- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 14 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- The Rodney King effect: 30 years after riots, how far has LA come?

- As they aid Ukrainians, Russians abroad struggle with own identity

- Traveling with Biden on a two-day presidential whirlwind

- Trees for a desert and fish for a sea: Repairs from Oaxaca to Abu Dhabi

- A circus troupe offers hope to Senegal’s street children

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Justice rising?

Ali Martin

Ali Martin

I was away at college in the spring of 1992, when Los Angeles – my hometown – erupted in violence, generations of anger and frustration boiling over at the acquittal of four white police officers who had beaten a Black man named Rodney King.

I grew up in the Valley, 20 miles and a world away from the heart of the riots in South Central, but my parents and grandparents were also native Angelenos, and to see the city tearing itself apart tore at us too. My memory holds clear snapshots of the violence I saw on TV that week – but even clearer is the sound of my mom choking up when she called to tell me, “Our city is burning.”

That was my awakening to the persistent, crushing weight of institutional racism. There was an undeniable dissonance between the dark, grainy video that showed Mr. King under relentless attack, and the void of accountability.

The Monitor’s Francine Kiefer went to South Central – now called South Los Angeles – to see what we’ve learned in the 30 years since. Amid the rubble of still-vacant lots, justice is emerging. It’s too slow, and it’s too little – but it’s there, and it has momentum.

Justice takes a lot of forms in South LA: a public swimming pool, commercial investment, a safe and well-resourced school. But the progress is complex, and some obstacles, obstinate. The police brutality behind the South Central uprising 30 years ago, and the Watts uprising nearly 30 years before that, echoed unmistakably when police in Minneapolis killed George Floyd two years ago.

It’s hard not to be cynical when you see a cycle. But Francine takes us beyond cynicism, on a tour of South LA that shows hope and agency at work – seeds of justice that will need a hand from respect, partnership, and opportunity in order to thrive.

Thirty years later, Rodney King’s simple plea “Can’t we all get along?” is more poignant than ever.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

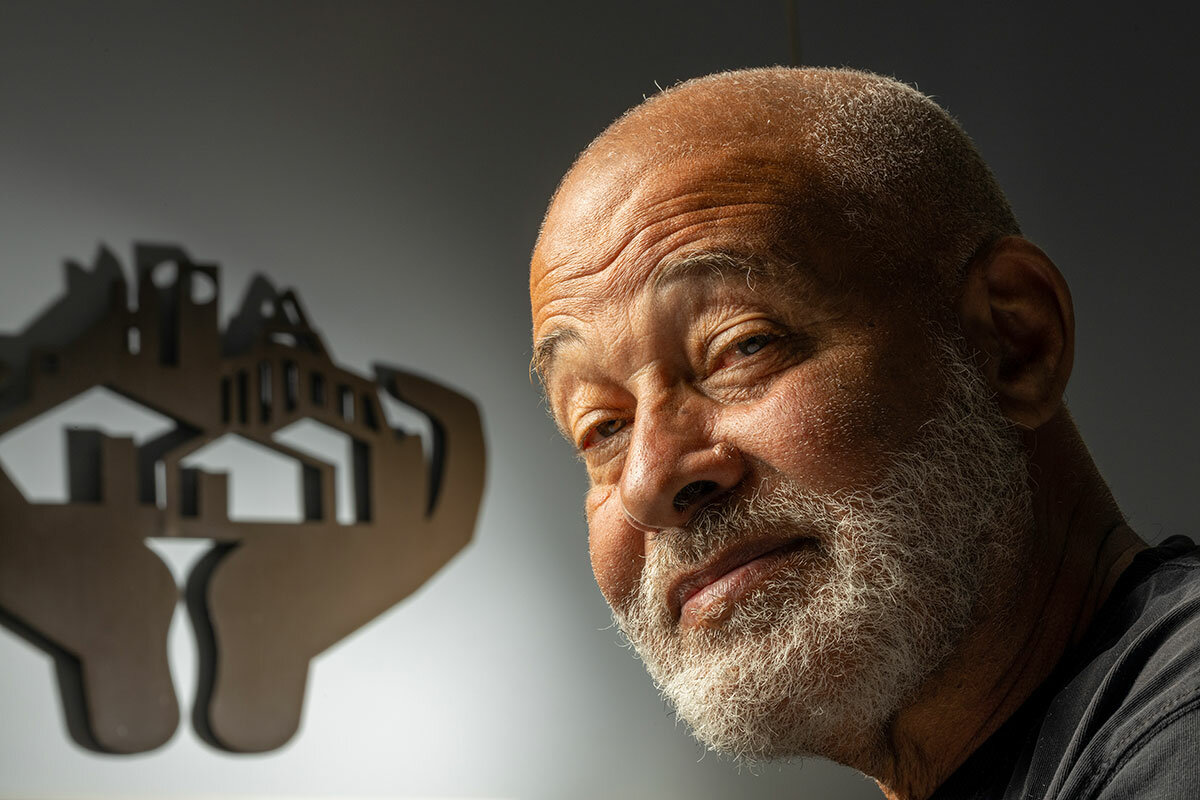

The Rodney King effect: 30 years after riots, how far has LA come?

This week marks 30 years since the race riots in South Central Los Angeles, ignited by the acquittal of four white police officers for beating Rodney King, a Black man. In today’s South LA, we found setbacks mixed with progress, and stories of hope that reveal a path toward justice.

At the start of the 1992 Los Angeles race riots, Marsha Mitchell was a young reporter at the Los Angeles Sentinel, the city’s oldest Black newspaper. When the inciting verdict was read – four white police officers acquitted of beating a Black man named Rodney King – she went to the front of the newsroom in South LA and looked out the picture window. The violence had started.

Ms. Mitchell headed to First AME Church, where then-Mayor Tom Bradley was addressing the verdict. When a nearby gas station was set on fire, the mayor sent everyone home. “Everything was on fire. It was one of the most traumatic experiences of my life,” she recalls.

Three decades later, the justice narrative of the LA uprising is still being written, in the City of Angels and nationally. Its pages cover significant reforms in the Los Angeles Police Department – a process that’s ongoing. Its arc will be shaped by this year’s election for mayor, and elections across the country.

Darnell Hunt, dean of social sciences at UCLA, describes changes since the riots as “kind of a mixed bag.” The LAPD is “a far cry” from 1992, but “the more things change, the more they stay the same.” Citizens can now police law enforcement with cellphone videos, and the Black Lives Matter movement has kept up pressure against race-based police brutality. But you still have the murder of George Floyd, he says, and this month, the fatal shooting of Patrick Lyoya in Grand Rapids, Michigan. “We are 30 years later dealing with the same policing issues.”

