- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 14 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

‘Aren’t Russians feeling it?’ Sanctions and daily life.

Fred Weir, as many Monitor readers know, has witnessed Russia’s modern history up close. He moved to the country when it was still the USSR. He watched Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev institute glasnost (“openness”), the Soviet state collapse in 1991, and street fighting break out in Moscow in 1993 amid a constitutional crisis. Not long after, he began to chart the rise of Vladimir Putin.

Fred has seen uneasy times, including those when Russians struggled with sharply reduced living conditions. Now, he’s being asked about the impact of heavy sanctions in response to the Ukraine invasion. “People want to know: ‘Aren’t Russians feeling it?’” Fred says.

That’s the subject of his story today. Fred says he’s found little sign of disruption for average Russians, be it in Moscow or well beyond – witness the well-stocked village grocery store Fred visited 60 miles away. A strong agricultural sector, he explains, means there’s plenty of the foodstuffs Russians expect to find, from cabbage and carrots to buckwheat. Prices are rising, but not in a game-changing way. Consumer goods are plentiful, at least for now.

At work, professionals have seen more varying effects: While some, including Fred’s wife, who works in the fashion industry, have experienced considerable disruption, others, such as IT workers, are finding opportunities as bigger players exit.

Where Fred sees the impact most clearly is in private conversations, in the sharing of views he encapsulates as: “We’re in it, so Russia has to win, but this is awful, and we’ll be paying for this for the rest of our lives.”

That “payment” comes, at least for many professionals, in being cut off from the world – meaning the West. It’s also about family separation: children abroad and decisions about whether they should come home, or family members who may be drafted should the war expand.

Still, Fred points out, Russians have a well-honed sense of how to make do. “Russia is not a gas station masquerading as a country,” Fred says, contradicting a characterization by the late Sen. John McCain. “They have a more diverse economy. And that experience of self-sufficiency is well understood.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Post-pandemic city: Can downtowns make a comeback?

What defines the heart of a city? For more than a century, urban communities prized and prioritized downtown business districts. The rise of work-from-home culture during the pandemic is forcing a rethink.

-

Patrik Jonsson Staff writer

-

Tara Adhikari Staff writer

-

Alexander Thompson Staff writer

Jordan Cohen never thought he could really feel at home outside Manhattan. “The city is just very viscerally in my DNA,” says the marketing executive. His family first settled in New York over a century ago, when his grandparents arrived at Ellis Island.

Then the pandemic hit and, almost to their surprise, he and his wife both found they could do their jobs quite seamlessly from home. So they decided to move to Maine, and within a few months had bought an old Dutch colonial. "We don’t plan on returning to NYC or city life again,” he says.

From the “Great Resignation” to the “Zoom Revolution” to the nationwide housing boom, the legacies of the pandemic are in many ways helping to redefine the meaning of urban life. In most major American cities, fewer than half of office workers are returning to their desks each day. For cities, this means empty offices, shuttered storefronts, cash-strapped subways, and lost tax revenues that are forcing officials to cut services.

Our reporting team visits four U.S. cities – New York, Atlanta, St. Louis, and Boston – where dramatic shifts in commuter traffic are prompting city leaders to reconsider what downtown should be.

Post-pandemic city: Can downtowns make a comeback?

Before the pandemic, Jordan Cohen always thought it would be difficult to leave Manhattan for good.

His work as a marketing executive in technology required the city’s concentration of business talent and the intensity of its famously frenetic business culture.

And as a born-and-raised Manhattan kid, Mr. Cohen says, “the city is just very viscerally in my DNA.” His great-grandparents arrived at Ellis Island over a century ago, and like them and his parents, he grew up in a cramped downtown apartment, coming of age during one of the city’s “mean streets” eras. He took graffiti-covered subways to his high school in the Bronx.

He did leave New York for college, and spent a year working in San Francisco. “But the West Coast just didn’t jibe with my East-Coast-city-kid personality,” he says. So he moved back home, found a 300-square-foot studio, and devoted himself to his career, witnessing New York’s transformation into a global tech hub and one of the safest big cities in the world.

He changed with it, too, working his way to an executive suite, getting married, and moving to a high-rise apartment with a city view. Still, over the years, both he and his wife, Elisabeth, a sales executive for a global technology firm, found that their city-that-never-sleeps lifestyles were starting to weigh on them.

Then the pandemic hit and, almost to their surprise, they found they could do their jobs quite seamlessly from home. So they decided to move to Maine, and within a few months had bought an old Dutch colonial in the salt-scented harbor town of Camden.

“I mean, this is the first time, at age 40 – this was the first time I ever lived in a house,” says Mr. Cohen, who left his job in Manhattan and started his own marketing company, The Fox Hill Group, from a home office with mountain views. “Who knows what the future holds, but we don’t plan on returning to NYC or city life again.”

From the “Great Resignation” to the “Zoom Revolution” to the nationwide housing boom, the legacies of the pandemic are in many ways helping to redefine the meaning of urban life. The ability to work remotely has begun to change the geographies, if not the sensibilities, of millions of lives and careers, especially in America’s major cities.

Five million people have already moved during the pandemic, and according to economic surveys, an estimated 14 million to 23 million more Americans are saying they are likely to move as well as they become unmoored from their offices, especially those in urban business districts.

“Today’s COVID-precipitated crises may well prove to be the most transformative event that America has experienced since the great migration to the suburbs after World War II,” says Richard Florida, a leading urban thinker.

In most major American cities, fewer than half of office workers are returning to their desks each day, including those with hybrid schedules. Only 36% of office workers in the New York metro area were back at their desks at the start of April, according to Kastle Systems, which measures keycard swipes in buildings it serves in 10 major cities.

For cities, this is a problem. Empty offices bring a series of cascading effects. Storefronts shutter, already cash-strapped transportation systems lose revenue, and tax bases shrink, forcing officials to cut services.

In New York, subways and buses were carrying only 60% of their pre-pandemic riders at the start of April. Restaurant reservations remain 40% below pre-pandemic norms. And the city has lost up to a third of its small businesses for good, experts say, which helps explain why its unemployment rate continues to hover above 7% – double the national average.

With tough times and urban ennui come disorder. Indeed, crime has skyrocketed in New York and many cities across the nation over the course of the two-year pandemic, compounding the challenge of luring back

office-shy workers.

Local leaders have urged workers to return, sometimes with notes of irritation and sarcasm.

“You can’t tell me you’re afraid of COVID on Monday and I see you in a nightclub on Sunday,” Mayor Eric Adams said earlier this year. “That accountant that’s not in his office space is not going to the cleaners, is not going to the restaurant, is not allowing the cooks, the waiters, the dishwashers [to return to work]. It’s time to open our state and our city and show the country the resiliency of who we are.”

But even some of these workers aren’t anxious to return to their former grind. Meyin Chan, an immigrant from Ecuador who lives in the Bronx, used to take the subway more than an hour each way to her job at a hotel in Times Square, where she managed a staff of eight handling reservations. A week after the city shut down, the hotel dismissed most of its staff.

