- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- As Israel votes (again), Arab union cracks and Jewish right unites

- Geothermal 2.0: Why Cornell University put a 2-mile hole in the Earth

- ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’: A German retelling for a modern time

- In ‘Till,’ the power of a mother’s love

- Where ‘the draft’ serves the nation, and the draftee too

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How one school makes kindness a visible priority

Yvonne Zipp

Yvonne Zipp

In his 42 years at The Christian Science Monitor, David Clark Scott traveled the world: He roamed throughout Latin America as the Mexico City bureau chief and reached into Southeast Asia as Australia bureau chief. He supported and counseled dozens of Monitor reporters as international editor. When he wrote columns, his favorite stories were of people taking the time to help one another. He even produced an entire podcast.

In these times, when everyone is fixated on what went wrong, it’s important to look for what is going right, and sometimes, frankly, it needs to be at the top of the page.

Dave passed on this week. On his last day of work, he pitched three stories, any one of which would have made a lovely column. But, he told me, he’d already “put a call in to the principal at the Nansemond Parkway Elementary School cuz, well, that’s the intro that tugs at my heart.”

It did mine, too, so I wanted to share it with you.

The Nansemond students in Suffolk, Virginia, have been learning a new language: sign language, so they can communicate with food nutrition service associate Leisa Duckwall, who is deaf.

It started with a fourth grade teacher, Kari Maskelony, who has deaf family members and started teaching her class. This month it spread when Principal Janet Wright-Davis decided the whole school would learn a new sign every week in honor of Disabilities Awareness Month.

“I don’t think [the students] saw it as a disability,” Dr. Wright-Davis told me over the phone. It was just a new way to communicate. Her biggest surprise? “How much they want to learn it.”

Their favorite sign: pizza.

The difference in the cafeteria is palpable, she says. Instead of pointing, as they used to, the students sign their requests. “She’s smiling and they’re smiling, and it’s just a different environment,” says Dr. Wright-Davis.

Ms. Duckwall has come to morning announcements to teach everyone new signs and has signed that day’s menu. Dr. Wright-Davis gets stopped in the hall by students signing good morning and wanting to show her what they’ve learned. Instead of stopping at the end of this month, the students are going to keep learning all year.

The school had its Trunk or Treat event Thursday evening, and the children were signing as they celebrated Halloween.

“One gentleman came out, and he was signing,” Dr. Wright-Davis says. It made her realize the lessons wouldn’t be confined to the lunchroom or even the school. “They’re going to encounter someone, even if it’s just to say good morning, or please, or thank you. ... Now they know a little bit more to show some gratitude.”

There’s plenty to learn from Nansemond: Show some gratitude, look for ways to make people feel welcome, and seek out kindness and celebrate it when you find it. Dave always did.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

As Israel votes (again), Arab union cracks and Jewish right unites

It would seem like a given that cooperation is key to political success. Yet alliances can be fragile. In Israel’s fifth election in four years, one successful partnership crumbles even as an anti-democratic union gains strength.

-

By Neri Zilber Contributor

Israeli elections Nov. 1 are in some respects a tale of two coalitions, one Jewish, one Arab. Among Israeli Arabs, who just two elections ago turned out in record numbers to vote for a unified ticket, the Joint List, disillusionment and disunity have set in.

Even though an Arab party, Ra’am, made history as a partner in the outgoing “change coalition,” many members of the long-neglected minority community say it wasn’t able to deliver on improved government services.

“People here didn’t see any change in their daily lives,” says Youssef Jabareen, a former parliamentarian. “If being in a coalition didn’t make any change, what hope is there to participate?”

Turnout this time may drop to historic lows, and the fractured pieces of the Joint List may not even clear the hurdle for representation in parliament. That could pave the way back to power for Benjamin Netanyahu, whose allies on the ultranationalist right are unified, growing in popularity, and threatening to dismantle core elements of Israel’s judicial system, and with that the checks and balances inherent to democracy.

One galvanizing figure is Itamar Ben-Gvir, a proud disciple of extremist ideologue Meir Kahane. Mr. Ben-Gvir, who in the past was convicted of incitement, more recently has touted a plan to deport citizens deemed “disloyal” to the state.

As Israel votes (again), Arab union cracks and Jewish right unites

The streets of this northern Arab city tell an important story about Israel’s national elections next week.

Garbage piles up. Many roads are in disrepair, and sidewalks simply disappear. Some homes sit half-built, and many that are finished have ad hoc connections to electricity.

All speak to an under-delivery of government services and a lack of building and planning permits granted by the national government.

And the city, like much of Arab Israeli society, is in the midst of a wave of violent crime and murders. Nearly 100 violent deaths have been recorded in Arab communities this year – 70% of the national tally, far exceeding their 21% share of Israel’s population. Residents fault several factors, not least the lack of proper policing and education budgets.

It was going to be different.

Former parliamentarian Youssef Jabareen points out that for Arab Israelis, many of these problems were supposed to be rectified under the broad outgoing “change coalition,” which included, for the first time, an Arab party in government, the Islamist Ra’am party.

And indeed, billions of dollars were allocated for Arab Israeli communities, although much of the money and promised reforms were stymied by right-wing government ministers, according to Arab officials and analysts.

“People here didn’t see any change in their daily lives,” Mr. Jabareen says, despite Ra’am’s groundbreaking role. “If being in a [governing] coalition didn’t make any change, what hope is there to participate?”

Ahead of the Nov. 1 national elections, Israel’s fifth round in less than four years, disillusionment and disunity have set in among Arab Israelis. While the long-neglected minority, whose members self-identify nationally with their Palestinian brethren in the West Bank and Gaza, has increasingly sought further integration into Israeli society and politics, voter turnout this time may drop to historic lows, say analysts and officials.

Such an eventuality could pave the way back to power for opposition leader Benjamin Netanyahu. Unlike the fractious Arab sector, Mr. Netanyahu’s allies on the far right are unified on one slate and growing in popularity – raising the former prime minister’s chances of winning an outright parliamentary majority.

These ultranationalist forces, encouraged and led by Mr. Netanyahu, are openly threatening to dismantle core elements of Israel’s judicial system, and with that the checks and balances inherent to Israeli democracy.

Yet among the minority group most vulnerable to the excesses of Jewish Israeli extremism, the danger of such a move seems not to resonate.

Crumbling coalition

Mr. Jabareen was holding court at the Umm al-Fahm headquarters of the Hadash-Ta’al party, which unites Arab nationalist and communist factions. The alliance is all that remains of the Joint List, wherein all four predominantly Arab Israeli parties (Hadash, Ta’al, Ra’am, and the more radical nationalist Balad) united and ran together. Arab voters responded two cycles ago with historic voter turnout, turning the Joint List into the third largest party in parliament and depriving Mr. Netanyahu of a majority.

Yet this election the Joint List’s dissolution, over issues of ideology and personal animosities, is nearly complete.

