- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Kelly Slater, an ageless surfing legend, records another historic victory

Understandably, in the world of sports, all eyes are focused on the Beijing Winter Olympics. But let’s spare a moment for the GOAT.

No, not Tom Brady, the NFL’s Greatest Of All Time. But the GOAT of surfing.

On Saturday, Kelly Slater made history by winning the Billabong Pro Pipeline surfing competition for the eighth time in 30 years. In 1992, he was the youngest master of the Pipeline. In 2011, at age 39, he was the oldest to conquer Oahu’s North Shore. And now, just six days shy of his 50th birthday, Mr. Slater did it again.

The native Floridian epitomizes fearless grace on a roaring wall of water, defying limits and consistently defining excellence. He’s won 11 world championships and 56 professional tour events. He’s the Tom Brady of the big breakers.

In fact, his latest Pipeline victory felt a little like last year’s Super Bowl, when razor-sharp wisdom (Mr. Brady, age 43) defeated youthful verve (QB Patrick Mahomes, age 25). In an early Pipeline heat, it looked like Mr. Slater might get knocked out of the competition by 22-year-old Barron Mamiya. He had only seconds left to catch one last ride. Yet, he waited. At the last possible moment, he caught the perfect wave. “I kind of think of it like a martial art,” Mr. Slater told the Associated Press. “You don’t get worse as you get older, you get more experienced.”

Like Mr. Brady, who retired last week, Mr. Slater is dogged by questions about his future. But his response suggests he’s not done. “Everyone who retires from surfing just goes surfing,” he said with a smile.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Rising book bans: Grounds for moral panic?

The latest battles over what books are best for children appear to be mostly shaped by larger political fissures over freedom of speech, equality, identity, and moral standards. Our reporter looks at how some librarians are navigating this terrain.

-

By Lee Lawrence Correspondent

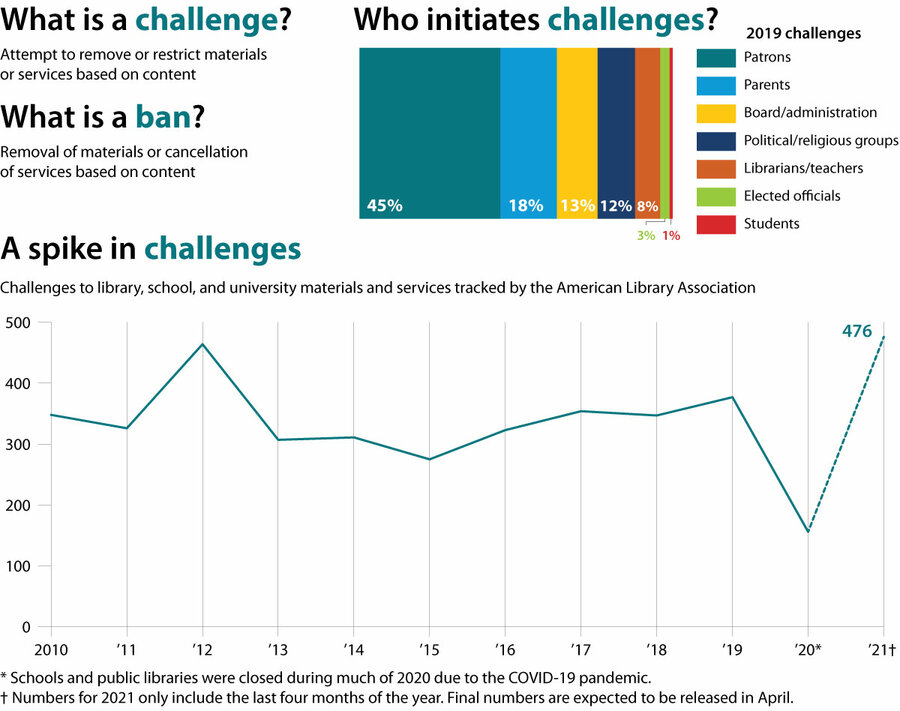

Challenges to books in schools and public libraries are growing exponentially, and the final tally for 2021 is expected to be by far the highest in a decade, reports Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom.

Though the full year has not been tallied, there were roughly 476 challenges between September and the end of 2021, compared with 370 total in 2019, the last year schools and libraries were fully open before the pandemic.

Debates over everything from the graphic novel depiction of the Holocaust in “Maus” to listings in the high school canon, such as the “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” play out in the news and on social media as an us vs. them battle that makes little room for thoughtful discussion.

In this increasingly polarized context, says Emily Knox, author of “Book Banning in 21st-Century America,” “The books are kind of incidental. What we’re really arguing about is, what does it mean to be a citizen of the United States? How do we want our children to be educated? What do we want to say about our history?”

Rising book bans: Grounds for moral panic?

Whether it’s the depiction in “Maus” of the Holocaust, the discussion about puberty in “It’s Perfectly Normal,” the LGBTQ perspective presented in “Gender Queer: A Memoir,” or the presence of “The Bluest Eye” and “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” in the high school canon, books in schools and libraries nationwide increasingly have targets on their spines.

Experts say the challenges – fanned by the heated online “outrage ecosystem” – are growing exponentially. Last year, reports the American Library Association, brought the highest number of reported book challenges it has tallied in a decade.

Though the full year has not been finalized, there were roughly 476 challenges between September and the end of 2021, compared with 377 total in 2019, the last year schools and libraries were fully open before the pandemic, says Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom.

However, caution library scholars, clashes over books, not deliberative conversations make the news. But that doesn’t mean those conversations aren’t taking place in communities across the nation, with challenges resolved or compromises forged before they erupt in acrimonious headlines.

Ten years ago, challenges “were very local,” says Ms. Caldwell-Stone. What happened in one school district did not significantly affect what happened elsewhere. Today, with activists exchanging tactics and information online, challenges are popping up everywhere.

In this increasingly polarized context, says Emily Knox, associate professor in the School of Information Sciences at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and author of “Book Banning in 21st-Century America,” “The books are kind of incidental. What we’re really arguing about is, what does it mean to be a citizen of the United States? How do we want our children to be educated? What do we want to say about our history?”

Book “banning” in the U.S. almost always plays out in the public sector and particularly where children are involved. School curricula, school libraries, and the children’s sections of public libraries have become “contested because we’re trying to figure out what the values of the next generation should be,” Ms. Knox says.

But that is not what the public debate focuses on. As it plays out in the news and on social media, it is an us vs. them battle that makes little room for thoughtful discussion. The more tempers rise and the more partisan the battle has become, the more it manifests as a power struggle rather than an effort to find common ground on how best to serve children.

