- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Can irony really be conveyed with punctuation?

Casey Fedde

Casey Fedde

Punctuation only gets the spotlight when it misses the mark. Writers rely on punctuation to communicate important cues to readers. Without it, writers risk rambling, misplacing a subject’s prized possession, or even facing a lawsuit, as was the situation in 2014 for Oakhurst Dairy in Maine over a missing Oxford comma. So, in honor of National Punctuation Day on Sept. 24, let’s explore some forgotten punctuation.

For centuries, wordsmiths have demanded punctuation marks that would convey irony and sarcasm in written text, much like verbal intonation or facial expressions do in spoken conversation. But tipping off readers to phrases with meanings beyond – or even opposite to – what is written has proved challenging.

In the mid-1600s, British philosopher John Wilkins penned the first irony mark, an upside-down exclamation point appropriately resembling a lowercase “i,” which “both hints at the implied irony and suggests the inversion of its meaning,” writes Keith Houston in “Shady Characters: The Secret Life of Punctuation, Symbols, and Other Typographical Marks.”

Later, around 1900, French poet Alcanter de Brahm introduced a whiplike backward question mark (⸮) at the start of sentences as a warning to readers that a change of tone followed. But this point d’ironie, or irony point, may have been a step too far, as its placement spoiled the surprise.

By the 2000s, there was a heightened demand for conveying irony and sarcasm in writing. Enter the snark mark. The list of ironists is hard to pin down, but Slate’s Josh Greenman resurrected the upside-down exclamation point (¡), and typographer Choz Cunningham, among others, suggested using a period followed by a tilde to tell readers that a sentence should be read beyond its literal meaning. The .~ had potential because it was easily rendered by typographers – unlike the irony marks of yore, which may explain their absence today.

All this is to say that punctuation has its purpose. It demands respect, proper implementation, and praise. It’s just too bad we don’t have any current forms of snark marks. : )

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

‘This girl has united us all’: Women’s rage mobilizes Iranians

Women and their freedoms are the catalyst for widespread demonstrations in Iran demanding reforms – even, as some protesters are saying, the toppling of the Islamic Republic.

The protests that have swept Iran since the death a week ago of a young woman in the custody of the morality police have expressed a pent-up determination to create real change in the Islamic Republic.

Mahsa Amini was detained for an alleged infraction of edicts that require the full covering of women’s hair with a hijab, or headscarf, in public. Witnesses and family members say the 22-year-old was severely beaten in custody. Her death triggered rage that quickly morphed into broader anti-regime unrest.

By Friday, protests had spread to some 83 cities, and the violent clashes and a crackdown by security forces have left 26 dead, according to state TV. Protesters say 50 have died.

The protesters’ stated goals go beyond merely reforming the strict rules about women’s dress and extend to broadly expanding freedoms. And they speak openly of using violence to chip away at what they say is the calcified edifice of the regime.

“This is the moment I’ve been waiting for,” says Mahnaz, an English tutor in the Kurdish region of northwest Iran. “Our people have never been this united,” she says. “I know this might not necessarily lead to our ultimate goal of overthrowing the regime this time. But I have no doubt it’s causing a very deep crack on its body.”

‘This girl has united us all’: Women’s rage mobilizes Iranians

Viewed from the level of Iran’s acrid, smoke-filled streets, the protests that have swept the country since the death a week ago of a young woman in the custody of the morality police have unleashed a pent-up determination to create real change in the Islamic Republic.

The protesters’ stated goals go beyond merely reforming the strict rules about women’s dress and extend to broadly expanding freedoms. And they speak openly of using violence to chip away at what they say is the calcified edifice of the regime.

Yet it is women’s outrage that is the driving force.

Mahsa Amini was detained by Iran’s morality police for an alleged infraction of edicts that require the full covering of women’s hair with a hijab, or headscarf, in public. Witnesses and family members say the 22-year-old was severely beaten in custody, charges the authorities deny. Her death after a three-day coma triggered rage that quickly morphed into broader anti-regime unrest.

By Friday, protests had spread to some 83 cities, and the violent clashes and a crackdown by security forces have left 26 dead, according to state TV. Protesters say 50 have died.

Videos posted on social media appear to show police firing directly into crowds.

Women have conducted mass burnings of headscarves, and even symbolically cut off their own hair in protest, against a backdrop of burning police cars and buses, and clashes with baton-bristling riot police.

Indeed, women and the evisceration of their freedoms are for the first time since the Islamic Revolution of 1979 the catalyst for demonstrations demanding reform, even, as some on the streets are saying, the wholesale toppling of the regime.

“This is the moment I’ve been waiting for,” says Mahnaz, a 40-something English tutor in Sanandaj, a city in the Kurdish region of northwest Iran near Ms. Amini’s hometown, who has taken part in the protests. Like others interviewed, she gave only one name. Individuals in Iran were contacted by phone or online messaging services, despite severe disruptions to internet usage this week across the country.

“Our people have never been this united. Our men could never be more supportive of women,” Mahnaz says. “I know this might not necessarily lead to our ultimate goal of overthrowing the regime this time. But I have no doubt it’s causing a very deep crack on its body.

