- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Big Henry and the stereotypes we give dogs

Big Henry is a beagle who thinks he’s something else. A Labrador, maybe.

First of all, he’s big. Henry – our latest foster dog – is twice the size of other beagles. He can’t howl like a beagle. His barks sound like strangled yips.

And he doesn’t act like a beagle. He hip-checks you when he wants a pat, like big dogs do. He wriggles like a snake when he’s happy, like a Pekingese. He’s friendlier to dogs he doesn’t know than are many hounds.

Maybe he’s a mixed breed. But maybe we’ve also stereotyped him. A new study out this week from scientists who have long studied dog genetics finds that breed heritage has far less influence on canine personality than we think.

Chihuahuas perhaps aren’t inherently nervous. Golden retrievers may not all be mellow. Pit bulls might not be aggressive, unless taught to be.

“Dog breed is generally a poor predictor of individual behavior and should not be used to inform decisions relating to selection of a pet dog,” concluded the study, published Thursday in Science.

The research combined DNA sequencing of 2,000 dogs – purebred and mixed breed – and self-reported surveys from thousands of dog owners.

The results showed some general traits are inheritable, such as responsiveness to commands. But that inheritability didn’t distinguish breeds from one another. Breeds accounted for only 9% of behavior variation in individual dogs, according to the study.

Maybe that shouldn’t be surprising, given that breeds emerged only about 160 years ago – a blink in time compared with the overall 10,000-year history of dog species.

However, Henry is a true beagle in one respect. His nose. He sniffs everything. A walk around the block can take an hour.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

‘Chaos on top of a crisis’? Congress debates ending Title 42.

Both parties agree only Congress can fix the strained U.S. immigration system. But with Trump-era deportation tool Title 42 set to end next month amid a record influx, there is little agreement about potential solutions.

The border debate has taken on new urgency in Congress with the Biden administration’s decision to end a Trump-era deportation tool called Title 42.

Created at the start of the pandemic to allow border agents to quickly expel migrants on public health grounds, Title 42 has been used to thwart about half of attempted crossings between official ports of entry in recent months. On April 1, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced it would be lifted on May 23, although pending court action could delay that timeline.

Many Democrats believe it’s about time. “I wish it would have been done by the administration sooner,” said Sen. Ben Ray Luján of New Mexico.

But some are now joining Republicans in asking that Title 42 be extended until the Department of Homeland Security is better prepared to handle the expected influx. DHS estimates daily migrant encounters – already at an unprecedented high – could rise from 7,800 to as many as 18,000 per day.

“We already have a crisis at the border,” said Democratic Sen. Mark Kelly of Arizona, who’s up for reelection this fall. “I don’t want to see chaos on top of a crisis.”

‘Chaos on top of a crisis’? Congress debates ending Title 42.

Some 1,700 miles away from the Rio Grande, where Spc. Bishop Evans drowned trying to save migrants crossing into the United States last week, members of Congress opened a Homeland Security hearing Wednesday by mourning his loss.

But they disagreed about what his death symbolized. To Democrats, the Texas National Guard member’s sacrifice exemplified the humanity they’ve striven to restore after Trump-era immigration policies that Chairman Bennie Thompson called “a national disgrace.” To Republicans, it was a sign of how ineffective and imbalanced U.S. border policy has become, prioritizing the lives of migrants attempting to cross the border illegally over those tasked with securing it.

The border debate has taken on new urgency with the Biden administration’s decision to end next month a Trump-era deportation tool called Title 42. Despite clear differences in how the parties view the issue, a number of Democrats – many facing tough reelection races – have joined Republicans in voicing concerns about the planned repeal. But while political forces may lead to a short-term fix, both sides agree that it is essentially punting on the larger problems of border security and immigration reform, which have eluded Congress for decades, even as the pressure on the border grows.

Title 42 was created at the start of the pandemic to allow border agents to quickly expel migrants on public health grounds. It has been used to thwart about half of attempted crossings between official ports of entry in recent months. On April 1, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced that Title 42 would be lifted on May 23, although pending court action could delay that timeline.

Without it, DHS is bracing for daily encounters – already at an unprecedented high – to rise from 7,800 to as many as 18,000 per day. That could mean more than a million unauthorized immigrants entering the country within the first two months.

Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas found himself in the hot seat this week at several congressional hearings.

House Democrats praised him for his efforts to rebuild the department. But Rep. Michael Guest of Mississippi blamed the secretary for “the worst immigration crisis that our nation has ever seen” and said officials he’d met with on the border felt abandoned. “Are you testifying as you sit here today that the southwest border is secure?” the Republican asked.

“Yes, I am. And we are continuing to work to make it more secure,” said Secretary Mayorkas. He noted that the number of migrant encounters is higher than the number of unique individuals trying to cross, due to those making multiple attempts. And he defended the department’s handling of migrants as well as refugees, as the Ukraine war adds to global migration flows not seen since World War II.

“We are restoring our leadership as a country of refuge,” said Secretary Mayorkas, whose family fled to the U.S. from Cuba when he was young.

Public health as a fig leaf?

Many Democrats believe it’s about time Title 42 is repealed. “I wish it would have been done by the administration sooner. But nonetheless, I appreciate that effort,” said Sen. Ben Ray Luján of New Mexico.

Critics of Title 42 argue that it used public health as a fig leaf for justifying more stringent border control measures. “There is no public health rationale that supports the unlawful and discriminatory blocking and expulsion of people at our southern border,” wrote the ACLU New Mexico in a September letter to Secretary Mayorkas, which outlined alternative measures to address public health concerns and was signed by nearly a dozen state legislators.

But some Democrats are now asking President Joe Biden to extend Title 42 until DHS is better prepared to handle the expected influx. Earlier this month, five Senate Democrats joined GOP colleagues in co-sponsoring a bill to delay the repeal until at least 60 days after the president ends the national public health emergency. A similar bill in the House has 11 Democratic co-sponsors.