There are several contributing factors. Sometimes, people argue at cross-purposes because they don’t realize different rules apply to books in a curriculum, in a school library, or in a public library.

For example, when the McMinn County School Board in Tennessee drew international attention when it voted unanimously Jan. 10 to remove “Maus” from its eighth-grade social studies curriculum, it was not removed from school libraries, reports the local Daily Post Athenian.

Books taught in classes are required reading. Since school districts establish curricula, they can determine whether a book should or should not be taught. They evaluate it for age-appropriateness and pedagogical soundness.

Books in school libraries, on the other hand, are not required reading. They are there to support the curriculum but also to fuel a love of reading, address issues of concern to students, and offer a range of perspectives. If it is found to be erroneous, pornographic, or shown not to be age-appropriate, for example, it can be removed.

But in the 1982 landmark case of Island Trees School District v. Pico, the United States Supreme Court ruled that to remove a book based on its ideas and content alone violates students’ First Amendment right to read and be informed. This would apply, for example, to objections to a novel’s depiction of instances of racism or aspects of the LGBTQ experience.

The bar for removal is still higher for public libraries. They serve the community in all its diversity, from age and sexual orientation to ethnicity, race, and political affiliation. In the eyes of the Supreme Court, a public library is a “limited public forum” and “the quintessential locus of the receipt of information.”

This very diversity helps explain why more than half of all book challenges are levied at public libraries, often by “parents wanting to protect their children,” says Paula Laurita, who was executive director of the Athens-Limestone Public Library in Alabama from 2010 to 2020 and has had a long tenure as the ALA’s Alabama chapter councilor. “So what may be acceptable to one family is not acceptable to another family,” she says.

In many cases, parents object to, say, a Gay Pride month display being too close to the children’s section, says April Dawkins, assistant professor in library and information science at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Depending on the library, it might get moved, dismantled, or kept and followed later by a display of, say, conservative authors.

Listening for the success stories

Even when a challenge results in the removal of a book from a public school or library, however, it remains accessible. Other district libraries have it. Bookstores and websites openly sell it. The book is featured during Banned Books Week, the ALA’s “annual celebration of the freedom to read” which features book sales, author’s talks, panel discussions, and displays in bookstores and libraries across the country.

“So, the book isn’t banned, it’s censored,” says Elliott Kuecker, a faculty librarian and researcher at the University of Georgia and author of “Questioning the Dogma of Banned Books Week,” a study published in the journal Library Philosophy and Practice.

When he wrote this in 2018, he says, “my concern was that they were setting up kind of a friend-enemy relationship” because the very word – banning – conjures the image of an attack on democracy. It sets up librarians as heroes fighting off that attack when what they are facing is nothing like the book burnings during the Third Reich or all-out bans imposed by regimes like the Taliban.

Opting for a more accurate description, he thinks, would lead to more productive conversations.

“The ‘censorship’ of an individual book,” says Mr. Kuecker, “is more someone expressing a problem with the morality of a text.” This, he adds, might lead people to talk about what it means “to read an amoral text? Can a text contain morality and ethics, or is it the reader who interprets for that?”

This “friend-enemy” dynamic preempts other conversations as well. For example, Ms. Caldwell-Stone points to the underlying concern of challenges as being “what are young people reading about? What are they absorbing through the words they’re exposed to?”

But, judging from reports of book challenges, the public debate seldom if ever delves into how children process difficult material or whether “young readers are able to discern what the reading [is about] and to make good judgments about it,” as Ms. Caldwell-Stone maintains. Nor is the question of how educators and parents can best guide children examined much in the debates.

Instead, people choose sides over who is better suited to control what children read: parents who know their child intimately or educators who are trained professionals? One side champions greater parental rights, the other counters with students’ First Amendment rights.

And the compromise that many educators and librarians suggest seems to get lost.

American Library Association

“We don’t often hear [about] the really, really thoughtful and successful stories,” Kristin Pekoll, assistant director of the ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom told librarians during a recent webinar. “That’s because librarians addressed it according to their policies and they’ve had really great conversations with their communities about the resources, and maybe things were deescalated and handled as conversations informally,” she says.

“I believe any parent should be able to say ‘I don’t want my child reading a particular book.’ That’s completely fine,” says Danielle Hartsfield, assistant professor at the University of North Georgia who has written about educators and controversial literature. But parents lack the professional training and knowledge of teachers and librarians to “collectively say ‘no child should read this book.’”

Ms. Knox, as most librarians, prizes the free flow of information, but she understands how fraught this can be.

Efforts to censor what children read “are really demonstrating to us why reading is fundamental. We say things like critical thinking and that kind of thing but, actually, reading changes who you are as a person,” Ms. Knox says.

“Libraries are not labyrinths to truths; they’re gardens of truth,” she says. In online explorations, algorithms progressively channel searches. Libraries, by contrast, are “organized chaos,” says Ms. Knox, where 19th-century Jane Austen sits next to post-modern Paul Auster. “You pick up something here and you pick up something there – that, in fact, makes a library a very dangerous space, because it’s true that your children will stumble upon something that does not necessarily reflect your values.”

And mechanisms exist that can help people talk about how best to help children navigate that space and thrive: detailed and transparent procedures to review whether a particular book belongs in the curriculum or library. This involves a multi-step process beginning with an informal conversation with a teacher or librarian on up through a written complaint based on a reading of the text and ending in a school board or board of trustees meeting.

Did they read the book?

Yet the atmosphere is so charged, the procedures are sometimes bypassed.

Ms. Caldwell-Stone is seeing “school districts that have policies for reconsideration ignoring the policies and removing books from the school library.”

At the same time, Ms. Dawkins reports that complainants “are not receptive to conversation.” Rather than follow the steps, they jump “to the school board and public fora and use inflammatory language” that provokes outrage. “The other thing that happens is [complainants] not willing to read the book in its entirety to see what the merits are,” she says.

The inaccuracies in the challenge of 31 books on the English Language Arts curriculum of the Williamson County School District in Tennessee illustrate Ms. Dawkins’ claim.

“The Story of Ruby Bridges” is, for example, described as containing the n-word and portraying all white people as angry. In fact, no racial slur is in the text and some of the white characters were supportive of Ruby.

The reconsideration process took six months, during which representatives of parents, teachers, and school board officials read the books and met with complainants. They agreed to remove one book because the curriculum did not allow time enough for it to be properly taught.

The local chapter of Moms for Liberty, an advocacy group that started in opposition to mask mandates in schools and has grown explosively into what it says is a 60,000-plus member force across 33 states, has filed an appeal.