“People are so frustrated [with their political representatives] because in general we want one strong, united list representing all Arabs,” says Kamleh Eghbariyah, a local resident who intends to vote for Balad. “The split is definitely affecting the vote.”

Her distant relative and co-worker Halima Eghbariyah concurs, saying she plans to vote for the more moderate Hadash-Ta’al, and will encourage others to do so as well, counseling patience.

“If we won’t vote, we won’t have any representation in [parliament]. ... We won’t have any influence” on policy, she says. “The Arab representatives are in a hard position. I understand the obstacles to achieving everything we want – I just ask the Arab voters to put yourselves in their shoes. It can’t all happen immediately.”

According to the latest opinion polls, the three remaining factions are all hovering just below or above the 3.25% electoral threshold for entry into the Knesset. There is a real risk, Mr. Jabareen admits, that Arab Israelis may end up with no representatives at all in parliament after election day.

Polls consistently show that roughly 70% of community voters favor Arab parties joining a governing coalition, which Ra’am undertook last year.

Yet the other factions are still opposed, pointing to the major ideological concessions, as they see it, that Ra’am leader Mansour Abbas chose to make: recognizing Israel as a Jewish state, publicly denouncing Palestinian terror attacks, and remaining in government despite the recent Israeli-Palestinian violence in Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza.

“Abbas over the past year managed to break assumptions, dared to say things that no one ever said, and slaughtered all the sacred cows,” says Said Abu Shakra, an owner of a local gallery that brings together both Arab and Jewish artists. “But in order to be accepted he had to give up a lot of things,” not least opposition to the notion of Israel as a Jewish state, which effectively makes Arab Israelis “second-class citizens,” as he puts it.

Nevertheless, he intends to vote for Ra’am. “I want to be in a position to influence,” he says. “I want to be part of the solution, not part of the problem.”

Unity on the hard right

By contrast, the cohesion and unity on the ultranationalist Jewish right are striking. Three disparate far-right parties acceded to Mr. Netanyahu’s entreaties and came together last month to run on a joint slate, to maximize their strength.

In addition to the traditionally pro-settler Religious Zionism party, which leads the slate and provided its overall name, the alliance includes a fringe religious party, Noam, which campaigns against the LGBTQ community, and the Jewish Power faction led by Itamar Ben-Gvir, a proud disciple of the extremist, anti-democratic Jewish ideologue Meir Kahane.

The political movement founded by Mr. Kahane, who was assassinated in New York in 1990, was barred from politics in the late 1980s due to its anti-Arab invective. Mr. Ben-Gvir himself has been convicted for incitement, and as a lawyer has defended extremist settlers charged with violence against Palestinians.

More recently Mr. Ben-Gvir has touted plans to loosen Israeli military rules governing live fire directed at Palestinians, as well as a plan to deport citizens deemed “disloyal” to the state.

Earlier this month, amid clashes between Palestinians and Israelis in East Jerusalem, Mr. Ben-Gvir showed up and openly brandished a gun, declaring, “We’re the landlords here. Remember that, I am your landlord.”

On the back of his growing popularity, Religious Zionism as a whole has surged in the polls and may end up as the third biggest party in parliament – aided in large part by Mr. Netanyahu, who has said Mr. Ben-Gvir will be a minister in his next government, as well as by a largely uncritical local media.

Even more moderate voters on the right seem attracted by Religious Zionism’s vows to support Mr. Netanyahu’s bid to quash the independence of the Israeli judiciary, including the power of the Supreme Court and attorney general to block government decisions deemed illegal or unconstitutional.

Such “reforms,” as right-wing politicians term them, would also likely halt Mr. Netanyahu’s ongoing trial on a slew of corruption charges.

Mr. Ben-Gvir’s fundamental appeal, however, appears to be his promise to strengthen the “personal security” of Jewish Israelis against the threat of Arab violence – especially after widespread intercommunal riots in mixed Jewish-Arab cities in May 2021, during a round of fighting in Gaza.

“It’s the lesson from that Gaza operation, the Arabs in the mixed cities haven’t been dealt with at all,” says Tamir Dortal, a high school teacher and podcast host in Jerusalem who is set to vote for Religious Zionism. “The center-right parties never deliver on their promises, so you have to go more extreme.”

Mr. Dortal says he believes Mr. Ben-Gvir will moderate somewhat once in government, and that even he will “betray” some of his electoral vows – “but he’ll do so the least.”

“I judge every party according to its policies and what they push for in practice, not what they say or what’s in their hearts,” he adds.

Yet for many Arab Israelis, what Mr. Ben-Gvir believes and what he does once he gains power seems immaterial, and is not likely to change their plans to vote.

“I’m not afraid of Ben-Gvir,” says Mr. Abu Shakra, the gallery owner. “[Liberal] Jews are more afraid of him because he’ll steal the country from them. Our situation [as Arab Israelis] can’t be worse. We’re ready for any eventuality, and we expect very bad news.”

A deeper look

Geothermal 2.0: Why Cornell University put a 2-mile hole in the Earth

To solve humanity’s reliance on fossil fuels, solar and wind power isn’t enough. Some researchers and investors are looking down, not up. Our reporter finds ingenuity powering new efforts to produce heat and electricity by tapping the Earth’s core.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 15 Min. )

Most of the discussion about how to stay warm without burning fossil fuels has focused on electrification – exchanging your oil tank, for instance, for an electric heat pump. But this approach doesn’t solve a big problem: where that electricity comes from. Despite a huge increase in wind and solar power production, most electricity still comes from power plants that burn fossil fuels.

Nuclear, solar, and wind all partly offer solutions to this.

But below a nondescript former parking lot in Ithaca, New York, scientists at Cornell University are trying something else: drilling a hole 2 miles into the Earth.

Geothermal energy is not new. In Iceland, where hot rock and subterranean water are near the surface, 9 out of 10 households get their heat directly from geothermal sources. But the current moment of climate concerns, energy prices, and new financial incentives has sparked a new sort of Earth rush, even in places where the geography for geothermal energy is less obvious.

Some of the new players entering the field are those deeply familiar with drilling: oil and gas majors.

