- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

What a leather-bound box says about Mar-a-Lago search

What was in the leather-bound box?

That’s a question that’s been a matter of great interest in Washington since the Department of Justice revealed on Aug. 12 that the FBI had seized such a box in its search of former President Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago home.

Now we may have a partial answer. Last night federal prosecutors attached an intriguing photo to a new court filing – a stack of documents marked “Secret” and “Top Secret” laid on a rug. They came from a container in Mr. Trump’s office, said the filing.

The papers are identified as “Exhibit 2A.” This suggests they were in the leather box, which is labeled “Exhibit 2.” The fancy box’s purpose remains undisclosed.

The papers – whether they were nestled in the box or not – are a visual symbol of the troubles facing Mr. Trump.

According to the FBI, they remained in the former president’s workspace long after the Department of Justice had issued a subpoena requesting return of all papers marked classified – and months after Mr. Trump’s lawyers attested he had done so.

It is possible they weren’t returned due to chaotic record keeping, or some administrative mistake. That’s what some experts suggest.

“It is not clear from [yesterday’s] filing if the FBI has evidence of intentional acts of concealment as opposed to negligence in keeping track of such material,” writes George Washington University law professor Jonathan Turley.

But others point out they could also be evidence of willful possession of sensitive documents intelligence agencies want back. The Mar-a-Lago FBI search found twice as many documents with classified markings as the Trump team had previously returned. Increasingly it appears the core of a Department of Justice case on the documents could center on obstruction of justice.

“If the FBI found these documents in your home, you would go to jail,” tweets Walter Shaub, former director of the Office of Government Ethics, of the Exhibit 2A photo.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Who’s a Latvian and why? A complex question just got harder.

Latvia had been making progress toward the inclusion of its ethnic Russian citizens. But the war in Ukraine has frozen such movement as the government raises its guard against neighboring Russia.

Since Latvia declared independence from the Soviet Union in 1990, its citizens – a quarter of whom are ethnic Russians – have been wrestling to define their identities.

As they distanced themselves from memories of Soviet occupation, the puzzle seemed to be growing less fraught. But Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine has brought old divisions to the surface.

The government is cracking down on the small minority of ethnic Russians who support President Vladimir Putin, and just when dialogue would seem more important than ever, people have largely “closed all the windows and switched off the lights” on discussion of the identity issue, says Deniss Hanovs, a professor of cultural history.

Russian Latvians may not be numerous, but they wield potential influence. Most of them are neutral on the Ukraine war, or support Kyiv, but others could cause trouble, officials fear.

One focus of discord was the Victory Memorial in the capital, Riga, commemorating the Soviet soldiers who died freeing Latvia from the Nazis. But most Latvians remember better the Soviets’ own 50-year occupation of their land. Last week the authorities toppled the monument, calling it a catalyst for polarization.

“To have a strong society ... you should have a common history,” says pollster Arnis Kaktins. “We don’t have that.”

Who’s a Latvian and why? A complex question just got harder.

The nature of Alice Zvezda’s identity is as challenging to juggle as the infant she’s pushing around a Riga park.

“My husband is Latvian and I am Russian. So I am like, both. I feel myself both,” says Ms. Zvezda as she rocks her baby stroller cradling a next-generation Russian Latvian.

That kind of dual identity had been growing easier to navigate as Latvians distanced themselves from memories of their country’s 50-year occupation by the Soviet Union that ended in the early 1990s.

But it suddenly got harder last February, when Russia invaded Ukraine and the Latvian government began arming itself with words and weapons: It is reinstituting the military draft, excising Russian language from public schools, banning Russian state media from the airwaves, and dismantling Soviet-era memorials.

The vast majority of Latvians — including a quarter of the country’s Russian speakers —are solidly against the war in Ukraine, but a small and significant segment of the Russian diaspora sympathizes with Russian President Vladimir Putin. Once tolerant of such citizens, the Latvian government is now trying to crack down on their way of thinking, just when Latvian society was making some progress toward inclusion of its multitude of ethnic identities.

It would seem that dialogue over Latvian identity, a complex construct of language, culture, and nationality, is needed more than ever. But since the war began, people have largely “closed all the windows and switched off the lights” on discussion, says Deniss Hanovs, a Russian Latvian cultural history professor at Riga Stradiņš University.

“The history of Latvia has been so very bloody and full of conflict and tragedy that most people stick to ethnic identity” when they define themselves, says Dr. Hanovs. “But we need to go beyond ethnic identity. One needs to be a citizen. The notion of [a] political nation is the only future for a multiethnic culture in Europe.”

A complicated dance

But that’s a complicated dance today for a society that’s roughly a quarter ethnic Russian. “The younger generation [of ethnic Russians and Latvians] is making families together and we do not have conflict,” explains Ms. Zvezda. “We were hoping when the generations change and the politicians are our age, it will be totally fine – love and understanding. But no, now war came. And it’s splitting the community.”

About 150,000 Russian-speaking Latvians sympathize with Russia on the war, polls have found. “That’s a lot for small Latvia,” says Ieva Bērziņa, a researcher on Russian strategy at the National Defense Academy of Latvia.

And it leaves open the possibility that the Kremlin might destabilize Latvia using the Russian diaspora. Reaching out to this population through a common language, religion, and historical memory offers Russia an “unparalleled soft power influence to further foreign policies abroad,” in the words of a 2021 report by researchers at the London School of Economics.

Dr. Bērziņa found in a 2016 study that Russian influence in Latvia could be “quite huge ... when it comes to war and real-life situations that can catalyze differences within society,” she says. “When it goes out onto the street it’s a huge problem.”

One of those potential catalysts was the Victory Memorial in Riga, where ethnic Russians congregated every May 9 to celebrate the Soviet Army’s victory over Nazi Germany. (The Soviets liberated Latvia from the Germans but ushered in their own five-decade-long occupation of the country.)

The authorities last week toppled the main obelisk, saying it risked “polarizing society,” and removed other structures from the memorial complex, in line with the wishes of roughly 75% of Latvian speakers, but against those of the same proportion of Russian speakers, according to a poll by the Latvian polling firm SKDS. It’s a stark divide.

“The monument means different things for Latvians and Russians,” explains Dr. Bērziņa. “For Latvians it’s a symbol of [Soviet] occupation and pain, and for Russian speakers it’s primarily a commemoration of their ancestors who fought against Nazi Germany.”

This lack of a shared understanding of history hinders progress toward a harmonious Latvian society, says pollster Arnis Kaktins, SKDS’s executive director.

“To have a strong society, one of the pillars is that you should have a common history, and we don’t have that,” he says. “We have two different histories regarding the Second World War – with different beliefs around whether Russia occupied us, or whether they liberated us from the evil fascists.”

Using Pushkin as a weapon

But minds are changing, nonetheless. Half of Russian speakers tell pollsters they sympathize with neither Russia nor Ukraine in the war. This group appears to be in transition away from traditional loyalties, says Mr. Kaktins.

“They are confused; they are shocked; they need more time to talk, to understand, and to process what’s actually happening,” he says. “If suddenly something happens which contradicts your worldview of Russia as beautiful and good, you don’t automatically change it in two hours. It is a very slow, gradual process. It takes a long time.”

Until the Ukraine war began, adds Dr. Hanovs, the Russian Latvian cultural history professor, ethnic Russians had seen their former homeland’s history in a heroic light, symbolized by musicians and poets such as Peter Tchaikovsky and Aleksandr Pushkin. They never associated their culture with evil.

