- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

On the road in Ukraine with the Monitor’s team

Winter has a way of dramatically amplifying the harshness of war – and the courage with which people navigate its challenges.

That’s what has struck Monitor correspondent Dominique Soguel, local journalist Oleksandr Naselenko, and driver Dmytro Yatsenko as they’ve reported in Ukraine this week, including in areas formerly occupied by Russian forces.

Recent Russian attacks on energy infrastructure, for example, have knocked out electricity and heating for more than 1 million households. Emergency crews have leaped into action to restore services as quickly as possible. In the Donetsk region in eastern Ukraine, people are busily chopping wood, while rushing to cover windows and repair roofs shredded by Russian rockets and shells. In the recently liberated town of Lyman, demining squads are working to restore safety. In Kyiv, residents have been scooping up gas camping stoves in anticipation of extended power outages. Meanwhile, amid daily pressures, relatives of prisoners of war work to stay strong, as do children who have lost parents in attacks.

So many people, Dominique says, are extending a helping, healing hand in any and all directions.

“Ukrainians are preparing with calm courage,” she told me by text message. “The resourcefulness of Ukrainians is truly striking.”

Dmytro, for his part, is astonished by the change between 2014, when the war in the east started, and now, in terms of how fast information travels – a testament to dramatic improvements in technology. Also, he says, “The number of people who support Russia has dropped – and the few who do don’t say so openly.”

Oleksandr, meanwhile, takes note of the vast destruction, including the sobering image of bomb craters in children’s playgrounds. Yet, he says, “Despite living under occupation, people have kept their human face. … They keep going. The power and strength of this people is very impressive.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

The politics of inflation: Can Democrats buck history?

Inflation is top of Americans’ minds heading into the midterm elections, and economic pain in the household wallet may translate into trouble for Democrats at the ballot.

-

Erika Page Staff writer

Two weeks before Election Day, most Americans are pessimistic about the economy – with inflation leading the list of economic concerns.

After weeks of touting legislative wins aimed at helping struggling Americans, President Joe Biden has gone negative, training his sights on a Republican Party that appears poised to take over one if not both houses of Congress. A GOP victory on Nov. 8, he says, would result in efforts to cut Social Security and Medicare, leading to a likely government shutdown, a risk of default on the national debt, and even worse inflation.

But the economic messaging may not help Democrats much. History shows that voters tend to hold presidents and their parties responsible for the economy – whether they are or not.

In Los Angeles, professional bassoonist and longtime Democrat Alex Garcia is now considering voting Republican on Nov. 8.

“We’re all feeling it,” he says in a phone interview between teaching a class and an evening opera performance. “Your energy bill is more expensive; gasoline is more expensive. You get nickeled and dimed everywhere, and those things add up. After a while, it’s just like, ‘How long are we willing to put up with this?’”

The politics of inflation: Can Democrats buck history?

Two years ago, Alex Garcia – along with nearly everyone he knew in Los Angeles – voted for Joe Biden.

“I was [once] as far left as they came,” the professional bassoonist and music instructor says, talking on the phone in a spare hour between teaching a class and playing in an evening opera performance. “But this year I’m probably considering voting Republican.”

The reason? Inflation.

“We’re all feeling it,” says Mr. Garcia, who drives back and forth to Las Vegas at least once a month for work. “Your energy bill is more expensive; gasoline is more expensive. You get nickeled and dimed everywhere, and those things add up. After a while, it’s just like, ‘How long are we willing to put up with this?’”

Two weeks before Election Day, most Americans are pessimistic about the economy – with inflation leading the list of economic concerns.

After weeks of touting legislative wins aimed at helping struggling Americans, President Joe Biden has gone negative, training his sights on a Republican Party that appears poised to take over one if not both houses of Congress. A GOP victory on Nov. 8, he says, would result in efforts to cut Social Security and Medicare, leading to a likely government shutdown, a risk of default on the national debt, and even worse inflation.

“Republicans are doubling down on their mega MAGA trickle-down economics that benefits the very wealthy,” President Biden said this week, referring to former President Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan. Mr. Biden also continues to insist that his party is on the right track, “building a better America for everyone.”

But the economic messaging – including efforts to blame inflation on others, such as Russian President Vladimir Putin – may not help Democrats much, political strategists say.

“The default setting in American politics since the New Deal is that presidents and their political parties are held responsible for the performance of the economy – whether they are or not,” says William Galston, domestic policy adviser in the Clinton White House.

The view from the farmers market

The economy is the top issue for voters, with 79% saying it will be “very important” to their vote, according to the Pew Research Center.