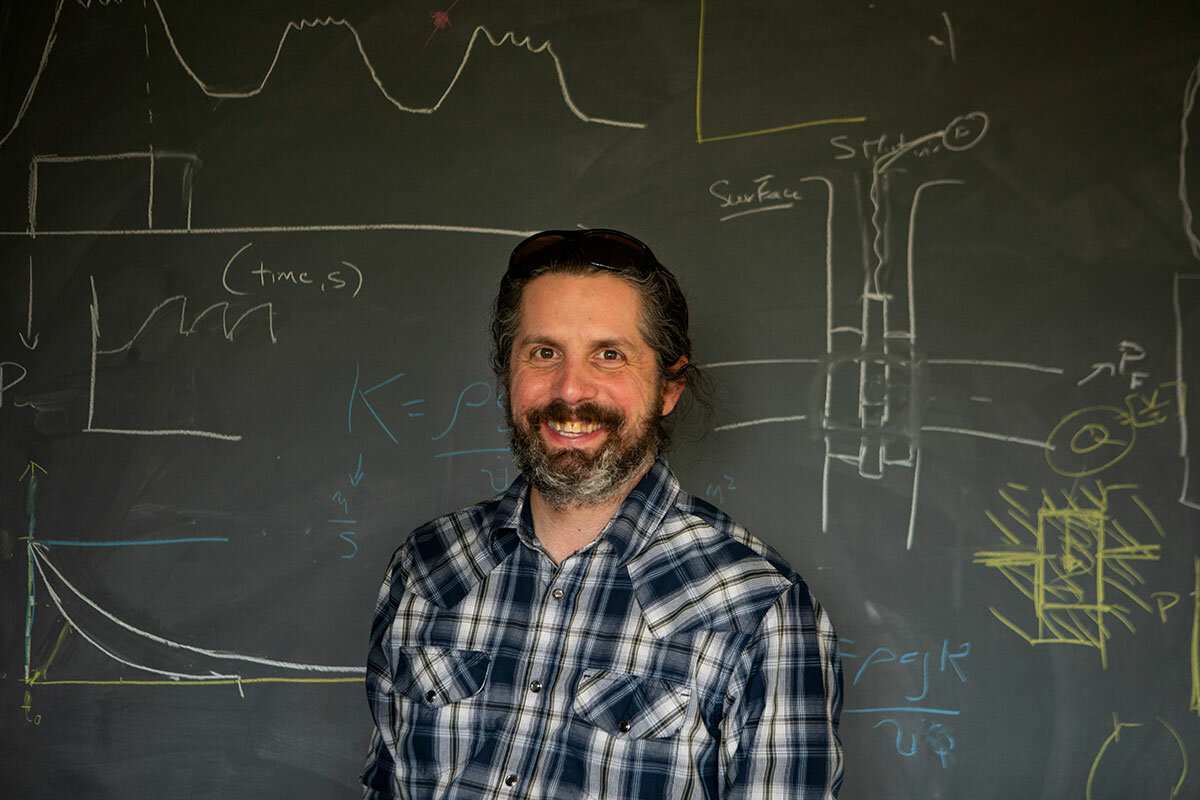

“It’s changing the mindset,” says Patrick Fulton, one of the lead geothermal researchers at Cornell. “It is starting to think more sustainably about how we interact with the Earth.”

Geothermal 2.0: Why Cornell University put a 2-mile hole in the Earth

The Cornell University campus in Ithaca, New York, is a small city of some 30,000 people, spanning 2,400 acres and hundreds of buildings, including castlelike dorms and state-of-the-art laboratories, an art museum shaped like a sewing machine, and a power plant that produces some 240 megawatts of electricity every year.

This leafy, academic metropolis is perched on layers of sedimentary rock – geology that reveals itself in the gorges that slice through the campus, deep crevices where, long ago, errant waters of retreating glaciers ripped open the earth.

These layers continue deep underground, thousands upon thousands of feet, until they hit what is known as the “crystalline basement.” There, nearly 2 miles down, lies a rock barrier between what we, as humans, typically think of as “earth” on one side, and the planet’s hot, silicate mantle on the other. It also marks the location of what a growing cadre of scientists, entrepreneurs, and government officials sees as a viable solution to a pressing, yet elemental, challenge: how to stay warm.

On the one hand, this might seem like a mundane problem for the intellectual and technical ingenuity of one of the world’s top research universities. Humanoid ancestors, after all, solved this problem of winter centuries ago with their fires and blankets and animal skins. Today, central heating systems have made staying warm almost an afterthought, even in those Northern Hemisphere locations that freeze for months on end.

But there is a looming problem: How we heat mostly relies on burning fossil fuels. This is a problem because of what it means for the world’s climate, which is changing rapidly thanks to atmosphere-warming emissions. But it is also a problem because it is becoming clear that staying warm through winter is tied to global forces often beyond one’s control, such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has resulted in both gas shortages and cost spikes.

This situation, a growing number of researchers say, is requiring a new sort of ingenuity. Until very recently, most of the discussion about moving away from fossil fuel-based heating has focused on electrification – exchanging your oil tank, for instance, for an electric heat pump. But this approach, although effective at lowering greenhouse gases, doesn’t address two big problems: First, the world’s electric grids are already straining to keep up with demand. And second, despite a huge increase in wind and solar power production, most electricity still comes from power plants that burn fossil fuels.

Policymakers have suggested a slew of different models for addressing this quandary, such as extending the life of nuclear power plants, ramping up the number of wind and solar farms, or tapping into the awesome power of ocean waves to produce electricity.

Monitor Backstory: A shift on a power source?

Sides have long been staked out on nuclear power: It’s either a poisonous menace or a means of getting past dirty, extractive energy production. The Monitor’s Stephanie Hanes, who covers climate change and the environment, explores a rising middle ground. Hosted by Samatha Laine Perfas.

But here in Ithaca, and in a rapidly growing number of locations worldwide, scientists, utilities, and entrepreneurs are flipping the solutions narrative. Instead of looking upward for clean energy, to the sun or the wind, they are turning their ingenuity downward, into the Earth itself. And while the basic concept of geothermal energy has existed for decades – if not centuries, depending on how one looks at it – the current moment of climate concerns, energy prices, and new financial incentives has sparked a new sort of Earth rush.

“We’re seeing a huge influx into the geothermal sector,” says Jeremy Harrell, chief strategy officer at ClearPath, a research and advocacy group that focuses on using free-market policies to accelerate emissions reductions. “Geothermal is exciting. It’s a cost-effective technology that is resilient and that can provide heat and power.”

It could also, if some of the more cutting-edge initiatives succeed, fundamentally alter the way the world understands and uses energy.

In the middle of a nondescript gravel lot, once reserved for contractor parking, high above Cayuga Lake, researchers involved with Cornell’s Earth Source Heat project have drilled down nearly 2 miles, to that crystalline basement, to explore the potential of tapping geothermal heat. Only the wellhead remains – the drill rig and the mud spinners and cement silos departed this fall – but scientists here are still studying the geology of what they affectionately call CUBO, the Cornell University Borehole Observatory. They are modeling water flow, examining seismic behavior, and working with facilities staff to plan a new system for heating the campus.

“If we want to decarbonize, we have to switch from natural gas to something else,” says Jefferson Tester, a professor of sustainable energy systems in Cornell’s Smith School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering and the principal scientist for the university’s Earth Source Heat project. “Geothermal would be one of the really good opportunities. ... It’s on all the time, it’s available, it’s stored in the earth. And we can reach it with today’s technology. We’re trying to give an example of what you could do, and what we might have to do.”

