- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

New Jersey takes a bipartisan stand for lemonade stands

We brake for lemonade stands. It’s a family rule.

When they were young, our daughters once sold cookies on a Boston sidewalk to pay for new bicycles. We hoped that it taught them the value of setting goals, taking initiative, and working for your dream.

That’s why we stop: We see our daughters in those pint-sized lemonade sellers. And, it’s our way of paying it forward.

But in some 34 states, child entrepreneurs are required to get a permit that typically costs more than any profits they might make. Well-intended child labor laws and sanitation rules are often the justification.

But on Monday, New Jersey joined a growing number of states taking a stand for junior free enterprise. A new law, signed by Democratic Gov. Phil Murphy, says municipalities cannot require a child under age 18 to get a license to run a temporary business.

The law stops “children [from] being harassed by local officials for running lemonade stands without permits,” said Republican state Sen. Michael Doherty in a statement. “Instead of providing space for kids to learn about entrepreneurship, they’re being taught harsh lessons about the heavy hand of government by overzealous bureaucrats.”

The new law, which passed unanimously, is an addendum to a 2016 law that allows kids to mow lawns and shovel snow for money. Yes, that was illegal too.

Sure, there are bigger injustices in the world today. But this sip of bipartisan progress reminds me that there are few moments as satisfying as a cup of roadside lemonade delivered with a child’s delighted smile.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

The Explainer

Inflation at 30-year high. Where it goes next is (partly) up to you.

Inflation is rising now, but what happens next is influenced by us, say economists – by our expectations about the future of prices and how we respond.

Inflation hit a 30-year high last month, according to federal data released today. The report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics adds new fuel to growing worries that recent price increases are not a temporary bump but the beginning of high inflation that could last – possibly for years.

American households are being strained by rising prices for everything from food and fuel to rent, child care, and automobiles. A basic theme is that, amid an evolving pandemic, consumer demand has rebounded more strongly than the supply of labor and goods.

Yet many economists are quick to point out several reasons the United States is unlikely to return to an era like the Great Inflation of the 1970s. For one thing, supply chain problems are expected to ease in the new year. The other big factor is the interplay between public expectations and monetary policy. And at present, consumers aren’t nearly as pessimistic as they were at the end of the 1970s.

Ultimately, this debate boils down to public confidence in the Federal Reserve. If the public believes the central bank can control inflation, the Fed will have a much easier time keeping prices from spiraling than if it loses public confidence.

Inflation at 30-year high. Where it goes next is (partly) up to you.

Inflation hit a 30-year high last month, according to federal data released today. The report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics adds new fuel to growing worries that recent price increases are not a temporary bump but the beginning of high inflation that could last – possibly for years.

American households are being strained by rising prices for everything from food and fuel to rent, child care, and automobiles.

A range of factors are taking some of the blame, from cargo-container traffic jams and constrained energy supplies to coronavirus relief programs that put extra money in consumer pockets.

But a basic theme is that, amid an evolving pandemic, consumer demand has rebounded more strongly than the supply of labor and goods. And now the question is, how long will inflation run hot?

The U.S. consumer price index is up 6.2% over the past 12 months, the strongest year-over-year gain since 1990. Wages are also up, by 4.9%, and Social Security benefits will be getting a 5.9% cost-of-living boost come January. Still, that doesn’t allay rising consumer worry. And upward pressure on wages – driven by a tight labor market – can become another reason for price hikes to continue.

Yet many economists are quick to point out several reasons the United States is unlikely to return to an era like the Great Inflation of the 1970s. For one thing, supply chain problems are expected to ease in the new year. The other big factor is the interplay between public expectations and Federal Reserve monetary policy.

One way to put it: The direction of long-term inflation depends partly on you. And that may be a hopeful sign, since public expectations currently aren’t near where they stood at the end of the 1970s.

Why are people worrying about inflation now?

The twin shocks of a national labor shortage and a worldwide pandemic have made some goods scarce and far more expensive than a year ago. Used car and truck prices were up 26% in the period from October 2020 to October 2021. New vehicles were up 10%, and food 5%. Much of the jump came from the energy sector, with gasoline up 50%. But even discounting the volatile sectors of energy and food, inflation over the past year still rose 4.6%, the highest rate since 1991.

Many analysts don’t mind inflation running higher than the Federal Reserve’s 2% target, to make up for the years since the Great Recession, when it was under the target. To others, however, like former Obama administration economic adviser Larry Summers, the handwriting is on the wall. “Until the Fed & Treasury fully recognize the inflation reality, they are unlikely to deal with it successfully,” he wrote in a lengthy tweet last month.

The Federal Reserve has acted preemptively in previous economic shocks, raising interest rates before inflation set in or lowering them in advance of a recession. (Raising interest rates slows the economy because loans cost more, so people and businesses delay making improvements or expanding. Lowering interest rates boosts the economy.)

This time the Fed is moving much more circumspectly. A week ago, the central bank announced it would start reducing its monthly purchase of bonds, which it has been using to support economic growth. This “tapering” would eliminate all that extra economic support by the middle of next year, opening the possibility of interest rate increases starting around late summer.

The latest data may speed up that timetable. “Given that Fed tightening moves are often prompted by market movements, unless inflation cools off very quickly on a sequential basis (which is looking less likely by the day), there would seem to be an increasing chance of the Fed’s hand being forced earlier than it is currently thinking in terms of an initial rate hike,” Joshua Shapiro, chief U.S. economist at consulting firm Maria Fiorini Ramirez, wrote in a note today.

This sharpening debate over whether inflation is transitory, as the Fed says, or longer-lasting has political implications. “Inflation hurts Americans’ pocketbooks, and reversing this trend is a top priority for me,” President Joe Biden said in a statement today after the inflation numbers were released. The president soon has to decide whether to reappoint Fed Chairman Jerome Powell – and signal his support for the Fed’s current direction – or nominate someone else. He also has three other appointments to make soon on the seven-member board.

What do you mean, inflation might depend on me?

To many economists, the persistent low inflation of the past 30 years has been rooted in a basic premise: that expectations of consumers, workers, and businesses are a key driver of what long-term inflation will be.

If they believe that inflation is long-lasting, consumers will buy more in the present, workers will demand higher wages, and firms will raise prices more readily than if they believe inflation is just a temporary jolt caused by a one-time shock to the economy.

“The most important development in monetary economics that I have witnessed over my now-long career has been the recognition that expectations are central to our understanding of the behavior of the aggregate economy,” Columbia Professor Frederic Mishkin, then on Fed’s board of governors, wrote in a 2007 paper.

