- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Some like it hot

As summer heat waves start hitting, I think of my childhood in the California desert towns of El Centro and Blythe – often the nation’s hottest spots.

As staff writer Luke Cregan reports today, a heat wave is relative: It’s the lingering of “abnormally” high heat. But what about a place where three-digit temperatures are not abnormal – when every summer day hits 100-and-something?

I know heat waves can be deadly, but where desert heat is the norm, it can actually be a fond memory. That’s especially true for those of us 1950s, ’60s, ’70s kids who ran barefoot like wily coyotes from one telephone pole shadow to the next and on white painted road lines which were “cooler” than the sizzling asphalt. I know this from experience, but also from desert community Facebook pages where I posted the question: “How did we do it?”

I got more than 200 comments. Desert natives are proud of their toughness under the searing sun and nostalgic about the trade-offs. They recall stepping out into 120-degree air wearing hoop earrings that burned their neck before they got to the car. They remember the bank sign on Main Street that blinked “114-degrees, 9:40 p.m.” But then they could detour to the lavish chill of AC at the public library or movie theater, float a hundred-pound block of ice in a swimming pool, or stop to sip from any old garden hose (no one carried water, no one).

Commenter Dennis Schwettman recalls that his mom – a waitress – owned a house near El Centro in the 1950s with no AC, no evaporative “swamp” cooler. “I didn’t know it was a hardship” to sleep in 100-plus-degree heat wrapped in a wet sheet, he told me by phone.

How did we do it? We adapted.

We’re adapting still.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

After Supreme Court ruling, can EPA still tackle climate change?

Today the Supreme Court addressed a balance-of-powers question: the role of Congress versus agencies in setting federal regulations. The ruling complicates the already-difficult politics of addressing climate change.

-

Stephanie Hanes Staff writer

On the final day of a historic term, the U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday placed major restrictions on the ability of the federal government to address climate change.

The 6-3 ruling was narrower in scope than some environmental advocates had feared from the conservative supermajority. But it has the potential to significantly alter federal regulatory power over what is widely viewed as the world's most urgent environmental issue.

The decision hinged on an area of law known as the major questions doctrine – essentially that federal agencies can’t take major actions without clear direction in law from Congress. At issue in the case was how much leeway the Environmental Protection Agency has to regulate power plant carbon emissions under the Clean Air Act – a law that was not designed to address climate change.

For those wary of the executive branch taking unilateral actions that affect their lives, today's ruling is a win. For those who question the ability of Congress to act quickly and effectively in response to the evolving threats of climate change, the ruling is a serious blow.

“Action through the EPA is one of the few remaining [federal] tools to really make progress on emissions reductions,” says Lindsey Walter, deputy director for climate and energy at Third Way, a center-left think tank.

After Supreme Court ruling, can EPA still tackle climate change?

On its final day of a historic term, the U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday placed major restrictions on the ability of the federal government to address climate change.

The 6-3 ruling was narrower in scope than some environmental advocates had feared from the conservative supermajority. But while it won’t have the immediate transformative effects of some of the court’s other major decisions this term, it has the potential to significantly alter federal regulatory power over what is widely viewed as the most urgent environmental issue for the nation – and the world.

In its decision, the high court fleshed out a vague area of law known as the major questions doctrine – essentially that federal agencies can’t take major actions without clear direction in law from Congress – and how it applies to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Absent explicit congressional action – for which the Biden administration has been lobbying, so far fruitlessly – federal courts may now be poised to play a major role as referees in future EPA efforts to tackle climate change.

For those wary of the executive branch taking unilateral actions that affect their lives, today’s Supreme Court ruling is a win. But for those who question the ability of Congress to act quickly and effectively in response to the evolving threats of climate change, the ruling is a serious blow.

“Action through the EPA is one of the few remaining [federal] tools to really make progress on emissions reductions,” says Lindsey Walter, deputy director for climate and energy at Third Way, a center-left think tank.

“While this is a disappointing decision, the court has left the door open for the EPA to set strong standards to reduce emissions from power plants,” she adds. “Now the EPA must move quickly to issue a new rule.”

Ruling on a defunct Obama-era plan

The case decided on Thursday, West Virginia v. EPA, arose from an unusual posture – meaning there were serious questions about whether the justices should even have heard it.

The case concerned the Clean Power Plan, a policy advanced by the Obama administration in 2015 that never went into effect. The Trump administration later replaced the CPP with its own policy, which also never went into effect, and the Biden administration said it had no intention of re-implementing the CPP.

The fact that the policy is not in effect, and likely will never be in effect, would typically be strong grounds for the Supreme Court to not consider the issue. But the court here decided otherwise. It then moved to the core question of the case: whether, in a section of the Clean Air Act, Congress empowered the EPA to restrict carbon dioxide emissions from power plants.

Congress did no such thing, wrote Chief Justice John Roberts in the majority opinion.

“Capping carbon dioxide emissions at a level that will force a nationwide transition away from the use of coal to generate electricity may be a sensible ‘solution to the crisis of the day,’” he added. But “a decision of such magnitude and consequence rests with Congress itself, or an agency acting pursuant to a clear delegation from that representative body.”

The high court’s ruling is limited to that decision, Chief Justice Roberts stressed – a relatively narrow outcome, according to some experts. Essentially, the EPA cannot use that section of that law (the Clean Air Act) for that purpose (restricting emissions from power plants) in the broad manner outlined in the CPP. That is all.

In her dissent, Justice Elena Kagan painted a more troubling picture of where the ruling now leaves the country.

