- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

What would the US look like if it put children first?

Kim Campbell

Kim Campbell

Is American society good at making decisions that support children?

Not exactly, but it could pivot, argues Anya Kamenetz in her recent book, “The Stolen Year: How COVID Changed Children’s Lives, and Where We Go Now.”

In an interview, she says that adults did the stealing in her title – and they need to be the ones to find a way forward on issues affecting young people such as poverty, mental health, and learning loss (more national assessment results this week revealed historic drops in math scores).

“As a society we need to be really clear-eyed about the collective impact of our choices on our children,” she says. “I want to raise the alarm, and say this didn’t have to happen this way and this needs to be redressed.”

She observed what others in the United States did: that dog parks and bars were open, but not playgrounds and schools.

Child-centered public policy, suggests the former NPR education reporter, looks different. It includes thinking long term about issues, such as how to deal with climate change (an area she is focusing on more these days), and building systems that support caregivers.

Even now, though, children aren’t “doomed,” she offers. Moving forward starts with seeing the potential in them.

“When you talk to children about their experiences, it’s never helpful to dwell on what they lost,” she says. “It’s helpful to put their losses in context and focus on what we have a locus of control over, which is recovering.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

In Ukraine’s liberated areas, weight of Russian occupation lingers

For civilians and former soldiers in liberated parts of Ukraine, the memory of six months of Russian occupation is fresh as they seek to reclaim their dignity. Accounts of abuse are still emerging.

In a dank and dark basement in Kozacha Lopan, Ukraine, beside a makeshift cage welded by the Russians for detainees, the combat veteran recounts an ordeal involving torture and broken ribs. Vitalii’s is one of a growing compendium of personal stories from across the Kharkiv region that attempt to restore dignity and respect after living for half a year under Russian occupation.

The accounts – replete with horrific incidents of abuse, damaged or stolen property, and still-missing Ukrainian citizens, including children – are emerging in the wake of a Ukrainian counteroffensive in September that forced Russian troops to retreat from some 3,000 square miles.

Across the region, residents describe Russian forces portraying their presence on Ukrainian soil as permanent and benevolent, with victory assured. But if winning hearts and minds was a Russian strategy, detentions and heavy-handed abuse turned that on its head.

“The torture and the way they ‘talked’ to people only made it worse for the Russians,” says a Security Service of Ukraine officer who asked to be identified only by his call sign, Raven. “This [detention] place was built,” he says, referring to the makeshift cage, “and Russian actions only made more hatred and more [Ukrainian] patriotism.”

In Ukraine’s liberated areas, weight of Russian occupation lingers

With the Russian border no farther away than the arcing trajectory of a rifle round, the Ukrainian combat veteran had no chance to escape when Russian troops invaded Ukraine last February.

“I knew I would be captured … so I was waiting for this,” recalls Vitalii, a veteran of fighting Russians and their proxy forces in the eastern Donbas region in 2014 and 2015. His wife buried his Ukrainian military documents – including his commendations as a soldier – but a local boy-turned-collaborator pointed out Vitalii’s house.

Russian troops broke two of his ribs, and for one hour applied electricity to his body with a modified old-style rotary phone, in “revenge” for his previous military service.

As he recounts his ordeal, Vitalii stands in a dank and dark basement beside a makeshift cage welded by the Russians for detainees. His is one of a growing compendium of personal stories – from this northern town to Balakliia, Izium, and Kupiansk, farther east – attempting to restore dignity and respect after experiencing the grim pressures of living for half a year under Russian occupation.

The accounts – replete with horrific incidents of abuse and still-missing Ukrainian citizens – are now emerging across the northeast Kharkiv region, after a Ukrainian counteroffensive in September forced Russian troops to retreat from some 3,000 square miles.

The basement cage is strewn with two thin mattresses, crumpled dirty sheets, broken pieces of plastic foam for insulation, and several disposable plastic bowls. Vitalii says he doesn’t know if this is the cage he was held in, because his eyes were taped closed, and this is not the only basement detention cage found in town.

What he does remember is the pain was so great that he tried to smash his head on the floor, to knock himself out.

“They beat me everywhere but my head,” says Vitalii, who asked that he not be further identified. Sparing his head was because he was to appear on Russian television, which is widely watched in eastern Ukraine.

“The Russians used me as a ‘Nazi’ soldier, and asked: ‘Where were you [fighting in the Donbas]? Who did you kill?” he recalls. “I was supposed to say to Ukrainians on Russian TV, ‘Hey guys, you should give up.’”

Vitalii was held in the underground cage for five days, and then five days more upstairs at the Kozacha Lopan train station – where all rooms were full of fellow detainees, sitting back-to-back, he says. He was moved to another site in a nearby village, before being released.

Losing hearts and minds

Across the region, residents describe Russian forces tracking down Ukrainian veterans, officials, and anyone they deemed to be anti-Russian or a possible insurgent, even as they portrayed their presence on Ukrainian soil as permanent and benevolent, with victory assured.

Details of detention and heavy-handed abuse echo widely across the Kharkiv region, as they have in other territories reclaimed by Ukraine. If winning hearts and minds was a Russian strategy, such actions turned that on its head.

“The torture and the way they ‘talked’ to people only made it worse for the Russians,” says a Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) officer who asked to be identified only by his call sign, Raven.

“This [detention] place was built, and Russian actions only made more hatred and more [Ukrainian] patriotism,” he says, referring to the makeshift cage. SBU officers facilitated a trip for journalists in late September to Kozacha Lopan, which they said then was still dangerous due to the proximity of the Russian border and the presence of remaining collaborators.

Indeed, in Kozacha Lopan and nearby villages, the post-occupation picture is further complicated by a sizable portion of residents who were sympathetic to the Russian invasion at the outset of the war.

“Half the village was pro-Russian; now they are all hidden,” says a woman, with a black shirt and a faux-diamond Chanel brooch, who gave the name Yulia. Her husband, Andrii, was a veteran of the Donbas war and a retired Ukrainian officer, who fled to avoid arrest but was caught.

