- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- In GOP vs. GOP recount, Pennsylvania officials battle to restore trust

- To ‘reset’ British politics, a party leader stakes it all on integrity

- How to stay safe on the migrant trail? Read a newspaper.

- Beach and river cleanups: Strange finds, and fish fertilizer for sale

- Fly-fishing, silence, and common ground: A stepfather’s gift

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A celebration of achievement: Why St. Augustine’s Class of 2022 dances

New Orleans often showcases overcoming adversity (hurricanes) and exemplifies jubilation (Mardi Gras). In that sense, one graduation class is a mirror of its hometown.

A video of the 7th Ward’s St. Augustine High School graduates dancing in their purple gowns is going viral.

They’ve got a lot to celebrate.

The entire senior class (100 young men) has been accepted into college (and one is joining the U.S. military). That alone isn’t unusual. School officials say this is the 11th consecutive year of hitting that mark. (The national average is a 62% college acceptance rate among high school grads.)

But there’s more. This year’s graduates of the private prep school also secured a school record $9.2 million in scholarships. (That’s an average of $92,000 per student.)

And this senior class has shown resilience. Like many across the country, St. Augustine students pushed through a year of remote classes due to the pandemic. They were also forced to take a 2½-week virtual break thanks to Hurricane Ida (last fall). That was followed by loss of athletic facilities after a fire in the gymnasium. “They’ve faced adversity ... and crossed the finish line with a sense of purpose,” says Mel Cordier, director of communications at St. Augustine. And he notes, the scholarship tally “says a lot about their perseverance.”

As a Roman Catholic boys’ school, character building is a core principle. “We lead with Christ. We pray before and after every class,” Mr. Cordier says. An expectation of excellence, he says, produces young Black men who “know that whether it’s at a job interview, on the basketball court, or pursuing a college scholarship, you belong in that space.”

Today, they own the space of joy.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

In GOP vs. GOP recount, Pennsylvania officials battle to restore trust

A contested GOP primary race in Pennsylvania highlights the continuing distrust, especially among Republican voters, in U.S. elections. Is the electoral process broken or just misunderstood?

As Pennsylvania kicks off a statewide recount for its razor-thin GOP Senate race, election officials here are managing the effort against an unprecedented backdrop of distrust in the electoral process.

Former President Donald Trump’s relentless claims that the 2020 election was fraudulent – claims that were refuted by his own attorney general and top security officials – have pushed Republican voters’ trust in U.S. elections to record lows. And during the current cycle, questions of “election integrity” have shaped Republican primaries.

Mr. Trump’s fraud claims have led many states to pass new laws tightening voting procedures. Even more impactful, however, may be the extent to which they have primed many GOP voters to question close election results going forward – including in contests between Republicans, as is the case in Pennsylvania.

Here in Berks County, officials say the pervasive atmosphere of distrust has made far it more difficult for them to do their jobs, even as the critical nature of those jobs has been underscored.

“They get sworn at – but they still come in every day,” says Berks County Commissioner Kevin Barnhardt, speaking of election employees. “They’re trying in some small way to restore faith in the voting process.”

In GOP vs. GOP recount, Pennsylvania officials battle to restore trust

Nearly two hours into the meeting, Berks County Commissioner Kevin Barnhardt loses his cool.

Mr. Barnhardt and his fellow commissioners had gathered to hear complaints about Pennsylvania’s Republican primary election, in which Trump-endorsed Senate candidate Dr. Mehmet Oz and former hedge fund CEO David McCormick are currently separated by fewer than 1,000 votes. With a recount beginning June 1, both campaigns have been clawing at the margins – as evidenced by the two lawyers shuffling their stacks of paper-clipped files before Berks’ top election officials.

The first complaint has to do with extended poll hours. After some precincts had equipment trouble, a judge ruled that county polling stations would stay open one hour later. Not fair, says a lawyer with the McCormick campaign – polls were only supposed to be open for 13 hours. (Of note: In-person ballots have slightly favored Dr. Oz.)

The next complaint is over several hundred absentee ballots that were returned on time but without a date on the envelope. Counting them would clearly violate the rules, says a lawyer with the Oz campaign, since voters were instructed to date their envelopes. (Mail-in ballots have slightly favored Mr. McCormick.)

But when the discussion turns to the appropriate distance for observers to witness election employees at work, Mr. Barnhardt’s patience finally wears out.

“It’s gotten to the point of lunacy with some of these things we’re discussing,” he erupts. “The ludicrousness ... of considering plugging in a camera similar to what ESPN does at football games is asinine.”

“This is not the Democrats and Republicans; it’s the Republicans demanding changes,” Mr. Barnhardt, the sole Democrat on the board, adds. “If you think you’re going to stand there and look at someone’s envelope and look at someone’s ballot – forget about it.’”

As Pennsylvania kicks off its statewide recount and works through court challenges surrounding the razor-thin GOP Senate race, election officials here, as elsewhere, are managing these efforts against an unprecedented backdrop – one in which even mundane clerical tasks are seen through a lens of deep distrust in the electoral process.

Former President Donald Trump’s relentless claims that the 2020 election was fraudulent – claims that were refuted by his own attorney general and top security officials, along with more than 60 court rulings upholding Joe Biden’s victory – have pushed Republican voters’ trust in U.S. elections to record lows. During the current cycle, questions of “election integrity” have shaped Republican primaries, with scores of candidates promising to fix what they allege, contrary to evidence, is a broken system.