With its decision, the Supreme Court strips the EPA “of the power Congress gave it to respond to ‘the most pressing environmental challenge of our time,’” she wrote.

And not only that. The court has limited the EPA’s ability to regulate carbon emissions, she added, but “both the nature and the statutory basis of that limit are left a mystery.”

“How far does its opinion constrain EPA? The majority makes no effort to say,” she continued.

What next for U.S. climate policy?

What Chief Justice Roberts – and, in a separate concurrence, Justice Neil Gorsuch – wrote is that regulatory authority in an area as politically and economically important as climate change must be determined by Congress, not by the EPA or other executive branch agencies.

“When Congress seems slow to solve problems, it may be only natural that those in the Executive Branch might seek to take matters into their own hands,” wrote Justice Gorsuch in his concurrence. “But the Constitution does not authorize agencies to use pen-and-phone regulations as substitutes for laws passed by the people’s representatives.”

That assertion in particular left many environmental groups frustrated.

There have been numerous proposals for legislative climate action in recent years, from a national price on carbon, to tax incentives for carbon capture technology, to widespread emissions regulations. But most of these efforts have stalled. The Senate is still negotiating a package that could extend tax incentives for renewable energy sources and subsidize other climate-friendly technologies. But for the most part, advocates say, Congress has fallen well short of any sort of widespread climate action.

“Congress has not passed, and never even seriously considered, a federal renewable energy standard, leaving it up to a patchwork of state standards ... to shift the electricity sector from fossil fuels to renewables,” says Basav Sen, director of the climate policy project at the Institute for Policy Studies.

“It continues to overfund highway sprawl and underfund public transportation,” he adds.

That said, from economics to politics, much has changed since 2015 that could make congressional action more likely.

Over the past decade, the price of renewable power has plummeted, undercutting many fossil fuel sources. In 2020, renewables – including wind, hydroelectric, solar, biomass, and geothermal energy – became the second most prominent electric-power source in the United States after natural gas, according to the Energy Information Administration. Coal consumption, meanwhile, has dropped.

There has also been a shift in attitude about climate change in general. Fewer people deny that climate change exists, according to nationwide surveys. And increasingly, the political debate over climate action has to do with the “how” – whether to depend on new technology such as carbon capture, and how fast to phase out fossil fuels.

Furthermore, Thursday’s ruling – on its face, at least – still leaves the EPA and other agencies with regulatory tools to choose from, experts say.

The court did not dispute that greenhouse gases were a pollutant, nor did it say that climate change was an issue that only Congress could address, for example.

In the U.S., the transportation sector is the leading greenhouse gas emitter (accounting for 27% of emissions in 2020, just ahead of the electricity and industrial sectors). Nothing in the ruling would impact the EPA’s ability to regulate tailpipe emissions – or the U.S. Department of Transportation’s fuel economy standards, which also serve to limit the amount of fossil fuel burned on U.S. roads.

“There are a lot of alternatives that are still on the table,” says Steven Cohen, a professor at Columbia University and former executive director of the school’s Earth Institute.

The decision “is very unfortunate and it’s clearly an expression of extreme right-wing ideology, but I don’t think it prevents all forms of climate policy,” he adds.

A doctrine creates new uncertainty

The West Virginia v. EPA decision is nevertheless a landmark one in the context of the major questions doctrine.

The doctrine is relatively new – one of Chief Justice Roberts’ oldest citations on it is from 2000 – and holds that federal agencies should have strict limits on their ability to issue regulations of “major importance” unless Congress clearly delegates that authority to the agency.

And the high court has turned to it on a few occasions recently. Last fall, in a short per curiam opinion, the court struck down the Center for Disease Control’s eviction moratorium. And in January, in another per curiam opinion, the court struck down the Department of Labor’s COVID-19 vaccine and testing mandate for most U.S. employers.

Those cases, among others, are examples of “extraordinary cases” about agency regulations of such “economic and political significance” that it “provides a ‘reason to hesitate before concluding that Congress’ meant to confer such authority,” wrote Chief Justice Roberts in his majority opinion.

The Clean Power Plan was another such case, he said, because it had the significant economic effect of shifting how the country’s electrical grid generates power; because Congress had already considered and declined to implement similar policies, like an emissions-trading market; and because the Clean Air Act wasn’t designed to address climate change, among other reasons.

The doctrine works “to protect the Constitution’s separation of powers,” wrote Justice Gorsuch. Without it, agencies could implement regulations as de facto new laws “more or less at a whim.”

“Stability would be lost, with vast numbers of laws changing with every new presidential administration,” he added. “Rather than embody a wide social consensus and input from minority voices, laws would more often bear the support only of the party currently in power.”

But critics say that what the major questions doctrine is really doing, in effect, is assuming that lawmaking power for itself.

“There wasn’t much precedent to follow” on the doctrine, says Hajin Kim, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School.

But now, there doesn’t seem to be much restraining the court from ruling that a regulation it doesn’t like is a “major question” that must be struck down, she adds.

“It just gives them more discretion and power,” she continues. The doctrine “is an enormous power grab by the judiciary under the guise of separation of powers.”

Justice Kagan made a similar argument in her dissent. The court “has never even used the term ‘major questions doctrine’ before,” she wrote. (Justice Gorsuch did use the phrase in a concurrence to the vaccine mandate opinion.)

“Some years ago, I remarked that ‘[w]e’re all textualists now.’ ... It seems I was wrong,” she added. “The current Court is textualist only when being so suits it. When that method would frustrate broader goals, special canons like the ‘major questions doctrine’ magically appear.”