The Russians “came to the house and took my son and all our phones,” recalls the distraught mother, speaking near a wall of sandbags outside the Kozacha Lopan train station, where a gold letter Z, the symbol of Russia’s military campaign here, is spray-painted on the wall.

“They were calm. They asked, ‘Yulia, where is your husband?’ They knew him already. A collaborator pointed him out; he was a patriotic Ukrainian,” she recalls.

Every day she came from her village to a checkpoint in town, to ask the Russians there about her husband. She was told he was “alive and fine,” but sometimes the Russian troops would “look at each other, laugh, and tell me, ‘No soldier will ever give you this information.’”

The Russians didn’t harm civilians, asserts Yulia, aside from taking people’s cars and “trashing” them with hard driving, stealing valuables – including her son’s ring and necklace, when they detained him for 11 days – and even defecating in abandoned houses.

“Why [defecate] on carpets?” asks Yulia, still surprised at that particular vulgarity.

Andrii is still missing, weeks after Russian troops withdrew.

“The Russians were telling everyone they were very good, and that everything was good on the front line,” says Yulia. “They acted here as if on their own land. … The Russians constantly said, ‘Everything is OK. Victory is ours.’”

Bad behavior by Russian forces changed the minds of some Ukrainians who supported them, but most Russian sympathizers are “quiet and angry” now, or say they don’t care, because they were “very happy” when Russians were here, adds Yulia.

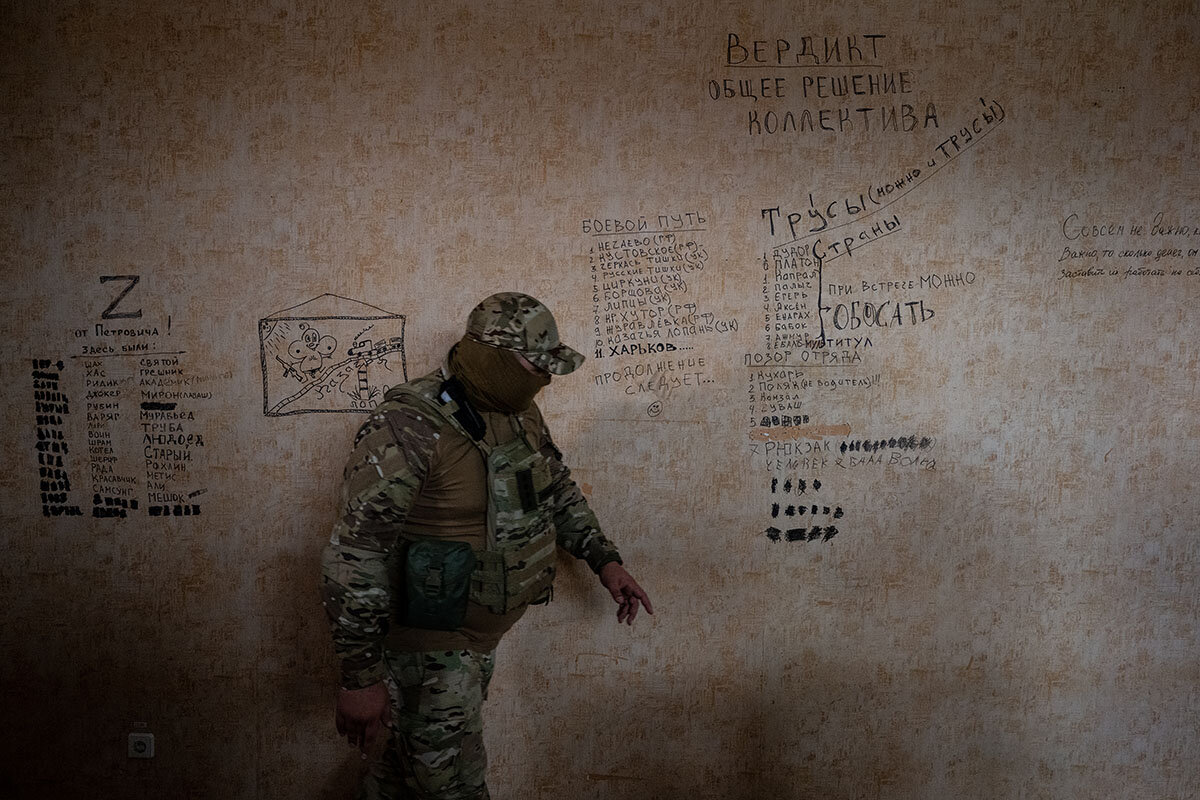

The Russians’ brutality appears to have been applied to their own soldiers as well, according to lists on a wall found at a Ukrainian border guard headquarters used by Russian troops.

Beneath a large letter Z written in black permanent marker appears to be a list of soldiers, with more than one-third of them crossed out – presumably because they had been killed, suggests SBU officer Raven.

The graffiti notes the “final decision of the team,” which applauds one list of soldiers who were in the “fighting way.” It names locations along the unit’s path of advance, and counts as the 11th objective Kharkiv, then adds, “to be continued,” with a smiley face.

Yet one other list is of “scaredy cat” soldiers of the country, who can be urinated upon “if you meet them.” Another list appears to present a worse category of those Russian soldiers who are the “shame of the unit” – several of those are also crossed out, as if casualties.

Children sent to Russian camp

The price paid by Ukrainian families during the Russians’ presence was not limited to detentions, about which stories emerge from every corner of territory reclaimed from Russia.

Indeed, the accounts include the treatment of children like Karina, age 13, who, along with scores of other Ukrainian children in occupied territories, was sent to summer camp in Russia. Some camps were advertised as simple summer holidays, while others promised more Russian patriotic fare.

The risks of traveling to a neighboring country that has mounted an invasion force were high, amid persistent reports of Russian forces taking hundreds of unaccompanied Ukrainian children across the border into Russia, calling them orphans, and putting them up for adoption.

