- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A man, a plan, a canal ... happy palindrome month!

For as long as I can remember, I have been fascinated by symmetry in words and numbers. And on Wednesday, 12/1/21, it hit me: We had entered a month of palindromes, 11 out of 31 dates that read the same backward and forward, at least in the American “month/day/year” way of doing things.

I noted this on Facebook, and launched a frenzy of palindromania – friends sharing their favorite words, phrases, and sentences that read the same in both directions: “Tuna Nut,” the name of a friend’s boat. “TacoCat,” a card game, rock band, and now crypto token. “Able was I ere I saw Elba,” as Napoleon allegedly said upon his exile.

The best-known example of all time is “A man, a plan, a canal: Panama” according to the Palindrome Hall of Fame. But when my friend Eric Troseth offered this – “Are we not drawn onward, we few, drawn onward to new era?” – I stopped in my tracks. The potential for deep meaning is vast.

Indeed, the Hall of Fame includes this marvelous example from the ancient Greek, transliterated: “Nipson anomemata me monan opsin,” meaning “Wash the sins, not only the face.”

Love of palindromes is a rabbit hole down which one can vanish forever – or at least as a break from the headlines. This palindrome-filled video by “Weird Al” Yankovic guarantees a laugh.

But before I go, I must point out something especially remarkable about yesterday’s date: 12/02/2021. Ignore the slashes and write the numbers in digital script, and you get the rarest of palindromes, an ambigram: Left, right, upside down, it reads the same. Wow.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Global vaccine equity: Calls rise to put principle into practice

The concept of vaccine equity has always been supported by a combination of altruism and self-interest. To combat the still-undefeated pandemic, is the world ready to act on principle?

-

Ryan Lenora Brown Staff writer

-

Lenora Chu Special correspondent

-

Nick Roll Correspondent

Wealthy countries and international institutions created COVAX in April 2020 to ensure global access to coronavirus vaccines – including in the world’s poorest countries. Underpinning the initiative was both the principle of vaccine equity and the understanding that in a highly globalized world, no country could defeat a pandemic on its own.

But that early sentiment soon yielded to domestic pressures and the impulse to take care of one’s own. Wealthy countries bought up and hoarded vaccines.

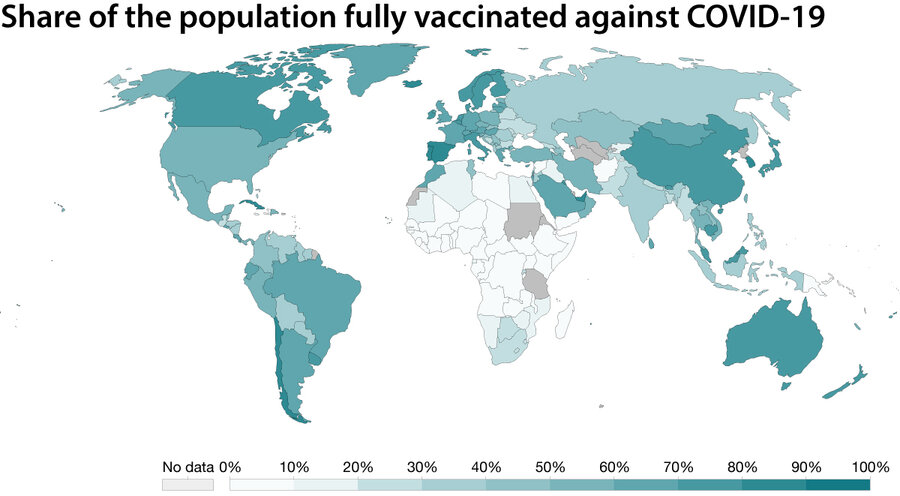

Initially hailed as the great equalizer in vaccinating the world, COVAX has distributed just 5% of the world’s COVID-19 vaccines. One result: Africa has vaccinated only about 6% of a population of about 1.4 billion, according to the World Health Organization.

Yet for many global health experts, the emergence of the omicron variant, apparently in South Africa, underscores the practical wisdom behind the lofty-sounding vaccine equity that created COVAX. Moreover, they add, it should prompt a rededication to the idea that in a pandemic, helping others is as much about self-preservation as it is about charity.

