- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- ‘Really out of control.’ America digs in for inflation fight.

- Did Pence save America? Jan. 6 panel spotlights VP’s role.

- From masked protests to the ballot box: Colombians shake up elections

- ‘Where is my place?’ Women push back against French politics’ machismo.

- Easing daily life for families, from Morocco to Vietnam

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How Mike Pence braved the ‘lions’ den’ on Jan. 6

Mike Pence has long described himself as “a Christian, a conservative, and a Republican – in that order.”

Though the former vice president did not testify at Thursday’s hearing of the Jan. 6 committee, his evangelical grounding – including a strong sense of morality – came through clearly via the words of close aides.

It was that faith-filled determination to follow his highest perception of right, despite intense pressure from President Donald Trump to try to undo the results of the 2020 election, that sustained Vice President Pence on Jan. 6, 2021.

Rioters at the Capitol chanted “Hang Mike Pence!” and at one point were essentially just around the corner from the vice president and members of his family and staff. Yet he refused to leave the Capitol until the election results were finalized.

What gave Mr. Pence the courage to stand fast? Prayer.

The day began, surrounded by aides, with a prayer for God’s guidance. And after Mr. Pence and Co. were whisked to safety in the bowels of the Capitol, his chief counsel pulled out his Bible and turned to the story of Daniel in the lions’ den.

“In Daniel 6,” Greg Jacob told the committee, “Daniel has become the second in command of Babylon, a pagan nation that he completely, faithfully serves. He refuses an order from the king that he cannot follow, and he does his duty – consistent with his oath to God.”

After the drama had subsided, chief of staff Marc Short said via video, he texted his boss a passage from 2 Timothy: “I fought the good fight, I finished the race, I have kept the faith.”

Ironically, Mr. Pence’s religious profile was a key reason Mr. Trump chose him as his running mate, to reassure the GOP’s evangelical base. In the end, it proved a bulwark against a presidential request that might have plunged the country into chaos. For more on Thursday’s hearing, see the article in today’s Monitor Daily by Christa Case Bryant.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

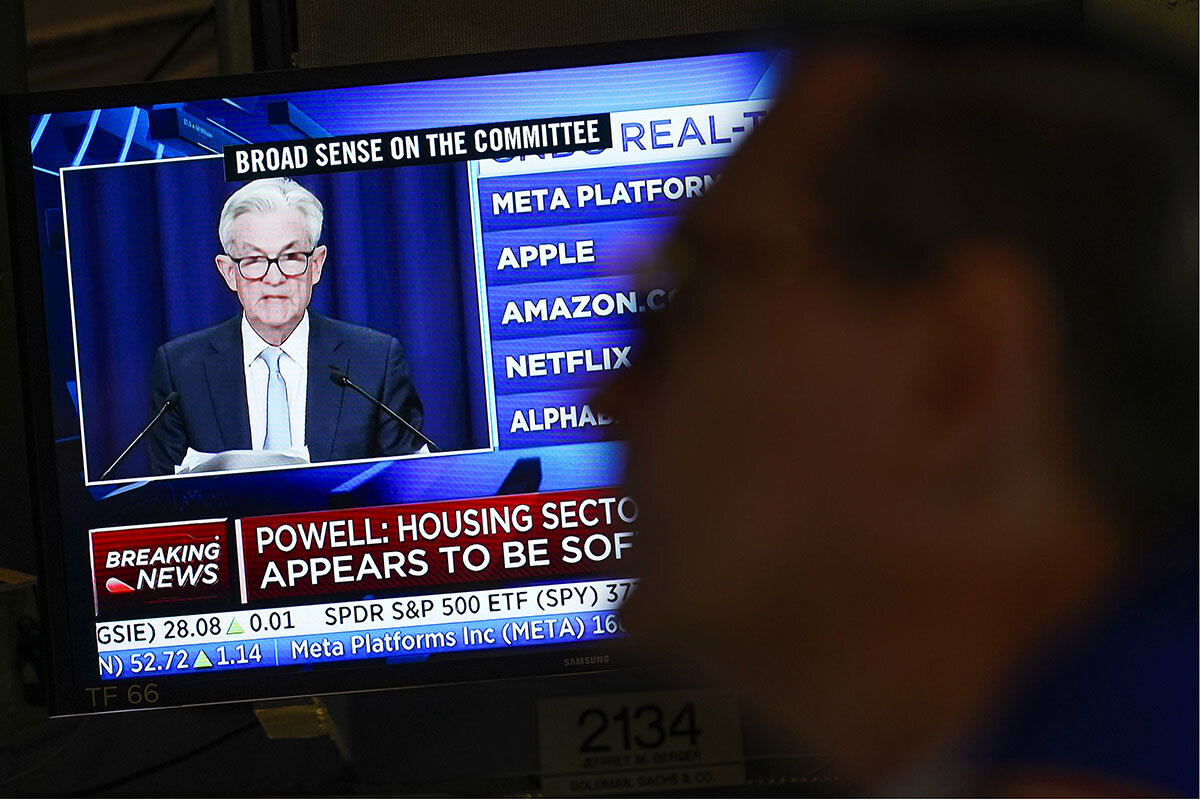

‘Really out of control.’ America digs in for inflation fight.

Inflation is sometimes described as too many people chasing too few goods. That’s the price-hike world Americans are struggling to cope with – and a key question is how persistent the problem will be.

Two days ago, Rebecca Dodson canceled her subscriptions to Netflix, Amazon Prime, and WeightWatchers. It’s the kind of belt-tightening that many Americans are facing amid the highest inflation in 40 years.

“I’m still in sticker shock when I fill my gas tank,” says the Portland, Oregon, retiree and online tai chi instructor.

For others, the challenge is food, trying to buy a house, or keeping a business afloat.

Some recent polls show inflation as people’s top concern, and the Fed is showing urgency of its own, with interest rate hikes designed to temper the consumer demand that has contributed to rising prices.

If all goes well, the policy shift coupled with Americans’ own economic resilience will be enough to weather the storm and see it begin to diminish in the months ahead.

The challenge is the range of forces at work: pent-up demand, but also supply problems that span from shipping and semiconductors to the availability of workers and war-affected flows of energy.