The Rodney King effect: 30 years after riots, how far has LA come?

John Thomas grew up in South Los Angeles – then called South Central. The son of a single mother, one of six kids, he says he never had a positive encounter with a police officer until he became one. Just like other African American youths, he was stopped often without provocation and with no explanation.

On April 29, 1992, he was working undercover in the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) narcotics division when they saw on TV that a jury had acquitted four white LA police officers for severely beating a Black motorist, Rodney King, a year earlier.

His supervisor sent him home, not expecting any trouble, but the young officer knew he would be called back. This was a unique case. In a time before cellphone cameras, a citizen had caught the sustained beating on a hand-held video camera, on March 3, 1991. The grainy footage was aired on TV stations around the world and used as evidence at the trial. This was not a Black man’s word against that of white officers. Anything other than “guilty” was going to be explosive.

And so it proved. The news ignited days of looting, fires, and deaths – a generational precursor to the civil unrest and outrage over the police killing of George Floyd.

The violence started in South Central and quickly spread north to Koreatown, where shop owners fired guns to defend their businesses. Resentment had been festering among Black locals over numerous Korean-owned liquor stores in South Central, which profited from the Black community with no reinvestment. Just after Mr. King was beaten, a Korean American liquor store owner shot and killed a 15-year-old African American girl, Latasha Harlins, from behind as she was leaving the store after an altercation over a $1.79 bottle of orange juice. The owner was convicted of voluntary manslaughter, but ended up getting probation – an injustice still fresh in the minds of rioters.

So many fires were set that thick smoke forced Los Angeles International Airport to reroute flights and operate on only one runway. By the time it was all over, the National Guard and federal troops had arrived, more than 60 people had died, and more than $1 billion in damage had been done.

“The most troubling thing for me, was these were places I grew up. … These were often shop owners I knew, and I knew they were struggling. Korean, white, and Black, these were good people who lost their livelihoods,” says Chief Thomas, who served 21 years in the LAPD and recently retired as chief of public safety at the University of Southern California. The other “very troubling” thing was to hear some of his “less than sensitive” partners say “let ’em burn it down, they’re the ones that gotta live here.”

Three decades later, the narrative around justice and the LA uprising is still being written, here in the City of Angels and nationally. Its pages cover significant policy and staffing reforms in the Los Angeles Police Department – a process that’s ongoing. Its arc will be shaped by this year’s election for LA mayor, and elections across the country. The story of the riots and their aftermath is also told in the individual lives of people of color in South LA, residents like Nate Carter, a midcareer Black professional and a proud and hopeful homeowner, and Bruce Patton, a Black tutor who has experienced three uprisings sparked by police brutality and who finds persistent discrimination against Black people.

For many people in this vast, marginalized community, economic and social conditions have not improved – and in some key respects are worse than 30 years ago. Residents here face significantly lower earnings and higher housing costs than in 1990. And they still feel marginalized by long-standing prejudices and broken promises of public and private investment.

But others see signs of hope – not necessarily regarding policing – but progress taking root in the community.

SEEDs of hope

Óscar Alvarez is too young to have experienced the Los Angeles riots. He was born three years later. But this energized community organizer has taken the time to learn about them. It’s important to dive into that history, he explains, because it has profoundly affected his life and the lives of others who live in the Black and Latino swath that is South LA, the epicenter of the uprising. It needs to be understood, he adds, in order to “control the narrative” and “create the solutions that work better for us.”

The narrative for Mr. Alvarez centers on the intersection of Vermont and Manchester avenues, a commercial wasteland that’s beginning a new chapter of redevelopment. He walks up to the stop where he used to catch a city bus to high school. It’s right next to an enormous vacant lot cordoned off by a chain-link fence. The buildings that once stood there burned to the ground in the ’92 riots. Except for a lonely Payless Shoe Store that came and went, the lot – about four acres – has remained undeveloped for his entire life.

As a youth waiting for the bus, he’d ponder why things were the way they were – “super dark” for him, his two siblings, and his low-income, immigrant, single mom. “You really begin to question your own sense of worth.” But going to the University of California, Berkeley gave him a new perspective, and he began to find answers. “Fortunately, I was able to make sense of it, and understand it’s not a reflection of me. But it’s very hard to do that, right? When everything else tells you otherwise.”

After years of unfulfilled promises of a retail center from the lot’s owner, a real estate developer in Beverly Hills, the property was taken by eminent domain by the County of Los Angeles. The county’s plans include affordable housing to be built by a nonprofit developer, a grocery store, and a school. The SEED school – a public, college-prep boarding school to help local disadvantaged students – is already under construction. Groundbreaking on the mixed-use development, named Evermont by the community, began last week.

Across the street, at the site of a fashion wig store that has been vacant “forever,” Mr. Alvarez has led an effort by the local nonprofit Community Coalition, where he works, to create a “People’s Plaza.” It’s the result of months of talking with community stakeholders about what they want, and winning a city grant to build a walkable green space that will serve as a community gathering space and help improve walkability, economic activity, and pedestrian safety.

“The solutions that we’ve been looking for have always been within the residents,” he says. “We can create what we want for ourselves.”

Policing “on the right path”

The LAPD has made “a lot of progress” from the days of warrior-style policing, says Chief Thomas. High-profile commission reports and recommendations, more than a decade of federal oversight, lawsuits, and public pressure have propelled reforms. They include a police chief prioritizing trust and accountability, an inspector general, a far more diverse police force, the spread of community policing, body and vehicle cameras, and in the wake of George Floyd, the banning of “chokeholds,” a practice forbidden now in more than a dozen states. In March, the LAPD said it would limit “pretextual stops” for minor violations, such as a broken taillight, that lead to searches. Philadelphia, Seattle, and other cities have taken similar steps.

Key statistics on use of force reflect these changes. In 1992 the LAPD had 108 instances of police officer shootings, typical for that time. In 2021, it was 37 – a spike from the previous couple of years, which were 30-year lows. In 1992, more than 60% of the force was white; in 2021 force diversity corresponded closely to LA’s ethnic makeup: 52% Hispanic, 28% white, 11% Asian/Pacific Islander, and 9% Black.

“In LA, I think policing is on the right path in its evolution. It’s becoming more inclusive. It’s listening more,” says Mr. Thomas. “But I think there’s a lot more that needs to be done,” he says, including training, institutional and cultural change at the department, the need to address cynicism among officers in high-crime areas, attending to the wellness of front-line officers, and replenishing the ranks of retiring Black officers.

Bottom line, institutions and American culture “still look at the face of violence in America as a Black face.”