The past two years have been especially difficult for the mother of two. Even if her old job were to return, she’s not certain what she would do.

“You know, I don’t want to go to Manhattan anymore,” she says. “Maybe because I’m too old to commute that long. ... I mean, something happened with me.”

Still, even if the pandemic is disrupting lives and livelihoods, it is also spurring cities to search for ways to reinvent themselves, just as many did decades ago when factories closed or moved overseas.

“I kind of think we misthought central business districts as simply arenas for office work,” says Dr. Florida, who is a professor at the University of Toronto’s School of Cities. With their sterile concentrations of skyscrapers, dearth of residences, and lack of activity at night, they are in many ways “the last remaining holdover of the Industrial Revolution,” he says.

Most cities have been designed around business districts and the office workers that commute in each day. Roads and public transportation systems have catered to these in-and-out flows. An economic ecosystem of shops and restaurants grew up to serve the commuters.

Urban planners have thought about this for years. Many now envision what they call a “15-minute city” in which every resident would be within a 15-minute walk or bike ride from anything they need, including parks and open spaces.

Central business districts need to be re-imagined as more of an “essential lifestyle district” or a “central culture district,” says Sofia Song, global cities lead for Gensler, an architecture and design firm. “It would be designed to be something that is much more connected, much more diverse, and which would make it a lot more resilient,” Ms. Song says.

Indeed, as the work-from-home trend takes hold, not everyone is looking for a rural idyll or suburban house with a yard. Millions still prefer an urban lifestyle – but in more livable cities, Gensler surveys find. Urbanites want shorter commutes, and access to more green space, as well as safe, affordable places to live.

A number of cities are already sketching plans and making changes for a post-pandemic reality. And one common theme is that traditional office districts may no longer be as central to their downtown cores.

ATLANTA – Abdul Seck has always had a straight-shot view of Atlanta’s Broad Street and its gentle rise up to the city’s downtown district on Peachtree Street.

A purveyor of fine handbags and scented oils at his kiosk here for 20 years, Mr. Seck, whose slightly brooding demeanor gives way to an easy smile, has watched the pulse of Atlanta’s city center ebb and flow as it followed the rhythms of the local economy.

But the past two years have been unusual as Atlanta, like many other major American cities, has seen its central business districts hollow out. Car trips downtown are still down 16% since before the pandemic. Streetcars run past his stall, but remain mostly empty.

Foot traffic, the lifeblood of his business, has also dissipated. Far fewer office workers, tourists, and local Georgians now fill the city’s streets. Boarded-up storefronts tell the tale of the pandemic’s downtown economic toll. Even the nearby McDonald’s and Burger King are gone. “There’s no money. Things are tough,” he says.

It’s a familiar refrain: Office vacancies, already a problem in 2018 when the city was wrestling with 4.8 million square feet of empty office space, jumped to nearly 11 million in the first three months of 2022 – about 15% of Atlanta’s office space total, according to a CoStar Analytics report.

Yet for all the lack of pedestrian traffic now, Mr. Seck can hear the bulldozers around the corner in an area known as “The Gulch” – a vast former rail yard, bracketed by aging viaducts, that is being converted into a mixed-use space of parks, housing, and retail.

City planners and developers see the pandemic-induced malaise here, as well as in much of urban America, as an opportunity not only to transform downtown districts, but also to introduce new values. Instead of viewing an urban center as simply a concentration of office buildings, they want to put more emphasis on a city’s history and identity – a place where people work, yes, but also live and connect with each other.

Developers in Atlanta have already begun to re-imagine downtown. Condos are going to be added to the signature Peachtree Center office tower. The project at The Gulch includes retrofitting the railroad’s former headquarters into a complex of mixed-income apartments and public parks called Centennial Yards.

Around the corner from Mr. Seck’s stall, developers are starting to rehabilitate an area known as Hotel Row. One abandoned tower is slated to become an apartment complex, which will include 300-square-foot studios – an effort to make housing affordable and bring economic diversity to the area.

“There are competing zeitgeists right now,” says Gene Kansas, who runs a commercial real estate firm. “On one hand, you have the globalization or the Las Vegas-ization of this country. The other is to, ‘just make it real, please. Make it genuine.’ There are a lot of people in Atlanta right now who realize the value of the preservation of history and that people want that.”

Adam Crawford, an Atlanta native, has watched the emerging changes through his picture windows at Cat Eye Creative, an art gallery on Mitchell Street that he opened in January 2021 inside a former drug store.

“Some people gave up” after the pandemic hollowed out Atlanta’s downtown, he says. “Others capitalized.”

As developers seek to repurpose some of the city’s historic buildings, local preservationist David Mitchell sees the post-pandemic future of Atlanta’s downtown district as “our moment.”

“Everything in Atlanta is a story. ... So you have to embrace a certain level of Atlanta identity and culture,” says Mr. Mitchell, the executive director of the Atlanta Preservation Center.

Longtime resident June Moore is concerned that the identity of the city will change as newcomers arrive. She takes a bus nearly every day downtown, whether to shop, do errands, or socialize.

She complains that the city’s transportation system has become erratic, given its lingering staffing problems and dwindling ridership. But she also acknowledges that part of the charm of downtown Atlanta is its ability to be a canvas for newcomers to paint new lives.

“Atlanta is what you make of it,” she says. “That may be even more true after the pandemic.”

ST. LOUIS – Veronica Holden, co-owner of La Mancha Coffeehouse in a northern neighborhood of St. Louis, doesn’t feel good about the pandemic’s effect on her city, for very personal reasons. She’s mixing a drink behind the counter on a Wednesday afternoon – the day before her business is set to shut down permanently.

A lone customer sits at a table in what was once a thriving local haunt, an intimate space that featured artwork by local painters and offered a place for people to mingle, espressos in hand.

“St. Louis has been rocked by a lot of different things,” says Ms. Holden, recalling the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014. But “we had always been able to kind of bounce back.”

About a mile and a half outside St. Louis’ downtown business district, this neighborhood shop is part of the post-pandemic funk many city centers are now facing. Compared with other cities, St. Louis has long had one of the least populated downtown areas, and the pandemic means even fewer people milling around at night and spending money in shops and restaurants.

So a significant part of the downtown economy has focused on tourism and business conventions, leveraging the city’s iconic Gateway Arch. This area alone has received around $380 million in new investments over the past decade, according to Brian Hall, chief marketing officer for Explore St. Louis, which promotes the city as a convention, meeting, and leisure destination.

“Event activity coming into St. Louis has just been enormously important in the recovery of tourism in the downtown core,” he says.

Still, Mr. Hall believes that cities, including St. Louis, need to revitalize their downtown areas by encouraging more residential living, buttressed by a vibrant entertainment culture. They should become a magnet for innovators and entrepreneurs, he says, who want to be in the urban core for the “collision of creativity and ideas.”