This week DHS sought to assuage concerns by releasing a memo outlining the preparations underway – increasing everything from the number of Border Patrol agents to the number of bus seats for transporting migrants, as well as improving processing efficiency and stepping up deportations of known criminals.

Many lawmakers were skeptical.

“A plan to just manage 18,000 people a day is not a plan,” said GOP Sen. Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia.

Democratic Sens. Maggie Hassan of New Hampshire and Mark Kelly of Arizona, both of whom are up for reelection, said the memo left them with more questions.

“It isn’t clear to me that they have the resources they need in place to actually implement the plan,” said Senator Hassan.

“There is a lot that would have to be put in place for me to get to the point where I would be comfortable lifting Title 42,” echoed Senator Kelly, a former U.S. Navy captain and astronaut. He and the mayor of Yuma, Arizona, had met the previous day trying to figure out where the extra migrants could be housed. A former Sears store, maybe? Could they erect a temporary facility across from the Border Patrol building – and how quickly?

Contrary to Secretary Mayorkas’ stance, the senator said the Arizona border is not secure.

“We already have a crisis at the border,” he said. “I don’t want to see chaos on top of a crisis.”

Many attempted crossings, but also repatriations

According to government data, fiscal year 2021 saw unusually high numbers of attempted violations as well as enforcement of U.S. border policies:

- U.S. Customs and Border Protection recorded 1.72 million encounters, a historic high. That’s only slightly above the previous record, in FY 2000, but for the past 15 years the annual total had been below a million.

- DHS also completed 1.2 million repatriations, the most since 2006.

- The government removed nearly twice as many migrants with aggravated felonies than in 2020, according to an ICE report.

- CBP seized more than twice as much fentanyl as the year before. The highly potent drug is blamed for a spike in U.S. overdoses, which in FY 2021 exceeded 100,000 for the first time. Many GOP senators pointed to those figures as evidence that the border crisis has become a national crisis. However, more than 90% of the fentanyl seized was found at official ports of entry, not by Border Patrol agents stopping migrants between those locations.

It’s a perennial question whether higher numbers of enforcement activities signal an increase in attempted crossings or more effective enforcement – or both. One new development is that while most migrants seeking to cross the southwestern border traditionally hailed from Mexico or Central America, now they are coming from more than 100 countries.

That may help explain why so far in FY 2022, which began in October, monthly encounters are up on average 83% year-on-year – including a recent spike in Ukrainians seeking asylum. After Russia invaded Ukraine, the Biden administration gave CBP permission to exempt Ukrainians from Title 42, which has led to accusations from some critics of a double standard.

As Congress debates whether increased funding would help DHS better enforce border policies, Republicans want more answers about how taxpayer funds are being used. They also would like the money to be deployed to deter migrants, not just deal with an influx.

Earlier this month, GOP senators held up a $10 billion COVID-19 relief bill over Title 42, arguing that the administration couldn’t declare the national health emergency over at the border while using it to justify more spending for other priorities. But the debate is about much more than public health.

A problem only Congress can solve

Florida Sen. Marco Rubio, whose family came to the U.S. from Cuba, says the changing global landscape requires a revamped immigration process, arguing that current policies empower trafficking groups. Such groups typically charge $4,000 to $10,000 per person to make the perilous journey, with some migrants pressured into sex trafficking or drug trafficking to pay their way, according to congressional testimony.

“There’s nothing compassionate about having an open border that is luring people to come to this country,” Senator Rubio says.

Many on both sides of the aisle agree that it’s only a question of time before Title 42 eventually ends – and there needs to be a more comprehensive solution in place. That, however, has eluded Congress for decades.

“We have a broken immigration system that we need to fix here in Congress. And we can do that and still secure our borders and provide the resources needed for border security,” says Democratic Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto of Nevada, who as a former attorney general worked on border issues, including trafficking. “They’re not mutually exclusive. You can do both.”

Beijing diary: Scenes of mass testing, panic buying – and pride?

After escaping Shanghai, the Monitor’s Beijing bureau chief is caught in yet another massive reaction to a COVID-19 outbreak. As case numbers grow, can the civic-minded capital tolerate a total lockdown?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

It was late Sunday night when I got a three-word text from a Chinese friend: “Buy more food!”

News spread that authorities seeking to contain a cluster of COVID-19 cases had sealed off several compounds and ordered mass testing in the district of 3.5 million people where I now live, and panic buying was in full swing. By the time I got to the local supermarket, all the carts were taken by frenzied customers and many vegetables were sold out.

The day before, I’d enjoyed my first taste of relative freedom in China since arriving in Shanghai in mid-March. Now, I had a sinking sense of déjà vu. After witnessing scenes of lockdown hardship in Shanghai, I had to wonder, could Beijing be next?

Many residents say no.

Even as Beijing’s cases reach an all-time pandemic high, Beijingers say the city’s special status and extra-stringent COVID-19 policy make a Shanghai-scale outbreak impossible. Indeed, food supplies were fully restored by midweek, as Beijing authorities increased shipments of fresh produce to quell residents’ worries and, possibly, to save face.

“It’s the capital, so it has to be stable politically,” says Julia Wang, a Beijing university teacher, adding that Beijing’s culture of civic-mindedness is also an asset. “People in Beijing can sacrifice,” she says.

Beijing diary: Scenes of mass testing, panic buying – and pride?

Panic buying was in full swing at my local supermarket in Beijing’s central Chaoyang District – all the carts were taken and many vegetables were sold out. Store clerks in green vests were snapping photos of frenzied customers, overloaded with bags of cabbage, eggs, and meat.

“Everyone is scared!” said one shopper. “Prices are going up!” exclaimed another.