It turns out that consumers are not particularly good at guessing inflation a year out. But they have been consistently closer to the mark when looking at inflation five years out. In the latest University of Michigan survey of consumers, they predict 6% inflation a year from now, while the Survey of Professional Forecasters pegged it at around 2.4%. Consumers’ five-year inflation outlook has been at 4% or under since the late 1990s – and stands at 3.8% now – a far cry from the 10.9% they recorded in 1980.

Another important group is business owners, because they have to set prices based on their outlook of future costs and their competitors’ future pricing, which of course depends in part on inflation. Firms’ expectations are even more volatile than consumers’, according to data from a new survey. Their outlook for inflation five years out is 4.9%.

Should I be worried?

It’s hard for anyone to take a step back and look at the long-term picture, especially when they’re confronted daily by rising prices at the gas pump, the car dealership, and the grocery store. But there are reasons for optimism.

First, major price rises aren’t across the board; they’re limited to specific goods where demand has outstripped supply.

“The goods that were expensive got a lot more expensive,” says Mark Witte, an economist at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. But “it’s really limited to a few things. ... Whereas if it were every good in the economy getting more expensive, that would be a lot more difficult” to fix.

Also, the supply chain shortages are likely to end. Businesses will find ways to boost supplies of those goods in short supply or find cheaper substitutes for them. Then there’s the pandemic. If it eases, then fear of returning to work is likely to lessen, boosting the flow of workers back to the workplace.

It’s worth remembering, however, that it was a flawed prevailing theory that may, in part, have kept the Fed from acting to stem inflation during the 1970s. The so-called Phillips curve suggested the cost of bringing inflation down was very high. Is the new theory, with its reliance on consumer sentiment, more solid?

One Fed economist caused a stir two months ago by publishing a paper calling into question that central tenet of expectations. “This belief rests on extremely shaky foundations, and a case is made that adhering to it uncritically could easily lead to serious policy errors,” Jeremy Rudd wrote. If the Fed relies too much on consumer expectations, it might miss the economy’s turn toward persistently higher inflation, he warned.

Ultimately, this debate boils down to public confidence in the Fed. If the public believes the central bank can control inflation, the Fed will have a much easier time keeping prices from spiraling out of control, than if it loses that public confidence. Last week, CNBC reported that a survey of millionaires conducted for it found that a majority – 53% – said they agreed with the Fed that inflation was “transitory.” But that was down from 72% the previous quarter.

Virginia’s wake-up call: Democrats ignore rural voters at their peril

After the Virginia election, our reporter looks at what both major parties might learn about the rising political power and perspectives of rural American voters.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Like most of rural America, southwest Virginia has become increasingly Republican in recent years. Former President Donald Trump has been widely credited with accelerating that trend, cranking up GOP turnout in rural counties across the country to win the White House in 2016.

Democrats have seen a growing edge in suburban and urban areas. Just last year, Joe Biden defeated Mr. Trump, and won Virginia by 10 percentage points, thanks in large part to strong support from suburbanites.

But Republican Gov.-elect Glenn Youngkin’s victory last week highlights a danger for the Democratic Party in this political realignment: The pool of potential GOP votes in rural America may be much bigger than either party realized. And although Mr. Trump helped supercharge that rural groundswell, it appears to be growing even in his absence from the national stage.

“For Democrats to be competitive in the midterms, they have to be able to compete for some of the rural vote," says Democratic strategist Jesse Ferguson. “There are voters in these communities that Democrats can win – but people need to have a sense that Democrats value work and working people.”

Virginia’s wake-up call: Democrats ignore rural voters at their peril

Shortly after Glenn Youngkin secured the Virginia GOP’s gubernatorial nomination, Andy McCready, chair of the Pulaski County Republicans, says he got a call from some data specialists on the Youngkin campaign.

“They sent me a printout of my county and said, ‘A typical Republican turnout in your county is 7,100 voters. Do you think we could get 7,300 voters to come to the polls?’” recalls Mr. McCready over a lunch special at Fatz Cafe, a restaurant off Interstate 81. “And I said, ‘Absolutely.’”

The Youngkin campaign didn’t just meet that goal – they obliterated it. Last Tuesday, Pulaski, a rural, majority-white county in the southwest part of the state, supplied Mr. Youngkin with 9,631 votes.