“The point that vaccine equity is not just altruism but is critical for getting out of this pandemic is still the main lesson to be learned,” says Richard Marlink, director of Rutgers’ Global Health Institute. “Clearly we haven’t learned it yet.”

Global vaccine equity: Calls rise to put principle into practice

When Gambia received its first shipment of 36,000 doses of COVID-19 vaccine in March through the global initiative COVAX, the mood at the West African country’s Health Ministry was upbeat.

“We gave people their first doses, and told them the date to come back for the second,” says Mustapha Bittaye, the ministry’s director of health services.

That initial shipment and the ability to plan for vaccination follow-through nurtured a sense that the world was making good on an early-pandemic commitment. In a rush of both altruism and self-interest, wealthy countries and international institutions had created COVAX in April 2020, pledging to ensure global access to coronavirus vaccines – including in the world’s poorest countries.

Indeed, underpinning COVAX was both recognition of the concept of vaccine equity and the understanding that a pandemic in a highly globalized world meant that no country could hope to defeat COVID-19 on its own. According to epidemiologists, the unchecked spread of the virus in unvaccinated populations increases the possibility that mutated variants of the virus could emerge that are deadlier, impervious to existing vaccines, or both.

But that early sentiment of “we’re all in this together” soon yielded to domestic pressures and the impulse to take care of one’s own. As wealthy countries with the financial means bought up and hoarded vaccine supplies, a global plan for vaccine distribution was outpaced by bilateral agreements between countries and vaccine manufacturers.

In Gambia, that meant a vaccination program launched with buoyant hope ground to a halt. Months passed without a second shipment of doses. Subsequent shipments arrived with little advance notice, often differing from what had been promised, and sometimes on the verge of expiration.

“People were calling us every day, asking when they would receive their second dose,” Dr. Bittaye says. “We simply didn’t know.”

The debilitating uncertainty and disappointment Gambia experienced have been repeated across much of Africa and in other of the world’s poorest countries.

Initially hailed as the great equalizer in getting the world vaccinated, COVAX has distributed just 5% of the world’s COVID-19 vaccines. One result: Africa has vaccinated only about 6% of a population of about 1.4 billion, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

The world was reminded why that matters when the omicron variant of the coronavirus emerged late last month, apparently originating in South Africa. By Friday, cases of the new strain had been reported in a few dozen countries, including the United States. Uncertainty over the new variant, thought to be highly contagious, tumbled financial markets, and countries imposed travel bans to try to contain its spread.

Omicron’s message

Yet for many global health experts, omicron’s emergence underscores the practical wisdom behind the lofty-sounding vaccine equity that created COVAX. Moreover, they add, it should prompt a rededication to the idea that in a pandemic, helping others is as much about self-preservation as it is about charity.

“We can criticize COVAX, but ultimately they are the world’s proposal for addressing this pandemic, and it was the world that didn’t follow through on taking vaccine equity seriously,” says Richard Marlink, director of Rutgers’ Global Health Institute and an expert on African health systems.

“The point that vaccine equity is not just altruism but is critical for getting out of this pandemic is still the main lesson to be learned,” he adds. “Clearly we haven’t learned it yet.”

Some leaders and international health officials have seized on the emergence of a new coronavirus strain to chide the world on the poor results of the global vaccination campaign.

“The people of Africa cannot be blamed for the immorally low level of vaccinations available to them,” United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres declared in the wake of the omicron discovery.

“We understand and support every government’s responsibility to protect its own people; it’s natural,” said Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO director-general, at a special WHO assembly this week. “But vaccine equity is not charity; it’s in every country’s best interests. No country can vaccinate its way out of the pandemic alone.”

The disconnect between COVAX’s marching orders and the reality of what it would be able to accomplish didn’t take long to materialize, international health experts say.

While the initiative consisting of international institutions including UNICEF and Gavi, the global vaccine alliance, was focused on securing funding for purchasing doses, wealthy countries were negotiating with vaccine manufacturers and buying up months of production that was still only scaling up.

Another setback came when COVAX’s primary supplier, Serum Institute of India, was barred in the spring from exporting vaccine doses.

The export ban was India’s response to a sudden surge in infections following emergence of the virus’s delta variant. But it also bolstered COVAX critics who had warned that relying too much on one manufacturer could be disastrous.

The cutoff of anticipated supplies sent some countries that had signed on to COVAX out to the global market to see what they could find – and afford. What they encountered was disheartening.