“Now, starting from February, this is part of my own [Russian] identity,” Dr. Hanovs says, explaining that President Putin invaded Ukraine in the name of Russia’s glorious past. “It’s not only Tchaikovsky and Pushkin, but also ‘Pushkin can be used to kill people in Ukraine,’” he says.

Latvia’s defense minister, Artis Pabriks, is losing patience. He is in charge of reinstituting military conscription by 2023, and he insists that Putin supporters must understand that the glory days of the Soviet Union are over.

“How can you tolerate in your country people who are saying, ‘We’re against Parliament and against democracy and against freedom’?” asks Mr. Pabriks during an interview in Riga. “We cannot simply say, ‘Oh yes, you are against an independent Latvia but you’re welcome to walk around.’”

That hardening attitude indicates how difficult it could be to integrate Latvia without alienating those on the fringes, and without suppressing Russian culture and language.

The sizable group of Russian speakers who declare themselves patriotic citizens of Latvia might show the way, if the government takes a nuanced approach.

“I hope the Latvian political elite will manage to differentiate between those who are part of Latvia and those who still exist in the past,” Dr. Hanovs says. And some observers believe that the war might actually speed up convergence on a national Latvian identity, as Russians are forced to confront hard facts about their former motherland.

Ms. Zvezda, the young Russian Latvian mother living in Riga, harbors more modest hopes – that the growing difficulties of everyday life will push larger questions of war and peace and ethnic identity aside.

“War is very, very bad,” she says. “But it seems we are not speaking about these things anymore because we have corona, and prices are rising. We are afraid for our future.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to clarify Deniss Hanovs as the source of a quote.

Mikhail Gorbachev, the man who changed the world

Mikhail Gorbachev helped end the Cold War and oversaw the demise of the totalitarian Soviet Union, offering freedom and hope. But his dream of a “common European homeland” has died.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Mikhail Gorbachev, who died on Tuesday, was one of the most influential figures on the 20th-century international stage. Few leaders in history have ushered in such sweeping change as the last president of the Soviet Union, who fundamentally transformed his country and revolutionized global affairs.

Mr. Gorbachev broke the mold of Soviet leaders, championing “perestroika” – economic reform – and “glasnost” – opening up – in a bid to modernize a creaking system so as to ensure that it survived.

But that task proved beyond him; the system could not be saved, and as the Soviet Union collapsed the centrally planned economy followed suit, wreaking havoc on people’s lives for several years.

Feted in the West for his role in helping to end the Cold War and for laying the foundations of a democratic political system at home, Mr. Gorbachev enjoyed a much worse reputation in his native Russia after he stepped down because he was blamed for economic chaos and the precipitous fall in Moscow’s international status once the Soviet Union no longer existed.

But even if he had not intended to destroy the Soviet Union, he refused to use force to keep it alive. Steering the superpower to a peaceful end, he saved his people, and the wider world, a potentially bloody denouement.

Mikhail Gorbachev, the man who changed the world

Few statesmen in history have ushered in such sweeping change as Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader and a great visionary who sought to reshape his country and the world.

Even fewer have brought about the fundamental transformation of their own country, and revolutionized global relations too, without war, social upheaval or, indeed, any major violence at all.

But Mr. Gorbachev, who died Tuesday, lived long enough to witness his greatest legacy, the peaceful unwinding of the USSR into 15 sovereign nation states, being destroyed. The current war in Ukraine is a violent effort by Mr. Gorbachev’s successors to overturn the post-Soviet settlement, redraw the region’s borders, and impose new rules upon the global order.

Whatever world may eventually emerge from this turmoil, it is unlikely to resemble Mr. Gorbachev’s vision of a cooperative world order, mutual security, and a “common European homeland” united from Vladivostok to Lisbon.

After he left office on December 25, 1991, the giant, ramshackle superpower that had been the Soviet Union – and one pole of a bitter 40 year Cold War between East and West – ceased to exist. Thanks in large part to his efforts, as well as his impressive restraint as the USSR crumbled and its elites panicked, the world became a radically different and potentially much better place.

Fifteen independent states emerged from the ruins of the USSR, each with its own destiny. But the main Soviet successor state and Mr. Gorbachev’s homeland is Russia, which, despite everything, remains very much a work in progress.

Until recently, few in Russia would have imagined any return to the rigidly authoritarian, hyper-centralized, ideology-obsessed one-party state that Mr. Gorbachev inherited when he was handed the challenging post of Communist Party General Secretary – the Soviet Union’s top job – in March 1985.

A mold breaker

During the six tumultuous years that he led the former Soviet Union, Mr. Gorbachev laid the foundations of a democratic system by transferring the power held for 70 years by a Communist Party monopoly to real, functioning legislatures staffed by people's representatives chosen in genuinely competitive elections. He championed “glasnost,” or openness, which flung open the USSR’s long-sealed doors and windows, giving people freedom to speak their minds and access to an independent and critical media for the first time in their lives.

Less successfully, he promoted “perestroika,” or economic reform, which led to the short term breakdown of the centrally planned system, but which cleared the way for an eventual – and still incomplete – profound transformation of Russia on the principles of private property, market economics, and individual rights.

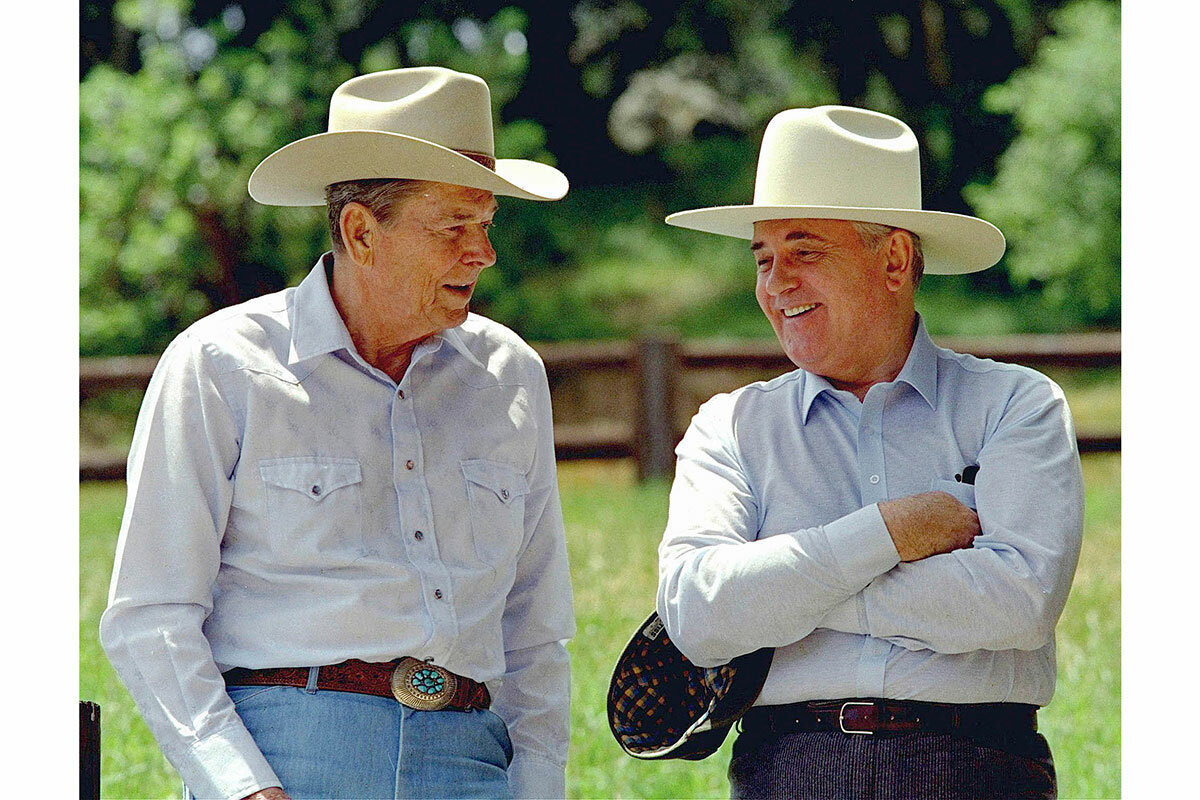

Mr. Gorbachev will be best remembered in the West as the Soviet leader who broke the Communist mold. His radical agenda of glasnost and perestroika upended long-held preconceptions about the Soviet Union and convinced even a hardened cold warrior such as U.S. President Ronald Reagan that the time had arrived to fashion a lasting peace with Moscow.

