- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Ahead of crucial Party Congress, Xi faces doubts over policies

- As youth antiwar sentiment persists, Russia pushes patriotism at school

- Poland given pass on rights violations because of Ukraine war role

- How Florida became the leader in fighting fire with fire

- Lively guests: Invite the 10 best books of May into your home

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How neighborliness is easing the baby formula shortage

Posts about the national baby formula shortage in a Facebook group for parents in my eastern Massachusetts town caught my attention recently.

After several moms asked for help finding the formula brands their babies need, a robust team effort developed. Other parents shared pictures of shelves in nearby stores with formula in stock and exchanged tips about how best to order online. Someone provided a link to the Free Formula Exchange, a newly created website set up by a Massachusetts mom in another town to match formula donors and recipients.

The posts reminded me how astonishing community help can be. When my younger daughter was born, we received a parade of meals dropped off at our house for weeks. The meal train was organized by our town’s volunteer-run family network, and many of the stir-fries and soups we devoured were given to us by neighbors we had never met. Their generous community spirit was deeply touching to my husband and me during the bleary-eyed stage of caring for our new infant and her toddler sister.

The current baby formula shortage won’t end only through parents supporting each other. Across the United States, 43% of the formula supply was out of stock as of May 8. Supply chain woes and the closure since February of a key Michigan factory after a formula product recall continue to pose challenges, although in a sign of progress the Food and Drug Administration yesterday announced an agreement with Abbott Laboratories to reopen the factory in about two weeks. The crisis has raised concerns about shaming of mothers for not breastfeeding and reignited calls for more robust parental support through policies like national paid parental leave.

Amid these thorny problems, I appreciate the simple moments of unselfishness I’ve been witnessing among parents in my hometown. Neighborliness is always a welcome gift.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Ahead of crucial Party Congress, Xi faces doubts over policies

Xi Jinping is poised to claim a rare third term in power at the 20th Communist Party Congress this fall. But experts say his assertive style and efforts to centralize control could cost him – and China.

A huge red banner lining a corridor in a Shanghai quarantine hospital declares Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s exhortation in bold white characters: “Persistence is Victory!”

Mr. Xi’s call for persistence is now China’s watchword – not only in the battle to contain the country’s biggest COVID-19 outbreak but also across many other fronts. His overarching goal: to prevent social unrest and political doubts in the run-up to the crucial 20th Congress of the ruling Communist Party this fall, when Mr. Xi is expected to win a rare third term in power.

Staying the course will be difficult, China experts say, because Mr. Xi’s bold domestic and foreign policies are controversial. Many worry about the economic toll of his strict zero-COVID-19 strategy and staunch support for Russia, and that Mr. Xi’s centralization of control is leading to a less dynamic society.

Yet analysts expect Mr. Xi will continue to double down on his policies, at least until the party congress, lest any adjustments offer ammunition to his critics. In China’s political culture, “the reorientation of policy ... raises a lot of questions,” says Yun Sun, director of the China program at the Stimson Center in Washington. “The first question is, was that policy wrong?”

Ahead of crucial Party Congress, Xi faces doubts over policies

A huge red banner lining a corridor in a warehouse-like Shanghai quarantine hospital declares Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s exhortation in bold white characters: “Persistence is Victory!”

Mr. Xi’s call for persistence is now China’s watchword – not only in the battle to contain the country’s biggest COVID-19 outbreak but also across many other fronts. His overarching goal: to prevent social unrest and political doubts in the run-up to the crucial 20th Congress of the ruling Communist Party this fall, when Mr. Xi is expected to win a rare third term in power.

“Persistence means hardship, exhaustion, and holding on with gritted teeth,” said a commentary last week in the Communist Party’s main newspaper, People’s Daily.

Staying the course will be difficult, China experts say, because Mr. Xi’s bold domestic and foreign policies are controversial. His strict zero-COVID-19 strategy, his staunch support for Russia, and a recent crackdown on tech giants have broad popular support, but their economic price has nonetheless sparked intense debate among Chinese analysts, stakeholders, and the public.

Yet analysts expect Mr. Xi will continue to double down on his policies, at least until the party congress, lest any adjustments offer ammunition to his critics. Any hint of uncertainty could complicate Mr. Xi’s plans to extend his rule as China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong, and to buttress it through the promotion of trusted allies.

In China’s political culture, “the reorientation of policy ... raises a lot of questions. The first question is, was that policy wrong?” says Yun Sun, director of the China program at the Stimson Center in Washington. “With his policy currently, he’s already creating a lot of complaints and ... dissatisfaction within the country, so for him to change the policy now is going to be politically even more risky than not changing it.”

More broadly, Mr. Xi has centralized power since he took charge a decade ago, making the party and government less flexible and pragmatic, experts say. Mr. Xi has strengthened the party by rooting out corruption and indiscipline, but he has also transformed it into “a top-down and single-leader dominant institution – not one that is responsive to the needs and input from other actors inside and outside the system,” says David Shambaugh, founding director of the China Policy Program in the Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University.

Maintaining the status quo

As the congress approaches, Chinese authorities across the country are stepping up efforts to head off any potential disruptions.

Security officials have launched a drive to eliminate social and political “risks” and ensure the “victorious hosting of the 20th Party Congress,” said Chen Yixin, secretary-general of the Central Political and Legal Affairs Commission, China’s top law enforcement body, at a meeting in April, according to the commission’s official social media account.

“Maintaining a stable domestic environment in the lead-up to the party congress is the top priority – every policy is made to ensure that goal,” says Tong Zhao, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Beijing.

The congress is an event held once every five years at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing to set major policies and select top leaders – including the roughly 370-strong Central Committee and 25-member Politburo. In backroom deliberations, senior party leaders select the Politburo’s Standing Committee, the pinnacle of party power.

While Mr. Xi’s securing of a third term is virtually guaranteed, the success of those he will seek to promote is less so.

“The ... probable outcome is that Xi is appointed ... but maybe he will not get up around him all the folks that he wants,” constraining his power in a third term, said Kevin Rudd, president of the Asia Society and the former prime minister of Australia, at a recent online talk at the Chicago Council on Global Affairs.