Like other cities, St. Louis has tried to find ways to repurpose its past, in its case as a manufacturing hub on the banks of the Mississippi River. Old warehouses and factories have been converted into office spaces, artist studios, and entertainment venues.

“Downtowns are always having to change, as it turns out,” says Robert Lewis, professor of urban planning and development at St. Louis University. “And if we build structures that cater only to a fairly narrow part of the economy – well, they become obsolete.”

Yet St. Louis is competing with cities such as Atlanta; Nashville, Tennessee; and Austin, Texas, which are all trying to do the same thing: attract new business investment and build downtown cultural and entertainment venues, as well as parks and open spaces, that will lure visitors and residents.

Visitors are already returning to the Missouri Botanical Garden, considered one of the nation’s top gardens, says Catherine Martin, the garden’s public information officer. She puts visitor numbers at close to pre-pandemic levels. But while the garden’s finances were cushioned by tax and donor revenues, private businesses located downtown have been hit hard by the pandemic.

“There will certainly be a good number of organizations, corporations, and other businesses that continue to conduct business in urban cores, including St. Louis,” says Mr. Hall. “But everything that was in place prior to the pandemic can’t simply resume as it was. Some businesses are going to need to look at their positioning, their reason for being, and then determine if there is still an opportunity for them to return.”

Shannon Brantley, manager at Band Box Cleaners, says business has recently picked up as conventions start to return to St. Louis. But it’s still not the same.

“When we came back to work [in 2020], our business dropped 90%, because you figure all the restaurants were closed, all the courts were closed, all the businesses,” says Ms. Brantley. “So no suits, no banquets, no concerts, no nothing.”

While the family that owns the business closed one of its dry cleaning stores during the pandemic, she hopes to keep this one open. “We’re going to be here until there’s just no more money for us to, you know, keep the lights on or pay the employees.”

BOSTON – George Maherakis has been serving Ipswich clams and homemade chowder in Boston’s historic Quincy Market for more than 23 years.

His seafood stall, Fisherman’s Net, is steeped in both family and Boston history. His father opened the business here in 1981, under the Greek Revival dome that has been a part of the marketplace since 1826.

Fisherman’s Net has survived the pandemic, even as numerous commercial stalls around him have remained empty. At the low point in 2020, visitor traffic at Quincy Market was down by 95%.

Business has picked up lately with the return of tourists to Boston, but a significant part of Mr. Maherakis’ longtime customer base is still missing.

“I’m definitely worried about it because we need the office workers to come here and work,” says Mr. Maherakis, who is president of the Faneuil Hall Marketplace Merchants’ Association. “We need them to fill up the city again.”

Yet even though Boston has seen the cascading effects of the work-from-home revolution on downtown businesses, experts say the city is better poised than others to recover from the pandemic’s economic hit.

Boston currently has one of the lowest office vacancy rates in the nation. One reason is a biotechnology boom that supports both demand for existing office space and, increasingly, the conversion of office buildings into laboratories. Since 2016, nearly 3.5 million square feet of office space has been converted to laboratories in the Boston area, according to the Boston Business Journal. Another 8.5 million more square feet of office-to-lab conversions are on the way.

Even so, new hybrid models of work mean fewer daily commutes into Boston’s business districts. Already the changes can be seen in the foot-traffic patterns monitored by the Downtown Boston Business Improvement District. Using 14 motion sensors, the group has calculated that in one week just before the pandemic hit in March 2020, there were more than 850,000 people walking around the city’s downtown districts. During the same week in 2021, the number dropped to 195,000. More recently, the number of pedestrians rebounded to 465,000 – still well short of pre-pandemic levels.

While much of this is due to the lingering at-home workforce, some of it has to do with changes by businesses themselves. Many firms with flexible working models are remodeling offices to spread out desks and add more spaces where workers can relax, a departure from the cramped cubicles of yesteryear. The net result may be offices with fewer workers on any given day.

“I think that has pros and cons, and our ability – our survival – will be how we adapt to that,” says Anita Lauricella, interim director of the Downtown Boston Business Improvement District. For now, her agency is trying to coax more local visitors to the area after-hours and on weekends by promoting public events such as ice sculpture displays.

Yet the people who live and work downtown are still vital. Just ask Al Costello, owner of Al’s State Street Cafe, a popular sandwich shop not far from Quincy Market. Eight out of 10 of his customers come from the high-rise office towers that surround the shop on a narrow street in Boston’s financial district.

“I mean, these streets, you could barely fit on the sidewalk,” says Mr. Costello, recalling the pre-pandemic lunch crush. “It looked like Wall Street at 12 in the afternoon.”

Revenues at this cafe, one of four he owns in the Boston area, are back to 75% of pre-pandemic levels, he says, but not because all the bankers and traders have returned. The real reason is that many of his competitors closed down, so he gets what trade remains.

The city of Boston has tried to mitigate the pandemic’s impact on local businesses. But there’s also new thinking about urban planning around downtown business districts. The administration of Mayor Michelle Wu, who took office last November, has signaled a renewed emphasis on places such as East Boston, a densely populated immigrant neighborhood across the mouth of the Charles River from downtown Boston.

“I absolutely believe that this shift is the right shift for cities,” says Tanya Hahnel, a project manager at the East Boston Community Development Corp. “I think it’s about time that they started putting money into the neighborhoods where their workers live, not just in neighborhoods where their workers work.”

Sanctions? What sanctions? Russians aren’t feeling the sting.

Russia is confronting unprecedented sanctions because of its invasion of Ukraine. But the average Russian is not feeling the effect for the most part – the result of a stronger economy as well as long-standing experience with overcoming barriers.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Two months into the “special military operation” against Ukraine, accompanied by the most comprehensive barrage of sanctions ever leveled against any country, Russian life, at least around Moscow, looks shockingly normal.

At the Europark mall, a giant hypermarket has bursting shelves and full stocks of almost everything. Only a few specific products, such as Kellogg’s brand muesli, are gone.

If you happened to be in the city and wanted to sit in an upscale coffee shop, sip a latte, and use the Wi-Fi, you’d be spoiled for choice. Restaurants, beauty salons, grocery stores, car repair services, indeed, the full range of consumer services are still operating almost normally.

And outright piracy, a fixture of ’90s life in Russia, seems set to make a comeback. For example, several Moscow cinemas are currently screening “The Batman” and other first-run Hollywood films, even though their licenses to do so have been revoked.

“It will be more difficult and expensive, but nobody will have to go without their gadgets and other comforts,” says economist Andrei Movchan.

Sanctions? What sanctions? Russians aren’t feeling the sting.

Russian President Vladimir Putin says that Western sanctions aiming to cause panic and shortages among Russians have failed abysmally. The scene at the suburban Europark shopping mall in Moscow seems to bear that out.

A few Western-owned stores, like The Body Shop and L’Occitane, have notices pasted on their doors that cite temporary closure, with no reason given. But many local franchises, selling luggage, curtains, appliances, perfumes, shoes, fashion clothing, and electronics, all seem to be working as usual.