From Kozacha Lopan, some 13 children were sent by their parents to the Little Bear camp in Krasnodar, some 450 miles to the southeast, near Russia’s Black Sea coast. Karina was meant to return Sept. 19 after 21 days, but by then Russian troops had retreated, and Karina’s young mother, Natalia, lost contact.

“Here there was constant shelling and it was dangerous. I let my daughter go to refresh herself,” says Natalia. When Ukraine recaptured Kozacha Lopan, families of the other children went to Russia to be with their children, but Natalia says she could not afford it.

Now other mothers she had been in contact with no longer answer her calls.

“I can’t say whether I trust the Russians or not, but I hope she comes back,” says Natalia. “I think we are all human beings, and they [Russians] are also human.”

Igor Ishchuk supported reporting for this article.

Toronto has a housing crisis. Activists are trying empathy to ease it.

In Toronto, where lack of affordable housing is reaching critical levels, activists are trying to reframe housing development in terms of community and empathy, rather than competition for resources.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

If any place needs a solution to its housing crisis, it is Canada’s biggest metropolis.

Average prices remain out of reach for residents of Toronto, despite recent declines in home prices due to interest rate hikes by the Bank of Canada. Single-family homes are valued at above $1 million in Greater Toronto. Canada faces one of the largest disconnects between housing costs and incomes in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

But local homeowners still balk at development projects to build more affordable housing. That’s where groups like More Neighbors Toronto try to make a difference.

“We attend [community consultation meetings] and talk about how it’s a building we could imagine ourselves or our friends living in, people who’ve been really struggling to find housing in the city,” says group founder Eric Lombardi. “It’s about making housing more personal, and not just some big structure that will change the beauty or character of a neighborhood.”

They are part of a broader movement of housing advocates and experts trying to change how people, particularly homeowners, think about intergenerational equity on housing. And they are focused on generating empathy and understanding across one of the biggest fault lines in North American cities today.

Toronto has a housing crisis. Activists are trying empathy to ease it.

When the community consultation meeting for a development in a northern Toronto neighborhood that includes 1,500 new apartment units – half of them affordable housing – got underway, it quickly turned contentious. Angry neighbors complained that the project would mean congested traffic, crowded schools, even increased crime.

But Eric Lombardi, a housing advocate, presented a different sort of response to the city planners.

He told the virtual meeting last October that the project, called Tyndale Green, is exactly the kind of option his generation needs in the middle of Toronto’s housing crisis – one that by some measures, is the world’s worst.

Members of the group Mr. Lombardi founded, More Neighbors Toronto, have been trying this tactic at community meetings across the city in an attempt to overcome local resistance and convince homeowners that change in their community does not mean a loss for them, but can be a gain for everyone.

“What used to happen before us is the [city and developers] would show up and get yelled at for an hour and a half. We attend and talk about how it’s a building we could imagine ourselves or our friends living in, people who’ve been really struggling to find housing in the city,” Mr. Lombardi says. “It’s about making housing more personal, and not just some big structure that will change the beauty or character of a neighborhood.”

They are just one group among a broader movement of housing advocates and experts trying to change how people, particularly homeowners, think about intergenerational equity on housing. And they are focused on generating more empathy and understanding across one of the biggest fault lines in North American cities today.

World’s worst bubble risk

If any place needs a solution, it is Canada’s biggest metropolis.

While interest rate hikes by the Bank of Canada have led to a decline in home prices in Toronto – as well as other Canadian cities – in recent months that is expected to continue, average prices remain out of reach. Single-family homes are valued at above $1 million in Greater Toronto, according to the Toronto Regional Real Estate Board.

It’s a volatile situation. Earlier this month, the UBS Global Real Estate Bubble Index of 25 major cities listed Toronto as the global city holding the highest housing bubble risk in 2022, with real house price levels in Toronto (and Vancouver) having more than tripled in the last 25 years.

It’s a problem that spans well beyond the country’s major cities. Canada faces one of the largest disconnects between housing costs and incomes in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. And it’s a gap that cuts along generations. Canadian Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland called the housing affordability crisis “intergenerational injustice” this spring.

Government officials in Canada increasingly feel that housing affordability has reached a tipping point, much as it has in the United States. The mismatch between housing supply and strong population growth and record-low interest rates during the pandemic amplified demand. The government, provinces, and municipalities have sought to address the issue with myriad programs to boost supply, offer tax credits to first-time buyers, and fix zoning laws. In Toronto, housing was at the heart of municipal elections on Oct. 24.

But for many fighting the crisis, shifting mindsets is just as important as policy. And many see this going beyond fighting NIMBY sentiment.

Housing inflation, says Paul Kershaw, a policy professor at the University of British Columbia, has provided a lot of homeowners – himself included – wealth, and much of that wealth has been sheltered, keeping younger generations, even higher-income ones, priced out. He says that notions of who is “rich” and who is “poor” – and who the victims of ageism are – require some soul-searching in what he calls a new “intergenerational tension.”

“Because [the housing inflation that is] actually harming younger people has been benefiting older members of their family who they love and who love them,” he says.

Society blames foreign buyers, money launderers, NIMBYs, mean-spirited developers, and Airbnb for housing woes, he says. “But the intergenerational tension actually invites us to look in the mirror and say, how might we be implicated? And that is a harder message to get anyone to lean into.”

The charitable think tank Generation Squeeze, which was founded by Dr. Kershaw and focuses on intergenerational inequity, has proposed an annual surtax on homes valued above $1 million, the proceeds of which would go toward affordable housing projects.

“Change is scary”

Major cities have always been expensive. But housing prices in Toronto have had a ripple effect in surrounding cities and even rural communities. Migration data from the federal government released in January showed 64,000 people leaving Greater Toronto for smaller locales within Ontario from 2020 to 2021. Some of that is pandemic-related, but it began before the rise of remote work and was led by young families. A Scotiabank report showed the highest out-migration from Ontario in 2021 in four decades.