And while the White House can point to strong employment numbers, that may be of little comfort to many, given that the cost of living has risen noticeably. In September, inflation came in at 8.2% year over year, and Americans are paying higher prices for everything from food to consumer goods to energy.

At the same time, 30-year fixed-rate mortgages now average 7.16%, the highest level since 2001, pushing plans to buy a home off the table for many Americans.

Tyler Hirsch is one of them. As the late morning chill thaws at Copley Square farmers market in Boston, Mr. Hirsch waits for his first customers to arrive. Business is slow, with few passersby seeking his pad thai meal kits.

Mr. Hirsch says sales have been unusually quiet for some time now. Late October is typically when he closes out the busiest time of the year, but this fall “we just never saw it.”

He blames what he sees as the onset of a likely recession, prompted by the federal government’s response to high inflation. Soaring prices were bad enough for someone in the food industry. But now his main source of frustration is the Federal Reserve’s multiple interest rate hikes since March.

The vendor had been hoping to buy a house, but given the current situation, “it’s not going to happen anytime soon.”

“The cure is worse than the actual inflation,” he says. “It feels like they’re purposefully squeezing us.”

Neither political party has ever satisfied Mr. Hirsch entirely, and he’s voted back and forth over the years. But this year, his mind has been made up for months.

“I’m voting R down the ticket,” he says.

“Whip Inflation Now”

Anyone of a certain age may remember President Gerald Ford speaking from the Rose Garden wearing a button that said “WIN” – “Whip Inflation Now.”

The oil shocks of the early 1970s had produced inflation topping 12%, and in the summer of 1974, President Ford faced pressure to bring it down. “To help save scarce fuel in the energy crisis, drive less, heat less,” he told Americans.

The effort was ridiculed.

“It’s viewed – even by Republicans who worked with him, and I’ve interviewed some of them – as one of the most colossal public relations failures of all time in a presidency,” says Russell Riley, a historian at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center.

Today, amid intense polarization, many voters may well stick with their usual partisan habits, even with high inflation. Dan Wilson, a Democrat from Georgia who ran for Congress in 2020, can’t imagine anyone in his community voting any differently from previous elections.

“I have not stumbled across that unicorn yet,” says Mr. Wilson, a retired artist, writer, and teacher. Most political viewpoints in his heavily Republican county were baked in a long time ago, he says. “I don’t think inflation is going to change that vote.”

Nor will Mr. Biden be resurrecting the WIN button anytime soon.

But he’s tried other ways either to deflect blame or show the American people he’s on the case. He cites “corporate greed,” and has repeatedly blamed the Russian president, whose war on Ukraine has skewed energy markets, by referring to “Putin’s price hike.”

The Biden administration deliberately named its big legislative package including tax reform, lower prescription drug prices, and clean energy investment the Inflation Reduction Act. But with inflation still near 40-year highs, the public seems unconvinced.

Administration officials’ early insistence that inflation was “transitory” – despite pushback by some high-profile Democratic economists, such as former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers and former Council of Economic Advisers Chair Jason Furman – has also hurt the Biden team’s credibility.

Much of the blame for inflation goes to pandemic-era overspending by the government – including the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan stimulus bill of 2021 – and the Federal Reserve’s failure to raise interest rates soon enough, says Veronique de Rugy, a political economist at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.

In addition, she says, “there’s been no talk whatsoever about repaying the debt, which is actually fairly unique in our history.”

Like many economists, Professor de Rugy predicts the U.S. is heading into recession, though not immediately. Third quarter numbers due out Thursday are expected to show positive economic growth. But when recession does hit, she says, “there will be no soft landing.”

Some argue the Fed’s failure to start raising interest rates sooner may have had a political dimension.

Only this past spring, after Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell had been confirmed by the Senate for a second term, did the Fed start raising rates, Harvard economist Kenneth Rogoff notes in the journal Foreign Affairs.

“If the administration had wanted the Fed to raise interest rates sooner, as some later argued it did, the right move would have been to reappoint Powell in the summer of 2021, giving him a clear mandate to act as the Fed saw fit,” writes Professor Rogoff.

Patterns

Behind Britain’s turmoil, an unfinished Brexit

Underlying Britain’s economic crisis are six years of confusion over what shape Brexit should take. Can new Prime Minister Rishi Sunak cut the Gordian knot?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

As he took office on Tuesday as Britain’s latest prime minister, Rishi Sunak mentioned three factors he said had contributed to what he called the “profound economic crisis” facing the United Kingdom.

There was the war in Ukraine, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the mistakes of his predecessor, Liz Truss. But he ignored another key cause – the unfinished business of Brexit, a challenge that has defied three Conservative prime ministers already.