In a series of stunning diplomatic breakthroughs between 1986 and 1990, Mr. Reagan and his successor George H. W. Bush engaged with Mr. Gorbachev to end the Cold War, slash the nuclear weapons arsenals of both sides, peacefully dismantle Communist rule in Eastern Europe, and negotiate the orderly reunification of long-divided Germany. Separately, Mr. Gorbachev ended the USSR’s decade-long war in Afghanistan, and brought the troops home.

His reputation in his native Russia has been more controversial. Public opinion polls were consistently unkind to him after he left office. Mr. Gorbachev had set out to reform the Soviet system, not to destroy it, and many of his compatriots will never forgive him for that huge miscalculation.

“Gorbachev proved incapable of reforming the Communist system effectively, as they did in China, and so his leadership turned out to be a wonderful gift to the West and a curse for the Russian people,” says Viktor Baranets, former spokesman for the Russian Defense Ministry, now a military columnist. “So I, and very many others, will always regard him as the undertaker who buried our great army and the Soviet state.”

But few will deny that, when faced with the choice of using brute force to hang onto power or allowing the USSR to collapse peacefully, he decisively chose the latter. The alternative might have been a bloody, Yugoslav-style civil war, but Mr. Gorbachev’s unyielding adherence to his principles prevented that.

A believer in the better side of human nature

In a Nobel lecture after winning the 1990 Peace Prize for his role in nuclear disarmament, Mr. Gorbachev spelled out his core personal beliefs. “Peace is not unity in similarity but unity in diversity, in the comparison and conciliation of differences. And, ideally, peace means the absence of violence. It is an ethical value,” he said.

When Communist hardliners staged a coup in August 1991, their first step was to imprison Mr. Gorbachev. Popular pressure defeated the coup attempt, and also swung the mood of the country against any continuation of the Soviet Union. Gorbachev bowed to that historic reality, with considerable grace, in his resignation speech near the end of 1991. The red hammer-and-sickle flag was pulled down from the Kremlin for the last time.

“I believe it’s a good thing for a country to be headed by a romantic, at least from time to time,” says Alexei Simonov, head of the Glasnost Foundation, a media freedom watchdog, who knew Mr. Gorbachev for many years. “Gorbachev always believed in the better side of human nature, in kindness and compassion. Those are unusual traits in a national leader, they did not work to his advantage, and many people still cannot understand him. But he showed great courage at a critical moment, when he did not give certain orders to his military and security machines, and he put his trust in the people to do the right thing instead. Of course, that’s why many still say he was a failure as a leader.”

A lonely voice

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev was born to a peasant family in the southern Russian territory of Stavropol, near the Black Sea, in 1931. Like many in that region, the family was half-Ukrainian. His childhood was turbulent, marked by waves of extreme hardship, including famine, an often-violent struggle waged by the Communists to force the peasantry into collective farms, and the Stalinist purges that saw both his grandfathers hauled away to prison camps.

But those early traumas may have left Mr. Gorbachev with a deeper perspective and informed his future zeal to make the world a better place. “We are right to think of Gorbachev as a world-scale historical figure,” says Nikolai Svanidze, a historian. “He acquired great wisdom in his life and he used it as best he could; he did not try to oppose the winds of history.”

During the 1950’ he studied law at Moscow University, joined the Communist Party, and met and married the woman whom he would describe as the greatest influence on his life, Raisa Titarenko, a philosophy student who later acquired a degree in sociology. In his 1987 book, “Perestroika,” Mr. Gorbachev said that it was his wife’s studies of the gritty realities of Soviet life, as opposed to the high-flown precepts of Marxism-Leninism, that guided him as he sought to work out a reform program that, he hoped, would correct the dysfunctions of the Soviet system and help to realize the positive, humane potential he saw in socialism.

After graduating from university in 1955, Mr. Gorbachev returned to his native Stavropol, where he began a long climb through Communist Party ranks. By all accounts he was an energetic, capable young man, with fresh ideas that were always presented as achievable within the existing system. In 1970 he reached the pinnacle of local politics, being appointed as First Secretary, or party chief, of the Stavropol territory.

That job automatically accorded him a place on the Central Committee, the Soviet Communist Party’s top body, in Moscow. He rose quickly there too during the 1970s, increasingly regarded as the coming man at a time of gerontocratic leadership, typified by the aging and sometimes doddering Leonid Brezhnev, that Russians still recall as the “era of stagnation.”

In March 1985, Gorbachev finally got the top job. The brief, turbulent years that Mr. Gorbachev occupied the Kremlin changed Russia and the world forever. But Mr. Gorbachev outlasted by decades the country he had led to its bitter end.

Often a lonely voice urging Russians not to forget the achievements of glasnost and perestroika, he first embraced the rise of Vladimir Putin, then turned critical over the erosion of democratic rights and humane values that he perceived occurring in Putin-era Russia. He also soured on relations with the West, particularly the United States, which he blamed for expanding NATO into the former Soviet sphere and undermining the hard-won arms control treaties that had ended the Cold War and curbed the threat of nuclear war.

His premonitions about the danger that deteriorating East-West relations would lead to war and fresh divisions seem to have been borne out amid today’s mutual hostility and Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Indeed, Mr. Gorbachev’s hopes for a peaceful new world order, eloquently expressed in his Nobel speech, will stand as a stark reminder of all that remains to be realized.

“All members of the world community should resolutely discard old stereotypes and motivations nurtured by the Cold War, and give up the habit of seeking each other’s weak spots and exploiting them in their own interests,” he said.

“We have to respect the peculiarities and differences which will always exist,” he went on. “This is an incentive to study each other, to engage in exchanges, a prerequisite for the growth of mutual trust. For knowledge and trust are the foundations of a new world order.”