Will it last months or much longer? If limited supply is the main driver, the adjustment will depend on how quickly companies can boost production. If demand is key, the adjustment could be quicker. For some consumers, it’s already underway.

‘Really out of control.’ America digs in for inflation fight.

Two days ago, Rebecca Dodson canceled her subscriptions to Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Weight Watchers. It’s the kind of belt-tightening that many Americans are beginning to contemplate in the wake of high inflation unseen for 40 years.

“The gas prices are really out of control,” says the Portland, Oregon, retiree and online tai chi instructor. “I’m still in sticker shock when I fill my gas tank.”

For Nancy Bisbee, the problem is housing. Crammed in a 700-square-foot one-bedroom apartment in the New York borough of Manhattan, she, her husband, and two young boys were eager to move to cheaper and larger quarters. In late 2020, they started looking in Connecticut, then New Jersey, and finally upstate New York. But offering $20,000 above asking price was getting the family nowhere, she says, because homes were getting snapped up at $50,000 above asking price.

So the homebuying plans are on hold, Ms. Bisbee says. “About three or four months ago, we just said we can’t afford this.” When she peeks at home prices these days, homes are selling at $100,000 above asking price. And the rise in mortgage rates has further dampened the family’s enthusiasm.

For Robert Johnson in Valparaiso, Indiana, the price shock is food (along with gasoline): “We noticed steaks were up to $15 a pound – New York strips. Last year about this time, you could get them on sale for $8 a pound,” he says.

Around the nation and indeed much of the world, resurgent inflation has proved more persistent than pretty much anyone had expected – most notably the Federal Reserve policymakers who a year ago labeled it a “transitory” issue.

Some recent polls show concern so high that it ranks as the top problem facing the nation, and the Fed is showing urgency of its own, with interest rate hikes designed to temper the consumer demand that has contributed to rising prices.

If all goes well, the policy shift coupled with Americans’ own economic resilience will be enough to weather the storm and see it begin to diminish in the months ahead. The challenge is that this round of inflation is unlike any other, so traditional assumptions about how inflation plays out may not apply.

“Outside of wartime history ... it’s just a very unusual circumstance” for the West, says James Stock, a Harvard economics professor and member of the Council of Economic Advisers during the Obama administration.

A garden-variety inflationary spurt might be fueled by a shortage of food or energy. But this time, these shortages have been preceded by a two-year procession of rolling shortages – everything from toilet paper and sanitizer to computer chips and lumber to baby formula and now tampons – brought on by a once-in-a-century pandemic. Economists call such huge and unanticipated shocks “black swans.”

One black swan, such as the 2009 collapse of the subprime mortgage market, can sometimes trigger a panic and a huge recession. The appearance of two black swans – the pandemic and then the unexpected Russian invasion of Ukraine – makes the current period almost impossible to predict.

For example: Will the current set of shocks last a few months, like the toilet paper shortage? Or will it last years, like semiconductors? That debate is raging right now as economists try to figure out whether the challenge is mostly a supply or a demand problem. The answer may well offer clues to how quickly inflation subsides.

“People felt much wealthier”

Inflation is the result of a mismatch between supply and demand: too many people chasing too few goods. The conventional wisdom is that the current round of price rises started because supply chains were hit hard by the pandemic. COVID-19 lockdowns temporarily closed factories and made it difficult for suppliers to catch up, especially if, say, a fire or other disaster caused further glitches. The other explanation is that the pandemic caused demand to go up. Stuck at home, workers who no longer spent money on commuting or eating out suddenly had money to spend on home offices. Unprecedented rounds of federal stimulus payments to households didn’t hurt, either.

“People felt much wealthier,” says Diego Comin, an economics professor at Dartmouth College. “We wanted to buy ovens and fridges and stuff at Home Depot to make our houses look better.”

This unprecedented shift away from spending on services toward spending on goods was the main driver of the resulting inflation, he argues, with supply constraints exaggerating the effect.

If limited supply is the main driver, the adjustment will depend on how quickly companies can boost production. This proved relatively quick for the makers of toilet paper and cleaning products. It’s taking much longer for computer chips because semiconductor plants require huge investments and long lead times.

If instead the main problem is demand, then the adjustment could be quicker. For some consumers, it’s already underway.

Riding an hour to lower-priced shops

“I just have to be more intentional about how I spend my money,” says Gabriel Costa in Ayer, Massachusetts, where he works part time in child care while attending community college. “Gas has been the most stark contrast. ... I live in an area where I have to drive relatively far for most of my needs. So that’s just kind of a consistent concern.”

Rather than buy food in her Boston neighborhood, Nayelly Rodríguez, a college student from the Dominican Republic, travels an hour by subway to her grandmother’s neighborhood, where the prices are cheaper. And “this is where I buy all the big [nongrocery] stuff, and then I bring it back here,” she says.

Nationally, some signs suggest that supply and demand are starting to come back into balance. Walmart and Target last month reported they now had too much inventory on hand (although key parts for manufacturers, such as car parts and computer chips, remain in short supply). Employment postings and other data suggest the labor market is hot but no longer red-hot.

None of this suggests the transition will be easy. Nearly 7 in 10 economists expect a recession within the next 18 months and nearly that many CEOs agree, at least for their region, according to surveys in the past few days. The stock market has fallen more than 20%, a bear market that often signals a coming downturn. More than half of Americans believe the United States is already in a recession, according to a poll by The Economist and YouGov published Monday.

Harder to do business

Entrepreneurs and small-business owners are already feeling the pinch.

“I’ve noticed spending more on grocery stores or especially restaurants, and so for me, the only way to accommodate that is to bump up my own rates,” says Max Goldner, a graduate student in Brooklyn, New York, who relies on freelance tutoring for income. He’s been tutoring kids in cello and Hebrew for years and never raised his rates. “Inflation is the thing that’s making me have to be a businessperson at the end of the day.”

Wholesalers have raised their prices so much that Agyeman Manu-Dapaah, owner of a West African restaurant in Florissant, Missouri, is struggling to keep his regular customers. “A pound of goat used to go for $4. Today it’s $9, and yet customers expect the same prices,” he says.