Steps forward – and back

Darnell Hunt, dean of Social Sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles, describes the changes since the early ’90s as “kind of a mixed bag.” The LAPD is “a far cry” from then, but “the more things change, the more they stay the same.” Citizens can now police law enforcement with cellphone videos, and the Black Lives Matter movement – founded in Los Angeles – has kept up pressure against police brutality of Black people and other people of color. But you still have the murder of George Floyd, he says, and this month, the fatal shooting of Patrick Lyoya in Grand Rapids, Michigan. “We are 30 years later dealing with the same policing issues.” Indeed, nearly everyone interviewed in South LA said that they did not trust the police.

Other factors are also shaping the narrative. Policing across America is in a workforce “crisis,” having trouble recruiting and retaining officers, according to a 2019 Police Executive Forum Research study. Since then, the pandemic has caused stresses in police work, and law enforcement faced mass demonstrations and hostility in the wake of Mr. Floyd’s murder in 2020.

“Policing is in collapse,” says Eugene O’Donnell, a former New York police officer and a professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. “Nobody wants the job.” It was already “a big ask” of young people “to take a life-and-death risk in a country that’s armed to the teeth. Ten years ago was hard. Post Floyd, it’s all but impossible.” The essential problem, he says, is that the call has gone out across the country for policing that doesn’t create conflict, where there’s no use of force – and that’s not policing.

In a period of high-profile retail crimes, robberies, and murders, public safety is a top issue in LA’s mayoral race, with both Democratic leading candidates pledging to increase the police force.

Decades of disinvestment

It’s easy for people to assume that the LA uprising was a singular incident, says LA County Supervisor Holly Mitchell, a third-generation Angeleno whose district includes the Vermont-Manchester intersection. But much like the Watts uprising nearly 30 years prior – and the George Floyd civil unrest nearly 30 years after – “it’s a culmination of a set of circumstances that that event ignited, but that singular event is not the root cause.”

The root causes, she and others say, are racism, class, and lack of access to resources. “I think sometimes we get caught up in the issue that ignites it, and we continue to fail to address the root causes, and I think we fail to do that because therein lies the hard work.”

At the start of the 1992 riots, Marsha Mitchell (no relation to Holly) was a young reporter at the Los Angeles Sentinel. Fresh from UCLA, she wanted to work at the city’s oldest Black newspaper covering a community she loved. When the verdict was read, she went to the front of the newsroom and looked out the picture window. A man was on a pay phone across the street. “He took out a pistol and shot a dog, he was so angry,” she recalls.

She then called her mother, who had lived through the 1968 riots in Chicago after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. Go home, her mother implored. Instead, she jumped into her little sports car and headed to First AME Church, where Mayor Tom Bradley – the first Black mayor of Los Angeles – was addressing the verdict. When a nearby gas station was set on fire, the mayor told everyone to go home immediately. “Everything was on fire. It was one of the most traumatic experiences of my life,” Ms. Mitchell says.

It was a violent time, she recalls, with the crack cocaine epidemic, gangs, and guns filling the void left by well-paying manufacturing jobs that began disappearing in the 1970s. But as a child, “we had a really good lifestyle,” she says. Her uncle and aunt bought a three-bedroom house – affordable from his job at Uniroyal Tire, which employed thousands before it was shuttered in 1978.

A person ought to be able to find gainful employment in South LA today, says Ms. Mitchell, who is the communications director for Community Coalition. But “there’s been 40 years of disinvestment.”

Historical shifts

While the lot at Manchester and Vermont is finally being developed it’s one of about 3,000 empty lots in South LA, some going back to the Watts uprising. Although the number of liquor stores has decreased since the 1990s, they’re still found in abundance, along with smoke shops and marijuana dispensaries – “nuisance businesses” that foster crime and addiction, says Marsha Mitchell.

In many ways, South Los Angeles resembles other U.S. urban areas, explains Paul Ong, director of the Center for Neighborhood Knowledge at UCLA. Racial segregation continues; African Americans are migrating to the exurbs in search of better schools, jobs, and more affordable housing; the Latino population is growing and working, but on the bottom rung of the economic ladder; white and Asian people are moving in, along with gentrification.

However, South LA is unique in other ways, he says. It’s huge – similar to San Francisco in geographic area and population. It also looks different from other distressed urban areas – instead of high-density high-rises, it’s single-family homes and garden apartments. It was considered a haven for Black families when the Watts uprising broke out in August 1965. Professor Ong says “people were really puzzled” then, including President Lyndon B. Johnson, who had pushed through the historic Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts. “How is it possible after all we’ve accomplished?” the president asked.

But legislative gains did not match conditions on the ground. Palm trees and sunny skies aside, the residents of South Central were disenchanted over justice delayed, and persistent discrimination, racism, and unequal access to economic opportunity, according to a report by Professor Ong and his colleagues, “South Los Angeles Since the Sixties.”

On four key indicators – earnings, housing, transportation, and education – residents of South LA fare worse than Los Angeles County over the period from 1960 to 2016. In three areas – earnings, home ownership, and extreme rent burden (where rent accounts for more than 50% of income) – it’s gotten markedly worse in South LA since 1960. Meanwhile, “the pandemic hit South LA hard,” says Professor Ong, disproportionately affecting jobs, health, and schooling.

Bruce Patton, who tutors higher-level math at the Community Coalition, was in junior high school at the time of the Watts uprising, mowing his grandmother’s lawn when he saw plumes of smoke rising to the south. He sets the stage for the explosion by describing discrimination in schooling at that time:

One Saturday his uncle, who was a custodian at a nearly all-white middle school on LA’s Westside, showed him the school’s wood shop. Students there were building life-size gliders and canoes. The school was surrounded by grass. His school on Vermont Avenue was surrounded mostly by asphalt. They were building a simple skateboard in wood shop, a project stretched to last an entire semester. “And we were supposed to be proud of it,” scoffs Mr. Patton. “Do you understand why there was a blow up when officers come to Watts … and it turns into something more?”

He still sees that prejudice in education. He recalls a young student whose white high school teacher recommended she come to him for help with algebra. They worked through some problems. She took her test and did so well the teacher accused her of cheating.

“We now are homeowners”

South LA is changing. Five years ago, the University of Southern California, an anchor on the northern edge of the area, expanded with its USC Village of student housing. Four years ago, it was the Banc of California soccer stadium. Last year, SoFi Stadium opened due west on Manchester Avenue. Americans got a good look at it in this year’s Super Bowl. As development comes along, it brings eateries, retail, and more investment, but also higher rents and home prices that displace people.

