- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 15 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Title IX ushered many women into sports. Some are still sidelined.

I am a Title IX baby – born 10 months before the law passed on June 23, 1972. Title IX means different things to different people, but to me it means sports. In the 50 years since its passing, the federal law increased participation by women in collegiate sports by more than 600% – and as a varsity college soccer player and track sprinter, that included me.

But Title IX hasn’t benefited all women equally. Less than one-third of collegiate female athletes in the United States are women of color, according to the Women’s Sports Foundation.

Alpha Alexander knows something about that racial gap. When she arrived at the College of Wooster in Ohio in 1972, she had been a citywide tennis champion. At first, she turned away from sports to focus on her studies. “Our parents ... wanted to make sure that we would succeed in life,” she says. “So education was a high priority.”

But eventually she laced up her shoes, going on to play basketball, volleyball, lacrosse, and tennis. Having been the only Black athlete on her teams, she wrote her 1978 master’s thesis on women of color in collegiate sports.

Her studies led her to Temple University in Pennsylvania, where she worked in the athletic department with Professor Tina Sloan Green, the women’s lacrosse coach and the first African American to play for the women’s national field hockey team. They soon realized how few Black women worked in sports administration. “We didn’t see anybody that looked like us on that administrative level,” says Dr. Alexander.

So together with Olympic fencer Nikki Franke, and lawyer and former track athlete Linda Sheryl Greene, they co-founded the Black Women in Sport Foundation in 1992. As the group prepares to mark its 30th anniversary, Professor Sloan Green says lack of access, financial support, and cultural acceptance still holds back women of color in sports.

“My agenda right now is to make sure that young girls pre-K through eighth grade have access to a variety of sports,” says Professor Sloan Green. “I know it works. My daughter [Traci Green] would not be the head coach of Harvard tennis had she not been exposed to sports at an early age.”

As I share in today’s podcast, athletics made a big difference in my life. I’m grateful the Black Women in Sport Foundation is working to expand access to those opportunities.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

How 37 words changed the world for women

The effects of Title IX, considered one of the most significant pieces of gender legislation in the past 50 years, stretch beyond equity on the athletic field to touch almost every classroom and family in America.

-

Tara Adhikari Staff writer

Carol Hutchins was a self-described tomboy. She resisted makeup sessions with her two sisters to play sandlot baseball. Pretty soon, though, it became apparent that there was nowhere for girls to play organized sports in 1960s Lansing, Michigan.

“I felt like I was different in a bad way, like, there was something wrong with me,” Ms. Hutchins says.

Things changed with a sparsely worded law passed on June 23, 1972, that didn’t even have the word “sports” in it. Title IX simply made it illegal to discriminate on the basis of sex in educational settings that receive federal funding.

The law ushered in a gender revolution that still continues today, a half-century later. The number of girls and women who play organized sports has ballooned. The law has also helped propel more women to get college degrees, provided them some protection against sexual harassment and assault, and aided them in advancing to corner offices and boardrooms.

Like any revolution, Title IX has generated its share of controversy, from its application to sexual assault on college campuses to the debate around including transgender individuals in its protections. In some instances, men’s sports opportunities have declined to make room for women.

Yet the fight for women’s basic rights isn’t over. Many women believe the law hasn’t gone far enough in correcting inequities – on athletic fields, in classrooms, or in corporate suites.

“It’s still too early, in my view, to be congratulating ourselves,” says Marissa Pollick, a lawyer and lecturer at the University of Michigan and a Title IX consultant.

How 37 words changed the world for women

It’s a story Carol Hutchins likes to tell. She’s sharing it again now, sitting in her office at the University of Michigan, surrounded by awards that hint at her status as one of the most successful college coaches – male or female – in the United States. It’s about her click moment in 1976.

Ms. Hutchins was a freshman varsity basketball player at Michigan State University, living her dream of playing college sports at a time when few women were student-athletes. On that winter day, her team got a fortuitous break: Instead of practicing where they normally did, in the intramural building with its leaky roof and warped floor, the women were working out in Jenison Field House – the big gymnasium where the men’s basketball team played. They were getting ready for a rare double-header in which both the men’s and women’s teams were hosting major out-of-town rivals.

As the women ran plays, the visiting men’s team walked in with its famous coach – revered by anyone who followed college basketball. He called the women’s team over. Ms. Hutchins was excited. Surely, she thought, they were going to get a pep talk. Some strategic insights. A motivational anecdote. Not exactly.

“He said, ‘You need to get off the court because nobody gives a damn about women’s basketball,’” Ms. Hutchins recalls. Even today, nearly five decades later, the woman who has gone on to win more games as a college softball coach than anyone else in NCAA history winces at the memory. Her eyes flash anger. “He said it to our faces! I was lit. It definitely changed my world.”

She won’t name the basketball coach outright. She doesn’t need to. “This is the thing,” says Ms. Hutchins, who has coached at Michigan since 1983. “The reason I don’t name him is because it could be a lot of them. That was the era.”

It’s certainly not the era anymore. The reason a comment like that sounds so archaic now, and women like Ms. Hutchins have been given the opportunity to vault to the pinnacle of the college athletic world, is largely because of a sparsely worded law passed on June 23, 1972, that didn’t even have the word “sports” in it. Title IX simply made it illegal to discriminate on the basis of sex in educational settings that receive federal funding.

Yet the law ushered in a gender revolution – and has, by many accounts, become one of the most significant pieces of federal legislation to benefit women in the past 50 years.

Monitor Backstory: Voices of Title IX

Title IX is complicated. Reporting on the 50th anniversary of this 37-word law, the Monitor's Kendra Nordin Beato saw the many and varied ways it reshaped US society. In today's episode, she shares how women have pushed for equal treatment with courage and resilience, inspiring generation after generation. Hosted by Samantha Laine Perfas.

Today its ripple effects reach into almost every dugout and locker room in America, almost every living room, almost every classroom, and even corporate suites. It has changed the lives of countless individual women – and society itself.

The dramatic rise in the number of girls and women participating in sports is the most often cited impact. But the changes extend way beyond that. The law has helped propel more women to get college degrees, provided them some protection against sexual harassment and assault, and aided them in advancing to corner offices and boardrooms. Girls can take auto shop today, in part because of the cultural changes wrought by Title IX, and getting pregnant no longer means getting kicked out of school or losing a job.

Still, like any revolution, Title IX has generated its share of controversy. Some critics think its scope goes way too far, while many proponents of the law think it hasn’t gone far enough. Indeed, ask almost any women’s rights advocate or female coach who has traced the law’s arc of progress over the past 50 years, and they will say the work of Title IX is hardly complete.