He tried reducing portion sizes but got negative online reviews from customers. “So we had to go back to the [original] portion sizes that they were used to and increase the prices,” he says. While that’s also riling customers, it’s the only way Mr. Manu-Dapaah says his House of Jollof can stay afloat.

An eye on expectations

Quickly tamping down the public’s inflationary expectations is key to ending the price spirals.

“The biggest risk is not from these temporary price increases, but from these temporary price increases becoming permanent, because of them being built into expectations and contracts,” says Mr. Stock of Harvard. “And that’s why the Fed’s quick aggressive reaction is so important.”

On Wednesday, the Federal Reserve hiked interest rates by three-quarters of a percentage point, affecting everything from savings accounts to mortgage rates. The last time it made a hike so big was 1994.

If Ms. Bisbee had any remaining hopes of snagging a home within driving distance of New York, the rise in mortgage rates quashed them.

“We’re frustrated,” she says. Graduating from college just after the Great Recession, she needed years to find a full-time job. Now, she and her generation are looking to buy a home just as their parents did, but the skyrocketing costs are forbidding. “I feel I have the worst timing,” she says.

It’s a feeling Mr. Johnson in Valparaiso knows well. He graduated at the end of back-to-back recessions in the early 1980s, and it took him six years to find year-round employment. He’d grab seasonal work and rake leaves. He even delivered flowers for his brother-in-law’s funeral home in exchange for gas. For food, he’d buy hot dogs and baked beans in bulk when they were on sale, eating the beans from the can at lunchtime and the hot dogs at night. Yet time and again, money and opportunities arrived just in time, and he eventually landed a well-paid job as an engineer at Amtrak.

“I would say to any young person, ‘Don’t get bogged down in what you’re seeing,’” he says. “If we had gotten bogged down in worrying and fretting, we would never have seen the blessings we saw.”

Three years ago, he and his wife retired. Chicken and vegetables long ago replaced hot dogs and beans at mealtime.

Monitor staff writers Chris Ajuoga, Luke Cregan, Aubrey Hawke, and Rhyan du Peloux contributed to this story.

Editors note: This story was revised to correct Mr. Johnson's first name and his relationship to the funeral director.

Did Pence save America? Jan. 6 panel spotlights VP’s role.

The Jan. 6 committee portrayed the republic as riding on the fidelity of individuals to the Constitution, whose checks and balances are being severely tested in an age of disinformation and rising political violence.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” the framers once wrote. Yet the Jan. 6 committee credits Vice President Mike Pence for demonstrating a strength of character far above what the authors of the Constitution were counting on.

On Thursday, the committee laid out how Mr. Pence resisted a weekslong pressure campaign by Donald Trump to overturn or delay the certification of Joe Biden as president. It contrasted Mr. Pence’s fidelity to the Constitution with what it portrayed as Mr. Trump’s flagrant disregard for it.

Though some conservatives criticize states’ sweeping election law changes that led to unprecedented mail-in voting in 2020, Mr. Trump based his calls to “Stop the Steal” on unfounded claims of outright fraud. When that failed in the nation’s courts, he brought on a lawyer who advanced a dubious claim that the Constitution authorized the vice president to disrupt Congress’ counting of the electoral votes.

Judge Michael Luttig, a top conservative legal scholar called to testify, described the Trump team’s legal arguments as “beguiling and frivolous.” He credited Mr. Pence with preventing the country from plunging into revolution but warned that the former president and his allies “are executing that blueprint for 2024.”

Did Pence save America? Jan. 6 panel spotlights VP’s role.

“If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” the framers once wrote. On Thursday, the Jan. 6 committee credited Mike Pence with demonstrating a strength of character far above what the authors of the Constitution were counting on when they designed a system of government they hoped would withstand the excesses of human ambition and a lust for power.

In its third hearing this month, the committee laid out how then-Vice President Pence resisted a weeks-long pressure campaign by Donald Trump to overturn or at least delay the certification of Joe Biden as president. The committee contrasted Mr. Pence’s fidelity to the Constitution with what they portrayed as Mr. Trump’s flagrant disregard for it.

They depicted Mr. Trump as using the Constitution at best as a fig leaf for his own wounded pride, personal ambition, and desire for revenge. Though some conservative scholars took issue with states’ rapid and sweeping changes to election laws that led to unprecedented mail-in voting in 2020, the then-president based his call to “Stop the Steal” on unfounded claims of outright fraud. When that failed in the nation’s courts, he brought on a lawyer who advanced a dubious claim that the Constitution authorized the vice president to disrupt Congress’s counting of the electoral votes – but resorted to insults rather than legal reasoning when Mr. Pence refused.

“The president latched on to a dangerous theory and would not let go because he was convinced it would keep him in office,” said committee member Pete Aguilar, a California Democrat who led Thursday’s hearing. “We witnessed firsthand what happened when the president of the United States weaponized this theory.”

As in the first two hearings, the committee on Thursday relied on Trump administration officials and other Republican witnesses to make its case, using video clips of committee depositions with Mr. Pence’s chief of staff, Trump legal advisers, and Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump.

Retired conservative Judge J. Michael Luttig, who testified in person, called the Trump team’s legal arguments “beguiling and frivolous,” saying they had “no basis in the Constitution or the laws of the U.S.”

None of the testimony or featured clips provided a defense of Mr. Trump or of the legal reasoning underpinning his strategy, spearheaded by scholar John Eastman, who pleaded the Fifth Amendment in his deposition with the committee.

The nine-member committee has been criticized on the right for excluding dissenting views. It includes just two Republicans, after House Speaker Nancy Pelosi refused to seat two GOP members who had voted against certifying some states’ electors, leading Republican Leader Kevin McCarthy to pull all five of his appointees. Mr. McCarthy, along with several other Republican lawmakers, has refused to cooperate with the committee despite being served with a subpoena.

Mr. Luttig warned that while Mr. Pence had prevented the country from plunging into “revolution” in January 2021, the former president and his allies “are executing that blueprint for 2024 in open and plain view of the American public.”

In 2019, Ohio State law professor Edward Foley warned of a potential constitutional crisis if Mr. Trump, in the wake of a close election, sought to manipulate the Jan. 6 congressional proceedings to try to get himself declared the rightful winner. That idea gained currency in Mr. Trump’s circles at least two months before the November 2020 elections, and by early December Mr. Trump began actively lobbying Vice President Pence.