Nate Carter was thrilled to discover the Vermont Knolls neighborhood when he was managing the transformation of a historic Black hotel, The Dunbar, into affordable housing for older adults. He bought his Spanish-style home just off Vermont Avenue in 2017. “Probably the best decision I ever made,” he beams from the veranda of his brightly painted home in this neighborhood of tidy houses with red tile roofs.

Mr. Carter drives an electric car, rides an electric scooter to work, and loves cooking, yoga, and his 7-year-old daughter, who takes cooking classes. He’s engaged to be married and is enthusiastic about LA’s future – Super Bowl champions soon to host the World Cup, and then the 2028 Summer Olympics. Meanwhile, his best friend from childhood has bought the home across the street. “We now are homeowners at 40 years old,” he says with pride.

Just a few blocks from the construction site at Vermont and Manchester, the Algin Sutton Recreation Center stands tribute to political will and community partnership. Last year, the nearby playground was renamed for Latasha Harlins, and a joyful mural of her face brightens the rec center’s wall. She played here as a child, before she was killed in the liquor store, explains Mr. Alvarez, the community organizer. When he was a child, the surrounding grassy field was just dirt and rocks. “It was a very different park back then. You really do begin to shape someone’s upbringing by the environment you create for them.”

Rounding the corner, there’s a completely redone aquatic facility – a shimmering large pool, splash pad, and shade canopy. The year-round, state-of-the-art pool opened last year, as did another pool in the neighboring Crenshaw neighborhood – the result of a $17 million push from the city councilman and input from residents. The designers, Lehrer Architects LA, call investing in community centers like this “acts of social justice.” Black people have historically had less access to pools than white people, and 64% of Black children cannot swim.

This neighborhood holds fond memories for the manager of the aquatic facility, Glyn Owens, who used to come here from nearby Compton for Sunday lunch with his great-grandmother. It has its challenges, though. After shootings last summer, police patrolled on horseback – overkill in his view. He’s cautious about the LAPD and tells his staff – entirely Latino – to wear their uniforms on their way home so that law enforcement doesn’t stop them.

During the ’92 riots, Mr. Owens’ dad drove him around in their Volkswagen bus so that he could see it firsthand, explaining that this was his country, his neighborhood. He jumps ahead to the subject of his fiancée – an Asian woman from Orange County who knew nothing of his world and who happily went with him to a Black Lives Matter protest. “I’m like, that’s just what our country is about, what our community is about, what we teach each other.”

That sense of community is why he regularly walks the park, going up to kids smoking weed or drinking and encouraging them to come for swim lessons. One of his swimmers might even qualify for the 2028 Olympics in LA, he says. “My mission is just to really get people into the pool, swimming, and off the street,” says Mr. Owens, in his red lifeguard shorts. “I started swimming at a young age. Now I run the place.”

As they aid Ukrainians, Russians abroad struggle with own identity

For the Russian-speaking diaspora, the war in Ukraine has brought a strong desire to help Ukrainian refugees – and soul-searching about whether and how they still think of themselves as “Russian.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

Lenora Chu Special correspondent

For many members of the Russian-speaking diaspora – those who immigrated to the West from former Soviet republics – President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has stirred deep responses.

They have been motivated to provide humanitarian aid by the same sense of injustice felt by citizens globally about an unprovoked war. But their efforts are also driven by an affinity that is more personal.

United by language, culture, and history, many families span the modern borders formed after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. They left to escape political and religious persecution, or for economic opportunity. In daily life, many say they don’t overtly distinguish themselves by nationality. They are Russians, Ukrainians, Georgians, Uzbeks, or Moldovans, but often are called simply “Russians,” bound by a common language.

But as they mobilize against Mr. Putin, some are also redefining identities that had been for decades built around a more fluid sense of ancestry and nationhood.

“[The Ukrainians] are so close to us, in language, culture, everything. Why would you attack your cousins and brothers?” asks Olga Larionova, a Moscow-native recruiter in Toronto. “It’s very hard to see how one part of your country, one part of your identity, is attacking another part of your identity.”

As they aid Ukrainians, Russians abroad struggle with own identity

When Ilia heard about the exodus of Ukrainian refugees through Berlin’s main train station – a transit point for those escaping Russia’s invasion – he boarded a daylong flight from his home in Sydney, Australia, to get there.

Ilia (who prefers not to use his last name because he wants to be able to travel to Russia when needed) was born and raised in Moscow but has lived most of his adult life in Australia working as an information technology engineer. He’s part of a vibrant, mixed Russian-speaking community there, where divisions between those from Russia and Ukraine are rarely delineated, he says.

But when war in Ukraine came, he suddenly imagined that the Ukrainians he dances salsa with in his downtime would look at him differently – no longer Ilia, but “a Russian.” “It doesn’t make logical sense. I know them and they know me. But in all of this, I just feel guilty,” says Ilia, who spent two weeks of vacation at the Berlin Central Station, often at the platform as arriving trains pulled in, so that he could help orient Ukrainians in their common language of Russian.

Russians among the diaspora opposed to President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine have been at the front lines of humanitarian efforts across Europe and North America for those displaced by war – more than 5 million, according to the United Nations’ refugee agency.

They are motivated to help by the same sense of injustice felt by citizens globally about an unprovoked war, but their efforts are also driven by an affinity that is more personal. United by language, culture, and history, many families span the modern borders formed after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. As they mobilize against Mr. Putin – many for the first time – some are also redefining identities that had been for decades built around a more fluid sense of ancestry and nationhood.

“[The Ukrainians] are so close to us, in language, culture, everything. Why would you attack your cousins and brothers?” asks Olga Larionova, a recruiter in Toronto who was born in Moscow. “I think it’s very hard to see how one part of your country, one part of your identity, is attacking another part of your identity. This is what I’m struggling with.”

“This shame and this dissonance”

The Russian-speaking diaspora is made of Russians who left the country before and after the fall of the Soviet Union and those who immigrated to the West from former Soviet republics. They left to escape political and religious persecution, or for economic opportunity. In daily life, many say they don’t overtly distinguish themselves by nationality. They are Russians, Ukrainians, Georgians, Uzbeks, or Moldovans, but often are called simply “Russians,” bound foremost by the Russian language.

Ms. Larionova, whose parents and sister are still in Moscow but who grew up with deep connections to Ukraine, where her father’s family is from, says that when she heard about the invasion, for days after she woke up with that sense of dread that wouldn’t lift.

Canada, home to the largest Ukrainian diaspora in the world after Russia, expanded its support to Ukrainians with a temporary Canada-Ukraine Authorization for Emergency Travel program to bypass lengthy immigration processes. According to government figures, between mid-March and mid-April 163,747 Ukrainians had applied, with 56,633 applications approved.

