- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 11 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

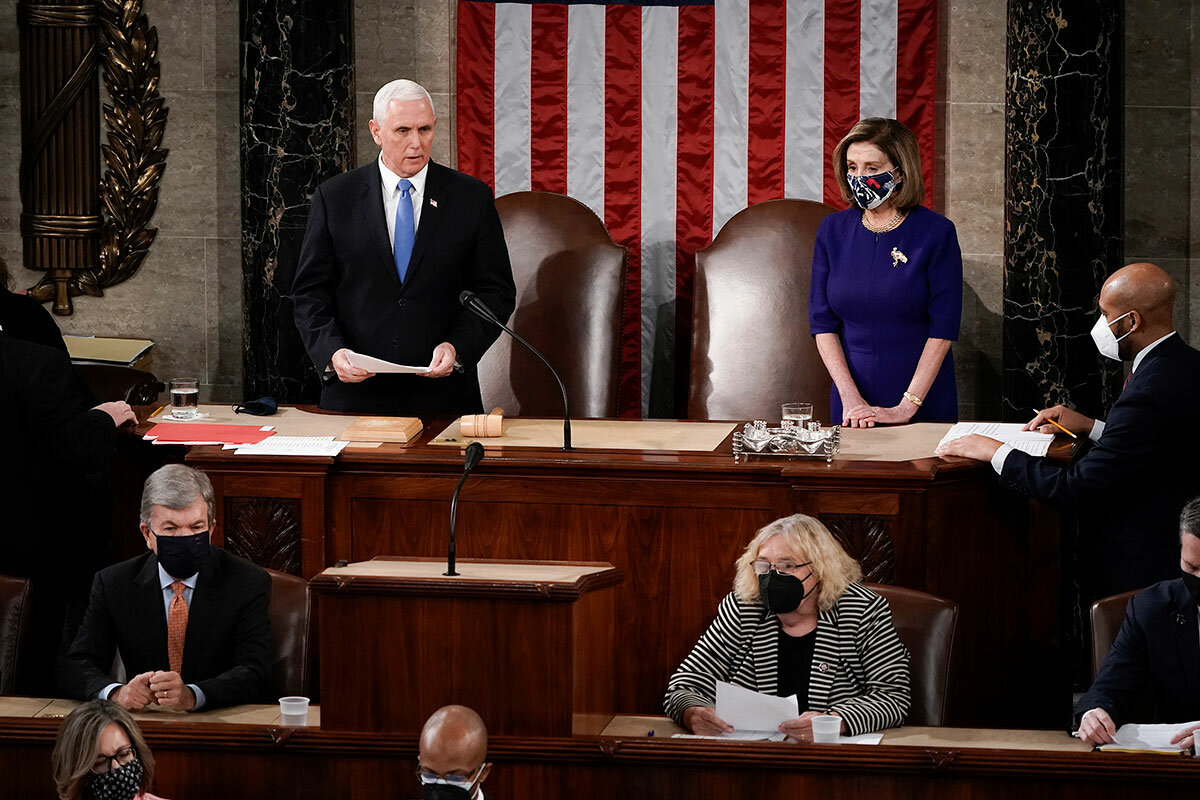

- In Jan. 6 spotlight, Mike Pence navigates a tricky post-Trump path

- Biden in Israel: A meeting of the (moderate) minds?

- Even loyalists are targets in latest Russian crackdown. Why?

- After Roe, many questions: Where the legal fight moves next

- Need a summer escape? Try Maine, East Germany, occupied France.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How ordinary people become extraordinary heroes

In an emergency situation, why do some people instinctively risk their own lives to try to save others?

I pondered that question when I read an Associated Press story about the everyday heroes at the mass shooting at a July Fourth parade in Highland Park, Illinois.

When a sniper opened fire, killing seven people and wounding 46 others, some people ran toward the gunfire to help. Bystander Bobby Shapiro was taking off his cycling shoes when he heard the shots. Wearing just socks, Mr. Shapiro assisted Dr. Wendy Rush, an anesthesiologist who’d been attending the parade, tend to the victims. Their compassionate instincts superseded their fear. “We didn’t know where the shooter was,” said Dr. Rush. “We knew he wasn’t dead.”

According to the 2008 study “The Hero Concept,” everyday heroes seem to share certain values. They tend to have a robust sense of social responsibility and empathy for others. Another common trait: They’re often hopeful by nature. That optimism enables them to view difficult situations as challenges that can be changed for a better outcome.

Some believe that heroism can be nurtured. Dr. Julie Hupp, an associate professor of psychology at the Ohio State University at Newark and one of the study co-authors, told The Wall Street Journal, “Children who grew up watching their parents stick their necks out for others, are likely to do the same.”

Indeed, a nonprofit called The Heroic Imagination Project aims to inculcate heroism in adolescents. Its courses teach students the importance of moral courage and how to practice everyday altruism.

“Anyone can be a hero at any time an opportunity arises to stand up for what is right and just,” according to Dr. Philip Zimbardo, a Stanford University psychologist who founded the project. “Heroism can be learned, can be taught, can be modeled, and can be a quality of being to which we all should aspire.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

In Jan. 6 spotlight, Mike Pence navigates a tricky post-Trump path

Credited with averting a constitutional crisis, the former vice president faces the ire of Trump allies. But for a No. 2 perpetually in his boss’s shadow, it could turn out to be the opening Mr. Pence needed.

Mike Pence’s emergence as one of the heroes of the Jan. 6 hearings has placed him in a singular political position. Spurned by former President Donald Trump as a turncoat, even as Democrats hail him as a savior of democracy, Mr. Pence is laying the groundwork for a 2024 White House run that could pit him against his former boss.

Mr. Pence has been touting his administration’s policy achievements and has refrained from criticizing Mr. Trump. But his evangelical faith goes hand in hand with an emphasis on decency and decorum that contrasts with Mr. Trump’s performative pugilism.

Beneath the Midwestern humility is a deeply conservative policy agenda. After the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, Mr. Pence called for a nationwide abortion ban.

If he can build a coalition of religious conservatives, Trump-weary Republicans, and just enough MAGA devotees who don’t hold Jan. 6 against him, it could be enough to emerge from a crowded field. He could also wind up as a consensus candidate, to whom the party turns if flashier front-runners flame out – not unlike Joe Biden in 2020.

“Mike’s greatest advantage is that people underestimate him,” says John Gregg, an Indiana Democrat who lost a 2012 gubernatorial race to Mr. Pence.