It is impossible to know whether the concerns of these complainants could be assuaged through dialogue. But certainly others’ have.

A case resolved before eruption of headlines

Ms. Laurita used to tell her library staff, “when people come up and start complaining about a book, the first thing to do is take a breath. Don’t get defensive, and listen, because sometimes they just need to hear that their concerns are understood.”

When graphic novels first came out, a patron asked Ms. Laurita to rid the collection of some because of the sexualized way they portrayed women superheroes. So Ms. Laurita showed her that they hadn’t grouped all graphic novels together, but placed each one with books appropriate for readers of the same age.

As a result, she says, “There was no formal challenge; it was a discussion.”

Ms. Dawkins recalls a similar situation when she worked in a high school library in rural North Carolina. A teacher objected to the inclusion of “Boy Meets Boy” in a display of new acquisitions.

“So it became a conversation,” she says. The teacher didn’t see the need for the book because he thought the school had no gay students.

“Oh,” Ms. Dawkins recalls saying, “I went to this high school and I assure you, there were gay students here. They might not have been open about it, but they are now, as alumni.”

The conversation broadened to Ms. Dawkins feeling strongly about having books that spoke to the Muslim and Jewish students, as part of the library’s mission of speaking to and about all students.

According to the ALA, a small percentage of books are challenged by administrators and faculty. But this teacher was not among them.

Nobody called a reporter. Nobody doled out an Intellectual Freedom award.

American Library Association

As US battles ISIS, many in Syria take their cue from Afghanistan

A recent raid that killed an ISIS leader may appear to be progress against terrorists, as U.S. officials said. But our reporter looks at why there’s little trust or confidence among Syrians in continued Western support.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Three years after the fall of its self-declared caliphate, the Islamic State has evolved from a military group into a decentralized insurgency. Which means, say analysts, that even U.S. operations like the raid in Syria that led to the death of the jihadist leader do not herald the end of the fight against ISIS.

“No one quite wants to acknowledge that the fight against ISIS in Iraq and in Syria in particular just isn’t finished yet,” says Charles Lister, a Middle East Institute expert.

Key to the battle in Syria is the Syrian Democratic Forces, which faces internal and external stresses as it seeks support for its long fight. For local Syrians trying to navigate between the Western-backed SDF and the largely homegrown insurgency, the U.S. raid did not alleviate their doubts about the anti-ISIS coalition.

In particular, the question of American dependability looms large following the chaotic Afghanistan withdrawal last summer. Analysts say Syrians became convinced Americans will leave Syria without warning, and that therefore the SDF faces collapse.

People “don’t want to jeopardize themselves by cooperating ... with an SDF many see as a fleeting entity,” says Dareen Khalifa, an International Crisis Group analyst. “We are seeing people in eastern Syria hedging their bets, and this offers leeway for ISIS to operate in these areas.”

As US battles ISIS, many in Syria take their cue from Afghanistan

The Biden administration touted the high-profile U.S. raid that led to the death of ISIS leader Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurayshi in northern Syria last week as sending “a strong message to terrorists around the world.” But for many outside Syria, it was a rare reminder that the fight against the Islamic State was, in fact, not over.

Three years after its territorial defeat, with the fall of its self-declared caliphate, ISIS has evolved from a military group into a decentralized insurgency operating on the fringes of Syria and Iraq. That has left the U.S.-led, global anti-ISIS coalition and its local partners adapting – often on the fly – to pursue a mission with no end date in sight.

“No one quite wants to acknowledge that the fight against ISIS in Iraq and in Syria in particular just isn’t finished yet,” says Charles Lister, director of the Middle East Institute’s Syria and Countering Terrorism & Extremism programs.

“The killing of Qurayshi might have lulled people into a sense of security that everything is under control and that the campaign is moving in the right direction, but that would be misplaced.”

Despite the United States declaring victory after the fall of the “caliphate” in northern Syria in 2019, ISIS retains a presence in eastern Syria and western Iraq. Its affiliates, meanwhile, also are carrying out devastating attacks in Taliban-led Afghanistan, and they control territory in West Africa, in Nigeria and Mali.

It might be a far cry from the organization that ran a Britain-sized “state” in Syria and Iraq from 2014-18, but experts and military officials say ISIS is now a cost-effective, off-the-radar movement quietly rebuilding its manpower and financial resources in the shadows, willing to strike when the right opportunity arises.

One such opportunity arose in late January when ISIS forces attacked the al-Sinaa prison in Hassakeh, in northeastern Syria, a makeshift detention facility where predominately Kurdish forces were holding some 4,000 ISIS fighters at the behest of the U.S.-led coalition.

After a weeklong operation, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) repelled the ISIS siege, thanks to the intervention of U.S. Special Operations forces. Around 300 ISIS fighters are estimated to have escaped.

Afghanistan’s shadow

The Biden administration highlighted last Thursday’s raid against Mr. Qurayshi as a decisive response to the prison break. But for local Syrians trying to navigate between the Western-backed SDF and the persistent, largely homegrown ISIS insurgency, the raid was not sufficient to alleviate their doubts about the global coalition: whether it can sustain anti-ISIS operations while countries turn their attentions elsewhere and cut back their resources and presence on the ground.

In particular, the shadow of Afghanistan and the question of American dependability loom large in Syria, making U.S. support the SDF’s Achilles’ heel.

In the wake of the chaotic U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan last summer, analysts say, Syrians became convinced Americans will leave Syria suddenly, without warning, and that therefore the SDF is an entity facing an inevitable collapse.

“Should the Americans move to withdraw from Syria, the SDF will collapse quicker than the Ashraf Ghani government in Afghanistan, and ISIS will be ready,” says Hasssan Abu Haniya, a Jordanian expert on jihadist movements.

With this in mind, and in order to live another day, many local communities in eastern Syria are pursuing a strategy of lying low and acquiescing to extortionist ISIS demands for so-called protection money, rather than cooperate with the SDF.

“People in eastern Syria fear collective punishment, and they don’t want to jeopardize themselves by cooperating on counter-ISIS raids with an SDF many see as a fleeting entity,” says Dareen Khalifa, senior Syria analyst for the International Crisis Group.

“They are worried [that] if they cooperate and the SDF withdraws or the Americans leave, either the Assad regime will retaliate against them or ISIS will retaliate. We are seeing people in eastern Syria hedging their bets, and this offers leeway for ISIS to operate in these areas.”

U.S. deployment

There are currently 700 U.S. troops in northeast Syria and 200 in southeast Syria near the Syrian-Jordanian border, the Pentagon said last October, down from a publicly disclosed high of 2,000 in 2018. There is also a small contingent of British special forces.