Canadians, many Russian-speaking, are organizing donation drives and raising funds to help the newcomers settle. Despite watching civil rights “shrinking and shrinking” under Mr. Putin and feeling despair over his annexation of Crimea in 2014, Ms. Larionova is only now mobilizing for the first time – contributing to various drives and offering to run errands or help new arrivals with translation services.

“I don’t know how much it helps,” she says. “I feel that a lot of Russians that I know really want to help very, very sincerely. But there’s also a deep sense of this shame and this dissonance that it’s your country and your people attacking your country and your people.”

Russian tech entrepreneur Dmitry Buterin, who was born in Chechnya, arrived in Canada in 1999 already harboring deep suspicions about Mr. Putin. Today he supports various organizations working with Ukrainians on the ground, including Ukraine DAO, Holy Water, and Second Front Ukraine. But he says the most important thing he does is speak out against Russian propaganda to counter “misinformation and misunderstanding outside of Europe especially,” says Mr. Buterin, whose family enjoys a large platform because his son Vitalik co-founded the open-source blockchain Ethereum. “I’m very passionate about helping people understand the truth.”

He’s gotten flak for that. Indeed, throughout the diaspora, some Russian immigrants continue to support the war. An April rally in Berlin protesting discrimination against Russians drew about 1,000 people, some of whom carried displays of support for the war.

But the past months have also been disorienting for those who may have been politically indifferent before now. “I’ve seen more Russians who are very conflicted,” says Mr. Buterin. “Many who have identified with being part of Russia and all those wonderful aspects of Russian culture which do exist and we cannot deny, who identified themselves with the Russian nation, are now really lost and confused.”

Much of the world condemns Russia: Russians have been cut off from the international SWIFT banking system, its athletes have been banned from many international competitions, and countries are debating whether to stop buying its energy. And the country has lost moral authority that will be hard to regain, says Arman Mahmoudian, a political scientist at the University of South Florida. “I doubt that Russia, in decades or even more, can rebuild its influence over Russia’s backyard – the countries traditionally in its diaspora – and also in the West, which used to see Russia as a potential ally and now starts to view it as a threat.”

“The old and forgotten roots”

Washington-based policy analyst Jeanne Batalova was born in Soviet-era Ukraine, grew up in Moldova, and then moved to the United States. A decade ago, she would have described herself as “Russian” first, and then clarified that she is partly Jewish and partly Ukrainian.

Since 2014 and the pro-European Maidan protests in Kyiv, which preceded the annexation of Crimea, the order has shifted. “I say I’m American, then Ukrainian and Jewish, and partly Russian.”

Today she sees that identity change happening at a much wider scale among the Russian-speaking diaspora. “There is a significant shift in rethinking of identity where people are turning to the old and forgotten roots they never thought about,” she says.

Ms. Batalova has attended several pro-Ukrainian protests, with flags from the nations once part of the Soviet Union waving. She calls it partly an act of solidarity “against their historic oppressor.”

But for some Ukrainians, a new rift with Russians is also deep and pervasive. Andrij Melnyk, Ukraine’s ambassador to Germany, told the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung that “all Russians are our enemies right now.”

That trickles down to the daily lives of diaspora communities. Alex Kislicyn, who was born in Kharkiv, Ukraine, but now lives in Munich, Germany, says the situation in Russia draws parallels to Germany post World War II. “Where, on one side, the terror ended, but the other side was that nobody trusted the Germans anymore,” he says. “It needs time to heal the wounds. Maybe someday this relationship will be restarted, but not right now.”

For Ilia, the Muscovite living in Australia, the ties between Russians and Ukrainians are worth fighting to preserve.

“My general feeling is I imagine that’s how Germans felt in 1939. If two of the people I tried to help here later tell themselves and their children that not all Russians are bad because they met me,” he says, “I achieved something.”

A letter from

Traveling with Biden on a two-day presidential whirlwind

Interacting with presidents in person always generates a more nuanced impression. Our reporter shares some observations after a recent trip to the Pacific Northwest with President Biden.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

It was the Monitor’s turn in the rotation of news outlets that travel with the president, and I welcomed the opportunity to spend two solid days watching President Joe Biden up close on a trip to the Pacific Northwest.

Like many reporters, I’ve been mindful of his gaffes and miscues, in which he sometimes seems to misunderstand or mishear a question, offering a response that doesn’t correlate.

As an aside, let me point out that Mr. Biden – a high-profile Washington politician since the early 1970s – has always been known for his gaffes, and has also had a stutter since childhood.

Yes, Mr. Biden does speak more softly than he used to, and his gait is more halting. But his two-hour press conference in January was a presidential record – and a clear display of stamina that was apparent on this trip as well.

After two jampacked days, we re-boarded Air Force One to head back east, ready for some downtime. Then it happened: For the first time since becoming president, Mr. Biden came to the back of the plane and “gaggled” with us for 24 minutes, off the record.

He seemed to enjoy the give-and-take. And we got what we wanted: face time with the president. For us hacks, it doesn’t get any better than that.

Traveling with Biden on a two-day presidential whirlwind

Last week, I hit the jackpot of White House press pool assignments: Fly with President Joe Biden on Air Force One to the Pacific Northwest on a two-day swing aimed at highlighting infrastructure projects and efforts to combat climate change. Oh, and while in the neighborhood, he’ll be raising money for the Democratic National Committee.

It was the Monitor’s turn in the rotation of news outlets that travel with the president, and I welcomed the opportunity to spend two solid days watching President Biden up close. Like many reporters, I’ve been mindful of his gaffes and miscues, in which he sometimes seems to misunderstand or mishear a question, offering a response that doesn’t correlate.

As an aside, let me point out that Mr. Biden – a high-profile Washington politician since the early 1970s – has always been known for his gaffes, and has also had a stutter since childhood. He’s never been a smooth public speaker.

Now, as the oldest American president in history, he faces constant scrutiny over whether he’s up to the task. Negative and sometimes misleading characterizations abound on social media – a recent one, claiming that a “confused” Mr. Biden “turned around and shook hands with thin air,” was deemed by PolitiFact to be false. “Biden was gesturing towards his audience,” the fact-checking site concluded.

Yes, he does speak more softly than he used to, and his gait is more halting. And his staff often seems to be shielding him from reporters’ questions. But his two-hour press conference in January was a presidential record – and a clear display of stamina that was apparent on this trip as well.