This has implications for those moving away, but also those staying, says Mike Collins-Williams, CEO of West End Home Builders’ Association. If residents have to move away, it changes the nature of cities, undermining the idea that so-called stable neighborhoods, primarily where wealthier homeowners reside, are actually stable, he argues. It deprives neighborhoods of service workers and vitality. “Toronto, the city that’s supposed to be the entertainment heart, with the bars, the clubs, the music, the place where [younger] people are supposed to be, they’re leaving.”

Mike Moffatt, an economist and senior director of the Smart Prosperity Institute in Ottawa, Ontario, says one way to change views is to focus on the fact that the status quo isn’t working for many seniors, either. Many want to downsize, but in their neighborhoods.

“One area I think is ripe for looking at is actually how to create more senior-friendly housing,” he says. “I think we need to try and get out of the zero-sum frame and try to show how housing reform is good for existing homeowners. I think that’s the only way we’re going to get out of this.”

Ontario has said it will need 1.5 million new homes in the next decade. That includes a current shortage and anticipated one, with immigration on pace to hit a record 431,000 new residents in 2022. It is the “missing middle,” between single-family homes and high-rise condominiums, that many say is the future.

Colleen Bailey would purchase a home in the “missing middle” if she could. But although she says she has sizable savings for her age, homeownership as she nears 40 is still out of reach. As a member of More Neighbors Toronto, she has attended development meetings to voice her support for new housing. “It’s about trying to get people to have a little bit more empathy that it’s a struggle,” she says.

“Change is scary. So people think if you are comfortable, if you already own a home, then it seems like the safest thing to do is, you know, let’s just keep things the same,” Ms. Bailey says. “But I think we’re getting to the point where people realize that not changing is not a choice without any consequences, either.”

A deeper look

Pot prohibition cost Black communities. Can Black firms profit now?

Will minority communities most affected by criminalization and incarceration now be locked out of what is becoming a legal multibillion-dollar industry? What states and the federal government are doing to help restore the inequities of the past.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

-

Henry Gass Staff writer

In a high-profile example of how Americans’ attitudes toward marijuana have changed, President Joe Biden granted a pardon to people convicted of federal marijuana possession.

But as the nation’s attitudes change and the sale of legal marijuana becomes a multibillion-dollar industry, there’s a certain irony looming. Few of those who bore the costs of the war on drugs, particularly through incarceration, are poised to reap its rewards.

Nineteen states and Washington, D.C., have legalized the recreational use of marijuana, and 44 states have approved it for medical purposes. Legal sales increased 40% in 2021, reaching $25 billion. But less than 2% of legal marijuana businesses are Black-owned.

“It’s re-traumatizing a lot of these communities,” says Damian Fagon, chief equity officer for the New York State Office of Cannabis Management. “You spend 30 years arresting them for a product that you’re now letting a select few make a profit off of?”

Now, many states are trying to address the legacies of criminalization with social equity policies.

These policies generally include three parts: expunging the records of those convicted of breaking laws no longer on the books, reinvesting a portion of projected tax revenues into communities most affected by prohibition, and providing help for individuals in these communities to launch new businesses.

Pot prohibition cost Black communities. Can Black firms profit now?

For most of her life, Dr. Chanda Macias has been in the middle of America’s changing attitudes toward marijuana.

Growing up in Washington, D.C., in the 1990s, she witnessed what could be called the old outlook on the plant during the U.S. war on drugs: Marijuana is unqualifiedly dangerous, and those who possess or sell it are criminals who should be locked away.

“We saw a lot of people [in our communities] go to prison,” says Dr. Macias, a cell biologist who studied cancer and who now owns a growing medical marijuana business. “We were being disproportionately targeted and incarcerated, and it destroyed a lot of families.”

Through her research, Dr. Macias played a role in what is becoming the country’s new outlook on marijuana – including an emerging bipartisan consensus that marijuana has medical applications and fewer comparable risks than alcohol and tobacco, and that a half-century of criminalization was both misguided and wrong.

Dr. Macias, who studied biology at Howard University and got her Ph.D. in 2001, was among the first to apply for a business license when the District of Columbia legalized medical marijuana in 2010. In 2014, she launched the National Holistic Healing Center, a D.C.-based medical cannabis dispensary.

In a high-profile example of how Americans’ attitudes toward marijuana have changed, President Joe Biden granted a pardon to people convicted of federal marijuana possession this month. The symbolic gesture expunged the records of about 6,500 people. But he also urged governors to do the same with the far larger number of those convicted under state laws, and urged his administration to “expeditiously” review the federal classification of marijuana as a Schedule I narcotic, which is considered the most dangerous and includes heroin and LSD.

“Sending people to prison for possessing marijuana has upended too many lives and incarcerated people for conduct that many states no longer prohibit,” President Biden said in a statement. “Criminal records for marijuana possession have also imposed needless barriers to employment, housing, and educational opportunities. And while white and Black and brown people use marijuana at similar rates, Black and brown people have been arrested, prosecuted, and convicted at disproportionate rates.”

FBI Uniform Crime Report (2009-2019, U.S. Census Bureau

A new Monmouth poll out this week found that 69% of Americans approve of Mr. Biden’s pardons and 68% support the legalization of small amounts of marijuana. But as the nation’s attitudes continue to change and the sale of legal marijuana becomes a multibillion-dollar industry and the source of a tax windfall for states, there’s a certain irony looming, Dr. Macias and others say.

Few of those who bore the costs of the war on drugs, particularly through incarceration, are poised to reap its rewards.

The District of Columbia and 19 states have legalized the recreational use of marijuana, and a total of 44 states have approved it for medical purposes. Legal sales increased 40% in 2021, reaching $25 billion, according to Bank of America. But less than 2% of legal marijuana businesses are Black-owned in a fast-emerging industry that provided over $3.7 billion in tax revenues for states in 2021.

“It’s re-traumatizing a lot of these communities,” says Damian Fagon, chief equity officer for the New York State Office of Cannabis Management, a new agency established after New York legalized recreational marijuana in 2021. “You spend 30 years arresting them for a product that you’re now letting a select few make a profit off of? It’s pretty horrendous.”

