- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 11 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Rural labor shortage may bury a New York tradition

Grandma Brown’s baked beans have been a family tradition since I married my sweetheart in western New York. Substantial regional fare, not syrupy like the national brands, the beans were always on the to-buy list whenever we returned to New York State. But after the pandemic, Grandma Brown’s shut down, and the iconic yellow, red, and brown cans disappeared from store shelves. So on the way home from dropping my daughter Grace off at college in Rochester in August, we swung by Grandma Brown’s headquarters in Mexico, New York, to see what’s what.

The long, low, yellow plant was deserted, completely locked up with not even a security guard in sight. Next door at an auto parts store, a man at the counter said the owner wanted to reopen but she couldn’t find staff. “No one wants to work,” he explained.

That’s true, as far as it goes. Job openings, though still high, have fallen by some 1 million since their all-time records in the spring. But rural America is facing a worse job shortage than urban America. That is why food and other manufacturers have scrambled to raise wages to attract rural workers. “We have just seen a skyrocketing of pay rates,” says Greg Sulentic, a regional developer with Express Employment Professionals, who recruits workers for companies in Nebraska, Kansas, and Missouri.

While an entry-level worker at a rural manufacturer or distribution center might have started at $12 an hour before the pandemic, starting pay now ranges from $18 to $20 an hour, he says, which is very nearly on par with starting pay in Lincoln or Omaha, Nebraska. In these urban areas, the job shortage has begun to ease. In rural areas, the shortage is, if anything, greater than it was a year ago, he adds.

It’s not clear whether pay raises would solve the problems at Grandma Brown’s. (The company hasn’t yet returned my phone call.) What is clear is that if something doesn’t change soon, Grandma Brown’s beans won’t be available anywhere, except eBay, where the 80-year-old brand can still be found selling from $5 to $175 a can.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

A pastor, a football star, and the battle for a key Senate seat

Georgia is a growing economic powerhouse that represents, in many ways, America’s multiracial future. Its historic Senate race between two Black men offers contrasting visions, especially on matters of identity and division.

The Rev. Raphael Warnock and former football star Herschel Walker both grew up in modest, Christian homes, just over 100 miles apart in Georgia. Both harnessed an unusual drive to achieve success.

Now they’re facing off in one of the most important Senate races in the country.

The incumbent Democratic senator and erudite pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, Senator Warnock casts his politics as an extension of his ministry, advocating for people who are hungry or imprisoned. He’s seeking to re-create the coalition of Black voters and white progressives who last year propelled his win and gave Democrats control of the Senate.

Mr. Walker, a Heisman Trophy winner turned businessman who has been endorsed by Donald Trump, advocates dropping identity politics to heal a house divided and focus on national security and prosperity. He’s drawing support mainly from white conservatives. Despite Mr. Walker being outspent and facing a series of scandalous allegations, polls show him in a dead heat with Mr. Warnock.

In a nation grappling with past and present injustices, these candidates offer starkly different ideas about how best to address America’s inequities and divisions. That makes this face-off between two Black men, in a former Confederate state that recently became majority nonwhite, both historic and a potential harbinger.

A pastor, a football star, and the battle for a key Senate seat

When Raphael Warnock was six years old, his mother discovered him preaching his heart out in his room, huffing and puffing as he tried to imitate the soaring cadences of revival preachers he’d heard at church in Savannah, Georgia.

Some 115 miles inland, a young Herschel Walker was also gasping for breath, sprinting down the railroad tracks near his house as he embarked on a rigorous solo training regime that would transform him and his life.

Raised in modest, Christian homes, both men harnessed an unusual drive and talent to achieve pinnacles of success – encountering hardship, losses, and racism along the way. Now, they’re facing off in one of the most important Senate races in the country.

That’s about where the similarities end.

Senator Warnock, whose narrow 2021 win unexpectedly flipped control of the Senate to the Democrats, is hoping to once again assemble a winning coalition of Black voters and white progressives who have dramatically shifted Georgia’s politics in recent years. As the senior pastor of the influential Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, where he returns every weekend, he casts politics in moral terms, as the proving ground for his work in the pulpit.

Mr. Walker, a former University of Georgia football star endorsed by Donald Trump, has pulled into a dead heat with Mr. Warnock, despite facing a series of damaging personal allegations in the campaign. Most prominently, two women have accused Mr. Walker, who opposes abortion rights, of encouraging them to terminate pregnancies and paying for the procedure – charges he denies.

The Heisman Trophy winner turned businessman is drawing support mainly from white conservatives, including many evangelical voters who say they are willing to forgive past sins. “In Georgia, there’s God, Jesus, and Herschel Walker – that’s our holy trinity,” says one rally attendee who declined to give his name.

The outcome could once again determine which party will control the U.S. Senate. Beyond that, the face-off between two Black men, in a former Confederate state that recently became majority nonwhite, is both historic and a harbinger for U.S. politics. At a time when the nation is grappling with past and present injustices, these candidates represent competing sets of values and ideals – and different ideas about how best to address America’s inequities, divisions, and domestic and foreign policy challenges.

“Of all the races I’ve watched, this one has captivated my mind,” says Karen Owen, a political scientist at the University of West Georgia in Carrollton, who is writing a book about this Georgia Senate race. “It is their story. It is the historical moment they are providing for a state that has not had beautiful days in history, that has struggled to make a change. They are representing the change that we have here.”

A lifelong ministry

The youngest son of two Pentecostal preachers, growing up in public housing, Raphael Warnock loved science. But after a failed fifth-grade attempt to hit the jackpot with a new pesticide, he began focusing on preaching, giving his first public sermon around the same time.

As a high schooler, he would visit the local library and listen to LPs of Martin Luther King Jr.’s speeches, drawn to the idea of getting the church to “pray with its feet” by fighting racial injustice and oppression in society. The young Raphael followed the civil rights icon’s path, attending his alma mater and, at 35, becoming the senior pastor of the Ebenezer Baptist Church – one of the most influential Black churches in America, where Reverend King, his father, and grandfather once preached.

Along the way, Reverend Warnock extended his ministry through social activism. He advocated for his brother, a Gulf War veteran and rookie police officer with no previous criminal record who was sentenced to life in prison after being caught in an FBI drug sting, and was released after 22 years. He unsuccessfully tried to stay the execution of another man, convicted of killing a white off-duty police officer, after several witnesses recanted their testimony. Such experiences deepened Reverend Warnock’s resolve to address racial bias in the criminal justice system.