“Whatever else this Court may know about, it does not have a clue about how to address climate change,” Justice Kagan wrote. “The Court appoints itself – instead of Congress or the expert agency – the decisionmaker on climate policy. I cannot think of many things more frightening.”

Reducing the power of executive branch agencies has long been a goal of the conservative legal movement. There’s no question that it will now be harder for the EPA to implement emissions regulations. Whether the Supreme Court will choose to use its major questions power in other areas remains to be seen.

“The broader effect is to disempower all agencies, any agency, from acting on an important problem if Congress hasn’t clearly authorized the agency to do that,” says Lisa Heinzerling, a professor at the Georgetown University Law Center and lead author of the winning briefs in Massachusetts v. EPA, the 2009 ruling that said EPA can regulate greenhouse gases.

If you’re an agency crafting a major regulation, and “you think [Justice] Brett Kavanaugh, John Roberts, [or] Neil Gorsuch is going to raise his eyebrows at what you’re doing, you might pull your punches regulation-wise,” she adds.

“If that sounds subjective, it is.”

Patterns

Democracy’s challenge: Keeping judges independent and credible

Without the rule of law, democracy is a dead letter. Protecting courts from political pressure is a key path to protecting judicial independence and credibility.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Four simple words are critical to any functioning democracy: the rule of law.

But now, this lofty principle is facing a formidable real-world test: weathering the fractious partisanship of our 21st-century politics.

In the United States, the Supreme Court has removed women’s constitutional right to abortion. In Europe and Latin America, courts are under growing pressure from politicians.

At stake is the judiciary’s ability to remain independent, above the partisan fray, as well as its credibility and legitimacy.

All have been brought into question in Washington. Partly because the court that overturned Roe v. Wade last week contained three judges installed by former President Donald Trump expressly for that purpose. Also because the ruling ran counter to majority popular opinion, at a time when confidence in the highest court in the land has plummeted to 25%.

In the United States and elsewhere, the judiciary can only be insulated from political storms if political leaders across partisan divides decide that this is in their shared national interest. They will have to look beyond the day-to-day political battleground and meet on a patch of political territory that has been shrinking fast – the middle ground.

Democracy’s challenge: Keeping judges independent and credible

Four simple words are critical to any functioning democracy: the rule of law.

But now, this lofty principle is facing a formidable real-world test: weathering the fractious partisanship of our 21st-century politics.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s sudden removal of women’s half-century-old constitutional right to abortion is just the latest sign. A similar controversy has been brewing across the Atlantic, in Poland. In other populist-ruled democracies – including Europe’s oldest, Britain, and Latin America’s largest, Brazil – the courts are also under growing political pressure.

At stake are the twin pillars of the judiciary’s role as guarantor of the rule of law.

The first is its independence – the judiciary’s ability to remain above the fray of partisan politics.

The second pillar – and this may matter even more in today’s political environment – is popular trust in the credibility and perceived legitimacy of the highest courts’ decisions.

The controversy over abortion rights has brought both into question.

Firstly, because the Supreme Court that last week annulled the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision contained three judges whom former President Donald Trump had installed with the overt political aim of overturning the earlier decision.

Secondly, because the court’s abortion ruling ran counter to the views of a clear majority of Americans.

And it came at a time when popular trust in the court has been plummeting. A poll this month – following a leaked early version of the abortion ruling – found a record low of 25% of Americans had confidence in the highest court in their land.

Poland’s constitutional court – reconfigured as part of a purge of judges by the ruling, right-wing Law and Justice Party – has also mandated a near-total ban on abortion. And there, too, polls suggest most people favor a liberalization of abortion laws.

Still, as judges, lawyers, and concerned politicians look for ways to reinvigorate the judiciary’s independence and credibility, they may take some heart from the fact that judicial partisanship has been a perennial democratic challenge.

The “rule of law” is a matter not of pure philosophy. It’s applied by individual judges no more capable of perfect objectivity than politicians. Judges themselves are appointed by others with political views of their own.

And given the judiciary’s key institutional role – as a check on government power – a degree of tension is simply wired into the system.

Still, the question now is whether, amid the anger and extremism setting the political weather in many democracies, efforts to keep the rule of law intact will prove as successful as they once did.

In America, there’s a parallel from the mid-1930s, the early New Deal years of then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He was frustrated by a conservative Supreme Court that had struck down key parts of his ambitious economic recovery programs as an overreach of federal authority.

His response was a plan to “pack” the court with New Deal-friendly justices to tilt its balance. Yet he was ultimately blocked by members of his own party, concerned about undermining the checks and balances put in place by the framers of the Constitution.

And then-Chief Justice Charles Evan Hughes also seemed to sense a wider rule-of-law peril in the standoff with Mr. Roosevelt, especially after the president had been reelected in a landslide. Chief Justice Hughes shifted the court away from its opposition to New Deal laws.

Interestingly, current Chief Justice John Roberts seems to harbor similar concerns on abortion. Though backing last week’s ruling, he made it clear he would have preferred it to have been more measured, stopping short of striking down Roe v. Wade outright.

At least for now, the court’s direction is being set by the new Trump-appointed judges.

In the United States and other democracies where the judiciary is increasingly politicized, there is now a growing focus on the potential longer-term consequences of eroding the top courts’ independence and credibility.

In Poland, judges and lawyers have been making that case at home and abroad. The European Union’s top court has ruled against the government’s moves to ensure politically friendly judges, and the EU has withheld some funding to Warsaw, yet so far without major effect.