Under the 12th Amendment, Mr. Pence was to preside over a joint session of Congress to count the electoral votes from each state. As dozens of Mr. Trump’s suits alleging election fraud and irregularities failed to gain traction in the nation’s courts, the president argued that Mr. Pence could and should disrupt the counting.

From the beginning, Mr. Pence’s instinct was that the Constitution did not grant him the authority to do what Mr. Trump and Mr. Eastman had laid out.

“The truth is, there’s almost no idea more un-American than the notion that any one person could choose the American president,” said Mr. Pence in a speech last summer, admitting that while it was disappointing to lose the election, more was at stake. “If we lose faith in the Constitution, we won’t just lose elections. We’ll lose our country.”

Much of the testimony in Thursday’s hearing centered around the Electoral Count Act of 1887, which Congress passed after it had to intervene in a disputed presidential election eight years earlier. The law was meant to avoid such chaos from happening again, but Mr. Luttig and others say the wording is ambiguous and could be exploited by someone less scrupulous than Mr. Pence.

Greg Jacob, the vice president’s chief counsel, who also testified in person on Thursday, described to the Jan. 6 committee how he and his team had reviewed every electoral vote count in America’s history, the 1876 disputed election, the legislative history of the Electoral Count Act, and every law review article written about its constitutionality. They also fended off two lawsuits filed against the vice president to compel him to “exercise imagined extraconstitutional authority” and essentially decide the election himself.

Two days before the joint session, Mr. Trump and Mr. Eastman met with Mr. Pence and his top aides and laid out a pair of scenarios to provide Mr. Trump a path to victory: Reject the electors of key swing states outright, or send them back to the state legislatures, buying Mr. Trump time to pressure legislators to put forward new slates of electors who would certify him as the rightful winner.

Mr. Eastman recommended the latter course of action. However, Mr. Jacob testified that Mr. Eastman, when pressed, admitted that if that scheme was brought before the Supreme Court, it likely would be thrown out 9-0.

White House lawyers also disagreed with Mr. Eastman’s legal analysis, according to multiple Trump and Pence insiders. Mr. Kushner told the committee that he took White House Counsel Pat Cipollone’s threats to resign as “whining.”

That night, Mr. Pence’s outside counsel called Mr. Luttig for help. The retired judge, a conservative heavyweight in legal circles whom George W. Bush had reportedly considered nominating for the Supreme Court, had recently opened a Twitter account. With the help of his son, he published a thread of tweets that provided Mr. Pence the legal framework to dissent from the Trump-Eastman line of reasoning.

On the morning of Jan. 6, Mr. Trump called Mr. Pence and made one final push to change his mind. In a video clip played by the committee, Ivanka Trump testified that the conversation became “heated,” adding that it was “a different tone” than she’d heard her father take with Mr. Pence before.

Several hours later, in his “Save America” rally speech, Mr. Trump called on Mr. Pence to “do the right thing.” “All Vice President Pence has to do is send it back to the states to re-certify, and we become president, and you are the happiest people in the world,” he said, urging his supporters to march on the Capitol to encourage lawmakers to support only the “lawfully slated” electors. “Now it is up to Congress to confront this egregious assault on our democracy.”

At the Capitol, rioters chanted “Hang Mike Pence,” and breached the Senate side of the building as the vice president was overseeing a challenge to Arizona’s electors. Secret Service whisked him out of the chamber to his nearby office, then hurried him down a stairway just around the corner from rioters. They took him to a loading dock and urged him to evacuate. Nearly all of his entourage got in vehicles to depart the complex.

“But he looked at that and said: ‘I don’t want the world seeing the vice president leaving the Capitol in a 15-car motorcade,’ ” his then-chief of staff Marc Short told CNN this week. “ ‘This is the hallmark of democracy. And we’re going to complete our work.’ ”

Around 8 p.m., Mr. Pence gaveled Congress back into session. Just before midnight, Mr. Eastman made one last plea to go through with their plan. Mr. Pence resisted to the last, and shortly before 4 a.m. Congress declared Joe Biden and Kamala Harris the winners of the 2020 election.

But the danger has not passed, cautioned Judge Luttig, who has urged Congress to reform the Electoral Count Act so that America’s democracy will rest squarely on the rule of law and never again be contingent on one elected official’s integrity.

“No American ought to turn away from January 6, 2021,” he said, “until all of America comes to grips with what befell our country that day, and we decide what we want for our democracy from this day forward.”

From masked protests to the ballot box: Colombians shake up elections

Colombians marched in massive antigovernment protests in 2021. Their unanswered demands for improved employment, health, and education opportunities are driving record voters to elect a new outsider president.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Christina Noriega Contributor

Last year, protests paralyzed Colombia, with blockades and mass demonstrations lasting more than two months. Initially sparked by a proposed tax reform, the protests quickly broadened to include frustration over income, housing, education, and health care inequalities.

Out of the protests came something unexpected: some of the highest voter participation in a presidential election in two decades. Colombia has long been ruled by an elite group of establishment politicians. But, this weekend, two candidates who are eschewing the status quo face off in what is expected to be a historically close runoff. Both candidates are seen as leaning left – even if one is far from a traditional leftist – to cater to protester demands. The first-round vote was a broad rejection of the status quo.

Jhon Hernández, in Cali, voted for the first time in a presidential election this year. He says it was his participation in the protests that made him realize the importance of his vote. Taking part in the decision-making that positively impacted his community during the protests was empowering. When protests ended with no real solutions, he decided the only option left was to vote. He went on to organize get-out-the-vote activities.

“What do we win by protesting if we’re not going to vote?” he says.

Demonstrations aren’t new in Colombia, but in the past, protesters typically “didn’t directly participate in elections,” says Victoria González, a professor at the Universidad Externado in Bogotá.

“Now they believe their only hope for transformation is participating [at] the ballot box.”

From masked protests to the ballot box: Colombians shake up elections

Before Jhon Hernández became a voter for the first time last month, he was a front-line protester clamoring for change. He joined tens of thousands of Colombians last year in demanding stronger social programs and an end to a proposed tax reform, as COVID-19 restrictions wreaked havoc on the nation’s poor people.