“Countries left in the lurch by [India’s] export controls turned either individually or in groups like the African Union to negotiate with manufacturers for supply, but what they encountered was a little bit like the Wild West,” says Katherine Bliss, an expert in health systems resilience at the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Global Health Policy Center in Washington. That survival-of-the-fittest (or wealthiest) environment “did not favor the world’s poorest countries,” she adds.

Cause for some optimism

Still, some experts say they are seeing reasons for cautious optimism about what lies ahead for global vaccine distribution and vaccination rates.

At Gavi, officials point out that COVAX has shipped 223 million doses to Africa, with another 289 million allocated. A half-billion doses would be enough to cover Africa’s frontline workers and the most vulnerable populations, including older people, a Gavi spokesperson says.

Moreover, Gavi contends the global vaccination effort has entered a new phase in which supplies are more plentiful and deliveries more predictable – facilitating planning.

At the same time, diplomatic activity around vaccine delivery has picked up, notes Ms. Bliss. She points to a recent Group of 20 ministerial meeting on COVID-19 vaccine distribution and on-the-ground delivery, and to Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s recent Africa trip, which was largely focused on boosting Africa’s vaccination rates.

Another point of progress that health experts point to is a diversification of vaccine manufacturing. New facilities planned for Africa by big Western vaccine manufacturers will help the continent move away from imports and donations, says Phionah Atuhebwe, a Ugandan doctor and WHO vaccine official based in Brazzaville, Congo.

Indeed, in an emerging environment of increased vaccine availability and improved distribution, some experts say the focus must now shift to overcoming vaccine hesitancy. That tendency already existed in many societies, but has been fed over the pandemic by disappointment and distrust of governments that haven’t delivered on trumpeted vaccination campaigns.

Add to that a proliferation of misinformation and vaccine conspiracy theories on social media, and governments have a new hurdle in the lack of trust they face from some – and a sense among others that the pandemic is already waning.

Rama Sy, who heads up vaccination programs in the Ngor neighborhood of Senegal’s capital, Dakar, says that what is needed now is better messaging to reach reticent members of the public.

“We need to keep raising awareness,” says Ms. Sy, who now has a mix of American, Chinese, and European vaccines to administer. “Now people have heard there’s another variant, there are people coming to get vaccinated,” she says. “But when the cases diminish, they stay home.”

Where the world did better

Dr. Marlink of Rutgers says the failure to live up to the promise of vaccine equity largely explains why the world is only now getting to this point of improving vaccine availability and distribution.

But he says an example exists of how the world has done better at meeting a global public health crisis – and how it can do better at addressing a future pandemic earlier and more equitably.

He points to PEPFAR, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, established by President George W. Bush in 2003. It is now the largest commitment ever by any nation to address a single disease, reaching more than 50 countries.

“There was a lot of discussion and international debate on how to address the AIDS crisis, but it took the United States saying ‘We’re going to go ahead and do this’ for PEPFAR to happen,” Dr. Marlink says. “And it took the U.S. saying ‘We’re going to go ahead and do this using the B word’ – as in the billions of dollars the U.S. committed to it from the beginning,” he adds.

Yet while the U.S. and other wealthy countries may be financially capable of making such a program happen, health experts say it will require a renewed commitment to COVAX’s original stated mission – that ending the pandemic anywhere means ending it everywhere.

The emergence of the omicron variant “is a very telling example of how the virus continues to mutate, particularly in the absence of equitable access” to vaccines, says Candice Sehoma, an advocacy officer for Doctors Without Borders in South Africa. “It underscores why there’s a need for global solidarity and sharing of resources.”

How citizen observers saved Honduran democracy from violence

Confidence in democracy has dipped across Latin America. But a presidential race in Honduras exceeded expectations – thanks to citizen observers – and could boost other democratic movements in the region.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Anna-Catherine Brigida Correspondent

During last weekend’s presidential race in Honduras, voters braced for the worst. Even stores were boarded up, as citizens feared the kind of electoral fraud and furious protest that has marred the voting process in this Central American nation since a 2009 coup. But this week, an opposition candidate who will become Honduras’ first female president won the race, and the ruling party easily conceded. The sounds of fireworks, not bullets, have filled the streets.