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY

Tapping the earth for heat and power, by itself, is not new. In Iceland, where hot rock and subterranean water are near the surface, 9 out of 10 households get their heat directly from geothermal sources. In Boise, Idaho, a centralized geothermal system delivers 177-degree water through a series of pipes that heats millions of square feet of downtown building space. There is also geothermal heating in Paris; San Bernardino, California; and Klamath Falls, Oregon – places where subterranean hot water reservoirs can flow through rock at relatively shallow depths.

These places also tend to have geothermal power plants – facilities that use the Earth’s heat to make steam to spin turbines that generate electricity in the same manner as nuclear or coal plants. The Geysers, for instance, a 45-square mile facility located about 75 miles north of San Francisco, is home to the largest geothermal energy site in the world. This spot, which archaeological research shows was a human gathering place for centuries, has some 300 production wells and 69 miles of injection piping feeding steam into turbines that in turn supply a good percentage of California’s renewable energy – about 8% in 2021. This power, points out Joseph Greco, the head of the Western region strategic initiatives for Calpine, the company that runs the Geysers, is consistent – it doesn’t fluctuate like wind or solar. This is particularly important for a grid that is increasingly maxed out. During the state’s rolling blackouts this past summer, “we were there supplying the grid 24/7,” he says.

But the idea of expanding geothermal anywhere and everywhere, so that the earth beneath one’s feet can take care of a good percentage of one’s own heat and power needs – that’s new. And it has caught the imagination not just of scientists, but of the U.S. Department of Energy, along with a growing number of startups and existing power companies.

“There are not a lot of places in the world that you just have steam billowing out of the ground,” says Paul Thomsen, vice president of business development at Ormat Technologies, a Reno, Nevada-based geothermal company that is rapidly expanding operations. “So you have to start drilling and looking for hidden geothermal resources. And with innovation, the concept is that we don’t have to have Old Faithful to develop geothermal.”

There are different systems for creating this “next-generation” geothermal. There are “closed-loop” systems that, rather than tapping into hot underground water reservoirs, send a pipe through the hot areas, sort of like a big, old-fashioned radiator through the Earth.

In areas without deep water reservoirs – a geology that those involved with geothermal will sometimes call “hot dry rock” – there are also efforts to “frack” deep rock, making fissures through which water can be injected. (Those involved with geothermal insist this is fundamentally different from much-protested natural gas fracking, since they are using only water to break up and run through the Earth, not sand and chemicals.)

Ormat Technologies uses a geothermal system where hot underground brine – water that is filled with salt and other sorts of minerals – heats a secondary liquid, which in turn goes through a heat exchange process to spin power-generating turbines. The company now has an energy portfolio that includes facilities across the world, from the U.S. to Kenya to Indonesia.

But starting a geothermal project takes time. Those involved with geothermal say that the permitting process is cumbersome, often requiring a yearslong feasibility and safety ramp-up. It is location specific, since the type of well and how deep it goes into the Earth change a lot with the geologic composition of any particular place. (This is unlike, say, solar panels, which can be mass produced and installed in almost any location.) And it is not easy to drill deep into the Earth.

But there is an existing industry with a lot of experience in geology and drilling. And with growing political, financial, and climate pressures, it has an interest in diversifying its operations. This, of course, is the oil and gas sector.

Many executives in that industry are now looking at alternatives, says Maria Richards, the Geothermal Lab coordinator at Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

“With the start of COVID [when demand dropped] ... it has seemed to create a push for [the] oil and gas industry to pause and say, we need to look outside the box,” she says. “There will be a time in the future when people do not need or want all this oil and gas.”

She and many others involved with geothermal caution that there are important nuances that differentiate oil and gas drilling from mining Earth heat. But there’s no disputing that there are key similarities. There are a growing number of private sector geothermal initiatives staffed by former fossil fuel workers, and sometimes backed by oil and gas companies themselves. And to go with this, there is growing venture capital investment.

This summer, a company named Fervo Energy raised $138 million for next-generation geothermal energy, the largest private investment in geothermal technology to date. Much of Fervo’s leadership comes from the gas and oil sector. The Alberta No. 1 geothermal project in Canada explicitly advertises its background in drilling and gas exploration – its name is a nod to Leduc No. 1, the site of Alberta’s major oil discovery in 1947.

Catherine Hickson, the CEO of the Alberta No. 1 geothermal energy project, knows that there has been excitement about geothermal in the past. She has worked for more than 40 years in the sector, primarily as a scientist for the Canadian government, and she watched as government and private investor attention turned toward geothermal during global oil crises and then shifted back to fossil fuels. Even today, she says, it’s hard for geothermal to compete financially against the gas and oil sector – if one is going to dig a very deep and expensive hole, there’s still a lot more money to be made bringing up fossil fuels as opposed to hot water.

But all of that is shifting with climate change, she says, and as companies worry about the sustainability of their business models in the face of what is turning into a global consensus on the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions significantly and quickly.

“We want to make sure people understand that our form of renewable energy has a very significant environmental credit to it,” she says. “We think it’s very important from the perspective of greenhouse gas reduction. And financially, carbon credits and ESG [environmental, social, and governance] have dramatically changed the landscape for geothermal.”

Others are working on technology to further reduce the cost of geothermal. Paul Woskov, for instance, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), has turned his expertise in nuclear fusion technology toward making a new sort of drill that uses gyrotron beams to vaporize rock. If he and the company attempting to commercialize his work are successful, they hope to dramatically lower drilling costs – and allow for geothermal to happen everywhere.

“Our principle is that we’ll be able to replace every fossil fuel plant with a geothermal plant,” he says.

To encourage this sort of innovation, the U.S. Department of Energy this year added an enhanced geothermal “shot” to its Energy Earthshots program, a series of initiatives and funding streams intended to spark innovation to help address the climate crisis and grow the clean energy job sector. The department made a specific request for projects that used geothermal for direct heat.

“Everybody is talking about electrification, but I don’t think electricity is the answer,” says Dr. Hickson at Alberta No. 1. “We need to get the world to understand – especially in the U.S. and Canada – the low-hanging fruit here is thermal energy.”

This has been Dr. Tester’s mission for decades.

The Cornell professor began working in geothermal energy as a postdoctoral student in Los Alamos, New Mexico, under the Carter administration, when scientists at the national laboratory began what became known as the Hot Dry Rock Program.

Their goal was not dissimilar to that of today’s geothermal entrepreneurs, although futuristic at the time. “The natural heat in hot dry rock at accessible drilling depths is one of the largest supplies of usable energy that is available to man,” wrote Los Alamos scientist Morton Smith in a 1995 report about the program. “It is potentially capable of satisfying the world’s total energy needs for thousands of years.”

But the funding for that program evaporated during the Reagan administration, and Dr. Tester went to work at MIT, where he continued his research on geothermal energy and heat. In 2009, Cornell asked him to join its faculty and head a project to put that work into practice.