One indicator of Mr. Xi’s strength will be what happens to his protégé Li Qiang, Shanghai’s Communist Party leader. Although he was once tipped for the Standing Committee, Mr. Li’s unpopularity over his management of a punishing lockdown in Shanghai might prompt Mr. Xi to jettison him in order to salvage his own credibility, Dr. Sun suggests.

Lockdown woes

This month, Mr. Xi presided over a meeting of the Politburo Standing Committee that issued a stern warning over any wavering from China’s zero-COVID-19 policy, indicating concerns about dissenting views. The group pledged to “resolutely struggle against all words and deeds that distort, doubt and deny our epidemic prevention policies,” according to official press accounts.

Pro-government commentators, epidemiologists, business executives, and many ordinary people have questioned the zero-COVID-19 strategy and its mounting economic and social costs.

“The Shanghai lockdown ... indicates the limits in what individual Chinese citizens can tolerate in terms of a COVID policy,” says Jennifer Hsu, research fellow in the Public Opinion and Foreign Policy Program at the Lowy Institute in Australia. “We can definitely see people’s patience for that kind of extreme policy measure reaching almost a breaking point. When it starts to affect people’s livelihoods, people’s ability to source and acquire goods for basic survival, the state has to take note of that.”

Yet, she says, “any backtracking by Xi would be particularly fraught ... because he has invested so much of his personal capital into that policy which he has deemed for saving lives.”

China has so far succeeded in keeping COVID-19 cases and deaths extremely low by global standards. Mr. Xi and the party have argued that any loosening of the policy could risk causing an overwhelmed medical system and large-scale illness and fatalities, especially among the 50 million people in China over the age of 60 who are not yet fully vaccinated.

Seeking to prevent instability, Mr. Xi will not deviate from the zero-COVID-19 approach and instead will “do all things to maintain the status quo – he will not challenge himself,” says Alfred Wu, associate professor in the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy at the National University of Singapore. “He will take a 100% sure approach in terms of his third term.”

Russia concerns

Beijing’s staunch backing for Russia and Moscow’s position on Ukraine has also generated debate within China – yet again, the consensus among experts is that Mr. Xi will persevere with the strategy.

China’s public is generally supportive of Russia, reflecting in part the pro-Russia stance in official media and the distribution of Russian state broadcasts here. Yet privately, among policy experts and some ordinary people, debates have been intense, experts say.

“It’s one of the most divisive issues in recent years that really set different groups of people arguing fiercely against each other, including in the expert community,” says Dr. Zhao.

“Many experts are against this war. They blame Russia for the invasion, and they don’t want China to be seen as part of this block that supports Russia,” he says. Another concern is that China will be “entrapped” and its interests and international reputation potentially compromised by future actions of Russian leader Vladimir Putin, he says.

One prominent expert, Hu Wei, vice chairman of the Public Policy Research Center of the Counselor’s Office of the State Council, published an article in early March urging Beijing to change course. “To demonstrate China’s role as a responsible major power, China not only cannot stand with Putin, but also should take concrete actions to prevent Putin’s possible adventures,” he wrote, in what experts called an open bid to influence official policy.

China’s alignment with Russia, intended as a strategic counterweight to the United States, was advanced in a Feb. 4 joint declaration stating that the friendship between the two countries had “no limits.” Mr. Xi’s “personal inclination to forge this very strong and close strategic partnership with Russia has been one of the main drivers of the bilateral relationship,” Dr. Zhao says.

Beijing has reaffirmed that it will stick to this policy, despite its potential to damage long-term relations with Europe and the U.S., he says. Still, in the context of the upcoming 20th Party Congress, “the war is not good news for China,” Dr. Zhao adds. “It has all sorts of implications that could perhaps destabilize the domestic situation and could cause unprecedented economic ... shock waves.”