The days were packed, starting with his pre-trip announcement of more aid for Ukraine and a few press questions (including one about border policy that required a follow-up clarification). Soon we were aboard Air Force One, heading to Oregon for a tour of an infrastructure project at Portland International Airport, followed by public remarks, with more than 100 local elected officials, union members, and stakeholders in attendance.

The DNC fundraiser at the Portland Yacht Club showed Mr. Biden in his element – stepping away from the mic to schmooze with donors, talking about his grandchildren, highlighting his agenda, bemoaning the state of American politics. It’s no secret that the president and his party are in big trouble heading into the November midterm elections, and he threw plenty of shade at the GOP.

“This is not your father’s Republican Party, by any stretch of the imagination. This is the MAGA party,” Mr. Biden said, referring to former President Donald Trump’s slogan, “Make America Great Again.”

Then it was back on the plane for our next stop, Seattle, and another fundraiser – this one in the multimillion-dollar home of a Microsoft executive overlooking Lake Washington. By the time Mr. Biden started speaking, it was already 9:30 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time, but he was raring to go. He spoke for a half-hour, albeit at times quite softly, before we “pencils” – no media cameras allowed – were escorted out so he could answer questions from donors privately.

We got our “lid” for the day – meaning, no more public presidential activity – after 11 p.m. Eastern time.

The next morning began with an Earth Day event in Seattle’s Seward Park, where Mr. Biden made remarks and signed an executive order focused on old-growth forests. Then it was off to a community college in Auburn, Washington, to discuss how government can help families lower costs.

By the time we boarded Air Force One for the nearly five-hour flight back east, we were all ready for some downtime. Then it happened: For the first time since becoming president, Mr. Biden came to the back of the plane where the press pool sits, and “gaggled” with us for 24 minutes, off the record.

He seemed to enjoy the give-and-take, and might have stayed longer had it not been for an announcement that the plane was heading into turbulence. Everyone had to go back to their seats and buckle up. But we got what we wanted: face time with the president. For us hacks, it doesn’t get any better than that.

Points of Progress

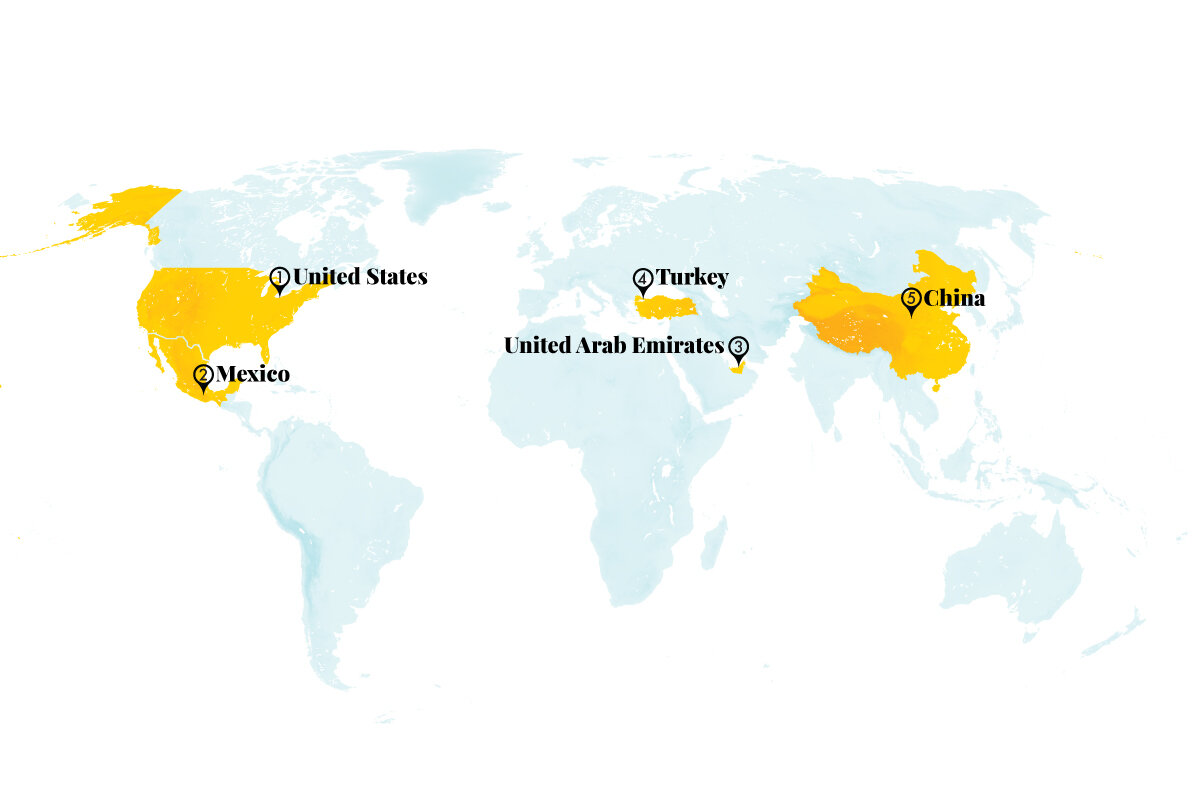

Trees for a desert and fish for a sea: Repairs from Oaxaca to Abu Dhabi

In our progress roundup, a forest-turned-desert that is being reclaimed by its Indigenous community is one example of how deliberate care, slow handiwork, and patience are improving environments on land, in the water, and in cities.

Trees for a desert and fish for a sea: Repairs from Oaxaca to Abu Dhabi

Our report this week features the alchemy of university-level experiments with algae in Turkey. And elsewhere in the world, including in Cleveland, Ohio, a rejection of the quickest and easiest path is producing results.

1. United States

Cleveland is making headway toward a circular economy by recycling components of old buildings instead of simply tearing them down. Two recent projects in Cleveland – a MetroHealth hospital campus and the headquarters of manufacturing consultancy Magnet – illustrate the importance of “deconstruction,” or the careful dismantling of a building to reuse materials.

The city’s focus on a circular economy, along with considering the use of materials from “cradle to grave,” is one way of reaching its sustainability goals. The MetroHealth campus, for example, recycled 11,181 pounds of concrete and steel, and the Magnet headquarters kept over 19 tons of waste out of a landfill. “To reach [carbon neutrality], a building has to include reuse,” said Aurora Jensen of the sustainable building design firm Brightworks. “A new building cannot really bounce back from the carbon deficit of not reusing a building.”

The Land

2. Mexico

Communities in Oaxaca have successfully revived land once lost to overgrazing and erosion. Before Spanish colonization, the Mixteca Alta region was covered with lush forest. Ample water and fertile soil supported a population of over 100,000, where today a mere 2,800 residents get by with scarce water and vegetation. But in the last 20 years, locals have transformed at least 20,000 hectares (49,000 acres) of barren land into forest.