The Explainer

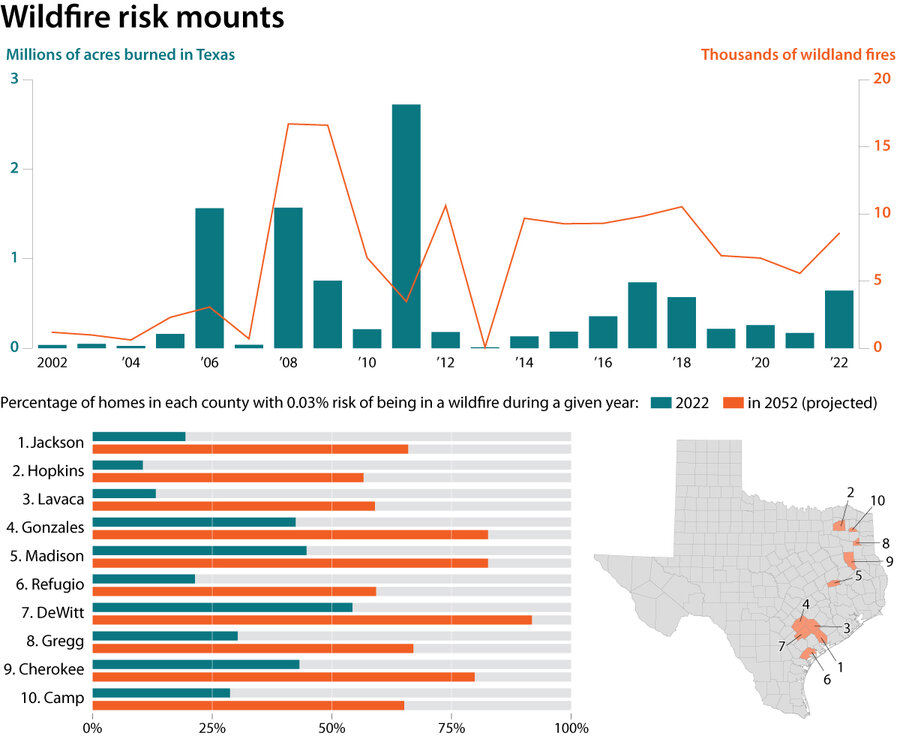

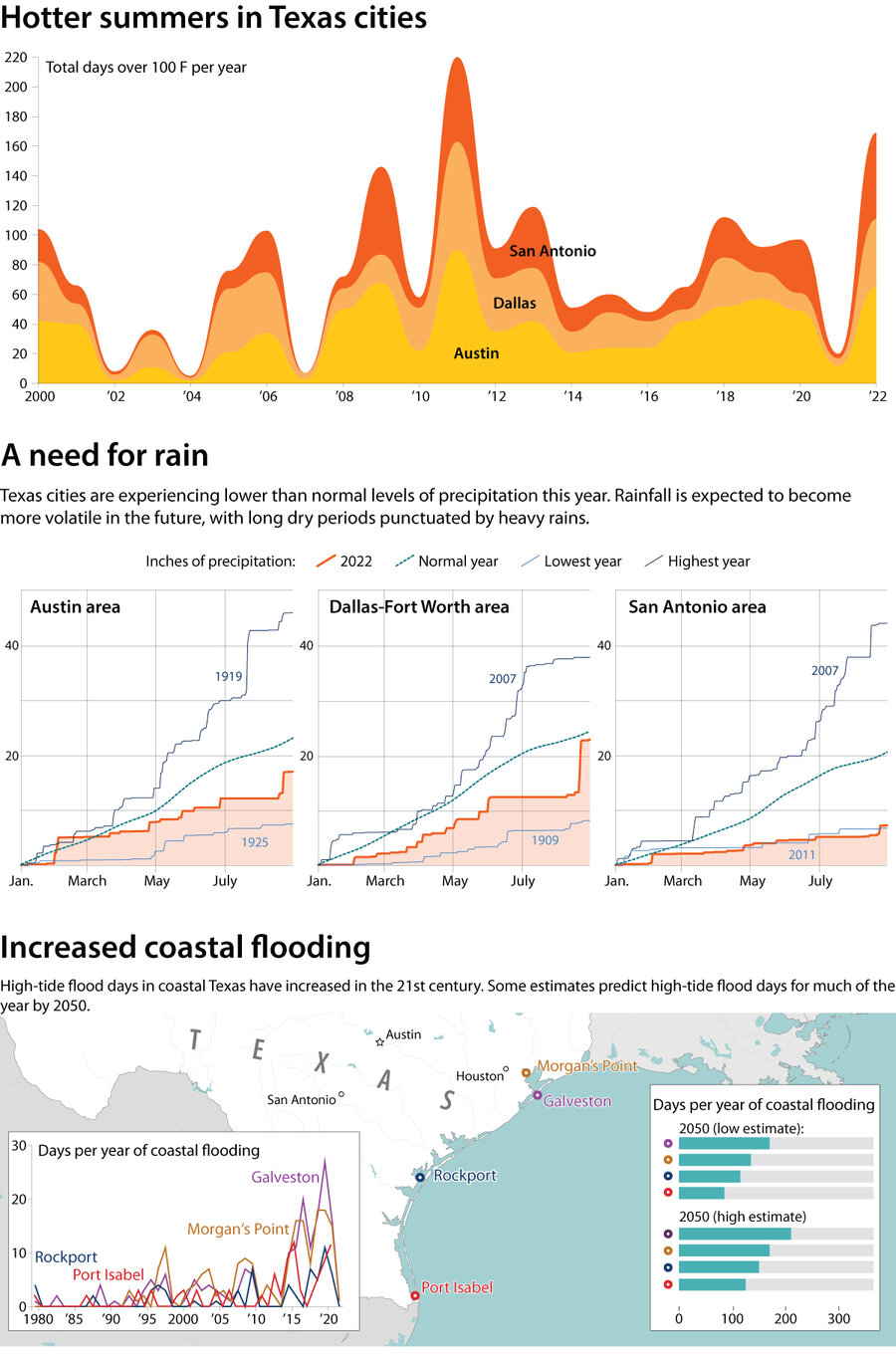

Heat. Drought. Fires. Floods. Texas grapples with a new era.

While climate change has not been a top political concern in Texas, it is increasingly emblematic of America’s climate change experience. From heat to damaging rains, this summer looks like a pivot point.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

-

Xander Peters Special correspondent

This summer, Texas is feeling effects of climate change like never before.

Almost every corner has been experiencing extreme heat, and, until recently, often no rain. These patterns of heat and drought aren’t limited to Texas, but the trends here are noteworthy. The Lone Star State ranks second only to California in population and is among the fastest growing states. It’s a linchpin of the U.S. economy, from energy to tech. And as a solidly Republican red state, it’s a place where evolving views toward climate could have outsize political effects.

Already attitudes have been shifting. The share of Texans who believe climate change is currently harming people in the United States has risen from 50% in 2018 (slightly below the national average) to 60% last year (just above the national average), according to Yale Climate Opinion Maps.

This summer may be a preview of what scientists say could become normal conditions for the state. By 2036, there will be nearly twice as many 100-degree days as there are today, according to one study. Droughts are expected to become more severe, as are extreme rainfall events.

In the face of these challenges, Texans are demonstrating resiliency and innovation – from connecting local water services to cooperating with a nationwide wildfire response network.

Heat. Drought. Fires. Floods. Texas grapples with a new era.

When engineer Manuel Gonzalez moved back to his hometown of Zapata 20 years ago, the Texas community was in a major local drought. “It was their challenge [then]. It’s my challenge now,” he says.

Standing by the reservoir that serves as the town’s only water source, he shows the modest solution he’s been helping to build: A small structure of mud and rock, stretching a few feet into the Rio Grande-fed Falcon Lake Reservoir. At its edge he can pick up cellphone service from Mexico. More important, from it county pumps can access 15 feet of water – compared to 3 feet near the shoreline.

His effort is part of a transformation underway in a state that is feeling effects of climate change like never before.

Almost every corner of the state has been experiencing extreme heat, and, until recently, often no rain too. These patterns of heat and drought aren’t limited to Texas, but the trends here are noteworthy. The Lone Star State, after all, ranks second only to California in population and is among the fastest growing states. It’s a linchpin of the U.S. economy, from energy to tech. And as a solidly Republican red state, it’s a place where evolving views toward climate could have outsize political effects.