“In an area like this, people wonder why ministers run for office,” says Erric Michael Bostic, a rural carrier for the U.S. Postal Service in Swainsboro, while awaiting Senator Warnock’s arrival for a campaign rally. “I think he’s fitted for it because of his background, not in spite of his background.”

Inside the darkened Swainsboro City Auditorium, the mic goes in and out as Mayor Pro Tem Bobbie Collins introduces the most high-profile Democrat anyone here can remember visiting this city of 7,500. Though Swainsboro’s population is majority Black, chronically low turnout means white Republicans tend to win most of the races here. Local activists persuaded the reverend to come – in part by telling him his opponent, who grew up in nearby Wrightsville, had already visited several times.

When Senator Warnock takes the podium in jeans, collared shirt, and a down vest, he thanks the crowd for being part of the multiracial “coalition of conscience” that sent him and fellow Democratic Sen. Jon Ossoff to the U.S. Senate last year.

“People didn’t see Georgia coming. But Georgia saved the whole country,” he says to cheers.

The serious demeanor Reverend Warnock displays when striding through the U.S. Capitol in Washington, where he is one of only three Black senators, is replaced here by a pastoral warmth.

“We been on this journey for a while now,” he says, adding: “It may feel like we just did this.” The senator was elected in January 2021 to fill out the remaining two years of his predecessor’s term and is now running for a full six-year term.

As he ticks off some of what Democrats have accomplished with control of the Senate, from providing benefits for veterans who worked near toxic burn pits to reducing the cost of prescription drugs, the audience engages in a kind of call-and-response that feels more church than campaign trail.

“I wrote the provision–”

“All right!” says the crowd.

“– to cap the cost of prescription drugs [for] seniors,” he says.

“Yeah, thank you!” the voters respond.

He adds that he also wrote another provision to cap the cost of insulin. The senator’s efforts to expand health care coverage are a strong selling point for Salena Williams, who sometimes attends Reverend Warnock’s church when she’s in Atlanta.

“I saw the compassion that he had for people,” says Ms. Williams, who was burned in a kitchen grease fire and lost her health benefits when she took a job with greater flexibility to care for her mom. “He’s doing the work, not just talking about it.”

Senator Warnock has raised more money than any other Senate candidate in the country, and has spent $76 million on the race, more than twice what Mr. Walker has spent. Still, Democrats appear worried that the the football star is gaining ground.

Last week, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer was caught on a hot mic telling President Joe Biden, “The state where we’re going downhill is Georgia.”

“It’s hard to believe that they will go for Herschel Walker,” the New York Democrat added.

Overcoming obstacles

Mr. Walker knows something about people not believing in him. As a child, he endured taunts brought on by both a stutter and chubbiness.

“Herschel is a gggirl-schel,” the kids would yell. He was so desperate for friends that when his parents could spare a nickel or dime, he would sometimes offer it to another child on the playground in exchange for a few minutes of conversation, according to his book, “Breaking Free.” Thanks to a strict regime of running and calisthenics, slotted in between school and chores, he went on to become the most highly sought-after high school football player in the country and led Georgia to a national championship.

A fierce self-reliance led him down unorthodox paths at times – ramming his way through obstacles just as he did on the football field. He insisted his dentist remove his wisdom teeth without anesthesia, refused to lift weights, took ballet, and dropped out of college to play pro football, according to his book. The veracity of some of his claims, however – such as having been valedictorian of his high school class – has been questioned. Neither Johnson County High School nor the local board of education would confirm to the Monitor whether he was valedictorian; a CNN review was only able to determine that he had been an ‘A’ student.

Along the way, Mr. Walker met Donald Trump, who owned the first pro team he played on and became a mentor. The former president’s endorsement last fall allowed Mr. Walker to sail through the GOP primary.

On the trail, Mr. Walker has maintained an “I’m just a country boy” posture, in contrast to Reverend Warnock, who holds a Ph.D. and leans into his erudition. In the run-up to the candidates’ only debate, the former football star tried to lower expectations, telling reporters: “I’m not that smart,” but adding, “I will do my best.”

He frequently describes himself as a Christian man, starting each rally by acknowledging Jesus Christ as his Lord and accusing Reverend Warnock of cherry-picking from the Bible to justify his politics – including the senator’s support for a woman’s right to choose an abortion. “If you read the Bible more, God said, ‘Choose life,’ ” Mr. Walker said in the debate.

Critics – including Mr. Walker’s own son – have denounced his anti-abortion stance as hypocritical. The campaign has been rocked by allegations from two separate women accusing him of encouraging them to get abortions after getting them pregnant. Both women chose to remain anonymous, but this week one gave an on-camera interview with ABC News. “He was very clear that he did not want me to have the child,” she said. “He said that because of his wife’s family and powerful people around him, that I would not be safe and that the child would not be safe.”

Mr. Walker has flatly denied the allegations. “This was a lie a week ago, and it is a lie today,” he said. Republicans also note that Senator Warnock has been dogged by personal allegations of his own. His ex-wife accused him of running over her foot with his car and, in a police body cam recording obtained by Fox News, calls him a “great actor.”

Still, Mr. Walker has owned up to some past mistakes, including an affair. His ex-wife has said he tried to choke her and once held a gun up to her temple, which he told an interviewer he did not recall. In his memoir, he acknowledges having been diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder, formerly known as multiple personality disorder, but in a campaign ad says he has overcome his mental health challenges through God’s grace.

“He has some problems, and I just hope he has a handle on it, for his own sake,” says John Garner, a white retired mining engineer who lives outside Mr. Walker’s hometown of Wrightsville and has a Herschel sign in his front yard. “But he’s not a man you can count out.”

The politics of race

Emerging from his campaign bus in Dalton, Georgia, wearing a white polo shirt, Mr. Walker hugs a local GOP chairwoman decked out in knee-high sparkly red boots and then does a few hip circles as if warming up for a game.

On stage he uses humor and everyday metaphors to illustrate where he believes Washington is going wrong.

“I love to spend someone else’s credit card, don’t you?” he asks, poking fun at Democrats’ spending habits.

He criticizes his Democratic opponent as a magician for touting his role in securing $400 billion in student debt relief while not addressing where that money will come from.

“He wanted you to look at this hand,” waving above his head, “as he’s stealing from you with this hand,” he adds, motioning near his pant pocket. “Because what he’s doing is raising your taxes. So don’t think he’s giving you anything.”