In places, the ground was so hard that even machines couldn’t break through the rock. Community members began by restoring soil with the Gregg’s pine – one of the few trees capable of growing in such a degraded environment – and then added native species like the smooth-bark Mexican pine. In the rainy season, reforesting resembles a festival as adults and children gather to plant and share meals together. They have clashed at times with shepherds who rely on goat grazing, one of the causes of the desertification. But locals say most residents support the reforestation effort, which has earned international recognition: The site was chosen to host World Day to Combat Desertification and Drought in 2021. “Based on this work,” said forest technician Idalia Lázaro, “I fervently believe that restoration, even in the worst of cases, is possible.”

Mongabay

3. United Arab Emirates

Sustainable fishing is catching on in Abu Dhabi, with good news for threatened species. Following a 2019 report that brought to light extensive damage caused by overfishing, Abu Dhabi’s Environment Agency introduced new regulations to protect fish stocks. The agency banned excessively harmful nets and cages, limited fishing seasons to protect breeding, created new marine reserves, specified minimum fish sizes eligible to catch, and coordinated information campaigns for fishers.

The percentage of fish stock assessed as sustainably caught, as measured by the sustainable exploitation index, jumped from 5.7% in 2018 to 62.3% in 2021. Meanwhile, the spawning biomass per recruit, a calculation of the fish in the sea that reproduce, tripled from 2018 to 2020. While overfishing continues to be a problem in the region, a wide range of fish populations have boomed in recent years, and two species – haqool and aifah – were deemed to be within the limits of sustainable exploitation in 2021.

The National, Abu Dhabi Government Media Office

4. Turkey

Europe’s first carbon-negative biorefinery converts algae into fuel, food, and fertilizer. The 2,500-square-meter demonstration project, which operates out of Boğaziçi University in Istanbul, uses macro- and microalgae from a marine farm on the nearby Black Sea. The algae make their way through a filtration and pasteurization unit, a desalination unit, and an aerobic digester to become biofuel, food supplements, pharmaceuticals, and animal feed. The byproducts from these processes are used to make biofertilizer and biogas.

Beyond contributing to a more sustainable “bioeconomy,” the project is meant to help wean Turkey from its dependence on foreign fuel. Lowering industrial emissions will also help the nation avoid export tariffs under a planned European Commission carbon tax. The project is mostly financed by the European Union (85%) in partnership with the Turkish Ministry of Industry and Technology (15%).

EuroNews, Bio Market Insights

5. China

Shaanxi, one of China’s biggest coal-producing areas, achieved record air quality in 2021. The region met national air quality standards for the first time, including a 14.3% drop of PM2.5, particulate matter that is 2.5 microns or less, since 2020. In the 10 cities assessed across Shaanxi, there were 295.4 days of good air quality, 10.3 more than the national goal.

Last year, the province introduced an array of campaigns to fight pollution, such as limiting coal consumption to electricity production and enforcing penalties for companies that violate environmental guidelines. The push for cleaner air is part of a larger “war on pollution,” as Chinese Premier Li Keqiang put it in 2014, and a shift away from the priority of economic growth. On the whole, coal accounted for 56% of China’s energy consumption in 2021, down from 70% in the mid-2000s. Nevertheless, the end of coal remains far from sight as new coal power projects continue to be approved around the country.

Xinhua News Agency

In Pictures

A circus troupe offers hope to Senegal’s street children

A circus troupe in Senegal dedicated to helping abused children provides not only an opportunity for employment, but also a new way for the boys in its program to work together.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By Guy Peterson Contributor

In Senegal, an estimated 100,000 boys between the ages of 5 and 15 are sent by their families to live and study at traditional schools to learn the Quran.

But some talibés, as the boys are known, are vulnerable to exploitation and abuse from teachers. Talibés are forced to beg for money each day, and if their quota is not filled, they can be beaten and starved.

Modou Touré knows the talibé experience first-hand. He escaped his Quranic school as a boy, and after taking up circus training in Europe, he returned to Dakar and founded Sencirk, a circus troupe, in 2006. Today, the troupe provides free training to teens who have also escaped from their schools.

The program allows them to work through traumatic experiences and to see paths toward a better future, whether that means working in the circus or reintegrating into society.

An older performer and teacher at Sencirk, Sammi, explains, “We can teach them how to work together, how to grow, to believe in themselves.”

A circus troupe offers hope to Senegal’s street children

Under the shade of a dusty canvas tent in the sweltering heat, five men rehearse for a circus tour of France the following week.

They make up Senegal’s only circus troupe, and each of them took long roads to get here, overcoming difficult childhoods, facing rejection by their families after they escaped abusive religious schools, and living on the street.

In Senegal, an estimated 100,000 boys between the ages of 5 and 15 are sent by their families to live and study at traditional schools to learn the Quran.

According to human rights groups, the talibés, as the boys are known, are vulnerable to exploitation and abuse from teachers. Talibés are forced to beg for money each day, and if their quota is not filled, they can be beaten and starved.

Modou Touré escaped his Quranic school; after taking up circus training in Europe, he returned to Dakar and founded Sencirk in 2006, providing free training to teens who escaped from their schools. The program allows them to work through traumatic experiences and to see paths toward a better future, whether that means working in the circus or reintegrating into society.

Senegal has seen increasing youth unemployment, which leads many young adults to consider emigration if they can’t find opportunities at home. Sencirk helps them see those opportunities.

An older performer and teacher at Sencirk, Sammi, explains, “We can teach them how to work together, how to grow, to believe in themselves.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The grab-a-paintbrush approach to climate change

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Much of the world’s conversation about climate change rests on a premise of victimization. Big carbon-emitting nations are imperiling developing nations. Fossil fuel companies dupe governments and consumers. Today’s generation is harming tomorrow’s generation by its carbon addiction.

Yet another conversation is happening that shies away from grievance to what Amory Lovins, a longtime apostle of energy innovation, calls “applied hope.” This is a pragmatic conviction that individuals “acting out of hope can cultivate a different kind of world worth being hopeful about ... expressed and created moment by moment through our choices.”

This approach can be as deceptively simple as a can of paint. In Indonesia, for example, the San Francisco-based ClimateWorks Foundation has funded local projects to paint corrugated roofs with white reflective paint to cool homes and schools. In one factory, the paint reduced inside temperatures by 20 degrees Fahrenheit on the warmest days. The project by ClimateWorks represents a big shift among philanthropy groups toward grassroots adaptations geared to individual energy users.