“It’s like a wall which you can’t smash to the ground with one blow. More blows, and it will collapse,” she says. “I am absolutely positive, victory is ours and it’s more imminent than it’s ever been.”

Shrinking political space

For years Iranians have reeled from a growing sense of hopelessness due to an economy crushed by U.S.-led sanctions, mismanagement, and corruption; political disenfranchisement; and more recently, even the failure to restore the 2015 nuclear deal with world powers.

Those problems have been exacerbated, analysts say, by conservative and hard-line control of all levers of power in Iran. Since President Ebrahim Raisi assumed office last year, the space for political expression has shrunk further.

In July the government rolled out a new hijab policy, and videos of morality police violently enforcing strict rules have gone viral.

On Thursday, during his first visit to the United Nations in New York, Mr. Raisi decried the “acts of chaos” in the streets of Iran.

“The Islamic Republic ignored us women, humiliated us, and destroyed two entire generations of women, and it only got worse,” says a protester in Sanandaj called Shiva, who’s 19 and plans to be a civil engineer.

“But they never knew that the rage was just intensifying beneath the surface. And guess what? We’re there to vent all that accumulated anger back into their faces. ... And trust me, it will be devastating,” she says.

“This girl [Ms. Amini] has united us all, because we could all relate to her, not just women, even men. She’s the embodiment of our plight; in one word she’s ‘Iran,’ its suffering, the barest form of a nation’s misery under a criminal regime,” Shiva says.

“Woman, life, freedom”

The protests have seen a welter of slogans, including “Death to the dictator” – a reference to Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, whose portraits have been torn down and burned.

But there was also “Woman, life, freedom” – about the issue that sparked these protests, and a desire to open civil society.

According to Tara Sepehri Far, Iran researcher for Human Rights Watch, under Mr. Raisi Iran has been “trying to further curtail the very minimal space that activists were trying to create.”

“Labor rights activists, teachers, those were some of the leading voices in civil society that were organizing peaceful mobilization. They’ve been arrested; there’s been a crackdown against them,” says Ms. Sepehri Far. “There’s been a lot of human rights defenders [who] have been summoned to serve prison sentences.

“As a woman who grew up in Iran, seeing people united en masse for something that is about women’s choice of dress code, as well as obviously accountability for the death of Mahsa, it is unprecedented,” she says.

“I have never seen the criticism and calls for reform this loud. So regardless of where these protests go, the debate on hijab has moved forward forever, and there is no going back,” she adds. “Iranian women have demonstrated their will to walk in streets of big cities without hijab in total defiance of the law.”

Past nationwide protests have been brutally squelched, such as in 2009 over a presidential election widely seen as rigged, and in 2019 over economic grievances that are reported to have left 1,500 dead.

“No-violence idea is gone”

This time the anger seems to have leaped beyond class, economic, and ethnic boundaries that marked previous upheavals. Another change is the rejection by some of peaceful methods.

“This time the no-violence idea is gone. Even very young kids are sharing stuff [about] how to defeat the security forces,” says a businessman in southern Iran, who asked not to be identified further.

“In the past we wanted to be on the peaceful side and that was a value, but now it is the opposite,” he says. He points to a 19-year-old woman sharing tactics on social media of how to “take down” a squad of police officers on motorcycles.

Also making the rounds is a list of 13 techniques for countering interrogation, based on the past experience of detainees in Iran.

“Mahsa was a trigger,” says the businessman. “Establishment corruption is making everyone angry, but as I talk to very young friends, they are tired of being told what to do and not do,” he says. “They want to take down everything.”

“Those moments are behind us when they held rifles and we gave them flowers,” says Afshin, a student in Sanandaj.

Fueling popular anger is how the current government appears to have turned upside down 25 years of conventional political wisdom about maintaining peace in Iran. It holds that when the hard-line minority has the political upper hand, as it does today, social rules like hijab-wearing are slightly relaxed – in an unspoken quid pro quo over other policies unpopular with the majority, reform-minded population.

“It is quite clear that the government of Ebrahim Raisi has to give something back to the ultraconservative elements of the system that have elevated him to this position, and in these circles the mandatory hijab is obviously a very sensitive and very elementary issue,” says Adnan Tabatabai, an Iran expert and founder of the Bonn, Germany-based Center for Applied Research and Partnership With the Orient.

At the same time, he says, there may now be “a critical mass of political figures that may be pushing for gradual changes in how the mandatory hijab is enforced.”

“Probably it is not anxiety that the system and the elite feel, because they’re all aware that they have the necessary zeal and the necessary means to suppress these kinds protests and clear the streets in the coming days and weeks,” says Mr. Tabatabai. “But we at least have some current and former officials who have been extremely critical of mandatory hijab and its enforcement, who spoke out long before the case of Mahsa Amini, and have spoken out again.”

Two sisters

Any change won’t come soon enough for two sisters in Kermanshah, a provincial capital in northwest Iran. Each hold master’s degrees, and both were peaceful attendees at rallies. One night last week one was arrested, when 30 security agents descended on their home at 3 a.m.