Mr. Trump’s fraud claims have already led many states to pass new laws tightening voting procedures. Even more impactful, however, may be the extent to which they have primed many GOP voters and officials to question election results going forward – particularly when a contest is close, and even when it is solely between Republicans, as is the case in Pennsylvania.

If the campaigns continue to foment distrust in the results, that could have serious consequences in the battleground state, seen as crucial to control of the Senate. The Democratic candidate, Lt. Gov. John Fetterman, won his primary handily, and the GOP will need its voters in the fall.

“[Republican voters] have been lied to for so long and told repeatedly that what is a good election process is bad,” says David Becker, executive director of the nonpartisan Center for Election Innovation and Research, a nonprofit that works with election officials from both parties to improve election administration. “You can understand how they would doubt elections.”

Here in Berks County, officials say the atmosphere of distrust has made far it more difficult for them to do their jobs, even as the critical nature of those jobs has been underscored.

“They get hung up on, they get sworn at – but they still come in every day,” says Mr. Barnhardt in his office after the meeting, speaking of employees counting ballots several floors below. “They’re trying in some small way to restore faith in the voting process.”

Too close to call

In the Election Services office for Berks, one of Pennsylvania’s most populous counties, paper ballots are sorted into towering columns of blue boxes. The 12 full-time employees, along with other workers filling in during the tabulation process, move seamlessly around the stacks.

Most decline to speak on the record, citing fear of harassment from their own community – an increasingly common problem. According to a poll commissioned by the Brennan Center, 1 in 3 elections officials now say they feel unsafe in their jobs, and 1 in 5 cite threats to their lives as a job-related concern.

Berks County hired a new elections director in February, its third since 2020. Before 2020, Mr. Barnhardt had worked with one director during his entire 15-year tenure as commissioner. Pennsylvania officials say this is a statewide trend, estimating that more than 30 counties have lost their elections directors over the past two years.

Not only are these workers still facing harassment over the 2020 elections – a county employee says the office still fields calls from voters demanding they overturn the results – but they are also facing new scrutiny, and now the pressure of a statewide recount.

While Lieutenant Governor Fetterman won the Democratic Senate primary with almost 60% of the vote on May 17, the Republican race for Pennsylvania’s open seat has been hotly contested. After Mr. Trump’s initial endorsee, Sean Parnell, dropped out in November amid domestic abuse allegations, the race closed in around former TV show host Dr. Oz and Mr. McCormick, an Army veteran and former head of the investment company Bridgewater Associates.

On Election Day, after a turnout of more than 1.3 million votes, the race was too close to call. By May 26, the margin between Dr. Oz and Mr. McCormick had shrunk to 922 votes, triggering a statewide recount.

In a post on his social media site Truth Social the day after the election, Mr. Trump urged Dr. Oz to “declare victory,” adding that doing so would make it “much harder for them to cheat with the ballots that they ‘just happened to find.’” While he held off doing so at first, Dr. Oz released a video on Twitter Friday saying he has earned “the presumptive Republican nomination for the United States Senate.”

The move reminded many here of Mr. Trump claiming victory on election night in 2020, well before all mail-in ballots had been tabulated.

“Republicans just cry a lot if they don’t win,” says Patty Blatt, a Democratic voter with a Biden 2020 flag still hanging from her porch outside Reading. “This all just sounds like the Republican calling card at this point.”

“The system is working exactly as it should”

In a call with reporters Tuesday, a senior official with the McCormick campaign expressed a lack of confidence in the recount, complaining about slow reporting of results in the original tally – which isn’t finished in many parts of the state, even as the recount begins.

“We’re doing a recount of a count that we don’t know the results of yet,” said the official.

The McCormick campaign has filed a lawsuit against election officials, arguing for almost four hours in court on Tuesday that 860 mail-in ballots missing a date on the exterior envelope should be counted because they were “indisputably submitted on time,” as evidenced by the stamp upon receipt. After the hearing, the U.S. Supreme Court issued an emergency stay while it decides if it will hear an appeal.

Dr. Oz’s lawyers contend that counting these 860 undated ballots would be “changing the rules” in the middle of an election – a decision that would further undermine voters’ confidence in the process. Berks County Commissioner Christian Leinbach, one of Mr. Barnhardt’s two Republican colleagues, seems to echo this view during the meeting with lawyers for the two campaigns.

“We’re in a very difficult era for U.S. elections. More and more of what is ultimately deciding elections is not the vote or necessarily the law, but rather the results of litigation,” says Mr. Leinbach. “This is troubling, and potentially dangerous for the republic.”

But litigation isn’t actually a problem, counters Mr. Becker of the Center for Election Innovation and Research. While tedious and time-consuming, the automatic recount and ongoing court cases in Pennsylvania are all legitimate parts of the democratic process that serve to reinforce trust in results. The problem is the politicians who have encouraged voters to question these standard electoral procedures.

“We have had multiple years of delegitimization of a secure process by a losing candidate, and now voters are being misled into thinking something is awry,” says Mr. Becker. “This is an election with a very narrow margin, and the system is working exactly as it should.”

Michael Taylor, acting solicitor for Chester County’s GOP, agrees that the current drama in Pennsylvania mostly reflects the closeness of the Senate race. But he also believes the 2020 election has colored how Republican voters see the entire process.

Mr. Taylor expresses a view repeated by many local officials: He believes the election results in his jurisdiction were fair and valid, and any claims to the contrary simply reflect voters’ lack of understanding of the process. But that doesn’t mean fraud didn’t take place in a different part of the state – or country.