New York’s notorious “Rockefeller laws,” passed in the 1970s, were especially severe, he points out. Selling 2 or more ounces of cannabis, or simply possessing 4 or more ounces, were both crimes that carried a minimum sentence of 15 years to life in prison.

Now, many states are trying to address the legacies of criminalization with a number of social equity policies.

These policies generally include three parts: expunging the records of those convicted of breaking laws no longer on the books, reinvesting a portion of projected tax revenues into communities most affected by prohibition, and providing help for individuals in these communities to launch new businesses.

At least 15 states now include at least one of these policies, and nine of these, including Arizona, Colorado, California, New Jersey, New York, and Illinois, have a version of all three.

“I think that there is widespread acceptance from the left and the right that the war on drugs was a failed experiment and that there is a better way to address this problem,” says Inimai Chettiar, federal director for the Justice Action Network, a bipartisan coalition promoting criminal justice reform.

New York’s approach

New York has been particularly aggressive as it seeks a restorative course.

Like Illinois and Vermont, New York now automatically expunges possession convictions, and it promises to reinvest 40% of tax revenues into communities disproportionately impacted by criminalization, the most of any state.

And half of all new business licenses will go to a diverse array of social equity applicants, not only individuals from communities impacted by prior laws, but also other minorities, women, disabled veterans, and struggling farmers.

Texas, by contrast, has a chosen a very different route. As one of about a half-dozen U.S. states where the plant is still mostly illegal, it categorizes possession of up to 4 ounces of marijuana as a misdemeanor, punishable by a maximum of a $4,000 fine and one year behind bars. Possessing more than 4 ounces is a felony.

Kirsten Shepard, founder of TrueStopper, is one of Austin’s first Black female business owners who sell CBD and hemp-related products, the only products derived from the marijuana plant that are legal in the Lone Star State.

Like Dr. Macias, Dr. Shepard believes legalizing marijuana would especially help cancer patients.

But for her, too, the most important aspect of legalization would be to address the ongoing injustices of prohibition. “Many people are still behind bars and incarcerated for those offenses, and then we have another group of individuals able to profit and make millions and millions of dollars off that industry? That’s injustice at its best,” she says.

The equity efforts of other states “even the playing field,” Ms. Shepard says, noting how few marijuana-related business owners look like her. “Because if we look at how those profits would be used, they would be creating jobs in the community, advancing our community.”

Texas casts a skeptical eye

Reforming Texas’ marijuana penalties is unlikely, experts say. State lawmakers from both parties have sought to decriminalize possession of marijuana in recent years, arguing in part that Texas would benefit from the tax revenue, but those efforts have been stymied by conservative Republicans.

Texas would have plenty of reasons to want to reduce penalties for marijuana possession, says Pamela Metzger, director of the Deason Criminal Justice Reform Center at Southern Methodist University.

“You’re saving prosecutorial resources,” she says. “You’re also saving policing resources,” she says.

It’s also costing taxpayers. Housing pretrial inmates cost local governments almost $1 billion a year in 2016, the Texas Judicial Council calculated.

“It’s in all our best interests to not engage [people] in the criminal legal system if we don’t have to,” says Professor Metzger. “Every dollar that goes to a marijuana arrest or a marijuana prosecution is a dollar that isn’t going to make your streets safe; it’s a dollar not going to a hospital, or to improving a street or a road.”

Texas Office of Court Administration

Gov. Greg Abbott, who is facing reelection this year, has expressed an openness to reducing penalties for marijuana crimes in the state.

“Prison and jail is a place for dangerous criminals who may harm others,” he said during a campaign event in January. “Small possession of marijuana is not the type of violation we want to stockpile jails with.”

But others disagree. President Biden’s announcement “is another attempt to normalize marijuana possession,” says Jimmy Perdue, chief of the North Richlands Hills Police Department and president of Texas Police Chiefs Association.

“Look across the country where they’ve started these conversations, it’s never just” legalizing small amounts, he adds. “It’s a dangerous, slippery slope.”

“Should [casual users] be going to jail? No, I don’t think so. So I agree with the governor on that,” he continues. “But there should be a consequence, because it’s illegal in the state of Texas.”

Public sentiment is trending differently. Fifty-one percent of Texans either support or strongly support legalizing marijuana for recreational use, according to a survey last month from The Dallas Morning News and the University of Texas at Tyler. Support grew to 67% in the survey when it came to legalizing the drug for medical use.

Texas is unlikely to follow the equity-focused policies of other states, but even for conservative states, “the trend continues to be towards legalization,” says Professor Metzger.

Even so, the effort to implement equity policies remains a structural challenge, experts say, especially when trying to increase the number of minority-owned marijuana businesses.

“The issue of access and equity in the cannabis industry is something that goes beyond marijuana arrests and incarceration and race,” says Mr. Fagon at New York State Office of Cannabis Management.

“There are legal markets where, in order to get a license, you may need $20 million to be able to open up these vertically integrated giant operations,” he says. “There is often no ability for you to enter the market without access to that kind of capital. And so what we’re trying to say here in New York is that small businesses and medium-size businesses are essential to creating an equitable supply chain. It can’t just be large corporations dominating the entire industry state by state.”

New York’s program will help provide low-cost loans for approved equity applicants. “You need to create regulatory frameworks so that entrepreneurs with maybe $50,000 can get something off the ground,” he says.

Dr. Macias describes the kinds of barriers that make the process both prohibitively expensive and difficult to navigate.

“I wrote [National Institutes of Health] grant applications when I was a researcher, so I had the skill set,” says Dr. Macias, who also mortgaged her house just to apply. “But for the normal person out here today, not many of us are skilled in application writing.”

“The second barrier is definitely real estate,” she continues. “You have to have real estate within your possession at the time of applying, and that can run anywhere from $25,000 to $100,000 a year,” she says. “And the last thing is that you have to show proof of funds that you can cover all the operational costs with at least 2 1/2 to three years in reserve.”

“So if you put all those realities together, that’s why we have to have social equity programs,” says Dr. Macias, who also has an MBA in supply chain management. “Because historically, we haven’t been able to produce the amount of money for the financial demands of this industry.”