In Britain, where the government of Boris Johnson has publicly criticized judges after a series of court rulings against its actions, a cross-party parliamentary committee this month publicly expressed its concern about those criticisms’ potentially chilling effect on judicial independence.

Leading Brazilian judges and lawyers, alarmed over President Jair Bolsonaro’s attacks on the judiciary, have petitioned the United Nations for support, concerned that he is laying the ground to reject the result of this fall’s presidential election if he loses.

Ultimately, however, any effective move to re-insulate the judiciary from political storms is going to require leaders across partisan divides to decide that’s in their shared national interest to do so – and that the alternative risks fundamentally damage their democracies.

They’ll have to look beyond the day-to-day political battleground, as President Roosevelt and Chief Justice Hughes did nearly a century ago.

And they will have to meet on a patch of political territory that has been shrinking fast – the middle ground.

The Explainer

Heat waves: How to cope with new extremes

Heat waves are getting hotter, longer, and more frequent around the world. Here’s what communities are doing to beat back the heat and protect public health – including for the most vulnerable populations.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Temperatures broke June records around the globe, from the leafy streets of the American South to the domes of the Vatican. Japan recently had its first-ever 104-degree June day. A port city in Iran has sweltered for days under 122-degree heat. It was even hot above the Arctic Circle, where thermometers in the Russian city of Norilsk pushed to record highs grazing 90 degrees.

Generally, a heat wave is when abnormally high heat lingers for two or more days. It’s not just a matter of how hot it is, but also of how unusual that temperature is. Even in a state like Nevada that’s used to triple-digit summers, stretches when it’s 115 degrees can cause distress.

People who spend their days outdoors or lack access to air conditioning – for instance, day laborers or homeless people – are increasingly vulnerable.

Solutions in the United States and around the world include steps like planting more urban trees for shade and painting rooftops white to reflect heat. Cooling stations at places like libraries and community centers provide vital shelter. Some U.S. cities have chief heat officers, or are improving outreach to non-English speakers, to expand awareness of heat warnings and resources.

Heat waves: How to cope with new extremes

It’s hot out there, and it’s getting hotter.

Temperatures broke June records around the globe, from the leafy streets of the American South to the domes of the Vatican. Japan recently had its first-ever 104-degree June day. Cities across Iran have sweltered for days under 122-degree heat. It was even hot above the Arctic Circle, where thermometers in the Russian city of Norilsk pushed to record highs grazing 90 degrees.

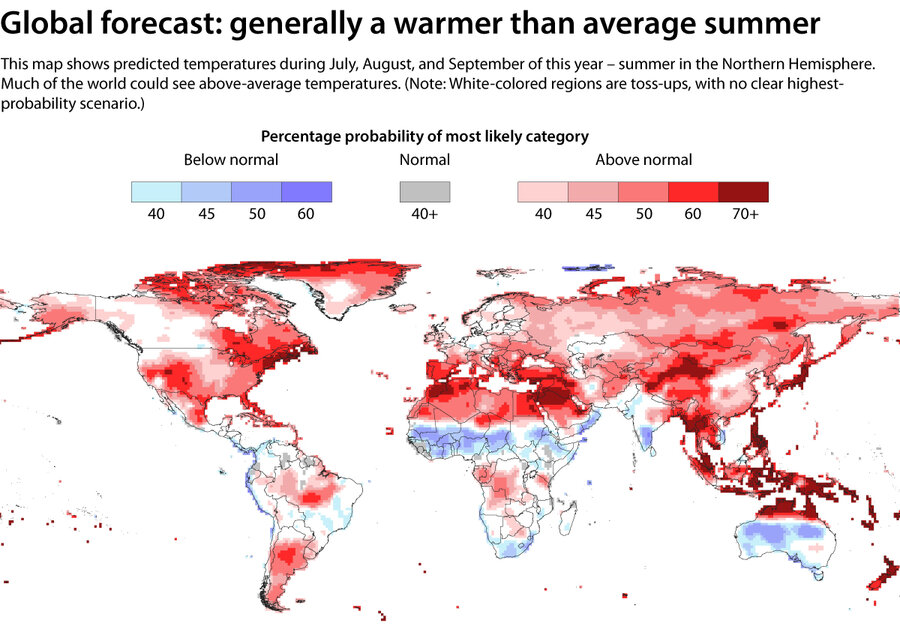

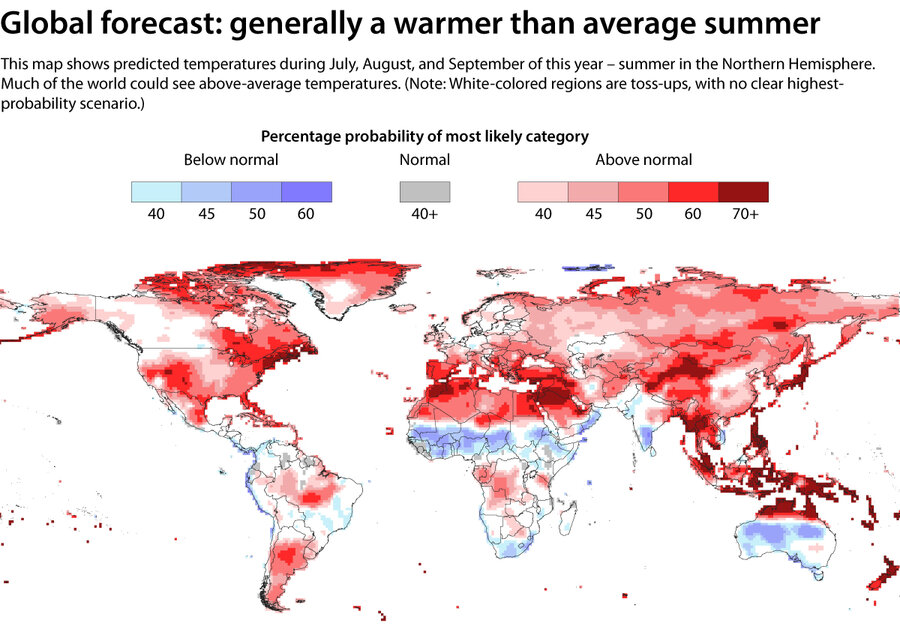

In the U.S., states across New England and the Mountain West are in for unusually high heat through the end of the summer, according to an analysis by the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center.