“I couldn’t believe my eyes,” says one sister, who reckons her sibling was identified by security cameras. “You can’t believe how wild they were in the raid, cursing with the worst-ever sexist slurs, dragging her on the floor.

“If you remember, once they were propagating the slogan that if we don’t fight Islamic State in Syria, we have to battle it in our streets,” she says.

“Now they are ISIS loud and clear, and they have no shame to act like it. So aren’t we fighting an enemy right on our own soil?” she asks. “They are occupiers; it’s high time we pushed them out.”

An Iranian researcher contributed reporting for this story.

The Explainer

New York is suing Donald Trump for fraud. Three questions.

Where does a country draw a line between launching investigations for political motives and ensuring that the rule of law applies to every citizen, even the powerful?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When New York Attorney General Letitia James filed a civil complaint against Donald Trump this week, she added yet another front in the many legal battles the former president now faces.

But in this case, the New York attorney general announced that the stakes in this civil complaint were high: She is seeking to bar Mr. Trump and three of his adult children – Donald Trump Jr., Ivanka Trump, and Eric Trump – from ever running a business in their former home state again.

Mr. Trump and his attorneys have labeled most of the charges against him as part of a partisan “witch hunt.”

“Where do we as a country ... draw the line between avoiding partisan investigations and allowing for impunity because somebody has a political role?” asks Cassandra Burke Robertson, professor of law at Case Western Reserve University. “If the law enforcement community can’t prosecute because it doesn’t want to look like we’re engaging in politics, then are we allowing people to be above the law? I don’t personally know where to draw that line, but I think it’s a really hard question.”

New York is suing Donald Trump for fraud. Three questions.

On Wednesday, when New York Attorney General Letitia James filed a civil complaint against Donald Trump and other executives in his business organization, she added yet another front in the many legal battles the former president now faces.

In this case, the New York attorney general announced that the stakes in this civil complaint were high: She is seeking to bar Mr. Trump and three of his adult children – Donald Trump Jr., Ivanka Trump, and Eric Trump – from ever running a business in their former home state again.

“It’s one of a big stack now,” says Cassandra Burke Robertson, professor of law at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. “The former president is facing a lot of legal peril from a lot of different angles, too, and I don’t know which is going to end up being the most significant.”

Why did New York bring civil charges against former President Trump this week?

New York prosecutors launched an investigation into Mr. Trump’s business practices after his former attorney Michael Cohen testified before Congress in February 2019, detailing some of the Trump Organization’s alleged fraudulent practices. Wednesday’s civil complaint followed a three-year investigation into these accusations.

In the 222-page civil complaint filed Wednesday, Ms. James accused Mr. Trump, his three oldest children, and other executives of “knowingly and intentionally” engaging in illegal financial schemes to benefit his organization. Company executives “falsely inflated his net worth by billions of dollars to unjustly enrich [Mr. Trump] and cheat the system,” the attorney general said.

Ms. James framed the civil complaint against the former president within a larger context, calling it “a tale of two justice systems, one for everyday working people, and one for the elite, the rich, and the powerful.”

“For too long, powerful, wealthy people in this country have operated as if the rules do not apply to them,” she said. “Donald Trump stands out as among the most egregious examples of this misconduct.”

The civil complaint alleges that Mr. Trump’s company made more than 200 false statements about the values of his properties, allowing him to deceive lenders, insurance brokers, and tax authorities and save an estimated $250 million from 2011 to 2021.

“It essentially paints the Trump Organization as engaging in a long-running fraud scheme to try to adjust the valuation of its assets upward when that served their interests to obtain loans or for insurance purposes,” says Robert Mintz, a partner in the Newark office of McCarter & English law firm. “And then, at the same time, adjusting those same valuations downward for tax purposes.”

The New York attorney general said she would seek to fine the Trump Organization a $250 million penalty. More significantly, in addition to seeking to permanently bar Mr. Trump and three of his children from running any business registered in New York, she also wants to bar them from taking out any loans or entering into any real estate deals in New York for five years.

State prosecutors in New York filed similar civil complaints against Mr. Trump’s business organization over the past decade. In 2013, civil charges against Trump University led to a $25 million settlement, and in 2018, charges of fraud against the Trump Foundation, a charitable organization, led to a $2 million settlement. Mr. Trump then shuttered both organizations.

How is this civil complaint related to Mr. Trump’s other legal troubles?

While New York’s attorney general filed a civil complaint on Wednesday, the Manhattan district attorney’s office, now led by Alvin Bragg, has been conducting a criminal investigation into many of the same issues.

On Oct. 24, Manhattan prosecutors will bring criminal charges against the Trump Organization to trial. The company’s longtime chief financial officer, Allen Weisselberg, has already pleaded guilty to 15 felonies, including participating in company schemes to avoid paying taxes. He must testify as part of his plea agreement, but he refused to testify against Mr. Trump.

Mr. Bragg declined to bring criminal charges against Mr. Trump or any other individuals in his companies, however, and only the Trump Organization will be on trial next month.

