- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Driven to the front line by compassion

Noelle Swan

Noelle Swan

Joshua Curry knew little about Ukraine when Russia invaded.

He just knew he had to get there.

The former Navy flight officer had served in the Persian Gulf and had seen firsthand what military conflict can do to civilian life. “I had to get involved and see what impact I could make,” he says in a telephone interview from Kharkiv, Ukraine. “The Ukrainians didn’t ask for this. They didn’t want this. All they want to do is live their lives.”

That compassion drove him to join Task Force Yankee, a loosely organized community of veterans and others who also yearned to offer practical support for Ukrainians. He has since made several trips to the region, first helping Ukrainian refugees in Poland, then helping to outfit soldiers on the front lines with first-aid supplies.

Most recently, Mr. Curry has been in Kharkiv delivering bags of food to families in need. Community groups including the local Rotary Club help to identify where civilians are living in – or more likely, beneath – bombed out buildings.

The day before our phone conversation, he helped deliver 20,000 pounds of food to needy families. He also witnessed a bomb blast that killed five people just a couple hundred feet away. “That’s a daily occurrence here,” he says.

The risks are undeniable. He’s heard stories of volunteers being captured and tortured by Russian forces. Still, he resists the idea that what he is doing is courageous. It’s more a matter of living by his values.

“When you have a family in tears,” Mr. Curry says, “knowing that you’re giving them that push forward that they really need, being able to give them that hope, that’s all I need to keep myself going.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

United front: Understanding China and Russia’s deepening alliance

China’s deepening ties with Russia are likely to grow even stronger in coming years as each country reaps key benefits from the other. Yet historical mistrust and differing global aspirations remain potential weaknesses.

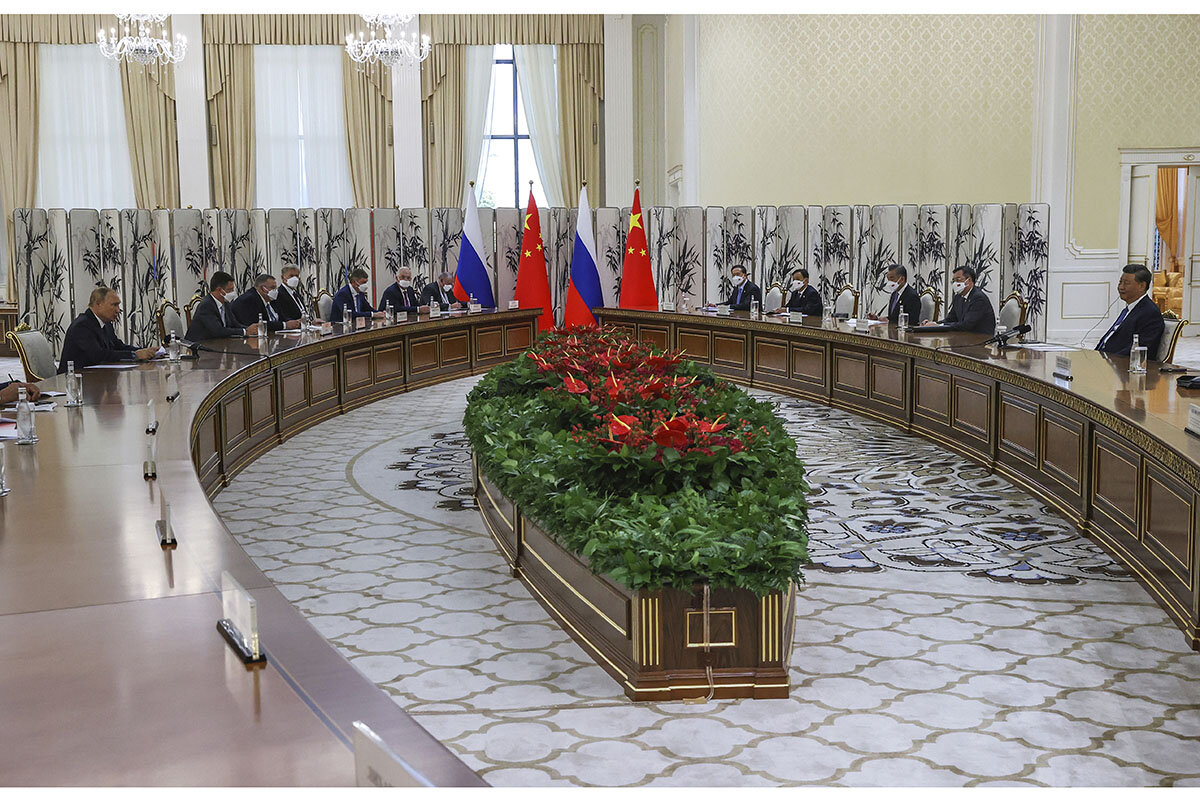

At their first face-to-face meeting since Russia invaded Ukraine, Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin left little doubt that their countries’ “no limits” strategic partnership is here to stay.