“The questioning of mail-in ballots greatly stems from 2020. [Voters] saw what happened, and it gave them all these questions,” says Mr. Taylor.

He adds that almost all of the Chester County GOP meetings now include voters who come and ask procedural questions for upward of an hour. “We had a bunch of [poll] watchers come in for this election, and I tell each of them that come in that you have two jobs: If you see something, say something, but more importantly, then go back out to your friends and family and talk about your experience so they understand.”

But then he adds another directive.

“I also said to the watchers who came in: Think of this as a practice round for November, when there are more ballots – and the pressure is greater.”

To ‘reset’ British politics, a party leader stakes it all on integrity

In the U.K., two political leaders have been accused of violating pandemic rules. Our reporter looks at how British voters weigh the importance of moral integrity versus competency.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson is once again facing calls to resign, including from members of his own party, as the latest revelations around the Partygate lockdown violation scandal come to light. At the same time, his rival in the Labour Party, party leader Sir Keir Starmer, is also facing a reckoning over a possible violation of the lockdown rules.

But where Mr. Johnson has fought tooth and nail to avoid any political consequences for his violations, Mr. Starmer is facing the issue head-on: He promised to resign as Labour leader if fined by police.

Mr. Starmer’s response to the legal peril he is in is not simply a political gamble, experts say. Though Mr. Starmer’s promise to abide by his morals does paint a stark contrast with Mr. Johnson’s cagier responses to Partygate, they say that Mr. Starmer is also making a bigger claim about how politics can be conducted today.

“Voters are disgusted and suspicious of politics,” says Eunice Goes, professor of politics. Their doubts have paved the way for the Labour leader “to make the case for competence, clean politics free of corruption, and of strengthening institutions.”

To ‘reset’ British politics, a party leader stakes it all on integrity

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson and his Conservative Party can’t seem to escape the Partygate scandal.

After months of lying dormant, the controversy over parties held by Mr. Johnson’s government, in violation of its own COVID-19 lockdown rules, roared back on to the public stage last week with the publication of a new report and previously unseen photos of the prime minister at an office party where drinking was going on. Mr. Johnson has offered increasingly strained defenses for his behavior, and now risks being ousted by his own party due to his appearing to have lied to Parliament.

At the same time, his rival in the Labour Party, party leader Sir Keir Starmer, is also facing a reckoning over a possible violation of the lockdown rules. But where Mr. Johnson has fought tooth and nail to avoid any political consequences for lockdown violations, Mr. Starmer is facing the issue head-on: He promised to resign as Labour leader if fined by police.

The response by Mr. Starmer, a former top government prosecutor, to the legal peril he is in is not simply a political gamble, experts say. Though Mr. Starmer’s promise to abide by his morals does paint a stark contrast with Mr. Johnson’s cagier responses to Partygate, they say that Mr. Starmer is also making a bigger claim about how politics can be conducted today.

“Voters are disgusted and suspicious of politics,” says Eunice Goes, professor of politics at Richmond, The American International University in London, citing recent allegations of sexual abuse, bullying, and misogyny from Tory members of Parliament. Their doubts have paved the way for the Labour leader “to make the case for competence, clean politics free of corruption, and of strengthening institutions.”

The highest standards

Mr. Starmer’s political peril stems from an incident on April 30 last year, over a year into Britain’s COVID-19 lockdown measures banning indoor gatherings, when he and a group of political aides sat down with a takeaway curry in Durham, northeast England.

On the back of a complaint filed by Durham’s Conservative MP, local police are investigating a possible breach of the law. The Labour leader insists what took place was legal; a rounding up of colleagues after a day of local campaigning.

But Mr. Starmer raised the stakes by declaring that he “would, of course, do the right thing” and resign if fined for wrongdoing. That is meant to highlight the difference between himself and Mr. Johnson, who has refused calls to resign after being fined when officials, including Chancellor Rishi Sunak, gathered indoors to sing “Happy Birthday” to the prime minister despite strict lockdown rules. The Partygate-rooted offense earned Mr. Johnson the distinction of being the first prime minister to be sanctioned for breaking the law while in office.

“This matters ... because the British public deserves politicians who believe the rules apply to them,” said Mr. Starmer, pointing the finger clearly at the prime minister’s behavior. “They deserve politicians who hold themselves to the highest standards. ... They will always get that from me.”

The Labour leader’s decision looks to be in keeping with his background as a lawyer and Britain’s director of public prosecutions, one of the country’s top prosecutorial jobs. In that role, Mr. Starmer introduced measures to prosecute female genital mutilation, reformed guidelines over how police should handle sexual abuse investigations, and defended the Human Rights Act when the Conservative Party proposed repealing the legislation.

He has featured that sense of justice in politics, presenting himself as a steady pair of hands ready to take on the mantle of prime minister. “His whole message is about reassurance, that he’s not the former, radically far-left Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, or Boris Johnson,” says Dr. Goes.

Mr. Starmer’s image is the antithesis of Mr. Johnson’s bombastic style, priding himself on “professionalism and competency,” says Tim Bale, professor of politics at Queen Mary University of London.

A real opportunity for change?

Whether that will matter to the public is not clear. The pandemic appeared to change the rules for what’s acceptable behavior from British government officials, and Mr. Johnson has been able to maintain his tenure as prime minister.

Cynicism pervades, “a lot of it generated by this government,” says Dr. Bale. “It seems everybody has been tarred by the same brush.”