These waves of extreme heat pose serious public health challenges. A heat wave that began a year ago this week in the Pacific Northwest contributed to hundreds of deaths. And the World Health Organization attributes 166,000 deaths globally to heat waves over a period stretching from 1998 to 2017.

Modern comforts like air conditioning have mitigated heat’s direst effects. For the last 50 years, for example, heat-related deaths in the United States have generally been declining, according to a 2021 study. But the same study cautions that, in the last decade or so, the decline has slowed, and possibly even started to reverse.

With heat waves growing longer, hotter, and more frequent, scientists and officials are exploring ways to keep people safe.

International Research Institute for Climate and Society

What counts as a heat wave?

There’s no single definition, but generally a heat wave is when abnormally high heat lingers for two or more days. It’s not just a matter of how hot it is, but also of how unusual that temperature is. Even in a state like Nevada that’s used to triple-digit summers, stretches when it’s 115 degrees can cause distress.

Consecutive days of extreme heat, when overnight temperatures stay high, exacerbate vulnerabilities. “The most dangerous part,” says P. Grady Dixon, a professor at Fort Hays State University and author of that 2021 study, “is the lack of cooling off.”

Who’s most vulnerable to extreme heat?

Historically, older adults have been most at risk. However, over the past few decades, they’ve benefited greatly from the spread of air conditioning and more effective messaging to deliver heat warnings. According to Dr. Dixon, their safety has helped improve U.S. health statistics related to heat’s dangers.

But not everyone can take advantage of AC. For instance, homeless people or day laborers who spend their days outdoors are increasingly vulnerable to extreme heat.

Urban landscapes can also worsen heat. Asphalt streets, tightly packed buildings, lack of green space, and gas-powered engines create so-called urban heat islands. This is evident in Boston, where a 2019 city study found the Chinatown neighborhood, which is downtown, was up to 12 degrees hotter than leafier suburbs.

How do we keep people safe?

The simplest and most important step toward safety is knowing when there’s a risk.

“When the weather forecast [on your phone] is a smiley face or a rain cloud, that’s not good enough,” Dr. Dixon urges. “Seek out the National Weather Service and heed their heat warnings.”

Kimberly McMahon, a program manager at the National Weather Service, says the agency is working to develop even better warning tools that can single out what is dangerous for specific areas or populations.

Another priority is making sure those messages reach everyone who needs them – including non-English speakers and people who spend their days working outdoors.

“We’ve done video PSAs in English and Spanish. Radio in English, Spanish, and Creole. Billboards at bus stops, particularly targeting the ZIP codes with the highest severe heat,” says Jane Gilbert, a Miami official.

Ms. Gilbert is herself an example of how cities are pushing to mitigate heat. She’s Miami-Dade County’s chief heat officer, a position created to coordinate efforts to cool cities. Ms. Gilbert was the first, appointed in June 2021, and Phoenix and Los Angeles have each appointed ones since.

Another step toward safety is to keep vulnerable people out of harm’s way.

Erick Bandala of Nevada’s Desert Research Institute says places “need stricter regulations [to protect] workers who have no choice but to go out there and work even on a 110, 115 [degree day].”

Communities across the country have opened cooling stations: libraries, community centers, senior centers, and other spots open to anyone who needs shelter from the dangerously hot outdoors.

Cities are making more permanent transformations as well. Since 2009, New York City has repainted tens of thousands of dark rooftops white to stop them from absorbing so much heat. And Los Angeles has begun covering its endless asphalt streets with a reflective coating.

Meanwhile, nearly every city is striving to plant more trees, which offer much-needed shade. “We’re giving away over 10,000 trees this summer,” says Ms. Gilbert, continuing local initiatives that have planted more than 218,000 trees since 2001.

In some ways, the U.S. is playing catch-up with places like Singapore that have long committed to tackling heat. The equatorial country has central cooling systems, rooftop gardens, and greenery that scales the sides of tall buildings.

Kathy Baughman McLeod, director of the Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center at the Atlantic Council in Washington, sees hope in her work promoting heat mitigation efforts around the world.

“There are a lot of aspects of climate change that feel intractable,” she says, “but this is not one of them.”

International Research Institute for Climate and Society

Seeking safety: Muslims move to Delhi ‘ghettos’ amid demolition

For Indian Muslims, what makes a space safe? Amid escalating violence and recent demolition drives, many are seeking security in Delhi’s majority-Muslim enclaves. But ghettoization comes with risks.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Tarushi Aswani Contributor

Last year, Imaad Hassan moved out of the posh, Hindu-dominated Sarita Vihar neighborhood in New Delhi to Abul Fazal Enclave – a Muslim-majority area that’s long struggled with poor water and electricity access.

“I moved from a gated society to a ghetto for my own safety,” he says.

Reports of hate crimes against religious minorities have spiked since the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party came to power. In recent months, authorities have bulldozed Muslim homes, mosques, and shops, often under the guise of anti-encroachment drives.