It was late Sunday night, and I had rushed to the store after getting a three-word text from a Chinese friend: “Buy more food!” News spread that authorities seeking to contain a cluster of COVID-19 cases had sealed off several compounds and ordered mass testing in the district of 3.5 million people where I now live.

My mind was reeling. Just the day before I’d enjoyed my first taste of relative freedom in China following five weeks of quarantine since arriving in Shanghai in mid-March. Strolling down a street lined with blossoming plum trees, squinting in the sun, I felt a huge relief soaking in the city on my way to the Monitor’s Beijing bureau.

But now, as the fleeting respite gave way to urgent stockpiling, I had a sinking sense of déjà vu. After witnessing heartbreaking scenes of lockdown hardship in Shanghai, China’s glittering financial capital, I had to wonder, could Beijing, the political capital, be next?

“Trust Beijing”

The next morning, I awoke to the familiar sound of a bullhorn, as workers in white hazmat suits summoned all residents in my compound for mandatory COVID-19 testing.

After my test, I rushed out to pick up my press pass from the Foreign Ministry, several blocks away. Everywhere along the way, Beijingers were forming long, orderly lines for testing. Spotting some carrots at a tiny sidewalk grocer, I snapped them up.

Soon the Foreign Ministry’s giant silver convex structure came into view. Like other Beijing government edifices and monuments – from the ancient Forbidden City to the Great Hall of the People – it reminded me of the city’s historic status as China’s seat of power, and of the premium its leaders place on stability.

Already, Beijing has restricted inbound travel to insulate the capital from COVID-19 outbreaks in the provinces – and has discouraged its 21 million residents from leaving for the upcoming May Day holiday. Beijing’s special status and extra-stringent COVID-19 policy lead many residents to believe a Shanghai-scale outbreak simply can’t happen here, I discovered.

“Beijing will never let that happen. It’s the capital, so it has to be stable politically,” says Julia Wang, a Beijing university teacher, stopping to chat as she took her out-of-school kindergartner for a walk. “There’s no way the masses here won’t have food to eat, like in Shanghai,” she says, adding that she’s also stockpiled food.

Even as Beijing’s cases reach an all-time pandemic high – a tiny outbreak by global standards but one called “grim” by local health officials – Ms. Wang and other residents believe the city has the personnel and medical capacity to quickly bring them under control.

“The government will be prepared,” says Ms. Wang. “We have so many hospitals and makeshift hospitals, so even if something bad happens, we have the ability to solve the problem.”

Beijing’s culture is also an asset, she says, stressing that Beijingers pride themselves on civic-mindedness. “People in Beijing can sacrifice,” she says. “Trust Beijing.”

Balancing business, people, and pride

So far, however, Beijing’s outbreak continues to spread, with more than a dozen communities housing many thousands of residents who are now confined to their homes.

“My boss is locked down in Shunyi District” in northeastern Beijing, says Ms. Hu, a shop worker, asking to withhold her first name to protect her privacy. “Business is bad due to the pandemic,” she says, adding that she may have to relocate her photography shop.

While a Beijing lockdown would not cause as heavy an economic blow as that of Shanghai, it would further hamper the government’s effort to achieve its target of 5.5% gross domestic product growth this year.

Yet despite slowing economic growth and a rise in joblessness – with urban unemployment reaching 5.8% in March – China’s government has made clear it has no plans to abandon its zero-COVID-19 policy anytime soon.

The “life first” policy has succeeded in keeping the level of cases and deaths in China far lower than that in other countries – with fewer than 5,000 fatalities in China compared with nearly 1 million in the United States.

Despite her loss of business, Ms. Hu fully backs that approach. “I think it’s really good,” she says. “Being healthy is the most important.”

Back at the grocery store, food supplies were fully restored by midweek, as Beijing authorities rushed to increase shipments of fresh produce to quell residents’ worries.

“All this panic buying makes no sense,” says a clerk restocking the shelves. “Beijing definitely won’t be like Shanghai,” he adds, withholding his name for privacy.

Asked why he feels so certain, he sums up the pride of place that many Beijingers feel – and China’s preoccupation with “saving face” – in a couple of words:

“Beijing’s face!” he says, stroking his cheek with the back of his hand and letting out a laugh.

Basically, a lockdown in Shanghai is one thing; here, it would be an embarrassment.

How Europe’s data law could make the internet less toxic

A new EU law calls on Big Tech companies to open up their algorithmic “black boxes” and better moderate online speech. The goal is no less than preserving the public square on which democracies depend.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

A new European Union law aims to force social media giants including Facebook and YouTube to take steps to tamp down the spread of extremism and disinformation online.

Under the Digital Services Act (DSA), tech companies with more than 45 million users will have to give regulators access to their so-called algorithmic black boxes, revealing more about how certain posts – particularly the divisive ones – end up at the top of social media news feeds.

And if platforms recognize patterns that are causing harm and fail to act, they will face hefty fines.

“We need to get under the hood of platforms and look at the ways in which they are amplifying and spreading harmful content such as hate speech,” says Joe Westby, deputy director of Amnesty Tech in Brussels. “The DSA is a landmark law trying to hold these Big Tech companies to account.”

The law may end up having considerable effects on how corporations behave even in the United States. “This is a classic example of the ‘Brussels effect’: the idea that when Europe regulates, it ends up having a global impact,” says Brookings Institution expert Alex Engler.

How Europe’s data law could make the internet less toxic

Sweeping new European Union legislation seeks to “revolutionize” the internet, forcing social media giants including Facebook and YouTube to take steps to tamp down the spread of extremism and disinformation online.

Known as the Digital Services Act (DSA), it is likely to create ripple effects that could change how social media platforms behave in America, too.

In one of the most striking requirements of the new law, Big Tech companies with more than 45 million users will have to hand over access to their so-called algorithmic black boxes, lending greater clarity to how certain posts – particularly the divisive ones – end up at the top of social media news feeds.

Companies must also put in place systems designed to speed up how quickly illegal content is pulled from the web, prioritizing requests from “trusted flaggers.”