Brexit has not, so far, proved a path to the “sunny uplands” that its boosters promised six years ago in their successful referendum campaign. It has, in fact, dampened trade and foreign investment. And part of the problem is that Brexit remains undefined.

Its supporters could not agree among themselves what kind of Brexit they wanted, which has made the whole issue a political minefield for any British leader. Boris Johnson failed to do a final deal with the European Union, and so did his predecessor, Theresa May. Ms. Truss did not have the time to try.

Mr. Sunak may prefer to focus on the immediate crisis for now, but unless he clears up the Brexit confusion, it will only make a way out of that crisis harder to find.

Behind Britain’s turmoil, an unfinished Brexit

The tone was stern, and the message sober: Britain, according to its latest prime minister, “is facing a profound economic crisis.”

But more striking than the confidence with which Rishi Sunak proceeded to lay out his policy priorities was the casual manner in which he avoided facing an even deeper challenge – one that has defied three other Conservative prime ministers in six years and likely holds the key to his own success or failure in office.

It is the unfinished business of Brexit: finally deciding on the shape of Britain’s relationship with the 27 countries of the European Union, the trading bloc it voted to leave in a 2016 referendum.

And that is a conundrum with implications not just for Britain, but other populist political campaigns like Brexit: how to convert angry rhetoric and rhapsodic promises into workable, real-world policies.

For Mr. Sunak, resolving that puzzle is economically urgent, but politically daunting.

Britain’s ill-defined post-Brexit ties with the EU aren’t the main cause of the “profound economic crisis.” He rightly highlighted others: the war in Ukraine, the pandemic, and the “error” of his immediate predecessor, Liz Truss, in announcing a radically new economic blueprint that spooked the financial markets.

But Brexit is a key factor, too. It has dampened trade and foreign investment. It has fueled consumer price rises and skilled labor shortages. According to an official estimate, it is poised to shave 4% off Britain’s future gross domestic product.

And a range of unresolved Brexit-related issues could mean further trouble.

London and Brussels are still locked in a dispute over border checks between Northern Ireland, which is part of Britain, and EU-member Ireland. That carries the risk of an all-out trade war.

Nor has London agreed with the EU on how the two sides can ensure that the regulations governing their crucial financial services industries are compatible.

Mr. Sunak’s problem is that getting final agreement on the exact nature of Britain’s future relationship with the EU is not just an economic question.

It is, above all, political, with roots going back to the referendum.

The impetus for holding the plebiscite came from a passionately anti-EU minority inside the Conservative Party. The party’s then-leader, Prime Minister David Cameron, favored staying in. He was confident that, in a reasoned debate, Britain’s strong economic and trade interests in remaining part of the EU would carry the day.

Pro-Brexit leaders could not even agree on a shared vision of how Britain would organize its trade and economic affairs after leaving the EU. So the campaign became a broad-brush populist crusade, tapping into a whole range of economic and political grievances, promising the “sunny uplands” of a brighter future.

And Brexit won.

The margin was narrow, with more deprived areas of the country supporting Brexit, while Londoners and younger voters overwhelmingly opposed it. So did voters in Scotland, lending new energy to calls for independence from the United Kingdom.

The overall legacy was a country deeply, angrily divided over the issue – while Britain’s post-Brexit relationship with its nearest and largest trading partner was yet to be agreed upon, even among those in favor of leaving.

Successive Conservative prime ministers have tried to complete the process.

Theresa May sought a transition period during which existing arrangements would remain in place until a new relationship had been worked out, but failed to get a majority of members of Parliament to back her. Next came Boris Johnson, the leading voice on the Brexit campaign trail. He did get Britain out of the EU; in fact, his promise to “get Brexit done” won his party a thumping election victory in 2019.

But his deal with Brussels didn’t get it done. Key issues remained unresolved.

And then came Ms. Truss. She was the first leader with a fully coherent vision of post-Brexit Britain, dubbed “Singapore-on-Thames.” Unchained from EU ties, she believed, Britain could transform itself into a low-tax, low-regulation, business-friendly, high-skills economy to outcompete former EU partners, and strike new trade deals with economies such as India and the United States.

It wasn’t that plan itself that toppled Ms. Truss, making her the shortest-ruling prime minister in British history. Rather, it was the ill-prepared way in which her initial tax plan was sprung on the markets.

So now, it’s Mr. Sunak’s turn. He has yet to clarify his own vision of Britain’s post-EU future.