Already attitudes have been shifting. The share of Texans who believe climate change is currently harming people in the United States has risen from 50% in 2018 (slightly below the national average in that year) to 60% last year (just above the national average), according to Yale Climate Opinion Maps.

This summer may be a preview of what scientists say could become normal conditions for the state. By 2036, Texas’ bicentennial year, there will be nearly twice as many 100-degree days as there are today, according to a study last year by Texas A&M University and Texas 2036, a nonprofit, nonpartisan policy organization in the state. Droughts are expected to become more severe, as are extreme rainfall events. Meanwhile, population growth is projected to accelerate.

National Weather Service

But in the face of these challenges, Texans have been demonstrating resiliency and innovation. From connecting local water services, to adapting the state’s water plan, to cooperating with a nationwide wildfire response network, the state is working to adapt to, and prepare for, a climate change-altered future.

Responding to severe drought

For almost a year, almost all of Texas has been in drought conditions, much of it extreme. In mid-August, 99% of the state was experiencing “abnormally dry” conditions, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, with over 97% experiencing the two most severe categories of drought. If the drought persists, experts say it may rival 2011, the worst single-year drought recorded in state history.

In Zapata, the community of 14,000 has been caught between the Texas drought and a decadeslong drought in northern Mexico. Now the old Highway 83 is visible, 70 years after it was submerged by the Falcon Lake Reservoir.

The structure Mr. Gonzalez helped build is just one solution. The community has also interconnected four local water providers so they can share resources. In early August, they announced an agreement between U.S. and Mexican officials to dredge sections of the reservoir and increase water depth.

And Mr. Gonzalez, who runs a private engineering firm in south Texas, has been commissioned by the county to study potential secondary sources of water, including reusing wastewater. “We’re not there yet, but we are starting to look.”

That seems to be the trend. The 2011 drought was thought to be the kind you get twice a century.

“We’re having a drought [now] that looks very similar a mere 10 years after that 2011 drought,” says Robert Mace, a professor at Texas State University and executive director of the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment, in an interview earlier this month.

“We’ll be seeing drought conditions become a new normal for the state.”

Triple-digit temperatures on the rise

Heat and drought go hand in hand. As surface temperature increases, so does evaporation, and soil and foliage struggle to retain moisture.

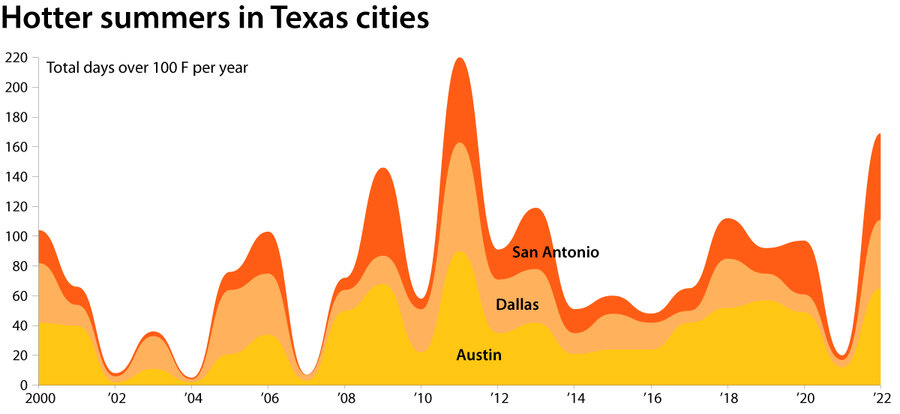

The extreme heat this summer has been especially keen in Texas’ major cities. Both Austin and San Antonio had their hottest May on record, followed by their hottest June on record, followed by their hottest July on record.

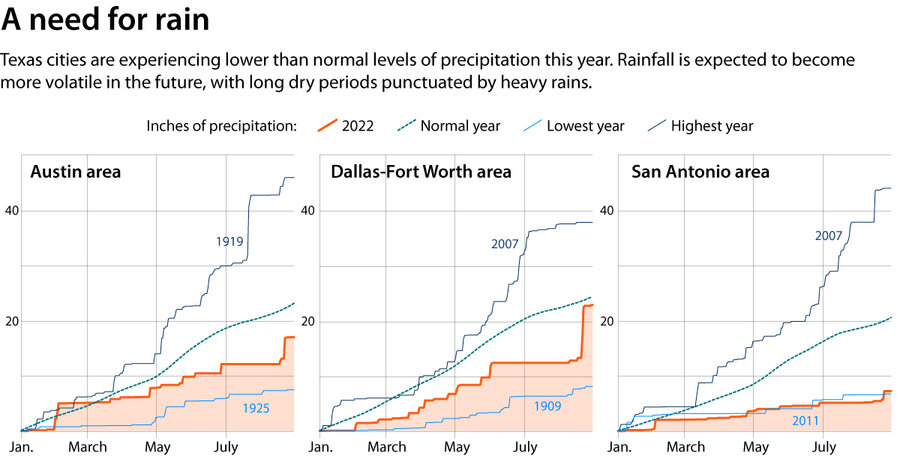

Simultaneously, there has been very little rain. San Antonio is experiencing its worst year on record for rainfall. The Austin and Dallas areas went 52 and 67 days, respectively, without rain between June and August.

This is partly due to an ongoing climate pattern known as La Niña. This cyclical pattern sees cooler than normal surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific Ocean push rainfall and cooler temperatures away from the southern U.S. While this La Niña has been relatively mild, according to Dr. Mace, it has also been long – projected to last for a rare third consecutive winter.

It’s unclear how climate change will affect La Niña, but it’s “very likely” that rainfall variability will significantly increase in the latter half of this century, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2021 report. This summer Texas has had a preview of what that could look like.

A few weeks after snapping its 67-day rainless streak, Dallas experienced what’s been called a “one-in-a-thousand-year” flooding event. Over 9 inches of rain fell in 24 hours – more rain than the area typically sees in a whole summer – and caused as much as $6 billion in damages, according to an estimate from AccuWeather.

National Weather Service

The Texas 2036 report on future climate changes in the state “not only pointed to increased future drought severity, but paradoxically a likely increase in future flood events,” says Jeremy Mazur, senior policy adviser on natural resources at Texas 2036.

The state’s surface temperature is predicted to be 3 degrees hotter by 2036, he adds. “What we’ll [then be] seeing is stronger peaks and longer valleys with regards to rainfall.”

Wildfires get harder to contain

One area where Texas – and the country – has shown great resilience and resourcefulness is in combating the growing threat of wildfire.

No two fire seasons are the same, but this year’s has been the busiest for Texas since 2011, with over 8,800 wildfires burning over 630,000 acres across the state. And risks are projected to grow as the state becomes hotter and more populated.

Assistance from thousands of firefighters from around the state and country, coordinated through a national interagency network, has helped minimize the recent damage.

Earlier this month, 56 of those firefighters gathered near Smithville, an hour west of Austin, to prepare for another day fighting the 700-acre Pine Pond Fire.

The previous day brought the county’s first significant rain in 52 days, but because it has been so dry, firefighters spend the morning patrolling fire lines for hazards that could reignite. They drive or walk over the charred landscape looking for “snags” – dead, standing trees that could be smoldering on the inside – and sniffing the air for “new” smoke (more pungent than “old” smoke).