Early on, she reached out to women involved with Women Grow, at the time a Denver-based organization seeking to be a catalyst for women to succeed in the emerging industry.

“I told them I have a license and I just need help, and women from Oregon, women from California, women from other states – I realized how I was being empowered by other women,” Dr. Macias says.

Today she’s become one of the most successful Black Latinas in the field, and she’s expanded her ventures to include Ilera Holistic Healthcare, an integrated company that develops and produces medical marijuana in Louisiana.

She also became the CEO of Women Grow. “As I evolved, I always wanted to give that back. And now we have women in multistate operations, women who have their brands in multiple states. It’s like, we have to start at the bottom, and now build up.”

Editor's note: This story has been edited to correct a misspelling of the first names of Dr. Chanda Macias and Dr. Kirsten Shepard.

FBI Uniform Crime Report (2009-2019, U.S. Census Bureau

Difference-maker

India’s street kids rarely make headlines – so they write their own

In India, a newspaper by and about street children offers a rare look into a community often described as “invisible.” Its success shows change is possible when vulnerable groups have the opportunity to tell their own stories.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Haziq Qadri Contributor

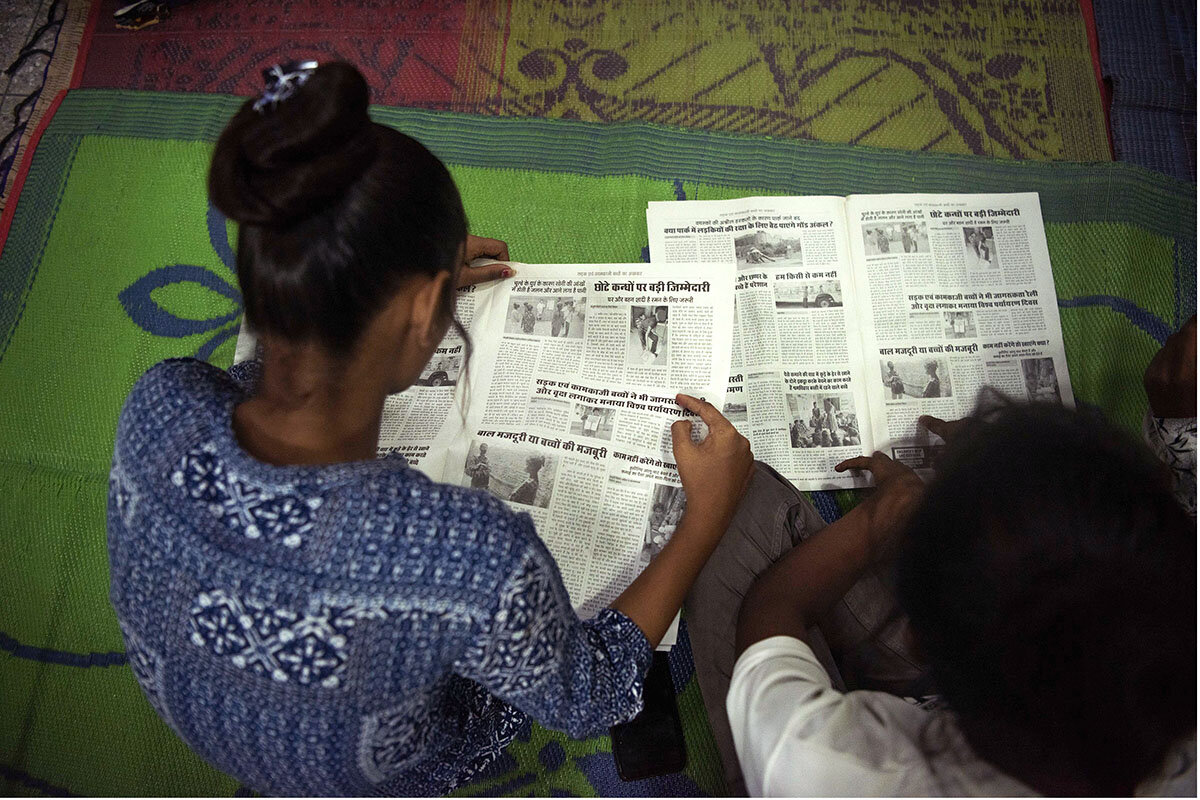

There is no official data on street children in India, but estimates put the figure as high as 18 million, the most of any nation in the world. Advocates say mainstream media rarely covers this extremely vulnerable population. One group seeks to change that by handing the reporter’s notebook over to kids.

Balaknama, meaning “the voice of children,” is a monthly tabloid published in Hindi and English by Chetna, an organization that rehabilitates street kids. Its staff consists of an editor and four reporters – all youth with connections to the street – as well as over 35 batuni (“chatty”) reporters. These are children who provide story leads but can’t write themselves.

The eight-page paper covers issues affecting street kids across northern India, and Chetna reports readership has grown to over 10,000.

Former staff members say Balaknama not only set them up for success personally, but also helped improve conditions for street children throughout the region. The paper offers a rare opportunity to understand the issues that matter to youth on the street.

“Whenever we hear [children’s stories], mostly it is through adults’ viewpoints,” says Soha Moitra, a child rights activist. “What a huge cathartic feeling it actually provides them with, when they are able to express their stories in their own language.”

India’s street kids rarely make headlines – so they write their own

In just three years, Kishan Rathore went from selling snacks and cigarettes outside a liquor store to running monthly editorial meetings and coaching cub reporters on spotting and gathering news. The catch? These reporters are 12 years old, and their editor, Mr. Rathore, is 17.

They write for the only newspaper by and about India’s street-connected children – a difficult-to-define but extremely vulnerable population of youth who rely on the street for livelihood and/or shelter, and are often inadequately supervised by adults. There is no official data on street children in India, but estimates put the figure as high as 18 million, the most of any nation in the world.