This year, Mr. Hernández ditched the ski mask that had identified him as a protester and instead organized a voter registration drive, convinced that the way forward is not through bigger protests, but smarter voting.

“Change depends on our vote,” says the community leader, who cast his ballot in a presidential election for the first time this year, despite being eligible for the past 15 years.

He’s not alone. More Colombians cast their ballots in last month’s first-round election than in any other vote in the past 20 years, spurred in large part by the historic street protests. Frustration with the government’s out-of-touch policy proposals, combined with a growing desire for change, has laid the groundwork for the major political shift underway in this weekend’s presidential runoff.

For decades, Colombia has been ruled by an elite group of establishment politicians. But, this weekend, two candidates who are eschewing the status quo face off in what is expected to be a historically close runoff. Both candidates are seen as leaning left – even if one is far from a traditional leftist – to cater to protester demands.

“The vast majority of Colombians are fed up with this exclusionary political and economic class that has been governing only in their [own] favor, with the excuse that the armed conflict precluded them from addressing anyone else’s concerns,” says Elizabeth Dickinson, a senior analyst with the International Crisis Group.

“Undoubtedly, this scenario is a defeat for the traditional parties. It shows fatigue with their way of doing politics and dissatisfaction with expectations going unmet,” says Daniela Garzón, a researcher at the Peace and Reconciliation Foundation, a think tank in Bogotá.

From national strike to presidential elections

Last year, protests brought Colombia to a halt, with blockades and mass demonstrations lasting more than two months. Initially sparked by a proposed tax reform, the protests quickly broadened to include frustration over income, housing, education, and healthcare inequalities.

Close to 40% of Colombians live in poverty, nearly 50% of the workforce is informally employed, and violence is surging as armed groups expand, despite the promises of a 2016 peace deal.

Police repressed the protesters violently, and conservative President Iván Duque addressed few of their grievances. These issues became top voter concerns.

In Cali, the epicenter of unrest, Mr. Hernández joined from day one, angry over the poor medical attention he received after injuring himself as a construction worker.

With a rock-slinging cohort of protesters, Mr. Hernández and his neighbors ousted police from their neighborhood, and held a six-block area for two months. They transformed a police station into a library, held art events and concerts, and hosted community assemblies to discuss solutions to the unrest.

The levels of participation seen in these protests were unprecedented, says Victoria González, a professor at the Universidad Externado in Bogotá. People supported protesters in any way they could: organizing soup kitchens, leading vigils and silent marches, teaching art classes, and hosting outdoor seminars on politics. Some Colombians, especially in working-class neighborhoods, were learning for the first time how Congress works.

This “contributed to creating a wider political conscience,” she says.

Mr. Hernández says he’d never voted in an election before because “nothing was going to change.” But participating in the protests and the decision-making that positively impacted his community was empowering. When protests ended with no real solutions, he decided the only option left was to vote.

“What do we win by protesting if we’re not going to vote?” he says.

Demonstrations aren’t new in Colombia, but in the past, protesters typically “didn’t directly participate in elections,” says Dr. González.

“Now they believe their only hope for transformation is participating [at] the ballot box.”

Bye-bye status quo?

This weekend’s runoff pits Gustavo Petro, a former guerrilla who, if victorious, would become Colombia’s first leftist president, against Rodolfo Hernández, a populist businessman pledging to end corruption.

Mr. Petro previously served as mayor of Bogotá, and has promised free higher education, welfare for poor people, a transition away from oil exports, and investment in the rural economy. He’s raised fears among some conservatives and the business community that as a leftist he would move Colombia in the direction of neighboring Venezuela.

Mr. Hernández, also a former mayor in the city of Bucaramanga, has inspired fed-up voters with his anti-corruption platform and straightforward manner of speaking. His populist rhetoric, asserting that “the thieves need to be kicked out of politics,” has connected with Colombians and earned him a surprise spot in the runoff.

Despite comparisons to Donald Trump and a wave of support from establishment candidates who didn’t make it into the second round, Mr. Hernández has released policy proposals that skew surprisingly to the left. They call for a full implementation of the peace deal, talks with the largest remaining rebel group, marijuana legalization, and restrictions on riot police. But he has also mentioned an intention to rule by emergency decree if he wins office, raising concern about his commitment to democratic institutions.

It’s not just Colombia rejecting the status quo. Across Latin America, lack of opportunity, and more recently the consequences of the pandemic, have fueled anti-incumbent fervor, catapulting outsiders into office. From Gabriel Boric in Chile to Andrés Manuel López Obrador in Mexico, successful candidates are increasingly speaking to and depending on votes of discontent.

But two anti-establishment outsiders reaching the final round makes Colombia unique, says Patricio Navia, a political scientist and professor at New York University. Both candidates are promising a clean break from the right-wing brand of politics that has won the presidency in the past four election cycles.

New generation of social leaders

On a recent afternoon in Cali, former protesters rode motorcycles to a rough neighborhood in the city’s south where they served food, offered free haircuts – and encouraged locals to vote.

Mayra Mueses, a protester-turned-organizer, says initially she had little interest in electoral politics. She’d never voted in her life. But, after five people were killed at the protest blockade she oversaw for two months last year, she felt driven to seek out new ways to pressure the government for change.

By talking to other protesters and educating herself, she “understood that the repression that came from the police had been ordered,” from people in power, says Ms. Mueses. “We began to ask ourselves, ‘In whose hands are we if [politicians] are giving orders to kill their own people?’”

At least 80 people died during the protests last year, according to the rights group Indepaz, and Ms. Mueses’ political awakening isn’t unique in areas where protesters took to the streets..

A recent poll shows nearly 70% of people between the ages of 18 and 24, the protagonists of last year’s demonstrations, will vote for Mr. Petro on June 19. They’re concerned with poverty and lack of opportunities, having witnessed friends join violent gangs and parents work until old age without pensions.

Older generations are wary of the stigmas associated with the left, in a nation that suffered decades of civil war between extreme leftist guerrilla groups and the government. Many are falling in line behind Mr. Hernández.

Ms. Mueses has no plans to return to protesting, deterred by the violence that injured and killed so many last year. But even if Mr. Petro loses, she says, that would not dampen her commitment to social change. “We understand that it is the responsibility of the youth, like us, to vote.”