In many ways, Cornell’s Ithaca campus was the perfect location to create an earth source heat system. It was already committed to carbon neutrality. And from a practical point of view, a university, where administrators have access to and control over all the buildings, is a good place to make this sort of systemwide change.

Cornell had already made huge investments in both practical science and infrastructure related to utilities, and it had a suite of alternative energy systems: a central heat and electricity power plant that was converted from burning coal to cleaner natural gas and now tracks and adjusts its operations to keep emissions as low as possible; a generations-old hydropower plant perched alongside the picturesque Fall Creek; and, most unusually, an innovative “lake source cooling” system, which taps the cold, deep water of Cayuga Lake to cool buildings without traditional air-conditioning systems. That lake source cooling, in fact, was the same system that Dr. Tester imagined for heat, just in reverse – a water-based, centralized pipe system that operates with minimal electricity and, thanks to connected solar panels and the hydroelectric plant, almost no carbon. Meanwhile, administrators were aware that heating accounted for more than a third of the school’s total greenhouse gas emissions.

The school was also willing to experiment. It is part of the university’s mission, administrators say, to use academic resources

to develop environmental solutions that can be applied well beyond campus. “The way we can move the needle is finding new solutions,” says Sarah Carson, director of Cornell’s campus sustainability office. “And what’s really special about our geology is that there is nothing special about our geology.”

In 2009, Dr. Tester and his team of graduate students began putting together a plan for the new Earth Source Heat system.

But in many ways, what was under their feet was still a mystery.

“We can make guesses about what rocks are there,” says Patrick Fulton, an earth and atmospheric sciences professor at Cornell and one of the lead Earth Source Heat researchers with Dr. Tester. “There are seismic and geophysical surveys that can help us predict it. But to know what it actually is – for that we have to go down.”

In a windowless laboratory on the first floor of the Cornell University earth sciences building, dozens of blue boxes sit on top of each other, all filled with samples of earth taken from CUBO. Graduate student Sean Fulcher removes one baggie and dumps the contents onto a table. The gravel shards are part of the crystalline basement, which Mr. Fulcher and Dr. Fulton estimate to be 1.1 billion to 1.5 billion years old. The rocks were likely part of the base of a mountain range that once reached higher than the Himalayas.

They extracted these samples from the borehole. The scientists are now exploring each of them, cleaning them, painstakingly recording their features, and building a 3D image of the inside of the Earth. These rocks, and others, give a sort of map of what may be underneath the university – where there are cracks, where geologic layers have pushed into one another, where tectonic movement from 100 million years ago may have left the sort of subterranean features that today could lead to a modern-day heating system.

Some of this research is also essential for safety. “You don’t want to mess around and create earthquakes,” Dr. Fulton says.

This has happened with some geothermal initiatives in the past. In 2009, for instance, the Swiss government abandoned plans for geothermal power after the project generated unexpected seismic activity that damaged homes in the city of Basel.

Closer to Cornell, in Onondaga land south of Syracuse, the Tully Valley mud boils are the continued, polluting legacy of an 1800s attempt to mine salt by injecting water into the ground. The earth fractures created by that process still, more than a century later, allow brine laden with silt and minerals to boil toward the surface, muddying what was once the fishing grounds of the Onondaga people.

This worries some environmentalists, who wonder about the line between ingenuity and hubris – especially with a growing number of private sector interests involved. But geothermal researchers say the alternative of continued fossil fuel emissions is even riskier, and they insist that there is far more attention today to the possible seismic and environmental impacts of drilling.

“There are definitely things that, if you don’t do it well or smart, and you don’t have an understanding of what could go wrong, then could be bad,” says Dr. Fulton.

That’s why an academic effort like Cornell’s is so important, he and others involved say. They are not only demonstrating the viability of a new energy system, but also showing how to foster ingenuity safely. They are working to fully understand the rocks before continuing with the next phase of the project, which would involve drilling more wells and connecting the geothermal system into the campus’s existing heating system. Those involved say the project could still take years to complete, depending on financing.

But for Dr. Fulton, the purpose of CUBO goes beyond simply heating the campus with carbon-free thermal energy. Knowing what is underground helps scientists imagine a relationship with the Earth that is not simply extractive, he says. If humans, for instance, are taking heat from those deep rocks, could we return that energy? Could the Cornell greenhouses, which currently blow heat into the atmosphere, instead send that heat underground, using the Earth as a sort of rechargeable heat battery?

“It’s changing the mindset,” he says. “It is starting to think more sustainably about how we interact with the Earth.”

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY

Film

‘All Quiet on the Western Front’: A German retelling for a modern time

German filmmaker Edward Berger’s version of “All Quiet on the Western Front” is an effort to help his native country continue its discourse about war and responsibility.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The arrival today of “All Quiet on the Western Front” on Netflix marks the third film version of the 1929 war novel, but the first helmed by a German director, Edward Berger.

He says it was time for a homegrown telling of the head-hanging felt by generations of Germans, following their country’s imperialistic aggressions in World War I and II.

“If your [American] great-grandfather fought in the war, he came back and was celebrated and embraced,” he says. “It’s just a different legacy in Germany. It’s only shame and guilt – that informs every creative decision I make.”

A land war is again raging in Europe, this time via the aggressions of Russian President Vladimir Putin. The film’s depictions of war in all its brutal detail are resonating in Germany, as is its reminder of the dangers of nationalism gone overboard. Yet some early reaction in the country, where the film has been in limited theaters, also reflects the ongoing conflict presented by a long-entrenched German pacifism.

“The German position is a very difficult one,” admits Mr. Berger. “Having succumbed to our destructive impulses twice in the last century gives us a special weight on our shoulders. Our politics, our guiding light is very much ‘How can we solve this?’”

‘All Quiet on the Western Front’: A German retelling for a modern time

War was sold to a young Paul Bäumer as a romantic ideal.

Spurred by a patriotic teacher, he volunteers to join his fellow classmates – mere boys – on the front lines of a war that quickly manifests as anything but aspirational. The protagonist of “All Quiet on the Western Front” battles hunger, grieves lost classmates, and charges the World War I battlefield with little apparent training, all while wearing a uniform his German chain of command had recycled off a dead soldier’s body.

It’s Netflix’s version of the global bestselling 1929 war novel – “Im Westen nichts Neues” – that the Nazis famously considered a threat. Before the Nazis seized power, their master propagandist Joseph Goebbels even orchestrated a riot at the 1930 Berlin premiere of the Hollywood film version.

The 2022 release is the third film based on the novel, but the first helmed by a German director. And, says the filmmaker, Edward Berger, it was time for a homegrown telling of the unique head-hanging felt by generations of fellow Germans, following their country’s imperialistic aggressions in both world wars.

“If your [American] great-grandfather fought in the war, he came back and was celebrated and embraced,” says Mr. Berger. “It’s just a different legacy in Germany. It’s only shame and guilt – that informs every creative decision I make.”