“It’s still too early, in my view, to be congratulating ourselves,” says Marissa Pollick, a lawyer and lecturer in sports management at the University of Michigan and a Title IX consultant. “I think the law is widely misunderstood, and there’s still a lot of myths and misconceptions surrounding the law and its application.”

The use and interpretation of Title IX have, in fact, been inconsistent since its passing, tossed like a political football under changing administrations. In 1984, President Ronald Reagan tried and failed to limit the law’s application to specific programs. In 2005, President George W. Bush suggested colleges dole out federal money to men’s and women’s sports based on the level of interest in them.

In 2011, President Barack Obama pointedly reminded colleges of their obligations to combat sexual harassment under the law, while the administration of President Donald Trump narrowed the definition of sexual misconduct and required that both parties be present at investigative hearings and subject to cross-examination. The current administration is considering extending Title IX protections to transgender students.

As these whipsaws have occurred at the top levels of power, clashes have erupted on college campuses, too. Critics have long argued that requiring equal opportunities for women will diminish men’s opportunities. In some ways, they have.

By protecting budgets for revenue-generating programs such as football and men’s basketball, athletic directors – a majority of whom are male – can feel forced to cut smaller programs such as men’s swimming and wrestling in order to fund women’s programs.

Yet the benefits to women, even if not as much as they’d like, have been undeniable. The law has helped create a female sports culture where none existed and even relaxed rigid gender stereotypes in society.

Ms. Hutchins has seen all the progress of the law, and its pitfalls, up close.

Carol Hutchins was a self-described tomboy as a youth. She resisted makeup sessions with her two sisters to play sandlot baseball and football with her brothers and neighborhood kids.

But once she reached a certain age, her mother pulled her aside and told her girls don’t really play sports. Plus, she was annoying the boys. “There was nowhere to play organized sports,” Ms. Hutchins says of Lansing, Michigan, in the 1960s. Her brothers got to play on a baseball team sponsored by an insurance company. “I felt like I was different in a bad way, like, there was something wrong with me. ... I used to think I wanted to be a boy. And then I realized I didn’t want to be a boy. I wanted to be an athlete.”

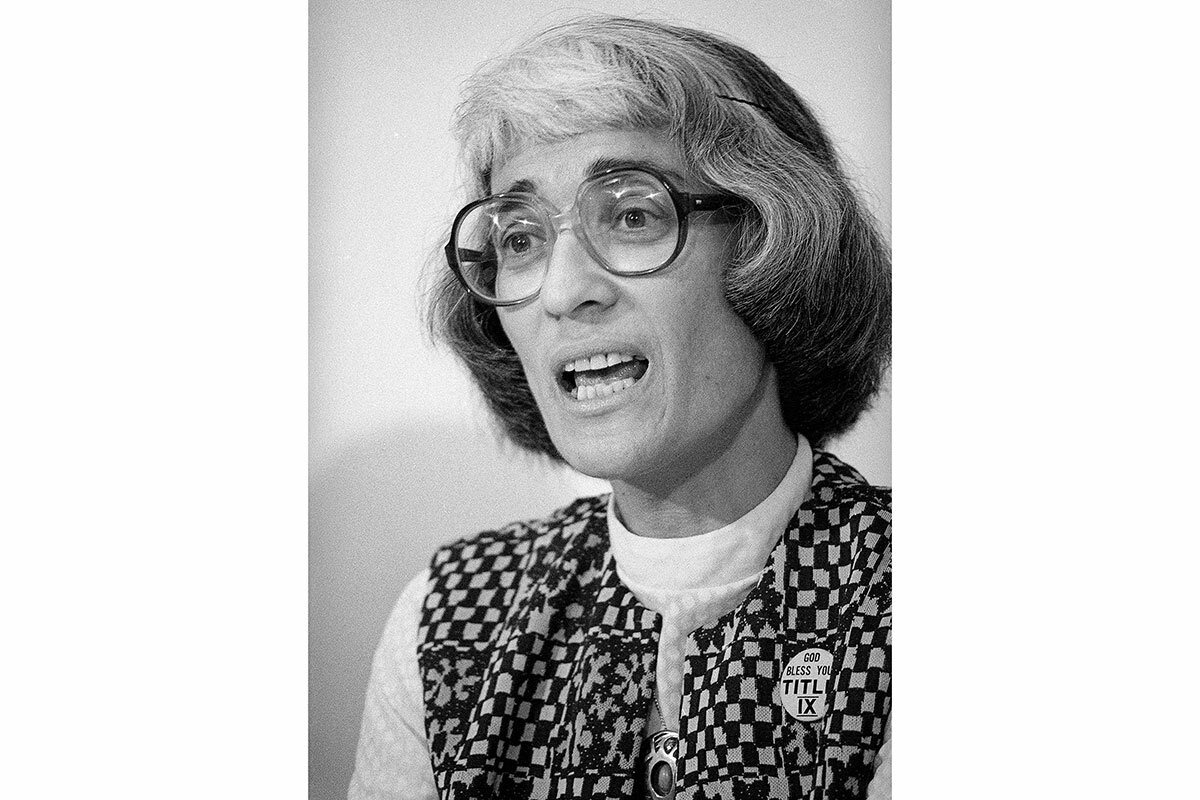

She would soon benefit from someone who lived half a country away and whose focus wasn’t sports at all. In 1970, Bernice Sandler was struggling to find a job. She had a Ph.D. in education from the University of Maryland, where she had been teaching part time, but she was not getting any full-time offers. Her younger male classmates, meanwhile, were having no trouble advancing in their careers. “You come on too strong for a woman,” one male faculty member suggested to her as an explanation.

At the time, women were entering the workforce in record numbers, but their participation was predominantly in traditional “female occupations”: nursing, child care, primary education, secretarial work. Schools reinforced that ethos. Girls were barred from auto mechanics and boys from home economics, explains Sarita Pillai, co-author of “More Than Title IX: How Equity in Education Has Shaped the Nation.”

Quota systems limited female enrollment at colleges and universities, further narrowing their job prospects. In 1972, only 12.4% of working women between the ages of 25 and 64 had a bachelor’s degree or higher, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

So Ms. Sandler took action. She joined the Women’s Equity Action League (WEAL) and began researching federal compliance for contractors. She studied the strategies that activists used in the civil rights movement and how they might apply to women in higher education. In a footnote, Ms. Sandler found a reference to an executive order amended by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1967 stating that entities receiving federal funding could not discriminate based on race, color, religion, national origin, and sex. Ms. Sandler, who died in 2019, described this as her “eureka” moment.