Since the social uprisings last year, she adds, “many social leaders have been born.”

‘Where is my place?’ Women push back against French politics’ machismo.

French parties are required to submit gender-equal candidate lists in elections, but some don’t. So women in politics are seeking new ways to loosen the old boy network’s grip.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In the run-up to the second round of the French legislative elections Sunday, issues related to gender have become important factors in the race.

Though President Emmanuel Macron has been lauded for choosing a woman as interim prime minister, political parties have been scrutinized about whether they satisfy the country’s laws requiring gender parity in the candidate lists they put forward. Those who don’t risk losing precious public funding.

Among the list of 6,293 candidates this year, 44.2% are women and 55.8% are men. It is an improvement on 2012, which saw 40% women versus 60% men. Some large political parties are still willing to be sanctioned instead of respecting the parity law.

“Since the beginning, there has been opposition and incomprehension within the political class about a woman’s place, but this is completely at odds with how women are viewed in the rest of society,” says political scientist Janine Mossuz-Lavau. “No one has a problem with a woman doctor or a woman dentist. It really is specific to politics, which continues to have a very traditional view of society.”

‘Where is my place?’ Women push back against French politics’ machismo.

As a local politician in the French city of Rouen, Laura Slimani has been privy to degrading comments on the job on several occasions. Once after delivering a speech as a young Socialist, she was congratulated by a male politician who pinched her on the cheek.

Another time, when she came to work in a fitted skirt, a male colleague asked her why she was dressed like the boss’s secretary, conjuring up images of an oversexualized assistant.

“It’s pretty frequent to have these kinds of comments,” says Ms. Slimani, now the deputy mayor of Rouen and also in charge of fighting gender equality and discrimination. “Sometimes the men in question don’t even realize they’re being offensive.”

That was the case two weeks ago, when Ms. Slimani had a run-in with a right-wing politician during a city council meeting. After arguing over naming more schools after notable French women, the male politician told the mayor – also a man – to “put [Ms. Slimani] in her place.”

“‘Where is my place,’ I asked him. ‘Outside?’” says Ms. Slimani. “Later, I told the mayor why it was so offensive to have one man tell another man where my place was, as a woman, in a political setting.”

In the run-up to the second round of the French legislative elections on Sunday, issues related to gender have become important factors in the race. Though President Emmanuel Macron has been lauded for choosing a woman as interim prime minister, political parties have been scrutinized about whether they satisfy the country’s laws requiring gender parity in the candidate lists they put forward. As female politicians and activists shine the light on gender equality, sexism, and sexual misconduct in politics, it has left parties with no choice but to react – and act.

“Since the beginning, there has been opposition and incomprehension within the political class about a woman’s place, but this is completely at odds with how women are viewed in the rest of society,” says Janine Mossuz-Lavau, a political scientist at Sciences Po Paris and a specialist in gender and politics. “No one has a problem with a woman doctor or a woman dentist. It really is specific to politics, which continues to have a very traditional view of society.

“And when it comes to misconduct, there’s no place to hide now with social media and 24-hour news. Those who have made errors in judgment will pay the price.”

Sexism at the National Assembly

French women were given the right to vote in 1944, and one year later 33 women were elected to the National Assembly’s then-522 seats. Ever since, gender equality in parliament has ebbed and flowed.

Since June 2000, political parties are required by French law to respect gender parity within a margin of 2% at the legislative elections. Those who don’t risk losing precious public funding. Among the list of 6,293 candidates this year, 44.2% are women and 55.8% are men. It is an improvement on 2012, which saw 40% women versus 60% men.

While Mr. Macron’s En Marche and the far-right National Rally party both meet the parity requirements this year, some political parties are still willing to be sanctioned instead of respecting the parity law. The far-left La France Insoumise, led by Jean-Luc Mélenchon, will forfeit more than €250,000 ($261,000) while the right-wing Les Républicains gave up €1.8 million.

From 2012 to 2017, the parity law failed to make significant changes – to the disdain of Danielle Bousquet, the president of France’s High Council on gender equality. During that period, the Socialist and Républicain parties were fined €6.4 million and €18 million, respectively.

“Once again, the Républicains said they will be paying the fine this year,” says Julia Mouzan, founder of the multiparty, Bordeaux-based Elues Locales, France’s first network of female politicians. “Public funding is so important to smaller parties that they have to follow the parity law to survive. But unfortunately, it’s often the larger parties who are willing to pay the fine versus respecting the law.”

There have been glimmers of progress. Elisabeth Borne recently became the second woman in France to be named prime minister. Following Ms. Borne’s appointment in May, Edith Cresson – France’s first female prime minister from 1991 to 1992 – wished the new leader “lots of luck,” while heavily criticizing the French political class for its “machismo.”

Ms. Cresson was subjected to catcalls during a meeting of the National Assembly in 1992. Twenty years later, then-Housing Minister Cécile Duflot was whistled at during an Assembly meeting after arriving in a blue-flowered dress. According to a November 2021 study of 1,000 female politicians by Elues Locales, 74% said they had been victims of sexism in the workplace.

“Women will tell us that when they show up to a political meeting, a male politician will ask them to get them a coffee or make photocopies,” says Ms. Mouzan. “There is a wide range of incidents that go from comments to physical actions, even threats. But what we hear about is only a fraction of what really goes on behind closed doors.”

Pushing back on bad actors

Just as political parties and politicians have been called out for bad behavior on gender parity and sexism, there is a growing intolerance of acts of sexual misconduct by public officials.

Last November, 285 women – including politicians, businesswomen, and activists – signed an open letter published in Le Monde newspaper, calling for a stronger response against legislators facing such allegations. The #MeTooPolitique movement was born, and quickly gained traction thanks to similar social movements in France’s literary, cinema, and sports sectors.

In February, the five women – four politicians and one journalist – at the heart of #MeTooPolitique founded the Observatory for Sexist and Sexual Violence in Politics, a watchdog that publishes the names of male politicians accused of misconduct via their Twitter account.

“There is something very bourgeois about French politics, where talking about these things means talking about sex, which is still a taboo,” says Mathilde Viot, co-founder of the observatory. “But we’re trying to highlight the impunity mechanisms that take place in each affair, and the sense of solidarity between male politicians in which they protect one another, even across party lines.”