A land war is again raging in Europe, this time via the aggressions of Russian President Vladimir Putin. The film’s depictions of war in all its brutal detail are resonating in Germany – where it’s been out in select theaters a month ahead of this week’s global Netflix release – as is its reminder of the dangers of nationalism gone overboard. Yet some early reaction in the country also reflects the ongoing conflict presented by a long-entrenched German pacifism.

“World War I remains the original catastrophe of the 20th century, really,” says Stephen Brockmann, author of “A Critical History of German Film” and a professor of German at Carnegie-Mellon University. “The Germans for a long time have been fairly pacifist, yet what’s interesting is that most people seem reasonably comfortable with the government’s pretty strong stand against Russia right now. What the [novel and film] don’t answer is the question of ‘What do you do if you have an aggressive fascist opponent who tries to invade you?’ Are you supposed to be passive?”

Interpreting the novel

When Erich Maria Remarque’s novel was released in 1929, it was an immediate global bestseller, moving nearly 3 million copies in short order. Some 17 million people had died in World War I, and the world was still grappling with disillusionment. Mr. Remarque, who had been drafted into the German army, wrote of the banalities of war in stark terms, sparing no detail as soldiers relieved themselves on makeshift toilets, stole farmers’ geese for food, and visited brothels. In other words, there was no heroism in the narrative.

While Mr. Remarque called his work “neither an accusation nor a confession,” it’s clear why audiences interpreted the novel as anti-war: The characters’ deaths are brutal and senseless, and young people alternately battle death, boredom, and hunger along a trench that seems to shift mere meters over the course of years. The remove and relative luxury that bathes top brass is also clear, as they sip tea and travel on train cars, while exhausted soldiers carry out their orders without larger context.

The title “All Quiet on the Western Front” is mired in irony, as it’s the single line messaged home from the trenches on the day the protagonist dies.

When a U.S.-produced film version premiered in Berlin in December 1930, the Germans had spent a decade trying to work their way back onto the global diplomatic stage, and the sting was still fresh from its postwar territorial losses. It was lost on no one that 3 million Germans were now living in Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Poland.

“The German right wing wanted to see something much more heroic and much more nationalistic, and they were very critical of Remarque and the film,” says Dr. Brockmann. The Nazi paramilitary wing’s attempt to sabotage the 1930 film premiere only added to the aura of the party at a critical political moment.

What ensued was a major cultural event, says Edward Smith, associate professor of German literature at Rowan University in Glassboro, New Jersey. “Everyone had to have an opinion, and people took a stand either for or against the 1930 film and the novel upon which it was based.”

Germany’s place in history

It’s unclear whether Mr. Berger’s 2022 work will have the same cultural reach today in a fragmented media landscape (or with today’s fragmented attention spans), though it is Germany’s submission for best international feature film at the Academy Awards.

Over the years, reception to the works have changed as Germans grappled with their place in world history, reluctantly at first and then with greater resolve. (The Nazis burned the book in 1933, and in modern times it has been required school reading.) Still, while often dismissive of the necessity for war, Germans have also criticized Chancellor Olaf Scholz for sending helmets and a field hospital to Ukraine while other NATO allies were sending tanks and heavy weapons.

“Germany has been tortured by the aftereffects of war, but Germany is the largest economy in the European Union, and it needs to find its path as a strong leader,” says Dr. Smith, the German literature professor. “However Scholz and other politicians also see the danger in Germany being perceived as too strong a leader.”

For most Germans today, the Ukraine war is a clear war of good against evil, yet public opinion is divided on whether Germany is doing too much, too little, or just enough to assist Ukraine. About 45% of Germans feel their country should do more, according to a poll this week by German broadcaster ARD.

Yet, when compared across the EU, Germans are second only to Italians in wanting a quick end to the war, even if it requires Ukrainian concessions. In other words, Germans are among the loudest voices in the “peace camp,” while the “justice camp” believes only a Russian defeat can bring peace, according to a European Council on Foreign Relations report.

This is an interplay that betrays German pacifist tendencies. “The German position is a very difficult one,” admits Mr. Berger. “Having succumbed to our destructive impulses twice in the last century gives us a special weight on our shoulders. Our politics, our guiding light is very much ‘How can we solve this?’ By diplomacy, by sitting down together, by creating bridges, by being part of the EU. By championing the EU. I think that would be our responsibility in history, rather than anything that is confrontational.

“But we can’t just stand by and do nothing about Ukraine. We have to try to support them, to try to find a solution,” says Mr. Berger, while remarking he’ll leave solution-finding to “smarter minds.”

“He understands where he’s from”

At September’s premiere of the film in Berlin, just ahead of the German nationwide release, bedecked moviegoers mingled as a three-piece band played before a neon red Netflix sign. It was a far cry from the Nazi-agitations at the 1930 Berlin premiere, though attendees were also talking about everything having to do with war.

“For my grandmother, war was always very traumatizing,” says Heinrike Heinoch, an opera singer living in Berlin. “War was always repeating and repeating, and she would look at the television and say, ‘Oh, somewhere in the world there is war,’ and she was always very emotional.”

Anna, a Berlin gallerist, who shared only her first name for privacy reasons, remarked that it was important to consider the soldier’s perspective. “You have to dive into these feelings and the thoughts people had, and the destruction that happened to the souls.”

If it were up to Mr. Berger, such considerations of the cost of war will never leave the German discourse. He recalls a family trip that included a detour to the Mauthausen concentration camp, now a museum. It was the first time his son, who was 12, toured it.

“I saw the moment it goes into his body, that responsibility, that he understands where he’s from. It’s part of our DNA,” says Mr. Berger. “He’s growing up with it, and I hope his kids will grow up with it, too. So that we don’t forget.”

“All Quiet on the Western Front,” is streaming on Netflix and available in some theaters. It is in German and some French with English subtitles, and is rated R for strong bloody war violence and grisly images.

Commentary

In ‘Till,’ the power of a mother’s love

Love sometimes comes in the form of openness – even when that means revealing a brutal truth. Our commentator found that depth of love in the movie “Till.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