And if platforms recognize patterns that are causing harm and fail to act, they will face hefty fines.

“We need to get under the hood of platforms and look at the ways in which they are amplifying and spreading harmful content such as hate speech,” says Joe Westby, deputy director of Amnesty Tech at Amnesty International in London.

“The DSA is a landmark law trying to hold these Big Tech companies to account,” he adds.

Unlocking the Big Tech business model

Big Tech companies have long endeavored to shrug off regulation by invoking freedom of speech. The DSA takes the tack that while ugly and divisive speech shouldn’t be policed, neither should it be promoted – or artificially amplified.

But in order to sell ads and collect user data – which they also sell – the big online platforms have been doing precisely this.

The key to this business model is keeping users online for as long as possible, in order to collect as much data about them as possible.

And research has shown that what keeps people reading and clicking is content that makes them mad, notes Jan Penfrat, senior policy adviser at European Digital Rights, a Brussels-based association.

This in turn gives Big Tech companies incentive to prioritize and push out anger-inducing content that provokes users “to react and respond,” he says.

This point was driven home last year through a trove of internal documents made public by whistleblower and former Facebook data engineer Frances Haugen.

In leaked company communications, an employee laments that extremist political parties were celebrating Facebook’s algorithms, because they rewarded their “provocation strategies” on subjects ranging from racism to immigration and the welfare state.

It was one of many examples in those documents of how Facebook’s algorithms appeared to “artificially amplify” hate speech and disinformation.

To endeavor to fix this, the DSA will require Big Tech companies to conduct and publish annual “impact assessments,” which will examine their “ecosystem of users and whether or not – or how – recommendation algorithms direct traffic,” says Peter Chase, senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund in Brussels.

“It’s asking these large platforms to think about the social impact they have.”

There are insights to be had from these sorts of regular exercises, analysts say.

Twitter, which has a reputation for publishing self-critical research, made public an internal evaluation last October that found its own algorithms favor conservative rather than left-leaning political content.

What they couldn’t quite figure out, it admitted, was why.

The DSA aims to provide some clarity on this front by requiring Big Tech companies to open up their algorithmic black boxes to academic researchers approved by the European Commission.

In this way, EU officials hope to glean insights into, among other things, how Big Tech companies moderate and rank social media posts. “On what basis do they recommend certain types of content over others? Hide or demote it?” Mr. Penfrat asks.

And under the law, if Big Tech companies discover patterns of artificial amplification that favor hate speech and disinformation pushed out by bad actors and bots – what social media companies call “coordinated inauthentic behavior” – and don’t take action to stop it, they face devastating fines.

These could run up to 6% of a company’s global annual sales. Repeat offenders could be barred from operating in the EU.

“They have to do something about it, or they can get caught,” says Alex Angler, fellow in Governance Studies at the Brookings Institution.

“So they can’t just shrug their shoulders and say, ‘We don’t have a problem.’”

“Weaponized” ads – and the law’s response

Up until now, such evasiveness is precisely what has characterized Big Tech companies, and analysts say it’s largely because promoting divisive content has been so wildly profitable.

Mr. Penfrat recalls the surprise of EU policymakers he lobbied when he would explain the nearly unfathomable amount of personal data that tech giants commodify – and how they often tap the emotional power of anger through a “surveillance-based” advertising model.

“Every single time you open a website, hundreds of companies are bidding for your eyeballs,” he says. In a matter of “milliseconds,” the ads pushed by data brokers who have won the bid are loaded for web users to view.

But it’s not just goods and services that advertisers are selling. “Anyone can pay Facebook to promote certain types of content – that’s what ads are. It can be political and issues-based,” Mr. Penfrat says.

And bad actors have taken advantage of this, he notes, pointing to how the Russian government “weaponized” ads to push its preferred candidates in U.S. elections and justify war in Ukraine.

The DSA will ban using sensitive data, including race and religion, to target ads, and prohibit ads aimed at children as well. It also makes it illegal to use so-called dark patterns, manipulative practices that trick people into things such as consenting to let online companies track their data.

What’s more, it requires Big Tech companies to speed their processes for taking down illegal posts – including terrorist content, so-called revenge porn, and hate speech in some countries that ban it – in part by prioritizing the recommendations of “trusted flaggers,” which could include nonprofit groups approved by the EU.

Likewise, if companies remove content that they say violates these rules, they must notify people whose posts are taken down, explain why, and have appeals procedures.

“You’ve got these mechanisms today, but they’re very untransparent,” Mr. Penfrat says. “You can appeal but never get a response.”

A European law with U.S. effects

The DSA has been received by data-policy experts with a mix of skepticism as well as praise – with some voicing worry about unintended harm to competition or the diversity of online speech.

Yet the DSA is expected to drive policy in the United States as well as in Europe, says Mr. Engler, who studies the impact of data technologies on society.

“This is a classic example of the ‘Brussels effect’: the idea that when Europe regulates, it ends up having a global impact,” he adds. “Platforms don’t want to build different infrastructure based on whether the IP address is in Europe.”

And as academics are able to delve into Big Tech’s black boxes, the mitigating measures they suggest will not only be a good starting point for public debate, but could also provide inspiration for America, too.

During Ms. Haugen’s whistleblower testimony, U.S. lawmakers signaled that they could be open to the sorts of regulations that the DSA puts in place.

At a press conference following the congressional testimony last October, Sen. Richard Blumenthal, a Connecticut Democrat, marveled at the bipartisan agreement on the need for reform.

“If you closed your eyes, you wouldn’t even know if it was a Republican or a Democrat” speaking, he said. “Every part of the country has the harms that are inflicted by Facebook and Instagram.”

American and European regulators say this is true on both sides of the Atlantic.