Some of his biggest applause lines come when he criticizes Democrats’ support for transgender children, athletes, and soldiers. “Iran, Russia, and China aren’t talking about pronouns,” he says. “They’re talking about war.”

“What he says makes sense. He’s down to earth,” says Shirley Henson, a GOP precinct captain and substitute high school teacher who – like nearly everyone at this rally – is white. She particularly appreciates Mr. Walker’s support for law enforcement and his call to stop the influx across the southwest border of fentanyl – a potent drug that was found in her daughter’s body after she died suddenly.

An hour east through the mountains in Jasper, Mr. Walker speaks in front of a gun shop to another group of largely white supporters, some of whom have holsters on their hip. Connie, a former Democrat who doesn’t want to give her last name, says she likes what he has to say about inflation and the economy. She isn’t bothered by the various scandals that have hit his campaign, most of which she thinks are lies.

“I know Herschel had problems in the past,” she says. “But I’m a believer in redemption.”

Part of the calculus for Republicans in this formerly deep-red state is that Mr. Walker can win among white conservatives but also potentially peel off a number of Black voters. Indeed, Corey Bruno, a Black independent voter in Atlanta who is a “huge fan” of Democratic gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams, says he is considering voting for Mr. Walker.

“Warnock is alright,” he shrugs, but raises concerns about having a pastor involved so directly in politics. Mr. Bruno says he knows about the accusations against Mr. Walker, but is intrigued by the idea of sending someone he regards as a folk hero to Washington.

Other Black voters, however, are scornful of what they see as a cynical ploy by the GOP to win their votes. “I don’t care about race, I care about having qualified people in Washington,” says Latasha Glass, a Democrat from Atlanta.

Warnock supporter Shayna Boston, a Black entrepreneur in Swainsboro, says Mr. Walker doesn’t even appear to be trying to reach out to the Black community there. “He’s talking to people that don’t look like us,” she says.

Mr. Walker rejects identity politics and criticizes his opponent’s focus on race, invoking Dr. King’s hope that people would come to be judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. Critics say he’s allowing white Republicans to avoid grappling with racial injustice.

It’s a familiar criticism, going back to high school, when he did not stand in solidarity with his Black peers after the white principal made a racially charged comment toward a student, igniting protests.

“I never really liked the idea that I was to represent my people,” Mr. Walker later wrote about the incident in his book. “My parents raised me to believe that I represented humanity.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated to correct the name of the university where Prof. Owen teaches.

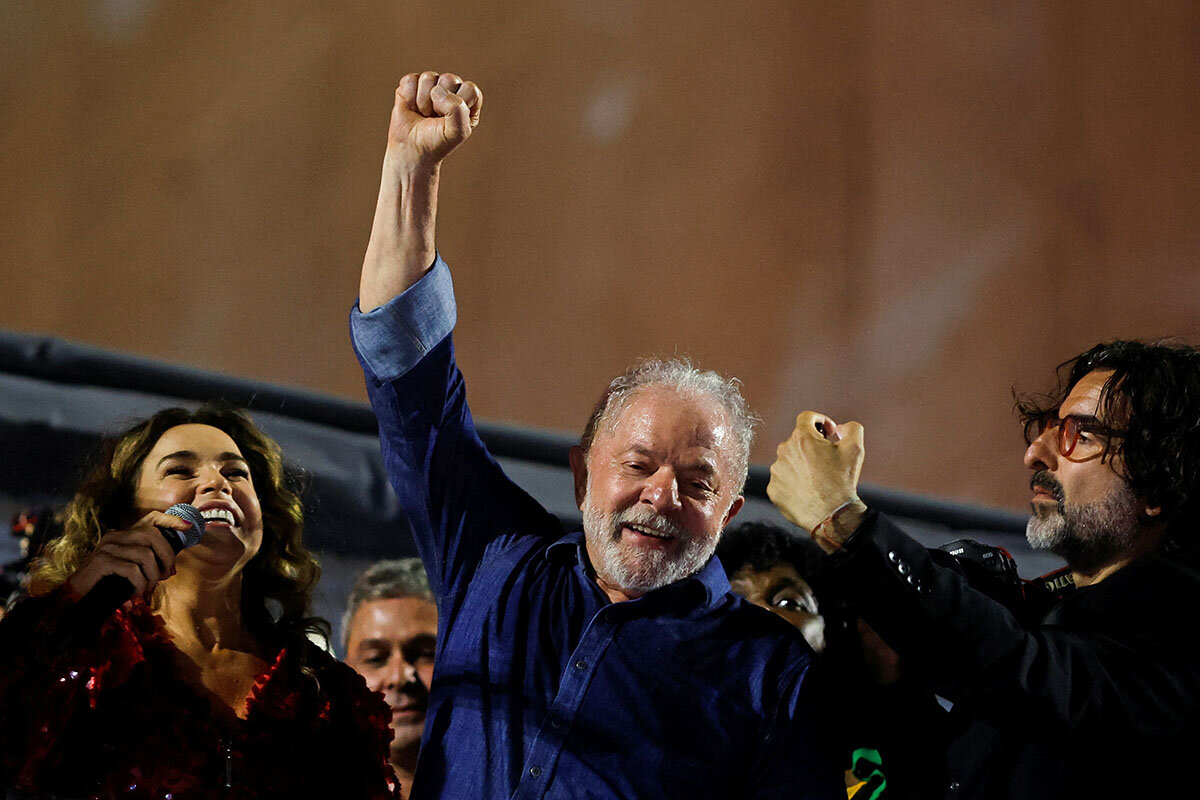

Can President-elect Lula bridge deep divides?

Can a president lead without cooperation? Brazil’s President-elect Lula defeated right-wing incumbent Jair Bolsonaro, but won by less than two points. He says he’ll work to protect the Amazon and curb hunger, but is up against a deeply divided political and popular landscape.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Andrew Downie Contributor

President-elect Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva addressed a top issue of concern in deeply divided Brazil during his acceptance speech on Sunday, saying “No one is interested in living in a divided country.” His resolve to govern for all Brazilians – despite nearly half the nation casting ballots for incumbent Jair Bolsonaro – will be tested from the start, not only among the population, but as he aims to govern with a Congress dominated by right-wing, Bolsonaro allies.

Sporadic demonstrations emerged this week, with far-right groups blocking highways and burning barricades in 20 of Brazil’s 27 states on Tuesday. After two days of silence, Mr. Bolsonaro's team implicitly acknowledged the results Tuesday by agreeing to start the process of transition. Lula’s win was historic in many ways; it was the smallest winning margin and the first time a sitting president has lost a reelection bid in modern Brazil. It also marked his return to power after two terms served between 2003 and 2010.