Around noon, as the sun begins to pierce the clouds, four men from the Nacogdoches Fire Department hack their way toward a smoking log deep inside a section of unburned trees, surrounded by dry pine needles and leaves. It’s this kind of hazard they’ve been extinguishing all morning.

The men primarily fight structure fires, but in a normal year they go on one to three wildland fire deployments. This year they’ve had one or two deployments each month. They make short work of the log – scraping off the ash and dousing it in water – and head back out to look for the next problem.

First Street Foundation's 5th National Risk Assessment, National Interagency Fire Center, Austin American-Statesman

Wildfires “are becoming more problematic to try to keep within the [containment] line,” says Steve Willingham, a resource specialist with the Texas A&M Forest Service and the senior incident commander for the Pine Pond Fire.

Yet wildfire response shows that statewide resources – nationwide resources, even – can be harnessed effectively when there’s a will to do so. “It keeps guys alive,” says Mr. Willingham. “It keeps people safe.”

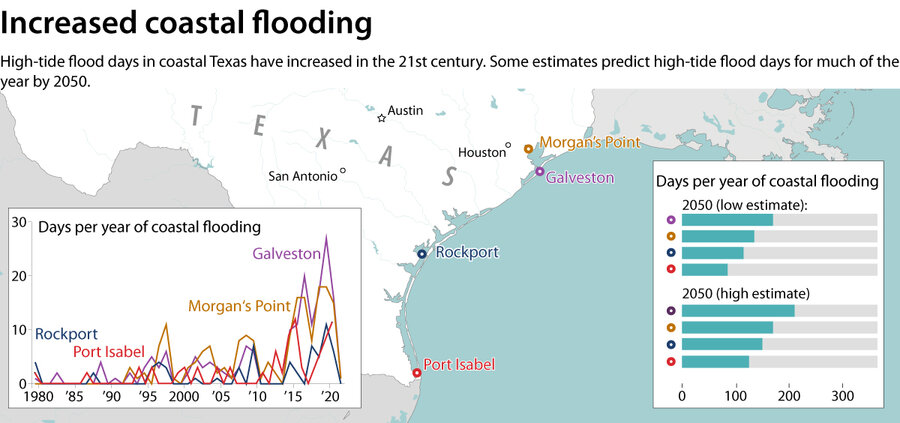

Floodwaters and new defenses

The hope for rain varies by region in Texas. Travel east from dry Central Texas to the Gulf Coast’s emerald-green waters and it’s the persistent threat of flooding that grips researchers attempting to better understand the region’s future.

In August 2017, Hurricane Harvey dumped trillions of gallons of rainfall across metropolitan Houston and rural southeast Texas. The storm amounted to the second-costliest natural disaster in U.S. history, with $125 billion in damages – and a 2020 study in the journal Climate Change estimated that at least $30 billion of that was “attributable to the human influence on climate.”

It’s not just changes in the atmosphere that make climate change costly. It’s also the built environment, says Samuel Brody, a professor at Texas A&M University at Galveston and the director of the Institute for a Disaster Resilient Texas.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Focusing on the forces of nature, he says, “misses the whole idea of parking lots and rooftops and roadways and all this runoff we’re creating in downstream communities.”

In response, the institute recently launched a state-funded two-year project called Digital Risk Infrastructure Program, or DRIP. It partners with underserved Texas communities to solve flooding problems through data and analytical techniques.

The upshot: Communities like tiny Premont (an early DRIP partner, population 2,500) tell their flood stories, which inform the project’s solutions for mitigating future risks.

Among the state’s needs is defending against rising seas as well as heavier rains. Most ambitious among Texas climate-adaptation proposals is the proposed Dutch-inspired “Ike Dike,” named after the devastating 2008 hurricane that wiped out roughly 60% of structures on nearby Bolivar Peninsula and threatened Houston-area transportation routes. It was recently approved by Congress but funding remains to be approved.

Even if the dike system is built, big risks would remain. Galveston Island for example is gradually sinking even as sea levels also rise. Twenty years ago, Galveston witnessed roughly three annual high-tide flood days; last year, there were 14. By 2050, the island is projected to experience 170 such events per year, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“Nuisance flooding is going to start shutting down businesses,” says Bill Merrell, a marine sciences professor at Texas A&M University at Galveston, also a planner behind the Ike Dike. “If a parking lot’s occupied a third of the year with water, you’re not going to be able to function. You’ll have to adapt in some way.”

National Weather Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

In Canada’s language debate, a turn toward inclusion?

French language laws in Quebec are controversial. But new legislation might offer a chance to move beyond traditional positions and fit minority language protection into Canada’s ideal of inclusion.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Laws protecting and promoting the French language in the Canadian province of Quebec have always been controversial. The latest regulations, requiring all immigrants to Quebec to learn French within six months, are no exception.

Quebecois are worried, even after nearly half a century of government efforts. Nearly 70% of them feel that their language is still under threat, and the use of French at home is declining, official figures released this month show.

But some see the new law as an opportunity to move beyond the traditional zero-sum, defensive attitudes that have long shaped the debate over language in Canada, and to find ways of fitting the protection of a minority language into the country’s larger ideals of inclusion.

By bringing new people into the French-speaking community, the laws increase Francophone diversity in a country where diversity is highly prized, points out Andrew Parkin, a pollster. That should please even Anglophones.

And in a country that is bilingual by law, says Richard Marcoux, an academic who studies the Francophone world, Quebec is the most Canadian province in the Confederation simply because it is the most bilingual.

“It’s crucial to protect the language,” says Rodrigue Gagné, a retired lumber worker in L’Anse-Saint-Jean.

In Canada’s language debate, a turn toward inclusion?

On a dazzling Sunday morning, this small town tucked into a glacial valley begins to stir. Kayakers launch their boats into the fjord, and locals take morning walks along country streets dotted with flower-potted front porches.

Here, deep in the heart of rural Quebec, hardly a word of English is heard. It’s the last place – in a province where French is the only official language – that you would think Louisiana-style Anglicization posed a threat, as politicians here warned recently.

Yet resident Manon Lortie, who works at a dockside office selling whale-watching cruises to the St. Lawrence estuary, is always worried about the French language. Every effort to defend her mother tongue is worth it, because “if our language is not protected, English will take its place,” she says.

The provincial government shares her concerns. At the end of May it passed Loi 96, a package of measures to further strengthen official support for the use of French in public life and business.

The legislation has proved controversial, both within and outside Quebec. At the bustling waterside Café du Quai, serving Breton crepes and cider, 20-something waitress Corinne Lareau has her doubts. “I think people are so worried about losing French that they want to control every aspect of it,” she says. “And I don’t think forcing people is the best way to make them want to learn.”

But some see the new law as an opportunity to move beyond the traditional zero-sum, defensive attitudes that have long shaped the debate over language in Canada, and to find ways of fitting the protection of a minority language into the country’s larger ideals of inclusion.

“We need to change the paradigm,” argues Richard Marcoux, who studies the worldwide Francophone community from his demographic observatory at the University of Laval in Quebec City.

More French, more Canadian

Language laws here date back to the 1970s and have always been politically explosive. But obliging people who move to Quebec to learn French have actually made the province more “Canadian,” says Andrew Parkin, who directs the Environics Institute, which recently surveyed national sentiment on the language issue. By bringing new people into the French-speaking community, such laws increase Francophone diversity in a country where diversity is highly prized.

Laws promoting the use of French have “made the experience of growing up in Quebec for Francophones more like the experience of growing up in Toronto or Vancouver,” he says. And in a country that is bilingual by law, Quebec is the most Canadian province in the Confederation simply because it is the most bilingual, adds Dr. Marcoux.