Editor’s note: This article was edited in order to conform with Russian legislation criminalizing references to Russia’s current action in Ukraine as anything other than a “special military operation.”

The giant French-owned Auchan hypermarket downstairs has bursting shelves and full stocks of almost everything from toilet paper, to fresh meats and vegetables, citrus fruits and bananas, to a wide range of domestic cheeses and dairy products. Only if you were looking for a few specific products, such as Kellogg’s brand muesli or Finnish cream cheese, might you notice they are gone.

Two months into the “special military operation” against Ukraine, accompanied by the most comprehensive barrage of sanctions ever leveled against any country, Russian life, at least around Moscow, looks shockingly normal. Opinion surveys show that huge majorities of Russians don’t expect the sanctions to have any impact on their lives, and almost 10% say they didn’t even know about the situation.

“For the most part we are still living in our previous reality,” says Ivan Timofeev, a sanctions expert with the Russian International Affairs Council, which is affiliated with the Foreign Ministry. “But at some point we will begin transitioning to a new reality, and then it will be very hard to ignore the deep changes we shall have to make.”

“Things actually seem better”

If you happened to be at loose ends in Moscow this week and wanted to sit in an upscale coffee shop, sip a latte, and use the Wi-Fi, you’d be spoiled for choice. Restaurants, beauty salons, grocery stores, car repair services, indeed, the full range of consumer services are still operating almost normally. Thanks to the rebound of the ruble – which was trading at around 130 to the U.S. dollar barely a month ago but has climbed above its pre-February value, to around 80 – the price hikes, though very real, are not yet too worrisome.

Back at the Europark mall, clearly named in a more optimistic time, you need to squint hard to spot the emerging supply gaps.

At the food court upstairs, McDonald’s and KFC have been shuttered for weeks. But there is still a pizza stand, an Asian wok place, and a Vietnamese restaurant. Baskin-Robbins continues to dispense about a dozen flavors of ice cream. Teremok, a Russian fast-food outlet that serves up borscht, blini (pancakes), pelmeni (meat dumplings), and Russian salads (vegetables in mayonnaise), seems to be enjoying newfound popularity. Irina, eating some combination of that with her preteen son, Vova, insists the choices are probably healthier now.

“Things have been strange for quite a while,” she says. “Last year, during the pandemic, none of these shops were even open. Things actually seem better.”

If you were craving American-style fast food, nearby outlets of Burger King and Subway are doing a roaring business with their signature offerings. That can be explained by the franchise system, which really took off in Russia over the past decade or so. The head offices of those companies may have left Russia, but the individual outlets continue working.

The manager of a local Burger King, who didn’t want his name mentioned, says that he can source almost all the items on his old menu locally, and carry on indefinitely. He admits a few adjustments will have to be made, including new packaging and some substitute condiments and seasonings. It won’t look, or perhaps taste, exactly the same, but most people won’t even notice, he insists.

“I am pretty sure food isn’t going to be a problem no matter how serious the sanctions get,” says Mr. Timofeev. That’s a politically potent point, since major turning points in Russian history have often been driven by the curse of famine. “Russian agriculture is pretty self-sufficient today and whatever outside inputs, like seeds and equipment, can probably be replaced.”

And those foodstuffs that Russia does need to import can be acquired from countries that are not part of the West’s sanctions regime. Some of the biggest sources of citrus fruits are Turkey and former Soviet countries like Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. And Russia gets its sugar largely from Brazil, which has not signed on to sanctions.

Obviously Russia has no domestic energy shortages. Prices for home heating and electricity are stable and relatively low. No potential shocks there. The price of gasoline in Moscow was 53 rubles per liter [about $2.85 per gallon] last week, and hasn’t changed much in recent years.

Back to the ’90s?

When asked, many Russians say that whatever happens, they will find ways to cope. That perspective is probably informed by their past lives in the former Soviet Union, an economy that survived seven decades producing almost everything it consumed, from cabbages to paper clips to rocket ships. During the near-total economic implosion in the 1990s, Russians grew their own food, routinely used pirated versions of software and movies, and fell back on barter, family, and community networks to survive.

No one seems to believe the present crisis is going to get that bad. But experts warn that it’s early, and the real crunch in supply chains and crippled industrial capacities probably won’t arrive until at least next year.

There are serious worries about parts and servicing for the Japanese and European cars that millions of Russians drive. Most Western automotive giants are among the hundreds of foreign companies that have pulled out of Russia since February, shredding their warranties in the process. The cost of many spare parts has leapt by as much as 50% in recent weeks, according to an article in Gazeta.ru.

But new logistics chains are already being sourced to companies in China, the article says, a big manufacturer of car parts for the whole world.

Even brand-name Western products will keep arriving through “gray distribution” networks, much like those pioneered by other sanctioned countries like Iran, says Andrei Movchan, an independent economist. One of many examples of how that works is an ad for a Turkish company, which promises to purchase any goods the customer wants, and pass them on for payment in rubles to the Russian end user.

“It will be more difficult and expensive, but nobody will have to go without their gadgets and other comforts,” says Mr. Movchan. “In the longer term, Russian industry is capable of producing a lot of things, or it can be ramped up to do so. It’s just that it will be the technology of 20 years ago, worse quality, higher costs. That’s not good, but we can survive it.”

And then there’s outright piracy, a fixture of ’90s life in Russia, now set to make a comeback. For example, several Moscow cinemas are currently screening “The Batman” and other first-run Hollywood films, even though their licenses to do so have been revoked. That’s controversial, even in Russia, and there is a heated discussion about it in the entertainment press.

“I’m afraid we are headed back to the future,” says Alexey Raevsky, director of Zecurion, a Moscow cybersecurity firm. He says the departure of Western competitors has been a big boost to his business.

“When we are talking about software development, there is no issue of spare parts or physical facilities. It’s just a digital code,” he says. “As they say, nature abhors a vacuum. I talk to people in places like Iran and Syria, where they are strictly forbidden to buy Microsoft or Cisco software, but they say they always have the latest installed on their computers. I’ve never asked them how they do that, but I am sure we’ll find out.”

Monitor Breakfast

‘A battle of nerves’: Georgia’s president on the Russian threat

Salome Zourabichvili, the president of Georgia, recently joined the Monitor to discuss what she sees unfolding in Ukraine, and the wider implications for neighboring countries like hers.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Is the country of Georgia next in line for Russian aggression?

After all, like Ukraine, Georgia is a former Soviet republic that sits on Russia’s border and is not a member of NATO or the European Union. And also like Ukraine, before Russia’s February invasion, Georgia has long had portions of its territory under de facto Russian control.

Nevertheless, the question irks Salome Zourabichvili, president of Georgia.