Balaknama, meaning “the voice of children,” is a monthly tabloid published both in Hindi and English by Chetna, a nongovernmental organization that works for the rehabilitation of street-connected children. The eight-page paper features around 40 stories on issues affecting street kids across northern India, and since its first issue in 2003, readership has grown to over 10,000, according to Chetna founder Sanjay Gupta.

Former staff members say that Balaknama not only set them up for success personally, but also helped improve conditions for street children throughout the region via their reporting. For caring adults, the paper offers a unique opportunity to understand the issues that matter to youth on the street, a group that’s often described as “invisible.”

“Rarely do we get to hear children talking about their own stories, about their choices, concerns, quests, and even confusions,” says Soha Moitra, a child rights activist and the director of development support at Child Rights and You. “Whenever we hear them, mostly it is through adults’ viewpoints. It is we the adults who usually portray them as we see them through our own lenses.”

She believes Balaknama exemplifies the growth that can happen when we encourage and empower children to speak freely. “What a huge cathartic feeling it actually provides them with, when they are able to express their stories in their own language and give vent to their pent-up emotions,” Ms. Moitra says.

Becoming a Balaknama reporter

The paper currently has an editor, Mr. Rathore, and four reporters. There are also over 35 batuni (“chatty”) reporters – children who provide leads for the stories but can’t write themselves – working for the tabloid in at least three areas including New Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh.

Mr. Gupta, Chetna director and Balaknama mentor, says the idea for Balaknama hit him during a community meeting with street children in 2003. “Those days, the newspapers were publishing reports about the missing dog of an Indian celebrity. A child in the meeting stood up and said that a dog had made it to the headlines, but not the street children who go missing,” he says.

Balaknama seeks to change that by handing the reporter’s notebook to the kids.

The children’s journey typically starts with education intervention by Chetna; then come the weekly support group meetings where kids are encouraged to talk about the challenges they’re facing. For Shambhu, a former Balaknama editor who goes by one name, this was his on-ramp to journalism.

Shambhu was 8 years old when he and his father moved from Bihar state to New Delhi, where the duo spent their days selling cucumbers from a handcart at the Nizamuddin railway station. Chetna activists convinced Shambhu’s father to allow his son to attend classes for a half-hour each day, and later, at a weekly support meeting, Shambhu mentioned how a police officer would beat him and other children working at the station.

“The news was published in Balaknama, and I felt really good that something I had said was printed,” he says, adding that the police officer never beat him or any other child at the station again.

Shambhu was promoted to reporter after working as a batuni reporter for two years, and he eventually took over as editor of Balaknama, a position in which he repeatedly witnessed the power of street kids’ testimony.

In a 2016 issue, Balaknama reporters wrote about how police would ask street children to pick up abandoned dead bodies from the railway tracks in Agra, a city in Uttar Pradesh. “After the story was printed in Balaknama, it reached NCPCR [National Commission for Protection of Child Rights, a government-run body] and they issued a notice and asked to put a stop on this practice,” says Shambhu, who is now 22 years old.

He says that authorities also responded to another story out of Agra about a government-run school feeding children spoiled milk, and that many national newspapers have followed up on the articles as well.

After his affiliation with the paper, Shambhu finished his schooling and got a job at a private school where he teaches children from underprivileged families. He is currently pursuing a bachelor’s degree.

Hitting the streets

Jyoti, another former editor of Balaknama, has also had a dramatic life trajectory. Now 22, Jyoti spent most of her childhood living under overpasses in Delhi, begging at traffic lights and sifting through garbage for valuables in an effort to support her family.

She made $2 to $3 a day begging and ragpicking, sometimes for 18 hours straight. During this period, Jyoti, like other kids in her community, struggled with drug addiction and sexual harassment.

An activist from Chetna reached out to Jyoti, and after weeks of persistence, she agreed to attend open classes. “There I underwent counseling for de-addiction and began learning how to read and write. My habits changed and I began to lead a hygienic life,” she says.

Jyoti joined Balaknama in 2008 and got a stipend, which allowed her to quit begging and ragpicking. “My life came on track and I could support my family financially. I attended school and now I am in 10th grade,” she says.

Jyoti still contributes to Balaknama as a guest writer while working as a mobilizer for Chetna.

Reflecting back on her Balaknama career, Jyoti says her dogged reporting brings her pride. Jyoti recalls writing in 2015 about how children as young as 9 years old would sell alcohol and drugs in the slums of Delhi. “I visited one such slum and investigated the matter. I came to know how a contractor would hire these kids to sell drugs and alcohol. I published the story and distributed the tabloid in the slum also. Soon after, the contractor stopped hiring the kids,” she says.

Jyoti says she has been instrumental in stopping several child marriages, too.

“I have become a seasoned reporter. Unlike those working in fancy studios, I can report in the harshest conditions,” Jyoti says with a laugh.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

More than peace on the table in Ethiopian talks

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

After two years of civil war, representatives of Ethiopia’s federal government and leaders of a rebellious state have gathered to talk peace. The negotiations, which opened, are fragile. The urgent topic is how to end a humanitarian crisis that threatens wider regional instability.

The conflict has cost half a million lives, displaced millions, and left the state of Tigray – home to 7 million people – on the brink of mass starvation. The humanitarian toll points to deeper stakes in the talks.

Both sides acknowledge the war cannot be won militarily. And last week, the government stated that it “deeply regrets any harm that might have been inflicted upon civilians ... and will investigate such incidents to establish facts and provide redress when and if such unintended harm occurs.” Admissions like those matter, even if they may not be fully sincere.

The war in Ethiopia has devastated the region. Now its parties, and the international partners bringing them to the table, are showing that strategic and humanitarian interests are not incompatible.

More than peace on the table in Ethiopian talks

From the moment of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, observers have worried that it would do lasting harm to international rules meant to preserve the sovereignty of nations, restrain the use of force, and protect innocent life. One place where those rules may now be finding renewal is Ethiopia.

After two years of civil war, representatives of Ethiopia’s federal government and leaders of a rebellious state have gathered to talk peace. The negotiations, which opened today in South Africa and are set to run into the weekend, are fragile. They follow two months of intensified fighting. There is little more on the agenda beyond the hope of setting an agenda.