The protests, and the close results of the runoff, underscore the two distinct visions at play in a nation crying out for unity.

“Brazil’s social fabric has been irreversibly torn,” Rosana Pinheiro-Machado, a Brazilian academic who studies the far-right, wrote in a column for the UOL website.

Can President-elect Lula bridge deep divides?

It’s common to hear after any election that “the hard work starts now,” but rarely has it been as appropriate as in Brazil this week. President-elect Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva faces the enormous task of uniting a nation divided almost precisely down the middle, and putting a rehabilitated Brazil back on the map.

Lula, as he is universally known, beat the far-right incumbent Jair Bolsonaro in a runoff on Sunday, winning with 50.9% of the votes, the slimmest margin in almost 30 years.

While Lula’s victory was a relief for his supporters, tired of the machinations of a populist president whose botched handling of the pandemic and crude attacks on opponents turned Brazil into an international pariah, nearly half the country is in mourning. The far-right fears Brazil will lurch to the left under its new leader, becoming “the next Venezuela,” rife with corruption and economic crises.

In his acceptance speech Sunday night, Lula spoke directly to the cooperation and unity that will be necessary over the next four years: “There are not two Brazils. We are a single country, a single people, a great nation,” he said. “No one is interested in living in a divided country.”

His resolve will be tested not only on the popular front, but as he aims to govern with a Congress dominated by right-wing, Bolsonaro allies. And echoing the turmoil faced by the U.S. after the 2020 presidential vote, Mr. Bolsonaro did not concede defeat when he finally addressed the nation almost 48 hours after the polls closed. His team only acknowledged the results and said a transition would begin.

Sporadic demonstrations emerged this week, with far-right groups blocking highways and burning barricades. Police were breaking up the protests on Tuesday morning but there were still incidents in 20 of Brazil’s 27 states.

The protests, and the close results of the runoff, underscore the two distinct visions at play in a nation crying out for unity.

“I think the main thing is for Lula to slowly rebuild confidence and establish consensus,” says Richard Lapper, author of “Beef, Bible and Bullets: Brazil in the Age of Bolsonaro.” “Stability – economic and social – is the key.”

“Enormous” challenges

On Sunday night, the muggy main streets of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro were filled with revelers wearing red and plastered with Lula stickers.

People hugged and sang together on the metro, then danced behind drummers and swigged drinks from foam coolers. Across the country, windows and balconies rang out with a two-word phrase: “Fora Bolsonaro!” or “Out Bolsonaro!”

“I was on Paulista Avenue when Lula won 20 years ago, but this time it was much more special,” says Ana Paula França, a nutritionist. “We’ve waited four years for this, through the truculence and boorishness and the disregard for education and health. This was a cry of freedom.”

Lula’s win was historic in many ways. It was the smallest winning margin and the first time a sitting president has lost a reelection bid in modern Brazil. It also marked Lula’s return to power after two terms served between 2003 and 2010.

One of eight children who was so poor he shined shoes for a living, Lula led a metalworkers union before entering politics and losing three consecutive presidential elections. His perseverance was rewarded with wins in 2002 and 2006, and he left office with approval ratings above 80%. Jailed in 2017 as a corruption scandal engulfed his Workers’ Party (PT), he was released almost two years later after a judge annulled the charges.

The Brazil he will lead is almost unrecognizable from the one he governed in the 2000s. The challenges, he admitted on Sunday, are “enormous,” both in terms of policy and people.

Half the country cannot forgive the PT for the corruption scandals that plagued their four successive governments, and the other half has developed a deep loathing for the far-right.

Lula promised to be president for every Brazilian, but he risks touching off deep-seated sensitivities with promises like repealing 100-year secrecy classifications Mr. Bolsonaro made on some documents that analysts say could be hiding questionable dealings. If Mr. Bolsonaro is brought to trial for his mishandling of the pandemic or dissemination of fake news, his supporters could feel personally attacked.

“Brazil’s social fabric has been irreversibly torn,” Rosana Pinheiro-Machado, a Brazilian academic who studies the far-right, wrote in a column for the UOL website, one of Brazil’s biggest. “I don’t believe in any politician who says they will bring peace and love back to Brazil,” she wrote, referring to his campaign slogan two decades ago, “Lula, peace, and love.”

Finding the center?

Peace and love would be a start, but there are more tangible problems to be addressed in what has long been a country of extremes: Inflation is volatile and inequality is increasing.

Following the pandemic, which claimed the lives of nearly 700,000 Brazilians and plunged many back into poverty, one in four Brazilians say they do not have enough to eat, according to a study by the Datafolha agency.

Deforestation ravaged the Amazon under Mr. Bolsonaro’s watch, increasing each year over the past four years as the president hollowed out oversight bodies and encouraged prospectors, loggers, and farmers to invade the rainforest.

Lula made a name for himself during his first two terms in office, lifting millions of Brazilians out of poverty and slashing deforestation by 70%. He’s promised to focus on ending hunger in Brazil, bring back environmental oversight bodies, and create a separate ministry for Indigenous people.

“We want to create a new circle of prosperity, through democracy, fighting poverty, and sustainability,” Marina Silva, Lula’s former environment minister and one of his policy advisers, told reporters on the eve of the election. “You can’t do that in four years, but you can build the pillars in four years.”

A commodities boom helped finance much of Lula’s spending in the early 2000s, but the global economy is different now. Already, a large part of next year’s federal budget has been apportioned by legislators, leading to cuts in health, education, and social spending – all of which are Lula’s priorities.

How well he manages will depend on his negotiating skills. Lula is known as the consummate politician, but even his experience will be tested.

Congress will be dominated again by the right, but much depends on how faithful they are to “bolsonarismo” – and how much common ground Lula can find with them. His campaign was backed by the broadest political front since the end of the dictatorship in 1985, but that might not count for much in Brazil’s notoriously dysfunctional Congress, says Mr. Lapper.

“He should avoid ideology, keep the hard left at a distance, avoid entanglement with divisive identity politics, and that will restore some confidence,” Mr. Lapper says.

“He has to deal with the center.”