Economic ties are growing, as China turns to Russia for energy and food amid global shortages, and military cooperation is also advancing. The countries intend to expand their diplomatic cooperation in multilateral organizations as well as the United Nations Security Council, with Mr. Putin saying last week that China and Russia “jointly stand for forming a just, democratic, and multipolar world.”

The closeness of the leaders’ relationship is “a historical anomaly,” say experts, noting long periods of tension and estrangement in recent centuries. The overarching force pushing China and Russia together now – one unlikely to change anytime soon – is their shared hostility toward the United States and the West.

“They both think about the West as implacably opposed to them as great powers,” says Joseph Torigian, assistant professor at American University’s School of International Service. They’re willing to manage their differences and put aside past grievances to confront that perceived threat.

United front: Understanding China and Russia’s deepening alliance

Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin struck different tones in public remarks last week at their first face-to-face meeting since Russia invaded Ukraine – but left little doubt that their countries’ “no limits” strategic partnership is here to stay.

Despite major Russian battlefield setbacks and Mr. Putin’s mention of China’s “concerns” over Ukraine, the two leaders pledged to deepen strategic cooperation, support each other’s “core interests,” and join forces to promote regional and global stability. On Monday, senior Chinese and Russian leaders followed up with a new round of high-level security consultations.

Mr. Xi’s decision to meet Mr. Putin – during Mr. Xi’s first overseas trip since 2020 and a month before his expected ascent to a rare third term as China’s top leader – underscores the importance he places on the alliance with Russia, experts say. For the embattled Mr. Putin, the relationship with China is increasingly indispensable.

“Russia is the only ally of consequence for China,” says Alexander Korolev, senior lecturer in politics and international relations at the University of New South Wales in Sydney. And for Russia, “China is like a lifeline,” he says.

The overarching force pushing China and Russia together – one unlikely to change anytime soon – is their shared hostility toward the United States and the West, say experts in Sino-Russian relations.

“In both capitals, there’s a view that the big … challenge, the long-term strategic enemy, is the United States,” says Joseph Torigian, assistant professor at American University’s School of International Service.

“They both think about the West as implacably opposed to them as great powers,” he says, and manage their differences so together they can confront that perceived threat.

Shared worldviews

Last February, Messrs. Xi and Putin inked a historic joint statement that created a special relationship between Beijing and Moscow – one with “no forbidden areas of cooperation.” It was designed as a global counterbalance to the U.S.-led system of alliances.

Under the pact, they pledge to support each other’s “core interests” – including China’s claim to the self-governing island of Taiwan, and Russia’s interests in Ukraine and other border regions. Beijing has not condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, instead blaming the conflict on the U.S. and NATO.

In part, the agreement reflected a convergence in the worldviews of Mr. Xi and Mr. Putin, who enjoy strong personal ties built on the 40 one-on-one meetings they’ve had over Mr. Xi’s decade in power, starting with his first foreign trip as China’s top leader in 2013.

“The closeness of the relationship between Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin is a historical anomaly,” says Dr. Torigian.

Mr. Xi drank in Russian culture in the 1950s, when his father, Xi Zhongxun, managed the program under which thousands of advisers and teachers from the Soviet Union arrived to bolster China’s building of communism, he says.

Today, Mr. Xi and Mr. Putin share the views that authoritarian political orders are needed to maintain stability and stave off chaos, that the democratic West is in decline, and that together they can shape the international system to advance their interests.

Increasingly interconnected

Economic ties are growing, as China turns to Russia for energy and food amid global shortages as Russia’s access to world markets is constrained by Western sanctions. Russia in recent months became China’s largest oil supplier, and China's imports of Russian natural gas and coal are also rising. At the same time, Beijing is importing more wheat and other agricultural goods from Russia, having lifted import restrictions on Russian wheat after the invasion of Ukraine.

Military cooperation is also advancing, as China and Russia step up joint military exercises used for both training and signaling, experts say. “They have pretty robust military ties in terms of military exercises,” says Brian Hart, a fellow with the China Power Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“They’ve really used those to great effect, for example, by flying a joint air patrol [near Japan in May] on the day of the Quad summit in Tokyo,” he says, referring to the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue among Australia, Japan, India, and the U.S.