In Jan. 6 spotlight, Mike Pence navigates a tricky post-Trump path

It was a pivotal moment for the vice president – and the nation. Pro-Trump rioters were rampaging through the Capitol building yelling “Hang Mike Pence,” as Mr. Pence and his family huddled in an underground parking bay. But when a Secret Service agent asked him to get into a waiting car, he refused.

“He was determined that we would complete the work that we had begun that day,” Mr. Pence’s legal counsel, Greg Jacob, told the House committee investigating the Jan. 6, 2021, attack.

That work, of course, was the certification of Joe Biden as the next president.

Mr. Pence’s emergence as one of the heroes of the Jan. 6 hearings – which detailed how he resisted an intense pressure campaign by former President Donald Trump to get him to block the counting of electoral votes – has placed him in a singular political position. After four years of loyal service, he’s now spurned by Trump allies as a turncoat, even as Democrats and some former Trump aides see him as a savior of democracy. During Tuesday’s hearing, Trump White House attorney Pat Cipollone testified that Mr. Pence had done the “courageous thing” and deserved a Presidential Medal of Honor.

As the jockeying for 2024 heats up, with Mr. Trump rumored to be nearing a formal announcement, Mr. Pence is laying the groundwork for a run that could pit him against his former boss.

At best, he faces a difficult balancing act. The former vice president, who was booed at a gathering of conservative activists last year, has been touting the Trump administration’s policy achievements and has refrained from criticizing Mr. Trump – even after the Jan. 6 hearings revealed the president’s lack of concern for his safety.

Yet for a vice president who was perpetually in Mr. Trump’s shadow and never seemed destined to inherit the MAGA mantle, it’s also possible Jan. 6 has given Mr. Pence the opening he needed.

In some ways, the former Indiana governor represents a throwback to the GOP of old, before Mr. Trump jettisoned much of its post-Reagan orthodoxy and norms of governance. Beneath the Midwestern humility is a deeply conservative policy agenda, undergirded by close ties to Charles Koch and other GOP donors. After the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, Mr. Pence pointedly called for a nationwide abortion ban. Next week, he’s heading to South Carolina, a key early primary state, to give a talk about “the post-Roe world.”

Mr. Pence’s evangelical faith also goes hand in hand with an emphasis on decency and decorum that contrasts sharply with Mr. Trump’s performative pugilism.

“He’s never made an enemy in his life – with one notable exception,” says one Indiana Republican, who asked for anonymity so he could talk freely.

If Mr. Pence can build a coalition of religious conservatives, Trump-weary Republicans, and just enough MAGA devotees who don’t hold Jan. 6 against him, it could be enough to emerge from a crowded field. It’s also conceivable he could wind up as a kind of consensus candidate, the elder statesman to whom the party turns if flashier front-runners flame out – not unlike Mr. Biden in 2020.

“Mike’s greatest advantage is that people underestimate him,” says John Gregg, an Indiana Democrat who lost a 2012 gubernatorial race to Mr. Pence. “He’s tireless, and he’s focused. I’ve never met anyone who stays on message more than Mike Pence.”

On the ground in New Hampshire

Despite Mr. Trump’s popularity among the base, polls and focus groups indicate that many Republican voters are open to or might even prefer a different candidate as their party’s nominee in 2024. As a result, an ever-growing number of would-be candidates are already testing the waters.

Those making the rounds in New Hampshire include Sens. Tom Cotton of Arkansas and Tim Scott of South Carolina, former Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley, and former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who leads the pack of Trump alternatives in early GOP primary polls, has so far stayed away.

In May, Mr. Pence spoke to a sold-out dinner at a New Hampshire winery, hosted by the Rockingham County GOP chapter. He extolled the Trump administration’s conservative record, including the appointment of three Supreme Court justices and 300 federal judges. It was, he boasted, “the most pro-life administration in American history.”

What went unsaid by Mr. Pence was what he did to usher out that administration on Jan. 6. Much of the GOP base is still upset by Mr. Trump’s defeat and not inclined to cut Mr. Pence any slack.

J. David Bernardy, a Republican state legislator who attended the dinner, concedes that Mr. Pence was constitutionally bound to certify the 2020 election results – but says allegations of fraud should have been investigated more fully. (Senior Trump administration officials, including former Attorney General Bill Barr, testified to the committee that they investigated and found no evidence of widespread fraud.)

The bigger issue, to Mr. Bernardy, is what he sees as Mr. Pence’s passivity. “The defining issue for me is strength against a virulent Democratic Party,” he says, arguing that Mr. Pence failed to stand up to public health officials when he ran the White House COVID-19 task force. Mr. Pence is “a very nice, soft-spoken, and genial guy,” he concludes, but he’s not the best choice to “counter the absolute horror going on in Washington now.”

Srinivasan Ravikumar, a retired engineer and another local GOP official, says he appreciates Mr. Pence’s temperate style and conservative values. But he’s unhappy that the vice president “rubber stamped” Mr. Biden’s electors. “I think he went into survival mode after the election, and that doesn’t strike me as right,” he says.

Such attitudes are common among GOP voters here, say party strategists. The vice president “always gets a respectful welcome” in New Hampshire, says Jerry Sickels, who worked for the Trump campaign in 2016. But Mr. Pence’s role on Jan. 6 will unquestionably hang over any presidential run. “It’s a hurdle for him to overcome with the rank and file, no question about that,” he says.

It’s possible lingering anger over the 2020 election will fade as Republicans start to look to 2024. And the blows to Mr. Trump’s credibility from the House committee hearings and his exposure to potential criminal charges could weaken him.

But even if some GOP voters are growing wary of another Trump campaign, they seem to be leaning toward Trump-like alternatives. A UNH Granite State Poll found Governor DeSantis statistically tied with Mr. Trump among likely Republican primary voters. These voters “have a basically positive attitude towards the former president,” says Dante Scala, a politics professor at the University of New Hampshire. But “they’re open to moving on.”

Mr. Pence trailed far behind in third place in the same poll, which was taken in June after the first televised Jan. 6 hearings. Of 13 potential candidates polled, he was the only one with a negative favorability rating. “For core Trump voters, he’s seen as a traitor,” Professor Scala says.

“I think he’s dead in the water. He may not realize it,” says Thomas Patterson, a professor of government at Harvard University.

From “Rush Limbaugh on decaf” to the vice presidency

Mike Pence never set out to make political enemies. Quite the opposite, says Mr. Gregg, who first met him at law school and has remained on cordial terms with him, even after their hard-fought campaign for governor.