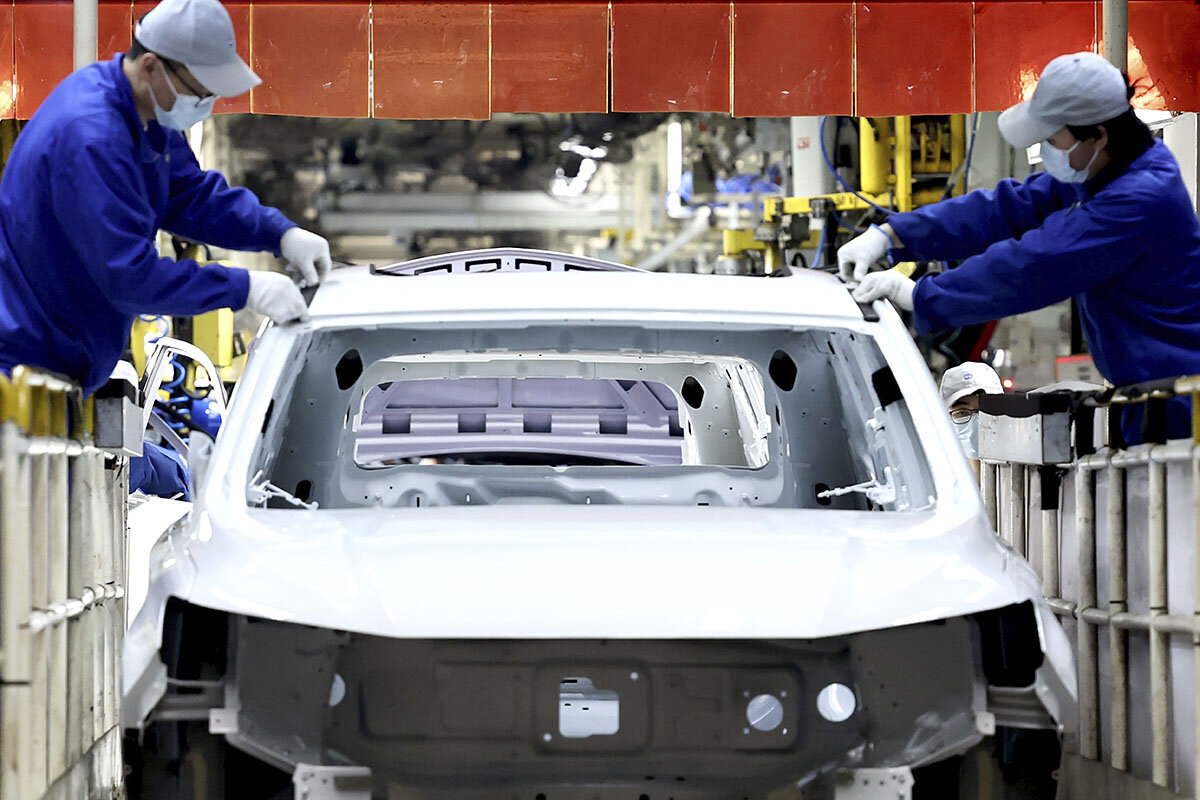

Economic toll

The promise of rising economic prosperity remains the bedrock of party legitimacy, yet China has now fallen into its worst slowdown since early 2020, according to the latest economic data released Monday by the National Bureau of Statistics. Industrial production slumped 2.9% – and retail sales 11.1% – from a year earlier. “The increasingly grim and complex international environment and greater shock of COVID-19 pandemic at home obviously exceeded expectation,” the bureau said. “New downward pressure on the economy continued to grow.”

China’s economic growth for this year – targeted at 5.5% – is now forecast by financial analysts to be about 4%. Already, growth had been slowly declining amid long-term challenges of an aging population, a shrinking workforce, heavy local debt, and an economic policy that favors less efficient state enterprises over the private sector.

Earlier this year, Mr. Xi unveiled a campaign for “common prosperity” that included swift regulatory crackdowns on big tech firms, business magnates, and industries such as private tutoring and gaming. The campaign follows Mr. Xi’s successful poverty alleviation drive and is intended to boost his already strong popularity among China’s large low-income population. But the drastic, overnight regulatory moves spooked overseas investors and Chinese entrepreneurs.

“He wants to please very much the grassroots people and show he cares about income distribution,” says Dr. Wu.

Now, COVID-19 restrictions in major cities are disrupting businesses and production nationwide, drawing complaints from foreign chambers of commerce. Costs to fiscal revenue are mounting from mass testing requirements. Unemployment in 31 major cities surged to a pandemic high of 6.7% in April, leading Premier Li Keqiang to warn this month of a “grave” job market, and labor protests have also increased, according to the China Labor Bulletin.

While Mr. Xi has heralded China’s advance to become a “fully developed, rich and powerful nation” by 2049, his growth-dampening policies are making China’s economy and society less dynamic, experts say. Politically, his dominance over decision-making is limiting China’s leeway for making course corrections.

Persistence may well lead to victory in China, but how that victory is defined and by whom is another question.

As youth antiwar sentiment persists, Russia pushes patriotism at school

Patriotism can be put to many uses. Russia hopes teaching it in school will boost support for the conflict in Ukraine among the least supportive group – young people.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

While polls suggest that most Russians back their military’s actions in Ukraine, 35% of high school and university students are negatively disposed toward the conflict, according to Russia’s only independent public opinion agency.

To address that, the Kremlin is rolling out new efforts to encourage patriotism among students. Starting in September, Russian pupils will begin their week with a flag-raising ceremony, singing the national anthem, and a fresh, Russia-oriented course on modern history.

Among the new classroom techniques being promoted by the Education Ministry will be active discussion of current events, in which teachers will help to steer pupils through what is seen as an increasingly vicious information environment that features a proliferation of negative and “fake” claims about Russia.

Margarita Simonyan sits at the nexus of Russia’s information policy. She told the Monitor via email that Russia needs to follow the American example of instilling pride in one’s country from a very young age.

“I really envy American students who start their school day with a pledge of allegiance to the American flag,” she says. “This is a good tradition, and one that is a significant part of American patriotic education. Russia lacks this. Since the collapse of the USSR no one has seriously worked on this in the way that is customary in the U.S.”

As youth antiwar sentiment persists, Russia pushes patriotism at school

The letter Z, the symbol of Russia’s “special military operation” against Ukraine, has proliferated across the urban landscape: on billboards, windshields, public buildings, and T-shirts. Increasingly, it’s even being displayed by children at school – which the country’s conservative commentators see as key to filling what they view as troubling gaps in support for the conflict.

While polls continue to suggest that most Russians back their military, the greatest dearth of enthusiasm is among high school and university students, who “have the highest level of negativism, at 35%, toward the war and authorities among all groups of the population,” according to Lev Gudkov, head of the Levada Center, Russia’s only independent public opinion agency.

Editor’s note: This article was edited in order to conform with Russian legislation criminalizing references to Russia’s current action in Ukraine as anything other than a “special military operation.”

To address that, the Kremlin is rolling out new efforts to encourage patriotism among students, including American-style flag ceremonies and anthem singing, expanded cadet training, and greater efforts to combat news narratives that don’t comply with those from Russian sources.

Conservative voices have long argued that the negativism being seen among students begins in primary schools, which, following the collapse of the USSR three decades ago, abandoned patriotic, military education as a vestige of the failed Soviet experiment. Russia’s 1993 Constitution does not spell out any official ideology, much less describe a clear national identity. The resulting vacuum of patriotic schooling left subsequent generations confused, demoralized, and susceptible to Western narratives that diminished Russia’s place in the world and fueled doubts about the state’s legitimacy, they say.

Margarita Simonyan, head of the Rossiya Segodnya media conglomerate, which includes the English-language RT network, sits at the nexus of Russia’s information policy. According to news reports, she and others have held meetings with teachers about how to combat the flood of “fake news” about Russia’s military operation infiltrating the classroom. In one meeting, according to the news agency RBK, she recalled Russia’s volatile history, warning that disunity instigated from outside led to destabilization, and “differences among the people within the country led to catastrophe” and state collapse in 1917 and 1991.

Asked to flesh out her views by the Monitor, Ms. Simonyan, who spent a year living in the United States, would say only that Russia needed to follow the American example of instilling pride in one’s country from a very young age.

“I really envy American students who start their school day with a pledge of allegiance to the American flag,” she said in an emailed response. “This is a good tradition, and one that is a significant part of American patriotic education. Russia lacks this. Since the collapse of the USSR no one has seriously worked on this in the way that is customary in the U.S.”