Historically, Russian sales of arms and engines have been critical for China’s military modernization. Moscow is reportedly helping Beijing develop an anti-missile air defense system, says Dr. Korolev. Meanwhile, China makes drones that Russia needs, he says.

Messrs. Xi and Putin also stressed that China and Russia intend to expand their diplomatic cooperation in multilateral organizations as well as the United Nations Security Council.

“We jointly stand for forming a just, democratic, and multipolar world based on international law and the central role of the United Nations,” Mr. Putin said, according to The Associated Press.

Mr. Xi responded that “China is willing to work with Russia to reflect the responsibility of a major country, play a leading role, and inject stability into a troubled and interconnected world,” according to the official Xinhua news service.

Potential pressure points

The united front presented last week doesn’t mean China and Russia have forgotten past grievances and betrayals.

Recent history includes long periods of tension and estrangement between the countries, particularly the decades from 1961 to 1989 known as the “Sino-Soviet split,” when ideological conflicts and territorial disputes put the relationship into a deep freeze. That divide created an opening for the U.S. to establish formal diplomatic relations with the Communist Party-led government in Beijing for the first time in 1979.

Mistrust between the two countries also lingers from past great power competitions between them, which saw imperial Russia as a party to several 19th-century “unequal treaties” that forced China to cede large portions of territory to European countries. Given Russia’s past dominance of China as the more powerful neighbor, some experts say China’s growing economic heft and Russia’s relative dependence could give rise to new conflicts.

Looking ahead, China seeks to maintain its strategic partnership with Russia while avoiding severe reputational costs, but this cost-benefit calculation could change – for example if the Ukraine war severely depletes Russia and further undermines China’s ties with Europe.

“If Russia becomes a major drag on China … or starts to obstruct China’s broader strategic interests, I think you’ll start to see a deterioration of that relationship,” says Mr. Hart of the China Power Project.

However, many experts believe the strategic alignment between Russia and China is unlikely to change fundamentally without a significant improvement in their respective relations with the U.S. and Europe.

“If you see a major easing of U.S.-China tensions, kind of a reversal of the recent trend, you might see less of a desire in Beijing to strengthen relations with Russia,” says Mr. Hart.

Could Ukraine win this war? Answer hinges partly on NATO allies.

Recent military gains underscore Ukraine’s aspirations for victory against Russia's invasion. Achieving that goal may depend on perseverance by NATO allies, too.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Ukraine’s surprising successes in battle are raising a question, at least cautiously: Instead of a protracted war of attrition, can Ukraine hope for turning points toward outright victory, sooner than in the distant future?

The answer may hinge on persistence, not just by Ukraine’s soldiers but also by its allies.

The NATO alliance, for one thing, must sort out its own debates about whether Kyiv should get the kind of heavy-duty armaments that could hasten the war’s end, but could also raise the risk of catastrophic escalation.

While President Joe Biden believes the United States should support and defend Ukraine, some critics see a missed opportunity to do more – to “play to win” by sending more and bigger weaponry. The arms flow from the U.S. already has been “unprecedented,” Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin told a recent gathering in Germany.

Still, a shortage of supplies has been a constant challenge for Ukrainian forces.

If the U.S. and allies show they are ready to persist in helping to supply Ukraine for years, that “hopefully incentivizes Russia to stop fighting and to get down to negotiations,” Colin Kahl, undersecretary of defense for policy, said in a recent Pentagon briefing.

Could Ukraine win this war? Answer hinges partly on NATO allies.

As underdog Ukrainian forces were launching a lightning-strike counteroffensive, for the moment routing their Russian invaders, top military officials from 50 allied nations were mapping out how to bring more weapons – among those they are willing and able to give – to the fight for Kyiv.

A memo outlining “Ukraine’s Urgent Requirements” awaited them as the meeting began. It was a list that ran from the high-tech to the bleakly basic: Rocket launchers were priority No. 1, with artillery and radars rounding out the top three.

Fuel, spare parts, and oil were also among the dire needs.

As they strategized, Ukraine’s minister of defense shared updates of the offensive with U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, who later assured the gathering that Ukrainian soldiers were “putting the military aid that we’ve all been sending them to immediate and effective use.”

From the United States, this has amounted to an “unprecedented” $14.5 billion since the war began, the latest tranche representing the 20th drawdown from U.S. stockpiles.

In the face of Ukraine’s stirring perseverance and frankly surprising success, Pentagon officials are now promising years of supplies to come – which will be relevant, they say, even in the wake of a settlement.