The observatory has been partly responsible for several public officials putting an end to their electoral bids due to mounting public pressure. Far-left assembly candidate Taha Bouhafs withdrew in mid-May after several women accused him of sexual assault.

And even after saying that his criminal record “shouldn’t stop [him] from political life,” Jérôme Peyrat, an En Marche candidate from the Dordogne, finally stepped out of the legislative race following controversy over his 2020 conviction of violence against his former partner.

Still, several public officials accused of misconduct remain in their political functions, including Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin, who has been accused of rape and sexual harassment. Damien Abad, the recently appointed minister of solidarity, has been accused of rape by two women. Recent polls show him comfortably ahead in his local Ain department.

Elues Locales has encouraged its network to speak out about their experiences to make sexism and sexual violence more visible. Even if progress sometimes feels like one step forward and one step back, experts say the spotlight is finally being put on gender issues in politics in a meaningful way, which has forced change.

“There are still archaic things about how female politicians are expected to be, but there is a huge difference between what was said and done even 10 years ago compared to today,” says Dr. Mossuz-Lavau of Sciences Po. “Obviously we need to reflect on what we can do to improve things, but we also need to be conscious of the past and see the evolution.”

Points of Progress

Easing daily life for families, from Morocco to Vietnam

Governments and large institutions have the power to make big changes for people that aren’t possible for individuals to achieve alone. In Morocco, increasing parental leave for fathers is recognition of the shared responsibility for children. And in Vietnam, a decade of assessment shows poverty reduction across society.

Easing daily life for families, from Morocco to Vietnam

While official policy can effect widespread change, the ideas of people acting alone can spread and inspire others – especially when given time to work, such as a 10-year effort that has resulted in the tagging of 800 sharks in the South Atlantic ocean.

1. Argentina

Sport fishers who used to kill sharks are now helping conserve them. In San Blas Bay – the heart of Argentina’s sport fishing – catching and killing a shark used to be a source of pride, despite declines in shark populations that include critically endangered species. Now, thanks to a project known as Conserving Sharks in Argentina, some 150 sport fishers are instead tagging sharks with identification devices and releasing them back into the ocean, providing researchers with useful information to help design conservation strategies.

The effort is proof that anyone can make a difference when it comes to conservation. Sport fisher David Dau was no biologist, but began the project 10 years ago after realizing the harm he and others were causing. He spread his message far and wide, writing magazine articles, giving talks at fishing clubs, and making TV appearances. The approach hasn’t caught on in neighboring countries, but Mr. Dau says he can tell change is taking place. “Today, the trophy is showing the video of the release instead of showing the shark hanging from a hook.”

Mongabay

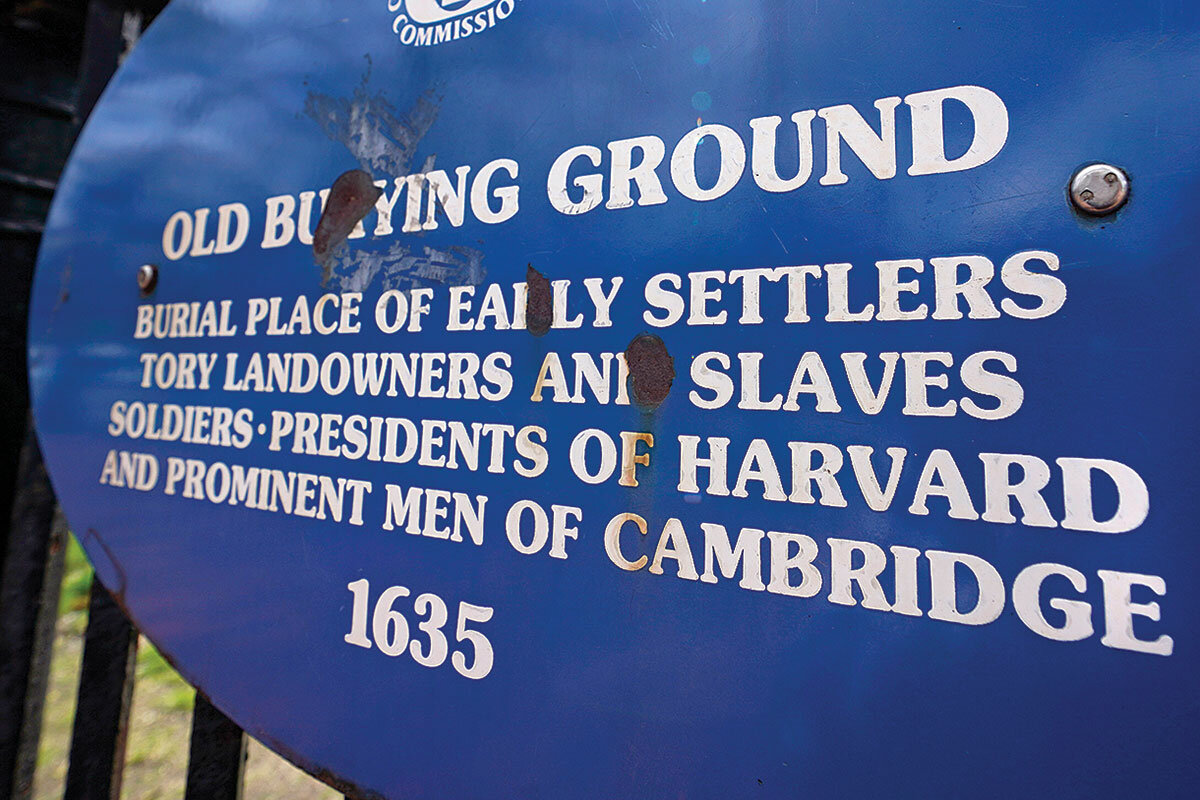

2. United States

Harvard University committed $100 million to address its historical complicity with slavery. The move follows an in-depth report of the ways slavery shaped and benefited the institution, from the enslaved people who worked on campus to the university wealth accrued directly or indirectly from the plantation industry. The resources will be used to implement the recommendations of the report, which include expanding educational opportunities for descendants of enslaved people and creating partnerships with historically Black colleges and universities.