That’s not simply a result of Mr. Johnson’s doings, but a long-term trend of mistrust stretching back to the expenses scandal over a decade ago, which saw almost daily revelations of members of Parliament using public money on anything from second homes to houses for ducks. Trust in politicians hasn’t recovered much since then.

And while Mr. Starmer prosecuted some of the MPs in the expenses scandal – including members of his own party – that doesn’t mean the public sees him as a solution to today’s dirty politics. “They’re not really inspired by him. Though they’re fed up with Boris Johnson, they don’t think Starmer is the alternative,” says Dr. Bale.

Still, Mr. Johnson has opened a door for Mr. Starmer’s appeal to voters’ sense of right vs. wrong via the prime minister’s plan to seize control of a parliamentary anti-corruption watchdog, allegations of party donors paying for the refurbishment of the prime minister’s residence, and other scandals.

“Do voters still value honor and integrity?” asked The Guardian’s political commentator Andrew Rawnsley. “Sir Keir Starmer is staking his career on it.”

Though even if he loses his career, Mr. Starmer might still “ironically” reset British politics by resigning. “One person is seen as having the guts and decency to fall on their sword if they’re caught out,” says Dr. Bale. Establishing Labour as a clean-cut brand could get a lot of voters to look at the party again.

The worst outcome for Mr. Starmer, Dr. Bale adds, may actually be a middle ground, where the police judge that the Labour leader acted unlawfully but decide not to fine him. In that case, Mr. Starmer could keep his job on a “legal” technicality.

That could seem like more of the same self-interested politics, says Dr. Bale. “If he hangs on, he’ll look like any other politician as far as the public is concerned.”

How to stay safe on the migrant trail? Read a newspaper.

Trustworthy info is rare on the U.S.-Mexico border. But migrants need it to make safe decisions amid swirling rumors, predatory crooks, and ever-changing policies. Our reporter profiles a news outlet built for migrants.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Migrants and asylum-seekers heading north to the Mexico-U.S. border are a particularly vulnerable group of people. They are in unfamiliar lands without friends or family to turn to, they are unprotected from criminals and traffickers, and they have to cope with complicated rules and regulations that can change from one day to the next.

They need information and advice, which is why a group of Mexican and U.S. journalists founded El Migrante, a monthly six-page newspaper full of practical tips, useful phone numbers, and guidance on how migrants can exercise their rights.

There are smartphone apps and Facebook pages that do the same sort of thing, answering questions directly and helping migrants sift genuine information from the storm of fake news and misleading rumors that swirl around the internet.

“I want to know how to navigate this labyrinth,” one migrant told Karla Castillo Medina, a founder of El Migrante. Her project, and others like it, help migrants make informed decisions that keep them safe. Says Monica Vázquez, an official with the United Nations refugee agency, “Information is protection.”

How to stay safe on the migrant trail? Read a newspaper.

Karla Castillo Medina goes door to door at the migrant shelter, delivering newspapers like an old-fashioned newsie.

“Good afternoon! Anyone home? I’m just dropping your paper here,” she calls out as she slips the latest issue of El Migrante, a six-page news bulletin for migrants and refugees, under tent flaps and makeshift bedroom doors fashioned out of heavy blankets.

The monthly paper carries news migrants can use to keep themselves safe on their dangerous journeys, such as contacts for safe places to sleep, legal aid organizations, and soup kitchens, as well as profiles of relevant nongovernmental organizations and fellow migrants.

“Information is protection,” says Monica Vázquez, an official in Mexico with UNHCR, the United Nations refugee agency.

El Migrante has been put together for the past three years by local journalist Ms. Castillo and her colleagues at the international nonprofit Internews. It is one of several initiatives – online and on paper – that have emerged in recent years to equip vulnerable migrants heading for the United States with oftentimes lifesaving information about their rights, where they can seek support, and what is new with ever-shifting border policies.

International law gives migrants the right to seek asylum outside their home country, and Mexican law provides them with some support measures, but most need help learning how to exercise these rights.

From TikTok legal aid video explainers to migration-specific Facebook pages and moderated WhatsApp groups, more and more organizations are stepping up to try and help bridge the information gaps that exist among governments, border patrols, human traffickers, and migrants.

News they can use

The air is stagnant in a small back room of the shelter. Six bunk beds cover every inch of wall space; the only decoration, a metallic-blue balloon shaped like the number three, droops sadly toward the center of the room.

Ms. Castillo introduces herself and asks the group living here, mostly women, if they have heard about El Migrante. She gets a mixed response.

“If you want the most up-to-date news, you can join our WhatsApp group,” she tells them. That is where the Internews team will answer migrants’ questions and direct them toward trustworthy resources in real time. But not toward traffickers – if anybody posts about crossing the U.S. border illegally, they’re expelled from the group.

“It’s dangerous and I fear for them,” says Jesse Hardman, Ms. Castillo’s U.S.-based colleague. “We can’t stop it, but they won’t learn how to do it in our group. Our goal is for people to be relying on safe channels of information.”

One woman reaches out for a paper and flips to an article called “What’s new with Title 42?” The Trump-era rule went into effect with the arrival of COVID-19 and has shuttered the border for the past two years, keeping everyone in this room in a holding pattern.

“The border’s opening up again at the end of May,” says one man.

“Someone told me that’s actually not happening,” says a woman sitting on a bottom bunk, nursing a baby.

People start to talk over one another and Ms. Castillo jumps in to explain that Title 42 was meant to have been overturned by May 23, but a judge temporarily blocked the move. “We’re basically in the same situation as the past several months,” she tells them.