Since ISIS’s territorial defeat, the Americans and British have supported the SDF and are widely seen by analysts and policymakers as a low-cost, minimal military footprint that has prevented power vacuums and conflicts that could facilitate the terror group’s resurgence.

The military campaign to oust ISIS from towns and villages in 2014-19 required international manpower and investment, but was a straightforward military operation with clear objectives.

“But in this new environment the enemy is hidden, the objectives are completely gray, so in that sense, can we rely so heavily on a poorly resourced actor like the SDF for intelligence gathering and strategic planning with minimal assistance from international forces?” Mr. Lister says.

And as for the death of Mr. Qurayshi, analysts say it was an important setback, but by no means a game changer.

Much like in 2010, when what was then known as Al Qaeda in Iraq was driven into the desert by U.S.-supported Sunni tribesmen, ISIS is capable of producing new leaders while maintaining its loosely connected, localized networks intact, like a self-regenerating terrorist hydra.

“In the past we saw the assassination of Zarqawi, Baghdadi, and now” Mr. Qurayshi, “and each time other people stepped in to lead this movement into a new era,” says Mr. Abu Haniya, the Jordanian analyst.

“The assassination of leadership figures will not affect ISIS’s activities in West Africa, Afghanistan, or even Syria. In its current form, this is a decentralized movement; you can keep cutting off the head and the body will keep on living.”

As part of its evolving mission, the global coalition has also sought to tackle the Islamic State’s “financing and economic infrastructure.”

It has proved a difficult task.

According to experts, when it retreated underground, ISIS had between $150 million and $300 million in reserves, which it allegedly has invested in small and medium economic enterprises through intermediaries.

Among its reported investments are small commercial outlets and shops in eastern Syria and western Iraq handling a large number of small cash transactions not easily tracked by the global coalition.

Another revenue stream is believed to be its extortion racket, demanding money and taxes from businesses and communities in eastern Syria and western Iraq for “protection” from violence, and from truck drivers for safe passage.

“For these jihadist groups, the desert borders are like the sea, and they are the captains of these ships; they know how to navigate them much better than the forces that are protecting them,” says Rasha Al Aqeedi, senior analyst at the New Lines Institute for Strategy and Policy, a Washington think tank.

SDF weaknesses

Perhaps the most critical part of the fight against ISIS has been the U.S.-led coalition’s local partners.

The SDF, a multiethnic coalition of Kurdish, Christian, and Arab fighters formed in 2015 with U.S. support, today polices and administers former ISIS-held lands in Syria including Raqqa, Deir ez-Zour, and Hassakeh, in territory encompassing Syria’s oil- and gas-rich areas.

Yet in recent years, as the economic and humanitarian situation in northern and eastern Syria worsened, attitudes toward the SDF have soured.

Its own employees have expressed resentment over the Kurdish PKK’s dominance of leadership positions and resources within the SDF, accusing it of discrimination. Sporadic, violent local protests have erupted against its rule in the past year.

And as the SDF branched out to control more territory, it has found itself administering Arab communities in which it is a stranger, finding itself unable to perform wide counterterrorism sweeps or intelligence operations.

It also remains entirely reliant on the presence of U.S. troops near Hassakeh. The SDF needs the Hassakeh region’s natural resources such as oil, gas, and wheat as a revenue stream to pay its troops and Arab and Kurdish employees.

Observers caution that although ISIS is not set to reemerge like 2014, it will continue opportunistic attacks as it regroups, though at a level unlikely to trigger enhanced international support for the SDF.

“These attacks may continue to happen, but unfortunately they are not big enough for the global coalition to take extra steps,” Ms. Al Aqeedi says, “and Iraq and Syrian security personnel and civilians are the victims.”

Patterns

The best COVID-19 buster? Trust.

Recent studies show trust in government is key to effectively fighting the pandemic. But when trust falters, how can it be rebuilt? Our London columnist finds some answers.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

It is clear that some countries have done a lot better than others when it comes to dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, limiting infection rates and the number of lives lost. But two studies just published come to a surprising conclusion: Success has depended less on things like health care infrastructure or type of government, than it has on an intangible – trust.

Nations with high levels of trust among citizens, and especially of trust in government, have done best, the studies find.

That’s good news for them, but not so good for countries where trust in government is low, such as the United States and Britain. As British and U.S. authorities end restrictions, they will be trying to convince their citizens that mandates might be going away but the coronavirus isn’t, so people need to behave carefully.

That will take credible leadership, where credibility is in short supply.

But there are signs of hope. The government in Taiwan, where trust was near rock bottom only a few years ago, has rebuilt it with deliberate efforts. And more broadly, interpersonal trust has proved more resilient than trust in government. That may be a good place to start strengthening society’s confidence.

The best COVID-19 buster? Trust.

It’s still much too early to say the COVID-19 pandemic is over. But it’s not too early to look for lessons from the successes – and failures – that governments around the globe experienced as they tried to meet its challenge.

And it’s becoming ever clearer that a key factor distinguishing those who’ve succeeded from those who failed is a single, five-letter word: trust.

Communal trust is part of it – how individuals and communities connect with, and care for, one another. But what has turned out to matter even more is the trust – or lack of it – that citizens have in their own governments.

Governments that have managed to limit the number of COVID-19 cases, and of lives lost – ranging from democracies like New Zealand and Denmark to Communist-ruled Vietnam – tend to score highly on the trust barometer.

But even there, trust in government has been eroding as the pandemic trundles on. And the problem is magnified in places where trust in government was already low, such as the United States and Britain, which have suffered more heavily from the pandemic.

They are now loosening restrictions and seeking to balance the economic and social benefits of “opening up” with widespread public acceptance of some continuing precautions so as to create a sustainable “new normal.”

Governments will be seeking to drive home the message that mandated restrictions might be going away, but the coronavirus isn’t, so citizens should behave carefully. The question is whether those citizens will trust the messengers enough to follow their advice.

And the issue of trust in government – how to keep it if it’s there, rebuild it if it’s not – will also have wider implications when it comes to securing consensus around other national challenges, or international ones such as climate change.

Since the pandemic began, the significance of trust in government has been clear. It has been a recurring theme of this column, singling out not just New Zealand but other early success stories, like the island democracy of Taiwan.

But two major studies in recent weeks have dramatically underscored its importance.

The larger one, led by Thomas Bollyky, senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, and Erin Hulland of the University of Washington, drew on polling data from 177 countries, placed alongside the numbers of infections and lives lost in each country.