Patriotic education

Under a law that has been in preparation for a couple of years, that is all set to change.

Starting in September, Russian pupils will begin their week with a flag-raising ceremony, singing the national anthem, and a fresh, Russia-oriented course on modern history. Among the new classroom techniques being promoted by the Education Ministry will be active discussion of current events, in which teachers will help to steer pupils through what is seen as an increasingly vicious information environment that features a proliferation of negative and “fake” claims about Russia.

A range of other extracurricular activities will be introduced, including a major expansion of the “Yunarmiya” system of universal cadet training, in which schoolchildren are taught military basics by real soldiers, increasing the direct relationship between young Russians and their army. Analysts say that another traditional institution, the Orthodox Church, will be expected to take on a more active role in bolstering the state’s case in general, and in Ukraine in particular.

Vladimir Putin did not use the May 9 anniversary of victory over Nazi Germany to expand the military operation against Ukraine, or even offer any new explanations for it. But he did lead a massive parade of the “immortal regiment” through central Moscow, in which average Russians carried portraits of ancestors who fought in the Red Army during World War II, in what many commentators saw as a strong signal of ongoing social support.

According to a recent account in the daily Moskovsky Komsomolets of an online meeting between Moscow history teachers and Foreign Ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova, conversation centered around questions that might come up in the classroom, such as “Why did Russia attack Ukraine?” and “When will the military operation end?”

Ms. Zakharova stressed that students should be told that (in line with the official Kremlin position) the “war” has been going on for eight years, since the new Ukrainian Maidan government decided to attack separatist forces in the Donbas. She said that educators should say that after many attempts to find diplomatic solutions, Russia is now acting to bring that war to a conclusion in order to save the people of the two rebel republics. She also reportedly told teachers that the students should be told about what she called the Ukrainian government’s systematic efforts to repress the rights of Russian speakers in eastern Ukraine.

Reaching the younger generation

Some commentators see the early signs of what could become a permanent social mobilization for what Russian authorities increasingly view as a full-scale proxy war with the West in Ukraine.

“Patriotic education means the militarization of young people,” says Alexei Levinson, a professor at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow and senior researcher at the Levada Center. “Our youth is the group with the biggest share of people who demonstrate disloyalty, even if they are a minority in their own strata. If mobilized, these young people will go to fight not because of inner convictions, but because they are ordered to.”

Viktor Baranets, a former military spokesperson, argues that the changes are long overdue.

“The recent emphasis on improving patriotic education can be traced to the special operation that’s going on now,” he says. “The operation made patriotic education the No. 1 issue because of the numbers of people who stand against the policy of the state. It has become a litmus test of patriotism. When this operation is over, people coming back from the war will set things in order. They will not be ashamed of their patriotism.”

Several Moscow parents and former teachers consulted about the new emphasis on patriotic education said they see nothing wrong with flag-raising ceremonies and performing the national anthem, but at least one parent did object to military training in the schools.

Sergei Mitrokhin, a member of the Moscow Duma from the liberal Yabloko party, says the new programs violate Russia’s post-Soviet Constitution, which specifically rejects any form of state ideology.

“Our authorities know the younger generation doesn’t watch TV, so they are aiming to reach them through the schools,” he says. “This is all about the special operation in Ukraine, to spread aggressive propaganda into educational institutions. ... It won’t work. Young people don’t like having ideology forced upon them. They will reject it.”

Patterns

Poland given pass on rights violations because of Ukraine war role

Sometimes values are relative. The U.S. is turning a blind eye to Poland’s violations of democratic rights in light of the government’s central role in the anti-Moscow coalition.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Values are meant to be absolute. But there are times when they turn out to be relative.

Take Poland. Three months ago, Poland was a political pariah in Washington and in European capitals, facing sharp criticism for its violations of democratic principles and European Union rules regarding media freedom, the protection of minorities, and judicial independence.

Today, Warsaw is an increasingly pivotal ally in the fight against Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, and that reality overshadows any human rights concerns.

The security imperative has imposed itself. European leaders, and President Joe Biden, have muted their criticism of Poland and other self-professed “illiberal democracies” in eastern Europe, such as Hungary.

During the Cold War, Washington often allied itself – for security reasons – with undemocratic leaders around the world. But this latest trade-off comes on the heels of Mr. Biden’s insistence that the contest between democracy and autocracy is the defining struggle of our era.

French President Emmanuel Macron suggested last week that the West’s diplomatic blind eye will not last forever. Though a unified front against Russia may be Europe’s top priority now, he said, the Western alliance will ultimately rest on political foundations that only shared democratic values can provide.

Poland given pass on rights violations because of Ukraine war role

At first sight, the political map of Europe 10 weeks after Vladimir Putin launched his war on Ukraine would warm the cockles of any Western strategist’s heart. The view from 30,000 feet shows unprecedented levels of unity, both among European states and within the transatlantic NATO alliance.

Yet a closer look reveals another aspect of this newfound harmony, a kind of democratic paradox at the heart of the West’s response to the Russian invasion. It is most clearly evident in Poland, the NATO member on Ukraine’s border.

Three months ago, Poland was a political pariah in Washington and European capitals. Today, Warsaw is an increasingly pivotal ally.

Not long ago, Poland’s government was coming in for sharp criticism – and even being punished – for its violations of European Union principles and rules regarding media freedom, the protection of minorities, and judicial independence.

But the Ukraine invasion has overshadowed such concerns. The security imperative has imposed itself.

The war has forced Washington and its European allies to downplay their traditional emphasis on democratic political values in the interests of forging a unified front against Moscow and deterring Mr. Putin from any such attacks in the future.

EU leaders, including France’s Emmanuel Macron, who now holds the union’s rotating six-month presidency, have muted their criticism of Poland and other self-professed “illiberal democracies” on their eastern flank.

Mr. Biden, for his part, chose Warsaw’s Royal Castle for the major address of his European visit one month after the invasion. He praised Poland’s role in NATO as well as its generous welcome for hundreds of thousands of refugees.

And in extolling the importance of democracy he avoided singling out President Andrzej Duda, a political soul mate of Donald Trump. “It is not enough to speak ... of freedom, equality, and liberty,” Mr. Biden said. “All of us, including here in Poland, must do the hard work of democracy each and every day. My country as well.”