Yet French is in decline across Canada. Data released this month by Statistics Canada showed a continued drop in the proportion of Quebecois who predominantly speak French at home, from 79% in 2016 to 77.5%.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called the finding “extremely troubling.”

After introducing Bill 96 to the provincial parliament, Quebec Premier Francois Legault warned that without more support for the French language it would be “only a matter of time” before Quebec resembled Louisiana, where only a small fraction of inhabitants speak French, the state’s original language.

Most Quebecois agree with him. Dr. Parkin’s survey found that nearly 70% of them, more even than at the height of the separatist movement in Quebec, say their language is under threat. And the new census figures reveal that in a multicultural city such as Montreal only 58.4% of the population use French as their first official language, while immigration has boosted the number of citizens whose mother tongue is neither French nor English.

“It’s crucial to protect the language,” says L’Anse-Saint-Jean native Rodrigue Gagné, a retired lumber worker walking across his town’s pretty covered bridge.

An extra burden?

Loi 96 stipulates that all immigrants to Quebec should speak French within six months, and that they will thenceforth be treated as if they do so. Critics, who include the province’s Anglophone minority and Indigenous groups, call the law discriminatory. The new rules also extend the requirement that Quebec-based businesses should operate primarily in French to all companies with more than 25 employees.

The law has generated considerable backlash, including an open letter from dozens of tech sector CEOs who complained that just when skilled talent is scarce, “bringing newcomers to Quebec is more difficult under the requirements of the new language law,” and that obliging firms to operate primarily in French is “an extra burden” on companies working internationally.

The business leaders added, however, that they “support the spirit of Quebec’s language law – protecting our distinct Francophone identity.”

That was a necessary diplomatic rider: Last year, when the CEO of Air Canada, Michael Rousseau, gave a speech almost entirely in English and later told reporters that he had lived for 14 years in Montreal without needing to learn French, he sparked an outcry, reminding Quebecois of the Anglophone dominance in the city before the language laws were put in place.

“We are a country of two languages, but it seems it’s not easy for everyone,” says Ms. Lortie, who is originally from outside Montreal. She sees nothing anti-immigrant about stricter French language requirements for immigrants to Quebec, mirroring the expectation that people who move to Ontario will learn English.

In Ontario, and other predominantly English-speaking provinces, there is a sense that French and bilingualism are thriving in Quebec and that further regulation is unnecessary. That is not how most Quebecois see things, though.

“When you’re in the minority position, you’re never done,” says Dr. Parkin. And in Quebec, people think that “things are only good now because all these protections are in place.”

But for Dr. Marcoux, looking at the future of the French language in the world, it is time for Quebecois to abandon their defensive posture on the language issue, which he says is born of insecurity. Instead, he advocates, they should seek equilibrium between a flourishing French language and the fact of demographic life that Quebec relies on immigration amid declining birthrates.

He has called on his fellow Quebecois to embrace a “new Francophonie” in Quebec that leaves behind historic debates about French-Canadian identity and puts pride in language laws that bring immigrants into the French language.

“We should be proud of these laws,” he says. “And point out that it’s precisely these laws that have ensured that French is a living language spoken across Quebec and that in 2022 we are part of a global community of French speakers from five continents.”

Back in L’Anse-Saint-Jean, waitress Ms. Lareau is “confident that French will survive. It’s still a beautiful language,” she says. “And I see people from everywhere trying to learn it and just making an effort.”

Essay

Tales from either side of the till

Commerce isn’t just about buying and selling stuff. Kindness can be a part of every transaction.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Joan Donaldson Contributor

-

Sue Wunder Contributor

Food shopping often requires patience. For our two essayists – one in the United States, the other in Switzerland – this is a feature rather than a bug.

During pick-your-own blueberry season, Joan Donaldson hauls an old-fashioned butcher’s scale onto her check-in station. It’s not as fast as sister-in-law Sally’s electronic scale. “When I set a bucket of blueberries on it, the scale bounces a bit before it stabilizes,” Joan writes. ”During the wait, conversations begin.”

Children are captivated. Grandparents reminisce. And Joan relishes each moment of connection.

Another scene of spontaneous connection unfolds half a world away as Sue Wunder encounters a snag at the checkout counter. Realizing she doesn’t have enough money, a woman at the front of the line removes items one by one to lower her bill.

“The woman turned back to us as she left, embarrassed and apologetic,” Sue writes. “We were honestly sympathetic. But I had no idea just how sympathetic the trio ahead of me were until their turn came. “The woman with the teens asked the cashier to add all the left-behind items to her tab. ... Then the two boys sprinted through the exit with the small bag of groceries.”

Reflecting on the moment, Sue writes, “All it took to witness this flash of collaborative kindness was waiting a little longer in a checkout line.”

Tales from either side of the till

Marketing seminars have taught me that I need to build a brand to promote our farm, but I’ve found that my old-fashioned butcher’s scale is a better tool for connecting with our customers.

Every summer, my husband, John; my sister-in-law Sally; and I erect two pop-up shelters with nylon canvas the same color as our blueberries. We haul in two tables, an old wooden kitchen table as the check-in station and a longer trestle table.

Sally prefers weighing buckets of blueberries on an electronic scale that sits at one end of the trestle table. Her scale has an instant readout, and I hear her occasionally exclaim over this feature all afternoon as she weighs customers’ berries that they’ve picked.

My scale sits at the other end of the table. Although I rely upon my Instant Pot to cook meals quickly, I prefer my heavy white scale with its stainless-steel tray on top. When I set a bucket of blueberries on it, the scale bounces a bit before it stabilizes, and a line stops by the weight. During the wait, conversations begin.

“I haven’t seen a scale like that for decades,” a grandparent exclaims. Then he talks about the butcher shop in his hometown grocery store or visiting a farm stand and watching a similar scale weigh butternut squash. I share my childhood experiences with old-fashioned scales, and we mention the hanging type sometimes found in produce departments. Word by word, a relationship forms between the customer, myself, and our farm.

Children are captivated by my scale. No screens, no buttons to click. On the customer side of the scale is a simple window where kids can follow the bouncing line until it comes to rest at the correct weight. Most children are eager to know if they picked more berries than their siblings or parents did, so I weigh each bucket individually to honor their interest. If there is time, I show them how they can read upward along a grid on a poster to find out how much 2 pounds of blueberries used to cost, long ago.

Families with more buckets take longer to weigh in, and conversations may wander to how their gardens are growing. They might also ask me to identify a particular bird or spider. Usually, no one is in a rush. Coming to pick fruit is a form of entertainment. Families want to forget about text messages and TikTok, at least for a while.

Visitors to the farm seem happy to be, as one customer’s T-shirt put it, “Unplugged.” For an hour or so, they unwind between the rows of highbush blueberries, and listen to the cicadas and the crows. And then they weigh in, watching my butcher’s scale bounce with their buckets of berries and adding the weight of their appreciation for the farm I love.

– Joan Donaldson

A charitable conspiracy unfolds in a checkout line

We’ve all been there: in a checkout line with a cart or basket of a few groceries, cash or credit card poised, perhaps with only one or two customers ahead of us. And so it was today for me at a store a mile or so from my home near Basel, Switzerland.

I had three items. A woman and two teenage boys ahead of me had maybe a half-dozen. The customer at the register, a delicate, white-haired woman, had already begun to bag her goods and was holding out cash to pay for them.