“By talking all the time about the fact that ‘you’re next, you’re next,’ that might [plant] some ideas,” says President Zourabichvili, speaking Friday with several reporters at a coffee organized by The Christian Science Monitor. “Nobody’s next right now, because Russia is clearly showing that it needs all its forces on the main theater,” she adds, alluding to news reports that Russia’s offensive in eastern Ukraine is faltering.

Still, Ms. Zourabichvili, who came to Washington for the memorial service of former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, wants to make sure policymakers know that Russia could target other countries.

“Nobody can see, what is the logic of the aggression started by the Russian leadership,” she says. “And when you don’t see the logic, you don’t know either what might be the day-after scenarios.”

‘A battle of nerves’: Georgia’s president on the Russian threat

Is the country of Georgia next in line for Russian aggression?

After all, like Ukraine, Georgia is a former Soviet republic that sits on Russia’s border and is not a member of NATO or the European Union. And also like Ukraine, before Russia’s February invasion, Georgia has long had portions of its territory under de facto Russian control.

Nevertheless, the question irks Salome Zourabichvili, president of Georgia.

“By talking all the time about the fact that ‘you’re next, you’re next,’ that might [plant] some ideas, even if those ideas do not exist,” says President Zourabichvili, speaking Friday with several reporters at a coffee organized by The Christian Science Monitor. “Nobody’s next right now, because Russia is clearly showing that it needs all its forces on the main theater,” she adds, alluding to news reports that Russia’s offensive in eastern Ukraine is faltering.

Still, Ms. Zourabichvili, who came to Washington for the memorial service of former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, wants to make sure policymakers know that Russia could target other countries.

“Nobody can see, what is the logic of the aggression started by the Russian leadership,” she says. “And when you don’t see the logic, you don’t know either what might be the day-after scenarios.”

For the people of Georgia, a proud nation of 3.7 million nestled in the Caucasus Mountains to Russia’s south, memories of Russia’s invasion in 2008 are fresh. So, too, is the West’s muted response, now seen effectively as a green light for Russia to keep grabbing territory in its former empire.

The Georgian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, first occupied in 2008 and representing one-fifth of Georgia’s territory, are still under Russian control. In Ukraine, the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea and backing of separatists in the eastern Donbas added another expansionist toehold by Moscow.

Today the West remains in crisis mode over Russia’s most audacious post-Soviet move yet. On Friday, President Joe Biden asked Congress for a massive $33 billion package of military and humanitarian aid for Ukraine. The Georgian president applauded the proposal.

Ms. Zourabichvili is a compelling representative for her country, elected in 2018 as Georgia’s first female president. She does not run the government; that is the purview of the prime minister. But she has a bully pulpit, and she uses it.

One striking feature is her French accent. She was born and raised in France to a Georgian émigré family, and began her career as a French diplomat. In her 30s, she visited her parents’ homeland for the first time, and in 2004, was named foreign minister of Georgia. She has been involved in Georgian politics ever since, serving for a time in Parliament and as leader of The Way of Georgia party. She is now a political independent.

In our hourlong conversation, Ms. Zourabichvili spoke of the “fragility” of both her own country and another small former Soviet republic, Moldova (population 2.6 million), which sits on Ukraine’s southwest border. Last week, explosions rocked a long-Russian-occupied part of Moldova known as Transnistria. Ukraine described the attacks as Russian “false flag” operations that could be a pretext for mobilizing Russian troops there to attack southwestern Ukraine.

“It is what I’m calling a battle of nerves,” the Georgian president says.

Following are more excerpts from our discussion, lightly edited for clarity:

On how Moldova and Georgia, two small former Soviet republics, are handling their precarious positions:

Moldova and Georgia are the two countries that are not directly protected by NATO Article 5 [which guarantees mutual defense of members] or by being in the European Union. Those are the two countries that are obviously more fragile, I would say, and they are small countries with less resources.

We probably have more defense resources than Moldova, because we have been for many years intensely cooperating with NATO, reaching NATO’s standards [to qualify for membership], participating in Afghan missions.

Although that doesn’t mean we could do something of the kind that the Ukrainians have managed to do, because it’s a different country with different resources, whether human resources or military resources. The territory is completely different. And of course Georgia would not be able to have this type of long-term resistance, and it’s probably something that the Russians know very well.

Moldova is even more fragile. It has received very many [Ukrainian] refugees. We have something like 30,000, and they have more than 100,000, I think.

On what Georgia can do to protect itself:

Most important is not to be thinking whether we are the next in line [for Russian aggression], but to do everything that we can to be next in line for European integration.

Today there is almost unanimity, including countries very reluctant to a new enlargement [of European institutions that] are now looking at that a bit differently.

On whether Russia might follow through on threats to use nuclear weapons:

Looking at the past of [Russian President] Vladimir Putin, I think it’s more playing on the nerves than a real strategy to move up to, because that’s a suicidal strategy.

But we cannot plan on the fact that he would be very rational in his behavior. If he considers that everything is lost, then I don’t know how a person like that can react and what he can do. I don’t think that’s probable, but I don’t think that it’s something that we can completely exclude.

On why the Georgian government’s response to the Ukraine war has been more muted than that of Ms. Zourabichvili and the Georgian people:

Maybe I’m freer in my talk because I’m not really in charge of governing in a strict sense. And maybe it is better explained by the fact that yes, this country with occupied territories has to be careful in certain ways.

The people that are in the ruling party and that are governing today – the prime minister and the government, that are much younger than I am – it’s a very big responsibility to be leading a small country in these circumstances. And they might be balancing more on the side of caution than I am.

Points of Progress

How Sardinians and Colombians shook things up

In our progress roundup, communities around the globe pursued goals to improve the lives of their own residents. But the positive impact of their self-improvement plans often reaches beyond.

How Sardinians and Colombians shook things up

Along with communitywide improvements around the world, individuals in the U.S. are growing their own food at home, creating positive environmental change household by household.