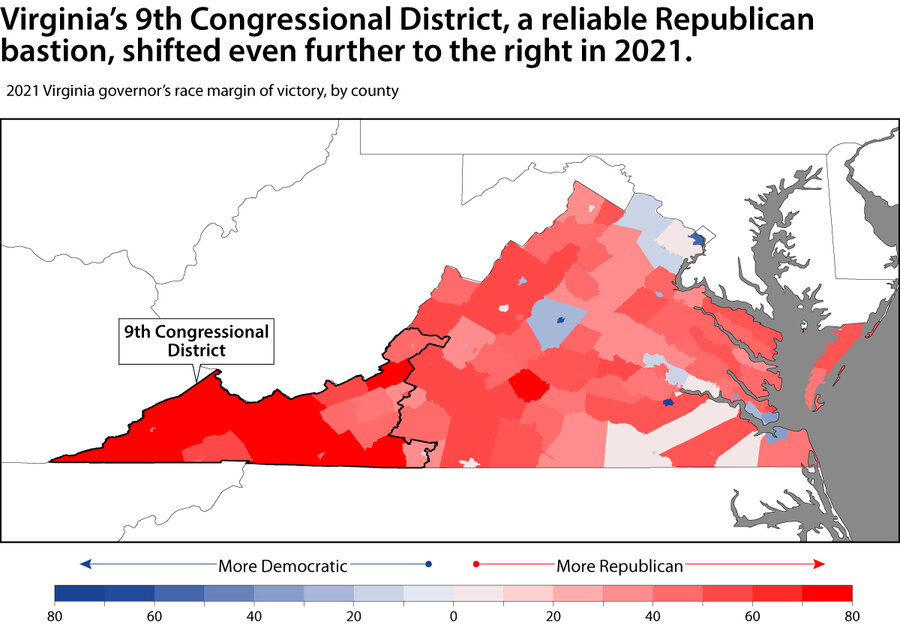

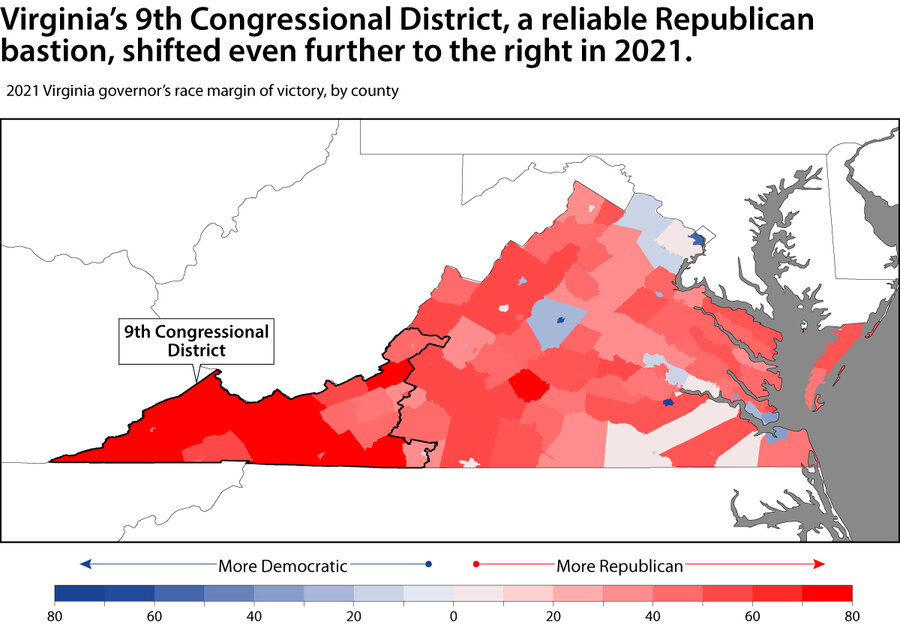

Like most of rural America, Virginia’s 9th Congressional District – a swath of mountains and farmland slightly larger than the state of New Jersey, and the poorest district in the state – has become increasingly Republican in recent years. Former President Donald Trump has been widely credited with accelerating that trend, cranking up GOP turnout in hundreds of Pulaskis across the country to win the White House in 2016.

On the flip side, Democrats have seen a growing edge in suburban and urban areas. In the “blue wave” of 2018, Democrats rode a tide of anti-Trump sentiment among educated voters to take control of the U.S. House of Representatives, including flipping three GOP-held seats in the Virginia suburbs. Just last year, President Joe Biden defeated Mr. Trump, and won Virginia by 10 percentage points, thanks in large part to strong support from suburbanites.

But Mr. Youngkin’s victory last week over former Democratic Gov. Terry McAuliffe highlights a danger for the Democratic Party in this political realignment: Namely, the pool of potential GOP votes in rural America may be much bigger than either party realized. And although Mr. Trump helped supercharge that rural groundswell, it appears to be growing even in his absence from the national stage. Mr. Youngkin actually surpassed the former president’s 2020 margins in every county in Virginia’s 9th district, running up the score a few thousand votes at a time.

Mr. Youngkin’s win can also be attributed to his success in the suburbs, where parental frustration over schools helped him cut into Mr. McAuliffe’s margins in the heavily populated counties outside of Washington D.C. He even flipped some suburban areas that had voted for Mr. Biden, such as Chesterfield and Virginia Beach.

But it’s the unexpectedly large rural turnout that has many Democratic strategists most worried ahead of next year’s midterm elections, when the party will be defending its razor-thin congressional majorities. It’s not that Democrats need to win in rural America to win overall, they note. But they can’t lose by those kinds of margins and remain competitive.

“There is a world of difference between losing a county 65 to 35 versus 80 to 20,” says Jesse Ferguson, who was deputy national press secretary for Hillary Clinton’s campaign in 2016 and has worked on a Virginia gubernatorial campaign. “For Democrats to be competitive in the midterms, they have to be able to compete for some of the rural vote."

“There are voters in these communities that Democrats can win – but people need to have a sense that Democrats value work and working people,” Mr. Ferguson adds.

Waiting on an “emerging Democratic majority”

In some ways, the Virginia results serve to undercut a theory on the left that demographic changes in the U.S. – particularly the growth of non-white populations and the progressive tilt of younger generations – would increasingly work to the Democratic Party’s advantage, eventually giving them an overwhelming advantage at the polls. Since the book “The Emerging Democratic Majority” was published in 2002, there has been a line of thinking among Democrats that they don’t actually need to appeal to rural voters, says Robert Saldin, a professor of political science at the University of Montana.

It’s possible demography will still favor Democrats in the long run. But in recent cycles, Republicans’ gains among white, working-class voters have arguably had a bigger impact – particularly since the Senate and Electoral College give disproportionate weight to underpopulated states.

“People have been waiting for this emerging Democratic majority for two decades,” says Mr. Saldin, author of the recent report “Gone Country: Why Democrats Need to Play in Rural America, and How They Can Do It Again.”

Southwest Virginia, like many rural areas, has actually has seen its population as a whole shrink. Of the 29 counties in the 9th district, all but five have lost residents over the past decade according to the U.S. Census, with several losing at least 10% of their population.

Likewise, there are almost 125,000 fewer registered voters in Virginia’s 9th district than in the 10th, which includes Fairfax and part of Loudoun County, just outside of the nation’s capital.

Yet Republicans are still finding plenty of room to grow.

Over the past year, Pulaski’s local GOP committee saw its numbers quintuple. The original group of 15 party stalwarts, which used to meet in a little room at the public library, had to relocate over the summer to a space that could hold more than 100 people.

Chip Craig, chair of the nearby Radford Republicans, has seen an even greater surge in growth. A small university town that was one of the last blue bubbles in southwest Virginia, Radford backed Mr. Biden in 2020, by 3,358 votes to 2,786. Last week, Mr. Youngkin won it 2,266 to 1,879.

“You have the disaster going on in Washington right now, and then you have McAuliffe going after parents and education,” says Mr. Craig, taking a break from cleaning up leaves in his yard, which is still dotted with campaign signs. “A lot of people out there felt disaffected and desperately wanted to do something.”

New York Times, Associated Press

Much of the media coverage of the governor’s race focused on education as an issue impacting suburban voters. But the same concerns – school closures, mask mandates, and curriculum changes around race and identity – were powerful motivators for many rural voters as well.

Unhappiness with the Pulaski public school system led BJ Ratliff to pull her kindergartener out and enroll her in a private school. While she and her husband are having to work more to pay for their daughter’s education, she says it’s been worth it, adding that she knows two other local families who did the same thing.

“As bad as COVID-19 was, there were some hidden blessings. Parents began to see what the education system was teaching their children – and they didn’t like it,” says Republican state Sen. Travis Hackworth, who won a special election in Virginia’s 38th district with more than three-fourths of the vote earlier this year. “That goes for rural parents as well.”