The normalization of Hindu nationalism and anti-Muslim violence has many Delhi residents seeking refuge in the city’s Muslim enclaves, which are broadly stigmatized as lawless or unclean, but offer a relatively safe space to express their religious identity. Although the government isn’t explicitly forcing Muslims to live in these areas today, they’re widely referred to as “ghettos” due to the challenges residents face and the pressures Muslims experience to settle there.

But Nazima Parveen, author of “Contested Homelands: Politics of Space and Identity,” worries that in the long term, this segregation will only help Hindu nationalism grow. “Hindus also won’t be willing to live in areas dominated by Muslims, just like Muslims look for areas dominated by their own kind,” she says. “Such developments will have a very dangerous impact on social fabric.”

Seeking safety: Muslims move to Delhi ‘ghettos’ amid demolition

Eight months ago, Imaad Hassan moved out of the posh, Hindu-dominated Sarita Vihar neighborhood in New Delhi to Abul Fazal Enclave – a riverside area that’s long struggled with poor water and electricity access.

“I moved from a gated society to a ghetto for my own safety,” he says. “Every time the news carried events of Hindu-Muslim clashes, my neighbors would stop responding to my greetings. Only Allah knows what would’ve happened had I continued to stay there.”

Reports of hate crimes against religious minorities have spiked since Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party came to power in 2014. At the same time, BJP leaders have advanced new laws and policies that restrict interreligious marriages and Muslim immigration. And in recent months, bulldozers have become a symbol of Hindu nationalist groups as authorities raze Muslim homes, mosques, and shops under the guise of anti-encroachment drives, government campaigns that purport to demolish illegal or unauthorized buildings.

Amid all this, many Delhi residents are leaving mixed-population areas for the city’s Muslim enclaves, which often lack basic amenities and are broadly stigmatized as lawless or unclean. Experts say that Hindutva – an ideology that promotes Hindu hegemony – has become so mainstream that Muslims are forced to choose between expressing their religious identity and their safety.

With regard to Hindutva groups, “their constant messaging [is] that this is our country,” says Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, a journalist who’s written several books on Indian politics. “Muslims can stay here, but as long as they’re invisible. You don’t offer namaz [prayers] on roads, you don’t wear the hijab, just be invisible.”

The short-term refuge offered by Muslim-majority areas comes at a cost, experts warn, but Mr. Hassan says the trade-offs are worth it. “I don’t have to fear being a Muslim in a ghetto,” he says. “I don’t have to worry about being socially boycotted.”

The rise of Delhi’s ghettos

Delhi’s Muslim enclaves have a long history, with many dating back to Partition or to a 1970s “urban beautification” drive, and they have always carried stigma – though the nature of that stigma has evolved over time, according to Nazima Parveen, independent researcher and author of “Contested Homelands: Politics of Space and Identity.” First, they were seen as zones where the government could contain and protect the Muslim population, then as unhygienic and culturally backward slums, and later as terrorist hideouts.

Although the government isn’t explicitly forcing Muslims to live in these areas today, they’re widely referred to as “ghettos” due to the stigmas and challenges residents face, as well as the pressures Muslims experience to settle there. Landlords in Hindu-majority areas, for example, aren’t always willing to rent to Muslim families.

Dr. Parveen worries that this continued segregation – whether forced or voluntary – will inevitably help Hindu nationalism grow. “Hindus also won’t be willing to live in areas dominated by Muslims, just like Muslims look for areas dominated by their own kind,” she says. “Such developments will have a very dangerous impact on social fabric.”

The ghettoization of Muslims also makes their communities more vulnerable to physical, targeted attacks, as seen in recent demolition drives.

In April, Jahangirpuri resident Mohammed Haseeb witnessed authorities demolish the front gate and wall of a local mosque. A Hindu temple located about 300 feet away was spared. It was one of several recent anti-encroachment drives in the area, which typically follow Muslim-Hindu clashes.

“In ghettos, they come and bulldoze our homes and shops. Outside ghettos, they harass Muslims for simply existing,” he says. “My skullcap, my beard, and even my name attract angry stares.”

Strength in numbers

Rizwan Ansari moved to Shaheen Bagh, a Muslim enclave, in 2018, after living in a Hindu-dominated locality in southwestern Delhi for nine years.

“I don’t dress Islamically, so I could manage somehow, but my wife is a practicing Muslim who wears the hijab. It would be difficult for her to be safe in a Hindu-majority area,” he explains. “Every day there is a new hate crime against Muslims. Every day we learn how much we are being hated in our own country.”

The couple’s life in Shaheen Bagh hasn’t been entirely peaceful, though. As in Jahangirpuri, a bulldozer pulled into a busy Shaheen Bagh street shortly before noon on May 9. But unlike in the April incident, this bulldozer retreated after hundreds of residents and opposition party members surrounded the vehicle and blocked it from its target.

This isn’t the first time the neighborhood became the nerve center of protests against anti-Muslim discrimination. Critics believe the attempted demolition in May was retribution for a series of demonstrations in 2019 and 2020, when Shaheen Bagh residents demanded the withdrawal of the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act, which created a path to citizenship for non-Muslims fleeing neighboring countries.

Mr. Ansari says that despite this chaos, living where Muslims are in the majority brings a sense of security. “Even if anti-Muslim groups attack, we would surely have our own community to stick by us,” he says.

In a nearby neighborhood called Batla House, mechanical engineer Sanaullah Akbar sees ghettos as spaces where Muslims can live without fear, even if these areas lack infrastructure or attract hostility.