It found that previously assumed factors influencing “pandemic preparedness,” such as the nature of a country’s government or its health care infrastructure, paled beside “trust.”

The other study was by Alexander Bor and two colleagues at Denmark’s Aarhus University and surveyed Denmark, Hungary, Italy, and the United States. It explicitly focused on trust – both the trust people extend to one another, and trust in government.

And while it found that interpersonal trust had proved remarkably resilient during the pandemic, the state of trust in government was less encouraging. It had “markedly decreased” in all four countries.

That poses an important short-term challenge. Last week, one of the Aarhus report’s co-authors, Michael Bang Petersen, warned in The New York Times that even though “public trust has taken a hit,” it was now imperative for governments to provide “strong leadership” and bring people together in a “shared view” of the kind of choices and precautions most likely to bring the pandemic to an end.

But a number of democracies, including the U.S., face a tougher, longer-term difficulty: How to rebuild trust in government where it had been badly battered long before the pandemic.

The Pew Research Center’s measure of trust in the U.S. federal government has charted a steep decline since the late 1950s, when roughly three-quarters of Americans said they trusted Washington to do the right thing. Now, fewer than one-quarter say the government will do what is right “most of the time.” Just 2% say it will do so “just about always.”

A similar trend has been evident in Britain since a 1944 Gallup Poll found about one-third of respondents believed their parliamentary representatives were merely “out for themselves.” Now nearly two-thirds feel that’s true. Only 5% say their politicians are focused on the national good.

So how can trust in government be repaired? Is that even a realistic goal?

There are two reasons why it may yet prove possible.

The first is that there’s at least one recent precedent, highlighted in a fascinating commentary by Asia specialist Rorry Daniels for the Brookings Institution. It’s Taiwan, where until a few years before the pandemic, trust in government had been near rock bottom.

After winning elections in 2016, President Tsai Ing-wen moved actively to rebuild trust. She appointed a technology expert who led a transformative project to use digital communication to open up government, communicate directly with citizens across partisan divides, and build consensus on key policies. And it has worked, making a big contribution to Taiwan’s early pandemic success.

And there may be another, broader model. It’s suggested by the Danish academics’ survey finding that people-to-people trust has managed to weather the pressures of the pandemic in a way that trust in government has not.

It will take time. It will surely prove difficult.

But maybe it’s part of the answer – to rebuild trust from the foundation-stone up.

Right to transfer: Why it’s a game changer for college athletes

New transfer rules give student-athletes more leverage, and more respect, than ever before. But navigating that newfound freedom, our reporter finds, is challenging coaches, schools, and players.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Xander Peters Special correspondent

College athletes are navigating a new world. In the past year, the NCAA, the body governing college sports, has opened new opportunities. Alongside the option to earn income from use of their “name, image, likeness” in advertising, players now have the right to seek a transfer of schools one time during their college careers.

The resulting upheaval is already evident: More than 3,000 student-athletes across the NCAA’s three divisions have entered the so-called transfer portal. They include players moving to top Division I football teams, but also players like Alonzo “Ace” Colvin from Baltimore, who hopes to go pro but faces an uphill climb as he heads to Ellsworth Community College in Iowa Falls, Iowa.

Across the NCAA, one of the biggest implications of all this is a culture shift. With players having newfound leverage, college coaches can no longer operate in dictatorial fashion. Instead, pressure is rising for coaches to continue resonating with players on a personal level beyond the high school recruiting process, or risk losing them.

As Matt Brown, a sports reporter with a newsletter on college sports, says, “It’s changed how coaches coach, it’s changed how schools recruit, and it’s changed how athletes approach their own recruitment.”

Right to transfer: Why it’s a game changer for college athletes

Alonzo Colvin goes by “Ace,” a family nickname. He hopes to work in film after college, eventually making his way up to a director’s seat. But first, he’s attempting to achieve his goal of becoming a professional football player.

Compared with past generations of student-athletes, Mr. Colvin has more potential avenues he can take. He’s currently an outgoing first-year player at ASA College’s junior college football program in Miami. But in hopes of additional playing time – and game film to present to programs once his junior college career concludes – he intends to transfer to Ellsworth Community College in Iowa Falls, Iowa.

Mr. Colvin is able to explore new options without penalty through a new rule on one-time transfers approved in April by the NCAA, college athletics’ governing body. The rule allows all student-athletes one opportunity to transfer colleges without losing a season of eligibility or sitting out an entire year. (Student-athletes have four years of eligibility, plus a redshirt practice season.)

“We’re more than just athletes. We’re not robots,” Mr. Colvin says. “You get a full scholarship, but there’s more to it.”

His experience, modest as it may sound, is a sign of tectonic shifts underway in college athletics. Changes by the NCAA in recent years also include the 2018 launch of a player database called the “transfer portal” and last year’s approval of “name, image, likeness” (NIL) profit opportunities for players.

The result is an era of heightened leverage for players in football, basketball, and beyond. No longer are athletes forced to grin and bear it through administrative turmoil, coaching turnover, or lack of playing time. They can opt to leave – mirroring the free agency concept in professional sports – although with some personal risk if no other program will take them.

“I think what this has done is allowed almost a reset of the market, so to speak, where, for whatever reason, if the player is not happy with their experience, they have an opportunity to see if there are other opportunities,” says Brian Spilbeler, the chief operating officer at Tracking Football, an NCAA-approved scouting service that partners with collegiate all-star games.

The changes come, he notes, as fans have increasingly clued in to the incongruence between the model of amateurism and the fact that student-athletes are part of a growing multibillion-dollar industry. For some fans, it’s become hard to differentiate between the NCAA and professional leagues.

“But obviously, there’s a big difference, which is that these are student-athletes,” Mr. Spilbeler says. “You’re starting to see this shift, where athletes want more rights, they want more opportunity, and they want to be treated more as an employee – a professional – as opposed to a student-athlete. There’s pros and cons to that. We’re going through a pretty steep learning curve.”

The disruption is visible in the data: More than 3,000 players across the NCAA’s three divisions have entered the NCAA transfer portal so far – and more than 1,200 are Division I Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) scholarship recipients, according to numbers released by the scouting service Rivals. Half of those FBS scholarship athletes haven’t found a new home, Rivals says.

With rules change, a shift in culture too

Colleges and players alike are just starting to navigate the ensuing upheaval.

Perhaps most notably, the transfer opportunities are altering the culture of college sports – forcing coaches and administrators to better monitor the experience their programs offer athletes.