That news seems to suck what little air there is out of the room. The group scatters, as residents turn to cellphones, child care, and new reading material in El Migrante.

Not all migrants have easy access to up-to-date information. Some can’t read easily, lack internet connectivity or a cellphone, or they fled home in such a hurry they had no time to prepare plans for their journeys. The information that is out there can be overwhelming and contradictory, “and unfortunately half of it is false,” says Ms. Vázquez of the UNHCR. “The rumors out there are tremendous.”

That’s what makes trustworthy sources of information invaluable. “The probability of risks goes down when migrants have access to credible information,” says Rodolfo Cruz Piñeiro, director of the population studies department at the College of the Northern Border, outside Tijuana, who has studied how migrants get their information. “You can make better, safer decisions.”

Print news may be dying elsewhere, but it’s alive and well for the thousands of migrants and refugees at shelters across Mexico each month who read El Migrante.

Navigating the labyrinth

The idea for the paper was born in the fall of 2018, when thousands of mostly Central American migrants traversed Mexico and arrived in Tijuana as part of the so-called migrant caravan. Mr. Hardman, who was working in California for Internews, got in touch with Ms. Castillo, a local reporter at the time, and they teamed up to survey some 200 newly arrived migrants about how they informed themselves and what sorts of questions they had about seeking asylum in Mexico and the U.S., or their rights as migrants.

“One response really stuck with me. Someone wrote, ‘I want to know how to navigate this labyrinth,’” Ms. Castillo says. “That’s exactly what they’re facing: chaos and confusion with no road map.”

The project took off, and a four-person team now reports and delivers 3,000 copies of the print paper once a month to roughly 50 shelters across Mexico, mostly on the southern and northern borders.

They produce a biweekly radio program that runs on a network of Mexican public radio stations, and moderate a WhatsApp group where Haitians, Hondurans, Cubans, Guatemalans, and others – dispersed across Mexico – can find daily news updates and ask more specific questions about anything from the paperwork required to enter a public health clinic to where to get diapers.

Marta Valenzuela, the education coordinator at an NGO supporting migrant families in Tijuana, says El Migrante may be old school with its print format and uncomplicated layout, but it’s exactly what some migrants need.

“It’s easier for them to take something physical,” she says of the people who pass through her office. “They have so much information thrown at them when they arrive. It’s helpful to have something concrete to come back to,” she says.

Stay informed, stay safe

Not that El Migrante has supplanted the smartphone. Ms. Vázquez runs a page called Confia en el Jaguar, or “Trust in the Jaguar” on Facebook, she says, because that’s where migrants naturally go to communicate with friends and relatives. “Why not put the information they need in the same place? Make it easy and accessible for them,” she says.

Confia en el Jaguar has become a central digital location where international organizations and local NGOs can share messages with the migrant and refugee communities, and where Ms. Vázquez’s team works in coordination with various U.N. agencies to answer questions in real time.

The proliferation in recent years of migrants traveling with smartphones has upped the project’s visibility. People from 36 countries consulted the page in the first four months of this year, and her staff engaged in direct message conversations with some 12,500 migrants and refugees in five languages last year.

She sees efforts like El Migrante and Confia en el Jaguar as working hand in hand, reinforcing trustworthy information “in physical spaces and online. We have to cover all the bases.”

Another online initiative has sprung from a legal aid organization with offices on both sides of the border, Al Otro Lado, or “On the Other Side.” It recently launched an account on TikTok, an app more commonly associated with viral dances and goofy lip-syncs than dissecting the complexity of U.S. border policy.

Migration and border policies are complicated and confusing, which makes it easier for criminals to dupe migrants, says Maddie Harrison, the community education coordinator at Al Otro Lado.

“Fake news and misinformation have grown since the pandemic,” she says. “You also see scams – people posing as immigration officials trying to charge people to cross the border or posing as immigration attorneys.

“We try to summarize what big policy changes actually mean for people at the border or thinking about traveling to the border,” Ms. Harrison says. Their most-watched video had 50,000 unique views, and she can see that it was played in countries around the world.

“People thinking about traveling to the border were able to access that information, hopefully making informed decisions” that helped them stay safe, she says.

“If our goal is to help people make informed decisions,” Mr. Hardman says, “the sooner we reach folks, the better.”

Points of Progress

Beach and river cleanups: Strange finds, and fish fertilizer for sale

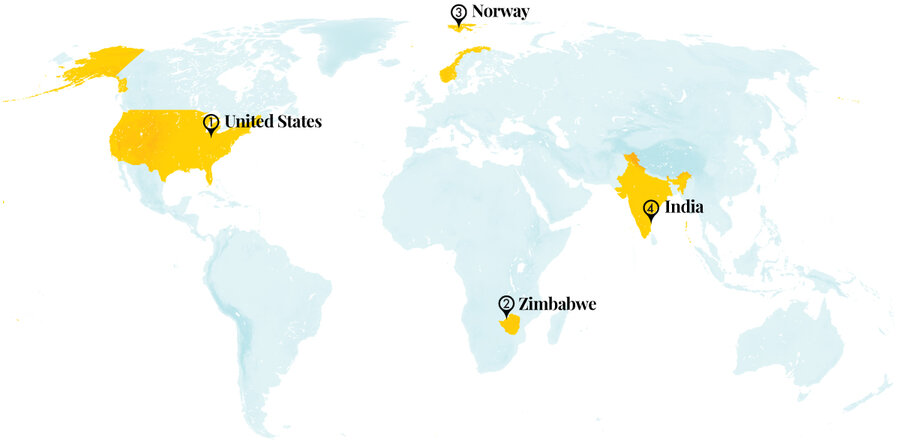

In this week’s Points of Progress, we look at innovative efforts to clean up water sources in Ohio and India. We also see female rangers protecting elephants in Zimbabwe and care for Norway’s endangered walruses.