The shift represents a new type of freedom, one that may yet help communities and governments act with new creativity and resolve.

The grab-a-paintbrush approach to climate change

Much of the world’s conversation about climate change rests on a premise of victimization. Big carbon-emitting nations are imperiling developing nations. Fossil fuel companies dupe governments and consumers. Today’s generation is harming tomorrow’s generation by its carbon addiction.

Yet another conversation is happening that shies away from grievance to what Amory Lovins, a longtime apostle of energy innovation, calls “applied hope.” This is a pragmatic conviction that individuals “acting out of hope can cultivate a different kind of world worth being hopeful about ... expressed and created moment by moment through our choices.”

This approach can be as deceptively simple as a can of paint. In Indonesia, for example, the San Francisco-based ClimateWorks Foundation has funded local projects to paint corrugated roofs with white reflective paint to cool homes and schools. In one factory, the paint reduced inside temperatures by 20 degrees Fahrenheit on the warmest days. That kind of cooling, scaled across the world’s hotter urban regions, represents massive potential savings in energy costs.

The project by ClimateWorks represents a big shift among philanthropy organizations. After decades of lobbying governments or backing ambitious high-tech solutions to mitigate climate change, these environmental leaders are refocusing on grassroots adaptations geared to individual energy users.

“I saw firsthand how the big climate funders were directing the vast majority of their grants,” said Erin Rogers, co-director of the Hive Fund for Climate and Gender Justice, in a recent interview with The Chronicle of Philanthropy. “It was a very siloed approach, a very insider, technocratic, policy-driven approach that I think we’ve all come to see is failing.” Climate change, she said, needs “solutions that are people-centered, more connected.”

Climate change philanthropy is suddenly flush with cash. Amazon founder Jeff Bezos created a $10 billion Earth Fund in 2020 and has already doled out more in grants in less than two years than ClimateWorks has in nearly two decades. Other billionaires and their foundations – such as former Google CEO Eric Schmidt; the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; Mr. Bezos’ former wife, MacKenzie Scott; and the Musk Foundation – have dedicated fortunes to promoting green energy and biodiversity. Nine funders pledged $5 billion toward addressing climate change at United Nations meetings last fall.

As this money is spent, its value may be measured less by the policies or technologies it promotes than by the extent to which it lifts individuals above the enormity of the challenge of climate change to a recognition of their ability to embrace new ways of thinking and acting.

“Sometimes a problem can’t be solved not because it’s too big, but because it was framed so narrowly that its boundaries don’t encompass the options, degrees of freedom, and synergies needed to solve it,” Dr. Lovins, a Stanford University professor, wrote in a recent tweet.

A shift like the one in climate philanthropy toward individual empowerment and a people-centered approach represents a new type of freedom, one that may yet help communities and governments act with new creativity and resolve.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Words that help and heal

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Karen Neff

It’s natural to want to help when we see conflict. Acknowledging God, divine Love, as the communicator of infinite goodness and grace opens our thinking to know what to say that will bring comfort to the individuals involved and healing to the situation.

Words that help and heal

Once when I worked in a framing shop, an expressionist artist brought in a painting of two individuals standing on either side of an unfinished brick wall, each holding a brick. The title of the painting was “Words.” I wondered out loud if the bricks symbolized words, and whether these words were building up the wall between them or tearing it down. With a twinkle in his eye the artist replied, “That’s for you to decide.”

Ah, the power of words! Mary Baker Eddy, a renowned spiritual healer, wrote of the power of words to heal when they come from a place of genuine caring: “The tender word and Christian encouragement of an invalid, pitiful patience with his fears and the removal of them, are better than hecatombs of gushing theories, stereotyped borrowed speeches, and the doling of arguments, which are but so many parodies on legitimate Christian Science, aflame with divine Love” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 367).

But what is it that inspires the words that help and heal? In my study and practice of Christian Science, I’ve found that God, divine Love, is the communicator, speaking not to the ear but to the heart. Because God is completely spiritual and good, His thoughts are only good. And as we earnestly seek to hear Him, we silence human will, and harshness, anger, and hurt are dissolved.

Even during conflict, we can prayerfully pause to hear the healing words of God and know how to speak them in a way that another’s heart can accept as well. Since we are all made in God’s image (see Genesis 1:27), everyone has the ability to feel and understand what God is communicating to us, and to find healing. It’s not just saying the words of spiritual truth that brings healing, but realizing these words are the manifestation of Truth, God, governing any situation.

Science and Health states, “Remember that the letter and mental argument are only human auxiliaries to aid in bringing thought into accord with the spirit of Truth and Love, which heals the sick and the sinner” (pp. 454-455). So, it isn’t so much what is said that heals, but what the heart understands as the spiritual reality of God’s love for us in action.

I once witnessed the power of spiritually inspired words when two individuals I knew had a falling out that was so severe they hadn’t spoken to each other for years. Any attempt I’d made to be a peacemaker was rebuffed. When all my efforts for reconciliation had failed, I realized it would take the grace of God – the touch of divine Love – to speak to each in a way that would soften and heal the hurt and anger.

As I have found at many times in my life, healing conflict begins with healing my own thinking first. In this instance, I prayed regularly that both individuals would feel the touch of God’s love.

One day I received a call from one of them asking me to speak to the other about getting together. While I was overjoyed by the humility it took for this individual to reach out, I was unsure as to how I could convince the other person to be receptive to a get-together.

I earnestly prayed for God to give me the words that would be accepted and that would tear down the wall that had existed for so long. What I came to realize was that God, who had revealed humility in the heart of one individual, had also prepared receptivity in the heart of the other.

The idea that I would not be speaking to a bitter, angry person, but would be addressing this person’s Godlike nature, created in God’s image, comforted me. The right words came, the invitation was graciously accepted, and a reconciliation took place that very day. That was years ago, and these friends have shared a deep and heartfelt love for one another ever since.

The same grace of God that restored this relationship can heal other issues as well, whether small or large. We can start with ourselves by asking, Are we flinging bricks of hurtful words at each other and building up walls of suspicion, hate, and prejudice? Or are we tearing down walls, through receptivity to the power of God, which opens the way for dialogue and healing?

I love this short, simple prayer: “Let the words of my mouth, and the meditation of my heart, be acceptable in thy sight, O Lord, my strength, and my redeemer” (Psalms 19:14). When the words come from God, there can be no doubt of a peaceful outcome.

For a regularly updated collection of insights relating to the war in Ukraine from the Christian Science Perspective column, click here.

A message of love

Winged beauty

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow. Staff writer Scott Peterson will be reporting from Ukraine about how two months of war and collective hardship is forging a unified national narrative.