Commentary

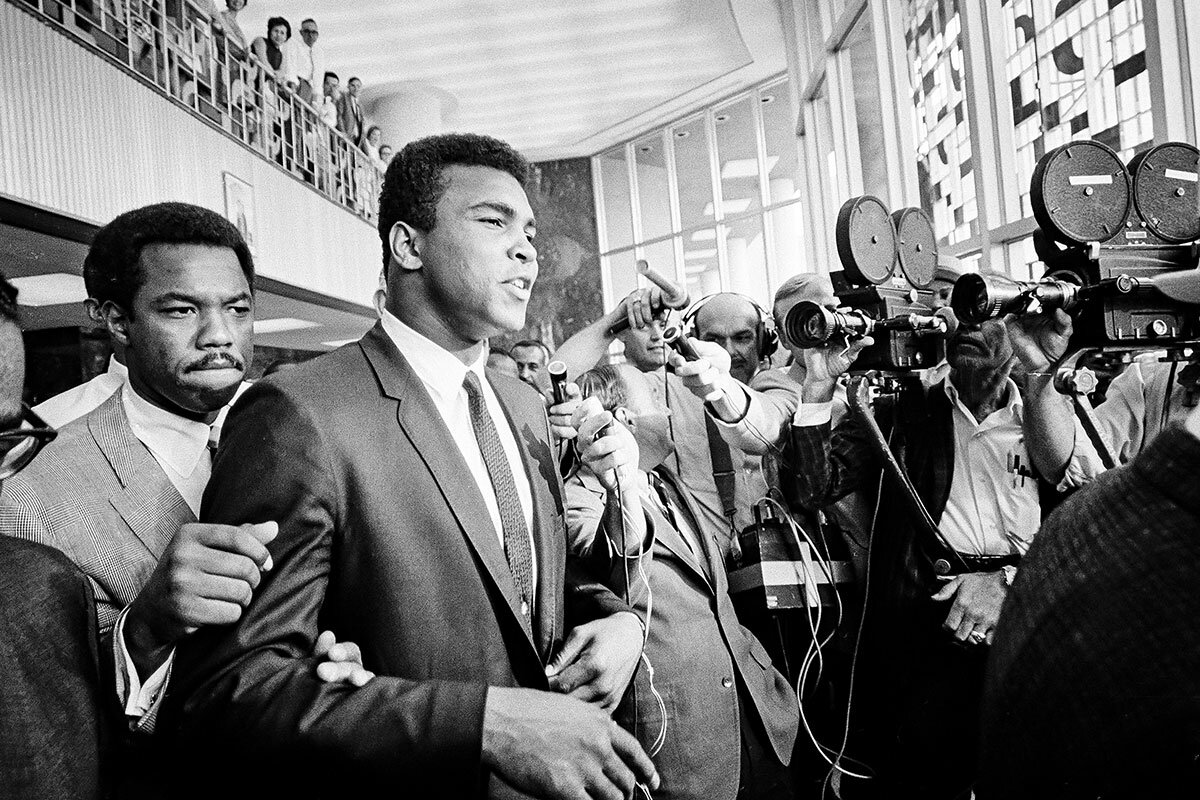

What Muhammad Ali’s conviction can teach us today

Being true to one’s ideals sometimes comes at a high cost. Muhammad Ali’s anti-war stance lost him years of his prime as a boxer, but his conviction made him timeless.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Fifty-five years ago this week, world heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali refused to be drafted into the United States Army to fight in the Vietnam War. “It is in the light of my consciousness as a Muslim minister and my own personal convictions that I take my stand in rejecting the call to be inducted,” he offered in a statement.

Ali was immediately stripped of his boxing title, and, a few months later, convicted of draft evasion, fined $10,000, sentenced to five years in prison, and banned from boxing. The punishment would rob him of his boxing prime, but what he forfeited in terms of his career, he gained in conscience and celebrity.

“My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America,” he had said a year before his refusal to join the Army.

Finally, in June of 1971, his conviction was overturned.

Conviction – a word that threatened to derail Ali’s career actually showed us the heart of “The Greatest.” As the world around us seems to be falling apart, Ali’s legendary stance continues to ring loud as a call for not only conscience, but courage.

What Muhammad Ali’s conviction can teach us today

Some of Muhammad Ali’s greatest battles were fought within the realm of mythology. There was the time Ali faced off (in a comic book) against the son of Krypton, Superman. And who could forget his “battle” with nature, which he described with compelling wit as a precursor to his fight with George Foreman:

I have wrastled with a alligator. I done tussled with a whale. I done handcuffed lightning, throwed thunder in jail. That’s bad! Only last week, I murdered a rock, injured a stone, hospitalized a brick. I’m so mean, I make medicine sick.

At the height of his powers, Ali’s mythos was as impenetrable as his boxing record. It’s hard to imagine that someone so deft of foot and wit could contain something even more indomitable, but that was Ali’s true gift. His conviction was undeniable, even in the midst of his greatest battle, one that wasn’t imaginary, but ideological.

On April 28, 1967, 55 years ago this week, Ali refused to be drafted into the United States Army to fight in the Vietnam War. His Muslim faith and his anti-war commentary came to a head when he arrived in Houston for his scheduled induction. He refused to step forward when his name was called and was told that he would be arrested if he continued to refuse. A man known for his trademark shuffle stood firm that day.

“It is in the light of my consciousness as a Muslim minister and my own personal convictions that I take my stand in rejecting the call to be inducted,” he offered in a statement.

Ali was immediately stripped of his world heavyweight championship, and a few months later, on June 20, 1967, he was convicted of draft evasion, fined $10,000, and sentenced to five years in prison. He was also banned from boxing for three years. The punishment would rob him of his boxing prime, but what he forfeited in terms of his career, he gained in conscience and celebrity.