But Mr. Trump faces a number of other investigations:

- The Justice Department is investigating possible crimes Mr. Trump may have committed when he took a trove of classified documents with him after he left office. On Aug. 8, FBI agents with a search warrant entered the former president’s Mar-a-Lago estate in Florida to retrieve what they say are highly sensitive documents relating to national security. On Wednesday, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals said investigation into those classified documents could continue in a strongly worded ruling that found a federal judge may have overstepped by denying investigators access to classified documents.

- In Georgia, Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis is investigating the former president and others in a case that could allege conspiracy to commit election fraud, experts say.

- The House committee investigating the Capitol attack of Jan. 6, 2021, continues to collect evidence that could be used by the Justice Department as it also investigates allegations of a conspiracy to commit election fraud as well as the former president’s role in the Capitol Hill riot.

- In August, a federal judge allowed a civil case against the former president to proceed after four U.S. Capitol police officers injured in the Jan. 6 insurrection sued Mr. Trump for instigating the riot.

- A New York journalist who has accused Mr. Trump of sexually assaulting her in the 1990s is preparing to bring a civil case against the former president after New York passed a law giving survivors an opportunity to sue their attackers even if statutes of limitations have expired.

Is the civil complaint against former President Trump’s business practices politically motivated?

Mr. Trump and his attorneys have labeled most of the charges against him as part of a partisan “witch hunt” as he defends himself on multiple fronts, including the most recent civil complaint in New York.

“Today’s filing is neither focused on the facts nor the law – rather, it is solely focused on advancing the attorney general’s political agenda,” said Alina Habba, one of Mr. Trump’s attorneys, on Wednesday. “It is abundantly clear that the Attorney General’s Office has exceeded its statutory authority by prying into transactions where absolutely no wrongdoing has taken place.”

As a candidate in 2018, Ms. James promised to investigate the former president, and during her celebrations on the night she was elected attorney general, the former city councilwoman and public defender pledged to shine “a bright light into every dark corner of his real estate dealings, and every dealing, demanding truthfulness at every turn.”

Some legal experts suggest the Trump Organization’s practices may have never been scrutinized so closely if Mr. Trump had never entered politics.

“Fraud cases like these are somewhat difficult to prove, because there’s not a lot of time or money dedicated to enforcement,” says Professor Robertson. “Even the IRS and state tax officials only have so much money to conduct investigations, so they go after either the most obvious cases or the cases that come up to them.”

“This is a case that wouldn’t get brought unless there was overwhelming documentation,” Professor Robertson continues. “Yet, even if the Trump Organization may have had this very long history, at least according to the attorney general, of engaging in these practices, it really came to light when he entered politics, and it might not have, had he not entered politics.”

It is not the businesses who had dealings with the Trump Organization bringing a civil case alleging fraud, says Mr. Mintz, a former federal prosecutor and current chair of his firm’s government investigations and white collar defense practice.

“If this case gets to a trial, the defense team is going to say that the parties on the other side of these deals were extremely sophisticated banks and sophisticated lenders and sophisticated insurance adjusters, and they certainly had the ability to do their own valuation of these assets that they were using as collateral to make loans,” Mr. Mintz says. “And at the end of the day, as former President Trump’s lawyers have already pointed out, the lenders made millions of dollars in interest from placing loans with the Trump Organization, loans that he has not defaulted on.”

This may be one reason Ms. James framed the civil complaint as “a tale of two justice systems” rather than the state protecting New York businesses.

“But [Mr.] Trump has really forced the issue here. Where do we as a country ... draw the line between avoiding partisan investigations and allowing for impunity because somebody has a political role?” says Professor Robertson. “On the other hand, if the law enforcement community can’t prosecute because it doesn’t want to look like we’re engaging in politics, then are we allowing people to be above the law? I don’t personally know where to draw that line, but I think it’s a really hard question.”

Why is Italy swerving far right? Many feel they have no choice.

Italians have seen a variety of governments come and go over recent decades, but with few results that they want. Now they look set to elect a new leader, despite her fascist ties: Giorgia Meloni.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Giorgia Meloni, leader of the far-right Brothers of Italy party, looks likely to become Italy’s first female prime minister in Sunday’s elections.

She has waged a slick communication campaign, using speeches peppered with anecdotes to suit each region. Her messages have something for everyone: fiscal relief, youth employment, secure borders, products made by Italians in Italy, regaining some sovereignty from the European Union, and turning Italy into a renewable energy hub.

But Ms. Meloni’s rise to the top of the polls has alarmed many, due to her xenophobic rhetoric, her and her party’s connections to Italy’s fascist past, and the track record of the Brothers of Italy while governing in Italy’s Marche region.

Though her campaign has genuine appeal for some Italians, for others she is simply the option untried. After years of center-left, center-right, and populist governments, Ms. Meloni and the Brothers of Italy are “fresh faces” – and that may well be their biggest asset.

“Meloni will get many votes because others have lost their credibility,” says Giancarlo M., a retired fish market worker in Ancona. “She has worked for those in despair, and won over the disillusioned.”

Why is Italy swerving far right? Many feel they have no choice.