And he feels he isn’t alone – Mr. Akbar says that the population in surrounding ghettos seems to have doubled in recent years.

“We will definitely witness new Muslim ghettos coming up,” he says. “I myself would always choose a dilapidated Muslim ghetto rather than living in an affluent, Muslim-minority area.”

Film

Leonard Cohen’s journey culminates in ‘Hallelujah’

Leonard Cohen spent seven years perfecting his most celebrated song, “Hallelujah.” A new documentary uses the birth of that piece to lay out the musician’s spirituality – and hope.

-

By Peter Rainer Contributor

Leonard Cohen’s journey culminates in ‘Hallelujah’

I’m usually dubious whenever a singer-songwriter is characterized as some kind of spiritual seeker. But if ever there was someone who deserved that description, it’s Leonard Cohen. The new documentary “Hallelujah: Leonard Cohen, a Journey, a Song” amply demonstrates, through multiple interviews and archival material spanning decades, just how deeply personal, oftentimes almost sacramental, his music-making could be. As the record executive Clive Davis says in the film, “No one walked in his path. He didn’t walk in anybody else’s path.”

Rather than structure their movie as a chronological biography, the co-directors, Daniel Geller and Dayna Goldfine, wisely focus on the genesis of Cohen’s most celebrated and performed song, “Hallelujah.” This approach allows them to interweave Cohen’s entire career while also avoiding the one-thing-after-another sprawl that often bogs down these kinds of films.

How did Cohen come to write “Hallelujah”? Not quickly. It took him seven years, and hundreds of drafts of alternate lyrics, before he unveiled the song in 1984. By pop-rock standards, Cohen, who died in 2016 at age 82, was always a late bloomer. Born into an Orthodox Jewish family in Montreal, he began his career as a renowned poet and novelist and didn’t compose or perform music until he was in his early 30s. “Hallelujah” was included – on Side B! – in his 1984 album “Various Positions,” but record executives were so dismissive of the disc that they only released it outside the United States. (It was subsequently picked up without fanfare by a small independent label.) Walter Yetnikoff, then-president of CBS Records, told Cohen, “We know you’re great, but we don’t know if you’re any good.”

It was only in 1991, when Velvet Underground co-founder John Cale performed a version of “Hallelujah,” drawing on some of Cohen’s alternate lyrics, that the song gained traction. Three years later, in a plaintive performance best described as angelic, Jeff Buckley recorded it for his “Grace” album. Bob Dylan covered it. And then, in 2001, it was featured in, of all things, “Shrek,” with Cale’s version on the soundtrack. (The double platinum movie album featured Rufus Wainwright instead.) The song has subsequently been covered innumerable times – my favorite is k.d. lang’s powerhouse rendition, briefly excerpted in the movie – and it’s become a mainstay at weddings, and, alas, on “American Idol” and “The Voice.”

Despite all this exposure, it’s never been entirely clear what the song, with its mix of the spiritual and the secular, actually means. It’s a resonant riddle. Cohen speaks directly to God in it and also to his own deepest desires, referencing everything from his own lost loves to David and Bathsheba. But perhaps this is a song that doesn’t gain with explication. Cohen refused to spell things out. He says in the film, “If I knew where songs come from, I’d go there more often.” Heard in a live concert, the chorus of “Hallelujah!” that periodically surfaces is so overpowering that clearly it touches audiences of every faith, or none. As the singer Regina Spektor says, “You get this feeling of hearing a modern prayer.”

You certainly get that feeling watching Cohen perform the song in front of an audience, especially in the concert clip we see near the end of his life. He looks to be in a state of rapt contemplation. But he can also be raspy and insinuating, beseeching, doomy yet rife with hope. He’s working out his feelings about the mystery of life, right there in front of us.

Cohen was a voluminously complicated man, but he must have felt, on some private level, that this song was his apotheosis. As the film concludes, he offers up, if such a thing is possible, a kind of summation. He says, “You look around and you see a world that is impenetrable, that cannot be made sense of. You either raise your fist or you say ‘Hallelujah.’ I try to do both.”

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “Hallelujah” is available in some cities starting July 1. The film is rated PG-13 for brief strong language and some sexual material.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Mending a hole in Asia’s security

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Japan and South Korea are only a ferry ride away from each other. Their democracies are as strong as ever. Yet their diplomatic ties have been cold for years over historical and legal disputes – that is, until this week. At a NATO meeting, the heads of each country hinted at putting the future over the past.

The two leaders, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol, met briefly at a dinner and then joined U.S. President Joe Biden for a trilateral summit – the first such gathering in five years. The United States needs two of its closest allies in Asia to get along. With an eye toward rising threats from Russia, China, and North Korea, both Japan and South Korea now seem inclined.

For his part, Mr. Yoon suggested that democracies must work together to protect “universal values” that some countries deny. His Japanese counterpart said cooperation has never been more vital because of threats to the rule-based international order.

The two Northeast Asian neighbors certainly know they have shared threats. To overcome their respective deep resentments, their leaders may now be looking for a common tool of reconciliation: shared values.

Mending a hole in Asia’s security

Japan and South Korea are only a ferry ride away from each other. Their economies are among the world’s largest. Their democracies and their cultural ties are as strong as ever. Yet their diplomatic ties have been cold for years over historical and legal disputes – that is, until this week. At a NATO meeting in Spain, the heads of each country hinted at putting the future over the past.