Those two terms might seem contradictory, especially considering the allure of capitalism. That was the power of Ali, though – even in a room full of luminaries, his conscience was the center of attention. Take the “Ali Summit,” for example, which included sports legends such as Bill Russell, Jim Brown, and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. The group met in Cleveland a few weeks before Ali’s conviction in an effort to get him to soften his anti-war stance. When he wouldn’t, Ali’s fellow athletes stood with him.

“I envy Muhammad Ali. He faces a possible five years in jail and he has been stripped of his heavyweight championship, but I still envy him,” Mr. Russell said. “He has something I have never been able to attain and something very few people I know possess. He has an absolute and sincere faith. I’m not worried about Muhammad Ali. He is better equipped than anyone I know to withstand the trials in store for him. What I’m worried about is the rest of us.”

Mr. Russell’s words were prescient, not just for that time, but for the present age. Partisan politics and the pandemic have torn the United States apart. What might redeem us all is unrepentant and conscious faith. Some might have considered Ali unpatriotic, but his love for people of all walks of life was undeniable. As a result, his stance didn’t just exalt him beyond celebrity – it ultimately made him the people’s champion.

When he declared, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong,” the anti-war sentiment became a rallying cry for Black people. A year before his rebuke of the military, he offered this pointed take on Vietnam:

My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America. And shoot them for what? They never called me [racial epithet], they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me, they didn’t rob me of my nationality, rape and kill my mother and father. ... Shoot them for what? How can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail.

Protesters took Ali’s sentiment and offered this message: “No Vietnamese ever called me [racial epithet].” The commentary was edgy and effective as it made its way across college campuses, as did Ali himself. In October 1970, he finally secured a boxing license to take on Jerry Quarry, and in June of 1971, his original conviction was overturned by the Supreme Court.

Conviction – a word that threatened to derail Ali’s career actually showed us the heart of “The Greatest.”

Anti-war sentiments are still relevant, particularly with the world’s eye on Ukraine, and, in less-reported news, a U.S. military proposal to recruit college athletes under consideration.

As the world around us seems to be falling apart, Ali’s legendary stance continues to ring loud as a call for not only conscience, but courage.

This take on women’s independence packs a (peppery) punch

The spicy condiment harissa is such a valued staple in Tunisia that it created an opportunity for skilled rural women to work together to gain more security, equity, and financial independence.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

In Tunisia’s pepper-growing region 125 miles south of Tunis, women have relied on farming and harvesting chile peppers on other people’s lands for generations. The peppers were sent to factories in the capital that churned out the harissa served on tables across the country.

Smokey, savory, and packing a punch, the bright crimson pepper paste has long been a culinary do-all for Tunisians. Harissa is such a staple that Tunisia petitioned UNESCO in 2020 to add the condiment to the world’s intangible cultural heritage list.

But working on other people’s farms was a hard life for the women. Long hours, dangerous commutes, meager wages. Seven years ago, Najwa Dhaflawi had had enough. Her answer: band women together to produce their very own harissa, free of middle-men – or any men.

She created Errim, an all-rural-women’s cooperative through which village women plant, cultivate, and harvest the peppers, then produce harissa themselves. The business has created a peppery path to independence.

“We were tired of being taken advantage of,” Ms. Dhaflawi says as workers prep for the next bushel of peppers in the cooperative’s spotless workshop. “We wanted to work in a safe environment; to protect one another. And to be paid fair wages.”

This take on women’s independence packs a (peppery) punch

Smoky, savory, and packing a punch, the bright crimson pepper paste has long been a culinary do-all for Tunisians.

Harissa adds spice to soup and sizzle to sandwiches, turns couscous caliente, and can serve simply as a fiery dip.

Often eaten twice a day, harissa is such a staple in Tunisia that the government petitioned UNESCO in 2020 to add the condiment to the world’s intangible cultural heritage list.

But for Najwa Dhaflawi and the rural women of Kairouan in central Tunisia, harissa has meant something more – a peppery path to independence.

In the village of Menzel Mehiri, 125 miles south of Tunis in the heart of Tunisia’s pepper belt, women have relied on farming and harvesting the chile peppers on other people’s lands for generations. The peppers were sent to factories in the capital that churned out the harissa served on tables across the country.

It is grueling work, with 3:30 a.m. starts and long hours toiling in the sun.

But the worst, residents say, was the commute. Female workers were packed in the open beds of pickup trucks, which, due to their unlawful seating arrangements, were driven too fast and went off-road to avoid the police, sometimes accidentally sending farmhands out of the truck and to their deaths.

“Every week on the way to work in the fields, there would be at least one incident where I almost died,” says veteran pepper picker Khansah Dhaflawi, Najwa’s older sister. “I’ve seen women get injured so bad you would swear off farming forever. But there is no other work to be had.”

Seven years ago, Najwa Dhaflawi had had enough. Her answer: band women together to produce their very own harissa, free of middle-men – or any men.

She created Errim, Arabic for gazelle*, an all-rural-women’s cooperative through which village women plant, cultivate, and harvest peppers, then dry them in their homes and produce the harissa themselves in their own workshop. The cooperative solved the hazardous commute problem primarily by working more locally, but also by arranging safer modes of transportation to the few farms that are not within walking distance.

“We were tired of being taken advantage of,” Ms. Dhaflawi says as workers in scrubs and face masks prep for the next bushel in Errim’s spotless, laboratory-like workshop. “We wanted to work in a safe environment, to protect one another. And to be paid fair wages.”

Cooperatives like this were banned in the days of dictator Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali. Ms. Dhaflawi modeled the cooperative on organizations she saw sprout up in the capital in the wake of the 2011 Arab Spring.

On this day, dozens of jars of Errim’s freshly produced harissa are placed in crates bound for grocery stores, boutique shops, and tourist restaurants along Tunisia’s coast, as well as for export to France and Switzerland.

With about two pounds of peppers making a pound of harissa, the workshop produces more than 400 pounds of the condiment a day.