Universities that received federal aid and failed to hire qualified women and pay them accordingly were in direct violation of the mandate. It was an opening through which the “godmother of Title IX” would deploy a full-court legal press. Together with WEAL, Ms. Sandler launched a historic class-action suit, filing more than 250 complaints on behalf of all women in higher education.

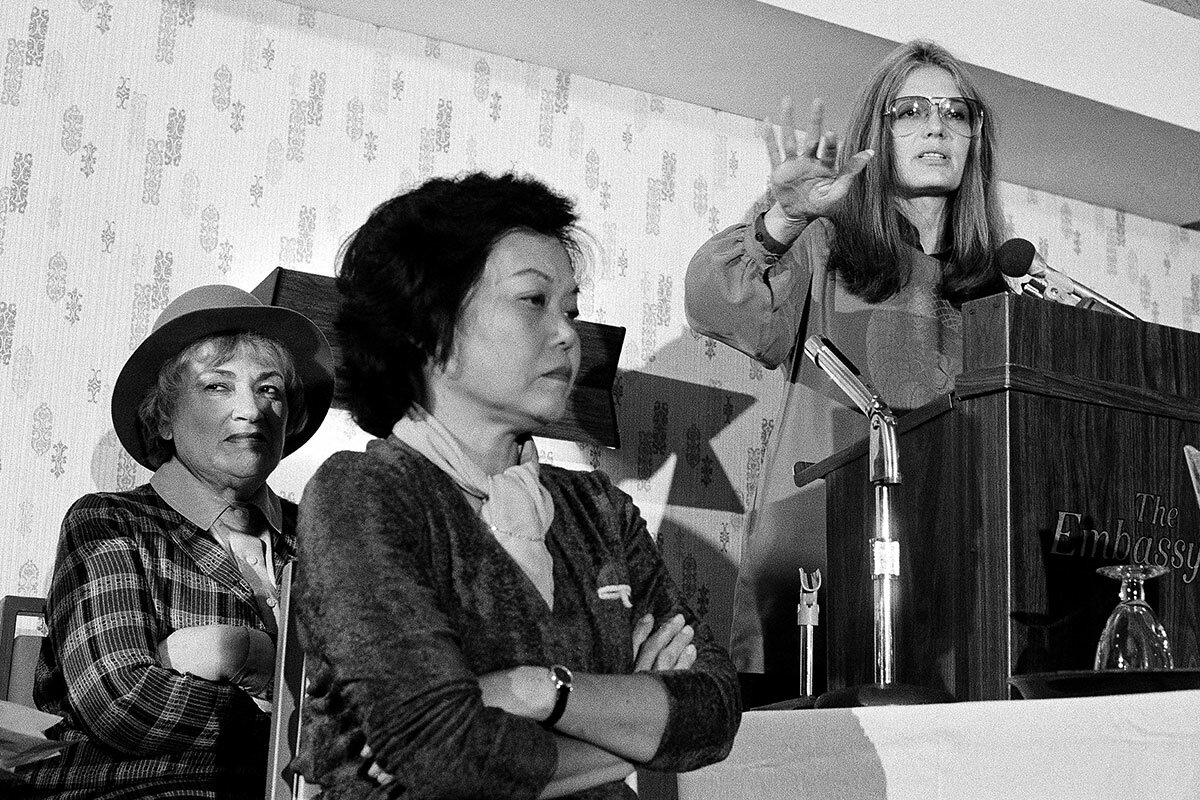

The avalanche of compliance requests spurred a series of congressional hearings on the issue. “Professionally, women in the United States constitute only 9 percent of all full professors, 8 percent of all scientists, 6.7 percent of all physicians, 3.5 percent of all lawyers, and 1 percent of all engineers,” Rep. Edith Green, a Democrat from Oregon, testified at one of the hearings in 1970.

Eventually, Ms. Green and Rep. Patsy Mink, a Democrat from Hawaii, and Democratic Sen. Birch Bayh of Indiana introduced bills in Congress. President Richard Nixon signed into law these 37 words as Title IX of the Educational Amendments of 1972:

“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Far from the halls of Congress, things began to change quickly, including at Everett High School in Lansing, where Ms. Hutchins was a sports-obsessed 10th grader. Even though she had barely heard of Title IX, by her senior year she had other athletic opportunities beyond cheerleading and informally arranged basketball games against girls at other schools.

“We got our first varsity basketball team and we had a real schedule,” she says. “We had uniforms, we had buses, and we had cheerleaders. I mean, my dream came true. I was so happy.”

Title IX would slowly begin to spur lawsuits and complaints across the country. And they weren’t just about expanding women’s participation in sports. Over the years, the law has become a pry bar to open up all kinds of opportunities for women. In one sense, it was a way to channel pent-up political energy that had been building since before the 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote in 1920.

“Title IX didn’t start all of these intense changes in society,” says Sherry Boschert, author of “37 Words: Title IX and Fifty Years of Fighting Sex Discrimination.” “There were social justice movements already going along that Title IX then just gave [women’s rights advocates] a better tool. All they were asking for was some kind of grievance procedure, some kind of way that the people who were being harassed and assaulted and discriminated against ... could complain and have it be heard by the system. That’s one of the beauties of the Title IX story. It’s a cast of thousands. ... It isn’t one hero or heroine who did all this.”

One prominent member of the cast was Ann Olivarius. She arrived at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1973, just four years after the college opened its undergraduate programs to women. But the thrill of attending one of the nation’s most hallowed halls of learning was soon replaced by outrage.

As an undergraduate researching the status of women at the university, who made up just a quarter of the student body, Dr. Olivarius noticed a pattern: Female students who reported accounts of sexual harassment and rape by faculty members had no protections from the university.

“We fundamentally could not understand why there was a disconnect,” says Dr. Olivarius, who runs a legal practice today that includes a specialty in sex discrimination. “Our view was that everyone had a mother at least, most had partners, they had daughters, they had cousins, they had sisters. ... Why would they look the other way?”

She gathered together plaintiffs, with the support of legal theorist Catharine MacKinnon and attorneys at the New Haven Law Collective. They filed a lawsuit in 1977 using an untested argument: By failing to effectively address complaints of sexual assault and harassment, Yale was violating Title IX. Only one of the plaintiffs’ claims advanced to trial. The rest were dismissed. But a single line written by U.S. Magistrate Judge Arthur Latimer in Alexander v. Yale changed history:

“It is perfectly reasonable to maintain that academic advancement conditioned upon submission to sexual demands constitutes sex discrimination in education.”