It’s a surprising advance for a country ranked one of the four weakest democracies in Latin America just two years ago, according to a study published by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance in Sweden. At a time of worldwide democratic erosion, Hondurans showed this week that citizens, with peaceful protest, can pressure governments to respect the democratic process.

“[The message is that] democracy continues to be an important value for Hondurans,” says Julio Raudales, political analyst and vice rector at the National Autonomous University of Honduras. “And that we want to resolve our conflicts the democratic way and not through violence.”

How citizen observers saved Honduran democracy from violence

The spectators cheered as each vote was counted as if watching a soccer game. But the stakes were much higher than a sports match.

In a worn-down school in a working-class neighborhood in the Honduran capital, dozens clamored during Sunday’s presidential election for no less than the future of Honduran democracy.

They joined citizens across the Central American nation – where democracy has withered since a 2009 coup – who became self-appointed electoral observers for the night. It was an effort to help fend off the kind of fraud that has marred the electoral process in Honduras over the past decade.

And their efforts seem to have paid off. This week Xiomara Castro, candidate for the leftist Libre Party and former first lady whose husband was deposed in the coup, was declared winner and becomes Honduras’s first female president. While stores were boarded up in Tegucigalpa and citizens feared a contested result, her rival Nasry “Tito” Asfura – current Tegucigalpa mayor and member of the ruling National Party – conceded defeat. The celebrations this week have been jubilant, with the sounds of fireworks instead of the tear gas canisters and live bullets that have echoed after races in previous years.

It’s a surprising advance for a country ranked one of the four weakest democracies in Latin America just two years ago, according to a study published by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance in Sweden. At a time of worldwide democratic erosion, Hondurans showed that citizens, with peaceful protest, can pressure governments to respect the democratic process.

“[The message is that] democracy continues to be an important value for Hondurans,” says Julio Raudales, political analyst and vice rector at the National Autonomous University of Honduras. “And that we want to resolve our conflicts the democratic way and not through violence.”

A long night

Pre-election polls gave Ms. Castro a wide lead, driven by Hondurans’ collective frustration with soaring poverty, violence, and corruption under President Juan Orlando Hernández. But her supporters knew victory was far from certain – and mobilized to do their part to safeguard the results.

They turned out early and stayed at voting centers long after the last ballot was cast, forcing the five-person voting boards established inside the classrooms to hold up every ballot for inspection by the crowd, which protested any miscounted vote the same way sports fans heckle a referee who makes a bad call. This citizen observation practice, which allows Hondurans to watch the vote count from a distance so as not to interfere, was eagerly embraced this year in a bid to increase transparency of the electoral system. Some National Party supporters showed up too, but they were far outnumbered by Libre members at the school Sunday.

“We’re observing the process and verifying that the same shameless act that always happens doesn’t happen again,” says Brian Wilson, a 30-something unemployed Honduran at the school Sunday night.

At the top of his mind and that of citizens across the country was the memory of the 2017 race, when the election system mysteriously blacked out while the opposition candidate led, only to have his lead reversed when it came back online. Mr. Hernández was declared winner, and Hondurans flooded the streets in protest. At least 30 were killed in a subsequent crackdown. Mr. Wilson and his fellow self-appointed election monitors braced for the same outcome this time.

But surpassing even their own expectations Sunday, they didn’t have to.

Gustavo Irias, director of the Honduran Center for the Study of Democracy, commended the high voter turnout – 69% – and the decision of many voters to stay for hours to ensure a fair count.

“These youth showed up and determined the results that we have now, which is the overwhelming rejection of the continuity of this regime and a clear desire for change,” Mr. Irias says.

The youth monitors, most under 40, heard about the effort in different ways – from a political party, a friend, or from just seeing the crowd. But they were united in their goal. “What was shown was the desire of the people to save the people,” says Aaron Hernandez, a young truck driver watching the vote tally at the school Sunday.

The push for transparency

Libre party member Neesa Medina attributes the legitimacy of the vote to the opposition party’s maturity process in the decade since its founding in the aftermath of the coup.

In its first two elections, Libre was at a disadvantage because its members were still learning the rules of the political game, long run by the country’s two dominant parties, National and Liberal, she says.