Harvard is one of many institutions that has profited from the history of slavery. “While Harvard does not bear exclusive responsibility for these injustices, and while many members of our community have worked hard to counteract them, Harvard benefited from and in some ways perpetuated practices that were profoundly immoral,” said university President Lawrence Bacow.

CNN

3. Spain

Workday use of Barcelona’s metropolitan bike-lane network grew 49% between 2019 and 2021, according to a recent study. The Metropolitan Area of Barcelona, encompassing Barcelona and 36 nearby municipalities, launched the vast cyclable system known as Bicivía in 2016 to promote more sustainable and healthier transport, and has built more than 400 kilometers (about 250 miles) of paths so far. The study found that scooter use increased 123%, while bicycle use grew a more moderate but still significant 34%.

Growth was higher in less central regions and coastal areas than in the city of Barcelona, which has had its own network of bike lanes and promoted their use for longer. Nonetheless, the preliminary data is encouraging for city planners. “When the infrastructure is created, citizens are committed to changing their habits and making use of it,” said Antoni Poveda, the Metropolitan Area of Barcelona’s vice president of mobility, transport, and sustainability.

Intelligent Transport, 20 Minutos

4. Morocco

Morocco expanded paid paternity leave from three to 15 days for public workers. While the country’s labor laws grant mothers 14 weeks of maternity leave, fathers have often been left out of the conversation. In consultation with labor unions, the government is also improving conditions for working-class people with an increased national minimum wage and more financial support for families with more than three children.

While the paid leave only applies to workers in the public sector, advocates consider it the beginning of a more equitable parenting dynamic. For Ghita Mezzour, the minister delegate in charge of digital transition and administrative reform, the support is as much for mothers as it is for fathers: “The measure is in accordance with the constitution that stipulates that the education of children is a common and shared responsibility.”

Morocco World News

5. Vietnam

Vietnam’s poverty rate fell from 16.8% to 5% in the decade leading up to 2020, according to the World Bank’s 2022 Vietnam Poverty and Equity Assessment. That’s the equivalent of 10 million people pulled above the poverty line, thanks to rising wages and an increase in formal employment – especially in the manufacturing and services sectors. Foreign investment opened new, better-paying jobs, while international tourism expanded from 5 million to 18 million visitors. Overall, average household wages tripled.

While inequality increased slightly in the second half of the decade, and the pandemic has slowed poverty reduction, the past 10 years have set Vietnam on a promising path. To continue the trend in poverty reduction, the World Bank recommends investing in higher education, ensuring that social assistance programs reach the poorest households, and expanding the country’s tax base.

World Bank

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Free thinking in unfree Iran

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Since early May, ongoing protests in Iran have reached unprecedented levels, not only in number of places but types of demonstrators. Teachers, retirees, civil servants, rural poor people, even cellphone sellers in the bazaars have either gone on strike or taken to the streets – despite brutal repression by the regime of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

The protests were sparked by sudden cuts in food subsidies. Yet they are driven by an acute downturn in the economy. As the protests have gone on, they have turned political, marked by two common chants: “Clerics! Get lost.” and “We don’t want an Islamic republic.”

That message reflects a growing desire among more Iranians for equality as citizens and for secular rule. Increasingly, Iranians reject life under a theocracy trying to create an Islamic civilization across the Middle East.

The gap between the ruling mullahs and the people has never been wider.

Free thinking in unfree Iran

Since early May, ongoing protests in Iran have reached unprecedented levels, not only in number of places but types of demonstrators. Teachers, retirees, civil servants, rural poor people, even cell-phone sellers in the bazaars have either gone on strike or taken to the streets – despite brutal repression by the regime of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

The protests were sparked by sudden cuts in food subsidies. Yet they are driven by an acute downturn in the economy. Corruption, drought, and Western sanctions have all taken a toll. As the protests have gone on, they have turned political, marked by two common chants: “Clerics! Get lost.” and “We don’t want an Islamic republic.”

That message reflects a growing desire among more Iranians for equality as citizens and for secular rule. Increasingly, Iranians reject life under a theocracy trying to create an Islamic civilization across the Middle East. Another protest chant calls for an end to government spending on militant groups in Iraq, Lebanon, Yemen, Syria, and Gaza.

More than half of Iranians now live below the poverty line. According to a 2020 poll, 68% believe that religious prescriptions should be excluded from legislation. Only a third identify as Shiite Muslim while nearly half say they have transitioned from being religious to nonreligious. An estimated 150,000-180,000 educated Iranians leave the country every year.

The gap between the ruling mullahs and the people has never been wider. The same can be said about Iran’s influence over nearby Iraq and Lebanon. Recent elections in both countries reflect popular demands to end the use of religion in politics.

That same 2020 poll found more than half of parents want their children to learn about different religions. For a regime trying to impose its theology both at home and abroad, that sort of interest in equality is difficult to suppress. The protests may be quelled. A popular revolution in free thinking will go on.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Release

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

All are included in the divine promise of freedom from hate, fear, and limitation, as this poem conveys.

Release

Riding the heels of “There’s

no escaping this one” comes

a faint rosy wistfulness to be

free as a bird – to fly from

whatever screams that relief

is only to be found “out there,”

somewhere far off.

Even as fear or pain or what

seems unforgivable doggedly

insists that we are wingless, the question pours in effortlessly:

Can darkness bind light?

The answer brings sudden

uplift as we glimpse the

irresistible freedom that is

quickened in us by the light of God, Love itself; a present

light – never leadened by depravity,

cruelty, hate – experienced within,

unfurling as the sole reality.

All-powerful, brilliant truth of our

divine identity – born of Spirit, forever

Love’s child, woven in Life’s infinite

fabric – frees us to drink in the

spiritual fact that each of us is

deeply loved, cradled in safety,

tenderly cared for by God, no matter

how rough and dark the waters.

We watch the scene shift, blazing a

new shore in full view. Limits yield,

answers come, we take flight.

A message of love

Equine excursion

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us. Come again Tuesday, when we look at Title IX – considered one of the most significant pieces of gender legislation in the past 50 years.

Also, a reminder that the Monitor won’t publish on Monday, in recognition of the Juneteenth federal holiday. Watch for an email from contributor Maisie Sparks about using this day to look at both history and the future.