That line paved the way for grievance procedures in colleges across the nation. “The successful application of the law to sexual harassment ... as a form of sex discrimination in education ... kicked off a normative shift on college campuses,” says Celene Reynolds, a presidential postdoctoral fellow at Cornell University who studies Title IX. “And that shift is not complete by any means. We’re not living in a world where sexual harassment doesn’t happen anymore. But we are living in a world where it’s not accepted as part of life in universities.”

Although schools now have reporting mechanisms in place, rape on college campuses still happens. In a 2020 study by the Association of American Universities, 20.4% of female students, 20.3% of transgender and nonbinary students, and 5.1% of male students said they had experienced rape or sexual assault.

It is only in the past decade that schools have established robust systems for students to report sexual harassment under Title IX, according to Courtney Bullard, founder of Institutional Compliance Solutions, a Title IX consulting firm.

“I would argue that if you were to ask someone in 2010 who their Title IX coordinator is, they would have no idea what that even meant,” she says. “So much of the progress that happened with raising awareness, encouraging reporting, believing survivors when they come forward – that’s really happened in the last 10 or 12 years.”

While Dr. Olivarius was bringing her pioneering lawsuit in New Haven to expand the use of Title IX, Ms. Hutchins was frustrated with the way the law was being applied in her domain – gymnasiums.

True, she had seen tangible benefits from Title IX in her final years in high school and was grateful for the spot she now had on the basketball team at Michigan State University in East Lansing.

But she was noticing that not all was equal on campus. She saw male athletes getting more funding for uniforms, facilities, coaching, locker rooms, and food and lodging for away games. If the women’s games weren’t yet as competitive or popular, no one was investing in them to at least prove they could be.

When Ms. Hutchins heard in 1976 that a group of upper-level students on her basketball team was going to consult with Jean Ledwith King, a women’s rights lawyer, about suing for unequal treatment between men’s and women’s programs, she made a decision. “I’m in.”

It took the judge only an hour to rule in the women’s favor.

Since then, similar suits and the practical nudge of the law have spurred widespread changes on athletic fields across the country. In 1971, a year before Title IX was passed, fewer than 300,000 high school girls and 30,000 college women played sports. Today, those numbers have ballooned to 3.4 million in high school and more than 215,000 in college.

Still, none of this means that full equal opportunity under Title IX has been achieved, say its advocates. In 2019-20, American male athletes received $252 million more in athletic scholarships than female athletes, according to the Women’s Sports Foundation. Women make up less than half of NCAA coaches for women’s teams and hold less than a quarter of all college athletic director positions.

“I’ve seen athletic departments with highly qualified administrators and coaches who nonetheless don’t have comprehensive knowledge of the law,” says Dr. Pollick at the University of Michigan.

A fight is brewing, too, over plans by the Biden administration to add protections for sexual orientation and gender identity in Title IX – a move likely to bring another flurry of lawsuits.

“While we saw [Title IX] coming out of the feminist movement, so originally with a leftward-leaning political bent, now we [conservatives] actually see it as a shield,” says Sarah Parshall Perry, a senior legal fellow at The Heritage Foundation. “The conservatives are standing up to say the interests that were sufficient for protection in 1972 now need double protection because all it’s taking is for someone to identify as a female, even though they are a biological male, and take away scholarships, slots in admissions, competitive team roster slots.”

On a brisk spring day in Ann Arbor, it’s easy to see how far the country has evolved since those 37 words were codified in 1972 – and how far Ms. Hutchins has journeyed. Her office overlooks a $5 million softball complex, where she and a battalion of coaches run three-hour practices with Swiss watch efficiency. The lobby of their training building overflows with trophies. Their games appear on ESPN, and the 2,800-seat stadium regularly fills up with ticket-buying fans.

Over her 39 seasons as head coach, Ms. Hutchins, known in the college softball world simply as “Hutch,” has led the Wolverines to the NCAA Women’s College World Series 12 times, winning it once. She has clinched 22 Big Ten titles and helped produce 69 All-American athletes. She’s been named Big Ten Coach of the Year 18 times, has been inducted into numerous sports halls of fame, and has won more games than any coach – female or male – in Michigan’s storied sports history. She ended the 2022 season in May with 1,707 victories.

Yet despite the impressive résumé, Ms. Hutchins hasn’t forgotten how in 1985, when she first got the job as head softball coach, she had to mow her own field after doing morning secretarial duties. Or how in 2007, two years after winning the World Series, she took the risk of asking for a raise after the university awarded the men’s baseball coach, who was younger, less experienced, and less successful, a contract that doubled his salary. Ms. Hutchins challenged the discrepancy and eventually won her own more lucrative contract.

But it was never about the money, she says. “It’s about the value of women.”

And she doesn’t want her athletes to forget it, either. Educating her players about Title IX is a task Ms. Hutchins makes as much a part of her coaching as rotating her players through hitting and fielding drills. She often leads team discussions.

Lexie Blair, a star Wolverines outfielder from Winter Garden, Florida, recalls a rained-out game during a trip to California. Ms. Hutchins took the whole team to see “On the Basis of Sex,” the feature film about Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. They spent the bus ride back to the hotel discussing Title IX and gender discrimination. It all leaves an imprint on these young scholar-athletes.

“Hutch, you know, her thing is you want to leave the world better than you found it. And I feel like ... she can go out saying, ‘I left the world better than I found it,’” says Ms. Blair, a communication and media major who aspires to become a sports broadcaster. “She’s huge on leadership, huge on using your voice, huge on just taking the opportunity to expand knowledge and pass it on to other people. ... I think that’s something I’ll carry throughout my career and then throughout my life. [It’s something] that I want to do and pass on to younger girls.”

French public demands Macron compromise

In France, government policy usually comes down to presidential desire. But amid distrust of President Macron, the public has forced a rarer model of governance: one of cooperation and compromise.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

French President Emmanuel Macron may have beaten back the far-right challenge in April’s presidential election, but Sunday’s parliamentary results showed that he still has a long way to go to win over the support of the French public.

Mr. Macron’s party lost its absolute majority in the National Assembly in a major defeat, as the public vote split the legislative body into three mutually opposed political blocks. Over half of the French public chose to stay home on voting day last weekend, in what was widely seen as an act of resistance more than apathy.

The coming months will be a formative challenge for the French president, who has been accused of a unilateral style of governing. Mr. Macron will need to find ways of promoting unity, or France risks being frozen.