This time, the party better understood the rules, and thus how to ensure fairness, she says. For the first time, Libre earned a seat on the National Electoral Council (CNE), and its representative Rixi Moncada took a lead demanding transparency for the entire cycle. In the lead-up to election day, the party trained members to participate in the electoral counting tables and identify and report irregularities, according to Ms. Medina.

It also went into elections with a clear message to supporters: Vote early, and come back at closing time. “When there is more training and experience, there are fewer chances for fraud or manipulation,” says Ms. Medina.

By 5 a.m. on election day, lines snaked around voting centers. When polls closed, citizens stayed put. “I’ve never seen so much euphoria and participation in elections,” says Fidel Mejia, a vendor watching the votes tallied Sunday.

Still, the day did not pass without some glitches, including polling stations opening late, reports of vote buying, and an attempted cyberattack on CNE servers, according to election observer Carla García, a Honduran activist who was part of an accredited observation mission.

National Party voter Gladys Martínez recognized the election process as transparent but said she would wait until 100% of votes are counted to recognize a winner. “They’ve already proclaimed themselves winners, which isn’t correct,” Ms. Martínez says.

Still, none of these irregularities or disagreement was enough to discredit the results, Ms. García says.

“We can consider the process completely successful, not because a certain person won,” Ms. García says. “But because the people demanded respect and the decision of the people was respected.”

Student loan safety net needs mending: How simplifying can help

Ongoing debate about approaches to student loan forgiveness needn’t be a roadblock to all relief. Better implementation of already existing programs is making a difference for some borrowers right now.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Kelly Field Correspondent

Amid unrelenting pressure from his party’s progressives to provide up to $50,000 per borrower in blanket student loan forgiveness, President Joe Biden has begun canceling the debt of some of those most vulnerable, including thousands of disabled borrowers and victims of for-profit college fraud. All told, the administration has erased more than $12.5 billion in loans owed by more than 650,000 borrowers.

But for every borrower who has had his or her financial slate wiped clean, there are dozens still struggling with unmanageable debt. That $12.5 billion represents less than 1% of the $1.6 trillion in outstanding federal loans.

To address that larger problem, a committee of negotiators is meeting to draft regulations that would extend debt relief to more borrowers in 2023. Meanwhile, the Education Department is taking stopgap measures to make existing loan forgiveness options easier to access.

In August, for example, the agency announced that it would automatically forgive the debt of 323,000 borrowers identified by the Social Security Administration as being permanently disabled, removing a requirement that they submit an application for relief.

Colin Lovvorn, who has been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and is legally blind, was among them.

“I was in disbelief,” says Mr. Lovvorn, who got word in October that his $60,000 in debt would be discharged.

Student loan safety net needs mending: How simplifying can help

This fall, Suzette Kinslow, a mother of three from Indiana, got a letter that would change her life: The federal government, it said, was wiping out $50,000 in debt she’d taken on a decade earlier for a health information technology degree at ITT Technical Institute because of “misrepresentations” by the now-defunct for-profit college chain.

For Ms. Kinslow, who has been unable to find work in the field, the news was both a relief and a vindication. For years, she’d been saying that the school misled her about her job prospects and failed to prepare her for the state certification exam.

But Joseph White, a tech support specialist in Missouri who has made similar claims against the company, is still waiting for relief from the $120,000 he owes for two ITT degrees.

“It’s a huge burden and a huge weight,” Mr. White says of the debt.

Amid unrelenting pressure from his party’s progressives to provide up to $50,000 per borrower in blanket student loan forgiveness, President Joe Biden has begun canceling the debt of some of those most vulnerable, including thousands of disabled borrowers and victims of for-profit college fraud. All told, the administration has erased more than $12.5 billion in loans owed by more than 650,000 borrowers.

The one-off cancellations have delivered desperately needed and long-awaited relief to those like Ms. Kinslow, who can finally refinance her home and co-sign student loans for her two older children, who are now in college themselves.

But such targeted loan forgiveness does little to address long-standing problems with the student loan system. And for those like Mr. White, it can feel unfair, says Persis Yu, policy director and managing counsel at the Student Borrower Protection Center.

“It’s leaving a lot of folks wondering, ‘When is it going to be my turn?’” she adds.

For every borrower who has had his or her financial slate wiped clean, there are dozens still struggling with unmanageable debt. While impressive, the $12.5 billion forgiven thus far by the Biden administration represents less than 1% of the $1.6 trillion in outstanding federal loans.