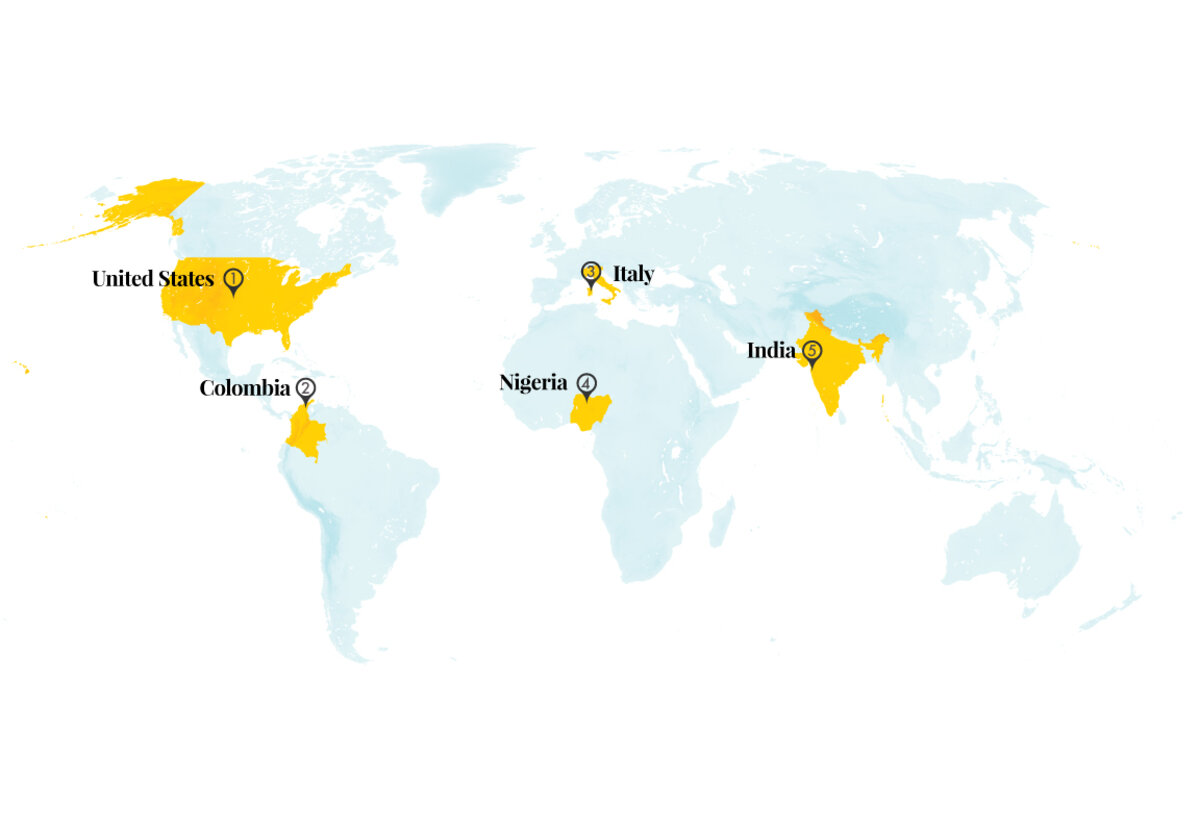

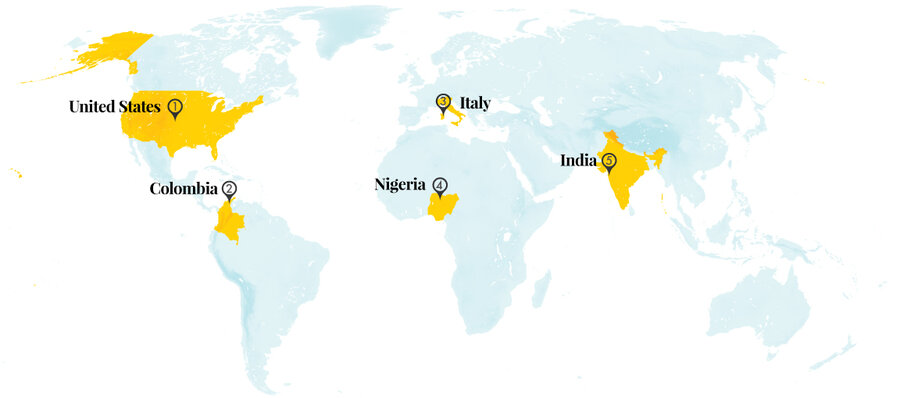

1. United States

“Climate victory gardens” are feeding Americans while contributing to a healthier environment. During World War I and II, some 20 million families across the United States planted victory gardens, supplying 40% of the country’s produce at their height. During the pandemic, backyard gardening has again grown in popularity. Green America, a nonprofit that helps people grow their own food as a way to fight climate change, has seen a jump in gardens registered with the organization from 8,670 in 2021 to 14,655 in just the first two months of this year.

What makes a garden a climate victory garden, according to the organization, is its regenerative impact, avoiding pesticides and harmful chemicals and feeding both the gardener and pollinators. That type of farm, no matter how small, can sequester more than 25 tons of carbon per acre, according to methodology adapted from the nonprofit Project Drawdown and the Environmental Protection Agency. Although many gardeners have not formally registered, Green America estimates the gardens it’s aware of have offset the emissions of the equivalent of 39 million miles driven.

Treehugger

2. Colombia

A public library in Colombia is keeping Indigenous stories and traditions alive. The mountainside town of Atánquez in the Kankuamo Indigenous reserve had never had a library, which meant there was nowhere to put a box of books delivered by the National Network of Public Libraries in 2013. So residents spruced up an abandoned building with tables, chairs, and shelves, creating a makeshift library. But they didn’t stop at books.

Today, children in the community regularly take part in library programming, from outings in which they try their hand at drawing ancient petroglyphs to gatherings with elders who share traditional music, recipes, and history. During the pandemic, the library gave kids recorders to document the stories of their family members and distributed seeds and groceries to those in need.

For decades, many Indigenous people in the area had distanced themselves from their culture to assimilate to mainstream Colombian society. This project is helping change that. “Little by little our people are falling in love and valuing what they are as indigenous peoples,” said Ener Crispin Cáceres, a Kankuamo elder. In 2017, the library won Colombia’s national library award and has earned international recognition.

The Guardian

3. Italy

An Italian town with a violent past made a new name for itself by promoting cultural tourism. Mamoiada sits in the heart of the island of Sardinia in a region the Romans once called Barbària. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Mamoiada became infamous for a series of killings linked to a family feud. But instead of giving up on the troubled town, where economic opportunities were scarce, residents and local administrators harnessed the region’s cultural strengths.

For two years, a local nonprofit worked without pay to revamp the inventory in the town’s small museum, expanding from traditional local masks known as viseras to artifacts from around the region, and creating a cultural center. Then, the group partnered with artisans, wine producers, and tour organizers to show visitors how local products are made. In 2011 and 2014, two museums opened to showcase the town’s history and archaeology. Slowly but surely, Mamoiada placed itself on the tourist map, making it possible for new restaurants and inns to open and benefiting neighboring towns as well.

News48

4. Nigeria

A mining region in northwest Nigeria effectively handled a lead pollution problem. When gold boomed during the financial crisis, small-scale and unregulated mining became an important source of income for rural residents of the mineral-rich but impoverished state of Zamfara. But the gold was processed with few safety precautions, and lead pollution created significant health risks for community members. The crisis came to a head in 2010, when 400 children died from lead contamination in a period of six months, with several hundred deaths in the following years.

In response, government officials teamed up with three international organizations to improve mining conditions. Over 5,000 miners and local workers have been trained to prevent lead exposure, and new processing sites equipped with showers a few miles from residential areas help workers avoid bringing mineral deposits into the home at the end of the day. The efforts have been complicated by conflict in the region, and poverty still limits opportunities for locals beyond mining, but the changes have nonetheless strengthened safety standards for miners and their families. There have been no child deaths linked to lead poisoning since October 2021.