“He looked us in the eye and listened”

In conversations with more than a dozen voters across southwest Virginia, many point to Mr. Trump as igniting their interest in politics and their enthusiasm for the GOP. Many still have questions about the integrity of the 2020 election, which the former president has continued to insist was stolen, despite all evidence to the contrary. And they express deep unhappiness with President Biden for “teaming up with progressives” in an effort to pass multi-trillion dollar legislation.

But they also give plaudits to Mr. Youngkin, saying he made them feel like their vote mattered.

“He looked us in the eye and listened,” says property manager Julie Muir, sharing an order of Cajun “firecracker stix” with her husband, Randy, at Fatz’s.

“We saw him so many times in this area,” adds Randy, who’s retired from a career in marketing. “He cared about getting 200 extra votes in Pulaski, 200 more in Lee, in Scott, and in Tazewell. I love it here in this ‘flyover type county,’ and I love the people here. But we are forgotten. We’re seen as small potato stuff.”

Mr. Craig says the Radford Republicans are taking some time off after months of door knocking, phone banking, and fundraising – and a celebratory dinner this Thursday. But then the planning will start for next year’s elections, says Mr. Craig, particularly three seats on the city council and three seats on the school board, for which he already has potential candidates.

“Now that they see we can win, I think we can get even more people registered,” says Mr. Craig. “People are motivated and ready to get after it.”

New York Times, Associated Press

Patterns

Solution to divide-and-conquer strongmen: Unity

In several democratic nations, our London columnist finds evidence that political pragmatism, unusual alliances, and collaboration may offer lessons in how to counter populist strongmen.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Populist strongmen often maintain their grip on power not so much by restricting or arresting their opponents as by dividing them.

Now, from Hungary to Brazil, opposition leaders are forming coalitions to fight upcoming elections on common platforms, in hopes they will find strength in unity.

That sort of tactic worked last summer in Israel, where a very disparate group of parties united to unseat Benjamin Netanyahu, prime minister for over a decade. And this week, a new government was being formed in the Czech Republic, backed by a pair of opposition alliances that between them had won a majority in recent elections.

Out went Andrej Babiš, the billionaire populist premier who is facing corruption charges at home and abroad.

This strategy is also being tested in Hungary, where self-proclaimed “illiberal democrat” Viktor Orbán faces elections next year, and in Turkey, where Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has dominated politics for nearly two decades.

Perhaps the most closely watched test for populism will come next year in Brazil, when President Jair Bolsonaro goes to the polls. He is likely to face a challenge from leftist Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

And what has Lula been doing in recent weeks? Conferring with allies and rivals, on both left and right, so as to build a coalition.

Solution to divide-and-conquer strongmen: Unity

In more tranquil geopolitical times, last week’s news would barely have raised an eyebrow: A sitting government won parliamentary approval for the country’s annual budget.

Yet for the government in question – the unlikely coalition of mismatched parties that recently unseated Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu after more than a decade – it was a significant milestone.

And it had implications beyond Israel. Because opposition parties in a number of other countries where democratic governance has been eroded by strongman populist rulers are also studying the former Israeli opposition’s playbook.

It’s too early to say the tide has turned. But with election tests on the horizon in a number of European states – and in South America’s largest country, Brazil – opposition challengers are crafting strategies drawing on Israel’s experience. They are setting aside policy differences in a bid to build broad fronts opposing the divisiveness, authoritarianism, narrow nationalism, and, in some cases, personal corruption of entrenched populist incumbents.

This week, that approach chalked up another success, in the Czech Republic.

The president directed that a new government be formed, backed by a pair of opposition alliances that secured an overall majority in elections last month, ending the rule of billionaire populist Andrej Babiš. Facing corruption charges both at home and abroad, he had taken a hard-line stand on immigration and vowed to “make the Czech Republic great again.”

A few hundred miles to the south in Hungary, opposition politicians have just launched an alliance to challenge the self-proclaimed “illiberal democracy” of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. He has used his 11 years in power to tighten constraints on judicial and media independence, while stoking anti-immigrant and antisemitic rhetoric and intolerance toward minority groups.

A half-dozen groups from across the political spectrum held a joint primary vote last month to choose a candidate to lead the fight against Mr. Orbán’s Fidesz party in parliamentary elections next spring. Their choice was rooted in political pragmatism. It was not one of Mr. Orbán’s longtime critics from the left, but a small-town mayor named Péter Márki-Zay, a devoutly Catholic conservative who has pledged to restore democratic institutions and repair Hungary’s increasingly frayed relations with the European Union.

The populist strongman leading Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has been in power even longer than Mr. Orbán and need not face the voters until the summer of 2023. But he, too, now faces the prospect of a united front.

Six major opposition parties have begun assembling a broad alliance, whose aim is not just to unseat Mr. Erdoğan – who has used broad anti-terror laws to hobble the judiciary and jail critics – but to restore Turkey’s parliamentary democracy.

Perhaps the most closely watched electoral test for populist politics will be in Brazil, where President Jair Bolsonaro – a flamboyant right-wing ideologue whose attacks on the news media and dismissive approach to the pandemic have drawn comparisons to Donald Trump – faces the voters a year from now.

His likely, though still undeclared, challenger is former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

A center-left politician who rose through the labor union movement, Lula ruled as something of a populist himself. But in increasingly open moves to mount a comeback run against Mr. Bolsonaro, he and his supporters have been seeking to forge the kind of broad opposition strategy taking shape across the Atlantic.

In a series of meetings with politicians last month, he conferred not only with longtime allies of his Workers Party, but with centrist and right-of-center figures as well, framing the contest against Mr. Bolsonaro as a fight to ensure a “humane” and democratic presidency.

None of this, however, means the ruling populists are destined for defeat. All have shown a talent for galvanizing grassroots enthusiasm and support, and they still have the levers of state to pull, and influential media allies to carry their messages.

Last week’s budget vote in Israel, in fact, underscored the scale of the task faced by even a united coalition. Now leader of the opposition, Mr. Netanyahu led a strident effort in parliament to vote down the budget, and force new elections.

It was a stiff test of the staying power of the mosaic of parties – right of center and left, Jewish and Arab – that had combined to usher him out of power. And the alliance held.

In forging unity coalitions elsewhere, opposition leaders will be aware of the difficulty of the political battles ahead.

But, ironically, they seem to be counting on a potential edge that they’ve long ceded to the populists. Strongmen have often maintained their grip on power not so much by restricting or arresting their opponents, as by dividing them.