“France is experiencing a crisis of representation – people don’t feel like their worries of daily life, their desires, are taken into account by politicians, and the results of this election are evidence of that,” says French sociologist Roger Sue. “Mr. Macron will be forced to win back his government if he wants to avoid the dissolution of parliament. He has no choice but to cooperate.”

French public demands Macron compromise

Just two months after his victory in the presidential elections, French leader Emmanuel Macron is already facing a political crisis. In the second round of legislative elections on Sunday, Mr. Macron suffered historic losses that stripped his party of its absolute majority in parliament and that will oblige him to reach out to opposition groups.

Now, Mr. Macron must deal with a National Assembly perforated into three mutually opposed political blocks, and a public that has lost confidence in its political class. Over half of the French public chose to stay home on voting day last weekend, in what was widely seen as an act of resistance more than apathy.

The coming months will be a formative challenge for the French president, who has been accused of a unilateral style of governing. Mr. Macron will need to find ways of promoting unity and cooperation with opposition parties, or France risks being frozen.

“This culture of compromise is one we will have to adopt,” Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire said after the election results became known. Budget Minister Gabriel Attal suggested that, while the results were far from optimal, they provided the opportunity to “overcome divisions.”

The president will also have to regain public trust. “France is experiencing a crisis of representation – people don’t feel like their worries of daily life, their desires, are taken into account by politicians, and the results of this election are evidence of that,” says French sociologist Roger Sue.

“The fracture between civil society and politicians is not going to disappear,” he says. But “at the same time, Mr. Macron will be forced to win back his government if he wants to avoid the dissolution of parliament. He has no choice but to cooperate.”

70% of voters dislike politicians

Mr. Macron’s “Ensemble!” alliance claimed 245 seats on Sunday, but that was not enough for an overall majority. The newly created Nupes coalition, a left-wing alliance headed by firebrand Jean-Luc Mélenchon, took 131 seats while Marine Le Pen’s far-right National Rally party picked up 89 seats – the most in the party’s history.

Unlike in previous “co-habitation” scenarios in France – in which an opposition party won the parliamentary elections – Mr. Macron still holds sway in the parliament. But the loss of an absolute majority means he will struggle to pass legislation, particularly a divisive bill dear to his heart that would see the retirement age upped from 62 to 65.

Mr. Macron’s closest ally, the right-wing Les Républicains party, announced on Monday that it would not form a governing coalition with the president.

“In theory, the current situation is more paralyzing to the country than a ‘co-habitation.’ We really have a fragmented political situation,” says Gilles Ivaldi, a political scientist at CEVIPOF Sciences Po, a think tank in Paris. “Mr. Macron is going to have to work case by case, bill by bill. It will be more difficult to find compromises.”

But the current political climate also leaves room for opportunity and a potential move away from France’s traditionally monarchical style of leadership. Unlike its European neighbors Spain and Germany, where the proportional representation voting system lends itself to compromises, France is not accustomed to the coalition style of government.

Even less so under Mr. Macron, who has said he aspires to be a “Jupiterian” president – an allusion to the Roman god – and whose top-down governing style and reluctance to build consensus sparked the yellow vest protest movement.

While the government has toyed with participatory democracy – such as its Citizens’ Convention on Climate – it has balked at the idea of citizen referendums, proposed by several opposition parties and yellow vest activists.

The 46% turnout rate at Sunday’s election is a reflection of the current disconnect between the French people and their politicians. According to research last January by CEVIPOF Sciences Po, which has measured public opinion since 2009, 70% of French people have a negative view of politicians – 39% with mistrust and 17% with disgust.

A little maturity, now?

Creating stronger links between grassroots organizations, citizen groups, and politicians is one avenue that Mr. Macron should explore in order to restore faith in French politics, say some observers.

“One major reason for this lack of trust is that the public doesn’t see the concrete impact of their vote,” says Marion Le Blanc, co-founder and general secretary of Civic Power, a nonprofit that uses technology to encourage representative democracy. The group has created a digital platform where the public can vote on bills, such as France’s COVID-19 vaccine pass. Legislators are alerted once 1,000 people have voted.

“We ask people to vote twice every five years for a political program which we may not be entirely on board with,” says Ms. Le Blanc. “But we need a more continuous, refined democracy if we want to restore confidence.”

Though Mr. Macron has not spoken publicly since the elections, his close advisers are giving the impression that the government is prepared to seek new pathways for consensus-building. The next few months will be critical, as the public and opposition parties assess whether Mr. Macron can unite instead of divide. If he succeeds, he may usher in a new era in French politics.

“We should see fewer protests by the public because their representatives are all there [in parliament] now,” says Mr. Ivaldi. “The problem will be for Mr. Macron to convince the opposition parties. But I’m optimistic. Things might take longer now, but there won’t be a total blockage. I think we can expect a little maturity from French politics and that’s not a bad thing.”

Will slain journalist’s death spark change in Amazon?

Journalist Dom Phillips and Indigenous expert Bruno Pereira were killed in the Amazon this month. A friend finds parallels between this tragedy and another Amazon murder some 34 years ago, and hopes these latest deaths can spark similar action.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Andrew Downie Contributor

When environmental activist Chico Mendes was killed protecting his home and community from illegal loggers in the Amazon some three decades ago, his death seemed to shake the world awake to the destruction and dangers facing the rainforest.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Mr. Mendes these past two weeks, ever since my friend Dom Phillips went missing in the western Amazon with his traveling companion, the Indigenous advocate Bruno Pereira.

Dom was writing a book about sustainable development in the region, and Bruno, who had worked with Indigenous tribes there for years, opened doors to the isolated communities where many of Brazil’s estimated 235 Indigenous groups live.

They were killed on June 5 as their boat sped up the Itaquaí River, apparently ambushed by men who Bruno suspected were fishing protected stocks of turtles and pirarucu, one of the world’s largest freshwater fish.

When I think about Dom’s death, I want to believe that I haven’t lost a friend for nothing.

Perhaps naively, and certainly optimistically, I hope we’re witnessing a Chico Mendes moment. The Amazon is a lot more vulnerable than it was in 1988, and the tipping point – the moment when it can no longer recover from drought, fires, and deforestation – is edging closer.

Will slain journalist’s death spark change in Amazon?

In December 1988, when most people were out buying turkey and Christmas crackers, something happened in the Amazon that changed the way the world saw Brazil and the nascent environmental movement.

Three days before Christmas, a man was murdered in the southern reaches of the rainforest. He was a rubber tapper named Francisco Mendes, although everybody called him Chico.