There was a time when coaches would recruit players and, colloquially speaking, “deprogram” them. It’s a means of molding players into part of a team’s culture, and a reminder that their days of dominating the sport in high school are over. But with players’ newfound leverage, coaches have found themselves reinventing the recruiting process on the fly as they “continuously recruit their own players,” says Matt Brown, a sports reporter whose newsletter Extra Points explores the college part of college sports.

“It’s changed how coaches coach, it’s changed how schools recruit, and it’s changed how athletes approach their own recruitment,” he says.

The era in which college coaches could throw their weight around in dictatorial fashion are over. Coaches must find a way to continue resonating with players on a personal level beyond the high school recruiting process, or risk losing them. That might consist of checking on a player’s attitude and their experience so far in college sports, or asking about their personal goals or their mental health.

Not everything is going smoothly as the changes take root.

Some coaches and onlookers alike complain of “tampering” as the new rules become an opportunity for some teams to lure players away from others. Similarly, some programs may find it so easy to harvest talent through the transfer portal that they pay less attention to nurturing new players who are fresh out of high school.

“There’s unintended consequences to all this,” Mr. Brown says of the portal and NIL. “There’s some positives, and there’s some negatives.”

And cultural change in locker rooms doesn’t come easily. Mr. Brown notes the University of Hawaii as an example, where a slew of star players opted to enter the NCAA transfer portal due to what former players say was a verbally abusive, toxic atmosphere. On Jan. 7, former Hawaii Rainbow Warrior players and several parents testified to a state Senate hearing about Todd Graham’s tumultuous tenure as head coach.

A week later Mr. Graham resigned on his own accord.

Whatever the challenges, however, the new NCAA environment promises to make student-athletes better respected. Mr. Brown calls the shifts “a very big win for athletes’ rights, for athlete flexibility.”

Still not an easy path for athletes

Mr. Colvin is an underdog compared with star Division I players. That’s why he’s taken his future into his own hands by deciding to transfer to a new school.

The benefits that draw him to college sports come with counterweights, Mr. Colvin admits. His experience as a college student won’t mirror those of his peers. Frequent travel will be required, meaning he’ll have to sit out on some classes that he might have preferred to enroll in. He likely won’t have the time to pursue an internship, or study abroad, or join a fraternity.

“The NCAA likes to tell everyone that they’re probably going to go pro in something other than sports, and your compensation for playing a sport is a college education,” Mr. Brown says. “You get this degree, but there’s a difference between a college degree and a college education.”

Still, the horizons for college athletes are widening, Mr. Colvin says.

He hopes to have an NIL deal done soon but doesn’t share details. To land a deal that makes a difference for him and his family, he must build a following. Mr. Colvin had a brush with fame as a high school student, when a documentary series was made about his team at a low-income Baltimore high school. Former NFL star and talk show host Michael Strahan was among the series’ producers. Mr. Colvin and one of his teammates were featured on “Good Morning America” to discuss the series last year.

The gains so far for student-athletes are incremental and, to many like Mr. Colvin, incomplete.

He mentions a cousin, who’s also playing college football. His cousin couldn’t afford to pay his phone bill a few months back, and he doesn’t own a vehicle. When a family emergency happened at home last year, his cousin felt helpless.

“There’s still so many kids who are struggling outside of football. Our mental health, people don’t take that seriously,” Mr. Colvin says. “They only really care about us on the football field.”

People like Mr. Spilbeler say they’re working to create a better future for all those involved in college sports. How it will play out is uncertain, but the motion is already set in place for college athletics’ continued evolution.

“Right now, we’re in the midst of a pendulum swing, and there’s a lot of factors playing out simultaneously,” Mr. Spilbeler says. “It’s hard to chart exactly where all this is going to go. … We’re in the mix of trying to sort it all out right now.”

How a Canadian Twitter feed is kindling national art pride

Popularizing art can be difficult. But our reporter explores a Twitter feed that’s offering the joy of discovery and awakening national pride in Canadian artists and their works.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Donna Zielinski, a painter from Quebec, happened to be scrolling through the @CanadaPaintings Twitter feed in late January, when she saw one of her own works, “Skating Along the Rideau Canal.”

She tweeted at the time what an honor it was, and how in awe of the site she is. “It features Canadiana in a beautiful way,” she says in a recent interview, noting that she is particularly drawn to the uniquely national content.

Amid the ranting and raging on Twitter, this quiet feed has become beloved – especially in the past year, reaching more than 116,000 followers today who gleefully retweet the Canadian works thousands of times. It’s the kind of engagement that makes the art world envious.

Part of the joy of @CanadaPaintings, which started in 2018, is the discovery of Canada itself, which spans 3.8 million square miles, yet 90% of Canadians live within 100 miles of the United States border. That exploration appears to be one of the anonymous curator’s motivations. The feed takes viewers from Dawson City in Yukon, to Ellesmere Island in Nunavut, to the easternmost coast of Newfoundland and Labrador.

“The Canadiana aspect reaches deep in the souls of many Canadians,” says Ms. Zielinski.

How a Canadian Twitter feed is kindling national art pride

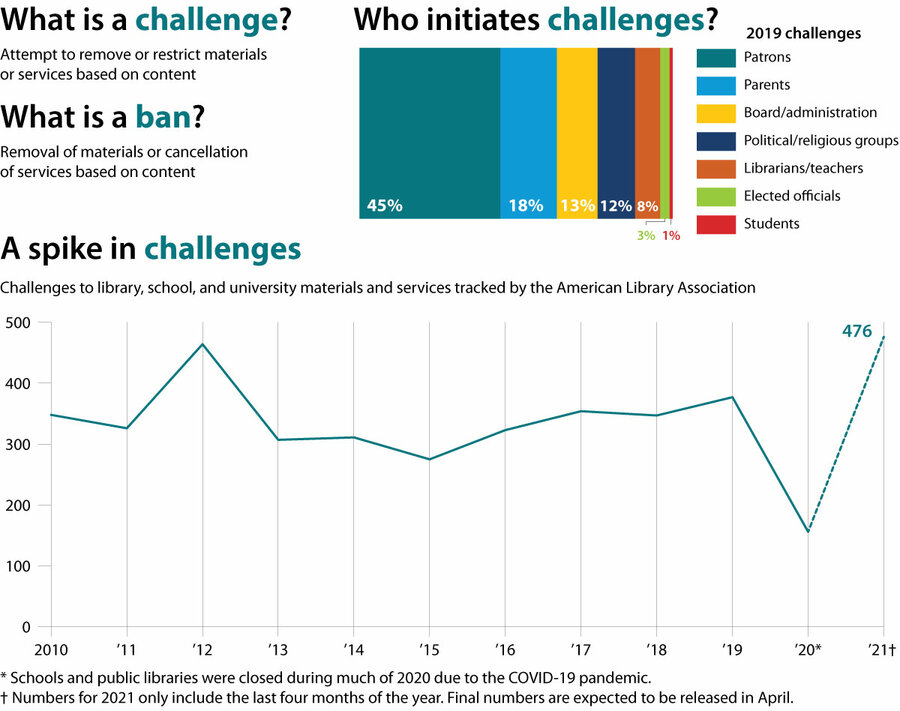

Twitter is full of ranting and raging. But amid the rancor, art will often suddenly appear in thousands of Canadian feeds: the image of a lighthouse in a waning winter sun; the depiction of pines reflected in a frozen pond; a pair of night owls in stonecut and stencil by Inuit artist Kananginak Pootoogook.