Beach and river cleanups: Strange finds, and fish fertilizer for sale

Along with cleanup, prevention is another of our themes today. The United Nations has pledged to develop early disaster warning systems for everyone in the world. And in Zimbabwe, women are protecting wildlife and benefiting from jobs in a trained anti-poaching force.

1. United States

More than 355,950 pounds of trash were removed from the Ohio River last year. The debris – which includes everything from messages in bottles to a Civil War-era mortar shell – was collected by the nonprofit Living Lands & Waters, whose small paid crew lives and works aboard its four trash-collecting barges for up to nine months at a time. One barge carries its excavator, which multiplies the effort of volunteers who collected more than a half-million pounds of waste from the Ohio, Mississippi, Tennessee, Rock, Illinois, Des Plaines, and Cuyahoga rivers in 2021. As they move downriver, they organize cleanup and tree-planting events, as well as educational sessions, for volunteers who join them on land, on the barge, or in johnboats.

“No matter who you are, where you’re from, how old, young or what political party you belong to – it doesn’t matter, because no one likes seeing garbage in the river,” said Chad Pregracke, the nonprofit’s founder. “Especially if you know your city or town’s drinking water comes from there.”

The Groundtruth Project

2. Zimbabwe

An all-woman ranger unit is fighting poaching in Zimbabwe. Akashinga – the “brave ones” in the Shona language – has grown into a 200-strong force patrolling eight reserves in Zimbabwe’s rural areas, where women can struggle to make a living.

The group is armed, raising the criticism that a militarized approach fails to fix the root causes of poaching, such as poverty. At the same time, the Akashinga unit says it focuses on reducing poaching through community engagement and teaching about the economic benefits of conservation.

Having an all-woman team “generally de-escalates tension,” said founder Damien Mander. His International Anti-Poaching Foundation said the female rangers have arrested more than 300 poachers without firing a shot, while helping drive an 80% decrease in elephant poaching in the area where they operate. A consultancy’s research that focused on three all-woman ranger units – the Black Mambas of South Africa, Team Lioness in Kenya, and Akashinga – found no instances of corruption among the ranks, suggesting broader inclusion of women in anti-poaching efforts might help tamp down corruption in the sector.

“The opportunity of becoming a ranger came when I needed it the most,” said Margaret Darawanda, a single mother who is now eyeing going to college with the money she’s earned. “I am now able to look after my mother, my child, and my community.”

Thomson Reuters Foundation, International Anti-Poaching foundation

3. Norway

Walruses have returned to Norway in substantial numbers. Atlantic walruses in the archipelago of Svalbard, a major habitat, were nearly driven out of existence after 300 years of commercial hunting. Amid the massive population decline, the Norwegian government instituted a ban on walrus hunting in 1952.

In 2006, there were 2,629 of the long-toothed mammals in Svalbard. By 2018, the last time a population count was conducted, that number had jumped to 5,503, a lesson in the way nature can heal itself if humans give it space. It’s now common to see herds sunning on the banks of the archipelago. With about 230,000 walruses around the world, the species is considered vulnerable by conservationists. The British Antarctic Survey and the World Wildlife Fund are engaging citizen scientists in their Walrus From Space program to help read satellite photos, count the animals, and learn more about how they are being affected by climate change.

Smithsonian Magazine, British Antarctic Survey

4. India

Discarded parts from butchered and cleaned fish are being turned into fertilizer – supplementing incomes and cleaning up beaches. Coastal residents have been stuck with increasing amounts of fish waste dumped at the shore after the fish are prepared for sale. But a training and equipment program from India’s Central Institute of Brackishwater Aquaculture is an example of the circular economy brought to people whose livelihood depends on the sea, says Debasis De at CIBA.

Scientists trained fishers in Chennai to create two products: PlanktonPlus, for supporting healthy plankton in aquaculture projects, and HortiPlus, an organic manure. The products are made with simple machines and a patented enzyme and sold to farmers. “Fish waste is of major concern in a densely populated country like India,” said Dr. De, a team leader for CIBA’s Waste to Wealth program. “It renders the coast unhygienic and uninhabitable for fisher communities.” While CIBA sells the equipment needed to process the fish waste, it also gives some away to those eligible for financial help.

Hakai Magazine

World

The United Nations committed to providing early warning services to every person on Earth within five years. The U.N.’s World Meteorological Organization aims to scale up systems especially for the one-third of the world’s population that lacks coverage, often small island countries that are more prone to climate change-linked disasters. In Africa, 60% of the population lacks coverage that warns about floods, droughts, heat waves, or storms.

Beyond flashing alerts or texts on cellphones, the U.N. is looking for a variety of ways to alert people, especially in areas of low phone ownership – from radio broadcasts to designating people in remote villages to make announcements on megaphones. The World Meteorological Organization expects to present a $1.5 billion action plan at the COP 27 climate change summit in Egypt in November.

“Early warning systems save lives,” said U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres via video message. “Let us ensure they are working for everyone.”