In opting instead for unity, those opponents are hoping that they may have found populism’s Achilles’ heel.

On climate, a fraught Plan B: Carbon capture helps, but not enough

What are the nature-led and tech-inspired efforts intended to help slow global warming? Our reporter looks at the pros and cons of various carbon capture solutions.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Everybody at the U.N. climate summit in Glasgow, Scotland, knows that the fundamental climate challenge is to reduce the world’s carbon emissions sufficiently to keep global warming within livable limits.

But if that effort falls short, could we make nature or technology do the work for us, capturing and storing carbon?

There are natural ways of doing this – planting trees, for example, or restoring mangroves. And there are artificial ways: A Swiss company is perfecting a machine that sucks carbon out of the atmosphere and stores it in Icelandic rock. And there are naturally engineered ways – such as growing trees to fuel a power plant that captures and stores its carbon emissions, and then replanting trees.

Debate over the pros and cons of such alternatives, and their limitations, is fierce, and some pioneers are combining different approaches. But Frederic Hauge, head of a Norwegian environmental nonprofit, is blunt about what’s at stake. Without carbon capture and storage of some kind, he warns, “the world will be cooked.”

On climate, a fraught Plan B: Carbon capture helps, but not enough

If a tree that falls in the forest is fed into a power plant, and the carbon emitted is captured and stored, is it helping to save the planet?

Under United Nations carbon accounting rules, it would be: Provided the tree is replaced, the entire process takes more heat-trapping carbon out of the atmosphere than it puts in.

This and other experiments in carbon removal and storage offer leaders at the U.N. Climate Change Conference here a morally fraught Plan B: If they fail to reduce carbon emissions sufficiently to curb disastrous global warming, then they attempt to make nature or technology do the work.

The experiments also pose a puzzle. If such fixes are to be considered, where is the line between natural solutions – planting trees, restoring mangroves, or protecting wetlands – and artificially engineered ways of drawing down carbon?

That line can be blurry, say analysts, but neither option is a substitute for the hard task of making deep and rapid cuts in emissions.

“Capture [of carbon] only makes sense in a world where you’ve already gotten down pretty close to zero” emissions, says Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist at Carbon Brief, a specialist website.

In Glasgow, the gap between where those emissions of heat-trapping gases need to be and where they’re headed remains a major sticking point in the final stretch of negotiations.

Carbon capture’s appeal

Even if governments meet their new pledges, global temperatures would likely rise to a catastrophic 2.7 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2100, according to the U.N. Environment Program. The 2015 Paris Agreement committed to holding temperature rise close to 1.5 degrees.

That’s why the lexicon of “negative emissions” – capturing emissions that don’t fall fast enough – is echoing on the sidelines of the Glasgow summit known as COP26, even among environmentalists who have spent decades turning their backs on such ideas.

“The world will be cooked without [carbon capture]. There are no scenarios bringing us under two degrees,” says Frederic Hauge, founder and president of Bellona, a Norwegian environmental nonprofit.

Some experts propose a purely technological fix: Suck and filter carbon out of the air using giant fans. A Swiss company is already doing this on a small scale in Iceland. The downside to such a simple solution? It costs about $600 per ton of carbon stored in Icelandic rock. And direct air capture machines would use up a quarter of global electricity supply by 2100 if enough of them were operating to make a significant difference to atmospheric CO2 levels, according to one study.

Proponents of natural systems to adapt to a warming planet are wary of such technological fixes to remove carbon. And they appear to be winning the debate: A draft of the COP26 final declaration refers to the “critical importance of nature-based solutions and ecosystem-based approaches ... in reducing emissions, enhancing removals and protecting biodiversity.”

More than 100 countries also signed on to a Glasgow declaration against deforestation, which if upheld would protect much of the world’s remaining forests after decades of cutting that has sapped their capacity to store carbon.

As to that tree ...

So what about that tree that fell in the forest? In fact, the forest may be in Mississippi, where Drax, a U.K. power-plant operator, sources its wood chips. And the carbon that would otherwise float into the atmosphere? It would be buried in the rock under the North Sea off the coast of England, where miles of gas pipelines and other offshore oil fixtures are being repurposed.

This technology, known as Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS), is backed by the U.K. government, which is aiming for net-zero emissions by midcentury. But while Drax has converted a giant coal plant to burn biomass to produce electricity, it is far from carbon-neutral. It may be several years before it can start to bury any captured emissions. Critics say it’s a risky and unproven experiment that will never recoup billions of dollars in public investment.

Even if BECCS does eventually remove carbon, it doesn’t provide any of the benefits that come with restoring and protecting diverse ecosystems, says Nathalie Seddon, who directs Oxford University’s Nature-based Solutions initiative. Another drawback is that reserving land for timber means less for food. And monoculture forests are at greater risk of disease and fire. “It will go up in smoke,” Professor Seddon warns.

That should give pause to anyone who thinks we can rely on nature to sequester unchecked carbon emissions, says Joeri Rogelj, director of research at the Grantham Institute for Climate Change at the London School of Economics. “Relying on the natural system to function fantastically in taking up carbon is not the most robust approach to safeguarding the future,” he says.

Limits of natural sequestration

This is another reason why the idea of natural carbon sequestration is not as appealing a green solution to emissions as it looks, says Mr. Hausfather, of Carbon Brief. Extracting and injecting carbon into rocks may be expensive, he acknowledges, but rocks aren’t at risk of wildfires or pests, or being felled in the future.

“The problem with focusing on nature-based solutions is that there’s a real risk the carbon isn’t going to stay there,” he says.

Mr. Hauge says a better alternative to harvesting trees to burn purely for electricity is to process plant matter into biochar that can fertilize land, thus increasing crop yields, while extracting biofuels for power. His nonprofit is also working in Jordan to grow trees in deserts that would otherwise yield no crops. “You need to plant now to get the biomass you need in 10 years,” he says.

Professor Rogelj, one of the authors of the UNEP report on the COP26 emissions gap, reckons some form of carbon capture will be necessary to abate the emissions that can’t easily be decarbonized, such as air travel and production of cement and steel.

But he warns that carbon-capture technologies like BECCS won’t solve the immediate problem: Emissions are warming the planet beyond the point where either natural or engineered drawdowns can bend the curve. “We still need emission reductions,” he insists. “We need to emit less CO2 because we cannot compensate for it with BECCS.”