Is dramatic redress the answer?

Some borrower advocates say the only just approach is to cancel everyone’s debt.

“Trying to draw a line between ‘worthy’ and ‘unworthy’ is just arbitrary and cruel,” says Thomas Gokey, co-founder of the Debt Collective. “Nobody should be forced into debt for an education, and Biden can cancel all this debt with a signature.”

On the other side, those opposed to universal loan forgiveness argue, in part, that it would benefit some wealthy borrowers capable of repaying their loans, while providing no help to those who never attended college, possibly because they couldn’t afford to.

President Biden, who campaigned on canceling $10,000 in debt per borrower, has yet to do so and has said he doesn’t think he has authority to unilaterally cancel more than that. Instead, he has taken a focused approach to loan forgiveness, while extending a pause on repayment and interest accumulation put in place by his predecessor at the start of the pandemic.

But both sides of the debt relief debate agree on one thing: The student loan safety net is badly torn, and in dire need of mending.

To that end, the Biden administration has begun rewriting the rules that govern federal loan forgiveness programs, with the aim of making them simpler, fairer, and more generous.

Making the current system more user-friendly

Under existing law, certain borrowers already have access to assistance:

- Those who are displaced by abrupt school closures, defrauded by predatory schools, or permanently disabled and unable to work are entitled to immediate loan cancellation.

- Public servants who make monthly payments on their loans are supposed to have their remaining debt discharged after 10 years.

- Low-income individuals who repay their debt as a percentage of income should have their balance forgiven after 20 to 25 years.

In practice, though, few have received this promised relief. Ninety-eight percent of applications for relief under the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program have been denied, many for paperwork errors. Just 32 borrowers have been granted forgiveness under the oldest income-based plan, which was created by Congress in 1995, even though 4.4 million Americans owe debt that is more than 20 years old. And tens of thousands of borrowers who attended now-shuttered for-profit colleges have been waiting years for relief.

Former President Barack Obama tried to make it easier for those who attended shoddy for-profit schools to qualify for debt relief, issuing a series of regulations and policy changes that were subsequently rewritten or repealed by the Trump administration.

When Mr. Biden took office in January, he pledged to restore the Obama-era rules and fix the public service and income-based repayment programs, which advocates say have been chronically mismanaged by the federal Department of Education and its student loan servicers. This fall, a committee of negotiators is meeting to draft regulations that would extend debt relief to many more borrowers. The new rules are set to take effect in the summer of 2023.

Extending forgiveness more broadly

In the meantime, the Education Department is taking stopgap measures to expand student loan forgiveness. Since March, it has discharged the loans of more than 200,000 borrowers who attended for-profit colleges, including ITT Technical Institute.

In August, the agency announced that it would automatically forgive the debt of 323,000 borrowers identified by the Social Security Administration as being permanently disabled, removing a requirement that they submit an application for relief.

Colin Lovvorn, who has been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis and is legally blind, was among them.

“I was in disbelief,” says Mr. Lovvorn, who got word in October that his $60,000 in debt would be discharged. “My mental stress is going to be down so much, I’m probably less likely to have an MS-related relapse.”

Then, in October, the Education Department announced that it would temporarily allow all prior payments made by public servants to count toward the 10-year repayment requirement, not just payments made on time and in full on government-issued loans. The yearlong waiver, which expires next Halloween, was expected to put a half-million borrowers closer to forgiveness and result in at least 22,000 borrowers receiving immediate forgiveness.

Ms. Yu and other borrower advocates are asking the administration to apply these same principles – automation and retroactivity – to the other loan forgiveness programs.

“We want a shorter, easier pathway to forgiveness and relief for those left behind” by restrictive eligibility criteria and changing rules, she says.

What’s the right balance?

But advocates haven’t given up on wholesale debt relief, and point to pitfalls in the president’s piecemeal approach.

“It’s incredibly confusing for our clients,” says Robyn Smith, an attorney with the Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles. “They see the stories [in the media] and don’t know if it’s them or not.”

Mike Pierce, executive director and co-founder of the Student Borrower Protection Center, says the president’s moves carry political peril, too. Though Mr. Pierce welcomed the expansion of forgiveness, he’s worried it will “be overshadowed because they’re not delivering on big-ticket debt cancellation.”