When Mr. Pence became a conservative talk-radio host in the 1990s, he would regularly interview Mr. Gregg, then Democratic speaker of the Indiana House. Their policy debates were always respectful, he says. “There was never anyone more professional, kinder, and more appreciative,” he says.

Radio proved a perfect fit for the mellifluous tones of Mr. Pence, who called himself “Rush Limbaugh on decaf.” It also gave him statewide name recognition, and in 2000 he won an open primary and was elected to the U.S. House. Raised a Roman Catholic, he converted to evangelicalism in college and would become a dogged advocate against abortion and same-sex marriage.

His six-term legislative record in Congress was thin; he never wrote a successful bill. But Mr. Pence was among the first to try to cut off federal funding for abortion services, says Marjorie Dannenfelser, president of Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America. “It was a time when touching Planned Parenthood was the third rail. He was really a pioneer,” she says.

By 2008, Mr. Pence had risen to the third rank in House Republican leadership. He had also drawn the attention of the Koch brothers and other conservative donors in their network, which favored candidates who opposed taxes and regulations, particularly on fossil fuel industries.

Marc Short, his chief of staff in the House and later in the White House, arranged for Mr. Pence to speak at a Koch fundraising retreat in 2009, according to a 2017 New Yorker article. Mr. Short, who has testified to the Jan. 6 committee and was with Mr. Pence that day, later became president of the Kochs’ “dark-money” political organization. Other former Pence staffers also worked for Koch political and corporate entities.

After Mr. Pence was elected governor of Indiana in 2012, he continued to build a national profile, leaning into cultural war issues and fueling speculation of a future presidential run. “There was never any doubt in my mind that Mike wanted to go [back] to Washington, D.C. Being the governor was just a steppingstone,” says Mr. Gregg.

In 2015, Mr. Pence signed a controversial religious freedom bill that critics said permitted companies to discriminate against LGBTQ individuals. The bill, later rescinded, sparked corporate boycotts of Indiana that soured some donors on Mr. Pence’s social agenda and set up an unexpectedly tough rematch against Mr. Gregg.

“A lot of people thought his time as governor was winding down,” says Andrew Downs, a political science professor at Indiana’s Purdue University Fort Wayne.

Then, Mr. Pence was handed an opportunity. In July 2016, after several other mainstream Republicans had taken a pass, Mr. Trump announced him as his running mate, reportedly praising Mr. Pence backstage as “straight from central casting.”

In joining the ticket, Mr. Pence’s goal may not have been to play second fiddle in the White House as much as it was to set himself up as a presidential contender in 2020, says Joel Goldstein, professor emeritus of law at St. Louis University and an expert on the vice presidency.

At that stage, a Trump presidency seemed to most observers a long shot. “His calculation was that he would inherit Trump supporters and join that to the religious right support that he had,” Mr. Goldstein says. “What he didn’t bargain on is that he would win.”

“He did what his conscience told him to do”

Once elected, Vice President Pence served as a loyal lieutenant, displaying a solidarity that critics likened to sycophancy. During Mr. Trump’s most controversial moments, such as when he seemed to offer praise for neo-Nazis or shared discredited COVID-19 treatments, Mr. Pence never betrayed any public discomfort. He defended Trump policies and deflected all criticisms.

Even now, after breaking with Mr. Trump over his attempt to overturn the 2020 election, Mr. Pence can’t seem to decide whether to bury or praise Caesar. He hasn’t testified before the Jan. 6 committee, though has made clear he does not believe he had the authority to do what Mr. Trump asked of him on Jan. 6. The closest he’s come to a direct rebuke was in a February speech to the Federalist Society, in which he said: “I heard this week that President Trump said I had the right to overturn the election. President Trump is wrong.”

Taking a stronger stand against Mr. Trump would probably carry too big a cost, says the Indiana Republican. “You can do that. But you can’t be president,” he says.

Last year, Mr. Pence set up an Indianapolis-based advocacy organization, Advancing American Freedom, that he has used to raise money and support GOP candidates. In May, he notably campaigned for Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp, a fellow conservative who drew Mr. Trump’s ire when he refused to overturn his state’s 2020 electoral results. Despite a barrage of attacks from the former president, Governor Kemp never returned fire, focusing instead on his own record. He handily defeated his Trump-backed primary opponent.

Mr. Pence “believes that the Republican Party is the party of the future and will continue to crisscross the country in support of conservative candidates that will return America to a path of safety and prosperity,” says a spokesman for the former vice president.

The advisory board of Advancing American Freedom has several Trump administration alumni and prominent national conservatives. Among them is Ms. Dannenfelser of Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America, who praises Mr. Pence’s actions on Jan. 6. “He’s a man who stood with principles and dignity. He did what his conscience told him to do. He does the hard things,” she says.

Another board member is former Trump Education Secretary Betsy DeVos. Mr. Pence recently met with the DeVos family and other influential donors in Michigan, The Washington Post reported.

Mr. Pence’s advisers are reportedly focused on South Carolina and its evangelical voters as key to a possible 2024 campaign. That strategy may run up against the reality that the former president remains extremely popular with white evangelicals who in 2016 decided to look past Mr. Trump’s personal sins in pursuit of larger political goals. By putting three anti-abortion justices on the Supreme Court, Mr. Trump can say he delivered on his promises.

On the day Mr. Pence’s legal counsel testified before the Jan. 6 committee, the Faith and Freedom Coalition held its annual gathering in Nashville, Tennessee. A year earlier, Mr. Pence had been booed at the same event in Orlando, and he skipped it this time. So he wasn’t present when Mr. Trump dismissed the hearings as “a complete and total lie,” dangling pardons for convicted riot participants, and blasting Mr. Pence for certifying the 2020 electoral count.

“Mike Pence had a chance to be great. He had a chance to be frankly historic. But just like Bill Barr and the rest of these weak people, Mike – and I say it sadly because I like him – but Mike did not have the courage to act,” Mr. Trump said.

Still, the 2024 election is more than two years away, and Mr. Pence has time to try to win back alienated Trump supporters. And as longtime political observers know, any number of things could happen between now and then to scramble the race.

“I think people are willing to hear him out,” says Patrick Hynes, a GOP strategist in New Hampshire. “What happens next is impossible to tell.”

Note: An earlier version of this story stated that Mr. Pence was booed at some gatherings of conservative activists last year. He was booed at the 2021 Faith & Freedom Coalition conference in Orlando.