Both he and European leaders have also been moving to reduce prewar tensions with two other NATO member states – Hungary and Turkey – that had faced criticism both for their human rights records and their warm relations with Mr. Putin.

There is undoubtedly frustration over Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s reluctance to back stronger energy sanctions against Russia. Lithuania’s foreign minister, though not mentioning Hungary by name, this week denounced “one member state” for holding the others “hostage” over the sanctions issue. But otherwise, EU leaders have avoided criticizing the recently reelected Mr. Orbán, preferring to emphasize his explicit condemnation of the Ukraine invasion and his acquiescence in earlier EU sanctions.

Turkey is a key member of NATO, but one that has followed its own path. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan purchased a Russian anti-aircraft system in 2019, for example, prompting Washington to strike Turkey from the list of allies eligible to buy late-model F-35 fighter jets.

Mr. Erdoğan is threatening to block applications for NATO membership from Finland and Sweden because they’ve been hosting members of a Kurdish political party he regards as a “terrorist” organization. U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken is meeting his Turkish counterpart this week to try to smooth things over.

Washington is no neophyte when it comes to turning a diplomatic blind eye to the democratic failings of its allies in order to benefit from their security support. During the Cold War with the Soviet Union, successive U.S. administrations found themselves forging realpolitik partnerships with undemocratic leaders from Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines to Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza.

But the latest trade-off comes on the heels of Mr. Biden’s insistence that the contest between democracy and autocracy is of central importance in today’s world.

And it carries even greater resonance because of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s forceful framing of the war as a litmus-test battle between the aggression of an autocrat and his country’s defense of its young democracy.

EU leaders do seem to sense the need to reassert their founding commitment to democratic values once the war in Ukraine is over.

Mr. Macon has long emphasized the importance of such principles. And in a speech last week to the European Parliament he proposed the creation of a “European political community” that would “enable democratic European nations who adhere to our values to find a new space for political cooperation” even before they qualify for European Union membership.

His deeper message seemed to be that although a unified front against the Ukraine invasion may be Europe’s top priority for now, the staying power of the Western alliance will ultimately rest on the kind of political foundations that only shared democratic values can provide.

To which President Zelenskyy would no doubt add: These are the values for which his countrymen and women have proved ready to fight and even die.

A deeper look

How Florida became the leader in fighting fire with fire

When you use fires to forestall fires, the problem and solution may look identical. But planning and discretion distinguish controlled burns from wildfires – and help combat them.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

-

By Richard Mertens Contributor

With wildfire a growing scourge across the American landscape, one solution is more fire. Low-intensity, carefully managed fires can thin overgrown forests and reduce the buildup of fuels like pine needles, dead grass, fallen trees, and thick brush that produce more intense and destructive fires.

Florida is the leader of prescribed fire, or controlled burning, in the United States. Fire bosses like Sam Van Hook burn more land in Florida than in any other state – and until recently more than all of the Western states combined.

“You’ve got to fight fire with fire,” says Mr. Van Hook, a burn boss with 50 years of experience.

Today, he plans to burn 275 acres of grass, bushes, and small trees. There’s no town or highway for many miles downwind to be troubled by smoke. And yet the wind is rising, the humidity is low, and he wants to be careful.

Finally he decides: He’ll burn, but he’ll scale back in order to protect a forested area just to the east. “You’ve got to build in safety in burning,” he says.

Later, the blackened ground still smolders. The leaves of scorched myrtle bushes sag, dull and lifeless. Smoke hangs in the air.

“It burned off pretty decent,” he says.

How Florida became the leader in fighting fire with fire

Sam Van Hook is itching to burn. He has pulled on his boots, floppy white hat, and protective fire shirt, its bright yellow dulled by the smoke and ash of previous burns. He and his crew – his son, Zach, and a hired man named Franky Garcia – have used a tractor to bare a 6-foot-wide fire line around the 275 acres of grass, bushes, and small trees they plan to burn. They have filled their drip torches. Above all, they’ve got their fire permit in hand, granted that morning by a state forestry official.

And yet Mr. Van Hook hesitates. It’s still early, but the wind is already blowing hard across the DeLuca Preserve, 27,000 acres of semi-wild ranch land where he has conducted burns many times before. It bends the tall, brown prairie grasses and rustles the leaves of the wax myrtle bushes that are growing up too thick among them.

“It really needs to burn,” he says, half to himself.

Florida is the leader of prescribed fire, or controlled burning, in the United States. Fire bosses like Sam Van Hook burn more land in Florida than in any other state – and until recently more than all of the Western states combined. The Florida Forest Service says prescribed fire burns more than 2.1 million acres each year in the state. That’s about a fifth of the 10 million acres burned across the country in 2019, according to the most recent data published by the Coalition of Prescribed Fire Councils. The aim of all this burning is to maintain the state’s diverse ecosystems, including prairies, savannas, and pine flatwoods, but also to prevent more dangerous wildfires.

“You’ve got to fight fire with fire,” says Mr. Van Hook, a respected burn boss with five decades of experience. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy. Even as other places struggle to catch up with Florida, prescribed fire is getting harder in the state.

Wildfire is a growing scourge across the American landscape. In California and other Western states, a combination of prolonged drought and climate change have heightened the risk of uncontrollable and sometimes deadly fires. But it’s a problem in many other places. This spring, fires ravaged large areas of Nebraska, Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. Fires are increasing in the Arctic and sub-Arctic. And a February United Nations report warned that climate change and land-use change could increase wildfires 50% worldwide by the century’s end.

One solution is more fire. Fire experts, land managers, government agencies, and even the public have increasingly embraced the idea that the best defense against wildfires is regular burning. They say low-intensity, carefully managed fires can thin overgrown forests and reduce the buildup of fuels like pine needles, dead grass, fallen trees, and thick brush that produce more intense and destructive fires. But it’s also important to the land itself. Ecologists have long observed that many landscapes have been created by regular fire and need it to persist.

There is also a growing recognition of the importance of prescribed fire to endangered species. Mr. Van Hook has been burning areas of the DeLuca Preserve that are home to the endangered Florida grasshopper sparrow. In the West, scientists have suggested that even the northern spotted owl, once the focus of a bitter fight over the logging of old growth forests in the Northwest, needs a landscape shaped by fire.