Even if the administration ultimately cancels more dollars in debt than if it had forgiven $10,000 outright per borrower, “the perception is still there that he didn’t do what he promised,” Mr. Pierce says.

Many advocates are anticipating a rocky return to student loan repayment on Jan. 31, when the nearly two-year pause is set to expire – especially since several student loan servicers have stopped participating in recent months.

Wiping out debt now could be “an elegant solution” to the looming administrative nightmare, suggests Mr. Pierce.

Nicole Brun-Cottan, a physical therapist in Oregon with $130,000 in graduate school debt, has another, perhaps simpler solution to the problem of unmanageable debt: lower interest rates. Current rates range from 3.73% for undergraduate loans to 6.28% for some grad student and parent loans.

“Lump-sum forgiveness is a great idea, but I don’t know if there is the political will,” says Ms. Brun-Cottan, who is enrolled in the public service loan repayment program. “But dropping interest rates into a not-usurious range is a completely reasonable thing to do.”

Listen

Sowing peace, science knowledge, and empowerment with seeds and a trowel

Heather Oakley Rippy founded Global Gardens in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in order to nurture children – to teach them about cooperation, critical thinking, confidence, and hope. Episode 3 of our “People Making a Difference” podcast.

Planting radishes is really a means to learning self-control and critical thinking. That’s how Heather Oakley Rippy sees it.

The founder of Global Gardens started a program in 2007 that now reaches children in pre-K to sixth grade at 15 schools in Tulsa, Oklahoma. It also operates three community gardens. But what’s compelling about the Global Gardens approach is that its facilitators are sowing critical life skills in today’s racially and politically polarized world. The three core values underlying their efforts are science, peace, and empowerment.

Whenever kids are working on a project together, “you’re going to have some conflict,” says Ms. Rippy. But she adds that if you are “teaching critical thinking, asking questions, working together in a peaceful way, working out conflicts, kids are going to be naturally empowered.” – Dave Scott, audience engagement editor

This story was sparked by a Monitor story about U.S. summer school programs that included a quote from Jenni Yoder with Global Gardens in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

This audio story was meant to be listened to, but we understand that is not an option for everyone. For a transcript, you can click here.

Global Gardens: Raising confident children

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why young Saudis may reshape the Muslim world

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Like the proverbial hand that rocks the cradle, school textbooks still have a big influence on a country’s next generation, despite the growing power of social media. And perhaps no country has made such a swift change in its textbooks over the past few years than Saudi Arabia, the center of the Islamic world.

The shift by the Saudi Ministry of Education away from teaching hate and fear of others – especially Jews and Christians – has been so dramatic that a new study of the latest textbooks claims a change in Saudi attitudes “could produce a ripple effect in other Muslim majority countries.”

“The Saudi educational curriculum appears to be sailing on an even keel toward its stated goals of more moderation and openness,” states the Institute for Monitoring Peace and Cultural Tolerance in School Education, an Israeli research group.

“We believe that Saudi Arabia is seeking a place in a region that hopes to resemble a family of sharing and cooperating nations,” the study concludes.

Why young Saudis may reshape the Muslim world

Like the proverbial hand that rocks the cradle, school textbooks still have a big influence on a country’s next generation, despite the growing power of social media. And perhaps no country has made such a swift change in its textbooks over the past few years than Saudi Arabia, the center of the Islamic world.

The shift by the Saudi Ministry of Education away from teaching hate and fear of others – especially Jews and Christians – has been so dramatic that a new study of the latest textbooks claims a change in Saudi attitudes “could produce a ripple effect in other Muslim majority countries.”

“The Saudi educational curriculum appears to be sailing on an even keel toward its stated goals of more moderation and openness,” states the Institute for Monitoring Peace and Cultural Tolerance in School Education (Impact-se), an Israeli research group. Just since 2020, at least 22 anti-Christian and antisemitic lessons were either removed from or altered in the textbooks while an entire textbook unit on violent jihad to spread Islam was removed.

“We believe that Saudi Arabia is seeking a place in a region that hopes to resemble a family of sharing and cooperating nations,” the Impact-se study concludes.

While the study cites the need for further changes in textbooks, it points out that a national vision for transforming the Saudi economy, laid out in 2016 by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, requires a change to prevailing ideas, not just industries.