With these developments, talk is cautiously shifting from acceptance of a protracted war of attrition to the possibility of turning points in a time period sooner than the distant future.

The question in the months ahead, analysts say, will be whether U.S. and NATO allies – with populations facing crushing energy costs as winter approaches – can continue to match the resolve shown by Ukrainian soldiers.

The answer hinges in part on sorting out debates within the alliance about whether Kyiv should get the kind of heavy-duty armaments that could hasten the war’s end, but could also raise the risk of catastrophic escalation.

The answer may also hinge on what Russia and President Vladimir Putin do. On Tuesday, officials in Russia-controlled regions of eastern and southern Ukraine said they plan to start voting this week on joining Russia. Were Moscow to annex those areas, attacks on them would be seen by Mr. Putin as an attack on Russia itself.

While President Joe Biden believes the U.S. should “support and defend” Ukraine, “another key goal is to ensure that we do not end up in a circumstance where we’re heading down the road towards a third world war,” national security adviser Jake Sullivan said in July.

Critics of such caution take issue with the ethics of helping Ukraine defend itself rather than “playing to win.” The longer the war drags on, some argue, the more lives are likely to be lost.

President Putin, for his part, is betting that Western resolve will ultimately splinter in the face of such contentious questions.

“His theory of victory is that he can wait everybody out: He can wait the Ukrainians out because they will be exhausted and attrited,” Colin Kahl, undersecretary of defense for policy, said in a recent Pentagon briefing.

“He can wait us out because we’ll turn our attention elsewhere. He can wait the Europeans out because of high energy prices.”

To this end, making it clear that allies will keep the tranches of military aid flowing is “extraordinarily important,” Dr. Kahl argued, in “challenging Putin’s theory of the case – which is that we’re not in it for the long haul.”

In so doing, he added, allies just might be able to more quickly bring Russia to the negotiating table.

Morale-boosting weapons

To date, the influx of weapons has been pivotal not only to the fighting effectiveness of Ukrainian troops, but also to their morale, which is no small matter – famed military strategists from Hannibal to Joan of Arc have long insisted – in enabling outgunned and outnumbered militaries to eke out some stunning victories.

In his own fights, Napoleon had a rough rule of thumb for winning that’s been widely embraced by modern military thinkers: “In war, morale is to the physical as 3 to 1.”

On a recent visit to Ukraine, Rajan Menon, director of the Grand Strategy Program at the Defense Priorities think tank, heard soldiers echo a common refrain: “‘We will prevail, because Russians are invaders. We’re defending our homeland – and by definition we have more morale.’”

Just as Mr. Putin believes the will of the Western coalition will crumble, Ukrainian fighters are sure this is true of the Russians.

“What my Ukrainian friends are absolutely convinced will happen is that little by little, Russians will find it harder and harder to fight this war and will become gradually demoralized,” Dr. Menon says. “So Ukraine ekes out a victory of some sort.”

That said, even the most optimistic Ukrainian commanders figure the fight could go on for three more years, he adds.

“But when they say that, it isn’t followed up by, ‘So we need to settle.’”

Calls to come to the negotiating table, particularly in the midst of an ongoing Ukrainian counteroffensive, present the “practical problem that there’s no negotiation to be had,” says retired Col. Mark Cancian, senior adviser to the International Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“You’d be asking Ukraine to make a deal where they are right now on the front lines, and yes to Russian occupation of 20% of the country at best.”

Still, a shortage of supplies has been a constant challenge for Ukrainian forces even as countries including the U.S. have been taking weapons out of their strategic reserves to give to Kyiv – a move that becomes less popular, and tenable, as stocks run lower.

With this in mind, NATO allies are pledging to mobilize their private sectors with long-term contracts in an effort to ensure a “steady stream of assistance that will stretch out over many months and years,” Dr. Kahl said.

This, in turn, “hopefully incentivizes Russia to stop fighting and to get down to negotiations,” he added.

“If it doesn’t and the fighting continues, then the assistance continues to be relevant. If it does incentivize him to strike a deal, the assistance is still relevant, because Ukraine will have to hedge against the possibility that Russia could do this again.”

Imposing costs on Russia

When asked whether lawmakers would support this aid given the precariousness of the U.S. economy, Secretary Austin expressed optimism in the face of the “broad bipartisan support” to date.

That said, “There’s always an expectation that we are able to lay out the rationale for those requests – and certainly we’ll do that.”

To bolster its case, the administration is arguing that its efforts have already contributed to some not-insignificant wins.