As young female protesters wrapped in rainbow flags demonstrate at a Brothers of Italy campaign rally in Milan, party leader Giorgia Meloni pokes fun at them from the stage.

“They finished their holidays, got off dad’s yacht, and came here,” she says, as security tries to keep party supporters’ tempers from flaring, particularly after the women call them fascists.

Jokes are par for the course as Ms. Meloni crisscrosses Italy to whip up support for her party ahead of elections on Sunday, Sept. 25. The far-right politician looks likely to become Italy’s first female prime minister, as the country is gripped by political and economic upheaval. She has waged a slick communication campaign, using speeches peppered with anecdotes to suit each region. Her messages have something for everyone: fiscal relief, youth employment, secure borders, products and children made by Italians in Italy, regaining some sovereignty from the European Union, and turning Italy into a renewable energy hub.

But Ms. Meloni’s rise to the top of the polls has alarmed many, due to her xenophobic rhetoric, her and her party’s connections to Italy’s fascist past, and the track record of the Brothers of Italy while governing in Italy’s Marche region. Though her campaign has genuine appeal for some Italians, for others she is simply the option untried. After years of center-left, center-right, and populist governments, Ms. Meloni and the Brothers of Italy are “fresh faces” – and that may well be their biggest asset.

“Meloni will get many votes because others have lost their credibility,” says Giancarlo M., a retired fish market worker who likes her emphasis on Italy’s potential as a renewable energy hub. “She has worked for those in despair, and won over the disillusioned.” Like many Italians, he declined to give his full name to the media.

“Christianity, being Italian, and being a mother”

Sunday’s snap elections were triggered by the resignation of Prime Minister Mario Draghi and the collapse of his broad government coalition, which the Brothers of Italy were not part of. But the party rose in popularity partly at the expense of two parties that were in the coalition: the center-right Forza Italia, the party of outlandish octogenarian and former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, and the hard-right League party of Matteo Salvini, an ex-interior minister. Both Forza Italia and the League are expected to join the Brothers of Italy in the next government as junior partners.

Ms. Meloni and her party have a history further to the right of either of their conservative rivals. In her youth, she was a member of the Italian Social Movement (MSI), which was founded by the heirs of Benito Mussolini. The Brothers of Italy also use iconography tied to the MSI. But Ms. Meloni rejects the “fascist” label, saying fascism has been confined to history.

Her supporters echo those sentiments. “Brothers of Italy is on the right, but it is not the extreme right,” says Paola Marrone, a Milan-based lawyer who takes pride in always voting for the party, even when it barely secured 2% of the vote.

Ms. Marrone considers herself completely in sync with Ms. Meloni’s social and economic views, although on the international front she is less on board with Ms. Meloni’s support for Ukraine. Euroskeptical parties like Brothers of Italy tend to have better ties with Moscow. “[Ms. Meloni] has an eye out for Italians,” says Ms. Marrone. “We are invaded by immigrants. The plus that Meloni has is that she is coherent, concrete, and credible in her proposals.”

Indeed, when addressing the crowd in Milan, Ms. Meloni gets the loudest applause for her take on family demographics and migration. Italy has the third oldest population in the world, and deaths far outweigh births. It is also a steppingstone for Europe-bound migrants.

“This is not a demographic winter,” she declares. “Gentlemen, it’s an ice age. It is clear this nation is going to disappear, and I don’t want this nation to disappear. I don’t think the demographic problem can be solved by bringing in immigrants, as the left says. ... I want a nation that says, ‘When you make a son, you are doing me a courtesy. Not only will I pay you for it, I will thank you for it.’”

Although she has moderated her language, especially in speeches geared for the European audience, Ms. Meloni’s mantra – “I am Giorgia, I am a woman, I am a mother, I am Italian, I am Christian” – neatly sums up her message. “These are the main values that Giorgia Meloni is calling for and speaking to: Christianity, being Italian, and being a mother,” says Marianna Griffini, lecturer in the Department of European and International Studies at King’s College London.

“They are against freedom of choice”

Sitting in the shadow of the Church of St. Domenico at the Piazza del Plebiscito in Ancona, representatives of a local feminist network say the Brothers of Italy could mean a retreat for women’s rights in Italy. They have seen it happen, they say, because the region of Marche where they live is one of two where Brothers of Italy won regional elections in 2020, after decades of being governed by the center-left.

Abortion has been legal in Italy since 1978, but women in Marche are struggling to access the procedure and often need to travel to other regions to get it. That’s because Marche has one of the country’s highest percentages of so-called conscientious objectors, or doctors who refuse to perform abortions. And Marche also refuses to implement updated health ministry guidelines that extended women’s right to access the abortion pill to nine weeks of pregnancy, rather than seven. That’s a problem, the women say, due to huge waiting lists and a provision for a seven-day waiting period before a woman can get an abortion.

“Brothers of Italy mask themselves as pro-life but really they are against freedom of choice,” says Manuela Bartolucci, a former obstetrician. “They worry that if Italian women abort, the ethnic composition of Italy will change. They present abortion as a cause for low-birth rate and link it to demographic fears ... that immigrants are giving birth to many children and these people will replace Italians.”