The daily posts from @CanadaPaintings never list more than the artist and a work’s title and date. Even the curator wishes to remain anonymous – in declining an interview request, she allowed only that she was a busy elementary school teacher who enjoys discovering the works as much as her viewers do – which is part of the unassuming beauty of this social media feed.

That’s not to say it doesn’t elicit a response. It’s become beloved – especially in the past year, reaching more than 116,000 followers today who gleefully retweet the Canadian works thousands of times, mostly without comment. When discussion ensues, it’s usually just to say “stunning” or “exquisite.” On a recent post of a print titled “Joy” – a work by Métis artist Christi Belcourt that evokes Indigenous beadwork – one follower comments: “Thank you for this burst of colour – a glorious addition to my feed!”

It’s exactly the kind of conversation that makes Sara Angel, founder and executive director of the nonprofit Art Canada Institute (ACI), such a fan of the feed. “It’s not what I would call an art cognoscenti,” she says of the commenters. Rather than attracting followers with analysis, @CanadaPaintings offers vibrant content that has introduced a nation to its artists and its vast territory and traditions.

Dr. Angel founded ACI in 2013 to make Canadian art more accessible after searching for content online while pursuing her Ph.D. and finding next to none. “There hasn’t been a really strong, concerted effort to say, ‘We are going to create a canon of Canadian art.’” She imagined her three kids typing “art” into a search engine and only coming up with American or European artists. In the 21st century, she says, Canadians “will not know the artists of their country unless it’s digitally out there and accessible.”

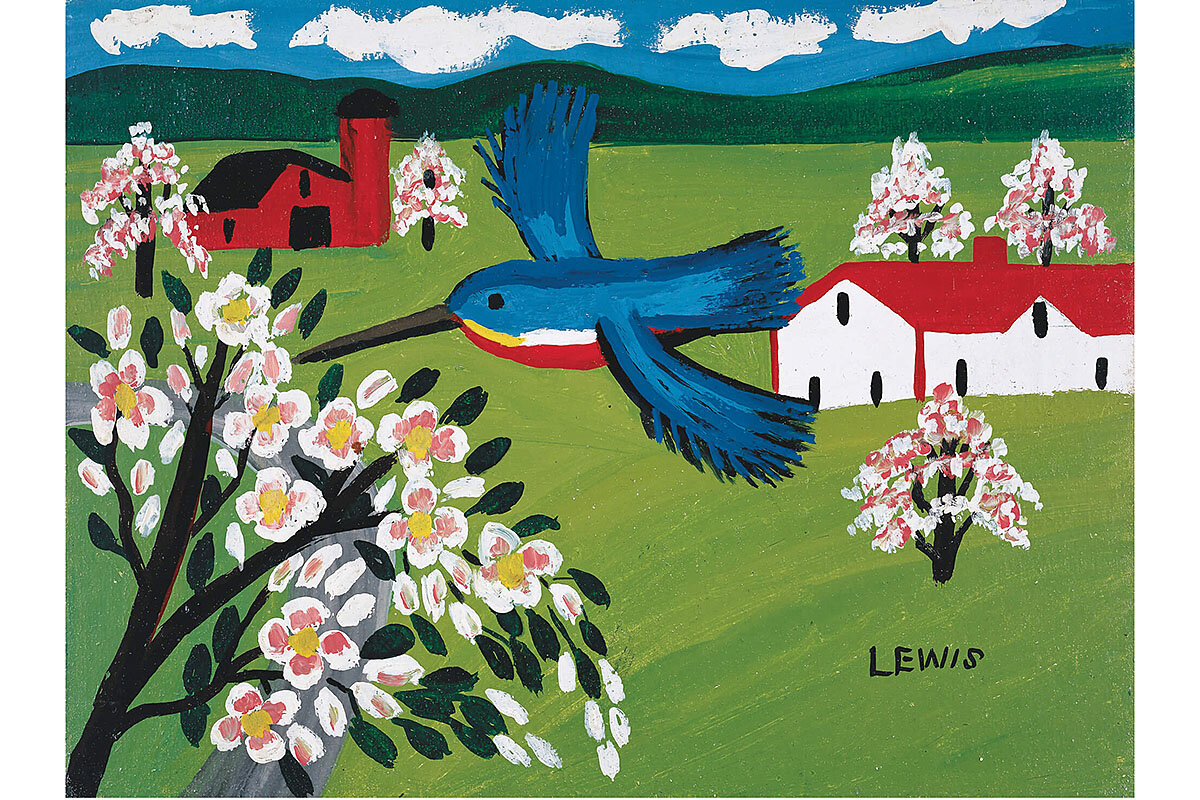

Some of the artists are world-renowned or close to it, like Tom Thomson or the Group of Seven – early 20th-century landscape artists inspired by the Canadian wilderness. There is Emily Carr, known for her depictions of Indigenous culture on the Pacific Northwest coast, or Maud Lewis, the Nova Scotian folk artist featured in the Hollywood film “Maudie.”

Yet there are so many more that should be far more widely known, says Dr. Angel. She cites Walter Allward, who created the Canadian National Vimy Memorial pictured on the Canadian $20 bill; Alex Colville, the Maritime figurative painter; or Anishinaabe artist Norval Morrisseau, considered by many as the “grandfather” of contemporary Indigenous art in Canada, she says.

Part of the joy of @CanadaPaintings, which started in 2018, is the discovery of Canada itself, which spans 3.8 million square miles yet 90% of Canadians live within 100 miles of the United States border. That exploration appears to be one of the curator’s motivations. The only description in the Twitter bio is a quote by Group of Seven artist Lawren Harris: “Above all, we loved this country and loved exploring and painting it.” @CanadaPaintings takes viewers from Dawson City in Yukon, to Ellesmere Island in Nunavut, to the easternmost coast of Newfoundland and Labrador. They bear witness to bear skinning, to moose peering at them from the woods, to Arctic oceanic wildlife.