Post-hurricane, Canada charts new relationship with the sea

Canada never experienced a storm as powerful as September’s Hurricane Fiona. Now, Prince Edward Island, like many coastal regions, is rethinking how to coexist with an unpredictable ocean.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Moira Donovan Contributor

On Sept. 24, Hurricane Fiona roared across Atlantic Canada, leaving catastrophe in its wake, including two deaths. On Prince Edward Island’s North Shore, the storm ripped up trees, reduced wharves to splinters, and flooded structures.

The recovery is expected to take years. But given what Fiona has shown about the growing threat posed by hurricanes, the more transformative effect could be still to come, as Atlantic Canadians rewrite their relationship with the sea.

After Fiona hit Newfoundland’s southwest coast, Shawn Bath found communities devastated by storm surge. In many places, wharves had been smashed like toothpicks, scattering fishing nets and gear into the water. Mr. Bath and his cleanup crew made their way to one small community and got to work. Two weeks later, that shoreline is clean.

But in the long term, Mr. Bath says the way harbors are laid out needs to be rethought. For example, fishing infrastructure has traditionally been placed close to the water because that’s where it made the most sense to be. But that calculus has changed.

“There’s no point in rebuilding and filling all these stages with nets again,” he says, “if two years down the road the same thing happens.”

Post-hurricane, Canada charts new relationship with the sea

Robbie Moore spent a week preparing his oyster farm as Hurricane Fiona barreled toward Prince Edward Island in late September. But that didn’t spare it from the impact.

On Sept. 24, Fiona roared across Atlantic Canada, leaving catastrophe in its wake, including two deaths. Prince Edward Island recorded 92 mph winds, and on the North Shore, where Mr. Moore’s farm is located, the storm ripped up trees, reduced wharves to splinters, and flooded structures. By the time he could get to his farm to assess the damage several days later, he found some sections had vanished, and this year’s oyster crop had been tossed into the treeline, 30 feet from the high-water mark.

Still, he counts himself relatively fortunate. Some people lost everything, and as much as people had prepared, there was no way to prepare for the damage Fiona caused. “There’s a lot of people very discouraged right now,” he says.

The recovery is expected to take years. But given what Fiona has shown about the growing threat posed by hurricanes, the more transformative effect could be still to come. As hurricanes become a more regular, immediate danger up and down North America’s Eastern Seaboard, Atlantic Canada – like regions from the Gulf Coast to Florida to New England – is beginning to grapple with how climate change is rewriting people’s relationship with the sea.

“Pictures don’t do it justice”

While Atlantic Canada is no stranger to volatile weather, Fiona marked a departure. Past storms, such as Hurricane Dorian in 2019, had weakened before they made landfall. But Fiona retained much of its strength, making it the most powerful storm to ever hit Canada.

University of Prince Edward Island climatologist Adam Fenech says that while Fiona was unprecedented, the storm was not unanticipated, given projections of stronger storms in the Atlantic hurricane season. “All the things that we’ve been talking about for 30 years are all coming true,” he says.

Despite that consensus, Dr. Fenech has spent years playing Cassandra to an at-times skeptical public. Half a dozen years ago, when Dr. Fenech was invited to give a talk about coastal erosion at a cottage development on Prince Edward Island’s North Shore, he warned that many of the properties could disappear in a big storm. Residents were unconvinced. “Let’s just say they didn’t want to sit and chat about what the possibilities were,” he says.

When Fiona hit, 12 cottages in that development were swept off their footings; several were swallowed wholesale by the ocean. In other places, people’s year-round homes were destroyed.

But in a region where communities have deep ties to the coast, housing isn’t the only concern. Atlantic Canada is the site of Canada’s most lucrative fisheries, operating out of nearly 200 small harbors dotting the coastline – nearly three-quarters of which were affected by Fiona in some way.

For many harbors, the destruction caused by Fiona will mean an expensive rebuild. But some people are saying the reconstruction should look different.

When Fiona hit Newfoundland’s southwest coast, Shawn Bath was a day’s drive away; as the scale of the damage came to light, he loaded his truck, hitched his boat, and headed across the province.

There, he found communities devastated by storm surge. One man he encountered in Port aux Basques, where at least 80 houses were damaged, described running out the back door as the ocean came in the front, and clinging to a light pole to avoid being swept out to sea.

Mr. Bath also found shorelines littered with debris. In many places, wharves and fishing stages had been smashed like toothpicks, scattering fishing gear into the water. Mr. Bath and his crew – who run a marine debris cleanup project called the Clean Harbours Initiative – made their way to a small community called Burnt Islands, and got to work.

Forty boatloads and two weeks later, that shoreline is clean, but it’s just one small section of a wide area. “It’s overwhelming,” says Mr. Bath. “Pictures don’t do it justice.” And he’s worried that there are more than a thousand fishing nets drifting along the bottom of affected harbors. He says urgent action is needed to remove nets from the water before they can damage ecosystems – and undermine local fisheries.

But in the long term, Mr. Bath says the way harbors are laid out needs to be rethought. Fishing infrastructure has traditionally been placed close to the water because that’s where it made the most sense to be. But that calculus has changed.

“There’s no point in rebuilding and filling all these stages with nets again, if two years down the road the same thing happens,” he says. “Keeping fishing gear on the water’s edge is no longer a reasonable thing to do.”

“The island is different now”

These harbors aren’t the only landscape that could be changed in Fiona’s wake. In places with sandy coastlines, as the storm passed, residents found the rolling dunes that characterized areas like the North Shore of Prince Edward Island had completely disappeared.

For Prince Edward Island musician Tara MacLean, who grew up playing in the dunes, the shock of seeing a beloved landscape suddenly vanish was indescribable. “I can’t imagine a more sacred place to Prince Edward Islanders than the shoreline,” she says.

Sand dunes are a naturally dynamic ecosystem. Given time – and the right conditions – they could return. But Ms. MacLean is worried that, given how Fiona portends the storms to come, the dunes may never come back. “I don’t think I’ve even touched the grief that is coming for the way the island was,” she says. “The only way that I know is just to be with that feeling and learn to accept that the island is different now.”

Ms. MacLean says the sorrow for what’s been lost should serve as a wake-up call on the risk that climate change poses to the region. But it’s that emotional connection to the water that could also make changing the relationship to it difficult, and when things return to normal, the allure of living close to the water may return, too.

Some Atlantic provinces have already put in place measures to guard against that. In Nova Scotia, the provincial government has passed first-of-its-kind-in-Canada legislation for how close people can build to the water, regulations for which are to come into effect in 2023. Advocates say Fiona has shown why other Atlantic provinces need to follow suit.