Florida’s familiarity with fire

For much of the 20th century, the federal government worked to suppress fire. Now, the importance of prescribed burning is the new orthodoxy in forestry circles. But it’s one thing to embrace an idea and quite another to carry it out. In many places, that’s the struggle today.

In Florida, prescribed burning never really stopped. It’s an old tradition that mimics the work of nature itself. Most of the landscapes of Florida – and the rest of the southeastern states – have been shaped by frequent fire. (It’s not a coincidence that Florida ranks high in lightning, too.) Native Americans and early settlers burned their lands. Fire also was important to the plantation landowners who hunted bobwhite quail, a small and much-loved game bird that lives on lands subject to frequent fires. It was critical to ranchers, who used it to keep woods and prairies open and to encourage the tender young grass that cattle love. And it’s been used widely in agriculture, to burn away sugar cane and clear tomato fields.

“All the federal agencies began their turn away from fire suppression in Florida,” says fire historian and Arizona State University Professor Emeritus Stephen Pyne. “Florida has been a remarkable story and made possible the revolution in fire policy when it happened.”

Florida law also makes prescribed burning easier by reducing the legal liability for those who do it. Trained and certified “burn bosses” are liable for mistakes only if they show “gross negligence.” California adopted this standard last year, to the acclaim of conservation groups and prescribed fire advocates. Florida did it 32 years ago.

Meanwhile, tradition has given birth to influential institutions in the world of fire. The Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy in Tallahassee, established on an old quail plantation in 1960, is a national leader in the research and promotion of prescribed fire. And people come from all over the United States – and the world – to learn how to burn at the National Interagency Prescribed Fire Training Center in Tallahassee. Florida is also the birthplace of prescribed fire councils, organizations formed to promote burning, especially among private landowners. These councils have since expanded to 33 states.

“We’re a half century behind,” says Jeb Barzen, a fire ecologist and founder of the Wisconsin Prescribed Fire Council. “Florida is more densely populated than the Midwest, yet they burn more than us. Wisconsin burns 50,000 acres a year. We need to be doing a million acres a year. … Florida is able to do it. There are a lot of lessons that we can adapt to the Midwest.”

Maybe Florida’s biggest advantage is a vast human infrastructure developed to carry out prescribed burning. This includes thousands of burn bosses like Sam Van Hook, many of whom grew up burning on their ranches and are simply carrying on an old practice.

Growing struggles over burning

Despite its long history and deep cultural roots, burning in Florida today is strictly regulated. A trained and certified burn boss is required to plan and supervise a burn, which can range from hundreds or even thousands of acres to just a few wild acres in a city. Whatever the size, burn bosses need a permit from the state forest service, which works with them to identify areas that may be safely burned and consults meteorological data – especially wind speed and humidity – and model smoke plumes to determine when conditions are safe.

Yet despite its success with prescribed burns, Florida isn’t an easy example to follow. Florida is flat and humid, with water on both sides. Smoke blowing east or west quickly drifts out over the Atlantic Ocean or Gulf of Mexico. In the West it drifts over the whole country. Also, dryness and mountain topography make prescribed fire much more difficult than in Florida.

And sometimes things go wrong even in Florida. Smoke is the biggest problem. In March, three people died on Interstate 95 in eastern Florida when smoke from a prescribed burn mixed with fog – not uncommon with Florida’s humidity – and caused five accidents. In 2012, 11 people died on Interstate 75 in accidents also caused, in part, by smoke from prescribed burning.

Moreover, even as prescribed fire gains traction elsewhere, it’s meeting new challenges in Florida. The state is among the fastest growing, and newcomers often lack the same tolerance for fire as natives. Managing public relations has become as important for burners as understanding wind speed and humidity.

“We’ve been doing it a long time,” says Reed Noss, an ecologist who has written a book on fire in Florida. “It’s established here. But it’s in danger here. So many people are moving into Florida from the Northeast and Midwest, where fire isn’t accepted. They find it scary. They don’t like the smoke.” He adds, “With this new population, it’s going to be a challenge to burn as much as we have.”

Russell Priddy, a rancher in south Florida agrees. He puts up signs on the roads when he burns to warn residents of a nearby planned community. But his burns provoke more complaints than ever. He says he can’t do one without people who don’t understand it making alarmed calls to the local fire department.

“I’m afraid in three to five years we won’t be able to burn at all,” he says.

Mr. Van Hook, too, says he’s facing more restrictions. He’s a short, energetic man with white hair, drooping white mustache, and skin weathered by years of sun and smoke. Unlike many in Florida who do prescribed burning, he did not grow up doing it. Instead, he went to college, took a course in burning, and fell in love with it. He worked for three decades on the Avon Park Air Force Range, then started his own company.

“In this work, everything gets harder rather than easier,” he says. Still, on almost every day, he says, he can find a place that is safe to burn.

Today, on the DeLuca Preserve, he sees both sides: The patch he wants to burn needs it. Bushes and trees – wax myrtles, willows, palmetto palms – are growing up on “semi-improved” pasture, a mixture of prairie and planted grasses not uncommon in Florida. There’s no town or highway for many miles downwind to be troubled by smoke. And yet the wind is rising, the humidity is low, and he wants to be careful.

Finally he decides: He’ll burn, but he’ll scale back in order to protect a forested area just to the east.

“You’ve got to build in safety in burning,” he says. “And you learn that by messing up.”

Everything happens quickly now. His son and Mr. Garcia have already worked their way along the downwind side of the area, lighting a backfire that will help contain the burn. Now they circle around to the upwind side in their big four-wheeler. As they bounce along, Mr. Garcia extends his lighted drip torch, leaving a small trail of fire flickering in the grass behind them. In some places it smolders and dies. In others it flares up, the tongues of flame devouring dried grass and old thatch and sending billows of white and gray smoke high into the air and slanting southward with the wind.

Mr. Van Hook looks on with quiet pleasure. Later, he rides over what’s left of the burn. The blackened ground still smolders. The leaves of scorched myrtle bushes hang dull and lifeless. Smoke drifts in the air. A smile flickers across his face.