He does seem to share Ms. Truss’ view that low growth, low skills, and low productivity are the British economy’s major failings. But he does not appear to believe that “Singapore-on-Thames” is a realistic solution.

He may be hoping to put off resolving Brexit for now, since everyone is focused on the more immediate crisis.

But as a former finance minister, he is fully aware that the confusion over Brexit’s shape is causing damaging economic dislocations. And that until a final plan is agreed upon with the EU, those dislocations will only make it harder to recover from the crisis.

Displaced by war, Ukrainians accept trauma care – warily

Ukrainian civilians fleeing the front lines are often reluctant to admit suffering psychological trauma. It takes empathy and tact to penetrate their ingrained stoicism.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Vladimir Klimenko Contributor

Nadezhda Galash, a psychologist working with Ukrainians fleeing the war, has a practiced eye. As displaced people file off buses and into her reception center, she says, “I can just look at a person and see that he or she really needs help.”

Among those seeking safety are victims of sexual violence, who are often extremely reluctant to recount their experiences. Indeed, the teams of psychologists and social workers sorting out who needs care find themselves struggling to dispel a Soviet-era stigma attached to mental health counseling.

Raised in a spirit of stoic endurance, many older citizens who grew up in the USSR view therapy as taboo, and are reluctant to seek help. Psychologists encourage their patients to unlock the doors of their steely exteriors.

“Maybe it will be only one time, but a person needs an opportunity to cry,” says psychologist Alyona Orel.

Though it is hard to predict how long Ukraine’s war-related psychological troubles will last, experts agree that the sooner people get treatment, the better. Repressing painful memories now will make it harder for society to heal, says case manager Ekaterina Kutyeva.

“This is the only way forward to creating a healthy society,” she says.

Displaced by war, Ukrainians accept trauma care – warily

Social worker Marina Kucherenko cradles a cup of coffee, sitting at a table in a spacious, sparsely furnished room decorated mainly with large houseplants. The greenery is soothing, and it needs to be; this is the headquarters of Zaporizhzhia’s mobile mental health unit, and Ms. Kucherenko knows she will soon be called on to help someone in deep distress.

On a recent visit, she and her psychologist partner encountered a heavily inebriated mother. “When we asked her why she drank so much, she said it was the stress of war,” Ms. Kucherenko says.

She recalls the mother’s rationale for being drunk. “I can’t watch television. I can’t read the news. I can’t even listen to the sound of sirens going off four times a day. I can’t handle it when the sirens go off in the middle of the night.’’

In Zaporizhzhia, 25 miles from the front line, as in much of Ukraine, such pressures are compounded by economic hardships: Gross domestic product has dropped by more than 30% since the war began eight months ago, inflation is running at 23%, and both well-paying jobs and housing are in short supply as people flee from Russian occupiers or artillery duels to the city’s relative safety.

That means that when Ms. Kucherenko or her colleagues knock on doors, “the first reaction is often aggressive,” she says, and the mobile team needs to show a mix of assertiveness, empathy, and tact.

Those are qualities needed across town, as well, where another team of psychologists and social workers has transformed a commercial exhibition hall into an intake hub for people displaced by the war.

Most disembark from rescue vans and buses with only a few items of luggage. Some appear stoic, while others wear exhausted, bewildered expressions on their faces. All of them have been streaming into the city from the 600-mile front line, a zone of active rocket duels stretching from the eastern Donbas territory, the southern part of the Zaporizhzhia region, and areas around the embattled city of Kherson, closer to Crimea.

A Soviet-era stigma

Psychologist Nadezhda Galash describes how she and other experienced colleagues can often identify the most traumatized newcomers as soon as they walk through the door.

“I see the fear in their eyes. I can just look at a person and see that he or she really needs help,” says Ms. Galash. She knows, too, the range of traumas that people have endured, and how difficult it is for the survivors to begin describing their ordeals. Like most of her team, she herself fled from the Russian-occupied east of Ukraine.

“We work first and foremost with people who have suffered from sexual violence,” explains Alyona Orel, a psychologist who used to work in a shelter for battered women. “This is a difficult topic, so naturally during the first or second session a person may not open up. This could be a lengthy process.”

“Sometimes we have to bring people around,” adds Ms. Galash. “We can’t just ask people directly, ‘Were you the victim of sexual violence?’”

In addition to juggling high caseloads and steering displaced people toward available services, Ukraine’s psychologists find themselves struggling to dispel a lingering Soviet-era stigma attached to mental health counseling. Raised in a spirit of stoic endurance, many older citizens who grew up in the USSR view therapy as taboo and are reluctant to seek help when they need it.

In a culture that prizes such stoicism, Ms. Orel encourages her patients to unlock the doors of their steely exteriors.