Then came the snag. Sometimes it’s a customer with multiple coupons, or someone who forgot to weigh a piece of fruit (this is the customer’s responsibility in European groceries), or someone searching for exact change. Fair enough. One waits.

But today, it was something else. For whatever reason, this woman didn’t have enough money. And so she began the process of choosing which items to keep and which to hand back to the cashier for re-shelving. She paused over each one before keeping or relinquishing it.

We waited. Longer lines surged ahead. I thought maybe I’d shop some more, or join a different line. Instead, I stayed.

The process went on and on. Outside, my bus came and went. Finally in the black, the woman turned back to us as she left, embarrassed and apologetic. We waved off her chagrin. It could happen to anyone. We were honestly sympathetic.

But I had no idea just how sympathetic the trio ahead of me were until their turn came. The woman with the teens asked the cashier to add all the left-behind items to her tab as quickly as possible. The cashier swung into action. Then the two boys sprinted through the exit with the small bag of groceries.

When they returned it was clear their mission had been accomplished.

“Das war sehr Hubsch!” (That was very nice!), I offered. Now they seemed embarrassed, too.

All it took to witness this flash of collaborative kindness was waiting a little longer in a checkout line. I could have caught the next bus. But I felt so light on my feet that I walked home instead.

– Sue Wunder

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A new war doctrine on innocence abroad

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

American soldiers will soon receive new marching orders. Last week, the Pentagon released an “action plan” that, in the words of Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, will help ensure that the protection of noncombatants in a conflict becomes “a strategic priority as well as a moral imperative.”

In other words, as members of the world’s most powerful fighting force, U.S. military personnel on the front lines will be trained on how to better protect the most powerless people in a conflict: innocent civilians.

The moral part is this: The innocence of those not directly participating in a war is a value unto itself – one as important as military victory. The United States has learned the hard way, in Afghanistan and elsewhere, that it must respect a rising global norm for civilian protection in order to achieve its combat aims, such as winning support from people in a foreign land.

Under the plan, the Pentagon will, for the first time, dedicate staff members – about 150 – toward preventing and reporting on both intentional and unintentional harm to civilians in conflicts.

A new war doctrine on innocence abroad

American soldiers will soon receive new marching orders. Last week, the Pentagon released an “action plan” that, in the words of Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, will help ensure that the protection of noncombatants in a conflict becomes “a strategic priority as well as a moral imperative.”

In other words, as members of the world’s most powerful fighting force, U.S. military personnel on the front lines will be trained on how to better protect the most powerless people in a conflict: innocent civilians.

The moral part is this: The innocence of those not directly participating in a war is a value unto itself – one as important as military victory. The United States has learned the hard way, in Afghanistan and elsewhere, that it must respect a rising global norm for civilian protection in order to achieve its combat aims, such as winning support from people in a foreign land.

“Hard-earned tactical and operational successes may ultimately end in strategic failure if care is not taken to protect the civilian environment as much as the situation allows,” reads the Pentagon report, the Civilian Harm Mitigation and Response Action Plan.

Under the plan, the Pentagon will, for the first time, dedicate staff members – about 150 – toward preventing and reporting on both intentional and unintentional harm to civilians in conflicts. While the U.S. has taken such tragedies into account in the past, “it’s just trying to apply a consistent approach across the department so that this becomes a matter of how we do business,” a Pentagon spokesperson said.

At the soldier level, that means training to avoid what is called “confirmation bias,” or clinging to certain beliefs about a potential targeting situation or disregarding contradictory facts. Such bias was cited in a Pentagon investigation of a U.S. drone strike in Kabul last year that killed 10 Afghan civilians – three men and seven children. That mistake helped push Secretary Austin to order the new plan.

To protect noncombatants, according to the International Committee of the Red Cross, armed forces must be encouraged “to internalize the values” of humanitarian law, such as the Geneva Conventions, that aim to limit the scope of war, especially the killing of civilians.

The key to improving such laws, writes scholar David Traven at California State University, Fullerton in a 2021 book, “lies in using our abilities for perspective-taking and empathy.” Such values must be practiced by “average citizens,” he adds, while governments should use war tactics that they “could rationally accept being used against their own civilian population.”

This golden rule approach to civilian protection is “relatively universal” across cultures and history, he writes. Respect for the moral autonomy and rights of civilians in conflict requires a military to ensure “a more equitable distribution of risks between their armed forces in the field (and in the air) and the civilian population.”

For soldiers, a reverence for innocent life during war takes practice. “We need to change how we think about the ethics of killing in war,” Dr. Traven concludes. And if the Pentagon fulfills the promise in its new plan, it will be thinking right along with him.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The healing all-presence of God

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

Getting to know God, divine Spirit, as the ever-present source of all that’s good and true is a powerful starting point for prayer that heals.

The healing all-presence of God

A friend of mine had been suffering from a debilitating fever and couldn’t do anything for herself. When I learned of this, a particular line from the Bible’s book of Psalms sprang into my thoughts: “God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble” (46:1).

The word “present” stood out to me, and I recognized that the time was ripe for examining this concept more deeply. It might have been tempting to think, “Yes, God is present in a general sense, but is missing from the location of my friend.” Instead, my prayer began with a humble acceptance of something I’ve learned through my study and practice of Christian Science: that this “very present help” that is God, divine Spirit, truly is the entirety of existence – is All.

In other words, it’s not that God is with us in a physical context. We couldn’t divide the whole material universe into cubes and find God physically in each one. Rather, it’s that divine Spirit itself is actually the entire source of existence. This existence isn’t physical at all. It’s entirely spiritual – and detailed, perfect, and infinitely substantial. As Christ Jesus put it, “The kingdom of heaven is at hand” (Matthew 4:17).

Taking our exploration of God’s ever-presence even further, the allness of God, who is supremely good, naturally precludes even the slightest presence of an opposite. “God, good, being ever present, it follows in divine logic that evil, the suppositional opposite of good, is never present,” states the founder of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, in her pioneering book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” (p. 72). God’s kingdom is the only one that ever was, ever will be, or ever can be present.

And because there is no place where infinite Spirit doesn’t exist, there are no grounds for an evil counterpart to be valid. Divine Spirit and Spirit’s manifestation is all that truly exists. That manifestation includes each of us as a distinctly spiritual and immortal child of God, the flawless expression of God’s timeless nature.

This is because the action of God brings about, in beautiful and all-spanning intricacy, a divinely spiritual creation. Spirit’s offspring aren’t mortal. They are ideas – spiritual ideas that express the perfection and essence of God. Our permanence as God’s spiritual, perfect ideas ensures that we never will be held hostage by time or physicality.

Certainly, this does not always seem to be the case. But an openness to these spiritual facts has practical value. I’ll tell you, the realization that God, Spirit, is All brought me such concrete peace about my friend. And the next morning I learned that she was feeling much better and no longer had a fever. By the following day, she felt completely like herself again.

“Whither shall I go from thy spirit? or whither shall I flee from thy presence?” David asks in Psalms (139:7). Christian Science, based on the teachings and healing ministry of Jesus, has revealed for everyone around the globe how the utter all-presence of God, divine Spirit, is the sum-total basis for existence. Knowing more of God’s nature as absolute and entire results in effective prayer and healing.

What can dethrone a presence that is entire? Nothing at all. This gives us grounds to subjugate and vanquish the notion that omnipresent Spirit has an opponent, and we can always stand confidently on this unalterable truth.

A message of love

Seeking refuge

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Come back tomorrow, the first day of school in Ukraine. Howard LaFranchi has a report on how teachers and children are persevering in learning, despite the war.