The feed also attracts artists themselves. Donna Zielinski, a painter from Quebec, happened to be scrolling through @CanadaPaintings in late January when she saw one of her own works, “Skating Along the Rideau Canal.”

“An absolute huge honour to be featured by this account, that I am so in awe of,” she tweeted. “It features Canadiana in a beautiful way. They don’t seem to have any ulterior motive,” she adds in an interview, noting that she is especially drawn to the uniquely Canadian content, featuring traditions from “the north” – at this time of year skating, ice carvings, and hockey matches. “The Canadiana aspect reaches deep in the souls of many Canadians,” she says.

Now if only followers could know who the curator is. “I’d love to interview her,” says Dr. Angel, who has also tried to get a response. “It’s not just a little successful; it’s more successful than what any gallery or what anybody is doing,” she says. “She has such a great eye.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Breaking gambling’s grip on the Super Bowl

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

A new course at the University of New Haven offers this promise to students: “We’re going to train you to protect the sports that you love.” Designed to provide tools and skills for people to spot corruption in sports, the course is well timed.

With gambling on sports now legal in 30 states, this year’s Super Bowl is expected to set a record for the number of Americans wagering on the championship game. And along with this record come rising concerns that gambling on pro football will, as NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell once put it, “fuel speculation, distrust, and accusations of point-shaving or game-fixing.”

The National Football League is already under a cloud of suspicion over how it maintains the integrity of its games – even as it partners with the gambling industry. This month, former Miami coach Brian Flores alleged in a lawsuit that the Dolphins team owner offered him $100,000 per game in 2019 to intentionally lose in order to improve the team’s ability to draft better players.

If the allegations are proved to be true, football fans might begin to doubt the league’s official data – which is used widely by gamblers. Pro sports must return to the purity of athletic competition.

Breaking gambling’s grip on the Super Bowl

A new course at the University of New Haven offers this promise to students: “We’re going to train you to protect the sports that you love.” Designed to provide tools and skills for people to spot corruption in sports, the course is well timed.

With gambling on sports now legal in 30 states since a 2018 Supreme Court ruling, this year’s Super Bowl is expected to set a record for the number of Americans wagering on the championship game. Total spending on bets is estimated to be unprecedented $7.6 billion. And along with these records are rising concerns that gambling on pro football will, as NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell once put it, “fuel speculation, distrust, and accusations of point-shaving or game-fixing.”

The National Football League is already under a cloud of suspicion over how it maintains the integrity of its games – even as it partners with the gambling industry. This month, former Miami coach Brian Flores alleged in a lawsuit that the Dolphins team owner offered him $100,000 per game in 2019 to intentionally lose in order to improve the team’s ability to draft better players. That charge was followed by a similar complaint against the Cleveland Browns by former coach Hue Jackson.

If the allegations are proved to be true, football fans might begin to doubt the league’s official data – which is used widely by gamblers. While most pro sports have set up systems to watch for match-fixing and betting irregularities, the rapid increase in legal sports gambling will test those systems.

“The NFL has always prided itself in ‘Every game matters, no matter what.’ OK, and now all of a sudden, it looks like that’s not quite true,” Richard McGowan, a Boston College associate professor, told The Boston Globe.

Cheating scandals in athletic competitions, from bribing of players to doping, have rocked many sports worldwide. Yet they need not prevent sports from returning to the purity of their ideals. Athletics, writes Michael Sandel, a political philosopher at Harvard University, must “fit with the excellences essential to the sport.” Rules for sport must make sure sports do not “fade into spectacle, a course of amusement rather than a subject of appreciation.”

For sports fans, such appreciation can include joining together to safeguard a sport. There’s now even a university course in how to do that.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The ‘eternal noon’ of existence

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Randal Craft

Sometimes it can seem that health is like a setting sun, diminishing as time goes by. Recognizing our immortal nature as God’s children opens the door to greater freedom and healing, regardless of where we are in life.

The ‘eternal noon’ of existence

I don’t think I’ll ever be able to look at a clock the same way again. It happened a day or two after the shift away from daylight saving time took place, when all clocks were supposed to be set back an hour. I was in my office and noticed a clock on the wall that hadn’t been changed yet and that showed the time to be about noon.

This got me thinking about the concept of an “eternal noon.” It’s an idea from the textbook of Christian Science, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, who founded the Monitor. She writes: “The measurement of life by solar years robs youth and gives ugliness to age. The radiant sun of virtue and truth coexists with being. Manhood is its eternal noon, undimmed by a declining sun” (p. 246).

Christian Science, based on Christ Jesus’ teachings, explains that we’re made in the likeness of God, Spirit, and therefore immortal – eternally free of any material measurement of time. That is to say, the passing of time can’t dictate the condition or quality of God’s man – you and me – because we are truly spiritual, not material.

So, true manhood and womanhood are always at “eternal noon.” We forever express God’s ageless qualities of goodness, perfection, wisdom, beauty, and holiness. This spiritual nature is never subject to the passing of time depicted by a setting sun. And through prayer we can each prove something of our true being at “eternal noon” in God.

At one point, I pulled a muscle in my arm. A fellow I was talking with one day said something like, “You can expect to go through those kinds of things as you get older, and they are harder to overcome.” Well, I mentally affirmed right away that this was not true about any of us as the perfect, spiritual offspring of God. No limitations, including age-related ones, can ever affect our true being.

There is a decision we all need to make: to accept a limited, material, aging view of ourselves and others, or to acknowledge our eternal, spiritual identity as God’s offspring. I chose the latter and prayed to God, affirming my immortal, uninjured, painless identity, never susceptible to physical issues associated with states and stages of mortal life. Nothing about our real selfhood can ever deviate from our Godlikeness, because we are created as the expression of divine goodness and perfection, not as material beings.

As I continued to pray along those lines, I felt confident that healing of my arm would take place. And that’s what happened. It seemed so natural to find that I was totally free of the condition, and I was truly grateful.

Now I always leave one of my office clocks set at noon. It has come to serve as an ongoing reminder of our eternal, spiritual being in God.

If life presents us with issues that seem age-related, we can maintain a higher, spiritual perspective about ourselves as immortal and ageless – always at “eternal noon” in God – and experience the healing that results. As Mrs. Eddy states: “Life and goodness are immortal. Let us then shape our views of existence into loveliness, freshness, and continuity, rather than into age and blight” (Science and Health, p. 246).

A message of love

Rounding the bend

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a story about Capitol Hill bird-watchers who are bridging the political divide.