“Maybe it will only be one time, but a person needs an opportunity to cry,” she says. “I can’t tell you how often this happens, but my patients still apologize for their tears, for even having come to see me and, as they put it, wasting my time.”

“What people need now is information ... to help them overcome their own feelings of fear and shame,” says case manager Ekaterina Kutyeva.

“The main thing is that people should not shut themselves off from help,” she adds.

Trauma: best dealt with now

Psychologist Oksana Mykhaylenko runs the Perspektiva Center for Social Partnership, one of Ukraine’s leading nongovernmental organizations working with wartime survivors of sexual violence. When Russian troops seized Novaya Kakhovka, where the NGO had its base, Ms. Mykhaylenko’s group moved out and dispersed its operations throughout the rest of Ukraine.

These days she and her team do much of their therapeutic work with survivors online. In her case that means communicating remotely with patients and colleagues from the western Ukrainian city of Chernovtsy.

Fortunately, the logistics underpinning their work remain intact, for the time being. The country’s information technology sector is still quite robust, and the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced many companies and schools to work online, served as a dress rehearsal for new wartime challenges.

But Ms. Mykhaylenko says that the biggest challenges are neither technical nor logistical, but psycho-emotional, particularly when it comes to the extremely sensitive issue of wartime rape.

Ms. Mykhaylenko is especially concerned about the physical safety and psychological health of people living behind Russian lines.

“A large number of doctors fled Russian-controlled territory,” she says, and Ukrainian mobile emergency units cannot get past the Russian checkpoints.

Online and telephone consultations may be options in most of the country, but in the Russian-occupied regions, this type of communication is fraught with risk.

“There is a big problem of confidentiality,” says Ms. Mykhaylenko, who points out that the few remaining available phone lines and even internet channels can be monitored, making victims of sexual violence even more unwilling to talk about it.

Though it is hard to predict how long Ukraine’s psychological troubles will last, experts agree that the sooner people are treated, the better.

Repressing painful memories will only make it harder for society to heal later, says Ms. Kutyeva. The time to begin addressing these problems, she argues, is right now.

“This is the only way forward to creating a healthy society,” she insists. “Otherwise, what kind of society will we have in the future? We all need to think about what we will be facing once the war ends.”