Biden in Israel: A meeting of the (moderate) minds?

Joe Biden’s meeting in Israel with Yair Lapid brings together two democratic leaders who embrace moderation and deplore extremism, potentially opening the door to cooperation and trust.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Neri Zilber Contributor

The commonalities between U.S. President Joe Biden and Israeli Prime Minister Yair Lapid, meeting this week in Israel, were evident in their campaigns for office. In March 2021, as head of the centrist Yesh Atid party, Mr. Lapid was fighting to unseat the long-serving and right-wing Benjamin Netanyahu. His goals, he said in an interview at the time, were to restore “sanity” to Israeli politics, fight against the “politics of fear and hate,” and ensure the country’s future as a liberal democracy.

The campaign he ran back then, advised by an American strategist allied to the Democratic Party, drew comparisons to Mr. Biden’s general election victory a few months prior – right down to the conscious effort to hover above the toxic fray and to restore a modicum of decorum to the proceedings.

In his inaugural speech to Israel as caretaker prime minister July 2, Mr. Lapid spoke of the “common good” and “that which unites us.”

“Both leaders express concern regarding the illiberal winds blowing in their respective democracies, so there’s a potential bond there,” says Dan Shapiro, U.S. ambassador to Israel in the Obama administration. “They’re both aware of their responsibilities to conduct themselves according to democratic norms, institutions, and values.”

Biden in Israel: A meeting of the (moderate) minds?

Joe Biden is set to make his maiden trip as president to the Middle East this week, landing in Israel Wednesday before flying to a regional summit in Saudi Arabia over the weekend.

Much of the attention will be on the president’s meeting with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman – once referred to by Mr. Biden as a “pariah.” But in Jerusalem he will be hosted by a friendly Israeli leader much closer to the president’s own political values – a moderate with “an aversion to extremes.”

Mere weeks ago, this wasn’t a given. Israeli Prime Minister Yair Lapid assumed the top spot as caretaker late last month after the dissolution of the broad, 1-year-old government he formed and led alongside the more right-wing Naftali Bennett.

With snap elections scheduled for Nov. 1 – Israel’s fifth ballot in less than four years – President Biden’s long-planned visit comes at a crucial moment for Mr. Lapid as he takes his first tentative steps in office while attempting to solidify his electoral prospects.

One subtext for the Biden visit: avoiding discord over fraught issues, such as Palestinian-Israeli diplomacy and Iran’s nuclear program, that could weaken Mr. Lapid’s standing.

The symmetry and commonalities between Mr. Biden and Mr. Lapid were plainly evident in their campaigns for office. In March 2021, as head of the centrist Yesh Atid party, Mr. Lapid was fighting to finally unseat the long-serving and right-wing Benjamin Netanyahu. His goals, as he said in an interview at the time, were to restore “sanity” to Israeli politics, to fight against the “politics of fear and hate,” and to ensure the country’s future as a liberal democracy.

The campaign Mr. Lapid ran back then, advised by an American strategist allied to the Democratic Party, drew comparisons to Mr. Biden’s successful general election victory a few months prior – right down to the conscious effort to hover above the toxic fray and to restore a modicum of decorum to the proceedings.

“If you’re trying to represent a culture that stands in opposition to all the hate and bigotry and type of campaign talk of recent years, then you need to start with yourself. You shouldn’t be part of it,” Mr. Lapid said in the interview. “No one needs me to yell and curse, and I’m not that successful at it.”

“That which unites us”

It worked for him. Mr. Lapid was able to cobble together a broad coalition government that was the most ideologically diverse in Israel’s history: eight parties spanning the spectrum from pro-settler right-wingers to pro-peace leftists and centrists. And for the first time in Israeli history, it included an Arab-Israeli faction.

In his inaugural speech to the nation as prime minister on July 2, Mr. Lapid spoke of the “common good” and “that which unites us.”

“There will always be disagreements,” Mr. Lapid added in the speech. “The question is how we manage them, and how we make sure they don’t manage us. The deep Israeli truth is that on most of the truly important topics, we believe in the same things.”

Israeli officials and analysts have highlighted the fact that the two leaders also believe in many of the same things. According to one senior Israeli official, who requested anonymity, they’re both “centrists, pragmatists, and moderates who have an aversion to extremes,” and truly perceive themselves as bulwarks against the rise of populist nationalism in their countries.

“Both leaders express concern regarding the illiberal winds blowing in their respective democracies, so there’s a potential bond there,” says Dan Shapiro, a distinguished fellow at the Atlantic Council and former U.S. ambassador to Israel in the Obama administration. “They’re both aware of their responsibilities to conduct themselves according to democratic norms, institutions, and values.”

The emphasis on shared values also extends to Mr. Lapid’s long-stated support for a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the government’s effort since taking office to repair relations with the Democratic Party in the U.S. and restore Israel’s bipartisan support in Washington.

“I’ve had a disagreement with Netanyahu for some time, about the fact that he completely associated Israel with the Republican Party, and not even with the entire Republican Party but with the [Donald] Trump wing of the Republican Party,” Mr. Lapid said in the interview last year. “For years I told Netanyahu – this will end badly.”

The Netanyahu issue

The mending of ties over the past year, according to analysts, has been successful. Major policy disagreements, particularly on the Iran nuclear threat, were managed behind closed doors, with the Biden administration careful not to press the Bennett-Lapid government on issues, like the Palestinian conflict, with the potential to destabilize its fragile hold on power.

The unstated American goal? To avoid a return to power by Mr. Netanyahu.

“The U.S. administration was very interested in [the survival of] this government,” says Gili Cohen, diplomatic correspondent for Israel’s Kan Public Broadcaster. “The diversity of the Israeli government was a major factor in this – not just ideologically, but also with respect to the number of women serving as ministers, that an Arab-Israeli was a minister, that an Arab-Israeli party was part of the coalition.”

To be sure, Mr. Biden will, per official protocol, meet as well with Mr. Netanyahu, now the opposition leader, albeit for a scheduled 15 minutes. According to Ambassador Shapiro, whatever the personal preference of the American president in terms of the identity of the Israeli premier, Mr. Biden is savvy enough to avoid getting entangled in domestic Israeli politics.

“Any U.S. effort to influence an Israeli election is ill-advised and likely to be unsuccessful. [Biden] will play it straight,” Mr. Shapiro says. “This will produce the best policy result and it’s the best politics too.”

None of this means that the expected warm embrace of the U.S. president will not be a boon for Mr. Lapid’s reelection chances.