She also points out that the party voted against civil unions in Italy and opposed giving anti-discrimination protections to the LGBTQ community. “[Brothers of Italy] want women to come back to the role of wives and homemakers,” adds her friend Dolores Rossetti, who volunteers at a center for domestic violence survivors. “Being rewarded for having more children is a fascist idea.”

Giussepe Rizzi, president of the Catholic faith and education association Azione Cattolica Arcidiocesi Ancona-Osimo, notes abortion is a polarizing issue, especially among staunchly Catholic Italians. “Abortion, like euthanasia, is a topic relating to life that is very delicate,” Mr. Rizzi said in a phone interview. “The Christian community is very divided. ... Performing an abortion is not the same as operating appendicitis. It can be correct for a doctor to refuse to perform an abortion.”

The LGBTQ community is also concerned about a Ms. Meloni victory. Activist Giacomo Galeotti notes Marche held a Pride parade in 2019 with the support of regional authorities. That backing ended with Brothers of Italy. “It’s really clear the vision Giorgia Meloni has on LGBT+ rights,” says Mr. Galeotti. “She is against it.”

The regional government of Marche declined a request for in-person interviews or to answer questions via email.

“There are no alternatives left”

The fish market of Ancona springs to life well before the rest of the city. Large and small vessels slip out into the Adriatic after midnight and return in waves before 5 a.m. Hundreds of boxes filled with the catch of the day are presented for the assessment of potential buyers. Numbers on a digital blackboard announce the price of clams, shrimp, sole – values rising and falling in the search of a deal.

Ms. Meloni’s promises of fiscal relief and financial help for families have hooked several fishers and retirees lingering for coffee at the port. They say the prohibitive price of fuel has forced them to cut down the number of days they spend at sea from four to two. Her emphasis on Italian sovereignty also resonates. EU funding may mean the port is getting new cash registers and a restaurant, but Brussels’ crackdown on plastic and overfishing has made a bigger, negative impression.

“For me it was a mistake to enter the EU,” says Roberto, upset over restrictions on the amount of clams boats can catch: 400 kilograms (880 pounds) per vessel. “The EU makes rules for everyone, but you can’t apply the same fishing norms in Germany and Holland to the Adriatic Sea. It is not the same thing. Everyone has different product. You can’t put a cap on fishing. If the market demands more, then we need to go get the fish from somewhere else.”

Others like Ms. Meloni’s tough talk on migrants. Andrea Amici, another fisher, calls migrants “disgusting stuff” who would best be avoided.

“Meloni will have a lot of support because there are no alternatives left,” Mr. Amici says. He sees legislative efforts to criminalize discrimination against the LGBTQ community and legalize cannabis as prime examples of what he considers senseless laws supported by the left. “There are bigger issues than this with Italy coming out of the pandemic and the war. The center left has governed for 40 years and delivered nothing. It only makes taxes, and things are already difficult for us.”

Paci, the aging captain of the fishing vessel Il Lupo, can’t shake off concerns over the roots of Ms. Meloni’s party. “For me, they are the heirs of fascists,” he says. “Fascists have not run the country since World War II. If they are in power now, who knows what they will do, but the thought is scary.”

Maria Michela D’Alessandro and Natasha Caragnano supported reporting for this article.

Editor's note: The original version misspelled Marianna Griffini's name.

Listen

Nuclear energy: What might cool a hot debate

Climate change may be placing nuclear power in a new light. Our writer describes how a willingness to be humble helps opposing sides consider some trade-offs in the search for energy solutions.

It’s one of the hottest of hot-button issues.

Proponents of nuclear power hail it as a clean alternative to fossil fuels – no greenhouse gases produced. Opponents point to the long-lasting effects of nuclear mishaps and issues around where to build facilities and store waste. What’s changing is the backdrop: rising awareness of the urgency of climate change.

“Nuclear has shifted from this big, fearful thing to a possible solution to this other big, fearful thing,” says Stephanie Hanes, who covers the environment and climate issues for the Monitor. She spoke to Samantha Laine Perfas about how a controversial source of power generation is being viewed in a new light, why two sides are considering trade-offs, and the story she wrote with Lenora Chu.

“There’s been this really important shift,” Stephanie says, from debating whether action is needed to discussing what combination of actions offers a way forward. “And in some ways, this is a creative and sometimes contentious but [also] forward-moving conversation now,” she says. – Samantha Laine Perfas and Jingnan Peng/Multimedia reporters/producers

Note: This audio interview is meant to be heard, but we realize that listening is not an option for everyone. You can find a full transcript here.

Monitor Backstory: A shift on a power source?

In Pictures

Are New York’s dining sheds here to stay?

The dining shed quickly emerged as a pandemic lifeline for New York restaurants. What began as an emergency stopgap has since become a community fixture that the city wants to make permanent.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

The streets of New York have always been jampacked, but since the pandemic, they’ve also been full of outdoor dining sheds. During lockdown, these structures kept many restaurants in business. More than two years later, some have become eyesores while others have added color and life to the neighborhoods in which they operate.