Essay

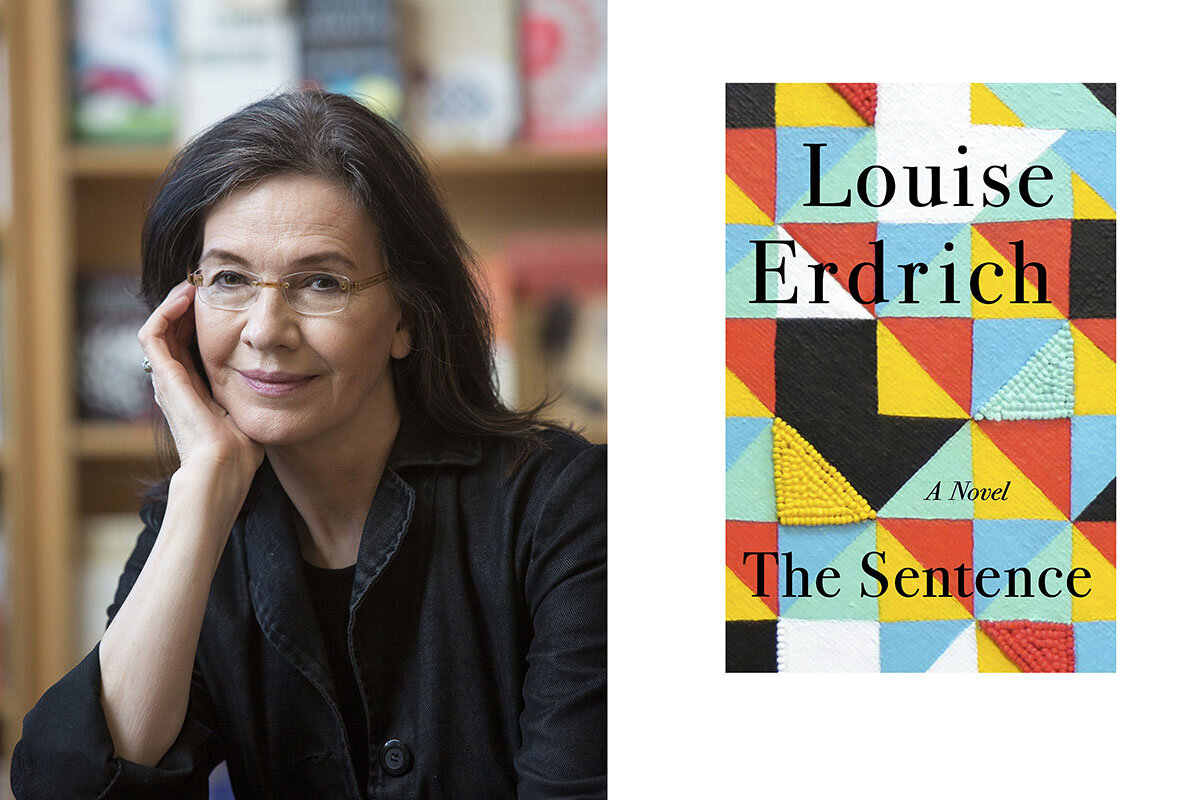

Louise Erdrich, Minnesota, and me

Our reporter offers an engaging blend of personal encounters with this Pulitzer Prize-winning author, and a review of a novel about the racial reckoning in Minneapolis. It’s a book that sheds “love and light” on her hometown and “its deep-seated challenges.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Colette Davidson Correspondent

Minnesota native and Monitor correspondent Colette Davidson, who reports from Paris, is an unabashed fan of author Louise Erdrich. She’s run into Ms. Erdrich on three occasions, twice in Minnesota and once in Paris – and each time, Ms. Davidson was facing personal challenges.

The latest sighting occurred when Ms. Davidson and her family were visiting Minneapolis for the first time since the pandemic began. Ms. Davidson had wanted to reconnect with her hometown and process what had happened in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder. The family stopped in at a bookstore owned by Ms. Erdrich, never expecting to see the author, but there she was.

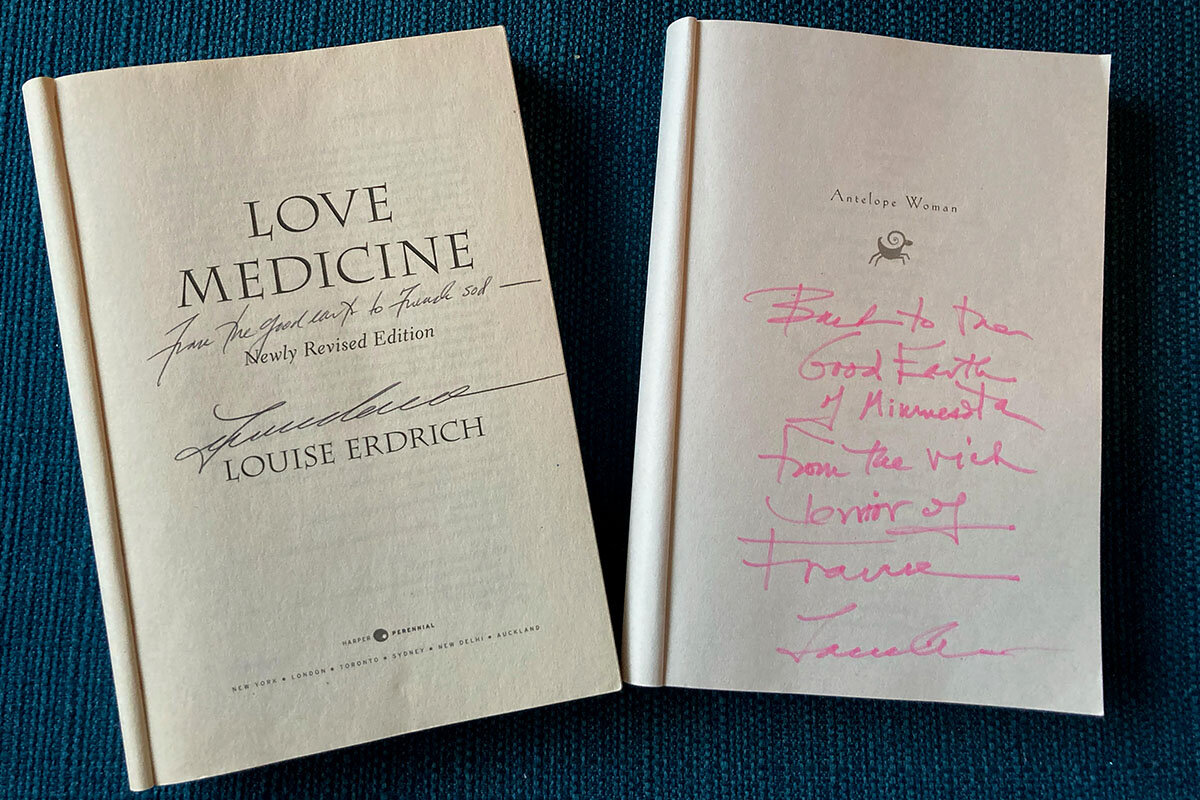

Ms. Davidson approached Ms. Erdrich and asked which of her books was her favorite. The author pulled out “Antelope Woman” and inscribed it: “Back to the Good Earth of Minnesota, from the rich terroir of France. Louise Erdrich.”