“Without a doubt … it will help him,” says Ms. Cohen. Mr. Netanyahu, during successive election campaigns, touted his self-image as a global statesman, erecting giant billboards across the country with his picture alongside world leaders like Mr. Trump, Russia’s Vladimir Putin, and India’s Narendra Modi. The tagline: “Netanyahu: A League Apart.”

“Lapid doesn’t have those images yet, so he wants to project himself to the public as a real candidate for prime minister that’s playing in the big leagues,” says Ms. Cohen. “Every moment and interaction and picture with Biden will be seized on by Lapid.”

During the next four months ahead of election day, Mr. Lapid will try to show the voting public that he is up to the job of running the complicated and fractious country.

“The public will reward a prime minister doing a good job, who they feel they can trust,” says the senior Israeli official.

Outreach to Palestinian leader

What Mr. Lapid does in the office, and how he chooses to govern, will be made clearer in the coming days alongside Mr. Biden on a host of policy issues, although no major shifts are expected from his partner Mr. Bennett’s tenure. “Different nuances perhaps, but not huge differences,” adds the Israeli official.

Mr. Lapid, this past weekend, already spoke by phone with Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, a step Mr. Bennett refused to take. and some small-bore measures are being countenanced to help support the Palestinian economy and health system.

Israel also expects further moves toward normalization with its Arab neighbors to come out of the Biden visit, including possible aviation links with Saudi Arabia and progress toward a regional air defense system. And according to Israeli officials, Israel’s opposition to the Iran nuclear agreement – which the Biden administration has aimed to restore – will continue, albeit with the aim of further coordinating Israeli and U.S. positions in the event that talks with Iran completely collapse.

Fundamentally, however, the two leaders’ wholehearted and almost unconditional support for a strong U.S.-Israel relationship is expected to be the main guiding theme for the coming days. Mr. Biden has long described himself as a Zionist and repeatedly highlights the fact that he has met with every Israeli premier dating back to the early 1970s.

“Biden’s emotional attachment to Israel has been central to his politics during his decadeslong career,” says Ambassador Shapiro. “So a visit to Israel early in his term is very natural.”

Even loyalists are targets in latest Russian crackdown. Why?

The Kremlin has launched a treason-related crackdown against elites who seem to have been loyally serving the establishment – which may be a sign of disintegrating trust at the top.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

A recent spate of unusual criminal cases amid the nearly 5-month-old war in Ukraine suggests that the trust that binds the Kremlin with the various elites who actually run the system may be starting to fray.

The cases are all different, and some observers insist that most have nothing to do with the war. But no one disputes that the number of treason-related prosecutions has spiked, and that formerly “untouchable” people have suddenly found themselves behind bars.

Some cases, such as the NHL-contracted goalie Ivan Fedotov, who was accused of draft-dodging, have an easy, war-related explanation. Others, such as former military reporter Ivan Safronov, charged with high treason for alleged information-sharing, seem murkier. And how to comprehend the arrest on strange embezzlement charges of staunch liberal Vladimir Mau, head of Russia’s largest state university, who had recently signed a letter of support for the Kremlin’s war in Ukraine?

“It certainly seems like some people who were immune have now lost their immunity,” says lawyer Sergei Davidis. “It is becoming clear that there is a general tightening of the system going on, and a lowering of the legal and conceptual bar [for treason]. It suggests that the whole system is collapsing.”

Even loyalists are targets in latest Russian crackdown. Why?

Definitions of “treason” and what brands a citizen as a “foreign agent” have been gradually expanding for several years in Russia. But a recent spate of unusual criminal cases amid the nearly 5-month-old war in Ukraine suggests that the trust that binds the Kremlin with the various elites who actually run the system may be starting to fray.

The cases are all different, and some observers insist that most have nothing to do with the ongoing war. But no one disputes that the number of treason-related prosecutions has jumped fivefold over the past decade as Russia’s geopolitical tensions with the West have exploded, and that some people formerly thought of as “untouchable” have suddenly found themselves behind bars.

While loyalists disagree, government critics speculate that the surge in treason-related cases is a sign that the Kremlin is afraid of losing control, and is looking for enemies to make examples of.

“Everybody is looking for enemies,” says human rights lawyer Ivan Pavlov. “And while the external enemies are obvious, the task of finding internal ones falls to the security services. If there is political demand for such cases, it has the effect of creating supply.”

“If there is no actual treason, it can be invented”

Some cases, such as the NHL-contracted goalie Ivan Fedotov, who was accused of draft-dodging and sent to perform military service in the far north, have an easy, war-related explanation. Others, such as former military reporter Ivan Safronov, charged with high treason for alleged information-sharing during his time as a journalist, seem murkier. So does the early-July arrest of Siberian physicist Dmitry Kolker, alleged to have shared secrets with China, who was dragged from his sickbed and died in custody two days later.

And how to comprehend the arrest on strange embezzlement charges of staunch liberal Vladimir Mau, head of the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, the country’s largest state university, who had recently signed a letter of support for the Kremlin’s war in Ukraine?

It may be, as the Latvia-based opposition outlets Meduza and The Bell recently reported, that tensions are growing inside Russia’s state institutions, such as the Central Bank. Many key people may be determined to continue doing their jobs, but the war has shaken their belief in the cause they are serving. The articles suggest that security services are escalating prosecutions, often on flimsy grounds, in order to set a stern example for all those who may be having doubts.

“It certainly seems like some people who were immune have now lost their immunity,” says Sergei Davidis, a lawyer with the now-banned human rights organization Memorial. “We shouldn’t exaggerate here, try to make this process look more primitive than it is, or compare it to mass repressions. But it is becoming clear that there is a general tightening of the system going on, and a lowering of the legal and conceptual bar [for treason]. It suggests that the whole system is collapsing, and amid the turbulence these cases arise.”

Such subterranean pressures are, as yet, hard to substantiate. On the surface, Russia has returned to an almost prewar state of normalcy. The initial public shock that hit when Russia invaded Ukraine in February appears to have largely worn off, and the early expectations of mass anti-war sentiment have diminished. Even the impact of massive sanctions on average Russians has been surprisingly minimal. Many Russians have accepted the Kremlin’s narrative about the war’s purposes, and polls show surging support for it.

Leonid Gozman, a longtime liberal opponent of the Kremlin, argues that the war itself is a symptom of the deterioration of elite unity as the era of Vladimir Putin begins to unwind.