“It burned off pretty decent,” he says.

Books

Lively guests: Invite the 10 best books of May into your home

Our picks for this month include books that cut through stereotypes, confront the legacy of colonialism, charm with humor, and illuminate a bold and far-reaching experiment by Benjamin Franklin.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Staff

Good books can be sought-after companions to enliven our days. Such visitors bring gifts of countries and cultures different from our own, of new ideas, or of alternative ways of looking at things.

Sometimes those literary guests pull us into the realm of the fantastical – women turning into dragons – to make a point, or bring us down to earth with their eloquent descriptions of the rural American South, for example. We see into the poverty, silence, and art that turns our preconceptions on their head.

In two biographies, we witness the foresight of Benjamin Franklin and the early glimmerings of populism in the presidency of Andrew Jackson. We connect the 19th-century demand for peanut oil in Europe with the continuing practice of slavery in West Africa, after it was declared illegal. And we discover the beauty of the high Sierra in California through the brilliant descriptions of a science fiction writer.

Lively guests: Invite the 10 best books of May into your home

The books recommended by our reviewers take readers across the globe, from the hills of Kentucky in the United States to the streets of Cape Town, South Africa. The eclectic settings also include the coast of Ireland and the peanut farms of Senegal.

1. The Book Woman’s Daughter by Kim Michele Richardson

The beguiling sequel to “The Bookwoman of Troublesome Creek” introduces Honey Lovett, teenage daughter of librarian Cussy Mary, who continues the family tradition of delivering books to far-flung neighbors in rural Kentucky with the Pack Horse Library Project. The novel abounds with Appalachian voices, imagery, and lore, paying homage to this community’s bright strength of spirit amid harsh landscapes, poverty, and prejudice.

2. When Women Were Dragons by Kelly Barnhill

In 1955, nearly 650,000 American women turn into dragons and take to the skies. The event’s repercussions come into focus through the recollections of Professor Alex Green, snippets of scientific scholarship, and firsthand accounts. Kelly Barnhill’s poetic, pointed tale tackles the era’s pervasive silence concerning all things female.

3. The Dark Flood by Deon Meyer

Detective Benny Griessel and his partner Vaughn, demoted and reposted to a wealthy South African town, track a seemingly mundane missing-person case that unearths gang ties and police corruption. Packed with cars, confrontations, and local slang, the fast-paced book excels when the detectives’ easy patter and cooperation get a chance to shine.

4. The Colony by Audrey Magee

Villagers on a remote island off the Irish coast are visited in the summer of 1979 by a British painter and a French linguist. Against the drumbeat of violence in Northern Ireland, author Audrey Magee juxtaposes an exploration of art, language, and love.

5. Book Lovers by Emily Henry

Nora Stephens travels with her sister to a picturesque town for a vacation. The last person she expects to see is her nemesis – the editor who rejected her client’s manuscript. Readers already know the pair will fall in love, but Emily Henry’s talent infuses the romantic comedy with layers of delight.

6. Slaves for Peanuts by Jori Lewis

Jori Lewis resurrects voices silenced by history in this sumptuous journey beginning in 19th-century Senegal. Traveling down the coast of West Africa, the story sweeps through medieval kingdoms to bustling colonial capitals. By digging through historical archives and oral histories, Lewis unearths a neglected part of the Atlantic slave trade, all wrapped around the humble peanut crop.

7. Nasty, Brutish, and Short by Scott Hershovitz

Scott Hershovitz’s delightful debut manages to be fun, funny, and intellectually rigorous all at once. The law and philosophy professor tackles serious topics including morality, rights, and conceptions of truth and knowledge, framed by amusing conversations with his two young sons. (Full review here.)

8. Benjamin Franklin’s Last Bet by Michael Meyer

In the last days of his life, Benjamin Franklin changed his will and funded a 200-year experiment: He left the cities of Boston and Philadelphia money to be lent to help tradesmen start businesses. In this engaging book, Michael Meyer skillfully weaves together a biography of Franklin and his heirs with the story of what happened to the money.

9. The High Sierra by Kim Stanley Robinson

Award-winning science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson tackles a more earthbound subject in this personal guide to the planet’s “best hiking mountains.” Combining backpacking advice, geological history, intimate recollections, and breathtaking photography, this eclectic compendium will appeal to a range of adventurous readers.

10. The First Populist by David S. Brown

Andrew Jackson, seventh president of the United States, styled himself a “man of the people.” Calling Jackson “the country’s original anti-establishment president,” historian David S. Brown offers a timely assessment of Jackson’s controversial career, in the context of the American populist tradition.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Biden’s bid to boost Somalia

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The Biden administration said Monday that it would redeploy hundreds of American troops to Somalia to help contain a threat from Islamist insurgents. A day later, it said it would provide $670 million in emergency food assistance to the East African country and its neighbors. Announcements like those may feel perennial. The Horn of Africa has faced overlapping conflicts and food insecurity for decades that needed outside intervention. Somalia hasn’t had a strong central government in three decades.

Yet the United States outreach may be recognition of something more than security and humanitarian interests: a new alignment of shared democratic values. The U.S. pledges of guns and butter to Somalia came after the country’s first successful democratic elections in half a century on May 15 and an immediate peaceful transfer of power.

Once a case study in state failure, Somalia is now offering a credible argument that societies, like individuals, have the capacity for self-renewal based on ideals that are all-embracing. The Biden administration has taken note.

Biden’s bid to boost Somalia

The Biden administration said Monday that it would redeploy hundreds of American troops to Somalia to help contain a threat from Islamist insurgents. A day later, it said it would provide $670 million in emergency food assistance to the East African country and its neighbors. Announcements like those may feel perennial. The Horn of Africa has faced overlapping conflicts and food insecurity for decades needing outside intervention. Somalia hasn’t had a strong central government in three decades.

Yet the United States outreach may be recognition of something more than security and humanitarian interests: a new alignment of shared democratic values. One of the most challenging riddles since the end of the Cold War has been how to rebuild states that fall apart. Somalia was the first to pose the problem after the collapse of a longtime dictatorship in 1991. Now it may be charting a road map back to stability for other faltering countries like Libya and Yemen.