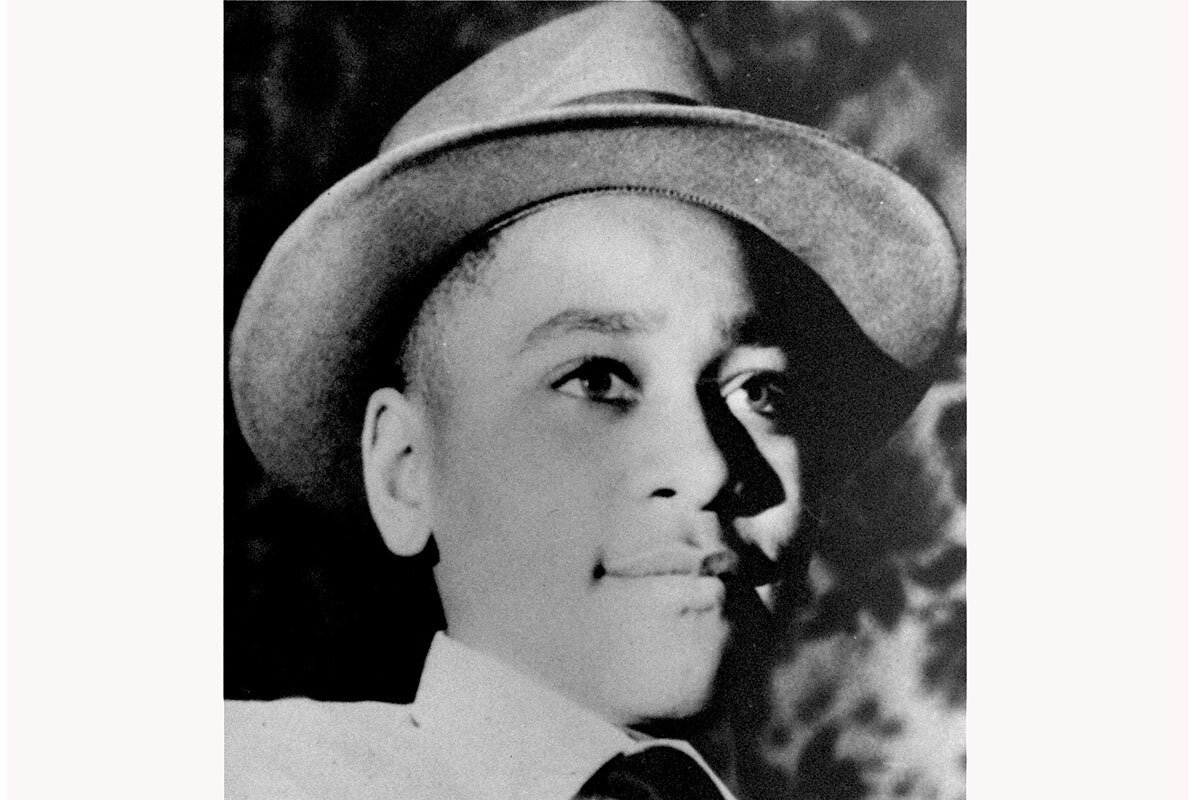

A single word captures the essence of “adding insult to injury” – indignity. Humiliation, hatred, hurt – these three words are part of the indignity that encapsulates the brutal murder of Emmett Till. The legacy of Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, was her commitment to cut through that indignity, even if she had to employ the ugly truth and tragedy as a weapon.

I was reluctant to engage “Till” at first. I branded such movies as the “trauma industrial complex” – a painful rehashing of Black trauma. But comments by the director about Mamie’s journey after her son’s death, anchored in love, changed my mind.

“Till” does a masterful job in its display of indignity, from its depiction of the Jim Crow South to the deliberate injustices of law enforcement, even the respectability politics present among Black people. Actor Danielle Deadwyler’s Mamie is at her best when her character deals with a harsh reality – America needed to see the brutality of racism, leading to her decision to have an open casket at his funeral.

Solace is found in the community. “Till” juxtaposes the horrors of racism with the shared sense of family and fears that kindred spirits face. The point of “Till,” of course, is not harm. As the director reminds us, it is history and honor.

In ‘Till,’ the power of a mother’s love

A single word captures the essence of “adding insult to injury” – indignity. Humiliation, hatred, hurt – these three words are part of the indignity that encapsulates the brutal murder of Emmett Till. The legacy of Emmett’s mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, was her commitment to cut through that indignity, even if she had to employ the ugly truth and tragedy as a weapon.

I was reluctant to engage “Till” at first. I branded the movie and presentations of its ilk as the “trauma industrial complex” – a painful and perhaps needless rehashing of Black trauma. A statement from “Till” director Chinonye Chukwu changed my mind:

The crux of this story is not about the traumatic, physical violence inflicted upon Emmett – which is why I refused to depict such brutality in the film – but it is about Mamie’s remarkable journey in the aftermath. She is grounded by the love for her child, for at its core, TILL is a love story. Amidst the inherent pain and heartbreak, it was critical for me to ground their affection throughout the film. The cinematic language and tone of TILL was deeply rooted in the balance between loss in the absence of love; the inconsolable grief in the absence of joy; and the embrace of Black life alongside the heart wrenching loss of a child.

“Till” does a masterful job in its display of indignity, from its depiction of the Jim Crow South to the deliberate injustices of law enforcement, even the respectability politics present among Black people. Danielle Deadwyler’s Mamie is at her best when she dealt with a harsh reality – America needed to see the literal brutality of racism, leading to her decision to have an open casket at his funeral.

It is difficult to review a movie like “Till” without reviewing society altogether. Jalyn Hall, the young man who plays Emmett, could have just as easily starred in a movie about Tamir Rice, the Ohio 12-year-old who was killed by police. I learned about Emmett as a preteen, and though he might have been a peer of mine, I would not have been able to grasp the fullness of such a tragedy.

And I wasn’t yet a father when Tamir was killed, but I agonized over the senselessness of his death and those like it.

I write this now as a father of two sons, and Emmett’s murder adds a more intimate burden, more gravitas, comparable to the pain I feel as a Black man. This quote from former President Barack Obama echoes solemnly: “If I had a son, he’d look like Trayvon.”

This is where the indignity is thickest. For too long, Black people in America have engaged in a system that can kill your children and make a mockery of you, your family, and your people.

That angst can turn an innocent backdrop into a cruel ballad of perseverance. “Just smile,” reads a toothpaste ad as the camera pans away in a transition from precarious Chicago to the perilous Mississippi Delta. Grin and bear it.

The only solace is found in the community. “Till” juxtaposes the horrors of racism with the shared sense of family and fears that kindred spirits face. There are the Chicagoans who rally around Mamie when they hear of Emmett’s kidnapping. There are the Black advocacy and activist organizations across the country that do their best in the face of adversity.

The point of “Till,” of course, is not harm. It is history and honor, as Ms. Chukwu reminds us:

Mamie’s untold story is one of resilience and courage in the face of adversity and unspeakable devastation. For me, the opportunity to focus the film on Mamie, a multi-faceted Black woman, and peel back the layers on this particular chapter in her life, was a tall order I accepted with deep respect and responsibility. On the daily, Mamie combatted racism, sexism, and misogyny, which was exponentially heightened in the wake of Emmett’s murder. Mamie did not cower. Instead, she evolved into a warrior for justice who helped me to understand and shape my own similar journey in activism. And as a filmmaker, showing Mamie in all her complex humanity was of utmost importance.

People familiar with the Till tragedy might also be interested in the story of Medgar Evers. The Till case was one of the slain civil rights activist’s first assignments, and the movie provides introspection between two mothers of the movement: Mamie and widow Myrlie Evers.