In the meantime, even existing settlements may eventually need to move. For years, managed retreat – the idea of pulling back from the water – has been a third rail in Canada, says Kate Sherren, a social scientist at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Fiona has changed that. “It wouldn’t seem ethical anymore, to put people in what is so clearly harm’s way, quite aside from the waste of money that would represent.”

In Canada, there is little insurance available for coastal flooding – meaning that for the vast majority of those whose homes were affected by storm surge, the damage is not covered. The insurance industry is currently in talks with the federal government about a national public-private flood insurance program, similar to the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s. But Dr. Sherren says any policies should encourage communities to work with increasing coastal volatility, rather than clinging to a reality that no longer exists.

“We’ve been building on and living on this borrowed space,” she says. “When these events happen, there needs to be a program in place that can step in to help people to make decisions other than building back where they were.”

“You can’t control water”

Some are already looking at making a shift.

Rita Raymond grew up in St. Vincent’s, on Newfoundland’s east coast. That side of the province was largely spared Fiona’s impact, but severe storms have nonetheless become more frequent, often washing out the community’s main road. That’s changed how Ms. Raymond – who spent decades living in British Columbia and moved back to the community 14 years ago – feels about living on the coast.

When she and her husband bought their house, which is five minutes from the beach, she says she didn’t see the ocean as a threat. Now, unlike the tourists who come to stay at her bed-and-breakfast because they want to be close to the water, Ms. Raymond says she’d like to get farther away.

“In British Columbia, we had fire hazards in the summertime and a fear of fire, and I always thought fire can be controlled, to a point,” she says. “But you can’t control water.”

Ms. Raymond says she’s contemplating buying on higher ground or moving to another community.

But in some places, moving is not possible.

On Prince Edward Island’s North Shore, Mr. Moore says he’s spoken to oyster farmers who are too dispirited by the scale of their loss to start over. Mr. Moore himself is facing volatile conditions going forward – it takes roughly eight years for an oyster to reach its full size, well in excess of the interval between recent hurricanes. Still, while he says he’s planning on making changes to respond to the threat of worsening storms, there’s only so much he can do. He has a plot to farm – an oyster lease that’s existed for almost a century – and he’s constrained by those boundaries.

“Your hands are sort of tied, right?” he says. “Something can always come up, and you can’t not try to rebuild.”

Points of Progress

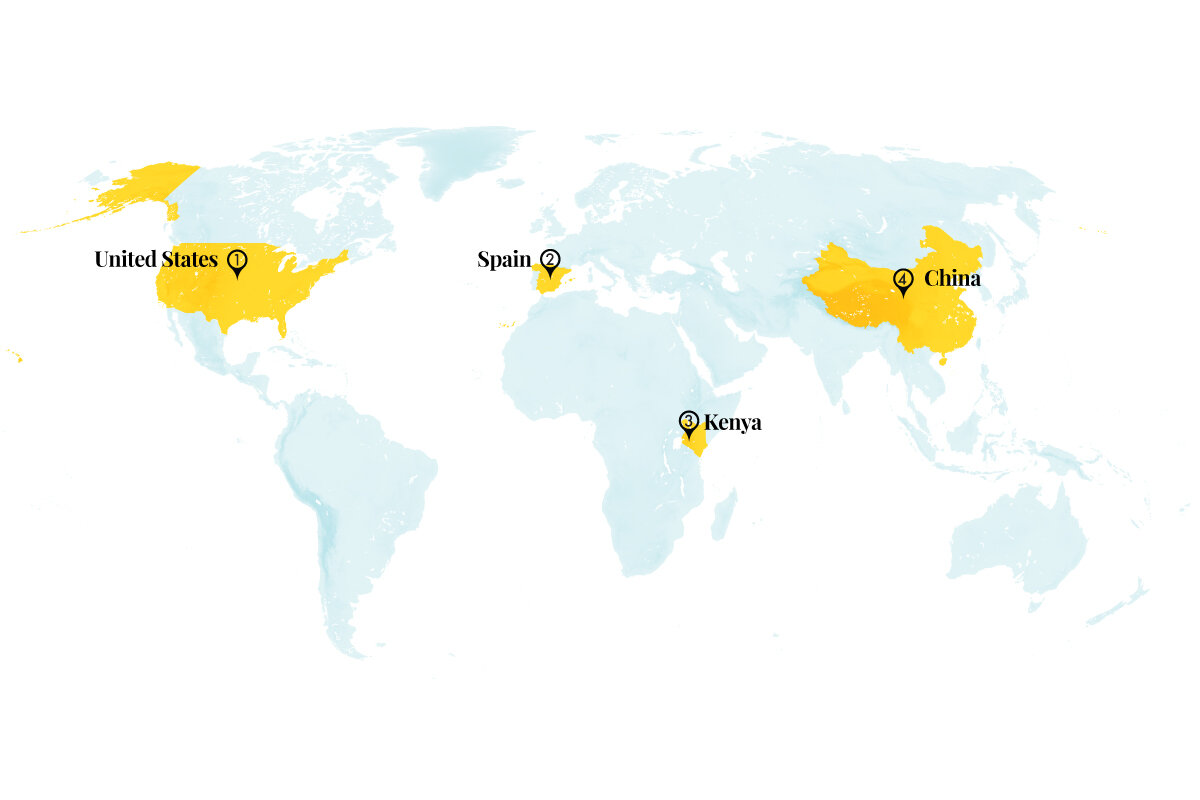

Fueling up: Free school meals in US and geothermal power in Kenya

In our progress roundup, governments honor people’s dignity by feeding students in U.S. schools, lowering poverty in China, and giving labor protections to domestic workers in Spain. Also, we highlight innovations in mapping land use and Kenya’s leadership in geothermal energy.

Fueling up: Free school meals in US and geothermal power in Kenya

1. United States

More states across the U.S. are equalizing access to nutritious meals for all students. As a COVID-19 relief measure, the U.S. Department of Agriculture reimbursed school districts for providing free breakfast and lunch to students, which expanded services beyond low-income children but ended at the start of the 2022-23 school year.

California and Maine passed legislation to permanently finance the universal meals program, while states from Colorado to Minnesota have proposed similar measures. Meanwhile, Nevada, Vermont, and Massachusetts extended free meals for the current school year.

Research shows that participation in school meals improves test scores and reduces negative behaviors, while advocates suggest that universal meals can help prevent the stigma of low-income students being singled out. “The kids are eating way more and they’re more focused, eager to learn and they’re just happier,” said California teacher Alyssa Wells. “They’ve got one less thing to worry about.” The USDA and school districts are also working to strengthen connections between schools and farms to provide meals using more fresh, local ingredients.