The city is working to make the sheds permanent and to implement regulations that address neighbors’ concerns about increased noise, sanitation problems, and lack of access.

Michael Abruscato understands the issue. When SAINT, the restaurant he manages, took over its current location, a dilapidated dining shed stood in front. SAINT’s owners replaced it with a more secure and stylish structure, decorated to match the restaurant’s interior.

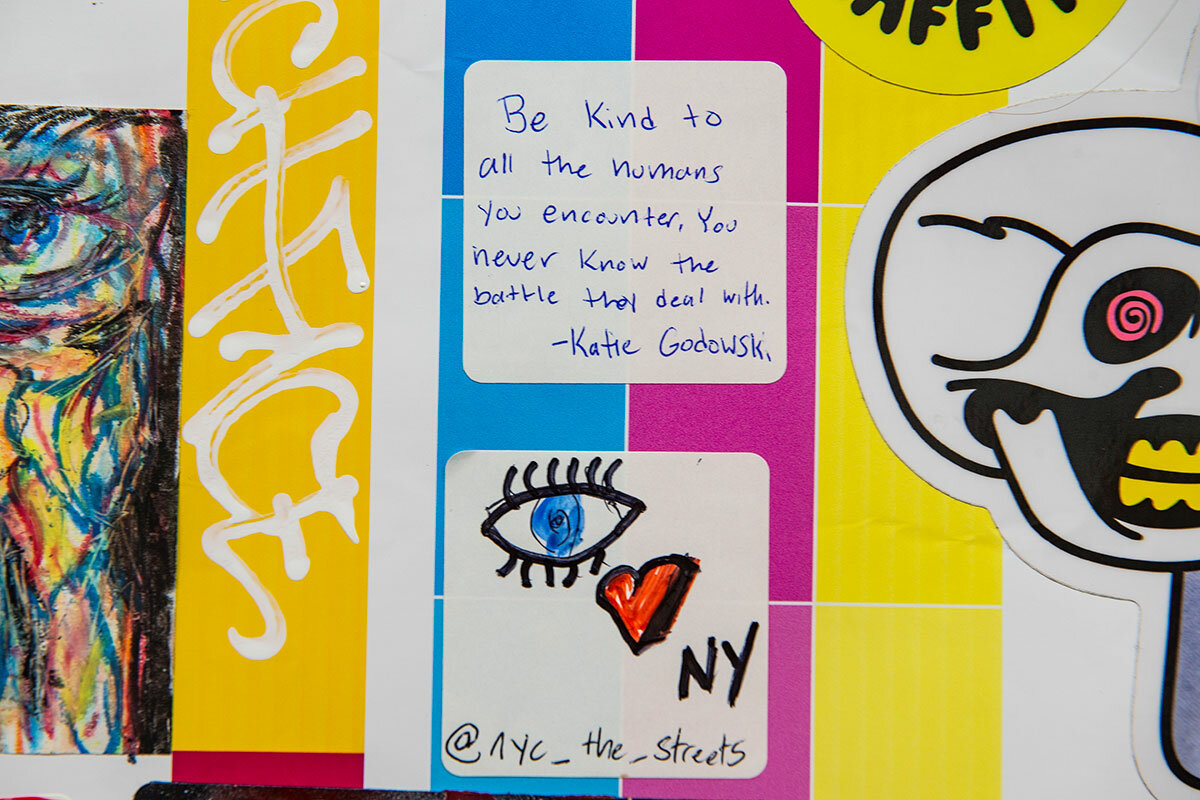

Maintenance isn’t easy. Mr. Abruscato keeps a bucket of paint on hand to cover the inevitable graffiti. The restaurant manager plans to winterize the pergola and create a “winter wonderland” dining experience for the months ahead.

“Living in the Northeast, you’re always kind of stuck inside,” Mr. Abruscato says. “So it’s beautiful to have [outdoor dining] now. ... It just changes the vibe.”

Are New York’s dining sheds here to stay?

The streets of New York have always been jampacked, but since the pandemic, they’ve also been full of outdoor dining sheds.

During lockdown, these structures kept many restaurants in business. More than two years later, some have become eyesores while others have added color and life to the neighborhoods in which they operate.

The sheds were allowed under the Open Restaurants program, which the city is working to make permanent. The mayor’s office says new regulations will address neighbors’ concerns about increased noise, sanitation problems, and lack of access.

A group of residents from several boroughs filed a lawsuit to remove the sheds because they say the structures harbor pests and block parking spaces.

Michael Abruscato understands the issue. When SAINT, the restaurant he manages, took over its current location, a dilapidated dining shed stood in front. SAINT’s owners replaced it with a more secure and stylish structure, decorated to match the restaurant’s interior.

Maintenance isn’t easy. Mr. Abruscato keeps a bucket of paint on hand to cover the inevitable graffiti. Despite challenges, the restaurant manager has plans to winterize the pergola and create an outdoor “winter wonderland” dining experience for the months ahead.