Euronews

Essay

Fly-fishing, silence, and common ground: A stepfather’s gift

What does it take for a parent to connect with a rebellious child? In this personal essay, a son remembers how his stepdad built a bond with a fly rod and a noisy river.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Patrick Mooney Contributor

I was 12, and my newly acquired stepfather and I fought over everything. We even fought over math. But still he reached out to try to teach me something he loved.

So one weekend we drove four hours to the Little Truckee River. We marched down a ridge to the river. As the sound of traffic faded, the gurgling of the water rose. I feared that what lay ahead was an interminable conversation about responsibility and expectations. But instead, my stepfather turned aside, walked upstream, and began to cast.

I went my own way – fishing just like he had shown me countless times before. Soon I wasn’t thinking about my usual concerns: girls, school, sports, defying my parents, and girls. I was wading into dark waters to cast – wearing no waders.

My stepfather finally caught up to me. As we walked back to the truck, a conversation germinated that lasted most of the way home. Not a word was said about my attitude, my grades, or his skill as a father. We’d left all that at the Little Truckee.

We still bickered for years after that. But we’d found common ground. And now I see what my stepfather did and what he taught me. And I love him for it.

Fly-fishing, silence, and common ground: A stepfather’s gift

The concrete practice casting ponds of Oakland, California, were truly lacking. Nonetheless, my stepfather was determined to teach me his art. Back, forth, 1 o’clock, 10 o’clock, ticktock, like a poem with iambic meter. I cast, and I cast, and I cast until I could drop that fly into the little floating target ring at almost any given distance, like a stray leaf lightly fluttering to earth. But to what purpose?

I didn’t understand why this repetitive swaying of the rod sent my stepfather to the remotest reaches of fishing country for days on end. But I was to learn.

It’s not uncommon for a 12-year-old to clash with his newly acquired stepfather, and so it was with me and mine. We fought over homework and privileges; we even fought over math. But despite all of this, he still reached out to me to try to teach me something his father had taught him, something he had grown to love.

So one weekend we made the four-hour drive to the Sierra from Oakland, to the Little Truckee River, just upstream of Stampede Reservoir and downstream of state Route 89. Not much made an impression on me when I was 12, but I do recall the spectacular view of Stampede Reservoir from the ridge above the river – the mountains reflected in the midnight-blue water; the Little Truckee meandering into the lake creating a muddy delta at its mouth, and the massive expanse of evergreens and granite that surrounded the lake.

We marched from the dirt road down the side of the ridge to the river. As the sound of traffic drifted away, I became aware of the gurgling waters. I feared that what lay ahead was a long walk and an eternal conversation about responsibility and expectations. But when we reached the river I was surprised when my stepfather turned aside, walked upstream, and began to cast, searching the holes, pools, eddies, and undercut banks for fish.

The noise from the river precluded any conversation, and he was making it clear that we weren’t here to talk anyway.

I went my own way downstream, clambered over some rocks, got my feet soaked walking the shoreline, and discovered that to cast into certain areas I had to wade out into dark, unknown water without waders. I would, from time to time, sit down in the sun, enjoy a snack, and just take it all in.

I wasn’t at all aware that I wasn’t thinking about the things that usually concerned me: girls, school, sports, defying my parents, and girls. I wasn’t really aware that I hadn’t caught any fish, nor that I’d wandered far from my stepfather. I was pretty much alone. I had severed ties with all of my concerns. I didn’t have to be listening to loud music, I didn’t have to be listening to my parents – I didn’t have to be listening to anyone.

My stepfather finally caught up to me. He had been far more successful than I – it wasn’t the stream’s fault I hadn’t caught anything, it seems. I had much to learn.

As we walked back to the truck, the noise of the river faded. As it did, a conversation germinated between my stepfather and me that lasted most of the way back to Oakland. Not a word was said about my attitude, my grades, or his skill as a father. We’d left all that at the Little Truckee. Even when a tie rod on the truck broke, and we had to walk three miles down a dirt road in the dark to get to the highway, we continued to talk.

It would be too sweet to say that fly-fishing saved my relationship with my stepfather. Back home, we fell into our old ruts. But we had made contact. Or, rather, he had made contact with me. We had found common ground, and we could strive to find our way back to it.

We continued to bicker and argue well into my early 20s; but now, as I raise my own boys, I see what my stepfather did, what he taught me, and I love him for it.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Solutions that start with ‘I’m sorry’

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

If the recent mass shootings in the United States result in meaningful reforms, one reason may be a rather rare but important moment of contrition. After the shooting in Uvalde, Texas, Steven McCraw, director of the Texas Department of Public Safety, admitted that the hesitation by police to confront the gunman “was the wrong decision, period.”

Then he added: “If I thought it would help, I’d apologize.”

Such an admission by public officials is a door opener to reform. And Mr. McCraw isn’t the only prominent figure expressing remorse these days. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen told CNN on May 31, “I was wrong about the path inflation would take.”

At a time when public leaders seem more apt to evade and deflect when things go wrong, it is worth noting when someone takes responsibility. Meekness can shift a stalled debate from recrimination to joint problem-solving.

In Texas, Mr. McCraw’s comments, as much as they might evoke forgiveness, may do more than he imagined. They could move a shaken nation toward a shared inquiry of reforms that curb gun violence.

Solutions that start with ‘I’m sorry’

If the recent mass shootings in the United States result in meaningful reforms, one reason may be a rather rare but important moment of contrition. After the shooting in Uvalde, Texas, Steven McCraw, director of the Texas Department of Public Safety, admitted that the hesitation by police to confront the gunman “was the wrong decision, period.”

Then he added: “If I thought it would help, I’d apologize.”