The U.S. pledges of guns and butter to Somalia came after the country’s first successful democratic elections in half a century on May 15 and an immediate peaceful transfer of power. That achievement was often in doubt. The ballot was delayed more than a year by political disagreements and violent clashes in the capital, Mogadishu. The jihadist group Al Shabab stepped up attacks on civilians.

That sort of fragmentation has often derailed internationally brokered attempts at state building, especially in societies defined by strong and often rival clans. But in the past decade, Somalis have gradually adapted democratic practices to their own traditional social norms.

“A silver lining in the jostling,” the Africa Center for Strategic Studies in Washington observed, “is that Somalia is forging, in fits and starts, a system of checks and balances on its executive branch and an open debate about what a free and fair electoral process entails.”

The decision to redeploy U.S. troops to Somalia points to an important dividend of democratic progress. Washington and Somali leaders share a common basis for reining in Al Shabab. That contrasts with a breakdown in counterinsurgency cooperation in West Africa. Earlier this year, France began withdrawing its forces from Mali over friction with the military government.

When Somalia’s Parliament elected Hassan Sheikh Mohamud as president on Sunday, the process fell short of the goal to one day restore universal, direct elections. But it reflects a brick-by-brick approach to someday creating a popular central government with authority over the whole country.

There’s more to that than meets the eye. One effect of Somalia’s long political crisis is a vast and Western-educated diaspora. Many members of Parliament are former refugees who carry more than one passport. They reflect the growing sensibilities and expectations of a predominantly young population. That presents both urgency and promise. Radicalization of youth by groups like Al Shabab is fueled by frustration, but the progress in elections has nurtured hope.

“Somali politics, however dysfunctional, self-adjusts,” Hodan Ali, a senior adviser in the mayor’s office in Mogadishu, told the Kenyan newspaper The East African. “We see Mogadishu yearning for change and buzzing with possibilities.”

Once a case study in state failure, Somalia is now offering a credible argument that societies, like individuals, have the capacity for self-renewal based on ideals that are all-embracing. The Biden administration has taken note.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The zeal that heals

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Tony Lobl

When we let the light of Christ, rather than a personal agenda, animate our thoughts and actions, we and others are benefited.

The zeal that heals

Popular thought tells us to follow our passion. Yet, it’s easy to be passionately wrong! We can fall head over heels for someone who turns out to be a complete mismatch, fixate on one side of a political question that has a thousand nuances, or be so convinced of our religion’s rightness that we commit all kinds of wrong in order to force it on others.

A Bible story (see Acts 9:1-20) exemplifies the latter. Saul, a zealous Jew, passionately persecuted fellow Jews who followed the teachings of Jesus. Yet, Saul’s heart must have been primed to live the life of healing-not-hating espoused by the early Christians he hounded, because that’s what happened. Startled by a spiritual vision that opened his eyes to the wrongness of his self-righteous actions, he lost his sight, until a Christian named Ananias opened his eyes not just physically, but also spiritually – to the power of Christ – and he literally saw anew.

But even as his deeper, spiritual blindness was overturned, Saul’s zeal didn’t diminish. It was instead elevated from stridently desiring to change others to zealously allowing himself to be transformed by the Christ, the spiritual idea of God that he was now embracing. The Christ-spirit, in turn, empowered him to boldly, but lovingly, spread far and wide the good news of humanity’s redemption through Christ.

This divergence of merit in how zeal finds expression is pinpointed in a glossary of Bible terms in Mary Baker Eddy’s “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures.” Using key synonyms that identify aspects of the divine nature, the discoverer of Christian Science describes a spiritually motivated zeal as “the reflected animation of Life, Truth, and Love.” Conversely, materially minded zeal is “blind enthusiasm; mortal will” (p. 599).

The first of these was exemplified by Christ Jesus. Animated by Life’s divine energy, by Truth that always perceives God’s perfect creation, and by Love that holds all humanity in its heart, Jesus healed those suffering from severe sickness and transformed hardened sinners. Such God-reflecting animatedness still heals. That is, it brings to light, for us and others, spiritual reality, including the health and harmony native to everyone’s nature as God’s offspring.

The same can’t be said about being blindly enthusiastic or acting willfully. These traits move our lives, and the impact of our lives on others, in the wrong direction. We lose sight of life as it really is – divine Life, God, who is ever-present, all-blessing Love. And we lose sight of what we each are as the expression of the Life that is Love. So it makes sense to pray – to silence human will – and ensure that it’s the influence of all-embracing Love impelling us forward before letting fervent thoughts form our words or deeds.

Such prayer steers our thoughts, words, and actions toward Christly zeal, which is inseparable from a devotion to being of benefit to others. This is key when endeavoring to impress upon others the blessings of one’s faith, which Jesus expected his followers to do. He said: “Everyone who lights a lamp puts it on a lamp stand. Then its light shines on everyone in the house. In the same way let your light shine in front of people. Then they will see the good that you do and praise your Father in heaven” (Matthew 5:15, 16, GOD’S WORD Translation).

A lamp isn’t put on a lamp stand to impress others by being visible to them but to bless others by creating visibility for them. So, we can check our zeal for sharing our light against Jesus’ timeless guidance. Does what we think, say, and do result in others experiencing the healing impact of understanding spiritual reality and lead to their heartfelt praise for healing’s source, God?

To ensure that this criterion is satisfied, our key contribution is an inner zeal – a continuous, fervent commitment to rise above our own mistaken material perceptions of reality. Then the light we inherently reflect as divine Love’s spiritual image will shine through our lives and illumine practical opportunities to lovingly offer others inspiration that heals rather than harms.

This Christ light reaches and liberates even those trapped in self-imprisoning passions. That’s true whether these play out in poor relationship choices or in political, religious, or other zealotry. Like Saul, everyone has a heart inherently primed to come alive to, and be animated by, the all-embracing divine Life and Love that injure none and benefit all. We can be fervent in our desire to help that happen.

GOD’S WORD®. © 1995, 2003, 2013, 2014, 2019, 2020 by God’s Word to the Nations Mission Society. Used by permission.

Adapted from an editorial published in the May 16, 2022, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Lights of remembrance

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow when we take a look at secretary of state elections that are heating up and what that tells us about the war over democracy.