Mr. Mendes had no formal schooling, but he was a born leader. When loggers threatened to cut down rubber trees to create cattle pastures, he ran to the front lines to stop lumberjacks from using chain saws and bulldozers to decimate the forest that Mr. Mendes and his community called home.

It cost him his life.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Mr. Mendes these past two weeks, ever since my friend Dom Phillips went missing in the western Amazon with his traveling companion, the Indigenous advocate Bruno Pereira.

Dom was writing a book about sustainable development in the region, and Bruno, who had worked with Indigenous tribes there for years, opened doors to the isolated communities where many of Brazil’s estimated 235 Indigenous groups live.

They were killed on June 5 as their boat sped up the Itaquaí River, apparently ambushed by men who Bruno suspected were fishing protected stocks of turtles and pirarucu, one of the world’s largest freshwater fish.

Three men are in custody, one of whom confessed to shooting the pair and burying their bodies deep in the forest. Another five people are wanted by police.

“How To Save the Amazon”

I met Dom at the end of the 2000s, when he came to Brazil to escape the hustle of London, where he had been a successful music writer. I was a foreign correspondent in São Paulo, and Dom was completing a book called “Superstar DJs Here We Go!” about the electronic music boom. He was quiet and easygoing, but always eager to learn about his new home, and I was impressed by the way he listened more than he talked, a rarity among most journalists I know.

When I think about his killing, I want to believe that I haven’t lost a friend for nothing, that something good can come of this. I want to believe that Dom’s wife, Alessandra Sampaio, whose poise and dignity have been as admirable as they are heartbreaking, will be rewarded in some way. And I want to believe that his work was not in vain.

On the last of these wishes, at least, there’s reason for optimism.

Dom had been reporting his book for at least three years. Entitled “How To Save the Amazon,” it was a tough sell at first, or at least not a lucrative one, and he struggled to make ends meet on his meager advance.

But he was determined to get his ideas into print. He talked to Indigenous people, police, cattle ranchers, and illegal miners, and he was aware that his book would not please everyone. He believed these stories were urgent, and many of the people he spoke with still do. Right now, friends, colleagues, his editor, and his agent are discussing how to complete his work. A bestselling book, even by – or maybe especially by – a posthumous author, would shine a light on the issues Dom so cared about.

A Chico Mendes moment?

What connects the murder of Mr. Mendes to the killings of Dom and Bruno 34 years later?

The answer is what came after Mr. Mendes’ murder, and what could happen now.

The international community united in outrage at Mr. Mendes’ murder, which led to widespread change in Brazil. The South American nation introduced a series of laws and regulatory frameworks designed to protect the rainforest and the Indigenous people who live there.

The laws are not always enforced, but they are there, and that marked a big step forward.

Will Dom and Bruno’s deaths have the same effect? I hope so.

In terms of outrage at least, the parallels are clear. In the days after they disappeared, a host of celebrities took to social media to register their disgust.

Former soccer player Pelé, singer-songwriters Anitta and Caetano Veloso, and U.S. actor Mark Ruffalo were among the many who demanded action, both to find the missing men and to investigate what happened to them and why.

It was reminiscent of the activism sparked by Mr. Mendes’ murder, when former Police frontman Sting took the lead, meeting with Indigenous people and organizing regular “Rock for the Rainforest” gigs. Consumers and companies woke up to the demand for natural products and sustainable development. Mr. Mendes gave the environmental movement a martyr to rally behind.

Perhaps naively, and certainly optimistically, I hope we’re witnessing a Chico Mendes moment. The Amazon is a lot more vulnerable than it was in 1988, and the tipping point – the moment when it can no longer recover from drought, fires, and deforestation – is edging closer. Drastic action is needed.

The Indigenous people who live there are also under increasing attack. Brazil’s far-right President Jair Bolsonaro has encouraged loggers, miners, and hunters to develop the region, and the number of invasions of Indigenous land has more than doubled since he took power in 2019. Deforestation in the Amazon this year hit a 15-year high.

But when it comes to concrete action, there is one important difference between 1988 and today. Back then, Brazil was emerging from a 21-year military dictatorship. It was embarrassed by Mr. Mendes’ killing and reacted like the modern and progressive democracy it wanted to be.

Today, the military is ascendant again. Mr. Bolsonaro is a former army captain with a general as his vice president. Before taking office, he vowed not to give Indigenous people “one more square centimeter of land,” and he has proudly kept that promise.

With his development-at-all-costs ethos, Mr. Bolsonaro has undermined environmental oversight bodies and ignored existing legislation. The Indigenous agency Funai is so poorly funded that officials in Amazonia had to hire boats to search for their former colleague, Bruno, because their own fleet had been left to rot.

Justice and change

I’ve lived in Brazil for almost all of this century. I’ve seen more senseless murders than I care to remember, and I’ve seen almost as many campaigns for justice. I know that justice is slow and that change, when it does come, is often too little and often too late.

When I speak to people about the events of the last two weeks, there are a number of agreements. Dom and Bruno were good people; the Amazon and the Indigenous people who live there are under serious threat; Mr. Bolsonaro and his policies represent a big part of that threat.

We can’t bring Dom and Bruno back. But we can honor their work. If there’s a silver lining in all this, it will be a renewed focus on the plight of Brazil’s Indigenous people, just as the death of Mr. Mendes focused attention on the plight of the rainforest. They need land, resources, and most of all protection.

Brazil has a presidential election in October. If Dom’s and Bruno’s deaths spark a reaction at the polls, that would be one indication they did not die in vain.

Points of Progress

Generosity for kids, from wartime schooling to music education

In our progress roundup, some adult Ukrainian refugees in Poland made normality a priority for children escaping the war, by creating a new school in Warsaw. And for one virtuoso pianist, his growing venture is sharing music with schools that have slim resources for the arts.

Generosity for kids, from wartime schooling to music education

In more cases of leading by example, San Francisco is teaching other cities how its well-established composting program works. And in southeastern Africa, women have been patiently reforesting the shoreline with mangroves for 15 years.

1. United States

San Francisco, an early adopter of urban composting, now serves as a model for others around the world. The city conducted a “waste characterization” study in 1996 that showed a third of the refuse could be composted, which experts say is one of the simplest, most low-tech ways to combat climate change by reducing methane production. More than 500 tons of compost are collected each day, eliminating around 80% of waste from landfills. Over 135 countries have sent delegations to learn from San Francisco.