Sources: The Guardian, NPR, Edsource

2. Spain

Over 370,000 domestic workers in Spain now receive the same labor protections as other workers. Under a resolution that went into effect at the start of the month, domestic workers now have the right to unemployment benefits, health and safety protections, and just cause before dismissal. The new legislation will primarily impact women, who make up 95% of the nation’s domestic labor force, many of them immigrants.

Workers’ groups and trade union organizations fought for years to achieve these labor protections. And for families who employ domestic help, the government will pay a portion of the costs to offer benefits to workers. Yolanda Díaz, Spain’s second deputy prime minister and minister of Labor and Social Economy, said the move helps “reach out to all those women who, unjustly separated from the rights and guarantees that corresponded to them, will today be able to aspire to decent work and a more peaceful life.”

Source: International Labor Organization

3. Kenya

A longtime leader in the sector, Kenya has made a name for itself as a geothermal powerhouse. The country’s energy mix includes more geothermal than any other single source, as more than 800 megawatts of generating capacity have come online since 1981. Hydropower and wind are the other renewables that make up more than 85% of Kenya’s electricity generation.

The region’s Great Rift Valley, which spans much of East Africa, is estimated to hold a geothermal potential of 10 times the current level of production. Second only to solar power in abundance, geothermal is still not a perfect solution: The construction of geothermal wells can displace Indigenous communities and encroach on natural ecosystems. “Kenya is on a transition to clean energy that will support jobs, local economies, and the sustainable industrialization,” said newly elected President William Ruto. “We call on all African states to join us in this journey.”

Sources: Reasons to be Cheerful, GDC Kenya

4. China

Nearly 800 million people in China have been lifted from poverty since 1980. The speed and extent of poverty reduction is historically unprecedented and accounts for nearly three-quarters of the global decline in extreme poverty during that time, according to a joint report published earlier this year by the World Bank and China’s Development Research Center of the State Council. Poverty dropped from 88.1% to 0.3% in four decades using the $1.90 poverty line. In rural areas, the percentage of people living in poverty according to China’s national standards fell from 97.5% in 1978 to 0.6% in 2019.

The study attributes success to rapid economic growth on the one hand, boosted by improved agricultural productivity and investment in infrastructure, and targeted poverty alleviation policies and social protections on the other. While China declared the eradication of extreme poverty according to its own poverty thresholds last year, a significant portion of the population remains economically vulnerable according to higher standards used in upper-middle-income countries. For the future, the report recommends a shift in focus toward closing inequality gaps in income and opportunities.

Sources: The World Bank and The Development Research Center of the State Council, China

World

Researchers launched the world’s highest-resolution land cover mapping tool that works in near-real time. Known as Dynamic World, the data set enables access to information about urban development, wetlands, forests, crops, and more at a fraction of the time it used to take. That means decision-makers no longer have to wait months to address disturbances to ecosystems or better manage changing land conditions.

Dynamic World uses data from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2 satellites, which compile over 5,000 images from around the globe every few days. That data is then streamed into an AI platform; anyone can access the information for free through monitoring platforms Google Earth Engine and Resource Watch. Users can also compare land-use maps over time, starting in 2015. Dynamic World has the potential to “trigger a level of action that we have never seen before” by bringing landscapes to life for observers, said Wanjira Mathai, vice president and regional director for Africa at World Resources Institute.

Source: Mongabay

Essay

Bringing dignity to Mexican food, a tortilla at a time

Authentic corn tortillas require time-intensive – even scientific – prep work. But for chefs who swear by them, the methods offer a way to explore foods and cultures with respect.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

I still remember the afternoon spent in Belize grinding corn to make tortillas.

A local woman had offered to teach a group of us. First, we separated dried kernels from the cob. Then, she showed us a bucket of kernels that had soaked overnight in water with dissolved lime. She washed and drained the corn, and we got to work grinding it. We passed the dough through the grinder a second time to get rid of the gritty texture. Then, the flattened balls of dough were nestled on a griddle over an open fire. It was hot, hard work.

This process of soaking corn in alkalized water to break down the outer hull of the kernel is called nixtamalization. More Mexican chefs in the United States are reviving nixtamalization to make authentic corn tortillas, says Chef Gustavo Romero of Minneapolis. “I don’t think you can really know or understand people until you understand their culture and what they eat,” he says.

In my tortilla-making class in Belize, we asked our teacher how many tortillas she made each day for her family. “About 75, three times a day,” she said. It takes her six hours. For people used to ripping open bags of mass-produced tortillas, that was a lot to process. But to our hostess, it was simply the only and best way.

We agreed.

Bringing dignity to Mexican food, a tortilla at a time

I still remember the afternoon spent in Belize grinding corn to make tortillas. I was staying at an ecolodge, and a gracious local woman had welcomed our group into her thatched-roof home to tutor us in this task. First, we separated dried kernels from the cob. Then, she showed us a bucket of kernels that had soaked overnight in water with dissolved lime. She washed and drained the corn, and we got to work grinding it. We passed the dough through the grinder a second time to get rid of the gritty texture. Then, the flattened balls of dough were nestled on a griddle over an open fire. It was hot, hard work.

This process of soaking corn in alkalized water to break down the outer hull of the kernel is called nixtamalization. More Mexican chefs in the United States are reviving nixtamalization to make authentic corn tortillas, says Chef Gustavo Romero of Minneapolis. “I don’t think you can really know or understand people until you understand their culture and what they eat,” he says.

Chef Romero, who runs Nixta, an artisanal tortilleria, is passionate about reviving time-honored techniques to bring a sense of dignity to Mexican food, which, he says, became synonymous with “fast” and “cheap.”

“That’s not what our food is,” he says. “That’s not how it started.”

In ancient practices, nixtamalization was done with wood ashes, and that’s where the name comes from. Nextli (ashes) combines with tamalli (tamale) in Nahuatl, an Aztec language spoken across Mexico. Chef Romero, who uses powder from ground volcanic stone to alkalize water, says this process allows the corn to absorb more calcium and potassium, making for more nutritious tortillas. He uses 18 to 20 varieties of imported Mexican heirloom corn that yield a rainbow of white, yellow, pink, purple, and dark blue tortillas. He says it’s essential to use heirloom corn when making tortillas “the right way.” Mexican corn breaks down more easily in the nixtamalization process since it has a thinner hull, unlike the sturdy yellow corn that can withstand harsh North American winters.