Commentary

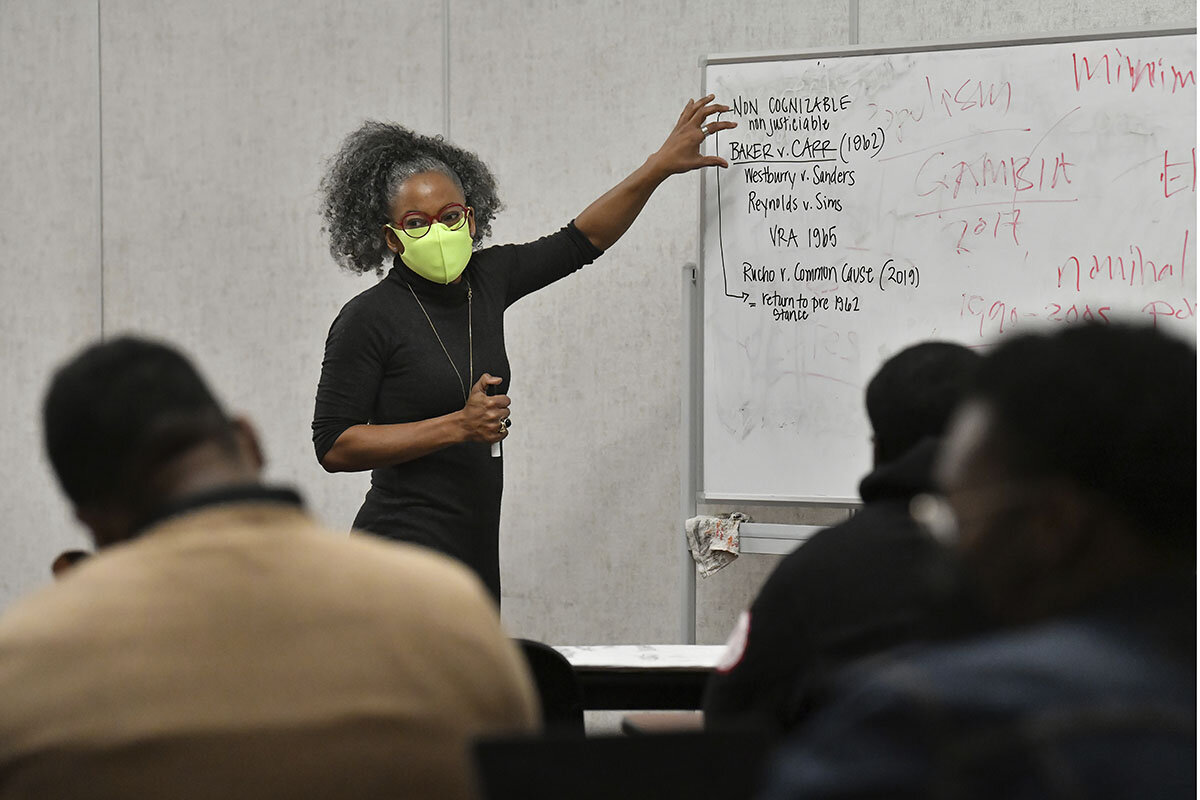

Historically Black, historically underfunded: A higher-ed reckoning

Many historically Black colleges and universities grew out of a “separate but equal” approach to educating Black people, but the promise of equality in funding often hasn’t been honored.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

When I stepped onto the campus of Florida A&M University in Tallahassee as a freshman more than 20 years ago, I immediately felt at home. It had a welcoming spirit that alumni from historically Black colleges and universities like mine speak of glowingly.

That sense of belonging continues to attract Black students today. An initial analysis of this fall’s enrollment figures released by the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center shows that undergraduate enrollment overall shrank again. But HBCUs experienced 2.5% growth.

Yet these institutions experience persistent financial challenges, often caused by states not meeting their requirement to match certain types of federal funding.

Both Tennessee and Maryland are needing to redress cumulative HBCU underfunding of up to half a billion dollars apiece. And last month, six students from my alma mater entered a class-action complaint against Florida, noting that the cumulative effect of funding shortfalls since the late 1980s is more than $1.3 billion, according to the Tallahassee Democrat.

Funding Black schools fairly would not only support their success, but also acknowledge past disparities and indicate a future commitment to true equity – to welcoming these institutions into higher education’s full range of opportunities as warmly as the schools welcome their students.

Historically Black, historically underfunded: A higher-ed reckoning

When I stepped onto the campus of Florida A&M University in Tallahassee as a freshman more than 20 years ago, I immediately felt at home. It had a welcoming spirit that alumni from historically Black colleges and universities like mine speak of glowingly – a spirit that extends far beyond graduation.

That sense of belonging continues to attract Black students, despite the schools’ long-standing lack of funding and history of violence and threats of violence against them. On Aug. 30, the Department of Homeland Security reported 49 bomb threats targeting HBCUs in the first eight months of the year. Even so, enrollment in many HBCUs is up.

An initial analysis of this fall’s enrollment figures released by the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center on Thursday shows that undergraduate enrollment overall shrank again for a two-year decline of 4.2%. But HBCUs experienced 2.5% growth in undergraduate enrollment this fall, propelled by a 6.6% increase in freshman enrollment, leading to a 0.8% increase since 2020.

A surprising finding

That could be good news far beyond those campuses. The atmosphere at HBCUs, one researcher posits, may be tied to higher elementary school math scores, regardless of the race of the teacher.

Last month, The Hechinger Report noted a study indicating that having a teacher – whether Black or not – who trained at a historically Black college or university led to better math results for Black students in third through fifth grade in North Carolina between fall 2009 and spring 2018.

“I thought that this has to be wrong somehow because so many papers have found an effect for a Black-teacher Black-student match,” Lavar Edmonds, a graduate student in economics and education at Stanford University, told Hechinger. But no matter how many different times or ways Mr. Edmonds conducted his analysis, the results were the same.

The study has not been peer reviewed yet, but if the researcher is correct, it speaks well of the schools’ relevance and of the role of diversity at these institutions. (In 2020, 24% of HBCU students were not Black, up from 15% in 1976.) Mr. Edmonds, who is Black, speculates that what led to the increased scores might be the schools’ hospitable spirit.

“Many of my family members went to HBCUs and a recurring theme is how they found it more welcoming.” Mr. Edmonds told Hechinger. “They felt more at peace, more at home at an HBCU. … I think there is a component of that in how a teacher conveys information to a student. If you’re getting more of that environment, yourself, as a student at these institutions, I think it makes a difference in your disposition as a teacher.”

Persistence despite inequities

The peace that Mr. Edmonds is talking about truly passes understanding when looking at some of the challenges that face HBCUs. Along with the recent spurt of bomb threats, there are persistent financial challenges. A few of the better-known schools have hundreds of millions in their endowment; Howard University, the wealthiest, has said its endowment goal of $1 billion is within reach. But that is far from typical. “The value of all HBCU endowments in 2020 combined is just 11 percent of Harvard’s endowment in 2020,” reports The Plug, a Black journalism and insights company.