When composting and recycling became mandatory in 2009, the city’s waste management company, Recology, offered compost pails, labels, signs, tool kits, and training to residents and businesses. One particularly effective strategy has been getting children involved. “The best way to get adults to compost is to get composting programs running in schools,” said Recology public relations manager Robert Reed. “Those kids go home and say, ‘Why don’t we compost at home?’” A facility turns food scraps into high-quality compost, affectionately called “black gold,” which is then sold to local farms, orchards, and vineyards to offset program costs.

Source: Reasons To Be Cheerful

2. Poland

Students from war-torn Ukraine were able to finish the school year in Warsaw – at a school created just for them. Since conflict broke out, nearly 7 million refugees have fled Ukraine, with over half landing in neighboring Poland. In March, a group of Ukrainian educators came together to found the Warsaw Ukrainian School, staffed entirely by Ukrainian refugees and serving 270 students. Switching to the Polish curriculum can set students back in their education, so these students follow the Ukrainian curriculum, while learning Polish to integrate into local life.

Operating out of an unused college building in southwestern Warsaw, the school prioritized admission for students whose schools had been destroyed. “We decided that we will take children from the hottest points of Ukraine, like Mariupol, like Bucha, like Izum,” said deputy director Oksana Vakhil. When the students first started, “I saw just empty eyes,” she said.

Since then, and with the support of mental health staff and teachers trained to identify and address trauma, students have come to feel at home in their new school. “We have just a little piece in Warsaw, a little piece of Ukraine,” said 15-year-old Diana Norchak.

Source: NPR

3. Pakistan

A safe, new bus system means more women are traveling independently in Peshawar, Pakistan. A 2016 survey found that 90% of women in the city felt unsafe using public transport, with harassment often deterring them from studying or joining the workforce. Inadequate public transportation contributes to the country having one of the lowest female workforce participation rates in the world. But since the launch of the Bus Rapid Transit system in 2020, the percentage of female bus travelers has grown from 2% to 30%. The buses reserve a quarter of the seats for women and are equipped with CCTV cameras and guards. Bus stations are well lit, and the BRT has hired more female employees.

Experts say there’s still room to make sure women feel safe traveling to and from home, given poor street lighting, limited pedestrian infrastructure, and a lack of law enforcement in secluded areas. But the new buses, which are cheaper and often faster than alternative forms of transport, have made a significant difference. “I was never allowed to use public transport alone. When I got married, I would wait for my husband to take me to the market since I was scared of going out unaccompanied,” said Madiha Shakir, who recently began using the bus system. “I can’t tell you how liberating it has been for me.”

Source: Thomson Reuters Foundation

4. Mozambique

Women in coastal Mozambique replanted 125 hectares of mangroves damaged by flooding. In 2000, floods caused by Tropical Cyclone Eline destroyed half of the mangroves in the estuary where the Limpopo River opens to the Indian Ocean. Over the past 15 years, women from nearby communities have been working to restore the delicate mangrove ecosystem, which provides communities access to small fish, crabs, and wood while reducing erosion, filtering seawater, and absorbing atmospheric carbon.

It can take decades for mangroves to mature, but trees planted in the past five to 10 years now stand over 2 meters (6 1/2 feet) tall. Planting is best done during the spring tides, and an additional 400 hectares (988 acres) are needed to restore the gnarled trees to their original coverage. The project was initiated by Mozambique’s National Agency for Environmental Quality Control and is currently funded through the Nairobi Convention, an agreement among 10 countries to protect the Western Indian Ocean.

Source: Hakai Magazine

World

“Piano labs” are opening in schools in several countries, preserving access to music education in underserved areas. Music programs are often targeted for budget cuts in resource-stretched public schools. So Chinese superstar pianist Lang Lang, whose 2019 “Piano Book” was the bestselling classical album of the year, looked to fill in the gaps.

The Lang Lang International Music Foundation provides keyboards, curriculum, teacher training, and grants to public schools serving low-income students, with the conviction that music “heals, unites and inspires, and it makes us better people.” So far, the team has opened 104 piano labs in China and 84 in the United States, giving piano access to over 180,000 students, generally between the ages of 7 and 12. The model is now expanding to the United Kingdom.

Source: The Guardian

Listen

Q&A: A ‘Title IX baby’ on the women who made it happen

To report today’s story – one with a lot of personal meaning for me – I tracked down some of the many women who worked to make it a reality. I spoke to the Monitor’s Samantha Laine Perfas about the experience.

Fifty years ago, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 required that all women had equal access to educational opportunities. Since its passing, it has been applied to everything from education to sports to sexual harassment to transgender rights. The Monitor’s Kendra Nordin Beato and Tara Adhikari reported on the anniversary of this groundbreaking law by tracing the arc of its progress over the past 50 years. Kendra said that path has been anything but straightforward and simple.

“I knew from the get go that approaching this story was trying to fill a Dixie cup at Niagara Falls,” says Kendra. “There’s probably been no girl or woman in the United States today who hasn’t been impacted.”

The law fundamentally changed society when it allowed women in the door. But while it created opportunities, generations of women had to step up and fight for actual inclusion and equality. That required incredible amounts of courage and resilience.

“It’s not natural to stand up and ask for equal treatment under the law, and it takes a group of people inspiring each other to do that,” Kendra says. “You can see human potential when you create spaces of equal treatment and equal opportunity.” – Samantha Laine Perfas, senior multimedia reporter, and Jingnan Peng, multimedia producer

Note: This audio report is meant to be listened to, but we appreciate that doing so is not an option for everyone. You can click here for a full transcript of Sam’s Q&A with Kendra.

Monitor Backstory: Voices of Title IX

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Colombia’s big break from the past

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The election of Gustavo Petro as president of Colombia on Sunday marks the first time that South America’s second most populous nation will be ruled by a leftist. Yet Mr. Petro’s political leanings may be less helpful in understanding what kind of leader he will be than a slogan graffitied on walls across the poorest neighborhoods: “On the other side of fear is the country we dream of.” That aspiration reflects a society that is rejecting apathy for hope and fear for democratic renewal after decades of violence and hardship.

Mr. Petro has an unusual résumé. He is a former guerrilla, mayor, congressman, and senator. He holds a master’s degree in economics. His running mate, Francia Márquez, is an environmental activist and human rights lawyer who grew up in poverty. She will be Colombia’s first Black vice president.

The two leaders personify the popular demand for change that has fueled a leftist shift across Latin America. That “pink tide” reflects a yearning for a break from decades of rule by established parties marked by corruption and economic disparity.

Throughout Latin America, voters are embracing peaceful change at the ballot box. In Colombia, they expressed hope that Mr. Petro represents a new era of leadership by listening.