“The Kremlin decided to launch this military operation because they realized their leadership was increasingly ineffective, and future prospects looked bleak,” he says. “It was a reaction to internal challenges they are not able to cope with. Strengthening the repressive instruments, cracking down, is just part of the effort to retain stability.”

Mr. Pavlov, who represents the journalist Mr. Safronov, says that the legal criteria for treason have been sliding steadily, making it less about provable criminal cooperation with a foreign government, and more about any suspicious contact with foreigners or disloyal-sounding speech.

“The law about ‘helping foreigners to conduct activities against Russia’ can mean almost anything,” he says. “If there is no actual treason, it can be invented. As a lawyer, I’ve taken part in cases against journalists, scientists, and housewives. Such cases are multiplying.”

“The potential for protests is actual”

The state’s intent, at least so far, appears more designed to intimidate potential protesters than to seek out and arrest large numbers of them. Mr. Pavlov, who is presently located in Georgia, cites a recent televised raid by FSB security forces on a Moscow apartment, where the tenant had allegedly donated money to a Ukrainian group. Since that’s not a crime, no charges were filed.

“There will be no legal consequences, but the action was clearly meant to warn public opinion,” he says. “There are too many such people. So the FSB rushed in, in the early morning, and read a warning to the citizen on camera.”

Sergei Markov, a former Putin adviser, argues that there is no campaign against “liberals” in Russian institutions, since elite groups – often referred to as “clans” – in Russia tend to be based in shared origins or interests, rather than ideology. He argues Vladimir Mau, a staunch veteran liberal, was probably targeted by a rival academic organization jealous of the resources he commanded, rather than persecuted for his ideological views.

“In the West people think simplistically that there is a ‘party of liberals’ and a ‘party of siloviki [security hardliners]’ in Russia,” he says. “That’s nonsense. They coexist inside the same clans. Our political processes are far more complicated than people think.”

But the war-related tightening of screws is very real, he adds.

“The Kremlin sees the threat from the West as our biggest danger. Even if the situation seems stable now, we have seen that they are out to destroy us. [U.S. President Joe] Biden has said as much,” he says.

“Some unofficial polls show that 70% of state journalists oppose the special operation, even if they seem to be doing their jobs properly right now. The potential for protests is actual; they will happen if the state shows any weakness at all. Putin and his colleagues are former intelligence operatives. They are very suspicious. They see threats emanating from the West and – you know what? – events have often proven them to be right.”

The Explainer

After Roe, many questions: Where the legal fight moves next

In some ways, overturning Roe was just the beginning of the legal battles over abortion access. Legal uncertainties include questions about interstate travel, pills through the U.S. mail, and the enforcement of state bans.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

As the fallout from the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade continues to reverberate throughout America, a significant number of questions, both legal and logistical, have been thrust upon a nation now divided by the legal status of abortion access.

Half of states are moving rapidly to ban or severely restrict abortion. There are legal questions about the methods they will use to enforce these new laws, and the scope of criminal or civil liabilities for doctors, women, and facilitators. Interstate travel and the status of medications sent via U.S. mail or private courier are also part of the legal uncertainties that have emerged after the Supreme Court eliminated a constitutional right in place for almost half a century.

“There’s going to be a lot of legal questions surrounding these issues for quite a while,” says Jessie Hill, professor of law at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. “Right now, I think the big impression is that it’s just utter chaos from a legal perspective.”

After Roe, many questions: Where the legal fight moves next

As the fallout from the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade continues to reverberate throughout America, a significant number of questions, both legal and logistical, have been thrust upon a nation now divided by the legal status of abortion care.

Half of states are moving rapidly to ban or severely restrict abortion. There are legal questions about the methods they will use to enforce these new laws, and the scope of criminal or civil liabilities for doctors, women, and facilitators. Interstate travel and the status of medications sent via U.S. mail or private courier are also part of the legal uncertainties that have emerged after the Supreme Court eliminated a constitutional right in place for almost half a century.

“There’s going to be a lot of legal questions surrounding these issues for quite a while,” says Jessie Hill, professor of law at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. “Right now, I think the big impression is that it’s just utter chaos from a legal perspective.”

Last week, President Joe Biden signed an executive order seeking to protect access to reproductive health services, including abortion pills and contraception, and the free flow of information about reproductive health care. On Monday, the Department of Health and Human Services said federal law requires doctors and hospitals to offer abortion services in the cases of medical emergency. The Biden administration also pledged to convene a network of pro bono attorneys to represent those who offer such services in the face of states seeking criminal or civil charges.

Over a dozen states – including Arkansas, Idaho, Mississippi, North and South Dakota, and Texas – had “trigger laws” in place in anticipation of the June 24 decision. These banned abortion immediately or within 30 days. New bans in states such as Arizona and Kentucky have been challenged in state courts, while similar challenges have failed in Louisiana and Mississippi. Over all, some 26 states are expected to ban or severely restrict all forms of abortion.

At the same time, states such as California, Connecticut, New York, Nevada, and Oregon are moving to protect or expand abortion rights – even providing funding to help those who travel from states that ban the procedure. These states also have countered possible legal maneuvers, passing laws that ban any cooperation with criminal or civil investigations against those seeking or performing abortions.

Will residents of states that ban abortion be able to travel to other states for the procedure?

While there are a number of proposals being floated, there are currently no state laws that explicitly prohibit or penalize those who seek abortion services in a different state.

In his concurring opinion overturning Roe, Justice Brett Kavanaugh signaled that such restrictions might be unconstitutional. “[May] a State bar a resident of that State from traveling to another State to obtain an abortion?” he wrote. “In my view, the answer is no based on the constitutional right to interstate travel.”

But the legal questions are not settled, says John Vile, professor of political science at Middle Tennessee State University. “The right to travel is an ‘unenumerated constitutional right,’ which is the major reason the court majority gave for overturning Roe.”

And this is a generally untested area of law, says Professor Hill. “Without a state passing a particular law on this issue of out of state travel, can they still interpret their existing statutes to enforce their laws beyond their borders, basically?” she says. “And then, what if states just go ahead and explicitly pass these travel restriction laws? I think at that point you do have these constitutional questions.”

In Missouri, Republican lawmakers have proposed a travel restriction bill modeled after Texas’ novel abortion law, SB8, which authorizes members of the public to bring a civil suit against people aiding a woman in obtaining an abortion, enabling anyone to collect a $10,000 bounty for each successful civil judgment. Similarly, the Missouri proposal allows members of the public to sue those who travel out of state to get an abortion and then potentially collect civil damages.