The urgent topic is how to end a humanitarian crisis that threatens wider regional instability. The conflict has cost half a million lives, displaced millions, and left the state of Tigray – home to 7 million people – on the brink of mass starvation. The United Nations has accused both sides of war crimes.

The humanitarian toll points to deeper stakes in the talks. As the largest and most powerful country in the Horn of Africa, Ethiopia lies in the middle of great power competition in both Africa and around the Red Sea. The contest for influence isn’t just about national or commercial interests. International norms must be reaffirmed, too.

Russia and China view Ethiopia’s war as an internal matter and have sought new investment ties despite humanitarian concerns. That no-strings-attached approach has left Western countries wrestling to stay in the game without surrendering their values. In July, for example, the European Commission approved $80 million for education and health projects, but stipulated that it must be dispersed “outside of government structures.”

“There’s an openness to engage based on progress, and real concerns about China and Russia filling any gaps,” one European diplomat told Politico. “But at the same time, we can’t just throw out our norms and values.”

The talks in South Africa reflect that same approach. They follow months of diplomacy by the African Union, the United Nations, the United States, and Europe. The key to any progress is their demand for an immediate cease-fire and unfettered access to Tigray for relief efforts. Beyond that, they seek cooperation from all sides in finding accountability for atrocities committed during the war.

That insistence on respect for humanitarian norms has already had an effect. Both sides acknowledge the war cannot be won militarily. And last week, the government stated that it “deeply regrets any harm that might have been inflicted upon civilians ... and will investigate such incidents to establish facts and provide redress when and if such unintended harm occurs.”

Admissions like those matter, even if they may not be fully sincere. “States have always sought to interpret legal norms to support their courses of action,” noted two legal scholars at the Liverpool John Moores University, in a recent article in the Netherlands International Law Review. “This in itself highlights the value which is attached to the system of international law and the perceived legitimacy which derives from its invocation.”

At a time of shifting competition between great powers and emerging middleweights, wars anywhere send ripples everywhere. The war in Ethiopia has devastated a fragile region. Now its parties, and the international partners bringing them to the negotiating table, are showing that strategic and humanitarian interests are not incompatible.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

No longer fascinated by extreme weather

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Debbie Peck

When we hear reports of impending storms, it might feel natural to become drawn in by frightful images and dire predictions. But through prayer, we can resist the pull toward fear, and help bring peace and healing.

No longer fascinated by extreme weather

I am fascinated by the power of nature. I love the raging waves of an Atlantic nor’easter or the stillness and freshness of a heavy New England snowfall. Nature is beautiful and inspires moments of awe-inspired love for what we experience. But recently, I realized that this fascination has an alter-ego that can be detrimental to prayer and healing.

One afternoon several years ago, I received a “ping” on my phone of breaking news about a hurricane bearing down on the southeast region of the United States. Although my state was not at risk, I wanted to pray for the people and property in its path. But soon I became transfixed by images of the storm and dire warnings. Instead of praying, I stared in awe at the impending weather and its predicted severity.

Interestingly, the thought came to me to look up the word “fascination.” I discovered its origin is associated with words such as “spellbound,” “allured,” or “attracted irresistibly.” The thought that visual images and news alerts could command my attention that strongly was eye-opening.

Christian Science teaches that God, good, is supreme, all-powerful, the only attraction, and the only Mind. And the Bible’s glorious declaration, “Alleluia: for the Lord God omnipotent reigneth” (Revelation 19:6), is a powerful standpoint for disarming anything that would hold us spellbound and interfere with our desire and willingness to be a healer.

Christ Jesus, who was the greatest healer, demonstrated spiritual alertness. He wasn’t fooled or fascinated by the drama around him. The Bible recounts the story of a severe wind that arose on the Sea of Galilee, causing turbulence and high waves, while Jesus slept peacefully on the boat he and his disciples were on. The disciples, terrified of sinking, woke Jesus and cried, “Carest thou not that we perish?” But the account says that Jesus “arose, and rebuked the wind, and said unto the sea, Peace, be still. And the wind ceased, and there was a great calm” (Mark 4:38, 39).

Jesus’ spiritual poise and mental resolve to bear witness to nothing but God’s presence and power overcame the aggressive display of a storm. His spiritual understanding cut through the fog of the disciples’ fear and frantic behavior in a dangerous gale. With a firm rebuke to the unrest, Jesus stilled the storm.

The Christ, the voice of good that animated all that Jesus said and did, still speaks to us in consciousness. Christ is here to guide and protect us today. In my situation, the prompt to pray about my fascination with the weather was evidence of the Christ disarming the pull toward the potential drama of the situation. I was able to affirm with a joyful heart that God, good, is in control, that God’s power prevails, and that God is the only cause and effect. We reflect the one divine Mind, and have an ability to resist the distracting lure of frightful images.

Many people prayed fervently about the storm that night, and good news arrived in the morning. There was no loss of life, only minor flooding, and little property damage. As news updates pinged my phone, I gratefully learned that the storm petered out throughout the day.

Our earnest desire to help our fellow man is a form of prayer. If there seems to be a pull away from this desire by a fascination with frightening images or dire predictions, we can trust God to provide the solution to dissolve this influence. Knowing “All is under the control of the one Mind, even God” (Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 544), we joyfully affirm that there are no chaotic forces, mesmeric attractions, dramatic events, or power to disable our prayers.

This verse from a hymn captures the spirit needed to rouse ourselves to spiritual alertness and defeat the foe, whether it be fascination or apathy, that would prevent us from praying for our world and our sisters and brothers:

Rouse ye, rouse ye, face the foe,

Rise to conquer death and sin;

On with Christ to victory go,

O side with God, and win!

(Maria Louise Baum, based on hymn by M. H. Tipton, “Christian Science Hymnal,” No. 296, © CSBD)

A message of love

Eyeing the sun

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back tomorrow: We’re working on a story about how America’s No. 1 concern, inflation, is likely to affect the midterm elections.