In my tortilla-making class in Belize, our group managed to produce a few dozen tortillas, which we promptly ate warm, topped with sliced hard-boiled eggs and freshly made salsa. We asked our teacher how many tortillas she made each day for her family. “About 75, three times a day,” she said. It takes her six hours. For people used to ripping open bags of mass-produced tortillas, that was a lot to process. But to our hostess, it was simply the only and best way. And we agreed.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Art as liberation in Iran

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Odd as it may seem, Iran is experiencing an art boom during weeks of mass protests against a hijab-enforcing regime. Recording artists who support the street struggle are enjoying high popularity, mainly for lyrics that inspire hope and unity. Just as strange is this: The most popular song, “For” (in Persian, “Baraye”), mainly recites the most common phrases used by the protesters in media posts, such as “For dancing in the streets, for kissing loved ones” and “For women, life, freedom.”

The song’s appeal may be that it holds a mirror to society. Art is best when it reflects with beauty and essence the deep feelings and hidden thoughts of a people seeking a better life, evoking contemplation.

“Artworks offer a change of rules in the game of discourse; they make it possible to think about shared social issues without invoking the humiliating opposition between those in the right, and those in the wrong,” writes Vid Simoniti, a philosopher at the University of Liverpool.

The value of the arts, if they inspire an open-ended space of thought, can thus become intertwined with the value of democracy, Mr. Simoniti states.

Art as liberation in Iran

Odd as it may seem, Iran is experiencing an art boom during weeks of mass protests against a hijab-enforcing regime. Recording artists who support the street struggle are enjoying high popularity, mainly for lyrics that inspire hope and unity.

Just as strange is this: The most popular song, “For” (in Persian, “Baraye”), mainly recites the most common phrases used by the protesters in media posts, such as “For dancing in the streets, for kissing loved ones” and “For women, life, freedom.”

The song’s writer and singer, Shervin Hajipour, was briefly arrested last month. He is a well-known musician. The song has also been widely nominated for a Grammy in the category of best song for social change. Coldplay is playing “Baraye” during its current world tour.

“The single best way to understand Iran’s uprising is not any book or essay, but Shervin Hajipour’s ... ‘Baraye,’” wrote Karim Sadjadpour, a fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “Its profundity requires multiple views.”

The song’s appeal may be that it holds a mirror to society. Art is best when it reflects with beauty and essence the deep feelings and hidden thoughts of a people seeking a better life, evoking contemplation.

“Artworks offer a change of rules in the game of discourse; they make it possible to think about shared social issues without invoking the humiliating opposition between those in the right, and those in the wrong,” writes Vid Simoniti, a philosopher at the University of Liverpool, in Aeon digital magazine.

The value of the arts, if they inspire an open-ended space of thought, can thus become intertwined with the value of democracy, Mr. Simoniti states. “The other response to the [world’s] democratic crisis has, by contrast, called for a departure from calm deliberation: for anger as a political force, for indignation, for speaking truth to power.”

In Ukraine as well, art has become a tool, one aimed at saving its democracy, especially as Russian bombs have targeted national monuments and cultural structures. In the embattled city of Kharkiv, for example, Ukrainians enjoyed a literary festival in September, organized by Serhiy Zhadan, an author and the frontman for a rock band, Zhadan and the Dogs. “Precisely because Kharkiv is constantly in the line of fire, it is very important for the city to experience a full life, so that it does not live in fear,” Mr. Zhadan told the Kyiv Post.

As Mr. Simoniti notes, art can be a unique form of discourse if it allows audiences to contemplate issues at the heart of political clashes.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Facing nuclear fears with prayer

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Roger Whiteway

Drawing on his experience in the U.S. Navy during the Cold War, a former nuclear weapons training officer reflects on the value of prayer in helping meet challenges and shares inspiration that has fueled his prayers in the face of nuclear concerns today.

Facing nuclear fears with prayer

As concerns about the possible use of tactical nuclear weapons rise, world powers are working to avert this possibility. Must we stand by and watch in fear? Or is there something we can each do to support safety and progress?

“No weapon that is formed against thee shall prosper,” says the biblical prophet Isaiah (Isaiah 54:17), who lived during the seventh and eighth centuries BC. Clearly, the threat of powerful weapons to coerce or dominate is not new. But this promise from God points to a powerful basis for hope. As Christ Jesus came to prove several centuries later, safety comes from leaning on the power, intelligence, and love that reside in the Divine, who is entirely good.

That was how I approached a hazardous duty I had as a junior officer and a pilot in a United States Navy attack carrier squadron deployed during the Cold War. In addition to my pilot duties, I served as the nuclear weapons training officer in our squadron, working up close with tactical nuclear weapons. We were expected to be trained and ready to deliver nukes if directed by national command authority. To be clear, this was not a mission any of us wanted to have to conduct.

Fulfilling this role safely required constant watchfulness, along with peak readiness. Having been raised in Christian Science, I leaned on spiritual solutions and prayed regularly. This provided an atmosphere of calm and confidence in good that was equal to any challenge that arose.

During those times of prayer in my stateroom, I was particularly helped by studying the Bible-based synonyms for God given in the textbook of Christian Science, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy – especially the idea of God as a consistent and good Principle.

One attribute of Principle is alignment, and the effect of this Principle is to bring our thoughts into alignment with the infinite intelligence of the divine Mind, God. We can count on this alignment of the human with the divine to further harmony, not conflict.

Also, there is no place in this infinite Principle for one ego to negatively influence another. Rather, we are influenced by God’s angel messages, or inspiration, coming not just to some of us but to everyone, everywhere. The divine Mind is the source of every legitimate thought and idea, and what Mind creates is good. As the Apostle Paul reassures us, “In him we live, and move, and have our being” (Acts 17:28).

We don’t have to be at the diplomatic table or in a war room in order to ponder how these spiritual facts apply to the fears and anger that could lead to conflict. They provide solid footing for our prayers, making us more receptive to God’s infinite possibilities for good. Then we can say, “Peace, be still” (Mark 4:39), as Christ Jesus did with an authority that stilled a threatening storm, to the notion that fear, hopelessness, or conflict – nuclear or otherwise – is inevitable.

A message of love

Solemnity in South Korea

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Come back tomorrow when we’ll be looking at the likelihood of Britain’s new prime minister, Rishi Sunak, and his Conservative Party winning over the public’s trust.