Such an admission by public officials is a door opener to reform. And Mr. McCraw isn’t the only prominent figure expressing remorse these days. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen told CNN on May 31, “I was wrong about the path inflation would take.” Her mea culpa was matched by a comment in March by Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell: “Hindsight says we should have moved [against inflation] earlier.”

At a time when public leaders seem more apt to evade and deflect when things go wrong, it is worth noting when someone takes responsibility. Meekness can shift a stalled debate from recrimination to joint problem-solving.

“We live in a culture of inquisition rather than inquiry, more concerned with identifying a person with an action [of wrongdoing] than curiosity about what’s gone wrong or why,” British psychoanalyst Stephen Blumenthal told The Guardian. Genuine contrition, he said, “emanates from a place of wanting to validate and care for the other person, not shame them.”

Official apologies often involve complex calculations and can have questionable effects. In focus groups on hypothetical public apologies following controversial comments on controversial issues, for example, Harvard Law Professor Cass Sunstein found that the apologies backfired among voters. “In a diverse set of contexts,” he wrote in The New York Times, “an apology tended to decrease rather than to increase overall support for those who said or did things that many people consider offensive.”

Even so, he noted, apologies “might be a way of showing respect to those who have been offended or hurt, and of recognizing their fundamental dignity.”

That matters in bridging political divides as much as in healing individual sorrow. Admitting that it misread the threat of inflation may not help the Biden administration win over voters in November. But the optics of empathy have value.

In Texas, the genuineness of Mr. McCraw’s contrition will be tested in the days and months ahead as the department considers its response to the shooting. But humility could move a shaken nation toward a shared inquiry of reforms that curb gun violence.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

‘All tears will be wiped away’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Caryl Emra Farkas

In every hour, the light of God is here to deepen our understanding of love and life, which lifts grief and restores joy.

‘All tears will be wiped away’

A few minutes after hearing a voicemail saying that my father had passed on, I got a call from someone who wasn’t in the habit of calling out of the blue. I was so grateful that he rang me. I answered through tears because I was so overwhelmed with my sense of loss.

He assured me that however awful things felt, divine comfort was at hand. One way he expressed this was by telling me that I would keep knowing my dad. While I couldn’t know him as the familiar presence I was used to having in my life, I would come to know him spiritually.

At the time, I couldn’t imagine how that would work. But I knew that earnest prayer would reveal more to me.

Over those first few days I couldn’t believe the loss and was angry about how it had come about. I thought of how I’d do anything to change the way things had gone, feeling sad and sorry for myself and for my young daughter who, though just a toddler, had a strong relationship with her grandfather. I found myself saying that death meant we wouldn’t be seeing “Da” the way we were accustomed to, but that we would find him in new ways.

As time went on, I began connecting with a larger sense of life that includes all of us. Mary Baker Eddy writes in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “To be ‘present with the Lord’ is to have, not mere emotional ecstasy or faith, but the actual demonstration and understanding of Life as revealed in Christian Science” (p. 14).

In those moments of feeling God’s presence, of feeling the vastness of divine Love, the unstoppability of Life, and the actuality of Spirit wherever time and space appear to be, the stages of grief seemed to evaporate like a mist when the sun shines through. Sometimes these moments would come as a result of study – reading Scripture, where the theme of Spirit’s, God’s, omnipotence is so consistently repeated. And sometimes it would just come as a quiet realization that whispered, “Life is real and can never be lost.”

I began to see that the sorrow, the anger, and the feeling of loss were not as conclusive as they’d originally seemed. They were the reactions of mortal mind – a kind of thought that starts and ends with material conditions and leaves God out of its calculations. But cracks in this material sense of my father and our relationship began to appear – and the light of spiritual sense poured in.

St. John, describing the spiritual vision he had on the island of Patmos revealing “a new heaven and a new earth,” wrote, “God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away” (Revelation 21:1, 4).

In relation to John’s vision, Mrs. Eddy notes: “Take heart, dear sufferer, for this reality of being will surely appear sometime and in some way. There will be no more pain, and all tears will be wiped away. When you read this, remember Jesus’ words, ‘The kingdom of God is within you.’ This spiritual consciousness is therefore a present possibility” (Science and Health, pp. 573-574).

During the next year, each time my daughter recognized some beloved quality of her grandfather in someone, she would turn to me and say, “There’s Da!” Late that summer at a family reunion, she sat down with a cousin we’d never met before, who was about my father’s age. When I came by, I heard him singing World War II-era Canadian army songs to her – the same tunes my father had sung over her cradle to help her sleep. It provided strong confirmation that not even those sweet human gifts associated with her grandfather could be lost.

When some form of grieving would creep in, a thought of loss or disappointment with life, I learned to turn my thought back to the reality of God’s care and to trust in its completeness. In that peaceful sense of Life’s wholeness and eternality, I became more and more aware of those qualities I associated with my father continuing and expanding in their meaning for me. The pull to agree with the necessity of ongoing sorrow lessened, until it disappeared.

God really is with us, no matter what, and this comes to light as the omnipresent inspiration that life is so much more than meets the eye, that good is infinite and truly authoritative, and that relying on spiritual sense brings to light more truth, more goodness, more of the infinite ever-presence of Love.

Adapted from an article published on sentinel.christianscience.com, May 26, 2022.

A message of love

Peek-a-boo

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a story about the ownership transfer of the flagship store of Hudson’s Bay Company (a 352-year-old fur trading enterprise) to Canada’s First Nations.