The Guardian

5. India

Mumbai became the first city in South Asia to outline a road map to net-zero emissions. The financial megalopolis, home to 19 million people, is planning to eliminate or offset all carbon emissions by 2050, two decades ahead of India’s national goal. Without intervention, climate change could cost the city $920 million by midcentury, with rising tides that would flood informal settlements and fishing villages along the coast.

Officials, residents, scientists, and companies all contributed to the Mumbai Climate Action Plan, which aims to cut emissions by 30% by 2030 and 44% by 2040, from a base level of 23.42 million metric tons of carbon dioxide in 2019. In the short term, Mumbai will electrify its public transportation and help low-income households install energy-efficient equipment. A complete switch to renewable energy is a more daunting endeavor, with detailed proposals still to come. But as India’s wealthiest city, Mumbai may be better equipped than other parts of the country to make the transition, thanks to access to investors. For Aaditya Thackeray, minister of the environment of the state of Maharashtra where Mumbai is located, the reasoning behind the new plan is simple: “We don’t have the luxury of time.”

Bloomberg

Books

Joy in the garden: Books to inspire beauty and self-reliance

Watching a seedling break through the soil, or harvesting our own produce, can bring joy and pride. Gardening, in whatever space we have, nurtures our families and ourselves.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Gardening was one of the first hobbies people adopted during the pandemic. Now, many of those gardeners are ready to up their game. At the same time, people new to gardening are looking for guidance and inspiration.

Five recent books offer practical advice and plenty of encouragement for creating the backyard, patio, or windowsill of your dreams. No matter what kind of space you have, there’s a way to bring the bounty of plants into your life.

Whether it’s growing microgreens on a table or sowing wildflower seeds in a field, gardening brings people back to the rhythms of the seasons and the feel of dirt in their hands.

Joy in the garden: Books to inspire beauty and self-reliance

More people are discovering the joys of growing things in small and large ways – from pots on the windowsill to overturning a section of lawn to make room for native plants and pollinators. Easing the boundaries between indoors and outdoors by tending to plants was one of the first hobbies people cultivated over long months at home during the pandemic. If, after a couple of successful seasons, you are ready to up your game, here is a selection of new titles to inspire, encourage, and even entertain as you get ready to dig in the dirt and watch your garden grow.

Small spaces are no problem

Being a successful gardener doesn’t require a large, sunny backyard, as apartment dweller Amy Pennington proves in Tiny Space Gardening: Growing Vegetables, Fruits, and Herbs in Small Outdoor Spaces. Pennington, who gardens with pots in a 75-square-foot space in Seattle, urges urbanites to foster an intimate connection to growing things: “To be a successful container gardener, you need to think like a plant,” she writes.

For starters, think about nourishing their roots, and choose containers accordingly. Porous clay pots have a lovely rustic look, but plastic pots are lighter to move around and hold moisture longer. Or use a bag of potting soil as your “container.” Since you are a tiny space gardener, your gardening tools can be diminutive, too, such as forks (instead of rakes), spoons (instead of trowels), and measuring cups (instead of shovels) to mix and move soil.

Pennington is an advocate for using your space for “experiments and experience,” and encourages growers to pick their battles: If you can’t get fussy tomatoes to grow, check out the heirloom offerings at the farmers market. Lettuces, herbs, and edible flowers bring quick and easy rewards. Pennington also includes a few recipes and windowsill projects, such as a microgreens garden.

Back to the land

If you have ever fantasized about trading in city life for foraging for your own food, Tamar Haspel, who writes a food-policy column for The Washington Post, has done it for you in her hilarious memoir To Boldly Grow: Finding Joy, Adventure, and Dinner in Your Own Backyard.

Haspel and her husband, Kevin, pulled up their New York City roots during the financial crisis of 2008 and bought a “very shack-like” house on Cape Cod in Massachusetts. The memoir centers on Haspel’s challenge to expand their urban rooftop gardening skills: eating at least one thing every day for a year that they obtain first hand. In other words, food they either grew, fished, hunted, or gathered.

This launches an odyssey of figuring out what exactly will grow in their sandy-soiled backyard (shiitake mushrooms) and expands to digging up oysters, drilling holes in the ice to fish, corralling flying turkeys, evaporating sea salt into a gourmet delicacy, and eventually “harvesting” deer from a friend’s overpopulated land, among other adventures.

Haspel, who writes the award-winning “Unearthed” column, turns her skills as a science journalist toward solving the perplexing problems that come with living off the land and enticing readers with its many rewards.

A guide to every stage

Ready to roll up your sleeves and start a garden of your own? Gardening for Everyone: Growing Vegetables, Herbs, and More at Home by Julia Watkins is a great beginner’s resource.

Designed as a guide for each stage of the growing season, this book offers plenty of tips and DIY projects from analyzing the amount of sun your plot of land or patio receives to establishing the best growing method for you – raised beds or small containers. There are tips for understanding and testing your soil, and improving it by making compost.

This book grows with you, too. Each year of gardening brings new expertise and opportunities to expand the functionality of your garden, whether it is using native plants to support local pollinators and birds or raising your own vegetables and flowers from seeds.

A chapter titled “Playing” reminds readers there is fun to be had digging in the dirt at any age, and includes projects such as making steppingstones, a gourd birdhouse, and edible flower lollipops, along with a few recipes. Beautiful photographs throughout offer places to rest amid all the good information and instruction, and wide margins invite you to make notes about your own garden.

Keep ’em coming

If you are an experienced gardener but are wanting to step it up a level, Plant Grow Harvest Repeat: Grow a Bounty of Vegetables, Fruits, and Flowers by Mastering the Art of Succession Planting by Meg McAndrews Cowden will help you create a garden with constant blooms that delight and produce that nourishes. The author took her backyard hobby into a full-time job and did it all in the short growing season of Minnesota.

Consider this book a useful guide for the thinking gardener who prefers organic practices. Succession gardening, where one growing cycle yields to the next, promises maximum output for your garden while utilizing space to its fullest. Beginning with fast-growing radishes and cool weather greens, Cowden instructs gardeners with charts and graphs through the crowded mid-season, finishing with beans and sweet corn in August and the return of late harvest greens.

If that doesn’t keep you busy enough, succession planting for perennial and annual flowers ensures pops of color and regular food for pollinators. Cowden explains the art of interplanting by effectively balancing plants as they compete for light, water, and nutrients, and lists some of her favorite flower and vegetable combinations.

Works of floral art

Gardening is hard work and if you’d rather just enjoy the beauty of cut flowers without getting grass stains on your knees The Flower Hunter: Seasonal Flowers Inspired by Nature and Gathered From the Garden by Lucy Hunter is a book charming enough to leave out on your coffee table or offer as a gift.

Hunter, who had a fine-arts background before she shifted to landscape design, lives in North Wales. She conducts global workshops on floral design and has a robust following on Instagram. Her romantic, shabby-chic still lifes – carefully crafted with old treasures and cascades of wildly twisting flowers – offer a kind of escapism if you take some time to pore over her photos and linger over the accompanying essays. Hunter is an artist and she invites readers to “create work that makes you happy.”