Christian legal groups, too, are formulating model laws that would allow states to use civil courts to enforce abortion bans on citizens crossing state borders. Many Republican lawmakers are seeking legal ways to stop it. “Many of us have supported legislation to stop human trafficking,” Arkansas state Sen. Jason Rapert, president of the National Association of Christian Lawmakers, told The Washington Post. “So why is there a pass on people trafficking women in order to make money off of aborting their babies?”

Can states ban abortion medication sent via U.S. mail or private courier?

State laws banning abortion include all forms of the procedure, including the federally approved drugs that can induce an abortion in the first 10 weeks of pregnancy. Known as “medication abortion,” the combination of mifepristone and misoprostol currently makes up more than half of abortions performed annually in the United States, and demand has surged since June 24. Many experts believe medication abortion will become the center of legal battles in the post-Roe landscape.

Before the Supreme Court ruling, states had different regulations governing the administration of abortion pills. Over 30 states required licensed physicians to administer the drugs, and most of these required a doctor to be present. In the middle of the pandemic, however, the Food and Drug Administration lifted those requirements, saying medications could be prescribed online and sent in the mail.

On Friday, President Biden’s executive order instructed the Department of Health and Human Services to “protect and expand” access to medication abortion, without giving specifics. Last month, U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland said “states may not ban mifepristone based on disagreement with the FDA’s expert judgment about its safety and efficacy.” In Mississippi, one manufacturer of abortion pills is suing the state, arguing that Mississippi’s regulations are unduly excessive and unlawfully preempting the FDA’s authority.

These arguments are limited, however, says Professor Hill. “FDA approval does suggest that states might run afoul of federal law if they try to restrict distribution of the drug, or restrict mailing of the drug for reasons covered by FDA regulations,” says Professor Hill. “But if states are going to say, you can’t use the drug to end a pregnancy because abortion is illegal in this state, then that’s a very different thing. There’s not a strong argument that FDA approval somehow preempts that. In states where abortion is banned, it’s all banned.”

Women in the United States can already be prescribed medication abortion from doctors in Europe, however. Some American providers are already developing plans to provide abortion medication to those in states that ban abortion, and setting up supply chains. Using telehealth services and mail-forwarding services, a person could get a prescription online and then set up a mail forwarding address in a state where abortion is legal. The pills would then be automatically forwarded via mail or courier, masking the origin of the drugs.

How will states enforce bans?

Stopping medication abortion delivered via U.S. mail or private courier will prove an enormous challenge, especially since most states that allow abortion are promising not to cooperate with any investigations or subpoenas from those that don’t, experts say.

“And some women, unable to travel, will likely also seek illegal abortions,” says Dr. Vile. “This could lead, much like prohibition of alcohol in an earlier era, to widespread evasion and help from a criminal underworld. And much could ultimately rest with juries. Would a jury convict a woman for getting an abortion, even in pro-life states, if she had been raped, was the victim of incest, or faced an imminent threat to her health?”

Still, experts foresee a chilling effect on providers, even in states that permit abortions. In Montana, officials from Planned Parenthood preemptively restricted access to medication abortion from out of state travelers. Surrounded by four states that have recently banned or severely restricted abortion, clinics do not want to face the legal uncertainty of being held criminally or civilly liable.

“There’s also a lot of uncertainty within these states about the health exceptions or the medical necessity exceptions in these bans on abortion,” says Professor Hill. “Providers and others will be extra cautious because you’re going to want to err on the side of not exposing yourself to criminal liability. Which won’t help women who need care, because the reality is that uncertainty often translates into a kind of chilling effect on provision of care.”

At the same time, some Democratic prosecutors in big cities located in states that ban abortion are vowing to refuse to bring charges. District attorneys in a number of states, including Georgia, Louisiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin have said they won’t prosecute cases under their new state bans. City officials in Austin, Texas, too, have proposed resolutions to not enforce the state’s ban. In response, some Republican lawmakers want to allow conservative prosecutors in outlying areas to prosecute crimes outside their jurisdictions.

Ms. Hill says that she has noticed widespread worry about digital surveillance – such as location services and period tracking apps that are not protected by federal health privacy laws; state government intrusions into private mail; and other efforts to prevent access to information about abortion.

But in pre-Roe America and other countries with restrictions, enforcement tended to be scattershot: “Someone shows up in the emergency room after an illegal abortion and they say, what happened?” Professor Hill says. “Or, someone finds out, like a parent or a partner who is not happy about a woman having an abortion, and they go to the police.”

Books

Need a summer escape? Try Maine, East Germany, occupied France.

Our 10 picks for July include books that affirm the vitality of friendship, celebrate leadership on a dangerous mission, and explore truth, honor, and loyalty in an ever-shifting world.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Monitor reviewers

If you’re looking for adventure in your summer reading, we’ve got some suggestions.

The books that Monitor reviewers liked best this month run the gamut from an epic novel about women’s friendship to a history-rich spy thriller set during the Cold War.

Among the nonfiction selections is a director’s memoir about the making of the baseball film “Bull Durham,” along with a biography of singer Josephine Baker, who spied on behalf of the Allies during World War II.

You’ll also find an account of an early 20th-century expedition to Greenland’s ice cap. Enjoy the adventure!

Need a summer escape? Try Maine, East Germany, occupied France.

Empathy and compassion, along with honor and truth, are qualities woven throughout the books that made our list this month, along with penetrating insights and fascinating glimpses of history.

1. Fellowship Point by Alice Elliott Dark

Alice Elliott Dark’s exquisitely written, utterly engrossing novel “Fellowship Point,” set in Maine’s gorgeous but threatened coastal landscape, explores the beauty and tensions of a lifelong friendship between two women whose choices have taken them down different paths. The result is a deftly woven narrative about caring for the places and people we love, and an affirmation that change and growth are possible at any age.

2. The Boys by Katie Hafner

“I’d spent a lifetime in hibernation,” muses socially anxious tech whiz Ethan Fawcett, “storing things up to share with Barb.” Barb is the psychology major and soon-to-be love of his life; together they form the emotional center of Katie Hafner’s impeccably written and surprise-fueled debut novel about empathy’s role in addressing childhood trauma.

3. Winter Work by Dan Fesperman

“In winter, the forest bares its secrets,” begins Dan Fesperman’s history-rich spy thriller set in East Germany after the Berlin Wall came down. Former Stasi spy Emil Grimm, investigating the killing of a colleague, crosses paths with agents, police, and hit men. It’s a well-crafted examination of truth, honor, and loyalty in a shifting world.