“It’s important to us that Russia pays a cost in excess of benefits they gain from an aggression, so they don’t do it again – and so that other aggressors can take a lesson,” Dr. Kahl said.

“It’s also important to us that Vladimir Putin’s objective of weakening the West and fragmenting NATO actually is turned on its head – that NATO emerges stronger,” he added. “I think we’re on track to achieve ... those objectives.”

As the fighting continues, however, NATO officials are also aware that offensive operations are far more complex than playing defense, and that Russian forces greatly outnumber Ukrainian troops.

Officials in Kyiv have noted these facts in their pleas for more – and bigger – weapons.

In response, the U.S. has increased its military assistance to Ukraine fourfold since April. “We’ve seen Ukraine rightly request help,” Secretary Austin pointed out during the fifth meeting of the Ukraine Defense Contact Group at Ramstein Air Base in Germany. “And a lot of help has been provided.”

But not all of the help. Left unfulfilled are, among other things, Kyiv’s pleas for battle tanks and fighter jets, in part out of concern for Russian reaction to such a move.

That said, “certainly fighter aircraft is something to consider as part of what Ukraine’s requirements would be going forward,” a senior U.S. defense official says.

Indeed, despite charges of not helping Ukraine “play to win,” the U.S. and its NATO allies “have been supplying equipment to Ukraine as fast as they can absorb it,” says Mr. Cancian. And this “has made a huge difference” on the battlefield.

These weapons become even more effective as Ukrainian troops get more training, he adds, as has been the case with the HIMARS artillery rockets, which have been used to “devastating” effect against Russia on the battlefield.

In the meantime, “sending 100 HIMARS to just sit in the parking lot – because troops don’t know how to operate or maintain them – would undermine the bipartisan consensus for supplying equipment if journalists come back with pictures of abandoned U.S. equipment,” Mr. Cancian says.

“You’d hear pushback about, ‘Why are we giving all this equipment when it’s being wasted?’”

To this end, with each passing month, the NATO training of Ukrainian forces continues to expand, including a new basic training program for recent recruits that the United Kingdom has established.

Ian Lesser, executive director of the Brussels office of the German Marshall Fund, expresses confidence that Ukraine's military capability will improve with time.

“It’s not just what’s being given to Ukraine in terms of armaments. It’s also training and intelligence cooperation," he notes, that have been “quite decisive” in the war.

Q&A

Solution for ideological division: Revising the Constitution?

Courts have reduced complex discussions about constitutional rights into zero-sum conflicts, says Professor Jamal Greene. He and other constitutional scholars worked on a project that demonstrated people who disagree on a lot can still cooperate on updating America’s founding document.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Could constitutional rights be a contributing factor in America’s ideological divisions?

That’s the argument made by Jamal Greene, author of “How Rights Went Wrong: Why Our Obsession With Rights Is Tearing America Apart.” Courts have reduced complex discussions about rights into zero-sum conflicts where a constitutional right overrides all other interests, writes the Columbia Law School professor and former clerk for Justice John Paul Stevens.

More recently, he has been involved in the Constitution Drafting Project. Organized by the National Constitution Center, the venture grouped constitutional scholars into ideological “teams” – liberal, libertarian, and conservative – and tasked them with drafting their ideal constitutions.

Of the project, Professor Greene says, “the biggest take-home from the process is that quite a number of people across ideology actually can agree that there are aspects of the Constitution that are in need of revision, and about which revisions would be useful and helpful.” He adds, “It was an object lesson in negotiation, that people from different starting points can get together around something if they’re willing to be open-minded and engage with the arguments and objections made by others.”

Solution for ideological division: Revising the Constitution?

Could constitutional rights be a contributing factor in America’s ideological divisions?

That’s the argument made by Jamal Greene, author of “How Rights Went Wrong: Why Our Obsession With Rights Is Tearing America Apart.” Courts have reduced complex discussions about rights into zero-sum conflicts where a constitutional right overrides all other interests, writes the Columbia Law School professor and former clerk for Justice John Paul Stevens.

More recently, he has been involved in the Constitution Drafting Project. Organized by the National Constitution Center, the venture grouped constitutional scholars into ideological “teams” and tasked them with drafting their ideal constitutions.

Professor Greene spoke with the Monitor about the project, as well as how America can move beyond the current climate of despair and divisiveness toward cooperation. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Could you explain what the Constitution Drafting Project is and why you wanted to be a part of it?