This book doesn’t offer too much in the way of practical instruction, aside from a few pages here and there about the best vessels and structure for centerpieces and so forth, but it does encourage readers to really see the beauty in the garden as it changes from season to season.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A war-altering rescue of Ukraine’s innocent

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

On May 1, Russia and Ukraine cooperated just enough to allow dozens of Ukrainian civilians to leave their bunkers beneath a steel plant in the besieged city of Mariupol and travel to a safe zone. Just 10 days earlier, Russian President Vladimir Putin said his troops would surround the factory so that “not even a fly can come out of it.”

Did something change Mr. Putin’s thinking about saving those innocent Ukrainians?

Since the Russian invasion began Feb. 24, many Ukrainian civilians have been evacuated through Russian military lines but nothing quite as significant as the rescue of those forced to shelter beneath the Azov steel plant. “The organization of such humanitarian corridors is one of the elements of the ongoing negotiation process,” said Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

The tactic is often used in war: build trust between warring parties by saving noncombatants, appealing to both sides in protecting the dignity of innocent lives. That trust may then open doors for peace.

Many more humanitarian corridors are needed in Ukraine. If the convoy now rescuing the hundreds of people in Mariupol succeeds, it may lead to additional peacemaking actions.

A war-altering rescue of Ukraine’s innocent

Mark the day. On May 1, Russia and Ukraine cooperated just enough to allow dozens of Ukrainian civilians to leave their bunkers beneath a steel plant in the besieged city of Mariupol and travel freely for 140 miles to a safe zone. Just 10 days earlier, Russian President Vladimir Putin said his troops would surround the factory so that “not even a fly can come out of it.”

Did something change Mr. Putin’s thinking about saving those innocent Ukrainians who had endured weeks trapped in a city critical to Russia’s war aims?

Since the Russian invasion began Feb. 24, many Ukrainian civilians have been evacuated through Russian military lines but nothing quite as significant as the rescue of those forced to shelter beneath the Azov steel plant. In an unusual move, Russian media praised Mr. Putin for his “initiative” in letting the civilians go. Yet much of the credit goes to Ukrainian officials, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres, and the International Committee of the Red Cross. Their diplomacy in recent weeks has focused on rescuing the most vulnerable civilians in the crosshairs of the battle for Mariupol.

The city’s trapped citizens, said Mr. Guterres last month, “need an escape route from the apocalypse.” Yet the rescue was more than that. “The organization of such humanitarian corridors is one of the elements of the ongoing negotiation process,” said Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in announcing that a convoy of civilians had left the seaport city on Sunday.

The tactic is often used in war: build trust between warring parties by saving noncombatants, appealing to both sides in protecting the dignity of innocent lives. That trust may then open doors for peace.

Mr. Putin’s motives for the Mariupol evacuation are not clear. Perhaps many of the officials around him do not want to be tarred as war criminals. In many wars, a turning point often occurs when saving lives is more important than taking them.

Many more humanitarian corridors are needed in Ukraine. If the convoy now rescuing the hundreds of people in Mariupol succeeds, it may lead to additional peace-making actions.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Truth speaks all languages

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Susan Stark

Whatever our background, wherever we are, and whatever the circumstances, the healing message of Christ speaks to all of us – in a way we can each understand.

Truth speaks all languages

What would you have thought if you had come all the way from Libya to Jerusalem for a Jewish harvest celebration and heard a new message in your own language from people who didn’t know that language? And you weren’t alone. The person from what’s now Turkey heard the message in his own language. And visitors from Rome heard it in theirs.

That’s what happened a scant 50 days after Christ Jesus’ resurrection and less than two weeks after his ascension. What took place was extraordinary. On what Christians know as the Day of Pentecost, a mighty sound of wind was followed by “tongues like as of fire” resting on the Christian apostles, “and they were all filled with the Holy Ghost” when they spoke to the surrounding crowd (see Acts, chap. 2). They spoke in different languages, and the listeners received a message of hope and salvation – each in his own language.

What those listeners heard that day, many for the first time, was that Christ Jesus overcame death and then ascended. In the days and years that followed, many would go on to discover that Jesus’ message of Christ, or Truth, really was available for everyone, everywhere, to understand and practice, reforming and healing lives.

Today, no matter where we find ourselves – mentally or geographically – Truth speaks to us. We can count on it to reveal our true, spiritual nature and heal us. We are free to accept our own true self as created by God, divine Spirit, and find our potential for good as healers for ourselves and others.

Mary Baker Eddy, who discovered and founded Christian Science, recognized that Christ speaks to each individual without regard to race or creed or country. Her book Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures identifies Christ in this way: “Christ is the true idea voicing good, the divine message from God to men speaking to the human consciousness” (p. 332).

You can recognize Christ, or the spirit of Truth, in every inspired good, honest, intelligent thought you have. The divine voice can come as the conviction that goodness has more power than evil if we are in a mentally dark place or difficult circumstance. It can be the confirmation that you are well and whole because God has made you so.

Plenty of thoughts that aren’t from God come to us. A downward-pulling emotion or even a sick feeling isn’t a message from Truth. Christian Science helpfully categorizes such communications as mortal error, the opposite of Truth, and not from God. Fearful thoughts can be silenced by every spiritual intuition that tells us of God’s power, presence, and guidance.

Routine human thinking – limiting habits of thought – would argue that divine communication is confined to a certain time in world history, or in one’s own life. Or say to us that it is possible for others to experience their unity with God, good, as His expression, but not for us. But each prayer that affirms that we are all the children of one God, the loving, all-powerful Spirit, destroys some resistance to Truth.

People embraced the Christ message at Pentecost, and this receptivity to Truth continues into the present. We are an important part of it as we listen to the spiritual intuitions from Truth that come to us minute by minute and let them transform how we think and act.

A testimony of healing originally in the online Russian edition of The Herald of Christian Science shows in a quiet way the reach of Truth to the receptive heart. A woman from the country of Georgia read a pamphlet on Christian Science in Russian and started to see healing from what she was learning from it. Her part-time teaching job became full-time, and she was named best teacher in her school. When she received a pay raise, the extra money she earned allowed her to help family and friends. She was healed of back pain. The truths she was learning from Science and Health were her daily support when she moved to a new country, and she went on to be healed of recurring menstrual cramps. She said, “Christian Science showed me how to listen to God, and it is still showing me the way to live. God is always with us!”

As we look out on our world, we too can bear witness to the Truth as it speaks to each and every one, in a way that is meant just for them.

Adapted from an editorial published in the May 2022 issue of The Christian Science Journal.

For a regularly updated collection of insights relating to the war in Ukraine from the Christian Science Perspective column, click here.

A message of love

Holiday joy

A look ahead

Thanks for starting your week with us. Please keep an eye out Tuesday for Stephen Humphries’ story about Elon Musk’s bid to buy Twitter – and what it will take to build trust in online information and discourse.