Why the disparity? The best apples-to-apples explanation concerns land-grant institutions established under the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890, the second of which was designed to make higher education available to Black people, especially in the former Confederate states. Some of the schools established under that act are today’s HBCUs, but for decades those 1890 land-grant institutions were deemed ineligible for the funding that 1862 institutions received, although both groups have the same “legal standing.” Efforts in the 1970s began to address these disparities, but stark inequities persist.

For example, despite a requirement for state funding to match dollar for dollar certain types of federal funding for land-grant institutions, states have not kept up their end of the bargain – often providing more funds than required to white institutions while “waiving” funding for Black schools. This year, both Tennessee and Maryland are needing to redress cumulative HBCU underfunding of up to half a billion dollars apiece.

Needed: A warm and well-funded welcome

Just last month, six students from my alma mater, Florida A&M, entered a class-action complaint alleging that Florida “has systematically engaged in policies and practices that established and perpetuated, and continue to perpetuate, a racially segregated system of higher education.”

The complaint compares state funding for the University of Florida (a majority-white school) and Florida A&M, both land-grant institutions. One example notes that the latter’s 2019 appropriations “amounted to $11,450 per student, compared … to $14,984 per student” for the University of Florida. The cumulative effect of such shortfalls since the late 1980s is more than $1.3 billion, the Tallahassee Democrat reports.

The Biden administration, and previous others, have spoken to the importance of HBCUs. But students and their families need more than observances. Funding Black schools fairly would not only support their success, but also acknowledge past disparities and indicate a future commitment to true equity – to welcoming these institutions into higher education’s full range of opportunities as warmly as the schools welcome their students.

In Pictures

The brothers saving India’s unappreciated scavenger birds

Two brothers in India began treating injured birds for a simple reason: because nobody else was. The result? Thousands of animals saved.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Oscar Espinosa Contributor

-

Laura Fornell Contributor

When they were teenagers, Saud and Nadeem once found a wounded black kite and took it to the local bird hospital. But the hospital was run by Jains, whose vegetarian beliefs prohibited treatment of the carnivorous raptor. That scenario repeated as they grew up, until one day the brothers came up with a plan: They would treat the birds themselves.

Completely self-taught, they learned to care for the birds by watching videos, reading books, and seeking advice from a local veterinarian, funding bird care with income from their family business. They’ve now formalized their makeshift hospital to the point where they can accept donations.

Most of the 2,500 or so birds that come to them each year have their wings cut by manja, a cotton string coated with crushed glass, used by kite-flying enthusiasts. The sanctuary sees a surge of wounded birds every year around Aug. 15, when Delhi’s sky is filled with kites to celebrate India’s Independence Day.

“It’s clear that the black kite is not the most beloved animal in the city,” says Nadeem, who, like his brother, doesn’t use a surname. “Who knows, if people were aware that these scavenger birds help the city reduce its waste by getting rid of thousands of kilos of garbage they feed on every day, maybe the perception of them would change.”

The brothers saving India’s unappreciated scavenger birds

In a small room beneath the unpaved streets of the village of Wazirabad, in northeast Delhi, Saud tends to a black kite bird while his brother Nadeem does quality control on one of the boxes of the soap dispensers they sell. “After this operation it will be able to fly as if nothing had happened,” explains Saud as he stitches up the bird.

The cluttered room in the basement of a three-story building that floods every time it rains serves as office and storage space for the family business, as well as an operating room for Wildlife Rescue, the bird sanctuary founded and run by the two brothers.

As teenagers, Saud and Nadeem, who don’t use surnames, found a wounded black kite and took it to the local bird hospital run by Jains, whose vegetarian beliefs prohibited treatment of the carnivorous raptor. That scenario repeated as they grew up, until one day they decided to treat a bird themselves.

“And that’s how it all started,” Saud recalls. “Every time we found an injured bird, we would rescue it to try to heal it.” Completely self-taught, they learned to care for the birds by watching videos, reading books, and seeking advice from a local veterinarian, funding bird care with income from the family business.

In 2010, they registered their rehabilitation center as an association, and began to receive some donations. In 2013 they moved from Old Delhi into a building in Wazirabad, which houses Saud’s family as well as the birds.

Alongside the two brothers is their cousin Salik, who takes care of the animals, feeding them, keeping the cages clean, rescuing them, and when the time comes, releasing them.