Back in Paris, Ms. Davidson read Ms. Erdrich’s latest novel, “The Sentence,” which deals with the racial upheaval in Minneapolis, and felt she was beginning to understand her hometown. Through Ms. Erdrich’s words, she had come full circle. She was home.

Louise Erdrich, Minnesota, and me

I’ve met Louise Erdrich three times in my life. For some mysterious reason, the acclaimed author always seems to appear at exactly the moment where everything is going belly-up in my life: A potential move abroad. A breakup. A global pandemic.

The first time was amid a quarter-life crisis about whether to move overseas. On a dull day waitressing at the Good Earth restaurant in Minnesota, I happened to see her name on the credit card slip.

“Are you Louise Erdrich, as in, the writer?” I sputtered. She nodded graciously as I blathered on about my love for her books.

It was ironic, then, that I went to see her at a Paris book fair nearly a decade later – after my subsequent move abroad and a harsh breakup – in search of a sense of home.

“From the good earth to French soil,” she wrote inside the cover of my copy of “Love Medicine.”

Now, 20 years after that first meeting, Ms. Erdrich has published “The Sentence,” a fictional ghost story that takes place in her real-life bookstore in Minneapolis, Birchbark Books. In it, she tackles George Floyd’s murder and its violent aftermath, Indigenous peoples’ rights, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

For people like me, who’ve been stuck thousands of miles away and unable to properly grasp my hometown’s pain, upheaval, and growth, Ms. Erdrich creates a rare portal into life in Minneapolis over the past 18 months. The main characters in “The Sentence” air common grievances, push readers to reflect on their own biases, and provide an intimate look at the city’s reckoning and rebirth.

“Everything seemed to be cracking: windows, windshields, hearts, lungs, skulls,” she writes. “We may be a striver city of blue progressives in a sea of red, but we are also a city of historically sequestered neighborhoods and old hatreds that die hard or leave a residue that is invisible to the well and wealthy, but chokingly present to the ill and the exploited.”

I couldn’t have known it then, but as I embarked on my first trip home in two years this summer, my life and Ms. Erdrich’s work would overlap once again. Not just in our third and most fortuitous encounter yet, but in parallel discoveries of our city – a Minneapolis split apart, exposed, and sewn together again.

Seeking a connection

I watched the video of George Floyd’s murder last year along with the rest of the world. But as a Minnesotan far from home, I felt helpless, detached, and yet seeking more connection to home than ever.

Mr. Floyd was killed just blocks from my brother’s apartment. My friends worked across from buildings that were torched during the violence that followed his death. I became obsessed with the trial of now-convicted police officer Derek Chauvin, streaming it from my Spanish in-laws’ apartment in June.

Now, at last, there I was in George Floyd Square in Minneapolis amid teddy bears, flowers, and artwork, to remember the man whose tragic death became a wake-up call for my hometown. His killing squashed misconceptions of a harmonious, discrimination-free, “Minnesota nice,” and gave way to the realities of redlining, racial covenants, and over-policing of minority communities.

“It gives me hope that people are listening and doing things, talking about diversity, inclusiveness, and sharing their experiences,” says Angela Harrelson, Mr. Floyd’s aunt. She was in George Floyd Square almost every day, chatting with visitors about whatever was on their minds. “People don’t want to live in fear anymore.”

Ms. Harrelson recognizes the confluence of her nephew’s murder with other acts of injustice in America – Native American land rights, climate change, social injustice, the pandemic’s disproportionate impact on ethnic and racial minority populations.

It’s exactly these themes, and the emotions they unleash, that “The Sentence” works to address. Through Ms. Erdrich’s main characters, readers experience the frustrations of racial inequality and the precariousness of life during a pandemic. Her bookstore clients – desperately and awkwardly searching for connection with the Indigenous community – feel too real to be fiction. She even places herself as the owner, also named Louise, of the bookstore where her story takes place.

“’There is something in me that aches to do the wrong thing,’ said Louise. ... ‘I almost always resist, but I understand when other people don’t. The urge is very strong,’” she writes.

With such true-to-scale depictions, “The Sentence” fulfills a longing in people like me to not just hold my hometown in love and light, but to understand its deep-seated challenges.

The third meeting

On the most recent visit to Minneapolis, I wanted to show my husband and daughters Birchbark Books, never expecting to see Ms. Erdrich there. But when a figure breezed through the front door and began signing books in the back room, I couldn’t believe it. My husband asked me if I was going to say hello.

“Only if it’s natural,” I said, silently hovering by the cash register until she made her way over.

“Hi there, thanks for coming in,” she said, when our gazes finally met.

I introduced myself, referencing our two past encounters. She flattered me, saying she remembered, even though we were both wearing medical-grade face masks. Then I asked what her favorite book was of those she had written. From a sky-high stack she was holding, Ms. Erdrich pulled out a light blue paperback.

“It’s kind of a secret book,” she said.

It was “Antelope Woman,” a newly edited version of “The Antelope Wife,” the first book she published after her husband, writer Michael Dorris, took his own life in 1997. She signed it, referencing our very first Good Earth meeting a million lifetimes ago, and offered it to me as a gift.

Now, as I sit in my Paris apartment, my two signed copies on the bookshelf and Ms. Erdrich’s most recent book on my nightstand, I wonder what effect writing “The Sentence” has had on the author herself. Did it help her process the last 18 months of her life? Has it brought her peace?

“When everything big is out of control, you start taking charge of small things,” she writes in “The Sentence.”

I can only speak to my own experience. Just like those first days in Minneapolis this summer, when I couldn’t focus my thoughts until I had visited George Floyd Square and wrestled with the demons that my city faced, reading “The Sentence” has allowed me to properly grieve.

It has shown me not just what I missed from home but what I was missing – the good, the bad, and the ugly. It’s a rare gift she’s given me – to all of us.