So this is an initiative of the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia that is trying to bring together people who come from different ideological orientations, to see if they can come up with some sensible revisions to the Constitution. The way it was structured was to set up three teams, each with a different ideological orientation – a progressive team, a libertarian team, and a conservative team [Professor Greene was part of the progressive team] – have them work independently to draft their own constitutions, and then see where they agree and where they disagree. That was kind of the first phase of the project. And I don’t know if this was intended from the start, or whether it arose out of the first phase, but the next phase was to have the teams get together and see if they can actually hammer out language in relation to the provisions or the potential amendments that they actually agree about. So that’s what we’ve done. There was a kind of mock constitutional convention in which we got together via Zoom and tried to work out actual constitutional language that all three of these teams could actually agree on.

What have you learned throughout that process?

I think the biggest take-home from the process is that quite a number of people across ideology actually can agree that there are aspects of the Constitution that are in need of revision, and about which revisions would be useful and helpful. We actually agreed on five amendments, some of which would be significant. There was disagreement about the language and exactly around the margins, and people had to make compromises. But it was an object lesson in negotiation, that people from different starting points can get together around something if they’re willing to be open-minded and engage with the arguments and objections made by others.

Can you give more details on that? What were you able to agree on?

One [amendment] would remove the limitation on a president to be a natural-born citizen. Everyone agreed that naturalized citizens should be able to be president, at least if they have lived in the country for a certain length of time. There was a second amendment relating to – and this gets a little bit inside baseball, but it’s quite important – what’s called a legislative veto, which enables the legislature to override an agency regulation without necessarily getting the approval of the president. A third amendment had to do with impeachment. We all agreed to lower the threshold for Senate conviction, but raise the threshold for House impeachment, so that they would both be three-fifths. [Under] the current Constitution the House can impeach with a simple majority, and the Senate requires two-thirds to convict, so we made both of those numbers three-fifths.

A fourth amendment basically imposes 18-year term limits on the Supreme Court, and [a] regularized appointment process so that there are two justices appointed for every presidential term. And then a final amendment that would change Article 5 itself, and change the actual amendment procedure in the Constitution. Right now it requires a two-thirds vote of both houses and three-quarters of the state legislatures. We changed that to a three-fifths vote in both houses and two-thirds of the states – and also an additional possibility of either two-thirds of the states, or states representing three-quarters of the population.

Why did you want to be part of this, and devote time to this? What do you think is the broader significance?

Well, I really do think that the Constitution, which is a very old document – [it] was written for a very different society than what we have today – is in need of significant revision. And I also think that if we are going to revise the document, it needs to be in a way that takes into account the views and commitments of a broad range of people. And it’s also important to show that it’s possible for people who have different views and attitudes and commitments to compromise, to negotiate, and not just yell at each other on social media or cable news. I think this is a good kind of object lesson in how one can actually come to agreement on things that we all can believe in, even if we start from different points. The country could use more examples of people coming to engage in what I think of as genuine politics, which are figuring out how to move forward even though you come from different starting places.

You talk about the current state of our politics. Is that related to our Constitution, and in particular how it’s interpreted right now?

They are related in the sense that one of the basic premises of the book is that we are a very pluralistic, diverse people, and the only way for a pluralistic, diverse people to move forward together as a single society is if they don’t understand themselves to have absolute entitlements against each other that conflict with each other, that they really do need to engage in political conversation. I’m trying to live that by getting together with people I disagree [with] about lots of things. That’s no reason not to try to come together around the things that we can agree on, and also, again, to compromise.

In reality our Constitution is famously difficult to change. You write about how the problem of the 21st century is the problem of the “rights line.” Can you give an example of rights conflicting, and what that’s meant for our politics and our country?

There are lots of examples of it. Abortion rights is a clear example, where there are entrenched sides, both of which understand themselves to be vindicating constitutional rights. Gun rights [and] affirmative action also in a lot of ways take these forms. Lots of conflicts over freedom of speech, between the freedom of the listener or the freedom of the speaker. And we tend to view those conflicts as if the job of the legal decision-maker is to choose one of those rights or the other when they come into conflict, as opposed to trying to mediate between them. And that’s a big part of what the book is about, is some strategies for mediating between rights.

As to how realistic the project is, as an academic, one engages in lots of projects that don’t have an immediate payoff, so in some ways this seems more realistic than some of the things that academics typically do. But I’m not so sure that there’s no practical possibility. It is incredibly difficult to amend the Constitution, but we also have a kind of despair about constitutional amendment, as if there’s just nothing we could possibly agree to. And this project shows that that’s not true. There are things that people could possibly agree to, and just developing some momentum toward that end I think is a productive thing to do.