Colombia’s big break from the past

The election of Gustavo Petro as president of Colombia on Sunday marks the first time that South America’s second most populous nation will be ruled by a leftist. That fact alone troubles some observers. Mr. Petro seeks to renew ties with Nicolás Maduro, the repressive socialist dictator who has overseen economic collapse in neighboring Venezuela. Mr. Petro’s proposals to halt new petroleum exploration and to redistribute wealth, critics fear, threaten one of the region’s most successful economic recoveries from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet Mr. Petro’s policies and political leanings may be less helpful in understanding what kind of leader he will be than a slogan graffitied on walls across the poorest neighborhoods of cities like Bogotá, the capital: “On the other side of fear is the country we dream of.” That aspiration reflects a society that is rejecting apathy for hope and fear for democratic renewal after decades of violence and hardship.

Mr. Petro has an unusual résumé. He is a former guerrilla, mayor, congressman, and senator. He spent 16 months in prison, where he says he was tortured. He holds a master’s degree in economics. His running mate, Francia Márquez, is an environmental activist and human rights lawyer who grew up in poverty. She will be Colombia’s first Black vice president.

The two leaders personify the popular demand for change that has fueled a leftist shift across Latin America in countries like Mexico, Peru, Honduras, and Chile. That “pink tide” reflects a broad yearning for a break from decades of rule by established parties marked by corruption and economic disparity. As Transparency International noted in its latest annual study of corruption in Latin America, the region saw an uptick in serious attacks on key democratic freedoms like speech and the media that defend societies against corruption. In Colombia, it noted “serious excesses in the use of police force” to quell mass demonstrations.

Violence is also up, according to the United Nations. In the first two months of 2022, violence escalated by 621% over the same two months in 2021, resulting in the displacement of roughly 275,000 people.

In past elections, corruption and violence contributed to widespread cynicism among voters. A national dialogue organized by six Colombian universities last year brought together more than 5,000 people in nearly 1,500 conversation sessions. The participants found that corruption, violence, and economic inequality contributed to widespread apathy and mistrust.

Significantly, however, 70% said that dialogue and a willingness to listen to diverse opinions generated trust and showed a model for how government can rebuild confidence in democracy through transparency.

That may partly explain Mr. Petro’s appeal. He promised to tackle corruption and restart a peace process between the government and a former rebel army that stalled under outgoing President Iván Duque Márquez. Like his newly elected reform-minded counterparts in Honduras and Chile, he starts without much political leverage. He won with just over 50% of the vote, and his Historic Pact party will have to find partners in Congress to enact his proposals.

But the election showed a rekindling of hope among voters. Martha Inés Romero of Pax Christi International told the international press agency Pressenza that, partly as a result of Mr. Petro’s independence from past ruling parties, younger Colombians had more confidence in the power of their vote. “Colombia deserves a different option, one that shows possibilities for the incorporation of those who have been historically excluded, and we have hope that there will be a real change,” she said.

Throughout Latin America, voters are embracing peaceful change at the ballot box. In Colombia, they expressed hope that Mr. Petro represents a new era of leadership by listening.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

How do we get things done together?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Susan Stark

When we’re humble enough to let God – rather than a personal agenda or willfulness – guide us, we’re paving the way for productive and harmonious teamwork.

How do we get things done together?

Francis Kéré, who recently won the prestigious Pritzker Prize in architecture, proved the value of strong teamwork when he mobilized his whole village in Burkina Faso to build an energy-efficient school. As Mr. Kéré told Dutch magazine De Groene Amsterdammer, “Everyone can contribute to tackling the major issues of our time.”

In our efforts to support a good cause, we might ask what leads to the best results. The high achievers in the Bible looked to God, the source of all good, for guidance as they took on challenges. David, a gifted leader and king of Israel, prayed, “Teach me to do thy will; for thou art my God: thy spirit is good; lead me into the land of uprightness” (Psalms 143:10).

Successful teamwork, whether a team of two or 20, depends on a humble willingness to do what’s best for a shared good purpose – or as the Bible terms it, to do God’s will. When Christ Jesus described his unparalleled healing work for humanity, he said, “I came down from heaven, not to do mine own will, but the will of him that sent me” (John 6:38).

The God that Jesus worshiped and obeyed is infinite Spirit, whose irresistible will, or law, governs Spirit’s whole creation. Jesus was doing the will of God when he fed crowds of more than 5,000 with little food at hand, healed the sick, and raised the dead. Through these acts Jesus brought out the heavenly harmony and power of divine Love, God. It was part of his mission to show us that we can also experience God’s wisdom and all-power in the healing works and tasks we undertake. He taught us to pray in the Lord’s Prayer: “Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven” (Matthew 6:10).

Obedience to God’s will is an acknowledgment that God is all-powerful good, the one divine Mind, wherever we are and whatever we are doing. Mary Baker Eddy, who discovered Christian Science, spiritually interpreted the above line in the Lord’s Prayer as, “Enable us to know, – as in heaven, so on earth, – God is omnipotent, supreme” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 17).

With even a small understanding of the fact that God is the one true Mind, we learn of each person’s right to know the powerful, intelligent direction of God. Our spiritual and real nature is the reflection of this divine Mind, which makes us capable of intelligent decisions and harmonious teamwork. Unity, love, and patience are the presence and action of Christ in human consciousness, lighting the way for all. At the same time, the Christ alerts us to action that is mistaken and unproductive because unlike the goodness of the Mind that is God.

The practice of Christian Science doesn’t try to force cooperation but gives each person room to respond to the Mind of Christ as their real Mind, who knows, loves, and directs the individual, perfect idea He created – spiritual man. This true identity of each of us becomes clearer to all as we pray to do God’s will, which unifies action as the roadblock of personal willfulness is dissolved by divine Love.

Because there is one true Mind, having even a single person on a team who believes in and yields to God’s supremacy and wisdom as Christ Jesus did benefits the whole group. There is a spiritual fact behind one individual’s listening to God – the fact that there is no possible insubordination to the will of God. Mind’s idea or reflection, which we all are in truth, cannot disobey or stray from its source.

We may be working in one little space, but our contribution is part of the larger, invincible good that forwards humanity’s progress. Science and Health describes our inevitable part in God’s purpose: “The scientific unity which exists between God and man must be wrought out in life-practice, and God’s will must be universally done” (p. 202).

What a joy it is to see God’s will in action as we work with others in realizing our dedication to accomplishing good.

Adapted from an editorial published in the June 20, 2022, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

A message of love

Running of the dogs

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow, when we’ll introduce you to three Ukrainian girls wounded in the war. Their recoveries trace a range of responses to the abrupt loss of youthful innocence.