Many residents jumped at the chance to work for a local woman. Errim has now grown to include 164 women from the area, benefiting families on each rung in the supply chain, from veteran pepper pickers to women who otherwise could not find work.

“There was no way my husband would allow me to work on the farms – it wasn’t safe – even though we needed the money,” says Nijat al-Bulti, a mother of two, as she places soaked peppers into an industrial grinder. “This project was a lifeline. It’s a clean and safe workplace I can walk to.”

This year Errim is using its profits to buy and rent nearby land plots for sharecropping, paying farm owners better prices and terms than the big corporations.

After years of watching big agro dominate their lands, these women are reclaiming dozens of acres of Kairouan’s farmland for themselves.

“The key to our success is local; I am using everything from Kairouan. The objective of the project is to give value to simple, natural products and bring back value to the community,” Ms. Dhaflawi says as she walks between rows of evergreen pepper crops on an adjacent sandy plot. “It’s a chain – the benefits reach each person in the process.”

Although Ms. Dhaflawi and her workers refuse to give away their secret recipe, the main ingredients are familiar to Tunisians: sun-dried peppers, coriander seeds, ground caraway, garlic, and olive oil – all locally grown.

And the taste?

Ms. Dhaflawi insists that her smoky-smooth harissa is mild. At least, by Kairouan standards.

Depending on your threshold, you can scoop bread into dollops of their prize-winning harissa drizzled with olive oil and submerge your tastebuds with the garlic-infused spice. For those with less indestructible palates, a little dab will do.

After managing to stay afloat amid two years of pandemic shutdowns – one of the benefits of an all-local production line – the women now have their eyes on expanding their exports to take advantage of harissa’s growing foodie profile in the West.

Meanwhile, they are maintaining an affordable price of $1.60 per jar for Tunisians mired in an economic recession at home.

“If the harissa stops, our lives will stop,” cooperative member Najat Shawabi says as she packs the last of the day’s jars into a crate.

Ms. Dhaflawi insists these rural women have no intention of slowing down.

“We now know independence, that we can rely on ourselves,” she says. “We will never look back.”

Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct the Arabic translation for the word "errim." It means gazelle.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Expecting the best of local officials

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

When global corruption watchdogs assess a country’s levels of official integrity, one important factor they measure is perception. That is because public expectations of good or bad reflect how societies define moral behavior. One approach to addressing high perceptions of corruption is social audits, which empower citizens to hold officials accountable by reporting abuses of public trust like embezzlement or demands for bribes.

Social audits have gained traction among a wide range of countries, but in countries where corruption is rife, it can take years to develop the tools and public confidence to make them effective. India’s gradual progress in establishing social audits shows why. The country has grappled with persistently high perceptions of corruption for decades.

Progress toward transparency through tools like social audits is about more than rooting out official dishonesty. The more important effect of such efforts is the building of an expectation of good.

Expecting the best of local officials

When global corruption watchdogs assess a country’s levels of official integrity, one important factor they measure is perception. That is because public expectations of good or bad reflect how societies define moral behavior. “High levels of corruption perception could have more devastating effects than corruption itself,” a study in Uruguay concluded, leading to a “culture of distrust” and a breakdown in “the relationships among individuals, institutions, and states.”

One approach to addressing high negative perceptions of corruption is social audits, which empower citizens to hold officials accountable by reporting abuses of public trust like embezzlement or demands for bribes. The idea is also evolving as a means for consumers, investors, and employees to gauge the ethics and financial integrity of corporations as well as their commitments to environmental goals such as carbon reduction.

Social audits have gained traction among a wide range of countries, from those with high degrees of public trust like Norway to those with high perceptions of corruption like Peru. But in countries where corruption is rife, it can take years to develop the tools and public confidence to make them effective. India’s gradual progress in establishing social audits shows why.

The country has grappled with persistently high perceptions of corruption for decades. The latest survey by Transparency International found that 89% of people think corruption in government is “a big problem.” In 2005 India passed a law establishing a comprehensive, nationwide provision for social audits. Earlier this month the government announced that it would begin requiring social audits of government-owned enterprises and private companies to promote social responsibility norms. It has instructed India’s Securities and Exchange Board and Institute of Chartered Accountants to establish new standards for social audits.

The 2005 law enables citizens to report if they have been improperly denied public services or experienced attempts by public officials or businesses to coerce bribes. That is supposed to trigger public hearings where both parties meet, often without an immediate threat of reprisal, to discuss and resolve their disputes. Social audits can cover government programs such as education, child nutrition and juvenile justice.

But efforts over the past 17 years to make social audits a standard practice have run into stiff resistance, particularly from so-called “frontline bureaucrats”—local village leaders and elected elites—who are most directly responsible for rendering public services. As the Global Anticorruption Blog pointed out this week, it required orders from the Supreme Court in 2018 to get individual states to begin to carry out national mandates under the 2005 law. Only 16 of 28 states have social audit administrations, and just two have independent enforcement agencies.

Even so, the idea is gaining momentum. In March the Ministry of Rural Development signaled that as of April 1, funding allocated to states for a plan that guarantees 100 days of paid, unskilled work for every rural family would be contingent on whether states had appointed social audit ombudsmen in each district.

“The social audits and the appointment of ombudsmen are good steps for better and transparent implementation of the [rural jobs] scheme,” labor rights activist Nikhil Dey told the Telegraph of India. “The government should ensure the states follow these measures.”

In countries like India where perceptions of corruption are rife, progress toward transparency through tools like social audits is about more than rooting out official dishonesty. The more important effect of such efforts is the building of an expectation of good.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

A healing response to culture wars

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Curtis Wahlberg

Is antagonism inevitable when opinions differ? Recognizing that we are all God-empowered to express patience and grace is a firm foundation for harmony and progress.