Till – what a heavy surname. The word, by definition, speaks to farm labor, working tirelessly in pursuit of harvest. It speaks perfectly to Black people’s quest for justice and equity. The word “till” is also a statement of time – a period of longing, or as the end of the first verse of the Black national anthem declares: Let us march on ’til victory is won.

“Till” is rated PG-13 for thematic content involving racism, strong disturbing images, and racial slurs.

Listen

Where ‘the draft’ serves the nation, and the draftee too

Many countries require some form of national service. Our writer found signs of a new, balanced approach in Northern Europe, where war is at the doorstep but social responsibility seems still at the fore. From our weekly podcast.

What do you think of when you hear “conscription” or “the draft”?

For many, those terms suggest something onerous: an individual’s forced service, a country’s last resort. The Monitor’s Lenora Chu found something different in reporting from Baltic and Nordic states for a story she filed from Riga, Latvia.

With war right on the doorstep, here were signs of public support – so far – for new versions of compulsory service, something that countries around the world have tried.

“This is not your grandfather’s draft,” Lenora tells Samantha Laine Perfas. A major focus by governments is the development of individuals’ skills. There’s no set formula. Countries are still considering how and whether women should be included, and what lengths of service make sense. It hasn’t gone without challenges; for example, Norway has dealt with reports of sexual harassment and difficulties changing military culture.

But broadly, there has been receptivity for a practice sometimes known colloquially as “going into the forest.”

“One day I did spend walking around a park and I met some young people. ... They basically said, ‘Look, this is an opportunity for personal growth,’” Lenora says. “They talked about the money, about getting fit, about being able to protect their family.” – Samantha Laine Perfas/Senior multimedia reporter

Prefer to read this audio interview? You can find a full transcript here.

Rebooting Conscription

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

India eyes a model of civic equality

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For nearly a decade, India has been ruled by a political party rooted in Hindu nationalism. Many of its actions, critics lament, threaten a constitutional principle of secular rule by marginalizing people of other faiths, especially Muslims. Yet that sort of identity politics took a subtle hit this week from, of all places, Britain.

Rishi Sunak, whose family heritage lies in India, was chosen as Britain’s prime minister by the Conservative Party. Almost immediately, his entry into No. 10 Downing St. jolted debates among Indians around the world about their country’s treatment of minorities.

The debate in India reflects the breadth and subtlety of Mr. Sunak’s biography. As the grandson of immigrants, he says he is more British than Indian. “I am thoroughly British, this is my home and my country, but my religious and cultural heritage is Indian, my wife is Indian. I am open about being a Hindu,” he said.

For now, Britain has crossed an important threshold. For India, meanwhile, a debate has been renewed over treating all citizens as equal, even able to become a prime minister.

India eyes a model of civic equality

For nearly a decade, India has been ruled by a political party rooted in Hindu nationalism. Many of its actions, critics lament, threaten a constitutional principle of secular rule by marginalizing people of other faiths, especially Muslims. Yet that sort of identity politics took a subtle hit this week from, of all places, Britain.

Rishi Sunak, whose family heritage lies in India, was chosen as Britain’s prime minister by the Conservative Party. Almost immediately, his entry into No. 10 Downing St. jolted debates among Indians around the world about their country’s treatment of minorities. Some, including prominent members of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, celebrated Mr. Sunak’s rise as a justification for their brand of politics. Others saw it as a moral prompt.

“Indians in India have greeted the news of Sunak’s elevation with a feeling of awe and pride,” wrote Siddharth Varadarajan, former editor of The Hindu, India’s national English-language newspaper. “But instead of feeling happy for themselves,” he wrote, Indians should be asking what has happened “to the religious diversity and cultural pluralism that has been part and parcel of Indian life for thousands of years.”

The debate in India reflects the breadth and subtlety of Mr. Sunak’s biography. As the grandson of immigrants, he says he is more British than Indian. “I am thoroughly British, this is my home and my country, but my religious and cultural heritage is Indian, my wife is Indian. I am open about being a Hindu,” he told Business Standard in 2015.

Mr. Sunak’s combined identity marks a sharp distinction from the assertive ethnic nationalism of rulers in China, Russia, and India, as well as the nativism of a few political movements in Europe and the United States. In the same interview, Mr. Sunak drew an observation from his time as a graduate student at Stanford Graduate School of Business in California. Religion pervades political life in America, he noted, “and that is not the case here, thankfully.”

He enters office not just when Britain’s economy is reeling from record high inflation, but also at a tumultuous time for its democracy. His unique identity – shaped by a mix of experiences across countries – explains why so many in India have sought this week to claim his rise as their own. Some latch on to his Hindu faith. Others to the possibility that India might follow Britain in putting high ideals over race or religion.

For now, Britain has crossed an important threshold. Mr. Sunak’s “elevation is welcome, even precious,” wrote Janan Ganesh, a columnist for Financial Times. “His virtue isn’t competence. It is rectitude. If all he does for a couple of years is give institutions their due and obey the law ... he will be a reprieve for British democracy.”

For India, meanwhile, a debate has been renewed over treating all citizens as equal, even able to become a prime minister.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Are drops of water afraid of the waterfall?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Catherine Spotts

When faced with uncertainty, we can let God’s love and peace, rather than fear, carry us forward.

Are drops of water afraid of the waterfall?

A friend emailed me with news that she was making a big move to another state and was a little apprehensive. She was learning to trust God more and more, but wanted some fresh spiritual ideas to support her prayers.

So I prayed to think of what to share, and ended up inspired by a flow of ideas that helped me feel the presence of God and helped me see that God, who is divine Love, cares for our every need. My friend had referenced a statement from “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, which I thought about deeply. It refers to fearlessly giving “a cup of cold water in Christ’s name” (p. 570).

Our supply of “cold water,” or inspiration, is ever fresh, supportive, and continuous. These inspired ideas keep on flowing all day, all night, forever. They are clear as crystal – shining bright, never dimming, never giving a sense of being overwhelmed. We actually live in an ever-flowing, perpetual stream of God’s love, joy, harmony, peace. These qualities are ours because we ourselves are spiritual ideas, created by God, divine Spirit, and we reflect Spirit’s attributes.

Life is not a bumpy ride. We are not tossed about. We ride safe, secure, and always forward. Just as a water droplet could not be afraid of the waterfall – it is safe in the river – fear is no part of our true, spiritual nature, because God is right here caring for us.

This meant my friend could be fearless when making big changes in her life. And sure enough, I soon learned that she was settling nicely into her new home and grateful for all the love she was experiencing there.

Each one of us can feel harmony. The river of the water of Life that proceeds from God is holding us safe, secure, and unafraid.

Adapted from the Oct. 10, 2022, Christian Science Daily Lift podcast.

A message of love

A lovely day for a picnic

A look ahead

Have a great fall weekend! We’ll see you on Halloween, when Sarah Matusek will report in from a Colorado softball field, where women in their 60s through 90s are finding joy in taking their turn at bat.