for families to have those conversations together too.”

For Ms. Mkhize, the designer, that’s exactly what she hopes her books will accomplish.

“You see yourself in these stories and these characters,” she says. “You can feel, ‘I am normal, my experiences are normal, and my stories are important too.’”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A deluge of giving after China’s floods

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For years, China ranked near the bottom on a global index of charitable giving and volunteering. But with its rise in wealth and in the number of Christians and Muslims – who perhaps now outnumber Communist Party members – the country’s standing on the giving index has rapidly risen. A good example is the surge of private help for those hurt by historic floods this week in Henan province – where a year’s worth of rain fell in just three days.

Nearly $300 million in donations has flowed into the region from Chinese enterprises, according to Reuters. Local people also sent out calls for assistance on WeChat and other social media. A similar outpouring of generosity occurred last year in the city of Wuhan, epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak, where party officials were slow to respond to the crisis.

Home to a fifth of the world’s population, China has steadily become a model for giving, or what Tibet’s exiled spiritual leader the Dalai Lama recently described as “thinking more of others than yourself.” The images of volunteers helping flood victims in Henan are showing the world a different China.

A deluge of giving after China’s floods

For years, China ranked near the bottom on a global index of charitable giving and volunteering. But with its rise in wealth and in the number of Christians and Muslims – who perhaps now outnumber Communist Party members – the country’s standing on the giving index has rapidly risen. A good example is the surge of private help for those hurt by historic floods this week in Henan province – where a year’s worth of rain fell in just three days.

Nearly $300 million in donations has flowed into the region from Chinese enterprises, according to Reuters. Big tech companies are some of the biggest donors. News aggregator Jinri Toutiao (“Today’s Headlines”) has allowed users in Henan to ask for help. Local people also sent out calls for assistance on WeChat and other social media. “Thanks to all the companies and individuals who remember the people of Henan. Chinese people are the most powerful when they are faced with a disaster,” said one Weibo user.

A similar outpouring of generosity occurred last year in the city of Wuhan, epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak, where party officials were slow to respond to the crisis. An estimated $5.9 billion was given to charity groups.

A big turning point for public magnanimity in China came after the 2008 earthquake in Sichuan. Thousands of volunteers rushed to the disaster scene, shocking party leaders who thought they had control over private charity. In 2016, a new “charity law” was passed to both encourage philanthropy but also tame it to follow party interests. Since then, the number of registered social organizations has more than doubled.

Also expanding are “giving circles,” or informal groups of private givers who pool their money for targeted charities. And since 2015, tech giant Tencent has sponsored a three-day online event called 99 Charity Day to raise money for giving groups.

Home to a fifth of the world’s population, China has steadily become a model for giving, or what Tibet’s exiled spiritual leader the Dalai Lama recently described as “thinking more of others than yourself.” The images of volunteers helping flood victims in Henan are showing the world a different China, one where the humanitarian response comes from the heart instead of a ruling party trying to stay in power.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Finding genuine connection

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Lisa Troseth

Unsure how to relate to a colleague of a different race, a woman prayed for inspiration. The realization that we are all created to reflect God’s love lifted her insecurity – and a heart-to-heart connection opened up between the two of them.

Finding genuine connection

Working with children in a community after-school reading program was a great experience. It was full of caring interactions with a wonderful diversity of participants and staff. But there’s one relationship in particular that stands out because of how we found a warm connection after a chilly start.

There was an individual whom I so respected for her years of dedication to this program. But early on there was a disconnect between us. We came from very different backgrounds, and I tended to feel insecure around her, not sure what to say or how to relate. We were also different races, and deep down I worried that the context of past and present race relations in our country would prevent us from genuinely connecting.

My way of handling this for a while was to keep a low profile and try to avoid crossing paths with her. But this didn’t feel right at all. Thankfully it finally occurred to me that this relationship deserved the most heartfelt prayer I could give it, to gain a more God’s-eye view – the perspective that heals divisions of all kinds.

As I began praying, this came to thought: “Stop worrying about your own self-concerns and get busy loving!” This was a wake-up call. The Bible encourages us to “love each other with genuine affection, and take delight in honoring each other” (Romans 12:10, New Living Translation). I’d been so caught up in my own insecurity that it was keeping me from genuinely loving this individual and freely embracing our shared connection as children of God, who is pure, infinite Love.

I’m learning from my study of Christian Science that beyond just a human definition of ourselves, our identity is more deeply rooted in the infinitely loving nature of our divine creator. So to really love one another in the highest sense is to acknowledge everyone’s identity as actually sourced in God.

Realizing, through prayer, that we are inseparable from divine Love fundamentally frees us from insecurities and fears that would hinder our freedom to reflect toward others the love that God expresses in everyone. I especially love the way this verse from the “Christian Science Hymnal” conveys it:

Though our fears may estrange and divide us,

May we seek to dissolve them through love.

We are sister and brother, each bound to the other,

One with our Father above.

(Mindy Jostyn, No. 524, alt. © CSBD)

I began to feel a divine kinship with this colleague, seeing beyond the human parameters of our identities and glimpsing the light of God’s love shining in us and our activities. For example, I was deeply grateful for the bighearted way in which she encouraged teens to stay in school and value their education.

The very next week, when I walked in the front door of the community center, there she was. Before I could say anything, she joyously welcomed me, calling from across the room, “Hi, Lisa!” This was a first. And I’m still in awe of how naturally a more heart-to-heart connection opened up between us after that.

“Love enriches the nature, enlarging, purifying, and elevating it.” This statement from the textbook of Christian Science, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy (p. 57), so encapsulates what transformed my heart and this relationship.

This is a modest example. But the more we let God’s all-embracing and all-defining love govern how we interact and care for each other, the more we find it leads the way to healing and reconciliation in our wider world as well.

A message of love

Champs again after 50 years

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow when we’ll take a look at the return of panthers to Florida. Like the grizzly bear in Montana and the gray wolf in Wisconsin, the panther’s resurgence raises a question: How can society adapt to large predators, whose populations have recovered thanks to decades of conservation?