What do you see as the stakes? The momentum that we have right now, that you’re trying to change, where do you see that heading? Why do you think we need a correction?

I think among the stakes is self-government itself. Governing oneself according to a 200-plus-year-old document that we can’t change means that we, in fact, are not governing ourselves. And so invigorating the idea that we actually have some agency in trying to decide what constitutional rules apply to our society is as important as anything in constitutional law. I’m just one person, but it seems to me that among the things that a single person can do to try to get at that problem, showing that it actually can be done, and then actually going out and doing it and trying to defend it, is among the more productive things one can do in the face of very steep odds. Whether we think of the Constitution as something that we have any power to change, it is the very stakes of self-governance, and I take those very seriously.

Film

Caught on film, a precious ‘Three Minutes’ in 1938 Jewish Poland

How can people bear witness today to events that happened in the past? “Three Minutes: A Lengthening” builds a documentary around a home movie clip featuring a Jewish community shortly before the Holocaust. Reviewer Peter Rainer says of the film, “The result is a metaphysical detective story in which the stakes – the preservation of the memory of a people – could not be higher.”

-

By Peter Rainer Contributor

Caught on film, a precious ‘Three Minutes’ in 1938 Jewish Poland

Thirteen years ago, writer Glenn Kurtz discovered in Palm Beach, Florida, a roll of previously unseen 16 mm footage shot by his deceased grandfather, David Kurtz. The reel turned out to contain three minutes of rare color film of a predominantly Jewish town, Nasielsk, Poland, about 30 miles north of Warsaw. David, who had immigrated years earlier to America, had taken a tour of European capitals in 1938 and, with his newly bought camera, took a side trip to his boyhood village.

The great documentary “Three Minutes: A Lengthening,” directed by Bianca Stigter, opens with those three full minutes. We see the milling townspeople, young and old, some happily waving at the camera, some emerging from synagogue or a market. The effect is extraordinarily moving in part because we know how this will end. As we soon learn, on Dec. 3, 1939, about three months after Germany invaded Poland, the 3,000 or so Jewish inhabitants were rounded up in the town square, summarily beaten, and eventually shipped to the Treblinka death camp. Of that 3,000, fewer than 150 were alive in 1945.

The people in this brief clip, many of them children – the boys horsing around, the girls more decorous in their patterned dresses – are like phantoms reaching out to us across the vales of time. Many in the community had never before seen a movie camera, and, as one Nasielsk survivor tells us in a voice-over, it was regarded as a kind of magic box. Normally the village had its hierarchal divisions, but for the camera, all but the very Orthodox happily assembled and jostled together.

How that Nasielsk survivor was located is indicative of the forensic diligence that informs the narrative, which began as a book by Glenn about his discoveries. Even the faded lettering above a grocery store becomes a talismanic clue of sorts. Glenn initially donated the film to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, where it was restored. (The color red, the last to fade, shows up brightest in the clip). Two years later, a woman contacted him to say that a young boy in the footage was almost certainly her still-alive grandfather, Maurice Chandler, who had survived and immigrated to America. “I recognized myself immediately in that smile,” says Maurice, who was born Moszek Tuchendler, of his 13-year-old self.

Maurice’s memories help decode some of the details of that day. He describes how some of the boys wore caps to show off their independence from those who wore yarmulkes. In quick, resonant sketches, he identifies several of the children and adults. Throughout, Stigter keeps playing and replaying portions of the footage, in slow motion or freeze frame. As the film’s narrator, Helena Bonham Carter, says, “They say one picture is worth a thousand words. But before that phrase makes sense, you need to know what you’re looking at.” The result is a metaphysical detective story in which the stakes – the preservation of the memory of a people – could not be higher.

The film medium has often been discussed in academic terms as a vehicle to contain the passage of time. But “Three Minutes” does much more than that. Although it raises all sorts of issues about the nature of the film image and how it can affect us, it is also the least theoretical of movies. We are bearing witness. These people looking back at us seem both shudderingly close and ineffably far away. Whatever their ages, they are rendered forever young. Their ultimate fate imbues the imagery with an overwhelming poignancy that is almost impossible to comprehend.

Bonham Carter speaks over a present-day shot of the town square – where the Jews were rounded up, and where no memorial lies – and says, “The only thing left is an absence.” I don’t agree. In that absence there will forever be a wail, a prayer. It fills the empty air with its immanence.