A healing response to culture wars

All too often, culture wars are dividing society today. Encyclopedia.com describes the situation as, “the body politic is rent by a cultural conflict in which values, moral codes, and lifestyles are the primary objects of contention.” And it’s big stuff lately. In the news, at the kitchen table, during school board meetings, even in churches, we see antagonism relating to significant differences of opinion about behaviors and norms.

Yet, there’s a way forward. The answer has to do with God, who doesn’t establish battles, but brings forth beauty and helpful activity in all of us. God is divine Spirit and Mind, the infinite source of wonderful, creative ideas that enable a harmoniously functioning universe. As expressions of God, which is the true nature of all of us, we are created to come together in productive ways.

My experience as a parent has taught me a lot on this subject. It’s problematic trying to move the kids to certain positions on issues through willpower. Time and again, what’s been most helpful is to focus on being a witness to and support of what’s coming forward in them of God. To affirm that they are spiritual in nature, that what defines them and their lives are the spiritual qualities of God expressed in them. This includes grace, purpose, completeness, and intelligence.

We are all expressions of what God, good, is. The God-inspired response in any situation is to identify ourselves and others as spiritual, moved and defined by the divine Spirit, rather than by self-righteousness, anger, or willfulness. Our daily lives involve exposure to the stir of the world, but what really defines us are the God-given patience, love, and grace that we bring to any moment.

Life in fact is about God, whose entirely spiritual and good nature keeps coming forth. Everything we really need is already a part of what we are as children of God. So we don’t need to battle with others to establish right positions, but we can find this good essence within one another. What we are, God has assured and is doing in us. As we feel this completeness, a sense of vulnerability and willfulness falls away.

The need, then, is to feel what God is bringing forth and be productive in expressing this. This doesn’t mean we all have to agree on every issue. But with this approach, rather than being hung up on a particular agenda, we’re bringing the peace that helps move everyone along with the helpful stuff we can do. And I’ve found that things get worked out from there.

The essential cause of inharmony, including culture wars, is the notion that we are governed not by God, but by atoms and circumstances that clash with those of others. From this basis, we would forever be divided without anything to unite us. But we can see through this material, limited view of ourselves and understand how the divine Spirit set up the universe. Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, wrote, “When the divine precepts are understood, they unfold the foundation of fellowship, in which one mind is not at war with another, but all have one Spirit, God, one intelligent source, in accordance with the Scriptural command: ‘Let this Mind be in you, which was also in Christ Jesus’” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 276).

The divine Mind moves us today to patiently find within ourselves and everyone else more of the divine qualities God has given us all. And so we find the way together past inharmony and on to the life we have of God to share.

For a regularly updated collection of insights relating to the war in Ukraine from the Christian Science Perspective column, click here.

A message of love

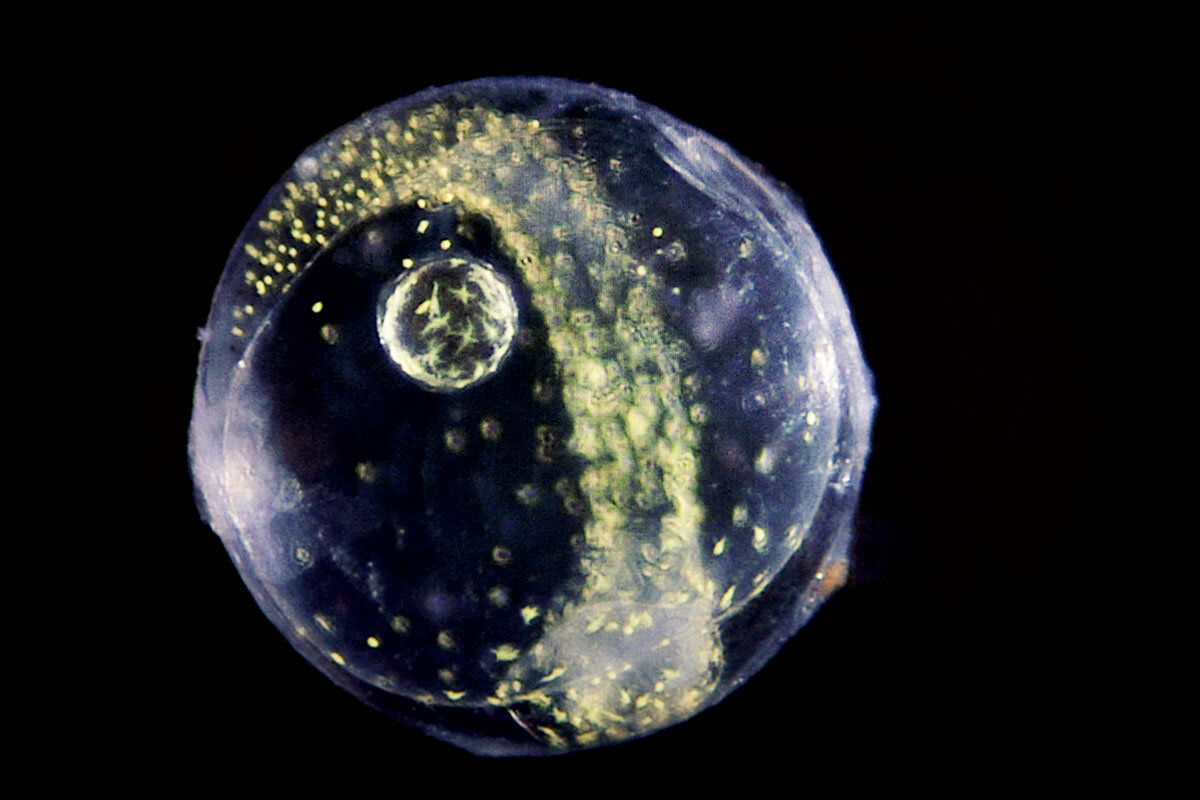

Dive into the tropical fish nursery of the future

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back Monday, when we’ll have a deep dive into the future of cities, post-pandemic.