For decades, the country’s social and educational outlook was controlled by Muslim clerics preaching a fundamentalist version of Islam known as Wahhabism. After the attacks of 9/11 by mainly Saudi terrorists, the United States and others drew sharp attention to the hate-filled radicalism of Saudi textbooks.

But the real motive for change may be the need to allow a free flow of ideas among students and to encourage critical thinking in order to create an economy based on technological innovation, rather than oil exports. While Saudi Arabia is far from being a democracy, it feels pressure from young people to modernize. Nearly two-thirds of Saudis are under the age of 35.

As the Impact-se report states, “Rigidity and hate for the other will not serve to unlock the potential of a nation, while respect for others is key to prosperity and security.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Be a good Samaritan

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Susan Tish

Looking to God, divine Love, to guide us, we can find practical ways to be “good Samaritans” in helping individuals and our cities thrive.

Be a good Samaritan

My husband and I were walking down the beautiful new RiverWalk in our city of Detroit. The area used to be considered unsafe, so we were pleasantly in awe of this now vibrant and well-tended public walkway.

Soon we came upon a group of young girls playing and haphazardly kicking rocks onto the pathway. A jogger stopped to kindly ask them not to do that, explaining that there were many bikers and runners using the path, and someone could get hurt if they ran into a rock. The girls quickly apologized and began helping him clear the path. Here, I thought, were some good Samaritans!

The parable of the good Samaritan comes from the Bible, but its message still resonates as a call to civic responsibility today. In the biblical account, Christ Jesus discusses with “a certain lawyer” how the two most important commandments are to “love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy strength, and with all thy mind; and thy neighbour as thyself” (see Luke 10:25-37). To illustrate who qualifies as a neighbor, Jesus proceeds to tell this parable.

In short, a man traveling on foot had been attacked and left to die by the side of the road. Individually, a couple of passersby avoided helping him by crossing to the other side of the road. But a man from Samaria stopped to help him. He bandaged his wounds and brought him to an inn to rest.

When issues arise, it can be tempting to believe that it’s someone else’s problem – much like the actions of those who “passed by on the other side” indicated. And when the problem concerns the decline of our major cities, it can be tempting to blame institutions such as the local government or the police, or even attribute it to the global pandemic.

Christ Jesus’ parable, however, illustrates that we are all neighbors, all interconnected and reliant on each other. It is everyone’s concern to love and care for our fellow citizens and for the surroundings in which we live. God, who is divine Love, freely gives to all. So, as His children, we naturally possess this same ability to unhesitatingly care for each other.

This impartial Love and its very practical help is at the heart of the global church established by Mary Baker Eddy, who also founded this news organization. As she explains in her book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “Love inspires, illumines, designates, and leads the way. Right motives give pinions to thought, and strength and freedom to speech and action” (p. 454). This impactful Love works in each of us and is available to heal the wounds of one person or an entire city.

A few years ago I was frustrated by the state of decline in Detroit, and inwardly I blamed our lagging inner-city schools. For years I had thought of becoming a mentor to a student but had kept putting it off, feeling as though my time could be better served praying for the whole community rather than just helping one student. Nevertheless, continuing to feel impelled to help, I finally signed up with a program to mentor a middle school girl from an impoverished neighborhood.

One month later, the pandemic closed our schools, leaving many inner-city children behind as they lacked the resources or support at home to keep up with online school. But this student and I kept in touch regularly so we were able to discern her practical needs. At first, she felt discouraged and alone. But, trusting divine Love to guide both of us, I was able to encourage her with the knowledge that she was very cared for and always had a place to turn for help.

This student eventually thrived during the shutdown, bringing up her grades and earning admittance into the best high school in the city. Divine Love had inspired and led the way to meet her needs. Deciding not to “pass” on this spiritual impulse to love my neighbor confirmed for me the power of every individual expression of God’s infinite and inevitably healing love.

Now, a few young people moving rocks off the sidewalk or an adult mentoring a young student may not alone be the solution to the challenges facing Detroit or any other city. But each such act is an indication of Love operating in human consciousness and practically meeting individual needs. Instead of lamenting the challenges, we can daily celebrate, in each city, every evidence of God’s loving and healing action.

A message of love

Perched

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us. Please come back Monday, when we look at the return of monarch butterflies to California, after a stark showing last year.