If, by some miracle, I should happen to meet Ms. Erdrich for a fourth time, I’ll be sure to thank her.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A light of truth on Nicaragua’s shady election

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

A record number of migrants from Nicaragua have shown up at the U.S. border so far this year. Why the surge? Many have fled the authoritarian rule of President Daniel Ortega, a former leftist guerrilla leader whose regime has killed hundreds of protesters, jailed political opponents, and ruined the economy. With many democracy activists fearful of reprisals, Mr. Ortega confidently held an election last Sunday to give himself a fourth consecutive term. After all, seven leading presidential hopefuls had been arrested. He easily won, but more important, officials claimed voter turnout was 65%.

Yet in a brave act of truth-telling, more than 1,450 Nicaraguans in a group called Open Ballot Boxes quietly tracked the number of people who voted at 563 polling stations. They estimated the average turnout was about 18%. This independent estimate of voter turnout has helped puncture a big lie about Mr. Ortega’s legitimacy to rule. It also confirms that the opposition’s campaign for an election boycott, called “Let’s Stay at Home,” had largely worked.

The truth about the voter turnout sent a subtle message to a ruthless regime that it is individuals, out of their innate dignity and freedom, who set society’s norms.

A light of truth on Nicaragua’s shady election

A record number of migrants from Nicaragua have shown up at the U.S. border so far this year. Why the surge? Many have fled the authoritarian rule of President Daniel Ortega, a former leftist guerrilla leader whose regime has killed hundreds of protesters, jailed political opponents, and ruined the economy. With many democracy activists fearful of reprisals, Mr. Ortega confidently held an election last Sunday to give himself a fourth consecutive term. After all, seven leading presidential hopefuls had been arrested. He easily won, but more importantly, officials claimed voter turnout was 65%.

Yet in a brave act of truth-telling, more than 1,450 Nicaraguans in a group called Open Ballot Boxes quietly tracked the number of people who voted at 563 polling stations. They estimated the average turnout was about 18%, not 65%, for the country’s 4.4 million registered voters. Many of those who did cast ballots were driven to the polls in government vehicles or coerced to vote, the group witnessed.

“You don’t feel fear,” one poll observer told the Los Angeles Times about her experience. “You feel that at least you’re doing something.” Several members of the group were detained by security forces.

This independent estimate of voter turnout has helped puncture a big lie about Mr. Ortega’s legitimacy to rule. It also confirms that the opposition’s campaign for an election boycott, called “Let’s Stay at Home,” had largely worked.

While the election was condemned as fraudulent by dozens of countries, a return to a full and fair democracy in Nicaragua seems far off. Mr. Ortega has a firm grip on the military. But the stealth counting of voters by Open Ballot Boxes hints that democracy advocates have adopted a tactic made famous during the Cold War when public protests in the Soviet empire were nearly impossible. The late Czech dissident Václav Havel advised people to “live in truth,” or conduct their daily lives in a way that exposes a regime’s false narratives.

“I have my conscience and thumb clean,” one Nicaraguan retiree told the Havana Times after refusing to vote.

The truth about the voter turnout sent a subtle message to a ruthless regime that it is individuals, out of their innate dignity and freedom, who set society’s norms.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

A return to Vietnam

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Steve Thorpe

All too often, military veterans struggle with painful or traumatic memories, even after their service has ended. But lasting healing and peace of mind are never out of reach, as a Vietnam War veteran experienced after years of guilt and resentment that were hampering his ability to move forward with his life.

A return to Vietnam

Sometimes after a war experience, people have painful memories that take time to heal. When I was a soldier in Vietnam, I had to work through the anger, resentment, and guilt that I was feeling by the end of my tour.

At one point, three of us were assigned to guard one section of the perimeter of our compound. As we huddled in our bunker, we took a direct hit from a rocket-propelled grenade, which killed my friend and temporarily blinded the other man with us. After finding someone to get them out of there, I learned that I would now have to guard that portion of the perimeter by myself.

Fear began to overwhelm me. Since in the past I had relied on prayer to get me through many tough situations, it seemed natural to turn to prayer again. As I began to pray, it became clear to me that God would protect me. This enabled me to calm down enough to guard my post for the rest of the night.

In the morning, when someone came to relieve me, he asked if I was aware that I’d been wounded. I had not realized that shrapnel from the grenade had injured my arm.

A few weeks later, I realized that all that had gone on that night had made a deep impact on my emotions. I began to question why my friend had been killed and not me, to feel guilty that I had survived and he had not, and to feel that I should have been able to do more to save him.

Over the next 10 years I struggled with guilt. I also felt resentment and anger toward the people of Vietnam, as well as toward my own government for having drafted me. And because I was so focused on this negativity, I wasn’t making much progress in my life.

Finally, I had a moment of absolute clarity: The only way I was going to get myself out of this ongoing lethargy and negativity was to commit myself to a consecrated spiritual path. I needed to live the spiritual principles and teachings I’d learned in Christian Science. Starting from that very day, I began to experience healing of those long-held feelings of guilt, resentment, and anger.

I made a commitment to study the Bible and the textbook of Christian Science, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, more deeply. As I began this study, I gained the peace of mind I’d been searching for. I had more clarity in my thinking. I was able to see opportunities and make wiser and more beneficial decisions about my future.

This included becoming a lawyer, and accepting a fellowship as a staff attorney working for the National Veterans Service Project, representing the rights of veterans. The work gave me a great deal of satisfaction. It made me feel that I was giving something back to veterans and honoring my friend.

A few years later, another opportunity came up in which I could help bring healing to others: going to Vietnam with a nongovernmental organization (NGO) to visit sites that have been built to help children affected by the Vietnam War.

During this trip, I decided to revisit the place where I had been wounded so many years earlier. So I hired a driver to take my wife and me to my old base camp in Dau Tieng, and we walked around the village – which had since become a city – for a while.

A few days later, on the plane back to the United States, I had time to reflect on my visit to Dau Tieng. I realized that the past no longer had any hold on me. I had, indeed, been completely healed of all those painful memories. I also realized that while my own life had continued on and I had grown and developed into a new person, the Vietnamese, too, had made their own progress. It was clear even from my brief visit that Dau Tieng was a different place from what it had been during the war, and the people were changed, too.

Maybe the most significant part of my healing has been my realization that everyone is worthwhile. No one is a “faceless enemy.” Each of us, regardless of nationality or which side we take in a conflict, is equally loved by God. This is the truth I needed to learn to heal the wounds of war and find peace of mind.

Adapted from an article published in the May 5, 2003, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

A tomb turns 100

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. We’ve got a special Veterans Day issue for you tomorrow. For Friday, we’re working on a review of the new documentary film about the world’s first celebrity chef, Julia Child, and her influence on cooking.