The two leaders, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol, met briefly at a dinner and then joined U.S. President Joe Biden for a trilateral summit – the first such gathering in five years. The United States needs two of its closest allies in Asia to get along. With an eye toward rising threats from Russia, China, and North Korea, both Japan and South Korea now seem inclined.

For his part, Mr. Yoon suggested that democracies must work together to protect “universal values” that some countries deny. His Japanese counterpart said cooperation has never been more vital because of threats to the rule-based international order.

Once Japan holds a parliamentary election in July, the two leaders could possibly meet in a one-on-one summit. And in August, both countries will join the U.S. in holding naval exercises off Hawaii to improve their surveillance of North Korea.

“I am convinced that Prime Minister Kishida can become a partner who can solve issues between Korea and Japan,” said Mr. Yoon after their meeting.

Resolving the thicket of issues left over from Japan’s 1910-1945 colonial rule of the Korean Peninsula will not be easy. One compromise, however, may be in the works. Reports in South Korea indicate the two sides are discussing a face-saving way to compensate former Korean wartime laborers with private money. For its part, Japan expects South Korea to abide by a 1965 treaty that normalized bilateral relations and included compensatory grants and loans.

Helping Japan and South Korea to reconcile is one of Mr. Biden’s top 10 priorities for the Asia-Pacific region. The two Northeast Asian neighbors certainly know they have shared threats – from a bullying China and a North Korea on the verge of another nuclear test. To overcome their respective deep resentments, their leaders may now be looking for a common tool of reconciliation: shared values in need of safekeeping.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Reflective self-examination that frees

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Suzanne Riedel

Taking an honest look at how we might improve ourselves can be unnerving. But starting from the basis of our nature as God’s children dissolves self-condemnation that can hinder progress and opens the door to hope and healing.

Reflective self-examination that frees

Who likes to have their merits as an employee, a teacher, or even just a human being examined – with the expectation that you must then address your failings, with uncertain results? Even if it’s a self-examination, free from the criticisms of others, anticipating a multitude of inescapable human weaknesses can feel like a prison sentence.

But what if self-examination actually doesn’t need to be a downer at all, but an unlocking of hidden assets?

When I was introduced to Christian Science and began to read the writings of Mary Baker Eddy, its founder, I saw that self-examination was encouraged as a necessary thing to do to stay centered and make progress in our lives. In “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mrs. Eddy wrote, “Are thoughts divine or human? That is the important question” (p. 462). Such awareness impels examining one’s thoughts to identify their source and progression.

The trouble is, it can be hard to see our present standpoint in a way that enables growth instead of embarrassment that more progress hasn’t been made. We may start defining ourselves and others as molded by human circumstances and limitations. This approach to self-examination can bring negatives that are counterproductive, at best.

So what is the lens that actually supports positive growth? The point of view that transforms must encourage instead of condemn. I have found that this is most effectively done not simply by focusing on what needs to change humanly, but by welcoming divine thoughts, which reveal that our Father-Mother God created each of us spiritual, whole, and upright.

This leads to an awareness of needed improvements in character and behavior. To live more compassionately, humbly, mercifully, as Jesus taught and lived, necessarily requires a willingness to examine ourselves and recognize what doesn’t fit with the Christly spiritual nature that is innately ours as God’s children. But at the same time, we can be encouraged that we have a God-given ability to drop old ways of thinking and acting that simply aren’t seen through the lens of Spirit, God.

I remember an early experience along these lines that drew me consciously closer to God. As a young mother fairly new to the study of Christian Science, I was experiencing healings, but I also had a lot of mental and emotional baggage that needed to go. I was self-examining often.

But at first, I wasn’t starting by identifying myself as the spiritual likeness of Love, a biblical name for God. I was identifying with problems – which seemed to be how others were defining me, as well. Hopelessness and self-condemnation were the outcomes – not the joyful progress that I was coming to learn is what our infinitely loving Father-Mother God has planned for His children.

Then I spoke with a Christian Science practitioner – a person who has dedicated her or his life to praying for others – and unloaded my problems. What I hoped for was a lifting of the heaviness and lack of joy. But I wasn’t grasping her comments and felt a sense of hopelessness settling in. As I was leaving, sensing the heaviness I longed to be lifted, the practitioner tenderly made this parting comment: “Don’t you realize that you are given a clean slate every day?”

Frankly, I was blown away. In that moment I saw that divine Love never keeps score of mistakes and failures. A personal sense of self-examination had not allowed me to look out and up, but only inward to perceived ineptness. That moment of being touched by Love’s always-present embrace enabled me to feel the truth of what I had read in Science and Health, that I was “free ‘to enter into the holiest,’ – the realm of God” (p. 481). I felt I was seeing through a new lens, a lens that showed a glimpse of the spiritual reality that we live because of God’s good will, not our own.

It tangibly changed my life at that time, and has stayed with me since. It has impacted ongoing self-examination that has led to humble, deep gratitude; multiple healings of physical problems; overcoming relationship challenges; resolving financial affairs; and finding guidance for what steps to take next in my life.

It is true: God doesn’t keep score of the mistakes and failures of human experience. In fact, the infinite Mind that loves each of us knows our strengths, talents, and divinely created promise. Ever-present divine Mind has given us the capacity to see through the spiritual lens that opens up uncompromised, inexhaustible progress. Self-examination then becomes a putting down of baggage that never belonged to God’s child in the first place – and living as the expansive expression of God, divine Mind, Love, we are created to be.

A message of love

Welcome, Justice Jackson

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow we’ll have the final installment of our Education and Democracy series with an article on parental participation in schools. You can find the first three articles in the series here:

Part 2: How should schools teach children what it means to be an American?