“I lived in LA for 15 years, and I’m so used to outdoor dining,” Mr. Abruscato says. “Living in the Northeast, you’re always kind of stuck inside. So it’s beautiful to have it now. ... It just changes the vibe.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A creative response to inflation

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

From Washington to Hanoi, 11 central banks raised interest rates in recent days, signaling a consensus that the highest worldwide inflation in four decades requires an aggressive response. Yet what makes this bout with inflation different is that many companies and consumers are no longer waiting for central banks to restore stability. To an unprecedented degree, workplaces and factories are challenging an “inflationary mindset” with initiative and creativity.

“Forced to adjust to circumstances beyond their control and armed with technology that gives them more access to expertise than ever, consumers are developing a stronger sense of self-reliance,” an Accenture study of consumer behavior found in July. “As people become more self-reliant, they are also rethinking the values that drive them.”

A KPMG survey of corporate executives in August found that 65% anticipated increasing their technology investments by as much as 20% to mitigate the effects of inflation.

A moment of global economic uncertainty is revealing its hidden uses. Fueled by inflation, transformative shifts in business investment and consumer behavior are showing that creative abundance is outpacing material scarcity.

A creative response to inflation

Ever since the 2008 financial crisis, the world’s central banks have gradually found merit in coordinating with each other – particularly during volatile episodes in the global economy. Yet never have they flocked together like they did this week. From Washington to Hanoi, 11 central banks raised interest rates, signaling a consensus that the highest worldwide inflation in four decades requires an aggressive response.

One reason for the urgency is to prevent a mental spiral that inflation can provoke. When consumers fear that prices will keep rising, they may start spending more now to avoid spending more later. That added demand, in turn, puts added pressure on prices. “The longer the current bout of high inflation continues,” U.S. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said on Wednesday, “the greater the chance that expectations of higher inflation will become entrenched.”

That concern is based on the way people responded to rapidly rising costs in the past, such as the 1970s. What makes this bout with inflation different is that many companies and consumers are no longer waiting for central banks to restore stability. To an unprecedented degree, workplaces and factories are challenging an “inflationary mindset” with initiative and creativity.

“Forced to adjust to circumstances beyond their control and armed with technology that gives them more access to expertise than ever, consumers are developing a stronger sense of self-reliance,” an Accenture study of consumer behavior found in July. “As people become more self-reliant, they are also rethinking the values that drive them.”

That is reshaping their decisions about buying and saving. A new study by the consulting firm Gartner, for example, found consumers are relying more on new apps to compare prices and determine the shortest travel routes. That, in turn, is forcing companies to adapt. No longer able to assume that they can just pass along higher production costs to their customers, they are seeking new technology-based answers to production costs and supply-chain flows. A KPMG survey of corporate executives in August found that 65% anticipated increasing their technology investments by as much as 20% to mitigate the effects of inflation.

That points to an unintended beneficial consequence: Inflation is accelerating what Morgan Stanley calls “deflation enablers” in sectors that are increasingly central to the long-term global good, such as clean energy and mass energy storage. This is challenging assumptions that the shifts required by climate change would be costly and economically disruptive. On the contrary, the investment firm now forecasts that artificial intelligence and green solutions to long-term energy security are among the “broad categories of technologies that combat the effects of inflation.”

A moment of global economic uncertainty is revealing its hidden uses. Fueled by inflation, transformative shifts in business investment and consumer behavior are showing that creative abundance is outpacing material scarcity.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

No curse there

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Laura Remmerde

Recognizing that God has created us to bless, not harm, uplifts our thoughts and actions toward others, which in turn benefits our interactions and relationships.

No curse there

Sometimes when something comes at us out of the blue, it can be hard to know how to respond. That happened to me recently with a surprising, harsh comment from a friend. I didn’t respond verbally, but I was surprised at my inner reaction, which wasn’t very kind or forgiving.

Later, I began to think about it. Though I’d been silent, my inner response didn’t follow the golden rule Christ Jesus emphasized to his followers, to do unto others as we would have them do unto us. This bothered me, because I try to live by that rule. I also knew that thoughts – not just words – about other people and situations are important.

So I prayed about this, and a Bible story came to mind – that of a prophet named Balaam. A king named Balak came to ask Balaam to curse the children of Israel so that he could defeat them. But God said to Balaam, in effect, “I’ve already blessed them, and you cannot curse them.”

Balaam and Balak went round about this question, as Balak was insistent. But obedience to God won the day and protected the children of Israel. There was no curse there.

I realized this was an opportunity to make more real in my own life the understanding that we are all blessed by God. And because God, who is Spirit, created all – including my friend and me – in His image and likeness, we are God’s spiritual creation. We show forth God’s nature, and thus can only bless, never curse, what God has already blessed.

Recognizing these spiritual facts uplifted the way I’d been thinking about my friend and myself. This resulted in a complete turnaround in the situation with my friend. And even more than that, I was so grateful to know that this lesson I’d been shown can be applied in other situations, too, to help and heal.

We are created to bless!

Adapted from the Aug. 25, 2022, Christian Science Daily Lift podcast.

A message of love

Farewell, Mr. Federer

A look ahead

Have a great weekend. On Monday, we’ll be looking at the midterm elections and why the future of the Republican Party may be decided in Arizona.