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “Three Minutes: A Lengthening” is briefly in theaters and is available on many streaming platforms starting Sept. 20, and will be available on Hulu in December. The film is rated PG for thematic material involving the Holocaust.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Iran’s George Floyd moment

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Iran has seen many mass protests against its ruling clerics but none quite like those in recent days. Since Friday, when a young woman died after being arrested for not wearing proper head covering, Iranians have taken to the streets, Twitter, and Instagram by the millions. Some call it Iran’s George Floyd moment.

The scope of the protests appears to matter less to the regime than a particular point being made – that rules and laws can only be enacted and imposed by a democracy that has civic equality. In Iran’s Islamic Republic, the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, presumes sole authority to rule.

One noted critic, Grand Ayatollah Asadollah Bayat-Zanjani, said the actions of the so-called morality police in abducting those who violate the official dress code are “against the law, against religion, and against logic.” The Quran “clearly prevents the faithful from using force to impose the values they consider religious and moral,” he added.

The regime knows it has a problem. A recent official report said some 60% of women either do not support or regularly wear full “Islamic hijab.” That spirit of equality will be difficult to suppress.

Iran’s George Floyd moment

Iran has seen many mass protests against its ruling clerics but none quite like those in recent days. Since Friday, when a young woman died after being arrested for not wearing proper head covering, Iranians have taken to the streets, Twitter, and Instagram by the millions. Some call it Iran’s George Floyd moment.

Even outside Iran, critics from J.K. Rowling to the United Nations have decried the injustice of the mysterious death as well as Iran’s ever-harsher rules on clothing – some of which apply to men, such as not wearing shorts.

The scope of the protests appears to matter less to the regime than a particular point being made – that rules and laws can only be enacted and imposed by a democracy that has civic equality. In Iran’s Islamic Republic, the supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, presumes sole authority to rule.

The spirit of equality can be seen in the many female protesters who voluntarily choose to wear the mandatory hijab out of their own sense of modesty. One noted critic, Grand Ayatollah Asadollah Bayat-Zanjani, said the actions of the so-called morality police in abducting those who violate the official dress code are “against the law, against religion, and against logic.” The Quran “clearly prevents the faithful from using force to impose the values they consider religious and moral,” he added.

Another critic, Ayatollah Mohaqeq Damad, said the morality police, known as “guiding vigilantes” (Gashteh Ershad), were set up to check the behavior of rulers, “not to crack down on the liberties of the citizens.”

Such high-level assertions of civic freedoms have put the regime on a back foot. The hard-line conservative president, Ebrahim Raisi, was forced to call the family of the victim, Mahsa Amini, and to order an official probe “to closely investigate the issue so that no right is violated.”

Some critics say the regime uses the dress code mainly as a way to control society. Others, both inside Iran and elsewhere, say impositions on women in Muslim societies must be challenged as a religious violation.

“The teachings of Islam, in all their diversity, encourage a woman’s spiritual aspirations absent an intercessor between her and God and define her identity as first and foremost a servant of The Divine, whose rights constitute a sacred covenant,” wrote Dalia Mogahed, an American of Egyptian origin who is director of research at the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding in Washington, in Al Jazeera last year.

The regime knows it has a problem. A recent official report said some 60% of women either do not support or regularly wear full “Islamic hijab.” That spirit of equality will be difficult to suppress.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Ready to move

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

When we welcome divine inspiration into our hearts, we’re inevitably moved to compassion, kindness, patience, and joy.

Ready to move

Almost unnoticed but for treetops

swaying slightly, chimes tunelessly

punctuating the air, the wind gently

courses, unseen, moving whatever

will go with it.

Nature hints at a momentum, invisible,

the motion of the law of divine Love,

God, sweeping through everywhere,

stirring divinely nimble hearts –

our hearts – to genuine kindness,

patience, restraint.

In prayer we seek to feel Love’s law –

Truth’s healing impetus, Spirit’s tender

guiding, Life’s rhythmic progress – the

peerless power of our Shepherd, God,

governing all in harmony.

The Christ-power moves our thought to

drink in the fullness of good that God

gives – the good that makes up what we are

as spiritual, subject to Spirit’s law alone.

This fresh breeze brings the grace of a

“you first” in gridlock traffic, impels a

resisted apology, sends a chilly silence

sailing – and humanity rises higher.

Free from the matted thicket of criticism,

no roots in hatred’s lawless, empty soil,

we – God’s spiritual children – yield to

Her all-encircling inspiration, ready

to move when the winds of God blow.

A message of love

Surf’s up!

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow for an analysis of President Joe Biden’s speech at the U.N. General Assembly, likely to span a wide range of topics from food shortages to the war in Ukraine.