Most of the birds that come to them have their wings cut by manja, a cotton string coated with crushed glass, used by kite-flying enthusiasts. The sanctuary sees a surge of wounded birds every year around Aug. 15, when Delhi’s sky is filled with kites to celebrate India’s Independence Day.

Saud checks one of the 20 black kites that have arrived that day. The bird is still entangled in the manja, which has cut its right wing.

Nadeem estimates about 2,500 birds pass through their shelter every year. “It’s clear that the black kite is not the most beloved animal in the city,” he says. “Who knows, if people were aware that these scavenger birds help the city reduce its waste by getting rid of thousands of kilos of garbage they feed on every day, maybe the perception of them would change.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

North Koreans embrace truth over consequences

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

North Korean leader Kim Jong Un has been busy this year flexing his military muscles. His reclusive country has held an unprecedented number of weapons tests. It appears ready to conduct a seventh underground nuclear bomb test. Why now? One reason may be that the third leader of the Kim dynasty needs to shore up loyalty by bedazzling his people. The economy is in shambles, but most of all, too many North Koreans are bypassing state propaganda to learn the truth about the outside world.

More people are watching foreign news and cultural shows on smuggled computer devices, according to a rare survey by the South Korea-based Unification Media Group. The survey found 79% of North Koreans watch foreign videos at least once a month. The most popular entertainment is South Korean dramas, such as “Squid Games,” along with K-pop music.

More tellingly, 88% of those surveyed had heard or experienced punishment for breaking a harsh 2020 law aimed at curbing foreign information. The survey reveals a hunger for truthful information despite a fear of severe punishment.

An embrace of honest and open communication could be shaping the Korean Peninsula even more than the embrace of more advanced weaponry.

North Koreans embrace truth over consequences

North Korean leader Kim Jong Un has been busy this year flexing his military muscles. His reclusive country has held an unprecedented number of weapons tests, even sending a ballistic missile over Japan. It appears ready to conduct a seventh underground nuclear bomb test, the first in five years.

Why now? One reason may be that the third leader of the Kim dynasty needs to shore up loyalty by bedazzling his people. The economy is in shambles, but most of all, too many North Koreans are bypassing state propaganda to learn the truth about the outside world.

More people are watching foreign news and cultural shows on smuggled computer devices such as micro SD cards, according to a rare survey conducted clandestinely from June to August by the South Korea-based Unification Media Group (UMG).

The survey found 79% of North Koreans watch foreign videos at least once a month. The most popular entertainment is South Korean dramas, such as “Squid Games” and “Crash Landing on You,” along with K-pop music.

More tellingly, 88% of those surveyed had heard or experienced punishment for breaking a harsh 2020 law aimed at curbing foreign information or media content.

The survey reveals a hunger for truthful information despite a fear of severe punishment. The regime seemed particularly alarmed this year when it found a group of soldiers singing “like South Koreans” in a military talent show, even doing comedy stand-ups. It is also trying to stop popular usage of a South Korean slang term from “Crash Landing on You” that sarcastically means “You think you’re the general or something?” Mr. Kim is often referred to as the general.

To ensure conformity in ideology and a near-worship of the Kim family, the regime tightly controls the number and types of radios, TVs, and computers. Still, a black market across the border with China has brought in illegal devices, such as thumb drives, loaded with illegal content. “Foreign countries give you fresh, unpolished news, but all of our newspapers and broadcasts are fabrications and fake,” one North Korean woman told Daily NK news, an arm of UMG.

The increase in flow of information could lead North Koreans to assume a liberty of conscience leading to a liberty from fear. Even in South Korea, the government began moves this year to end a 1948 legal prohibition on North Korean media. “Removing that restriction ... would be another step toward moving on from the past, as well as joining the United States and other countries in championing freedom, liberty, and access to information,” Jean Lee, a fellow at the Wilson Center, told The Peninsula publication.

An embrace of honest and open communication could be shaping the Korean Peninsula even more than the embrace of more advanced weaponry.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

From mental darkness to light

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Patricia Brugioni

God’s healing love is powerful enough to break through even the most overwhelming dark feelings. In this short podcast, a woman shares how God’s love brought hope and healing that turned her life around completely.

From mental darkness to light

To listen, click the play button on the audio player above.

For an extended discussion on this topic, check out “How can I think about...depression?,” the Oct. 3, 2022, episode of the Sentinel Watch podcast on www.JSH-Online.com.

A message of love

Surrounded by color

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Tomorrow, we’ll look at the growing difficulty of getting an accurate read on GOP races – between candidates’ disinterest in talking to journalists and voters who don’t respond to polls.