4. The Poet’s House by Jean Thompson

Jean Thompson’s novel depicts the eccentric world of poets and artists through the eyes of an insecure gardener, Carla, who finds herself a guest in their enclave. It’s a story that’s beautifully rendered with wry wit, unusual charm, and poignant insights.

5. The Half Life of Valery K by Natasha Pulley

Dr. Valery Kolkhanov is transferred from a prison in Siberia to a secret Russian territory in 1963 to study the effects of radiation on animals. Natasha Pulley builds a surreal world that slowly reveals immense dangers. It’s an absorbing Cold War thriller as well as a tribute to courage and determination.

6. How to Read Now by Elaine Castillo

“‘How to Read Now’ runs off the tongue a little easier than ‘How to Dismantle Your Entire Critical Apparatus,’” writes novelist Elaine Castillo in her debut nonfiction book, but such deconstruction is what makes for smarter, stronger readers. Boundless erudition and eloquent exasperation define her essay collection, which provokes and discomfits, but ultimately engages, edifies, and thoroughly entertains.

7. The Church of Baseball by Ron Shelton

Screenwriter and director Ron Shelton writes entertainingly about making the 1988 film “Bull Durham,” which no less than Sports Illustrated judged the best sports movie of all time. His book is a story of inspiration, talent, persistence, good fortune, and even better timing.

8. Into the Great Emptiness by David Roberts

In 1930, a young Englishman and his crew set off on an expedition to Greenland’s ice cap, dog-sledding through blizzards and dodging crevasses. What they ultimately gained wasn’t so much an understanding of a fantastic, frozen landscape, but of life’s essentials – love, leadership, and big breaks.

9. Agent Josephine by Damien Lewis

Journalist Damien Lewis tells the exhilarating story of famed performer Josephine Baker’s espionage activity during World War II. Drawing on newly released historical documents, he chronicles her bravery and ingenuity on behalf of the Allies.

10. Proving Ground by Kathy Kleiman

Kathy Kleiman’s debut nonfiction is a celebratory biography of the six women who helped program ENIAC, the first general-purpose computer. In engaging prose, she describes how the women found opportunities during World War II, while many men were overseas, and overcame discrimination and harassment to accomplish their important work.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Listening as a political depolarizer

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

America’s widening ideological divide has resulted in a crisis of confidence in how voters view their elected officials. Fixing that problem – restoring the system of representative democracy to reflect more closely its original design – may not be as hard as it sounds. A new study by the University of Maryland found that voters place more importance on accountability through direct dialogue with their elected officials than they do on party identity.

That attitude provides a counterpoint to the common view that American society is irredeemably polarized and democracy is broken as a result.

“We have more in common than we believe, but we can only discover the common ground when we take the time to show up, to listen, and to respect one another,” writes Maine state Sen. Chloe Maxmin, who co-wrote her book, “Dirt Road Revival,’’ with her campaign adviser Canyon Woodward.

The ideological divide is not without a remedy. It starts with restoring a simple premise of representative democracy – that by listening to all those they represent, public officials can find the greatest good for the greatest number of people.

Listening as a political depolarizer

Half a century ago, 144 Republicans in the U.S. House were less conservative than the most conservative Democrats, according to a recent analysis by the Pew Research Center. And 52 House Democrats were less liberal than the most liberal Republicans. Members voted with their party leadership roughly 60% of the time. Today there is no such overlap. The House has only about two dozen moderates. All members vote the party line more than 90% of the time.

That wider ideological divide has resulted in a crisis of confidence in how voters view their elected officials. Chloe Maxmin, a Democratic state senator from Maine, notes in a new book criticizing her party’s dismissal of rural America, “People from all across the political perspective share one thing in common: a deep distrust of politics and a profound frustration with not having their voices heard in our government.”

Fixing that problem – restoring the American system of representative democracy to reflect more closely its original design – may not be as hard as it sounds. A new study by the University of Maryland found that voters place more importance on accountability through direct dialogue with their elected officials than they do on party identity. That attitude provides a counterpoint to the common view that American society is irredeemably polarized and democracy is broken as a result.

The study, based on conversations with more than 4,300 voters, starts with a pessimistic benchmark: Ninety-one percent of those surveyed believe lawmakers “have little interest in the views of their constituents” and are more influenced by special interests than by “the people.” It then asks voters to consider a hypothetical scenario: Would it matter if a candidate promised always to consult his or her constituents and give their recommendations higher priority than the views of the candidate’s party leadership?

Seven in 10 said it would, and 60% said they would cross party lines to vote for a candidate making that pledge. Similarly, 71% said that “the majority of the public as a whole is more likely to show the greatest wisdom on questions of what the government should do” than either just Republicans or just Democrats.

“We have more in common than we believe, but we can only discover the common ground when we take the time to show up, to listen, and to respect one another,” writes Senator Maxmin, who co-wrote her book, “Dirt Road Revival,’’ with her campaign adviser Canyon Woodward.

While 49 members of Congress have already announced they are not seeking reelection this year – many out of frustration with partisan rancor and polarization – some are showing the value of that kind of listening. Rep. Dusty Johnson, a Republican from South Dakota, for example, easily defeated a primary challenger last month despite rejecting his party’s false claims about the 2020 election. The reason? He has built trust with voters through monthly town hall meetings and conference calls.

To apprehend the perspective of others, “We must learn to listen to what they have to say – and to listen from their position, not from our own,” writes Heidi Maibom, a philosophy professor at the University of Cincinnati, in a new essay in the online Aeon newsletter.

The ideological divide of today’s politics is not without a remedy. It starts with restoring a simple premise of representative democracy – that by listening to all those they represent, public officials can find the greatest good for the greatest number of people.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

And just like that, the pain was gone

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Brian Webster

Faced with knee pain that became a long-standing impediment to free movement, a man knew he needed a breakthrough. In this short podcast, he shares some of the key ideas that helped him find permanent healing through prayer.

And just like that, the pain was gone

To listen, click the play button on the audio player above.

For an extended discussion on this topic, check out “And just like that, the pain was gone,” the June 13, 2022, episode of the Sentinel Watch podcast on www.JSH-Online.com.

A message of love

‘A star is born!’

A look ahead

Thanks for reading our stories today. We hope you’ll share your favorite articles on social media. Tomorrow, our package of stories includes a peek inside The Canadian Museum for Human Rights.